Abstract

Background

The stigmatisation of mental illness is affected by culture, beliefs, and empathy; however, researchers rarely take these factors into consideration when developing interventions to reduce stigma. Nursing professionals represent the largest group of healthcare workers globally and are responsible for the care and recovery of individuals with schizophrenia. However, people with schizophrenia face serious stigmatisation. Studies findings show that nursing students express unfavourable attitudes towards people with schizophrenia, indeed more severely than medical students express such attitudes. As nursing students are future healthcare providers for individuals with schizophrenia, addressing their existing stigmas is essential for providing high-quality care for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

The study was a single-center, two-arm, parallel, open-label, pilot randomized controlled trial conducted in a hospital without a psychiatry department. The study intervention was implemented online from February 20, 2023 to June 20, 2023. Sixty fourth-year nursing students were included according to this study’s inclusion criteria through convenience sampling and randomised into the experimental and control groups equally. The intervention training program was developed through a systematic review, focus group interviews with nursing students, expert panel, and consultation with nursing students. The experimental group received a 4-week intervention training program, whereas the control group received instructions to read a book. The feasibility and acceptability were assessed. The efficacy of the intervention was evaluated by the Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test (KAST), the Mental Illness Clinicians’ Attitudes Scale (MICA), the Reported and Intended Behavior Scale (RIBS), and the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) at baseline (T1), post-intervention (T2), and 3-month follow-up (T3). The analyses included paired T-tests, chi-square tests for nominal variables, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and generalized estimating equations (GEE).

Results

The recruitment, retention, and intervention attendance rates indicate that the intervention was both feasible and acceptable. The experimental group showed significant improvements in KAST scores (knowledge of schizophrenia) at T2 and T3, along with notable improvements in the RIBS score (intended behaviour) at T2 and a significant decrease in the MICA score (negative attitudes) at T2 and T3. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in JSE-NSR score (empathy) at T3. The control group displayed no significant changes in the MICA, RIBS or JSE-NSR scores at T2 and T3. GEE test showed that the experimental group had a more significant decrease in MICA scores at T2 and T3, a substantial enhancement in JSE score at T3 and a more significant decrease in RIBS at T2 compared to the control group.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that the Chinese culture-specific online intervention was both feasible and well-received among fourth-year nursing students for reducing schizophrenia stigma.

Trial registration

The study was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT05413408) on 10 June 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05413408?term=MICA&rank=10.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03743-0.

Keywords: Social stigma, Schizophrenia, Randomized controlled clinical trial, Culture, Nursing students

Introduction

Schizophrenia is the most stigmatised mental illness [1] and is commonly perceived by the general public to be associated with a higher level of danger and unpredictability compared to other mental illnesses [2]. Globally, an estimated 24 million people, which accounts for 1 in 300 individuals or 0.32% of the world’s population, are affected by schizophrenia [3]. In China, approximately 7.8 million people have been diagnosed with schizophrenia, and 100,000 new diagnoses are reported each year [4]. A study conducted in China involving 204 participants investigated people’s attitudes towards individuals with various mental illnesses and found that those with schizophrenia were the most stigmatized [5].

Individuals with schizophrenia face stigmatization in various aspects of their daily lives, including employment settings [6], friendships keeping [7], establishing romantic relationships [6], engaging in rehabilitation [8], striving for social integration [8], and seeking or receiving medical treatment [9]. This stigmatization can have a negative impact on the quality of life of individuals with schizophrenia [1], reduce their willingness to confide in others or seek help [10], and lead to the disregard of their symptoms and loss of self-esteem [10]. Family caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia also face stigma associated with the illness [11], resulting in elevated emotional distress and negative responses from others [12]. Moreover, stigma can affect mental health professionals working in psychiatric departments [13], leading to a shortage of doctors and nurses [14].

Nursing professionals represent the largest group of healthcare workers globally [15] and are responsible for the care and recovery of people diagnosed with schizophrenia [16]. A study that included 8254 nurses indicated that nurses hold negative attitudes towards individuals with mental illness or act as ‘stigmatizers’ of such individuals [17]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the attitudes of nursing students towards schizophrenia, as they may need to care for individuals with schizophrenia in the future. A cross-sectional study of 502 medical students and 500 nursing students in Singapore in 2016 found that nursing students exhibited more negative attitudes towards individuals with schizophrenia compared to medical students [18]. Similarly, nursing students in mainland China hold negative attitudes towards individuals with mental illness [19]. Moreover, nursing students in China have lower levels of knowledge regarding schizophrenia compared to their counterparts in the USA [20]. It is recognized that interventions delivered to nursing students are likely to result in improved patient care in the future [21]. Thus, changing the attitudes of nursing students towards schizophrenia may decrease their stigmatization of individuals with schizophrenia, and these improved attitudes may persist throughout their nursing careers.

China has a culture rooted in face-saving and Confucianism [22]. Stigmatizing attitudes are significantly influenced by socio-cultural and religious factors [23, 24]. In China, some people believe that schizophrenia is caused by the faults or immoral behaviour of one’s ancestors, and that individuals with the condition behaved immorally in their past lives [25]. Many people also believe that schizophrenia is caused by black magic or possession by evil spirits (gods or demons) [26]. Empathy plays a crucial role in building rapport and trust between individuals, and it is important in various social contexts, including healthcare [27]. Improving people’s empathy towards stigmatized groups, such as those with schizophrenia, can also enhance their empathy towards individuals with other mental illnesses [28]. However, this factor is most often neglected in studies designed to decrease schizophrenia stigma. Moreover, stigma has unique cultural aspect across different racial and ethnic minority groups [29]. Thus, trials conducted outside China are unlikely to be directly generalisable to China due to the cultural issues.

Two common methods that have been found effective for reducing mental illness stigma in particular are education and contact with individuals who have a mental illness or schizophrenia [30]. Many studies have not included a control group and have collected data only immediately after interventions, making it difficult to determine the extent to which the reported benefits are attributable to the intervention and whether they have been sustained over time [31–33]. In addition, while these studies have reported significant differences between pre- and post-scores, the effect sizes are unclear [31–33].

Furthermore, most studies focused on reducing stigma related to mental disorders, often using the term ‘mental illness’ broadly to cover various conditions like depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder [34–36]. However, schizophrenia stands out as highly stigmatized, requiring unique interventions to reduce associated stigma, distinct from those for other disorders. Previous studies lack methodological rigor, with issues like unclear randomization procedures [37], small sample size [38] incomplete outcome data reporting [38, 39], and absence of validated outcome measures [38–40]. Intervention strategies have seldom been guided by theory [37, 39]. However, culture significantly influences stigma and interventions for reducing schizophrenia stigma often overlook cultural impacts in their design and implementation. Hence, it is crucial to conduct a pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial (RCT) that incorporates cultural and empathy factors to reduce schizophrenia stigma in nursing students in mainland China.

The objectives of this study are as follows:

To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the study intervention.

To compare the efficacy between the experimental and control groups of the Chinese culture-specific intervention in decreasing schizophrenia stigma among nursing students.

The hypotheses of this study were:

The Chinese culture-specific intervention program will be feasible and acceptable to the participants.

There will be significant differences between an experimental group and a control group in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and intentional behaviour regarding schizophrenia, and empathy towards people with schizophrenia, after the intervention and at a 3-month follow-up assessment.

