Abstract

Background

Imposter syndrome (IS) refers to a psychological condition marked by ongoing self-doubt and an underlying fear of being perceived as incompetent, even when there is clear evidence of success. IS is notably prevalent among medical students and is associated with negative outcomes such as profound stress, burnout, and impaired academic performance. Mindfulness, a practice that involves being fully present in the moment, cultivating awareness, and accepting thoughts without judgment, is suggested to reduce feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. However, no study has explored the association between mindfulness and IS among medical students. This study aims to determine the prevalence of IS in medical students and explore its associations with mindfulness and engagement in extracurricular activities.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 545 medical students from the Marmara University School of Medicine. The Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale and the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale were used to assess IS and mindfulness, respectively. Participation in extracurricular activities was defined as engagement in at least one hour per week of sports, social or artistic activities.

Results

The median age of the participants was 22 years, and 58% (n=316) were female. IS was present in 39.3% (95% CI: 35.1%-43.5%) of the participants. Students with higher mindfulness scores (OR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.27–0.49) and those who engaged in extracurricular activities (OR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.07–2.33) presented significantly lower levels of imposter syndrome (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that mindfulness and engagement in extracurricular activities is associated with lower IS scores, suggesting a potential protective role in medical students. These findings highlight the need for mindfulness-based interventions in medical education to support student well-being. Medical schools should consider integrating structured mindfulness programs and promoting extracurricular engagement as potential strategies to mitigate IS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07773-9.

Keywords: Imposter syndrome, Medical students, Mindfulness, Extracurricular activities

Introduction

Among the many challenges faced, impostor syndrome (IS) is a psychological phenomenon in which individuals question their achievements and have a persistent fear of being exposed as impostors. It has recently been recognized as a significant contributor to medical students’ psychological distress. IS is characterized by self-doubt, fear of being discovered as a fraud, and an inability to internalize successes [1]. Moreover, a competitive academic atmosphere places high-performing students at increased risk of developing IS, which has been identified as a key predictor of psychological distress [2–5].

Research indicates that a large proportion of medical students experience IS at some point during their education, potentially leading to chronic stress, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem [6–10]. If left undetected, these feelings may impair academic performance, diminish clinical confidence, and lead to burnout [11]. Given the increasing awareness of mental health challenges within medical education, there is growing interest in strategies that can promote resilience and psychological well-being. One such strategy is mindfulness, which involves present-moment awareness with nonjudgmental acceptance and the practice of being fully present, often used as a therapeutic tool. Studies have suggested that mindfulness not only helps individuals manage stress but can also reduce feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt, making it a potential mitigating factor for IS [12].

Previous research on IS has reported varying prevalence rates among medical students, with studies indicating figures as high as 82% in some contexts [9]. For instance, a systematic review revealed that while certain populations exhibit heightened susceptibility to IS, factors such as cultural context and academic environment play a crucial role in these variations [13]. Our study offers a localized perspective by assessing IS prevalence among medical students in Türkiye, where specific cultural and societal dynamics may shape students’ experiences. Although prior research has explored the potential of mindfulness in reducing IS [14], few studies have focused on medical students, particularly in non-Western contexts. This study addresses those gaps to enhance understanding of IS and mindfulness and inform supportive strategies.

The mental health and overall well-being of medical students have become increasingly important issues within higher education on a global scale [15]. Recent research has indicated that medical students exhibit elevated levels of mental health issues [16–18]. This finding highlights the need for medical schools to take proactive measures to support student well-being and gain a deeper understanding of both the risk and protective factors involved. Various explanations have been proposed for the significant mental health challenges faced by medical students. Factors such as overwhelming stress levels, demanding expectations, intense competition, perfectionism, and pressures of clinical practice, with heavy workloads, fear of errors, and fear of uncertainty, are thought to contribute to students’ psychological distress [19, 20]. Moreover the organizational culture within medical education, which often emphasizes perfectionism and fear of failure, can exacerbate IS among students [21].

Research specifically examining the relationship between IS and mindfulness has focused on broader student or professional populations [14, 22]. However, to date, no study has specifically examined the relationship between IS and mindfulness in medical students. This study specifically focused on mindfulness due to its growing relevance in medical education and its potential role as a modifiable protective factor against psychological distress. While constructs such as self-esteem, perfectionism, and anxiety are also associated with imposter syndrome, our study aimed to explore mindfulness because it can be actively cultivated through structured programs, and thus holds practical implications for supporting the well-being of medical students.

