Abstract

Cellular senescence is a fundamental driver of ageing and age-related diseases, characterized by irreversible growth arrest and profound epigenetic alterations. While long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as key regulators of senescence, their potential for senescent cell rejuvenation remains unexplored. Here, we identify the ageing-associated lncRNA PURPL as an epigenetic regulator that controls cellular rejuvenation through H3K9me3-mediated transcriptional silencing. CRISPRi-mediated PURPL depletion produces striking rejuvenation effects, resulting in restored youthful cell morphology, as well as suppression of senescence markers such as p21 and SA-β-gal. Conversely, PURPL overexpression accelerates cellular senescence, recapitulating the transcriptional and phenotypic hallmarks of ageing. Mechanistically, nuclear-localized PURPL regulates H3K9me3 deposition at 411 genomic loci including SERPINE1 (PAI-1) and EGR1, which are key senescence drivers. PURPL-mediated H3K9me3 loss at these loci derepresses their transcription, establishing a pro-senescence gene expression program. These findings reveal that PURPL is an epigenetic modulator of senescence and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target for age-related pathologies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-07208-5.

Keywords: Cellular senescence, Long non-coding RNA, PURPL, Histone modification, H3K9me3

Introduction

Ageing is an unavoidable biological process that affects all organisms, with cellular senescence serving as a key mechanism underlying this phenomenon. Cellular senescence is a state of terminal growth arrest characterized by genomic instability, telomere attrition, and epigenetic alterations [1, 2]. Phenotypically, senescent cells exhibit an enlarged, flattened morphology and elevated senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity [3]. At the molecular level, growth arrest is mediated primarily by the upregulation of the cell cycle inhibitors p16 and p21. Specifically, p16 (encoded by CDKN2A) induces cellular senescence by inhibiting CDK4/6, thereby preventing Rb phosphorylation and E2F-mediated cell cycle progression. In contrast, p21 (encoded by CDKN1A) promotes genomic integrity and cell cycle arrest by inhibiting CDK1/2 activity [4, 5]. Another marker of cellular senescence is lamin B1 (encoded by LMNB1), a nuclear protein critical for maintaining nuclear architecture, DNA replication, and cell cycle regulation, whose loss is a hallmark of senescent cells [6]. Additionally, the process of cellular senescence is accompanied by alterations in epigenetic modifications, such as reduced trimethylation of H3K9 and H3K27 [7]. The accumulation of senescent cells can result in a decline in tissue function and development of age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic conditions and cancers [8, 9]. Consequently, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying cellular senescence is crucial for developing strategies to slow ageing and intervene in associated health issues.

Current strategies aimed at addressing the hallmark features of cellular senescence encounter several significant challenges. Although targeted clearance of p16- or p21-positive senescent cells in mice ameliorates and delays ageing-associated disorders, including increased muscle fibre diameter and prevention of osteoporosis [10, 11], the inherent heterogeneity of senescent cell populations allows certain subpopulations to evade elimination [12]. Epigenetic reprogramming, including heterochromatin loss marked by reduced levels of repressive histone modifications such as H3K9me3, occurs during ageing [13]. Experimental studies in animal models have demonstrated that the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) can reverse epigenetic ageing and restore functions in retinal and muscular tissues [14], while telomerase (TERT) gene therapy has been shown to extend murine lifespan by 24% [15]. However, these interventions raise concerns regarding the potential loss of cellular identity and increased oncogenic risk. Heterochronic parabiosis experiments have revealed that youthful blood factors such as GDF11 and TIMP2 can reverse brain atrophy and muscle degeneration in aged mice; however, the reliance on plasma from young donors poses ethical dilemmas and exhibits only transient efficacy [16, 17]. Pharmacological approaches targeting metabolic pathways, such as rapamycin (which inhibits mTORC1) and metformin (which activates AMPK), have demonstrated geroprotective effects but may also lead to risks of immune modulation and disruption of the gut microbiota, respectively [18, 19]. Crucially, the long-term safety profiles of these interventions remain largely undefined.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play essential roles in disease pathogenesis by regulating gene expression, mediating epigenetic modifications, and facilitating signalling crosstalk [20–23]. RNA-based therapeutics, such as small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), present several advantages: they can bypass the limitations of “undruggable” protein targets; they offer enhanced specificity through Watson–Crick base pairing, leading to minimal off-target effects when compared with small molecules; and they do not integrate into host genomes, thus avoiding the permanent mutagenesis risks associated with CRISPR-based gene editing. Recent evidence suggests the substantial involvement of lncRNAs in cellular senescence. For example, the depletion of long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1) RNA in progeroid fibroblasts via antisense oligonucleotides resulted in the restoration of repressive histone epigenetic marks (e.g., H3K9me3 and H3K27me3), reversal of DNA methylation age, and mitigation of senescence-associated phenotypes, demonstrating that targeting LINE-1 can effectively counteract key hallmarks of premature ageing [24]. Additionally, Zhang et al. demonstrated that the inhibition of KCNQ1OT1 induces the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci, activates transposons, and promotes retrotransposition. Their findings revealed that KCNQ1OT1 acts as a critical regulator of genomic stability by maintaining the epigenetic silencing of repetitive DNA elements, preventing their activation and the detrimental consequences of retrotransposition, which are hallmarks of cellular senescence [25]. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting senescence-associated lncRNAs and highlight the need for the systematic exploration of additional lncRNA candidates implicated in the ageing process.

Based on the well-documented role of long non-coding RNAs in gene regulation and their emerging connections to ageing, this study sought to identify key senescence-associated lncRNAs that drive cellular rejuvenation through epigenetic regulation. These lncRNAs may represent novel therapeutic targets for interventions designed to delay ageing and treat age-related diseases.

Methods

Cell culture and senescence induction

Human skin fibroblast (BJ), Human embryonic lung fibroblast (IMR-90), and Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from GuangZhou Jennio Biotech Co., Ltd. Human renal epithelial cells (HEK293T) were purchased from ATCC. All cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, New Zealand). Incubated in a humidified chamber at 37 °C supplemented with 5% CO2.

To establish the replications senescent cell model, human fibroblasts BJ and IMR-90 cells were passaged until they could no longer divide. The cells of different passages were collected for phenotypic and transcriptional analysis.

To establish doxorubicin (DOX)-induced senescence model, BJ cells either left untreated or treated with 50 ng/mL doxorubicin hydrochloride were incubated for 48 h, respectively in a humidified chamber at 37 °C supplemented with 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed with fresh additives after doxorubicin incubated. Cells were collected before and after drug treatment for phenotypic and transcriptional analysis.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity

Cell senescence was assessed using the Cell Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 25% confluency and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, the culture medium was aspirated, and cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To fix the cells, 1 mL of fixation solution was added to each well, and cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. After fixation, the solution was aspirated, and the cells were washed three times with PBS under gentle agitation (3 minutes per wash). Subsequently, 1 mL of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining solution (pH 6.0) was added to each well. The plates were sealed with parafilm to prevent evaporation and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a non-CO2 humidified incubator. Senescent cells were identified by the presence of blue cytoplasmic staining upon visualization under a light microscope.

