Abstract

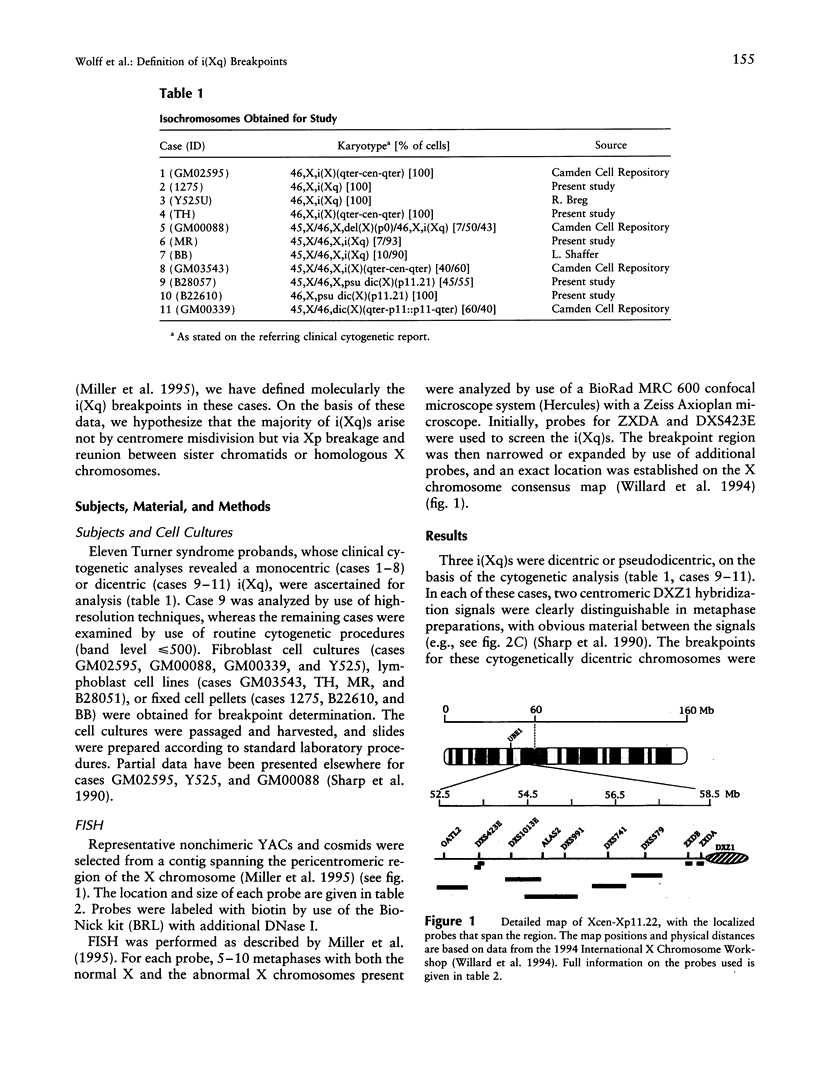

To test the centromere misdivision model of isochromosome formation, we have defined the breakpoints of cytogenetically monocentric and dicentric Xq isochromosomes (i(Xq)) from Turner syndrome probands, using FISH with cosmids and YACs derived from a contig spanning proximal Xp. Seven different pericentromeric breakpoints were identified, with 10 of 11 of the i(Xq)s containing varying amounts of material from Xp. Only one of the eight cytogenetically monocentric i(Xq)s demonstrated a single alpha-satellite (DXZ1) signal, consistent with classical models involving centromere misdivision. The remaining seven were inconsistent with such a model and had breakpoints that spanned proximal Xp11.21: one was between DXZ1 and the most proximal marker, ZXDA; one occurred between the duplicated genes, ZXDA and ZXDB; two were approximately 2 Mb from DXZ1; two were adjacent to ALAS2 located 3.5 Mb from DXZ1; and the largest had a breakpoint just distal to DXS1013E, indicating the inclusion of 8 Mb of Xp DNA between centromeres. The three cytologically dicentric i(Xq)s had breakpoints distal to DXS423E in Xp11.22 and therefore contained > or = 12 Mb of DNA between centromeres. These data demonstrate that the majority of breakpoints resulting in i(Xq) formation are in band Xp11.2 and not in the centromere itself. Therefore, we hypothesize that the predominant mechanism of i(Xq) formation involves sequences in the proximal short arm that are prone to breakage and reunion events between sister chromatids or homologous X chromosomes.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Callen D. F., Mulley J. C., Baker E. G., Sutherland G. R. Determining the origin of human X isochromosomes by use of DNA sequence polymorphisms and detection of an apparent i(Xq) with Xp sequences. Hum Genet. 1987 Nov;77(3):236–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00284476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Chapelle A., Stenstrand K. Dicentric human X chromosomes. Hereditas. 1974;76(2):259–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1974.tb01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw W. C., Cooke C. A. Proteins of the inner and outer centromere of mitotic chromosomes. Genome. 1989;31(2):541–552. doi: 10.1139/g89-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravholt C. H., Friedrich U., Caprani M., Jørgensen A. L. Breakpoints in Robertsonian translocations are localized to satellite III DNA by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1992 Dec;14(4):924–930. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig G. M., Sharp C. B., Carrel L., Willard H. F. Duplicated zinc finger protein genes on the proximal short arm of the human X chromosome: isolation, characterization and X-inactivation studies. Hum Mol Genet. 1993 Oct;2(10):1611–1618. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaf T., Schmid M. Y isochromosome associated with a mosaic karyotype and inactivation of the centromere. Hum Genet. 1990 Oct;85(5):486–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00194221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J. Y., Choo K. H., Shaffer L. G. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of 17 rob(13q14q) Robertsonian translocations by FISH, narrowing the region containing the breakpoints. Am J Hum Genet. 1994 Nov;55(5):960–967. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison M., Hassold T., Kobryn C., Jacobs P. A. Molecular studies of the parental origin and nature of human X isochromosomes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1988;47(4):217–222. doi: 10.1159/000132553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held K. R., Kerber S., Kaminsky E., Singh S., Goetz P., Seemanova E., Goedde H. W. Mosaicism in 45,X Turner syndrome: does survival in early pregnancy depend on the presence of two sex chromosomes? Hum Genet. 1992 Jan;88(3):288–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00197261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook E. B., Warburton D. The distribution of chromosomal genotypes associated with Turner's syndrome: livebirth prevalence rates and evidence for diminished fetal mortality and severity in genotypes associated with structural X abnormalities or mosaicism. Hum Genet. 1983;64(1):24–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00289473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L. Y., Paciuc S., David K., Cristian S., Moloshok R., Hirschhorn K. Number of C-bands of human isochromosome Xqi and relation to 45,X mosaicism. J Med Genet. 1978 Jun;15(3):222–226. doi: 10.1136/jmg.15.3.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorda-Sanchez I., Binkert F., Maechler M., Schinzel A. A molecular study of X isochromosomes: parental origin, centromeric structure, and mechanisms of formation. Am J Hum Genet. 1991 Nov;49(5):1034–1040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtani M. M., Willard H. F. Pulsed-field gel analysis of alpha-satellite DNA at the human X chromosome centromere: high-frequency polymorphisms and array size estimate. Genomics. 1990 Aug;7(4):607–613. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90206-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. P., Gustashaw K., Wolff D. J., Rider S. H., Monaco A. P., Eble B., Schlessinger D., Gorski J. L., van Ommen G. J., Weissenbach J. Three genes that escape X chromosome inactivation are clustered within a 6 Mb YAC contig and STS map in Xp11.21-p11.22. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Apr;4(4):731–739. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockey C. H., Wennström J., De la Chapelle A. Isochromosome-X in man. II. Hereditas. 1966;54(3):277–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1966.tb02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. L., Earnshaw W. C., Choo K. H., Shaffer L. G. Further evidence that CENP-C is a necessary component of active centromeres: studies of a dic(X; 15) with simultaneous immunofluorescence and FISH. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Feb;4(2):289–294. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C. G., Reichmann A. Chromosomal and clinical findings in 110 females with Turner syndrome. Hum Genet. 1976 Dec 29;35(1):35–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00295617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M. C., Prouty L. A., Stevenson R. E., Howard-Peebles P. N., Page D. C., Schwartz C. E. The parental origin and mechanism of formation of three dicentric X chromosomes. Hum Genet. 1988 Sep;80(1):81–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00451462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest J. H., Blackston R. D., Au K. S., Ray S. L. Differences in human X isochromosomes. J Med Genet. 1975 Dec;12(4):378–389. doi: 10.1136/jmg.12.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranke M. B., Pflüger H., Rosendahl W., Stubbe P., Enders H., Bierich J. R., Majewski F. Turner syndrome: spontaneous growth in 150 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 1983 Dec;141(2):81–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00496795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEARS E. R. Misdivision of univalents in common wheat. Chromosoma. 1952;4(6):535–550. doi: 10.1007/BF00325789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Palmer C. G., Weaver D. D., Priest J. Dicentric chromosome 13 and centromere inactivation. Hum Genet. 1983;63(4):332–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00274757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer L. G., Jackson-Cook C. K., Meyer J. M., Brown J. A., Spence J. E. A molecular genetic approach to the identification of isochromosomes of chromosome 21. Hum Genet. 1991 Feb;86(4):375–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00201838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C. B., Bedford H. M., Willard H. F. Pericentromeric structure of human X "isochromosomes": evidence for molecular heterogeneity. Hum Genet. 1990 Aug;85(3):330–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00206757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B. A., Schwartz S. Identification of centromeric antigens in dicentric Robertsonian translocations: CENP-C and CENP-E are necessary components of functional centromeres. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Dec;4(12):2189–2197. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.12.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B. A., Wolff D. J., Schwartz S. Analysis of centromeric activity in Robertsonian translocations: implications for a functional acrocentric hierarchy. Chromosoma. 1994 Dec;103(7):459–467. doi: 10.1007/BF00337384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therman E., Sarto G. E., Patau K. Apparently isodicentric but functionally monocentric X chromosome in man. Am J Hum Genet. 1974 Jan;26(1):83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandall A. A stable dicentric chromosome: both centromeres develop kinetochores and attach to the spindle in monocentric and dicentric configuration. Chromosoma. 1994 Mar;103(1):56–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00364726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard H. F., Cremers F., Mandel J. L., Monaco A. P., Nelson D. L., Schlessinger D. Report and abstracts of the Fifth International Workshop on Human X Chromosome Mapping 1994. Heidelberg, Germany, April 24-27, 1994. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;67(4):295–358. doi: 10.1159/000133870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff D. J., Schwartz S. Characterization of Robertsonian translocations by using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Hum Genet. 1992 Jan;50(1):174–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen T. J., Compton D. A., Wise D., Zinkowski R. P., Brinkley B. R., Earnshaw W. C., Cleveland D. W. CENP-E, a novel human centromere-associated protein required for progression from metaphase to anaphase. EMBO J. 1991 May;10(5):1245–1254. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]