Abstract

Extensive research has documented altered emotion processing in binge drinkers. Genetic risks contribute to problem drinking; however, it remains unclear how genetic risks for alcohol misuse affect behavioral and brain responses to negative emotions. We curated data from the Human Connectome Project and identified 97 binge (69 men) and 379 demographically-matched non-binge (142 men) drinkers performing an emotion task during brain imaging. Alcohol use severity was quantified by the first principal component (PC1) identified of principal component analysis of 15 drinking measures. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) for alcohol dependence were computed for all subjects. With published routines and at a corrected threshold, we evaluated how brain responses to matching negative emotional faces vs. geometric shapes associated with PC1 and PRS in a linear regression, with age, sex, and race as covariates. Higher PC1 and PRS were both significantly correlated with greater symptom severity of somatic complaints in binge drinkers. Bingers relative to non-bingers showed stronger activation of a wide array of frontal, parietal and occipital regions and the insula in positive correlation with the PRS. These genetic risk markers featured more prominently in male than in female binge drinkers. In contrast, regional responses in the default mode network may represent sex-shared markers of the genetic risks. These findings suggest altered neurobiological processes of negative emotions in correlation with genetic risks for alcohol misuse in binge drinkers. Longitudinal studies are needed to show how dysfunctional negative emotion processing interlinks the genetic risks and problem drinking.

Subject terms: Epigenetics and behaviour, Predictive markers

Introduction

Binge drinking is a common pattern of alcohol misuse among young adults, with a prevalence rate as high as 28.7% in 2023, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [1]. Prior research has associated binge drinking with heightened negative emotions [2]. Dysfunctional emotion processing increases the likelihood of excessive drinking and the development of severe alcohol use disorders (AUD) [3]. Numerous studies have documented that negative emotions and maladaptive use of alcohol to cope with negative emotions constitute major risk factors in the pathophysiology of AUD [2,4]. Likewise, many investigators have employed brain imaging to examine the neural mechanisms underlying emotion processing in binge drinkers [5, 6]. For instance, binge relative to non-binge drinkers showed increased activity in bilateral ventromedial prefrontal cortices but reduced activity in the right temporal pole and cuneus when processing angry vs. neutral faces [7] as well as greater activity in the right middle frontal gyrus and lower activity in bilateral superior temporal gyri when processing angry/fearful vs. neutral voices [8]. Understanding these neurobiological processes is essential for treatments targeting negative emotions and preventing the escalation of hazardous alcohol use.

Genetic factors account for over 50% of the variance in individual susceptibility to alcohol misuse [9–11]. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) for AUD, a weighted sum of the effects of risk alleles an individual carries [12], have been shown to predict the severity of alcohol misuse [13–15] and identify individuals at risk for problem drinking [16]. We wanted to test if dysfunctional emotion processing was associated with PRS for alcohol dependence in binge drinkers. Emotion function and dysfunction and the neural underpinnings are moderately heritable (30-60%), as estimated through ACE modeling, which separates variance into additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and non-shared environmental (E) factors in twin and family studies [17–19]. Previous research showed that allelic variation in serotonergic signaling influenced prefrontal cortical and amygdala responses to emotional stimuli in problem drinkers [20]. A more recent study leveraged data from large scale genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and identified shared single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between mood instability and alcohol-related phenotypes [21]. Further, substance including alcohol misuse and other comorbid behaviors may share similar genetic underpinnings [22, 23]. PRS computed for externalizing traits was significantly associated with a wide array of externalizing phenotypes, including substance use disorders, suicide, HIV infections, criminal convictions, and unemployment [22]. These findings together highlight the links between genetic risks for alcohol misuse and emotional dysfunction and the conceptual importance of investigating the neural correlates of emotion processing dysfunction as influenced by the genetic risks for alcohol misuse. Considering that AUD is a complex polygenic disorder, examining the PRS-related neural markers of emotion processing may help in identifying individuals at risk for problem alcohol use.

Behavioral and neural markers of drinking severity, genetic risks, and emotion dysfunction vary by sex. Men are more likely to start drinking earlier, develop alcohol misuse, and have a higher lifetime prevalence of AUD, as compared to women [24, 25]. Female relative to male drinkers report more depressive and stress symptoms [26] and more negative mood states during early stages of alcohol abstinence [3]. Men with AUD relative to neurotypical controls showed higher responses in bilateral inferior frontal gyri to fearful vs. neutral faces whereas women with AUD showed the opposite relative to controls [27]. These findings appear to suggest a more important role of negative emotion in perpetuating drinking in women than in men and certainly highlight the importance of incorporating sex as a biological variable to better understand the neurobiological processes in the development of AUD. To the best of our knowledge, however, no prior research has explored sex differences in neural markers of emotion processing in relation to PRS for alcohol dependence. Filling this gap in knowledge is essential to uncovering sex-specific vulnerabilities to emotional dysfunction and AUD.

In the current study, we aimed to examine how neural markers of negative emotion processing manifested in the overall genetic risks for AUD and whether these markers could be distinguished from those reflecting drinking severity. To this end, we examined the clinical, task fMRI, and genotyping data of young binge and non-binge drinkers of the Human Connectome Project (HCP). We quantified drinking severity and PRS for each subject for correlation with regional activations during matching of negative faces vs. neutral shapes in a linear regression model for binge and non-binge drinkers, respectively. We used slope tests to confirm the specificity of PRS- or symptom severity- related correlates of negative emotion processing. We also performed the analyses separately for men and women and, in post-hoc comparisons, confirmed sex differences. We hypothesized shared and unique correlates of alcohol use severity and PRS for alcohol dependence as well as significant sex differences in these correlates in binge drinkers. Specifically, based on prior research, we anticipated that greater alcohol use severity and PRS would be associated with higher activation in the frontolimbic emotional circuits, including the ventromedial PFC, ventral ACC, insula, and striatum, in binge drinkers. Furthermore, we expected these associations to be stronger in male than in female binge drinkers.

Methods

Dataset: subjects and assessments

In the S1200 release, the HCP contains clinical, behavioral, and 3T magnetic resonance (MR) imaging data of 1206 young adults (1113 with structural MR scans) without severe neurodevelopmental, neuropsychiatric, or neurologic disorders. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The current sample included 453 families with 1140 healthy twins or siblings (ages 22–35; 618 women) who had genotyping data. As in our previous studies [28–31], binge drinking was defined as having 4/5 drinks (women/men) on a single occasion [32]. The binge drinking group comprised 97 adults (69 men, 71.1%) who reported binge drinking at least once a week for the last 12 months [5]. A total of 379 adults (142 men, 37.5%) reported no binge drinking in the prior year and no lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence. The chi-squared test showed a significant sex difference in the subject composition, with more men and women each included in the binge and non-binge group, respectively (χ² = 35.47, p < 0.001).

As described in detail in our prior studies [33–35], participants were assessed with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA), an instrument designed to evaluate physical, psychological and social manifestations of alcoholism and related disorders [36]. As in our previous work [28], we performed a principal component analysis on the 15 interrelated drinking metrics of the SSAGA and identified the first principal component (PC1) with an eigenvalue > 1 that accounted for 49.54% of the variance. The drinking PC1 was used as the target phenotype for the computation of PRS.

All participants were also evaluated with the Achenbach Adult Self-Report (ASR) [37]. Here, we focused on measures of anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints to evaluate negative emotions. Raw scale scores were transformed to sex- and age- normalized T scores. Because a substantial number of individuals in the normative samples scored very low on the DSM-oriented and syndrome scales (e.g., scores of 0 or 1), the T score assignments started at 50, which represents the 50th percentile of a normative sample. The age- and sex- adjusted T scores of depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints subscales were used in the analyses, with higher T scores indicating higher symptom severity.

fMRI data acquisition, preprocessing, and general linear model

The details of data acquisition and preprocessing are presented in the Supplement. Participants completed two runs of an emotion task (one with a right-to-left and the other with a left-to-right phase encoding) during one visit, adapted from the work by Hariri, Tessitore [38]. As described in detail earlier [39], participants were presented with blocks of trials where they were to decide which of the two faces (face blocks) or shapes (shape blocks) presented at the bottom of the screen matched the face or shape at the top. The faces had either angry or fearful expressions. Each block comprised 6 trials of the same task (face or shape), with the stimulus presented for 2 s and an inter-trial-interval of 1 s. Each block was preceded by a 3-s task cue (“shape” or “face”). Each of the two runs included 3 face and 3 shape blocks.

