Abstract

Background:

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection among pregnant women is a major risk factor for a significant proportion of early-onset disease and late-onset disease in infants worldwide; however, data on the epidemiological features of GBS in Vietnam are very limited.

Objectives:

To determine the prevalence, potential risk factors, and serotype distribution of GBS isolates isolated from rectovaginal specimens of Vietnamese pregnant women.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted at three hospitals in Hanoi City, Vietnam, from October 2021 to May 2022. Combined rectovaginal swabs were collected from pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation. GBS was isolated from swabs using selective enrichment in Todd-Hewitt broth and cultured on Columbia agar plates with 5% sheep blood, and Chromogenic Strepto B. All isolates were confirmed through the Gram staining, the CAMP test, and specific Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). GBS serotyping was performed by using the multiplex PCR assays. Risk factors for GBS carriage were analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression tools.

Results:

The prevalence of rectovaginal GBS carriage was 19.52% of 876 participants. Multivariate analysis identified two independent risk factors associated with GBS colonization: a high level of education and yellow vaginal discharge. Among these isolates, serotype III (n = 40, 23.39%) was the most frequently found, followed by serotypes V (n = 37, 21.64%), VI (n = 21, 12.28%), Ia (n = 18, 10.53%), Ib (n = 17, 9.95%), II (n = 8, 8.77%), and VII (n = 1, 0.58%), respectively. Capsular types IV, VIII, and IX were not detected. No statistically significant correlation was found between GBS infection and the distribution of the identified serotypes.

Conclusion:

The GBS colonization rate in pregnant women was consistent with findings from other studies worldwide. Higher educational attainment and the presence of yellow vaginal discharge were independently associated with an increased risk of GBS colonization. The predominance of GBS serotypes III, V, and VI was a notable feature among the strains isolated from pregnant women in Vietnam.

Keywords: pregnant women, risk factors, serotypes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Vietnam

Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae, also known as group B Streptococcus (GBS), is part of the normal flora of the genital tract and rectum of healthy women. It is an opportunistic Gram-positive bacterium and one of the important causes of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide.1–3 This etiological agent is also known as a leading pathogen of neonatal pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis.2,3 In pregnant women, GBS has been found in 11.0%–35.0% of cases. It is usually asymptomatic but may lead to urinary tract infections, stillbirths, sepsis, and meningitis. 4 Thus, efforts to prevent and control this etiological agent are growing in importance.5–7

Currently, GBS is classified into ten capsular polysaccharide (CPS) types and designated Ia, Ib, II–IX.7–9 Of them, serotypes Ia, III, and V are determined to account for the majority in causing invasive infections of GBS.7,10 According to epidemiological studies, GBS serotype Ia was the predominant serotype in Canada, South America, and North America, serotype III was the most common in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, and Asia, and serotype VIII predominated in Japan.11,12 Global data have indicated that the serotype distribution of GBS varies depending on different geographical locations, sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, the source of the bacterial isolates, and the period of data collection.7,13,14 According to previous studies, serotype III strains are the cause of a large proportion of early-onset disease (EOD) and the majority of late-onset disease (LOD) in newborns worldwide. 15 Therefore, information on serotype prevalence is essential for designing effective control strategies and developing suitable vaccines.

In Vietnam, GBS infection among pregnant women is not part of routine screening procedures, and infected cases are not reported to the Health Department. In addition, no public health regulations or national guidelines for GBS screening are included in the prenatal care of pregnant women. 16 Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that the rate of GBS colonization in Vietnamese pregnant women ranges from 8.02% to 25.5%.7,16,17 Although several investigations have explored the prevalence and serotypes of GBS in Vietnam,7,18 data on GBS serotypes remain very limited, and the risk factors associated with GBS colonization in pregnant women have not been fully appreciated. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the prevalence, potential risk factors, and serotype distribution of GBS isolates obtained from rectovaginal specimens of Vietnamese pregnant women.

Materials and methods

Study design, duration, and participants

The current cross-sectional study was conducted at three hospitals, including Military Hospital 103 (1200 beds, Ha Dong district), Ha Dong General Hospital (900 beds, Ha Dong district), and Hanoi Maternity Hospital (650 beds, Hanoi City, Vietnam), located in Hanoi City, Vietnam, between October 2021 and May 2022. Participants were selected from among healthy pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation attending the antenatal outpatient/inpatient department. The inclusion criteria were: (1) pregnancy at 35–37 weeks of gestation, determined by self-report or confirmed by a gynecologist, (2) willingness to provide written informed consent to participate in the current study, and (3) agreement to respond to the questions in the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria included refusal to provide consent, use of any systemic or topical antibiotic therapy within the last 7 days, HIV infection, and a history of vaginal bleeding or leakage. All pregnant women participating in this study were informed about the benefits, the purpose of the research, and the procedures involved in data collection. The reporting of the current study adheres to the STROBE statement. 19 The STROBE checklist of items is included in Supplemental File I.

Sample size and sampling technique

In this study, the formula n = was used to calculate the required sample size, 20 with an envisaged confidence interval of 95%, an estimated infection prevalence of 19.00% (average GBS colonization in South Asia), 21 and a precision of 3%. The minimum required sample size was calculated to be 657 pregnant women. In fact, a total of 876 pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation were enrolled. Eligible participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique until the required sample size was attained.

Data/sample collection

Rectovaginal specimens were collected from women during pregnancy at 35–37 weeks of gestation by a trained nurse or gynecologist using sterile cotton swabs, in accordance with the American Society for Microbiology’s 2020 recommendations, after written informed consent had been obtained. 22 All samples were subsequently transported, without transport medium, in a plastic container at ambient temperature, to the clinical microbiology laboratory of either Military Hospital 103 or Hanoi Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital within 2 h for GBS isolation. Each swab was then inoculated into Todd-Hewitt selective enrichment medium broth supplemented with nalidixic acid (15 mg/L) and colistin sulfate (10 mg/L) (Melab Diagnostics, Vinh Phuc, Vietnam) and incubated aerobically at 35°C–37°C for 18–24 h. After incubation, 10 μL of each broth was subcultured on Columbia agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) and Chromogenic Strepto B (Melab Diagnostics, Vinh Phuc, Vietnam). The plates were then incubated for 18–24 h at 35°C –37°C in 5% CO2. 23 Candidate GBS isolates typically appeared as translucent gray-to-white colonies measuring over 0.5 mm in diameter, with or without a narrow zone of beta-hemolysis on blood agar, and as mauve colonies on CHROMagar StrepB. Plates showing no growth after 24 h were re-incubated for an additional 24 h before being declared culture-negative. All suspected GBS colonies—beta-haemolytic or non-hemolytic—that were Gram-positive and catalase-negative cocci underwent a CAMP test.22,23 After this initial phenotypic identification, GBS isolates were further confirmed by PCR using specific primer pairs. For quality control, S. agalactiae (ATCC 13813), S. pyogenes (ATCC 19615), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) (Thermo Scientific™, Marsiling Industrial Estate, Singapore) were chosen as reference strains.

