Abstract

Background

Alcohol intoxication at the time of index trauma is associated with an increased risk of recurrent traumatic injury. It is unclear, however, whether the degree of intoxication impacts the risk of recurrence or its severity. This study aimed to analyze the relationship between alcohol level at index trauma and risk of recurrent trauma. We hypothesized that increasing levels of alcohol would be associated with an increased risk of trauma recurrence and severity.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults who presented to our Level 1 trauma center between January 2020 and December 2022 with traumatic injury and a positive alcohol level (blood alcohol content (BAC)). The primary outcome of interest was recurrent trauma within 12 months. Secondary outcomes included injury severity score, hospital length of stay, and discharge location. We performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression with class balancing sensitivities controlling for baseline patient characteristics to analyze the association between risk factors and trauma recurrence.

Results

Of the 1,653 trauma encounters across 1,585 patients included in this study, 63 patients (3.8%) experienced re-injury within 12 months. Mean BAC at index trauma was higher among the recurrently injured compared with non-recurrently injured patients (270.0 mg/dL vs 221.0 mg/dL, p<0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that for all-comers increasing BAC was weakly associated with an increased risk of trauma recurrence (OR 1.004, 95% CI: 1.001 to 1.007, p=0.013), but that among the highest tertile of intoxicated patients, increasing BAC was strongly associated with recurrence (OR 2.607, 95% CI: 1.166 to 6.448, p=0.026). Recurrently injured patients were more likely to have at least one medical comorbidity.

Conclusions

We found a differential effect of alcohol intoxication on the risk of trauma recurrence whereby increasing BAC was strongly associated with an increased risk of recurrence only among the most intoxicated patients.

Level of Evidence

III, Prognostic and epidemiological

Keywords: Substance-Related Disorders, Accident Prevention, alcoholism

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death for Americans 45 years and under, and alcohol consumption is a key risk factor for traumatic injury.

Alcohol intoxication at the time of index trauma has also been associated with an increased risk of recurrent trauma in the future.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Previous studies have considered alcohol intoxication as a binary variable, rather than considering the impact of alcohol intoxication on trauma recurrence in a dose-dependent fashion.

In this study of adult trauma patients reporting to an urban, Level 1 trauma center, we found a differential effect of alcohol intoxication on the risk of trauma recurrence such that increasing blood alcohol level was strongly associated with an increased risk of recurrence only among the most intoxicated patients.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE, OR POLICY

Our findings suggest that not all intoxicated patients are at an increased risk of re-injury. Rather, we identified a smaller cohort of high-risk patients who may benefit from additional targeted interventions.

Devoting additional resources—such as a post-discharge follow-up phone call from a social worker trained in substance use counseling—to this cohort may help to reduce the risk of trauma recurrence in this high-risk population.

Introduction

Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death for Americans 45 years and under, and alcohol consumption is a key risk factor for traumatic injury. Alcohol intoxication not only increases the risk of traumatic injury, but also compromises the patient’s physiologic response to injury,1 predisposing patients to poor outcomes.2 3 Epidemiologic studies estimate that approximately 15% of deaths from injury and 11% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost from injury are attributable to alcohol use,4 though the precise relationship between alcohol intoxication and in-hospital mortality after traumatic injury remains incompletely explained, with conflicting results demonstrating both positive and negative associations.5 6

Importantly, the relationship between alcohol and traumatic injury appears to extend beyond the index trauma. Nearly 50% of patients seen in Level 1 trauma centers screen positive for hazardous alcohol use,7 defined as alcohol use that puts them at risk for future alcohol-related problems, and several studies have implicated alcohol use as a risk factor for re-injury. A 1993 study of over 2,500 trauma patients found that patients who were intoxicated at the time of index trauma had a 2.5-fold increased risk of recurrent trauma in the future compared with non-intoxicated patients.8 More recently, a large retrospective cohort study of over 40,000 patients presenting to a Level 1 trauma center over 10 years found that recurrently injured patients were more likely to be male, identify as black, suffer from a penetrating mechanism, and have a blood alcohol content (BAC) greater than 80 mg/dL9 ; the authors further found that trauma recurrence was associated with higher rates of long-term mortality as compared with non-recurrence. These findings, among others, led the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma to mandate that all Level I trauma centers have a mechanism in place not only to identify patients with hazardous alcohol use but also to provide a brief intervention in an attempt to mitigate the risk of re-injury, a process known as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT).10

Previous work has primarily investigated the utility of alcohol intoxication as a binary predictor of recurrent trauma, rather than considering alcohol intoxication in a dose-dependent fashion. It is thus unclear whether the degree of intoxication impacts the risk of trauma recurrence or its severity. Given that alcohol appears to be associated with in-hospital death after injury in a dose-dependent fashion,11 the effect of alcohol intoxication on the risk of re-injury may be similarly dependent on the degree of intoxication. The goal of this study was to analyze the relationship between alcohol level at index trauma and the risk of recurrent trauma in the subsequent year. We hypothesized that increasing levels of alcohol would be associated with an increased risk of trauma recurrence and severity.