RNA extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (15596018, Invitrogen) from cultured cells. For RNA-seq library preparation, poly (A)+ RNA was selected using the NEB-Next Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB, E7490L) to perform the LM-seq procedure. including that isolated mRNA is fragmented in reverse transcription buffer with heat and then reverse-transcribed with SmartScribe reverse transcriptase (Clontech) using a random hexamer oligo (HZG883). After reverse transcription, RNA is removed by RNaseA and RNaseH treatment. A partial adaptor (HZG885) is then ligated to the single stranded cDNA using T4 RNA ligase 1 (NEB) and incubated overnight at 22 °C. After purification, ligated cDNA is amplified by 18 cycles of PCR using oligos that contain full BGI adaptors. Last, the resultant libraries were purified using the DNA Clean Beads, followed by sequencing using the DNBSEQ-T7 PE150 platform (Biopharmaceutical PublicService Platform, Nanjing).

RNA-seq data analysis

For RNA-seq analysis, quality control of the raw data was performed using FastQC (v0.11.9). Sequencing adapters were subsequently removed using Cutadapt (v3.3). The trimmed reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg38 (GRCh38.p13) using HISAT2 (v2.1.0) with default parameters. The aligned reads were converted to BAM format and sorted using SAMtools (v1.11). The sorted aligned reads were quantified using Subread featureCounts (v2.0.1) based on the GENCODE v40 annotation. Genes with a total raw count greater than 18 across the three replicates in both the treatment and control groups (i.e., an average of at least 3 counts per sample) were retained for further analysis to filter out lowly expressed genes. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) using DESeq2 (v1.34.0) with threshold: log2-transformed fold change ≥ 0.75 and Adjust P-values < 0.05. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) were performed using DESeq2’s plotPCA package. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler (v4.8.3) and org.Hs.eg.db (v.3.17.0) packages. Visualization was generated using ggplot2 (v3.5.1) package. To perform cluster analysis, gene expression levels of BJ samples at different passages were normalized using DESeq’s Relative Log Expression (RLE) method. Protein coding genes were removed, retaining only non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Lowly expressed ncRNAs and those with duplicated gene symbols were subsequently filtered out. K-means clustering was then performed on the expression profiles of the remaining ncRNAs. Heatmaps were generated using the ComplexHeatmap (v2.16.0) package.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktails (04693132001, Roche) and pipetted 20 times to break down genomic DNA. Then the extracts were mixed with loading buffer and run on a 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane (ISEQ00010, Millipore). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in TBST, the membranes were then incubated with the primary antibodies and followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)—linked secondary antibodies (M21002, Abmart). The signals were detected by western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (WBKLS0100, Millipore) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The GAPDH (10494–1-AP, proteintech), lamin B1 (proteintech, 12987–1-AP), p21 (proteintech, 10355–1-AP), p16 (proteintech, 30,519–1-AP), H3K9me3 (abcam, ab8898), H3 (proteintech, 17168–1-AP) were used in this assay.

CRISPR-Cas9 mediated knockdown and Lentiviral-mediated overexpression of Gene

pLV hU6-sgRNA hUbC-dCas9-ZIM3-KRAB-P2A-EGFP-T2a-Puro vector was used for CRISPR KD experiments. sgRNAs, which were designed for each locus with the https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/design tool, were cloned into pLV hU6-sgRNA hUbC-dCas9-ZIM3-KRAB-P2A-EGFP-T2a-Puro vector [26]. Human PURPL cDNA (Gene ID: 643401) was cloned into TK-PCDH-CMV-copGFP-T2A-Puro for overexpression experiments. TK-PCDH-CMV-copGFP-T2A-Puro was piovided from Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The sequences of sgRNAs used in this study and all genotyping primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Lentivirus production and cell transduction

For lentiviral production, 293T cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes in complete DMEM medium (Gibco) 24 h prior to transfection. At ~70% confluency, 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid mixture containing 4 μg transfer plasmid, 2 μg psPAX2 packaging plasmid (Addgene #12260), and 1 μg pMD2.G envelope plasmid (Addgene #12259) in 1 mL Opti-MEM (Gibco) using 21 μg polyethylenimine (PEI, Polysciences). The DNA-PEI complex was incubated at room temperature for 15 min before adding to cells. After 12–24 h, the medium was replaced with 10 mL fresh, pre-warmed antibiotic-free DMEM. Sodium butyrate (10 mM final concentration) was added 24 h post medium change to enhance viral production. Viral supernatants were collected at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection, centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min, and filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF filters (Millipore). The pooled supernatants (~12 mL) were mixed with 3 mL PEG8000 (Sigma) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Viruses were concentrated by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C (slow acceleration/deceleration). The pellet was resuspended in 150 μL Opti-MEM, aliquoted (50 μL), and stored at −80 °C. For cell transduction, target cells were seeded in 6-well plates in antibiotic-free medium 24 h prior to infection. At ~50% confluency, cells were incubated with viral supernatant (20–40 μL) and 20 μL HitransG P (REVG005) in 0.5 mL Opti-MEM for 8–12 h, followed by replacement with complete medium. Cells were split 1:2 at 48 h post-transduction for selection or cryopreservation.

Subcellular fractionation

To determine the cellular localization of PURPL, we were isolated cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA. Approximately 4 × 107 cells per experimental condition were gently washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of hypotonic CE buffer (approximately 100 µL) and incubated on ice for 3 minutes to lyse the plasma membrane. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was transferred to a fresh tube (CE tube). The nuclear pellet was washed once with 100 µL of detergent-free CE buffer. Then remove residual insoluble material by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. The clarified supernatants, corresponding to the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, were transferred to new tubes. Total RNA was immediately extracted from both fractions, reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and the expression levels of target lncRNAs, including PURPL, were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT‒PCR). The efficacy of the fractionation was validated using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA and the long non-coding RNA Nuclear Paraspeckle Assembly Transcript 1 (NEAT1) as cytoplasmic and nuclear enrichment controls, respectively, confirmed by qRT‒PCR.

ChIP assay and ChIP-sequencing

ChIP assays were carried out as previously described [27]. Briefly, BJ cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde (F8775, Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature, and a final concentration of 125 mM glycine was used to quench the reaction. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and collected in cold PBS by scraping, then resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, with 10 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT and a protease inhibitor cocktail (04693124001, Roche)). The pellet of nuclei was resuspended in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and Protease Inhibitor). Nuclear extracts were sonicated to generate chromatin fragment on a Covaris M220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Insert, microTUBE 130 µL; Temperature, 7 °C; Peak Incident Power, 75 W; Duty Factor, 5%; Treatment Time, 300 s). The chromatin was cleaned by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and diluted with 1 mL RIPA buffer per reaction. Then the chromatin was precleared with Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (17061801, GE) for 2 hours, 30 µL of sample was set aside as an input and subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody against H3K9me3 (abcam, ab8898) overnight. On the following day, Pierce Protein A/G Plus Agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 20,423) that were blocked with RIPA containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added into the samples followed by incubation for 2 hours in cold room under rocking. The beads were then washed three times with RIPA buffer, followed by two times in RIPA buffer with 0.5 M NaCl, oncein LiCl buffer [250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630,0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0)], and twice in ice-cold Tris- EDTA (TE) buffer. Each time, the beads were sustaining for 5 min with a gentle rock. After washing, both the beads and input sample were added with 150 μL of extraction buffer (1% SDS in 1× TE, 12 μL of 5 M NaCl, and 10 μg of RNAse A) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour with a shaking. Next, 20 μg of Proteinase K was added to the samples for incubation at 65° C overnight with thermoshaking. DNA was isolated by performing a phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction to prepare the ChIP-seq library using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumi-na (NEB, E7645). The library was sequenced using the DNBSEQ-T7 PE150 platform (Biopharmaceutical PublicService Platform, Nanjing).

