Abstract

Although genetic risk in coronary artery disease (CAD) is linked to changes in gene expression, recent discoveries have revealed a major role for A-to-I RNA editing in CAD. ADAR1 edits immunogenic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), preventing activation of the dsRNA sensor MDA5 (IFIH1) and downstream interferon-stimulated gene signaling. Using human plaque analysis and human coronary artery smooth muscle cells (SMCs), here, we show that SMCs uniquely require RNA editing and that MDA5 activation regulates SMC phenotype. In a conditional SMC-specific Adar deletion mouse model on an atherosclerosis-prone background, combined with Ifih1 deletion and single-cell RNA sequencing, we demonstrate that ADAR1 preserves vascular integrity and limits atherosclerosis and calcification by suppressing MDA5 activation. Analysis of the Athero-Express carotid endarterectomy cohort further shows that interferon-stimulated gene expression correlates with SMC modulation, plaque instability and calcification. These findings reveal a fundamental mechanism of CAD, where cell type and context-specific RNA editing modulates genetic risk and vascular disease progression.

Subject terms: Transcriptomics, Epigenomics

Weldy et al. show that smooth muscle expression of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 regulates activation of the double-stranded RNA sensor MDA5 in a novel mechanism of atherosclerosis.

Main

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the leading global cause of death1. Although genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have uncovered hundreds of CAD-linked loci2–5, translation into therapies beyond lipid lowering remains limited. Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analyses have linked variants to transcriptional regulation6,7, but post-transcriptional mechanisms (notably RNA editing) remain underexplored contributors to disease8–10.

A-to-I RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR enzymes, is an evolutionarily conserved process with widespread effects on RNA sequence, transcript function, RNA stability and immunogenicity8,11. We recently identified that common variants that reduce A-to-I RNA editing (editing QTLs (edQTLs)) increase CAD risk as well as other autoinflammatory disorders12. This suggests a causal role for genetically encoded RNA editing capacity in CAD, although the biological mechanisms remain undefined.

ADAR1 (encoded by ADAR) primarily edits double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in repetitive elements, preventing its recognition by innate immune sensors13. This contrasts with ADAR2 (ADARB1), which edits coding regions11,14. Notably, ADAR1 suppresses the cytosolic dsRNA sensor MDA5 (encoded by IFIH1; Fig. 1a)15–17, and in mice, loss of Adar is embryonically lethal due to MDA5-dependent activation of an interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) program16. In humans, rare loss-of-function variants in ADAR or gain-of-function variants in IFIH1 cause overlapping Mendelian interferonopathies (Aicardi–Goutières and Singleton–Merton syndromes) marked by early-onset vascular calcification18,19, linking the ADAR1–dsRNA–MDA5 axis to vascular disease.

Fig. 1. SMCs in atherosclerosis express immunogenic RNA and show evidence of ISG induction in phenotypic modulation.

a, Schematic of ADAR1 RNA editing of dsRNA. b, UMAP of scRNA-seq data from human carotid atherosclerotic plaques (Alsaigh et al.24); Endo, endothelial cells; Fibro, fibroblasts; NKT, natural killer T cells; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; DC, dendritic cells; Mac, macrophages. c, Module score of immunogenic RNA expression. d–f, Clustering of SMC subset (d) with a violin plot showing the SMC marker MYH11 (e) and FMC/CMC marker TNFRSF11B (f). g–i, Violin plots of the expression of ISGs ISG15 (g), IF135 (h) and IFI16 (i). j, Dot plot of the top ISGs within SMC clusters. k–n, Using a mouse comprehensive integrated dataset of lineage-traced SMCs (from Sharma et al.32), feature plots were generated of Myh11 (k) and Col2a1 (l) at 0 and 16 weeks of a high-fat diet and of Isg15 (l) and Ifit3 (m) in SMC phenotypic modulation.

Although prior studies have implicated ADAR1 in atherosclerosis through transcript-specific editing (for example, NEAT1 and CTSS)20,21, genetic and molecular data increasingly support a broader model in which ADAR1-mediated editing of immunogenic dsRNA controls MDA5 activation as a mechanism of atherogenesis (Fig. 1a). Supporting this hypothesis, loss-of-function variants in IFIH1 (MDA5) protect against CAD22, and the IFIH1 locus reaches genome-wide significance in CAD GWASs5.

Here, we investigate how ADAR1-mediated RNA editing in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) regulates MDA5 activation and atherosclerosis progression. Through human single-cell transcriptomics, in vitro modeling, conditional SMC-specific Adar-knockout (KO) mice with additional Ifih1 deletion and human plaque transcriptomics, we identify a smooth muscle-specific ADAR1–dsRNA–MDA5 axis as a key modulator of SMC state, inflammation, calcification and CAD risk. This work defines a mechanistic and therapeutic paradigm linking human genetics and vascular biology.

Results

Expression of immunogenic RNA within vascular SMCs in human atherosclerotic plaques

To understand which vascular cell types may be most reliant on RNA editing for immune tolerance, we began by generating a curated list of 629 high-confidence human transcripts predicted to form dsRNA structures requiring A-to-I editing based on our prior in vitro models23, along with human genetic edQTL analysis12 (Supplementary Table 1). We then analyzed publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from human carotid atherosclerotic plaques24. After clustering and cell-type annotation (Fig. 1b), we calculated a module ‘score’ for each cell based on the expression of the 629 immunogenic transcripts. This scoring revealed an enrichment of immunogenic RNA expression in SMCs relative to all other vascular, immune and stromal cell types (Fig. 1c).

SMC phenotypic modulation and ISG induction in atherosclerosis

In atherosclerosis, SMCs undergo a process of epigenetic reprogramming, termed ‘phenotypic modulation’25,26, where SMCs dedifferentiate, downregulate lineage marker expression and migrate into the atheroma. Numerous CAD risk genes mediate disease by regulating this phenotypic modulation27–31. Mature SMCs will undergo phenotypic modulation to a more ‘fibroblast-like’ fibromyocyte (FMC) and then into a calcification-promoting chondromyocyte (CMC)29 phenotype in the setting of disease.

To explore SMC phenotypic modulation, dsRNA sensing and ISG activation, we analyzed the SMC cluster within the carotid plaque scRNA-seq dataset24. Subclustering of SMCs identified four major transcriptional states (clusters 0–3) corresponding to stages of phenotypic transition. As expected, we observed downregulation of canonical contractile markers such as MYH11 in modulated clusters, particularly cluster 0 (Fig. 1d,e, cluster 2 versus 0, −2.92 log2 (fold change), adjusted P value of 1.98 × 10−290). Conversely, markers of FMC and CMC states, including TNFRSF11B, HAPLN1 and LUM, were upregulated (for example, TNFRSF11B; Fig. 1f, cluster 2 versus 0, 1.52 log2 (fold change), adjusted P value of 3.07 × 10−26), consistent with our prior report29. Importantly, differential gene expression analysis of these clusters revealed strong upregulation of ISGs in cluster 0, which marked the most modulated SMC population (for example, ISG15, IFI35 and IFI16; adjusted P values of 3.94 × 10−21, 2.60 × 10−27 and 2.63 × 10−64, respectively; Fig. 1g–j; for FindMarker results, see Supplementary Table 2). These results suggested that as SMCs undergo phenotypic transition, they activate a cell-intrinsic ISG response that may reflect sensing of dsRNA through MDA5.

To determine if this ISG induction is conserved in mouse models of atherosclerosis, we evaluated our previously published dataset of single-cell transcriptomic profiles of lineage-traced SMCs in hyperlipidemic models of atherosclerosis32. Mouse SMCs exhibited downregulation of Myh11 (Fig. 1k; −0.73 log2 (fold change), P < 2 × 10−16) and upregulation of Col2a1 (Fig. 1l; 3.29 log2 (fold change), P < 2 × 10−16), a marker of CMC formation. These changes coincided with the induction of key ISGs, including Isg15 and Ifit3 (Fig. 1m,n; for example, Isg15: 0.29 log2 (fold change), P < 2 × 10−16). These cells lie at the juncture between FMC and CMC formation, and expression was absent in mature SMCs before phenotypic modulation.

SMC ADAR1 and MDA5 expression in atherosclerosis in mice

Given the observed induction of ISGs during SMC modulation, we evaluated the expression of ADAR and IFIH1 in atherosclerosis. In the human carotid plaque dataset, neither ADAR nor IFIH1 showed significant differences in expression across the four major SMC subclusters (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). When examining broader cell-type-specific expression, IFIH1 was found to be somewhat enriched in endothelial cells and macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 1c), whereas ADAR expression was relatively uniform. In the mouse SMC lineage-traced dataset, Ifih1 expression increased twofold after 16 weeks of a high-fat diet (P < 2 × 10−16), whereas Adar showed a modest 1.26-fold increase (P = 2.2 × 10−7; Supplementary Fig. 1d–f). At the 16-week time point, Ifih1 was most highly expressed at the FMC/CMC transition state, overlapping with the ISG signature.

ADAR1 controls global RNA editing and ISG response in human coronary artery SMCs

To investigate the functional role of ADAR1 in human SMCs, we used a model of phenotypic modulation in primary human coronary artery SMCs (HCASMCs). Cells were transfected with short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting ADAR and/or IFIH1, serum starved to promote a contractile phenotype and stimulated with serum to induce transition. Bulk RNA-seq was used to assess transcriptomic consequences and MDA5 dependence (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

Extended Data Fig. 1. ADAR1 regulates RNA editing in human coronary SMCs and RNA editing requirement is dependent on cell context.

