Introduction

The use of radionuclides for the imaging and treatment of cancer has undergone a dramatic transformation in the 80 years since Saul Hertz first attempted to treat thyroid cancer patients with radioiodine. While the field has undergone ebbs and flows in the intervening decades, it is hard to deny that the present represents a pivotal moment for the use of radiopharmaceuticals in oncology. Indeed, the increased clinical use of radiopharmaceuticals for both diagnosis and therapy, a surge in regulatory approvals, and an upwelling of preclinical research have combined to bring targeted radiopharmaceuticals — and especially radiopharmaceutical therapies (RPTs) — into the oncologic mainstream. In light of this advent, we offer this timely review of the most exciting recent developments in the field as well as the obstacles that must be overcome for it to continue on its remarkable trajectory. For the ease of the reader, we have divided the work into two sections: the first addresses the basic, preclinical, and clinical science underpinning the field (Scientific Developments), while the second addresses how the scientific and clinical work is performed (Operational Developments).

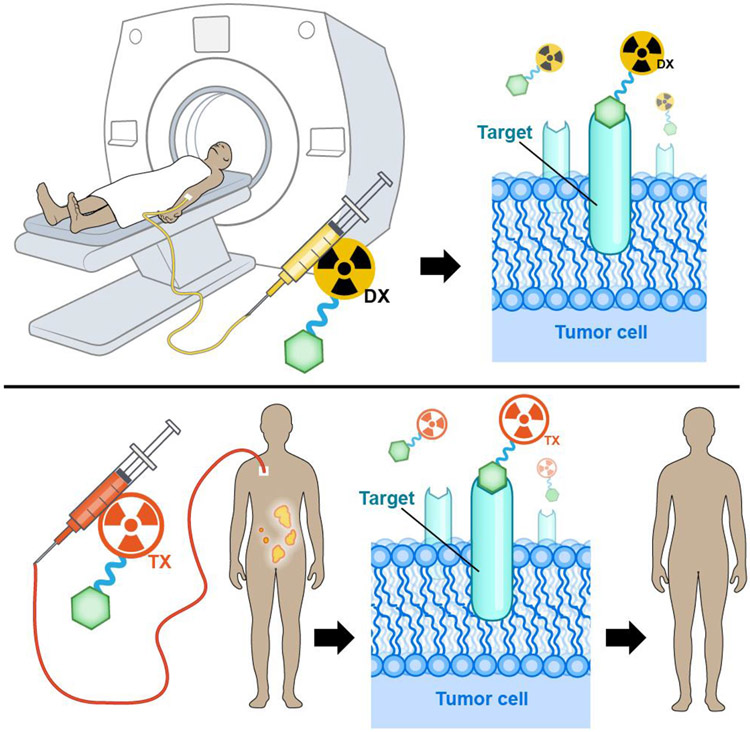

Before we begin, however, it is important to cover the fundamentals so that readers — from medical students to veterans in the field — begin on the same page. A radiopharmaceutical combines a radionuclide that emits imageable and/or therapeutic radiation with a carrier molecule that delivers the radionuclide to the target (though in some cases, radioiodine for example, the nuclide itself is responsible for both targeting and irradiation) (Figure 1). Many radiopharmaceuticals are labelled with metallic radionuclides and thus need a third component: a chelator that stably binds the radiometal to the radiopharmaceutical during its transit throughout the body. For imaging, the radionuclide should emit either positrons for positron emission tomography (PET) or photons for single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). For radiopharmaceutical therapy, radionuclides that emit ß− particles (electrons) have proven highly effective in clinical practice (1-3). In addition, isotopes that produce α particles (4-6) — emissions capable of depositing extremely high amounts of energy across their short path-lengths — have been used clinically [e.g. 223RaCl2 (Xofigo®)] and have shown promise in advanced clinical trials (e.g. [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-TATE; [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617). Finally, radiopharmaceuticals containing Auger-electron-emitting nuclides remain predominantly in the preclinical arena, though a handful of centres have translated them to the clinic (7)

FIGURE 1:

Illustration of how radiotheranostics are used: imaging scans acquired using a tumour-targeting vector (green hexagon) labelled with a diagnostic radionuclide (yellow) facilitate patient selection, individualized dosimetry, and treatment monitoring for radiopharmaceutical therapy using the same vector labelled with a therapeutic radionuclide (orange).

The efficacy of a radiopharmaceutical ultimately depends on its component parts. The pharmacokinetic profile of a radiopharmaceutical is generally determined by the carrier molecule. Ideally, radiopharmaceuticals should accumulate rapidly in tumour tissues, eschew healthy tissues, and be excreted as quickly as possible from non-target tissues. Internalising radiopharmaceuticals are often desirable(8) insofar as the sequestration of radioactivity inside tumour cells increases the cytotoxicity of many radionuclides (for RPT) and minimizes the radiopharmaceutical’s redistribution throughout the body (for both RPT and imaging). Likewise, the rapid excretion of any unbound radiopharmaceutical decreases background signal in healthy organs and reduces radiation damage to non-target tissues. Given these requirements, vectors including small molecules, peptides, and low-molecular-weight proteins such as antibody fragments are particularly well-suited to the creation of radiopharmaceuticals. Monoclonal antibodies have also shown promise (9) as radiopharmaceutical vectors due to their exquisite affinity and specificity, but their long biological residence times (≥ 3 d) require care to avoid high radiation doses to healthy tissues, especially in the context of RPT.

Shifting gears to the other major component, radionuclides that emit positrons and photons can be employed for PET and SPECT, while isotopes that emit α particles, β− particles, or Auger electrons are suited for RPT. Pairing the targeting molecule with the right radionuclide (and vice versa) is critical.(10) In nuclear imaging, it is generally held that the physical half-life of the radionuclide should align with the biological residence time of the targeting molecule. For example, rapidly clearing peptides and small molecules should be labelled with short-lived nuclides (e.g. 68Ga), while proteins that are excreted more slowly should be labelled with long-lived nuclides (e.g. 89Zr).(11) For therapy, selecting the appropriate radionuclide for a targeting vector requires the careful evaluation of the radiation doses delivered to both the target and healthy tissues through systemic dosimetry. Indeed, each type of therapeutic emission has a different linear energy transfer (LET) profile, and thus the ultimate cellular fate of the targeting molecule (i.e., extracellular, intracellular, or intranuclear) is an important consideration when selecting a radionuclide for RPT. Finally, as we will see, some radionuclides produce both therapeutic and diagnostic emissions, facilitating the creation of radiotheranostics that allow for simultaneous imaging and treatment with the same radiopharmaceutical.

Scientific Developments

The Supply of Radionuclides

After more than seven decades of clinical use, 131I-iodide remains the most widely used therapeutic radionuclide(12) in the clinic due to its exceptional biological targeting properties for thyroid diseases like hyperthyroidism and differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Advantageous emission and dosimetry properties have also led to the use of 123I and 124I for imaging patients prior to treatment with 131I. In addition, there are at least 60 ongoing clinical trials of131I-labelled radiopharmaceuticals for imaging and therapy across the globe(13). Most of the worldwide demand for 131I focuses on its [131I]NaI form, a trend that is likely to continue. Over the last few years, disruptions in reactor performance(14) and supply chain issues (especially during the COVID-19 pandemic) have emerged as challenges in the global market for 131I(15, 16); nevertheless, theranostic clinics will continue to rely on clinical procedures with 131I-labelled radiopharmaceuticals, generating an urgent need for solutions to the ongoing reactor issues that threaten the supply stability of 131I (and other radionuclides). In addition, clinicians continue to use [99mTc]Tc-MDP to identify patients with osteoblastic bone metastases suitable for treatment with approved treatments such as [89Sr]Sr Cl2 and [153Sm]Sm-EDTMP.

In recent years, the advent of RPT in the clinic and the increasing use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals labelled with isotopic pairs have led to surges in the demand for both established radionuclides and newer isotopes. With respect to RPT, the past decade has witnessed the regulatory approval of a range of radiopharmaceuticals labelled with several different therapeutic radionuclides (Table 1). Notably, radiopharmaceuticals labelled with 90Y and 177Lu — including 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 90Y-glass microspheres (TheraSphere™) for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE (Lutathera®) for the treatment of somatostatin receptor-expressing neuroendocrine tumors, and [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto®) for prostate cancer therapy — have been approved in multiple countries and used widely for in the clinic. The production and availability of these therapeutic isotopes and radiopharmaceuticals vary between countries, but significant efforts are underway to secure reliable commercial supply chains.(12)

Table 1.

