Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased healthcare worker (HCW) susceptibility to mental illness. We conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the prevalence and possible factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. We searched PubMed, SCOPUS and EMBASE databases up to May 4th, 2022. We performed random effects meta-analysis and moderator analyses for the prevalence of PTSD-relevant symptoms and severe PTSD symptoms. We identified 1276 studies, reviewed 209 full-text articles, and included 119 studies (117,143 participants) with a total of 121 data points in our final analysis. 34 studies (24,541 participants) reported prevalence of severe PTSD symptoms. Approximately 25.2% of participants were physicians, 42.8% nurses, 12.4% allied health professionals, 8.9% auxiliary health professionals, and 10.8% “other”. The pooled prevalence of PTSD symptoms among HCWs was 34% (95% CI, 0.30–0.39, I2 >90%), and 14% for severe PTSD (95% CI, 0.11 - 0.17, I2 >90%). The introduction of COVID vaccines was associated with a sharp decline in the prevalence of PTSD, and new virus variants were associated with small increases in PTSD rates. It is important that policies work towards allocating adequate resources towards protecting the well-being of healthcare workers to minimize adverse consequences of PTSD.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Pandemic, Healthcare workers, Post-stress distress, Mental health

1. Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020). As of September 2nd, 2022, there have been over 601 million reported cases and 6.4 million deaths due to the SARS-CoV2 coronavirus (“WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard,” 2020). This unprecedented high exposure and risk of illness and death pose a long-term mental health burden for the public (Dutheil et al., 2021), and increase the demand for healthcare workers (HCW).

HCWs are facing a variety of unusual challenges. Frontline healthcare workers are dealing with infected patients, putting themselves at an increased risk of being infected, and in turn, putting their loved ones at risk too. Other challenges include shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), changes in work hours, changing hospital practices, increased workload, uncertainty in managing a novel disease, and public un-cooperation to public health safety guidelines (Lai et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2021). The culmination of these factors increases HCW susceptibility to psychological and mental illnesses including, but not limited to, burnout (Antonio A. Lasalvia et al., 2021), anxiety (Sahebi et al., 2021), depression (Sahebi et al., 2021), insomnia (Pappa et al., 2020), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (d'Ettorre et al., 2021).

PTSD is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5-TR) as exposure to a traumatic event, accompanied by symptoms in four categories: intrusion, avoidance, negative changes in cognitions and mood, and changes in arousal and reactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Previous research demonstrates that prior infectious outbreaks such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), 2009 novel influenza A (H1N1), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) increase the prevalence of PTSD in the HCW population (Preti et al., 2020). Recent systematic reviews also highlight increased rates of HCW PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic (Benfante et al., 2020; d'Ettorre et al., 2021; Marvaldi et al., 2021; Preti et al., 2020; Sanghera et al., 2020). However, these studies only include studies from earlier stages of the pandemic, limiting the generalizability of the findings.

In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies to assess current COVID-19 literature using validated survey tools to report the prevalence of PTSD symptoms and severe PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers. We selected studies using validated survey tools because validated survey tools have been used to report rates of PTSD symptoms among various populations. They also provide a specific list of symptoms with certain sensitivity and specificity for PTSD so that participants can easily follow. Furthermore, validated tools provide standardized scores, such as cut-off values for mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, allowing for comparison between studies using the same tools. We planned to include a larger pool of studies so that we would be able to perform several subgroup analyses to better understand which populations are more vulnerable and the global effects of this disease on healthcare workers. Including a larger pool of studies also allows us to report a more up-to-date prevalence due to more published research in later stages of the pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted the study in accordance with the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). We first performed a literature search of the PubMed, SCOPUS and EMBASE databases for COVID-19 related studies that assessed PTSD symptoms from January 1st, 2020 until May 4th, 2022.

