SUMMARY

The genesis of skeletal muscle during embryonic development and postnatal life serves as a paradigm for stem and progenitor cell maintenance, lineage specification, and terminal differentiation. An elaborate interplay of extrinsic and intrinsic regulatory mechanisms controls myogenesis at all stages of development. Many aspects of adult myogenesis resemble or reiterate embryonic morphogenetic episodes, and related signaling mechanisms control the genetic networks that determine cell fate during these processes. An integrative view of all aspects of myogenesis is imperative for a comprehensive understanding of muscle formation. This article provides a holistic overview of the different stages and modes of myogenesis with an emphasis on the underlying signals, molecular switches, and genetic networks.

A myriad of regulatory inputs orchestrates myogenesis during embryonic development and in postnatal life. Many similarities between embryonic myogenesis and regeneration in mature skeletal muscle have been discovered.

1. INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is a highly complex and heterogeneous tissue serving a multitude of functions in the organism. The process of generating muscle—myogenesis—can be divided into several distinct phases (Tajbakhsh 2009). During embryonic myogenesis, mesoderm-derived structures generate the first muscle fibers of the body proper, and in subsequent waves additional fibers are generated along these template fibers (Parker et al. 2003; Sambasivan and Tajbakhsh 2007). In the poorly understood perinatal phase, muscle resident myogenic progenitors initially proliferate extensively but later on decrease as the number of myonuclei reaches a steady state and myofibrillar protein synthesis peaks (Schultz 1996; Davis and Fiorotto 2009). Once the muscle has matured, these progenitors will enter quiescence and henceforth reside within in it as satellite cells. Adult skeletal muscle, like all renewing organs, relies on a mechanism that compensates for the turnover of terminally differentiated cells to maintain tissue homeostasis (Schmalbruch and Lewis 2000; Pellettieri and Sanchez Alvarado 2007). This type of myogenesis depends on the activation of satellite cells that have the potential to differentiate into new fibers (Charge and Rudnicki 2004). The most comprehensively studied form of myogenesis takes place when mature muscle is damaged and large cohorts of satellite cells expand mitotically and differentiate to repair the tissue and reestablish homeostasis (Rudnicki et al. 2008). Many similarities, such as common transcription factors and signaling molecules, between embryonic myogenesis and regeneration in the mature skeletal musculature have been discovered (Tajbakhsh 2009). It is now generally accepted that satellite cells are closely related to progenitors of somitic origin (Gros et al. 2005; Relaix et al. 2005; Schienda et al. 2006; Hutcheson et al. 2009; Lepper and Fan 2010). How the uncommitted character, or the “stemness,” of the embryonic founder cells is retained in satellite cells remains a matter of ongoing investigation.

A broad spectrum of signaling molecules instructs myogenesis during embryonic development and in postnatal life (Kuang et al. 2008; Bentzinger et al. 2010). The activation of cell surface receptors by these signals induces intracellular pathways that ultimately converge on a battery of specific transcription and chromatin-remodeling factors. These factors translate the extracellular signals into the gene and microRNA expression program, which assigns myogenic identity to the muscle progenitors. Myogenic transcription factors are organized in hierarchical gene expression networks that are spatiotemporally induced or repressed during lineage progression. Cellular identity during development is further defined by intrinsic mechanisms such as the ability to self-renew and the capacity to prevent mitotic senescence or DNA damage (He et al. 2009). The extent of intrinsic and extrinsic contribution during lineage progression from the most ancestral cell to a differentiated muscle fiber will vary depending on the respective stage of cellular commitment but are unlikely to be exclusive. The molecular mechanisms that integrate various environmental and inherent controls to establish the character of cells in the myogenic lineage are a matter of intense research, and the recent emergence of powerful tools in mouse genetics has provided significant new insights (Lewandoski 2007). The following sections review our current understanding of the molecular regulation of muscle formation during development and in the adult.

2. MORPHOGEN GRADIENTS AND MYOGENESIS

Signaling molecules, which can function as morphogens, control the genetic networks patterning the structure of tissues in the developing embryo through to the adult organism (Gurdon and Bourillot 2001; Davidson 2010). Depending on the concentration and distance from the source, morphogens qualitatively trigger different cellular behavioral responses (Gurdon et al. 1998).

2.1. Somitogenesis

The positions and identities of cells that will form the three germ layers are determined early in gestation (Arnold and Robertson 2009). The prepatterned embryo subsequently develops the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Mesoderm is anatomically separated into paraxial, intermediate, and lateral mesoderm, with respect to position from the midline. In the course of development, local oscillations in gene expression and morphogen gradients induce pairwise condensations of paraxial mesoderm into somites, which develop progressively from head to tail (Fig. 1A) (Aulehla and Pourquie 2006). Somites are the first metameric structures in mammalian embryos. Spatiotemporal somitogenesis involves expression of genes involved directly or indirectly in the Notch and Wnt pathways as well as morphogen gradients of Wnt, FGF, and retinoic acid (Fig. 1B). Toward the caudal part of the paraxial mesoderm, the presence of high concentrations of Fgf and Wnt restricts cells to a mesenchymal, undifferentiated state (Aulehla and Pourquie 2010). Wnt and Fgf signaling have been shown to control periodic activity of the Notch pathway, which, in turn, controls cyclic genes involved in the generation of somites (Hofmann et al. 2004). After the cells leave the caudal region, cyclic expression of genes stops, and increasing levels of retinoic acid establish polarity of the somite, which subsequently develops distinct dorso–ventral compartments (Fig. 1C) (Takahashi 2001; Parker et al. 2003). The most ventral part forms the mesenchymal sclerotome, which contains precursors to cartilage and bone. The most dorsal portion of the somite remains epithelial and becomes the dermomyotome. Skeletal muscles of the body, with the exception of some head muscles, are derived from cells of this structure. Cells of the dermomyotome are marked by the expression of the paired box transcription factors Pax3 and Pax7 and low expression of the basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor Myf5 (Jostes et al. 1990; Goulding et al. 1991; Kiefer and Hauschka 2001). The lips of the dermomyotome will mature into the myotome, a primitive muscle structure containing committed muscle cells expressing high levels of MyoD, another member of the basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors, and Myf5 (Sassoon et al. 1989; Cinnamon et al. 2001; Kiefer and Hauschka 2001; Ordahl et al. 2001). MyoD and Myf5 are both considered to be markers of terminal specification to the muscle lineage (Pownall et al. 2002). In the majority of muscle progenitors, MyoD functions downstream from Pax3 and Pax7 in the genetic hierarchy of myogenic regulators, whereas Myf5, depending on the context, can also act in parallel with the Pax transcription factors (Bryson-Richardson and Currie 2008; Punch et al. 2009; Bismuth and Relaix 2010).

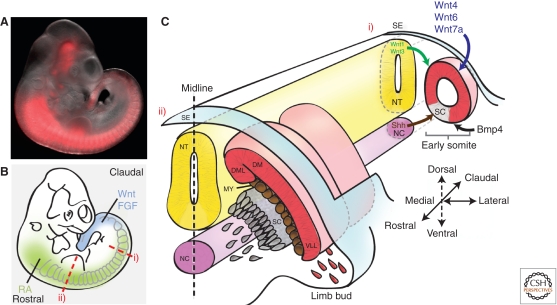

Figure 1.

Embryonic myogenesis. (A) Embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) mouse embryo carrying an Myf5 lineage tracer that induces irreversible expression of a red fluorescent protein. Expression can be observed in the presomitic mesoderm, the somites, and in several head structures. (B) Illustration of the morphogen gradients along the rostral–caudal axis of the embryo. (C) Schematic of transverse sections through the embryo at early (i) and late (ii) stages of somitogenesis. (Ci) Morphogens secreted from various domains in the embryo specify the early somite to form the sclerotome (SC) and dermomyotome (DM). Wnts secreted from the dorsal neural tube (NT) and surface ectoderm (SE) along with bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) from the lateral plate mesoderm maintain the undifferentiated state of the somite, whereas Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signals from the neural tube floor plate and notochord (NC) to induce the formation of the sclerotome. (Cii) As the sclerotome segregates, muscle progenitor cells (MPCs) from the dorsomedial (DML) and ventrolateral (VLL) lips of the dermomyotome mature to give rise to the myotome (MY). At the level of the limb bud, Pax3-dependent migrating MPCs delaminate from the ventrolateral lips to later give rise to limb muscles.

