Abstract

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is an autoimmune disorder that leads to acute flaccid paralysis and often results in long-term sequelae such as muscle weakness and sensory dysfunction. While recovery is possible, current rehabilitation strategies for muscle function and nerve regeneration often show limited effectiveness and require prolonged treatment. Psychological and behavioral therapy has shown promise in enhancing recovery by improving patient compliance and emotional stability. However, its impact on muscle function recovery in GBS patients remains poorly studied. This research aims to explore the role of psychological and behavioral therapy in improving muscle function and neurological recovery in GBS survivors. Patients diagnosed with classic or variant forms of GBS at the General Hospital of the Western Theater Command from January 2014 to January 2022 were included in this study. Based on the treatment measures received, the patients were divided into two groups: the treatment group received psychological and behavioral therapy in addition to conventional neuromuscular rehabilitation, while the control group received only conventional neuromuscular rehabilitation. The primary outcome measure was the Barthel Index for activities of daily living, and secondary measures included disability scores and sensory function scores. PSM was used to balance baseline characteristics between the two groups, and statistical analyses were performed to assess differences in therapeutic efficacy. After 1:1 Propensity Score Matching (PSM), 277 matched pairs were obtained. There were no significant differences in age, hypertension, diabetes, alcohol consumption, disability scores, sensory function scores, or Barthel Index scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). Comparison of functional assessments at discharge and 6 months after discharge. The results indicate that both the PI-Group and the NI-Group had significant recovery in functional scores (P < 0.05). In different subgroups, the results show that the more severe the condition, the higher the degree of benefit after psychobehavioral therapy (P < 0.05). The analysis suggests that the more severe the condition, the larger the SMD difference. Psychological and behavioral therapy significantly enhances daily functional independence and neuromuscular function recovery in patients with GBS sequelae. It can serve as an effective supplement to conventional rehabilitation. This therapy potentially improves patients’ adherence to rehabilitation, alleviates anxiety, and motivates active participation in training, thereby accelerating the recovery of daily living and neuromuscular functions. Further studies are needed to explore its mechanisms and long-term efficacy to provide stronger scientific evidence for GBS rehabilitation.

Keywords: Guillain-Barré Syndrome, Psychological and behavioral therapy, Neuromuscular rehabilitation, Propensity score matching

Subject terms: Health care, Neurology

Introduction

Guillain-Barré Syndrome is an autoimmune neurological disorder characterized primarily by acute flaccid paralysis, affecting the peripheral nervous system1,2. It often leads to severe neurological impairments and varying degrees of disability2,3. According to global epidemiological data, the incidence of GBS is approximately 1–2 cases per 100,000 people annually, with a rising trend in recent years3,4. Although GBS is a self-limiting disease in most cases, it still has a fatality rate of up to 5%, and due to inadequate treatment or unprofessional and unsustained rehabilitation process in most patients, a large number of patients who have passed the acute stage still have functional sequelae such as limb weakness and sensory disorders4–6. With changes in modern lifestyles, increased environmental pollution, rapid industrialization, and the spread of viral infections such as COVID-19, the prevalence of autoimmune diseases caused by immune system imbalance has significantly increased5,6. As a result, GBS has become a major focus in neurology.

GBS sequelae often manifest as varying degrees of motor dysfunction, sensory loss, or abnormalities, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life6,7. Therefore, the key to the treatment of these GBS sequelae lies in how to promote the regeneration and recovery of neuromuscular function more efficiently and effectively, and improve the life and social function of patients7,8. However, current rehabilitation strategies, particularly those targeting nerve regeneration and muscle function recovery, often require prolonged treatment and yield limited results. Accelerating recovery and improving patients’ ability to live independently have become critical research priorities in neurology and rehabilitation medicine.

In recent years, psychobehavioral therapy has demonstrated significant adjuvant efficacy in the rehabilitation of many major diseases. Common forms include lifestyle interventions, psychological interventions, risk factor management, and prompting patients to form long-term habits8,9. Especially in the rehabilitation of neuromuscular related diseases, psycho-behavioral therapy and intervention can potentially increase patient compliance and emotional stability, which is conducive to promoting long-term rehabilitation10.However, research on the impact of psychological and behavioral therapy on neurological recovery in GBS patients remains limited10,11. Therefore, exploring the role of psychological and behavioral interventions in GBS sequelae rehabilitation holds promising clinical value.