(a) Schematic of SMC phenotypic modulation in vitro assay. (b) Linear regression analysis of ADAR1 expression and global RNA editing frequency in primary human coronary artery SMCs (HCASMCs) following siRNA KD of ADAR. (c) Grouped bar chart of RNA editing frequency with cellular treatment of scramble, ADAR, and ADAR + IFIH1 (MDA5) siRNA. (d) Volcano plot of bulk RNAseq DE gene analysis comparing scramble vs ADAR siRNA in serum starved conditions, (e) volcano plot comparing scramble vs ADAR + IFIH1 siRNA in serum starved conditions, (f) volcano plot comparing scramble vs ADAR siRNA in serum fed conditions, and (g) volcano plot comparing scramble vs ADAR + IFIH1 siRNA in serum fed conditions. (h) Principal component analysis (PCA) of bulk RNAseq data of principal components 1 and 2 for each HCASMC treatment. Grouped bar chart of normalized RNAseq reads across HCASMC treatments for (i) ACTA2, (j) CNN1, (k) ISG15, (l) KLF4, (m) EGR1, and (n) ATF3. P-values represent simple linear regression (c) or (c, i-n) two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons post hoc analysis. N = 3 RNA seq libraries per condition.

Global A-to-I RNA editing was quantified by measuring guanosine at known editing sites as we have previously done12,33. Editing levels strongly correlated with ADAR expression (r2 = 0.9509, P < 0.0001; Extended Data Fig. 1b). Serum stimulation alone reduced total editing (Extended Data Fig. 1c), suggesting modulation to affect editing capacity.

Under serum-starved conditions, ADAR knockdown (KD) induced 6,351 differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate < 0.05), including ISGs (for example, ISG15, IFI6 and IFI44L; Extended Data Fig. 1d). Co-KD with IFIH1 abrogated most of this response (Extended Data Fig. 1e). With serum stimulation, ADAR KD led to a much greater effect with 12,747 differentially expressed genes, a dominant ISG response and near-complete MDA5 dependence (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g).

Principal-component analysis revealed that MDA5 activation (PC1) and serum stimulation (PC2) drove variance. ADAR KD shifted expression along PC1, reversed by IFIH1 co-KD (Extended Data Fig. 1h). These findings support MDA5-mediated ISG activation as the primary outcome of impaired RNA editing in SMCs.

ADAR1 and MDA5 regulate SMC maturation and key CAD transcription factors in phenotypic transition

Beyond ISG induction, ADAR KD reduced expression of key SMC markers ACTA2 and CNN1 under both serum-starved and serum-stimulated conditions (Extended Data Fig. 1i,j). This repression was exacerbated by serum and reversed by co-KD of IFIH1, indicating MDA5 dependence. ISG15 was markedly upregulated by ADAR KD and was enhanced with serum stimulation in an MDA5-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 1k).

The expression of transcription factors linked to CAD and SMC phenotype (KLF4, EGR1 and ATF3) was also upregulated following ADAR KD in an MDA5-dependent fashion (Extended Data Fig. 1l–n). Classical interferons IFNA1 and IFNG were not expressed, and IFNB1 and IFNAR1 were only minimally affected by ADAR KD in an MDA5-dependent mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d).

KEGG analysis of upregulated genes highlighted ‘TNF signaling’, ‘influenza A’ and ‘lipid and atherosclerosis’ (Supplementary Fig. 2e), whereas Gene Ontology (GO) terms emphasized ‘defense response to virus’ (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Downregulated pathways included ‘ribosome’, ‘focal adhesion’ and ‘ECM–receptor interaction’ (Supplementary Fig. 2g,h).

Global RNA editing is decreased in HCASMCs following phenotypic modulation in vitro

To evaluate how phenotypic transition affects RNA editing at the site level, we analyzed editing in HCASMCs. In control siRNA-treated cells, serum stimulation led to a modest but widespread reduction in editing across hundreds of sites (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Although no single site reached genome-wide significance, there was a consistent shift in editing frequencies.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Global RNA editing is decreased in HCASMC following phenotypic modulation in vitro.

In HCASMC, editing site specific comparison of RNA editing frequency for siRNA control in serum starved (X axis) vs serum stimulated (Y axis)(a). Editing site specific comparison of RNA editing frequency for siRNA control versus siRNA ADAR + IFIH1 (MDA5) in serum starved (b) and serum stimulated (c) conditions. Venn diagram of ADAR-dependent differentially edited sites (DES) (d) and DES-containing genes (e). Table of distinct ADAR-dependent DES-containing genes for serum stimulated and serum starved conditions (f). Volcano plot of DE gene analysis for immunogenic RNA between scramble siRNA treated cells under serum starved and serum stimulated conditions (g). Grouped bar charts of normalized RNAseq reads for (h) all immunogenic RNA, (i) SWAP70, and (j) TCTA. (h-j) P-values represent two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons post hox analysis. N = 3 RNA seq libraries per condition.

ADAR KD produced a greater effect, where in ADAR and IFIH1 double-KD cells, we observed significant editing loss across many sites under both serum-starved and serum-stimulated conditions (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c), identifying 1,101 differentially edited sites across 219 genes (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Of these, 226 sites (38 genes) were serum stimulation specific, and 357 sites (49 genes) were serum starvation specific. Although GO analysis did not reveal consistent enrichment, some genes (for example, SWAP70, FN1, GGCX and TCTA) reside within CAD GWAS loci5 (Extended Data Fig. 2f).

Next, we examined expression changes in 629 previously defined immunogenic RNAs. Serum stimulation altered expression of 82% of these genes (Extended Data Fig. 2g), although changes were balanced between up- and downregulation. Total expression of immunogenic RNAs by read count remained unchanged with serum stimulation but significantly decreased with ADAR KD during serum stimulation in an MDA5-dependent manner (P = 0.0022; Extended Data Fig. 2h).

We further assessed SWAP70 and TCTA, two immunogenic RNAs that colocalize with CAD GWAS. Serum stimulation upregulated the expression of both genes, but this effect was blocked by ADAR KD in an MDA5-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 2i,j), suggesting that MDA5 activation modulates immunogenic RNA expression.

TGFβ attenuates MDA5 and ISG activation in HCASMCs

Given the distinct effects of ADAR1 and MDA5 on the HCASMC response to serum stimulation, we explored their role (along with PKR, a downstream ISG effector of MDA5)34 in regulating HCASMC response to TGFβ, a procontractile stimulus. HCASMCs were treated with siRNAs targeting ADAR, IFIH1 and PKR, followed by serum starvation and TGFβ stimulation for 72 h.

Under control conditions, ADAR KD triggered a greater than 25-fold increase in ISG15, which was attenuated to less than 10-fold with TGFβ (Supplementary Fig. 3a). ISG15 induction was blocked by IFIH1 KD and was reduced by EIF2AK2 (PKR) KD, suggesting that PKR amplifies MDA5-driven ISG signaling (Supplementary Fig. 3a). By contrast, ISG activation with ADAR KD and serum stimulation was enhanced (that is, IFIH1; Supplementary Fig. 3b). TGFβ similarly blunted expression of IFIH1 and EIF2AK2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). IFIH1 KD lowered EIF2AK2 expression, confirming PKR as a downstream effector (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

KD of SMAD3, an effector of canonical TGFβ signaling, reduced ADAR KD-induced ISG15 and IFIH1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 3e,f), but the suppressive effect of TGFβ persisted, indicating involvement of noncanonical TGFβ signaling. TGFβ modestly upregulated ADAR (~2-fold) more than serum stimulation (~1.2-fold; Supplementary Fig. 3g,h). Eight days after siRNA treatment, ADAR levels normalized via IFIH1 but not EIF2AK2, suggesting MDA5-mediated feedback (Supplementary Fig. 3h).

Expression of the contractile marker ACTA2 was suppressed by both ADAR KD and TGFβ (Supplementary Fig. 3i). ACTA2 suppression by ADAR KD required MDA5 and PKR, whereas the effect of TGFβ was independent. TGFβ strongly induced PI16, a TGFβ-responsive gene, but this was blunted by ADAR KD in an IFIH1- and EIF2AK2-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 3j), suggesting that ADAR1, MDA5 and PKR modulate the SMC response to TGFβ.

ADAR1 and MDA5 regulate the transcriptomic and inflammatory response to calcification in vitro

To model SMC calcification, we cultured an immortalized HCASMC line under high-calcium/phosphate conditions, as has been previously reported35. ADAR KD in HCASMCs led to increased calcium deposition and cell death, which was reversed by co-KD of IFIH1 (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). RNA-seq revealed that calcification medium under scramble siRNA treatment promoted a significant gene expression response with 584 differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate < 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 3c). Top upregulated genes included numerous bone morphogenic protein-related signaling genes, including FBLN5, FMOD and RANBP3L (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f), effects that have been previously reported35. However, with ADAR KD, this effect was blunted in an MDA5-dependent mechanism (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). Although ISGs were not broadly activated by calcification alone (Extended Data Fig. 3g,h), ADAR KD sensitized cells to a proinflammatory program under procalcifying medium involving NFKB1, JUND, MMP1 and MMP10, all dependent on IFIH1 (Extended Data Fig. 3i–l). These findings indicate that ADAR1 restrains inflammation during calcification through MDA5 regulation.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Loss of ADAR1 regulates transcriptomic and inflammatory response to calcification in vitro.