Theoretical framework

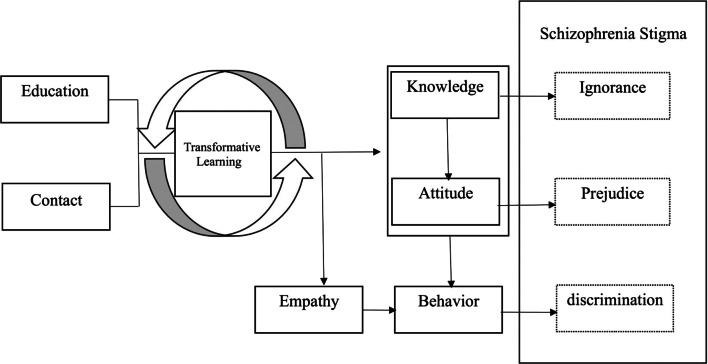

The development of the intervention in this study was guided by transformative learning theory [41] and the knowledge-attitude-behaviour (KAB) paradigm [42]. The intervention incorporated elements of education and contact, as well as cultural and empathy factors. Transformative learning is a process through which individuals can change their beliefs, assumptions, and experiences by examining them from new and different perspectives [41]. The following four transformative learning methods in education may be useful for developing nursing students’ empathy and positive attitudes towards individuals with schizophrenia and improving their knowledge of schizophrenia: investigative learning activities, collaborative learning activities, interactive learning activities, and higher-order thinking activities [43]. Thornicroft proposed that stigma is constructed in three domains: knowledge, which can lead to ignorance; attitudes, which can lead to prejudice; and behaviour, which can lead to discrimination [44]. The goal was to target al.l three domains of stigma – knowledge (ignorance), attitude (prejudice), and behaviour (discrimination) –to transform fourth-year nursing students’ understanding of schizophrenia knowledge, attitudes towards schizophrenia, and intentional behaviour towards individuals with schizophrenia. The theoretical framework was depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The theoretical framework of intervention in decreasing schizophrenia stigma

This theoretical framework illustrates that interventions implemented in the experimental group consisted of education and contact with individuals recovering from schizophrenia, as well as nurses working in the psychiatry department. The educational and contact components adhered to the principles of transformative learning theory, which incorporated investigative, collaborative, interactive, and higher-order thinking activities. These activities were designed to enhance participants’ knowledge of schizophrenia, foster empathy towards individuals living with the condition, and mitigate negative attitudes towards them. Consequently, participants’ ignorance and prejudice towards schizophrenia decreased. Finally, a decrease in participants’ discriminatory behaviours towards individuals with schizophrenia is anticipated.

Trial registration

The results of this study revealed that the Chinese culture-specific online intervention was both feasible and well-received among fourth-year nursing students for reducing schizophrenia stigma.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSEARS20220127002 on 22 February 2022) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Xiangya Hospital (KE202203129 on 18 March 2022). Informed consent is obtained from every participant, involved in the study. The participants were furnished with an information sheet and reminded of the voluntary nature of the research. All participant information remained confidential and will be securely disposed of 3 years following the study’s conclusion. All participants received a concise written and verbal overview of the study, and they were requested to sign a written consent form before the study’s initiation. The training program ensured the safety of all participants. If at any point during the training the participants felt uncomfortable, they were able to withdraw from the training without any consequences. Additionally, if any of the participants required professional psychological assistance, it was provided to them promptly. Each participant involved in the study was offered 100 Chinese yuan to compensate them for their time.

Methods

Trial design

This pilot RCT was a single-centre, two-armed, and open-label study. Sixty fourth-year nursing students were assigned randomly to either the experimental group or the control group, with an equal distribution of individuals within each group. The experimental group (n = 30) underwent a 4-week training program. The design of this program was derived from a systematic review of effective interventions, the findings from the focus group interviews, and consultations with fourth-year nursing students and experts.

Participant timelines

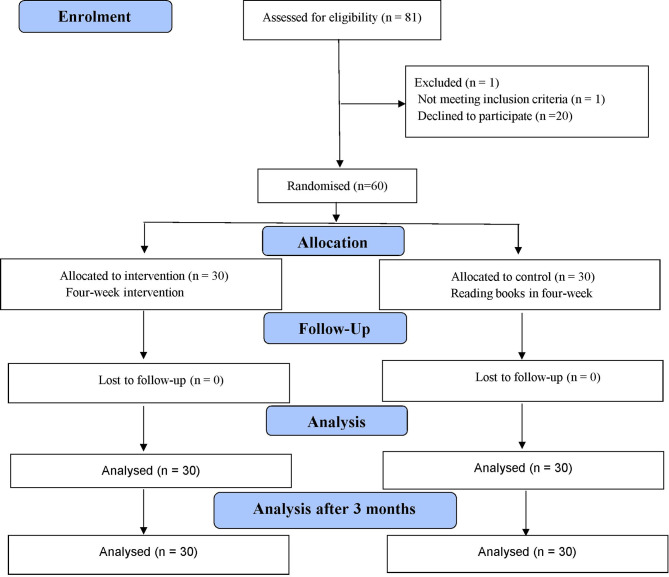

The training program lasted for four weeks, and its efficacy was assessed at three time points: initial measurement (T1), immediately after the four-week intervention (T2), and after the 3-month follow-up (T3). The trial procedure is presented as a flow diagram (Fig. 2) in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines [45].

Fig. 2.

The trial procedure is presented as a flow diagram

Study setting

This study was conducted at a single hospital, and all of the interventions were delivered online via the Tencent conference platform. The target hospital did not have a psychiatry department and all potential participants had no clinical experience in psychiatric nursing.

Participants

The participants were fourth-year nursing students undertaking their clinical placement at the hospital for a minimum of 10 months from August 2022 to June 2023. They had completed all theoretical subjects in their nursing program including a subject about mental illness and psychiatric nursing through traditional lectures and teacher-led instruction. However, most lacked practical experience in interacting with individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, potentially resulting in a similar level of understanding on mental health nursing.

Sampling

Convenience sampling was utilised to obtain the study sample.

Sample size

A review of the literature regarding sample size calculations for feasibility studies indicated that the sample size for the present study should range from 24 to 50 participants [46, 47]. Given that a 20% attrition rate is commonly observed in psychosocial intervention studies [48], the sample size calculation process is as follows:

|

Thus, the sample size was set to 60, with 30 participants in each group (experimental and control groups). A total of 390 nursing students were undergoing clinical placement in the target hospital, coming from different universities in mainland China. These nursing students included third-year, fourth-year, and fifth-year students, as well as graduate nursing students. Typically, fourth and fifth-year nursing students earn bachelor’s degrees, following a different educational process. Third-year nursing students graduate from nursing college and obtain a college degree, which differs from a bachelor’s degree.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Eligible individuals were those who:

Were aged 18 years or older;

Had completed all the necessary courses in their nursing program and thus, possessed comparable theoretical knowledge in the field of psychiatric nursing;

Were able to converse in Mandarin;

Voluntarily agreed to participate in this research;

Were undertaking their clinical placement at Xiangya Hospital, Changsha, Hunan Province (as this hospital does not have a psychiatry department, such students do not undertake their clinical placement in a psychiatry department); and

Were in the final (i.e., fourth) year of their university studies (Some nursing students receive 3 years of college education, whereas others receive 5 years of university education. These nursing students have different educational schedules from those of fourth-year university nursing students).

Exclusion criteria

Ineligible individuals were those who:

Were experiencing an episode of schizophrenia or other mental illness and were receiving medication;

Lacked the necessary equipment to participate in an online interview;

Had maintained regular personal contact with an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia or other mental health condition (e.g., had provided care for individuals with mental health disorders, as previous studies have shown that regular contact with individuals with a mental disorder can decrease the contacts’ stigma towards mental illness); or

Had participated previously in a similar intervention.

Participant recruitment procedure

Sixty fourth-year nursing students who were undertaking their clinical placement in the target hospital were recruited using a convenience sampling procedure by promoting the study through QQ Apps and WeChat Apps. QQ and WeChat are two Apps similar to WhatsApp that are widely used for communication in mainland China. We requested some of these nursing students to assist us in disseminating the study enrolment information through QQ and WeChat to all of the recruited students. The recruitment procedure followed the CONSORT guidelines [49], as shown in Fig. 2. A research assistant (the first one) was responsible for screening the students and collecting written informed consent from eligible participants.

Random allocation and allocation concealment

Sixty eligible subjects were allocated randomly to either the experimental group or the control group. Block randomisation using randomly permuted block sizes of 4, 6, and 8 was conducted through a website (https://www.sealedenvelope.com/simple-randomiser/v1/lists). After the baseline assessment, the first research assistant sequentially delivered opaque envelopes that contained a unique code without any grouping information for each participant. This research assistant was blinded to the study arms, and the principal investigator did not participate in the three sessions of data collection.