Molecular identification and serotyping of GBS strains

The genomic DNA of suspected isolates was extracted using the G-spin™ Total DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRon, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). Subsequently, all extracted DNA of suspected strains were used in the polymerase chain reactions with a specific primer pair for the dltS gene and the conditions as previously described by Poyart et al. 8 A suspected strain was confirmed to be GBS when its PCR product showed a 952 bp band.

Capsular typing identification of GBS isolates was determined by conventional multiplex PCR (mPCR) amplification using specific primers, as reported by Poyart et al. 8 Three different groups of mPCR assays were carried out for capsular serotyping as described by Hanh et al. 7 : group 1 for genotypes Ia, Ib, II, and III; group 2 for genotypes IV and V; and group 3 for genotypes VI, VII, and VIII. For the determination of the serotype IX, an additional PCR was performed as previously described by Imperi et al. 24 The amplicons were separated on 1.5% agarose gels for approximately 1 h at 100 V and subsequently visualized under UV light using a UVP system (Canada). A 100 bp size marker (Cleaver Scientific, Warwickshire, England) was used to determine the PCR product sizes.

Statistical analyses

In this study, SPSS software for Windows, version 22.0 (Released 2013; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was employed for statistical analysis of the data. To identify potential risk factors related to GBS infections, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to determine the association between GBS infections and risk/indicator factors using either a Fisher’s exact test or a Pearson chi-square test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

In the current study, three different hospitals in Hanoi were surveyed, and 876 healthy pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation were enrolled. The mean age of participants was 29.26 years (range: 17–43, standard deviation (SD) = 4.78). 97.26% of participants belonged to the Kinh ethnic group, with the majority being in urban areas (54.68%), and 45.21% were freelancers. In addition, more than three-quarters (82.9%) had an education level above vocational training or a bachelor’s degree (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, prevalence, and related factors of GBS infection among pregnant women.

| Characteristics | No. tested | GBS (+) | % | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Age groups (years old) | |||||||

| ⩽25 | 204 | 45 | 22.06 | — | 1 | ||

| 26–35 | 575 | 102 | 17.74 | 0.18 | 1.31 (0.89–1.95) | ||

| >35 | 97 | 24 | 24.74 | 0.61 | 0.86 (0.49–1.52) | ||

| Ethnic group | |||||||

| Kinh | 852 | 165 | 19.37 | 0.44 | 0.72 (0.28–1.84) | ||

| Other | 24 | 6 | 25.0 | ||||

| Residence | |||||||

| Urban | 479 | 87 | 18.16 | 0.27 | 0.83 (0.59–1.16) | ||

| Rural | 397 | 84 | 21.16 | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| Pre-High school | 34 | 2 | 5.88 | — | 1 | — | 1 |

| High school | 116 | 27 | 23.28 | 0.04 | 0.21 (0.05–0.92) | 0.045 | 0.22 (0.05–0.97) |

| Vocational and bachelor | 726 | 142 | 19.56 | 0.07 | 0.26 (0.06–1.09) | 0.092 | 0.29 (0.07–1.22) |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Farmer | 75 | 13 | 17.33 | 1 | |||

| Worker | 12 | 2 | 16.67 | 0.96 | 1.05 (0.21–5.36) | ||

| Government service | 260 | 59 | 22.69 | 0.32 | 0.71 (0.37–1.39) | ||

| Trade | 133 | 22 | 16.54 | 0.88 | 1.06 (0.50–2.25) | ||

| Self-employed | 396 | 75 | 18.94 | 0.74 | 0.90 (0.47–1.72) | ||

| History of vaginitis | |||||||

| Yes | 217 | 50 | 23.04 | 0.13 | 1.33 (0.92–1.93) | ||

| No | 659 | 121 | 18.36 | ||||

| History of miscarriage | |||||||

| Yes | 194 | 30 | 15.46 | 0.11 | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | ||

| No | 682 | 141 | 20.67 | ||||

| History of preterm birth | |||||||

| Yes | 34 | 6 | 17.65 | 0.78 | 0.88 (0.36–2.16) | ||

| No | 842 | 165 | 19.60 | ||||

| History of gynecological surgery | |||||||

| Yes | 154 | 32 | 20.78 | 0.66 | 1.1 (0.71–1.69) | ||

| No | 722 | 139 | 19.25 | ||||

| Vaginal douching | |||||||

| Yes | 127 | 27 | 21.26 | 0.63 | 1.13 (0.71–1.80) | ||

| No | 749 | 144 | 19.23 | ||||

| Parity (No. previous births) | |||||||

| ⩽2 | 838 | 165 | 19.69 | 0.55 | 1.31 (0.54–3.18) | ||

| ⩾3 | 38 | 6 | 15.79 | ||||

| Vaginal discharge | |||||||

| Yes | 422 | 91 | 21.56 | 0.14 | 1.29 (0.92–1.80) | ||

| No | 454 | 80 | 17.62 | ||||

| Vulvovaginal pruritus | |||||||

| Yes | 80 | 23 | 28.75 | 0.03 | 1.77 (1.06–2.96) | 0.096 | 1.57 (0.92–2.66) |

| No | 796 | 148 | 18.59 | ||||

| Color of vaginal discharge | |||||||

| Clear | 176 | 27 | 15.34 | — | 1 | — | 1 |

| White | 549 | 105 | 19.13 | 0.26 | 0.77 (0.48–1.22) | 0.36 | 0.81 (0.51–1.28) |

| Brown | 35 | 6 | 17.14 | 0.79 | 0.88 (0.33–2.31) | 0.79 | 0.88 (0.33–2.32) |

| Yellow | 116 | 33 | 28.45 | 0.007 | 0.46 (0.26–0.81) | 0.021 | 0.5 (0.28–0.90) |