BOLD data were analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, Welcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London, U.K.), following our published routines, including realignment, coregistration, segmentation, normalization, and smoothing [40, 41]. A statistical analytical block design was constructed for each individual subject, using a general linear model (GLM) where the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) was convolved with a boxcar function in SPM12. Realignment parameters in all six head motion parameters were entered in the model as covariates. We constructed for each individual subject the statistical contrast “angry/fearful (negative) faces vs. neutral shapes” to identify the regional responses to negative emotion processing.

Genotyping and PRS

The procedures of genotyping and PRS computation were described in detail earlier and in the Supplement [33, 34, 42]. Briefly, the base sample was genotyped on microarrays with 10,901,146 SNPs imputed. The HCP sample was genotyped using Illumina Infinium Multi-Ethnic Genotyping Array (MEGA) or Infinium Neuro Consortium Array (2,292,654 SNPs). The 1000GP_Phase3 dataset (n = 2504; details in Supplementary Table S1) served as the reference panel for ancestry assignment, clumping, and linkage disequilibrium matrix construction. The PRS was computed with base (summary statistics of GWASs), target (whole-genome genotype and phenotype), and covariates (age, sex, and principal components of ancestry) data [43]. To cross-validate the racial composition of the base, target, and reference samples, we also estimated ancestry proportions; details are provided in the Supplement. Prior to further analyses, the PRS was normalized using Z-score transformation by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation.

Behavioral, whole-brain regression and region-of-interest (ROI) analyses

First, for the emotion task, accuracy and response time (RT) were averaged across blocks for face and shape conditions separately. We used the differences in accuracy and RT between matching negative faces and neutral shapes as behavioral indices. We performed chi-squared tests to examine sex difference in race composition. We performed a 2 (group: binger vs. non-binger) by 2 (sex: men vs. women) between-subject ANOVAs on age, drinking PC1, PRS, behavioral performance indices, and ASR measures. We computed the correlation coefficients of PC1 and PRS with the task behavioral indices and ASR measures in binge and non-binge drinkers separately. Age, sex (for all subjects), and race were included as covariates for all analyses.

For the imaging data, we first performed one-sample t tests to examine neural responses to negative emotions vs. neutral shapes in binge and non-binge drinkers separately.

We performed whole-brain regressions against PC1 and PRS in a single model in all, male, and female binge and non-binge drinkers separately, controlling for age, sex (for all), and race. We evaluated the results with uncorrected voxel p < 0.001 in combination with cluster p < 0.05 corrected for family-wise error (FWE) of multiple comparisons on the basis of Gaussian random field theory, with 5 voxels expected per cluster. We also performed an additional set of analyses with the first six principal components (PCs) of genetic ancestry included in the model.

For all significant clusters identified from whole-brain regressions in significant correlation with PC1 and PRS in binge and non-binge drinkers, respectively, we performed the ROI analyses by estimating β values of regional activation, computing the partial correlations of β’s with PC1 and PRS in each group, with age, sex, and race as covariates, and following up with slope tests to examine the differences of PC1 vs. PRS and binger vs. non-binger in the correlations. We performed slope tests to examine sex differences as well. Note that these slope tests did not represent “double-dipping” [44], as the regression maps were identified with a threshold and clusters showing significant correlations in one group might have just missed the threshold in the other group, and vice versa. Thus, direct tests of the slopes were needed to confirm group and sex differences.

To validate the slope test results, we conducted five-fold cross-validation and permutation tests, as detailed in the Supplement. In addition, we performed a whole-brain interaction model, with ‘group’ included as a two-level factor (binger and non-binger) and ‘PC1 × group’ and ‘PRS × group’ as interaction terms, while controlling for age, sex, and race. In binge and non-binge drinkers separately, we conducted whole-brain interaction models to assess sex differences in PC1 and PRS slopes, i.e., with ‘sex’ as a two-level factor (men and women) and ‘PC1 × sex’ and ‘PRS × sex’ as interaction terms, while controlling for age and race. The results were evaluated at the same threshold: voxel p < 0.001, uncorrected in combination with cluster p < 0.05 FWE corrected.

Results

Demographic, clinical, and behavioral measures

The descriptive statistics and results of F/χ² tests in age, race, drinking PC1, PRS, behavioral indices (accuracy rate and RT of negative vs. neutral condition) of the emotion task, and ASR measures (depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints) are shown in Table 1. With age and race as covariates, the sex-by-group interaction effect was significant for PC1 (F = 5.65, p = 0.018) but not for PRS (F = 0.04, p = 0.085) or for behavioral indices of the emotion task (F’s ≤ 0.08, p’s ≥ 0.775). Simple effect tests showed significant sex difference in PC1 in binge (men > women; p = 0.001) but not non-binge (p = 0.081) drinkers. Further, both male and female bingers relative to non-bingers showed significantly higher PC1 (p’s < 0.001). The main effects of sex or of group were not significant for PRS (F’s ≤ 3.71, p’s ≥ 0.055) or for behavioral indices of the emotion task (F’s ≤ 0.43, p’s ≥ 0.514). Neither sex-by-group interaction effect (F’s ≤ 0.77, p’s ≥ 0.380) nor the main effects of sex (F’s ≤ 0.15, p’s ≥ 0.698) or of group (F’s ≤ 2.28, p’s ≥ 0.131) were significant for any of the ASR measures.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and behavioral measures of male and female binge and non-binge drinkers.

| Men (n = 211) | Women (n = 265) | sex-by-group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| binger | non-binger | binger | non-binger | |||

| (n = 69) | (n = 142) | (n = 28) | (n = 237) | F | p | |

| Age (years) | 27.25 ± 3.62 | 27.42 ± 3.89 | 28.57 ± 4.00 | 29.84 ± 3.59 | 1.44 | 0.231 |

| Race | χ² = 9.39, p = 0.094 | χ² = 1.74, p = 0.884 | ||||

| AI/AN | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| A/NH/OPI | 4 (5.8%) | 10 (7.0%) | 1 (3.6%) | 11 (4.6%) | ||

| AA | 3 (4.3%) | 24 (16.9%) | 5 (17.9%) | 42 (15.8%) | ||

| White | 59 (85.5%) | 103 (72.5%) | 22 (78.6%) | 171 (72.2%) | ||

| > one race | 2 (2.9%) | 4 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | ||

| UK/NR | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (3.0%) | ||

| Drinking PC1 | 1.56 ± 0.57 | −0.71 ± 0.62 | 1.11 ± 0.50 | −0.82 ± 0.54 | 5.65 | 0.018 |

| PRS | 3.58 ± 0.80 | 3.38 ± 0.84 | 3.57 ± 0.74 | 3.32 ± 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.850 |

| ACCU (F-S), % | 1.7 ± 3.8 | 2.1 ± 4.8 | 2.3 ± 4.9 | 1.7 ± 4.3 | 0.73 | 0.392 |

| RT (F-S), ms | 17.9 ± 79.4 | 14.9 ± 77.2 | 21.9 ± 75.4 | 15.5 ± 86.1 | 0.08 | 0.775 |

| Depression | 52.3 ± 3.3 | 53.9 ± 5.7 | 52.8 ± 4.9 | 53.2 ± 5.0 | 0.77 | 0.380 |

| Anxiety | 52.9 ± 4.5 | 52.9 ± 4.7 | 52.6 ± 4.9 | 53.1 ± 5.3 | 0.12 | 0.727 |

| Somatic Comp. | 53.6 ± 4.7 | 53.9 ± 5.9 | 53.6 ± 5.3 | 53.6 ± 5.7 | 0.13 | 0.723 |

The two-way between-subject ANOVA tests for drinking PC1 and PRS were performed with age and race as covariates.