As the embryo develops, the central part of the dermomyotome disintegrates, and muscle progenitors intercalate into the primary myotome (Ben-Yair and Kalcheim 2005; Gros et al. 2005; Manceau et al. 2008). This population of progenitors gives rise to a fraction of the satellite cells residing in postnatal skeletal muscle (Gros et al. 2005; Kassar-Duchossoy et al. 2005; Relaix et al. 2005; Schienda et al. 2006). Dorsal muscles are formed from the epaxial part of the dermomyotome and myotome, whereas lateral trunk and limb muscles are derived from the hypaxial domains (Parker et al. 2003). Hypaxial muscles of the body wall are generated by a ventral-ward elongation of dermomyotome and myotome (Cinnamon et al. 1999). Muscles of the extremities, the diaphragm, and the hypoglossal chord are derived from myogenic cells with an extensive migratory capacity, which delaminate from the ventrolateral lip of the dermomyotome at the level of the limbs (Vasyutina and Birchmeier 2006). Head muscles are formed by cells originating in the prechordal and pharyngeal head mesoderm. The genesis of these muscle groups is controlled differentially from trunk and limb and has been discussed extensively elsewhere (Shih et al. 2008).

Cellular commitment in the somite is highly dependent on extrinsic factors. Epithelial cells in the newly formed somite initially have the potential of adopting a sclerotomal or a dermomyotomal fate. Classic transplantation experiments with immature somites that were grafted with a 180° rotation revealed that the patterning into dermomyotome and sclerotome was not altered (Aoyama and Asamoto 1988). This suggested that morphogen gradients control the establishment of these structures. Since this groundbreaking discovery, a plethora of signaling molecules emerging from the surrounding embryonic tissues has been shown to control the developmental compartmentalization of the somite.

2.2. Morphogens Patterning the Somite

Members of the Wnt family of proteins are of particular importance for the formation of the dermomyotome and myotome and consequently for developmental myogenesis (Geetha-Loganathan et al. 2008). Upon binding to their cellular Frizzled (Fzd) receptors, Wnts function either through canonical activation of the β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex or through different non-canonical pathways (van Amerongen and Nusse 2009). Among the Wnts involved in somite patterning are Wnt1 and Wnt3, which are secreted from the dorsal neural tube; and Wnt4, Wnt6, and Wnt7a, which emerge from the surface ectoderm (Parr et al. 1993). Mouse mutants deficient for Wnt1, and the functionally redundant Wnt3, lack parts of the dermomyotome, and the expression of the myogenic transcription factors Pax3 and Myf5 is reduced (Ikeya and Takada 1998). In explant cultures of mouse presomitic mesoderm, Wnt1 strongly increases Myf5 levels, whereas Wnt7a or Wnt6 preferentially induces expression of the myogenic regulatory factor MyoD (Tajbakhsh et al. 1998). Analysis of the expression of Wnt receptors in somites revealed that Fzd7 is expressed in the hypaxial portion of the somite, whereas Fzd1 and Fzd6 are expressed in the epaxial domain, a region marked by early expression of Myf5 (Borello et al. 1999a). Wnt1 and Fzd1/Fzd6 in the epaxial domain of the somite appear to signal canonically to control Myf5 expression, whereas the induction of MyoD through Wnt7a and Fzd7 depends on β-catenin independent, non-canonical signaling involving PKC (Borello et al. 2006; Brunelli et al. 2007). A requirement for active Fzd signaling during embryonic myogenesis has been confirmed by transplacental delivery of the Wnt antagonist sFRP3, which reduced the developmental formation of muscle fibers in a dose-dependent manner (Borello et al. 1999b).

Along with Wnts, Sonic hedgehog (Shh) is also involved in the positive specification of muscle progenitors in the somite. Shh is released from the notochord and floor plate of the neural tube. This factor is part of the Hedgehog family of proteins, which consists of two additional members: Desert hedgehog (Dhh) and Indian hedgehog (Ihh) (Echelard et al. 1993). Mammalian Hedgehog proteins interact with the Patched receptor and trigger the release of smoothened, which, in turn, regulates gene expression through GLI transcription factors (Lum and Beachy 2004). Shh or smoothened knockout mice display an impaired formation of the sclerotome as well as reduced expression of Myf5 in the myotome (Chiang et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 2001). Moreover, the absence of Shh signaling in developing zebrafish increases the number of Pax3- and Pax7-expressing cells in the somite but prevents subsequent myogenic lineage progression (Feng et al. 2006; Hammond et al. 2007). Gain-of-function studies in chicken embryos showed that ectopic expression of Shh increases levels of the sclerotomal marker Pax1, however, inhibited the expression of Pax3 in the dermomyotome (Johnson et al. 1994; Borycki et al. 1998). These findings suggest that Shh is essential for the maturation of dermomyotomal cells into MyoD/Myf5-expressing, committed myotomal cells that have down-regulated Pax3/7 expression. Consistent with this, a regulatory element of the Myf5 gene contains both TCF and GLI binding sites, explaining why Shh and canonical Wnt signals can activate Myf5 synergistically (Borello et al. 2006).

In contrast to the positive specification of cells by Shh and Wnt, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) inhibits expression of certain myogenic genes. BMPs comprise a subclass of the TGF-β superfamily that was originally identified because of their role in early bone formation (Tsumaki and Yoshikawa 2005). In many biological contexts, Wnt and BMP proteins are spatiotemporally secreted in overlapping or opposing gradients, which is suggestive of conserved mechanisms of cross talk between the involved pathways (Itasaki and Hoppler 2010). BMPs exert their activities through serine-threonine kinase receptors leading to activation of SMAD proteins and subsequent activation, or repression, of target genes (Liu et al. 1995; Miyazono et al. 2005). Bmp4, expressed in the lateral-plate mesoderm, appears to retain certain populations of muscle progenitors in an undifferentiated state by fostering expression of Pax3 while delaying Myf5 and MyoD induction (Pourquie et al. 1995). These findings suggest that BMP functions to expand the pool of myogenic progenitors before further commitment is initiated. Wnt and Shh antagonize BMP signals in the dorsomedial lip of the dermomyotome through increased levels of Noggin (Hirsinger et al. 1997; Marcelle et al. 1997; Reshef et al. 1998). This appears to allow the localized up-regulation of MyoD and has been proposed to initiate myotome formation. In line with these findings, noggin knockout mice display impaired myotomal development in caudal regions of the embryo, with somites remaining in an epithelial state marked by high expression of Pax3 (McMahon et al. 1998).

In several tissues, fate decisions of progenitor cells during embryonic development appear to be critically influenced by Notch signaling (Bray 2006). The Notch signaling pathway also plays an important role in the regulation of vertebrate myogenesis (Hirsinger et al. 2001; Schuster-Gossler et al. 2007; Vasyutina et al. 2007). Notch mediates cell–cell communication by engaging with Delta and Jagged ligands on neighboring cells. Delta1 is presented to embryonic progenitors by a subset of migrating neural crest cells (Rios et al. 2011). Only dermomyotomal cells that transiently made contact with these Delta1-expressing cells undergo myogenesis. Active Notch signaling has been shown to suppress MyoD in cooperation with the DNA-binding protein RBP-J and the transcriptional repressor Hes1 (Jarriault et al. 1995; Kuroda et al. 1999). Mutations in the Notch ligand Delta1 or RBP-J result in excessive myogenic differentiation and a loss of muscle precursors (Schuster-Gossler et al. 2007; Vasyutina et al. 2007). Together, these findings suggest that, somewhat similar to BMP, Notch signaling promotes the expansion of myogenic precursors while preventing differentiation.

Muscles, such as those found in the limbs, forming distant from the somites require a population of Pax3-dependent migrating progenitors (Epstein et al. 1996). At particular sites, that is, at the levels of forelimbs and hindlimbs, the ventral dermomyotome undergoes an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This process will give rise to long-range migratory cells that retain an extensive mitotic capacity allowing their proliferation at target sites. Classic EMT markers such as N-cadherin and fibronectin control the migratory capacity of these myogenic progenitors by modulating their adhesiveness to the surrounding embryonic structures (Jaffredo et al. 1988; Brand-Saberi et al. 1993). Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) and its receptor c-Met are critically involved in both the delamination and migration of these cells from the dermomyotome. In mouse mutants lacking either of those molecules, limb skeletal muscle is not formed (Bladt et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1995). HGF/SF has been shown to be released from non-somitic mesodermal cells, marking the migratory route of myogenic progenitors (Dietrich et al. 1999).

In summary, during development, a remarkably fine-tuned extrinsic regulatory system directs spatiotemporally distinct fates of self-renewal or differentiation to myogenic precursors. Within the myogenic lineage, extrinsic regulators can generally be divided into pro- or anti-commitment factors. The combined action of these factors guarantees a sufficient pool of cells for differentiation during embryonic myogenesis while maintaining a supply of reserve stem cells throughout development into adult life.

