Abstract

Despite increasing demand for chiral fluorinated organic molecules, enantioselective C–H fluorination remains among the most challenging and sought-after transformations in organic synthesis. Furthermore, utilizing nucleophilic sources of fluorine is especially desirable for 18F-radiolabelling. To date, methods for enantioselective nucleophilic fluorination of inert C(sp3)–H bonds remain unknown. Herein, we report our design and development of a Pd-based catalytic system bearing bifunctional MPASA ligands which enabled highly regio- and enantioselective nucleophilic β-C(sp3)–H fluorination of synthetically important amides and lactams, commonly present in medicinal targets. The enantioenriched fluorinated products can be rapidly converted to corresponding chiral amines and ketones which are building blocks for a wide range of bioactive scaffolds. Mechanistic studies suggest that the C–F bond formation proceeds via outer-sphere reductive elimination with direct incorporation of fluoride, which was applied to late-stage 18F-radiolabelling of pharmaceutical derivatives using [18F]KF.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction:

Chiral fluorinated molecules have rapidly emerged as key targets for pharmaceuticals.1–3 In 2019, 41% of new FDA-approved chemical entities contained fluorine,4 and over 50 new small molecule fluoropharmaceuticals have been approved since then.5 While many catalytic methods for fluorination rely on electrophilic fluorine sources, the potential to utilize fluoride salts as inexpensive, stable, and more sustainable reagents has attracted significant interest.6–10 The need for this approach becomes more apparent in the context of diagnostic medicine via positron emission tomography (PET) imaging11 which requires rapid ways to introduce 18F radiotracers, most accessible as [18F]fluoride, at a late stage due to their relatively short half-life (τ1/2 = 109.7 min).12–14 Accordingly, a range of nucleophilic fluorination methods using electrochemistry,15 photocatalysis,16,17 transition metal catalysis18 such as aromatic cross-coupling,19,20 as well as strained ring opening,21 and functionalisation of double bonds,22–24 have been reported. However, these methods rely on installation or loss of functional groups – a structural alteration which in itself could exacerbate compound bioactivity (Fig 1A). The direct nucleophilic fluorination of C–H bonds would provide a more efficient route towards fluorinated products, but the development of such methodology remains nascent.10,25 Especially, enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluorination could enable expedient access to highly desired chiral fluorinated motifs.

Fig. 1. Catalytic C(sp3)–H fluorination strategies.

(A) Approaches to catalytic C(sp3)–F bond formation. (B) Limitations of catalytic nucleophilic and stereoselective C(sp3)–H fluorination. (C) Amide-derived scaffolds in drug discovery. (D) Enantioselective nucleophilic C(sp3)–H (radio)fluorination.

Notable advances in nucleophilic fluorination of C(sp2)–H bonds include recent reports employing organic photoredox catalysis26 or combining powerful directing groups with Cu catalysis.27 Key challenges hindering the development of transition metal catalysed nucleophilic C(sp3)–H fluorination are the low nucleophilicity of the poorly polarizable fluoride anion,7 the inertness of C(sp3)–H bonds, and the high energy barrier to C–F reductive elimination, which typically requires the use of electrophilic fluorinating agents to access high-valent transition metal species.28 Because of these challenges, Pd-catalysed C(sp3)–H nucleophilic fluorination has for a long time remained limited to benzylic29,30 and allylic31 C(sp3)–H bonds (Fig. 1B). Radical approaches32 for nucleophilic fluorination of alkanes,33 benzylic,30,34 and tertiary35,36 C(sp3)–H bonds using nucleophilic fluoride have also been reported. While we were finalizing this manuscript, the van Gemmeren group reported racemic β-C(sp3)–H fluorination of carboxylic acids mediated by mono protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands.37 Most notably, enantioselective nucleophilic C(sp3)–H fluorination has not been realized to date, although our lab has previously reported a strategy for enantioselective benzylic C–H fluorination using an electrophilic fluorine source38 and diastereoselective substrate-controlled electrophilic fluorination.39,40 Herein, we report ligand-enabled Pd-catalysed enantioselective β-C(sp3)–H (radio)fluorination of weakly binding native amides and lactams, frequently present in drug molecules and their precursors (Fig. 1C), with nucleophilic fluorine sources via an outer-sphere mechanism. This reaction provides rapid access to chiral β-fluorinated building blocks, highly challenging to access by other synthetic methods. The relatively short reaction time and the incorporation of nucleophilic fluoride renders this reaction applicable to 18F-radiolabelling using conveniently accessible [18F]KF9,13 (Fig. 1D). Notably, the desymmetrising fluorination of primary C(sp3)–H bonds also enables expedient access to fluorinated molecules with chiral centres bearing methyl groups, highly valuable in drug discovery due to the magic methyl effect.41 This methodology provides a platform for the asymmetric synthesis of α-carbonyl stereocentres from isobutyric acid – the fundamental and versatile building block for producing chiral methyl moieties in nature, as exemplified by the Roche ester.42