AI/AN american indian/alaskan native, A/NH/OPI asian/native hawaiian/other pacific islander, AA african American, UK/NR unknown/not reported, PC1 first component of drinking metrics, PRS polygenic risk score, ACCU accuracy, RT response time, F-S face minus shape, somatic comp, somatic complaints.

Bold p values indicate significant sex-by-group interaction effect.

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

In the entire sample (n = 1074) where the PRS was computed, the correlation between PC1 and PRS was significant (r = 0.15, p < 0.001). For the current cohort of binge and non-binge drinkers included in this study, the correlation between PC1 and PRS was also significant (r = 0.12, p = 0.010). In binge drinkers, higher PC1 (r = 0.21, p = 0.041) and PRS (r = 0.21, p = 0.040) were significantly correlated with greater symptom severity of somatic complaints, but not with depression (r’s ≤ 0.20, p’s ≥ 0.054) or anxiety (r’s ≤ 0.18, p’s ≥ 0.076). In non-binge drinkers, neither PC1 nor PRS was significantly correlated with any of the ASR measures (r’s ≤ 0.06, p’s ≥ 0.264).

Negative emotion processing correlates of drinking severity and PRS

One-sample t-tests revealed widespread activation in response to negative faces compared to neutral shapes in both binge (Supplementary Figure S1A) and non-binge (Supplementary Figure S1B) drinkers, consistent with previous studies [41, 45, 46].

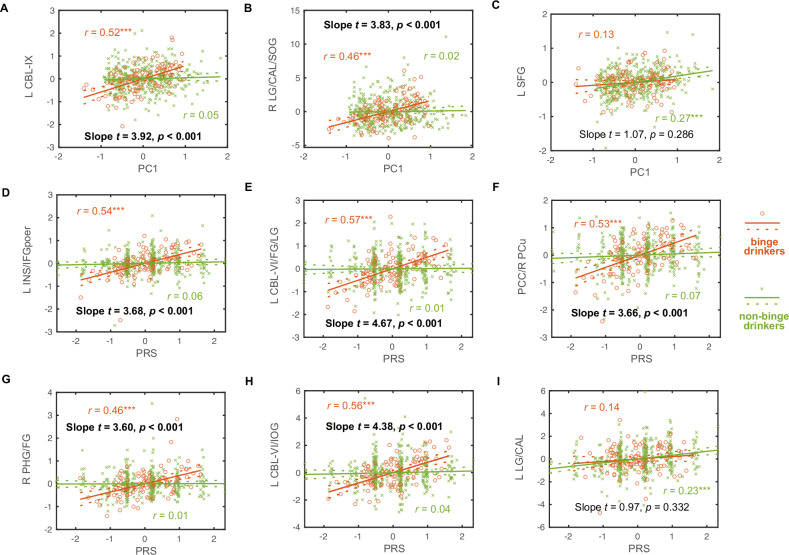

Figure 1 (binge drinkers) and Fig. 2 (non-binge drinkers) show regional activation to negative emotion processing in positive correlation with PC1 and PRS in all, men, and women, with PC1 and PRS modeled together and age, sex (for all), and race as covariates. The clusters in positive correlation with PC1 or PRS are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. No regions showed negative correlations with PC1 or PRS at the same threshold.

Fig. 1. Emotion-related brain responses linked to drinking severity and polygenic risk score (PRS) in binge drinkers.

A All, B men, and C women. PC1 and PRS were modeled together in the whole-brain regression, with age, sex (for all subjects), and race as covariates. The results were evaluated at voxel p < 0.001, uncorrected in combination with cluster p < 0.05 family-wise error (FWE) corrected. No clusters showed significant negative correlations. Color bar shows voxel T and Cohen’s d values. L: left; R: right; CBL: cerebellum; FG: fusiform gyrus; LG: lingual gyrus; PHG: parahippocampal gyrus; INS: insula; IFGoper: inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis; IOG: inferior occipital gyrus; CAL: calcarine sulcus; SOG: superior occipital gyrus; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; PCu: precuneus; IFGorb: inferior frontal gyrus pars orbitalis; IFGtri: inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis; MOG: middle occipital gyrus; IPG: inferior parietal gyrus; Nil: no significant findings.

Fig. 2. Regional brain activations to negative emotion processing in correlation with drinking severity (PC1) and polygenic risk score (PRS) in non-binge drinkers.

A all, B men, and C women. PC1 and PRS were modeled together in the whole-brain regression, with age, sex (for all subjects), and race as covariates. The results were evaluated at voxel p < 0.001, uncorrected in combination with cluster p < 0.05 family-wise error (FWE) corrected. No significant negative correlates were identified. Color bar shows voxel T and Cohen’s d values. L: left; LG: lingual gyrus; CAL: calcarine sulcus; SFG: superior frontal gyrus; SMA: supplementary motor area; Nil: no significant findings.

For all binge drinkers, higher PC1 was correlated with greater activation of left cerebellum lobule IX and right lingual/calcarine/superior occipital gyri and higher PRS was correlated with greater activation of a wide array of frontal, parietal and occipital regions and the insula. Almost all these clusters were identified in male binge drinkers while none of them were significant in female binge drinkers. Evaluated at the same threshold, no clusters showed responses in significant negative correlation with PC1 or with PRS in binge drinkers.

For non-binge drinkers, higher PC1 was significantly correlated with greater activation of left superior frontal gyrus in all and bilateral supplementary motor area in women alone and higher PRS was significantly correlated with greater activation of left lingual gyrus and calcarine sulcus across all subjects. No clusters showed responses in significant negative correlation with PC1 or with PRS in non-binge drinkers.

The findings remained largely consistent with the first six ancestry PCs included as additional covariates (Supplementary Figure S2 for binge drinkers and Figure S3 for non-binge drinkers). The clusters are summarized in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 2 summarizes these correlations as well as the slope test results for PC1 vs. PRS in binge and non-binge drinkers separately. A total of nine clusters showed a significant correlation with PC1 or with PRS either in binge or non-binge drinkers. Thus, with a p-value of 0.05/9 = 0.006 to correct for multiple comparisons, we evaluated whether these correlates were specific to PC1 or PRS. The results showed that the correlate in the left cerebellum lobule IX was specific to PC1 in binge drinkers. The correlates of left insula/inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis, left cerebellum lobule VI/fusiform/lingual gyri, bilateral middle cingulate cortex/right precuneus, and left cerebellum lobule VI/inferior occipital gyrus were specific to PRS in binge drinkers. For non-binge drinkers, the correlate in the left superior frontal gyrus was specific to PC1 and the correlate of left lingual gyrus and calcarine sulcus was specific to PRS.

Table 2.

Correlations of regional activation to negative emotion processing with PC1 and PRS in binge and non-binge drinkers and slope tests.

| binge drinkers | non-binge drinkers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PRS | Slope t (p) PC1 vs. PRS |

PC1 | PRS | Slope t (p) PC1 vs. PRS |

|

| PC1-related in bingers | ||||||

| L CBL-IX | 0.52*** | −0.02 | 3.30 (0.001) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 (0.995) |

| R LG/CAL/SOG | 0.46*** | 0.05 | 2.35 (0.020) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.965) |

| PRS-related in bingers | ||||||

| L INS/IFGoper | 0.10 | 0.54*** | −4.06 ( < 0.001) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.56 (0.572) |

| L CBL-VI/FG/LG | 0.05 | 0.57*** | −4.75 ( < 0.001) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.43 (0.664) |

| PCC/R PCu | 0.10 | 0.53*** | −3.96 ( < 0.001) | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.75 (0.453) |

| R PHG/FG | 0.21 | 0.46*** | −2.61 (0.010) | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.88 (0.380) |

| L CBL-VI/IOG | −0.08 | 0.56*** | −5.48 ( < 0.001) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 (0.959) |

| PC1-related in non-bingers | ||||||

| L SFG | 0.13 | 0.27 | 1.37 (0.173) | 0.27*** | −0.01 | 3.09 (0.002) |

| PRS-related in non-bingers | ||||||

| L LG/CAL | −0.03 | 0.14 | 1.24 (0.215) | −0.02 | 0.23*** | −4.02 ( < 0.001) |

Note that, although the slope tests were meant for regional activities that were significant correlates of PC1 or PRS, we showed all results for completeness.