3. GENETIC NETWORKS CONTROLLING MYOGENESIS

Apart from extrinsic regulators of myogenesis, several levels of intrinsic complexity arise from hierarchical interactions between transcriptional regulators, regulatory RNAs, and chromatin-remodeling factors. Owing to the early discovery of the myogenic factors that act downstream in the genetic network controlling myogenesis, this topic is typically discussed bottom-up, starting with the factors involved in terminal specification toward the upstream regulators involved in the maintenance and self-renewal of uncommitted myogenic progenitors (Fig. 2).

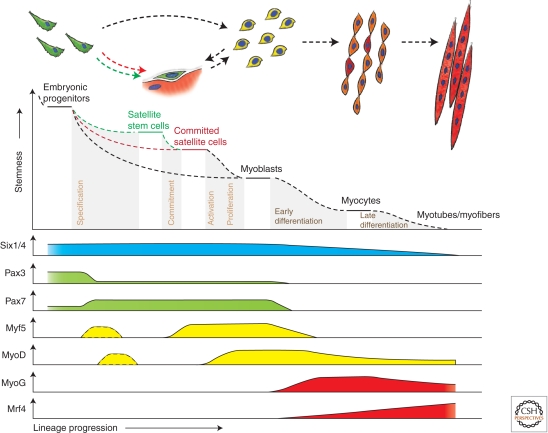

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of transcription factors regulating progression through the myogenic lineage. Muscle progenitors that are involved in embryonic muscle differentiation skip the quiescent satellite cell stage and directly become myoblasts. Some progenitors remain as satellite cells in postnatal muscle and form a heterogeneous population of stem and committed cells. Activated committed satellite cells (Myoblasts) can eventually return to the quiescent state. Six1/4 and Pax3/7 are master regulators of early lineage specification, whereas Myf5 and MyoD commit cells to the myogenic program. Expression of the terminal differentiation genes, required for the fusion of myocytes and the formation of myotubes, are performed by both myogenin (MyoG) and MRF4.

3.1. Myogenic Regulatory Factors

In 1987, pioneering subtractive hybridization studies using myoblast cDNA libraries identified the basic helix–loop–helix factor MyoD by its ability to transform a selection of cell types, such as fibroblasts, into cells that are capable of fusing into myotubes (Davis et al. 1987). Subsequently, three more myogenic basic helix–loop–helix factors—Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4 (also known as Myf6)—which are also able to induce myoblast traits in nonmuscle cell lines, were discovered (Braun et al. 1989; Edmondson and Olson 1989; Rhodes and Konieczny 1989; Braun et al. 1990; Miner and Wold 1990). The highly conserved MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4 genes are collectively expressed in the skeletal muscle lineage and are therefore referred to as myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) (Weintraub et al. 1991; Rudnicki and Jaenisch 1995). The basic domain of the MRFs mediates DNA binding, whereas the helix–loop–helix motif is required for heterodimerization with E proteins that mediate the recognition of genomic E-boxes, a motif found in the promoters of many muscle-specific genes (Massari and Murre 2000). Myf5 is the first MRF expressed during embryonic development, being transiently up-regulated in the paraxial mesoderm and later on in concert with the other MRFs during the formation of the myotome (Ott et al. 1991; Buckingham 1992). A few years after discovery of the MRFs, the unexpectedly normal skeletal muscle phenotype of Myf5 and MyoD knockout mice was reported (Braun et al. 1992; Rudnicki et al. 1992). Mice devoid of Myf5 display a somewhat delayed embryonic myogenesis that proceeds normally from the stage at which MyoD expression initiates (Braun et al. 1992). Conversely, MyoD knockouts compensate by increasing and prolonging Myf5 expression, which in wild-type mice declines at the more advanced developmental stage when MyoD expression starts (Rudnicki et al. 1992). These surprising results have been revealed to be due to redundancy of Myf5 and MyoD in myogenesis. This became apparent from the complete lack of skeletal muscle and myogenin expression in Myf5:MyoD double-null mice (Rudnicki et al. 1993). To elucidate whether a MyoD-dependent cell population can compensate for loss of Myf5-expressing cells, two laboratories used a conditional cell ablation approach in which diphtheria toxin expression was specifically induced within Myf5-positive cells (Gensch et al. 2008; Haldar et al. 2008). These studies revealed that Myf5 is not expressed in all myoblasts involved in the formation of the early myotome and that myogenesis was fully restored by a MyoD-expressing lineage. Consequently, two independent myogenic lineages that are eventually controlled by different upstream regulators are involved in muscle formation in the embryo. These findings emphasize the remarkable heterogeneity and plasticity of the muscular system that is present not only in the embryo but, as discussed in sections below, also in the adult myogenic progenitor pool.

Using a series of different Myf5 mutant alleles, it has been shown that the original knockin at the Myf5 locus also impaired the function of the neighboring MRF4 gene (Kassar-Duchossoy et al. 2004). However, the presence of a functional MRF4 allele only rescues minor aspects of embryonic myogenesis in Myf5:MyoD double-null mice. The analysis of myogenin knockout mice revealed that the expression of several differentiation markers, such as myosin heavy chain and MRF4, was reduced, whereas MyoD levels were normal (Hasty et al. 1993). Phenotypically, this resulted in normal somitic compartmentalization during development but manifested in diffuse myofiber formation and an abundance of undifferentiated myoblasts in the later stages of myogenesis. Taken together, these studies suggest a model in which Myf5 and MyoD, in a redundant fashion, act genetically upstream of myogenin and MRF4 to specify myoblasts for terminal differentiation. Myogenin and MRF4 are more directly involved in the differentiation process and trigger the expression of myotube-specific genes.

3.2. Paired-Homeobox Transcription Factors

The next level in the genetic hierarchy controlling myogenesis is dominated by the paired-homeobox transcription factors Pax3 and Pax7. All vertebrates appear to have at least one of these genes, and it has been suggested that their evolutionary origin lies in the duplication of a common ancestral gene (Noll 1993). Cells in the mouse dermomyotome express Pax3 and Pax7, with the highest levels of Pax7 in the central domain and preferential expression of Pax3 in the dorsal and ventral lips (Kassar-Duchossoy et al. 2005). However, only Pax3, but not Pax7, is expressed in long-range migrating cells, which form the initial limb musculature. Mouse embryos homozygous for the Splotch Pax3 loss-of-function mutation do not develop the hypaxial domain of the somite and consequently do not form limb or diaphragm muscles, but epaxial-derived muscles are less affected (Bober et al. 1994; Daston et al. 1996; Tremblay et al. 1998). Classifying Pax3 as genetically upstream, no MyoD transcript can be detected in the limbs of Splotch mutants. Placing Myf5 as the only MRF next to Pax3 upstream of MyoD, Pax3:Myf5:MRF4 triple-mutant mice are devoid of all body muscles and lack expression of MyoD and all other downstream myogenic factors (Tajbakhsh et al. 1997). Pax7, on the other hand, appears to be dispensable for embryonic muscle development (Seale et al. 2000). Suggesting that Pax3 and Pax7 are able to at least compensate partially for each other during embryonic myogenesis, muscle formation is more defective in Pax3:Pax7 double-knockout embryos when compared with the Splotch mutant alone, and only the early myotome develops (Relaix et al. 2005). Moreover, when Pax7 is knocked into the Pax3 locus, most of the functions of Pax3 are restored (Relaix et al. 2004). Pax7- and Pax3-cre drivers have been used to induce a conditional diphtheria toxin allele for studying the outcome of specific ablation of the respective cell populations (Hutcheson et al. 2009). Hutcheson et al. (2009) showed that loss of the Pax3 lineage is embryonically lethal and prevents the emergence of Pax7-positive cells, whereas ablation of Pax7-expressing cells only leads to defects in later stages of development, causing smaller muscles with fewer myofibers in the limbs at birth (Seale et al. 2000; Hutcheson et al. 2009). This led to the hypothesis that, similar to Drosophila muscle development, Pax3-positive cells are founder cells forming a template of initial fibers in the limb to which Pax7-positive cells then contribute by forming secondary fibers and establishing the satellite cell pool (Maqbool and Jagla 2007).