Results

Reaction development:

We envisioned that nucleophilic fluorination of the weakly coordinating tertiary amide substrates could be accomplished under Pd catalysis by combining a fluoride source with a suitable oxidant for accessing Pd(IV).43 Starting with 4-methylcarboxypiperidine isobutyramide as a model substrate and employing Pd(OPiv)2 as the catalyst, we surveyed a range of by-standing oxidants and fluoride sources (Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Selectfluor and its derivatives stood out among the oxidants, showing higher reactivity than NFSI, iodonium and fluoropyridinium salts, BQ, oxone, TBHP, and oxygen. We were delighted to observe the desired fluorination product could be obtained in 15% and 14% yields with CsF and CuF2, however, other fluoride salts provided less than 10% yield of the desired product. AgF, previously shown to be an effective nucleophilic fluorine source,24,29,33 was identified as the most optimal in combination with Selectfluor, affording the desired fluorination product in 50% yield. Water had a highly detrimental effect on reactivity, and we observed improvement in yield to 67% upon addition of a drying agent (MgSO4) and minimizing the amount of residual moisture in HFIP (Supplementary Table 2). Notably, our racemic fluorination protocol did not require external ligands and gave the highest yield at a mild temperature of 45 °C.

With the optimal conditions established, the scope of this racemic β-C–H fluorination was explored (Supplementary Table 6). Lactams as well as a wide range of amides bearing α-H (1a-1v) reacted in moderate to good yields, including functionalised piperidine, pyrrolidine, morpholine, and azepane derived amides with a range of side chains, such as alkyl, benzyl, fluoro, OMe, and NPhth substituents. Notably, the reaction was highly selective for monofluorination owing to stereoelectronic deactivation by the CH2F group disfavouring secondary C–H cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 33). Difluorination could be achieved via debromofluorination of brominated derivative (1w). Fluorination of fluoxetine derivative (1x) was also demonstrated in good yield.

Ligand design and development:

Upon successful development of the racemic fluorination protocol, we set out to explore the possibility of rendering this transformation enantioselective. Utilizing the weakly coordinating native amide carbonyl group to direct enantioselective C(sp3)–H functionalisation presents a formidable challenge in transition metal catalysis, with only a single report of arylation published to date.44 Notably, stereoselective C(sp3)–H heterofunctionalisation of tertiary amides remains unknown. We chose amide 1b as the model substrate for fluorinative C(sp3)–H desymmetrisation of the gem-dimethyl group which could unlock access to uniquely functionalised enantioenriched scaffolds.41 We envisioned this could be accomplished using a chiral bidentate ligand, capable of promoting C–H cleavage and creating a favourable stereoelectronic environment in the resultant palladacycle for nucleophilic fluoride incorporation.

Initial screening of Pd catalyst showed that the absence of concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD)-active base such as acetate or pivalate is crucial for enantioselectivity, with [Pd(PhCN)2]Cl2 identified as optimal (Supplementary Table 7). A range of chiral bidentate ligands were selected and screened under the reaction condition to match the monodentate coordination of amide substrates (Fig. 2). APAQ (L1) and APAO (L2) ligands, developed by our group for enantioselective methylene and primary β-C(sp3)–H arylation,45 showed low reactivity and ee. The most promising result was obtained with MPAA ligands (L4-L14), where 68% ee and 33% yield was observed with N-Ac-isoleucine (L14). Unfortunately, modifying the side chain of the amino acid or the identity of the N-protecting group (Supplementary Table 8) did not result in any further improvement of enantioselectivity. Realizing this limitation prompted us to evaluate a secondary functional element in our ligand design in the hope of enhancing stereoselectivity by relaying stereocontrol from the ligand backbone through dispersion interactions with the forming palladacycle.46,47 Hydroxamic acid-derived (MPAHA) ligand led to reduced ee (L15), while introducing an aryl on the nitrogen in MPAAn-type anilamides (L16, L17), which we previously utilized in desymmetrisation of thioethers,46 did not improve stereoselectivity compared to L14. A breakthrough was achieved when the carboxylic acid group of the ligand was modified into a tosylamide group, achieving 94% ee and 68% yield with the isoleucine derivative (L18). Increasing the ligand bite angle from 5- to 6-membered coordination led to reduced reactivity and enantioselectivity (L19, L20). Optimization of this mono-protected amino sulfonamide (MPASA) ligand involved changing the amino acid-derived backbone (L21-L27), with valine derivative L25 giving slightly improved ee and similar yield compared to L18. Curiously, introducing electron-withdrawing groups on the sulfonamide arene (L18-L31) significantly increased the reaction rate, leading to 86% yield in the case of the cyano-substituent, albeit with slightly reduced ee (L31). Switching the backbone to valine resulted in the most optimal ligand L34, furnishing the product in 81% yield and 95% ee. Notably, the reaction tolerated low Pd loadings, achieving 52% yield and 93% ee with 1 mol% Pd and 2.5 mol% ligand (Supplementary Table 9).