This study employs a retrospective cohort design and utilizes Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to reduce confounding factors, providing a comprehensive analysis of the effects of psychological and behavioral therapy on the neurological recovery of GBS patients with sequelae. This study aims to explore the potential relationship between psychobehavioral therapy and improved neurological function recovery in patients with Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS), thereby providing reference evidence for the formulation of potential rehabilitation strategies and adjustment of treatment protocols.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed with classic or variant GBS at the General Hospital of the Western Theater Command between January 2014 and January 2022. All patients had confirmed diagnoses of GBS upon admission and exhibited varying degrees of motor or sensory dysfunction at discharge. Patients who received psychological and behavioral therapy during follow-up were assigned to the treatment group, while those who did not receive such therapy were assigned to the control group.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosed with GBS according to the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (2023). (2) Disability score ≥ 1 at discharge. (3) Followed up at the study center for at least six months post-rehabilitation.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with minimal or no neurological sequelae at dis-charge, demonstrating near-normal functional independence. (2) Patients with recur-rent GBS requiring rehospitalization, unclear diagnoses, or suspected chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). (3) Patients with other neurological disorders, stroke, or comorbidities such as cerebrovascular events leading to motor or sensory deficits, or autoimmune diseases. (4) Patients with significant missing clinical data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

This study has obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee of The General Hospital of Western Theater Command. As the study uses anonymized clinical data and does not involve patient intervention, the Ethics Committee waived the requirement for individual informed consent. All methods comply with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical guidelines.

Treatment methods

Psychological Intervention Group (PI-Group): In addition to standard neuromuscular rehabilitation (medications and physical therapy), the treatment group received psychological and behavioral therapy, including: (1) Lifestyle interventions: Weekly follow-ups via phone or messaging to encourage adequate sleep, a low-salt diet, and other healthy habits. (2) Psychological interventions: Regular mental health assessments using anxiety scales, with reminders for patients and families to seek psycho-logical support or attend mental health clinics as needed. Anxiety and depression were addressed through counseling or anti-anxiety medications. (3) High-risk factor management: Regular follow-ups by assigned nurses to record smoking and drinking habits and encourage regular exercise, smoking cessation, and alcohol avoidance. (4) Rehabilitation adherence: Promoting long-term, effective rehabilitation routines.

Non-Intervention Group (NI-Group): Patients in the control group received standard neuromuscular rehabilitation (medications and physical therapy) and follow-up care as instructed. Clinical data and outcomes were recorded during follow-up visits six months post-rehabilitation.

Outcome measures

Clinical data collected for both groups included age, sex, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes), lifestyle habits (smoking, alcohol consumption),disability scores (measured by the Modified Rankin Scale, a 7-point scale), sensory function scores (assessed via the Fugl-Meyer Assessment, FMA), and Barthel Index scores. These scales are used to assess the functional outcomes of neuromuscular recovery, with a focus on changes in patients’ daily living independence during follow-up12,13.

Primary outcome Independence in daily living, assessed using the Barthel Index.

Secondary outcomes Disability scores and sensory function scores.

All outcome assessments for both groups were conducted uniformly at 6 months post-discharge. All evaluations were performed by trained researchers who had received standardized training on the application criteria of the scales.

Bias control

To minimize bias during data collection and analysis:

Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the appropriate selection of study subjects.

Completeness and objectivity of clinical data and quantifiable outcome measures were ensured.

Disputed clinical data were reviewed and adjudicated by at least two re-searchers.