| Vaginitis | |||||||

| Yes | 83 | 19 | 22.89 | 0.42 | 1.25 (0.73–2.15) | ||

| No | 793 | 152 | 19.17 | ||||

| Diabetes | |||||||

| Yes | 57 | 10 | 17.54 | 0.70 | 0.87 (0.43–1.76) | ||

| No | 819 | 161 | 19.66 | ||||

| Anemia | |||||||

| Yes | 108 | 22 | 20.37 | 0.81 | 1.06 (0.64–1.75) | ||

| No | 768 | 140 | 19.40 | ||||

| BMI | |||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 452 | 85 | 18.81 | 0.63 | 0.92 (0.66–1.29) | ||

| ⩾25 kg/m2 | 418 | 84 | 20.10 | ||||

95% CI, 95% confidence intervals; GBS, group B Streptococcus; OR, odds ratio; Pos, positive.

The bolded values indicate a statistically significant difference from the comparison group.

Prevalence of GBS infection

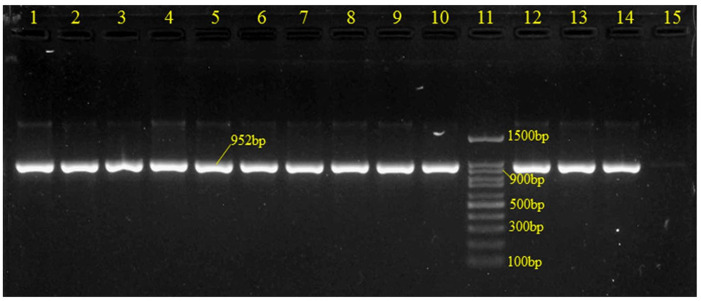

Out of the 876 participants, 178 (20.30%) were found to be suitable for GBS by culture and Gram staining. All of the isolates that were GBS culture-positive were also confirmed by species-specific PCR primers (Figure 1). Among them, 171/876 (19.52% (95% CI 16.94–22.30)) isolates were found to be positive for GBS.

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoresis of GBS-specific PCR products targeting the 952bp dltS gene.

Lanes 1–10 and 12–13: clinical GBS samples; Land 11: molecular size standard (100 bp DNA ladder); Lane 14: positive control (Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC® 13813); Land 15: negative control.

GBS, Group B Streptococcus.

Factors associated with GBS infection

The association of sociodemographic variables, disease history, and clinical features with GBS colonization is summarized in Table 1. A statistically significant correlation was observed between the level of education and yellow vaginal discharge with GBS carriage. For other factors, both the univariate and multivariate analyses showed no statistically significant association between GBS colonization and sociodemographic characteristics. In addition, GBS colonization also showed no statistically significant association with a history of vaginitis, miscarriage, preterm birth, or gynecologic surgery. Pregnant women with a history of vaginal douching, fewer than two previous births, abnormal vaginal discharge, vaginitis symptoms, or anemia symptoms tended to exhibit higher GBS colonization rates than those without these signs. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

GBS serotype distribution

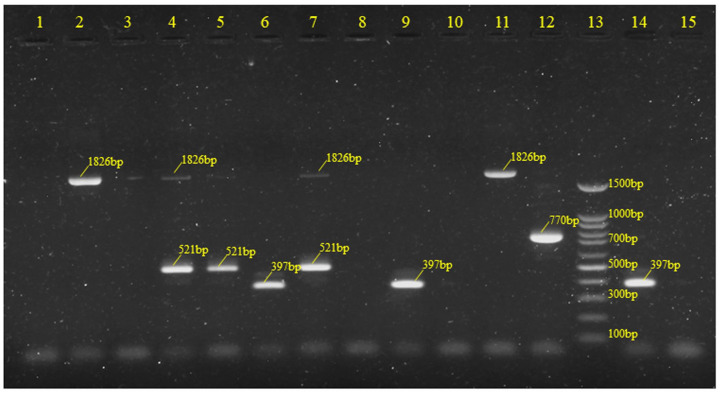

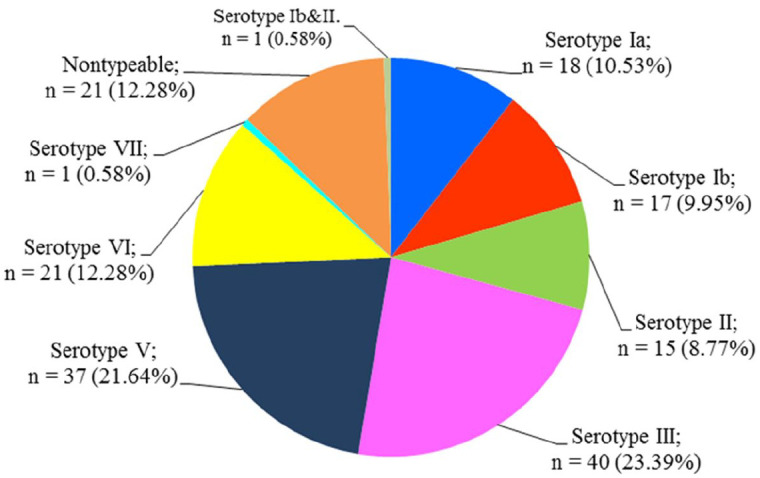

Based on mPCR, a total of seven serotypes were identified. The most common serotypes were III (n = 40, 23.39%) and V (n = 37, 21.64%), followed by VI (n = 21, 12.28%), Ia (n = 18, 10.53%), Ib (n = 17, 9.95%), II (n = 8, 8.77%), and VII (n = 1, 0.58%); one woman had both serotype Ib and II. The distribution frequency of the serotypes is shown in Figures 2 and 3. There were twenty-one strains that were non-typeable using the mPCR method (n = 21, 12.28%). Capsular types IV, VIII, and IX were not found (Supplemental File II).

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of capsular types among pregnant women.

Figure 3.

The mPCR patterns of serotypes Ia, Ib, II, and III.

Lanes 4, 5, and 7 denoted to those of serotype Ia; Lane 12 denoted to those of serotype Ib; Lanes 6 and 9 denoted to those of serotype II; Lanes 2 and 11 denoted to those of serotype III; Lanes 1, 3, and 8 denoted to those of serotypes not belonging to groups I, II, or III. Lane 13: 100 bp DNA ladder (molecular weight marker); Lane 14: positive control (serotype II); Lane 15: negative control.

mPCR, multiplex PCR.

