Highlights

-

•

Endometrial cancer can rarely metastasize to the foot; such cases signal advanced disease.

-

•

Persistent foot pain in cancer patients warrants imaging to exclude atypical metastases.

-

•

Timely imaging and biopsy are key for diagnosing unusual metastatic spread in endometrial cancer.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Foot metastasis, MRI, FDG PET/CT

Abstract

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma typically metastasizes to the lungs, liver, and bones of the axial skeleton. Metastatic spread to the bones of the foot is exceedingly rare and may present with nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, often mimicking infection. Recognizing such atypical metastatic patterns is essential for timely diagnosis and management, particularly in patients with high-risk disease.

Case report

A 62-year-old woman with FIGO stage IIIB endometrioid adenocarcinoma, previously treated with surgery and radiotherapy, presented with progressive pain and swelling of the right foot. Initial clinical evaluation suggested cellulitis, and empiric antibiotics were started. Symptoms persisted, prompting further investigation. MRI demonstrated diffuse marrow abnormalities and cortical disruption in multiple tarsal bones, raising suspicion for malignancy. Biopsy confirmed metastatic endometrioid adenocarcinoma. FDG PET-CT revealed intense uptake in the foot lesion, as well as additional FDG-avid lesions in the right femur, fibula, metatarsal, and a pulmonary nodule, consistent with widespread metastatic disease.

Conclusion

Metastases to the bones of the foot from endometrial carcinoma are rare and can mimic infection. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for unusual metastatic patterns in patients with persistent musculoskeletal symptoms and a history of high-risk endometrial cancer. Timely imaging and histologic confirmation are critical for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management, especially as such presentations often indicate advanced systemic disease.

1. Introduction

Uterine cancer is the most common of the gynecologic cancers (Menczer, 2000). Endometrioid adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic subtype. Recurrences remain a major challenge, particularly in high-risk patients after surgery, with a median interval to recurrence of 2–3 years. Sites of recurrence are almost equally distributed between vaginal/pelvic and distant (abdominal or lung) metastases. The most common sites of recurrent disease are the vaginal vault, pelvis, abdomen, and lungs (Siegel et al., 2025). Bone metastases represent an usual site of disease dissemination in patients with endometrial cancer (EC) with an overall incidence of less than 1 % (Uccella et al., 2013). Metastasis of the foot bones in EC patients (discovered either upon EC diagnosis or upon location of the primary site of recurrence) is exceedingly rare. As far as we know, 7 cases have been documented in the literature, including the present case (Chuang and Wang, 2025, Libson et al., 1987, Zorzi and Pescatori, 1982, Janis and Feldman, 1976, Litton et al., 1991, Cooper et al., 1994).

Here, we report a 62-year-old woman with a history of FIGO stage IIIB endometrioid adenocarcinoma who, five months after completing primary treatment, presented with an exceptionally rare foot bone metastasis. This case is clinically significant, as timely recognition of this atypical metastatic pattern is essential to guide appropriate treatment and supportive care.

2. Case report

A 62-year-old woman presented at the outpatient clinic with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. On examination, a tumorous process protruding through the cervix was observed. Biopsy revealed an endometrioid type adenocarcinoma, at least grade 2, most likely arising from the lower uterine segment/isthmus area. Tumor was classified as MMR proficient.

She subsequently underwent abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy, resection of vaginal metastasis, and repair of the vaginal wall defect. Cystoscopy excluded bladder or urethral injury. Final pathology demonstrated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium, grade 3, arising from the lower uterine segment/isthmus, with a maximum diameter of 6.5 cm, deep myometrial invasion (≥50 %), substantial vascular invasion, and cervical stromal involvement. Vaginal involvement was present, with positive resection margins at the vaginal cuff. The adnexa were tumor-free.

She was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy postoperatively. Radiotherapy consisted of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) of the pelvis and bilateral groins with 28 × 1.8 Gy using 10 MV photons, followed by three fractions of vaginal brachytherapy (3 × 6 Gy) using a vaginal cylinder, prescribed at 5 mm from the vaginal wall.

In February 2025 she presented with progressive pain and swelling of the right foot. Weight-bearing was impossible, and even light touch provoked severe pain. Physical examination revealed warmth, redness, and swelling extending to the ankle, with linear pallor and reticular skin discoloration, suggestive of cellulitis or erysipelas. Empiric treatment with flucloxacillin was initiated. There was no history of trauma to the foot in the patients recent past.