Exclusion of Unmatched Patients: After performing 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM), patients were defined as “unmatched” if no counterpart in the control group had a propensity score within the caliper threshold. Unmatched patients were excluded from the final analysis to maintain baseline comparability between groups and reduce confounding risks caused by individuals without valid matches.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0. Normally distributed continuous variables (e.g., age, Barthel Index scores) were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using t-tests. Non-normally distributed or skewed continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) [M (P25, P75)] and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables (e.g., sex, smoking, drinking, hypertension, diabetes) were expressed as frequency (percentage) and com-pared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression was used to calculate propensity scores. 1:1 matching was performed between the two groups of patients according to PSM, and the caliper value was set to 0.05 (the allowable error in probability during matching). A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

From 2014 to 2022, a total of 912 patients were included in the study. All patients were diagnosed with either classic or variant GBS and exhibited varying degrees of motor or sensory dysfunction at discharge. Among them, 456 patients in the psycho-logical treatment group received at least one psychological or behavioral therapy after discharge, while the 456 patients in the control group received only routine rehabilitation and neurotrophic therapies.

In the psychological treatment group, there were 282 males (61.8%) with a mean age of 51.61 ± 8.53 years. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, and a history of alcohol consumption numbered 156 (34.2%), 135 (29.6%), and 81 (17.8%), respectively. In the control group, there were 246 males (53.9%) with a mean age of 60.41 ± 10.60 years. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, and a history of alcohol consumption numbered 126 (27.6%), 102 (22.4%), and 51 (11.2%), respectively. The baseline demographic and clinical features showed significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.05).

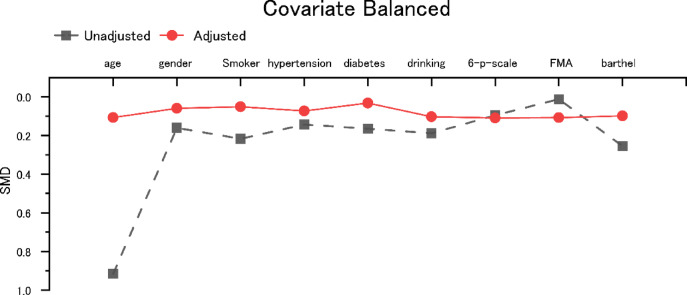

After 1:1 Propensity Score Matching (PSM), 277 matched pairs were obtained. There were no significant differences in age, hypertension, diabetes, alcohol consumption, disability scores, sensory function scores, or Barthel Index scores between the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating that baseline demographic and clinical variables were well-balanced (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Clinical features before and after PSM.

| Features | All patients | Propensity-matched patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI-Group (n = 456) | NI-Group (n = 456) | P | PI-Group (n = 277) | NI-Group (n = 277) | P | |

| Age | 51.61 ± 8.529 | 60.41 ± 10.596 | < 0.001 | 55.08 ± 7.815 | 56 ± 9.305 | 0.125 |

| Gender | 282 (61.8%) | 246 (53.9%) | 0.016 | 173 (62.5%) | 165 (59.6%) | 0.536 |

| Smoker | 210 (46.1%) | 162 (35.5%) | 0.002 | 108 (39%) | 115 (41.5%) | 0.621 |

| Hypertension | 156 (34.2%) | 126 (27.6%) | 0.032 | 85 (30.7%) | 74 (27.4%) | 0.439 |

| Diabetes | 135 (29.6%) | 102 (22.4%) | 0.013 | 70 (25.3%) | 74 (26.7%) | 0.773 |

| Drinking | 81 (17.8%) | 51 (11.2%) | 0.005 | 28 (10.1%) | 37 (13.4%) | 0.314 |

| 6-p-scale | 1.74 ± 0.816 | 1.82 ± 0.852 | 0.153 | 1.78 ± 0.849 | 1.69 ± 0.797 | 0.176 |

| FMA | 3.48 ± 0.874 | 3.49 ± 0.836 | 0.816 | 3.49 ± 0.919 | 3.58 ± 0.751 | 0.238 |

| Barthel | 78.72 ± 11.562 | 75.63 ± 12.662 | < 0.001 | 77.29 ± 11.479 | 78.48 ± 12.692 | 0.233 |

Fig. 2.

