Abstract

Background

I-SPY 2 is a phase 2 standing multicenter platform trial designed to screen multiple experimental regimens in combination with standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. The goal is to matching experimental regimens with responding patient subtypes. We report results for veliparib, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, combined with carboplatin (VC).

Methods

Eligible women had ≥2.5 cm stage II/III breast cancer, categorized into 8 biomarker subtypes based on HER2, hormone-receptor status (HR) and MammaPrint. Patients are adaptively randomized within subtype to better performing regimens compared to standard therapy (control). Regimens are evaluated within 10 signatures, prospectively defined combinations of subtypes. VC plus standard therapy was considered for HER2-negative tumors and therefore evaluated in 3 signatures. The primary endpoint of I-SPY 2 is pathologic complete response (pCR). MR volume changes during treatment inform the likelihood that a patient will achieve pCR. Regimens graduate if and when they have a high (Bayesian) predictive probability of success in a subsequent phase 3 neoadjuvant trial within the graduating signature.

Results

VC graduated in triple-negative breast cancer with 88% predicted probability of phase 3 success. A total of 72 patients were randomized to VC and 44 to concurrent controls. Respective pCR estimates (95% probability intervals) were 51% (35%–69%) vs 26% (11%–40%). Greater toxicity of VC was manageable.

Conclusion

The design of I-SPY 2 has the potential to efficiently identify responding tumor subtypes for the various therapies being evaluated. VC added to standard therapy improves pCR rates specifically in triple-negative breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is genetically and clinically heterogeneous, making it challenging to identify optimal therapies. Although breast cancer mortality in the United States has decreased, over 40,000 women in the U.S. still die of this disease yearly.1 Further decreases in mortality will require therapeutic options that target tumor biology and can be delivered before metastases.

The neoadjuvant approach facilitates evaluating an individual patient’s response to treatment and holds promise for developing experimental therapies for disease while it is still curable.2 Long-term outcomes are equivalent to those when the same chemotherapy is given adjuvantly.2 Importantly, eradication of tumor in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, designated as pathologic Complete Response (pCR) in breast and axillary nodes at surgery, correlates with event-free and overall survival depending on molecular subtype, with particularly strong correlation for triple-negative (HER2−/HR−) and HER2+ diseases.3 For these reasons there is intense interest in the neoadjuvant approach.4,5

The I-SPY 2 TRIAL (Investigation of Serial Studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response Through Imaging and Molecular AnaLysis 2, I-SPY 2) is a multicenter, randomized phase 2 ‘platform’ trial in which experimental arms consisting of novel agents or novel combinations added to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy are adaptively randomized in patients with high risk primary breast cancer. The primary endpoint is pCR.6

The trial goal from the drug development perspective is to rapidly identify which patient subtypes (or ‘signature’), if any, are sufficiently responsive to enable a small, focused and successful phase 3 trial. From the perspective of patients in the trial, they are assigned with higher probability to regimens that are performing better for patients who share their biomarker subtypes and to better identify regimens that are more effective for such patients.

We report results from the first experimental regimen to “graduate,” i.e., leave the trial due to a strong efficacy signal: the poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) inhibitor veliparib and carboplatin, added to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

METHODS

Study design

I-SPY 2 is an ongoing, multicenter, open-label, adaptive phase 2 master protocol or ‘platform’ trial with multiple experimental arms that evaluate novel agents combined with standard neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancers at high risk of recurrence.6 Experimental treatments are compared against a common control arm of standard neoadjuvant therapy, with the primary endpoint being pCR, which is defined as no residual cancer in either breast or lymph nodes at time of surgery. Patients who dropout after starting therapy (with or without withdrawal of consent) or fail to have surgery for any reason are counted as non-pCRs.

