Abstract

Background

Community volunteers in palliative care often notice needs that healthcare professionals and family caregivers miss, playing an important signposting role in several settings. However, community volunteers often still go unnoticed, are frequently insufficiently supported and their important contributions underutilized. In order to fulfill a signposting role, community volunteers need knowledge about palliative care needs and community resources; and they should have good relational, communication and observation skills. Training modules specifically aimed at these skills and knowledge can play an important supportive role for community volunteers.

Objectives

To develop a training to support community volunteers in their signposting role for palliative care of community residents.

Study design

A formative intervention development study.

Methods

The training was developed in the form of an interactive workshop. It's materials and protocol were designed and produced based on the following methods: review of available educational resources for community volunteers, 16 program design meetings with a psychologist trainer and 3 stakeholder advisory board meetings.

Results

The learning objectives are to increase awareness and knowledge of the volunteer role and signposting function, palliative care needs and signals, community resources, and increase self-efficacy in communication of care signals with the community resident and with healthcare professionals. The ‘Attentive Visitors’ workshop consists of a didactic session (7,5 h) focusing on developing knowledge, skills and self-efficacy, and a follow-up session (3 h) focusing on reflection and the exchange of volunteers' knowledge and experiences. Case discussions, reflection exercises and role plays are used to enhance volunteers' insights and skills related to recognizing, describing, responding to and communicating patient needs to healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

The evidence-informed Attentive Visitors Workshop aims to support community volunteers in their signposting role and to improve the connection and information exchange between volunteers and healthcare professionals. Future research will pilot and evaluate the workshop's effectiveness, acceptability and feasibility.

1. Introduction

Community volunteers hold a unique and pivotal role in bridging the gap between healthcare professionals, community residents with palliative care needs, and informal caregivers [1]. Operating independently of professional services, these volunteers provide complementary care through home visits, addressing a range care and support needs [1,2]. By offering companionship, combating loneliness, and alleviating the burden on informal and professional caregivers, volunteers enhance the wellbeing of individuals with chronic and palliative care needs [3]. Their proximity to residents allows them to observe and identify needs and wishes that otherwise go unnoticed to healthcare professionals, thus playing a vital signposting role (i.e., identifying and helping to communicate patient's care needs and wishes to healthcare professionals) [[4], [5], [6]]. Given the ageing global population, the growing burden on healthcare systems [7], and the projected rise in individuals requiring palliative care [8] and dying at home [9], the role of community volunteers will become increasingly vital.

According to Allen Kellehear's 95 % rule, individuals with life-limiting illnesses spend 95 % of their time outside of formal healthcare settings, depending on informal support from family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, volunteers and online communities [10]. For individuals with limited social networks, community volunteers are crucial in bridging gaps in support. Evidence suggests that volunteer support positively influences quality of life, social connectedness and cohesion, and illness experience for those at the end of life [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]] and during bereavement [[17], [18], [19]]. Research by Abel et al. describes community volunteer support as an important component of an emergency admission reducing ‘compassionate community’ intervention [20] (such interventions are health-promoting community-based approaches to increase community support for and reduce suffering related to experiences of serious illness, death, dying and loss [21]). Additionally, among families, the support of volunteers is appreciated [[22], [23], [24], [25]], and those receiving more volunteer hours have rated quality of palliative care higher [26].

Despite their unique position, valuable contributions and the time they spend with community residents, it is uncommon for volunteers and healthcare professionals to engage in communication, information exchange and collaboration [5]. Studies show that, while volunteers in specialist palliative care services are often well supported and trained in basic palliative care knowledge and communication with healthcare professionals, this is much less common among community volunteers [27,28]. This notwithstanding, community volunteers are actively involved in supporting people faced with end-of-life challenges and palliative care needs [28]. A previous study indicated that for volunteers to recognize, describe and signpost care needs towards healthcare professionals, they need understanding of various palliative care needs, familiarity with community resources, and well-developed relational, communication, and observation skills [1]. Targeted training and support programs for community volunteers could better enable them to fulfill signposting roles and work more effectively alongside healthcare professionals [1].

