INTRODUCTION

Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a heterogenous syndrome that is characterized by depressed mood and/or anhedonia with neurovegetative symptoms and neurocognitive changes experienced nearly every day for a period lasting at least 2 weeks and often associated with significant functional impairments.1–4 The landmark STAR*D study5 showed that a third of patients with MDD do not improve adequately with multiple sequential courses of antidepressants, and may have treatment-resistant depression (TRD), a complex condition frequently encountered in those undergoing treatment of MDD.2 In fact, after inadequate improvement with 2 courses of antidepressants, fewer than 1 in 6 patients with MDD attained remission (ie, no or minimal symptoms) with a third or fourth medication trial.5 The presence of TRD further exacerbates the substantial burden associated with MDD. For the patients who do not reach remission after a depressive episode, TRD should be considered. In 2008, the World Health Organization ranked the worldwide burden of disease by cause and listed major depressive disorder as the third highest cause with a prediction that, given the trajectory of the illness, depression could become the number one cause of disease burden worldwide by the year 2030.1,6 Additionally, a 2017 Lancet report by Vos and colleagues revealed that MDD was the second leading cause of global disability.7–11 More recently, estimates from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation found that 5% of adults worldwide (estimated to be more than 350 million people by current world population) suffers from depression.7,12 These sobering indicators highlight the considerable impact of MDD globally and beg the following question: how can we improve our understanding of depression and improve treatments to alleviate suffering and impairment? The answer may, in part, lie in better understanding TRD and the increased individual and societal burden associated with the illness.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime risk of experiencing an episode of depression is estimated to be 20% or close to 1 in 5 people.13,14 MDD can be diagnosed from childhood into older adulthood, with individuals being most likely to experience a first episode of depression between childhood and the fourth decade of life, although it is possible to have later onset.1 Notably, onset in later years may portend increased treatment difficulty.1,9,15–18

Increased prevalence of MDD extends from the 20s through the 30s, with the peak prevalence in adults aged from 18 to 25 years.19–22 A 2021 report showed that during a 12-month period in the United States, the prevalence of those undergoing medical treatment of MDD was estimated to be 8.9 million adults and of those, 2.8 million were considered to have TRD.23 Additionally, recent studies have estimated that MDD rapidly increased in prevalence since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.24,25 This increase is alarming and underscores the need for a better understanding of the disease, including the role of biological and social stressors in the disease process, and improved treatments. The recognition of sex as a biological variable and other sociodemographic factors are also important in understanding MDD.14 Women are nearly twice as likely to have depression compared with men.26 This so-called gender gap is likely due to an interplay of biopsychosocial factors and is an intriguing area for future cross-disciplinary research.1,6,15–17,26 When stratified based on other factors, many studies have not shown significant differences in the prevalence of depression based on the income level of an entire country (developed nations versus lower income nations).1 However, significant differences in prevalence of MDD have been shown based on the socioeconomic status, cultural background, and early life experiences of an individual.1,27–31

CAUSE

To treat any disease effectively, basic mechanistic and environmental factors should be understood for the development of novel therapeutic targets. Despite decades of research, there is still much to learn about the functional, molecular, and genetic underpinnings of depression. MDD is a complex disease without a singular cause; rather, the disorder is multifactorial with genetic, epigenetic, biological, environmental, structural, and social factors working together in an intricate network on an individual level making defining treatment targets challenging.1,32–36 Although strides in the treatment of MDD both pharmacologic and interventional in nature have been made, MDD remains incompletely understood.1,35,37 Much of the early research on depression was focused on the monoamine neurotransmitter hypothesis for depression and elucidating the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in depression.38–40 More recently, studies have shifted to better understand the role of inflammation in depression, environmental stress, genes and epigenetic changes, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and neurogenesis, as well as structural and functional analyses of the brain, including aberrant neurocircuits, because technological advancements in neuroimaging and other methods (such as EEG) have been made.1,41–46

Diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder

For a diagnosis of MDD by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), at least 5 of 9 criteria for depression must be met including the requirement that either depressed mood or anhedonia (lack of interest in things once found enjoyable) is present (criterion A) and represents a departure from the individual’s baseline functioning.4 Briefly, other diagnostic criteria (criterion B) include the following: significant weight loss (or weight gain), insomnia (or hypersomnia), psychomotor retardation (or agitation), reduced energy (or fatigue), feelings of worthlessness (or guilt), poor concentration, and/or recurrent thoughts of suicide or death.4 Diagnosis also requires that symptoms are not caused by the effects of substance use or other medical condition (criterion C), requires absence of lifetime manic or hypomanic-like episode (criterion D) and require that symptoms are not better explained by a psychotic or schizophrenia spectrum illness, or the like (criterion E).4 Each of these criteria can be found outlined in greater detail in the DSM-5-TR.3,4