Blinding

This was an open-label study, as it was impossible in practice to conceal information from both the participants and the implementer of the intervention. There were two research assistants in this study. To minimise allocation bias, the first research assistant was blinded, as mentioned above. The second research assistant had access to the grouping and unique code information and directed the participants to join the indicated group after the first research assistant finished delivering the envelope, but he did not know which group was the intervention group. Thereafter, the second research assistant withdrew from the study and did not contact the study researchers until after the study had finished. The first research assistant responsible for gathering and inputting data for analysis was blinded to the group allocations. To further minimise bias, a third research assistant was involved in the data analysis and was blinded to the group allocation. To avoid the risk of contamination among them, all participants were asked not to share any information that they received during the study period.

Interventions

Experimental group: 4-week training program

The 30 participants in the experimental group were split into two subgroups, each comprising 15 participants. To enhance cooperation and facilitate the completion of the intervention, these 15 participants underwent the intervention concurrently and were further divided into three sub-subgroups, each comprising five participants. The participants in the experimental group received a 4-week intervention program, with some training program incorporating culturally specific elements and through education and contact process to implement the specific intervention. The detailed process of implementing the intervention is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The intervention implementation process

| Aim of the intervention | Intervention contents | Intervention methods and activities | Intervention time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First week |

The intervention in the first week aimed to improve the knowledge and understanding of schizophrenia. |

A. Knowledge about the aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, treatment, nursing, and prognosis of schizophrenia B. Differences between schizophrenia and other mental illnesses, such as multiple personality disorder, autism, depression, and psychopathy C. Schizophrenia-related legal issues D. The influence of cultural factors on the recognition of schizophrenia |

In week 1, all five students in each subgroup worked as a team (collaborative learning activity) to investigate knowledge (investigative learning activity). They reported their findings through presentations, discussions, and debates (interactive learning activity). These groups of five students analysed, constructed, and evaluated the information to make sense of their acquired knowledge. The students were engaged in (higher-order thinking) activity when analysing this information. | Each group had 35 min to report, and 15 min for Q&A, discussion, and comment. The total duration was 2.5 h. |

| Second week | The intervention in the second week aimed to correct the misconceptions about schizophrenia obtained from social media. | Hyperbolic reports about schizophrenia on the Internet and in literary works, novels, films, and TV plays | In week 2, groups of five students worked as a team (collaborative learning activity) to collect materials from the Internet, literary and artistic works, novels, films, and TV series with exaggerated reports about schizophrenia (investigative learning activity). Each group found 10 items containing exaggerated propaganda about the abnormal behaviour and actions of people with schizophrenia (higher-order thinking). These groups also needed to establish the truth about misconceptions of schizophrenia and discuss or debate them (interactive learning activity). | Each group was required to find 10 items and explain them. Each group had 35 min to report, and 15 min for Q&A, discussion, and comment. The total duration was 2.5 h. |

|

Third week |

The intervention in the third week aimed to contact people recovering from schizophrenia and psychiatric nurses. | Nursing students interacted with people recovering from schizophrenia. These people shared their experiences of the overall treatment and rehabilitation period. Nursing students had interactive communication with psychiatric nurses. The nurses shared their working experiences and their feelings about working in the psychiatric department. | In week 3, groups of five students worked as a team (collaborative learning activity) to prepare 10 questions (investigative learning activity) before meeting clients who were recovering from schizophrenia and psychiatric nurses. The clients and nurses shared their experiences and feelings to correct the students’ misconceptions. Higher-order thinking skills were involved. There was Q&A, discussion, and debate during or after the interview (interactive learning activity). |

The total duration was 3 h, including the interview with two people recovering from schizophrenia and two psychiatric nurses, and a Q&A session. |

| Fourth week |

The interventions in the fourth week involved self-reflection and concept mapping to deal with stigma. An understanding of schizophrenia in Chinese traditional culture and religion, and the understanding and views of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism regarding schizophrenia were achieved through nursing students’ self-reflection and thinking. |

Nursing students were required to undertake reflective critical and imaginative thinking autonomously on the following assigned topics Nursing students were engaged in a teamwork exercise using a concept map to identify strategies to reduce schizophrenia stigma. |

In week 4, nursing students were asked to write down their feelings (Subjects: ‘If I suffered from schizophrenia, how would I live, get treatment, recover, and reintegrate, how would I face the stigmatisation of schizophrenia by Chinese traditional culture and religion, and how would I feel when I encountered stigma?’) (investigative learning activity), read other nursing students’ opinions, and hold discussions or debates (interactive learning activity). After that, groups of five students worked as a team (collaborative learning activity) to develop concept maps for the identified problems and solutions (higher-order thinking activity). |

The total duration was 3 h. |

Control group

The control group participants were given a book titled The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness (Chinese version) by Elyn Saks, and were instructed to read it fully within a 4-week period. This book is the account of an accomplished professor living with schizophrenia, describing her symptoms, her efforts to hide the severity of the condition, her journey through therapy and marriage, and the obstacles she had to overcome.

Intervention adherence

Both groups of participants were able to seek guidance or ask any questions about the study by contacting the research assistant via WeChat or QQ. Additionally, the research assistant promptly reminded the participants to complete the required interventions before the end of each week. For instance, the participants in the control group were gently reminded twice each week to read 25% of the book before the end of the week.

Outcome measures

Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy

A summary of the outcome measures that were used to establish the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the intervention is shown in Table 2.

The Chinese version of the Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test (KAST) [50] was utilised to evaluate the participants’ understanding of schizophrenia. The KAST consists of 18 items [51] and possesses a reliable coefficient of 0.68, which is deemed acceptable [50]. The Chinese version of the KAST uses dichotomous variables, to which scores of 0 or 1 are assigned. Participants receive one point for each correct answer, and zero points for incorrect answers. The total attainable score spans from 0 to 18, with a lower score indicating less knowledge of schizophrenia. The content validity index (CVI) for the items varies between 0.83 and 1.00, while the CVI for universal agreement among experts and the average CVI of the scale are 0.83 and 0.97, respectively [50]. The validity of this tool is satisfactory. The Kuder–Richardson 20 (KR-20) of KAST is 0.70 [52] in another study and 0.47 in this study.

The Chinese version of the Mental Illness Clinicians’ Attitudes Scale (MICA) [53, 54] was employed to measure the participants’ stigma-related attitudes towards mental disorders. The MICA consists of 16 items assessed using a 6-point scale, with response choices ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 6 (totally disagree) [55]. A higher score indicates more severe negative stigma. The Chinese version of the MICA has shown strong Cronbach’s Alpha value 0.72, and the test–retest reliability 0.76 [56]. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of MICA is 0.63 in this study.

The Chinese version of the Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS) [54] was used to assess the stigma-related behaviours exhibited by the participants towards mental illness. The RIBS consists of eight items that are evaluated using a 5-point scale, where the response choices extend from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) [57]. The total score is calculated by summing the scores for the responses to items 5 to 8, and ranges from 4 to 20, with a higher score indicating a greater inclination to engage with individuals who have a mental illness. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of the RIBS is 0.82 and its test–retest reliability is 0.68 in the previous study [54]. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of the RIBS in this study is 0.76.

-

The Chinese version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Nursing Students’ version R (JSE-NSR) [58] was utilised to assess the participants’ empathy level for people with schizophrenia. The JSE-NSR consists of 20 items assessed using a 7-point scale, with response choices spanning from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) [59]. The potential overall score varies from 20 to 140, with a higher score signifying a greater degree of empathy. The Chinese version of the JSE-NSR exhibits Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.74 and test–retest reliability of 0.84 in previous study [60]. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of the JSE-NSR in this study is 0.78.

The RIBS and MICA scales are freely available for use after registration on the website: https://www.indigo-group.org/new-guide-to-scales/.

Table 2.