ChIP-seq data processing

For ChIP-seq analysis, quality control and removal of sequencing adapters were same as RNA-seq. The trimmed reads were aligned to the reference genome hg38 (GRCh38.p13) using Bowtie2 (v2.4.2) with default parameters. PCR duplicates were removed using GATK MarkDuplicates (v4.1.9.0). Peaks were then called using MACS2 (v2.2.9.1) with the parameters: macs2 callpeak -f BAMPE -g hs –broad –broad-cutoff 0.1. To identify differential peak regions, we used MACS2 with the parameter: macs2 bdgdiff -C 2. Subsequently, we performed enrichment analysis on the differential peaks using the R package Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (rGREAT, v2.2.0). Biological replicates’ BAM files were merged and then converted to BigWig files using deepTools (v3.5.1) with the parameters: bamCoverage -bs 10 –normalizeUsing CPM. BigWig files were visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, v2.16.1).

Quantitative real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (15596018, Invitrogen) from cultured cells and was reversely transcribed into cDNA (R212, Vazyme) and then subjected to RT‒qPCR using a ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q711, Vazyme). Expression of each gene tested in this study was normalized to that of ACTB (β-actin). p value was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. The primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Identification of PURPL RNA-Binding proteins using CARPID 2.0 assay

The CARPID 2.0 assay was employed to identify PURPL RNA-binding proteins. The APEX2–miniCas13X.1 fusion protein was expressed in E. coli and purified. A set of PURPL-specific gRNAs was synthesized by IDT. BJ cells were seeded in 10 cm plates (50–70% confluency) and transfected with Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# CMAX00008). For transfection, 5 μg APEX2–miniCas13X.1 and 1 μg gRNA were mixed in 100 μL Opti-MEM (tube 1), while 6 μL CRISPRMAX was diluted in 100 μL Opti-MEM (tube 2). The two solutions were combined, incubated for 5–10 min at room temperature, and added to the cells. After 1 h at 37 °C, cells were washed with PBS and incubated in medium containing 500 μM biotin-phenol (APEXBIO, Cat# A8011) for 30 min at 37 °C. Proximity biotinylation was induced with PBS containing 500 μM biotin-phenol and 1 mM H₂O₂ for 1 min, followed by quenching with PBS supplemented with 5 mM Trolox and 10 mM sodium ascorbate (3 washes). Cells were collected for RNA and protein extraction.

RNA extraction and enrichment: Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 15,596,018) after brief sonication and separated with chloroform. The aqueous phase was mixed with ethanol and 2 μL glycogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 10814010) for precipitation. Biotinylated RNA was enriched using streptavidin Dynabeads, pre-washed three times in B&W buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) and incubated for 2 h with 5 μL Superase-in (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# AM2696). Beads were washed three times with B&W buffer, and bound RNAs were eluted with TRIzol for downstream qPCR validation of gRNA specificity.

Protein enrichment and digestion: Following gRNA validation, biotinylated BJ cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40) supplemented with 10 mM sodium ascorbate, 5 mM Trolox, 50 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors. Lysates were sonicated, clarified (16,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C), and incubated overnight at 4 °C with pre-washed streptavidin beads. Beads were washed three times with ice-cold RIPA buffer, and proteins were either eluted with 2 × loading buffer containing 40 μM biotin for immunoblotting or processed by on-bead digestion. For digestion, beads were washed three times in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0), then incubated in 50 μL elution buffer I (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 2 M urea, 10 μg/mL trypsin, 1 mM DTT) at 30 °C for 1 h. Supernatants were collected, beads washed twice in elution buffer II (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 2 M urea, 5 mM iodoacetamide), and combined. An additional 0.25 μg trypsin was added, and digestion proceeded overnight at 32 °C. The eluates (100 μL) were quenched with 4 μL 10% formic acid and desalted with C18 tips (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 87784).

Mass spectrometry and data analysis: Samples were reconstituted in 20 μL of 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and analyzed by nanoLC coupled to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher). Raw data were processed using MaxQuant (v2.4.2.0), and “proteinGroups.txt” files were used for downstream analysis. Statistical evaluation was performed with the DEP R package (v1.26.0), including data preparation, normalization, imputation (MinProb method), and differential enrichment analysis. Significantly enriched RBPs were defined by p < 0.05 and fold change > 2.

Results

Establishment and characterisation of senescent fibroblast cell model

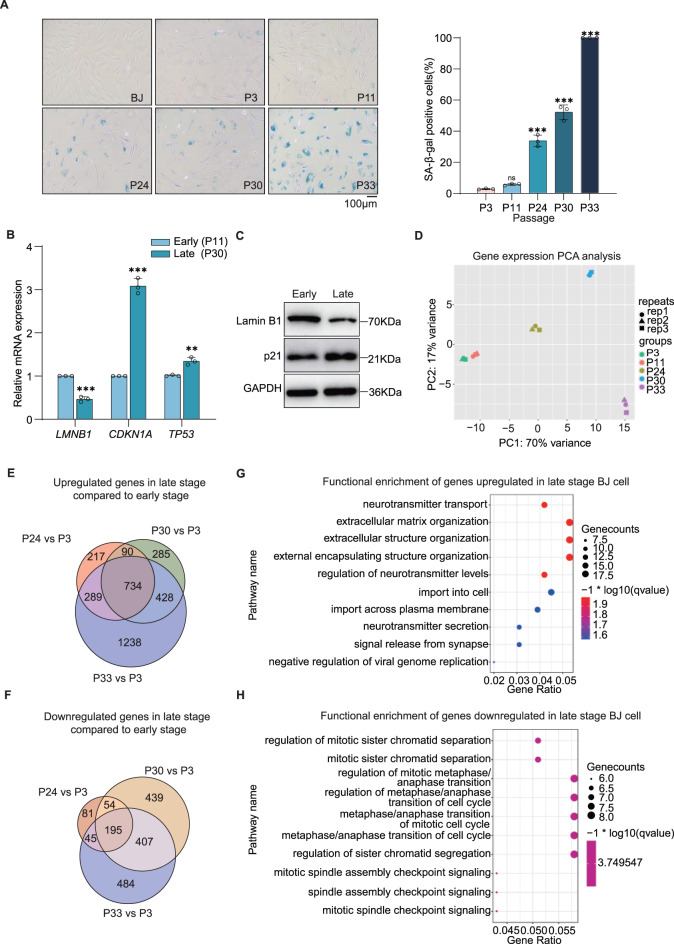

To establish the senescent cell model, we utilized the strategies of both cellular replication in BJ and IMR-90 human fibroblasts and doxorubicin-induced DNA damage in BJ cells. Along the increasing cell replication (i.e., P3, P11, P24, P30, and P33), the BJ cells underwent a transition from a typical fibroblast cell morphology to a flattened, rounded appearance. Moreover, the passaged cells exhibited a progressive and significant increase in SA-β-gal activity, a widely-recognized standard for determining cellular senescence, confirming the gradual transition to a senescent state (Fig. 1A). According to the activity of SA-β-galactosidase, cells in early passages, i.e., P3 and P11, remained young, while late-passage cells, i.e., P30 and P33, became senescent, with P24 cells in an intermediate state.

Fig. 1.