Radiopharmaceuticals Approved for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

| Agent | Approval (FDA, EMA) |

Companion diagnostic(s) | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| [131I]Nal | 1971 | [131I]Nal | Differentiated thyroid carcinoma |

| [131I]I-tositumomabb | 2003, 2003 | [131I]I-tositumomabb | CD20+ R/R low-grade, follicular, or transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) following disease progression during or after rituximab. |

| 131I-chTNT | 2007d | - | Advanced lung cancer |

| [131I]iobenguane (or MIBG) | 2018 | [123I]iobenguane | NEN+ pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas2 |

| [177Lu]-Lu-DOTA-TATE | 2018, 2017 | [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE (USA); [64Cu]Cu-DOTA-TATE (USA); [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC (EU and USA) | SSTR-positive gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours |

| [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 | 2022 | [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 (FDA approved in 2021 and 2022) | Metastatic CRPC following disease progression on AR inhibitors and taxane-based chemotherapy |

| [223Ra]RaCl2 | 2013, 2013 | 99mTc-bone scan | CRPC with symptomatic bone metastases and no known visceral metastases. |

| 188Re-resin | 2020e | Non-melanoma skin cancer | |

| [153Sm]Sm-EDTMP | 1997, 1998 | 99mTc-bone scan | Palliation of bone pain in patients with multiple painful skeletal metastases |

| [89Sr]SrCl2 | 1993, 1986 | 99mTc-bone scan | Palliation of bone pain in patients with painful skeletal metastases |

| [90Y]Y-ibritumomab tiuxetana | 2002, 2004 | [111In]In-ibritumomab | Relapsed and/or refractory (R/R), low-grade or follicular B-cell NHL; Previously untreated follicular NHL who achieve a partial or complete response to first-line chemotherapy. |

| 90Y-microspheresc | 2002, 2002 | 99mTc-hepatic artery shunt scan | Unresectable metastatic liver tumours from primary colorectal cancer with adjuvant intra-hepatic artery chemotherapy of FUDR (Floxuridine). |

| 90Y-Glass microspheresc | 2021 | 99mTc-hepatic artery shunt scan | Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma |

Discontinued in the USA in 2021

Approval withdrawn and discontinued in 2014.

Administered via hepatic artery.

Approved by the Chinese FDA.

Approved by TGA. CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; NEn, norepinephrine transporter; DOTATATE, DOTA0,Tyr3-octreotate; EDTMP, ethylenediamine tetra(methylene phosphonic acid; MIBG, meta-iodobenzylguanidine; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; AR, androgen receptor.

One source of increased demand for new radionuclides has been the rise of RPT with α-emitting radionuclides.(5, 6, 17). The higher LET of α particles (relative to β particles) leads to more ionization events along the particle track. As a result, α particles cause a greater fraction of double strand breaks per track length than β particles, resulting in greater biological effectiveness.(18) Indeed, molecules labelled with α-emitting radionuclides have shown significant promise as radiotherapeutics in patients who have not responded to previous therapy with β-particle-based RPT.(19) In this context, 225Ac (t1/2 ~10 d) has emerged as a particularly important radionuclide. Its decay chain to stable 209Bi results in the release of 4 different α particles, a phenomenon that increases its therapeutic efficacy as long as these particles can be constrained to the tumour site (but complicates both dosimetry calculations and quality control measures). Several 225Ac-labelled radiotherapeutics are currently in clinical trials, as are several other agents labelled with shorter-lived α-emitting radionuclides like 213Bi (t1/2 ~46 min) and 211At (t1/2 ~7.2 h). In light of this surge, the field urgently needs to secure a reliable supply chain of α-emitting radionuclides to realize the full clinical potential of these tools.(20) Traditionally, 225Ac is derived from the decay of 229Th, which itself is obtained from the decay of 233U. Alternatively, researchers are also investigating accelerator-based methods predicated on the proton irradiation of 232Th as an avenue for increasing the global production capacity of 225Ac. One concern with this strategy, however, is the co-production of the undesirable byproduct 227Ac (with a half-life of 21.8 years). Furthermore, while challenges exist for the use of electron accelerators or medium energy cyclotrons for the production of 225Ac (e.g. the availability and handling of 226Ra target material and the relative scarcity of such equipment), we are nonetheless encouraged by the work being done in this area and recommend the continued funding of these efforts until a stable supply of 225Ac is guaranteed.(21)

The rise in the clinical use of PET and SPECT agents for theranostic imaging has also created pressure to increase the production of radionuclides (Table 2). Both 68Ga and 18F are increasingly paired with 177Lu to create theranostic radiopharmaceutical pairs for imaging and therapy. Perhaps most famously, [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE (NETSPOT™)/[68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC (SOMAKIT™) and [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE (LUTATHERA®) have been effectively deployed for the theranostic imaging and RPT of patients with neuroendocrine tumours that overexpress somatostatin receptors (SSTRs). The use of imaging with the 68Ga-labelled tracer to confirm the presence of the target and thus identify patients likely to respond the corresponding 177Lu-labelled agent has succeeded in several settings, paving the way for the incorporation of radiotheranostics into mainstream patient care. However, the mismatched half-lives and physicochemical properties of 68Ga and 177Lu can lead to radiopharmaceuticals with different binding affinities and biodistributions, making accurate dosimetry calculations difficult at best.(22) Differences in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behaviour of vectors when they are labelled with radionuclides of different elements has spurred research into the use of radiotheranostics bearing true elementally matched radionuclides (i.e. isotopologues) or, at the very least, radionuclides with closer chemical properties. The accurate prediction of radiation doses to tumour lesions and healthy tissues becomes especially important in the context of high-dose therapy or RPT with α-emitting radiotherapeutics. Examples of radioisotope pairs that can be used for imaging and therapy include 64Cu (for PET) and 67Cu (for β-RPT), 43Sc (for PET) and 47Sc (for β-RPT), and 203Pb (for PET) and 212Pb (for α-RPT), as well as a variety of radioisotopes of terbium (152Tb, 155Tb, 161Tb and 149Tb).(23) 89Zr has also been used to identify targets in tumors suitable for treatment with 177Lu-antibodies. [24]

Table 2.

Selected radionuclides in (or close to) clinical use for nuclear imaging and radiopharmaceutical therapy.

| Nuclide | Application | Half-life (t½) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | |||

| 61Cu | PET | 3.3 h | Paired with 67Cu |

| 18F | PET | 109.8 m | Routinely available |

| 68Ga | PET | 67.7 m | Paired with 177Lu |

| 124I | PET | 4.2 d | Paired with 131I |

| 123I | SPECT | 8.0 d | Paired with 131I |

| 43Sc | PET | 3.89 h | Paired with 47Sc |

| 44gSc | PET | 3.97 h | Paired with 47Sc |

| 203Pb | SPECT | 51.9 h | Paired with 212Pb |

| 152Tb | PET | 17.5 h | Can be paired with 161Tb |

| 99mTc | SPECT | 6.01 h | Paired with 153Sm, 186Re and 188Re, 89Sr |

| 86Y | PET | 14.7 h | Paired with 90Y |

| 89Zr | PET | 78.4 h | Readily available |

| Imaging and Radiopharmaceutical Therapy | |||

| 64Cu | PET, β therapy | 12.7 h | Readily available |

| 67Cu | β therapy, SPECT | 61.8 h | Availability limited |

| 67Ga | SPECT, Auger therapy | 3.3 d | Readily available |

| 123I | SPECT, Auger therapy | 13.2 h | Readily available |

| 131I | β therapy, SPECT | 8.0 d | Readily available |

| 111In | SPECT, Auger therapy | 2.8 d | Readily available |

| 177Lu | β therapy, SPECT | 6.7 d | Paired with 68Ga; Readily available |

| 186Re | β therapy, SPECT | 3.7 d | Availability limited |

| 188Re | β therapy, SPECT | 17.0 h | Availability limited |

| 47Sc | β therapy, SPECT | 3.4 d | Availability limited |

| 153Sm | β therapy, SPECT | 46.3 h | Readily available |

| 117mSn | SPECT, Auger therapy | 13.6 d | Limited availability |

| 161Tb | β therapy, SPECT | 6.9 d | Paired with 152Tb and 68Ga |

| Radiopharmaceutical Therapy | |||

| 225Ac | α therapy | 9.9 d | Availability limited |

| 211At | α therapy | 7.2 h | Availability limited |

| 213Bi | α therapy | 45.6 min | Availability limited |

| 212Pb/212Bi | α/β therapy | 10.6 h/60 min | Availability limited |

| 223Ra | α therapy | 11.4 d | Readily available |

| 227Th | α therapy | 18.7 d | Availability limited |

| 90Y | β -therapy | 64.1 h | Paired with 86Y |

PET, Positron Emission Tomography; SPECT, Single-photon emission computed tomography; d, days; h, hours

Methods of Radioisotope Production

As we have discussed, the increased demand for emerging radionuclides has inspired and generated a great deal of research into improving the efficiency of production methods (see, for example, our discussion of 225Ac above). However, demand is not the only impetus for the development of new approaches to radionuclide production. Indeed, several recent challenges — like the 2008 disruption to the 99Mo supply chain caused by the shutdown of major reactors as well as interruptions in the supply of enriched materials(24) — have spurred investigations into alternative routes for the production of both new and established radionuclides. For instance, the use of electron beams for the production of radionuclides (e.g., 99Mo, 47Sc, 67Cu, and 225Ac) via the photonuclear route has shown promise by successfully generating clinical-grade doses in some cases, but the technology needs further improvement before its widespread adoption.(25) In another example, nuclear reactors (used in many countries to produce long-lived radionuclides (e.g. 60Co)) are currently being investigated for the production of short-lived radionuclides, providing the field with a potential new radionuclide source. Additionally, advances in accelerators and targetry for charged-particle reactions with energetic protons, deuterons, and α particles continue to expand the availability of both diagnostic and therapeutic radionuclides. For example, advances in the production of 211At using a cyclotron (26, 27) and the creation of production networks through cross-site collaborations may expand access to this short-lived alpha-emitter. Along the same lines, while the cyclotron-based production of 225Ac is under investigation, the handling of long-lived radioactive target material remains a significant challenge.(28)

Many isotope production routes require the use of stable, isotopically enriched material. The availability of existing separated isotopes and the relative lack of suitable isotope separation facilities worldwide may limit the development of some of these otherwise feasible isotope production routes.