Biomarker assessments (HER2, HR, MammaPrint) performed at baseline are used to classify patients into 2×2×2 = 8 prospectively defined subtypes for randomization purposes. In addition to standard IHC and FISH assays, the protocol included a microarray-based assay of HER2 expression (TargetPrintTM). This assay has previously shown high concordance with standard IHC and FISH assays of HER28. The adaptive randomization algorithm assigns patients with biomarker subtypes to competing drugs/arms based on current Bayesian probabilities of achieving pCR within that subtype vs control with 20% of patients assigned to control. Adaptive randomization speeds the identification of treatments that perform better within specific patient subtypes and helps avoid exposing patients to therapies that are unlikely to benefit them (Figure 1A).9,10

Figure 1A. I-SPY 2 Adaptive Design.

Figure 1A illustrates the steps within the I-SPY 2 adaptive process. When new patients are enrolled, their subtypes are assessed. As patients are randomized, their outcomes are used to update the Bayesian co-variate adjusted model which computes the predictive probability of success in phase 3 for each signature. Pre-defined termination rules are applied for each experimental arm to determine whether it should stop for futility, graduate, or continue, adding on additional experimental arms if accrual permitting. As the trial continues, for each experimental arm, the probability of superiority over control within each subtype is updated; and the randomization probabilities for each subtype into the various experimental arms are adapted (such that new patients entering the trial will be more likely to be randomized to an agent showing activity within their subtype).

To assess efficacy, ten clinically relevant biomarker ‘signatures’ were defined in the protocol: All; HR+; HR−; HER2+; HER2−; MP Hi-2; HER2+/HR+; HER2+/HR−; HER2−/HR+; HER2−/HR−. Experimental arms are continually evaluated against control for each of these signatures and “graduate” when and if they demonstrate statistical superiority in pCR rate. Statistical analyses are Bayesian.9,11 Graduation requires an 85% Bayesian predictive probability of success in a 300-patient equally randomized neoadjuvant phase 3 trial with a traditional statistical design comparing to the same control arm and primary endpoint, pCR, as in I-SPY 2. (see Supplementary Information). Predictive probabilities of success are power calculations for a 300-patient trial averaged with respect to the current probability distributions of pCR rates for the experimental arm and control.9,11 The modest size of this hypothetical future trial means that graduation occurs only when there is compelling evidence of an arm’s efficacy. Accrual to a graduating arm halts immediately, but all patients on the arm and its concurrent controls must complete surgery before graduation is announced. An experimental arm is dropped for futility if its predictive probability of success in a phase 3 trial <10% for all ten signatures. The maximum total number of patients assigned to any experimental arm is 120.

I-SPY 2 Eligibility & Enrollment

I-SPY 2 is open to women aged 18 and over, diagnosed with clinical stage II–III disease. Patients must have clinically or radiologically measureable disease in the breast, defined as > 2.5 cm. If a tumor meets this criteria by clinical exam, the tumor must also be >2 cm by imaging. Participants must have no prior cytotoxic treatment for this malignancy, have ECOG performance status of 0–1, and agree to consent to core biopsy and MRI. Patients with HR+/MP-low tumors are excluded because the potential benefit of chemotherapy is lower in patients with lower proliferative tumors and does not justify the risk of exposure investigational agents plus chemotherapy6,12

The veliparib/carboplatin (VC) regimen was not assigned to patients with HER2+ tumors due to the lack of safety data with trastuzumab.

All patients provide written, informed consent before initiating I-SPY2 screening. If eligible, a second consent is obtained after randomized open-label treatment assignment and prior to treatment.

Treatment

Participants received weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 (T) IV for 12 doses alone (control), or in combination with an experimental regimen (Figure 1B). Patients randomized to VC received 50 mg of veliparib by mouth twice daily for 12 weeks, and carboplatin at AUC 6 on weeks 1, 4, 7, and 10, concurrent with weekly paclitaxel. Following paclitaxel +/− VC, all patients received doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 (AC) IV every 2 to 3 weeks for 4 doses, with myeloid growth factor support as appropriate, followed by surgery that included axillary node sampling per NCCN and local practice guidelines. Radiation and endocrine adjuvant therapy was recommended following surgery using standard guidelines. Dose modifications for standard and experimental therapies are listed in Supplemental Table 4.