Therefore, we hypothesize that higher mindfulness levels and engagement in extracurricular activities are associated with lower IS scores in medical students. By understanding this association, we hope to provide insights into how medical education can better support students’ mental health.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted among medical students at the Marmara University School of Medicine in Istanbul, Türkiye. The study targeted students enrolled in a 6-year integrated medical program. In this curriculum, the first three years predominantly focus on preclinical education, which is delivered in a classroom setting on the campus. From the fourth year onward, the curriculum shifted to a predominantly clinical focus, with most training in hospitals or other clinical environments. Clinical trial number: not applicable.

Study population and sample

All students at the Marmara University School of Medicine were invited to participate in the study. A total of 1,406 students were enrolled in the program at the time of data collection. No sample selection process was applied, as all the students were invited via an online platform to voluntarily participate in the study. A total of 545 students were included in the study with a response rate of 38.8%. In our study, there was no exclusion criteria, as the aim was to assess the prevalence and associated factors of IS among a diverse population of medical students. Including all students, regardless of pre-existing mental health conditions, allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the studied relationships.

Data collection

Data were collected via an online questionnaire. The survey was divided into two sections. The first section consisted of sociodemographic questions and additional items (explained in more detail below) developed by the researchers on the basis of a thorough review of the relevant literature. The second section included two validated instruments: the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) and the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). The sociodemographic survey instrument was developed by the authors based on a review of the relevant literature and expert opinion. Prior to data collection, the survey was pilot tested with a group of 15 medical students to ensure clarity and content validity. Minor revisions were made based on the feedback received. Data were collected between January- April 2024.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable, IS, was assessed via the CIPS, a tool developed by Clance and Imes [1]. This scale consists of 20 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, with each item scored from 1 to 5 points. The total score ranges from 20 to 100. On the basis of the total score, respondents can be classified as follows:

≤ 40: Low level of IS.

> 40–62: Moderate level of IS.

≥ 62–81: Frequent feelings associated with IS.

≥ 81: Severe IS.

Turkish validation of the CIPS was conducted by Şahin and Gülşen [23]. Although there are no normative data providing a definitive cutoff point for the CIPS, on the basis of previous literature, a score of 62 was used in this study as the cutoff. Students scoring 62 or higher were classified as experiencing IS [24–26].

Independent variables

Mindfulness was measured via the MAAS, developed by Brown and Ryan in 2003. This 15-item scale assesses individuals’ general tendency to be attentive to and aware of their moment-to-moment experiences in daily life [26]. The MAAS is a Likert-type scale, with response options ranging from 1 (“almost always”) to 6 (“almost never”). Each of the 15 items are added to obtain a total score, and the total score is then divided by 15 to obtain the mean, which ranges from 1 to 6. A higher score indicates a higher level of mindfulness, as it suggests a lower frequency of mind-wandering and greater present-moment awareness. The final scores are categorized as “very poor” (1.00–1.99), “poor” (2.00–2.99), “fair” (3.00–3.99), “good” (4.00–4.99), “very good” (5.00–5.99) and “excellent” (6.00).

The scale has a single-factor structure, with higher total scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The Turkish version of the MAAS was validated by Özyeşil et al. [27].

Other independent variables

Other independent variables were gender, age, parental education level, year of education, place of residence (e.g., dormitory, family home), scholarship status, engagement in regular sports, social, or artistic activities (at least one hour per week), and daily social media usage time (e.g., Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, TikTok). Extracurricular activities in medical education are student-driven, non-compulsory activities that complement formal training. For the purposes of this study, extracurricular activities were defined as regular engagement in sports, social, or artistic activities for at least one hour per week. The extracurricular activity was assessed using a single-item self-report.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables are summarized as medians and interquartile ranges because of the nonnormal distribution of the data. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Continuous variables for two or more than two groups were analyzed via the Mann‒Whitney U test or the Kruskal‒Wallis test, respectively. Logistic regression was used for univariate and multivariate analyses to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Marmara University School of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Protocol Code: 09.2023.1400, Date: 03.11.2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Among the 1406 students enrolled in medical school, 545 returned questionnaires, for a response rate of 38.8%. Male students (n = 229) accounted for 42% of the participants, whereas female students (n = 316) accounted for 58%. The median (25–75th percentiles) age of the participants was 22 (20,00–23,00) years. Among the participants, 52.1% (n = 284) were receiving a scholarship, 62.2% (n = 339) were regularly participating in sports, social, or artistic activities (at least 1 h per week), and 38.5% (n = 210) were spending more than 3 h on social media (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 316 | 58.0 |