Methods

Study design

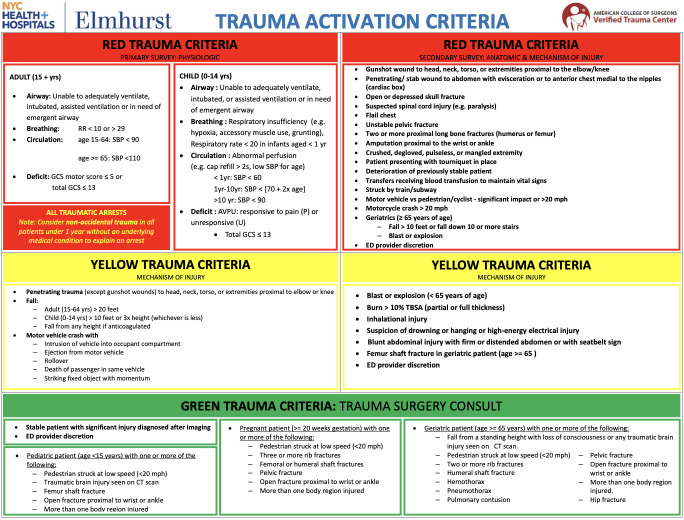

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult patients 18 years or older who presented to our Level 1 trauma center between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2022, with a traumatic injury requiring trauma team activation (figure 1) and a positive BAC (BAC>10 mg/dL). At our institution, BAC level is collected on arrival for all patients 12 years or older who trigger trauma team activation as part of the initial trauma order set. For patients who are retroactively deemed trauma activations, BAC is added on to the initial blood specimens drawn on arrival. Data was collected from our trauma registry, which contains extensive data on patient demographics, injuries, substance use, and clinical outcomes for all trauma patients who present to our emergency department. Within our database, race and ethnicity are categorized according to National Trauma Standard Data Dictionary standards,12 though this schema lacks important nuance, as others have noted.13

Figure 1. Trauma team activation criteria at Elmhurst Hospital. ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; APVU, Alert/Pain/Verbal/Unresponsive; TBSA, total body surface area.

Variables of interest collected from the database included BAC level, sociodemographic factors (age, sex, race, ethnicity), mechanism of injury, injury pattern, initial vital signs, Injury Severity Score (ISS) and Glasgow Coma Scale on presentation, urine toxicology results, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, ICU admission, discharge location, and various medical comorbidities. Urine toxicology laboratory studies are drawn as part of the initial trauma order set for all activated traumas, and results were considered positive if cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, barbiturates, or benzodiazepines were identified in the urine. Medical comorbidities of interest included coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, and cirrhosis and were identified based on manual chart review of the medical record. Sociodemographic variables with missing values were imputed using data from previous visits where available. Both raw numeric BAC levels and BAC categories were reported, with BAC categories (low, medium, high) determined using tertile cut points derived from the sample distribution.

Our primary outcome of interest was recurrent trauma, defined as a repeat presentation for a new traumatic injury within 12 months of the index trauma. This duration of follow-up was chosen because previous research has shown that most re-injury occurs within the first year of index trauma.14 To ensure that this duration of follow-up reflected overall trends, we also separately examined recurrent trauma that occurred more than 12 months after the index trauma. Patients with recurrent trauma were identified within the registry as those encounters deemed to be repeat visits for the same patient (identified by medical record numbers, dates of birth, and demographic characteristics). Based on manual chart review, repeat encounters that were determined to be for the same traumatic encounter rather than a new injury were excluded from the final dataset. Secondary outcomes of interest included hospital outcomes such as hospital and ICU length of stay, discharge location (home, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility, death), and severity of injury during index and recurrent trauma.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. For continuous variables, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare the median values of two groups and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test to compare the median values of three or more groups. Categorical variables were analyzed with the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

Univariable regression analyses were conducted to assess the individual effect of BAC level and of a priori-determined variables related to patient sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, trauma characteristic, and hospital course on the primary and secondary outcomes. ORs, 95% CIs, and p values for the association of each variable with the primary and secondary outcomes were determined. Robust regression models were used, with binomial logistic models for binary outcomes and generalized linear models for continuous outcomes.

Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to analyze the relationship between BAC level and 12-month recurrence. First, we constructed unadjusted models, which examined the association between BAC and 12-month recurrence without controlling for other factors. Then, we constructed adjusted models, which examined the effect of BAC as the primary predictor and controlled potential confounders of the aforementioned variables.

Recurrent trauma was a rare event in the dataset, leading to potential class imbalances in the data. To avoid biases due to class imbalances, we performed additional regression sensitivities in which we tested four class balancing techniques as below.15,18

Weighting using means—balancing by scaling the weight of each class to the inverse of its frequency, assigning higher weights to the minority class and lower weights to the majority class.

Upsampling (oversampling)—randomly subsetting (and replacing with artificial or duplicate data points) the minority classes in the training set so that their class frequency matches the majority class.