Replicative senescence characterization in BJ human fibroblasts. (A) Left: Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining in BJ cells at different passages (P3, P11, P24, P30 and P33), scale bar, 100 μm. Right: quantification analysis of SA-β-gal-positive cells at different passages (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ns, not significant, ***p < 0.001). (B, C) senescence-associated marker expression in young (P11) and senescent (P30) BJ cells. B, RT‒qPCR quantification of LMNB1, CDKN1A (p21), and TP53 mRNA levels (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). C, Immunoblot analysis of LMNB1 and p21 protein expression, GAPDH serves as loading control. (D) Principal component analysis (PCA) of transcriptomes profiles from BJ cells at indicated passages (P3–P33), with shapes denoting biological replicates. (E–H) Transcriptomic changes during senescence. Venn diagrams depict numbers of upregulated (E) and downregulated (F) genes in late stages (P24–P33) versus early stage (P3) (up, Padj < 0.05, log2FC > 1; down, Padj < 0.05, log2FC < -1). Bubble plots show significantly enriched GO terms for upregulated ( G) and downregulated (H) genes in late stage BJ cell. Replicative senescence characterization in IMR-90 human fibroblasts. (A) Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining in IMR-90 cells at different passages (P5, P9, P11, and P13), scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Quantification analysis of SA-β-gal-positive cells at different passages (Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (C, D) Senescence-associated marker expression in young (P5) and senescent (P13) IMR-90 cells. C, RT‒qPCR quantification of LMNB1, CDKN2A (p16) mRNA levels (Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, **p < 0.01, ***p< 0.001). D, Immunoblot analysis of LMNB1 and p16 protein expression, GAPDH serves as loading control

At the molecular level, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‒qPCR) verified that the change in expression of ageing-related biomarker genes was expected. For example, the expression of CDKN1A/p21 (a tumour suppressor or antioncogenic protein) and TP53/p53 (a tumour suppressor protein that activates CDKN1A/p21 to halt cell cycle progression) [28], two key mediators of cell cycle arrest, were dramatically elevated in senescent cells (P30) compared to young cells (P11), whereas the expression of LMNB1 was downregulated (Fig. 1B). Western blot results demonstrated the same trend of changes in the protein levels of these biomarkers during cellular senescence, further confirming the success of establishing the senescent state of the BJ cells (Fig. 1C). At the transcriptome level, RNA sequencing of BJ cells at different passages was performed, and principal component analysis (PCA) clearly distinguished these cells according to their degree of senescence. PCA also revealed that the expression patterns of the young cells in P3 and P11 were similar, which is consistent with the results of the SA-β-gal activity analysis (Fig. 1D).

To systematically identify genes and pathways that drive the cellular senescence, we performed a comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between intermediate- to late-passage cells (P24, P30, P33) and early-passage cells (P3). Notably, 734 genes exhibited persistent upregulation accompanying cellular division (Fig. 1E), while 195 genes remained consistently downregulated (Fig. 1F). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis highlighted that the upregulated genes were primarily involved in biological processes such as neurotransmitter transport and extracellular matrix remodelling (Fig. 1G), whereas senescence-driving depleted genes were enriched for function related to regulation of mitosis and cell cycle (Fig. 1H). These results were highly consistent with the characteristics of cellular ageing, particularly the organization of the extracellular matrix, a characteristic recently recognized as an ageing hallmark feature [29]. To determine whether these findings represent conserved ageing mechanisms across cell types, we also established an IMR-90 replicative senescence model that recapitulated key features of cellular ageing, including increased SA-β-gal activity and altered expression of senescence markers (Extended Data Fig. 1A–D). In summary, we successfully constructed two senescent cell models, which are of great importance for studying the mechanism of cell ageing.

PURPL depletion can rejuvenate senescent cells

Having characterized the senescent phenotype in both models, we next analyzed the genes associated with senescence, with potentials as a target to rejuvenate senescent cells. Here, we focused on non-coding RNA genes, particularly lncRNAs, as previous studies had indicated their role in driving cellular senescence [24, 25]. We conducted comparative analyses of differentially expressed lncRNAs between intermediate- and late-passage cells (P24, P30, P33) and early-passage cells (P3 and P11) and identified 1,629 genes that were differentially expressed between the different ageing stages of BJ cells. Subsequent hierarchical clustering of these genes revealed that 435 lncRNAs were continuously upregulated during replicative ageing (Cluster 4) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S2). In parallel, we also conducted comparative analyses of differentially expressed lncRNAs between intermediate- to late-passage cells (P9, P11, P13) and early-passage cells (P5) and identified 805 genes that were differentially expressed between the different ageing stages of IMR-90 cells. Subsequent hierarchical clustering of these genes revealed that 227 lncRNAs were continuously upregulated during replicative senescence (Cluster 3) (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Identification and functional validation of senescence-associated lncRNA PURPL. (A, B) cluster analysis of differentially expression lncRNAs across BJ cell passages (P3–P33) or IMR-90 cell passages (P5–P13). Z-scores indicate relative expression levels (red: high; blue: low). (C) Venn diagram displays the number of common lncRNAs identified by BJ-Cluster4 upregulation lncRnas (left, n = 435), IMR-90-Cluster3 upregulation lncRNAs (middle, n = 227), and doxorubicin-induced upregulation lncRNAs (right, n = 94). (D) Tissue-specific expression profiles of PURPL in bladder and sigmoid colon across age groups (20–79 years). Expression levels are presented as log2(TPM). (E) RT‒qPCR validation of CRISPRi-mediated PURPL knockdown efficiency (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (F, G) senescence marker expression after PURPL knockdown. F, qRT‒PCR quantification of LMNB1, CDKN1A (p21) mRNA levels (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). G, Immunoblot analysis of LMNB1 and p21 protein expression, GAPDH serves as loading control. (H) SA-β-gal staining and quantification of empty vector control (sgCtrl) and PURPL knockdown (sgPURPL#1/2) BJ cells (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 6, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001), scale bar, 100 μm. Doxorubicin-induced senescence in BJ human fibroblasts. (A) Left: SA-β-gal staining of BJ cells treated with DMSO (control) or 50 ng/mL doxorubicin (Dox). Scale bar, 100 μm. Right: Quantification of SA-β-gal-positive cells at treated with DMSO or 50 ng/mL Dox (Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (B) RT‒qPCR analysis of senescence marker mRNA expression post-Dox treatment (Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (C) Volcano plot of differentially expressed lncRNAs following Dox treatment. Upregulated lncRNAs are marked in red dots, while downregulated lncRNAs are highlighted in blue

To identify high-confidence candidates, we also established a DOX-induced senescence model, which recapitulated key features of cellular ageing, including increased SA-β-gal activity and altered expression of senescence markers (Extended Data Fig. 2A–C). In the DOX-induced model, 94 lncRNAs were significantly upregulated in cells upon DOX treatment (Supplementary Table S4). By intersecting senescence-associated genes from the three cell models, 3 lncRNAs were commonly upregulated (Fig. 2C), among which lncRNA PURPL exhibited the highest basal expression level and prior associations with ageing, making it the most promising candidate for functional validation (Extended Data Fig. 3A), Supplementary Table S5. In addition to human skin fibroblasts (BJ) and human embryonic lung fibroblasts (IMR-90), increased expression of PURPL has been consistently observed in other human cell types, such as umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), during their senescence process [30, 31]. More interestingly, we examined the GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) data, a public resource providing age-stratified transcriptomic profiles across diverse human tissues. We discovered that the expression level of PURPL was positively correlated with human age in diverse human tissues, such as bladder, sigmoid colon, spleen, and uterus (Fig. 2D, Extended Data Fig. 3B), highlighting its potential to regulate senescence-related phenotypes during the ageing process.

Fig. 3.