| Male | 229 | 42.0 | |

| Year of study | 1 | 81 | 14.9 |

| 2 | 100 | 18.3 | |

| 3 | 109 | 20.0 | |

| 4 | 58 | 10.6 | |

| 5 | 99 | 18.2 | |

| 6 | 98 | 18.0 | |

| Preclinical/Clinical | Preclinical | 290 | 53.2 |

| Clinical | 255 | 46.8 | |

| Mother’s education level | Literate/illiterate | 27 | 5.0 |

| Primary/Middle school | 113 | 20.7 | |

| High School | 112 | 20.6 | |

| University | 293 | 53.8 | |

| Father’s education level | Literate/illiterate | 7 | 1.3 |

| Primary/Middle school | 73 | 13.4 | |

| High School | 90 | 16.5 | |

| University | 375 | 68.8 | |

| Receiving a Scholarships | Yes | 284 | 52.1 |

| No | 261 | 47.9 | |

| Regular Participation in Sports, Social, or Artistic Activities (At Least 1 h per Week) | Yes | 339 | 62.2 |

| No | 206 | 37.8 | |

| Daily Time Spent on Social Media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, TikTok) | Less than 1 h | 69 | 12.7 |

| 1 to 3 h | 266 | 48.8 | |

| More than 3 h | 210 | 38.5 | |

| MAAS scores | 1.00-1.99 (very poor) | 13 | 2.4 |

| 2.00- 2.99 (poor) | 129 | 25.5 | |

| 3.00-3.99 (fair) | 272 | 49.9 | |

| 4.00-4.99 (good) | 106 | 19.4 | |

| 5.00-5.99 (very good’’) | 14 | 2.6 | |

| 6.00 (excellent) | 1 | 0.2 | |

The Cronbach’s alpha values for the CIPS and MAAS were 0.90 and 0.86, respectively.

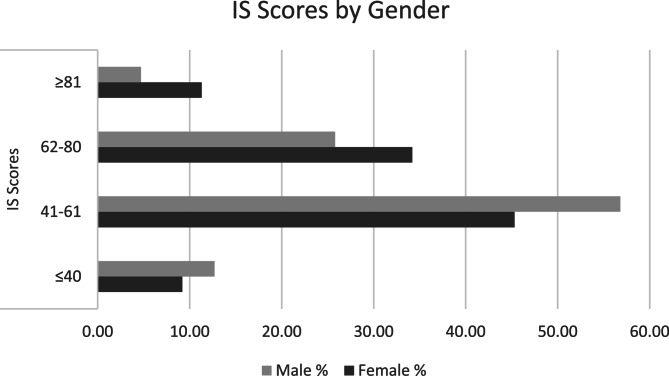

IS was present in 39.3% (95% CI: 35.1%−43.5%) of the participants (n = 214). Compared with males, females presented higher levels of IS (45. 6% vs. 30. 6%, p < 0.001). Figure 1 presents the distribution of IS scores by gender.

Fig. 1.

IS Categories by Gender. P = 0.002

IS was present in 40% (n = 116) of preclinical students and 38.4% (n = 98) of clinical students (p = 0.70) (p > 0.05).

The mean MAAS score was 3.41 (SD = 0.74). Among the participants, 13 (2.4%) were “very poor”; 129 (25.5%) were “poor”; 272 (49.9%) were “fair”; 106 (19.4%) were “good”; 14 (2.6%) had “very good”; and 1 (0.2%) had “excellent” MAAS scores.

Males had a higher score compared to their female counterparts. Female participants had a mean of 3.30 (SD = 0.74), while male participants had a mean of 3.56 (SD = 0.73) (p < 0.001).

Preclinical students had a mean of 3.43 (SD = 0.71), and clinical students had a mean of 3.39 (SD = 0.79) (p = 0.40).