3.3. Sine Oculis–Related Homeobox Transcription Factors

The sine oculis–related homeobox 1 (Six1) and Six4 are currently considered to be the apex of the genetic regulatory cascade that directs dermomyotomal progenitors toward the myogenic lineage. Six family proteins are transcription factors characterized by the presence of two conserved domains, a Six-type homeodomain that binds to DNA and an amino-terminal Six domain that interacts with coactivators or corepressors of transcription (Kawakami et al. 2000; Tessmar et al. 2002; Zhu et al. 2002). Six proteins bind to and translocate the eyes-absent homologs Eya1 and Eya2 to the nucleus, where they act as cofactors to activate Six target genes, such as Pax3, MyoD, MRF4, and myogenin (Grifone et al. 2005). The overexpression of Six1 and Eya2 in somite explants triggers an up-regulation of Pax3, whereas Six1:Six4 or Eya1:Eya2 mouse mutants are devoid of Pax3 expression in the hypaxial dermomyotome and consequently do not form limb and trunk hypaxial muscles (Heanue et al. 2002; Grifone et al. 2007). Because a hypaxially active enhancer element of Myf5 contains both binding sites for Six factors and Pax3, these two factors are likely to also have parallel functions (Giordani et al. 2007). Myf5 expression within the epaxial dermomyotome, which is independent of Pax3, is also unaffected in Six1:Six4 double mutants, and dorsal muscles arising from this structure are the only remaining axial muscles in these mice (Grifone et al. 2005). Similar to the redundancy that is observed at lower levels of the myogenic genetic network, for example, for Pax3 and Pax7, individual mutants of the Six–Eya system appear to have milder defects, but their combined loss synergistically aggravates the observed phenotypes (Grifone et al. 2005, 2007).

3.4. Other Mechanisms of Gene Regulation

Transcription factors involved in myogenic lineage progression are not strictly acting in a linear manner but are organized in complex feedback and feed-forward networks. For instance, the temporal coordination of MRF-mediated gene expression is achieved by allowing certain genes to be directly activated by an individual MRF, whereas the induction of other genes in later stages of differentiation by the same MRF requires the participation of the earlier target gene products (Berkes and Tapscott 2005). MRFs can activate their own expression as well as that of MEF2 (Thayer et al. 1989; Potthoff and Olson 2007). MEF2 proteins do not have myogenic activity but potentiate the function of MRFs through transcriptional cooperation (Molkentin et al. 1995). An example of negative feedback in this system arises from the MEF2 transcriptional target HDAC9, which associates and represses MEF2’s activity (Haberland et al. 2007).

Apart from the network of classic transcription factors that integrate intrinsic and extrinsic input onto the gene expression program, other players such as microRNAs and chromatin-remodeling factors have emerged to be involved in the control of the muscle lineage. Pax7, for instance, associates with the Wdr5–Ash2L–MLL2 histone methyltransferase (HMT) complex, which, in the case of the Myf5 gene, resulted in H3K4 trimethylation of surrounding chromatin. Recruitment of HMT complexes by Pax factors could be a conserved mechanism to remodel the chromatin structure for the control of lineage-specific gene expression (McKinnell et al. 2008).

MicroRNAs are evolutionarily conserved, small non-coding RNAs that associate with the 3′ untranslated regions of target mRNAs to induce their translational repression or cleavage (Bartel 2004). By this means, one microRNA is capable of regulating multiple mRNAs at the same time. A well established example of a microRNA regulating myogenesis is miR206. This microRNA is up-regulated by MyoD and targets Pax3 and Pax7 mRNA. Through this miR206-mediated negative feedback mechanism, MyoD facilitates progression toward terminal differentiation (Chen et al. 2010; Hirai et al. 2010). Other microRNAs, controlling many aspects of skeletal muscle development, have been discovered, and future studies will, it is hoped, reveal their in vivo functions in myogenesis (Ge and Chen 2011).

4. ADULT MYOGENESIS

Unlike de novo embryonic muscle formation, muscle regeneration in higher vertebrates depends on the injured tissue retaining an extracellular matrix scaffolding that serves as a template for the Formation of muscle fibers (Ciciliot and Schiaffino 2010). Only amphibians, certain fishes, and some lower organisms can regenerate muscle without an instructive template, for example, following the amputation of appendages (Poss 2010). Tissue regeneration requires the recruitment of an undifferentiated progenitor to the site of injury. In mature skeletal muscle, this function is provided by the satellite cells. Satellite cells depend on the same genetic hierarchy that governs embryonic myogenesis (Fig. 2) (Rudnicki et al. 2008). These cells have been shown to use asymmetric divisions for self-maintenance and, at the same time, give rise to more committed myogenic progeny (Shinin et al. 2006; Conboy et al. 2007; Kuang et al. 2007). It has furthermore been demonstrated that satellite cells can enter several different mesodermal lineages such as muscle, bone, and brown fat (Asakura et al. 2001; Shefer et al. 2004; Seale et al. 2008). This cell type, therefore, fulfills the criteria for a true somatic stem cell: self-renewal and the ability to generate progeny of several distinct cell types (Potten and Loeffler 1990). However, the satellite cell population is highly heterogeneous, and the exact nature of the least committed adult muscle progenitor is extensively debated in the field (Biressi and Rando 2010). Somatic stem cells have acquired a certain fate and are therefore restricted to a selection of lineages (Weissman 2000). This specialization is accompanied by a higher dependence on extrinsic regulatory factors compared with embryonic stem cells, which, at least in the earliest stages of organismic development, rely to a higher degree on intrinsic programming (Jones and Wagers 2008; Rossant and Tam 2009; Zernicka-Goetz et al. 2009; Bentzinger et al. 2010).

4.1. The Satellite Cell Niche

Somatic stem cells depend on a specialized environment termed the “stem cell niche” (Jones and Wagers 2008). A stem cell niche is a compartment in an organ that supports self-renewal of stem cells while preventing them from differentiation (Scadden 2006). The niche microenvironment also instructs the commitment of stem cells into the respective organ-specific cell lineages. Removal of somatic stem cells from their niche is consequently accompanied by a loss of stem cell properties over time. Satellite cells seem to be particularly sensitive to such manipulation when compared, for example, with hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which after release can home back to their niche relatively efficiently while maintaining their stemness (Wilson and Trumpp 2006; Cosgrove et al. 2009). In their niche, satellite cells sit closely apposed to the myofiber and are covered by the extracellular matrix of the basement membrane (Fig. 3) (Mauro 1961). They are furthermore often localized in close proximity to capillaries, which supply them with essentials (Christov et al. 2007). Unless activated by muscle injury or other stimuli, their niche allows adult satellite cells to persist in a quiescent, non-proliferative state, which is critical for their lifelong maintenance (Schultz et al. 1978; Abou-Khalil et al. 2009; Shea et al. 2010). The dependence of satellite cells on their niche is becoming dramatically apparent with regard to the poor success rate of stem cell therapy for diseased muscle (Peault et al. 2007; Farini et al. 2009). The underlying problem is that satellite cells cannot currently be isolated and expanded in vitro because they rapidly differentiate into myoblasts, a more committed muscle precursor marked by the irreversible expression of Myf5, MyoD, and Myogenin (Boonen and Post 2008). Owing to the challenges of culturing satellite cells, the time frame for ex vivo correction of gene defects and subsequent autologous grafting is highly limited. Other problems in such therapeutic settings are the small amount of satellite cells that can be obtained from a muscle biopsy versus the difficulty of grafting several hundreds of muscles all over the body. Satellite cells in the mouse outnumber HSCs, likely also in humans (Box1). However, in contrast to HSCs, their poor accessibility and their niche addiction limit their possible therapeutic use. An alternative approach for stem cell therapy of diseased muscle is the use of embryonic stem (ES) cell-derived or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell-derived myogenic cells. Ectopic expression of Pax7 has been shown to be sufficient to reprogram ES and iPS cells into a myogenic cell type that can contribute to muscle fibers and populate the satellite cell niche upon transplantation (Darabi et al. 2011a,b). However, a major concern for the therapeutic use of ES and iPS cells is their potential to form tumors (Knoepfler 2009).

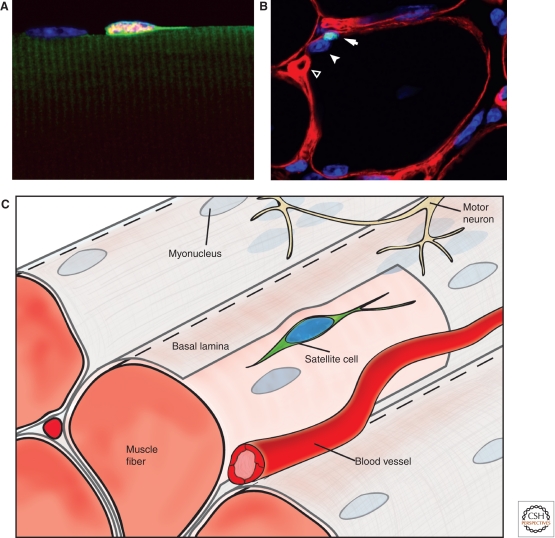

Figure 3.