Fig. 2. Ligand optimization of the enantioselective C(sp3)–H nucleophilic fluorination.

Reaction conditions: 1b (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), [Pd(PhCN)2]Cl2 (5 mol%), Ligand (12 mol%), Selectfluor (1.2 equiv.), AgF (3 equiv.), 3Å molecular sieves (2.5% m/v), HFIP (0.5 mL), 45 °C, under air, 20 h. Gas Chromatography (GC) yields are reported with perfluorobiphenyl as the internal standard. Highlighted yields were verified by 1H NMR using CH2Br2 as standard. aReaction conditions: [Pd(PhCN)2]Cl2 (10 mol%), Ligand (25 mol%), Selectfluor (1.2 equiv.), AgF (2 equiv.), anhydrous MgSO4 (2 equiv.), HFIP (0.5 mL), 45 °C, under air, 12 h.

Scope of enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluorination:

With optimal conditions in hand, the scope of this desymmetrisation was investigated (Fig. 3). A range of piperidine isobutyramides bearing aryl (2a-2ab), benzyl (2ad), ketone (2ae, 2aj), methyleneoxy-(2ac), spirochromane (2aj) or amino (2af) substituents on the 4-position reacted in high yields and enantioselectivities. Di- (2h) and monobenzyl (2ai) derivatives were fully compatible, providing potential access to secondary and primary amides via debenzylation. The azepane derivative (2ag) also worked well, while anilamide (2i) and bridged (2ah) derivatives reacted in modest yield but maintained over 90% ee. Piperazine substrates were also tolerated, with benzyloxycarbonyl (2am) and tosyl (2al) protection of the distal nitrogen identified as optimal. Quaternary substrates were limited to 6-membered cyclic lactams (2ak, 2u) and remarkably gave up to 98% ee. Fragments of medicinally-relevant compounds were also tolerated, including maprotiline (2ao), risperidone (2ap), and desloratadine (2aq) derivatives, and a fentanyl analogue precursor (2an). It is noteworthy that this method tolerates the presence of heterocycles such as benzisoxazole (2ap) and pyridine (2aq), which are known to be particularly problematic in Pd-catalysed C–H activation when using weakly coordinating native directing groups.

Fig. 3. Scope of ligand-enabled desymmetrisation via nucleophilic C(sp3)–H fluorination.

Reaction conditions: substrate (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Selectfluor (1.2 equiv.), Pd(PhCN)2Cl2 (5 mol%), L34 (12 mol%), AgF (3 equiv.), 3Å molecular sieves (2.5% m/v), HFIP (0.5 mL), 45 °C, under air, 16 h. Isolated yields are reported. The absolute configuration of 2b was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis, other compounds were assigned by analogy to 2b. Absolute stereochemistry for the lactams 2ak and 2u was not determined. aee was determined by conversion to 5.

Kinetic resolution was also investigated (Fig. 4) and gave synthetically useful yields and up to 95% ee with morpholine or piperidine-derived substrates bearing benzyl (2r) or alkyl side chains of various lengths (2l, 2ar) and bulkiness (2n), as well as nitrogen (2p) or oxygen (2as) heteroatoms. Lactams of 6 (2au-2ax), 7 (2at), 8 (2ay), and 9-membered (2az) ring sizes all reacted with good yields and enantioselectivities, providing convenient access to chiral 3-fluoromethyl N-heterocycles from piperidine to azonane upon reduction.

Fig. 4. Scope of kinetic resolution via ligand-enabled nucleophilic C(sp3)–H fluorination.

Reaction conditions: substrate (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Selectfluor (1.2 equiv.), Pd(PhCN)2Cl2 (5 mol%), L34 (12 mol%), AgF (3 equiv.), 3Å molecular sieves (2.5% m/v), HFIP (0.5 mL), 45 °C, under air, 16 h. Isolated yields are reported. The absolute configuration of compounds was assigned by analogy to 2b. Absolute stereochemistry for the lactams 2at-2az was not determined. aCalculated conversion, C = eeSM/(eeSM+eePR). bSelectivity factor, s = ln[(1 – C)(1 – eeSM)]/ln[(1 – C)(1 + eeSM)]. cUsing L28 for 12h.