Figure 1B. I-SPY 2 Study Design.

Patients are screened for I-SPY 2 eligibility. Eligible patients are adaptively randomized to 12 weekly paclitaxel (and trastuzumab if HER2+) cycles (control) or in combination with one of several experimental agents followed by doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) × 4, with serial biomarkers (biopsies, blood draw and MRI scans) assessed over the course of their therapy. Only patients with HER2− disease were randomized to the veliparib/carboplatin arm.

Assessments

Core biopsy, blood draws and MRI were performed at baseline and 3 weeks after treatment began. MRI and blood draws were repeated between chemotherapy regimens and prior to surgery. All surgical specimens are evaluated by pathologists trained to assess residual tumor burden (RCB)7. Biomarker assessments include the Agendia 70-gene MammaPrint and TargetPrint HER2 gene expression using the Agendia 44K full genome microarray and reverse phase phosphoprotein array.

Study Oversight

The study was designed by the principal investigators and the I-SPY2 investigators. The drug manufacturer supplied the agent that was administered in an outpatient setting. All participating sites received institutional review approval. A data safety monitoring board meets monthly.

Statistical Considerations

Trial participants are categorized into 8 subtypes based on three biomarkers: HR status, HER2 status and MammaPrint High 1 (MP1) or High 2 (MP2) (supplemental Figure 1). The cutpoint between MP1 and MP2 is the median (−0.154) of I-SPY 1 participants who fit the eligibility criteria for I-SPY 2.(see Supplemental Figure 1)13

Following a Bayesian approach,10,11 at any given time each regimen’s pCR rate has a probability distribution within each of the 8 biomarker subtypes. This distribution is based on the results for all patients assigned to the regimen and assumes a covariate-adjusted logistic model with covariates HER2, HR, and MP statuses. These distributions allow for finding the (Bayesian) probability that each regimen is superior to control within each subtype. The randomization probabilities are defined in proportion to these probabilities and therefore they change over time.

A longitudinal statistical model of MRI volume after 3 and 12 weeks of therapy in comparison with baseline improves information about pCR rates via multiple imputation. When all patients on the regimen have had surgery MRI volumes are no longer required for calculating probabilities of pCR, but they are used to update the longitudinal model.

We report the final Bayesian probability distributions of pCR rates for an experimental regimen and its concurrently randomized controls for each signature by providing the estimated pCR rates (means of the respective distributions) and 95% probability intervals. We do not report the raw data within biomarker subtypes or signatures; our analysis carries greater precision than would any raw-data estimate. We provide, for each signature, the final probability that the experimental pCR rate is greater than that for control as well as the respective predictive probabilities of success in a future trial as described above.

Additional study design details are in Supplemental information.