Synthetic minority oversampling technique—downsampling the majority class and synthesizing new data of the minority class using the k-nearest neighbor algorithm.

Random oversampling examples—a hybrid method that uses majority downsampling and minority upsampling to synthesize new data of both classes.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to illustrate the models’ predictive performance, and the area under the curve (AUC) and F1 score were calculated to assess discriminative ability with AUC and F1 scores closer to 1 indicating model better performance.19 The 95% CI for the AUC for each model was also calculated. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 for significance at the 95% CI, p<0.01 at the 99% CI, and p<0.001 at the 99.99% CI. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

A total of 1,653 trauma encounters across 1,585 patients were included in this study. Of those, 63 patients (3.8%) experienced re-injury within 12 months (table 1). The majority of patients were male (89.0%), and of Hispanic or Latinx ethnicity (56.0%), with a mean age of 38.1 years. Most patients were victims of blunt trauma (83.0%), and mean ISS was 5. The distribution of our cohort’s ISS is shown in online supplemental file 1. The most common mechanisms of injury included fall, cutting/piercing injuries, and motor vehicle accident, and the most common injury patterns included intracranial and extracranial head injuries, rib fractures, and extremity fractures (online supplemental table 1). The mean BAC for all patients was 220 mg/dL. When all-comers were divided into tertiles based on their BAC at index presentation, patients in the lowest tertile had a BAC ranging from 10 mg/dL to 170 mg/dL, patients in the middle tertile had BAC ranging from 171 mg/dL to 261 mg/dL, and patients in the highest tertile had BAC ranging from 262 mg/dL to 524 mg/dL.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics comparing baseline characteristics of patients who experienced recurrent trauma within 12 months compared with those who did not.

| Characteristic | Overall (n=1,653) |

Recurrence within 12 months (n=63) | No recurrence within 12 months (n=1,590) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAC (mg/dL) | 222.0 (111.5) | 270.0 (120.8) | 221.0 (110.6) | 0·0002* |

| Age | 38.1 (15.4) | 48.9 (15.8) | 37.9 (15.3) | <0·0001* |

| Sex | 0.088 | |||

| Male | 1,463 (89) | 60 (95) | 1,403 (88) | |

| Female | 190 (11) | 3 (4.8) | 187 (12) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 224 (14) | 11 (17) | 213 (13) | |

| Asian | 75 (4.5) | 5 (7.9) | 70 (4.4) | |

| Black | 143 (8.7) | 2 (3.2) | 141 (8.9) | |

| Other | 1,166 (71) | 45 (71) | 1,121 (71) | |

| Unknown | 45 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 45 (2.8) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.730 | |||

| Hispanic | 925 (56) | 35 (56) | 890 (56) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 635 (38) | 26 (41) | 609 (38) | |

| Unknown | 93 (5.6) | 2 (3.2) | 91 (5.7) | |

| Insurance payor | 0.0030* | |||

| Commercial | 221 (13) | 219 (14) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Medicaid | 732 (44) | 693 (44) | 39 (62) | |

| Medicare | 129 (7.8) | 122 (7.7) | 7 (11) | |

| No fault | 78 (4.7) | 78 (4.9) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 113 (6.8) | 113 (7.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 239 (14) | 231 (15) | 8 (13) | |

| Self-pay | 18 (1.1) | 18 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 123 (7.4) | 116 (7.3) | 7 (11) | |

| Mechanism | 0.0071* | |||

| Blunt | 1,366 (83) | 60 (95) | 1,306 (82) | |

| Penetrating | 287 (17) | 3 (4.8) | 284 (18) | |

| ISS | 5.0 (8.0) | 4.0 (4.9) | 5.0 (8.1) | 0.140 |

| Initial vitals | ||||

| Temperature | 98.0 (1.2) | 97.9 (0.6) | 98.0 (1.2) | 0.140 |

| SBP | 130.0 (22.7) | 129.0 (16.8) | 130.0 (22.9) | 0.790 |

| DBP | 82.0 (17.0) | 84.0 (14.3) | 82.0 (17.1) | 0.400 |

| MAP | 98.0 (17.3) | 100.2 (13.0) | 98.0 (17.5) | 0.490 |

| SpO2 | 98.0 (7.0) | 98.0 (1.8) | 98.0 (7.2) | 0.770 |

| GCS | 15.0 (2.8) | 15.0 (2.3) | 15.0 (2.8) | 0.390 |

| Urine toxicology | 0.170 | |||

| Negative | 1 142 (95) | 50 (100) | 1 092 (95) | |

| Positive | 56 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 56 (4.9) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| CAD | 47 (2.8) | 9 (14) | 38 (2.4) | <0·0001* |

| HTN | 267 (16) | 22 (35) | 245 (15) | <0·0001* |

| CHF | 26 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 25 (1.6) | >0.999 |