Chelators

The rise of new radiometals for nuclear imaging and therapy has necessitated the creation of new chelators that can provide stable coordination architectures for these isotopes. This is an active area of research that has been the topic of a number of recent reviews.(29-31) In essence, each radiometal has an optimal chelator (or chelators) that, when attached to a vector, will provide a kinetically and thermodynamically inert environment for the nuclide during the radiopharmaceutical’s transit throughout the body. The design and synthesis of new radiometal chelators, however, requires intensive efforts in design, synthesis, and testing. As a result, groups will often turn to well-known and frequently deployed chelators such as DOTA or NOTA, even if they are not ideal. DOTA, for example, was designed to sequester Gd in MRI contrast agents and has been shown to complex both Ga and Lu efficiently and stably. Yet while DOTA has shown suitability in some agents labelled with radiocopper (e.g. [64Cu]Cu-DOTA-TATE), several other studies have shown that it provides a suboptimal coordination environment for Cu2+, which may lead to the inadvertent release of the radiometal in vivo. The need for better chelators for radiocopper has led to the exploration of other coordination scaffolds, including cross-bridged tetra-azamacrocycles and sarcophagines. Emerging radionuclides like 225Ac and 212Pb do form reasonably stable complexes with DOTA; however, the development of more specific and stable chelators for each radiometal remains an area of important research. In the end, regardless of the specific radiometal or chelator, the underlying tenet is clear: when designing a radiopharmaceutical, careful preclinical and clinical research is needed to ensure that the chelator is an appropriate match for the radiometal.

Expanded Uses for Radiopharmaceuticals

Earlier-Line and Earlier-Stage Disease

While RPT has gained a great deal of clinical momentum in recent years, it has generally been deployed as a late-line palliative treatment. This status quo is now changing, with ongoing investigations into somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2)- and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted RPT in the setting of earlier-line and earlier-stage disease. For example, [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE (LUTATHERA®) recently demonstrated statistically significant and clinically meaningful progression-free survival in first-line advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NCT03972488). Similarly, 177Lu-labeled PSMA-targeted small molecules are now being tested in men with chemo-naïve metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (NCT04647526; NCT04689828; NCT04419402), metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (NCT04720157), oligometastatic or biochemically recurrent prostate cancer (NCT04443062; NCT05496959; NCT05079698), and locoregionally advanced or high-risk prostate cancer (NCT04430192; NCT05162573).

More Disease Indications

Clinical trials are also exploring the use of established RPT agents for new disease indications (see Table 3). For example, [177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE is being investigated in patients with many other SSTR-positive diseases, including breast cancer (NCT04529044), meningioma (NCT03971461), pheochromocytoma (NCT04711135), and paraganglioma (NCT03206060). Xofigo (Ra-223 dichloride) is under investigation for other cancers with bone metastases, including non-small cell lung cancer (NCT02283749), renal cell carcinoma (NCT04071223), and breast cancer (NCT02366130, NCT02258451). In addition, [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-l&T and [177Lu]Lu-EB-PSMA-617 are under investigation for PSMA-positive adenoid cystic salivary carcinoma (NCT04801264; NCT04291300). Given the discovery that PSMA is expressed in many different cancers beyond prostate, it is expected that new applications of PSMA-targeting theranostics will continue to emerge (32).

Table 3.

Examples of radiopharmaceuticals currently in clinical trials in cancer patients

| Nuclide | Therapeutic (Trade Name/Scientific Name) |

Target | Tumour Type | Industrial Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine tumours | ||||

| 177Lu | Satoreotide (OPS201, JR11) | STTR2 | NENs | Ipsen/Satosea |

| 177Lu | Edotreotide (DOTATOC, ITM-11) | SSTR2 | NENs | ITM |

| 177Lu | Lutathera (DOTA-TATE) | SSTR2 | GEP-NETs, SCLC, GBM | Novartis (Advanced Accelerator Applications) |

| 177Lu | DOTA-LM3 | SSTR2 | NENs | (42) |

| 212Pb | AlphaMedix (DOTAM-TATE) | SSTR2 | NENs | Radiomedix |

| 225Ac | DOTATOC | SSTR2 | NENs | (93) |

| 225Ac | DOTATATE | SSTR2 | NENs | (94) |

| 225Ac | DOTA-LM3 | SSTR2 | NENs | (43) |

| Prostate Cancer | ||||

| 225Ac | RYZ101 | SSTR2 | GEP-NETs | Rayzebio |

| 177Lu | TLX591 (Rosopatamab) | PSMA | mCRPC | Telix Pharmaceuticals |

| 177Lu | PNT2002 (PSMA I&T) | PSMA | mCRPC | POINT Biopharma Lantheus |

| 177Lu | PSMA I&T | PSMA | mCRPC | Curium US LLC |

| 177Lu | PSMA-617 | PSMA | mCRPC, mHSPC | Novartis |

| Other Cancers | ||||

| 225Ac | Actimab-A (Lintuzumab) | CD33 | AML | Actinium Pharmaceuticals |

| 225Ac | FPI-1434 | IGF-1R | Solid tumours | Fusion Pharmaceuticals |

| 225Ac | FPI-1966 | FGFR3 | Solid tumours | Fusion Pharmaceuticals |

| 131I | TLX101 (Iodophenylalanine) | LAT-1 | GBM | Telix Pharmaceuticals |

| 131I | HER2-VHH | HER2 | breast | VU Brussels, Belgium |

| 131I | Iomab-B (Apamistamab) | CD45 | AML | Actinium Pharmaceuticals |

| 131I, 177Lu | Omburtamab | B7-H3 | NB, MB | Y-mabs Therapeutics |

| 177Lu | TLX250 (Girentuximab) | CA9 | ccRCC | Telix Pharmaceuticals |

| 177Lu | Betalutin (Lilotomab) | CD37 | NHL | Nordic Nanovector |

| 177Lu | FAP-2286 | FAP | Solid tumours | Novartis |

| 177Lu | PNT6555 | FAP | Solid tumours | POINT Biopharma |

| 177Lu | Hurlutin | αvβ3 | Breast | Advanced Imaging Projects |

| 177Lu | NeoB | GRPR | Solid tumours | Advanced Accelerator Applications |

| 177Lu | DOTA-FAPI | FAP | various | Xiamen University, China |

| 177Lu | EB-FAPI | FAP | various | Peking Union Medical College Hospital and Xiamen University, China |

| 177Lu | PP-F11N | CCK-2R | thyroid | University Hospitals Basel, Freiburg, Zurich, Bern and PSI Villigen, Switzerland, Germany |

STTR2, somatostatin receptor 2; PSMA, prostate specific membrane antigen; FAP, fibroblast activation protein; NENs, neuroendocrine tumours; GEP-NETs, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours; FGFR3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; GRPR, gastrin-releasing peptide receptor; SCLC, small cell lung carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; mCRPC, metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer; mHSPC, metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer; NHL, non-Hodgkins lymphoma; NB, neuroblastoma; MB, medulloblastoma; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma. HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; CCK-2R, Cholecystokinin-2 receptor

Combining RPT with Immunotherapy and Other Therapies

Strategies predicated on the combination of RPT with immunotherapies are being widely explored in clinical and preclinical research.(23) Mechanistic evaluations of the effects of radiation on immunotherapy suggest numerous benefits, including the improved release of neoantigens, heightened pro-inflammatory effects, and the suppression of immunosuppressive cell populations within the tumour microenvironment. Clinically, external beam radiotherapy can sometimes lead to the induction of systemic anti-tumour immune responses and the generation of anti-tumour T cells.(33, 34) It is of great interest whether systemic β− or α-emitters can have similar effects. Thus, multiple active clinical trials are exploring immune checkpoint therapy in combination with RPT, including [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (NCT03805594), [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE (NCT04525638), and 223Ra (NCT02814669; NCT03996473).