Brighton et al. [29] investigated the learning preferences of hospital volunteers engaged in palliative and end-of-life care training. Hospital volunteers valued learning from peers and palliative care specialists using interactive teaching methods including real-case examples and role plays [29]. A chance to refresh training insights at a later date was suggested to enhance the learning experience. Due to the possible emotional challenges associated with volunteering in palliative care, it is recommended that support, the sharing of experiences, and intervision to be integrated into the training of volunteers in this field [29]. In the same line, other studies reported on the desire of volunteers for ongoing education and the opportunity to connect with others who understand the challenges of their role [[13], [14], [30]]. These insights regarding learning preferences are likely transferable to the community volunteers in palliative homecare, given the lack of defined guidelines regarding training or mentoring in this setting. Furthermore, a number of training programs have been developed with the aim of addressing these learning preferences and providing support to community volunteers in a number of key areas, including communication skills [29,[31], [32], [33], [34]], understanding grief and bereavement [33], spiritual diversity [31], common symptoms [32], self-care [29,31,32], and care navigation [13,14]. Notable examples include ‘Compassionate Neighbors’ [35], ‘Compassionate Communities Connectors’ [36,37], ‘NavCare/EU Navigate’ [13,14], ‘EASE’ [38] or ‘iLIVE’ [39]. However, these multi-day training programs strengthen knowledge and skills of community volunteers, they do not focus on signposting.

To address this gap, we developed the Attentive Visitors workshop for community volunteers who visit community residents with chronic and/or palliative care needs at home, to support them in their signposting role. This paper reports on the development process, the content and training materials used in the Attentive Visitors workshop.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

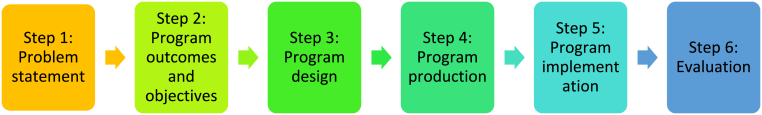

This study follows the Intervention Mapping Protocol (IMP) [40]. This paper is part of a broader research project that aims to develop, test and evaluate a training program that supports community volunteers in their signposting role. We follow the Intervention Mapping Protocol (IMP), an approach to the development of interventions aimed at the successful change of behavior [40]. (See Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Different steps of the Intervention Mapping Protocol (IMP) [40].

Steps 1 and 2 were reported elsewhere [1]. The current paper focuses on step 3: program design and step 4: program production. See Table 1 for an overview of the methods used for the development the workshop program.

Step 3: Program Design: The workshop was designed in collaboration with a professional trainer (ES) and our stakeholder advisory board. Box 1 gives an overview of the various backgrounds of the stakeholders involved.

Table 1.

Overview of methods used for the development of the workshop program [40].

| Step 3: Program design |

|

| Step 4: Program production |

|

Box 1. Members of Stakeholder Advisory Board of volunteer training experts and coordinators.

-

-

Palliative Care Network coordinator

-

-

Palliative Care Policy officer

-

-

Nurse expert in Pain and Comfort

-

-

Educational officer and volunteer coordinator of a Community-based homecare organisation

-

-

Community-based homecare organisation head of Department

-

-

Volunteer coordinator of a palliative daycare centre

-

-

Coordinator of a family caregiving support organisation

-

-

Palliative Care Specialist and former hospice coordinator

-

-

General Practitioner

Alt-text: Box 1

Theory- and evidence-based behavior change methods were selected based on the learning objectives formulated in steps 1–2 [1,40] and existing Flemish training programmes were reviewed for inclusion. Flemish training programs were identified through input from stakeholder advisory board, a web search, reviewing existing training modules available within the research group and from our stakeholders, and contacting organizations that offer training with overlapping content. The resulting materials were then evaluated using a list of criteria presented in Box 2. Existing materials that fit the criteria were incorporated into the workshop.

Box 2. Selection criteria for workshop methods and materials.

During the development and selection of workshop methods and materials, the following selection criteria were considered to evaluate their appropriateness for integration into the Attentive Visitors workshop:

-

1.

Can the workshop method contribute to achieving one or more learning objectives? Specific learning objectives were established prior to the workshop, based on the qualitative research conducted in steps 1 and 2 (Problem Statement & Program Outcomes and Objectives), which determine the focus of the workshop. The overall topic of the workshop is 'detecting (palliative) care needs,' within which specific sub-goals were formulated.

-

2.

Does the chosen method fit the type of outcome it aims for?

-

3.

Does the chosen method align with the target audience and group size?

-

4.

Does the sequence and variation of workshop methods ensure continuous attention and engagement? Variation must be present in several factors, such as using different senses and intelligences, but also by having participants work alternately in pairs, then in groups of three, and finally as a whole class. This way, different approaches can be accommodated, thereby maintaining the attention of participants.

-

5.

Does the method leave room for acknowledgment and build further on existing knowledge and skills of the participants?

Alt-text: Box 2

Where gaps in the existing training options were identified, new workshop components were developed (See Table 1) using ES's input and expertise, as well by aligning learning objectives with appriatiote methods. The workshop was designed as a modular package, with each module covering one learning objective to construct a comprehensive reference workshop course.