PC1 drinking severity, PRS polygenic risk score, L left, R right, CBL cerebellum, LG lingual gyrus, CAL calcarine sulcus, SOG superior occipital gyrus, INS insula, IFGoper inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis, FG fusiform gyrus, PCC posterior cingulate cortex, PCu precuneus, PHG parahippocampal gyrus, IOG inferior occipital gyrus, SFG superior frontal gyrus.

Slope test results in bold for p < 0.05/9 = 0.006 for multiple comparisons.

***p < 0.05/(9 × 4) = 0.001389.

In addition to testing for PC1 or PRS specificity of the correlates, we also examined whether these correlates were specific to binge or non-binge drinkers. Figure 3 showed group differences (binger vs. non-binger) in the correlations of regional activation to negative emotion processing with drinking PC1 and PRS. Slope tests confirmed that the correlations of regional responses identified from whole-brain regressions were significantly stronger in binge than in non-binge drinkers (Fig. 3A, B, and D–H). However, there were no significant group differences in the correlations of regional responses identified from whole-brain regressions in non-binge drinkers (Fig. 3C, I). The 5-fold cross-validation supported the findings (see Supplementary Table S5).

Fig. 3. Group differences between binge (orange circle) and non-binge drinkers (green cross) in the correlations of regional activation to negative emotion processing with drinking PC1 and PRS.

(A) PC1 vs. L CBL-IX; (B) PC1 vs. LG/CAL/SOG; (C) PC1 vs. L SFG; (D) PRS vs. L INS/IFGoper; (E) PRS vs. L CBL-VI/FG/LG; (F) PRS vs. PCC/R PCu; (G) PRS vs. R PHG/FG; (H) PRS vs. L CBL-VI/IOG; and (I) PRS vs. L LG/CAL. Note that (A), (B), and (D) to (H) show the clusters identified from whole-brain regressions in binge drinkers, while (C) and (I) show those identified in non-binge drinkers. The data points represent residuals after controlling for age, sex, and race. Solid and dashed lines represent the regressions and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The coefficients r’s values for the correlations [***p < 0.05/(9×2) = 0.00278] as well as slope t’s and p’s values for group differences in the correlations are presented. Slope test results in bold for p < 0.05/9 = 0.00556 to correct for multiple comparisons. Note: PRS: polygenic risk score; L: left; R: right; CBL: cerebellum; LG: lingual gyrus; CAL: calcarine sulcus; SOG: superior occipital gyrus; INS: insula; IFGoper: inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis; FG: fusiform gyrus; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; PCu: precuneus; PHG: parahippocampal gyrus; IOG: inferior occipital gyrus; SFG: superior frontal gyrus.

Considering these two sets of regressions and slope tests, binge drinkers showed PC1-specific regional activities in the left cerebellum lobule IX and PRS-specific regional activities in the left insula, inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis, cerebellum lobule VI, and fusiform, lingual and inferior occipital gyri, bilateral posterior cingulate cortex, and right precuneus, all in positive correlation. In contrast, non-binge drinkers showed PC1-specific regional activities in the left superior frontal gyrus and PRS-specific regional activities in the left lingual gyrus and calcarine sulcus, all in positive correlation. Furthermore, only those neural markers of PC1 and PRS identified from binge drinkers were specific to binge drinkers, but not vice versa.

The whole-brain interaction model showed that binge relative to non-binge drinkers had greater PRS slopes in the left cerebellum lobule VI, fusiform and lingual gyri, and insula, right precuneus, and bilateral posterior cingulate cortex (Supplementary Figure S4). These results align with the findings of post-hoc slope tests, though the interaction model identified fewer clusters. Similarly, we did not identify any clusters showing greater PRS slope in non-binge relative to binge drinkers or in PC1 slope in either direction.

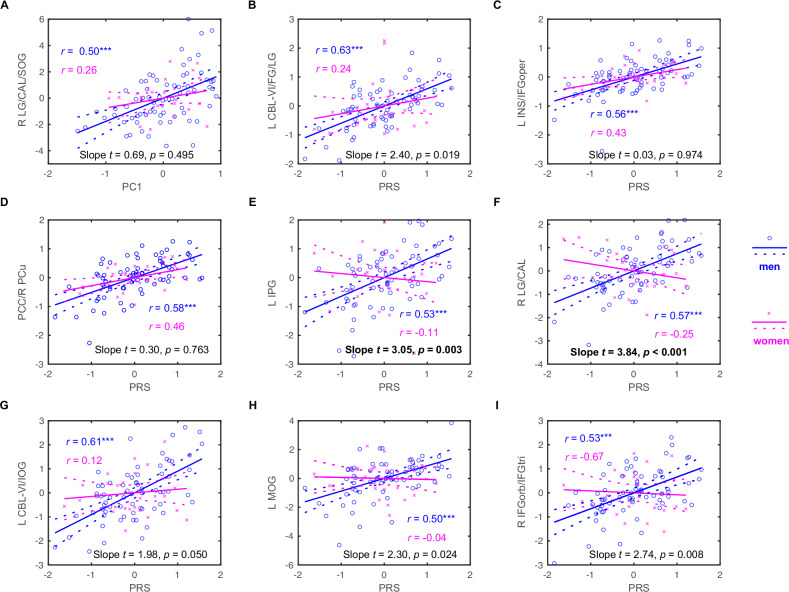

Sex differences in binge drinkers

Figure 4 shows sex differences in the correlations of regional activation to negative emotion processing with drinking PC1 and PRS in binge drinkers. Specifically, slope tests confirmed that the correlation between the activation of left inferior parietal gyrus and right lingual and calcarine gyri and PRS was stronger in men as compared to in women, evaluated with a p < 0.05/9 = 0.00556 to correct for multiple comparisons. The 5-fold cross-validation supported the findings (see Supplementary Table S6). However, the whole-brain interaction models did not show any clusters with significant sex differences in PC1 or PRS slope among binge or non-binge drinkers. This may be attributed to the small sample size and more stringent corrections applied in the whole-brain interaction models.

Fig. 4. Sex differences in the correlations of regional activation to negative emotion processing with drinking PC1 and PRS in binge drinkers (men: blue circle; women: magenta cross).

(A) PC1 vs. R LG/CAL/SOG; (B) PRS vs. L CBL-VI/FG/LG; (C) PRS vs. L INS/IFGoper; (D) PRS vs. PCC/R PCu; (E) PRS vs. L IPG; (F) PRS vs. R LG/CAL; (G) PRS vs. L CBL-VI/IOG; (H) PRS vs. L MOG; and (I) PRS vs. R IFGorb/IFGtri. The data points represent residuals after controlling for age and race. Solid and dashed lines represent the regressions and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The coefficients r’s values for the correlations [***p < 0.05/(9 × 2) = 0.000278] as well as slope t’s and p’s values for sex differences in the correlations are presented. Slope test results in bold for p < 0.05/9 = 0.00556 for multiple comparisons. Note: PRS: polygenic risk score; L: left; R: right; LG: lingual gyrus; CAL: calcarine sulcus; SOG: superior occipital gyrus; CBL: cerebellum; FG: fusiform gyrus; INS: insula; IFGoper: inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; PCu: precuneus; IPG: inferior parietal gyrus; IOG: inferior occipital gyrus; MOG: middle occipital gyrus; IFGorb/IFGtri: inferior frontal gyrus pars orbitalis and triangularis.

Discussion

We aimed to identify neural markers of negative emotion processing in association with drinking severity (PC1) and genetic risks (PRS) for alcohol misuse in binge and non-binge drinkers and to investigate sex differences in these neural markers. To this end we employed a single regression model where both PC1 and PRS served as independent variables or predictors, so that the effects of alcohol exposure and genetic risks were mutually accounted for. We did not find significant group differences in the behavioral indices of the emotion task or significant relationships between behavioral indices and either PRS or PC1. We observed regional responses in positive correlation with PC1 and PRS in both groups and, as confirmed by slope tests, regional activities specific to PRS, to binge drinkers, and to both PRS and binge drinkers. We also observed significant sex differences in the PRS correlates, with men but not women showing regional activities in link with the genetic risks of alcohol dependence. We discussed the main findings in the below.

PC1, PRS, and negative emotions

Both PC1 and PRS were significantly associated with the symptom severity of somatic complaints, but the correlation just missed the threshold for depression or anxiety, in binge drinkers. Bingers frequently report somatic problems, including fatigue, headache, poor sleep, and pain, particularly during withdrawal [47–49]. Somatic complaints may precede and predict the onset of depression in a community sample of healthy adults [50, 51]. Other studies identified somatic symptoms as a preclinical marker of depression and anxiety [52, 53] and highlighted the importance of recognizing the presentation of somatic symptoms in the diagnosis and management of clinical depression [54–56]. This literature along with our current and earlier findings [33] supports somatic complaints as an important phenotype for exploring the genetic underpinnings of alcohol misuse and its comorbidities.

PC1-related neural markers of negative emotion processing

We found that, consistent with previous research, binge relative to non-binge drinkers showed stronger activation of a cluster in the left posterior cerebellum (lobule IX) and another spanning the lingual gyrus, calcarine sulcus, and superior occipital gyri in correlation with drinking severity (Fig. 1). For example, binge as compared to non-binge drinkers exhibited higher activation in the left cerebellum during anger processing, with the activity correlated with drinking severity among binge drinkers [57]. This finding is also in line with recent studies of the roles of the cerebellum in emotional processing [58–60] and in manifesting emotional problems observed in individuals with alcohol misuse [61]. Moreover, the slope test confirmed that the PC1-associated cerebellar lobule IX responses were more indicative of the impact of alcohol consumption than genetic factors.

Visuo-perceptual impairments are among some of the most commonly reported deficits, implicating occipital cortical dysfunction, in AUD [62, 63]. Notably, studies have suggested a role of the occipital cortex in emotion processing [64, 65], as well as emotion decoding dysfunction [66] and contribution of alcohol-induced neurotoxicity in the occipital cortex to exacerbation of emotional deficits [67] in AUD. Although slope test of the regression on PC1 vs. PRS did not reach significance after correcting for multiple comparisons, the robust correlations of PC1-occipital cortical responses may suggest more of an effect of alcohol consumption in binge drinkers.

Non-binge drinkers showed a PC1-specific association with neural activity in the left superior frontal gyrus (SFG), though not significantly stronger than that observed in binge drinkers. Given the considerably lower drinking severity in non-binge as compared to binge drinkers, this may suggest a role of the left SFG in regulating alcohol consumption during early stages of drinking in non-bingers. Our prior findings implicated bilateral SFG in win and loss processing in the monetary incentive delay task where its activity was positively associated with the severity of both drinking and depressive symptoms in social drinkers [68]. Another study reported reduction in negative emotion-related activation in the SFG during inhibitory control in an emotion Go/Nogo task in association with more binging episodes over the past 3 months in bingers [69]. These findings collectively suggest a role of the SFG in integrating emotion, inhibitory control, and reward processing as well as potentially in the decisions to refrain from drinking, which figure more prominently in non-binge drinkers.

Overall, we identified fewer regional responses to negative emotion processing that were specific to drinking severity than to PRS, likely because the HCP sample consisted largely of social drinkers. In addition to the cerebellum and occipital areas as discussed above, prior research has implicated the salience, default mode, limbic, and sensorimotor networks in emotion processing deficits and alcohol misuse [70–72]. For example, individuals with AUD and those who relapsed earlier in treatment as compared to their controls showed reduced activation in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex during emotional modulation [73]. Studies with a larger sample and more heavy drinkers and with other behavioral paradigms may help in clarifying and contrasting the neural correlates of drinking severity and genetic risks of problem drinking.

PRS-related neural markers of negative emotion processing

We observed elevated brain response to negative emotion in a broad range of regions, all showing a positive correlation with the polygenic risks. Slope tests showed that these regional activities were specific to binge drinkers and to genetic risks except for the cluster in the right parahippocampal and fusiform gyri. The parahippocampal gyrus, a core region of the ventral visual stream, is widely implicated in emotion processing [74] and drug craving [75]. The parahippocampal and fusiform gyri showed activation in positive correlation with the severity of alcohol misuse during loss processing – a negative emotional state – in a monetary incentive delay task among social drinkers [68]. An earlier study also reported higher activity of the parahippocampal gyrus in response to negative vs. neutral images in patients with AUD relative to controls [76]. Thus, parahippocampal dysfunction in emotion processing may be related both to the effects of chronic alcohol consumption and to genetic predisposition to problem drinking, as we have observed here (Table 2).

In contrast, emotion-related activities in a large swath of frontoparietal areas (inferior frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus), occipital regions (fusiform and lingual gyri, inferior occipital gyrus), as well as the insula and cerebellum lobule VI, appeared to reflect specifically the genetic risks in binge drinkers. While these structures have been implicated in alcohol misuse, emotional dysfunction, and other psychological processes critical to addiction, such as craving [77–79], there has been less evidence connecting these regional activities to genetic risks of alcohol misuse.

Previous research showed altered brain structures and functions in healthy individuals with a family history of AUD (FH + ) as compared to those without such a history (FH-). For example, AUD FH+ relative to FH- healthy young adults showed reduced gray matter volumes (GMVs) of the insula, superior and inferior frontal gyri, ACC, parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, thalamus, and cerebellum [80, 81] and higher activations in the insula and inferior frontal gyrus during affective processing in a theory of mind task [82]. Alcohol-naïve FH+ vs. FH- adolescents showed reduced resting state functional connectivities between the posterior parietal cortex and left insula and lingual gyrus, and right cuneus, fusiform and inferior temporal gyri [83] and increased activation in bilateral orbitofrontal gyri during negative emotion processing [84]. These findings suggest that genetic risks of alcohol misuse may influence the neural processes of social cognition and negative emotions.

While few studies have explored the relationship between PRS for alcohol misuse and brain function and dysfunction, growing evidence indicates that higher PRS for externalizing behaviors including alcohol misuse may be associated with structural brain changes in regions involved in reward processing, emotional regulation, and cognitive control. For instance, the PRS for risky behaviors across the domains of drinking, smoking, driving, and sexual behaviors was negatively correlated with GMVs of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, putamen, and hypothalamus [85]. Higher PRS for problem alcohol use was associated with lower GMVs in the left frontal pole, larger surface areas of the right insula and inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, lower cortical thickness of the left inferior frontal gyrus pars orbitalis and opercularis and right lateral orbitofrontal gyrus, as well as greater cortical thickness of the right supramarginal gyrus [86]. In our recent work, we reported higher GMVs of the lingual gyri in association with the PRS for alcohol misuse [42]. The current findings along with this literature highlight structural and functional brain markers of negative emotion processing in people genetically vulnerable to alcohol misuse.

Sex differences in PRS-related markers in binge drinkers

We found higher drinking severity and more prominent PRS-related neural markers in male than in female binge drinkers. These findings clearly suggest the importance of considering sex as a biological variable in studies of the genetic susceptibility and neural markers of alcohol misuse [87]. However, the difference in the case-to-control ratio between males (1:2) and females (1:10) may impact the statistical power of sex comparisons. This discrepancy reflects the underlying sample distribution of the HCP data and limits the generalizability of sex-specific findings. We suggest use of caution in interpreting sex-related findings and encourage replication in larger, more evenly distributed samples. While our analyses accounted for sex as a covariate, future studies with more balanced case-control ratios are needed to confirm these effects.

Previous research has examined sex differences in the neural phenotypes of alcohol use severity, with very limited evidence on genetic risks [25, 27, 88]. Abstinent men with a history of AUD as compared to non-drinking controls exhibited greater activity in the superior frontal cortex in response to negative faces, a difference that was more pronounced than that observed in females [89]. Male relative to female social drinkers showed greater activation to stress-related cues in brain regions involved in emotional modulation, including the medial PFC, rostral ACC, posterior insula, putamen, amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, temporal lobe, superior parietal lobe, lingual gyrus, and cerebellum [90]. Some of these regional activities were also identified here in correlation with PRS in male bingers, suggesting their roles in the potentially sex-specific neural pathways underlying negative emotion processing and genetic risks of alcohol misuse.

Our sex-specific findings also align with other studies. For example, higher PRS for AUD was associated with increased fronto-central, tempo-parietal, centro-parietal, and parietal-occipital interhemispheric theta and alpha connectivity in male but not in female healthy young FH+ adults [91]. A longitudinal study found a significant age-by-sex interaction during negative emotion processing among alcohol-naïve FH+ adolescents, with boys but not girls showing a significant age-related decrease in amygdala and precentral gyrus response to negative emotion [87]. More broadly on sex differences, adult G-G carriers in two SNPs (rs279858 and rs279826) and haplotypes of γ-amino butyric acid α2 receptor subunit (GABRA2) gene were more likely to have more severe alcohol dependence, higher impulsivity, and stronger insula activation during reward and loss anticipation in a monetary incentive delay task, with stronger effects observed in women [92]. It remains to be seen whether PRS for alcohol dependence may be reflected in the neural markers of other cognitive or motivational processes specifically in women or across sexes.

With slope tests we confirmed sex differences in the correlations between PRS and regional activation in the left inferior parietal and right lingual gyrus/calcarine sulcus during negative emotion processing in binge drinkers, at a corrected threshold for multiple comparisons. A longitudinal study demonstrated that, across sex and ancestry, lower occipital and parietal cortical gamma activity at baseline distinguished adolescents who developed AUD and those who did not after seven years, suggesting that altered electrical activity in the posterior cortex as a risk marker of AUD [93]. Our findings further linked emotion processing dysfunction in these posterior brain regions to genetic risks and sex differences in this risk marker.

Greater activation in the right PCC/precuneus and left insula/IFG showed significant correlation with higher PRS both in men (r = 0.58 and 0.56, p’s < 0.000278) and, though short of a corrected threshold, in women (r = 0.46, p = 0.019 and r = 0.43, p = 0.030). As key regions of the default mode network [94–96], the PCC and precuneus have been shown to be disrupted in AUD [97, 98]. The insula and IFG of the salience network have also been implicated in responses to alcohol-related stimuli as well as behavioral control and decision making in AUD [99, 100]. If validated in a larger sample with a balanced sex distribution, these findings would suggest sex-shared neural correlates of the genetic risks of alcohol misuse.

Moreover, future research may leverage larger sample sizes that allow for the stratification of participants of high and low PRS in data analyses [16]. Additionally, integrating multimodal imaging measures may provide additional perspectives in disentangling the neural correlates of genetic risks for AUD from those associated with drinking severity [101].

Limitations and conclusions

The study has a few limitations. First, HCP participants were neurotypical young adults without significant drinking problems, as individuals requiring treatment were excluded. Therefore, the current findings are specific to this sample. Notably, no brain regions demonstrated activation in correlation with PC1 in any group or either sex, likely reflecting the characteristics of this largely social-drinking population. Second, recent reviews suggested that women and men are more likely to drink for negative reinforcement (e.g., to alleviate stress) and for positive reinforcement (e.g., to seek stimulation), respectively, which may reflect sex differences in the neurobiological underpinnings of alcohol use and misuse [102, 103]. Here, we did not observe any female-specific neural markers of genetic risks or of use severity, likely because of a predominantly male sample in our binge drinkers. Future studies would benefit from a larger sample with higher representation of women to revisit this issue. Third, subsequent research could explore alternative phenotypes in the computation of PRS, providing deeper insights into how genetic factors contribute to alcohol misuse across a broader behavioral spectrum [104, 105]. In addition, we focused on genetic risks and did not consider environmental factors of alcohol misuse, which are known to show sex differences [106, 107]. Work is warranted to investigate how environmental factors, genetic risks, and their interaction may shape neural markers of alcohol misuse and whether these effects are influenced by sex. Moreover, future studies may incorporate a two-visit design to evaluate the stability and reproducibility of neural markers associated with PRS and PC1. Finally, nicotine or other drugs may have additive or interactive effects on emotional processing [108]. We did not account for the use of other substances or, as reviewed earlier, other behavioral traits (e.g., impulsivity) that may associate with drinking or the genetic risks of dependence in our analyses.

In conclusion, we identified altered neurobiological processes of negative emotion in correlation with genetic risks for alcohol misuse in binge drinkers and highlighted sex differences in the findings. Genetic risk factors for alcohol dependence may dispose individuals to impaired negative emotion processing, which could in turn contribute to problem drinking. Our findings of sex-specific PRS-related neural responses during emotion processing may help in the development of treatments to prevent the escalation of drinking.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by NIH grants AG072893 and DA051922. The NIH is otherwise not responsible for the conceptualization of the study, data collection and analysis, or in the decision in publishing the results.

Author contributions

Yu Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization. Xingguang Luo: Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Huey-Ting Li: Software, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Guangfei Li: Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Jaime S. Ide: Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Chiang-Shan R. Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition.

Data availability

We have obtained permission from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) to use the Open and Restricted Access data for the current study. Data were provided by the WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Data used in this study were obtained from the Human Connectome Project (HCP). The HCP was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB #201204036). Informed consent was obtained from all participants by the HCP investigators at the time of data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yu Chen, Xingguang Luo.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-025-03719-3.

References

- 1.Grigsby TJ, Hoopsick R, Barker D, Devier E, Amis A, Yockey RA. Substance use and sexual orientation among adolescents: Differences by age group and sex in the 2023 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. The American Journal on Addictions. 2025:1–8. 10.1111/ajad.70087. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lannoy S, Duka T, Carbia C, Billieux J, Fontesse S, Dormal V, et al. Emotional processes in binge drinking: a systematic review and perspective. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;84:101971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekman NM, Winward JL, Lau LL, Wagner CC, Brown SA. The impact of adolescent binge drinking and sustained abstinence on affective state. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1432–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbia C, Lannoy S, Maurage P, López-Caneda E, O’Riordan KJ, Dinan TG, et al. A biological framework for emotional dysregulation in alcohol misuse: from gut to brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:1098–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowin JL, Manza P, Ramchandani VA, Volkow ND. Neuropsychosocial markers of binge drinking in young adults. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:4931–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Garcia JM, Suarez-Suarez S, Doallo S, Cadaveira F. Effects of binge drinking during adolescence and emerging adulthood on the brain: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;137:104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelan R, Watts R, Orr CA, Althoff RR, Artiges E, Banaschewski T, et al. Neuropsychosocial profiles of current and future adolescent alcohol misusers. Nature. 2014;512:185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurage P, Bestelmeyer PE, Rouger J, Charest I, Belin P. Binge drinking influences the cerebral processing of vocal affective bursts in young adults. Neuroimage: Clin. 2013;3:218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trudell JR, Messing RO, Mayfield J, Harris RA. Alcohol dependence: molecular and behavioral evidence. Trends Pharm Sci. 2014;35:317–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducci F, Goldman D. Genetic approaches to addiction: genes and alcohol. Addiction. 2008;103:1414–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhulst B, Neale MC, Kendler KS. The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1061–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis CM, Vassos E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 2020;12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage JE, Salvatore JE, Aliev F, Edwards AC, Hickman M, Kendler KS, et al. Polygenic risk score prediction of alcohol dependence symptoms across population-based and clinically ascertained samples. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42:520–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor M, Simpkin AJ, Haycock PC, Dudbridge F, Zuccolo L. Exploration of a polygenic risk score for alcohol consumption: a longitudinal analysis from the ALSPAC cohort. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0167360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson EC, Sanchez-Roige S, Acion L, Adams MJ, Bucholz KK, Chan G, et al. Polygenic contributions to alcohol use and alcohol use disorders across population-based and clinically ascertained samples. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai D, Johnson EC, Colbert S, Pandey G, Chan G, Bauer L, et al. Evaluating risk for alcohol use disorder: polygenic risk scores and family history. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022;46:374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevilacqua L, Goldman D. Genetics of emotion. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:401–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Heath AC. Heritability of individual differences in cortical processing of facial affect. Behav Genet. 2010;40:178–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park HR, Chilver MR, Quidé Y, Montalto A, Schofield PR, Williams LM, et al. Heritability of cognitive and emotion processing during functional MRI in a twin sample. Hum Brain Mapp. 2024;45:e26557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesch KP. Alcohol dependence and gene x environment interaction in emotion regulation: Is serotonin the link?. Eur J Pharm. 2005;526:113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Icick R, Shadrin A, Holen B, Karadag N, Lin A, Hindley G, et al. Genetic overlap between mood instability and alcohol-related phenotypes suggests shared biological underpinnings. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:1883–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linner KR, Mallard TT, Barr PB, Sanchez-Roige S, Madole JW, Driver MN, et al. Multivariate analysis of 1.5 million people identifies genetic associations with traits related to self-regulation and addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:1367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ksinan AJ, Su J, Aliev F, Spit for Science Workgroup, Dick DM. Unpacking genetic risk pathways for college student alcohol consumption: the mediating role of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43:2100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker JB, McClellan ML, Reed BG. Sex differences, gender and addiction. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:136–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores-Bonilla A, Richardson HN. Sex differences in the neurobiology of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res: Curr Rev. 2020;40:04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King AC, Bernardy NC, Hauner K. Stressful events, personality, and mood disturbance: gender differences in alcoholics and problem drinkers. Addict Behav. 2003;28:171–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padula CB, Anthenelli RM, Eliassen JC, Nelson E, Lisdahl KM. Gender effects in alcohol dependence: an fMRI pilot study examining affective processing. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, Chen Y, Chaudhary S, Tang X, Li CR. Loss and frontal striatal reactivities characterize alcohol use severity and rule-breaking behavior in young adult drinkers. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2022;7:1007–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong Y, Li G, Wang S, Su Y, Li S, Sun Z, et al. Reduction in valence-differentiating neural activities in binge drinking and its comorbidities: an exploratory study of the human connectome project data. Journal Alcohol, drug Abus Subst Depend. 2024;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li G, Le TM, Wang W, Zhornitsky S, Chen Y, Chaudhary S, et al. Perceived stress, self-efficacy, and the cerebral morphometric markers in binge-drinking young adults. NeuroImage: Clin. 2021;32:102866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li G, Chen Y, Le TM, Zhornitsky S, Wang W, Dhingra I, et al. Perceived friendship and binge drinking in young adults: A study of the Human Connectome Project data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;224:108731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA. 1994;272:1672–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Li H-T, Luo X, Li G, Ide J, Li CR. Polygenic risk for depression and resting state functional connectivity of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in young adults. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2025;50:E31–E44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu X, Chen Y, Luo X, Ide JS, Li CR. Gray matter volumetric correlates of the polygenic risk of depression: a study of the human connectome project data. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024;87:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Chaudhary S, Li G, Fucito LM, Bi J, Li CR. Deficient sleep, altered hypothalamic functional connectivity, depression and anxiety in cigarette smokers. Neuroimage: Rep. 2024;4:100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, et al. Semi-structured assessment for the genetics of alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1994. 10.1037/t03926-000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Achenbach TM. DSM-oriented guide for the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). ASEBA2013.

- 38.Hariri AR, Tessitore A, Mattay VS, Fera F, Weinberger DR. The amygdala response to emotional stimuli: a comparison of faces and scenes. Neuroimage. 2002;17:317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barch DM, Burgess GC, Harms MP, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL, Corbetta M, et al. Function in the human connectome: task-fMRI and individual differences in behavior. Neuroimage. 2013;80:169–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Zhang S, Le TM, Tang X, Li CR. Neural responses to negative facial emotions: sex differences in the correlates of individual anger and fear traits. Neuroimage. 2020;221:117171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhary S, Zhang S, Zhornitsky S, Chen Y, Chao HH, Li CR. Age-related reduction in trait anxiety: behavioral and neural evidence of automaticity in negative facial emotion processing. Neuroimage. 2023;276:120207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Li H-T, Luo X, Li G, Ide J, Li CR. The effects of alcohol use severity and polygenic risk on gray matter volumes in young adults. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1560053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi SW, Mak TS-H, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:2759–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Ide JS, Li CS, Chaudhary S, Le TM, Wang W, et al. Gray matter volumetric correlates of dimensional impulsivity traits in children: sex differences and heritability. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:2634–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preckel K, Trautwein F-M, Paulus FM, Kirsch P, Krach S, Singer T, et al. Neural mechanisms of affective matching across faces and scenes. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaudhary S, Wong HK, Chen Y, Zhang S, Li CR. Sex differences in the effects of individual anxiety state on regional responses to negative emotional scenes. Biol Sex Differ. 2024;15:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayasiri G, Richman JA, Rospenda KM. The great recession, somatic symptomatology and alcohol use and abuse. Addict Behav. 2012;37:1019–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benzi IMA, Stival C, Gallus S, Odone A, Barone L. Exploring patterns of alcohol consumption in adolescence: the role of health complaints and psychosocial determinants in an italian sample. Int J Ment Health and Addict. 2025;3:1124–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conway KP, Vullo GC, Nichter B, Wang J, Compton WM, Iannotti RJ, et al. Prevalence and patterns of polysubstance use in a nationally representative sample of 10th graders in the United States. Journal Adolesc Health. 2013;52:716–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipowski ZJ. Somatization and depression. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terre L, Poston WSC, Foreyt J, St. Jeor ST. Do somatic complaints predict subsequent symptoms of depression?. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hein S, Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F, Ptok U, Heun R. Lifetime depressive and somatic symptoms as preclinical markers of late-onset depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le Roux H, Gatz M, Wetherell JL. Age at onset of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kapfhammer H-P. Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCauley E, Carlson GA, Calderon R. The role of somatic complaints in the diagnosis of depression in children and adolescents. Journal Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:631–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penninx BW, Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Vogelzangs N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med. 2013;11:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lannoy S, Dricot L, Benzerouk F, Portefaix C, Barriere S, Quaglino V, et al. Neural responses to the implicit processing of emotional facial expressions in binge drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021;56:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pierce JE, Thomasson M, Voruz P, Selosse G, Péron J. Explicit and implicit emotion processing in the cerebellum: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cerebellum. 2023;22:852–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciapponi C, Li Y, Osorio Becerra DA, Rodarie D, Casellato C, Mapelli L, et al. Variations on the theme: focus on cerebellum and emotional processing. Front Syst Neurosci. 2023;17:1185752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Overwalle F. Social and emotional learning in the cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2024;25:776–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fitzpatrick LE, Crowe SF. Cognitive and emotional deficits in chronic alcoholics: a role for the cerebellum?. Cerebellum. 2013;12:520–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Creupelandt C, Maurage P, DˈHondt F. Visuoperceptive impairments in severe alcohol use disorder: a critical review of behavioral studies. Neuropsychol Rev. 2021;31:361–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bagga D, Sharma A, Kumari A, Kaur P, Bhattacharya D, Garg ML, et al. Decreased white matter integrity in fronto-occipital fasciculus bundles: relation to visual information processing in alcohol-dependent subjects. Alcohol. 2014;48:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Junghöfer M, Bradley MM, Elbert TR, Lang PJ. Fleeting images: a new look at early emotion discrimination. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borgomaneri S, Zanon M, Di Luzio P, Cataneo A, Arcara G, Romei V, et al. Increasing associative plasticity in temporo-occipital back-projections improves visual perception of emotions. Nat Commun. 2023;14:5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Creupelandt C, D’Hondt F, Maurage P. Towards a dynamic exploration of vision, cognition and emotion in alcohol-use disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2019;17:492–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.D’Hondt F, Lepore F, Maurage P. Are visual impairments responsible for emotion decoding deficits in alcohol-dependence?. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen Y, Dhingra I, Le TM, Zhornitsky S, Zhang S, Li CR. Win and loss responses in the monetary incentive delay task mediate the link between depression and problem drinking. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen-Gilbert JE, Nickerson LD, Sneider JT, Oot EN, Seraikas AM, Rohan ML, et al. College binge drinking associated with decreased frontal activation to negative emotional distractors during inhibitory control. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Khalil K, Vakamudi K, Witkiewitz K, Claus ED. Neural correlates of alcohol use disorder severity among nontreatment-seeking heavy drinkers: An examination of the incentive salience and negative emotionality domains of the alcohol and addiction research domain criteria. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:1200–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fede SJ, Grodin EN, Dean SF, Diazgranados N, Momenan R. Resting state connectivity best predicts alcohol use severity in moderate to heavy alcohol users. Neuroimage: Clin. 2019;22:101782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dupuy M, Chanraud S. Imaging the addicted brain: alcohol. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2016;129:1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilcox CE, Pommy JM, Adinoff B. Neural circuitry of impaired emotion regulation in substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:344–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aminoff EM, Kveraga K, Bar M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:379–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang W, Zhornitsky S, Zhang S, Li CR. Noradrenergic correlates of chronic cocaine craving: neuromelanin and functional brain imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:851–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gilman JM, Hommer DW. Modulation of brain response to emotional images by alcohol cues in alcohol-dependent patients. Addict Biol. 2008;13:423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen Y, Li CR. Appetitive and aversive cue reactivities differentiate subtypes of alcohol drinkers. Addiction Neurosci. 2023;7:100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Le TM, Zhornitsky S, Zhang S, Li CR. Pain and reward circuits antagonistically modulate alcohol expectancy to regulate drinking. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhornitsky S, Zhang S, Ide JS, Chao HH, Wang W, Le TM, et al. Alcohol expectancy and cerebral responses to cue-elicited craving in adult nondependent drinkers. Biological Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2019;4:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Filippi I, Hoertel N, Artiges E, Airagnes G, Guerin-Langlois C, Seigneurie AS, et al. Family history of alcohol use disorder is associated with brain structural and functional changes in healthy first-degree relatives. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;62:107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benegal V, Antony G, Venkatasubramanian G, Jayakumar PN. Gray matter volume abnormalities and externalizing symptoms in subjects at high risk for alcohol dependence. Addict Biol. 2007;12:122–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmid F, Henry A, Benzerouk F, Barriere S, Portefaix C, Gondrexon J, et al. Neural activations during cognitive and affective theory of mind processing in healthy adults with a family history of alcohol use disorder. Psychol Med. 2024;54:1034–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wetherill RR, Bava S, Thompson WK, Boucquey V, Pulido C, Yang TT, et al. Frontoparietal connectivity in substance-naive youth with and without a family history of alcoholism. Brain Res. 2012;1432:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT, Yau WY, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA. Affective circuitry and risk for alcoholism in late adolescence: differences in frontostriatal responses between vulnerable and resilient children of alcoholic parents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:414–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aydogan G, Daviet R, Karlsson Linnér R, Hare TA, Kable JW, Kranzler HR, et al. Genetic underpinnings of risky behaviour relate to altered neuroanatomy. Nature Hum Behav. 2021;5:787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hatoum AS, Johnson EC, Baranger DAA, Paul SE, Agrawal A, Bogdan R. Polygenic risk scores for alcohol involvement relate to brain structure in substance-naive children: results from the ABCD study. Genes Brain Behav. 2021;20:e12756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hardee JE, Cope LM, Munier EC, Welsh RC, Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM. Sex differences in the development of emotion circuitry in adolescents at risk for substance abuse: a longitudinal fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017;12:965–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Radoman M, Fogelman N, Lacadie C, Seo D, Sinha R. Neural correlates of stress and alcohol cue-induced alcohol craving and of future heavy drinking: evidence of sex differences. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181:412–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oscar-Berman M, Ruiz SM, Marinkovic K, Valmas MM, Harris GJ, Sawyer KS. Brain responsivity to emotional faces differs in men and women with and without a history of alcohol use disorder. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0248831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seo D, Jia Z, Lacadie CM, Tsou KA, Bergquist K, Sinha R. Sex differences in neural responses to stress and alcohol context cues. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:1998–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meyers JL, Chorlian DB, Johnson EC, Pandey AK, Kamarajan C, Salvatore JE, et al. Association of polygenic liability for alcohol dependence and EEG connectivity in adolescence and young adulthood. Brain Sci. 2019;9:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Villafuerte S, Heitzeg MM, Foley S, Yau WY, Majczenko K, Zubieta JK, et al. Impulsiveness and insula activation during reward anticipation are associated with genetic variants in GABRA2 in a family sample enriched for alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:511–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kinreich S, Meyers JL, Maron-Katz A, Kamarajan C, Pandey AK, Chorlian DB, et al. Predicting risk for alcohol use disorder using longitudinal data with multimodal biomarkers and family history: a machine learning study. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:1133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: relation to a default mode of brain function. Proceedings Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:4259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim AS. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Satpute AB, Lindquist KA. The default mode network’s role in discrete emotion. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23:851–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suk J-W, Hwang S, Cheong C. Functional and structural alteration of default mode, executive control, and salience networks in alcohol use disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:742228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chanraud S, Pitel A-L, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Disruption of functional connectivity of the default-mode network in alcoholism. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Le TM, Malone T, Li CR. Positive alcohol expectancy and resting-state functional connectivity of the insula in problem drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Viswanath H, Velasquez KM, Savjani R, Molfese DL, Curtis K, Molfese PJ, et al. Interhemispheric insular and inferior frontal connectivity are associated with substance abuse in a psychiatric population. Neuropharmacology. 2015;92:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kinreich S, McCutcheon VV, Aliev F, Meyers JL, Kamarajan C, Pandey AK, et al. Predicting alcohol use disorder remission: a longitudinal multimodal multi-featured machine learning approach. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peltier MR, Verplaetse TL, Mineur YS, Petrakis IL, Cosgrove KP, Picciotto MR, et al. Sex differences in stress-related alcohol use. Neurobiol Stress. 2019;10:100149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guinle MIB, Sinha R. The role of stress, trauma, and negative affect in alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorder in women. Alcohol Res. 2020;40:05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Deng WQ, Belisario K, Gray JC, Levitt EE, MacKillop J. A high-resolution PheWAS approach to alcohol-related polygenic risk scores reveals mechanistic influences of alcohol reinforcing value and drinking motives. Alcohol Alcohol. 2024;59:agad093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou H, Kember RL, Deak JD, Xu H, Toikumo S, Yuan K, et al. Multi-ancestry study of the genetics of problematic alcohol use in over 1 million individuals. Nat Med. 2023;29:3184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chaplin TM, Poon JA, Thompson JC, Hansen A, Dziura SL, Turpyn CC, et al. Sex-differentiated associations among negative parenting, emotion-related brain function, and adolescent substance use and psychopathology symptoms. Soc Dev. 2019;28:637–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kendler KS, Edwards AC, Gardner CO. Sex differences in the pathways to symptoms of alcohol use disorder: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:998–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Besson M, Forget B. Cognitive dysfunction, affective states, and vulnerability to nicotine addiction: a multifactorial perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We have obtained permission from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) to use the Open and Restricted Access data for the current study. Data were provided by the WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.