The obtained results indicated that there was no significant association between different GBS serotypes and age groups, abnormal vaginal discharge, vaginitis symptoms, presence of anemia symptoms, history of miscarriage, history of gynecologic surgery, or history of vaginal douching. However, a statistically significant association was found between serotype NT and diabetes status (OR 5.65; 95% CI 1.45–22.03; p = 0.02) among pregnant women at 35–37 weeks of gestation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of GBS serotypes with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the study population.

| Serotype | Total (n (%)) | Age groups (⩽25 years) | Abnormal vaginal discharge | Having vaginitis symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Ia | 18 (10.53) | 4 (22.22) | 0.78 | 0.78 (0.24–2.51) | 8 (44.44) | 0.43 | 0.68 (0.25–1.80) | 3 (16.67) | 0.43 | 1.71 (0.45–6.56) |

| Ib | 17 (9.95) | 4 (23.53) | 1 | 0.85 (0.26–2.75) | 12 (70.59) | 0.13 | 2.28 (0.77–6.78) | 3 (17.65) | 0.41 | 1.85 (0.48–7.13) |

| II | 15 (8.77) | 3 (20.0) | 0.76 | 0.68 (0.18–2.52) | 8 (53.33) | 0.99 | 1.01 (0.35–2.91) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| III | 40 (23.39) | 9 (22.5) | 0.53 | 0.77 (0.33–1.77) | 21 (52.50) | 0.92 | 0.96 (0.47–1.96) | 2 (5.00) | 0.25 | 0.35 (0.08–1.60) |

| V | 37 (21.64) | 14 (37.84) | 0.07 | 2.02 (0.93–4.40) | 23 (62.16) | 0.22 | 1.60 (0.76–3.36) | 6 (16.22) | 0.25 | 1.80 (0.63–5.12) |

| VI | 21 (12.28) | 4 (19.05) | 0.42 | 0.63 (0.20–1.97) | 8 (38.10) | 0.14 | 0.50 (0.19–1.27) | 2 (9.52) | 1 | 0.82 (0.18–3.85) |

| VII | 1 (0.58) | 1 (100) | — | — | 1 (100) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Ib and II | 1 (0.58) | 1 (100) | — | — | 1 (100) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| NT | 21 (12.28) | 5 (23.81) | 0.78 | 0.86 (0.30–2.50) | 9 (42.86) | 0.31 | 0.62 (0.25–1.56) | 3 (14.29) | 0.71 | 1.40 (0.37–5.27) |

| Associations of GBS serotypes with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the study population.Associations of GBS serotypes with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the study population | ||||||||||

| Serotype | Total (n (%)) | Having diabetes mellitus | Having anemia symptoms | Having vulvovaginal pruritus | ||||||

| n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Ia | 18 (10.53) | 2 (11.11) | 0.28 | 2.27 (0.44–11.60) | 1 (5.56) | 0.47 | 0.37 (0.05–2.93) | 5 (27.78) | 0.07 | 2.89 (0.92–9.04) |

| Ib | 17 (9.95) | 2 (11.76) | 0.26 | 2.43 (0.47–12.52) | 3 (17.65) | 0.46 | 1.52 (0.40–5.79) | 1 (5.88) | 0.48 | 0.38 (0.05–2.97) |

| II | 15 (8.77) | 0 (0) | — | — | 2 (13.33) | 1 | 1.05 (0.22–4.98) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| III | 40 (23.39) | 2 (5.00) | 1 | 0.81 (0.17–3.98) | 7 (17.50) | 0.32 | 1.64 (0.62–4.36) | 9 (20.0) | 0.17 | 1.93 (0.75–4.97) |

| V | 37 (21.64) | 0 (0) | — | — | 4 (10.81) | 0.79 | 0.78 (0.25–2.47) | 3 (8.11) | 0.28 | 0.50 (0.14–1.79) |

| VI | 21 (12.28) | 0 (0) | — | — | 2 (9.52) | 1 | 0.68 (0.15–3.16) | 2 (9.52) | 0.74 | 0.65 (0.14–2.98) |

| VII | 1 (0.58) | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Ib and II | 1 (0.58) | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| NT | 21 (12.28) | 4 (19.05) | 0.02 | 5.65 (1.45–22.03) | 3 (14.29) | 0.74 | 1.15 (0.31–4.27) | 4 (19.05) | 0.49 | 1.62 (0.49–5.34) |

| Associations of GBS serotypes with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the study population. | ||||||||||

| Serotype | Total (n (%)) | History of miscarriage | History of gynecologic surgery | History of vaginal douching | ||||||

| n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Ia | 18 (10.53) | 3 (16.67) | 1 | 0.93 (0.25–3.45) | 5 (27.78) | 0.34 | 1.80 (0.59–5.46) | 3 (16.67) | 1 | 1.08 (0.29–4.00) |

| Ib | 17 (9.95) | 1 (5.88) | 0.31 | 0.27 (0.03–2.11) | 5 (29.41) | 0.32 | 1.96 (0.64–6.02) | 1 (5.88) | 0.48 | 0.31 (0.04–2.42) |

| II | 15 (8.77) | 3 (20.00) | 0.73 | 1.19 (0.32–4.52) | 2 (13.33) | 0.74 | 0.65 (0.14–3.02) | 2 (13.33) | 1 | 0.81 (0.17–3.79) |

| III | 40 (23.39) | 6 (15.00) | 0.63 | 0.79 (0.30–2.08) | 7 (17.50) | 0.82 | 0.90 (0.36–2.27) | 9 (22.50) | 0.18 | 1.82 (0.75–4.45) |

| V | 37 (21.64) | 9 (24.32) | 0.22 | 1.73 (0.72–4.19) | 7 (18.92) | 0.97 | 1.02 (0.40–2.58) | 4 (10.81) | 0.35 | 0.59 (0.19–1.81) |

| VI | 21 (12.28) | 5 (23.81) | 0.38 | 1.56 (0.52–4.66) | 2 (9.52) | 0.37 | 0.42 (0.09–1.91) | 2 (9.52) | 0.54 | 0.53 (0.12–2.40) |

| VII | 1 (0.58) | 0 (0) | — | — | 1 (100) | — | — | 1 (100) | — | — |

| Ib and II | 1 (0.58) | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| NT | 21 (12.28) | 3 (14.29) | 1 | 0.76 (0.21–2.76) | 3 (14.28) | 0.77 | 0.70 (0.19–2.52) | 5 (23.81) | 0.34 | 1.82 (0.60–5.47) |