Schematic of skeletal muscle and the satellite cell niche. (A) Satellite cells reside along the host muscle fiber and are marked by Pax7 expression (red); nuclei (blue); cytoplasm (green). (B) Satellite cells (arrow) marked by Pax7 (green) are found beneath the basal lamina (red) that surrounds each muscle fiber. In mature muscle, they are always associated with a myonucleus (arrowhead) and are in close proximity to local capillaries (empty arrowhead). (C) Representation of skeletal muscle and the satellite cell niche. Molecular signals within the niche govern the behavioral response of satellite cells in maintaining quiescence or activation during injury.

BOX 1. ABUNDANCE OF SATELLITE STEM CELLS IN THE MOUSE.

The average number of fibers in the extensis digitorum longus (EDL) muscle of a mouse is estimated to be on the order of 1000 (Luff and Goldspink 1970; Ontell and Kozeka 1984; Rosenblatt and Parry 1992; Matsakas et al. 2010). In young adult mice, each of these fibers contains six to seven satellite cells that express Pax7 (Shefer et al. 2006; Ono et al. 2010; Starkey et al. 2011). This results in about 6500 satellite cells per EDL muscle, which at the respective age weighs 11–12 mg (Rosenblatt and Parry 1992; Bentzinger et al. 2008; O’Neill et al. 2011). According to this, 1 mg of muscle will contain roughly 550 satellite cells. The average muscle mass of a mouse is estimated to be 40% of the body weight (International Life Science Institute 1994). Therefore, if the number of satellite cells is assumed to be constant across all muscle types, a mouse with an adult body weight of 20–30 g and a corresponding muscle mass of 8–12 g will contain more than 4 million satellite cells (The Jackson Laboratory 1994). This number is certainly an understatement because slow-contracting muscles reportedly contain more satellite cells when compared with fast muscles like the EDL (Collins et al. 2005; Shefer et al. 2006). It has been shown that the satellite stem cell population comprises ∼10% of satellite cells (Kuang et al. 2007). This results in at least 400,000 satellite stem cells per adult mouse. The number of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) has been estimated to lie between 10,000 and 20,000 (Abkowitz et al. 2002; Dingli and Michor 2006; Ainseba and Benosman 2011). Therefore, satellite stem cells outnumber HSCs severalfold and are likely to be some of the most abundant tissue-specific stem cells in the mouse and probably in most other vertebrates.

4.2. Origin of Satellite Cells

Several studies have proven through direct or indirect means that adult satellite cells originate from multipotential cells of the somite. When diphtheria toxin-mediated cell death is induced in Pax3/Pax7-expressing cells in the developing mouse somite, no muscle progenitors are found in the limbs (Hutcheson et al. 2009). Lineage tracing experiments using Cre-stop-flox permanent fluorescent labeling, as well as classic quail/chick grafting experiments, proved the origin of satellite cells to lie within dermomyotomal Pax3/Pax7-expressing cells (Gros et al. 2005; Relaix et al. 2005; Schienda et al. 2006; Hutcheson et al. 2009; Lepper and Fan 2010). Interestingly, cells derived from lineages other than muscle have also been shown to possess myogenic potential. Bone marrow–derived progenitors, skeletal muscle side population cells, mesoangioblasts, pericytes, CD133 (Prom1)+ progenitors, and PW1 (Peg3)+ interstitial cells are able to participate in the formation of multinucleated myotubes (Ferrari et al. 1998; Gussoni et al. 1999; Sampaolesi et al. 2003; Torrente et al. 2004; Dellavalle et al. 2007; Mitchell et al. 2010). However, when Pax7-expressing satellite cells are ablated by diphtheria toxin from adult muscle, no other cell type appears to replenish the satellite cell pool or repair the tissue following injury (Lepper et al. 2011). This shows that Pax7-expressing satellite cells are the major or only mediators of myofiber regeneration in the adult. All satellite cells, whatever origin, express Pax7, and in some muscles also Pax3, throughout the life of the organism (Kuang and Rudnicki 2008). Constitutive Pax7 knockout mice present a loss of satellite cells that manifests after birth (Seale et al. 2000). A requirement for Pax7 exists up to 3 wk after birth, a phase of intense proliferation of myogenic progenitors in the satellite cell position, but its function after this early postnatal growth period remains to be elucidated (Lepper et al. 2009).

4.3. Satellite Stem Cells

Skeletal muscle has a remarkable regenerative capacity and even following multiple rounds of injury the satellite cell pool is maintained at a constant size. This suggests the existence of a replenishing cell population or of a self-renewal process in satellite cells. Self-renewal either requires stochastic differentiation or asymmetric division (Fig. 4) (Kuang et al. 2008). In the stochastic paradigm, one stem cell divides to give rise to two committed daughter cells, while another stem cell gives rise to two identical daughter stem cells to maintain a constant progenitor pool. Asymmetric divisions, in contrast, give rise to a father cell that is identical to the original stem cell and a committed daughter cell. Indeed, asymmetric cosegregation of DNA strands into different daughter cells has been documented for satellite cells (Shinin et al. 2006; Conboy et al. 2007). A lineage tracing approach using a Myf5-Cre-stop-flox-YFP reporter mouse line revealed that a small subpopulation, ∼10% of satellite cells, has never expressed Myf5 (Kuang et al. 2007). Such Myf5-YFP-reporter-negative cells have been shown to divide in an asymmetrical apical–basal manner with respect to the muscle fiber membrane, giving rise to a more committed YFP-reporter-positive cell and a negative cell that self-renewed. Moreover, upon transplantation into satellite cell-depleted muscle, YFP-reporter-negative cells had a much higher capacity to repopulate the satellite cell niche when compared with the reporter-positive population that quickly differentiated. These data suggest that the satellite cell pool in adult skeletal muscle contains an asymmetrically dividing, self-renewing population of satellite stem cells that is responsible for maintenance and homeostasis of the satellite cell population. More evidence for asymmetry and self-renewal within the satellite cell niche comes from studies using muscle fiber cultures that were monitored for the expression of MyoD (Zammit et al. 2004). In this paradigm, a subset of proliferating committed Pax7/MyoD double-positive satellite cells has been shown to eventually give rise to Pax7-positive, MyoD-negative cells through asymmetric division. This suggests an elaborate self-renewal mechanism that prevents lineage progression and terminal differentiation.

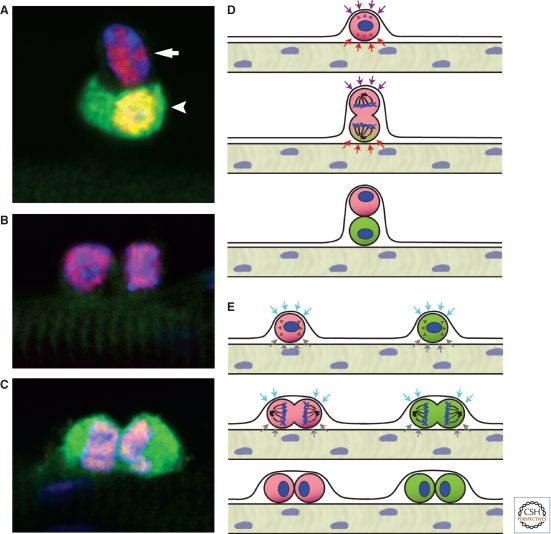

Figure 4.

Asymmetric versus stochastic modes of satellite cell division. As determined by lineage tracing, 10% of adult satellite cells have never expressed Myf5 and are referred to as “satellite stem cells.” (A) Satellite stem cells (arrow) undergo asymmetric division in an apical–basal orientation in which the daughter cell that is detached from the basal lamina up-regulates Myf5 and the fluorescent lineage tracer YFP (arrowhead). Pax7 (red); YFP (green); nuclei (blue). (B,C) In the stochastic mode of division, both types of satellite cells divide planar along the host fiber and give rise to two identical daughter cells. (D) Model of apical-basal divisions leading to an asymmetric outcome. Opposing signals from the basal lamina and the myofiber control the orientation of DNA spindles and the asymmetric cosegregation of proteins and DNA strands. Post-cytokinesis, daughter cells continue to be subjected to different signals leading to asymmetric cell fates. (E) Planar divisions lead to the symmetric expansion of cells. Signals such as the Wnt7a–PCP pathway drive the planar orientation of DNA spindles. Daughter cells in this outcome remain attached to the host fiber and the basal lamina, thus receiving similar signals, and maintain identical cell fates.