Outcome measures feasibility of the intervention

| Primary outcome | Feasibility outcomes |

Subject recruitment -Achievable recruitment rate -Consent rate -eligibility rate Feasibility of the measurement tools |

| Acceptability outcomes |

Prospective acceptability -Recruitment rate Concurrent acceptability -Dropout rates -Intervention attendance rates -Retention rates -Intervention completion rates Acceptability of randomisation |

|

| Preliminary efficacy |

Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test Mental Illness Clinicians’ Attitudes Scale Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Nursing Students’ version R |

|

Data collection

The online platform Wen Juan Xing was used to administer study-related surveys and collect data on intervention outcomes for this pilot RCT. The data were collected from February 20 to June 20, 2023. The login credentials for the platform were restricted to the principal investigator of this study, and all of the data were used solely for research purposes.

Data analysis and management

The demographic traits of the participants were condensed into descriptive statistics, including means, SDs, and percentages, where appropriate. The feasibility and acceptability outcomes are presented as percentages. Differences in demographic and outcome variables between the intervention and control groups were calculated at T1. We employed independent Student’s t-tests for continuous variables, chi-square tests for nominal variables, and Wilcoxon signed rank tests for data that did not meet the assumptions for parametric tests. The effectiveness of the intervention compared with the control treatment at T1, T2, and T3 was analysed using generalised estimating equations (GEEs). All data were analysed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), with the significance threshold set at P < 0.05 [61].

The scores of the participants were gathered, coded, and entered into SPSS 26.0 to create a database. Raw data were double-checked to ensure accuracy. The confidentiality of the data was maintained, and the participants remained anonymous, as only a code represented their identity. Personal information was excluded from the analysis, and all of the electronic files were stored using U-disk encryption and were only accessible to the researcher via a password or to others who were authorised to access them.

Results

Demographics

There were 48 females and 12 males who completed the study. Thirty-four participants were aged between 20 and 21, while 26 participants were aged between 22 and 23. Only two participants were of rare ethnicity. There were no notable distinctions in the demographic characteristics of the participants between the experimental and control groups. Moreover, there was a positive outcome as there were no dropouts during the study. The detailed demographic information among participants is shown in Table 3. The participants’ baseline scores for the four scales are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

The detailed demographic information among participants

| Demographic characteristics | Baseline demographics of study participants, n (%)/mean ± SD | Group difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants n (%) |

Intervention n (%) |

Control n (%) |

χ2 | P value | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 48 (80.00) | 23 (76.67) | 25 (83.33) | 0.417a | 0.519 |

| Male | 12 (20.00) | 7 (23.33) | 5 (16.67) | ||

| Age (Years) | |||||

| 20–21 | 34 (56.67) | 15 (50.00) | 19 (63.33) | 1.086a | 0.297 |

| 22–23 | 26 (43.33) | 15 (50.00) | 11 (36.67) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 55 (91.67) | 27 (90.00) | 28 (93.33) | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| Other | 5 (8.33) | 3 (10.00) | 2 (6.67) | ||

| University of Hunan Province | |||||

| Yes | 7 (11.67) | 4 (13.33) | 3 (10.00) | 0.000b | 1.000 |

| No | 53 (88.33) | 26 (86.67) | 27 (90.00) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| Unmarried | 60 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | ||

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Province | |||||

| Hunan | 40 (66.67) | 20 (66.67) | 20 (66.67) | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| Other | 20 (33.33) | 10 (33.33) | 10 (33.33) | ||

| Grade | |||||

| 4 | 60 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Religious beliefs | |||||

| Yes | 3 (5.00) | 2 (6.67) | 1 (3.33) | 0.000b | 1.000 |

| No | 57 (95.00) | 28 (93.33) | 29 (96.67) | ||

| Do you have friends or family members with mental illness issues? | |||||

| Yes | 13 (21.67) | 4 (13.33) | 9 (30.00) | 2.445a | 0.117 |

| No | 47 (78.33) | 26 (86.67) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Have you had contact with groups or individuals with schizophrenia? | |||||

| Yes | 26 (43.33) | 11 (36.67) | 15 (50.00) | 1.086a | 0.297 |

| No | 34 (56.67) | 19 (63.33) | 15 (50.00) | ||

| Have you had a mental illness before? | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| No | 60 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | ||

| Have you participated in similar studies before? | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 1.000 |

| No | 60 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | 30 (100.00) | ||

Note: The participants (N = 60) were randomly assigned to the Experimental group and control group

Table 4.

Comparison of baseline scores for the four scales between the experimental and control groups using an independent-samples student’s t-test

| Scale | Baseline demographics in study groups, n (%)/Mean ± SD | Group difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants n (%) |

Experimental n (%) |

Control n (%) |

χ2/t | P value | |

| KAST | 11.17 (2.40) | 11.53 (2.53) | 10.80 (2.25) | 1.187 | 0.240 |

| MICA | 45.88 (6.30) | 45.87 (6.47) | 45.90 (6.23) | -0.020 | 0.984 |

| RIBS | 12.83 (2.74) | 12.80 (2.89) | 12.87 (2.62) | -0.094 | 0.926 |

| JSE-NS | 111.82 (8.83) | 111.57 (10.19) | 112.07 (7.39) | -0.218 | 0.829 |

Note:

KAST: Chinese version of the Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test

MICA: Mental Illness Clinicians Attitudes Scale

RIBS: Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale

JSE-NS: Jefferson Scale of Empathy- Nursing students Version R

Primary outcome

Feasibility outcomes

The subject recruitment for this study was successfully conducted with the assistance of the Nursing Department of Xiangya Hospital. It took 26 days (26 January 2023 to 20 February 2023) to recruit participants from Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The overall recruitment rate for this project was approximately three participants per day. Out of the 81 participants recruited, one third-year nursing student did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in an eligibility rate of 98.77% (80 out of 81). Among the screened participants, the recruitment rate was 75.00% (60 out of 80). Eighty fourth-year nursing students showed interest in participating in this research, but only 60 nursing students finally participated. The achievable recruitment rate was 15.38% (60 out of 390), as the total number of nursing students in their fourth year who engaged in clinical placements at the specified hospital was 390. The response rate for the scales used in the study was 100.00%, and the participants completed the scales within 2 days at T1, T2, and T3, with no missing values on any of the scale items, which indicated good feasibility of the measurement tools. The retention rate for participants in both the experimental and control groups was 100.00%.

Acceptability outcomes

The prospective acceptability was good, as the recruitment rate was 75%, with 60 nursing students participating in the intervention among the total of 80 fourth-year nursing students who had shown interest in participating. The concurrent acceptability was good, with all nursing students adhering to the program and actively engaging in the intervention. There were no dropouts in any intervention session, resulting in a 100% intervention attendance rate, retention rate, and intervention completion rate. The acceptability of randomisation was also good, as all participants expressed willingness to comply with the randomisation process and be allocated to either the experimental or control groups.

Secondary outcomes - preliminary efficacy of the intervention

Table 5 lists the outcome information of four scales (KAST, MICA, RIBS, and JSE-NS) that assess the efficacy of the intervention comparison between the experimental and control groups was performed at three time points using paired T-tests or Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Table 5 shows that in the experimental group and control group, the KAST scores increased significantly at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05). The MICA scores decreased significantly at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05) in the experimental group, the RIBS scores increased significantly at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05) in the experimental group, and the JSE-NS score increased significantly at T3 (p < 0.05) in the experimental group. However, there were no significant changes in the control group across the MICA, RIBS, and JSE-NS scales at the three time points. Detailed information regarding the paired t-tests between the two groups is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The efficacy of the intervention comparison between the experimental and control groups at three time points

| Experimental group (N = 30) | Control group (N = 30) | t/P value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | t 1 | P | t2 | P | t 3 | P | t 4 | P | |

| Mean (SD) | ||||||||||||||

| KAST |

11.53 (2.53) |

12.97 (1.79) |

13.30 (2.02) |

10.80 (2.25) | 12.43 (2.01) | 12.83 (1.84) | -3.053b | 0.002 | -3.154b | 0.002 | -3.642 | 0.001 | -3.671b | <0.001 |