Images of hTert immortalized human coronary artery SMCs following treatment with scramble, ADAR, ADAR + IFIH1, and IFIH1 siRNA and 7 days of culture in control medium (a) and calcification medium (b). (c) Volcano plot of DE gene analysis between scramble siRNA treated cells under control and calcification medium. (d-g) Grouped bar charts of normalized RNAseq reads for (d) FBLN5, (e) FMOD, (f) RANBP3L, (g) ISG15. (h) Principal component analysis (PCA) for PC1 and PC2 of bulk RNAseq data from each cell treatment. Grouped bar charts of normalized RNAseq reads for (i) NFKB1, (j) JUND, (k) MMP1, (l) MMP10. P-values represent two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons post hoc analysis. N = 3 RNA seq libraries per condition.

SMC-specific Adar maintains vascular integrity and survival in vivo

Although SMC-specific RNA editing has been linked to phenotypic responses36,37, its role in MDA5 activation and atherosclerosis remains unexplored. To investigate this, we generated mice with tamoxifen-inducible SMC-specific deletion of Adar (Myh11CreERT2; Adarfl/fl; RosatdTomato on an Apoe−/− background; Fig. 2a). Of 56 treated mice (n = 15 control, n = 21 SMC-Adar−/+ and n = 20 SMC-Adar−/−), homozygous SMC-Adar−/− animals rapidly developed weight loss, piloerection and hunched posture, a phenotype absent in heterozygous and control groups. By day 14, 50% of SMC-Adar−/− mice had died (Fig. 2b). Necropsy revealed aortic erythema and petechiae (Fig. 2c), with histology showing disrupted elastic lamellae, matrix separation and intramural hemorrhage (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Fig. 4). Fluorescence imaging showed loss of tdTomato+ SMCs along the adventitia with vessel wall ballooning (Fig. 2f–h). CD68 staining revealed macrophage infiltration (Fig. 2i), and Masson’s trichrome staining indicated intramedial fibrosis (Fig. 2j). These findings demonstrate that SMC ADAR1 is critical for vascular homeostasis and survival, consistent with a recent report published while this manuscript was in review38. Surviving mice remained underweight and ill. At 7 months, necropsy revealed fecal impaction, suggesting delayed gastrointestinal complications. Although no overt rupture was observed, the data suggest a multifactorial, inflammatory-driven cause of death.

Fig. 2. SMC-specific ADAR1 is required to maintain vascular integrity and survival.

a, Schematic of the SMC-Adar−/− model and accumulation of dsRNA and MDA5 activation. b, Survival curves for 56 mice treated with tamoxifen at 8 weeks of age (n = 15 control, n = 21 SMC-Adar−/+, n = 20 SMC-Adar−/−), comparing SMC-Adar−/−, SMC-Adar−/+ (Adarfl/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and control (AdarWT/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) genotypes. c, Gross image of the aortic root and ascending aorta of an SMC-Adar−/− mouse at 2 weeks following tamoxifen treatment. d,e, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining from SMC-Adar−/− (d) and control genotype mice (e). f,g, Fluorescence imaging with autofluorescence (Auto) indicating elastin (green) and MYH11-derived cells labeled with tdTomato (red) in two SMC-Adar−/− mice with adventitial ballooning. h, Brightfield imaging of an aorta cross-section from an SMC-Adar−/− mouse corresponding to fluorescence imaging in g. i, CD68 immunostaining of an aorta cross-section from an SMC-Adar−/− mouse showing macrophage infiltration. j, Masson trichrome stain of an aorta cross-section from an SMC-Adar−/− mouse showing intramedial collagen deposition. The P value represents comparison of survival curves by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (b).

Haploinsufficiency of MDA5 is sufficient to protect against mortality in SMC-Adar−/− mice

Given our in vitro findings implicating MDA5 as the central driver of ISG activation following ADAR1 loss, we tested whether Ifih1 deletion could rescue the lethal vascular phenotype observed in vivo. SMC-Adar−/− mice were crossed with constitutive MDA5 heterozygous (Ifih1−/+) and homozygous KO (Ifih1−/−) backgrounds, generating mice that were SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ or Ifih1−/− (Adarfl/fl; Ifih1−/+; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/− or Adarfl/fl; Ifih1−/−; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−). Following tamoxifen treatment (N = 32 mice total, n = 12 SMC-Adar−/−, n = 8 SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ and n = 12 SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/−), we found that both heterozygous and homozygous Ifih1 loss rescued survival in SMC-Adar−/− mice. By day 14, 10 of 12 (83%) SMC-Adar−/− mice had died, whereas both SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ and SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− mice showed minimal weight loss and no mortality (Fig. 3a–d). SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ mice were taken out to >24 weeks following tamoxifen dosing and continued to show minimal phenotype. Histological evaluation of aortic tissue showed preservation of elastin structure and medial architecture, comparable to controls (Supplementary Fig. 5). Interestingly, a small subset of MDA5-deficient mice exhibited transient weight loss within the first week after tamoxifen but subsequently recovered (Fig. 3c). This may suggest that other cytosolic RNA sensors, such as RIG-I, may partially contribute to the early inflammatory response.

Fig. 3. Haploinsufficiency in MDA5 is adequate to prevent mortality in SMC-Adar−/− mice.

a, Survival curves for SMC-Adar−/− (Adar1fl/fl; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−), SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ (Adar1fl/fl; Ifih1−/+; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− (Adarfl/fl; Ifih1−/−; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) genotypes following tamoxifen treatment at 8 weeks of age (N = 32 mice total, n = 12 SMC-Adar−/−, n = 8 SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/+ and n = 12 SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/−). b, Weight curve at 0, 7 and 14 days following tamoxifen treatment between genotypes of surviving mice. c, Individual weight measures at 0, 7 and 14 days following tamoxifen treatment between genotypes of surviving mice. d, Schematic diagram of SMC-Adar−/− and Ifih1 haploinsufficiency or global KO protecting against mortality. P values represent comparison of survival curves by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (a and b). The data points in b are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

scRNA-seq reveals SMC Adar controls ISG activation, phenotypic response and macrophage infiltration into the vessel wall

To investigate the cellular basis of vascular pathology in SMC-Adar−/− mice, we performed scRNA-seq of the aortic root/ascending aorta at 14 days after tamoxifen treatment (n = 7 control and n = 9 SMC-Adar−/− mice, 10 total libraries). Over 50,000 high-quality cells were retained. Dimensionality reduction and clustering revealed SMC-Adar−/− aortic cells to have a dramatic transcriptomic change compared to control genotype cells (Fig. 4a). We observed 13 distinct populations (Fig. 4a,b), including a contractile SMC cluster in controls and two SMC clusters exclusive to SMC-Adar−/− mice (SMC_cAdar1_KD1 and SMC_cAdar1_KD2; Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 4. SMC Adar controls ISG activation, phenotypic response and macrophage infiltration.

a, scRNA-seq UMAP from the aortic root and ascending aorta grouped by genotype of SMC-Adar−/− (Adarfl/fl; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and control (AdarWT/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) genotypes at 2 weeks following tamoxifen treatment (n = 7 control and n = 9 SMC-Adar−/− mice, 10 total libraries). b, UMAP with clustering and cell-type identification of combined SMC-Adar−/− and control genotype data. c, Feature plot of tdTomato expression showing SMC lineage tracing. d, Feature plot of Isg15 expression. e, RNAscope analysis of Isg15 expression in aortic tissue of SMC-Adar−/− mice showing highest Isg15 expression at the lumen aspect of the media, with additional adventitial expression. f, Feature plot of Ifnb1 expression. g, Heat map of network centrality scores for the CCL signaling network across cell clusters. h, Contributions of each receptor–ligand pair for CCL signaling. i, Chord diagram of receptor–ligand interactions between clusters for CCL5–CCR5. j,k, Feature plots of Ccl5 (j) and Ccr5 (k) expression.

These clusters showed robust ISG expression (that is, Isg15), which was confirmed by RNAscope analysis (Fig. 4d,e). tdTomato+ SMCs from SMC-Adar−/− mice had 2,382 differentially expressed genes compared to the control genotype that were enriched in interferon-related pathways (Supplementary Fig. 6), including ISGs and proinflammatory chemokines (Ccl5 and Cxcl10), alongside loss of contractile markers (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). SMC_cAdar1_KD2 displayed the highest inflammatory gene expression.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Loss of SMC Adar1 coordinates distinct response throughout vessel wall.

(a) Violin plot of Isg15, Ccl5, and Cxcl10 within SMC, SMC_cAdar1_KD_1, and SMC_cAdar1_KD_2 clusters of scRNAseq data clusters at 2 weeks following tamoxifen treatment for SMC-Adar1−/− (Adar1fl/fl, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−) and control (Adar1WT/WT, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−) genotypes. (b) Featureplot of Il6. (c) Violin plots of Cnn1 and Myh11 in SMC, SMC_cAdar1_KD_1, and SMC_cAdar1_KD_2 clusters. Featureplots of (d) Ly6a (Sca1), (e) Cd68, and (f) Gzma. (g) Chord diagram of receptor-ligand interaction between clusters for CCL2:CCR2. (h) Featureplot of Ccl2 and (i) Ccr2. (j) Chord diagram of receptor-ligand interaction between clusters for CCL4:CCR5. (k) Featureplot of Ccl4 and (l) Ccl7. P-value represents Wilcoxon Rank Sum test between groups (a, c).