PURPL overexpression accelerates cellular senescence. (A) RT‒qPCR analysis showing increased PURPL expression in BJ cells post-overexpression (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (B, C) senescence marker expression after PURPL overexpression. B, RT‒qPCR quantification of LMNB1, CDKN1A (p21) mRNA levels (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). C, Immunoblot analysis of LMNB1 and p21 protein expression, GAPDH serves as loading control. (D) SA-β-gal staining of ctrl and PURPL-overexpressing cells. Left: SA-β-gal staining in PURPL-overexpressing (PURPL#1/2-OE) compared to empty vector control (ctrl) BJ cells, scale bar, 100 μm. Right: quantification shows significantly increased SA-β-gal-positive cells upon PURPL overexpression (data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 6, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, ***p < 0.001). (E) Volcano plot illustrating mRNA enrichment in PURPL#1 overexpressing BJ cells. Upregulated mRNAs are marked in red dots, while downregulated mRNAs are highlighted in blue. (F, G) bubble plot showing enriched GO biological process terms for up (F) and downregulated (G) genes in BJ cells overexpressing PURPL (PURPL#1-OE) compared to empty vector control (ctrl). Senescence-Associated lncRNA PURPL: Expression Dynamics and CRISPRi Targeting Strategy. (A) Expression dynamics of senescence-upregulated lncRNAs across BJ cell passages (P3–P33). Data show normalized counts ± s.d. (B) Tissue-specific expression profiles of PURPL in spleen and uterus across age groups (20–79 years). Expression levels are presented as log2(TPM). (C) Schematic of CRISPRi-mediated PURPL knockdown strategy

PURPL has been reported to promote cancer cell proliferation in colorectal cancer by suppressing p53 levels and in cutaneous melanoma by regulating ULK1 phosphorylation [32, 33]. However, whether PURPL plays a driving role in cellular senescence remains unclear. To investigate and elucidate this, we depleted its expression and assessed whether the senescent cells could be rejuvenated. Because PURPL has more than 100 isoforms (according to GeneCards), we leveraged CRISPR/Cas9 interference (CRISPRi) to target its transcription start site (TSS) so that we could simultaneously deplete most of these transcripts. We designed guide RNAs (gRNAs) and performed CRISPRi in BJ cells of P24 passage (Extended Data Fig. 3C). RT‒PCR analysis verified that PURPL expression was significantly downregulated when the CRISPRi system was stably expressed (Fig. 2E). Indeed, knockdown of PURPL significantly reversed the senescent phenotypes, as evidenced by significant changes in both RNA and protein levels of senescence-related biomarkers. Specifically, we observed a pronounced upregulation of LMNB1 expression concurrent with a substantial suppression of p21 levels, as evidenced by the use of two different sgRNA designs (Fig. 2F, G). In addition, we also observed a marked attenuation of SA-β-galactosidase activity upon depleting PURPL (Fig. 2H). Taken together, these findings suggest that PURPL plays a driver role in promoting cellular senescence.

PURPL overexpression accelerates cellular senescence of young cells

A previous study reported a significant positive correlation between the PURPL RNA level and ageing in human tissues [34]. The observed rejuvenation effect of senescent BJ cells by PURPL knockdown prompted investigation into whether its upregulated expression might accelerate senescence. To test this hypothesis, we ectopically expressed two different isoforms of PURPL in young BJ cells which exhibited low expression of PURPL (Fig. 3A). As anticipated, overexpression of PURPL triggered strong senescence-associated phenotypes, including significant downregulation of LMNB1, upregulation of p21, and an increase in SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 3B–D).

Transcriptomic profiling of control and PURPL-overexpressing BJ cells revealed distinct gene expression patterns, with two clearly segregating groups in the primary dimension (Extended Data Fig. 4A). RNA-seq analysis revealed that PURPL overexpression significantly altered the expression of 1,633 genes, with 561 upregulated genes and 1,072 downregulated genes (Fig. 3E). GO enrichment analysis demonstrated that the upregulated genes were primarily involved in biological processes such as cell differentiation and extracellular matrix organization, whereas the downregulated genes were predominantly enriched in processes related to nuclear division (Fig. 3F, G). This finding is consistent with the pathways activated and repressed by cell replication-driven senescence (Fig. 1G, H), indicating that overexpression of PURPL alone could be sufficient to drive cellular senescence. Notably, overexpression of PURPL in another isoform induced similar phenotypical changes, further substantiating the functional role of PURPL in cellular senescence (Extended Data Fig. 4B–D).

Fig. 4.

Mechanistic insights into PURPL function. (A) Subcellular localization of PURPL by qPCR. NEAT1 (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytoplasmic) serve as controls. (B) The venn diagram displays the number of common lncRNAs identified by H3K9me3-associated lncRNAs (left, n = 394), BJ doxorubicin-induced upregulation lncRNAs (middle, n = 94), and BJ-Cluster4 upregulation lncRNAs (right, n = 435). (C) Immunoblot analysis of H3K9me3 levels in PURPL-knockdown (sgPURPL#1/2) BJ cells versus controls (sgCtrl) and PURPL -overexpressing (PURPL#1/2-OE) versus controls (ctrl). H3 serves as loading control. (D) The venn diagram shows the number of common genes by intersecting the list of downregulated genes(n = 757, Padj < 0.05, log2FC < -0.5) and genes proximal to H3K9me3 peak-enriched regions (n = 411) from the PURPL-knockdown (E, F) genome browser shots show the distribution of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq signals from samples of sgCtrl and sgPURPL#1/2, RNA-seq signals from BJ P3 and P33 on SERPINE1 (E) and EGR1 (F) gene. PURPL overexpression functional analyses. (A) PCA of transcriptomes from PURPL-overexpressing (PURPL#1/2-OE) and empty vector control (Ctrl) BJ cells, shapes represent biological replicates. (B) Volcano plot illustrating mRNA enrichment in PURPL#2 overexpressing BJ cells. Upregulated mRNAs are marked in red dots, while downregulated mRNAs are highlighted in blue. (C, D) Bubble plot showing enriched GO biological process terms for up (C) and downregulated (D) genes in BJ cells overexpressing PURPL (PURPL#2-OE) compared to empty vector control (Ctrl)

PURPL plays a role in epigenetic regulation of gene expression

Cellular senescence is characterized by heterochromatin loss and increased chromatin accessibility, leading to aberrant gene expression [7, 13]. Recent studies have demonstrated that lncRNA can participate in modulating histone epigenetic modifications, thereby regulating gene activity [35, 36]. We first investigated the subcellular localization of PURPL RNA by biochemical fractionation (Extended Data Fig. 5A) and found that PURPL was predominantly concentrated in nuclei (Fig. 4A). Chrom-seq, previously developed in our laboratory, identifies RNAs that are significantly associated with epigenetically modified chromatin loci, such as histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) or histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), depending on the engineered chromatin reader (eCR) used [37]. Given the established characteristic of heterochromatin loss during ageing [13], we referred to RNAs associated with loci enriched in H3K9me3, an epigenetic marker of heterochromatin, obtained from Chrom-seq experiments using CBX1 eCR. By intersecting CBX1 Chrom-seq-captured RNAs with lncRNA upregulated in senescent cells, we identified PURPL as the sole potential epigenetic regulator of senescence (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S6). Western blot analysis confirmed that PURPL knockdown indeed increased H3K9me3 protein levels. In contrast, its overexpression markedly reduced H3K9me3 in cells, confirming that PURPL plays a role in suppressing repressive histone marks (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 5.