| DM | 141 (8.5) | 10 (16) | 131 (8.2) | 0.034* |

| COPD | 37 (2.2) | 3 (4.8) | 34 (2.1) | 0.160 |

| CKD | 13 (0.8) | 2 (3.2) | 11 (0.7) | 0.085 |

| CVA | 24 (1.5) | 6 (9.5) | 18 (1.1) | 0·0002* |

| Cirrhosis | 65 (3.9) | 9 (14) | 56 (3.5) | 0·0006* |

| Hospital Course | ||||

| Hospital LOS | 2.0 (14.7) | 2.0 (7.1) | 2.0 (14.9) | 0.730 |

| ICU admission | 446 (27) | 8 (13) | 438 (28) | 0·0091* |

| ICU LOS | 0.0 (3.9) | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.0 (4.0) | >0.999 |

| Vent days | 0.0 (3.6) | 0.0 (0.8) | 0.0 (3.7) | 0·0630 |

| Death within 1 year | 56 (3.4%) | 2 (3.2%) | 54 (3.4%) | >0.999 |

| Discharge status | 0.130 | |||

| Routine to home | 1,271 (77) | 49 (79) | 1,222 (77) | |

| Home with services | 40 (2.4) | 2 (3.2) | 38 (2.4) | |

| Inpatient rehab | 154 (9.3) | 3 (4.8) | 151 (9.5) | |

| Police custody, inpatient psychiatric unit, or homeless shelter | 63 (3.8) | 1 (1.6) | 62 (3.9) | |

| AMA | 80 (4.9) | 7 (11) | 73 (4.6) | |

| Death | 40 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 40 (2.5) |

Values presented as median (SD) or number (percentage).

p<0.05.

AMA, against medical advice; BAC, blood alcohol content; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, stroke or transient ischemic event; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, Injury Severity Score; LOS, length of stay; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

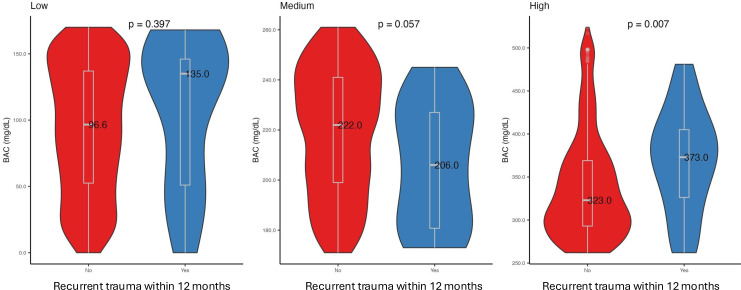

Compared with the non-recurrently injured, recurrently injured patients were more likely to be older (48.9 years vs 37.9 years, p<0.001) and have suffered a blunt injury (95.0% vs 82.0%, p=0.007). Recurrently injured patients were more likely to have a history of coronary artery disease (14% vs 2.4%, p<0.001), hypertension (35% vs 16%, p<0.001), diabetes (16% vs 8.4%, p=0.038), prior stroke (9.5% vs 1.1%, p<0.001), or cirrhosis (14% vs 3.6%, p<0.001). Recurrently injured patients had a significantly higher mean BAC compared with non-recurrently injured (270.0 mg/dL vs 221.0 mg/dL, p<0.001). Results were similar for recurrence within 12 months, recurrence after 12 months, and recurrence at any time (online supplemental figure 2). When BAC was stratified into tertiles, there was no difference in mean BAC among recurrently injured patients compared with non-recurrently injured patients in the lowest (135.09 mg/dL vs 96.0 mg/dL p=0.394) and middle (206.6 mg/dL vs 220.0 mg/dL, p=0.057) tertiles, but in the highest tertile group recurrently injured patients had significantly higher mean BAC compared with non-recurrently injured patients (373.0 mg/dL vs 324.0 mg/dL, p=0.008) (figure 2). There was no significant difference between groups with regards to race, ethnicity, initial vitals, or frequency of positive urine toxicology results. However, urine toxicology results were not available for 461/1,653 (27.8%) of encounters.

Figure 2. Comparison of mean BAC among patients with recurrent injury within 12 months compared with non-recurrently injured patients, stratified by degree of intoxication. BAC, blood alcohol content.

Table 2 shows the results of the univariable regression analyses of absolute BAC level and BAC category on the primary and secondary outcomes. Increased absolute BAC was associated with increased likelihood of recurrent trauma within 12 months (OR 1.005, 95% CI: 1.002 to 1.007, p<0.001); results were similar for recurrence after 12 months and recurrence at any time. When BAC was stratified into tertiles, compared with the lowest tertile, increasing BAC was not significantly associated with the risk of recurrent trauma at 12 months among the middle tertile of intoxicated patients. The effect was, however, significant among those with the highest BAC levels (OR 2.737, 95% CI: 1.463 to 5.434, p<0.001) for recurrent trauma within 12 months. Results were similar for recurrence after 12 months and recurrence at any time. Increased BAC was also significantly associated with slightly increased risk of ICU admission but was not associated with increased ICU length of stay or number of days on ventilator. Among recurrently injured patients, increased BAC on index trauma was associated with a slightly increased risk of increased ISS on subsequent trauma (OR 1.003, 95% CI: 1.001 to 1.005, p=0.017).