4.4. Extrinsic Regulation of Adult Myogenesis

Similar to embryonic development, a wide variety of signaling molecules in the niche control the fate of satellite cells in mature muscle (Bentzinger et al. 2010). In analogy to developmental processes, Wnt proteins have emerged as crucial regulators of satellite cell commitment and self-renewal during postnatal myogenesis. A transition from Notch signaling, which functions to expand the progenitor pool of adult skeletal muscle upon injury, toward canonical Wnt3a signaling has been reported to be required for efficient myoblast differentiation and muscle regeneration (Brack et al. 2008). Another Wnt family member, Wnt7a, which is released from regenerating muscle fibers, signals through the non-canonical planar cell polarity pathway to expand the previously mentioned Myf5-YFP-reporter-negative satellite stem cell population through symmetric divisions occurring parallel to the fiber (Le Grand et al. 2009). Wnt7a-mediated expansion of the satellite stem cell pool has been shown to dramatically enhance the regenerative capacity of muscle following injury. Other factors that appear to be involved in the regulation of adult muscle progenitors are HGF, FGFs, IGF-1 splice variants, myostatin, and TGF-β (Kuang et al. 2008; Bentzinger et al. 2010).

The role of extrinsic regulatory factors in adult myogenesis is another example of analogy to the mechanisms regulating developmental muscle formation. Some factors prevent lineage progression while facilitating an expansion of the uncommitted progenitor pool following injury, whereas others, in an antagonistic manner, control the up-regulation of MRFs and the subsequent establishment of the molecular fusion machinery for the differentiation into muscle fibers. The development of drugs that selectively influence these molecular pathways could enable the mobilization of satellite cells in diseased muscle, thereby enhancing the tissue’s own regenerative capacity. However, screening of therapeutic compounds is severely hindered by the inability to cultivate satellite cells. Novel technical approaches such as single fiber culture screens or improved ex vivo cultivation methods in biosynthetically optimized niches are required to overcome these obstacles.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Our understanding of myogenesis has taken us far away from a simplistic view, and it is clear now that the underlying molecular mechanisms function in an interaction network that is much more than the sum of its individual components. The involved signaling molecules and transcription factors can act in synergy or antagonism in feedback and feed-forward loops. This myriad of regulatory inputs orchestrates myogenesis in embryonic development and enables reactivation of the pathways in adult muscle repair. Recent technological advances pave the way for the investigation of biological networks controlling myogenesis on a proteome- and genome-wide scale (Doherty and Whitfield 2011; MacQuarrie et al. 2011). Therefore, it is to be expected that large-scale data analysis, in conjunction with integrative biological experimentation, will be an important part of future research in the field. We hope that this will enable us to approach the ultimate goal of efficiently manipulating the behavior and function of muscle stem cells in vitro and in vivo so that they can be used for regenerative medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Studies from the laboratory of M.A.R. were supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Muscular Dystrophy Association, National Institutes of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Canadian Stem Cell Network, and Canada Research Chair Program. M.A.R. holds the Canada Research Chair in Molecular Genetics and is an International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. C.F.B. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation. We thank Gregory Addicks and David Wilson for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Editors: Patrick P.L. Tam, W. James Nelson, and Janet Rossant

Additional Perspectives on Mammalian Development available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Abkowitz JL, Catlin SN, McCallie MT, Guttorp P 2002. Evidence that the number of hematopoietic stem cells per animal is conserved in mammals. Blood 100: 2665–2667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Khalil R, Le Grand F, Pallafacchina G, Valable S, Authier FJ, Rudnicki MA, Gherardi RK, Germain S, Chretien F, Sotiropoulos A, et al. 2009. Autocrine and paracrine angiopoietin 1/Tie-2 signaling promotes muscle satellite cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 5: 298–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainseba B, Benosman C 2011. Global dynamics of hematopoietic stem cells and differentiated cells in a chronic myeloid leukemia model. J Math Biol 62: 975–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama H, Asamoto K 1988. Determination of somite cells: Independence of cell differentiation and morphogenesis. Development 104: 15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ, Robertson EJ 2009. Making a commitment: Cell lineage allocation and axis patterning in the early mouse embryo. Nat Rev 10: 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura A, Komaki M, Rudnicki M 2001. Muscle satellite cells are multipotential stem cells that exhibit myogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic differentiation. Differentiation 68: 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulehla A, Pourquie O 2006. On periodicity and directionality of somitogenesis. Anat Embryol 211: 3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulehla A, Pourquie O 2010. Signaling gradients during paraxial mesoderm development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP 2004. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzinger CF, Romanino K, Cloetta D, Lin S, Mascarenhas JB, Oliveri F, Xia J, Casanova E, Costa CF, Brink M, et al. 2008. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab 8: 411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzinger CF, von Maltzahn J, Rudnicki MA 2010. Extrinsic regulation of satellite cell specification. Stem Cell Res Ther 1: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yair R, Kalcheim C 2005. Lineage analysis of the avian dermomyotome sheet reveals the existence of single cells with both dermal and muscle progenitor fates. Development 132: 689–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ 2005. MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16: 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biressi S, Rando TA 2010. Heterogeneity in the muscle satellite cell population. Semin Cell Dev Biol 21: 845–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth K, Relaix F 2010. Genetic regulation of skeletal muscle development. Exp Cell Res 316: 3081–3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bladt F, Riethmacher D, Isenmann S, Aguzzi A, Birchmeier C 1995. Essential role for the c-met receptor in the migration of myogenic precursor cells into the limb bud. Nature 376: 768–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bober E, Franz T, Arnold HH, Gruss P, Tremblay P 1994. Pax-3 is required for the development of limb muscles: A possible role for the migration of dermomyotomal muscle progenitor cells. Development 120: 603–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonen KJ, Post MJ 2008. The muscle stem cell niche: Regulation of satellite cells during regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 14: 419–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Buffa V, Sonnino C, Melchionna R, Vivarelli E, Cossu G 1999a. Differential expression of the Wnt putative receptors Frizzled during mouse somitogenesis. Mech Dev 89: 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Coletta M, Tajbakhsh S, Leyns L, De Robertis EM, Buckingham M, Cossu G 1999b. Transplacental delivery of the Wnt antagonist Frzb1 inhibits development of caudal paraxial mesoderm and skeletal myogenesis in mouse embryos. Development 126: 4247–4255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Berarducci B, Murphy P, Bajard L, Buffa V, Piccolo S, Buckingham M, Cossu G 2006. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulates Gli-mediated Myf5 expression during somitogenesis. Development 133: 3723–3732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycki AG, Mendham L, Emerson CP Jr 1998. Control of somite patterning by Sonic hedgehog and its downstream signal response genes. Development 125: 777–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Shen J, Rando TA 2008. A temporal switch from Notch to Wnt signaling in muscle stem cells is necessary for normal adult myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2: 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Saberi B, Krenn V, Grim M, Christ B 1993. Differences in the fibronectin-dependence of migrating cell populations. Anat Embryol 187: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Buschhausen-Denker G, Bober E, Tannich E, Arnold HH 1989. A novel human muscle factor related to but distinct from MyoD1 induces myogenic conversion in 10T1/2 fibroblasts. EMBO J 8: 701–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Bober E, Winter B, Rosenthal N, Arnold HH 1990. Myf-6, a new member of the human gene family of myogenic determination factors: Evidence for a gene cluster on chromosome 12. EMBO J 9: 821–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Rudnicki MA, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R 1992. Targeted inactivation of the muscle regulatory gene Myf-5 results in abnormal rib development and perinatal death. Cell 71: 369–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray SJ 2006. Notch signalling: A simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev 7: 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli S, Relaix F, Baesso S, Buckingham M, Cossu G 2007. β-Catenin-independent activation of MyoD in presomitic mesoderm requires PKC and depends on Pax3 transcriptional activity. Dev Biol 304: 604–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson-Richardson RJ, Currie PD 2008. The genetics of vertebrate myogenesis. Nat Rev Genet 9: 632–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M 1992. Making muscle in mammals. Trends Genet 8: 144–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charge SB, Rudnicki MA 2004. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev 84: 209–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Tao Y, Li J, Deng Z, Yan Z, Xiao X, Wang DZ 2010. microRNA-1 and microRNA-206 regulate skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by repressing Pax7. J Cell Biol 190: 867–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, Westphal H, Beachy PA 1996. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature 383: 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christov C, Chretien F, Abou-Khalil R, Bassez G, Vallet G, Authier FJ, Bassaglia Y, Shinin V, Tajbakhsh S, Chazaud B, et al. 2007. Muscle satellite cells and endothelial cells: Close neighbors and privileged partners. Mol Biol Cell 18: 1397–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciliot S, Schiaffino S 2010. Regeneration of mammalian skeletal muscle. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr Pharm Des 16: 906–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinnamon Y, Kahane N, Kalcheim C 1999. Characterization of the early development of specific hypaxial muscles from the ventrolateral myotome. Development 126: 4305–4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinnamon Y, Kahane N, Bachelet I, Kalcheim C 2001. The sub-lip domain—a distinct pathway for myotome precursors that demonstrate rostral–caudal migration. Development 128: 341–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, Partridge TA, Morgan JE 2005. Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell 122: 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy MJ, Karasov AO, Rando TA 2007. High incidence of non-random template strand segregation and asymmetric fate determination in dividing stem cells and their progeny. PLoS Biol 5: e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove BD, Sacco A, Gilbert PM, Blau HM 2009. A home away from home: Challenges and opportunities in engineering in vitro muscle satellite cell niches. Differentiation 78: 185–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi R, Pan W, Bosnakovski D, Baik J, Kyba M, Perlingeiro RC 2011a. Functional myogenic engraftment from mouse iPS cells. Stem Cell Rev 10.1007/s12015-011-9258-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi R, Santos FN, Filareto A, Pan W, Koene R, Rudnicki MA, Kyba M, Perlingeiro RC 2011b. Assessment of the myogenic stem cell compartment following transplantation of Pax3/Pax7-induced embryonic stem cell–derived progenitors. Stem Cells 29: 777–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daston G, Lamar E, Olivier M, Goulding M 1996. Pax-3 is necessary for migration but not differentiation of limb muscle precursors in the mouse. Development 122: 1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH 2010. Emerging properties of animal gene regulatory networks. Nature 468: 911–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML 2009. Regulation of muscle growth in neonates. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 12: 78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB 1987. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 51: 987–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellavalle A, Sampaolesi M, Tonlorenzi R, Tagliafico E, Sacchetti B, Perani L, Innocenzi A, Galvez BG, Messina G, Morosetti R, et al. 2007. Pericytes of human skeletal muscle are myogenic precursors distinct from satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol 9: 255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich S, Abou-Rebyeh F, Brohmann H, Bladt F, Sonnenberg-Riethmacher E, Yamaai T, Lumsden A, Brand-Saberi B, Birchmeier C 1999. The role of SF/HGF and c-Met in the development of skeletal muscle. Development 126: 1621–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingli D, Michor F 2006. Successful therapy must eradicate cancer stem cells. Stem Cells 24: 2603–2610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MK, Whitfield PD 2011. Proteomics moves from expression to turnover: Update and future perspective. Expert Rev Proteomics 8: 325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echelard Y, Epstein DJ, St-Jacques B, Shen L, Mohler J, McMahon JA, McMahon AP 1993. Sonic hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity. Cell 75: 1417–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson DG, Olson EN 1989. A gene with homology to the myc similarity region of MyoD1 is expressed during myogenesis and is sufficient to activate the muscle differentiation program. Genes Dev 3: 628–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Shapiro DN, Cheng J, Lam PY, Maas RL 1996. Pax3 modulates expression of the c-Met receptor during limb muscle development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 4213–4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farini A, Razini P, Erratico S, Torrente Y, Meregalli M 2009. Cell based therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Cell Physiol 221: 526–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Adiarte EG, Devoto SH 2006. Hedgehog acts directly on the zebrafish dermomyotome to promote myogenic differentiation. Dev Biol 300: 736–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Cusella-De Angelis G, Coletta M, Paolucci E, Stornaiuolo A, Cossu G, Mavilio F 1998. Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors. Science 279: 1528–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Chen J 2011. MicroRNAs in skeletal myogenesis. Cell Cycle 10: 441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geetha-Loganathan P, Nimmagadda S, Scaal M, Huang R, Christ B 2008. Wnt signaling in somite development. Ann Anat 190: 208–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch N, Borchardt T, Schneider A, Riethmacher D, Braun T 2008. Different autonomous myogenic cell populations revealed by ablation of Myf5-expressing cells during mouse embryogenesis. Development 135: 1597–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordani J, Bajard L, Demignon J, Daubas P, Buckingham M, Maire P 2007. Six proteins regulate the activation of Myf5 expression in embryonic mouse limbs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 11310–11315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding MD, Chalepakis G, Deutsch U, Erselius JR, Gruss P 1991. Pax-3, a novel murine DNA binding protein expressed during early neurogenesis. EMBO J 10: 1135–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifone R, Demignon J, Houbron C, Souil E, Niro C, Seller MJ, Hamard G, Maire P 2005. Six1 and Six4 homeoproteins are required for Pax3 and Mrf expression during myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Development 132: 2235–2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifone R, Demignon J, Giordani J, Niro C, Souil E, Bertin F, Laclef C, Xu PX, Maire P 2007. Eya1 and Eya2 proteins are required for hypaxial somitic myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 302: 602–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros J, Manceau M, Thome V, Marcelle C 2005. A common somitic origin for embryonic muscle progenitors and satellite cells. Nature 435: 954–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Bourillot PY 2001. Morphogen gradient interpretation. Nature 413: 797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Dyson S, St Johnston D 1998. Cells’ perception of position in a concentration gradient. Cell 95: 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gussoni E, Soneoka Y, Strickland CD, Buzney EA, Khan MK, Flint AF, Kunkel LM, Mulligan RC 1999. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature 401: 390–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M, Arnold MA, McAnally J, Phan D, Kim Y, Olson EN 2007. Regulation of HDAC9 gene expression by MEF2 establishes a negative-feedback loop in the transcriptional circuitry of muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 27: 518–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar M, Karan G, Tvrdik P, Capecchi MR 2008. Two cell lineages, myf5 and myf5-independent, participate in mouse skeletal myogenesis. Dev Cell 14: 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CL, Hinits Y, Osborn DP, Minchin JE, Tettamanti G, Hughes SM 2007. Signals and myogenic regulatory factors restrict pax3 and pax7 expression to dermomyotome-like tissue in zebrafish. Dev Biol 302: 504–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty P, Bradley A, Morris JH, Edmondson DG, Venuti JM, Olson EN, Klein WH 1993. Muscle deficiency and neonatal death in mice with a targeted mutation in the myogenin gene. Nature 364: 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Nakada D, Morrison SJ 2009. Mechanisms of stem cell self-renewal. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 25: 377–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heanue TA, Davis RJ, Rowitch DH, Kispert A, McMahon AP, Mardon G, Tabin CJ 2002. Dach1, a vertebrate homologue of Drosophiladachshund, is expressed in the developing eye and ear of both chick and mouse and is regulated independently of Pax and Eya genes. Mech Dev 111: 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai H, Verma M, Watanabe S, Tastad C, Asakura Y, Asakura A 2010. MyoD regulates apoptosis of myoblasts through microRNA-mediated down-regulation of Pax3. J Cell Biol 191: 347–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsinger E, Duprez D, Jouve C, Malapert P, Cooke J, Pourquie O 1997. Noggin acts downstream of Wnt and Sonic Hedgehog to antagonize BMP4 in avian somite patterning. Development 124: 4605–4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsinger E, Malapert P, Dubrulle J, Delfini MC, Duprez D, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, Pourquie O 2001. Notch signalling acts in postmitotic avian myogenic cells to control MyoD activation. Development 128: 107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann M, Schuster-Gossler K, Watabe-Rudolph M, Aulehla A, Herrmann BG, Gossler A 2004. WNT signaling, in synergy with T/TBX6, controls Notch signaling by regulating Dll1 expression in the presomitic mesoderm of mouse embryos. Genes Dev 18: 2712–2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DA, Zhao J, Merrell A, Haldar M, Kardon G 2009. Embryonic and fetal limb myogenic cells are derived from developmentally distinct progenitors and have different requirements for β-catenin. Genes Dev 23: 997–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya M, Takada S 1998. Wnt signaling from the dorsal neural tube is required for the formation of the medial dermomyotome. Development 125: 4969–4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Life Science Institute 1994. Physiological parameter values for PBPK models. US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Itasaki N, Hoppler S 2010. Crosstalk between Wnt and bone morphogenic protein signaling: A turbulent relationship. Dev Dyn 239: 16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Jackson Laboratory 1994. Animal Resources Body Weight Study of 1993. JAX® Notes 457: 1 [Google Scholar]