Reaction scale-up:

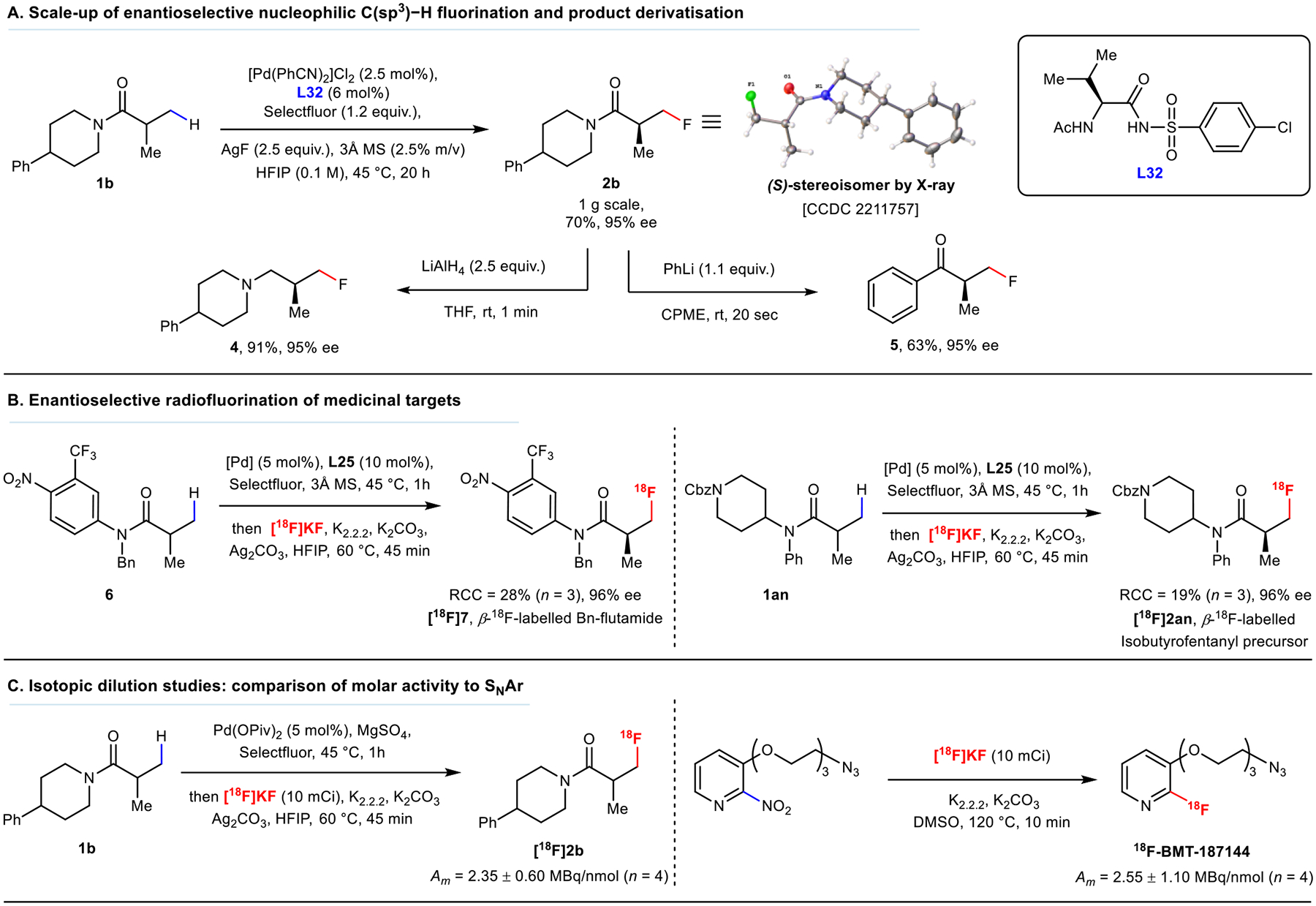

The robustness of the developed protocol was demonstrated in a 1-gram scale reaction with 2.5% loading of Pd catalyst, which provided a 70% isolated yield and 95% ee (Fig. 5A). This product was subsequently diversified by conversion of the amide to the corresponding tertiary amine (4) and phenyl ketone (5) in good yields and without any loss of ee, illustrating the utility of this method for accessing chiral fluorinated amines and ketones. Notably, the fast reaction times (under 1 min) render this approach applicable to rapidly accessing chiral 18F-labeled derivatives from amides for PET studies.

Fig. 5. Applications of enantioselective fluorination and radiochemistry studies.