VARIATION IN ILLNESS PRESENTATIONS

Given the complexities of the biopsychosocial interactions, presentations of disease can vary from patient to patient. These differences in presentation give way to varying degrees of functional impairment and therefore perception of illness burden by the individual even when overall illness severity seems to be similar.1,47 To better understand these nuanced differences between experiences, it may be useful to describe episodes of depression using additional specifiers such as those found in the DSM-5-TR and by functional outcomes (such as quality of life, productivity, and the like).3,48–51 Furthermore, discrete episodes of depression may have other prominent emotions, behaviors, and variations in severity, which can contribute to the overall illness burden experienced at an individual level.1,3 When present, a description of features of the illness and specifiers describes a more complete clinical picture.1,14,29,52 Additionally, illness severity is a useful measure that can be accomplished through rating scales such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), or the like, although clinical judgement still plays a critical role in gauging severity of illness.28,53

Anxious distress is the most frequently observed and should not be confused with a comorbid diagnosis of anxiety, which is also frequently occurs in those with MDD.1 Notably, anxious distress has been linked to a poorer response to commonly used antidepressants (with the exception of ketamine).54 Other prominent features such as irritability, somatic complaints, and panic are also seen. Irritability is unique among these symptoms because it is considered a criterion symptom of MDD for children and adolescents but not for adults. However, recent studies have shown that presence of irritability (and its related construct of anger attacks) is associated with poorer long-term outcomes (such as persistently elevated suicidal ideation) and that treatment-related changes in irritability can be used to prognostic clinical outcomes including remission and long-term levels of suicidal ideation.55–58 Although no formal specifier exists for these, it is still important to capture their presence when part of the clinical picture of a depressive episode. Features such as irritability or somatic complaints can be more commonly observed within certain populations.28,56,57

Just as variations are observed in the symptoms and presentation of depression, variations in the duration of a single episode of depression have also been observed.1,59 The average duration for a depressive episode, with treatment, is around 3 to 6 months before remission is reached.59 However, studies have reported depressive episodes lasting up to 12 months.1,59 Moreover, other comorbid illnesses can affect the duration and quality of a depressive episode.1,6,9,60

Treatment-Resistant Depression

Landmark studies, such as STAR*D, have shown that only around 30% of individuals undergoing “adequate treatment” for MDD will achieve full remission of depression after the first antidepressant trial.1,5,27,33,37 In fact, most individuals who are treated for MDD either experience a partial response (20%) or no response to the first treatment (50%).5,27 These treatment partial and nonresponders provide the basis for the concept of TRD.37,61 TRD should not be confused with a recurrent episode of major depression where the patient previously achieved a period of remission after successful treatment of an episode of depression and experiences another separate and distinct episode of depression. Additionally, it is worth noting that the likelihood of having a recurrent episode of depression increases with increased resistance to treatment.33,37

TRD is a complex condition evaluated within the context of MDD.27,62,63 The concept of treatment resistance is not exclusive to MDD and can also be experienced in bipolar depression and in other psychiatric illnesses.27,62,63 However, more studies have focused on unipolar depression concerning TRD.64 To date, no consensus diagnostic criteria with a consistently applied treatment algorithm exists for TRD making the study of TRD difficult.27,62,63 Given the context of MDD, the cause of TRD is also multifactorial with genetic, epigenetic, biochemical, structural, environmental, and social factors and is not intrinsically resistant to treatment itself despite the current naming convention.1,27,37 The contribution of each of these factors likely varies from individual to individual adding an additional layer of complexity in understanding the disorder, further convoluting the elucidation of disease mechanisms, and making robust treatment options elusive. The multifaceted cause of TRD and differences in patient presentations with the disorder have made it both diagnostically challenging and difficult when synthesizing the limited evidenced-based findings obtained to date. Furthermore, it has been suggested that TRD could be evaluated along a spectrum rather than by a binary approach (whether a patient has TRD or not).27 TRD as a spectrum may better represent the diversity of disease seen in practice and myriad of treatment responses observed.

Although the cause of TRD remains enigmatic, certain characteristics, exposures, and comorbid conditions have been identified as risk factors for the development of TRD. Some of the risk factors include the following: comorbid psychiatric illnesses (especially anxiety, substance use disorders, and personality disorders), chronic medical conditions (including pain and inflammatory conditions), and social vulnerabilities (eg, unemployed, divorced, widowed).65–71 Moreover, extremes of age, severity of illness, and melancholic features have also been shown to be risk factors for TRD.65–71 Additional risk factors are likely to emerge as more studies are conducted in patients with TRD. Individuals with TRD typically have more comorbidities than those who respond well to treatment and may suggest some degree of biological “loading”; this remains incompletely understood and could be targeted in future research.66,72,73