Univariate analysis

Compared with male students, female students were significantly more likely to experience IS (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.33–2.72, p = 0.001). Students who did not engage in regular sports, social, or artistic activities were also more likely to have IS than those who did (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.22–2.48, p = 0.002). Students who spent more than 3 h per day on social media were significantly more likely to experience IS than those who spent less than 1 h (OR: 2.10, 95% CI: 1.17–3.78, p = 0.01). Higher mindfulness scores were significantly associated with lower odds of IS (OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.91–0.95, p < 0.001). No significant associations were found for preclinical versus clinical stage, parental education level, or scholarship status (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with IS, univariate analysis

| IS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref. | ||

| Female | 1.90 | 1.33- 2.72 | 0.001 |

| Regular Participation in Sports, Social, or Artistic Activities (At Least 1 Hour per Week) | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.74 | 1.22 - 2.48 | 0.002 |

| Daily Time Spent on Social Media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, TikTok | |||

| Less than 1 hour | Ref. | ||

| 1 to 3 hours | 1.40 | 0.79- 2.50 | 0.24 |

| More than 3 hours | 2.10 | 1.17 – 3.78 | 0.01 |

| Preclinical/Clinical | |||

| Preclinical | Ref. | 0.66- 1.32 | |

| Clinical | 0.93 | 0.70 | |

| Mother’s education level | |||

| Literate/illiterate | Ref. | ||

| Primary/Middle school | 0.63 | 0.27 – 1.48 | 0.29 |

| High School | 0.49 | 0.20 - 1.15 | 0.10 |

| University | 0.79 | 0.35 - 1.74 | 0.55 |

| Father’s education level | |||

| Literate/illiterate | Ref. | ||

| Primary/Middle school | 0.41 | 0.08 – 1.99 | 0.27 |

| High School | 0.54 | 0.11 – 2.59 | 0.44 |

| University | 0.47 | 0.10 – 2.16 | 0.33 |

| Receiving a Scholarship | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.04 | 0.74 – 1.47 | 0.79 |

| MAAS score | 0.35 | 0.26 – 0.46 | <0.001 |

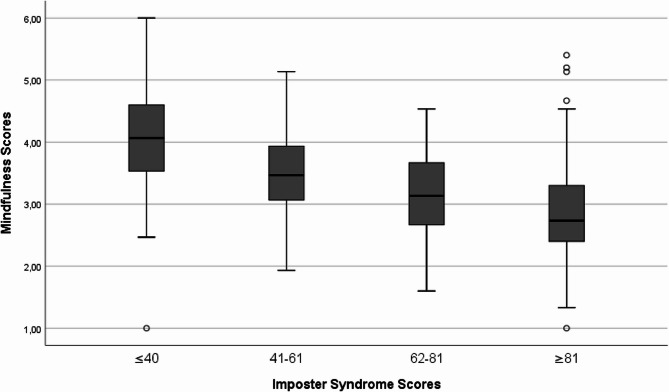

Figure 2 presents the MAAS scores by IS categories. The observed downward trend suggests that higher levels of IS are associated with lower mindfulness levels (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

IS Categories by MAAS scores. p < 0.001

Multivariate analysis

Gender, mindfulness score, daily social media usage, and participation in regular sports, social, or artistic activities were included in the multivariate model. Compared with males, females had an OR of 1.40 (95% CI: 0.95–2.07, p = 0.08) for having IS. While gender was associated with imposter syndrome in the univariate analysis, this association was attenuated and lost statistical significance when controlling for mindfulness (MAAS) and other confounders. For those using social media for 1–3 h daily, the OR was 1.27 (p = 0.45), and for those using it for more than 3 h, the OR was 1.52 (p = 0.20), neither indicating significant risk. A significant positive association was observed for students who did not engage in sports or social activities (p = 0.02), with an OR of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.07–2.33). A significant negative association was found between mindfulness scores and IS (p < 0.001) (OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.91–0.95) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with IS, multivariate analysis

| IS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref. | ||

| Female | 1.40 | (0.95- 2.07) | 0.08 |

| MAAS scores | 0.36 | (0.27- 0.49) | <0.001 |

| Daily Time Spent on Social Media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, TikTok) | |||

| Less than 1 hour | Ref. | ||

| 1 to 3 hours | 1.27 | (0.67 – 2.38) | 0.45 |

| More than 3 hours | 1.52 | (0.79 – 2.89) | 0.20 |

| Regular Participation in Sports, Social, or Artistic Activities (At Least 1 Hour per Week) | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.58 | (1.07- 2.33) | 0.02 |