Table 2. Univariate analysis of predictive value of BAC on recurrent trauma.

| Any BAC | Medium BAC | High BAC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Recurrence within 12 months | 1.005 | (1.002 to 1.007) | <0.001* | 1.238 | (0.59 to 2.643) | 0.573 | 2.737 | (1.463 to 5.434) | 0.002* |

| Recurrence after 12 months | 1.005 | (1.003 to 1.007) | <0.001* | 1.698 | (0.896 to 3.33) | 0.111 | 3.666 | (2.087 to 6.828) | <0.001* |

| Recurrence at any time | 1.005 | (1.004 to 1.007) | <0.001* | 1.453 | (0.871 to 2.458) | 0.156 | 3.501 | (2.243 to 5.639) | <0.001* |

| Hospital LOS | 1.002 | (0.995 to 1.008) | 0.582 | 1.197 | (−0.54 to 2.935) | 0.177 | 0.302 | (−1.438 to 2.043) | 0.733 |

| ICU admission | 1.002 | (1.001 to 1.003) | 0.001* | 1.361 | (1.035 to 1.791) | 0.028* | 1.577 | (1.205 to 2.07) | 0.001* |

| ICU LOS | 1.001 | (1.000 to 1.003) | 0.123 | 0.429 | (−0.034 to 0.891) | 0.069 | 0.289 | (−0.174 to 0.752) | 0.221 |

| Ventilator days | 1.001 | (0.999 to 1.002) | 0.297 | 0.289 | (−0.141 to 0.72) | 0.188 | 0.231 | (−0.199 to 0.662) | 0.292 |

| ISS index trauma | 0.999 | (0.995 to 1.002) | 0.480 | 0.246 | (−0.726 to 1.217) | 0.620 | −0.171 | (−1.138 to 0.797) | 0.729 |

| ISS recurrent trauma | 1.022 | (1.002 to 1.042) | 0.029* | 0.491 | (−7.029 to 8.01) | 0.896 | 5.662 | (−0.286 to 11.611) | 0.062 |

| Death within 12 months | 1.003 | (1.001 to 1.005) | 0.017* | 0.879 | (0.429 to 1.781) | 0.720 | 1.439 | (0.769 to 2.751) | 0.260 |

For BAC categories, reference level is low BAC.

p<0.05.

ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, Injury Severity Score; LOS, length of stay.

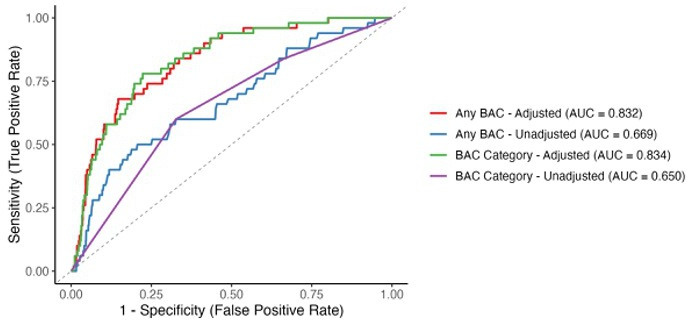

Multivariate analysis revealed a similar effect of BAC on risk of recurrent trauma. For all-comers, increasing BAC was associated with a slightly increased risk of trauma recurrence within 12 months (OR 1.004, 95% CI: 1.001 to 1.007, p=0.013) (table 3). When BAC was stratified into tertiles, compared with the lowest tertile, increasing BAC was not significantly associated with the risk of recurrent trauma within 12 months among the middle tertile of intoxicated patients (OR 1.406, 95% CI: 0.555 to 3.744, p=0.477) but was strongly associated with an increased risk among the highest tertile of intoxicated patients (OR 2.607, 95% CI: 1.166 to 6.448, p=0.026). Results were similar for recurrence after 12 months (online supplemental table 2) and recurrence at any time (online supplemental table 3). When the cohort was stratified by age, the effect remained for patients younger than 40 years of age but not for those older than 40 years (online supplemental table 4). Of the other covariates in our adjusted models, only a medical history of cirrhosis showed a significant association with recurrent trauma within 12 months (OR 5.042, 95% CI: 1.770 to 13.107, p=0.001). The adjusted multivariate models demonstrated strong discriminative ability (figure 3), with AUC=0.832 and F1=0.982 for any BAC and AUC=0.834 and F1=0.982 when BAC was stratified into tertiles, indicating robust predictive power. Again, results were similar for recurrence after 12 months (online supplemental figure 3) and recurrence at any time (online supplemental figure 4). Results were also similar after class balancing sensitivities were applied, though the magnitude of the effect of increasing BAC on the risk of trauma recurrence was greater after class balancing (online supplemental table 5). ROC and performance statistics of the class-balanced models can be found in online supplemental table 6 and online supplemental figure 5 for the models analyzing any BAC and in online supplemental table 7 and online supplemental figure 6 for those analyzing BAC by tertile.