(A) Scale-up of enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluorination and derivatisation of chiral fluorinated product. (B) Enantioselective 18F-radiolabelling of flutamide and fentanyl analogue precursors. 10 mCi of [18F]KF was used. Enantioselectivities determined under the same conditions using cold KF as the fluoride source. (C) Isotopic dilution studies. RCC was measured via radioHPLC. Enantioselectivities determined using cold KF. See Supplementary Methods (Radiochemistry studies) for full description of reaction set-up and conditions.

C(sp3)–H radiofluorination:

In collaboration with Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), we were interested in showing the utility of our methodology for enantioselective radiolabelling. A major challenge was reducing the reaction time down to less than 1 hour to match the short half-life of the 18F-isotope. In addition, utilizing [18F]AgF synthesized via the reported approaches48 did not lead to any 18F incorporation. Fortunately, we discovered that a combination of Ag2CO3 and no-carrier-added [18F]KF was effective for C–H fluorination (Supplementary Table 12). Increasing the reaction temperature to 60 °C and pre-stirring the reaction mixture for 1h (Supplementary Table 5) before the addition of [18F]KF accelerated fluoride incorporation, affording up to 51% radiochemical conversion (RCC) using substrate 1b under racemic conditions. The requirement of the presence of Ag+ for productive (radio)fluorination suggests coordinative involvement of Ag+ in fluoride delivery, which was supported by computational studies (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Fig. 34). Radiochemical conversion of the model substrate under the stereoselective protocol was most optimal using the nitro-derivative L33, achieving up to 52% RCC (Supplementary Table 13). Radiolabelling of 1au via kinetic resolution was also demonstrated with 8.5% RCC, which is sufficient for practical applications. The utility of the protocol was demonstrated by radiolabelling of Bn-protected flutamide 6 and Cbz-protected isobutyrofentanyl precursor 1an (Fig. 5B) for which L25 was most optimal, affording products in 96% ee and 28% and 19% RCC, respectively.

Fig. 6. Mechanistic and computational studies.

(A) Mechanistic studies. See Supplementary Methods (Mechanistic Experiments) for experimental details. (B) Proposed catalytic cycle. (C), (D) Computational studies. Reported ΔΔG≠ values are conformation-weighed. TS stands for transition state. See Supplementary Methods (Computational Data and Analysis) for computational details.

Investigation of isotopic dilution:

Given that both electrophilic and nucleophilic fluorine reagents are present in the reaction, it is vital to investigate the origin of fluorine incorporation for 18F-radiolabelling application. Isotopic dilution studies were conducted to corroborate the nature of the fluorine source in these reactions (Fig. 5C). We compared the molar activity of [18F]2b produced in the reaction with a known high molar activity SNAr 18F-labelling procedure towards 18F-BMT-18714449 using the same batch and amount of [18F]KF (see Radioisotope dilution studies in Supplementary Methods for details). Similar molar activity was observed, further suggesting that the nucleophilic fluoride rather than Selectfluor was the source of fluorine incorporated into the product within these reactions.

Mechanistic studies:

Previous reports of Pd-catalysed C(sp3)–F bond formation have proposed direct inner-sphere C–F reductive elimination (RE) from an organo-Pd(IV) fluoride species.29 Outer-sphere (SN2 type) RE with fluoride has also been considered50 and observed in olefin24 and allylic51 nucleophilic fluorination. Our lab has previously observed a switch between inner- and outer-sphere RE mechanisms depending on whether the Pd is neutral or cationic in the context of competing electrophilic fluorination and acetoxylation.38 Given that no product formation occurred in the absence of a nucleophilic fluoride source regardless of the presence of the Ag cation (Fig. 6A1), we hypothesized that the reaction may occur via outer-sphere RE, with Selectfluor serving only as an oxidant rather than as a fluorine source. This hypothesis was further supported by the absence of detectable 19F dilution observed in 18F-incorporation from the [18F]fluoride source shown in the measurements of initial molar activity we did in collaboration with BMS. In contrast, 18F-incorporation via inner sphere RE would require fast fluoride exchange on Pd(IV), resulting in at least 50% dilution from the outset of the reaction. Notably, performing the measurement at longer reaction times showed a decrease in decay-corrected average molar activity of [18F]2b, in line with the expected gradual dilution as cold fluoride originating from Selectfluor is released into the reaction mixture upon catalyst regeneration (Supplementary Fig. 22). We did not see any formation of 2b in the reaction with methacrylamide 1y, suggesting that the reaction did not proceed via dehydrogenation followed by a Michael-type addition of fluoride.

The absence of deuterium incorporation in starting material recovered at partial conversion (Fig. 6A2) and high primary H/D kinetic isotope effect (KIE) at the β-position measured in parallel experiments (Fig. 6A3) showed the C–H activation step to be both irreversible and turnover-limiting, which led us to conclude it was also stereoselectivity determining. Based on literature precedent for C–H activation reactions involving strong oxidants like Selectfluor,43 the reaction is proposed to proceed via a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) cycle (Fig. 6B). After the formation of a Pd-ligand complex, substrate coordination is followed by enantiodetermining C–H cleavage. Oxidation of the resulting palladacycle with Selectfluor results in a Pd(IV) species, which undergoes outer-sphere reductive elimination with silver fluoride to afford the desired product.