Step 4: Program Production: In Step 4, the content and methods developed in Step 3 were put together into a concrete program [40]. We produced a description of the scope and sequence of the components of the intervention, program materials, and program protocols. The workshop was then tested internally and the composition was fine-tuned in consultation with our stakeholders, ensuring that the workshop fit the learning objectives, was relevant for community-based volunteers visiting people at home), and that they met the standards of excellence expected in the field. The required workshop materials and exercises were crafted and honed to create a workshop program. Table 1 presents the methods used in Step 4.

3. Results

3.1. Program design (Step 3 of the IMP)

3.1.1. Review of available educational resources for community volunteers

We identified 6 of 34 reviewed training materials (modules or working methods) available and used in existing Flemish training programs. See Table 2 provides an overview of their goals and which elements were considered useful for the Attentive Visitors workshop.

Table 2.

Remaining training programs, training modules, and exercise after the review.

| Reviewed training programs, modules or exercises | Goals | Elements (core ideas, exercices or working methods) included in the Attentive Visitors workshop |

|---|---|---|

| Basic training in palliative care for volunteers, offered by the Palliative Networks in Flanders [41] |

|

The following elements were adapted and included:

|

| Dealing with existential questions [42] |

|

The following elements were adapted and included: exercise on awareness and formulation of one's own boundaries based on a case and guiding questions |

| Volunteers as referrers, offered by Christian Sickness Fund (CM) [43] |

|

The following core ideas were inlcudes in the case studies:

|

| SEE ME training [44] |

|

The following elements were adapted and included:

|

| An Katz's communication model (4O model) [45] |

|

The following elements were adapted and included: application of the conversation model to cases (opening statement, open question, reviewing options and following up on concrete actions) |

| Principles Photovoice [46] and Photo Elicitation [47] |

|

The following elements were adapted and included: use of images to stimulate relevant reflection about their volunteer role Icebreaker exercise |

Notable gaps in existing training programs were: (1) lack of specific focus on the community context, and (2) lack of explicit focus on communication and signposting of care needs to the community residents or healthcare professionals. New components to the workshop were therefore designed to address these gaps.

3.1.2. Program design meetings with psychologist trainer

A total of 16 meetings (occurring on a weekly basis) were held between SVS and ES from April 2022 to November 2022 to discuss the content, structure and time investment of the workshop. Workshop materials were developed that focused on balancing knowledge, understanding, and skills exercises. Opportunities for reflection and experience sharing were incorporated throughout the workshop.

3.1.3. Stakeholder advisory board consultation meetings and project group meetings

The design of the workshop was discussed with our stakeholder advisory board and our scientific project group (SVS, SV, ES, SD, KC, LD). The stakeholder advisory board met on 3/5/22, October 24, 2022, and August 24, 2023 and helped develop the workshop materials, including a palliative care knowledge quiz and two persona cases. A palliative care specialist ensured the cases' relatability. Pre-defined case studies allow trainers maintain control and reduce participant burden. The stakeholders recommended emphasizing the importance of addressing care and support need signals with the resident first, and of the resident's consent prior to contacting a healthcare professional directly. Additionally, it was agreed that the signposting role should not be framed as mandatory, but the workshop should enable volunteers who want to take up this role. Finally, stakeholders urged us to explicitly call the workshop a workshop, as it emphasizes interaction and experience-sharing. Table 3 provides an overview of the different learning objectives in the workshop, their corresponding sub-goals and methods.

Table 3.

Learning objectives, sub-goals and corresponding methods used in the Attentive Visitors Workshop.

| Learning objective | Sub-goal | Method | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PART 1: didactic workshop (7,5 h) |

Participants will know their fellow participants better. |

|

Introduction by photos (Appendix I), inspired by Principles of Photovoice [46] and Photo Elicitation [47] |

| Participants will have increased knowledge about palliative care. |

|

Quiz (Appendix II), inspired by basic training in palliative care for volunteers, offered by the Palliative Networks in Flanders [41] | |

| Participants will have increased awareness of the volunteer role and the signposting function. |

|

Group discussions, inspired by: | |

| Participants will have increased knowledge palliative care needs, and increased skills and self-efficacy in identifying available community and professional care resources. |

|

|

|

| Participants will have increased awareness of boundaries and engaging other community resources. |

|

Group discussions, inspired by: | |

| Participants will have increased awareness of the support network and support needs of the resident. |