| MICA |

45.87 (6.47) |

40.40 (6.55) |

38.57 (6.14) |

45.90 (6.23) | 44.13 (5.36) | 44.30 (7.12) | 3.807 | <0.001 | 5.967 | <0.001 | 1.946 | 0.061 | 1.264 | 0.216 |

| RIBS |

12.80 (2.89) |

15.07 (2.59) |

14.73 (2.41) |

12.87 (2.62) | 13.90 (2.01) | 13.53 (2.43) | -4.025 | <0.001 | -3.417b | <0.001 | -2.014 | 0.053 | -1.262 | 0.217 |

| JSE-NS |

111.57 (10.19) |

115.27 (8.91) |

116.33 (10.52) |

112.07 (7.39) | 111.90 (7.33) |

110.20 (8.28) |

-1.951 | 0.061 | -2.491 | 0.019 | 0.121 | 0.905 | 1.016 | 0.318 |

T1: baseline; T2: post-intervention; T3: 3-month follow-up. b: Wilcoxon signed rank comparisons

t 1: t value of experimental group in baseline and post-intervention comparison

t 2: t value of experimental group in baseline and 3-month follow-up comparison

t 3: t value of control group in baseline and post-intervention comparison

t4: t value of control group in baseline and 3-month follow-up comparison

KAST: Chinese version of the Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test; MICA: Mental Illness Clinicians Attitudes Scale; RIBS: Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale; JSE-NS: Jefferson Scale of Empathy- Nursing students Version R

Table 6 presents the results of the GEE analysis, assessing the group, time, and group* time interaction effects on knowledge about schizophrenia, stigma-related attitude, intentional behaviour toward schizophrenia, and empathy towards schizophrenia reduction. The interaction between time showed that the increase in the stigma-related knowledge score of the two groups was significantly higher at T2 (Wald χ² = 13.723, P < 0.001) and T3 (Wald χ² = 24.012, P < 0.001), respectively, compared to the stigma-related knowledge score at T1.

Table 6.

Generalised estimating equation (GEE) models assessing the intervention outcomes of knowledge about schizophrenia, stigma-related attitudes, stigma-related behaviour, and level of empathy for people with schizophrenia (experimental group = 30 and control group = 30)

| Measures | Mean (SD) | Tests of GEE model effects | Effect size (95% CI) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | Time effect | Group effect | Group-by-time effect | ||||||||||

| T2 | T3 | T2 | T3 | T2 | T3 | ||||||||||

| Wald χ2 | P | Wald χ2 | P | Wald χ2 | P | Wald χ2 | P | Wald χ2 | P | d | |||||

| KAST score | 5.121 | <0.001 | 7.640 | <0.001 | 2.082 | 0.227 | 0.819 | 0.734 | 0.766 | 0.673 |

0.2837 (-0.2249-0.7923) |

0.2433 (-0.2647-0.7512) |

|||

| Experimental group |

11.53 (2.53) |

12.97 (1.79) |

13.30 (2.02) |

||||||||||||

| Control group | 10.80 (2.25) | 12.43 (2.01) | 12.83 (1.84) | ||||||||||||

| MICA score | 0.171 | 0.048 | 0.202 | 0.198 | 0.967 | 0.984 | 0.025 | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

-0.6233 (-1.1415-0.1051) |

-0.8619 (-1.3909-0.3329) |

|||

| Experimental group |

45.87 (6.47) |

40.40 (6.55) |

38.57 (6.14) |

||||||||||||

| Control group | 45.90 (6.23) | 44.13 (5.36) | 44.30 (7.12) | ||||||||||||

|

RIBS score |

2.810 | 0.040 | 1.948 | 0.199 | 0.936 | 0.924 | 3.433 | 0.100 | 3.549 | 0.082 |

0.5047 (-0.0094-1.0188) |

0.4959 (-0.0179-1.0096) |

|||

| Experimental group |

12.80 (2.89) |

15.07 (2.59) |

14.73 (2.41) |

||||||||||||

| Control group | 12.87 (2.62) | 13.90 (2.01) | 13.53 (2.43) | ||||||||||||

| JSE-NSR score | 0.846 | 0.902 | 0.155 | 0.302 | 0.607 | 0.852 | 47.783 | 0.094 | 760.011 | 0.011 |

0.4131 (-0.0984-0.9245) |

0.6475 (0.1284–1.1667) |

|||

| Experimental group |

111.57 (10.19) |

115.27 (8.91) |

116.33 (10.52) |

||||||||||||

| Control group | 112.07 (7.39) | 111.90 (7.33) |

110.20 (8.28) |

||||||||||||

T1: baseline; T2: post-intervention; T3: 3-month follow-up

a Reference: control group

b Reference: baseline

c Reference: control group × baseline

d ES: effect size, based on the between-group differences in the mean change and the pooled baseline SD of the 2 groups

KAST: Chinese version of the Knowledge about Schizophrenia Test

MICA: Mental Illness Clinicians Attitudes Scale

RIBS: Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale

JSE-NS: Jefferson Scale of Empathy- Nursing students Version R

The interaction between time showed that the decrease in the stigma-related attitude score of the two groups was significantly lower at T2 (Wald χ² = 3.916, P = 0.048) compared to the stigma-related attitude score at T1. The interaction between the group and time revealed that the reduction in the stigma-related attitude score of the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group at T2 (Wald χ² = 4.907, P = 0.027) and T3 (Wald χ² = 10.848, P = 0.001), respectively, compared to the stigma-related attitude score at T1.

The interaction involving time demonstrated that the reduction in the stigma-related behaviour score at T2 (Wald χ² = 4.197, P = 0.040) was significantly lower compared to the stigma-related behaviour score at T1.

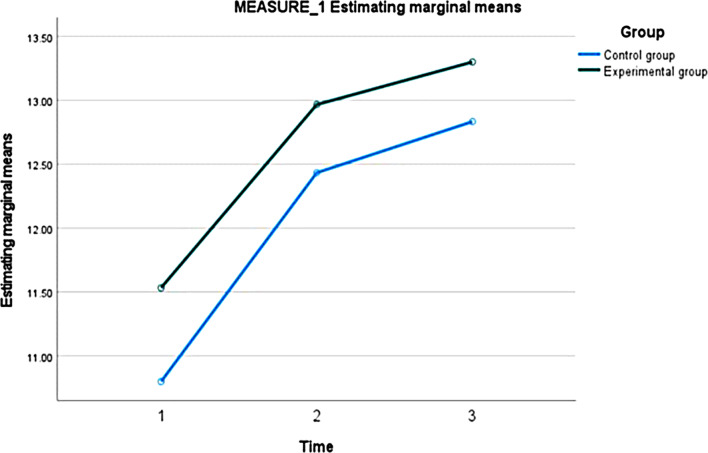

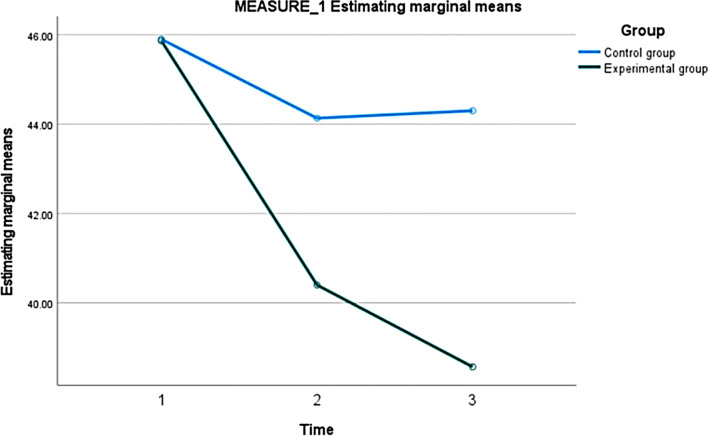

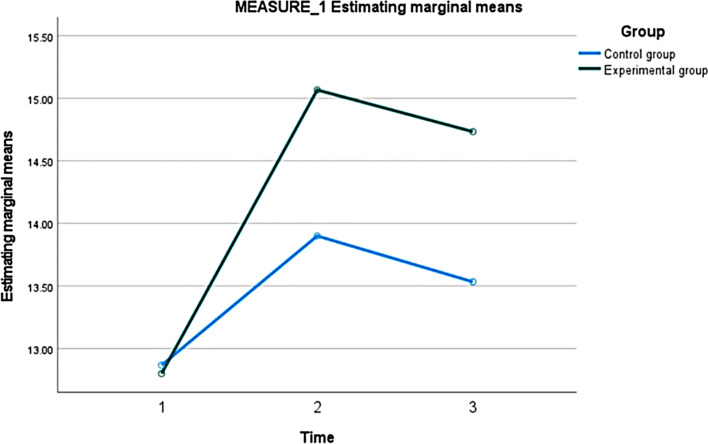

Furthermore, the interaction between the group and time indicated that the experimental group showed a significant improvement in the level of empathy score compared to the control group (Wald χ 2 = 6.466, P = 0.011) at T3. Detailed information regarding the GEE analysis can be found in Table 6. Figures 3, 4 and 5, and 6 depict the trend in scores for the four scales across three time points of the pilot RCT.