Diagnosis of treatment-resistant depression

The most referenced “criteria” for the diagnosis of TRD require “a minimum of two prior treatment failures and confirmation of prior adequate dose and duration.”27 Despite the morbidity associated with TRD during the last almost 30 years, there is substantial uncertainty among experts or evidence-based guidelines outlining which pharmacologic intervention is preferred and what constitutes an adequate pharmacologic dose or treatment duration to be considered an adequate medication trial. A recent systematic review by Gaynes and colleagues27 found that out of 185 studies only around 19% applied all components of the most used criteria for TRD. Complicating matters further, there is no consensus whether the adequate medication trial must be for a current episode of depression versus lifetime treatment failures. Furthermore, there was no clear definition for an adequate treatment duration varying from 3 to 12 weeks across the studies analyzed with 4 weeks typically representing the minimum treatment duration.27 Given the multiple definitions and interpretations of what constitutes treatment resistance and adequate treatment attempts, McAllister-Williams and colleagues proposed the concept of “difficult-to-treat depression” over the naming convention of TRD. The term “difficult-to-treat depression” does not single out any one factor contributing to the continuing burden of illness experienced by the patient and allows for a more patient-centered approach where all treatment modalities are considered.74

In 2020, Gaynes and colleagues described screening tools useful in the diagnosis of TRD and assessment of severity of illness. The Antidepressant Treatment History Form stratifies resistance based on prior antidepressant trials with a higher score suggestive of worse patient outcomes and is primarily intended for use in research settings.27,75 Similarly, the Thase and Rush Staging model and related European Staging model and the Massachusetts General Hospital Staging model also consider the number of antidepressant classes and therapies previously failed by an individual, exposure to a particular treatment (ie, duration), and other treatment strategies considered (such as augmentation), although not every model individually considers each of these factors.27 Additionally, the Maudsley staging method (MSM) has been shown to predict treatment resistance in 85% of prospective cases studied.76 This model includes the assessment of baseline characteristics not queried in the other models. The Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire, a patient self-reported scale, has also been validated and identified around 76% of those with TRD in agreement with the independent examiners in the trial.77 A newer model, the “Karolinska Institutet (sic) Model” (KIM) as described by Hägg and colleagues,78 utilizes a precise definition for treatment duration as well as consideration of combination, adjunctive, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatments.

PSEUDORESISTANCE

If TRD is suspected, it is necessary to ensure all diagnostic possibilities have been considered because symptoms reported are not pathognomonic for depression. Care must be taken to distinguish depression from other psychiatric disorders, including other affective disorders. The psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire (PDSQ), as well as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) can be useful tools to screen for other common psychiatric diagnoses.33,37,79–81 Additionally, medical illnesses may have similar symptomatology (eg, hypothyroidism) and a thorough medical history should be performed.82 Similarly, pharmacologic effects (substance use or medication side effects) can also mimic symptoms of depression and should be considered.1 Therefore, treatment nonresponse is not always indicative of TRD, rather, in some instances may indicate an incorrect diagnosis.

When considering reasons for treatment failure, it is also important to verify reported failed medication trials because there could be discrepancies related to recall and medication adherence. Not taking medication correctly can occur for a myriad of reasons including the inability to pay for treatment.83 In such instances, the patient would not have undergone an adequate trial although they may consider it a failed trial. It is also possible that individuals may inadvertently underestimate how long they were on an earlier medication when discussing past medication trials.

TRACKING TREATMENT OUTCOMES

Impaired function may persist with TRD irrespective of remission of other clinical symptoms.84,85 Furthermore, the protracted course of illness with TRD makes assessing changes in disease progression challenging. Measurement-based care can be accomplished through a variety of rating scales (detailed in a subsequent section) and should be utilized for tracking treatment outcomes.1,84,85 Similarly, quality of life measures should be considered when tracking outcomes.80,85 The selection of which screening instrument is best to use often depends on practice location (ie, acute care setting versus clinic) and purpose (ie, establishment of care with a provider versus research) and time constraints.28,53,86

THE BURDEN OF DEPRESSION

Quality of Life

It is well known that depression has a negative impact on an individual’s quality of life. However, like the concept of quality of life itself, the subjective degree of burden experienced by an individual with depression has been difficult to quantify; measures such as the global assessment of functioning and quality of life scale are useful in assessing the concept at an individual level.87 Moreover, the recent COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on quality of life has had a profound impact on mental health, the outcomes of which remain to be seen.88 The determinants of quality of life focus on physical, mental, and social components working together.89 Per the CDC definition, health-related quality of life is defined as, “an individual’s or group’s perceived physical and mental health over time.”89