We also identified an Sca1+ ISG-high fibroblast population (Extended Data Fig. 4d), suggesting an inflammatory fibroblast activation state39. Similarly, we observed immune clusters, including infiltrating macrophages (Mac_2) and cytotoxic T cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f), which were absent in controls, indicating widespread immune remodeling. Notably, classical type I interferons (Ifna1 and Ifnb1) and Il6 were minimally expressed, suggesting ISG activation via MDA5 rather than cytokine signaling (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Receptor–ligand interaction modeling implicates CCL5–CCR5 in coordinating macrophage infiltration in SMC-Adar−/− mice

To explore how SMC Adar deletion alters intercellular communication, we performed CellChat receptor–ligand analysis40. This revealed that SMC_cAdar1_KD1 and SMC_cAdar1_KD2 clusters were dominant senders of CCL signaling, particularly via CCL5–CCR5 (Fig. 4g,h). Circos analysis showed CCL5 originating from SMCs and signaling to macrophage and T cell populations via CCR5 (Fig. 4i). Feature plots confirmed Ccl5 expression in SMCs and Ccr5 expression in macrophages (Fig. 4j,k). Additional interactions included CCL2–CCR2, CCL4–CCR5 and CCL7–CCR2, linking SMCs, fibroblasts and macrophages to immune cells (Extended Data Fig. 4g–l). Notably, CCR5 is known to promote macrophage survival41, which may implicate CCL5–CCR5 as a key driver of immune cell recruitment and persistence.

Homozygous deletion of Ifih1 prevents transcriptomic effects of SMC-Adar−/−

To determine whether loss of ADAR1 exerts transcriptomic effects independent of MDA5, we performed scRNA-seq on SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− mice at day 14 after tamoxifen treatment, integrating with control and SMC-Adar−/− datasets (total n = 7 control, n = 9 SMC-Adar−/− and n = 9 SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− mice for 16 total libraries). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization revealed that SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− mice closely resembled controls, with absence of infiltrating macrophages, T cells and Sca1hi fibroblasts (Extended Data Fig. 5a). ISG induction (for example, Isg15 and Ccl5) was completely abolished across all cell types, including tdTomato+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b–e). Contractile SMC markers (Myh11 and Cnn1) were preserved with Ifih1 deletion (Extended Data Fig. 5f,g). Global gene expression profiles were nearly identical between control and double-KO mice (Extended Data Fig. 5h and Supplementary Table 4), indicating that most effects of SMC-Adar loss are secondary to MDA5 activation. A small subset of genes was consistently downregulated in both KOs, suggesting MDA5-independent roles for ADAR1, whereas a second subset showed opposing regulation, implying potential ADAR1-independent effects of MDA5 (Extended Data Fig. 5h).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Homozygous deletion of MDA5 (Ifih1) prevents transcriptomic effect of SMC-Adar1−/−.

(a) UMAP of integrated scRNAseq data set between control (Adar1WT/WT, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−), SMC-Adar1−/− (Adar1fl/fl, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−), and SMC-Adar1−/−, Mda5−/− (Adar1fl/fl, Ifih1−/−, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−) genotypes (total N=7 control, 9 SMC-Adar1−/−, and 9 SMC-Adar1−/−, Mda5−/− mice for 16 total libraries). Featureplot of (b) Isg15 and (c) Ccl5 split by genotype. Violin plot of tdTomato+ subset analysis split by genotype for (d) Isg15, (e) Ccl5, (f) Myh11, (g) Cnn1. (h) Heatmap visualization for normalized expression of marker genes for control, SMC-Adar1 KO, and SMC-Adar1 KO + Mda5 KO genotypes in tdTomato+ subset analysis. P-value represents Wilcoxon Rank Sum test between groups (d - g).

SMC-specific haploinsufficiency of Adar activates the ISG response in atherosclerosis and increases vascular chondromyoctye formation

Given the lethality of complete Adar loss in SMCs, we assessed whether partial deficiency affects vascular remodeling in atherosclerosis. SMC-Adar−/+ (Adarfl/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and control (AdarWT/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) mice were treated with tamoxifen at 7.5 weeks and fed a high-fat diet for 16 weeks (Fig. 5a). Weight and serum lipid levels were comparable between groups (Supplementary Fig. 7). scRNA-seq of the aortic root and ascending aorta (12 captures, 9 mice per group) yielded over 70,000 cells. Annotation revealed major vascular and immune populations, including distinct SMC subtypes (mature SMCs, FMCs and CMCs as we have previously observed27,29,30; Fig. 5b). An ISG-expressing SMC cluster (SMC_ISG) was markedly expanded in SMC-Adar−/+ mice (24.7% versus 1.1%, P < 1 × 10−100; Fig. 5b,c), with high Isg15, Ifit3, Irf7 and Ifih1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 5). GO terms included ‘response to interferon-β,’ ‘viral defense’ and ‘JAK–STAT signaling’ (Supplementary Fig. 8). With subset analysis of the SMC populations, SMCs undergo phenotypic modulation with downregulation of contractile markers (that is, Myh11) and upregulation of FMC/CMC markers (that is, Tnfrsf11b, Col2a1 and Acan; Supplementary Fig. 9), where the SMC_ISG cluster occupied a distinct intermediate position between contractile and modulated states (Fig. 5d,e). Markers of CMC differentiation, such as Col2a1 and Acan, were upregulated in SMC-Adar−/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 9e,f), and the proportion of CMCs increased significantly (22.6% versus 16.3%, P = 7.3 × 10−100; Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5. SMC-specific Adar haploinsufficiency activates the ISG response in atherosclerosis, increasing vascular chondromyoctye formation.

a, Schematic diagram of the 16-week, high-fat-diet atherosclerosis study. b, UMAP of scRNA-seq data from the atherosclerotic aortic root and ascending aorta at 16 weeks on a high-fat diet split by control (AdarWT/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and SMC-Adar−/+ (Adarfl/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) genotypes (12 captures, 9 mice per group). c, Feature plot of Isg15 split by genotype. d, UMAP of SMC subset analysis grouped by genotype. e, UMAP of SMC subset cluster analysis split by genotype showing SMC, SMC_ISG, FMC and CMC cell clusters. f, Stacked bar chart showing cell populations of SMC subsets for SMC, SMC_ISG, FMC and CMC clusters. g, Feature plot of Isg15 in SMC subsets split by genotype. h, Lineage trajectory analysis using Slingshot within SMC subsets showing two distinct lineages (SMC_ISG dependent and independent) from SMC to CMC. i,j, RNAscope for Isg15 in aortic root sections in control (i) and SMC-Adar−/+ (j) mice.

Lineage trajectory analysis of vascular chondrogenesis reveals a distinct ISG-dependent trajectory

To dissect the lineage trajectory from SMCs to CMCs, we applied Slingshot42 to high-resolution clusters of tdTomato+ cells. This analysis revealed two independent paths to CMC formation: one proceeding directly from FMCs and one via the ISG-rich SMC_ISG cluster (Fig. 5g,h). The ISG-dependent path featured sequential upregulation of Isg15, Irf7, Ly6a and ultimately CMC markers (for example, Col2a1, Chad and Spp1; Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Enriched pathways included viral sensing, JAK–STAT signaling and focal adhesion remodeling, implicating ISG-driven signaling in CMC differentiation.

Extended Data Fig. 6. ISG dependent trajectory analysis from SMC to CMC implicates distinct gene ontologies.

(a) Top genes for each ISG dependent trajectory cluster in DotPlot. (b) Top gene ontology pathways for marker genes of distinct clusters from ISG dependent trajectory.

RNAscope of Isg15 in aortic root sections confirmed marked enrichment in the media, throughout the plaque and in the adventitia of SMC-Adar−/+ mice (n = 6 per group; Fig. 5i,j and Extended Data Fig. 7a). However, in control mice, we also observed significant Isg15 expression within the media, the base of the plaque and in the adventitia (Fig. 5i). Isg15 signal was spatially distinct from Col2a1-expressing CMCs (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c), supporting the model that ISG activation precedes and facilitates CMC formation rather than marking fully differentiated CMCs.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Isg15 RNAscope reveals increased Isg15 signal in plaque of SMC Adar1−/+ mice.

(a) Quantification of Isg15 + area within the vessel wall between control and SMC Adar1−/+ mice following 16 week of high fat diet (N = 6 per group). (b-c) Representative images of Isg15 (b) and Col2a1 (c) RNAscope. P-values represent t-test for comparison.

SMC-specific haploinsufficiency in Adar increases plaque size and calcification in atherosclerosis

Histological assessment of aortic root sections revealed that SMC-Adar−/+ mice developed larger atherosclerotic plaques than control mice (N = 13 per group; Fig. 6a–d). This effect remained significant after normalization to internal elastic lamina (IEL) area, confirming it was not due to differences in vessel size. The medial layer (IEL to external elastic lamina (EEL)) was thinner in SMC-Adar−/+ mice, suggestive of increased SMC migration into the plaque (Fig. 6e,f). The plaque-to-media ratio was significantly higher (Fig. 6g), and outward remodeling, measured by EEL area, was also increased (Fig. 6h).