Discussion

This study adds to the limited literature by investigating how mindfulness and extracurricular engagement relate to IS among medical students. In addition, this is the first study to determine the prevalence of IS among medical students in Türkiye. Our findings revealed a notably high prevalence (39.3%) of IS, which aligns with previous research. In the literature, the prevalence rates of IS range between 9% and 82%, largely depending on the screening tool and cutoff points used to assess symptoms [8]. Owing to differences in measurement tools and cutoff points, comparisons across studies are challenging. Nevertheless, IS incidence appears to be notably high in medical students. In their study, Houseknecht et al. reported that over half (54%) of incoming medical students experienced IS, which significantly increased by the end of their third and fourth years. Another study reported that 87% of first-year medical students experienced high or very high levels of IS, with scores increasing from the beginning to the end of the academic year. In our study, IS prevalence did not differ significantly between preclinical and clinical students. Early interventions in medical curricula may help students recognize and manage IS, reducing its impact on academic outcomes and mental health. Creating a psychologically safe environment is essential for mitigating the effects of IS [11, 28].

Although gender differences in IS were observed in the univariate analysis, this association was not statistically significant in the multivariate model. Nevertheless, prior literature has reported higher IS prevalence among female students [29, 30], possibly reflecting gendered experiences in academic settings. In Türkiye, societal expectations may place additional pressures on female students, such as balancing academic and familial roles or facing underrepresentation in leadership [13, 31]. These dynamics warrant further investigation using qualitative or mixed-methods approaches.

Türkiye has a more collectivist cultural framework compared to the individualistic ethos in many Western countries. Türkiye’s cultural and educational environment differs significantly from Western countries in ways that could influence both IS and mindfulness practices among medical students. High parental investment in education may lead students to internalize a fear of failure, feeling that their achievements reflect not just on them but also on their families.

Medical students may feel a strong obligation to succeed, amplifying self-doubt and the fear of being “exposed” as inadequate.

In contrast, Western cultures emphasize individual achievements, which, while still fostering IS, may allow more room for self-validation without excessive external pressure [13].

Our study revealed a significant inverse relationship between mindfulness and IS among medical students. Students who reported higher levels of mindfulness tended to experience lower levels of IS. A one-unit increase in MAAS scores is associated with a decreased likelihood of imposter syndrome, with an odds ratio of 0.36 and a relatively narrow confidence interval. This suggests that improved mindfulness may positively influence psychological well-being, indicating potential benefits for overall mental health. Research on the relationship between mindfulness and the impostor phenomenon has been limited. Pastan et al. reported that frequent or intense impostor feelings were common in first-year dental students, and 86% of dental students reported that the mindfulness exercise proved to be an effective method for developing strategies to manage imposter-related feelings [14]. One possible explanation for the strong association between mindfulness and lower levels of IS could be mindfulness’s role in promoting self-awareness and emotional regulation. Medical students often experience high levels of stress, and mindfulness practices may provide them with tools to manage these emotions, thus reducing feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. Although self-esteem and anxiety were not directly measured in this study, the observed relationship between mindfulness and imposter syndrome aligns with existing research [28, 32–37], suggesting that mindfulness may support emotional regulation, reduce self-critical thoughts, and improve self-esteem—each of which are known to buffer against impostor feelings.

A scoping review on mindfulness-based interventions for medical students highlights the effectiveness of various programs in reducing perceived stress and enhancing well-being [38]. Most interventions are elective and incorporate mindfulness techniques such as meditation, yoga, biofeedback, and journaling [39, 40]. Across studies, medical students reported gains in mindfulness, empathy, self-compassion, and resilience, along with reductions in stress, anxiety, and burnout. For example, Wald et al. [41] evaluated a 2-hour workshop designed to enhance mind-body and reflective writing skills. Their results revealed increased student awareness of burnout and resilience, as well as the development of meditation and reflective writing as effective coping strategies. Mindfulness-based interventions and extracurricular activities can be incorporated into medical school curricula through various approaches. Workshops on mindfulness techniques, stress management, and resilience training can be offered as part of professional development or well-being programs. Mobile applications providing guided mindfulness exercises and self-reflection tools can help students engage in these practices independently. Increasing awareness of available resources, such as counseling services, peer support groups, and extracurricular clubs, can further encourage participation. Additionally, integrating structured extracurricular activities, such as sports, arts, or social initiatives, into the academic environment can promote well-being and professional identity formation. Future research should explore the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing stress and improving overall student well-being.