|

Social ecological mapping exercise (Appendix IV) | |

| Participants will have increased skills and self-efficacy in communicating and addressing identified support needs with informal caregivers and healthcare professionals. |

|

Social ecological mapping exercise (Appendix IV), Volunteer introduction flyer (Appendix V) and Role play exercises, inspired by basic training in palliative care for volunteers, offered by the Palliative Networks in Flanders [41] | |

| Participants will have increased skills and self-efficacy in communicating and addressing identified support needs with community residents. |

|

Role play exercises (Appendix IV), inspired by: | |

| PART 2: follow-up session (3 h) | All | All | Discussion tables |

3.1.4. Volunteer consultation

We sought feedback on the design, content and materials of the workshop from community-based volunteers. While we contacted 14 volunteers who expressed interest, ultimately only one volunteer participated in the consultation. This feedback was helpful in revising the materials in terms of simplified instructions and avoiding excessive academic language. Additionally, the volunteer suggested to provide time for consolidation and reflection on the insights gained following each exercise in the workshop. Finally, regular breaks was also integrated into the workshop scheduling following input from the volunteer.

3.2. Program production (Step 4 of IMP)

3.2.1. Pretest and refining of workshop materials

The workshop components and materials were evaluated for face and cognitive validity with six colleagues from the End-of-Life Care Research Group (UGent) and with eight stakeholder advisory board members. They were evaluated in terms of their clarity and difficulty of instructions, working methods, and content. This lead to further streamlining of the workshop language and content. The duration of the didactic workshop was extended from six to 7.5 h to accommodate a welcome, introduction, scheduled breaks, and a closing session. The quiz on general misconceptions about palliative care was complemented with additional clarification following the presentation of each question. It was also decied that participants were permitted to respond to the questions as a team to prevent any potential feelings of intimidation or vulnerability. While testing the exercises, several community resources were identified that could be shared with volunteers upon completion of the exercises. Additionally, a new section was added to the training materials, focusing on the boundaries of the volunteer role and the importance of volunteers being able to identify and access appropriate support.

3.2.2. Production of workshop program

The Attentive Visitors workshop was developed as a two-part workshop, comprising a didactic workshop (7,5 h) and a follow-up session (3 h) organized approximately two months later. The didactic workshop provides knowledge about palliative care and palliative care needs, insights into the role and support of the social network, and communication skills to facilitate discussions and explore care needs with the community residents and healthcare professionals. The follow-up session focuses on group reflection (i.e., how have the volunteers integrated what they've learned into practice, what new or persistent challenges have they faced) and knowledge exchange (i.e., enabling volunteers to gain insight and advice from one another on the challenges they encounter in their volunteer roles). The follow-up session addresses the need for reflection, intervision and sharing of experiences and is designed to be repeatable over time (e.g., every few weeks or months). It provides an opportunity to consolidate the newly acquired knowledge and skills from the didactic workshop by briefly revisiting them, thereby increasing their chance of being implemented. Finally, the optimal group size was established through consultation with our stakeholder advisory board, and the workshop was designed for groups of 10–15 participants.

3.3. Overview of workshop program

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the various components, including learning objectives, sub-goals and corresponding methods, that constitute the final two-part ‘Attentive Visitors’ workshop for community volunteers.

Appendix VIII provides a comprehensive and detailed elaboration of the contents of Table 3. Additionally, Appendix VIII outlines how learning objectives, sub-objectives, and methods are implemented in the Attentive Visitors workshop.

4. Discussion

This study describes the development and content of the Attentive Visitors workshop, an evidence-informed training designed to support community volunteers in their palliative care signposting role. By integrating a 7.5 h didactic workshop with a 3-h follow-up session, the workshop aims to (1) increase awareness of the volunteer's role and improve understanding of the support network and support needs of the community residents; (2) Expand knowledge about palliative care needs and available resources; and (3) Strengthen communication skills and self-efficacy for engaging with community residents, healthcare professionals, and identifying available community and professional care resources. The workshop incorporates experiential learning methods to encourage practical application in real-life volunteer activities.