Those with MDD have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and other chronic medical illnesses.90–92 Individuals with TRD have been reported to have increased distress and poor overall global functioning.88,93 A Korean study of depressed individuals by Cho and colleagues94 found that quality of life varied with age, weight, socioeconomic status, perception of one’s own health, level of education, and employment status. Obesity, older age, lower income and education, unemployment, and perception of poor health all correlated with lower quality of life.94 Similarly, comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety and substance use disorder, have also been shown to worsen an individual’s quality of life.95 Anxiety is one of the most common co-occurring psychiatric disorders with MDD and has been reported to be diagnosed in almost two-thirds of those with MDD and is often even observed before MDD diagnosis.96

Psychosocial Functioning and Productivity

Failing to treat childhood depression often results in a depressed and functionally impaired adult highlighting the “developmental cost” of depression.28,97 The very nature of depression inhibits psychosocial functioning, causing individuals to have low-energy levels, poor sleep, and limits interpersonal interactions.1,3 Individuals with depression often face extreme feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, or guilt, further isolating them from engaging with others.1,3 Findings from a STAR*D secondary analysis showed sad mood and concentration (a subdomain of cognition) to be the most significant psychosocial functional domains affected.98

Depression is a significant cause of decreased work productivity as well as activity impairment, which can in part be attributable to the cognitive dysfunction associated with depression.99 Changes in learning, memory, attention, concentration, and the like can continue even after resolution of the depressive episode.99 This fact is compounded when decreased work productivity translates into decreased wages and increased unemployment.1,88,100,101 Areas impacted, such as such as caring for a child or interactions with a partner often have far-reaching consequences to the patient and those who interact with them.78 Too often these additional aspects of the patient’s life are not fully captured in the clinical setting but are important for a holistic evaluation of the patient. Additionally, better understanding the domains affected for that individual will aid in assessing the overall disease burden experienced and will better facilitate connecting individuals with resources most useful for them.

Economic impact

The economic burden of depression is profound both at an individual and societal level. Moreover, studies have shown that TRD is costlier than treatment-responsive MDD due to the protracted duration of an individual episode affecting not only the individual with TRD but also others within their sphere of influence including family, caregivers, and employers.27,102,103 Furthermore, individuals with TRD are 2 times more likely to endure hospitalization than those with treatment-responsive depression.27,104 Adding to the economic burden of TRD, hospitalizations of individuals with TRD costs almost 6 times more on average than hospitalizations of individuals with treatment-responsive MDD.27,105 Ivanova and colleagues105 reported that TRD nearly doubles the employer-related costs compared with treatment-responsive depression. Those with treatment-responsive depression and commercial insurance spend an estimated US$9,975 after a single medication trial when treated to remission within the first 12 months of starting treatment. However, individuals with TRD who also have commercial insurance incur medical expenses estimated to be US$21,259 in the first 12 months after initiating treatment and undergo 3 or more treatment trials within that period.106 Given these estimated costs are for those with commercially held insurance, the costs are conceivably much higher for those without insurance. Recent reports have indicated that uninsured individuals are more likely to face treatment barriers and inconsistently engage with the health-care system.107 Similarly, uninsured individuals are sometimes faced with the burden to afford either medications or food.83 For these reasons, uninsured individuals often go untreated or undertreated, which has significant implications on the individuals themselves and society overall.83

On a national level, reports have estimated the overall annual cost of depression to be around US$326 billion, an increase from the 2010 estimate of US$236 billion.22 Of the factors considered, the greatest increase observed was due to workplace costs that was accountable for 61% of costs and was increased from 48% estimated in 2010. Moreover, findings from a recent study by Zhdanava and colleagues23 in US adults undergoing treatment of depression estimated that US$92.7 billion and US$43.8 billion were spent because of MDD and TRD, respectively. Additionally, Zhdanava and colleagues report that the TRD represented US$25.8 billion of the “health care burden,” US$8.7 billion of the “unemployment burden,” and US$9.3 billion of the “productivity burden” associated with those on medication for the treatment of MDD. From a global perspective, depression and anxiety combined are estimated to cost the global economy around US$1 trillion annually in lost productivity.108

The individual and societal burden of suicide

Suicide is a leading cause of death, especially in those aged between the ages of 10 and 34 years.57,109 Notably, this age range also corresponds with the highest prevalence of depression.1,22 It is also well established that individuals with depression have a higher risk of suicide and suicide attempts.1,57 Furthermore, those with TRD have an even higher risk of suicide than those with treatment-responsive depression and should be considered as a distinct outcome in future research studies in this population.110