These findings align closely with our results, where we observed that students with higher mindfulness levels experienced lower IS. This connection suggests that while mindfulness fosters essential stress-coping skills and emotional resilience, it may best be leveraged as part of a broader, sustained support strategy to maximize long-term benefits in emotional and academic performance among medical students.

Our study also sought to examine whether participation in extracurricular activities, such as sports, social and artistic endeavors, might be associated with lower odds of having IS. In terms of extracurricular activities, Wang et al. postulated that frequent arts participation and cultural attendance are linked to lower mental distress and higher life satisfaction, with arts participation also enhancing mental health [42]. Research has indicated that engaging in the arts positively impacts mental health and overall well-being [43]. This may be attributed to various factors, such as the enhancement of self-identity through skill-building and creative self-expression, bolstering self-esteem and self-efficacy, and fostering a sense of social identity. Additionally, arts activities have been linked to reductions in psychological and physiological stress markers, cognitive stimulation, increased social support, decreased sedentary behaviors associated with depression, and improved coping skills [43–49]. In addition, Eaton et al. reported that engaging in sports-related physical activity enhances psychological well-being by alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression and promoting overall mental health. Unlike previous research that emphasized structured extracurricular activities as a means of reducing IS, our study suggests that even fewer formal activities such as sports or artistic pursuits, at least one hour per week, may be linked to similar psychological benefits. Additionally, engaging in informal extracurricular activities may offer a necessary break from academic pressure, allowing students to focus on personal growth and well-being, which in turn may alleviate IS.

While social media use was not significantly associated with IS in our multivariate analysis, prior literature has proposed potential mechanisms linking the two. Social comparison on curated platforms may intensify feelings of inadequacy, especially in highly competitive academic environments. Additionally, individuals experiencing higher levels of IS may use social media as a coping mechanism, reinforcing self-doubt and negative self-perceptions [50]. Although our findings did not support a direct association, these pathways merit further investigation.

The incorporation of mindfulness training into the curriculum may offer students a valuable tool for managing IS. Furthermore, encouraging students to engage in extracurricular activities especially those that promote creativity or physical health could help foster resilience and reduce feelings of inadequacy.

Future studies should build on these findings by incorporating more comprehensive psychological assessments. The use of validated instruments to measure constructs such as self-esteem, perfectionism, resilience, and anxiety would allow researchers to better understand the interplay between these variables and IS. Moreover, longitudinal designs could explore how these psychological traits develop over time in relation to mindfulness and academic experiences. Such work could inform targeted interventions that promote emotional resilience and reduce imposter feelings in medical students.

Strengths and limitations

Our study adds to the limited body of research examining the roles of mindfulness and extracurricular activities in relation to IS in medical students. Additionally, we used validated instruments for both mindfulness and IS. However, we also have several limitations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality between mindfulness, extracurricular activities, and IS. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported data may introduce self-reported bias, as students may underreport due to stigma or overreport their feelings of IS or mindfulness. A potential limitation of this study is selection bias, as participation was voluntary. It is possible that students with a stronger interest in mental health, mindfulness, or imposter syndrome were more inclined to participate, which may have affected the representativeness of the sample. Additionally, the response rate was 38.8%, which although comparable to other online surveys in medical education may reflect the influence of academic workload or timing. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Our study also lack the stratified random sampling approach which may limit the representativeness of our sample across key demographic groups, such as pre-clinical versus clinical students and male versus female participants. For future studies, implementing a stratified random sampling strategy to ensure proportional representation of these demographic groups could enhance the generalizability of findings, reduce sampling bias, and provide a more accurate understanding of how various factors influence the outcomes of interest. Additionally, improving response rates and exploring strategies such as providing incentives for participation and using multiple recruitment channels could help minimize nonresponse bias and enhance the validity of the study findings. Another limitation of our study is that we did not gather detailed information about the specific types and frequencies of extracurricular activities engaged in by the participants. As a result, we cannot analyze potential variations in impact among different types of activities. Another limitation of this study is the absence of qualitative data, which could provide deeper insights into the experiences and perspectives of participants regarding imposter syndrome. Incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, in future research could enrich our understanding of the underlying factors contributing to imposter syndrome and enhance the interpretation of quantitative findings.