Discussion

GBS is recognized as a leading cause of neonatal meningitis, sepsis, and pneumonia worldwide.2,3,25,26 Investigations conducted in various countries have revealed that the prevalence of GBS differs across countries, geographic regions, and depends on the studied populations, sampling techniques, and diagnostic methods.2,7,27–29 According to a recent report from the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 150,000 neonatal deaths, more than half a million preterm births, and a significant number of long-term disability cases due to GBS occur annually worldwide.30–32 However, limited data on this issue have been reported in Vietnam, especially regarding the serotype distribution of GBS. In accordance with previous studies conducted globally, the distribution of GBS serotypes varies across different geographical regions, periods of investigation, and ethnic origin of pregnant women.7,10,26,33 Screening for GBS colonization and identification of GBS serotypes are important steps toward reducing cases of neonatal sepsis and adjusting the diagnosis and prevention guidelines for GBS infection.29,34

The available data from various studies indicated that the GBS colonization rate among pregnant women varies by region, with prevalence rates ranging from 11.0% to 35.0%. 4 In this study, the GBS colonization rate among Vietnamese pregnant women was 19.52%. Our finding is higher than some previous reports in Vietnam7,17 and other countries such as Thailand (11.3%), 35 Iran (6.7%), 29 India (3.3% and 2.3%),36,37 China (4.9% and 7.1%),14,34 Madagascar and Senegal (5.0% and 16.1%), 38 Cameroon (4.0%), 39 and Korea (10.0%). 40 Studies from Eastern Asia, Turkey, and Namibia also reported a lower rate of GBS among women during pregnancy than in the current research (11.0%, 9.2%, 13.6% vs 19.52%).4,12,13 Our findings were consistent with those of previous studies conducted in Europe (19.0%), America (19.7%), 41 Kenya (20.5%), 26 Jordan (19.5%), 42 Pakistan (20%), 4 and Eastern Africa (20.0%).4,38 Higher prevalence rates were reported in Ethiopia (25.5%), 43 Saudi Arabia (27.6%), 44 and South Africa (37.0%). 13 The GBS colonization rate among Vietnamese pregnant women in our investigations was within the documented range. The reasons for these variations are related to differences in sampling techniques, specimen collection sites, geographic regions of the study population, sample size, study duration, maternal immune responses to GBS colonization, and the method used for GBS isolation and identification.4,7,10,16,38,45

According to previous studies, intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) was determined to be the main means of preventing GBS disease in newborn infants. 46 The WHO and the US-CDC recommended that pregnant women with GBS colonization or any risk factors for EOD should receive IAP. 47 Consequently, screening and analyzing risk factors for GBS colonization during pregnancy are essential in reducing the incidence of related neonatal morbidity and mortality. 29 However, in low- and middle-income countries, antepartum screening for GBS and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is the biggest challenge to implement. 30 In Vietnam, screening for GBS colonization in pregnant women has received limited attention, especially in non-specialized hospitals.

This study found two factors, including education level and the color of vaginal discharge (yellow), were associated with GBS carriage. However, the results from various studies have shown an inconsistent relationship between GBS infection and demographic and obstetric factors, disease history, as well as clinical features.1,29,48 For example, in the current study, there was no association between GBS infection in pregnant women and factors such as sociodemography (age, ethnicity, geographic location, and occupation), obstetrics (history of vaginitis, miscarriage, preterm delivery, gynecologic surgery, parity, abnormal vaginal discharge, diabetes, anemia, and obesity). Similar results were also found in previous surveys in Iran, 29 Lebanon, 1 Ethiopia, 43 Morocco, 49 Kenya, 26 Madagascar, and Senegal. 38 Conversely, some previous studies revealed that risk factors for maternal GBS colonization included maternal age, body mass index before pregnancy, gestational age, induced abortion, lotion use before pregnancy, pre-labor rupture of membranes, and diabetes mellitus.34,46,50 Similarly, conflicting results regarding the relationship between smoking, nulliparity, vaginal douching, vaginal pruritus, gestational hypertension, as well as urinary tract infections and GBS infection were also observed in many reported studies.27,28,36,49,51–55

In this study, seven serotypes were identified, including Ia, Ib, II, III, V, VI, and VII. Among these, serotype III was the most prevalent (23.39%), followed by V and VI (21.64% and 12.28%), while serotypes Ia, Ib, II, and VII were observed with lower percentages, ranging from 0.58% to 10.53%. The distribution of GBS serotypes III, V, and VI was similarly found in Nghe An province, Vietnam. 7 These findings in the current study were slightly different from previous reports worldwide. Accordingly, serotypes V, II, and III are the most prevalent among pregnant women in Morocco, 49 while serotypes Ia, V, and II predominated in Brazil. 56 In Bangkok, Thailand, serotype V was the most prevalent, accounting for 45.8%, 51 whereas serotype III predominated in China,14,57 Japan, 58 Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, and Asia. 12 Serotype II was predominant in Namibia and South Africa, 13 Indonesia, 52 and along the Thai-Myanmar border. 11 Serotype VII was prevalent in Ghana, 59 serotype Ia was common in Saudi Arabia, 60 in Australia, 61 and in the United States, 12 and a high prevalence of serotype IX was observed in Denmark. 62 Notably, serotype VI was observed with a relatively high prevalence (12.28%) in the current study. This serotype was similarly reported in the previous investigations conducted in Nghe An province, Vietnam, 7 and in several Asian countries, including Malaysia,63,64 Taiwan,33,65 and Japan. 66 The reasons for these variations in the distribution of GBS serotypes might be due to features of the population being investigated, various geographical regions, source of the bacterial strains, and the time periods of the studies.13,67–69 Moreover, the distribution of GBS serotypes not only varies between countries but also among regions within the same country, with the prevalence of serotypes changing over time. 10 Therefore, additional surveys should be conducted to further clarify the prevalence and distribution of GBS serotypes in various regions of Vietnam.