Table 3. Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with recurrent trauma within 12 months.

| Parameter | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAC | |||

| All | 1.004 | (1.001 to 1.007) | 0.013* |

| Low | Ref | – | – |

| Medium | 1.406 | (0.555 to 3.744) | 0.477 |

| High | 2.607 | (1.166 to 6.448) | 0.026* |

| Age | 1.021 | (0.995 to 1.046) | 0.107 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Ref | – | – |

| Female | 0.252 | (0.039 to 0.887) | 0.068 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | Ref | – | – |

| Non-Hispanic | 1.337 | (0.695 to 2.551) | 0.378 |

| Mechanism | |||

| Penetrating | 0.476 | (0.111 to 1.414) | 0.237 |

| Blunt | Ref | – | – |

| ISS | 1.002 | (0.934 to 1.067) | 0.956 |

| Medical history | |||

| CAD | 3.157 | (0.885 to 9.827) | 0.057 |

| HTN | 1.569 | (0.687 to 3.49) | 0.276 |

| CHF | 0.608 | (0.03 to 3.983) | 0.661 |

| DM | 0.792 | (0.287 to 1.957) | 0.630 |

| COPD | 1.782 | (0.365 to 6.535) | 0.419 |

| CKD | 4.137 | (0.462 to 25.254) | 0.150 |

| CVA | 2.432 | (0.336 to 10.991) | 0.297 |

| Cirrhosis | 5.042 | (1.77 to 13.107) | 0.001* |

Adjusted for age, sex, ISS, mechanism of injury, and number of comorbidities.

GCS, p<0.05.

AMA, against medical advice; BAC, blood alcohol content; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, stroke or transient ischemic event;; DM, diabetes mellitus; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HTN, hypertension; ISS, Injury Severity Score.

Figure 3. Receiver operating curve for the multivariable logistic regression model examining the relationship between BAC and trauma recurrence within 12 months. AUC, area under the curve; BAC, blood alcohol content.

Discussion

In our study of trauma victims presenting to a single Level 1 Trauma Center in New York City, we found that approximately 4% of patients experienced re-injury within 12 months, and that recurrently injured patients were more likely to be older, suffer from a blunt injury, have at least one medical comorbidity, and have a significantly higher BAC compared with non-recurrently injured patients. On multivariate analysis, we found that there was a differential effect of BAC on the risk of trauma recurrence when patients were stratified by degree of intoxication, such that only among the highest tertile of intoxicated patients was increasing BAC associated with an increased risk of recurrence, both within 12 months and beyond. This effect persisted even after class balancing sensitivities were applied but only for patients younger than 40 years old.

Overall, the rate of recurrent trauma in our study was slightly lower than other prior studies. Strong et al, for example, reported a re-injury rate of approximately 7% among more than 40,000 patients who presented to a Level 1 Trauma Center in Baltimore, Maryland, USA.9 Notably, however, re-injury in that study was defined as a repeat traumatic injury anytime during the 10-year follow-up period, whereas the definition of recurrent trauma in our study was limited to re-injury within 12 months. The lower overall rate of recurrent trauma in our study may also be related to the unique healthcare landscape of New York City. Whereas many cities may have one or two Level 1 centers to which trauma patients are directed, there are over 10 Adult Level 1 trauma centers in the New York City area. In our study, we focused on patients who presented to a single center with recurrent traumatic injury, but it is conceivable that patients may have experienced recurrent injury and been transported to a different trauma center in the city, which would not be captured in our study, thereby lowering our reported recurrence rate. Strong et al also found that recurrently injured patients had higher rates of long-term mortality compared with non-recurrently injured patients. Median time to death for re-injured patients in their cohort was 2.0 years for injury-related death and 2.8 years for disease-related death.9 In our study, we found no difference in death within 1 year for recurrently injured compared with non-recurrently injured, which suggests that the impact of recurrent trauma on long-term mortality noted by Strong and colleagues may evolve during the course of years, not months.

Prior studies have identified alcohol intoxication as a binary risk factor for recurrent trauma,9 and we similarly found a weak association between overall BAC and risk of trauma recurrence. However, our finding that when BAC was stratified by level, the effect on trauma recurrence was strongly significant only among the most intoxicated patients adds to the growing body of research demonstrating the complex effects of alcohol use on trauma outcomes and suggests a more complex relationship between alcohol use and recurrent trauma than previous data suggests. Indeed, we are not the first group to report a differential effect of alcohol intoxication on trauma outcomes based on degree of intoxication. A 2015 study of trauma patients examining the effect of BAC on in-hospital death identified a varying association whereby moderate alcohol intoxication (BAC 1–100 mg/dL) was associated with a 1.5× increased risk of in-hospital death after trauma, whereas high (BAC 101–230 mg/dL) or very high (BAC>230 mg/dL) levels of intoxication were associated with decreased risk of in-hospital death.11 The authors postulated that such a differential effect may be related to the type and severity of traumatic injuries that patients are likely to experience at different levels of intoxication.