Mechanistic model of PURPL-mediated epigenetic regulation in cellular senescence. In proliferating cells, PURPL expression is maintained at low levels. As cells undergo repeated divisions, PURPL is up-regulated and accumulates in the nucleus, where it likely interacts with transcription activators such as ZNF236, facilitating the recruitment of epigenetic modifiers. This process promotes the depletion of the repressive histone mark H3K9me3 at specific genomic loci—including those of senescence-associated genes such as SERPINE1 and EGR1. This epigenetic derepression leads to their transcriptional activation and drives the senescent phenotype, marked by reduced Lamin B1, elevated p21, and increased SA-β-gal activity. Notably, knockdown of PURPL restores H3K9me3 levels at these loci, suppresses senescence-associated gene expression, and facilitates cellular rejuvenation. Subcellular distribution and epigenetic regulation of SERPINE1 and EGR1 by PURPL. (A) Schematic of nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation. (B) RT‒qPCR analysis of PURPL, SERPINE1, EGR1 and LMNB1 expression levels in HUVECs following PURPL overexpression. (Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m., n = 3, p values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (C) Genomic loci and epigenetic profiles of SERPINE1 and EGR1. Track displays include: ReMap ChIP-seq peaks (transcription factor binding sites), H3K27ac histone marks (active enhancer/promoter regions). (D) Identification of PURPL-associated proteins by CARPID. Volcano plot showing enrichment of PURPL-associated proteins in BJ cells. The x-axis shows the log2 fold change in protein enrichment (PURPL gRNAs versus non-targeting gRNA), and the y-axis shows the –log10 p value. Significantly enriched proteins are marked in orange (p-value < 0.05, fold change > 2, and n = 3 independent experiments). The transcriptional activators ZNF236 and MTDH are among the PURPL-associated candidates. N.S., not significant

To elucidate the molecular role of PURPL in cellular senescence, we compared H3K9me3 ChIP-seq peaks before and after PURPL knockdown in BJ cells. The results revealed that there were 411 genomic loci whose H3K9me3 signals significantly increased following PURPL depletion. By intersecting these loci with genes whose expression was downregulated upon PURPL attenuation, we prioritized 11 candidate genes potentially regulated by PURPL-mediated epigenetic repression (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table S7). Among them was SERPINE1 (Serpin Family E Member 1, also known as PAI-1), the primary physiological inhibitor of plasminogen activators synthesized in the liver and adipose tissue. SERPINE1 expression was elevated in senescent cells (Fig. 4E). Upon PURPL knockdown, H3K9me3 signal at the SERPINE1 locus significantly increased, accompanied by a significant repression of SERPINE1 transcription (Fig. 4E). Consistently, genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of SERPINE1 has been shown to prevent senescence-like pathologies and telomere shortening, and to extend lifespan in accelerated ageing mouse models [38]. In addition to SERPINE1, a similar pattern of PURPL-engaged transcriptional repression was also observed for EGR1 (Fig. 4F), a gene previously reported to be elevated in ageing human haematopoietic stem cells [39]. Mice lacking Egr1 also exhibited a striking phenotype with complete bypass of senescence and induced immortal cell growth ability [40]. To further validate the functional role of PURPL beyond fibroblasts, we overexpressed PURPL in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and observed a senescent phenotype characterized by downregulation of LMNB1, along with a marked upregulation of SERPINE1 (Extended Data Fig. 5B). These findings are consistent with previous studies and suggest that the regulatory function of PURPL is not restricted to fibroblasts.

PURPL downregulation results in increased H3K9me3 deposition at these loci, while its overexpression results in a loss of this repressive marker. The high H3K27ac enrichment observed at these regions (e.g., near SERPINE1 and EGR1) indicates that they function as active enhancers (Extended Data Fig. 5C) [41]. The recruitment of chromatin condensation proteins by H3K9me3 directly counteracts this active enhancer state, reducing chromatin accessibility and leading to the transcriptional repression of nearby senescence-driving genes [42]. To further investigate the molecular functions of PURPL, we have conducted CARPID (CRISPR-Assisted RNA-Protein Interaction Detection), a method previously established in our laboratory to identify proteins that interact with a specific RNA in cells. This technology uses the CRISPR/CasRx system to specifically target RNA of interest and enables proximity-labelling of associated proteins, allowing efficient and precise capture of endogenous RNA–protein interactions [43, 44]. Leveraging CARPID method, we isolated a high-confidence cohort of PURPL-interacting proteins, including two transcriptional activators, ZNF236 and MTDH (Extended Data Fig. 5D, Supplementary Table S8, detail see Methods). Collectively, these findings suggest that PURPL confers locus-specific targeting and facilitates chromatin accessibility, potentially via the recruitment of transcriptional activators. A key focus for future work will be to define the precise role of each recruited molecule in the activation of the senescence program.

Discussion

The results of this study have established lncRNA PURPL as a key regulator of cellular senescence, bridging the connection between epigenetic modifications and the transcriptional regulation of senescence-associated genes. Our findings demonstrate that PURPL is significantly upregulated in both replicative senescence and doxorubicin-induced senescence models. Manipulation of PURPL profoundly impacts the senescence phenotype. These findings extend and are consistent with previous studies on ageing regulators such as EGR1, SERPINE1, and other lncRNAs, and provide novel mechanistic insights into how PURPL regulates ageing through epigenetic remodelling, highlighting its significant theoretical and clinical implications.

Although several studies have reported a strong correlation between increased PURPL expression and senescence at both the cellular and tissue levels [30, 31, 34], few have demonstrated causality. Recently, RNAi was used to knock down PURPL expression in senescent cells, resulting in some morphological improvements [45]. However, no changes in molecular markers such as p21 were observed. In this study, we employed a more persistent method of lentivirus-mediated CRISPRi to knock down PURPL. Not only did we observe significant morphological changes, but we also detected decreased levels of CDKN1A/p21 (a tumour suppressor or antioncogenic protein) at both the RNA and protein levels. Furthermore, we overexpressed PURPL in young cells to mimic the increased PURPL levels observed during cellular senescence. This overexpression accelerated cellular senescence, as evidenced by increased SA-β-gal activity, elevated p21 levels, and reduced LMNB1 levels. This study provides the first definitive evidence that PURPL acts as a driver of senescence.

The upregulation of PURPL in senescent fibroblasts is similar to that of other senescence-associated lncRNAs, such as H19 and HOTAIR, which are known to regulate senescence through different pathways. For example, knocking down H19 induces senescence by activating autophagy and inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [45], whereas HOTAIR promotes senescence by activating the NF-κB and p53/p21 pathways [46]. The nuclear localization of PURPL and its association with H3K9me3 highlight its role in epigenetic regulation. We found that knockdown of PURPL increases global H3K9me3 levels, whereas overexpression of PURPL decreases them. This suggests that PURPL acts as an inhibitor of repressive histone marks. This is reminiscent of other lncRNAs, such as KCNQ1OT1, which maintains heterochromatin stability [25], and LINE-1 RNA, whose depletion can restore heterochromatin in progeroid-like cells [24]. Upon PURPL knockdown, specific increases in H3K9me3 were observed at 411 loci, along with downregulation of nearby genes, such as SERPINE1 and EGR1. These findings suggest that PURPL may function as an epigenetic rheostat, finely tuning the expression of senescence-related genes through histone modifications.