Standardized mean difference of variables before and after PSM. PSM, propensity score matching; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Intragroup differences in disability, sensory, and Barthel scores

Comparisons of disability scores, sensory function scores, and Barthel Index scores between the psychological treatment group and the control group at discharge and six months post-discharge revealed significant differences (P < 0.05; Table 2; Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of functional assessment at discharge and 6-months after discharge.

| Variables | PI-Group (n = 277) | P | NI-Group (n = 277) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D/C | After 6 mo | D/C | After 6 mo | |||

| 6-p-scale | 1.78 ± 0.849 | 1.12 ± 0.99 | < 0.001 | 1.69 ± 0.797 | 1.00 ± 0.893 | < 0.001 |

| FMA | 3.49 ± 0.919 | 4.20 ± 0.91 | < 0.001 | 3.58 ± 0.751 | 4.37 ± 0.822 | < 0.001 |

| barthel | 77.29 ± 11.479 | 87.45 ± 10.069 | < 0.001 | 78.48 ± 12.692 | 85.25 ± 11.846 | < 0.001 |

Fig. 3.

Comparison of functional assessments at discharge and 6 months after discharge. The results indicate that both the PI-Group and the NI-Group had significant recovery in functional scores.

Comparative functional outcomes between groups post-PSM

At discharge, comparisons of disability scores, sensory function scores, and Barthel Index scores between the two groups showed no statistically significant differences after PSM (P > 0.05). However, at six months post-discharge, the differences in sensory function scores and Barthel Index scores between the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.05 Table 3).

Table 3.

Functional assessment differences at six months post-discharge.

| Variables | D/C | P | After 6 months | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI-Group (n = 277) | NI-Group (n = 277) | PI-Group (n = 277) | NI-Group (n = 277) | |||

| 6-p-scale | 1.78 ± 0.849 | 1.69 ± 0.797 | 0.176 | 1.12 ± 0.99 | 1 ± 0.893 | 0.144 |

| FMA | 3.49 ± 0.919 | 3.58 ± 0.751 | 0.238 | 4.2 ± 0.91 | 4.37 ± 0.822 | 0.022 |

| barthel | 77.29 ± 11.479 | 78.48 ± 12.692 | 0.233 | 87.45 ± 10.069 | 85.25 ± 11.846 | 0.015 |

Stratified analysis of functional recovery by severity

After further 1:1 PSM, patients were divided into three groups—mild, moderate, and severe—based on their disability scores and sensory function scores at discharge. Comparisons were made between the psychological treatment group and the control group within each severity category.

At discharge, no statistically significant differences were found in Barthel Index scores among the groups (P > 0.05). However, at six months post-discharge, the differences in Barthel Index scores between the two groups were statistically significant across all severity levels (P < 0.05). A deeper analysis revealed that the greater the se-verity of residual symptoms at discharge, the larger the improvement in Barthel Index scores observed in patients who underwent psychological and behavioral therapy (Table 4; Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of functional assessments across severity groups.

| Variables | Mild | Mo | Severe | P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI-Group (n = 130) | NI-Group (n = 130) | P | PI-Group (n = 129) | NI-Group (n = 129) | P | PI-Group (n = 33) | NI-Group (n = 33) | |||

| Barthel | D/C | 88.96 ± 5.896 | 88.46 ± 7.149 | 0.516 | 72.75 ± 4.049 | 73.06 ± 3.144 | 0.467 | 57.79 ± 5.005 | 55.39 ± 7.475 | 0.117 |

| After 6 mo | 97.38 ± 3.534 | 94.73 ± 5.331 | 0.001 | 83.33 ± 3.662 | 80.01 ± 3.802 | 0.001 | 69.45 ± 5.056 | 61.97 ± 8.655 | 0.001 | |

Fig. 4.

Comparison of functional assessments across severity groups. (a) In different subgroups, the results show that the more severe the condition, the higher the degree of benefit after psychobehavioral therapy. (b) The analysis suggests that the more severe the condition, the larger the SMD difference.

Discussion

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of GBS patients with residual symptoms who received psychological and behavioral treatment, exploring its effect on neurofunctional recovery. The results showed that the treatment group, when combined with psychobehavioral therapy, showed better recovery on relevant scale scores, namely life and social functioning, than the control group. These findings provide a new intervention method for comprehensive rehabilitation of GBS residual symptoms and further confirm the potential value of psychological and behavioral intervention in the recovery of neuromuscular damage.