5. Strengths and limitations

First, to our knowledge, this study is the first to develop a workshop tailored to equip community volunteers with knowledge and skills to recognize, describe and signpost palliative care needs to healthcare professionals. The evidence-informed Attentive Visitors workshop adds value to current experiences of communication and information sharing between community volunteers and healthcare professionals. Second, the use of the Intervention Mapping protocol, ensured a structured, theory- and evidence-based approach, integrating stakeholder and end-user perspectives. Third, the diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and expertise, and the commitment of our stakeholder advisory board to the co-development of the workshop ensured that workshop components were relevant in addressing community volunteers needs and gaps in existing training programs. This co-development process enhances the workshop's feasibility and potential effectiveness for real-world implementation. Another strength is the workshop's alignment with the Compassionate Communities framework. By fostering skills that encourage connection, communication, and collaboration, the workshop empowers volunteers to strengthen social networks and improve information exchange with healthcare professionals. These contributions are critical in bridging gaps in support for individuals with palliative care needs. Despite its strengths, the study has limitations. Input from community volunteers was limited due to challenges in bringing together participants, including holiday plans, volunteer responsibilities, and caregiving commitments, resulting in feedback from only one volunteer. Although initially interested, many volunteers disengaged when repeatedly asked for their availability digitally. One-on-one consultations or alternative engagement strategies might have been more effective in capturing their perspectives. An additional consideration concerns the time investment required for the full-day workshop. The limited response from volunteers during development may indicate a participation barrier, given their other commitments such as work or other caregiving responsibilities. This raises concerns about the workshop's feasibility and scalability. It is recommended that this aspect be explicitly investigated during pilot testing and evaluation, with particular focus on accessibility and conditions for implementation. Finally, only Flemish training programs for community volunteers on signposting and communication were reviewed. The search for existing training courses was neither systematic nor exhaustive. Reviewing, adapting, and translating international training courses was beyond the scope of this study; however, future research could benefit from comparing the Attentive Visitors workshop with international training programs.

5.1. Innovative aspects of the “Attentive visitors” workshop

5.1.1. Fit within the Compassionate Communities movement

The workshop's alignment with the Compassionate Communities movement [48,49] is a key innovation. By equipping community volunteers to recognize, describe, and address palliative care needs, it extends their capacity to support community residents, fosters stronger connections between informal and professional care networks, and enhances communication and collaboration with other stakeholders involved in the care process. The Attentive Visitors workshop emphasizes capacity building by enhancing the skills and confidence of volunteers, fostering stronger connections within the community to ensure more effective and sustainable support. Furthermore, the workshop values the experiences of volunteers and utilizes them as a valuable 'asset' to support other volunteers, including through the organization of a follow-up session.

Another key component of Compassionate Communities approaches is to develop a way to connect and enhance the social support and care networks that already exist in community life [48,49]. The Attentive Visitors workshop contributes to this by aiming to connect and enhance the interactions between volunteers and generalist primary care services by supporting volunteers' abilities to recognize, describe, and communicate care needs to the person with care needs and professional caregivers. The Attentive Visitors workshop also aligns with the core ideas behind Abel et al.’s ‘Circles of Care’ model [50] which applies a socio-ecological model to end-of-life challenges, viewing individuals, communities, service organizations and policy makers working together to provide end-of-life care that increases the value and meaning for people at the end of their lives, both patients and communities [50].

5.1.2. Focus on signposting

While other programs have focused on communication skills [29,[31], [32], [33], [34]], grief [33], spiritual diversity [31], symptoms [32], self-care [29,31,32] and care navigation [13,14], the Attentive Visitors workshop uniquely emphasizes the signposting role of volunteers, which is an area often overlooked. The workshop focusses on strengthening self-confidence and self-efficacy, which is a critical gap in volunteer training. Additionally, the attentive Visitors workshop is co-developed and evidence-informed, building on a qualitative needs assessment study that includes input and perspectives from multiple stakeholders. The accessible nature, concise format (short duration of 1.5 days) and modular structure make it complementary to existing training programs, ensuring accessibility and relevance for diverse audiences.

5.1.3. Experiential learning

The Attentive Visitors workshop integrates David A Kolb's experiential learning cycle, encompassing experiencing, reflecting, thinking, acting [51]. The methods used in the Attentive Visitors Workshop are experiential learning activities. These hands-on, interactive and collaboratice exercises create opportunities to connect theory to real-life case studies, encouraging community volunteers to actively engage, reflect, and apply their learning in their volunteer work. The organization of a follow-up moment serves as a practical application of the experiential learning cycle. Community volunteers are encouraged to share and reflect on experiences and challenges they've encountered in their volunteer work since the first workshop day. By attending the follow-up session, community volunteers are encouraged to integrate and apply their newly gained insights into their ongoing volunteer activities, completing the cycle of learning through experience, reflection, thinking and acting. The focus on peer learning and experiential learning within the Attentive Visitors workshop aligns with the idea of a community of practice in which community volunteers can share knowledge, expertise and experiences, learning from each other to address challenges they encounter [52]. The developers of the Attentive Visitors workshop encourage the continued organization of follow-up moments after the Attentive Visitor Workshop has been completed.