RESULTS

Patients and disease characteristics

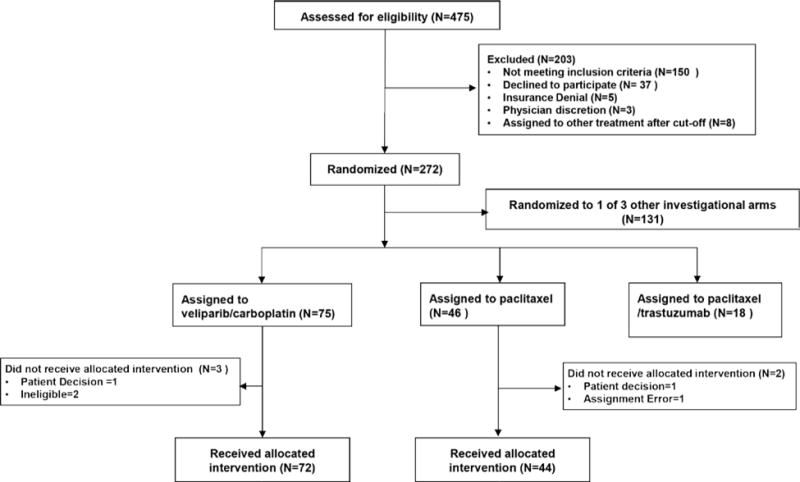

Patients were eligible to be randomized to VC from May 2010 to July 2012. During this period there were 3 to 5 arms (VC, neratinib, trebananib, ganitumumab, control) being randomized. A total of 72 patients were randomized to VC and evaluable for the primary endpoint; there were 44 concurrently randomized HER2− controls (Figure 1C). Baseline characteristics of participants (Table 1) were similar between the experimental and control arms. More VC patients (17% vs. 7%) carried a deleterious mutation in BRCA1/2. Two VC patients and one control patient did not have surgery; one VC patient withdrew consent prior to surgery; all 4 patients were counted as non-pCRs.

Figure 1C. I-SPY 2 Consort Diagram for veliparib/carboplatin arm and its concurrent control.

Only patients with HER2-negative disease were eligible for randomization to the VC arm. Patients were categorized as received allocated invention if they received at least one dose of experimental (or control) therapy.

Table 1.

Demographics

| V/C (n=72) | Control (n=44) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

|

| ||

| Median (Range) | 48.5 (27–70) | 47.5 (24–71) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity, n(%) | ||

|

| ||

| White | 54 (75%) | 34 (77%) |

| African American | 15 (21%) | 7 (16%) |

| Asian | 3 (4%) | 3 (7%) |

|

| ||

| HR Status, n (%) | ||

|

| ||

| Positive | 33 (46%) | 23 (52%) |

| Negative | 39 (54%) | 21 (48%) |

|

| ||

| BRCA1/2 Mutation Status, n(%) | ||

|

| ||

| Positive for Deleterious Mutation | 12 (17%) | 2 (5%) |

| Genetic Variant, Suspected Deleterious | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Genetic Variant, Unknown significance | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Genetic Variant, Favor Polymorphism | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| No mutation detected | 56 (78%) | 39 (89%) |

| Not Evaluated* | 2 (3%) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Clinical Tumor Size (cm) | ||

|

| ||

| Median (Range) | 5 (0–15) | 5 (0–14) |

|

| ||

| Baseline node status, n (%) | ||

|

| ||

| Palpable | 31 (43%) | 22 (50%) |

| Non-palpable | 41 (57%) | 22 (50%) |

2 patients in the V/C arm withdrew consent for use of tissue for analysis

Efficacy

VC was eligible to graduate in 3 signatures: HER2-negative, HR-positive/HER2-negative, and triple-negative. It graduated in the triple-negative signature (Figure 2, Table 2). Within HER2− tumors treated with VC, its estimated pCR rate was 33% (95% probability interval (PI) 23–43%), compared to 22% (95% PI 10–35%) in the control arm (Figure 2A). This benefit was concentrated in the graduating signature, triple-negative, where the estimated pCR rate was 51% (95% PI 36–66%) for those receiving VC vs 26% (95% PI 9–43%) in control patients (Figure 2B). The estimated pCR rate in patients with HR+/HER2− breast cancer (Figure 2C) was 14% (95% PI 3–25%) for VC compared to 19% (95% PI 5–33%) for control.

Figure 2.

Estimated pCR Rate for the signatures evaluated for V/C vs. concurrent HER2-negative control.

2A. Probability distribution for all patients with HER2-negative disease; 2B. Probability distribution for patients with TNBC (HR-negative/HER2-negative); 2C. Probability distribution for patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative disease. The red curves represent patients treated with V/C plus paclitaxel followed by AC, and the blue curves represent concurrent controls. The corresponding 95% probability distributions (represented by the width of the curve) are shown for each. The mean of each distribution is the estimated pCR rate.