RNA therapy represents an emerging therapeutic strategy offering significant advantages over traditional small-molecule drugs, notably high specificity, low toxicity, and the potential for rapid development and production [47]. RNA-based therapeutics have been investigated in preclinical and clinical studies for age-related diseases, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases [48]. A crucial requirement for successful clinical application is the identification of suitable therapeutic targets. The reversibility of PURPLs effects on senescence makes it an attractive lncRNA therapeutic target [49, 50]. Unlike senolytic drugs that indiscriminately eliminate senescent cells, targeting PURPL could offer a more precise strategy to modulate senescence without harming healthy cells. The success of RNA-based therapies, such as ASOs targeting LINE-1 RNA, supports the feasibility of this approach [24]. However, several key issues remain unresolved. First, the precise molecular mechanism by which PURPL inhibits H3K9me3 deposition remains elusive. To address this, we employed CARPID technology and identified ZNF236 as a high-confidence PURPL-interacting protein. Based on previous reports that zinc finger proteins such as Zfp296 can suppress H3K9 methylation [51, 52], we hypothesize that PURPL may serve as a scaffold recruiting ZNF236 to specific genomic loci to negatively regulate H3K9me3 levels and modulate senescence-related gene expression (Fig. 5). However, the precise mechanistic contributions of the recruited molecules, such as ZNF236 or MTDH, in activating senescence-driving genes require further investigation. Second, the tissue specificity of PURPLs action requires further investigation, given the potential heterogeneity in ageing mechanisms across cell types. Notably, we identified SERPINE1 and EGR1 as key downstream effectors of PURPL. Given that SERPINE1 is strongly implicated in pulmonary fibrosis [53] and EGR1 in cardiovascular and haematopoietic ageing [54, 55], targeting PURPL may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for these two classes of age-related diseases. Third, the translational potential of PURPL inhibition necessitates validation in vivo, particularly in models of age-related diseases. PURPL is primarily conserved in humans but exhibits limited sequence homology in common animal models such as mice and zebrafish. It is relatively conserved only in certain non-human primates, such as Cercocebus atys and Chlorocebus sabaeus, so preclinical validation remains particularly challenging. Nevertheless, promising advances have been achieved in some studies utilizing antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) in non-human primate models [56, 57]. Finally, the drug stability and off-target effects of RNA-targeted therapy for PURPL require further in vitro and in vivo studies [48, 58]. Addressing these challenges is critical for advancing targeted therapeutic applications of PURPL. This study establishes a critical foundation for future investigations.

In summary, this study identifies PURPL as a core epigenetic regulator of cellular senescence, acting through H3K9me3-mediated gene repression (e.g., SERPINE1 and EGR1). By integrating previous findings on senescence-associated lncRNAs and epigenetic modifiers, we propose a model in which PURPL functions as a molecular switch, driving senescence by modulating heterochromatin dynamics. These insights not only enhance our understanding of lncRNA-mediated senescence but also pave the way for the development of targeted anti-senescence therapies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following funding sources: Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2302027), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270634), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515012685), Shaanxi Innovation Capability Support Program (2024RS-CXTD-85), the Shaanxi Academy of Fundamental Sciences (Chemistry & Biology) (22JHZ009), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (11101022), Tung Biomedical Sciences Centre and City University of Hong Kong (9609317, 7006043).

Author contributions

J.Y. conceived the project. J.W., X.Y., Y.N., X.S., and W.Y. carried out experiments, W.S., J.W., and J.Y. performed data analysis. J.Y., J.W., X.Y., and Y.N. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The Chrom-seq data used in this study were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) series GSE252810. Mass spectrometry raw data areavailable via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD068664. The raw reads of ChIP-seq, RNA-seq of all cell lines are deposited in GEO, with an accession no. GSE301164, GSE301166, GSE301169. All primer sequences used in this study are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jie Wang, Xiao Yang and Xinyu Su contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yong-Qiang Ning, Email: ningyongqiang@nwu.edu.cn.

Jian Yan, Email: jian.yan@cityu.edu.hk.