We included prospective (randomized trials, quasi-randomized trials) and observational studies. We included all full-text English language studies focused on assessing PTSD symptoms in HCW using the Impact of Events - Revised Scale (IES-R) or the PTSD Checklist for the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (PCL-5) scales during the COVID-19 pandemic. We focused on these two scales because they are the most commonly used during cross-sectional studies and allow for consistency when comparing studies. Healthcare workers included physicians, nurses, allied health professions (non-physician and non-nurse healthcare providers such as physician assistants, pharmacists, laboratory and imaging personnel, rehabilitation professions, medical technologists, occupational and respiratory therapists, and emergency medical technicians), and hospital auxiliary staff (non-healthcare provider staff such as medical students, hospital administrative staff, custodial staff, security, and cafeteria staff). We excluded studies not reporting the prevalence of PTSD symptoms. We excluded all review studies, meta-analyses, case reports, non-English language studies, pediatric studies, letters to editors, unpublished studies, and abstract-only studies. We also excluded studies that used non-validated survey tools such as self-reported qualitative measures, and also excluded studies that did not use the IES-R or PCL-5 to assess PTSD symptoms. We screened the references of included studies for eligible studies, but we did not contact authors for additional details or data. We also scanned the website Retraction Watch website (retractionwatch.com) for potential retracted COVID-related studies that may have been included in our study and we did not find any.

We used Covidence (www.covidence.org; Melbourne, Australia) to manage our search, duplicates, and meta-analysis. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent investigators. A third investigator adjudicated disagreements among investigators. Two agreements allowed an abstract to move to full text screening. Similarly, full texts required agreement between at least two investigators to move to the data extraction stage. Our protocol was approved by Prospero with the registration ID CRD42022330405 (“Post-traumatic stress in healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” n.d.). The senior investigators (Dr. Pourmand) and the Corresponding authors (Dr. Quincy K Tran) have authored over two dozen systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

2.2. Search terms

The search terms used for our search were: (SARS-COV-2 OR COVID-19) AND (IES-R OR PCL).

2.3. Outcome measures

The primary outcome of interest was the prevalence of clinically relevant PTSD symptoms, which are defined as having mild, moderate or severe symptoms among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Definitions of having symptoms in each of these categories are based on the validated tools’ cut-off points, and by definition of the authors of the studies. The secondary outcome was the prevalence of severe PTSD symptoms among HCW during the pandemic.

2.4. Quality assessment / heterogeneity

We evaluated study quality with the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (modified NOS) (Murad et al., 2018) due to the cross-sectional nature of all included studies. The NOS (Wells et al., 2014) has a maximum of 9 points based on 1) selection of the cohort, 2) comparability of the groups, and 3) quality of outcome. High quality is defined by a score of ≥7, moderate quality a score of 4–6, and low quality ≤ 3. The modified NOS has a maximum of 5 points for the same 3 domains, and thus studies are only able to achieve moderate quality due to inherent limitations of observational studies. Two independent researchers completed the modified NOS for each eligible study. Discrepancies were adjudicated as a group. Therefore, inter-raters’ agreement, and Kappa score, was not used to assess interrater agreement. We assessed heterogeneity with the I2 statistic, which measures the total variance of effect size between studies, not due to chance, from the true effect size. We also measured heterogeneity with the Cochrane's Q-statistic, which examines the null hypothesis that all studies would have similar effect with the true effect size.

2.5. Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each eligible study: study size, study duration, study setting, study month, percentages of participants (female, physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, auxiliary staff, HCW with COVID-19 patient contact), survey instrument and cut-offs used to assess clinically relevant PTSD symptoms and severity, total prevalence of PTSD symptoms, and prevalence of PTSD by severity of symptoms. We recorded data in a standardized Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington, USA). Two investigators extracted the data independently. We did not calculate interrater agreement and the Kappa score as any disagreements between 2 investigators were adjudicated and the results were reported per the group's consensus.

2.6. Statistical analysis

We performed random-effects meta-analysis to assess the prevalence of PTSD symptoms among health care workers, as reported by the study authors. We also performed sensitivity analysis, using one-study-removed random-effect meta-analysis of prevalence of PTSD symptoms. The one-study-removed meta-analysis performs a random-effect meta-analysis after systematically removing individual studies one-by-one. This one-study-removed meta-analysis shows if any individual study would heavily affect the overall effect size of the pooled population.