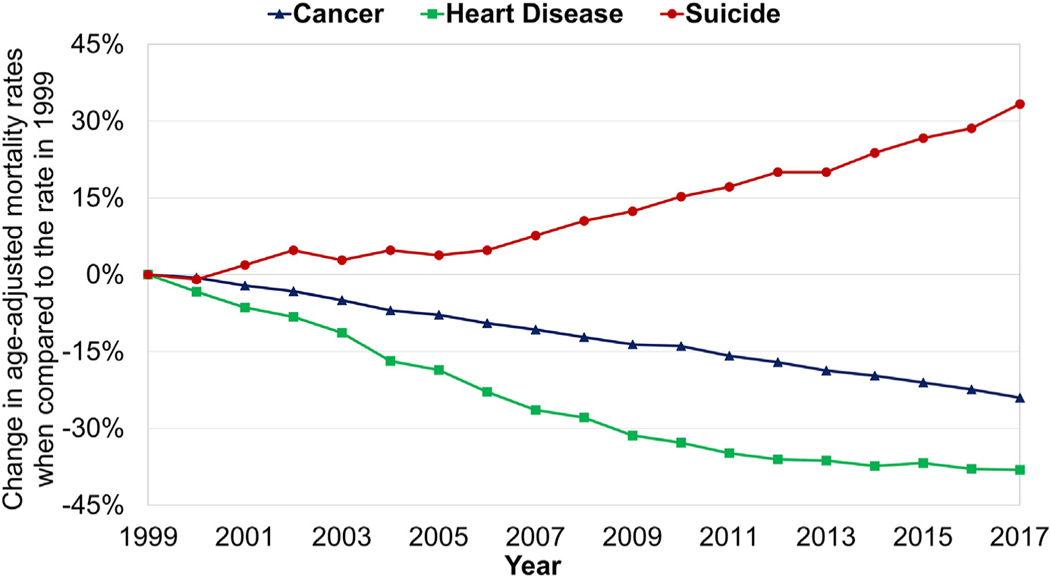

During the last 20 years, the rate of suicide has continued to increase, whereas other major burdens of disease such as cancer and heart disease have declined (Fig. 1).109 Furthermore, individuals who attempt suicide are often seen in the emergency department adding to the overall economic and societal burden of depression.22 On an individual level, it can be devastating for the loved ones left behind and can create lasting consequences potentially affecting the mental health of the next generation.111 Failed suicide attempts can also bring a new element of trauma to the already suffering individual.112

Fig. 1.

Change in age-adjusted mortality rate due to suicide in the United States between 1999 and 2017. Age-adjusted mortality rates for suicide, cancer, and heart disease were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics dataset.109 The age-adjusted rate in the year 1999 was set as baseline and percent change was calculated for each year. Although rates of cancer and heart disease declined by 24.1% and 38.1%, respectively, the age-adjusted mortality rate of suicide increased by 33.3% between 1999 and 2017.

Lessons learned in improving health outcomes in other medical fields, such as cardiology and cancer, have demonstrated that the identification and utilization of biomarker-guided therapy reduces overall morbidity and mortality for the disease.113,114 Unfortunately, no validated biomarkers currently exist to guide the treatment of depression.115 However, cross-disciplinary research approaches seek to elucidate the brain–heart axis, among other promising areas of research.116 Future research studies to elucidate biomarkers for depression are likely to aid in the reduction of suicidality in MDD patients and guide treatments for best outcomes. Other features and measures linked with MDD, such as irritability, should also be considered for future research to better understand this vulnerable population.57

DISCUSSION

Barriers to treatment are multifactorial and often mirror the unique biopsychosocial landscape of the individual seeking treatment. The ability to accurately and efficiently stratify need based care is increasingly difficult given the lack of a standardized definition of TRD, the different treatment strategies utilized, the paucity of evidence-based treatment data for TRD, and the significant economic impact both to the individual and society.27 This treatment conundrum can, in and of itself, act as a barrier to treatment. Moreover, this barrier is often compounded in the pediatric patient population because the therapeutic approach to TRD in these patients is largely based on the adult literature.27,28 Evidence-based data in the pediatric population are even more limited to the few clinical trials that have been conducted. Treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) trial has been the only large-scale trial to address TRD in the pediatric population.28,117,118 Of the adult trials that have focused on TRD, the lack of consensus definition of adequate treatment dose and duration has made interpreting findings challenging and limits our ability to compare trials or conduct meta-analyses.27 However, while the individual and societal burden of depression is immense, especially in cases of TRD, the complexity of the disorder allows for the exciting possibility of personalized therapeutic options in the future.1,37 Furthermore, improved understanding of TRD can bring about substantial cost savings both for the individual with depression and society overall.

SUMMARY

Given the far-reaching global consequences of depression, governments and other funding institutions must engage in supporting research endeavors to alleviate the burden of depression and better understand this complex illness. A consensus definition and treatment strategy for TRD is essential to help close the knowledge gap that currently exists. More robust research, including randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, can be performed once this critical illness is better defined leading to better understanding of the illness itself, improved treatment options, and better outcomes for our patients worldwide.

KEY POINTS.