A notable finding in this study is that 21 out of 171 strains (12.28%) were non-typeable. Similar observations have been reported in several regions, with relatively high rates of non-typeable strains, including Beijing, China (14.3%), 68 Argentina (5.5%), 70 and Denmark (9.4%–9.8%, in cases of invasive GBS infection).62,71 The potential reasons for the presence of non-typeable strains may include nucleotide mutations at primer binding sites, non-specific primers, or the emergence of novel serotypes within the GBS population in Vietnam. Thus, further investigations should be carried out to identify the serotypes of the non-typeable GBS strains.

The findings from this investigation indicated that clinical features such as age groups, abnormal vaginal discharge, vaginitis, diabetes mellitus, anemia, vulvovaginal pruritus, miscarriage, history of gynecologic surgery, and history of vaginal douching were not associated with any identified GBS serotypes. These findings are consistent with some previous studies in São Paulo, Brazil 56 and Yazd, Iran. 72 Generally, data on this relationship are very limited. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study on the association between GBS serotypes and clinical features, as well as disease history, among pregnant women in Vietnam. A better understanding of this issue is necessary to implement more specific treatment strategies. 56 Therefore, further research is required to investigate the association between serotypes and GBS colonization among pregnant women.

Our study revealed some limitations, including the absence of antimicrobial susceptibility data, the lack of information on coinfection of GBS with fungi and other bacteria, and the inability to fully identify twenty-one non-typeable strains. Due to these limitations, some issues have not been thoroughly addressed. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify these matters.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study indicated that the GBS colonization rate among Vietnamese pregnant women was 19.52%, which was within the reported range. A high level of education and yellow vaginal discharge were statistically significant factors associated with maternal GBS carriage. Serotypes III, V, and VI were the most common serotypes. No significant differences were found in the relationship between GBS serotypes and clinical features among pregnant women.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tai-10.1177_20499361251365028 for Prevalence, risk factors, and serotypes of group B Streptococcus rectovaginal colonization among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study at three hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam by Van Le Nguyen, Hung Nguyen Dao, Van Thi Hong Le, An Van Nguyen, Van Thi Thu Ha, Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen, Hoa Thanh Do, Nguyen Thai Son and Do Ngoc Anh in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease

Supplemental material, sj-pptx-2-tai-10.1177_20499361251365028 for Prevalence, risk factors, and serotypes of group B Streptococcus rectovaginal colonization among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study at three hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam by Van Le Nguyen, Hung Nguyen Dao, Van Thi Hong Le, An Van Nguyen, Van Thi Thu Ha, Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen, Hoa Thanh Do, Nguyen Thai Son and Do Ngoc Anh in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease

Acknowledgments

The current study was partially supported by the Department of Science and Technology of Hanoi City, Vietnam. We are also grateful to the Department of Medical Parasitology (Military Medical University, Vietnam) for supplying the instruments used to confirm the GBS species and identify GBS serotypes of the samples.

Appendix

Abbreviations

ATCC American Type Culture Collection

CI confidence interval

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CPS capsular polysaccharide

EOD early-onset disease

GBS group B Streptococcus

LOD late-onset disease

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Van Le Nguyen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9563-545X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9563-545X

Hung Nguyen Dao  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1692-1628

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1692-1628

Van Thi Hong Le  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2357-4020

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2357-4020

An Van Nguyen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4973-203X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4973-203X

Van Thi Thu Ha  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7550-7709

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7550-7709

Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-7038-2582

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-7038-2582

Nguyen Thai Son  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5878-9150

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5878-9150

Do Ngoc Anh  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-7659

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-7659

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Van Le Nguyen, Department of Medical Microbiology, Military Hospital 103, Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Hung Nguyen Dao, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vietnam Military Hospital 103, Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Van Thi Hong Le, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vietnam Military Hospital 103, Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

An Van Nguyen, Department of Medical Microbiology, Military Hospital 103, Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Van Thi Thu Ha, Department of Medical Microbiology, Military Hospital 103, Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen, Department of Medical Parasitology, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Hoa Thanh Do, Emergency Department, Military Central Hospital 108, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Nguyen Thai Son, Department of Medical Microbiology, Medlatec Healthcare System, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Do Ngoc Anh, Department of Medical Parasitology, Vietnam Military Medical University, No. 160 Phunghung Road, Hadong District, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Vietnam Military Medical University (Ha Noi, Vietnam) in September 2021 (ethics code: 4411/QÐ-HVQY) and Military Hospital 103 (Ha Noi, Vietnam) in January 2023 (ethics code: 08/CNChT-HĐĐĐ) and was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. At the time the study was conducted, the remaining two hospitals had not yet established their own Ethics Review Boards and were therefore unable to issue ethical approval. The review of ethical aspects at these two hospitals was conducted by the Ethics Review Board of the Vietnam Military Medical University, in accordance with the regulations of the Vietnam Ministry of Health. Furthermore, we also obtained confirmation of research collaboration and written consent from the leadership of each participating hospital, as required by their respective administrations (Decision No. 111/QĐ-BYT and Circular No. 4/TT-BYT promulgated by the Vietnam Ministry of Health on January 11, 2013, and March 5, 2020, respectively). All participants were informed of the study’s purpose and benefits, and written informed consent was obtained from each pregnant woman.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Van Le Nguyen: Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Hung Nguyen Dao: Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Van Thi Hong Le: Data curation; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

An Van Nguyen: Data curation; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Van Thi Thu Ha: Data curation; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen: Data curation; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Hoa Thanh Do: Data curation; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Nguyen Thai Son: Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Do Ngoc Anh: Conceptualization; Data curation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam (Grant no. 3389/QĐ-HVQY, to NLV).

