Abstract

China has adhered to policies of zero-COVID for almost three years since the outbreak of COVID-19, which has remarkably affected the circulation of respiratory pathogens. However, China has begun to end the zero-COVID policies in late 2022. Here, we reported a resurgence of common respiratory viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae with unique epidemiological characteristics among children after ending the zero-COVID policy in Shanghai, China, 2023. Children hospitalized with acute respiratory tract infections were enrolled from January 2022 to December 2023. Nine common respiratory viruses and 2 atypical bacteria were detected in respiratory specimens from the enrolled patients using a multiplex PCR-based assay. The data were analyzed and compared between the periods before (2022) and after (2023) ending the zero-COVID policies. A total of 8550 patients were enrolled, including 6170 patients in 2023 and 2380 patients in 2022. Rhinovirus (14.2%) was the dominant pathogen in 2022, however, Mycoplasma pneumoniae (38.8%) was the dominant pathogen in 2023. Compared with 2022, the detection rates of pathogens were significantly increased in 2023 (72.9% vs. 41.8%, p < 0.001). An out‐of-season epidemic of respiratory syncytial virus was observed during the spring and summer of 2023. The median age of children infected with respiratory viruses in 2023 was significantly greater than that in 2022. Besides, mixed infections were more frequent in 2023 (23.8% vs. 28.9%, p < 0.001). China is now facing multiple respiratory pathogen epidemics with changing seasonality, altered age distribution, and increasing mixed infection rates among children in 2023. Our finding highlights the need for public health interventions to prepare for the respiratory pathogen outbreaks in the post-COVID-19 era.

Keywords: COVID-19, NPIs, Children, Respiratory pathogens, Prevalence

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Viral epidemiology

Background

To control the COVID-19 pandemic, China has adhered to policies of zero-COVID for almost three years with strictly enforced lockdowns and other aggressive restrictive measures such as social distancing, mask wearing, and case isolation since the outbreak of COVID-19 in late 20191. The implementation of these nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) effectively cut off the respiratory transmission chain, which also resulted in a substantial reduction in the circulation of other common respiratory viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic2–5. However, many viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus (PIV), human coronavirus (HCoV), rhinovirus (RV) and human bocavirus (HBoV) resurged after NPIs were relaxed, and schools reopened during September 2020–January 2021, which raised concerns for a more significant rise in respiratory viruses when the COVID-19-related NPIs eventually lifted6,7.

Given the attenuated pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants and increasing vaccination coverage, China has begun to end the zero-COVID policies, notably by announcing the 10 measures (e.g. people will not be subjected to nucleic acid testing) on 7 December 20228. After that, China experienced a nationwide outbreak of COVID-199,10. Besides, the abrupt changes in NPIs may also contribute to outbreaks of other respiratory pathogens. Here, we report a rebound of common respiratory viruses and MP with changing seasonality, altered age distribution, and increasing mixed infection rates among children in 2023 after ending the zero-COVID policy in Shanghai, China.

Methods

Study design

Children less than 18 years old with acute respiratory tract infection (ARTI) admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University and receiving etiological tests in the entire years 2023 (after ending the zero-COVID) and 2022 (during the zero-COVID) were enrolled to explore the prevalence of respiratory pathogens in children after ending the zero-COVID policy. A patient was considered to have an ARTI if at least two of the following clinical manifestations occurred during the week prior to them presenting: fever, cough, nasal obstruction, expectoration, sneezing, and dyspnea. The decision as to whether an etiological test was necessary was made by the attending physician. Demographics and clinical data from the enrolled children were obtained from their electronic medical records.

Specimen collection and testing

Respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal aspirates/bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) were obtained from all the enrolled children within 72 h of admission by trained staff following standard operating procedures. The specimens were immediately transferred to the clinical laboratory for the detection of respiratory pathogens.

Respiratory specimens were tested for HCoV, RSV, HBoV, RV, PIV, general influenza virus A (IAV), influenza virus A H1N1 (2009) (H1N1), seasonal influenza virus A H3N2 (H3N2), influenza virus B (IBV), human adenovirus (ADV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), Chlamydia (Ch), and MP by using the SureX 13 respiratory pathogen multiplex kit, a commercial multiplex PCR-based panel assay (Health Gene Technologies, Ningbo, China). Multiplex PCR products were separated and analyzed using an Applied Biosystems 3500 analyzer.

If any one of the targeted pathogens was detected in the specimens, the patient was considered positive for that pathogen. In cases where two or more pathogens were detected in the same clinical sample, the respective pathogens were counted individually.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables (detection rates, sex) are expressed as numbers (%). As the continuous variable (age) in our study was not normal distributed, it was expressed as median (interquartile range). For comparisons between the periods before (2022) and after (2023) ending the zero-COVID policy, the Chi-squared test was used for categorical data, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for numeric data. All of the tests were two-tailed, and a value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 26.0 software (IBM, New York, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 8550 patients were enrolled in the study, including 6170 patients in 2023 and 2380 patients in 2022. Nasopharyngeal aspirates were obtained from 7483 patients, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids were obtained from 1067 patients. The median age of patients in 2023 (3 years) was older than that in 2022 (0.5 years), and no significant differences in sex were observed between 2023 and 2022 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics and positive rates of respiratory pathogens between the year of 2023 (after ending the zero-COVID policy) and 2022 (before ending the zero-COVID policy).

| Total | 2022 | 2023 | p value# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Total patients | 8550 | 2380 | 6170 | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 4728 (55.3) | 1329 (55.8) | 3399 (55.1) | 0.531 |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 2 (0.17–6) | 0.5 (0.08–4) | 3 (0.5–7) | < 0.001 |

| Pathogen detection, n (%) | ||||

| MP | 2613 (30.6) | 222 (9.3) | 2391 (38.8) | < 0.001 |

| RV | 1469 (17.2) | 339 (14.2) | 1130 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| RSV | 805 (9.4) | 154 (6.5) | 651 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| PIV | 640 (7.5) | 153 (6.4) | 487 (7.9) | 0.021 |

| IAV | 573 (6.7) | 22 (0.9) | 551 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| H1N1 | 169 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 169 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| H3N2 | 404 (4.7) | 22 (0.9) | 382 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

| ADV | 376 (4.4) | 29 (1.2) | 347 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| HMPV | 343 (4.0) | 75 (3.2) | 268 (4.3) | 0.012 |

| HBoV | 257 (3.0) | 62 (2.6) | 195 (3.2) | 0.178 |

| HCoV | 218 (2.6) | 31 (1.3) | 187 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| IBV | 88 (1.0) | 49 (2.1) | 39 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| CP | 58 (0.7) | 39 (1.6) | 19 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Total | 5492 (64.2) | 996 (41.8) | 4496 (72.9) | < 0.001 |

| Mixed infection, n (%) | ||||

| Dual | 1335 (15.6) | 130 (5.5) | 1205 (19.5) | < 0.001 |

| Triple | 240 (2.8) | 20 (0.8) | 220 (3.6) | < 0.001 |

| Quadruple | 43 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 40 (0.6) | 0.002 |

| Quintuple | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Total | 1619 (18.9) | 153 (6.4) | 1466 (23.8) | < 0.001 |

#Comparison between the year of 2023 and 2022;

IQR, interquartile range; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; HCoV, human coronavirus; RV, rhinovirus; HBoV, human Boca virus; IAV, influenza virus A; H1N1, influenza virus A H1N1 (2009); H3N2, influenza virus A H3N2, IBV, influenza virus B; ADV, human adenovirus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Resurgence of respiratory pathogens

One or more respiratory pathogens were detected in 4496/6170 (72.9%) specimens in 2023, which was significantly greater than that in 2022 (996/2380, 41.8%) (Table 1). Among all pathogens, MP (30.6%) had the highest detection rate, followed by RV (17.2%) and RSV (9.4%). RV (14.2%) was the most commonly detected pathogen in 2022, however, MP (38.8%) was the most common pathogen in 2023. Compared with those in 2022, the detection rates of MP, RV, RSV, PIV, IAV, ADV, HMPV, and HCoV were significantly greater in 2023 (Table 1). However, the positive rates of IBV and CP were slightly lower in 2023 (Table 1). The positive rate of HBoV did not significantly differ between 2022 and 2023 (Table 1).

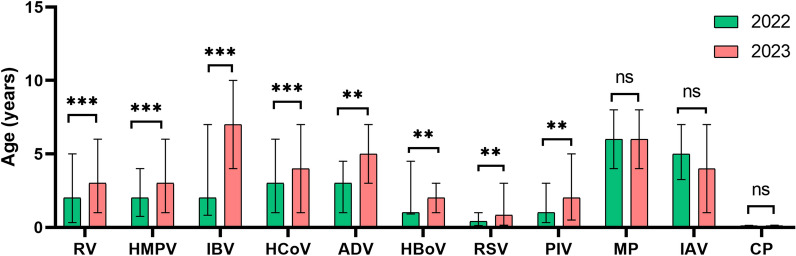

Altered age distribution

The age distribution of the children with virus infection between 2022 and 2023 varied. The median ages of children infected with RV, RSV, PIV, ADV, HMPV, HBoV, HCoV, and IBV in 2023 were significantly greater than those in 2022 (Fig. 1). It means that older children tend to be susceptible to these viruses in 2023.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of ages of children infected with respiratory pathogens between the year of 2022 and 2023. The columns indicate the medians and the whiskers represent the interquartile ranges. Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison. MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; IAV, influenza virus A; H1N1, influenza virus A H1N1 (2009); H3N2, influenza virus A H3N2; ADV, human adenovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; HCoV, human coronavirus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HBoV, human Boca virus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; IBV, influenza virus B; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

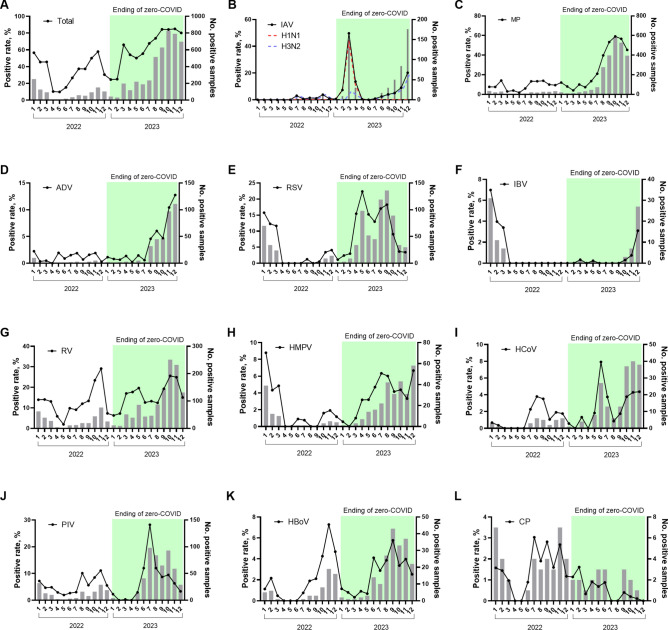

Changing seasonality

Except in January and February 2023, the total positive numbers and rates of pathogens in each month of 2023 were higher than the same period in 2022 (Fig. 2A). The alterations in seasonality differed among the pathogens. IAV, MP, and ADV activities were extremely low in 2022 (Fig. 2B, C, D). However, a large outbreak of IAV (H1N1) was first observed in March 2023, shortly after the end of the “zero-COVID” policy (Fig. 2B). After that, MP and ADV also resurged in August 2023 (Fig. 2CD). The detection rate of MP was nearly 60.0% in October 2023 (Fig. 2C). An out‐of-season epidemic of RSV was observed during the spring and summer (April to September) of 2023 (Fig. 2E). The prevalence of IBV was almost absent in 2023 and started to increase at the end of 2023 (Fig. 2F). The seasonality of RV, HMPV, HCoV, PIV and HBoV was not significantly changed in 2023 (Fig. 2G-K). The prevalence of CP did not show significant seasonality in either 2023 or 2022 (Fig. 2L).

Fig. 2.

Monthly respiratory pathogen detections among children with ARTI, Shanghai, China, 2022–2023. Black lines indicate the percentage of cases that were positive for each virus. Grey bars indicate the number of positive cases tested each month. IAV, influenza virus A; H1N1, influenza virus A H1N1 (2009); H3N2, influenza virus A H3N2; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; ADV, human adenovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; IBV, influenza virus B; RV, rhinovirus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HCoV, human coronavirus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; HBoV, human Boca virus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae;

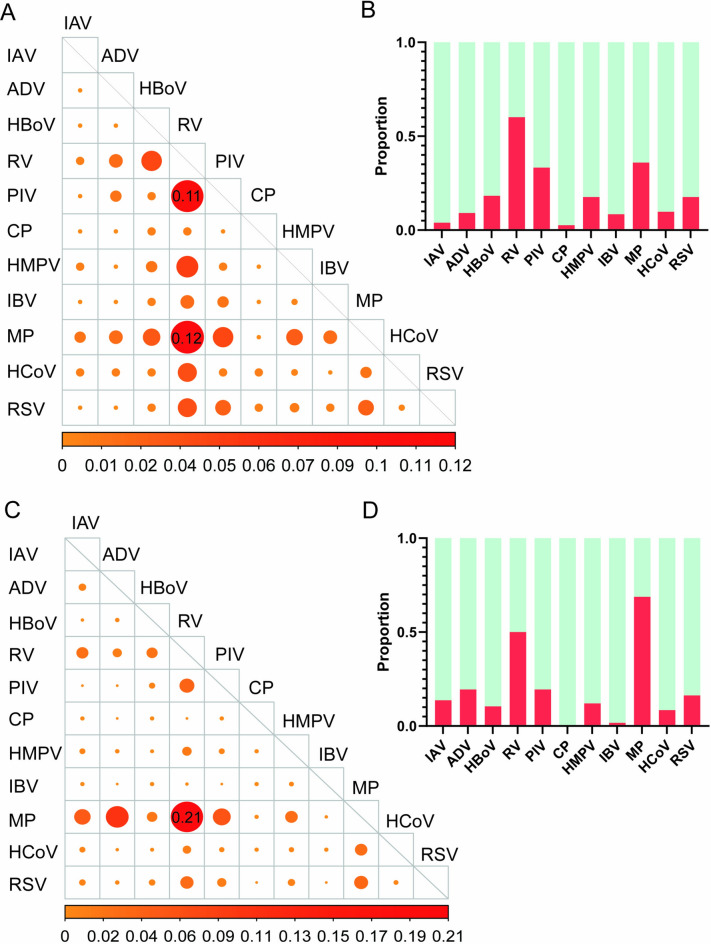

Increasing mixed infection

Among all the patients, 18.9% (1619/8550) had a mixed infection (at least two pathogens detected). Cases with mixed infections were more frequent in the year 2023 (23.8%, 1466/6170, p < 0.001) than in the year 2022 (6.4%, 153/2380) (Table 1). MP + RV was the most common mixed infection pattern in both 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 3AC). RV was the most frequently detected pathogen in mixed infection cases in 2022, followed by MP and PIV (Fig. 3B); however, MP became the top pathogen in mixed infection cases in 2023, followed by RV (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Mixed infection features of respiratory pathogens in the year of 2022 and 2023. (A) Mixed infection pattern of respiratory pathogens in 2022. (B) The proportion of each pathogen in the mixed infections in 2022. (C) Mixed infection pattern of respiratory pathogens in 2023. (D) The proportion of each pathogen in the mixed infections in 2022. The bigger size solid circles in the panel A/B represent the higher frequency of this two pathogens combination, calculated by the count of each dual infection combination/all dual infection combinations. MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; IAV, influenza virus A; H1N1, influenza virus A H1N1 (2009); H3N2, influenza virus A H3N2; ADV, human adenovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; HCoV, human coronavirus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HBoV, human Boca virus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; IBV, influenza virus B.

Discussion

The nationwide “zero-COVID” policy was implemented for approximately 3 years in China, which was longer and stricter than the policies of many other countries. After ending the “zero‐COVID” policy, China is now facing multiple respiratory pathogen epidemics. Our study reports the high prevalence of multiple respiratory pathogens, changing seasonality, altered age distribution, and increasing mixed infection rates among children in the first year after China fully exited the “Zero‐COVID” policy in 2023.

While NPIs limited the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they also reduced the spread of other pathogens during and after lockdown periods, despite the re-opening of schools2. This positive collateral effect in the short term is welcome as it prevents additional overload of the healthcare system. The lack of immune stimulation due to the reduced circulation of microbial agents and the related reduced vaccine uptake (such as the recommended influenza vaccines) induced an “immunity debt”, which could have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control and NPIs are lifted11. The longer these periods of “viral or bacterial low-exposure” are, the greater the likelihood of future epidemics. In our study, the number of children hospitalized with ARTI at the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University largely increased with the resurgence of common respiratory viruses and MP in the year 2023. The surge of respiratory viruses such as IAV, MP, RSV, PIV, and ADV in children was also reported from other parts of the world after the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions, such as Korea12, Japan13, Germany14, Qatar15, and the US16. These global epidemic trends were thought to be due in part to the reduced population-level immunity, antigenic drift, and children’s re-engagement in social activities17.

We found that the frequency of mixed infection in the year 2023 was significantly higher than in the year of 2022. Perhaps the prime reason is that the probability of being infected with multiple pathogens at the same time increases due to the increased prevalence of various pathogens. Besides, the “immunity debt” may also has played an important role. Mixed infections may contribute to more severe disease in children18. In the upcoming years, it will be important to continue to monitor ARTI outcomes among children, especially for these with mixed infections.

MP is a common cause of lower and upper respiratory tract infections, especially in children and young adults. Although many common respiratory pathogens have resurged during the COVID-19 pandemic, the activity of MP remained in a low prevalence state before the end of the “zero‐COVID” policy19. However, starting in late summer (August) 2023, we observed a rapid rise in MP detection, and many patients presented with coinfections of multiple pathogens. Up to now (June 2024), MP infections continue to occur at high rates based on our routine surveillance (data not shown). The current outbreak in late 2023 may be explained by the usual epidemic cycle of MP, which has shown outbreaks every 3–5 years20. However, it may also be related to host factors resulting from the COVID-19-related NPIs, which possibly led to a decline in population immunity, also known as “Immunity debt”21.

NPIs significantly impacted RSV seasonality. In temperate countries, RSV activities generally start from late autumn or early winter peak in winter, and end in late winter or spring22. However, there was an absent RSV winter season in Shanghai in 2022, followed by a subsequent out‐of-season spring/summer surge in 2023. The out‐of-season spikes in RSV activity during the COVID-19 pandemic were also observed in China23, France24, Iceland25, Israel26, and the US27 in spring/summer 2021, following the strict NPIs adopted in 2020. As the highly infectious Omicron variant rages in parts of China, strict and comprehensive NPIs were reimplemented between late February 2022 and the end of 2022 in Shanghai28. Similar to the out-of-season resurgence in 2021, the suppressed RSV circulation in the winter months of the 2022–2023 season was followed by a delayed RSV resurgence in spring/summer 2023. The RSV is not part of recommended vaccines or an expanded program of immunization for children in China, and this resurgence was more likely due to the accumulation of RSV-naïve population following a prolonged period of minimal RSV exposure in 2022.

Another interesting finding in our study is that the median age of children infected with respiratory viruses (except for IAV) after ending the “zero-COVID” policy was significantly greater than that in the prior period. The temporary shift in the age distribution of endemic viral infections may be due to the effects of delayed circulation and the resultant immunity gap, which makes the susceptible children be exposed for the first time at older ages29.

There are several limitations regarding the interpretation of our data. Firstly, the study is a single-center study in Shanghai, and the pattern might be different in other countries or in other regions of China. Secondly, we only analyzed data of hospitalized children, and the data in outpatients may be different. Thirdly, the COVID-19 pandemic might have substantially changed the healthcare-seeking behavior of patients with ARTI, which might lead to selection bias. Finally, common bacteria causing ARTI in children, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, were not included in our study.

Conclusion

Our study provides an overview of the distinct epidemiology of respiratory pathogens among children after ending the “zero-COVID” policy in Shanghai, including the atypical out-of-season circulations as well as the altered age profile of virus detection. The results highlight the need for health-care systems to prepare for the possibility of large outbreaks occurring out of season among older children in the post-COVID-19 era. Vaccines can be administered which can help to “repay” some of the immunity debt acquired over the past years. Future strategies such as strengthened implementation of routine childhood immunization programs, enhanced pathogen surveillance and improved health education are crucial.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- NPIs

Nonpharmaceutical interventions

- ARTI

Acute respiratory tract infection

- MP

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- CP

Chlamydia pneumoniae

- IAV

Influenza virus A

- H1N1

Influenza virus A H1N1 (2009)

- H3N2

Influenza virus A H3N2

- IBV

Influenza virus B

- ADV

Human adenovirus

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RV

Rhinovirus;