Depression is a significant cause of disease burden and disability worldwide.

Depression has a high economic cost for the individual and society.

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) lacks a consensus definition and does not have a standard treatment algorithm.

TRD is associated with protracted burden of disease and is associated with higher treatment costs to the individual and a broader economic impact.

Consensus definition and additional research on TRD is essential for improved treatment strategies and cost savings.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

Clinicians should be mindful of a patient’s prior medication trials for depression. If the patient has already tried 2 different anti-depressants for adequate dose and duration, treatment-resistant depression (TRD) should be considered.

Screening instruments, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), can be utilized in the clinic to track how a patient is responding to treatment.

Interventional treatment options, such as ECT, as well as clinical trial referral should be considered for TRD patients.

The “hidden costs” of depression, such as difficulty with interpersonal relationships and economic losses, should be considered in individuals with TRD. Individualized community, therapy, and other resources should be offered, when appropriate.

If TRD is being considered as a diagnosis, care must be taken to rule out any possible underlying medical or organic causes and other co-morbidities (e.g. hypothyroidism, sleep apnea, etc…).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Dr M.K. Jha has received contract research grants from ACADIA Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine Bioscience, Navitor/Supernus and Janssen Research & Development, educational grant to serve as Section Editor of the Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Learning Network, consultant fees from Eleusis Therapeutics US, Inc, Janssen Global Services, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Worldwide Clinical Trials/Eliem, and Guidepoint Global, and honoraria from North American Center for Continuing Medical Education, Medscape/WebMD, Clinical Care Options, and Global Medical Education. Dr M.H. Trivedi is or has been an advisor/consultant and received fees from Alkermes Inc, Axsome Therapeutics, Biogen MA Inc., Cerebral Inc., Circular Genomics Inc, Compass Pathfinder Limited, GH Research Limited, Heading Health Inc, Janssen, Legion Health Inc, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Mind Medicine (MindMed) Inc, Merck Sharp & Dhome LLC, Naki Health, Ltd., Neurocrine Biosciences Inc, Noema Pharma AG, Orexo US Inc, Otsuka American Pharmaceutical Inc, Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical Inc, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc, Praxis Precision Medicines Inc, SAGE Therapeutics, Sparian Biosciences Inc, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, Titan Pharmaceuticals Inc, and WebMD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018;392(10161):2299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhi GS, Das P, Mannie Z, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: problematic illness or a problem in our approach? Br J Psychiatry 2019;214(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. 5th edition, Text revision. ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. p. 1050, lxix. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(11):1905–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evaluation IoHMa. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/d780df fbe8a381b25e1416884959e88b. Accessed June 28, 2022.