Currently, many trauma centers use BAC to screen and intervene on patients with hazardous alcohol in an effort to reduce the risk of trauma recurrence. At our institution, all trauma admissions 12 years or older are screened for alcohol use using either BAC or a validated verbal screening tool such as the CAGE (for adults)20 or CRAFFT (for adolescents)21 questionnaires. Any patient who screens positive (BAC>10 mg/dL) is provided with both a brief intervention conducted by the social worker according to best practice guidelines22 and with resources for outpatient addiction treatment. Trauma team members also have the option of calling an addiction medicine consult. The addiction medicine service is a multidisciplinary team composed of addiction medicine physicians, social workers, mental health counselors, and peer advocates and can provide additional targeted interventions such as bedside counseling, recommendations for medical management of withdrawal, and patient education to improve treatment engagement.

Our findings suggest that not all intoxicated patients are at an increased risk of re-injury, and we instead have identified a smaller cohort of young, high-risk patients who may benefit from additional targeted interventions. Given the somewhat low mean ISS score of our cohort, our findings suggest that using even minor index traumas as opportunities to address problematic alcohol use among heavy users may effectively mitigate re-injury risk. Critically, these findings should not be viewed as justification to narrow the scope of SBIRT use to only the most severely intoxicated. The primary goal of SBIRT is to reduce hazardous drinking, and re-injury represents only one sequela of such drinking. Multiple studies have demonstrated the short-term effectiveness of SBIRT in decreasing the rates of problematic alcohol use when implemented in a primary care,23 inpatient,24 or emergency room25 setting. Rather, we argue that the addition of a targeted intervention aimed specifically at the most intoxicated patients might yield a significant reduction in trauma recurrence. One such simple, low-cost, evidence-based intervention is the addition of a follow-up phone call 3 months after discharge. One pilot study of over 1800 trauma patients found that an SBIRT program that consisted of not only a brief intervention during the initial trauma encounter but also a subsequent telephone follow-up conducted by an individual trained in motivational interviewing produced a durable reduction in trauma recurrence up to 4 years later.26 The authors posit that their ability to produce a durable reduction in re-injury when other programs have not24 was due to their addition of the long-term follow-up phone call, after recovery from the index injury has occurred, when motivation to limit substance use tends to decrease.

Interestingly, we also found that patients with recurrent trauma were more likely to have at least one medical comorbidity such as diabetes, prior stroke, or cirrhosis, and that after controlling for other factors those with cirrhosis have an increased risk of trauma recurrence. This may reflect an association of chronic alcohol use (with cirrhosis as a proxy) and recurrent trauma. Although medical comorbidities have previously been associated with worse outcomes after traumatic injury,27 to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between medical comorbidities and risk of trauma recurrence. The mechanism behind such a connection remains unclear; given the known links between socioeconomic status and poor health,28 and between socioeconomic status and risk of trauma,29 30 our finding may reflect the fact that those with medical comorbidities are more likely to come from a vulnerable population, which simultaneously places them at an increased risk of trauma in the future. Although we do not collect detailed sociodemographic or housing data as part of our trauma database, we do know that the majority of our patients come from Queens County, New York, an extremely diverse region where per US Census data 8.7% of adults under age 65 years of age are uninsured, 13.8% of people live in poverty, and 47.6% of people identify as foreign.31

The findings of our study must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Most notably, by nature of our retrospective, single-center design, it is conceivable that we may have failed to capture some patients who experienced recurrent injury within our study period but presented to an alternate New York City trauma center. As discussed already, the unique healthcare landscape of New York City makes it such that re-injured patients may be directed to a different trauma center with each recurrence depending on the geographic location of the incident, the emergency medical service provider, and each hospital’s capacity level. Second, the average BAC of intoxicated trauma patients in our study population (220 mg/dL) was significantly higher than that previously reported in the literature, with one large study (n=12,535) of trauma patients with alcohol exposure reporting a mean BAC of 167 mg/dL.11 Clinically, this difference in intoxication is significant; although patients with a BAC of approximately 160 mg/dL may experience nausea and speech impairment, a patient with a BAC of 220 mg/dL may experience significant intoxication with confusion, memory loss, gross motor impairment, and stupor. Our study population is thus somewhat unique compared with the national average. Third, BAC at the time of presentation to the emergency department is an imperfect measurement of alcohol intoxication, as BAC decreases as time passes and alcohol is metabolized. Depending on when an intoxicated patient experiences their traumatic injury and how long it takes for the patient to present to the emergency department, BAC may not be a marker of their degree of intoxication at the time of injury. Lastly, as a single-center study, our sample size limits its statistical power and ability to perform additional subgroup analysis. As previously mentioned, the mean ISS of our cohort was somewhat lower than other studies examining trauma recurrence, which may reflect local conditions and limit generalizability. Future work with a larger cohort might consider stratifying patients by degree of injury to see if this differential effect of alcohol on trauma recurrence is impacted by injury severity.