Table 2.

Final predictive probabilities

| Signature | Estimated pCR Rate (95% Probability Interval) [Equivalent Sample Size N*] | Probability VC is Superior to Control | Predictive Probability of Success in Phase 3 Trial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | Control | |||

| All HER2-negative | 33% (23–43%) [72] |

22% (10–35%) [44] |

91% | 53% |

| HR-positive/HER2-negative | 14% (3–25%) [38.1] |

19% (5–33%) [29.4] |

28% | 8% |

| HR-negative/HER2-negative (triple-negative) |

51% (36–66%) [45.9] |

26% (9–43%) [24.9] |

99% | 88% |

In the triple-negative subtype, the probability that VC is superior to control is 99%, and its probability of statistical success in an equally randomized, phase 3 trial including 300 patients is 88% (Table 2, Figure 2B).

Toxicity

Selected toxicities by treatment arm are summarized in Table 3; all toxicities >5% are listed in Supplemental Table 5. Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicity was increased in VC relative to control, with 71 vs 2% of patients experiencing neutropenia, 1 vs 0% febrile neutropenia, 21 vs 0% thrombocytopenia, and 28 vs 0% anemia. Toxicity was also increased during AC in those who had received VC, with 12 vs 5% febrile neutropenia, as well as an increase in neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. We cannot specifically ascribe the additional toxicities to either carboplatin or veliparib. However, similar toxicities have been observed with the addition of carboplatin to standard of care (e.g. CALGB 4060316).

Table 3.

Selected Toxicities

| VC (n=72) | HER2-negative Control (n=44) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Paclitaxel + VC (n=72) | AC (n=66) | Paclitaxel (n=44) | AC (n=42) | |

|

| ||||

|

ADVERSE EVENTS

| ||||

|

Hematologic, ≥Grade 3, n (%)

| ||||

| Febrile | 1 (1%) | 8 (12%) | 0 (0) | 2 (5%) |

| Neutropenia | 51 (71%) | 16 (24%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (12%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 (21%) | 6 (9%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 20 (28%) | 20 (30%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

Gastrointestinal, ≥Grade 3, n (%) | ||||

| Stomatitis* | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 2 (5%) | 0 |

|

TOXICITY | ||||

|

Dose reductions, n (%)

| ||||

| paclitaxel: 23 (32%) V: 0 C: 34 (47%) |

A/C: 6 (9%) | paclitaxel: 0 | A/C: 3 (7%) | |

|

Early discontinuation, n (%) | ||||

| All | 13 (18%)* | 1 (2%) | 2 (5%)** | 3 (7%) |

| Toxicity | 10 (14%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2(5%) |

| Progression | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 2 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Time from Treatment Consent to Surgery (days) | ||||

| Median (range) | 182 (93 – 232) | 165 (100 – 248) | ||

V: veliparib

C: carboplatin

AC: doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide

7 of the 13 patients who discontinued VC early continued to AC

1 patient who discontinued early continued to AC

Dose reductions and discontinuations

Dose reductions in paclitaxel, although absent in the control arm, occurred in 23 (32%) VC patients. Dose reductions of carboplatin occurred in 34 (48%) patients. During paclitaxel, 13 patients (18%) discontinued therapy early in the VC arm compared to 2 patients (5%) in the control arm. Reasons for discontinuation in the VC arm included toxicity (10), progression (1), and patient preference (2). One patient in the control arm discontinued for toxicity, and one for progression. One patient discontinued AC after 3 cycles for toxicity in the VC arm, and 3 patients discontinued AC early in the control arm (toxicity (2), progression (1)).