Competing interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Dr. Do Ngoc Anh, email: dranhk61.vmmu@gmail.com) on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Alfouzan W, Gaddar N, Dhar R, et al. A study of group B Streptococcus in pregnant women in Lebanon: prevalence, risk factors, vaginal flora and antimicrobial susceptibility. Infez Med 2021; 29: 85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim DH, Min BJ, Jung EJ, et al. Prevalence of group B Streptococcus colonization in pregnant women in a tertiary care center in Korea. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2018; 61: 575–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song JY, Lim JH, Lim S, et al. Progress toward a group B streptococcal vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018; 14: 2669–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russell NJ, Seale AC, O’Driscoll M, et al. Maternal colonization with group B Streptococcus and serotype distribution worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65: S100–S111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morozumi M, Wajima T, Takata M, et al. Molecular characteristics of group B Streptococci isolated from adults with invasive infections in Japan. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54: 2695–2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ballard MS, Schonheyder HC, Knudsen JD, et al. The changing epidemiology of group B Streptococcus bloodstream infection: a multi-national population-based assessment. Infect Dis (Lond) 2016; 48: 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanh TQ, Van Du V, Hien PT, et al. Prevalence and capsular type distribution of group B Streptococcus isolated from vagina of pregnant women in Nghe An province, Vietnam. Iran J Microbiol 2020; 12: 11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poyart C, Tazi A, Réglier-Poupet H, et al. Multiplex PCR assay for rapid and accurate capsular typing of group B Streptococci. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 1985–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slotved HC, Kong F, Lambertsen L, et al. Serotype IX, a proposed new Streptococcus agalactiae serotype. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 2929–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Africa CWJ, Kaambo E. Group B Streptococcus serotypes in pregnant women from the Western Cape Region of South Africa. Front Public Health 2018; 6: 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turner C, Turner P, Po L, et al. Group B streptococcal carriage, serotype distribution and antibiotic susceptibilities in pregnant women at the time of delivery in a refugee population on the Thai-Myanmar border. BMC Infect Dis 2012; 12: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ippolito DL, James WA, Tinnemore D, et al. Group B Streptococcus serotype prevalence in reproductive-age women at a tertiary care military medical center relative to global serotype distribution. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 336–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mukesi M, Iweriebor BC, Obi LC, et al. Prevalence and capsular type distribution of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women in Namibia and South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 1: 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu B, Li D, Cui Y, et al. Epidemiology of group B Streptococcus isolated from pregnant women in Beijing, China. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20: O370–O373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang HM, Lee HJ, Lee H, et al. Genotype characterization of Group B Streptococcus isolated from infants with invasive diseases in South Korea. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017; 36: e242–e247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ha M-T, Tran-Thi-Bich H, Bui-Thi-Kim T, et al. Comparison of qPCR and chromogenic culture methods for rapid detection of group B Streptococcus colonization in Vietnamese pregnant women. Pract Lab Med 2024; 42: e00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Du V, Dung PT, Toan NL, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in colonizing group B Streptococcus among pregnant women from a hospital in Vietnam. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 20845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Van N, Nhu Quynh NT, Thu Van HT, et al. Distribution of group B Streptococcus serotype III among pregnant women in Hanoi. J Commu Med (Vietnam) 2024; 65: 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007; 18: 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med 2013; 35: 121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwatra G, Izu A, Cutland C, et al. Prevalence of group B Streptococcus colonisation in mother–newborn dyads in low-income and middle-income south Asian and African countries: a prospective, observational study. Lancet Microbe 2024; 5: 100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Filkins L, Hauser JR, Robinson-Dunn B, et al. American Society for Microbiology provides 2020 guidelines for detection and identification of group B Streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 59: e01230-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwatra G, Madhi SA, Cutland CL, et al. Evaluation of Trans-Vag Broth, colistin-nalidixic agar, and CHROMagar StrepB for detection of group B Streptococcus in vaginal and rectal swabs from pregnant women in South Africa. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51: 2515–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imperi M, Pataracchia M, Alfarone G, et al. A multiplex PCR assay for the direct identification of the capsular type (Ia to IX) of Streptococcus agalactiae. J Microbiol Methods 2010; 80: 212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trotter CL, Alderson M, Dangor Z, et al. Vaccine value profile for group B Streptococcus. Vaccine 2023; 41: S41–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jisuvei SC, Osoti A, Njeri MA. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, serotypes and risk factors for group B Streptococcus rectovaginal isolates among pregnant women at Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenya; a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sama LF, Noubom M, Kenne C, et al. Group B Streptococcus colonisation, prevalence, associated risk factors and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Dschang District Hospital, West Region of Cameroon: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75: e14683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qadi M, AbuTaha A, Al-Shehab Ry, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of group B Streptococcus colonization in pregnant women: a pilot study in Palestine. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2021; 2021: 8686550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dashtizade M, Zolfaghari MR, Yousefi M, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns and prevalence of Streptococcus agalactiae rectovaginal colonization among pregnant women in Iran. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2020; 42: 454–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO. Urgent need for vaccine to prevent deadly Group B Streptococcus. Geneva/London: WHO, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alas-Pineda Cs, Raudales BM, Bueso AC, et al. Prevalencia de colonización rectovaginal por Streptococcus agalactiae en mujeres gestantes atendidas en un hospital de segundo nivel en Honduras. Rev peru ginecol obstet 2023; 69: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32. do Nascimento CS, dos Santos NFB, Ferreira RCC, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae in pregnant women in Brazil: prevalence, serotypes, and antibiotic resistance. Braz J Microbiol 2019; 50: 943–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee CC, Hsu JF, Prasad Janapatla R, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of group B Streptococcus from pregnant women and diseased infants in intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis era in Taiwan. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 13525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Z, Wen G, Cao X, et al. Group B Streptococcus colonisation and associated risk factors among pregnant women: a hospital-based study and implications for primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2019; 73: e13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Akkaneesermsaeng W, Petpichetchian C, Yingkachorn M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of group B Streptococcus colonisation in intrapartum women: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 39: 1093–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goel N, Wattal C, Gujral K, et al. Group B Streptococcus in Indian pregnant women: its prevalence and risk factors. Indian J Med Microbiol 2020; 38: 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharmila V, Joseph NM, Arun Babu T, et al. Genital tract group B streptococcal colonization in pregnant women: a South Indian perspective. J Infect Dev Ctries 2011; 5: 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jung Y-J, Huynh B-T, Seck A, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with maternal group B Streptococcus colonization in Madagascar and Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021; 105: 1339–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nkembe NM, Kamga HG, Baiye WA, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in vaginal and anorectal swabs of pregnant women at a tertiary hospital in Cameroon. BMC Res Notes 2018; 11: 480–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hong JS, Choi CW, Park KU, et al. Genital group B Streptococcus carrier rate and serotype distribution in Korean pregnant women: implications for group B streptococcal disease in Korean neonates. J Perinat Med 2010; 38: 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kwatra G, Cunnington MC, Merrall E, et al. Prevalence of maternal colonisation with group B Streptococcus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clouse K, Shehabi A, Suleimat AM, et al. High prevalence of group B Streptococcus colonization among pregnant women in Amman, Jordan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19: 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gizachew M, Tiruneh M, Moges F, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae from Ethiopian pregnant women; prevalence, associated factors and antimicrobial resistance: alarming for prophylaxis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2019; 18: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. El-Kersh TA, Al-Nuaim LA, Kharfy TA, et al. Detection of genital colonization of group B streptococci during late pregnancy. Saudi Med J 2002; 23: 56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ferreira MB, de-Paris F, Paiva RM, et al. Assessment of conventional PCR and real-time PCR compared to the gold standard method for screening Streptococcus agalactiae in pregnant women. Braz J Infect Dis 2018; 22: 449–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen X, Cao S, Fu X, et al. The risk factors for group B Streptococcus colonization during pregnancy and influences of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis on maternal and neonatal outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023; 23: 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease-revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010; 59: 1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stapleton RD, Kahn JM, Evans LE, et al. Risk factors for group B streptococcal genitourinary tract colonization in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moraleda C, Benmessaoud R, Esteban J, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of group B Streptococcus isolated among pregnant women and newborns in Rabat, Morocco. J Med Microbiol 2018; 67: 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jiao J, Wu W, Shen F, et al. Clinical profile and risk factors of group B streptococcal colonization in mothers from the Eastern District of China. J Trop Med 2022; 2022: 5236430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whitney CG, Daly S, Limpongsanurak S, et al. The international infections in pregnancy study: group B streptococcal colonization in pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2004; 15: 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Safari D, Gultom SM, Tafroji W, et al. Prevalence, serotype and antibiotic susceptibility of group B Streptococcus isolated from pregnant women in Jakarta, Indonesia. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0252328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim EJ, Oh KY, Kim MY, et al. Risk factors for group B Streptococcus colonization among pregnant women in Korea. Epidemiol Health 2011; 33: e2011010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen J, Fu J, Du W, et al. Group B streptococcal colonization in mothers and infants in western China: prevalences and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18: 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Manzanares S, Zamorano M, Naveiro-Fuentes M, et al. Maternal obesity and the risk of group B streptococcal colonisation in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 39: 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kfouri RdÁ, Pignatari ACC, Kusano EJU, et al. Capsular genotype distribution of group B Streptococcus colonization among at-risk pregnant women in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis 2021; 25: 101586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li X, Gao W, Jia Z, et al. Characterization of group B Streptococcus recovered from pregnant women and newborns attending in a hospital in Beijing, China. Infect Drug Resist 2023; 16: 2549–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kawaguchiya M, Urushibara N, Aung MS, et al. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women in Japan, 2017–2021. IJID Reg 2022; 4: 143–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Slotved H-C, Dayie NTKD, Banini JAN, et al. Carriage and serotype distribution of Streptococcus agalactiae in third trimester pregnancy in southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17: 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mohamed AM, Khan MA, Faiz A, et al. Group B Streptococcus colonization, antibiotic susceptibility, and serotype distribution among Saudi pregnant women. Infect Chemother 2020; 52: 70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Furfaro LL, Nathan EA, Chang BJ, et al. Group B Streptococcus prevalence, serotype distribution and colonization dynamics in Western Australian pregnant women. J Med Microbiol 2019; 68: 728–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Slotved H-C, Møller JK, Khalil MR, et al. The serotype distribution of Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) carriage isolates among pregnant women having risk factors for early-onset GBS disease: a comparative study with GBS causing invasive infections during the same period in Denmark. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dhanoa A, Karunakaran R, Puthucheary SD. Serotype distribution and antibiotic susceptibility of group B streptococci in pregnant women. Epidemiol Infect 2010; 138: 979–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Karunakaran R, Raja NS, Hafeez A, et al. Group B Streptococcus infection: epidemiology, serotypes, and antimicrobial susceptibility of selected isolates in the population beyond infancy (excluding females with genital tract- and pregnancy-related isolates) at the University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur. J Jpn J Infect Dis 2009; 62: 192–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang Y-H, Lu C-C, Chiu C-H, et al. Genetically diverse serotypes III and VI substitute major clonal disseminated serotypes Ib and V as prevalent serotypes of Streptococcus agalactiae from 2007 to 2012. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2016; 49: 672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lachenauer CS, Kasper DL, Shimada J, et al. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J Infect Dis 1999; 179: 1030–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shabayek S, Abdalla S, Abouzeid AM. Serotype and surface protein gene distribution of colonizing group B Streptococcus in women in Egypt. Epidemiol Infect 2014; 142: 208–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang P, Tong J-J, Ma X-H, et al. Serotypes, antibiotic susceptibilities, and multi-locus sequence type profiles of Streptococcus agalactiae isolates circulating in Beijing, China. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0120035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Botelho ACN, Oliveira JG, Damasco AP, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae carriage among pregnant women living in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, over a period of eight years. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0196925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bobadilla FJ, Novosak MG, Cortese IJ, et al. Prevalence, serotypes and virulence genes of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women with 35–37 weeks of gestation. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Slotved H-C, Hoffmann S. The epidemiology of invasive group B Streptococcus in Denmark from 2005 to 2018. Front Public Health 2020; 8: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Najarian N, Khalili MB, Astani A, et al. Serotype determination of Streptococcus agalactiae detected from vagina and urine of pregnant women in Yazd, Iran-2015. Int J Med Lab 2018; 5: 49–57. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tai-10.1177_20499361251365028 for Prevalence, risk factors, and serotypes of group B Streptococcus rectovaginal colonization among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study at three hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam by Van Le Nguyen, Hung Nguyen Dao, Van Thi Hong Le, An Van Nguyen, Van Thi Thu Ha, Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen, Hoa Thanh Do, Nguyen Thai Son and Do Ngoc Anh in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease

Supplemental material, sj-pptx-2-tai-10.1177_20499361251365028 for Prevalence, risk factors, and serotypes of group B Streptococcus rectovaginal colonization among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study at three hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam by Van Le Nguyen, Hung Nguyen Dao, Van Thi Hong Le, An Van Nguyen, Van Thi Thu Ha, Quynh Thi Nhu Nguyen, Hoa Thanh Do, Nguyen Thai Son and Do Ngoc Anh in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease