Abstract

Dysregulated RNA splicing is a molecular feature that characterizes almost all tumor types. Cancer-associated splicing alterations arise from both recurrent mutations and altered expression of trans-acting factors governing splicing catalysis and regulation. Cancer-associated splicing dysregulation can promote tumorigenesis via diverse mechanisms, contributing to increased cell proliferation, decreased apoptosis, enhanced migration and metastatic potential, resistance to chemotherapy, and evasion of immune surveillance. Recent studies have identified specific cancer-associated isoforms that play critical roles in cancer cell transformation and growth and demonstrated the therapeutic benefits of correcting or otherwise antagonizing such cancer-associated mRNA isoforms. Clinical-grade small molecules that modulate or inhibit RNA splicing have similarly been developed as promising anti-cancer therapeutics. Here, we review splicing alterations characteristic of cancer cell transcriptomes, dysregulated splicing’s contributions to tumor initiation and progression, and existing and emerging approaches for targeting splicing for cancer therapy. Finally, we discuss the outstanding questions and challenges that must be addressed to translate these findings into the clinic.

Introduction

RNA splicing [G] is a fundamental step in the expression of most human genes. In addition to its essential role in removing introns from pre-mRNA to produce mature mRNAs, splicing also influences other steps in gene expression, including nuclear export, mRNA translation, and mRNA quality control via nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)1. Almost all multi-exon human genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), wherein a single gene generates multiple distinct mature mRNAs to expand the cell’s protein-coding repertoire2. High-throughput sequencing studies have revealed that AS both regulates and is regulated by many biological processes and phenomena, ranging from neural development to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) or T cell activation3,4.

AS plays a similarly important role in many tumors. Most tumors exhibit widespread splicing abnormalities relative to peritumoral healthy tissues, including frequent retention of normally excised introns, inappropriate expression of isoforms normally restricted to other cell types or developmental stages, and splicing errors that disable tumor suppressors or promote oncogene expression5–7. Aberrant splicing in tumors can arise from diverse causes, including altered expression of key splicing regulatory proteins or RNAs, which themselves can function as proto-oncoproteins or tumor suppressors; cis-acting somatic mutations that alter splicing of the genes bearing those lesions; and trans-acting somatic mutations that cause gain- or loss-of-function alterations affecting splicing regulators, driving pervasive splicing changes across the transcriptome6,7. Each of these mechanisms can cause pro-tumorigenic splicing changes, with the last—recurrent mutations in the genes encoding specific splicing factors (SFs) that typically appear as initiating or early events during tumor formation—providing a particularly clear genetic illustration of the fundamental role that splicing dysregulation plays in tumorigenesis. In recent years, a better understanding of individual spliced isoforms that impact cancer cell transformation has led to the development of novel approaches to target these individual events8. Molecular inhibitors of oncogenic SFs or splicing machinery components are currently being developed as anti-cancer therapeutics9. RNA splicing dysregulation plays pervasive and causative roles in tumorigenesis, frequently via disruption of the molecular and cellular processes termed ‘Cancer Hallmarks’ as proposed by Weinberg and Hanahan10,11.

In this Review, we outline both the basic biology and cancer relevance of RNA splicing. We discuss splicing regulatory alterations that are implicated in tumor initiation, as well as individual splicing events associated with tumor initiation, progression and drug resistance. We describe how splicing dysregulation could be therapeutically targeted with small molecules and the technical challenges and outstanding questions that need to be addressed to translate our fast-improving understanding of splicing’s critical role in tumorigenesis into the clinic.

Splicing catalysis and regulation

RNA splicing is a highly regulated process performed by the spliceosome - a very large complex consisting of both RNA and protein components - along with additional regulatory SF proteins, that fine-tune its activity. The spliceosome recognizes core regulatory sequences in the pre-mRNA including the 5’ and 3’ splice sites (5’ and 3’ SS) that mark intron-exon boundaries, the branch point [G] site (BPS), and the polypyrimidine tract [G] (Py-tract)12 (Fig. 1a). Two spliceosomal complexes carry out splicing reactions, the U2-type (major spliceosome) or the U12-type (minor spliceosome). They differ mainly in a subset of RNA components used during their respective splicing reactions and in the splice site sequences they recognize12. The major U2-type spliceosome, which preferentially recognizes GT-AG splice sites and is responsible for the removal of ~99% of introns, contains over 300 components – including small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules that interact with ‘Sm’ core proteins and additional proteins to form small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) particles12. The Sm proteins associate with each other to form a ring-shaped complex that binds to U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs. The minor or U12-type spliceosome, which recognizes both AT-AC and GT-AG sites, is involved in the removal of less than 1% of introns and regulates a distinct set of splicing events and utilizes different spliceosomal snRNA and protein components, including ZRSR213. The U12-type spliceosome has distinct 5’SS and BPS sequence contexts that guide recognition of these introns. The U2-specific snRNPs are U1, U2, U4, and U6, while the U12-type snRNPs are U11, U12, U4atac, and U6atac12.

Figure 1. Principles of constitutive and alternative splicing.

(a) Stepwise assembly of spliceosomal complexes on a pre-mRNA molecule and catalysis of the splicing reaction to generate mature spliced mRNA. During the first step of the splicing reaction, the ATP-independent binding of U1 snRNP to the 5’SS initiates the assembly of the E complex, while SF1 and U2AF2 bind, respectively, to the BPS and Py-tract. In the second step, the ATP-dependent interaction of U2 snRNP with the BPS, stabilized by U2AF2–U2AF1 and SF3a–SF3b complexes, leads to A complex formation and SF1 displacement from the BPS. The recruitment of the U4/U6/U5 tri-snRNP complex marks the formation of the catalytically inactive B complex. The active B* complex is formed following major conformational changes, including release of U1 and U4, and the first catalytic step generates the C complex and results in lariat formation. The C complex performs the second catalytic step, which results in joining of the two exons. The spliceosome then disassembles releasing the mRNA and the lariat bound by U2/U5/U6.Spliceosomal core factors that exhibit alterations in human tumors are colored next to each complex. (b) Alternative splicing patterns are classified into cassette alternative exon splicing, alternative 5’ and 3’ splice site usage, mutually exclusive exons, and intron retention. These splicing patterns lead to distinct spliced mRNA isoforms that can be translated into protein isoforms with distinct sequences and functions. (c) Trans-acting regulatory splicing factors act as splicing activator (A) or repressor (R) and promote or inhibit spliceosome assembly by binding enhancers (ESE/ESS) or silencers (ISE/ISS) cis-acting regulatory sequences. 5’/3’ ASS: 5’/3’ alternative splice site; BPS: branch point site; Py-tract: polypyrimidine tract; snRNP: small nuclear ribonucleoprotein.

The detailed compositions and structures of the spliceosomal complexes have been reviewed extensively12. Several spliceosomal components are altered in human tumors, including via recurrent hotspot mutations in components of the ‘Early’ or E complex and pre-spliceosome A complex (Fig. 1a), and will be discussed further below.

Except for the dinucleotides adjacent to the 5’ and 3’ SS, the core regulatory sequences recognized by the spliceosome are rather degenerate in humans and allow for a huge diversity in their sequences14. This provides an additional layer of regulation that depends on both cis-acting regulatory sequences and trans-acting SF proteins that can strengthen or weaken the spliceosome’s recognition of the splice sites14. Together, these cis-acting sequences and trans-acting SFs regulate AS, allowing a single gene to encode multiple different RNA isoforms that can be translated into different, and frequently functionally distinct, protein isoforms (Fig. 1b). Alternatively spliced isoforms can differ in their coding potential, stability, localization, translation efficiency, and other molecular features. For example, alternative exons are enriched in gene regions that encode protein-protein interaction surfaces15. It is currently estimated that each human protein-coding gene encodes an average of 7.4 RNA isoforms; however, much more extreme examples of AS have been described16.

Regulatory, trans-acting SFs that modulate AS are a class of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that recognize and bind cis-regulatory elements on the pre-mRNA, namely exonic or intronic splicing enhancer (ESE or ISE) or silencer sequences (ESS or ISS), and promote or repress inclusion of that exon into mature mRNA, respectively (Fig. 1c). The serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) are two well-known SF families that regulate AS in a concentration-dependent manner by binding regulatory elements in the pre-mRNA17,18. SR proteins contain an RNA recognition motif (RRM) domain that binds RNA and an arginine/serine-rich (RS) domain that mediates protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions. hnRNPs typically contain one or multiple RRMs, along with a glycine-rich and/or arginine/glycine-rich region, and/or K Homology (KH)-domain [G] 18. hnRNPs play diverse roles in AS, mRNA transport, and translation and often function as antagonists to SR protein-regulated AS events18. The distinct RNA-binding motifs of SR proteins and hnRNPs suggest that these SFs can work antagonistically or cooperatively, and the intricate interplay of these regulatory SFs is only beginning to be unraveled.

Splicing alterations in tumor initiation

Mutations or expression changes affecting components of the splicing machinery or SFs can play critical roles in cancer initiation and progression (Fig. 2). By inducing splicing changes affecting many downstream genes, these alterations have the potential to disrupt a network of gene products and cancer pathways. Several key examples are highlighted in the following sections.

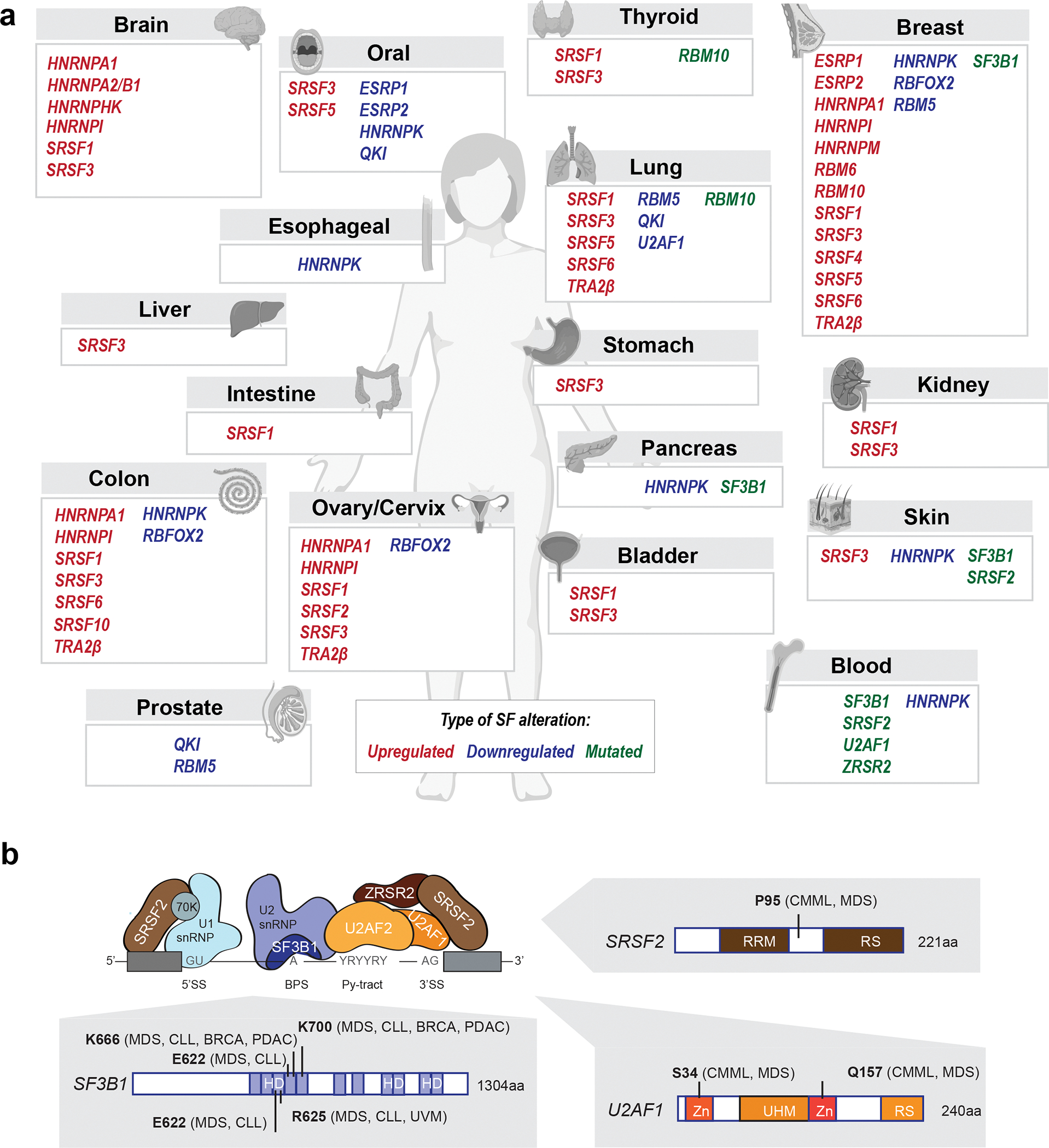

Figure 2. Recurrent splicing factor alterations in cancer.

(a) Examples of SFs frequently upregulated, downregulated, or mutated in human primary tumors shown per tumor type. (b) Recurrent hotspot mutations in components from the spliceosomal A complex detected in human malignancies (BRCA-breast cancer, CLL-chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CMML-chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, MDS-myelodysplastic syndromes, PDAC-pancreatic adenocarcinoma, UVM-uveal melanoma). Positions of recurrent mutations are indicated along with the protein structures and domains (Zn- zinc finger domain, UHM-U2AF homology motif domain, RS-arginine/serine-rich domain, RRM-RNA-recognition motif, HD-heat domain). ZRSR2 mutations primarily affect U12-type introns, but as ZRSR2 has been biochemically implicated in U2-type splicing as well, it is illustrated in association with a U2-type intron above264.

Recurrent mutations in splicing factors

Recurrent somatic mutations in SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 occur frequently in hematological malignancies, including in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)19,20 (Fig. 2a,b). These mutations are frequently termed “spliceosomal mutations”. SF3B1 and U2AF1 are also recurrently mutated in diverse solid tumor types7,21–23. Mutations in SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 almost always occur as heterozygous missense point mutations affecting specific residues in both haematological malignancies and solid tumors, while mutations in the X-linked gene ZRSR2 frequently disrupt its open reading frame and preferentially occur in males. Detailed functional studies have revealed that recurrent SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 mutations cause gain or alteration of function, while ZRSR2 mutations cause loss of function, consistent with the spectra of mutations observed in patients. Spliceosomal mutations are almost always mutually exclusive as they elicit redundant and/or synthetically lethal effects due to their cumulative impact on AS and hematopoiesis24, although there are rare exceptions to this rule25.

SF3B1 is the most frequently mutated spliceosomal component in cancer, with recurrent somatic mutations detected in ~30% of all patients with MDS, including 83% of cases of MDS-subtype refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS) and 76% of cases of MDS-subtype refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ringed sideroblasts (RCMD-RS)19,26. SF3B1 mutations are also detected in other cancers, including 15% of CLL, 3% of pancreatic cancer, 1.8% of breast adenocarcinomas, 1% of cutaneous melanomas, and 20% of uveal melanomas21,22 (Fig. 2a). SF3B1 is a core component of the U2 snRNP that is involved in BPS recognition and spliceosomal complex A assembly (Fig. 1). SF3B1 mutations near-universally occur as heterozygous, missense mutations that affect multiple hotspot residues within the C-terminal HEAT domains (Fig. 2b). These mutations induce altered BPS recognition with consequent changes in 3’SS recognition, resulting in widespread splicing alterations including cryptic 3′SS usage, differential cassette exon inclusion, and reduced intron retention27,28.The prognostic implications of an SF3B1 mutation depend upon the specific mutation and indication. For example, SF3B1K700E is associated with comparatively good prognosis in MDS-RS19,20 , while SF3B1K666N is associated with disease progression29. In CLL, SF3B1G742D correlates with poor prognosis26. Although how mutant SF3B1 promotes disease phenotypes and tumorigenesis is still under active investigation, numerous cellular pathways have been implicated. For example, SF3B1 mutations cause aberrant inclusion of a poison exon (an exon that contains an in-frame premature termination codon) in BRD9 across tumor types to promote cell transformation30; induce MAP3K7 mis-splicing to promote hyperactive nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling and disrupt erythropoiesis24,31, and disrupt splicing of genes involved in heme biosynthesis to cause ring sideroblast formation32.

Recurrent mutations affecting the SR protein SRSF2 have been observed in 10% of all patients with MDS and related disorders, including in 31–47% of CMML and 11% of AML20,33, and less commonly in solid tumors34 (Fig. 2a). SRSF2 mutations are linked with poor clinical outcomes in MDS and increased progression to AML20. Required for both constitutive and alternative splicing, SRSF2 mediates exon inclusion and recognition of the 5’ and 3’SS by interacting with U1 and U2 snRNPs (Fig. 1). Heterozygous mutations immediately adjacent to SRSF2’s RRM domain, which predominantly occur as missense mutations and universally affect the P95 residue (Fig. 2b), alter its RNA-binding preference. Mutant SRSF2 favors recognition of C-rich sequences (CCNG motif) and has reduced affinity for G-rich sequences (GGNG motif), whereas wild-type SRSF2 recognizes both35,36. This alters the efficiency of SRSF2-mediated exon inclusion and results in mis-splicing. For example, mutant SRSF2’s altered binding preference results in downregulation of EZH2, a histone methyltransferase implicated in MDS pathogenesis, due to increased inclusion of a poison exon35. Notably, EZH2 loss-of-function mutations in CMML are mutually exclusive with SRSF2 mutations. SRSF2 mutations frequently co-occur with specific additional somatic mutations, such as isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) mutations, which functionally collaborate with SRSF2 mutations to promote leukemia, in part via increased intron retention in INTS3 that arises from direct effects of mutant SRSF2 as well as IDH233.

U2AF1 is mutated in 5%–15% of MDS, 5%–17% of CMML, and 3% of lung adenocarcinomas20,23,37,38 (Fig. 2a). The U2AF1–U2AF2 heterodimer recognizes the 3’ SS (U2AF1 binds to the AG dinucleotide and U2AF2 to the polypyrimidine tract) and is critical for U2 snRNP binding (Fig. 1). U2AF1 is subject to recurrent mutations affecting two hotspots, S34 and R156/Q157, within U2AF1’s two zinc finger domains (Fig. 2b). Mutations at the two hotspots cause different alterations in RNA binding affinity and 3’ SS recognition to induce largely distinct splicing patterns38,39. The means by which U2AF1 mutations cause disease are not fully understood, with dysregulated pathways including DNA damage response, RNA localization and transport, cell cycle, epigenetic regulation, innate immunity, stress granule formation, and pre-mRNA splicing40,41.

ZRSR2, an X-linked gene, is mutated in 1–11% MDS without ring sideroblasts, 0.8%–8% of CMML, and at lower rates amongst other hematological cancers (Fig. 2a), with most mutations occurring in male patients20,42,43. In contrast to the hotspot alterations described above, ZRSR2 mutations are distributed across the gene (Fig. 2b), preferentially disrupt the open reading frame or key functional residues to cause loss of function, and can co-occur with SF3B1, SRSF2 or U2AF1 mutations20. ZRSR2 heterodimerizes with ZRSR1 and is reportedly involved in recognition of 3’ SS for both U2-and U12-type introns (Fig. 1). ZRSR2 loss results in improper retention of U12-type introns, with few direct effects on U2-type introns44, and promotes clonal advantage in part by causing intron retention in LZTR1, which encodes a regulator of RAS-related GTPases45,46.

Mouse models have provided insight into the initiating roles of recurrent spliceosomal mutations for myeloid malignancies by specifically inducing these lesions in the hematopoietic compartment. Sf3b1K700E/+ knock-in mice exhibit macrocytic anemia, erythroid dysplasia, and long-term hematopoietic stem cell expansion47; Srsf2P95H/+ knock-in mice exhibit impaired hematopoiesis, myeloid and erythroid dysplasia, and hematopoietic stem cell expansion35; U2af1S34F-expressing transgenic mice exhibit altered hematopoiesis48, while U2af1S34F/+ knock-in mice exhibit multilineage cytopenia, macrocytic anemia, and low-grade dysplasias49; finally, Zrsf2 knock-out mice exhibit modest dysplasia and increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal45. One important factor to keep in mind when interpreting results from such mouse models is the imperfect conservation of AS between human and mouse. The particularly high conservation of U12-type versus U2-type introns may explain why Zrsr2 loss leads to a competitive advantage in mouse models, as expected given its enrichment in human disease, whereas mouse models of other spliceosomal mutations do not45.

Genetic evidence similarly indicates that spliceosomal mutations are commonly initiating events in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. Clonality studies of MDS with SF3B1 mutations indicate that these lesions are initiating events that occur in human hematopoietic stem cells and persist in their myeloid progeny50. A recent longitudinal study revealed differences in clonal expansion driven by distinct somatic mutations during aging of the human hematopoietic system and clonal hematopoiesis. Spliceosomal mutations drove expansion later in life, exhibited some of the fastest expansion dynamics, and were strongly associated with transformation to overt malignancy, whereas clones with mutations in epigenetic regulators preferentially expanded early in life and displayed slower growth with old age51. Spliceosomal mutations are frequently expressed at allelic ratios that indicate presence in the dominant clone in many solid tumors, suggesting that they may be early or even initiating events in those malignancies as well. However, further genetic studies in primary patient samples and functional studies in animal models are necessary to reach firm conclusions about the timing of their acquisition.

Genes encoding other spliceosomal components are also mutated in both hematological and solid malignancies (Fig. 2). For example, RBM10 is recurrently mutated in lung, thyroid, and other cancers, resulting in disrupted splicing and pro-tumorigenic effects52,53. SF3A1, PRPF8, SF1, HNRNPK, U2AF2, SRSF6, SRSF1, SRSF7, TRA2B, and SRRM2 mutations have also been reported, although at relatively low rates54. A recent study suggested that >100 genes encoding spliceosomal components contain putative driver mutations across multiple cancer types55. The functional roles of such low-frequency SF mutations in cancer are unclear, although they could potentially be important given the pleiotropic role of splicing in gene expression.

Finally, mutations affecting proteins that are not canonically involved in splicing regulation can have potent effects on splicing. For example, mutations in IDH2 alter AS as discussed above33, while hotspot missense mutations in TP53 are associated with dysregulated AS in pancreatic cancer56.

Splicing factor expression alterations

SF-levels and activity are tightly controlled epigenetically, transcriptionally, post-transcriptionally via AS coupled with NMD, translationally, and post-translationally, including via phosphorylation by specific kinases17,18. Changes to any of these regulatory pathways can lead to altered SF-expression and consequent altered AS of the SFs downstream targets. While recurrent SF mutations are common in hematological malignancies, altered SF-levels and copy number changes are particularly prominent in solid tumors6 (Fig. 2a). SFs regulate AS of downstream mRNA targets in a concentration-dependent manner; therefore, changes in SF-levels alone can induce AS deregulation in tumors17,18. Causal links have been identified between SF misregulation and multiple cancer types. Of note, several SFs that are upregulated in breast tumors exhibit oncogenic functions and are sufficient to promote tumor initiation in breast cancer models57–60. SFs can also serve as tumor suppressors, and therefore SF-downregulation can contribute to tumor development61.

An archetypal example of pro-tumorigenic altered SF-expression is the upregulation of the SR protein SRSF1 in breast, lung, colon and bladder tumors57,60,62.This can arise in part from amplification of Chr.17q23 but is also observed in tumors with amplifications of the gene encoding the transcription factor MYC57,60,63 (Fig. 2a). SRSF1 overexpression enhances AS of isoforms associated with decreased cell death (e.g., BIN1, BIM (also known as BCL2L11), MCL1, CASC4), increased cell proliferation (e.g.RON, MKNK2, S6K1, CASC4, PRRC2C), and resistance to DNA damage (e.g.PTPMT1 and DBF4B), resulting in cell transformation in vivo and in vitro57,58,62–64. SRSF1 can act synergistically with MYC, often resulting in higher tumor grade and shorter survival in breast and lung cancer patients, in part by potentiating the activation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), a translational regulator of cell growth signaling pathways57,63. Further, SRSF1 can activate mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) growth signaling and promote translation initiation in part via interactions with the phosphatase PP2A and mTOR and by enhancing phosphorylation of eIF4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1)65,66.

Another SR protein family member, SRSF3, is overexpressed in lung, breast, ovarian, stomach, bladder, colon, bone, liver, brain, and oral tumors, in part due to copy number6 (Fig. 2a). Decreased expression of SRSF3 is also observed, for example in hepatocellular carcinoma67, suggesting a complex role in tumorigenesis. Targets of SRSF3 play roles in cellular metabolism, growth, cytoskeletal organization, and AS67–69. For example, overexpression of SRSF3 regulates the switch between the two isoforms of pyruvate kinase (PKM), a key metabolic enzyme underlying the Warburg effect on cancer cells69, promoting splicing of the PKM2 isoform and decreasing PKM169. SRSF3 also regulates splicing of HIPK2, a serine/threonine-protein kinase involved in transcription regulation and apoptosis. SRSF3 knockdown promotes HIPK2 exon 8 skipping, leading to expression of an isoform associated with cell death70. SRSF3 also controls AS of target genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, and its conditional knockout in mouse hepatocytes causes fibrosis and the development of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma with aging67. Finally, high SRSF3 levels in tumors and cell lines are associated with the splicing of isoforms 1 and 2 of ILF371, a double-stranded RNA-binding protein implicated in cell proliferation regulation71.

Additional SFs that are frequently upregulated in cancers include other members of the SR protein family, e.g., SRSF4, SRSF6, or SR-like TRA2β; members of the hnRNP protein family, e.g., hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2/B1, hnRNPM, or PTB (also known as hnRNPI); and other SFs, e.g., ESPR1 and 2 and RBM5, 6 and 1072–79 (Fig. 2a).

Conversely, several SFs are downregulated in human tumors, including hnRNPK, ESRP1, ESRP2, RBFOX2, RBM5, or QKI (Fig. 2a). Decreased levels of QKI, a KH domain-containing RNA-binding protein, are detected in several tumor types, including lung, oral, and prostate cancers, and are associated with poor prognosis80,81. QKI regulates AS of NUMB, which encodes a membrane-associated inhibitor of Notch, leading to an isoform that decreases cell proliferation and prevents Notch signaling81. QKI also regulates the expression of SOX2 (which encodes a transcription factor) by binding a cis-element in its 3′ UTR80. In addition, gene fusions of QKI with MYB have been described in angiocentric gliomas, a subtype of pediatric low-grade brain tumors, and shown to promote transformation in vitro and in vivo82.

In addition to SRSF3 discussed above, other SFs (e.g., ESRPs, other SR proteins, and RBM proteins) can similarly be either upregulated or downregulated depending on the tumor type, suggesting context-dependent functions as both oncoproteins and tumor suppressors and complex roles in regulating tissue-specific splicing. For example, ESRP1 exhibits tumor-suppressive functions, and its downregulation during EMT regulates a specific set of EMT-associated splicing switches and promotes a more aggressive EMT-phenotype in vitro 83–85. In contrast, it also exhibits oncogenic activity; high levels of ESRP1 been associated with poor prognosis in prostate72 and estrogen receptor positive breast tumors73 and lead to increased lung metastasis in animal models of breast cancer86. Adding to the complexity, in oral tumors, ESRP1—which is expressed at low levels in normal epithelium—becomes upregulated in pre-cancerous lesions, carcinoma in situ, and advanced lesions but then is downregulated in invasive tumor fronts76. Another example of an SF with dual functions is RBM5, which is often considered to be a tumor suppressor77,87,88 and is downregulated in lung and prostate cancers87,89, but is upregulated in primary breast tumors78.

Aberrantly spliced RNA isoforms

Tumors often exhibit a more complex splicing repertoire than do normal tissues (Box 1), and tumorgenicity may be associated with cancer-specific AS events that arise during the transformation process. In some cases, cis-acting mutations can disrupt splicing to promote tumorigenesis. Such cis-acting mutations frequently cause MET exon 14 skipping in lung cancer90, and other cis-acting mutations can similarly disrupt gene expression by inducing retention of specific introns91.

BOX 1 |. Common splicing patterns detected in tumors.

Tumor-associated alterations in splicing patterns can lead to a wide variety of functional consequences that impact cancer hallmarks. While every alternative splicing (AS) event will be unique, a few broader categories have emerged. First, inclusion or skipping of in-frame sequences as a consequence of cassette exon splicing or alternative splice site selection can lead to the addition or deletion of amino acid-encoding nucleotides, impacting protein structure, function, and/or localization (see panel a). On the other hand, inclusion or skipping of out-of-frame sequences will introduce premature termination codons (PTCs), which will typically trigger nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and prevent production of a corresponding protein isoform (panel b). Those PTC-containing transcripts in tumors can arise from intron retention, due to both transcriptome-wide intron retention273 and focal retention due to cis-acting mutations91, as well as other AS events.

A special subclass of out-of-frame AS events that trigger NMD are ‘poison exons’, which correspond to cassette exons that when included introduce a PTC in the transcript (panel c). Poison exons are particularly common in genes encoding splicing factors (SFs) and frequently endogenously regulate SF protein levels215,216. Their altered splicing can cause overexpression of oncogenic SFs and downregulation of tumor-suppressive SFs across tumor types. Interestingly, many of the AS events detected in tumors correspond to isoforms initially expressed during embryonic development and then switched when adult cells differentiate30,35. This reversion to embryonic patterns has been postulated to enable cancer cell proliferation and phenotypic plasticity.

Cancer-specific AS frequently arises independently of the presence of such cis-acting mutations or recurrent mutations affecting SFs5. Such AS switches impact thousands of genes and are often specific to a given tumor type5, or even subtype, likely because baseline splicing profiles differ between normal tissues. Nonetheless, numerous AS isoforms are frequently dysregulated across multiple tumor types, suggesting shared splicing regulatory networks across tissue types.

These dysregulated isoforms often impact the so-called ‘Hallmarks of Cancer,’ a series of biological capabilities acquired during the development of human tumors that are frequently used as an organizing principle for rationalizing cancer complexity. Cancer-associated AS isoforms can provide a proliferative advantage, improve cell migration and metastasis, enable escape from cell death, rewire cell metabolism or cell signaling, promote an abetting microenvironment, alter immune response, or enable drug resistance (Fig. 3). Such cancer-associated AS switches can arise from changes in SF levels or activity, cis-acting mutations affecting specific splice sites or exons, or other means. Functional studies in model systems have demonstrated that alterations in a single isoform can impact tumor growth but are often not sufficient to fully recapitulate SF-mediated transformation57–59,92,93, suggesting that the combination of multiple AS isoform switches is likely required to promote the different steps of tumorigenesis5.

Figure 3. Splicing hallmarks of cancer.

Examples of spliced isoforms implicated in the regulation of critical cellular processes defined as the Cancer Hallmarks by Weinberg and Hanahan10,11. Note that the cancer hallmark ‘Polymorphic microbiomes’ is not included here.

Differential splicing in tumors can lead to the expression of isoforms that increase proliferative potential (Fig. 3). For example, splicing of the RPS6KB1 gene encoding the protein S6K1, a substrate of mTOR that controls translation and cell growth, has been associated with sustained cell proliferation and tumor growth. The RPS6KB1–1 isoform produces a full-length protein, while the premature termination codon (PTC)-containing RPS6KB1–2 isoform, created by the inclusion of three cassette exons 6a, 6b, and 6c, generates a shorter isoform that lacks a portion of the kinase domain and differentially activates downstream mTORC1 signaling94. This splicing switch is regulated by SRSF160. RPS6KB1–2 is highly expressed in breast and lung cancer cell lines and primary tumors, and its knockdown decreased cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth, while conversely, knockdown of RPS6KB1–1 induced transformation94–96.

Splicing of the PKM gene can lead to deregulated cell metabolism (Fig. 3). Inclusion of either of the two mutually exclusive exons, exon 9 or exon 10 produces the constitutively active PKM1 or the cancer-associated PKM2 isoform, respectively69,97,98. These isoforms differ by 22 amino acids, and while both perform the same catalytic function, PKM2 can switch between the active and inactive state99. High PKM2 levels in human solid tumors correlate with shorter patient survival, advanced stage, and poor prognosis99. PKM2 splicing is regulated either by repressing inclusion of exon 9 via binding of PTBP1, hnRNPA1, or hnRNPA2, or promoting exon 10 inclusion via binding of SRSF397,98,100.

To survive, cancer cells need to acquire the ability to resist cell death. Multiple genes that control cell death are regulated at the splicing level, giving rise to distinct isoforms that either exhibit anti- or pro-apoptotic functions, including BCL-2 family members, such as BCL2L1, BIM, or MCL1 (Fig. 3). BCL2L1 generates two isoforms, BCL-xL and BCL-xS, which respectively suppress and promote apoptosis101–104. This splicing switch relies on the usage of an alternative 5’ SS in exon 2 and is regulated by SAM68, RBM4, PTBP1, RBM25, SRSF1, hnRNPF, hnRNPH, hnRNPK and SRSF966,105–112.

Genomic instability is one of the hallmarks of tumors and one of the proteins that senses single strand DNA breaks and activates DNA damage response is the serine/threonine checkpoint kinase CHK1 (Fig. 3). Skipping of CHK1 exon 3 produces the shorter isoform CHK1-S that uses an alternative downstream initiation start site compared to the full-length isoform113. The resulting protein lacks the ATP-binding N-terminal domain and represses full-length CHK1. High levels of CHK1-S are detected in ovarian, testicular, and liver cancer tissues113,114.

Nearly all cancer cells up-regulate telomerase to re-elongate or maintain telomeres. Splicing of the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase, TERT, can generate at least 22 distinct isoforms, which differ in their activity; many of these lack telomerase activity and have a dominant negative effect115 (Fig. 3). A splicing switch to favor the full-length TERT, which has telomerase activity, occurs in cancer cells, and is regulated by SFs hnRNPK, hnRNPD, SRSF11, hnRNPH2, hnRNPL, NOVA1 and PTBP1116–120.

An example of tumor suppressor evasion involves the transcription factor KLF6, which regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, and is often inactivated in tumors by mutation or deletions (Fig. 3). AS of KLF6 can produce an oncogenic isoform KLF6-SV1, as opposed to the full-length tumor suppressor isoform. KLF6-SV1 uses an alternative 5’ SS that causes a frame shift and produces a protein with 21 novel amino acids but lacking all three of the zinc finger domains121,122. KLF6 splicing is regulated by SRSF1, TGFβ1, and RAS signaling123,124. Increased KLF6-SV1 levels are detected in prostate, lung, ovarian, brain, breast, pancreatic, and liver tumors, and correlate with poor survival122,123,125. KLF6-SV1 knockdown increases apoptosis and prevents tumor growth, whereas its overexpression promotes cancer cell proliferation, survival, or invasion in vitro and in vivo122,123,125.

Splicing alterations and tumor progression

Many AS isoforms have been linked with increased cell invasion, angiogenesis, and metastatic dissemination (Fig. 3). Several genes encoding proteins that regulate cell adhesion and migration express distinct spliced isoforms during cell invasion or EMT. These include AS of CD44, RAC1, RON (also known as MST1R), or MENA (also known as ENAH) that generate isoforms enabling cell invasion and metastatic dissemination. For example, MENA, a regulator of actin nucleation and polymerization that modulates cell morphology and motility, generates three main isoforms that play different roles in tumor progression. Inclusion of exon INV or 11a produces respectively isoforms MENA-INV or MENA11a which are expressed in breast and lung tumors but not in normal tissues126–130, whereas skipping of exon 6 produces MENAΔv6129. These splicing events are regulated by many SFs, including ESPR1 and ESPR2131. Isoform ratios are altered during tumor progression, with increased MENA-INV and MENAΔv6, and decreased MENA11a associated with tumor grade and metastasis126–130,132,133.

Splicing switches can also impact angiogenesis and promote tumor growth and dissemination to distant organs (Fig. 3). AS of VEGFA, a growth factor that promotes proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, leads to protein isoforms with differential functions in angiogenesis. Inclusion of variable exons 6a, 6b, 7a, or 7b produces pro- angiogenic VEGFAxxx isoforms, whereas inclusion of variable exon 8b, instead of exon 8a, produces anti-angiogenic VEGFAxxxb isoforms134,135. Both isoforms exhibit similar binding affinity to their receptor in vitro; however, VEGFAxxxb is unable to stimulate VEGF signaling and thus inhibits angiogenesis136. Splicing of VEGFAxxxb is promoted by SRSF6, whereas SRSF1 and SRSF5 shift the balance towards VEGFAxxx isoforms137. Expression of anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb often decreases as tumors progress136,138–141, and its overexpression can reduce tumor growth in mice140,142.

Moreover, AS has been linked with changes in the tumor microenvironment through effects on both stromal and immune components (Fig. 3). Several extracellular matrix components undergo AS switches during tumor progression143. These include splicing of fibronectin and its receptor, α5β1 integrin, both of which have been linked to radiation resistance144–146. Inclusion of the fibronectin ED-A exon leads to an isoform expressed during embryonic development and in malignant cells, and which differs in its integrin binding domain compared to the pro-angiogenic fibronectin isoform that includes exon ED-B144–146. Similarly, tumor-specific isoforms of tenascin-C (TNC) or osteopontin (SPP1) have been linked with disease progression147,148. Furthermore, changes in extracellular matrix stiffness and composition can lead to differential splicing58,149, for example, through differential phosphorylation and activation of SFs150.

Finally, AS also impacts multiple regulatory steps in immune cell development and function151 (Fig. 3). For example, AS of CD45 is a key step during activation of T cells, whereas CD44 AS is involved in lymphocyte activation151. AS regulates multiple genes that mediate Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and controls the production of positive regulators of TLR signaling, including IRAK1, CD14, and IKKβ, as well as the negative regulators sTLR4 and RAB7B152–154. Similarly, soluble isoforms of interleukin receptors, such as IL-4R, IL-5R, and IL-6R, are generated by AS in immune cells151. However, it remains unclear how cell compositional changes in the immune repertoire of tumors impact splicing patterns detected in bulk tissue RNA-sequencing.

Splicing alterations and response to therapy

Resistance to targeted therapies

Alterations in AS can lead to resistance to targeted therapy via effects on the target or signal transduction pathway (Fig. 4). Treatment with vemurafenib, a BRAF-V600E inhibitor, selects for resistant cells expressing an AS BRAF isoform that does not encode the RAS-binding domain that normally regulates BRAF dimerization and activation155. Similarly, the BRCA1Δ11q isoform, a variant lacking the majority of exon 11, promotes resistance to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition and cisplatin156. In addition, BRCA1 wild-type colon cancer cells that are resistant to PARP inhibition express BARD1β157, an oncogenic spliced isoform of the BRCA1 interaction partner BARD1 required for BRCA1 tumor suppressor activities. Expression of BARD1β correlated with impaired homologous recombination and its exogenous expression increased resistance to PARP inhibitors. Likewise, splicing of the BH3-only pro-apoptotic protein BIM, which is regulated by SRSF1, has been linked with response and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors57,158. Finally, AS of HER2 (also known as ERBB2), including skipping of exon 16—which encodes Δ16HER2, a constitutively active protein that lacks 16 amino acids in the extracellular domain—decreases sensitivity to the HER2-targeting antibody trastuzumab159,160.

Figure 4. Splicing-driven alterations in drug responses.

Examples of alternatively spliced isoforms associated with altered response or resistance to targeted therapies, including isoforms that confer resistance to therapies targeting HER2 (a) or the androgen receptor (b), as well as to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells (c,d). AR, androgen receptor; Ex, exon; FL, full length.

Drugs that inhibit hormone receptor signaling are often used as frontline treatments for prostate tumors expressing androgen receptor (AR) or breast cancers expressing estrogen receptor alpha (ERα). Patients often develop resistance to these therapies, and splicing alterations can contribute to drug sensitivity (Fig. 4). For example, expression of AR isoforms that activate AR signaling despite lacking the ligand-binding domain where hormones and anti-androgen antagonists act (e.g., AR-V7 and AR-v567es) is associated with anti-androgen resistance and metastasis161–163. Similarly, breast cancers expressing ERα36, an isoform lacking the constitutive activation function (AF-1) domain and part of the hormone-dependent activation function (AF-2) domain, do not respond well to tamoxifen treatment compared to patients whose tumors express other ERα isoforms164.

Resistance to immunotherapy

A breakthrough in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) has been the development of immunotherapeutics directed against CD19, including CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Yet, relapses occur in 50% of patients due to immune rejection and T cell exhaustion or loss of the targeted epitope165. Epitope loss can be driven by AS of CD19, generating spliced isoforms that lack exon 2 and are not recognized by CAR-T cells, leading to resistance166 (Fig. 4). Another example of AS-driven acquired resistance to CAR-T cell therapies is AS of CD22167. Skipping of exons 5 and 6 leads to resistance to CAR-T cells targeting the third immunoglobulin-like domain of CD22, whereas skipping of the start codon-containing exon 2 prevents CD22 protein production, thereby decreasing the levels of protein available for epitope presentation167.

Targeting splicing for cancer therapy

Given splicing’s critical role in tumorigenesis, there is intense interest in targeting AS for cancer therapy. A variety of approaches, ranging from inhibiting key spliceosomal proteins or regulatory SFs to modulating specific AS events, are under preclinical and clinical development. The following discusses these approaches, starting from broad-spectrum splicing modulation to specific isoform-level approaches and ending with a discussion of novel approaches that have shown potential preclinically (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Therapeutic approaches to target splicing in cancer.

Current strategies either target (a) the splicing machinery itself or (b) the aberrantly spliced isoforms expressed in tumor cells. (a) Approaches targeting the spliceosome and splicing factors (SFs) include broad-spectrum inhibition or modulation as well as SF-specific inhibition both directly or through inhibition of upstream regulators of post-translational modifications (e.g., targeting methylation (Me), phosphorylation (P), or ubiquitination (Ub) processes). (b) Modulation of specific isoforms can be achieved using small molecules, splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), DNA- or RNA-targeting Cas with CRISPR-based approaches, or engineered small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs).

Broad-spectrum splicing modulation

Targeting the core spliceosome

One approach for targeting splicing for cancer therapy is to inhibit the spliceosome itself. SF3B1 is a spliceosome component critical for BPS and 3’SS selection (Fig. 1), and limiting its function disrupts splicing at very early stages in spliceosome assembly. Multiple natural products and derivative molecules that target SF3B1 have been identified or developed, including FR901464 and its derivatives (e.g., spliceostatin A, meayamycin, and thailanstatins); sudemycin E; pladienolide B, FD-895, and their derivatives (e.g., E7107, H3B-8800); and herboxidiene168–173 (Fig. 5). Mechanistically, SF3B1 inhibition prevents BPS recognition and leads to widespread disruption of both constitutive splicing and AS, including in transcripts involved with cell proliferation and death174. Interestingly, only a subset of introns and AS events are affected by SF3B1 inhibition, indicating that some splice sites are more sensitive than others to spliceosomal inhibitors47,174. Cancer cells bearing recurrent mutations in spliceosomal genes are particularly sensitive to SF3B1 inhibitors compared to wild-type cells47,175; however, no compounds that selectively target only mutant SF3B1 have been developed. Several SF3B1 inhibitors have been taken into clinical trials. E7107 entered into phase I trials for solid tumors and resulted in dose-related AS changes in patient cells but did not demonstrate broad efficacy and was associated with ocular toxicities that led to study discontinuation176,177. H3B-8800 has also undergone phase I clinical trials as a treatment for myeloid neoplasms. Although no complete or partial responses were observed, a decreased need for blood transfusions was observed in some patients, with minor adverse events178. Given the critical role of the SF3b complex in normal splicing, it is unclear whether there will be a sufficient therapeutic index for compounds that inhibit wild-type SF3B1 function in a clinical setting.

Another broad-spectrum spliceosome inhibitor is isoginkgetin, which prevents recruitment of the U4/U5/U6 tri-snRNP and leads to stalling at the prespliceosomal A complex179. In pre-clinical models, isoginkgetin treatment influences a number of cancer relevant-pathways including cell death180, invasion181, and immune response182.

Targeting alternative splicing factors

The development of inhibitors targeting specific RBPs and SFs has been challenging, in part due to the lack of catalytically active sites that are readily targetable by most classical small molecule inhibitor approaches. One notable exception is the serendipitous discovery that several aryl sulfonamides, which have anti-cancer activity via previously unknown mechanisms of action, act as molecular glues that cause degradation of the RBP RBM39 via recruitment to the CUL4-DCAF15 ubiquitin ligase complex. These compounds (e.g., E7820, indisulam, tasisulam, and chloroquinoxaline sulfonamide) induce highly specific degradation of RBM39 and its paralog RBM23183–185 (Fig. 5). RBM39 is a regulatory SF that works with U2AF65 and SF3B1 in the initial stages of spliceosome assembly and splice site recognition186–188 and additionally coordinates the action of other regulatory SFs, including SR proteins189. RBM39 knockdown broadly impacts AS events, and RBM39-regulated AS events have a 20% overlap with those regulated by U2AF65190,191. Clinical trials of aryl sulfonamides have been undertaken191, including a phase III trial comparing tasisulam to paclitaxel for metastatic melanoma that was halted due to myeloid toxicity and lack of evidence that tasisulam was superior to the standard of care192. However, those trials were conducted prior to the discovery of the mechanism of action of these compounds, and so target engagement and consequent splicing alterations have not yet been measured in clinical trials.

Given that over- and under-expression of specific SFs is common and can promote tumorigenesis, developing means to correct SF expression could be therapeutically valuable. No such general-purpose ways of targeting individual SFs currently exist, but future efforts to develop them could include identification of molecular glues for SFs beyond RBM39; promoting or suppressing inclusion of poison exons within SFs via antisense oligonucleotides or small molecules to suppress or enhance SF protein levels, respectively; and targeting upstream regulators of SF activity or expression that are more readily druggable than are many SFs themselves.

Targeting upstream regulatory proteins

SFs are subject to extensive post-translational modifications that provide opportunities for therapeutic interventions. For example, spliceosomal proteins and SFs are subject to extensive arginine methylation, such that both type I (PRMT1, PRMT3, PRMT4, PRMT6, PRMT8) and type II (PRMT5) protein arginine methyltransferases are critical for regulation of both constitutive and AS through their methylation of Sm proteins and regulatory SFs193,194. PRMT5 itself is a direct target of the MYC oncogene, providing a link between MYC-driven tumors and AS93. Many small molecules that inhibit type I or II PRMTs have been identified (Fig. 5). Both type I and type II PRMT inhibitors exhibit promising preclinical activity, such as anti-tumor activity against lymphoma and leukemias with spliceosomal mutations in cell lines and mouse models195, and several are currently in early clinical trials.

Many SFs, particularly SR proteins, are heavily phosphorylated. These phosphorylation events alter SF activity and localization and are ultimately required for their splicing activity. Inhibition of the kinases that regulate these phosphorylation events may therefore be a viable strategy to diminish the activity of oncogenic SR proteins (Fig. 5). Serine-rich protein kinase-1 (SRPK1) inhibitors lead to decreased phosphorylation of multiple SR proteins and have antiangiogenic effects through SRSF1-mediated AS of VEGF196–198. Another compound, TG003, influences SR protein phosphorylation by inhibiting CDC-like kinase 1 (CLK1)199, and exhibits anti-cancer effects in prostate and gastric cancer models200,201. Other inhibitors targeting CLK1, CLK2, and CLK4 impair the viability of colorectal cancer cells in vitro by impacting the interaction of SRSF10 with these kinases202. Inhibitors of dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinases (DYRKs) can similarly modulate SF phosphorylation and activity. Most of these kinase inhibitors impact the activity of multiple SR proteins, and it remains to be determined whether greater selectivity is required to limit toxicity in patients with cancer202. Phosphorylation of other SFs is important for their activity as well. For example, CDK11 phosphorylates SF3B1, and inhibition of CDK11 via the compound OTS964 impairs splicing catalysis and causes intron retention203.

In sum, multiple approaches that induce broad-spectrum splicing modulation and/or inhibition show preclinical promise and are currently being tested in the clinic. However, as all existing approaches affect splicing in both healthy and malignant cells, careful assessment of potential toxicity and therapeutic indices is critical. Given this current limitation, the future development of compounds that selectively target or otherwise antagonize the neomorphic activities of mutant spliceosomal proteins has the potential to yield substantial therapeutic benefit with favorable side effect profiles.

Targeted splicing correction

Small molecules targeting individual isoforms

As many disease-related SFs are not currently druggable with small molecules, targeting key downstream mis-spliced RNAs instead may offer a promising therapeutic approach. However, only a few compounds that work by targeting a specific RNA transcript have shown clinical utility to date204. Risdiplam is the first FDA-approved small molecule for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy that works by targeting the RNA transcript204,205. Risdiplam promotes exon 7 inclusion by selectively binding a splicing enhancer in exon 7 and the intron downstream of the 5′SS in the SMN2 pre-mRNA206. The past five years have seen an increase in similar efforts to identify small molecules that target specific cancer-relevant RNAs. Small molecule ligands that target RNA can be rationally designed by taking into account the preferred binding sites or RNA structure for each small molecule, which can be identified from sequence information and in vitro studies207,208. Small molecules can be used to induce targeted degradation of RNAs, direct cleavage, or splicing modulation through steric hindrance207,208. However, development of such approaches is much more advanced in genetic diseases than in oncology.

Splicing modulation with oligonucleotides

RNA-based therapeutics offer the potential for extraordinary specificity for virtually any pre-mRNA sequence for the purpose of altering pre-mRNA splicing. Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are short, chemically modified RNA oligos that are designed to bind a reverse complimentary sequence in a target pre-mRNA, thereby preventing its interaction with the splicing machinery (Fig. 5). Splice-switching ASOs can be designed to specifically target: 1) a 5’ or 3’ SS, thus blocking its usage; 2) a splicing enhancer sequence, thus preventing binding of a SF activator and promoting exon skipping; 3) a splicing silencer sequence, thus preventing binding of a SF repressor and promoting exon inclusion; or 4) a cryptic SS that arises due to a mutation, thus restoring the wild-type splice site209. Chemical modifications to the phosphate backbone and/or the ribose ring have generated highly stable ASOs with high substrate specificity, low toxicity, low immunogenicity, and reduced ribonuclease H degradation rate210. Delivery of ASOs to a target tissue remains a substantial challenge to their widespread therapeutic usage, except for delivery to the liver, for which GalNAc conjugation is very effective211,212. Current splice-switching FDA-approved ASOs are delivered directly to their target location or systemically213, but delivery to some tissues, including tumors, remains challenging. Novel approaches to delivery involve packaging formulations that enhance cellular uptake or targeted approaches like aptamer- or antibody-conjugation that direct the ASO to specific tissues or cell types213. A further important challenge to utilizing ASOs in oncology is the importance of delivery to most or all tumor cells for efficacy, at least for approaches that act via cell-intrinsic mechanisms.

Despite the challenges of delivery in vivo, the catalogue of ASOs targeting cancer pathways has grown. In many cases, ASOs correcting cancer-associated AS events have led to promising anti-cancer phenotypes in cell line and animal models (Table 1). For example, the gene encoding BCL-x (BCL2L1) can be alternatively spliced to produce a pro-apoptotic isoform, BCL-xS, or an antiapoptotic isoform, BCL-xL, and an ASO that promotes the formation of BCL-xS induces apoptosis in glioma cell lines214. The bromodomain containing 9 (BRD9) gene encodes a poison exon that leads to degradation of its mRNA when included in SF3B1-mutant tumors. An ASO that forces skipping of this exon results in increased BRD9 protein levels and decreased tumor volume in uveal melanoma mouse models30. A similar approach has been taken to target poison exons in transcripts encoding oncogenic SFs. ASOs that promote inclusion of poison exons in SRSF3215 and TRA2B216 lead to AS changes in their target transcripts and decreased proliferation of cancer cells. Additional targets include regulators of p53 (e.g., MDM2, MDM4, USP5), cell signaling (e.g., ERRB4, IL5R, STAT3, FGFR1, MSTR1), cell death (e.g., BCL2L1, BIM, MCL1), DNA damage (e.g., BRCA2, ATM), and chromatin remodeling and transcription (e.g., BRD9, ERG) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Splicing-modulating antisense oligonucleotides tested in cancer models.

| Target Gene |

Induced Splicing Event |

Tumor Type |

Type of cancer model | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ATM | blocks exon inclusion | LE | Cell line | 248 |

| BCL-X | switches BCL-xL to BCL-xS | BRCA, GBM, LUAD, PRAD | Cell line | 249, 250 |

| BIM | exon 4 inclusion | LE | Cell line | 251 |

| BRCA2 | cryptic exon skipping | BRCA | Cell line | 252 |

| BRD9 | exon 14a skipping | UVM | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

30 |

| ERBB4 | exon 26 skipping | BRCA | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

253 |

| ERG | exon 4 skipping | PRAD | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

254 |

| EZH2 | poison exon skipping | LE | Cell line |

195 |

| FGFR1 | exon α inclusion | GBM | Cell line | 255 |

| GLDC | exon 7 skipping | LUAD | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

256 |

| IL5R | exon 5 skipping | LE | Cell line | 257 |

| MCL1 | exon 2 skipping | SKCM | Cell line | 258 |

| MDM2 | exon 4 skipping | UCEC | Cell line | 259 |

| MDM4 | exon 6 skipping | DLBCL, SKCM | Cell line Patient-derived xenograft mouse model |

260 |

| MKNK2 | 3’ UTR intron retention | GBM | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

92 |

| MSTR1 | exon 11 skipping | BRCA, STAD | Cell line | 261 |

| PKM2 | exon 9 inclusion | GBM | Cell line | 69 |

| SRSF3 | poison exon inclusion | BRCA, OSCC | Cell line | 215 |

| STAT3 | exon 23 skipping | BRCA | Cell line Xenograft mouse model |

262 |

| TRA2B | poison exon inclusion | BRCA | Cell line | 216 |

| USP5 | alternative 5' SS | GBM | Cell line | 263 |

Breast carcinoma (BRCA), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), glioblastoma (GBM), leukemia (LE), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), uveal melanoma (UVM).

Novel strategies targeting alternative RNA splicing

New approaches aimed at targeting either SFs or specific AS events have emerged to widen the repertoire of RNA-targeting tools. One example is decoy oligonucleotides, which attenuate SF activity by competing for their natural binding targets217 (Fig. 5). Decoy oligonucleotides induce transcriptomic changes similar to knockdown of the target SF, and SRSF1 decoys can limit the growth of glioma cells in vivo217. Another approach is the use of engineered U7 snRNAs to correct a specific AS event. This approach alters U7’s specificity for histone mRNA processing and reengineers it to block specific pre-mRNA sequences, effectively acting as an antisense molecule218. Stable expression of these constructs may overcome the limitation of conventional antisense therapeutics, in that they would not require multiple rounds of administration218. So far, this approach has been utilized in models of myotonic dystrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, β-thalassemia, HIV infection, and spinal muscular atrophy218. Additionally, alterations in the sequence recognition of the U1 snRNA can enable specific targeting of exons to promote their inclusion, and has been applied to several RNA targets, including SMN2 (Spinal Muscular Atrophy) and SPINK5 (Netherton Syndrome)219.

The idea of engineering programmable SFs started with the use of RNA-binding domains from Pumilio 1 targeted to specific pre-mRNA sequences220. When designed to target BCL-X, Pumilio 1 engineered SFs promoted the formation of pro-apoptotic BCL-xS and sensitized cancer cells to chemotherapy220. In the CRISPR era, RNA-targeting Cas13 (CasRx) has been adapted to base edit target RNA221 or alter splicing of pre-mRNA222. Building on the Cas13 RNA-targeting capability, CRISPR artificial splicing factors were developed to direct the splicing activity of an individual SF to a target pre-mRNA (Fig. 5) using guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting for example SMN2 in models of spinal muscular atrophy223 or regulatory exons of oncogenic SFs in breast cancer models216. One challenge facing CRISPR-based approaches for therapeutic splicing modulation is that the Cas machinery must be delivered and expressed in addition to the gRNA itself.

Finally, gene editing by CRISPR-based approaches enables targeting specific AS events. By engineering specific mutations, one can strengthen or abolish a specific SS sequence in a target of interest, thereby promoting exon inclusion or skipping. For example, cytidine deaminase single-base editors have been used to program exon skipping by mutating target DNA bases within SS224,225. Alternatively, targeted exon deletions with CRISPR-Cas9 using paired gRNAs can promote exon skipping for desired targets226.

Immunomodulatory approaches

Peptides translated from aberrant, cancer-associated RNA isoforms are promising targets for immunotherapies. These cancer-specific neoantigens—antigenic epitopes that are not produced or presented by major histocompatibility complex I (MHC class I) in healthy cells—can arise from mutations affecting splicing as well as non-mutational use of aberrant splice junctions, intron retention, and other cancer-specific AS227. For example, AS of CD20 in B-cell lymphomas produces a T helper (TH)-cell response that can selectively kill malignant B-cell clones, and vaccination of humanized mice with the corresponding peptide from CD20 spliced isoforms can produce a robust T cell response228. Large-scale analysis of sequencing and proteomic data has uncovered cancer-associated AS-derived epitopes that are predicted to bind MHC class I in over half of tumor samples analyzed5. Additionally, studies using long-read RNA sequencing (LR-seq) identified aberrant, tumor-specific isoforms, a subset of which encoded putative AS-derived neoantigens that were immunogenic in mice expressing a human MHC allele229.

In this context, it is interesting to note that tumor mutational burden, a common measure of neoantigenic potential, does not always correlate with an individual patient’s response to immune checkpoint inhibitors230. Discovery of AS-derived neoantigens may complement genomic analysis to determine which patients will respond to immune checkpoint therapy231 and additionally represent a rich source of potential targets for immunotherapy, particularly if tumor-specific targets that are shared across many patients can be identified227,231–233. Splicing modulation via multiple compounds that inhibit the SF3b complex triggers an antiviral immune response and apoptosis in transplantable syngeneic mouse models of breast cancer234, consistent with an important role for aberrant splicing in influencing tumor-immune interactions.

Another promising approach is synergistic treatment with splicing-modulating drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors235. Therapeutic modulation of AS in syngeneic mouse tumor models by RBM39 degradation or PRMT inhibition induced mis-splicing-derived neoantigen presentation on tumor cells that stimulated robust anti-tumor immune responses and enhanced responses to checkpoint inhibition235. No evidence of toxicity or increased immune infiltration of healthy tissues was observed in this preclinical setting, but further work to establish safety is necessary before clinical translation.

Outstanding questions and challenges

Several technical challenges and outstanding questions remain to be addressed to translate the above mechanistic findings into the clinic.

Mapping splicing alterations in tumors

Most of the studies to date have relied on short-read RNA-seq to characterize the AS repertoire in human tumors (Box 2). These approaches have revealed the complexity of the cancer transcriptome and the extraordinary magnitude of AS switches during cell transformation. However, short-read RNA-seq cannot reliably detect complex and/or full-length novel isoforms236. A recent LR-seq study reported that novel spliced isoforms can account for >30% of the transcriptome of breast tumors237. As LR-seq approaches become more robust and cost-effective, we anticipate that they will become part of the routine characterization of tumors and provide a more comprehensive view of the AS make-up of tumors and normal tissues. Obtaining precise sequences of full-length spliced isoforms will be critical for the identification of private or shared neoantigens and the development of immunotherapies that target splicing-derived peptides.

BOX 2 |. How to detect and quantify differential splicing.

Strengths and limitations of different techniques for detecting isoforms that are differentially spliced between biological or experimental conditions (e.g., cancer vs. normal tissues) are discussed below.

Transcriptome-wide detection of alternative splicing (AS) isoforms can be carried out using high-throughput RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) 265. Most cancer studies have used short-read RNA-seq (see panel a). Short reads are mapped to the reference transcriptome to quantify changes in splicing between conditions. Detecting novel (non-annotated) splicing involves additional steps of split read mapping, splice site inference, and de novo transcript reconstruction. Differential splicing can be quantified at the level of individual splicing events (i.e., inclusion or exclusion of a particular exon)266,267, with respect to a particular isoform (i.e., inclusion or exclusion of a particular exon within a full-length transcript)268,269 , or at the level of individual isoforms (i.e., quantifying the abundance of one isoform with respect to all other isoforms transcribed from the parent gene)270. When individual splicing events are studied, AS is typically quantified using a ‘percent spliced in’ (PSI) or ‘isoform fraction’ value ranging from 0 to 100%, defined as expression of the isoforms that follow a splicing pattern of interest relative to the total expression of all transcripts of the gene (see panel b).

Short-read RNA-seq enables researchers to generate millions of reads for AS quantification. Because of its ubiquity, short-read data can be easily compared with public datasets such as those generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects. However, isoform reconstruction and accurate quantification of full-length isoform expression are both challenging. Short-read RNA-seq permits identification of some RNA modifications directly, such as A-to-I editing, and others indirectly by immunoprecipitation and sequencing. Standard single-cell RNA-seq technologies, which preferentially sequence 3’ ends of RNAs, do not permit accurate splicing quantification.

Long-read RNA-seq (LR-seq) technologies can sequence full-length RNA isoforms (see panel a). LR-seq can reveal complex AS, novel 5’ or 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs), and gene fusions. Recent LR-seq approaches enable direct RNA sequencing and RNA modification detection236,271. However, LR-seq yields relatively few reads per sample, limiting its utility for isoform quantification. This limitation can be addressed with targeted LR-seq, such as enriching for isoforms of interest with probe capture or depleting high-abundance RNAs. Combining LR-seq for isoform identification with short-read RNA-seq for isoform quantification is effective but complex237.

Accurately quantifying splicing is challenging due to statistical considerations. Quantifying expression of AS isoforms primarily relies upon ‘informative’ reads that uniquely arise from one or more, but not all, isoforms (e.g., reads which cross exon-exon junctions that are only present in one isoform). Technical effects such as 3’ end biases can manifest as apparent differential AS. These challenges can be addressed by sequencing to high coverage, applying read coverage thresholds, and utilizing appropriate statistical tests.

Targeted experimental approaches can detect and quantify selected isoforms (see panel c). These include RT-(q)PCR utilizing isoform-specific primers, for which at least one primer should cross a splice junction to ensure that the assay queries mature mRNA. Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) can allow for absolute isoform quantification. Protein-encoding isoforms can be detected with isoform-specific antibodies. Finally, isoform-specific RNA probes enable isoform mapping and quantification with spatial resolution. Although most of these approaches are low throughput, imaging advances may enable simultaneous detection of hundreds of isoforms.

Moreover, tumors are heterogenous at both the genomic and transcriptomic levels, and one can expect a similar complexity for AS. Yet, whether distinct regions of a tumor or cell types within a tumor exhibit differences in AS remains unknown, in part because the majority of current single-cell studies are based on 3’-biased, short-read RNA-seq that cannot reliably detect AS. Recently, single-cell transcriptomic approaches coupled with LR-seq have demonstrated that full-length isoforms can be measured in single cells in the context of brain development238–240. Thus, single-cell LR-seq would be a very powerful strategy to define how AS contributes to tumor evolution and drug response and to identify tumor populations associated with drug resistance. Finally, single-cell LR-seq has been coupled with spatial transcriptomics to reveal how AS contributes to tissue development and disease241. This approach has potential utility for studying tumor initiation and progression, which have already been associated with alterations in AS.

Finally, while technologies to measure AS isoforms at the RNA level have flourished over the past ten years, detecting and measuring the encoded protein isoforms remains very difficult. The ability to measure AS isoforms using quantitative proteomics should further enable linking AS alterations to their functional roles in human malignancies and accelerate the discovery of novel druggable targets.

Defining the function of AS switches

Work from many labs has identified thousands of cancer-associated AS isoforms. Yet, the lack of high-throughput approaches to interrogate the function of spliced isoforms at scale impedes the discovery of clinically relevant and actionable AS alterations. Testing the function of individual isoforms is laborious, often requiring overexpression or knockdown of each target. This limits our ability to define the functional consequences of AS and identify key targets for therapeutic correction. Therefore, functional screens that allow for the simultaneous study of thousands of AS-derived isoforms are needed. Recently, CRISPR-based approaches have demonstrated that hundreds of exons can be individually deleted using paired gRNAs and screened for their effects on tumor cell growth226. Similarly, CRISPR-based editing can be used to mutate splice sites at scale and prevent exon inclusion242. However, these approaches target the DNA sequence and therefore could potentially also impact genome and chromatin architecture, gene transcription, and other regulatory elements. Additional strategies that model the functional consequences of other AS events besides exon skipping (i.e., intron retention, alternative splice sites, mutually exclusive exons) need to be developed in the future to enable testing the function of virtually any AS event (or combinations of AS events) of interest. Although further development is needed, RNA-targeting CRISPR approaches may be particularly useful in this context. Of note, many studies are biased towards studying NMD-inducing events, which are easier to model, and because their putative loss-of-function consequences are easier to interpret functionally compared to other AS events.

Finally, better model systems are needed to test the functional consequences of AS alterations in malignancies and to preclinically evaluate splicing-targeting therapies. These include in vitro models that recapitulate the complexity of tumors (e.g., organoids and co-culture models). Syngeneic mouse models of cancers with mutant SFs can also provide novel mechanistic insights and be used test the efficacy of splicing-modulating drugs. Humanized mouse models would further enable testing the efficacy of therapies targeting human immune cells. Many functional studies of AS using in vitro and in vivo models have primarily focused on cell growth or survival as a readout, but AS switches can impact a multitude of other important cellular phenotypes. Finally, current approaches are best-suited to modeling the functional consequences of a single AS switch per cell. As cancer cells typically exhibit AS alterations in many transcripts, accurately mimicking this will require modelling of combinatorial AS switches.

Origins and implications of AS switches

The past decade has revealed the extent of alterations in AS isoforms and SFs in cancer, but we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the functional consequences of these changes. The relative contributions of tumor-specific isoforms are still largely unknown. Is there a key set of AS isoforms that provide a growth advantage to cancer cells, or do tumors benefit from a global dysregulation of splicing, resulting in many mis-splicing events that complement each other?

Moreover, the mechanistic origins of most splicing aberrations in tumors are not yet understood. While several SFs are recurrently mutated or amplified, a large proportion of solid tumors display striking changes in AS and/or SF levels, yet do not bear genomic alterations directly affecting any SFs. Therefore, understanding the regulation of SF expression in healthy tissues and tumors should facilitate the continued development of therapies targeting splicing. Regulation of SFs at the transcriptional level (e.g., through oncogenic transcription factors such as MYC63,93,97,243,244) or post-transcriptional level (e.g., via splicing coupled to NMD216,226,245,246) at least partly controls SF levels in tumors. Much less is known about SF regulatory mechanisms at the epigenetic, translational, or post-translational levels. Although rewiring of the epigenetic landscape is a hallmark of tumors, few studies have examined how it impacts tumor-associated AS. Similarly, (post)-translational control is a crucial component of cancer development and progression, yet its impact on the splicing machinery is poorly understand. MYC activation modulates translation of the core SF SF3A3, leading to downstream changes in AS and metabolic reprograming in breast cancers247, suggesting a key link between and AS and translational control in tumors.

AS is deeply interconnected with other molecular processes, including regulatory mechanisms at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and translational levels. Therefore, cancer-driven changes in any of these mechanisms can in turn impact splicing outcomes, and vice-versa, alterations in AS can feed back on these regulatory networks. This intricate interconnectivity can be difficult to disentangle, and studies need to be carefully designed to capture and differentiate between direct and indirect effects.

Finally, many non-genetic factors influence cancer susceptibility. These include age as well as environmental and lifestyle differences, such as diet or smoking. How these factors impact AS in pre-cancerous tissues, and whether they are associated with rewiring of the AS landscape that increases cancer risk, remains to be determined.

In sum, research over the past decade has revealed that AS dysregulation is not merely an occasional correlate of cancer, but rather a near-ubiquitous and fundamental molecular characteristic that frequently plays a causative and even initiating role in tumorigenesis. Continued research should reveal new insights into the mechanistic origins and functional consequences of pervasive, cancer-specific splicing dysregulation and enable the creation of new cancer therapeutics that act by modulating RNA splicing.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Bradley and Anczukow labs for helpful discussions. O.A was supported by the NIH/NCI (R01 CA248317 and P30 CA034196) and NIH/NIGMS (R01 GM138541). R.K.B. was supported in part by the NIH/NCI (R01 CA251138), NIH/NHLBI (R01 HL128239 and R01 HL151651) and the Blood Cancer Discoveries Grant program through the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, and Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group (8023–20). R.K.B is a Scholar of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (1344–18) and holds the McIlwain Family Endowed Chair in Data Science.

Glossary

- Branch point

The branch point is a nucleotide that performs a nucleophilic attack on the 5’ splice site in the first step of splicing

- K Homology (KH)-domain

The KH domain is a protein domain that can bind RNA and is found in various RNA-binding proteins, including splicing factors

- Polypyrimidine tract (Py-tract)

The polypyrimidine tract is a pyrimidine (C or T)-rich sequence motif upstream of many 3’ splice sites that is bound by the U2AF2 subunit of the U2AF heterodimer to facilitate 3’ splice site recognition

- RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a post-transcriptional mechanism that mediates the removal of introns from a pre-mRNA transcript and the ligation of exons to form a mature mRNA

Footnotes

Competing interests

RKB is an inventor on patent applications filed by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center related to modulating splicing for cancer therapy. OA is an inventor on a patent application filed by The Jackson Laboratory related to modulating splicing factors.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Cancer thanks Maria Carmo-Fonseca, Polly Leilei Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

This Review discusses the diverse ways in which cancer-associated RNA splicing dysregulation promotes tumor initiation and progression, existing and emerging approaches for targeting splicing for cancer therapy, and outstanding questions and challenges in the field.

References

- 1.Black DL Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem 72, 291–336, doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reixachs-Sole M & Eyras E Uncovering the impacts of alternative splicing on the proteome with current omics techniques. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 13, e1707, doi: 10.1002/wrna.1707 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blencowe BJ Alternative splicing: new insights from global analyses. Cell 126, 37–47, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.023 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang ET et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456, 470–476, doi: 10.1038/nature07509 (2008). Landmark study using RNA-seq to quantify isoform expression across tissues.