Fig. 6. SMC-specific haploinsufficiency in Adar increases plaque size and calcification in atherosclerosis.

a–h, Representative fluorescent images of aortic root plaque histology in control (a) and SMC-Adar−/+ (b) genotypes, with quantification of plaque area (c), plaque area normalized to IEL area (d) and media area (e), media area normalized to EEL area (f) and plaque area normalized to media area (g) and EEL area (h). i–l, Representative images of Ferangi Blue calcification staining in control (i) and SMC-Adar−/+ genotypes (j), quantification of Ferangi Blue area (k) and Ferangi Blue area normalized to plaque area (l). m, Schematic diagram showing the mechanism of dsRNA formation, MDA5 activation and impaired RNA editing by ADAR1 to accelerate SMC phenotypic modulation, calcification and atherosclerosis. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 13 per group. P values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed t-test.

To assess calcification, we performed Ferangi Blue staining of serial sections (Fig. 6i,j). SMC-Adar−/+ mice exhibited significantly greater total calcified area (n = 13 per group; Fig. 6k), and this effect remained after normalization to plaque size (Fig. 6l). These results demonstrate that SMC-specific Adar haploinsufficiency accelerates vascular calcification and plaque progression (Fig. 6m).

SMC-specific haploinsufficiency of Adar increases SMC lineage-traced cell content in plaques

To determine whether increased plaque size was due to enhanced SMC recruitment, we quantified tdTomato+ area within the plaque. SMC-Adar−/+ mice showed significantly greater SMC-derived cell content in the plaque body (P = 0.0024, n = 13 per group; Extended Data Fig. 8a–c), although this increase did not extend significantly to the fibrous cap (Extended Data Fig. 8d). Masson’s trichrome staining showed no significant difference in acellular (necrotic) plaque area between genotypes (n = 13 per group; Extended Data Fig. 8e–g), indicating that increased SMC content did not result in exaggerated plaque necrosis.

Extended Data Fig. 8. SMC specific haploinsufficiency in Adar1 increased SMC lineage traced cell content in plaque without change in acellular area.

Representative images of tdTomato (SMC derived) and overlay images with FITC and brightfield images in control (Adar1WT/WT, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−) (a) and SMC Adar1 het (Adar1fl/WT, Myh11CreERT2, ROSAtdTomato, ApoE−/−)(b) genotypes. Quantification of the percentage of tdTomato positive area in the plaque (c) and in the top 30 μm segment of the plaque representing the cap (d). Masson’s Trichrome staining with threshold analysis and acellular area quantification in control (e) and SMC-Adar1−/+ mice (f) with quantification (g). N = 13 per group. P-values represent t-test for comparison.

SMC-specific haploinsufficiency in Adar has minimal effect on macrophage content in atherosclerosis

Macrophage content was evaluated by scRNA-seq of non-tdTomato+ cells and suggested a modest increase (39.7% versus 35.2% of non-SMC cells; P = 3.66 × 10−26) in SMC-Adar−/+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). Receptor–ligand analysis using CellChat revealed no detectable CCL signaling from the SMC_ISG population (Extended Data Fig. 9c,d). Although total CD68+ area within the plaque was modestly increased in SMC-Adar−/+ mice (n = 13 per group; Extended Data Fig. 9e–g), this effect only trended toward significance when normalized to plaque area or area of the total vessel (Extended Data Fig. 9h,i). The lack of a major effect on macrophage content at this time point for this 16-week atherosclerosis Adar haploinsufficiency model is in contrast to our 2-week SMC-Adar−/− model (Fig. 2) and likely reflects a ‘dose-dependent’ response of SMC Adar gene deletion, MDA5 activation and Ccl5 expression.

Extended Data Fig. 9. SMC specific haploinsufficiency of Adar1 has minimal effect on macrophage infiltration in atherosclerosis.

(a) UMAP of scRNAseq data of non-tdTomato lineage traced cells from atherosclerotic aortic root and ascending aorta at 16 weeks high fat diet split by control and SMC-Adar1−/+ genotypes. (b) Stacked bar chart comparing proportion of macrophage cell population between control and SMC-Adar1−/+ genotypes in the non-tdT+ cells. (c) Heatmap of network centrality scores for CCL signaling network across cell clusters. (d) Dot plot of outgoing and incoming interaction strength across cell clusters for all signaling networks (left) and CCL signaling network (right). (e-f) Cd68 immunohistochemical staining within the aortic root following in control (e) and SMC- SMC-Adar1−/+ (f) mice (N = 13 per group). (g) Total area of Cd68 positive stain showing a significant increase in Cd68 in SMC-Adar1−/+ compared to control, however this effect is not significant when normalizing to (h) plaque area, or (i) vessel area at the internal elastic lamina (IEL). P-values represent chi-squared test (b) and unpaired two-tailed T-test (g-i).

Haploinsufficiency of Ifih1 prevents ISG activation and CMC formation in atherosclerosis in SMC-Adar−/+ mice

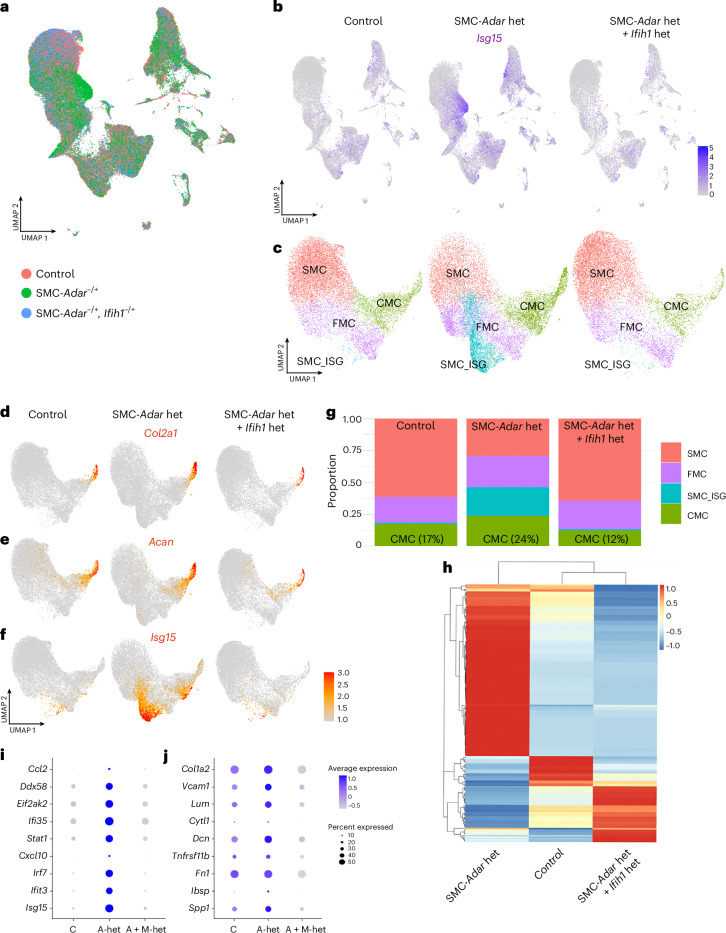

To test whether the observed phenotypes were mediated by MDA5, we bred SMC-Adar−/+ mice onto an Ifih1 heterozygous background and performed additional 16-week high-fat-diet atherosclerosis studies (18 total libraries, 9 mice per group). scRNA-seq of >96,000 cells revealed near-complete overlap between control and SMC-Adar−/+ + Ifih1−/+ genotypes (Fig. 7a), with widespread suppression of ISG expression (Fig. 7b). The SMC_ISG cluster was eliminated, and the proportion of CMCs decreased below control levels (12% versus 24% in SMC-Adar−/+ mice and 17% in control mice; Fig. 7c–g). Findmarker analysis in tdTomato+ SMCs showed that ISGs such as Isg15, Ifit3, Irf7 and Stat1 were significantly reduced in SMC-Adar−/+ + Ifih1−/+ mice to levels below those seen in control mice (Fig. 7h,i).

Fig. 7. Haploinsufficiency of Ifih1 prevents ISG activation and CMC formation in atherosclerosis in SMC-Adar−/+ mice.

a, UMAP of the integrated scRNA-seq data set between control (AdarWT/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−), SMC-Adar het (Adarfl/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) and SMC-Adar het + Ifih1 het (Adarfl/WT; Ifih1−/+; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−) genotypes following 16 weeks on a high-fat diet (18 captures, 9 mice per group). b, Feature plot of Isg15 split by genotype. c, UMAP of the tdTomato+ subset analysis with SMC, SMC_ISG, FMC and CMC clusters split by genotype. d–f, Feature plots split by genotype for Col2a1 (d), Acan (e) and Isg15 (f). g, Stacked bar charts showing the proportion of cells within ‘SMC’, ‘SMC_ISG’, ‘FMC’ and ‘CMC’ clusters split by genotype. h, Heat map visualization for normalized expression of marker genes for control, SMC-Adar het and SMC-Adar het + Ifih1 het genotypes in the tdTomato+ subset analysis. i,j, Dot plot gene expression split by genotype in SMC subsets for ISG genes (i) and FMC/CMC marker genes (j).

Markers of phenotypic transition and FMC/CMC formation (for example, Spp1, Fn1, Tnfrsf11b and Dcn) followed a similar trend with modest expression in controls, increased expression in SMC-Adar−/+ mice and reduced expression below control levels in SMC-Adar−/+ + Ifih1−/+ mice (Fig. 7j). This supports a critical role for MDA5 in SMC phenotypic modulation in atherosclerosis.

Ifih1 expression was upregulated in SMC-Adar−/+ mice (1.5-fold overall and 3.6-fold in SMCs) and reduced with Ifih1 haploinsufficiency (65% and 58% reduction in all cells and SMCs, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating that Ifih1 haploinsufficiency both prevents and reverses disease-associated upregulation.