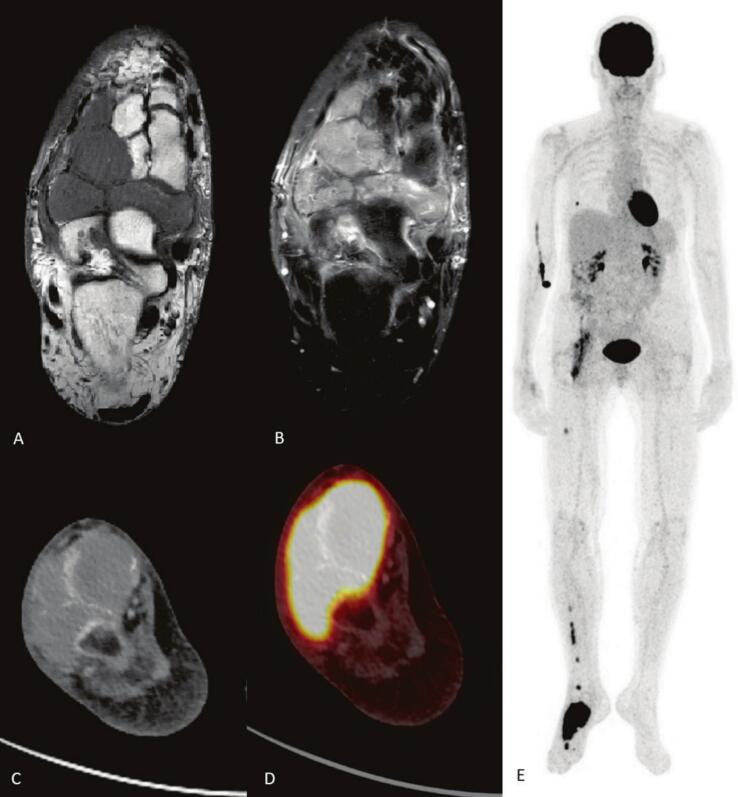

Symptoms persisted, and in March 2025 she was referred to the orthopedic department. Plain radiography demonstrated marked osteopenia. MRI showed extensive marrow signal abnormalities in the navicular, cuboid, and lateral cuneiform bones, with post-contrast enhancement and cortical disruption extending into adjacent soft tissues. Additional focal lesions were observed in the metatarsals, talus, and medial cuneiform. Subcutaneous edema and subchondral changes in the calcaneus were also present. Although the location was atypical, the imaging pattern raised suspicion for malignancy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MRI of the right foot and FDG-PET-CT. A) Unenhanced T1 of the right foot showing extensive bone marrow abnormalities in navicular, cuboid, lateral cuneiform bones with cortical disruption and soft tissue extension. B) Contrast enhanced T1 showing extensive enhancement of the lesions. C) CT of the foot shows extensive masses in the tarsalia of the right foot. D) Fused with FDG-PET displays intense FDG-uptake in the tarsal masses. E) MIP of the FDG-PET shows additional metastasis in the right tibia, right femur, right lung and possible in the right iliopsoas muscle.

A biopsy in April 2025 confirmed metastatic carcinoma, with immunohistochemistry consistent with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. FDG PET-CT revealed intense uptake in the right foot lesion and additional FDG-avid lesions in the right femur, fibula, and second metatarsal (Fig. 1). Other findings included a hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule and increased uptake near the right iliopsoas muscle adjacent to the acetabulum, consistent with further metastatic spread or post-radiation changes.

The case was reviewed in a multidisciplinary tumor board. Chemotherapy was recommended, and external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) was offered as palliative treatment for symptom control. The radiotherapy regimen consisted of 10 × 3 Gy aimed at the right foot for pain relief. She initially began EBRT but discontinued due to side effects and opted for best supportive care, including analgesia, mobility aids, and close oncologic follow-up.

3. Discussion

Bone metastases (BM) from endometrial carcinoma are uncommon, with an incidence below 1 %. In general, BM most commonly affect the axial skeleton (Uccella et al., 2013). However, in another review, localization of BM were mainly reported in the appendicular skeleton (Heidinger et al., 2023). Metastases to the foot bones are exceptionally rare. As far as we know, 7 cases have been documented thus far, including the present case (Chuang and Wang, 2025, Libson et al., 1987, Zorzi and Pescatori, 1982, Janis and Feldman, 1976, Litton et al., 1991, Cooper et al., 1994).

Foot metastases from endometrial carcinoma occur either as an initial presentation, which is extremely rare, or more commonly after primary treatment, as was the case in our patient. This distribution is consistent with the metastatic behavior of endometrial carcinoma, where initial distant spread favors the lungs, abdomen, pelvis, or spine, and distal skeletal involvement represents a late event. The rarity of foot bone metastases in endometrial carcinoma may be attributed to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of Batson’s venous plexus (Chuang and Wang, 2025, Batson, 1940). This valveless, low-pressure venous network connects the pelvic venous system to the lower extremities, yet it primarily facilitates retrograde hematogenous spread to the axial skeleton, particularly the vertebrae and pelvis. Due to its structural configuration and pressure dynamics, Batson’s plexus is less conducive to the dissemination of tumor cells to distal skeletal sites such as the bones of the foot. Consequently, metastatic involvement of the foot is an uncommon manifestation and, when present, often signifies advanced systemic disease.