Clinical trials are also underway exploring other combination strategies that may enhance the efficacy of radiotherapeutics or offer synergistic effects. For example, several trials combine RPT with DNA repair pathway inhibitors such as PARP inhibitors (NCT03317392; NCT04375267). Other groups are exploring methods to upregulate target expression. Along these lines, redifferentiation therapy has been used in thyroid cancer patients refractory to radioiodine therapy.(23) Investigations combining RPT with chemotherapy agents have been limited, but this approach is certainly also feasible and is likely to have increasing importance as RPT is incorporated into the treatment of earlier stage disease.(35)(36)

Combination Therapies with α- and β-Labelled Radiotherapeutics

The FDA approval of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE and [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 — both 177Lu-based β-RPTs — has been transformative for patients with neuroendocrine tumours and prostate cancer, respectively. Nonetheless, not all patients respond to RPT monotherapy. One key parameter in predicting response to 177Lu-based RPT is the number of DNA strand breaks created by the radiotherapeutic. Because α particles have a higher LET than β particles, α-emitting radiopharmaceuticals can create a greater number of complex cytotoxic double-strand DNA breaks, potentially endowing them with greater therapeutic efficacy. Indeed, recent reports suggest that α-RPT has a more potent antitumour response than β-RPT and that its use should be expanded.(37) While still very preliminary, remarkable results have been achieved in advanced clinical trials by switching patients unresponsive to 177Lu-based RPT to treatment with 225Ac-labelled radiopharmaceuticals.(38) Clinical trials should be encouraged to confirm and validate these results. However, it is important to note that α-RPT also carries a significant risk of toxicity, including dose-limiting xerostomia in the case of [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617. Recent approaches to balancing efficacy and toxicity include the use of a tailored mixture of 177Lu- and 225Ac-labelled radiopharmaceuticals. In fact, early preliminary reports investigating this approach in a small number of patients indicate that combination treatments may be feasible, safe, and effective and may also benefit from synergistic effects between the two radionuclides.(39)

A Wider Array of Targets for RPT

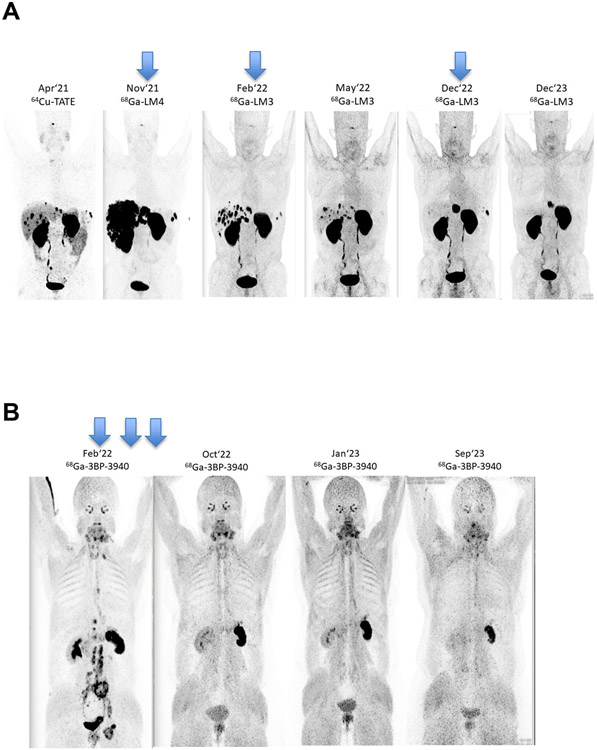

In recent years, the field of RPT has shifted toward radiotherapeutics labelled with 177Lu, including agents developed for the treatment of lymphoma and hepatic cancer as well as SSTR-targeting agents for neuroendocrine tumours such as [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE. These tools are expertly discussed in recent reviews by Bodei, et al. and Sgouros, et al.(40, 41) Along these lines, novel SSTR antagonist-based peptide receptor radionuclide therapies (PRRTs) (e.g. [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-LM3 and [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-LM3) are also gaining traction.(42) α-RPT using 225Ac-labelled SSTR agonists and antagonists(43) has shown favourable biodistribution and higher tumour radiation doses than SSTR agonists alone and may lead to improved outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), as may the addition of imaging (e.g. with [68Ga]Ga-LM3 and [68Ga]Ga-LM4(44) (Figure 2A; unpublished data). Another very important recent development in RPT has been the advent of PSMA-targeting radiopharmaceuticals that address the urgent need for better approaches to the treatment of prostate cancer. There are several entrants into this field, but [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto™) is the frontrunner and was approved by the United States FDA in March 2022. Critically, the PSMA- and SSTR2-targeted radiotherapeutics serve as excellent examples of the clinical utility of combining imaging (e.g. with [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 [FDA-approved] or [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE) and therapy (e.g. with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 or [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE) in a radiotheranostic approach to improve patient care via patient selection and treatment monitoring.

Figure 2A:

[18F]FDG-PET scans of a 60-year-old male diagnosed in April 2014 with pancreatic NEN (Ki67 52%) who underwent Whipple surgery, CAPTEM chemo, liver resection, and 4 cycles Lutathera in 2020. Upon recurrence in late 2021, further disease progression was observed despite numerous other treatments. Nearly complete hepatic remission was observed after PRRT with [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-LM3 (timing of doses shown with blue arrows) and has persisted for 2 years.

Figure 2B: [18F]FDG-PET scans of a 53-year-old patient diagnosed in 2010 with ovarian adenocarcinoma G3 who underwent surgery and chemotherapy. After recurrence in 2021, progressive disease was observed despite various chemo- and immunotherapies. Complete remission was achieved after tandem [177Lu]Lu/[225Ac]Ac-3BP-3940 treatment (timing of doses shown with blue arrows) and is ongoing after 19 months.

In the wake of the encouraging clinical results obtained with SSTR2- and PSMA-targeting radiopharmaceuticals, new targets continue to arise. For a summary of the targets currently being explored in the clinic as well as their corresponding radiopharmaceuticals, see Table 3. An even wider range of tumour cell- and microenvironment-specific targets are currently being interrogated in preclinical research. An exciting emerging target for RPT is fibroblast activation protein (FAP). FAP inhibitors (FAPIs) were first described in 2014 by Jansen and colleagues at the University of Antwerp.(45) Diagnostic (and possibly therapeutic) radiopharmaceuticals based on radiolabelled low-molecular-weight FAPIs were first presented in 2018 by Haberkorn et al.(46) Later research produced encouraging clinical results for these quinoline-based inhibitors labelled with theranostic radionuclides.(47) One of the agents in particular — [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 — showed rapid tumour uptake and has subsequently been investigated in clinical trials for multiple tumour types.(48-50)

The pioneering work of Osterkamp, Zboralski and others(51) led to the development of several 177Lu-labelled FAP-targeted peptides and peptidomimetics that are currently in clinical use for different types of cancer.(52) First-in-human results on the compassionate use of [177Lu]Lu-FAP-2286 have been obtained by Baum et al.(52) Recently, promising results have been shown for a theranostic approach using [68Ga]Ga-3BP-3940 for PET/CT-based patient selection for FAP-targeted RPT with 177Lu, 90Y, 225Ac, and combinations of these radionuclides (Figure 2B; unpublished), especially in combination with immunotherapeutics (e.g. anti-VEGF antibodies like bevacizumab) or radiosensitising chemotherapeutics (e.g. doxorubicin or irinotecan). These results have created excitement for FAP-targeted radiotherapeutics, which could potentially fill a gap in current clinical practice and can be applied in several indications.(42) Beyond FAP, a diverse set of other exciting tumour-specific antigens are currently being evaluated as targets for RPT, including neurotensin, B7-H3, CXCR4, and carbonic anhydrase 9 (CAIX).(53-57)

Different Administration Routes

Radiopharmaceuticals are typically administered intravenously, although some approved radionuclide therapies are given topically or via intra-arterial injection (Table 1). Once either a PET or SPECT scan — increasingly acquired using a companion radiotheranostic — has confirmed a patient’s suitability for RPT, a dosing plan for the radiotherapeutic must be implemented. Given the importance of delivering an appropriate therapeutic dose to the tumour while sparing normal tissue, such planning should consider the radiotherapeutic’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.(58) Along these lines, both radiotherapeutics and their companion imaging agents may benefit from state-of-the-art drug delivery systems.(59) For example, ongoing studies are investigating the potential advantages of intra-arterial (hepatic artery) vs. intravenous administration of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE in patients with NET liver metastases.(60) In these studies, intra-arterial [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE was shown to be safe but did not lead to a clinically significant increase in tumour uptake. That said, the results suggest that the intra-arterial administration of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE results in higher activity concentrations and higher absorbed doses in the hepatic metastases of patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours compared to standard intravenous doses.(61) While further clinical testing with other agents is needed, these preliminary reports suggest that intra-arterial administration may improve the efficacy of radiotherapeutics, a phenomenon that has also been seen with nanomedicines, chemotherapeutics, and 90Y-microspheres (Table 1) (62, 63). In humans, RPT via the local delivery of [213Bi]Bi/[225Ac]Ac-DOTA-substance P for gliomas has produced promising, prolonged survival parameters.(64, 65)

The Advent of Computational Methods

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms is expected to impact many aspects of nuclear medicine, from the discovery, development, and distribution of radiopharmaceuticals to the acquisition, reconstruction, and analysis of images.(66) AI is also expected to improve nuclear medicine image analysis in multiple areas, including the detection of lesions and dosimetry.(67-69) Indeed, AI techniques are already being used to standardize the quantification of PSMA PET/CT images and have already garnered FDA approval.(70) PYLARIFY AI™, for example, is an FDA-approved medical device that enables standardized quantitation and reporting of PSMA PET/CT images.