Since we anticipated heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses, using moderator analyses of categorical variables to identify potential sources of heterogeneity, and to compare the prevalence of PTSD symptoms among subgroups. For these subgroup analyses, we used study characteristics such as: regions of the World Health Organization (WHO) of study origin, month of study completion, participant survey setting (inpatient, outpatient, online or mixed settings), and types of survey tool (IES-R or PCL-5). Previous meta-analyses were not able to compare the prevalence of mental health problems due to COVID-19 between different countries due to limited literature, and cited this as a future direction for research once more literature is available because countries are affected differently (Dragioti et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2021). Given our up-to-date search, we anticipated sufficient literature to compare the prevalence between WHO regions to identify potential similarities or differences. We compared prevalence from studies with different months of study completion to contribute to our time-series analysis, which allowed us to draw correlations between changes in prevalence of PTSD symptoms and key events in the pandemic such as the availability of vaccines (Hidaka et al., 2021; Koltai et al., 2022). We compared survey tools because previous studies on the topic found differences between the results from IES-R and PCL-5 (Chen et al., 2022; Qi et al., 2022). Study setting was an important factor to look at because different departments are at varying risks of COVID-19, and hence might be more or less susceptible to PTSD symptoms (Prasad et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2022). We were interested in survey setting because different clinical settings are involved with treating COVID in different ways, and the type of survey tool was important because the IES-R and PCL-5 assess PTSD symptoms differently. Prior to categorizing subgroups, we performed histogram analysis of continuous variables and divided them into subgroups according to their frequency of distributions. A significant difference in prevalence between subgroups was determined with a p-value cutoff of 0.05.

To identify potential patients’ characteristics that may have been associated with the prevalence of PTSD symptoms, we performed exploratory multivariable meta-regression, using continuous variables. The continuous variables, as reported by study authors, were percentages of participants as: female, physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, auxiliary staff, and participants who had contacts with COVID-19 patients. To ensure adequate power for the multivariable regressions, we presented the regressions with the highest possible number of independent variables and the highest possible number of studies. We also conducted a time series analysis to compare the number of global COVID cases with the prevalence of PTSD symptoms for each month. We used the dataset titled “Number of cumulative cases of coronavirus (COVID-19) worldwide from January 22, 2020 to August 28, 2022, by day” from statista.com to obtain data on global COVID cases (“COVID-19 cumulative cases by day worldwide 2022,” n.d.). Monthly PTSD prevalence was obtained from our data extraction.

We did not perform publication bias assessment which estimates whether the missing studies would change an intervention's overall effect size. Our random-effect meta-analysis only measured the prevalence of PTSD symptoms, but not intervention, so publication bias assessment was not applicable (Borenstein, 2019).

We performed our random-effects meta-analysis, one-study-removed meta-analysis, multivariable meta-regression using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (www.meta-analysis.com; Englewood, New Jersey, USA). Any variable with 2-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study description