ISG expression correlates with SMC phenotypic modulation, plaque vulnerability and calcification in a large human atherosclerosis dataset (Athero-Express)

Our prior work identified edQTLs that impair ADAR1 RNA editing are associated with increased ISG activation in human atherosclerotic plaques12. To determine whether these findings extend to a broader human dataset, we analyzed bulk RNA-seq data from 1,093 carotid plaques in the Athero-Express cohort43, paired with histology and clinical data (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8. ISG expression in a human atherosclerotic plaque dataset (Athero-Express) correlates with markers of SMC modulation, plaque vulnerability, plaque calcification and decreasing SMC investment into plaques.

a, Schematic diagram of the Athero-Express cohort and data evaluation. b,c, Linear relationship analysis between CMC markers LUM (b) and HAPLN (c) and ISG15 in 1,093 human samples. d,e, Dot plots displaying linear regression analyses between ISGs and LUM (d) and HAPLN (e) showing –log10 (P value) on the y axis and gene on the x axis with β coefficient scaled by color. f–h, Dot plots displaying linear regression analyses between ISGs and plaque phenotype corrected for covariates for plaque vulnerability (f), calcification (g) and SMC area within plaques (h).

We examined the expression of seven ISGs (ISG15, IFIH1, IFIT3, IFI16, IFI27, IFI35 and IFI44L), which varied widely across plaques with no sex differences (Extended Data Fig. 10a–d). ISGs were positively correlated, except IFIT3, which showed weak inverse correlation (Extended Data Fig. 10e). Notably, ISG expression was strongly associated with the CMC markers LUM and HAPLN (Fig. 8b–e). For instance, ISG15 was linearly associated with LUM (β = 0.44, P = 3.19 × 10−39; Fig. 8b).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Variability of ISG expression between patient carotid endarterectomy samples with no difference between sexes in Athero-Express cohort.

Histogram plot of patient distribution for (a) normalized IFIH1 and (b) ISG15 expression split by sex (male – blue, female – red) in 1093 patient samples. Histogram plot of patient density by sex for (c) normalized IFIH1 and (d) ISG15 expression. Heatmap plot of correlation beta value for ISGs (e). (f) Dot plot displaying linear regression analysis between ISGs and macrophage area within plaque corrected for co-variates with -log10 P value as Y axis.

After adjusting for covariates, IFIH1, IFI44L and IFIT3 remained positively associated with plaque vulnerability, with IFIH1 showing the strongest significance (P = 9.71 × 10−135; Fig. 8f), and IFIH1 was also linked to calcification (P = 0.02; Fig. 8g). Several ISGs, including IFI16 and ISG15, were inversely correlated with SMC area (for example, IFI16, P = 2.6 × 10−4; Fig. 8h), but not macrophage area, aside from IFI44L, which had a weak negative correlation (Extended Data Fig. 10f).

Discussion

Both academic and industry leaders are leveraging human genetics to uncover causal disease biology and guide therapeutic development44. The rapid identification of genome-wide significant loci for complex traits has created challenges in target prioritization45,46, particularly when many loci lack clear mechanistic insight. The recent discovery that edQTLs that impair RNA editing are associated with increased CAD risk and ISG activation12 highlights a unifying disease pathway centered on a single effector: MDA5. Notably, 20% of CAD risk loci colocalize with edQTLs12, emphasizing the relevance of this pathway in disease risk.

Here, we define a mechanistic link between RNA editing, dsRNA sensing via MDA5 and vascular disease. Analysis of human atherosclerotic scRNA-seq data shows that vascular SMCs express immunogenic RNA at high levels and that ISG activation coincides with SMC phenotypic modulation (Fig. 1). In vivo, conditional deletion of Adar in adult SMCs leads to loss of vascular integrity and mortality due to MDA5 activation (Figs. 2 and 3). scRNA-seq revealed ISG induction and immune cell recruitment in the vessel wall (Fig. 4), an effect prevented by Ifih1 deletion (Extended Data Fig. 5), indicating that the primary role of ADAR1 in SMCs is to suppress MDA5 activation.

In a 16-week atherosclerosis model, SMC-Adar−/+ mice show cell-type-specific ISG activation, promoting phenotypic modulation, vascular CMC formation and modest macrophage recruitment (Fig. 5). This is associated with increased plaque size, medial thinning and vascular calcification (Fig. 6). These effects are rescued by Ifih1 haploinsufficiency (Fig. 7), reinforcing MDA5’s role in this pathogenic axis. Supporting human relevance, by using data from the Athero-Express cohort of carotid atherosclerotic plaques, we revealed that ISG expression has a linear relationship with SMC markers of phenotypic modulation and correlates with plaque vulnerability and calcification, with no effect on macrophage content (Fig. 8 and Extended Data Fig. 10).

These results support a model in which RNA editing demand varies by cellular context. Prior studies using SMC-Adar−/+ mice in carotid injury and abdominal aortic aneurysm models suggested impaired phenotypic modulation with loss of SMC Adar36,37 but did not evaluate MDA5. Our findings suggest a dose- and context-dependent relationship where in specific contexts, such as atherosclerosis, partial loss of ADAR1 may overwhelm editing capacity and enable MDA5 activation. This could explain why ISG activation is observed in atherosclerosis but not in short-term injury models. Moreover, a recent GWAS implicated IFIH1 in abdominal aortic aneurysm47, further supporting this axis in vascular disease.

Our data reveal that SMC-specific MDA5 activation facilitates a unique trajectory in the formation of CMCs and calcification in atherosclerosis. This effect of MDA5 activation on SMC phenotypic state is consistent with prior work investigating the role of ADAR1 and MDA5 on cellular proliferation and cell death48. ADAR1 is crucial in regulating proliferation and deterring endogenous dsRNA from triggering transcriptional shutdown and apoptotic cell death through activation of PKR48. Whereas loss of ADAR1 initially may promote proliferation and changes in phenotypic state, ongoing MDA5 activation triggers PKR and cell death48. This model fits our data, where SMC-Adar−/+ mice exhibit enhanced phenotypic transitions (Fig. 5), whereas SMC-Adar−/− mice undergo overwhelming transcriptional shutdown and loss of vascular integrity (Fig. 3). In the human plaque dataset, ISG expression correlates with decreased SMC area in the plaque, which may be consistent with MDA5-mediated death (Fig. 8).

Although classical inflammatory cytokines (for example, IL-6, TNF and IL-1β) have been implicated in atherosclerosis49, it is intriguing that out of hundreds of CAD risk loci, relatively few point to these pathways2–5. The modest clinical effect of IL-1β antagonism in CAD50 raises questions about targeting these mediators. By contrast, MDA5-mediated dsRNA sensing and ISG induction in SMCs emerges as a distinct inflammatory mechanism of disease.

Although ISGs are broadly antiviral, their function in atherosclerosis remains uncertain. Interferons and ISGs act via JAK–STAT signaling to regulate transcriptional shutdown in infected cells51. Our trajectory analysis reveals that JAK–STAT activation is enriched along the ISG-driven CMC transition (Fig. 5h and Extended Data Fig. 6), which may suggest that ISGs shape SMC fate. Specific ISGs have defined antiviral roles, for example, IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 block viral entry, IFI16 regulates mRNA synthesis, ISG20 degrades mRNA, and PKR halts protein translation51, but their contribution to vascular remodeling is unclear.

Importantly, we have recently observed that CAD heritability is mediated to a greater extent by edQTLs than eQTLs12, underscoring the importance of this mechanism in disease and raising the therapeutic potential of targeting this axis. The data presented here further implicate a specific mechanism of disease while highlighting a unique opportunity to leverage this biology for therapeutic development by prioritizing the inhibition of dsRNA sensing and downstream activation of MDA5.

Methods

Mouse models

To generate SMC-specific deletion of Adar, we used the Adarfl/fl allele (exons 7–9 floxed; MGI allele: Adartm1.1Phs; MGI:3828307), as we have reported previously52, crossed onto the validated SMC-specific mouse Cre allele (Myh11CreERT2; 019079, Jackson Laboratory) combined with the floxed tdTomato fluorescent reporter protein gene knocked into the Rosa26 locus (B6.Cg-Gt(Rosa)26Sortm14(CAGtdTomato)Hze/J; 007914, Jackson Laboratory) and Apoe−/− alleles (Adarfl/fl; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato/+; Apoe−/−) backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background. To induce homozygous or heterozygous deletion of Adar in SMCs (SMC-Adar−/−: Adar1fl/fl; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/− or SMC-Adar−/+: Adarfl/WT; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato; Apoe−/−), mice received two doses of tamoxifen (200 mg per kg (body weight) by mouth) at 7.5–8 weeks of age (dose 1 on day 0 and dose 2 on day 2) and were started on a high-fat diet, as we have done previously27,30. To evaluate the effect of Ifih1 KO on the Adar-KO background, we crossed the Ifih1−/− mouse (B6.Cg-Ifih1tm1.1Cln/J; 015812, Jackson Laboratory), which we have used previously52, onto the above background in a heterozygous manner to generate SMC-Adar−/− × Ifih1−/+ mice (Adarfl/fl; Ifih1−/+; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato/+; Apoe−/−), SMC-Adar−/− × Ifih1−/− mice (Adarfl/fl; Ifih1−/−; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato/+; Apoe−/−) or SMC-Adar−/+ × Ifih1−/+ mice (Adarfl/WT; Ifih1−/+; Myh11CreERT2; RosatdTomato/+; Apoe−/−). As the Cre-expressing BAC was integrated into the Y chromosome, all lineage-tracing mice in the study were male. The animal study protocol was approved by the Administrative Panel on the Laboratory Animal Care and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University. Mice were given access to a standard chow diet until initiation of a high-fat diet (Dyets, 101511; 21% anhydrous milk fat, 19% casein and 0.15% cholesterol). Food and water were available ad libitum, and mice were housed on a standard 12-h light/12-h dark cycle.