5.2. Recommendations for policy, practice and further research

In the future, the Attentive Visitors training program could become part of the standard training curriculum for community volunteers, offered through health insurance funds or other training providers. However, before implementation, future research should pilot-test and evaluate the Attentive Visitors Workshop regarding effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility before wider implementation. This includes assessing its alignment with the needs of community volunteers, community residents, and informal caregivers, and determining whether program adjustments are needed. Evaluating its impact on improving volunteers’ death literacy would also provide valuable insights. Developing such a training requires collaboration with stakeholders, including end-users and future implementers, ensuring programs are co-created through open dialogue and mutual respect. Managing power dynamics, along with fostering collaboration and reciprocity, is essential for successful co-creation. Policymakers must recognize community volunteers as key partners in palliative care and prioritize their training and support. With the growing global aging population, equipping volunteers for palliative homecare is an urgent international priority.

6. Conclusion

In line with public health approaches to connect and enhance the social support and care networks that already exist within communities – exemplified in the Compassionate Community movement, an evidence-informed workshop was developed supporting community volunteers in their signposting role, with a focus on enhancing connection, collaboration, communication and information exchange between volunteers and healthcare professionals. In the future, the Attentive Visitor workshop will be pilot tested and evaluated to assess its effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility.

Author statements

- Sabet Van Steenbergen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing – review and drafting.

- Steven Vanderstichelen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing original draft, Writing - review & editing.

- Else Gien Statema: Review & editing.

- Luc Deliens: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

- Sarah Dury: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

- Kenneth Chambaere: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Ethical approval