We identified 1276 studies eligible for the title and abstract screening that matched our search criteria (Fig. 1 ). 209 articles continued to the full text screening stage, of which 119 studies were selected for inclusion in our meta-analysis with a total of 117,143 participants (Table 1A ). All 119 studies were cross-sectional observational studies (Agberotimi et al., 2020; Alah et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2020, 2022, 2021; Alonso et al., 2021; Alshehri and Alghamdi, 2021; Asnakew et al., 2021; Ayalew et al., 2022; Azoulay et al., 2021; Bassi et al., 2021; Benzakour et al., 2022; Bizri et al., 2022; Bonzini et al., 2022; Bulut et al., 2021; Caillet et al., 2020; Caliandro et al., 2022; Carmassi et al., 2022, 2021a, 2021b; Chang et al., 2022; Chan et al., 2021; Chatzittofis et al., 2021; Chaudhary et al., 2021; B. Chen et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Chew et al., 2020; Chowdhury et al., 2021; Civantos et al., 2020a, 2020b; Cortés-Álvarez and Vuelvas-Olmos, 2020; Costantini et al., 2022; Crowe et al., 2022; Demartini et al., 2020; Dobson et al., 2021; Dykes et al., 2022; Ergai et al., 2022; Essadek et al., 2022; Fattori et al., 2021; Geng et al., 2021; Gilleen et al., 2021; Gorini et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Hajure et al., 2021; Hasanvandi et al., 2022; Honarmand et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2021; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2022; J. 2021; Ide et al., 2021; Ifthikar et al., 2021; Ilias et al., 2021; Jang et al., 2021; Jemal et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2020; Jo et al., 2020; Juan et al., 2020; Kiefer et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Lamiani et al., 2021; Lange et al., 2022; Lasalvia et al., 2021; Lasalvia et al., 2022; Laurent et al., 2022; León Rojas et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021, 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Luceño-Moreno et al., 2020; Lum et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Magalhaes et al., 2021; Manh Than et al., 2020; Marco et al., 2020; Marcomini et al., 2021; Martín et al., 2021; Meena et al., 2022; Mehta et al., 2022; Mirzaei et al., 2022; Moderato et al., 2021; Mulatu et al., 2021; Naheed et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021; Ouyang et al., 2022; Pan et al., n.d.; Pappa et al., 2021; Prasad et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2021; Ranieri et al., 2021; Riello et al., 2020; Robles et al., 2021; Rosenthal et al., 2021; Rouse and Regan, 2021; Sachdeva et al., 2021; Sahin et al., 2022; Sarapultseva et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021; Sobregrau Sangrà et al., 2022; Styra et al., 2021; Tebbeb et al., 2022; Topal et al., 2021; Udgiri et al., 2021; Van Wert et al., 2022; Vlah Tomičević and Lang, 2021; Wadasadawala et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Wanigasooriya et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2020; Yitayih et al., 2020; Zakeri et al., 2021; Zara et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). Two studies assessed PTSD at two separate times (Ouyang et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2021), resulting in a total of 121 data points. All studies included the primary outcome of PTSD-relevant symptoms, with 34 studies also including the secondary outcome involving severe symptoms of PTSD. These 34 studies included a total of 24,541 participants who were eligible for our secondary outcome analysis. 83 studies assessed levels of PTSD symptoms in physicians (Table 1B ), with 85 studies investigating nurses, 51 studies including allied health workers, 24 studies investigating auxiliary staff, and 8 studies included participants that were not specified into a category of healthcare workers. 29 studies also did not specify any of their participants into a specific category of healthcare workers (i.e. physicians, nurses, auxiliary staff, allied health staff).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

Table 1A.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author, Country | Month & year of study completion | Length of study, days | Survey tools | Cut-off scores | Survey Settings | Study Quality (NOS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abed Alah, Qatar | December 2020 | 37 | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 Best diagnostic accuracy for PTSD: >33 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Agberotimi, Nigeria | April 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Ali, Ireland | June 2020 | 14 | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 | online | Medium (5) |

| Ali, Kenya | November 2022 | 90 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Ali, Kenya | November 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Alonso, Spain | September 2020 | 124 | PCL-5 | Current PTSD: ≥ 7 | online | Medium (5) |

| Alshehri, Saudi Arabia | NR | NR | PCL-5 | Diagnosis of PTSD: >31 | online | Medium (4) |

| Asnakew, Ethiopia | May 2020 | 60 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

NR | Medium (5) |

| Ayalew, Ethiopia | October 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Azoulay, France | December 2020 | 33 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms: ≥ 26 | online | Medium (5) |

| Bassi, Italy | May 2020 | 18 | PCL-5 | Provisional PTSD Diagnosis: ≥ 33 | Online | Medium (5) |

| Benzakour, Switzerland | June 2020 | 83 | PCL-5 | Diagnosis of PTSD: >33 | online | Medium (4) |

| Bizri, Lebanon | May 2020 | 60 | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: >24 Probable diagnosis of PTSD: >33 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Bonzini, Italy | July 2021 | 60 | IES-R | Probable diagnosis of PTSD: >33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Bulut, Turkey | NR | NR | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Bulut, Turkey | NR | NR | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Caillet, France | April 2020 | 13 | IES-R | Moderate and severe symptoms: > 33 | Inpatient | Medium (5) |

| Caliandro, Italy | May 2021 | 60 | IES-R | Significant PTSD symptoms: > 33 | NR | Medium (4) |

| Carmassi, Italy | June 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Severe PTSD symptoms: > 33 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Carmassi, Italy | May 2020 | 60 | IES-R | PTSD: > 32 | NR | Medium (5) |

| Carmassi, Italy | May 2020 | 60 | IES-R | PTSD Diagnosis: > 32 | NR | Medium (5) |

| Chang, United States | January 2020 | 210 | PCL-5 | PTSD Diagnosis: >31 | online | Low (3) |

| Chan, Singapore | August 2020 | 60 | IES-R | Moderate to Severe PTSD Symptoms: >25 | online | Medium (5) |