- 8.Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390(10100):1211–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organization TWH. Depresion and Other Common Mental Disorders: GlobalHealth Estimates. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedrich MJ. Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability Around the World. JAMA 2017;317(15):1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Disease GBD. Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392(10159):1789–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bank TW. Population, total. The World Bank. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL. Accessed June 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med 2011;9:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatr 2018;75(4):336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:119–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirschfeld RM. The epidemiology of depression and the evolution of treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73(Suppl 1):5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med 2010;40(6):899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27(8):959–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health NIoM. Major Depression. National Institute of Mental Health. Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression. Accessed June 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nihalani N, Simionescu M, Dunlop BW. Depression: phenomenology, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. In: Schwartz TL, TPeterson TJ, editors. Depression: treatment strategies and management. CRC Press; 2016. p. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62(6):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics 2021;39(6):653–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, et al. The Prevalence and National Burden of Treatment-Resistant Depression and Major Depressive Disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry 2021;82(2). 10.4088/JCP.20m13699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes JP. Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2018;(303):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Abdalla SM, et al. Persistent depressive symptoms during COVID-19: a national, population-representative, longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;5:100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuehner C Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatr 2017;4(2):146–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 2020;37(2):134–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dwyer JB, Stringaris A, Brent DA, et al. Annual research review: defining and treating pediatric treatment-resistant depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2020;61(3):312–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malhi GS, Outhred T, Hamilton A, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: major depression summary. Med J Aust 2018;208(4):175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Aquino J, Londono A, Varvalho AF. An update on the epidemiology of major depressive disorder across cultures. In: Kim Y-K, editor. Understanding depression. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 309–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol 2012;233(1):102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med 1996;26(3):477–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004; 25(1):119–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fabbri C, Corponi F, Souery D, et al. The genetics of treatment-resistant depression: a critical review and future perspectives. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2019;22(2):93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, et al. Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): acute and long-term outcomes of a single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(7):689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park C, Rosenblat JD, Brietzke E, et al. Stress, epigenetics and depression: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;102:139–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(1):28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirschfeld RM. History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(Suppl 6):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci 2008;31(9):464–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segal DS, Kuczenski R, Mandell AJ. Theoretical implications of drug-induced adaptive regulation for a biogenic amine hypothesis of affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1974;9(2):147–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohoff FW. Overview of the genetics of major depressive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010;12(6):539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301(23):2462–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charney DS, Manji HK. Life stress, genes, and depression: multiple pathways lead to increased risk and new opportunities for intervention. Sci STKE 2004; 2004(225):re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein MB, Campbell-Sills L, Gelernter J. Genetic variation in 5HTTLPR is associated with emotional resilience. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2009; 150B(7):900–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polanczyk G, Caspi A, Williams B, et al. Protective effect of CRHR1 gene variants on the development of adult depression following childhood maltreatment: replication and extension. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66(9):978–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H, Tian X, Wang X, et al. Evolution and emerging trends in depression research from 2004 to 2019: a literature visualization analysis. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:705749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;374(9690):609–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greer TL, Trombello JM, Rethorst CD, et al. Improvements in psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life following exercise augmentation in patients with treatment response but nonremitted major depressive disorder: results from the tread study. Depress Anxiety 2016;33(9):870–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jha MK, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Early normalization of Quality of Life predicts later remission in depression: Findings from the CO-MED trial. J Affect Disord 2016;206:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, Greer TL, et al. Early improvement in work productivity predicts future clinical course in depressed outpatients: findings from the COMED trial. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(12):1196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jha MK, Teer RB, Minhajuddin A, et al. Daily activity level improvement with antidepressant medications predicts long-term clinical outcomes in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017;13:803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49(12):1087–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-Based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172(10):1004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thase ME, Weisler RH, Manning JS, et al. Utilizing the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier to develop treatment strategies for patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatr 2017;78(9):1351–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, South C, et al. Worsening anxiety, irritability, insomnia, or panic predicts poorer antidepressant treatment outcomes: clinical utility and validation of the concise associated symptom tracking (CAST) scale. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2018;21(4):325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, South C, et al. Irritability and its clinical utility in major depressive disorder: prediction of individual-level acute-phase outcomes using early changes in irritability and depression severity. Am J Psychiatr 2019;176(5): 358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, Chin Fatt C, et al. Association between irritability and suicidal ideation in three clinical trials of adults with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45(13):2147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jha MK, Fava M, Minhajuddin A, et al. Association of anger attacks with suicidal ideation in adults with major depressive disorder: Findings from the EMBARC study. Depress Anxiety 2021;38(1):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, et al. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. A 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49(10):809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verduijn J, Verhoeven JE, Milaneschi Y, et al. Reconsidering the prognosis of major depressive disorder across diagnostic boundaries: full recovery is the exception rather than the rule. BMC Med 2017;15(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;19(2):179–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berlim MT, Fleck MP, Turecki G. Current trends in the assessment and somatic treatment of resistant/refractory major depression: an overview. Ann Med 2008; 40(2):149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(2):217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baldessarini RJ, Vazquez GH, Tondo L. Bipolar depression: a major unsolved challenge. Int J Bipolar Disord 2020;8(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li JM, Zhang Y, Su WJ, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2018;268: 243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lahteenvuo M, Taipale H, Tanskanen A, et al. Courses of treatment and risk factors for treatment-resistant depression in Finnish primary and special healthcare: a nationwide cohort study. J Affect Disord 2022;308:236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cepeda MS, Reps J, Ryan P. Finding factors that predict treatment-resistant depression: Results of a cohort study. Depress Anxiety 2018;35(7):668–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dome P, Kunovszki P, Takacs P, et al. Clinical characteristics of treatment resistant depression in adults in Hungary: real-world evidence from a 7-year-long retrospective data analysis. PLoS One 2021;16(1):e0245510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balestri M, Calati R, Souery D, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of treatment resistant depression: a prospective European multicenter study. J Affect Disord 2016;189:224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murphy JA, Sarris J, Byrne GJ. A review of the conceptualisation and risk factors associated with treatment-resistant depression. Depress Res Treat 2017;2017: 4176825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gronemann FH, Jorgensen MB, Nordentoft M, et al. Incidence of, risk factors for, and changes over time in treatment-resistant depression in denmark: a register-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79(4). 