Computational studies:

Density functional theory (DFT) modelling was used to analyse the enantiodetermining C–H transition state (TS). In line with the stereoinduction relay hypothesis employed in our ligand design,46,47 we identified the sulfonamide functional group as the key stereodefining element positioned over the forming palladacycle in the lowest energy TS (Fig. 6C), engaging in favourable dispersion interactions with the Me group which occupies the pseudo-axial position to avoid A1,3 steric clash with the N-methyl group. The methyl group in the amino acid-derived chiral backbone occupies a pseudo-axial position, enforcing the anti-positioning of the stereodefining sulfonamide group which relays stereochemical information from the ligand backbone onto the substrate by maximizing the aryl-methyl dispersion interactions (Supplementary Fig. 32). This model is well aligned with the large effect of the presence or absence of the sulfonamide arene on enantioselectivity compared to MPAA ligands, and with its minimal response to the amino acid backbone size in the MPASA ligands (Fig. 2). Predicted absolute stereochemistry was in agreement with the product structure obtained by single crystal X-ray crystallography (Fig. 5A), and calculated enantioselectivities closely matched the experimental values, supporting the proposed stereomodel.

DFT modelling of the reductive elimination (RE) step identified Ag-mediated fluoride delivery via outer-sphere heterobimetallic TS as the lowest energy pathway, favoured by 5.21 kcal/mol compared to the inner-sphere RE TS (Fig. 6D). Coordination with the N-Ac group of the ligand was found to position silver for optimal outer-sphere fluoride delivery. Notably, coordination with Ag was shown to lower the energies of heterobimetallic TS by over 14 kcal/mol compared to RE in the absence of Ag (Supplementary Fig. 34), which is in line with the observed requirement of the presence of Ag salt for both reactivity (Supplementary Table 1) and 18F-incorporation (Supplementary Table 12).

Conclusions:

In conclusion, we have realized enantioselective nucleophilic fluorination and radiolabelling of unactivated aliphatic C–H bonds enabled by the design of a bidentate bifunctional ligand and a bystanding oxidant. A wide variety of native amides and lactams were compatible with this protocol, rendering this enantioselective reaction a valuable method for the synthesis of chiral fluorinated building blocks. Nucleophilic fluorine incorporation via an outer-sphere reductive elimination was supported by mechanistic studies, and ligand-induced stereoselectivity rationalised by DFT modelling. Several drug analogues were efficiently radiolabelled stereoselectively using [18F]KF as a convenient source of fluorine.

Methods

General procedure for the racemic C(sp3–H) fluorination:

To a dry 10 mL reaction tube were added Pd(OPiv)2 (2.9 mg, 10 mol%), Selectfluor (42.6 mg, 1.2 equiv.), anhydrous MgSO4 (24.0 mg, 2.0 equiv.), and the substrate (0.1 mmol), followed by dry dry AgF (25.4 mg, 2.0 equiv.) and an egg-shaped PTFE stir bar. 1.0 mL of dry HFIP was added next, the tube was sealed with a cap, sonicated for 10 sec with swirling and stirred at 45 °C for the indicated time (500 rpm). The reaction was stopped by quenching with 2 mL Et2O (mixing the solvents triggered precipitation) and filtered through a short pad of diatomaceous earth (Celite™), washing with Et2O (2 mL) and acetone (2 mL). The solvent was evaporated and mixture analyzed. The crude mixture was purified by pTLC (acetone/dichloromethane) or column chromatography to afford the fluorinated product.

General procedure for the enantioselective C(sp3–H) fluorination:

To a dry 10 mL reaction tube were added [Pd(PhCN)2]Cl2 (1.0 mg, 5 mol%), ligand (12 mol%), Selectfluor (21.3 mg, 1.2 equiv.), fresh activated Linde 3Å molecular sieves (12.5 mg, 600 mesh powder), and the substrate (0.05 mmol), followed by dry AgF (19.0 mg, 3.0 equiv.) and an egg-shaped PTFE stir bar. 0.5 mL of dry HFIP was added next, the tube was sealed with a cap, sonicated for 10 sec with swirling and stirred at 45 °C for indicated time (500 rpm). The reaction was stopped by quenching with 2 mL Et2O (mixing the solvents triggered precipitation) and filtered through a short pad of diatomaceous earth (Celite™), washing with Et2O (2 mL) and acetone (2 mL). The solvent was evaporated and mixture analyzed. The crude mixture was purified by pTLC (acetone/dichloromethane) or column chromatography to afford the fluorinated product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge The Scripps Research Institute, the NIH (NIGMS, 2R01GM084019), and Bristol Myers Squibb for financial support. We thank Dr. Daniel Strassfeld and Yi-Hao Li for proofreading and help with editing the manuscript. We thank Tao Sheng and Yi-Hao Li for help with spectral data analysis. We thank J. Lee, B. Sanchez, Q. N. Wong, J. Smith, and J. Chen of the Scripps Research Automated Synthesis Facility for their assistance with SFC and LC-MS analysis and for help with compound purification. We thank M. Gembicky, J. Bailey, and the University of California San Diego Crystallography Facility for X-ray crystallographic analysis and the Scripps Research High Performance Computing facility for computational resources.