DISCUSSION

I-SPY 2 is a new clinical trial model designed to facilitate rapid evaluation of novel therapeutics with identification of biomarkers for definitive subsequent study.6 A goal of I-SPY 2 is to provide a framework for more rapidly and efficiently testing promising agents earlier in the course of disease. Novel agents are added to standard treatment in the neoadjuvant setting for patients who present with tumors at high risk for early recurrence. I-SPY 2 uses adaptive randomization, shared control arms, and allows multiple agents and regimens to be tested in a single trial. It is designed to evaluate tumor subsets for improvement in the likelihood of pCR. An important objective is to reduce the number of patients needed to determine clinical activity of an agent or regimen.4,5

Another goal of I-SPY 2 is to specifically improve the drug development process by establishing a link to the potential success of a future phase 3 trial. Predicting a future trial that has a substantial chance of being successful establishes a high bar that we believe current oncology agents should meet for continued development. Achieving statistical significance in a phase II trial is not enough. The target sample size of 300 for a future confirmatory neoadjuvant trial is consistent with our goal of identifying sufficient signal in I-SPY2 (improvement in pCR rate in the range of 20% over control) such that a moderately sized phase 3 trial in the subtype of interest would be successful. However, there is no requirement in I-SPY2 for a future trial.

Triple-negative breast cancer is aggressive, putting women at risk for early recurrence and death. Those with stage II–III disease who achieve pCR have a marked improvement in outcome compared to women with residual disease.3 For example, the advantage in 3-year event-free survival is about 30%. Identifying promising combinations that have the potential to improve long-term outcomes in this tumor subset is a high priority and is consistent with the I-SPY 2 goal of accelerating the pace of getting successful therapies to market.

Two recent randomized neoadjuvant trials have demonstrated improved pCR rates with the addition of carboplatin in patients with triple-negative disease. The GeparSixto trial randomized 315 patients to receive paclitaxel, non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and bevacizumab, with or without carboplatin.15 Significantly more patients receiving carboplatin achieved pCR (53% versus 37%, p=0.005). CALGB 40603 randomized 443 patients to receive paclitaxel with carboplatin and/or bevacizumab, followed by AC16. Similar to GeparSixto, the addition of carboplatin significantly increased pCR rate (54% versus 41%; p = .0029).

Inhibitors of PARP block DNA single-strand break repair, which can cause the death of BRCA (breast cancer susceptibility genes) deficient cells or potentiate the effects of some chemotherapy agents independent of BRCA status.17 Preclinical models have demonstrated that veliparib, an oral, potent inhibitor of PARP 1/2, significantly potentiates the anti-neoplastic effect of carboplatin.18

The combination of veliparib plus carboplatin graduated with a signature of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), with an estimated probability of pCR 52% vs. an estimated control rate of 26%. Importantly, our trial showed no improvement in pCR rate in HR+/HER2− disease. Our design did not evaluate the individual contributions of veliparib and carboplatin, but instead it evaluated a combination of agents that might have maximum effect. Based on these data, an ongoing phase 3 neoadjuvant trial is comparing the efficacy of standard chemotherapy alone, with carboplatin or with veliparib plus carboplatin in TNBC (NCT02032277).

In both GeparSixto15 and CALGB 40603,16 hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity, dose modifications and early discontinuation were increased with carboplatin. In the I-SPY 2 VC arm we observed rates of toxicities comparable to those observed with carboplatin in CALGB 40603. However, we have no ability to ascribe the higher rates in the VC arm to either carboplatin or veliparib. In the VC arm, despite increased dose reductions and early discontinuation compared to control, estimated pCR rates were higher. The use of VC also impacted toxicity during AC, similar to CALGB 40603, with increased hematologic toxicity. Despite this, all but one patient completed 4 cycles of AC.

A small number of patients had BRCA mutations in I-SPY 2. By design, adaptive randomization increased the number of triple-negative patients assigned to VC in comparison with other experimental arms. This may have enriched the group adaptively randomized to VC for BRCA mutations. DNA repair deficiencies were evaluated in all patients and will be reported separately.