Clinically, foot bone metastases may mimic cellulitis, inflammatory arthritis, or neuropathic arthropathy, leading to diagnostic delay. This diagnostic pitfall is well documented for acrometastases in general, regardless of the primary tumor type (Kerin, 1983). Common initial misdiagnoses include cellulitis, gout, and inflammatory joint disease, as local pain, swelling, and erythema can closely resemble benign or infectious conditions (Healey et al., 1986). In our case, the initial suspicion of cellulitis postponed oncologic evaluation. Persistent symptoms unresponsive to standard therapy should prompt further investigation, especially in patients with a cancer history. It is important to note whether there was any history of trauma to the foot in the patient’s recent past. Although trauma is sometimes considered a causative factor in the development of bone metastases, most evidence indicates that these are in fact pre-existing lesions that become symptomatic or are incidentally detected following injury (Athanaselis et al., 2023). In our patient, there was no history of preceding trauma; therefore, there was no indication to perform imaging at an earlier stage.

In endometrial carcinoma, bone metastases are typically managed palliatively, with treatment guided by the extent of systemic disease. Options include systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal agents in hormone receptor–positive tumors), local radiotherapy for pain control, and supportive measures to maintain mobility and quality of life (Heidinger et al., 2023, Salamanna et al., 2021). In our patient, multiple osseous and visceral metastases precluded curative intent; external beam radiotherapy was started for local symptom relief but discontinued due to side effects, after which best supportive care was pursued.

4. Conclusion

Metastases to the bones of the foot from endometrial carcinoma are rare and can mimic infection. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for unusual metastatic patterns in patients with persistent musculoskeletal symptoms and a history of high-risk endometrial cancer. Timely imaging and histologic confirmation are critical for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management, especially as such presentations often indicate advanced systemic disease.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tessel Speelman: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Suzanne Otten: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Meta Tjeenk Willink: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Jasper Helthuis: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Natascha M. de Lange: Writing – review & editing. Harm H. de Haan: Writing – review & editing. Arnold-Jan Kruse: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Financial support

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Athanaselis E., Koskiniotis A., Sourmenidi A., Konstantinou E., Zacharouli K., Hantes M., Karachalios T., Varitimidis S. Is there an association between trauma and musculoskeletal tumours? A review of the literature. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2023;19:149–155. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10080-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson O.V. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann. Surg. 1940;112:138–149. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194007000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang T.-L., Wang Y.-F. Atypical foot swelling in metastatic endometrialcarcinoma: role of FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025;50:64–65. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000005561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.K., Wong F.L., Swenerton K.D. Endometrial adenocarcinoma presenting as an isolated calcaneal metastasis. A rare entity with good prognosis. Cancer. 1994;73:2779–2781. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2779::aid-cncr2820731121>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey J.H., Turnbull A.D., Miedema B., Acrometastases L.JM. A study of twenty-nine patients with osseous involvement of the hands and feet. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1986;68(5):743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidinger M., Simonnet E., Koh L.M., Tirri B.F., Vetter M. Therapeutic approaches in patients with bone metastasis due to endometrial carcinoma; a systematic review. J. Bone Oncol. 2023;41 doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2023.100485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis L.R., Feldman E.P. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the calcaneus: case report. J. Foot Surg. 1976;15:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerin R. Metastatic tumors of the hand. A review of the literature. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1983;65(9):1331–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libson E., Bloom R.A., Husband J.E., Stoker D.J. Metastatic tumours of bones of the hand and foot. A comparative review and report of 43 additional cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16:387–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00350965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litton G.J., Ward J.H., Abbott T.M., Williams H.J., Jr Isolated calcaneal metastasis in a patient with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1991;67:1979–1983. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1979::aid-cncr2820670726>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menczer J. Endometrial carcinoma. Is routine intensive periodic follow-up of value? Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2000;21(5):461–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamanna F., Perrone A.M., Contartese D., Borsari V., Gasbarrini A., Terzi S., De Laco P., Fini M. Clinical characteristics, treatment modalities, and outcomes of bone metastases from gynecological cancers: a systematic review. Bone metastases of endometrial carcinoma were most frequently treated palliatively with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Diagnostics. 2021;11(9):1626. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11091626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.L., Kratzer T.B., Giaquinto A.N., Sung H., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025;75(1):10. doi: 10.3322/caac.21871. Epub 2025 Jan 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccella S., Morris J.M., Bakkum-Gamez J.N., Keeney G.L., Podratz K.C., Mariani A. Bone metastases in endometrial cancer: report on 19 patients and review of the medical literature. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013;130:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi R., Pescatori E. Metastasis of endometrial carcinoma to the tarsus (in Italian) Chir. Organi Mov. 1982;68:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]