A notable limitation of our study is the restricted psychological scope, as we did not include other potentially influential constructs such as self-esteem, resilience, anxiety, or perfectionism, which have been linked to imposter syndrome in previous literature. As such, our findings should be interpreted within this focused framework. Future research would benefit from incorporating a broader range of psychological constructs, such as self-esteem, resilience, anxiety, and perfectionism, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to imposter syndrome in medical students.

Finally, the sample is limited to a single institution, which prevents the generalizability of the findings to other medical schools in Türkiye or globally.

Conclusion

The findings of our study indicate that higher levels of mindfulness and participation in extracurricular activities are associated with lower IS scores, suggesting a potential protective effect. These results underscore the value of incorporating mindfulness-based interventions and encouraging extracurricular engagement to support medical students’ well-being. Medical schools may consider integrating structured mindfulness programs and promoting extracurricular opportunities as strategies to help mitigate IS.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the medical students who participated in this study for their valuable time.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology: OT, PA and SH; Formal Analysis: EG, KA and PA; Investigation, Resources, and Data Curation: SH, EG, KA, HBA and ASK; Writing-Original Draft Preparation: OT and PA ; Writing-Review and Editing: OT and PA. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding to declare.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Although the data are not publicly accessible due to privacy and ethical concerns, a substantial portion of the analyzed data is included in the manuscript. Further information can be made available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Marmara University School of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Protocol Code: 09.2023.1400, Date: 03.11.2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clance PR, Imes SA. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory Res Pract. 1978;15(3):241–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld A, Babenko O, Lai H, Svrcek C, Malin G. Why do we feel like intellectual frauds?? A Self-Determination theory perspective on the impostor phenomenon in medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2023;35(2):180–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer ML, van Kessel G, Sanderson B, Naumann F, Lane M, Reubenson A, Carter A. Resilience in higher education students: a scoping review. High Educ Res Dev. 2019;38(6):1105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levant B, Villwock JA, Manzardo AM. Impostorism in American medical students during early clinical training: gender differences and intercorrelating factors. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:90–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naser MJ, Hasan NE, Zainaldeen MH, Zaidi A, Mohamed Y, Fredericks S. Impostor phenomenon and its relationship to Self-Esteem among students at an international medical college in the middle east: A cross sectional study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:850434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leach PK, Nygaard RM, Chipman JG, Brunsvold ME, Marek AP. Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clance PR, OToole MA. The imposter phenomenon: an internal barrier to empowerment and achievement. Women Therapy. 1987;6:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bravata DM, Watts SA, Keefer AL, Madhusudhan DK, Taylor KT, Clark DM, Nelson RS, Cokley KO, Hagg HK. Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1252–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legassie J, Zibrowski EM, Goldszmidt MA. Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1090–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:364–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erogul M, Singer G, McIntyre T, Stefanov DG. Abridged mindfulness intervention to support wellness in first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):350–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Özdemir G. Feelings of fraud among women in turkey: prevalence and demographic risk factors of the impostor phenomenon. J Clin Psychol Res. 2024;8(1):55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastan CD, Mc Donough AL, Finkelman M, Daniels JC. Evaluation of mindfulness practice in mitigating impostor feelings in dental students. J Dent Educ. 2022;86(11):1513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristoffersson E, Boman J, Bitar A. Impostor phenomenon and its association with resilience in medical education - a questionnaire study among Swedish medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39(6):594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, And other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. And Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picton A, Greenfield S, Parry J. Why do students struggle in their first year of medical school? A qualitative study of student voices. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanriover O, Peker S, Hidiroglu S, Kitapcioglu D, Inanici SY, Karamustafalioglu N, Gulpinar MA. The emotions experienced by family medicine residents and interns during their clinical trainings: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2023;24:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan M. Imposter syndrome-a particular problem for medical students. BMJ. 2021;375:n3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neureiter M, Traut-Mattausch E. An inner barrier to career development: preconditions of the impostor phenomenon and consequences for career development. Front Psychol. 2016;7:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Şahin EE, Uslu GF. Clance impostor phenomenon scale (CIPS): adaptation and validation in Turkish university students. Psycho-Educational Res Reviews (PERR). 2022;11(1):270-82.