While AI will not replace nuclear medicine physicians or medical physicists, its use in clinical practice could reduce the burdens of image analysis (thereby freeing up time for other tasks and reducing misinterpretations) and improve accuracy (thereby reducing inter-observer variability). In the coming years, as the use of AI becomes more widespread, trustworthiness and reliability will be key. Reproducibility, generalizability, and ethics also represent valid concerns that must be addressed. As such, the use of AI in nuclear medicine should follow the best practices defined for the field (66) as well as concepts like current Good Machine Learning Practice (cGMLP), for which regulatory agencies like the FDA are already developing guiding principles.(71) Developers must ensure that algorithms earn the trust of healthcare adopters and patients alike.

Leveraging Imaging and Dosimetry Techniques for Theranostics

The emergence of more sensitive PET scanners — in particular, whole-body scanners (e.g. the UExplorer Total Body PET scannerTM and the Biograph Vision QuadraTM) — means that both short- and long-lived PET radionuclides can be imaged for longer periods of time, thereby enhancing biodistribution and dosimetry studies. In addition, advances in quantitative and digital SPECT(72) have enabled the use of true elemental matched pairs of radiopharmaceuticals for imaging and therapy in cases where no suitable positron-emitting nuclide exists. These two advanced imaging techniques may prove especially useful during the early phases of the development of imaging radiotherapeutics, when they can inform structural modifications that may improve pharmacokinetic behaviour or help determine dosing strategies by facilitating serial quantitative imaging at multiple time points to produce time-integrated activity curves.

Advances in SPECT imaging and dosimetry also provide the opportunity for personalized dosimetry-guided RPT. With these techniques, clinical trials may more safely and rigorously investigate dose escalation or re-treatment. In the landmark DOSISPHERE trial, personalized dosimetry with dose escalation of 90Y-microspheres resulted in improved objective response rates for patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.(73) Current trials are investigating dosimetry-guided [177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE in adults (NCT02754297) and children (NCT03923257).

Molecular Imaging the Response to Immunotherapy

Theranostic imaging can be combined with immunotherapy to predict both response and early resistance. For example, the visualisation of PD-L1 expression via PET using 89Zr-labelled atezolizumab correlated better with clinical responses to treatment with atezolizumab than immunohistochemistry or RNA-sequencing-based predictive biomarkers.(69)

Therapeutic effects can also be driven by changes in and modifications of the tumour microenvironment, providing an additional diagnostic and therapeutic opportunity. While methods exist for delineating specific T cell populations (CD8+, CD4+) in ex vivo tumour tissue, novel imaging approaches to image T cell populations in vivo have also been developed.(74) Furthermore, opportunities to use nuclear imaging to determine the impact of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) on the immune suppressive microenvironment using radiolabelled fibroblast activation protein inhibitors (FAPI) have been reported.(47) Tumor-associated macrophages — which are known to suppress the immune response — represent another target for the imaging of immunotherapy; to wit, imaging CD206-expressing TAMs was shown in a preclinical study to predict tumour relapse in breast cancer.(75)

Operational Considerations

The Production and Availability of Radionuclides

Radionuclides are considered the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) of approved radiopharmaceutical products. Radionuclides are primarily produced using research reactors (fission and neutron activation), cyclotrons, and electron accelerators, as well as through the decay of other (parent) radionuclides. Worldwide, around 60 research reactors are currently active in the production of radionuclides according to the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) research reactor database.(76) Of these, 8–10 constitute the major worldwide producers of medical radionuclides. (Table 4). On top of this, the increasing demand for positron-emitting radionuclides has led to a global surge in the installation and operation of cyclotrons. According to the IAEA database on “cyclotrons used for radioisotope production”,(77) around 1200 cyclotrons have been installed around the globe, and at least 800 of these routinely produce medical radionuclides for PET and SPECT. The majority of these cyclotrons are used for the routine production of 18F for [18F]FDG and (increasingly) for 18F-labelled PSMA-targeting probes. In response to the growth of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging, the number of cyclotrons installed around the world is increasing, thanks in large part to versatile designs that make it easier to construct cyclotrons with different sizes, energies, and targetry systems.

Table 4.

Global nuclear reactors supplying medical radionuclides (95)

a h/d/w = operating schedule expressed as hours per day / days per week / weeks per year

| Reactor | Location | Power (MW) | Schedule(h/d/wa) | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BR2 | Belgium | 10 | 24/7/21 | 61 |

| FRM-II | Germany | 20 | 24/7/34 | 18 |

| HFIR | USA | 85 | 24/7/24 | 57 |

| HFR | Netherlands | 45 | 24/7/44 | 45 |

| LVR-15 | Czechia | 10 | 24/7/30 | 65 |

| MARIA | Poland | 30 | 24/5/40 | 48 |

| MURR | USA | 10 | 24/6.5/52 | 56 |

| OPAL | Australia | 20 | 24/7/52 | 16 |

| SAFARI | South Africa | 20 | 24/7/44 | 57 |

Recent years have witnessed explosive growth in nuclear medicine due to the regulatory approval of several new diagnostic agents and the emergence of theranostics for the imaging and RPT of neuroendocrine tumours and prostate cancer.(78) For many PET centres, this growth has been a double-edged sword, burdening legacy cyclotron, radiochemical, and scanner infrastructure that had primarily been built and optimised for [18F]FDG patient volumes. The broad spectrum of newly approved PET radiopharmaceuticals has left some facilities unable to manufacture each radiopharmaceutical every day, complicating patient care.(79) PET/CT and PET/MRI scanners at many sites are also nearing capacity. While demand has been managed since the approval of new PET agents began in earnest following the introduction of regulatory mechanisms,(80) this has mostly been due to the limited utilisation of tools like amyloid- and tau- targeted tracers and a lack of therapeutic options that could be informed by PET scans (i.e. no need for theranostics). However, the recent approval of aducanumab and lecanemab as well as the number of other Alzheimer’s therapeutics in advanced clinical trials (e.g. donanemab) could also lead to an increase in the demand for amyloid- and tau-targeted PET(81) at the same time as demand surges for PSMA-targeted PET(82). This could stress the existing PET infrastructure to potentially critical levels. Relief will be difficult, given the high cost and long lead times associated with expanding and/or building new PET centres. Because funding, planning, and building such centres is complex and can take a number of years,(83, 84) it is urgent that planning for such expansions begin immediately for academic medical centres, commercial nuclear pharmacy networks, and standalone imaging centres.

At the same time, demand for therapeutic radionuclides is higher than ever. The regulatory approval of Lutathera™ ([177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE) and Pluvicto™ ([177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617) has created significant demand for 177Lu, which is severely testing the limits of current supply chain and reactor infrastructure.(85) The plethora of novel 177Lu-labelled radiopharmaceuticals in advanced clinical trials suggests that the demand for 177Lu could soon surge again, further straining supply. The production of 177Lu is predicated on the irradiation of isotopically enriched 176Lu (or 176Yb) targets with reactor neutrons and the subsequent processing of the irradiated target material. Relying on ageing reactor infrastructure to meet and even increase production is expected to be problematic (Table 4). As the construction of new reactors is difficult, expensive, time-consuming, and politically delicate, we recommend the field engage scientific and political leadership around the world now to prepare the critical radionuclide supplies needed for nuclear medicine’s future. A recent report from the European Union overviews the supply chain for therapeutic radionuclides.(86)

The Production of Radiopharmaceuticals

Both local and centralised methods are used for the production of diagnostic and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals.(87, 88) Generally speaking, the choice between the two depends on a number of factors, including the source of the radionuclide, the physical half-life of the radionuclide, the availability of synthetic kits, and the local regulations governing pharmacy and manufacturing.

In the context of local production, the widespread availability of 99Mo/99mTc generators has fuelled the creation of a wide variety of kits for the synthesis of 99mTc-labelled radiopharmaceuticals.(89) As a result, local compounding — the combination of two or more drugs, in this case 99mTc and the kit — for SPECT remains common. Similarly, in light of the short half-life of many positron-emitting radionuclides, the local production of PET imaging agents like [18F]FDG as well as 68Ga- and 18F-labelled SSTR- and PSMA-targeting radiopharmaceuticals remains the norm at academic medical centres and commercial nuclear pharmacy networks. In the future, local production and compounding may also become the norm for the next generation of radiotherapeutics labelled with short-lived radionuclides like 212Pb.

As we have discussed, the use of radiopharmaceuticals bearing longer-lived radionuclides — e.g. 64Cu and 89Zr for PET, 177Lu for β-RPT, and 225Ac for α-RPT — has surged in recent years. In these cases, centralised production is more sensible, as limited infrastructure exists for the production of these radionuclides, and their half-lives are amenable to transport. For example, [64Cu]Cu-DOTA-TATE is manufactured and distributed from a centralised location, as are 177Lu-labelled radiotherapeutics.

Another consideration in the production of radiopharmaceuticals is the use of synthesis modules and single-use kits. In the context of PET, the traditional production paradigm involves the use of synthesis modules and is considered drug manufacture. However, approved radiopharmaceuticals labelled with radiometals like 68Ga and 64Cu are often amenable to kit production (as is used for 99mTc-labelling). In some regulatory environments, the use of kits with radiometals such as these no longer meets the definition of either ‘drug manufacture’ or ‘compounding’ (in the U.S., for example, 68Ge/68Ga generators, unlike 99Mo/99mTc generators, are not approved drugs). Instead, this sort of production qualifies as “drug preparation” according to an approved package insert. Clearly, in the years to come, the field will need to carefully keep abreast of the ways in which the ever-changing regulatory environment will impact the production of radiopharmaceuticals.

Generic Radiotherapeutics

While many novel imaging agents (e.g. Pylarify™, Amyvid™, Tauvid™, Neuraceq™, Vizamyl™) are marketed as new drugs and protected by patents, established agents like [18F]FDG, [13N]ammonia, and [18F]sodium fluoride have no patent protection and are thus marketed as generic drugs. To date, only a small number of approved radiotherapeutics — i.e., Bexxar™, Zevalin™, Xofigo™, Lutathera™, PSMA-I&T, and Pluvicto™ — have been marketed by pharmaceutical companies, while others, like low molar activity [131I]MIBG and 131I-sodium iodide, have no patent protection. However, imaging and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals remain patent-protected only for a limited time. Notably, protection for [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE is set to expire in 2025.(90) As a result, opportunities will soon arise for companies and academic medical centres to create generic theranostics ([177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE and others later). To capitalise on this, a number of start-up companies and academic medical centres are already building labs dedicated to the cGMP manufacture of radiotherapeutics. We expect this trend to continue.

Reimbursement

Reimbursement policies for nuclear imaging agents and radiotherapeutics are of critical importance as our field continues to grow.(91) While reimbursement rules vary from country to country and depend upon local healthcare policy, the field needs to be responsive to global challenges to ensure that our high-value products are available to the patients who will benefit from them.

While a survey of radiopharmaceutical access and reimbursement issues around the world is beyond the scope of this overview, the topic was recently reviewed in detail.(12) In many countries, the cost of a diagnostic radiopharmaceutical is “bundled” with the cost of the imaging procedure in the outpatient setting. In the United States, for example, a significant challenge with this approach is that Medicare’s ‘bundled’ rates are the same for an established agent such as [18F]FDG as they are for a novel, patent-protected agent such as [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE. This is the case even when the cost of the new diagnostic is higher than the entire bundled reimbursement for the imaging procedure! Unfortunately, issues like this can usually not be fixed at the local level but rather require unified efforts from the field to petition governments for changes in healthcare policy. The nuclear medicine community in the United States has been highly active in championing the Facilitating Innovative Nuclear Diagnostics (FIND) Act, which directs the Department of Health and Human Services to pay separately for all diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals with a cost threshold of $500 per day. It is hoped that this will gain congressional approval in the near future.(92)

Another important reimbursement issue is the cost of dosimetry calculations, which, while rarely standard today, are likely to become more frequently used in order to optimise the delivery of radiopharmaceuticals. In the context of external beam radiotherapy, dosimetry is routinely paid for, and planning systems are well-developed. However, this is not presently true for most dosimetry in service of RPT. That said, additional planning systems are in development, and several new companies are delving into this radiopharmaceutical dosimetry space. Ultimately, the development of appropriate reimbursement rates for dosimetry will prove important for the future of RPT.

Moving Forward

The unprecedented growth in nuclear medicine and the radiopharmaceutical sciences over the last decade has been fuelled by the emergence of several exciting new radiopharmaceutical therapies. The clinical approval of these drugs for the treatment of patients with NETs and prostate cancer has been pivotal in establishing radiotheranostics as major tools in oncology. However, ensuring access and availability on a global scale will be challenging and will require a scale-up of both production capacity and the number of sites suitable for the delivery of these treatments to patients. This expansion will require training the scientists and clinicians necessary to deploy novel theranostics in the clinic (for more on this, see our companion piece on the challenges faced by the nuclear medicine workforce in the age of radiotheranostics). In order to take full advantage of the potential of theranostics for improving patient care, a coordinated effort will be needed that links academia, industry, government agencies, and intergovernmental bodies. In this context, we propose the following approaches to enhance the development of radiopharmaceuticals for oncology:

On the scientific side, we believe the field could benefit from…

support for the development of novel, efficient, and reliable production methodologies for both established and emerging radionuclides;

the development of widely accessible online databases on the availability of medical radionuclides;

an increase in international and interdisciplinary collaborations focused on both the production of radionuclides and the synthesis of radiopharmaceuticals;

an emphasis on clinical trials focused on radiotherapeutics as first-line therapies or as part of combination therapies, particularly alongside immunotherapeutics;

an expansion in the number of clinical trials focused on the use of companion theranostic imaging agents, particularly to facilitate individualised dosimetry and the selection of patients;

-

the development of new chelation architectures suitable for emergent metallic radionuclides.

On the operational side, we believe the field could benefit from…

support for the dramatic expansion of radionuclide production facilities to meet the rising preclinical and clinical demand for both established and new radionuclides, particularly α-emitters, Auger-electron-emitters, and radionuclide pairs that can be used to create isotopologous theranostics;

the simplification and modernization of reimbursement protocols to adequately cover novel radiopharmaceuticals;

enhanced collaborations to establish interdisciplinary theranostics centres to address the growing number of patients that need RPT as well as follow-up assessment after treatment.

Ultimately, we have no doubt that the difficulties of overcoming the challenges associated with our field’s rapid expansion will be worth it. We are eager to see where our field goes in the next few years and are extraordinarily excited about what it could mean for our patients.

Summary

This paper is one of a series summarizing the current landscape of the radiopharmaceutical sciences as they pertain to oncology. In this article, we describe exciting developments in radiochemistry and the production of radionuclides, the development and translation of theranostics, and the application of artificial intelligence to our field. These developments are catalysing growth in the use of radiopharmaceuticals to the benefit of patients the world over. We also highlight some of the key issues to be addressed in the coming years in order to realize the full potential of radiopharmaceuticals in the fight against cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Mr. Garon Scott for his help in editing this manuscript.

Funding:

SEL is supported by the Department of Energy as part of the DOE University Isotope Network under grant DESC0021269. PJHS is supported by NIH R01 EB021155. AMS is supported by NHMRC grant No. 1177837. JSL is supported by NIH R35 CA232130.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

Outside the submitted work: SEL reports research support from Navidea Biopharmaceuticals, Fusion Pharmaceuticals, Cytosite Biopharma Inc., Viewpoint Molecular Targeting, Inc, and Genzyme Corporation and has acted as an advisor for NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes and Trevarx biomedical; PJHS reports research support from BMS, Telix Pharmaceuticals and Radionetics Oncology, has acted as an adviser to Synfast Consulting LLC and Telix Pharmaceuticals, and holds equity in BMS, Telix Pharmaceuticals and Novartis; AMS reports trial funding from EMD Serono, ITM, Telix Pharmaceuticals, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Fusion Pharmaceuticals, and Cyclotek; research funding from Medimmune, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Adalta, Antengene, Humanigen, Telix Pharmaceuticals and Theramyc; and advisory boards of Imagion and ImmunOs, outside the submitted work; ADW reports his role as the Editor-in-Chief on Nuclear Medicine and Biology; BMZ holds equity in Summit Biomedical Imaging; MAW reports no relevant conflicts; RPB is an advisor to 3B Pharmaceuticals, Berlin, Germany, ITM, Full Life Technologies, Sinotau, Jiangsu Huayi Technology, and Telix Pharmaceuticals; JMB reports no relevant conflicts; FG reports no relevant conflicts; APK reports clinical trial funding from Novartis, Bayer, POINT, and Merck; unpaid consulting for Novartis; AJ reports no relevant conflicts; PK reports no relevant conflicts; AK reports no relevant conflicts; JK reports an unrestricted grant from Janssen, consulting fees from Telix and Novartis. STL reports no relevant conflicts; DP reports no relevant conflicts; JLU reports no relevant conflicts; JZ reports no relevant conflicts; JSL reports research support from Clarity Pharmaceuticals, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals has acted as an adviser of Boxer, Clarity Pharmaceuticals, Curie Therapeutics Inc, Earli Inc, Evergreen Theragnostics, NexTech Invest, Telix Pharmaceuticals, Suba Therapeutics Inc, and TPG Capital, is a co-inventor on technologies licensed to Diaprost, Elucida Oncology, Theragnostics, Ltd., CheMatech and Samus Therapeutics LLC, and is the co-founder of pHLIP Inc., and holds equity in Curie Therapeutics Inc, Summit Biomedical Imaging, Telix Pharmaceuticals and Evergreen Theragnostics.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria: A systematic search of published literature was conducted using PubMed (with no date range), MEDLINE (with no date range) and ClinicalTrials.gov using such search terms as “radiopharmaceutical therapy”, “radiopharmaceutical”, “radiotheranostics” and “theranostics”.