References

- 1.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186:243–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Micco R, Krizhanovsky V, Baker D. d’Adda di fagagna F: cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol cellbiol. 2021;22:75–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karimian A, Ahmadi Y, Yousefi B. Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair (amst). 2016;42:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumari R, Jat P. Mechanisms of cellular senescence: cell cycle arrest and senescence associated secretory phenotype. Front. Cell Dev.Biol. 2021;9:645593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freund A, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2066–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Liu X, Du Z, Wei L, Fang H, Dong Q, Niu J, Li Y, Gao J, Zhang MQ, et al. The loss of heterochromatin is associated with multiscale three-dimensional genome reorganization and aberrant transcription during cellular senescence. GenomeRes. 2021;31:1121–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo J, Huang X, Dou L, Yan M, Shen T, Tang W, Li J. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ, van Deursen JM. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. NatMed. 2015;21:1424–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra A, Lagnado AB, Farr JN, Doolittle M, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, LeBrasseur NK, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Ikeno Y, et al. Targeted clearance of p21- but not p16-positive senescent cells prevents radiation-induced osteoporosis and increased marrow adiposity. Aging Cell. 2022;21:e13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahour N, Bleichmar L, Abarca C, Wilmann E, Sanjines S, Aguayo-Mazzucato C. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive cells in a mouse transgenic model does not change beta-cell mass and has limited effects on their proliferative capacity. Aging (albany NY). 2023;15:441–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Kim EW, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Heterochromatin: an epigenetic point of view in aging. Exp MolMed. 2020;52:1466–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y, Brommer B, Tian X, Krishnan A, Meer M, Wang C, Vera DL, Zeng Q, Yu D, Bonkowski MS, et al. Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature. 2020;588:124–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jesus B B, Vera E, Schneeberger K, Tejera AM, Ayuso E, Bosch F, Blasco MA. Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO molmed. 2012;4:691–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagunas-Rangel FA. Aging insights from heterochronic parabiosis models. NPJ Aging. 2024;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piantadosi PT, Holmes A. GDF11 reverses mood and memory declines in aging. Nat Aging. 2023;3:148–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juricic P, Lu YX, Leech T, Drews LF, Paulitz J, Lu J, Nespital T, Azami S, Regan JC, Funk E, et al. Long-lasting geroprotection from brief rapamycin treatment in early adulthood by persistently increased intestinal autophagy. Nat Aging. 2022;2:824–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang E, Jin L, Wang Y, Tu J, Zheng R, Ding L, Fang Z, Fan M, Al-Abdullah I, Natarajan R, et al. Intestinal AMPK modulation of microbiota mediates crosstalk with brown fat to control thermogenesis. NatCommun. 2022;13:1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long Y, Wang X, Youmans DT, Cech TR. How do lncRnas regulate transcription? Sci Adv. 2017;3:eaao 2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL, Huarte M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol cellbiol. 2021;22:96–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu J, Chen J, Yin Q, Dong M, Zhang Y, Chen M, Chen X, Min J, He X, Tan Y, et al. lncrna jpx-Enriched chromatin microenvironment mediates vasc smooth muscle cell senescence and promotes atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024;44:156–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji ML, Li Z, Hu XY, Zhang WT, Zhang HX, Lu J. Dynamic chromatin accessibility tuning by the long noncoding RNA ELDR accelerates chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis. Am J humgenet. 2023;110:606–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Della Valle F, Reddy P, Yamamoto M, Liu P, Saera-Vila A, Bensaddek D, Zhang H, Prieto Martinez J, Abassi L, Celii M, et al. LINE-1 RNA causes heterochromatin erosion and is a target for amelioration of senescent phenotypes in progeroid syndromes. Sci TranslMed. 2022;14:eabl 6057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Jiang Q, Li J, Zhang S, Cao Y, Xia X, Cai D, Tan J, Chen J, Han JJ. KCNQ1OT1 promotes genome-wide transposon repression by guiding RNA-DNA triplexes and HP1 binding. Nat cellbiol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, Zhang F. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan J, Enge M, Whitington T, Dave K, Liu J, Sur I, Schmierer B, Jolma A, Kivioja T, Taipale M, Taipale J. Transcription factor binding in human cells occurs in dense clusters formed around cohesin anchor sites. Cell. 2013;154:801–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mijit M, Caracciolo V, Melillo A, Amicarelli F, Giordano A. Role of p53 in the regulation of cellular senescence. Biomolecules. 2020;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kroemer G, Maier AB, Cuervo AM, Gladyshev VN, Ferrucci L, Gorbunova V, Kennedy BK, Rando TA, Seluanov A, Sierra F, et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: understanding and managing aging. Cell. 2025;188:2043–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi C, Venturin M, Gubala J, Frasca A, Corsini A, Battaglia C, Bellosta S. PURPL and NEAT1 long non-coding RNAs are modulated in vascular smooth muscle cell replicative senescence. Biomedicines. 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Casella G, Munk R, Kim KM, Piao Y, De S, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Transcriptome signature of cellular senescence. Nucleic acidsres. 2019;47:7294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XL, Subramanian M, Jones MF, Chaudhary R, Singh DK, Zong X, Gryder B, Sindri S, Mo M, Schetter A, et al. Long noncoding RNA PURPL suppresses basal p53 levels and promotes tumorigenicity in colorectal cancer. CellRep. 2017;20:2408–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han S, Li X, Wang K, Zhu D, Meng B, Liu J, Liang X, Jin Y, Liu X, Wen Q, Zhou L. PURPL represses autophagic cell death to promote cutaneous melanoma by modulating ULK1 phosphorylation. Cell deathdis. 2021;12:1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbera MC, Guarrera L, Re Cecconi AD, Cassanmagnago GA, Vallerga A, Lunardi M, Checchi F, Di Rito L, Romeo M, Mapelli SN, et al. Increased ectodysplasin-A2-receptor EDA2R is a ubiquitous hallmark of aging and mediates parainflammatory responses. NatCommun. 2025;16:1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Butler AA, Johnston DR, Kaur S, Lubin FD. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 mediates neuronal histone methylation and age-related memory impairment. Sci Signal. 2019;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kuo FC, Neville MJ, Sabaratnam R, Wesolowska-Andersen A, Phillips D, Wittemans LBL, van Dam AD, Loh NY, Todorcevic M, Denton N, et al. HOTAIR interacts with PRC2 complex regulating the regional preadipocyte transcriptome and human fat distribution. CellRep. 2022;40:111136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan L, Sun W, Lyu Y, Ju F, Sun W, Chen J, Ma H, Yang S, Zhou X, Wu N, et al. Chrom-seq identifies RNAs at chromatin marks. SciAdv. 2024;10: eadn 1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Eren M, Boe AE, Murphy SB, Place AT, Nagpal V, Morales-Nebreda L, Urich D, Quaggin SE, Budinger GR, Mutlu GM, et al. PAI-1-regulated extracellular proteolysis governs senescence and survival in Klotho mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7090–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adelman ER, Huang HT, Roisman A, Olsson A, Colaprico A, Qin T, Lindsley RC, Bejar R, Salomonis N, Grimes HL, Figueroa ME. Aging human hematopoietic stem cells manifest profound epigenetic reprogramming of enhancers that May predispose to leukemia. CancerDiscov. 2019;9:1080–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krones-Herzig A, Adamson E, Mercola D. Early growth response 1 protein, an upstream gatekeeper of the p53 tumor suppressor, controls replicative senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3233–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammal F, de Langen P, Bergon A, Lopez F, Ballester B. ReMap, 2022: a database of human, mouse, Drosophila and Arabidopsis regulatory regions from an integrative analysis of DNA-binding sequencing experiments. Nucleic acidsres. 2022;50:D316–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y, van Essen D, Saccani S. Cell-type-specific control of enhancer activity by H3K9 trimethylation. Mol Cell. 2012;46:408–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi W, Li J, Zhu X, Wang X, Fan L, Sun W, Liao L, Zhang J, Li X, Ye J, et al. CRISPR-assisted detection of RNA-protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2020;17:685–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi W, Yan J. Decoding RNA-Protein interactions: Methodological advances and emerging challenges. Adv Genet (hoboken). 2025;6:2500011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frediani E, Anceschi C, Ruzzolini J, Ristori S, Nerini A, Laurenzana A, Chilla A, Germiniani CEZ, Fibbi G, Del Rosso M, et al. Divergent regulation of long non-coding RNAs H19 and PURPL affects cell senescence in human dermal fibroblasts. Geroscience. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ozes AR, Miller DF, Ozes ON, Fang F, Liu Y, Matei D, Huang T, Nephew KP. NF-kappaB-HOTAIR axis links DNA damage response, chemoresistance and cellular senescence in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:5350–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tani H. Recent advances and prospects in RNA drug development. Int J MolSci. 2024;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chen S, Chen Q, You X, Zhou Z, Kong N, Ambrosio F, Cao Y, Abdi R, Tao W. Using RNA therapeutics to promote healthy aging. Nat Aging. 2025;5:968–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P, Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen LL, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME, Fitzgerald KA, et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol cellbiol. 2023;24:430–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen LL, Kim VN. Small and long non-coding RNAs: Past, present, and future. Cell. 2024;187:6451–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuura T, Miyazaki S, Miyazaki T, Tashiro F, Miyazaki JI. Zfp296 negatively regulates H3K9 methylation in embryonic development as a component of heterochromatin. SciRep. 2017;7:12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qian Y, Wu Q. The multifaceted roles of zinc finger proteins in pluripotency and reprogramming. Int J molsci. 2025;26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Quan R, Shi C, Sun Y, Zhang C, Bi R, Zhang Y, Bi X, Liu B, Dong Z, Jin D. PAI-1 derived from alveolar type 2 cells drives aging-associated pulmonary fibrosis. Engineering. 2024;42:74–87. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desterke C, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Turhan AG. EGR1 dysregulation defines an inflammatory and leukemic program in cell trajectory of human-aged hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). STEM Cell resther. 2021;12:419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kulkarni R. Early growth response factor 1 in aging hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia. Front. Cell Dev.Biol. 2022;10:925761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ou K, Jia Q, Li D, Li S, Li XJ, Yin P. Application of antisense oligonucleotide drugs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Huntington’s disease. TranslNeurodegener. 2025;14:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kordasiewicz HB, Stanek LM, Wancewicz EV, Mazur C, McAlonis MM, Pytel KA, Artates JW, Weiss A, Cheng SH, Shihabuddin LS, et al. Sustained therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by transient repression of huntingtin synthesis. Neuron. 2012;74:1031–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Hu D, Tang L, Zhou B, Yang L. Landscape of small nucleic acid therapeutics: moving from the bench to the clinic as next-generation medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Chrom-seq data used in this study were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) series GSE252810. Mass spectrometry raw data areavailable via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD068664. The raw reads of ChIP-seq, RNA-seq of all cell lines are deposited in GEO, with an accession no. GSE301164, GSE301166, GSE301169. All primer sequences used in this study are available in Supplementary Table S1.