Mouse aortic root/ascending aorta cell dissociation

Immediately after the mice were killed, all animals were perfused with PBS. The aortic root and ascending aorta were excised, up to the level of the brachiocephalic artery. Tissue was washed three times in PBS, placed into an enzymatic dissociation cocktail (2 U ml−1 Liberase (5401127001, Sigma–Aldrich) and 2 U ml−1 elastase (LS002279, Worthington) in HBSS), incubated at 37 °C for 45 min and subsequently minced. The cell suspension was further dissociated with a 1-ml pipette 20 times, and single-cell suspensions were confirmed under a microscope. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min. The enzyme solution was then discarded, and cells were resuspended in fresh HBSS and passed through a 35-μm filter into a FACS tube. To increase biological replication, a single mouse was used to obtain single-cell suspensions, and three mice were used in combination for each scRNA capture. Three separate isolations were performed for control, SMC-Adar−/+, SMC-Adar−/−, SMC-Adar−/− + Ifih1−/− or SMC-Adar−/+ + Ifih1−/+ mice. Cells were sorted by FACS based on tdTomato expression. tdTomato+ cells (considered to be of SMC lineage) and tdTomato− cells were then captured on separate but parallel runs of the same scRNA-seq workflow (the gating strategy and threshold were identical to those published previously by Wirka et al.29), and datasets were later combined for all subsequent analyses.

Mouse aortic root histology

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to standard protocol. Primary rabbit polyclonal antibody to CD68 (1:400 dilution; ab125212, Abcam) with secondary rabbit-on-rodent HRP polymer (RMR622, BioCare Medical) was used for CD68 evaluation. H&E and trichrome staining were performed using standard protocols and H&E and Trichrome Stain kits (Abcam, ab245880 and ab150686, respectively). Processed sections were visualized using a Leica DM5500 microscope objective magnifications, and images were obtained using Leica Application Suite X software. For quantification of atherosclerosis plaque area, sections obtained at equal distance measured from the superior margin of the coronary sinus were used for comparison to ensure equal level sections were obtained. Images with FITC autofluorescence and tdTomato expression in the red channel representing SMC lineage-traced cells were obtained. Areas of interest were quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) software and compared using a two-sided t-test. Lesion size was defined by the area encompassing the intimal edge of the lesion to the border of the SMC marker-positive intima–media junction. Calcification was evaluated using a Ferangi Blue Chromogen Kit 2 (Biocare Medical, FB813) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For RNAscope, slides were processed and hybridized according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with reagents from ACD Bio. All area quantification was performed in a genotype-blinded fashion with ImageJ by using length information embedded in exported files. All biological replicates for each staining were performed simultaneously on position-matched aortic root sections to limit intraexperimental variance.

Single-cell capture, library preparation and sequencing

All single-cell capture and library preparation procedures were performed in the laboratory of T.Q., and sequencing was performed by Medgenome, Inc. Cells were loaded into a 10x Genomics microfluidics chip and encapsulated with barcoded oligo(dT)-containing gel beads using a 10x Genomics Chromium controller, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Single-cell libraries were then constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). Libraries from individual samples were multiplexed into one lane before sequencing on an Illumina platform with a targeted depth of 50,000 reads per cell for RNA or 400 million paired-end reads per sequencing library.

Analysis of scRNA-seq data

Fastq files from each experimental time point and mouse genotype were aligned to the reference genome (mm10) individually using CellRanger Software (10x Genomics). The dataset was then analyzed using the R package Seurat 30 (ref. 28), and datasets were merged in Seurat using the standard Merge function. The dataset was trimmed of cells expressing fewer than 2,000 genes and genes expressed in fewer than 50 cells. The number of genes, number of unique molecular identifiers and percentage of mitochondrial genes were examined to identify outliers. As an unusually high number of genes can result from a ‘doublet’ event, in which two different cell types are captured together with the same barcoded bead, cells with >9,000 genes were discarded. Cells containing >7.5% mitochondrial genes were presumed to be of poor quality and were also discarded. Gene expression values then underwent library size normalization and were normalized using the established LogNormalize function in Seurat. No additional batch correction was performed. Principal component analysis was used for dimensionality reduction, followed by clustering in principal component analysis space using a graph-based clustering approach via the Louvain algorithm. A UMAP was then used for two-dimensional visualization of the resulting clusters. Pseudotime trajectory analysis was performed using Slingshot42 with available software. Analysis, visualization and quantification of gene expression and generation of gene module scores were performed using Seurat’s built-in functions, such as ‘FeaturePlot’, ‘VlnPlot’, ‘AddModuleScore’ and ‘FindMarker’. Inference analysis of cell–cell communication was performed using CellChat40. A standard CellChat protocol was used where overexpressed genes, interactions and communication probability were computed and subsequently aggregated and visualized across cell clusters.

For the immunogenic RNA score, we generated an AddModuleScore ‘score’ that summates the expression of all ‘immunogenic’ RNA from a putative list that was generated by combining our data from experimental in vitro models23 along with human genetic edQTL analysis12. A complete list of immunogenic RNA is included in Supplementary Table 1.

HCASMC culture and in vitro genomic studies

Primary HCASMCs were isolated from human donor explanted hearts for culture by Lonza Bioscience. Cells were cultured in smooth muscle growth medium (Lonza, CC-3182) supplemented with human epidermal growth factor, insulin, human basic fibroblast growth factor and 5% fetal bovine serum, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All HCASMC lines were used at passages 4–8. HCASMCs immortalized with the hTert transgene were acquired from C. Miller (University of Virginia) and were used for all calcification assays with HCASMCs between passages 31 and 35. siRNA KDs were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Life Technologies) using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol at 50 pg of siRNA per 100,000 cells. Dharmacon SMART selection siRNA was used for siRNA KD experiments (Horizon Dharmacon).

Phenotypic transition, calcification and TGFβ assays

For phenotypic transition assays, HCASMCs were cultured in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and subjected to serum starvation for 2 days. After 2 days of serum starvation (0% BSA), HCASMCs developed a mature SMC phenotype, and reintroduction of serum (5%) stimulated a more proliferative phenotype. RNA and protein were isolated 48 h following the reintroduction of serum. For calcification assays, HCASMCs were cultured in 1% BSA with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 8 mM CaCl2 for 7 to 10 days. For TGFβ stimulation assays, we cultured HCASMCs to confluency, treated the cells with siRNA for 48 h and transitioned the cells to serum-free conditions for 72 h. We then stimulated the cells with TGFβ (10 ng ml−1) or control for 72 h before RNA isolation and quantitative PCR with reverse transcription.

RNA isolation and bulk RNA-seq

RNA was isolated from disrupted HCASMCs using the standard RNeasy mini kit protocol (Qiagen). Isolated RNA underwent quality assessment, cDNA conversion and library construction by Novogene. cDNA libraries were sequenced using an Illumina Novoseq 6000, achieving 20–30 million paired-end reads per sample. RNA-seq data were processed using a workflow starting from fastq files, and the code is available on GitHub (https://github.com/zhaoshuoxp/Pipelines-Wrappers/blob/master/RNAseq.sh). In brief, quality control was performed using FastQC, mapping to the human genome hg19/GRCh37 was performed using STAR second-pass mapping to increase the percentage of mapped reads, and counting was performed with featureCounts using the GENCODE gtf annotation. Differential analysis was then performed using DESeq2.

RNA editing analysis

RNA editing analysis of the bulk RNA-seq data was performed following a pipeline as we have described previously12. Briefly, we compiled a list of reference editing sites for quantification. By incorporating known sites in the RADAR database53, tissue-specific sites identified in GTEx V6p17 and recently published hyperediting sites54, we finalized a list of 2,802,572 human editing sites. To quantify editing levels, we computed the ratio of G reads divided by the sum of A and G reads at each site. Because the bulk RNA-seq data from HCASMCs was not strand specific, the reads cannot be automatically assigned to sense and antisense strands; as such, quantification of editing level may be affected by expression of either of the two overlapping genes. Therefore, we developed a method to measure the RNA editing level of a given site using reads derived from the corresponding transcript (sense for A-to-G edits and antisense for T-to-C edits), with less influence by the other overlapping transcript. For reads that are edited, they would be derived from the sense transcript if the edits are A-to-G and derived from the antisense transcript if the edits are T-to-C. For the rest of the reads that were unedited, we estimated the numbers derived from the sense versus antisense transcripts in proportion to their expression levels. Overall RNA editing frequency was reported as percentage of total RNA editing sites across the genome.