The research project that his study was part of received ethical approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the Ghent university Hospital (Ghent University) on November 10, 2020 (B U N.: B6702020000359). An amendment prolonging the study period due to COVID-19 June 30, 2022 was approved on December 15, 2021.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials of this study are with the first author and are available upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the Flemish Cancer Fund (Kom op tegen kanker) under grant nr PSC 17/6/19–000140946 and The Flemish Research Foundation (FWO) under grant nr. 1200424N.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2025.100663.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Van Steenbergen S, Vanderstichelen S, Deliens L, Dury S., Chambaere K. What knowledge and skills are needed for community volunteers to take on a signposting role in community-based palliative care? A qualitative study. Paliative Care Soc. Pract. 2025:19. doi: 10.1177/26323524251334184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanderstichelen S., Houttekier D., Cohen J., Van Wesemael Y., Deliens L., Chambaere K. Palliative care volunteerism across the healthcare system: a survey study. Palliat. Med. 2018 Jul;32(7):1233–1245. doi: 10.1177/0269216318772263. Epub 2018 May 8. PMID: 29737245; PMCID: PMC6050945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichol B., Wilson R., Rodrigues A., Haighton C. Exploring the effects of volunteering on the social, mental, and physical health and well-being of volunteers: an umbrella review. Voluntas. 2023 May;4:1–32. doi: 10.1007/s11266-023-00573-z. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37360509; PMCID: PMC10159229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egerton M., Mullan K. Being a pretty good citizen: an analysis and monetary valuation of formal and informal voluntary work by gender and educational attainment. Br. J. Sociol. 2008 Mar;59(1):145–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00186.x. PMID: 18321335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanderstichelen S., Cohen J., Van Wesemael Y., Deliens L., Chambaere K. The liminal space palliative care volunteers occupy and their roles within it: a qualitative study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2020 Sep;10(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001632. Epub 2018 Dec 7. PMID: 30530629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanderstichelen S., Cohen J., Van Wesemael Y., Deliens L., Chambaere K. Perspectives on volunteer-professional collaboration in palliative care: a qualitative study among volunteers, patients, family carers, and health care professionals. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019 Aug;58(2):198–207.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.016. Epub 2019 Apr 25. PMID: 31028875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sleeman K.E., de Brito M., Etkind S., Nkhoma K., Guo P., Higginson I.J., Gomes B., Harding R. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Global Health. 2019 Jul;7(7):e883–e892. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31129125; PMCID: PMC6560023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etkind S.N., Bone A.E., Gomes B., Lovell N., Evans C.J., Higginson I.J., Murtagh F.E.M. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017 May 18;15(1):102. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2. PMID: 28514961; PMCID: PMC5436458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bone A.E., Gomes B., Etkind S.N., et al. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? population-based projections of place of death. Palliat. Med. 2017;32(2):329–336. doi: 10.1177/0269216317734435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allan Kellehear. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone's responsibility. QJM: Int. J. Med. December 2013;106(12):1071–1075. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daddow A., Stanley M. Heidi's legacy: community palliative care at work in regional Australia. Soc. Work. Health Care. 2021;60:529–542. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2021.1958128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley Stanley M.A., Daddow A.A. Well, what do you want to do?’ A Case Study of Community Palliative Care Programme: ‘heidi's have a Go. Omega: J. Death Dying. 2024;88(4):1335–1348. doi: 10.1177/00302228211052801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pesut B., Duggleby W., Warner G., Fassbender K., Antifeau E., Hooper B., Greig M., Sullivan K. Volunteer navigation partnerships: piloting a compassionate community approach to early palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care. 2017 Jul 3;17(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0210-3. 10.1186/s12904-017-0210-3. Erratum in: BMC Palliat Care. 2017 Oct 10;16(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0233-9. PMID: 28673300; PMCID: PMC5496423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pesut B., Duggleby W., Warner G., Kervin E., Bruce P., Antifeau E., Hooper B. Implementing volunteer-navigation for older persons with advanced chronic illness (Nav-CARE): a knowledge to action study. BMC Palliat. Care. 2020 May 22;19(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00578-1. PMID: 32443979; PMCID: PMC7245025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley S.G., Pettus K.I., Abel J. The buddy group - peer support for the bereaved. Lond. J. Prim. Care. 2018;10:68–70. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2018.1455021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh P., Gartrell G., Egg G., et al. End-of-Life care in a community garden: findings from a participatory action research project in regional Australia. Health Place. 2017;45:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruce P., Pesut B., Dunlop R., et al. (Dis)Connecting through COVID-19: experiences of older persons in the context of a volunteer-client relationship. Can. J. Aging. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0714980821000404. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West K., Rumble H., Shaw R., et al. Diarised reflections on COVID-19 and bereavement: disruptions and affordances. Illn. Crises Loss. 2023;31:151–167. doi: 10.1177/10541373211044069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ummel D., Vachon M., Guité-Verret A. Acknowledging bereavement, strengthening communities: introducing an online compassionate community initiative for the recognition of pandemic grief. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2022;69:369–379. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abel J., Kingston H., Scally A., et al. Reducing emergency hospital admissions: a population health complex intervention of an enhanced model of primary care and compassionate communities. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018;68:e803–e810. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X699437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanderstichelen S., Dury S., De Gieter S., Van Droogenbroeck F., De Moortel D., Van Hove L., Rodeyns J., Aernouts N., Bakelants H., Cohen J., Chambaere K., Spruyt B., Zohar G., Deliens L., De Donder L. Researching compassionate communities from an interdisciplinary perspective: the case of the compassionate communities center of expertise. Gerontol. 2022 Nov 30;62(10):1392–1401. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac034. PMID: 35263765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claxton-Oldfield S., Gosselin N., Schmidt-Chamberlain K., Claxton-Oldfield J. A survey of family members' satisfaction with the services provided by hospice palliative care volunteers. Am J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2010 May;27(3):191–196. doi: 10.1177/1049909109350207. Epub 2009 Dec 18. PMID: 20023274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luijkx K.G., Schols J.M. Volunteers in palliative care make a difference. J. Palliat. Care. 2009 Spring;25(1):30–39. PMID: 19445340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGill A., Wares C., Huchcroft S. Patients' perceptions of a community volunteer support program. Am J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 1990 Nov-Dec;7(6):43–45. doi: 10.1177/104990919000700606. PMID: 14686473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weeks L.E., Macquarrie C., Bryanton O. Hospice palliative care volunteers: a unique care link. J. Palliat. Care. 2008;24(2):85–93. Summer. PMID: 18681244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Block E.M., Casarett D.J., Spence C., Gozalo P., Connor S.R., Teno J.M. Got volunteers? Association of hospice use of volunteers with bereaved family members' overall rating of the quality of end-of-life care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010 Mar;39(3):502–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.310. PMID: 20303027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderstichelen S., Houttekier D., Cohen J., Van Wesemael Y., Deliens L., Chambaere K. Palliative care volunteerism across the healthcare system: a survey study. Palliat. Med. 2018;32(7):1233–1245. doi: 10.1177/0269216318772263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanderstichelen S., Cohen J., Van Wesemael Y., Deliens L., Chambaere K. Volunteers in palliative care: a healthcare system-wide cross-sectional survey. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2022 May;12(e1):e83–e93. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002321. Epub 2020 Aug 21. PMID: 32826268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brighton L.J., Koffman J., Robinson V., Khan S.A., George R., Burman R., Selman L.E. 'End of life could be on any ward really': a qualitative study of hospital volunteers' end-of-life care training needs and learning preferences. Palliat. Med. 2017 Oct;31(9):842–852. doi: 10.1177/0269216316679929. Epub 2017 Jan 6. PMID: 28056642; PMCID: PMC5613806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Söderhamn U., Flateland S., Fensli M., Skaar R. To be a trained and supported volunteer in palliative care - a phenomenological study. BMC Palliat. Care. 2017 Mar 14;16(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0193-0. PMID: 28288598; PMCID: PMC5348768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mundle C., Naylor C., Buck D. 2012. Volunteering in Health and Care in England; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown M.V. The stresses of hospice volunteer work. Am J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2011 May;28(3):188–192. doi: 10.1177/1049909110381883. Epub 2010 Sep 11. PMID: 20834036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dein S., Abbas S.Q. The stresses of volunteering in a hospice: a qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2005 Jan;19(1):58–64. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm969oa. PMID: 15690869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deodhar J.K., Muckaden M.A. Continuing professional development for volunteers working in palliative care in a tertiary care cancer institute in India: a cross-sectional observational study of educational needs. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2015 May-Aug;21(2):158–163. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.156475. PMID: 26009668; PMCID: PMC4441176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Compassionate Neighbours Gent. https://compassionateneighbours.org/ [consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on:

- 36.Aoun S.M., Richmond R., Gunton K., Noonan K., Abel J., Rumbold B. The compassionate communities connectors model for end-of-life care: implementation and evaluation. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2022 Nov 30;16 doi: 10.1177/26323524221139655. PMID: 36478890; PMCID: PMC9720808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoun S.M., Abel J., Rumbold B., Cross K., Moore J., Skeers P., Deliens L. The compassionate communities connectors model for end-of-life care: a community and health service partnership in Western Australia. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2020 Jul 2;14 doi: 10.1177/2632352420935130. PMID: 32656530; PMCID: PMC7333490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.End of Life Aid Skills for Everyone (EASE). Gent. [consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: End of Life Aid Skills for Everyone (EASE) | Good Life, Good Death, Good Grieatf.

- 39.iLIVE. Live well, Die well: a research programme to support living until the end. Gent., [consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: https://www.iliveproject.eu/.

- 40.Bartholomew-Eldredge L.K., Markham C., Ruiter R.A., Fernandez M.E., Kok G., Parcel G. fourth ed. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2016. Planning Health Promotion Programs: an Intervention Mapping Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palliative Care Flanders. Basic Training in Palliative Care for Volunteers. Gent,. [consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: Basisopleiding palliatieve zorg voor vrijwilligers – Palliatieve Zorg Vlaanderen.

- 42.Stephanie Vermeulen. Dealing with Existential Questions. Gent, .[consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: Omgaan met zinvragen 2e drBW.QXD.

- 43.Christian Sickness Fund. Volunteers as Referrers. Gent,. [consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: Vrijwilligers als verwijzers.pdf.

- 44.SEE ME training. Customer service training: brining service to life in care communities. Gent, .[consulted on 23 December 2024]. Available on: SEE ME TRAINING - See ME Training.

- 45.Katz A. Compassion in practice: difficult conversations in oncology nursing. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2019 Oct 1;29(4):255–257. PMID: 31966003; PMCID: PMC6970020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suprapto N., et al. A systematic review of photovoice as participatory action research strategies. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020 September;9(3):675–683. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20581. ISSN: 2252-8822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Auken P.M., Frisvoll S.J., Stewart S.I. Visualising community: using participant-driven photo-elicitation for research and application. Local Environ. 2010;15(4):373–388. doi: 10.1080/13549831003677670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abel J., Kellehear A., Karapliagou A. Palliative care-the new essentials. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018 Apr;7(Suppl 2):S3–S14. doi: 10.21037/apm.2018.03.04. PMID:29764169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kellehear A. Routledge; Oxfordshire: 2005. Compassionate Cities. Public Health and end-of-life Care. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abel J., Walter T., Carey L.B., Rosenberg J., Noonan K., Horsfall D., Leonard R., Rumbold B., Morris D. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2013 Dec;3(4):383–388. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000359. Epub 2013 Mar 6. PMID: 24950517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolb A., Kolb D. Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educ. Leader. 2018;40(3):8–14. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.192540196827567 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horey D., Street A.F., O'Connor M., Peters L., Lee S.F. Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 Jul 20;2015(7):CD009500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009500.pub2. PMID: 26189823; PMCID: PMC8917830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials of this study are with the first author and are available upon reasonable request.