- HCoV

Human coronavirus

- PIV

Parainfluenza virus

- HMPV

Human metapneumovirus

- HBoV

Human Boca virus

Author contributions

PL and JX conceived and designed the study. MX, LL, XZ, RJ, ND, and LS performed the sampling. PL, MX, LL, and RJ analyzed the data. MX, XZ, ND, and LS conducted experiments. PL and JX prepared the manuscript draft and revised the manuscript. All authors provided comments on the manuscript and all authors accepted the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by the 3-Year Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health System in Shanghai (grant number: GWVI-11.2-YQ43), and the Key Development Program of Children’s Hospital of Fudan University (grant number: EK2022ZX05).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data belong to the hospital database but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval to conduct this study was granted by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University. This study was a retrospective study, and the use of anonymized information data for research complied with relevant regulations and ethical principles. Informed consent was waived by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pan, A. et al. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA323, 1915–1923 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu, P. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of respiratory viruses in children with lower respiratory tract infections in China. Virol. J.18, 159 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer, S. P. et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae detections before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a global survey 2017 to 2021. Euro Surveill.10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.19.2100746 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu, W. et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae detections in children with lower respiratory infection before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A large sample study in China from 2019 to 2022. BMC Infect. Dis.24, 549 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu, P. et al. The changing pattern of common respiratory and enteric viruses among outpatient children in Shanghai, China: Two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol.94, 4696–4703 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li, Z. J. et al. Broad impacts of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on acute respiratory infections in China: An observational study. Clin. Infect. Dis.75, e1054–e1062 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker, R. E. et al. Long-term benefits of nonpharmaceutical interventions for endemic infections are shaped by respiratory pathogen dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.119, e2086072177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xinhua. China Focus: COVID-19 response further optimized with 10 new measures (2022). https://english.news.cn/20221207/ca014c043bf24728b8dcbc0198565fdf/c.html.

- 9.Huang, J. et al. Infection rate in Guangzhou after easing the zero-COVID policy: Seroprevalence results to ORF8 antigen. Lancet Infect. Dis.23, 403–404 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang, J. et al. Infection rates of 70% of the population observed within 3 weeks after release of COVID-19 restrictions in Macao, China. J. Infect.86, 402–404 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen, R. et al. Pediatric infectious disease group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap?. Infect. Dis. Now.51, 418–423 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho, H. J. et al. Epidemiology of respiratory viruses in Korean children before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study from national surveillance system. J Korean Med. Sci.39, e171 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirotsu, Y. et al. Changes in viral dynamics following the legal relaxation of COVID-19 mitigation measures in Japan from children to Adults: A single center study, 2020–2023. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses18, e13278 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quarg, C., Jorres, R. A., Engelhardt, S., Alter, P. & Budweiser, S. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for infection with influenza, SARS-CoV-2 or respiratory syncytial virus in the season 2022/2023 in a large German primary care centre. Eur. J. Med. Res.28, 568 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abushahin, A. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and subsequent relaxation on the prevalence of respiratory virus hospitalizations in children. BMC Pediatr.24, 91 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furlow, B. Triple-demic overwhelms paediatric units in US hospitals. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health7, 86 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossum, E. et al. Antigenic drift and immunity gap explain reduction in protective responses against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of human sera collected in 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023. Virol. J.21, 57 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caporizzi, A. et al. Analysis of a cohort of 165 pediatric patients with human bocavirus infection and comparison between mono-infection and respiratory co-infections: A retrospective study. Pathogens13(1), 55 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urbieta, A. D. et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae at the rise not only in China: Rapid increase of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cases also in Spain. Emerg. Microbes Infect.13, 2332680 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omori, R., Nakata, Y., Tessmer, H. L., Suzuki, S. & Shibayama, K. The determinant of periodicity in mycoplasma pneumoniae incidence: An insight from mathematical modelling. Sci. Rep.5, 14473 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, T., Chu, C., Wei, B. & Lu, H. Immunity debt: Hospitals need to be prepared in advance for multiple respiratory diseases that tend to co-occur. Biosci. Trends17, 499–502 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan, S. et al. Global seasonal activities of respiratory syncytial virus before the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A systematic review. Open Forum Infect. Dis.11, e238 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, M. et al. Characterising the changes in RSV epidemiology in Beijing, China during 2015–2023: Results from a prospective, multi-centre, hospital-based surveillance and serology study. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac.45, 101050 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casalegno, J. S. et al. Characteristics of the delayed respiratory syncytial virus epidemic, 2020/2021, Rhone Loire, France. Euro Surveill.26(29), 2100630 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Summeren, J. et al. Low levels of respiratory syncytial virus activity in Europe during the 2020/21 season: What can we expect in the coming summer and autumn/winter?. Euro Surveill.26(29), 2100639 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberger, O. M. et al. Delayed respiratory syncytial virus epidemic in children after relaxation of COVID-19 physical distancing measures, Ashdod, Israel, 2021. Euro Surveill.26(29), 2100706 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamid, S. et al. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus—United States, 2017–2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep.72(14), 355–361 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, X., Zhang, W. & Chen, S. Shanghai’s life-saving efforts against the current omicron wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet399, 2011–2012 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messacar, K. et al. Preparing for uncertainty: Endemic paediatric viral illnesses after COVID-19 pandemic disruption. Lancet400, 1663–1665 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data belong to the hospital database but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.