- 24.Ikbaal M, Musa N. Prevalence of impostor phenomenon among medical students in a Malaysian private medical school. Int J Med Students. 2018;6:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oriel K, Plane MB, Mundt M. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam Med. 2004;36(4):248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Özyeşil Z, Arslan C, Kesici Ş, Deniz ME. Bilinçli Farkındalık Ölçeği’ni Türkçeye Uyarlama Çalışması. Eğitim ve Bilim. 2011;36(160):224-35.

- 28.Sonnak C, Towell T. The impostor phenomenon in British university students: relationships between self-esteem, mental health, parental rearing style and socioeconomic status. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;31(6):863–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shill-Russell C, Russell RC, Daines B, Clement G, Carlson J, Zapata I, Henderson M. Imposter syndrome relation to gender across osteopathic medical schools. Med Sci Educ. 2022;32(1):157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wrench A, Padilla M, O’Malley C, Levy A. Impostor phenomenon: prevalence among 1st year medical students and strategies for mitigation. Heliyon. 2024;10(8):e29478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price PC, Holcomb B, Payne MB. Gender differences in impostor phenomenon: A meta-analytic review. Curr Res Behav Sci. 2024;7:100155. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guendelman S, Medeiros S, Rampes H. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Front Psychol. 2017;8:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutz J, Bruhl AB, Doerig N, Scheerer H, Achermann R, Weibel A, Jancke L, Herwig U. Altered processing of self-related emotional stimuli in mindfulness meditators. NeuroImage. 2016;124(Pt A):958–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iani L, Lauriola M, Chiesa A, Cafaro V. Associations between mindfulness and emotion regulation: the key role of describing and nonreactivity. Mindfulness. 2019;10(2):366–75. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newar R, Gupta RK, Krishnan RG, Shekhawat K, Walia Y. Self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between imposter phenomenon and academic performance among college students. Int J Adolescence Youth. 2025;30(1):2496449. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhardwaj D, Kumar R, Bahurupi Y. Influence of perceived impostorism on self-esteem and anxiety among university nursing students: recommendations to implement mentorship program. J Family Med Prim Care. 2024;13(12):5745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pákozdy C, Askew J, Dyer J, Gately P, Martin L, Mavor KI, Brown GR. The imposter phenomenon and its relationship with self-efficacy, perfectionism and happiness in university students. Curr Psychology: J Diverse Perspect Diverse Psychol Issues. 2024;43(6):5153–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohmand S, Monteiro S, Solomonian L. How are medical institutions supporting the Well-being of undergraduate students?? A scoping review. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2133986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bond AR, Mason HF, Lemaster CM, Shaw SE, Mullin CS, Holick EA, Saper RB. Embodied health: the effects of a mind-body course for medical students. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams MK, Estores IM, Merlo LJ. Promoting resilience in medicine: the effects of a Mind-Body medicine elective to improve medical student Well-being. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020;9:2164956120927367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wald HS, Haramati A, Bachner YG, Urkin J. Promoting resiliency for interprofessional faculty and senior medical students: outcomes of a workshop using mind-body medicine and interactive reflective writing. Med Teach. 2016;38(5):525–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S, Mak HW, Fancourt D. Arts, mental distress, mental health functioning & life satisfaction: fixed-effects analyses of a nationally-representative panel study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtis A, Gibson L, O’Brien M, Roe B. Systematic review of the impact of arts for health activities on health, wellbeing and quality of life of older people living in care homes. Dement (London). 2018;17(6):645–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gold C, Voracek M, Wigram T. Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: a meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):1054–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarobe L, Bungay H. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(6):337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fancourt D, Finn S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutchinson S, Loy D, Kleiber D, Dattilo J. Leisure as a coping resource: variations in coping with traumatic injury and illness. Leisure Sci - LEISURE SCI. 2003;25:143–61. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perkins A, Ridler J, Browes D, Peryer G, Notley C, Hackmann C. Experiencing mental health diagnosis: a systematic review of service user, clinician, and carer perspectives across clinical settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):747–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perkins R, Ascenso S, Atkins L, Fancourt D, Williamon A. Making music for mental health: how group drumming mediates recovery. Psychol Well-Being. 2016;6(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faizan Siddiqui M, Azaroual M. Combatting burnout culture and imposter syndrome in medical students and healthcare professionals: A future perspective. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2024;11:23821205241285601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Although the data are not publicly accessible due to privacy and ethical concerns, a substantial portion of the analyzed data is included in the manuscript. Further information can be made available upon reasonable request.