Conclusion

In our study population, recurrently injured patients had significantly higher BAC on index trauma compared with non-recurrently injured patients and were more likely to have significant medical comorbidities. For all comers, multivariate analysis demonstrated that increasing BAC was weakly associated with an increased risk of trauma recurrence, but this effect was modulated by the degree of intoxication such that among the most intoxicated patients, increasing BAC was strongly associated with an increased risk of recurrent trauma.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by our center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 24-12-087) with waiver of consent for Research of Existing Data/Records/Specimens.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Moore EE. Alcohol and Trauma: The Perfect Storm. Journal of Trauma. 2005;59:S53–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174868.13616.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Seguin D, Fligner CL, Ries R, Raisys VA, Copass M. The magnitude of acute and chronic alcohol abuse in trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1993;128:907–12. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200081015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayman AV, Crandall ML. Deadly partners: interdependence of alcohol and trauma in the clinical setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:3097–104. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6123097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shield KD, Gmel G, Patra J, Rehm J. Global burden of injuries attributable to alcohol consumption in 2004: a novel way of calculating the burden of injuries attributable to alcohol consumption. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondell RD, Looney SW, Krieg CL, Spain DA. A comparison of alcohol-positive and alcohol-negative trauma patients. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:380–3. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaghoubian A, Kaji A, Putnam B, Virgilio N, Virgilio C. Elevated blood alcohol level may be protective of trauma patient mortality. Am Surg. 2009;75:950–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, Villaveces A, Copass M, Ries RR. Alcohol Interventions in a Trauma Center as a Means of Reducing the Risk of Injury Recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230:473. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivara FP. The Effects of Alcohol Abuse on Readmission for Trauma. JAMA . 1993;270:1962. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510160080033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strong BL, Greene CR, Smith GS. Trauma Recidivism Predicts Long-term Mortality: Missed Opportunities for Prevention (Retrospective Cohort Study) Ann Surg. 2017;265:847. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodadek LM, Freeman JJ, Tiwary D, Drake MD, Schroeder ME, Dultz L, et al. Alcohol-related trauma reinjury prevention with hospital-based screening in adult populations: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma evidence-based systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:106. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afshar M, Netzer G, Murthi S, Smith GS. Alcohol exposure, injury, and death in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:643–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American college of surgeons . National Trauma Data Standard (NTDS) Data Dictionary. 2025. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/quality/national-trauma-data-bank/national-trauma-data-standard/ Available. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahmias J, Zakrison TL, Haut ER, Gurney O, Joseph B, Hendershot K, Ghneim M, Stey A, Hoofnagle MH, Bailey Z, et al. Call to Action on the Categorization of Sex, Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in Surgical Research. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:316–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann CR, Branas CC, Brawley ML. A population-based study of trauma recidivism. J Trauma. 1998;45:325–31. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199808000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lunardon N, Menardi G, Torelli N. ROSE: a Package for Binary Imbalanced Learning. R J. 2014;6:79. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2014-008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menardi G, Torelli N. Training and assessing classification rules with imbalanced data. Data Min Knowl Disc. 2014;28:92–122. doi: 10.1007/s10618-012-0295-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J Stat Soft. 2008;28 doi: 10.18637/jss.v028.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. jair. 2002;16:321–57. doi: 10.1613/jair.953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tharwat A. Classification assessment methods. ACI. 2021;17:168–92. doi: 10.1016/j.aci.2018.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300:2054–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of Brief Alcohol Screening Tests Among Adolescents: A Comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcoholism Clin &Amp; Exp Res. 2003;27:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2003.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Screening BJ. Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abuse. 2007;28:7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaner EFS, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:CD005191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O’Connor PG. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordovilla-Guardia S, Fernández-Mondéjar E, Vilar-López R, Navas JF, Portillo-Santamaría M, Rico-Martín S, Lardelli-Claret P. Effect of a brief intervention for alcohol and illicit drug use on trauma recidivism in a cohort of trauma patients. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glynn R, Edwards F, Wullschleger M, Gardiner B, Laupland KB. Major trauma and comorbidity: a scoping review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg . 2025;51:133. doi: 10.1007/s00068-025-02805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkbuli A, Yaras R, Elghoroury A, Boneva D, Hai S, McKenney M. Comorbidities in Trauma Injury Severity Scoring System: Refining Current Trauma Scoring System. Am Surg. 2019;85:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kauffman J, Nance M, Cannon JW, Sakran JV, Haut ER, Scantling DR, Rozycki G, Byrne JP. Association of pediatric firearm injury with neighborhood social deprivation in Philadelphia. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open . 2024;9:e001458. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2024-001458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep . 2014;129:19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United States Census Buraeu Census bureau quickfacts. 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/queenscountynewyork/PST045224 Available.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.