Fig. 3.

The knowledge score between two groups at three time points

Fig. 4.

The attitude score between two groups at three time points

Fig. 5.

The behaviour score between two groups at three time points

Fig. 6.

The empathy score between two groups at three time points

Discussion

Feasibility of the study

The findings of this study indicated that an online mode Chinese culture-specific intervention aimed at reducing schizophrenia stigma is feasible and acceptable for nursing students. Participant recruitment was completed in less than a month, with high rates of consent and eligibility. We engaged participants to help disseminate information about the study, which facilitated rapid recruitment. This discovery indicates that mobilizing participants to spread study information could potentially reduce the time of participants’ enrolment. Furthermore, 60 participants completed the assessment scales at each designated time point without any missing items. This indicates that the measurement tools utilized in this study demonstrated good feasibility. Therefore, these measurement tools may be suitable for use in future full-scale RCTs. A study conducted in the USA involved 145 nursing students and aimed to decrease their stigma attitudes towards schizophrenia through simulation. Remarkably, the study also had no dropouts [62].

In this study, the recruitment rate (the number of offers accepted by the total number of offers delivered to potential participants) did not meet our initial expectations, and participants provided reasons for their non-participation. These reasons included being occupied with tasks such as preparing their thesis, searching for jobs, undergoing postgraduate re-examinations, and participating in nursing skill competitions. These findings suggested that for future full-scale RCT studies, it would be beneficial to plan the implementation of the study for nursing students who are engaged in clinical placements. These placements typically last for at least 10 months, from August to June of the following year. Therefore, the ideal time to implement the study may be during the middle of the clinical placement period. This timing allows nursing students to become familiar with clinical work and gain experience, while also less anxiety about future job prospects or post-placement plans. In terms of acceptability, this study demonstrated favourable results. All participants attended every session of the intervention, resulting in a 0% dropout rate and 100% attendance, retention, and completion rates. Furthermore, no participants expressed a desire to switch groups after randomization, indicating a high level of acceptability regarding the randomization process. The high feasibility and acceptability of the intervention suggest that the design and implementation were effective, making it potentially applicable to other health professional students or staff in the future.

Preliminary efficacy of the study

In this study, compared with the baseline, participants in the experimental group showed improvements in knowledge, attitude, intentional behaviour, and empathy towards schizophrenia based on paired T-tests. The control group only showed improvements in knowledge towards schizophrenia based on paired T-tests. These findings suggest that the intervention was effective in decreasing nursing students’ stigma towards schizophrenia in the experimental group. The intervention in this study combined education and contact to decrease schizophrenia stigma. A meta-analysis by Griffiths (2014) found that education and contact are effective in decreasing stigma towards mental illness [63]. These findings were similar to previous studies in decreasing schizophrenia stigma among health professional students through combined education and contact interventions [40, 64]. Compared with the control group, it appears that the experimental group may perform better in decreasing schizophrenia stigma. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Sharif (2015) which also found that a multicomponent approach was more effective than other approaches for reducing stigma towards mental illness [65]. Thus, future full trials should follow the findings of the above-mentioned studies by employing a combination of education and contact methods in an effort to decrease schizophrenia stigma [63, 65].

The results of the GEE analysis demonstrated that both the experimental and control groups showed improvements in schizophrenia knowledge following the intervention, despite the relatively small effect size, variations of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 SDs, which are classified as ‘small,’ ‘medium,’ and ‘large’ effect sizes, respectively [66]. This is in accordance with the observed schizophrenia knowledge values of 0.28 at T2 and 0.24 at T3 for the experimental group. Theoretical lessons can significantly enhance healthcare professional students’ understanding of schizophrenia [40, 67]. However, many of these studies fail to report the effect size, hindering a comprehensive assessment of their efficacy. One study conducted in Italy, however, reported a substantial effect size (d = 0.67) for improving medical students’ schizophrenia knowledge through psychiatry internships [68]. The positive effects of the intervention persisted for 3 months, as shown in Fig. 3. Despite the experimental group receiving the intervention and the control group reading a book, it appears that both approaches were equally effective at enhancing schizophrenia knowledge. When comparing the two approaches, it appears that reading a book is a more cost-effective option for reducing schizophrenia stigma.

The GEE analysis results indicate a noteworthy reduction in stigmatizing attitudes towards schizophrenia in the experimental group after the intervention compared to the baseline, with a large effect size of 0.62 at T2 and 0.86 at T3, respectively, and remained consistent for 3 months following the intervention, as shown in Fig. 4. This study developed a culturally specific intervention involving education and contact to effectively decrease nursing students’ stigmatising attitudes towards schizophrenia, and achieved a notable effect size. Unlike previous studies targeting nursing students’ schizophrenia-stigmatizing attitudes, our study stands out with a 3-month follow-up period, hinting at potentially superior long-term efficacy for the intervention. This may be attributed to the extended intervention period, as the entire intervention spanned 4 weeks. Previous studies seldom extended to this duration, yet still yielded significant reductions in schizophrenia stigma. This study involved a high frequency of interventions and required a relatively greater time commitment, thus potentially leading to a more profound and far-reaching impact on reducing schizophrenia stigma among participants.

The results of the GEE analysis show that the experimental group’s intentional behaviour towards schizophrenia showed an improvement after the intervention compared with the baseline, with medium effect sizes of 0.50 and 0.50 at T2 and T3, respectively. While the stigma-related behaviour scores significantly increased at T2 compared to the baseline score at T1, this change did not persist until T3, as shown in Fig. 5. In a pilot study conducted in Hong Kong with 49 participants, which differs from our study, a significant improvement in mental illness knowledge was reported, but no change in intentional behaviour towards mental illness was observed [69]. The absence of significant change in the control group participants in our study may be attributed to the limited sample size and the relatively brief follow-up duration.

The results of the GEE analysis show that the experimental group showed improved empathy towards schizophrenia at the 3-month follow-up after the intervention compared with the baseline, with medium to large effect sizes of 0.41 at T2 and 0.65 at T3, as shown in Fig. 6. A cross-sectional study in Spain involving 750 nurses reported that empathy is connected to more favourable attitudes towards people with mental disorders, leading to reduced stigma [70]. In this study, the participants in the experimental group demonstrated improved empathy, while the control group did not show the same improvement. This implies that the intervention proved to be effective at enhancing empathy towards individuals with schizophrenia in the experimental group. However, reading books about individuals’ experiences of recovering from schizophrenia did not improve empathy towards the condition.

The innovations and recommendations of this study

This study added the cultural and empathy factors in the intervention design, which were different from the previous studies. Individuals may not always be conscious of how their cultural background impacts them, leading them to believe that their choices are natural and instinctive [71]. In reality, culture and beliefs play a significant role in shaping an individual’s decision-making process [71]. Therefore, the experimental group in this study was reminded of traditional cultural factors that influence their cognition, attitudes, and behavioural intentions regarding schizophrenia. Previous study conducted in mainland China to reduce mental illness stigma among nursing students did not consider cultural and empathy factors [31]. Hence, this study developed a unique intervention strategy that incorporates cultural and empathy factors specifically tailored to the population in mainland China, with the aim of reducing stigma towards schizophrenia.