- Jaffredo T, Horwitz AF, Buck CA, Rong PM, Dieterlen-Lievre F 1988. Myoblast migration specifically inhibited in the chick embryo by grafted CSAT hybridoma cells secreting an anti-integrin antibody. Development 103: 431–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarriault S, Brou C, Logeat F, Schroeter EH, Kopan R, Israel A 1995. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature 377: 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Laufer E, Riddle RD, Tabin C 1994. Ectopic expression of Sonic hedgehog alters dorsal–ventral patterning of somites. Cell 79: 1165–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Wagers AJ 2008. No place like home: Anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nat Rev 9: 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostes B, Walther C, Gruss P 1990. The murine paired box gene, Pax7, is expressed specifically during the development of the nervous and muscular system. Mech Dev 33: 27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassar-Duchossoy L, Gayraud-Morel B, Gomes D, Rocancourt D, Buckingham M, Shinin V, Tajbakhsh S 2004. Mrf4 determines skeletal muscle identity in Myf5:Myod double-mutant mice. Nature 431: 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassar-Duchossoy L, Giacone E, Gayraud-Morel B, Jory A, Gomes D, Tajbakhsh S 2005. Pax3/Pax7 mark a novel population of primitive myogenic cells during development. Genes Dev 19: 1426–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Sato S, Ozaki H, Ikeda K 2000. Six family genes—structure and function as transcription factors and their roles in development. Bioessays 22: 616–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer JC, Hauschka SD 2001. Myf-5 is transiently expressed in nonmuscle mesoderm and exhibits dynamic regional changes within the presegmented mesoderm and somites I-IV. Dev Biol 232: 77–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS 2009. Deconstructing stem cell tumorigenicity: A roadmap to safe regenerative medicine. Stem Cells 27: 1050–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Rudnicki MA 2008. The emerging biology of satellite cells and their therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med 14: 82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA 2007. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell 129: 999–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Gillespie MA, Rudnicki MA 2008. Niche regulation of muscle satellite cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2: 22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Tani S, Tamura K, Minoguchi S, Kurooka H, Honjo T 1999. Delta-induced Notch signaling mediated by RBP-J inhibits MyoD expression and myogenesis. J Biol Chem 274: 7238–7244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand F, Jones AE, Seale V, Scime A, Rudnicki MA 2009. Wnt7a activates the planar cell polarity pathway to drive the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 4: 535–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper C, Fan CM 2010. Inducible lineage tracing of Pax7-descendant cells reveals embryonic origin of adult satellite cells. Genesis 48: 424–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM 2009. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature 460: 627–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan CM 2011. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3639–3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M 2007. Analysis of mouse development with conditional mutagenesis. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2007: 235–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Ventura F, Doody J, Massague J 1995. Human type II receptor for bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs): Extension of the two-kinase receptor model to the BMPs. Mol Cell Biol 15: 3479–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff AR, Goldspink G 1970. Total number of fibers in muscles of several strains of mice. J Anim Sci 30: 891–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum L, Beachy PA 2004. The Hedgehog response network: Sensors, switches, and routers. Science 304: 1755–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQuarrie KL, Fong AP, Morse RH, Tapscott SJ 2011. Genome-wide transcription factor binding: Beyond direct target regulation. Trends Genet 27: 141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manceau M, Gros J, Savage K, Thome V, McPherron A, Paterson B, Marcelle C 2008. Myostatin promotes the terminal differentiation of embryonic muscle progenitors. Genes Dev 22: 668–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool T, Jagla K 2007. Genetic control of muscle development: Learning from Drosophila. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 28: 397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelle C, Stark MR, Bronner-Fraser M 1997. Coordinate actions of BMPs, Wnts, Shh and Noggin mediate patterning of the dorsal somite. Development 124: 3955–3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari ME, Murre C 2000. Helix–loop–helix proteins: Regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol 20: 429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsakas A, Otto A, Elashry MI, Brown SC, Patel K 2010. Altered primary and secondary myogenesis in the myostatin-null mouse. Rejuvenation Res 13: 717–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro A 1961. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 9: 493–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnell IW, Ishibashi J, Le Grand F, Punch VG, Addicks GC, Greenblatt JF, Dilworth FJ, Rudnicki MA 2008. Pax7 activates myogenic genes by recruitment of a histone methyltransferase complex. Nat Cell Biol 10: 77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JA, Takada S, Zimmerman LB, Fan CM, Harland RM, McMahon AP 1998. Noggin-mediated antagonism of BMP signaling is required for growth and patterning of the neural tube and somite. Genes Dev 12: 1438–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Wold B 1990. Herculin, a fourth member of the MyoD family of myogenic regulatory genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 87: 1089–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Pannerec A, Cadot B, Parlakian A, Besson V, Gomes ER, Marazzi G, Sassoon DA 2010. Identification and characterization of a non-satellite cell muscle resident progenitor during postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol 12: 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T 2005. BMP receptor signaling: Transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 16: 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Black BL, Martin JF, Olson EN 1995. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell 83: 1125–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll M 1993. Evolution and role of Pax genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 3: 595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill HM, Maarbjerg SJ, Crane JD, Jeppesen J, Jorgensen SB, Schertzer JD, Shyroka O, Kiens B, van Denderen BJ, Tarnopolsky MA, et al. 2011. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 16092–16097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Boldrin L, Knopp P, Morgan JE, Zammit PS 2010. Muscle satellite cells are a functionally heterogeneous population in both somite-derived and branchiomeric muscles. Dev Biol 337: 29–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontell M, Kozeka K 1984. Organogenesis of the mouse extensor digitorum logus muscle: A quantitative study. Am J Anat 171: 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordahl CP, Berdougo E, Venters SJ, Denetclaw WF Jr 2001. The dermomyotome dorsomedial lip drives growth and morphogenesis of both the primary myotome and dermomyotome epithelium. Development 128: 1731–1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MO, Bober E, Lyons G, Arnold H, Buckingham M 1991. Early expression of the myogenic regulatory gene, myf-5, in precursor cells of skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. Development 111: 1097–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MH, Seale P, Rudnicki MA 2003. Looking back to the embryo: Defining transcriptional networks in adult myogenesis. Nat Rev Genet 4: 497–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, McMahon AP 1993. Mouse Wnt genes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development 119: 247–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peault B, Rudnicki M, Torrente Y, Cossu G, Tremblay JP, Partridge T, Gussoni E, Kunkel LM, Huard J 2007. Stem and progenitor cells in skeletal muscle development, maintenance, and therapy. Mol Ther 15: 867–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Sanchez Alvarado A 2007. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: From humans to planarians. Annu Rev Genet 41: 83–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss KD 2010. Advances in understanding tissue regenerative capacity and mechanisms in animals. Nat Rev Genet 11: 710–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS, Loeffler M 1990. Stem cells: Attributes, cycles, spirals, pitfalls and uncertainties. Lessons for and from the crypt. Development 110: 1001–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff MJ, Olson EN 2007. MEF2: A central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development 134: 4131–4140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourquie O, Coltey M, Breant C, Le Douarin NM 1995. Control of somite patterning by signals from the lateral plate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92: 3219–3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall ME, Gustafsson MK, Emerson CP Jr 2002. Myogenic regulatory factors and the specification of muscle progenitors in vertebrate embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 747–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punch VG, Jones AE, Rudnicki MA 2009. Transcriptional networks that regulate muscle stem cell function. Wiley Interdiscip Rev 1: 128–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M 2004. Divergent functions of murine Pax3 and Pax7 in limb muscle development. Genes Dev 18: 1088–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M 2005. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature 435: 948–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshef R, Maroto M, Lassar AB 1998. Regulation of dorsal somitic cell fates: BMPs and Noggin control the timing and pattern of myogenic regulator expression. Genes Dev 12: 290–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SJ, Konieczny SF 1989. Identification of MRF4: A new member of the muscle regulatory factor gene family. Genes Dev 3: 2050–2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios AC, Serralbo O, Salgado D, Marcelle C 2011. Neural crest regulates myogenesis through the transient activation of NOTCH. Nature 473: 532–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt JD, Parry DJ 1992. γ irradiation prevents compensatory hypertrophy of overloaded mouse extensor digitorum longus muscle. J Appl Physiol 73: 2538–2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J, Tam PP 2009. Blastocyst lineage formation, early embryonic asymmetries and axis patterning in the mouse. Development 136: 701–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R 1995. The MyoD family of transcription factors and skeletal myogenesis. Bioessays 17: 203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Braun T, Hinuma S, Jaenisch R 1992. Inactivation of MyoD in mice leads to up-regulation of the myogenic HLH gene Myf-5 and results in apparently normal muscle development. Cell 71: 383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Schnegelsberg PN, Stead RH, Braun T, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R 1993. MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell 75: 1351–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Le Grand F, McKinnell I, Kuang S 2008. The molecular regulation of muscle stem cell function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 73: 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R, Tajbakhsh S 2007. Skeletal muscle stem cell birth and properties. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18: 870–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaolesi M, Torrente Y, Innocenzi A, Tonlorenzi R, D’Antona G, Pellegrino MA, Barresi R, Bresolin N, De Angelis MG, Campbell KP, et al. 2003. Cell therapy of α-sarcoglycan null dystrophic mice through intra-arterial delivery of mesoangioblasts. Science 301: 487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]