In terms of daily living function, patients who received psychological and behavioral treatment showed significant improvement in the Barthel Index of Independence11,14,15. This result may be closely related to the role of psychological and behavioral therapy in improving emotional states and enhancing positive psychological expectations14–16. Recently published studies have shown that the enthusiasm of psychological factors is far more than people think, and it has a great role in promoting the rehabilitation of nerve and muscle diseases, which can help the damaged nerve plasticity regeneration faster and better, and accelerate the repair process16,17. Moreover, psychological and behavioral interventions have been proven to alleviate anxiety and depressive symptoms, thereby motivating patients to actively participate in rehabilitation training on their own initiative. As emphasized in a consensus statement encompassing 50 years of psychological research on sports injuries18, this improvement in compliance with rehabilitation protocols has significantly promoted the process of daily functional recovery.

Regarding improvements in neurological function, this study found that patients in the psychological treatment group also showed improvements in sensory and motor function scores. Although recovery from nervous system damage usually takes a long time, psychological and behavioral therapy may indirectly promote neurological recovery through various mechanisms17,19. On the one hand, psychological intervention can reduce the pain expectation of patients, so that patients can better accept pain and discomfort, so as to better cooperate with relevant rehabilitation actions and treatment20. On the other hand, psychological and behavioral therapy may alleviate neuroinflammation or reduce chronic pain, indirectly reducing the stress load on the nervous system and thus promoting neurological repair.

The strength of this study lies in the use of propensity score matching (PSM) to minimize the impact of confounding factors such as age, gender, and underlying dis-eases, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the impact of psychological and behavioral therapy on GBS residual symptoms. Through strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, we ensured the reliability of the data and minimized bias. However, this study does have some limitations. Due to the data characteristics of retrospective studies, it is inevitable that the data information of past cases will be partially biased. Future re-search could extend the follow-up period to further verify the effectiveness of psycho-logical and behavioral therapy at different stages of recovery. Similarly, this study did not perform subtype statistics for GBS variants. As different variants (such as Miller-Fisher syndrome, Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, etc.) have distinct pathological mechanisms and prognoses, the evaluation of intervention effects may also vary. Therefore, in future research, we need to incorporate variant analysis to further refine the impact of psycho-behavioral therapy on different GBS variants.

It is also worth noting that the mechanisms of psychological and behavioral therapy in GBS residual symptom patients still need further exploration20,21. Recent evidence suggests that the repair of the nervous system is not solely dependent on medication but is also influenced by psychological and environmental factors7,22. Psychological and behavioral therapy may support nerve repair by regulating the excitability of the central nervous system and enhancing the brain’s cortical regulation of neurological recovery. In the future, relevant studies can be combined with imaging and special markers for in-depth analysis, to explore the deeper biological mechanism of psychological and behavioral intervention in molecular science. Additionally, different psychological intervention methods (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditation therapy, etc.) may have varying effects on neurological rehabilitation1,4,23. Identifying the best psychological intervention approach for GBS patients will also be a focus of future research.

Conclusion

This study, through retrospective analysis, suggests a potential positive role of psychological and behavioral therapy in neurorehabilitation for GBS residual symptoms. Finally, despite our efforts to explore the correlations, there remains a possibility that some potential confounding factors were not included in our analysis. Regarding the true impact of psychobehavioral therapy on neurorehabilitation for GBS sequelae, more samples and related studies are still needed to further explore the underlying mechanisms.

Abbreviations

- GBS

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- FMA

Fugl-Meyer assessment

- D/C

Discharge

Author contributions

Zhijie Lu and Xin Xie wrote the main part of the manuscript. LZ, XY and ZR participated in data collection and wrote some content. FJ and MW designed the article’s ideas and reviewed the article. All authors read and approved the final submission.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhijie Lu and Xin Xie have equally contributed to this work.

Contributor Information

Jin Fan, Email: fanjin821029@163.com.

Mingyu Wang, Email: wmy20241212@163.com.