In addition, only a few studies had the KAB theoretical framework guiding their interventions [53, 72]. In contrast, this intervention aimed to reduce schizophrenia stigma among nursing students and was guided by both transformative learning theory and the KAB paradigm. Furthermore, there have been very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) targeting the reduction of mental illness stigma among healthcare professionals and students. Therefore, this study provides additional evidence that supports the value of such RCTs and will be incorporated into future systematic reviews and used to guide the design of future studies. The significance of this study lies in the application of an online intervention program designed to reduce schizophrenia stigma among nursing students. This program offers participants flexibility in terms of when they can participate, which effectively helps to decrease dropout rates. Additionally, the online nature of the program may reduce the drop-out rate.

This study offers flexible options for reducing schizophrenia stigma among nursing students, proving particularly useful in situations where face-to-face interaction is restricted, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, findings of this study will contribute to the evidence of the effectiveness of educational and contact interventions in reducing schizophrenia stigma. Furthermore, this study will provide valuable evidence to support the development of culturally specific interventions targeting the reduction of schizophrenia and other forms of mental illness stigma in different countries. We anticipate that this study will yield empirical evidence regarding the effect size of our intervention, thereby facilitating the calculation of the required sample size for a full-scale trial of culture-specific intervention programs aimed at reducing the stigmatization of individuals with schizophrenia.

Limitations

Firstly, this study focused solely on fourth-year nursing students from a single hospital, which limited its generalizability due to the small sample size and restricted recruitment. Future studies should explore more diverse demographic areas to address barriers and facilitators in implementing the intervention. Secondly, this is a feasibility study and as such was not powered to detect significant differences between groups, which may result in distorted effect sizes and wide 95% confidence intervals. Additionally, future studies can investigate the effectiveness of individual intervention components. It’s worth noting that blinding participants was not feasible, and the potential Hawthorne effect should be considered. Lastly, regarding outcomes, the use of self-reported questionnaires introduced subjectivity into the results.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that the Chinese culture-specific online intervention was both feasible and well-received among fourth-year nursing students for reducing schizophrenia stigma. The intervention was crafted using the principles of transformational learning theory and the KAP paradigm. By addressing cultural influences, interventions can be developed to target and mitigate stigma associated with mental disorders among nursing students. A fully powered RCT with a substantial sample size is essential for conducting a more comprehensive examination and quantification of the intervention’s effects. Such future research could provide a more definitive understanding of the intervention’s impact and contribute to advancing knowledge in this area. Future research and practice should continue to investigate the role of culture in shaping attitudes towards mental disorders and develop evidence-based interventions that consider cultural nuances. Moreover, the design and findings of this study could serve as a good reference to help develop training curricula for nurses and intervention programs tailored to Chinese-specific culture aimed at reducing the stigma associated with mental illness, particularly schizophrenia, in mainland China.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all nursing students and rehabilitation people, nurses participated in this study.

Author contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. Xi Chen was responsible for the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; the software used in the work; drafting the work and substantively revising it. Shanshan Wang designed, drafted the work and substantively revised it. Xiaoli Liao and Hon Lon Tam involved in drafting the work and revising it. Yan Li, Sau Fong Leung, and Daniel Thomas Bressington supervised the design, contributed to the implementation of this study, drafted the work and substantively revised it.

Funding

This research was not supported by any Grant.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are not publicly available due to the confidential agreement of participants, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSEARS20220127002 on 22 February 2022) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Xiangya Hospital (KE202203129 on 18 March 2022). The participants were furnished with an information sheet and reminded of the voluntary nature of the research.

Consent for publication

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Valery KM, Prouteau A. Schizophrenia stigma in mental health professionals and associated factors: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113068. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113068. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. The Australian public’s beliefs about the causes of schizophrenia: associated factors and change over 16 years. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(1–2):609–14. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Schizophrenia. 2022. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia. Accessed 20 May 2022.

- 4.Hu YY. To reduce stigma in patients with schizophrenia in the group social work service. Wuhan, China: South-Central University for Nationalities; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EH, Hui CL, Ching EY, Lin J, Chang WC, Chan SK, Chen EY. Public stigma in China associated with schizophrenia, depression, attenuated psychosis syndrome, and psychosis-like experiences. Psychiatric Serv. 2016;67(7):766–70. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Cohen A, Weiss HA, Chatterjee S, Pereira J, Naik S, John S, Dabholkar H, Balaji M, Chavan A, Varghese M, Rangaswamy T, Thornicroft G, Patel V. Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Soc Sci Med. 2014;123:149–59. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen SY, Huang X, Chien C. The self-stigmatization of patients with schizophrenia: a phenomenological study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34(2):29–35. 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vass V, Sitko K, West S, Bentall RP. How stigma gets under the skin: the role of stigma, self-stigma and self-esteem in subjective recovery from psychosis. Psychosis. 2017;9(3):235–44. 10.1080/17522439.2017.1300184. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caqueo-Urizar A, Boyer L, Urzua A, Williams DR. Self-stigma in patients with schizophrenia: a multicentric study from three Latin-America countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(8):905–9. 10.1007/s00127-019-01671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maharjan S, Panthee B. Prevalence of self-stigma and its association with self-esteem among psychiatric patients in a Nepalese teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1). 10.1186/s12888-019-2344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ebrahim OS, Al-Attar G, Gabra RH, Osman DM. Stigma and burden of mental illness and their correlates among family caregivers of mentally ill patients. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1). 10.1186/s42506-020-00059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Grover S, Avasthi A, Singh A, Dan A, Neogi R, Kaur D, Lakdawala B, Rozatkar AR, Nebhinani N, Patra S, Sivashankar P, Subramanyam AA, Tripathi A, Gania AM, Singh G, Behere PB. Stigma experienced by caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders: a nationwide multicentric study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2017;63(5):407–17. 10.1177/0020764017709484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Njaka S, Ada BO, Chidinma ON, Nkechi UA. A systematic review on prevalence and perceived impacts of associative stigma on mental health professionals. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2023;18:100533. 10.1016/j.ijans.2023.100533. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samari E, Seow E, Chua BY, Ong HL, Lau Y, Mahendran R, Verma S, Xie H, Wang J, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Attitudes towards psychiatry amongst medical and nursing students in Singapore. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1). 10.1186/s12909-019-1518-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.WHO. Helping people with severe mental disorders live longer and healthier lives. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/policy_brief_on_severe_mental_disorders/en/

- 16.Sánchez-Martínez V, Sales-Orts R. Design and validation of a brief scale for cognitive evaluation in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (BCog-S). J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;27(5):543–52. 10.1111/jpm.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Lu S, Xie C, Li Y. Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental disorders among non-mental health nurses in general hospitals of china: a National survey. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1180034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Chang S, Ong HL, Seow E, Chua BY, Abdin E, Samari E, Subramaniam M. Stigma towards mental illness among medical and nursing students in singapore: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018099. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fei Y, Li F, Geng L, et al. A comparative study on mental illness attitudes between psychiatric clinical nurses and health school nurse students. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2016;22(22):3201–4.