Contributor Information

Suzanne E. Lapi, Departments of Radiology and Chemistry, O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Peter J. H. Scott, Department of Radiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Andrew M. Scott, Department of Molecular Imaging and Therapy, Austin Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Olivia Newton-John Cancer Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; School of Cancer Medicine, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Faculty of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Albert D. Windhorst, Department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Cancer Center Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Brian M. Zeglis, Department of Chemistry, Hunter College, City University of New York, New York, New York USA; Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA; Department of Radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA.

May Abdel-Wahab, Division of Human Health, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Richard P. Baum, DKD Helios Klinik Wiesbaden, CURANOSTICUM MVZ Wiesbaden-Frankfurt, Center for Advanced Radiomolecular Precision Oncology, Wiesbaden, Germany.

John M. Buatti, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City IA, USA.

Francesco Giammarile, Centre Leon Bérard, Lyon, France. Nuclear Medicine and Diagnostic Imaging Section, Division of Human Health, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Ana P. Kiess, Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore MD, USA.

Amirreza Jalilian, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Peter Knoll, Division of Human Health, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria..

Aruna Korde, Division of Physical and Chemical Sciences, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria..

Jolanta Kunikowska, Nuclear Medicine Department, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland..

Sze Ting Lee, Department of Molecular Imaging and Therapy, Austin Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Olivia Newton-John Cancer Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; School of Cancer Medicine, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Faculty of Medicine and Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Diana Paez, Nuclear Medicine and Diagnostic Imaging Section, Division of Human Health, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Jean-Luc Urbain, Department of Radiology/Nuclear Medicine, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York, USA.

Jingjing Zhang, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, National University of Singapore, Singapore; Clinical Imaging Research Centre, Nanomedicine Translational Research Program, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Jason S. Lewis, Department of Radiology and Program in Molecular Pharmacology, Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, New York, USA; Departments of Radiology and Pharmacology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York USA.

References

- 1.Strosberg J et al. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N Engl J Med 376, 125–135, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sartor O, d. BJ, Chi KN, Fizazi K, Herrmann K, Rahbar K, Tagawa ST, Nordquist LT, Vaishampayan N, El-Haddad G, Park CH, Beer TM, Armour A, Pérez-Contreras WJ, DeSilvio M, Kpamegan E, Gericke G, Messmann RA, Morris MJ, Krause BJ, VISION Investigators. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med Sep 16, 1091–1103, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107322 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofman MS et al. [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 397, 797–804, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00237-3 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miederer M Alpha emitting nuclides in nuclear medicine theranostics. Nuklearmedizin. 2022. Jun;61(3):273–279. English. doi: 10.1055/a-1650-9995. Epub 2022 Oct 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poty S, Francesconi LC, McDevitt MR, Morris MJ & Lewis JS Alpha-Emitters for Radiotherapy: From Basic Radiochemistry to Clinical Studies-Part 1. J Nucl Med 59, 878–884, doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.186338 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poty S, Francesconi LC, McDevitt MR, Morris MJ, Lewis JS. α-Emitters for Radiotherapy: From Basic Radiochemistry to Clinical Studies-Part 2. J Nucl Med. 2018. Jul;59(7):1020–1027. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.204651. Epub 2018 Mar 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgna F, Haller S, Rodriguez JMM, Ginj M, Grundler PV, Zeevaart JR, Köster U, Schibli R, van der Meulen NP, Müller C. Combination of terbium-161 with somatostatin receptor antagonists-a potential paradigm shift for the treatment of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022. Mar;49(4):1113–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05564-0. Epub 2021 Oct 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitneni SK, Koumarianou E, Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. Observations on the Effects of Residualization and Dehalogenation on the Utility of N-Succinimidyl Ester Acylation Agents for Radioiodination of the Internalizing Antibody Trastuzumab. Molecules. 2019. Oct 30;24(21):3907. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin M, Paolillo V, Le DB, Macapinlac H, Ravizzini GC. Monoclonal antibody based radiopharmaceuticals for imaging and therapy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2021. Oct;45(5):100796. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2021.100796. Epub 2021 Oct 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter LM, Poty S, Sharma SK, Lewis JS. Preclinical optimization of antibody-based radiopharmaceuticals for cancer imaging and radionuclide therapy-Model, vector, and radionuclide selection. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2018. Jul;61(9):611–635. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3612. Epub 2018 Mar 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satapathy S MB, Sood A, Sood A, Kapoor R, Gupta R, Khosla D. 177Lu-DOTATATE Plus Radiosensitizing Capecitabine Versus Octreotide Long-Acting Release as First-Line Systemic Therapy in Advanced Grade 1 or 2 Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Single-Institution Experience. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;Jul:1167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler CS, Bailey E, Kumar V, Schwarz SW, Bom HS, Hatazawa J, Paez D, Orellana P, Louw L, Mut F, Kato H, Chiti A, Frangos S, Fahey F, Dillehay G, Oh SJ, Lee DS, Lee ST, Nunez-Miller R, Bandhopadhyaya G, Pradhan PK, Scott AM. Global Issues of Radiopharmaceutical Access and Availability: A Nuclear Medicine Global Initiative Project. J Nucl Med. 2021. Mar;62(3):422–430. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.247197. Epub 2020 Jul 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clincal Trials. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/.

- 14.Committee on State of Molybdenum-99 Production and Utilization and Progress Toward Eliminating Use of Highly Enriched Uranium; Nuclear and Radiation Studies Board; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Molybdenum-99 for Medical Imaging. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016. Oct 28. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396169/ doi: 10.17226/23563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giammarile F, Delgado Bolton RC, El-Haj N, Freudenberg LS, Herrmann K, Mikhail M, Morozova O, Orellana P, Pellet O, Estrada LE, Vinjamuri S, Gnanasegaran G, Pynda Y, Navarro-Marulanda MC, Choudhury PS, Paez D. Changes in the global impact of COVID-19 on nuclear medicine departments during 2020: an international follow-up survey. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021. Dec;48(13):4318–4330. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05444-7. Epub 2021 Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giammarile F, Delgado Bolton RC, El-Haj N, Mikhail M, Morozova O, Orellana P, Pellet O, Estrada Lobato E, Pynda Y, Paez D. Impact of COVID-19 on Nuclear Medicine Departments in Africa and Latin America. Semin Nucl Med. 2022. Jan;52(1):31–40. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2021.06.018. Epub 2021 Jun 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strosberg JR, Herrmann K, Bodei L. The Future of Targeted Alpha Therapy is Bright but Rigorous Studies are Necessary to Advance the Field. J Nucl Med. 2022. Oct 20:jnumed.122.264805. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.122.264805. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graf F, Fahrer J, Maus S, Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Venkatachalam S, Fottner C, Weber MM, Huelsenbeck J, Schreckenberger M, Kaina B, Miederer M. DNA double strand breaks as predictor of efficacy of the alpha-particle emitter Ac-225 and the electron emitter Lu-177 for somatostatin receptor targeted radiotherapy. PLoS One. 2014. Feb 7;9(2):e88239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sathekge M BF, Knoesen O, Reyneke F, Lawal I, Lengana T, Davis C, Mahapane J, Corbett C, Vorster M, Morgenstern A. 225Ac-PSMA-617 in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced prostate cancer: a pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019. Jan;46:129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson BJBAJ, Wuest F. Targeted Alpha Therapy: Progress in Radionuclide Production, Radiochemistry, and Applications. Pharmaceutics. 2020. Dec 31;13(49). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Isotope Development Center. Multiple Production Methods Underway to Provide Actinium-225. https://www.isotopes.gov/information/actinium-225 [