Footnotes

Competing interests: N. C., D. Q. P., Y. O., and J.-Q.Y. are inventors on a patent application related to this work (USSN Patent Application 63/797,339) filed by The Scripps Research Institute. D. J. D, K.-S. Y., and J. X. Q. are employees of Bristol Myers Squibb. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Data availability:

Crystallographic data for compound (S)-2b are available in the Supplementary Information files and from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition number CCDC 2211757. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Cartesian coordinates (Å) for the computed structures are provided in the xyz file. All other data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References:

- 1.Müller K, Faeh C & Diederich F Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: Looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S & Gouverneur V Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 37, 320–330 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillis EP, Eastman KJ, Hill MD, Donnelly DJ & Meanwell NA Applications of Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem 58, 8315–8359 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue M, Sumii Y & Shibata N Contribution of Organofluorine Compounds to Pharmaceuticals. ACS Omega 5, 10633–10640 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q et al. FDA approved fluorine-containing drugs in 2023. Chinese Chemical Letters 109780 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton R et al. Contemporary synthetic strategies in organofluorine chemistry. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 1, (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron S Where Does the Fluorine Come From? A Review on the Challenges Associated with the Synthesis of Organofluorine Compounds. Org. Process Res. Dev 24, 470–480 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel C et al. Fluorochemicals from fluorspar via a phosphate-enabled mechanochemical process that bypasses HF. Science 381, 302–306 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khandelwal M, Pemawat G & Kanwar Khangarot R Recent Developments in Nucleophilic Fluorination with Potassium Fluoride (KF): A Review. Asian J. Org. Chem 11, 1–17 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibler INM, Gandhi SS, Tekle-Smith MA & Doyle AG Strategies for Nucleophilic C(sp3)-(Radio)Fluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 145, 9928–9950 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ametamey SM, Honer M & Schubiger PA Molecular imaging with PET. Chem. Rev 108, 1501–1516 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halder R & Ritter T 18F-Fluorination: Challenge and Opportunity for Organic Chemists. Journal of Organic Chemistry 86, 13873–13884 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright JS, Sharninghausen LS, Lapsys A, Sanford MS & Scott PJH C–H Labeling with [18F]Fluoride: An Emerging Methodology in Radiochemistry. ACS Cent. Sci 10, 1674–1688 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luu TG & Kim H-K Recent progress on radiofluorination using metals: strategies for generation of C–18F bonds. Organic Chemistry Frontiers 10, 5746–5781 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B, Xu M, Feng P & Xu S Electrochemical Construction of C−F Bonds: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. European J. Org. Chem 27, (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bui TT, Hong WP & Kim HK Recent Advances in Visible Light-mediated Fluorination. J. Fluor. Chem 247, 109794 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bui TT & Kim HK Recent Advances in Photo-mediated Radiofluorination. Chem. Asian J 16, 2155–2167 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollingworth C & Gouverneur V Transition metal catalysis and nucleophilic fluorination. Chemical Communications 48, 2929–2942 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell MG & Ritter T Modern carbon-fluorine bond forming reactions for aryl fluoride synthesis. Chem. Rev 115, 612–633 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson DA et al. Formation of ArF from LPdAr(F): Catalytic Conversion of Aryl Triflates to Aryl Fluorides. Science 325, 1661–1664 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pupo G et al. Asymmetric nucleophilic fluorination under hydrogen bonding phase-transfer catalysis. Science 360, 638–642 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banik SM, Medley JW & Jacobsen EN Catalytic, asymmetric difluorination of alkenes to generate difluoromethylated stereocenters. Science 353, 51–54 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molnár IG & Gilmour R Catalytic Difluorination of Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 5004–5007 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu T, Yin G & Liu G Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 16354–16355 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szpera R, Moseley DFJ, Smith LB, Sterling AJ & Gouverneur V The Fluorination of C−H Bonds: Developments and Perspectives. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 58, 14824–14848 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W et al. Direct arene C–H fluorination with 18F− via organic photoredox catalysis. Science 364, 1170–1174 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truong T, Klimovica K & Daugulis O Copper-catalyzed, directing group-assisted fluorination of arene and heteroarene C–H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 9342–9345 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furuya T et al. Mechanism of C–F reductive elimination from palladium(IV) fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 3793–3807 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMurtrey KB, Racowski JM & Sanford MS Pd-catalyzed C–H fluorination with nucleophilic fluoride. Org. Lett 14, 4094–4097 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkins AP, Dean AC & Lennox AJJ Benzylic C(sp3)–H fluorination. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 20, 1527–1547 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun M & Doyle AG Palladium-Catalyzed Allylic C–H Fluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 12990–12993 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatalova-Sazepin C, Hemelaere R, Paquin JF & Sammis GM Recent Advances in Radical Fluorination. Synthesis (Germany) 47, 2554–2569 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W et al. Oxidative Aliphatic C–H Fluorination with Fluoride Ion Catalyzed by a Manganese Porphyrin. Science 337, 1322–1325 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W & Groves JT Manganese-catalyzed oxidative benzylic C–H fluorination by fluoride ions. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 52, 6024–6027 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bafaluy D, Georgieva Z & Muñiz K Iodine Catalysis for C(sp3)–H Fluorination with a Nucleophilic Fluorine Source. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 59, 14241–14245 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leibler INM, Tekle-Smith MA & Doyle AG A general strategy for C(sp3)–H functionalization with nucleophiles using methyl radical as a hydrogen atom abstractor. Nat. Commun 12, 1–10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mal S, Jurk F, Hiesinger K & van Gemmeren M Pd-catalysed direct β-C(sp3)–H fluorination of aliphatic carboxylic acids. Nature Synthesis, 3, 1292–1298 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park H, Verma P, Hong K & Yu JQ Controlling Pd(IV) reductive elimination pathways enables Pd(II)-catalysed enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluorination. Nat. Chem 10, 755–762 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu RY et al. Ligand-Enabled Stereoselective β-C(sp3)–H Fluorination: Synthesis of Unnatural Enantiopure anti-β-Fluoro-α-amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 7067–7070 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q, Yin XS, Chen K, Zhang SQ & Shi BF Stereoselective Synthesis of Chiral β-Fluoro α-Amino Acids via Pd(II)-Catalyzed Fluorination of Unactivated Methylene C(sp3)–H Bonds: Scope and Mechanistic Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 8219–8226 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagib DA Catalytic Desymmetrization by C−H Functionalization as a Solution to the Chiral Methyl Problem. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 56, 7354–7356 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodhue CT & Schaeffer JR Preparation of L (+)-β-hydroxyisobutyric acid by bacterial oxidation of isobutyric acid. Biotechnol. Bioeng 13, 203–214 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engle KM, Mei TS, Wang X & Yu JQ Bystanding F+ oxidants enable selective reductive elimination from high-valent metal centers in catalysis. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 50, 1478–1491 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan C, Wang X & Jiao L Ligand-Enabled Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective β-C(sp3)−H Arylation of Aliphatic Tertiary Amides. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 62, (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saint-Denis TG, Zhu R-Y, Chen G, Wu Q-F & Yu J-Q Enantioselective C(sp3)‒H bond activation by chiral transition metal catalysts. Science 359, eaao4798 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saint-Denis TG et al. Mechanistic Study of Enantioselective Pd-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Activation of Thioethers Involving Two Distinct Stereomodels. ACS Catalysis 11, 9738–9753 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng GJ et al. A Combined IM-MS/DFT Study on [Pd(MPAA)]-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Activation: Relay of Chirality through a Rigid Framework. Chemistry - A European Journal 21, 11180–11188 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson S et al. Synthesis of [18F]-γ-Fluoro-α,β-unsaturated Esters and Ketones via Vinylogous 18F-Fluorination of α-Diazoacetates with [18F]AgF. Synthesis (Germany) 51, 4401–4407 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donnelly DJ et al. Synthesis and biologic evaluation of a novel 18F-labeled adnectin as a PET radioligand for imaging PD-L1 expression. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 59, 529–535 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brandt JR, Lee E, Boursalian GB & Ritter T Mechanism of electrophilic fluorination with Pd(IV): Fluoride capture and subsequent oxidative fluoride transfer. Chem. Sci 5, 169–179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katcher MH, Norrby PO & Doyle AG Mechanistic investigations of palladium-catalyzed allylic fluorination. Organometallics 33, 2121–2133 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Crystallographic data for compound (S)-2b are available in the Supplementary Information files and from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition number CCDC 2211757. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Cartesian coordinates (Å) for the computed structures are provided in the xyz file. All other data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.