- 20.Liu W. Recognition of, and beliefs about, causes of mental disorders: a cross-sectional study of US and Chinese undergraduate nursing students. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21(1):28–36. 10.1111/nhs.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawaz MA, Hamdan-Mansour AM, Tassi A. Challenges facing nursing education in the advanced healthcare environment. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2018;9:105–10. 10.1016/j.ijans.2018.10.005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang LH, Chen FP, Sia KJ, Lam J, Lam KKW, Ngo H, Lee P, Kleinman A, Good BJ. What matters most: a cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:84–93. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haddad M, Waqas A, Sukhera AB, Tarar AZ. The psychometric characteristics of the revised depression attitude questionnaire (R-DAQ) in Pakistani medical practitioners: a cross-sectional study of doctors in Lahore. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1). 10.1186/s13104-017-2652-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Waqas A, Malik S, Fida A, Abbas N, Mian N, Miryala S, Amray AN, Shah Z, Sattar N. Interventions to reduce stigma related to mental illnesses in educational institutes: a systematic review. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(3):887–903. 10.1007/s11126-020-09751-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang LH, Wonpat-Borja AJ. Causal beliefs and effects upon mental illness identification among Chinese immigrant relatives of individuals with psychosis. Commun Ment Health J. 2011;48(4):471–6. 10.1007/s10597-011-9464-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng W, Wu DYH. Chinese culture and mental health. Honolulu, Hawaii Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Academic; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis Α, Koukouli S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare. 2020;8(1):26. 10.3390/healthcare8010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batson CD, Chang J, Orr R, Rowland J. Empathy, attitudes, and action: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(12):1656–66. 10.1177/014616702237647. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra S, Jackson V, Chong J, Choe K, Tay C, Wong J, Yang LH. Systematic review of cultural aspects of stigma and mental illness among racial and ethnic minority groups in the united states: implications for interventions. Am J Community Psychol. 2021;68(3–4):486–512. 10.1002/ajcp.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(2):219–25. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu L, Jiao W, Xia H, Yu M. Psychiatric-mental health education with integrated role-play and real-world contact can reduce the stigma of nursing students towards people with mental illness. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;52:103009. 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.İnan FŞ, Günüşen NP, Duman ZÇ, Ertem M. The impact of mental health nursing module, clinical practice and an anti-stigma program on nursing students’ attitudes toward mental illness: a quasi-experimental study. J Prof Nurs. 2019;35(3):201–8. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palou RG, Vigué GP, Romeu-Labayen M, Tort-Nasarre G. Analysis of stigma in relation to behaviour and attitudes towards mental health as influenced by social desirability in nursing students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3213. 10.3390/ijerph19063213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Rivas ME, Cangas AJ, Martin A, Romo JCM, Pérez JC, Valdebenito S, Cariola LA, Onetto J, Hernandez BC, Cerić F, Cea P, Corrigan PW. Reducing stigma toward people with serious mental illness through a virtual reality intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Games Health J. 2024;13(1):57–64. 10.1089/g4h.2023.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shim YR, Eaker R, Park J. Mental health education, awareness and stigma regarding mental illness among college students. J Mental Health Clin Psychol. 2022;6(2):6–15. 10.29245/2578-2959/2022/2.1258. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Queirós RV, Santos V, Madeira N. Decrease in stigma towards mental illness in Portuguese medical students after a psychiatry course. Acta Med Port. 2021;34(7–8):498–506. 10.20344/amp.13859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amsalem D, Yang LH, Jankowski S, Lieff SA, Markowitz JC, Dixon LB. Reducing stigma toward individuals with schizophrenia using a brief video: a randomized controlled trial of young adults. Schizophr Bull. 2020;47(1):7–14. 10.1093/schbul/sbaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altındağ A, Yanık M, Üçok A, Alptekın K, Özkan M. Effects of an antistigma program on medical students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60(3):283–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galletly C, Burton C. Improving medical student attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):473–6. 10.3109/00048674.2011.541419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danacı AE, Balıkçı K, Aydın O, Cengisiz C, Uykur AB. The effect of medical education on attitudes towards schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2016. 10.5080/u13607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dincer B, Inangil D. The effect of affective learning on alexithymia, empathy, and attitude toward disabled persons in nursing students: a randomized controlled study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021. 10.1111/ppc.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kallgren CA, Wood W. Access to attitude-relevant information in memory as a determinant of attitude-behavior consistency. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(4):328–38. 10.1016/0022-1031(86)90018-1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsimane T, Downing C. Transformative learning in nursing education: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(1):91–8. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(3):192–3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Weeks L, Peters J, Kober T, Dias S, Schulz KF, Plint AC, Moher D. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Libr. 2012;2013(1). 10.1002/14651858.mr000030.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2005;4(4):287–91. 10.1002/pst.185. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):301–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Daele T, Hermans D, Van Audenhove C, Van Den Bergh O. Stress reduction through psychoeducation. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(4):474–85. 10.1177/1090198111419202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuschieri S. The CONSORT statement. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(1):S27–30. 10.4103/sja.SJA_559_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou C, Li Z, Arthur D. Psychometric evaluation of the illness perception questionnaire for schizophrenia in a Chinese population. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;50:101972. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Compton MT, Quintero L, Esterberg ML. Assessing knowledge of schizophrenia: development and psychometric properties of a brief, multiple-choice knowledge test for use across various samples. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151(1–2):87–95. 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang M, Zhao M, Zhang W, Li W, He R, Ding R, He P. Knowledge about schizophrenia test: the Chinese Mandarin version and its sociodemographic and clinical factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1). 10.1186/s12888-023-04822-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Kassam A, Glozier N, Leese M, Loughran J, Thornicroft G. A controlled trial of mental illness related stigma training for medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1). 10.1186/1472-6920-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Li J, Li J, Thornicroft G, Huang Y. Levels of stigma among community mental health staff in guangzhou, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:231. 10.1186/s12888-014-0231-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kassam A, Glozier N, Leese M, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Development and responsiveness of a scale to measure clinicians’ attitudes to people with mental illness (medical student version). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122(2):153–61. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans-Lacko S, Rose D, Little K, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the reported and intended behaviour scale (RIBS): a stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2011;20(3):263–71. 10.1017/S2045796011000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J, Li J, Clement JGS, Ma ZY, Guo YB, et al. Study on the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the clinician Mental Illness Attitude Scale among community mental health workers. J Clin Psychol Med. 2014;24(4):227–9. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qiu Z. Study on the empathy status for higher vocational nursing students in Hunan Province. (Master), Sun Yat-sen University, Guang Zhou; 2010.

- 59.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Cohen MJM, Gonnella JS, Erdmann JB, Veloski J, Magee M. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61(2):349–65. 10.1177/00131640121971158. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsiao CY, Tsai YF, Kao YC. Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Profession Students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20(10):866–73. 10.1111/jpm.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duricki D, Soleman S, Moon L. Analysis of longitudinal data from animals with missing values using SPSS. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(6):1112–29. 10.1038/nprot.2016.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sideras S, McKenzie G, Noone J, Dieckmann N, Allen TL. Impact of a simulation on nursing students’ attitudes toward schizophrenia. Clin Simul Nurs. 2015;11(2):134–41. 10.1016/j.ecns.2014.11.005. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffiths KM, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, Reid R. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):161–75. 10.1002/wps.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aslan EA, Batmaz S. Does the clerkship/internship in psychiatry affect medical students’ level of knowledge about schizophrenia, attitudes, and beliefs toward schizophrenia and other mental disorders? PsyCh J. 2022;11(4):571–9. 10.1002/pchj.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharif LSM. Development and preliminary evaluation of a media-based health education intervention to reduce mental disorder-related stigma among nursing students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. King’s colllege London, University of London, London: Doctor of Philosophy; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. SAGE Publications, Incorporated. 2001. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA48328866

- 67.Magliano L. Bringing psychology students closer to people with schizophrenia at pandemic time: a study of a distance Anti-stigma intervention with in-presence opportunistic control group. J Psychosocial Rehabilitation Mental Health. 2022. 10.1007/s40737-022-00308-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asik E, Albayrak S. The effect of stigmatization education on the social distancing of nursing students toward patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2022;40:132–6. 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong P, Arat G, Ambrose MR, Qiuyuan KX, Borschel M. Evaluation of a mental health course for stigma reduction: a pilot study. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1). 10.1080/23311908.2019.1595877.

- 70.Román-Sánchez D, Paramio-Cuevas JC, Paloma-Castro O, Palazón-Fernández JL, Lepiani-Díaz I, de la Fuente Rodríguez JM, López-Millán MR. Empathy, burnout, and attitudes towards mental illness among Spanish mental health nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2). 10.3390/ijerph19020692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]