References

- 1.Tikhomirova, A. et al. Campylobacter jejuni virulence factors: update on emerging issues and trends. J. Biomed. Sci.31, 45. 10.1186/s12929-024-01033-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkes, M. A. & Wijdicks, E. F. M. Improving outcome in severe myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Semin. Neurol.44, 263–270. 10.1055/s-0044-1785509 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grelowska, M., Logoń, K. & Dziadkowiak, E. Prognostic factors associated with worse outcomes in patients with GBS: A systematic review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med.10.17219/acem/186949 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estublier, B. et al. Long-term outcomes of paediatric Guillain-Barré syndrome. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol.66, 176–186. 10.1111/dmcn.15693 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baizabal-Carvallo, J. F., Cortés, C. M., Alonso-Juarez, M. & Fekete, R. Tremor following Guillain Barré Syndrome. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet. Mov. (N Y)14, 53. 10.5334/tohm.906 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acero-Garces, D. et al. Long-term outcomes of patients affected by Guillain-Barré syndrome in Colombia after the Zika virus epidemic. J. Neurol. Sci.463, 123140. 10.1016/j.jns.2024.123140 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uz, F. B., Uz, C. & Karaahmet, O. Z. Three-year follow-up outcomes of adult patients with Guillain-Barré Syndrome after rehabilitation. Malawi Med. J.35, 156–162. 10.4314/mmj.v35i3.4 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahan, I. et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in Guillain-Barré syndrome: A prognostic biomarker of severe disease and mechanical ventilation in Bangladesh. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst.28, 47–57. 10.1111/jns.12531 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Güzin, Y. et al. Retrospective evaluation of Guillain-Barre syndrome in children: A single-center experience. Pediatr. Int.65, e15650. 10.1111/ped.15650 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devi, A. K. et al. Long-term neurological, behavioral, functional, quality of life, and school performance outcomes in children with Guillain-Barré Syndrome admitted to PICU. Pediatr. Neurol.140, 18–24. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.11.002 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breville, G., Sukockiene, E., Vargas, M. I. & Lascano, A. M. Emerging biomarkers to predict clinical outcomes in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Expert Rev. Neurother.23, 1201–1215. 10.1080/14737175.2023.2273386 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Swieten, J. C., Koudstaal, P. J., Visser, M. C., Schouten, H. J. & van Gijn, J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke19, 604–607. 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahoney, F. I. & Barthel, D. W. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md. State Med. J.14, 61–65 (1965). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugumar, K., Chidambaram, A. C. & Gunasekaran, D. Assessment of neurological sequelae and new-onset symptoms in the long-term follow-up of paediatric Guillain-Barre syndrome: A longitudinal study from India. J. Paediatr. Child. Health58, 2211–2217. 10.1111/jpc.16185 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levison, L. S., Thomsen, R. W. & Andersen, H. Increased mortality following Guillain-Barré syndrome: A population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol.29, 1145–1154. 10.1111/ene.15204 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duong, C. H., Mueller, J. E., Tubert-Bitter, P. & Escolano, S. Estimation of mid-and long-term benefits and hypothetical risk of Guillain-Barre syndrome after human papillomavirus vaccination among boys in France: A simulation study. Vaccine40, 359–363. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.046 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulli, S. et al. The efficacy of rehabilitation in people with Guillain-Barrè syndrome: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Neurother.21, 455–461. 10.1080/14737175.2021.1890034 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tranaeus, U. et al. 50 years of research on the psychology of sport injury: A consensus statement. Sports Med.54, 1733–1748. 10.1007/s40279-024-02045-w (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sriwastava, S. et al. Guillain Barré Syndrome and its variants as a manifestation of COVID-19: A systematic review of case reports and case series. J. Neurol. Sci.420, 117263. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117263 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwan, J. & Biliciler, S. Guillain-Barré Syndrome and other acute polyneuropathies. Clin. Geriatr. Med.37, 313–326. 10.1016/j.cger.2021.01.005 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng, M. C. F. et al. Prolonged ventilatory support for patients recovering from Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Neurol. Clin. Pract.11, 18–24. 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000793 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shang, P. et al. Mechanical ventilation in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol.16, 1053–1064. 10.1080/1744666x.2021.1840355 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillyar, C. & Nibber, A. Psychiatric sequelae of Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Towards a multidisciplinary team approach. Cureus12, e7051. 10.7759/cureus.7051 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.