- 22.Fani M BF, Waser B, Beetschen K, Cescato R, Erchegyi J, Rivier JE, Weber WA, Maecke HR, Reubi JC. Unexpected sensitivity of sst2 antagonists to N-terminal radiometal modifications. J Nucl Med. 2012;Sep(9):1481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodei L HK, Schöder H, Scott AM, Lewis JS. Radiotheranostics in oncology: current challenges and emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022. Epub ahead of print;June 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadvar H, Chen X, Cai W & Mahmood U Radiotheranostics in Cancer Diagnosis and Management. Radiology 286, 388–400, doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170346 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starovoitova V, Tchelidze L, Wells DP, Production of medical radioisotopes with linear accelerators. Applied Radiation and Isotopes: Including Data, Instrumentation and Methods for Use in Agriculture, Industry and Medicine 85C:39–44, 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.11.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntosh LA, Burns JD, Tereshatov EE, Muzzioli R, Hagel K, Jinadu NA, McCann LA, Picayo GA, Pisaneschi F, Piwnica-Worms D, Schultz SJ, Tabacaru GC, Abbott A, Green B, Hankins T, Hannaman A, Harvey B, Lofton K, Rider R, Sorensen M, Tabacaru A, Tobin Z, Yennello SJ. Production, isolation, and shipment of clinically relevant quantities of astatine-211: A simple and efficient approach to increasing supply. Nucl Med Biol. 2023. Nov-Dec;126-127:108387. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2023.108387. Epub 2023 Sep 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CA19114 - Network for Optimized Astatine labeled Radiopharmaceuticals (NOAR) [Internet]. Brussels: COST Association; March 2020. Available from: https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA19114/. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhiman D, Vatsa R, Sood A. Challenges and opportunities in developing Actinium-225 radiopharmaceuticals. Nucl Med Commun. 2022. Sep 1;43(9):970–977. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001594. Epub 2022 Jun 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price EW, Orvig C. Matching chelators to radiometals for radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev. 2014. Jan 7;43(1):260–90. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60304k. Epub 2013 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu A, Wilson JJ. Advancing Chelation Strategies for Large Metal Ions for Nuclear Medicine Applications. Acc Chem Res. 2022. Mar 15;55(6):904–915. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00003. Epub 2022 Mar 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowden GD, Scott PJH, Boros E. Radiochemistry: A Hot Field with Opportunities for Cool Chemistry. ACS Central Science. 2023;9(12):2183–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauri C, Chiurchioni L, Russo VM, Zannini L, Signore A. PSMA Expression in Solid Tumors beyond the Prostate Gland: Ready for Theranostic Applications? J Clin Med. 2022. Nov 7;11(21):6590. doi: 10.3390/jcm11216590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME RI, Leaman O, López-Campos F, Montero A, Conde AJ, Aristu JJ, Lara P, Calvo FM, Melero I. Immune mechanisms mediating abscopal effects in radioimmunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther Apr. 2019. Apr(195–203). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tubin S KM, Salerno G, Mourad WF, Yan W, Jeremic B. Mono-institutional phase 2 study of innovative Stereotactic Body RadioTherapy targeting PArtial Tumor HYpoxic (SBRT-PATHY) clonogenic cells in unresectable bulky non-small cell lung cancer: profound non-targeted effects by sparing peri-tumoral immune microenvironment. Radiat Oncol. 2019;Nov(14(1)):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbertson RA, T. N, Lee FT, Gill S, Chappell B, Cavicchiolo T, Saunder T, O'Keefe GJ, Poon A, Lee ST, Murphy R, Hopkins W, Scott FE, Scott AM. Targeted chemoradiation in metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase I trial of 131I-huA33 with concurrent capecitabine. J Nucl Med APr, 534–539, doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.132761 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fathpour G, Jafari E, Hashemi A, Dadgar H, Shahriari M, Zareifar S, Jenabzade AR, Vali R, Ahmadzadehfar H, Assadi M. Feasibility and Therapeutic Potential of Combined Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy With Intensive Chemotherapy for Pediatric Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Metastatic Neuroblastoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2021. Jul 1;46(7):540–548. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcu L BE, Allen BJ. Global comparison of targeted alpha vs targeted beta therapy for cancer: In vitro, in vivo and clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;Mar:7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sathekge MM BF, Vorster M, Morgenstern A, Lawal IO. Global experience with PSMA-based alpha therapy in prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;Dec(1):30–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langbein T, Kulkarni HR, Schuchardt C, Mueller D, Volk GF, Baum RP. Salivary Gland Toxicity of PSMA-Targeted Radioligand Therapy with 177Lu-PSMA and Combined 225Ac- and 177Lu-Labeled PSMA Ligands (TANDEM-PRLT) in Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Single-Center Systematic Investigation. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022. Aug 10;12(8):1926. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12081926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodei L, Pepe G, Paganelli G. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) of neuroendocrine tumors with somatostatin analogues. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010. Apr;14(4):347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sgouros G, Bodei L, McDevitt MR & Nedrow JR Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: clinical advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19, 589–608, doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0073-9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baum RP, Zhang J, Schuchardt C, Müller D, Mäcke H. First-in-Humans Study of the SSTR Antagonist 177Lu-DOTA-LM3 for Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Dosimetry, Safety, and Efficacy. J Nucl Med. 2021. Nov;62(11):1571–1581. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.258889. Epub 2021 Mar 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi M, Jakobsson V, Greifenstein L, Khong P-L, Chen X, Baum RP and Zhang J (2022) Alpha-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using actinium-225 labeled somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists. Front. Med 9:1034315. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1034315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greifenstein L, Kramer CS, Moon ES, Rösch F, Klega A, Landvogt C, Müller C, Baum RP. From Automated Synthesis to In Vivo Application in Multiple Types of Cancer-Clinical Results with [68Ga]Ga-DATA5m.SA.FAPi. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022. Aug 14;15(8):1000. doi: 10.3390/ph15081000. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansen K, De Winter H, Heirbaut L, Cheng JD, Joossens J, Lambeir A-M, De Meester I, Augustyns K, Van der Veken P Selective inhibitors of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) with a xanthine scaffold. MedChemComm. 2014;5:1700–1707. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00167B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loktev A, Lindner T, Mier W, Debus J, Altmann A, Jäger D, Giesel F, Kratochwil C, Barthe P, Roumestand C, Haberkorn U. A Tumor-Imaging Method Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. J Nucl Med. 2018. Sep;59(9):1423–1429. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.210435. Epub 2018 Apr 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giesel FL KC, Lindner T, Marschalek MM, Loktev A, Lehnert W, Debus J, Jäger D, Flechsig P, Altmann A, Mier W, Haberkorn U. (68)Ga-FAPI PET/CT: biodistribution and preliminary dosimetry estimate of 2 DOTA-containing FAP-targeting. J Nucl Med. 2019;Mar(3):386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Róhrich M, Naumann P, Giesel FL, Choyke PL, Staudinger F, Wefers A, Liew DP, Kratochwil C, Rathke H, Liermann J, Herfarth K, Jäger D, Debus J, Haberkorn U, Lang M, Koerber SA. Impact of 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT Imaging on the Therapeutic Management of Primary and Recurrent Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas. J Nucl Med. 2021. Jun 1;62(6):779–786. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.253062. Epub 2020 Oct 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koerber SA, Staudinger F, Kratochwil C, Adeberg S, Haefner MF, Ungerechts G, Rathke H, Winter E, Lindner T, Syed M, Bhatti IA, Herfarth K, Choyke PL, Jaeger D, Haberkorn U, Debus J, Giesel FL. The Role of 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT for Patients with Malignancies of the Lower Gastrointestinal Tract: First Clinical Experience. J Nucl Med. 2020. Sep;61(9):1331–1336. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.237016. Epub 2020 Feb 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giesel FL, Heussel CP, Lindner T, Röhrich M, Rathke H, Kauczor HU, Debus J, Haberkorn U, Kratochwil C. FAPI-PET/CT improves staging in a lung cancer patient with cerebral metastasis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019. Jul;46(8):1754–1755. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04346-z. Epub 2019 May 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zboralski D, Hoehne A, Bredenbeck A, Schumann A, Nguyen M, Schneider E, Ungewiss J, Paschke M, Haase C, von Hacht JL, Kwan T, Lin KK, Lenore J, Harding TC, Xiao J, Simmons AD, Mohan AM, Beindorff N, Reineke U, Smerling C, Osterkamp F. Preclinical evaluation of FAP-2286 for fibroblast activation protein targeted radionuclide imaging and therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022. Sep;49(11):3651–3667. doi: 10.1007/s00259-022-05842-5. Epub 2022 May 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baum RP, Schuchardt C, Singh A, Chantadisai M, Robiller FC, Zhang J, Mueller D, Eismant A, Almaguel F, Zboralski D, Osterkamp F, Hoehne A, Reineke U, Smerling C, Kulkarni HR. Feasibility, Biodistribution, and Preliminary Dosimetry in Peptide-Targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Diverse Adenocarcinomas Using 177Lu-FAP-2286: First-in-Humans Results. J Nucl Med. 2022. Mar;63(3):415–423. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.259192. Epub 2021 Jun 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]