10.4088/JCP.17m11845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 16):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang SS, Chen HH, Wang J, et al. Investigation of early and lifetime clinical features and comorbidities for the risk of developing treatment-resistant depression in a 13-year nationwide cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20(1):541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McAllister-Williams RH, Arango C, Blier P, et al. The identification, assessment and management of difficult-to-treat depression: an international consensus statement. J Affect Disord 2020;267:264–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Kartachov A, et al. A computer algorithm for calculating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment in unipolar and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(7):825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fekadu A, Wooderson S, Donaldson C, et al. A multidimensional tool to quantify treatment resistance in depression: the Maudsley staging method. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(2):177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: Validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther 2010;16(5):322–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hagg D, Brenner P, Reutfors J, et al. A register-based approach to identifying treatment-resistant depression-Comparison with clinical definitions. PLoS One 2020;15(7):e0236434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(Suppl 20):22–33 [quiz: 34–57]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perkey H, Sinclair SJ, Blais M, et al. External validity of the psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire (PDSQ) in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Res 2018;261:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry 2001;42(3):175–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hage MP, Azar ST. The Link between thyroid function and depression. J Thyroid Res 2012;2012:590648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, et al. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health 2015;105(10):e48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Morris DW, et al. Concise health risk tracking scale: a brief self-report and clinician rating of suicidal risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72(6):757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trivedi MH, Morris DW, Wisniewski SR, et al. Increase in work productivity of depressed individuals with improvement in depressive symptom severity. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170(6):633–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hong RH, Murphy JK, Michalak EE, et al. Implementing measurement-based care for depression: practical solutions for psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2021;17:79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burckhardt CS, Anderson KL. The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): reliability, validity, and utilization. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Proudman D, Greenberg P, Nellesen D. The growing burden of major depressive disorders (MDD): Implications for Researchers and Policy Makers. Pharmacoeconomics 2021;39(6):619–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prevention CfDCa. Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/concept.htm. Accessed June 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dhar AK, Barton DA. Depression and the link with cardiovascular disease. Front Psychiatry 2016;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seligman F, Nemeroff CB. The interface of depression and cardiovascular disease: therapeutic implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015;1345:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thom R, Silbersweig DA, Boland RJ. Major depressive disorder in medical illness: a review of assessment, prevalence, and treatment options. Psychosom Med 2019;81(3):246–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shah D, Allen L, Zheng W, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression among adults with chronic non-cancer pain conditions and major depressive disorder in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2021;39(6):639–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cho Y, Lee JK, Kim DH, et al. Factors associated with quality of life in patients with depression: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 2019;14(7): e0219455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thaipisuttikul P, Ittasakul P, Waleeprakhon P, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10: 2097–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goldberg D, Fawcett J. The importance of anxiety in both major depression and bipolar disorder. Depress Anxiety 2012;29(6):471–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dunn V, Goodyer IM. Longitudinal investigation into childhood- and adolescence-onset depression: psychiatric outcome in early adulthood. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fried EI, Nesse RM. The impact of individual depressive symptoms on impairment of psychosocial functioning. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e90311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pan Z, Park C, Brietzke E, et al. Cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr 2019;24(1):22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trivedi MH, Corey-Lisle PK, Guo Z, et al. Remission, response without remission, and nonresponse in major depressive disorder: impact on functioning. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;24(3):133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mauskopf JA, Simon GE, Kalsekar A, et al. Nonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety 2009;26(1):83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cai Q, Sheehan JJ, Wu B, et al. Descriptive analysis of the economic burden of treatment resistance in a major depressive episode. Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36(2):329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lerner D, Lavelle TA, Adler D, et al. A population-based survey of the workplace costs for caregivers of persons with treatment-resistant depression compared with other health conditions. J Occup Environ Med 2020;62(9):746–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, et al. The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(11): 963–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26(10):2475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Arnaud A, Suthoff E, Tavares RM, et al. The increasing economic burden with additional steps of pharmacotherapy in major depressive disorder. Pharmacoeconomics 2021;39(6):691–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rezaeizadeh A, Sanchez K, Zolfaghari K, et al. Depression screening and treatment among uninsured populations in Primary Care. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2021;21(3):100241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.The Lancet Global H Mental health matters. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8(11): e1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS - Leading Causes of Death: United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Available at: https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/NCHS-Leading-Causes-of-Death-United-States/bi63-dtpu, Accessed April 6, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bergfeld IO, Mantione M, Figee M, et al. Treatment-resistant depression and suicidality. J Affect Disord 2018;235:362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.de Leo D, Heller T. Social modeling in the transmission of suicidality. Crisis 2008; 29(1):11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stanley IH, Boffa JW, Joiner TE. PTSD from a suicide attempt: phenomenological and diagnostic considerations. Psychiatry. Spring 2019;82(1):57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Saijo N Critical comments for roles of biomarkers in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2012;38(1):63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sarhene M, Wang Y, Wei J, et al. Biomarkers in heart failure: the past, current and future. Heart Fail Rev 2019;24(6):867–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Strawbridge R, Young AH, Cleare AJ. Biomarkers for depression: recent insights, current challenges and future prospects. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017;13:1245–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Beis D, Zerr I, Martelli F, et al. RNAs in brain and heart diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21(10). 10.3390/ijms21103717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Emslie GJ. Improving outcome in pediatric depression. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299(8):901–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]