In sum, TNBC patients benefit from VC while patients with HER2−/HR+ tumors do not. The experience of VC in I-SPY2 demonstrates the advantage of an adaptively randomized phase 2 platform trial for matching therapies with biomarker subsets to better inform the design of phase 3 trials. Phase 3 can be more focused and therefore smaller and faster. Future patients stand to benefit but trial participants benefit as well by minimizing exposure to ineffective therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The FNIH (2010–2012) and Quantum Leap (2013-present) were the study sponsors of the I-SPY2 TRIAL which operates as a precompetitive consortia model.

We acknowledge the initial support for the I-SPY 2 TRIAL by the following: The Safeway Foundation, Bill Bowes Foundation, Quintiles Transnational Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, Genentech, Amgen, Inc., The San Francisco Foundation, Give Breast Cancer the Boot, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Inc., Eisai Company Ltd., Side Out Foundation, Harlan Family, The Avon Foundation for Women, Alexandria Real Estate Equities, Inc., and private individuals and family foundations.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in December, 2013

Author Contribution

The first author wrote the first draft of the manuscript, edited by the writing team (LE, DB, AD, OO, MB). All authors made the decision to submit the article for publication and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data. The authors certify that the study as reported conforms with the protocol (see protocol at NEJM.org).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortazar P, Geyer CE., Jr Pathological complete response in neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015;22:1441–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:164–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee D, Haddad T, Albain K, et al. Adaptive trials in the neoadjuvant setting: a model to safely tailor care while accelerating drug development. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4584–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1022. author reply 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMichele A, Yee D, Berry DA, et al. The Neoadjuvant Model is Still the Future for Drug Development in Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker AD, Sigman CC, Kelloff GJ, Hylton NM, Berry DA, Esserman LJ. I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2009;86:97–100. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viale G, Slaets L, Bogaerts J, et al. High concordance of protein (by IHC), gene (by FISH; HER2 only), and microarray readout (by TargetPrint) of ER, PgR, and HER2: results from the EORTC 10041/BIG 03–04 MINDACT trial. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:816–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry DA. Adaptive clinical trials in oncology. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2012;9:199–207. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry DA. The Brave New World of clinical cancer research: Adaptive biomarker-driven trials integrating clinical practice with clinical research. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:951–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry DA. Bayesian clinical trials. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2006;5:27–36. doi: 10.1038/nrd1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prowell TM, Pazdur R. Pathological complete response and accelerated drug approval in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2438–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1205737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff D, Daemon A, Yau C, et al. MammaPrint ultra-high risk score is associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the I-SPY1 trial (CALGB 150007/150012; ACRIN 6657) Cancer Res. 2014;73(24 Suppl):P1-08-1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf DM, Daemen A, Yau C, Davis S, Boudreau A, Swigart L, Esserman L, van ’t Veer KL. Abstract P1-08-01: MammaPrint ultra-high risk score is associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the I-SPY 1 TRIAL (CALGB 150007/150012; ACRIN 6657) Cancer Res. 2014;73 P1-08-1-P1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A, Loibl S, et al. Neoadjuvant carboplatin in patients with triple-negative and HER2-positive early breast cancer (GeparSixto; GBG 66): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:747–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikov WM, Berry DA, Perou CM, et al. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:13–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davar D, Beumer JH, Hamieh L, Tawbi H. Role of PARP inhibitors in cancer biology and therapy. Current medicinal chemistry. 2012;19:3907–21. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y, et al. ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2728–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esserman LJ, Woodcock J. Accelerating identification and regulatory approval of investigational cancer drugs. JAMA. 2011;306:2608–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esserman LJ, Berry DA, Cheang MC, et al. Chemotherapy response and recurrence-free survival in neoadjuvant breast cancer depends on biomarker profiles: results from the I-SPY 1 TRIAL (CALGB 150007/150012; ACRIN 6657) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd. J Wiley & Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.