Athero-Express bulk RNA isolation/RNA-seq, histological staining and analysis

Data from the Athero-Express Biobank study were used for ISG expression validation in human carotid endarterectomy samples. The Athero-Express study is an ongoing biobank study including individuals undergoing endarterectomy from two tertiary hospitals in the Netherlands. Participants provided written informed consent, the medical ethics committees of the respective hospitals approved of the study (protocol number 22/018), and the study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki55. A total of 1,093 plaque segments were selected from two subsequent experiments, Athero-Express RNA Study 1 and Study 2 (n = 622 and n = 471, respectively). RNA was isolated using in-house standardized protocols. Library preparation used the CEL-seq2 method. This method yielded the highest mappability of reads to the annotated genes. Specifically, this method captures the 3′ end of polyadenylated RNA species and includes unique molecular identifiers, which allows for direct counting of unique RNA molecules. This method of plaque sample processing for RNA isolation and library preparation has been previously described in detail43. Both AERNAS1 and AERNAS2 were mapped against the cDNA reference of all transcripts in GRCh38.p13 and Ensembl 108 (GRCh38.p13/ENSEMBL_GENES_108). These include raw read counts of all nonribosomal, protein-coding genes with existing HGNC gene names. All read counts were corrected for unique molecular identifier sampling by ‘raw.genecounts = round(–4,096 × (log (1 – (raw.genecounts / 4,096))))’.

For histological analysis, stained slides were digitally stored up to ×40 magnification. Semiquantitative scoring was performed by two independent observers and a third independent observer if interpretations between the first two differed. Multiple stains were used to phenotype each plaque segment. Collagen content was assessed using picrosirius red and elastin von Gieson staining. SMCs were identified using α-actin, and macrophages were identified using CD68 staining. H&E staining was used to evaluate calcification and the lipid core. In combination with fibrin (Mallory’s phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin), H&E was also used to detect the presence of intraplaque hemorrhage. The semiquantitative scoring protocol has been described previously55,56. α-Actin (SMC) and CD68 (macrophage) were also quantitatively analyzed by computerized analysis. To assess plaque vulnerability, we used the plaque vulnerability index, a histological score incorporating collagen, macrophages, SMCs, lipid content and intraplaque hemorrhage55. Each trait was scored as stable or unstable, yielding a cumulative vulnerability score from 0 to 5.

Multivariable linear regression analyses between ISG expression and plaque characteristics were performed in R (version 4.4.1) using the ‘lm()’ function to fit a linear model. Bulk RNA-seq counts of ISG genes were transformed using variance stabilization transformation. For each ISG and phenotype (SMCs, macrophages, calcification and plaque vulnerability index), we modeled gene expression against the phenotype and corrected for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes and smoker status, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, use of lipid-lowering drugs, use of antiplatelets drugs, estimated glomerular filtration rate based on the MDRD formula, body mass index, history of cardiovascular diseases, level of stenosis and year of surgery. For the linear regression analysis between ISG expression and CMC markers (LUM and HAPLN), the bulk RNA-seq counts of both ISGs and CMC markers were transformed using variance stabilization transformation. We modeled each ISG against both CMC markers and corrected for age, sex and year of surgery.

Statistics and reproducibility

Differential expression of genes by scRNA-seq was identified using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The distribution of cells within defined populations was tested by χ2 test. Significance determination of histological measurements and RT–qPCR results was performed by two-tailed t-test, which was performed after verifying normal distribution with Prism software or by two-way ANOVA when comparing multiple treatment groups. Multiple comparisons were corrected by Bonferroni correction when necessary.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10.

Supplementary Table 1. List of immunogenic RNA. Supplementary Table 2. Findmarker gene list for SMC clusters from the human carotid dataset. Supplementary Table 3. Findmarker gene list for all clusters in SMC Adar-KO and control genotypes. Supplementary Table 4. Findmarker gene list for the SMC comparison between control, SMC Adar-KO and SMC Adar KO + Ifih1 KO. Supplementary Table 5. Findmarker gene list for all clusters in SMC Adar het and control atherosclerosis. Supplementary Table 6. Findmarker gene list for the SMC comparison between control, SMC Adar het and SMC Adar het + Ifih1 het in atherosclerosis.

HCASMC RNA-seq expression for IFN genes.

HCASMC qPCR expression after TGFβ treatment.

Lipids for 16-week high-fat-diet atherosclerosis studies.

Source data

Findmarker file showing differential gene markers between SMC clusters 2 and 0 in the human SMC subset. All other data are publicly available in Alsaigh et al.24 and Sharma et al.32 and in Supplementary Table 2.

Survival data for the SMC Adar-KO study.

Survival data (sheet 1) and weight data (sheet 2) for SMC Adar-KO and Ifih1-KO mice.

Plaque area and calcification data.

Data for ISG and SMC phenotypic marker linear regression and plaque phenotype for Athero-Express data.

RNA editing frequency and normalized RNA-seq reads per gene of interest.

RNA editing frequency by site and by gene along with HCASMC expression of immunogenic RNA and selected genes.

HCASMC RNA-seq expression by treatment.

Quantification of RNAscope area of Isg15.

Quantification of tdTomato and acellular area.

Quantification of CD68 stain area.

Data for ISG and SMC phenotypic marker linear regression and plaque phenotype for Athero-Express data.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported National Institutes of Health grants F32HL160067 (C.S.W.), L30HL159413 (C.S.W.), K08HL167699 (C.S.W.), K08HL153798 (P.P.C.), R01HL179083 (P.P.C.), R01HL134817 (T.Q.), R01HL139478 (T.Q.), R01HL156846 (T.Q.), R01HL151535 (T.Q.), R01HL145708 (T.Q.), UM1HG011972 (T.Q.), R35GM144100 (J.B.L.), R01MH115080 (J.B.L.), R01GM102484 (J.B.L.), R00HL150319 (H.G.), K08HL177251 (B.T.P.) and U01DK142283-01 (S.W.v.d.L.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association grants 20CDA35310303 (P.P.C.), 23CDA1042900 (C.S.W.), 23POST1018991 (W.G.), 24POST1187860 (J.P.M.), 24SCEFIA1248386 (P.P.C.) and 24CDA1272805 (B.T.P.). Additional funding includes EU H2020 TO_AITION (848146), EU HORIZON NextGen (101136962), EU HORIZON MIRACLE (101115381), Health~Holland PPP Allowance, the Leducq Foundation ‘PlaqOmics’ (18CDV-02) and ‘AtheroGen’, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative ‘MetaPlaq’ and the AI for Health working group of the EWUU alliance (https://aiforhealth.ewuu.nl/).

Extended data

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.S.W., Q.L., P.P.C., J.B.L. and T.Q. Methodology: C.S.W., Q.L. and J.P.M. Investigation: C.S.W., Q.L., J.P.M., H.G., D.G., W.G., M.D.W., Q.Z., D.S., M.R., D.L., B.T.P., A.B., R.K.K., T.N., T.S.P., M.M., C.L.M. and S.W.v.d.L. Visualization: C.S.W. Funding acquisition: C.S.W., J.B.L. and T.Q. Project administration: C.S.W., J.B.L. and T.Q. Supervision: J.B.L. and T.Q. Writing, original draft: C.S.W., J.B.L. and T.Q. Writing, review and editing: C.S.W., Q.L., J.B.L. and T.Q.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cardiovascular Research thanks Minna Kaikkonen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All raw and processed sequencing data are available within the manuscript files and are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus. Bulk and scRNA-seq data are available through accession IDs GSE254862, GSE255661 and GSE280641. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

C.S.W. is a consultant for AiRNA Bio and Avidity Biosciences. T.Q. serves on the scientific advisory board for Amgen. J.B.L. is a cofounder of AIRNA Bio and a consultant for Risen Pharma. J.B.L. and Q.L. are named inventors of a patent filed by Stanford University (WO/2023/239781), describing a method related to genetic prediction of RNA editing that relates to human prediction of dsRNA burden. S.W.v.d.L. has received Roche funding for unrelated work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Jin Billy Li, Thomas Quertermous.

Contributor Information

Chad S. Weldy, Email: weldyc@stanford.edu

Thomas Quertermous, Email: tomq1@stanford.edu.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s44161-025-00710-5.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s44161-025-00710-5.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet396, 1204–1222 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nikpay, M. et al. A comprehensive 1,000 genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet.47, 1121–1130 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schunkert, H. et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet.43, 333–338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Harst, P. & Verweij, N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ. Res.122, 433–443 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tcheandjieu, C. et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study of coronary artery disease in genetically diverse populations. Nat. Med.28, 1679–1692 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albert, F. W. & Kruglyak, L. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet.16, 197–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science369, 1318–1330 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg, E. & Levanon, E. Y. A-to-I RNA editing—immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat. Rev. Genet.19, 473–490 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonkhout, N. et al. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA23, 1754–1769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walkley, C. R. & Li, J. B. Rewriting the transcriptome: adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing by ADARs. Genome Biol. 18, 205 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatsiou, A. & Stellos, K. RNA modifications in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.20, 325–346 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, Q. et al. RNA editing underlies genetic risk of common inflammatory diseases. Nature608, 569–577 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishikura, K. Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem.79, 321–349 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain, M. et al. RNA editing of filamin A pre-mRNA regulates vascular contraction and diastolic blood pressure. EMBO J.37, e94813 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pestal, K. et al. Isoforms of RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 independently control nucleic acid sensor MDA5-driven autoimmunity and multi-organ development. Immunity43, 933–944 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liddicoat, B. J. et al. RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science349, 1115–1120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mannion, N. M. et al. The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep.9, 1482–1494 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feigenbaum, A. et al. Singleton–Merten syndrome: an autosomal dominant disorder with variable expression. Am. J. Med. Genet. A161A, 360–370 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]