| Chatzittofis, Cyprus | May 2020 | 25 | IES-R | Clinically relevant PTSD symptoms: > 33 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Chaudhary, Pakistan | July 2020 | 120 | IES-R | PTSD: >20 | outpatient | Medium (5) |

| Chen, China | March 2020 | 57 | IES-R | High Risk for PTSD: 20 | online | Medium (4) |

| Cheng, China | February 2020 | 24 | PCL-5 | Provisional Diagnosis for PTSD: > 33 | Online | Medium (5) |

| Chen, China | May 2020 | 63 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms: ≥20 | NR | Medium (4) |

| Chew, Singapore & India | April 2020 | 58 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 |

NR | Medium (4) |

| Chowdhary, Bangladesh | December 2020 | 14 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Civantos, United States | April 2020 | 12 | IES-R | Mild: 9‐25 Moderate: 26‐43 Severe distress: 44‐75 Risk for PTSD: ≥ 27 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Civantos, Brazil | May 2020 | 18 | IES-R | Clinical concern: 24–32 Probable PTSD: 33–36 Probable PTSD with immune suppression: 37–88 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Cortés-Álvarez, Mexico | June 2020 | 11 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Constantini, Italy | June 2022 | 7 | IES-R | Probable PTSD: > 50 | online | Medium (5) |

| Crowe, Canada | June 2021 | 61 | IES-R | Some PTSD symptoms: 24 - 32 Probable Diagnosis of PTSD: 33 - 36 Significant PTSD symptoms: < 37 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Demartini, Italy | March 2020 | 7 | IES-R | Some PTSD symptoms: 24 - 32 Probable Diagnosis of PTSD: 33 - 36 Significant PTSD symptoms: < 37 At risk for PTSD: >33 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Dobson, Australia | May 2020 | 28 | IES-R | NR | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Dykes, United Kingdom | July 2020 | 21 | IES-R | Suggestive of PTSD: 12–32 Diagnosis of PTSD (IES-R ≥ 33) |

NR | Medium (4) |

| Ergai, United States | October 2020 | 136 | IES-R | Extreme Distress: ≥33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Essadek, France | April 2020 | 4 | IES-R | PTSD: ≥ 26 | online | Medium (5) |

| Fattori, Italy | December 2020 | 152 | IES-R | PTSD: ≥ 33 | NR | Medium (5) |

| Geng, China | June 2020 | 14 | PCL-5 | PTSD: > 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Gilleen, United Kingdom | May 2020 | 19 | IES-R | High PTSD symptoms: ≥ 26 | Online | Medium (5) |

| Gorini, Italy | May 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: > 37 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Guo, China | February 2020 | 9 | IES-R | Significant Mental Stress: > 34 | online | Medium (4) |

| Hajure, Ethiopia | May 2020 | 15 | IES-R | Subclinical PTSD: 0–8 Mild PTSD: 9–25 Moderate PTSD: 26–43 Severe PTSD: 44–88 PTSD cut-off score: > 33 |

mixed | Medium (5) |

| Hassanvandi, Iran | July 2020 | 61 | PCL-5 | PTSD: ≥33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Honarmand, Canada | September 2020 | 92 | IES-R | PTSD is a clinical concern: 24 - 32 Probable diagnosis of PTSD: ≥33 Scores high enough to suppress immune functioning: ≥37 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Hong, China | March 2020 | 66 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms ≥ 20 | outpatient | Medium (5) |

| Huarcaya-Victoria, Peru | May 2020 | 16 | IES-R | Mild: (9–25) Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Huarcaya-Victoria, Peru | April 2020 | 13 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe (44–88) |

online | Medium (4) |

| Ide, Japan | April 2020 | 14 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms: > 24 | Mixed | Medium (4) |

| Ifthikar, Saudi Arabia | August 2020 | 63 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 24–32 Probable PTSD: 33–36 Severe PTSD: > 37 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Ilias, Greece | June 2020 | 6 | IES-R | PTSD: > 33 | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Jang, Korea | March 2020 | 14 | IES-R | PTSD ≥ 25 | NR | Medium (5) |

| Jemal, Ethiopia | July 2020 | 31 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: ≥ 44 |

Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Ji, China | March 2020 | 15 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Jo, South Korea | May 2020 | 14 | IES-R | High-risk for PTSD: > 25 | Inpatient | Medium (5) |

| Johnson, Norway | April 2020 | 7 | PCL-5 | Subclinical PTSD: > 22 PTSD Diagnosis: > 31 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Juan, China | February 2020 | 14 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

Inpatient | Medium (5) |

| Kiefer, United States | October 2020 | 13 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms: ≥ 24 | online | Medium (5) |

| Kumar, Pakistan | December 2020 | 150 | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 Probable Diagnosis of PTSD: 33 - 36 Diagnosis of PTSD: ≥37 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Lamiani, Italy | October 2020 | 91 | PCL-5 | Mild PTSD: 12 - 30 Probable PTSD: ≥31 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Lange, France | April 2020 | NR | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms ≥ 33 | online | Medium (4) |

| Lasalvia, Italy | May 2020 | 16 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms ≥ 24 | online | Medium (5) |

| Lasalvia, Italy | May 2020 | 15 | IES-R | PTSD symptoms ≥ 24 | online | Medium (5) |

| Laurent, Italy | July 2020 | 34 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms ≥ 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| LeónRojas, Mexico | July 2020 | 60 | PCL-5 | PTSD Symptoms ≥ 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Li, China | NR | NR | IES-R | Subclinical PTSD: 0–8 Mild PTSD: 9–25 Moderate PTSD: 26–43 Severe PTSD: 44–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Liu, China | February 2020 | 6 | IES-R | PTSD Symptoms: >20 | online | Medium (5) |

| Li, China | April 2020 | 3 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: >24 | online | Medium (4) |

| Luceno-Moreno, Spain | April 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Diagnosis of PTSD: > 20 | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Lum, Singapore | September 2020 | 180 | IES-R | At Risk for PTSD: >24 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Luo, China | February 2020 | 14 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–44 Moderately Severe: > 44 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Magalhaes, United States | August 2020 | 90 | IES-R | NR | online | Medium (5) |

| ManhThan, Vietnam | April 2020 | NR | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: >24 | NR | Medium (4) |

| Marco, United States | June 2020 | 32 | PCL-5 | PTSD: >33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Marcomini, Italy | September 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Probable PTSD Diagnosis: >33 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Martin, Spain | NR | 180 | IES-R | Mild: 9‐25 Moderate: 26‐43 Severe: 44‐88 |

online | Medium (4) |

| Meena, India | June 2021 | 120 | IES-R | Clinical Relevance for PTSD: >24 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Mehta, Canada | August 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 24–32 Probable PTSD: ≥ 33 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Mirzaei, Iran | August 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Moderate PTSD: 18–24 Full PTSD: >24 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Moderato, Italy | April 2020 | 14 | IES-R | PTSD: >33 | online | Medium (4) |

| Mulatu, Ethiopia | August 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 Diagnosis of distress: ≥33 |

mixed | Medium (5) |

| Naheed, Pakistan | July 2020 | 180 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

mixed | Medium (5) |

| Nguyen, Vietnam (a) | May 2020 | 20 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: >37 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Nguyen, Vietnam (b) | April 2020 | 22 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 24–32 PTSD: 33–36 Severe PTSD: ≥ 37 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Ouyang, China | June 2020 | 60 | PCL-5 | Significant PTSD: > 33 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Ouyang, China | June 2021 | 365 | PCL-5 | Significant PTSD: > 33 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Pan, China | December 2020 | 60 | PCL-5 | Probable PTSD: ≥ 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Pappa, Greece | June 2020 | NR | IES-R | Mild (24–32) Moderate (33–36) Severe (>37) PTSD of clinical conern: > 24 |

Online | Medium (5) |

| Prasad, United States | April 2020 | 12 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–75 |

Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Qiu, China | February 2020 | 7 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

mixed | Medium (5) |

| Qiu, China | June 2020 | 11 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

mixed | Medium (5) |

| Ranieri, Italy | September 2020 | 210 | IES-R | Concern for PTSD: >33 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Riello, Italy | July 2020 | 11 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 |

Outpatient | Medium (5) |

| Robles, Mexico | May 2020 | 21 | PCL-5 | NR | Online | Medium (5) |

| Rosenthal, United States | NR | NR | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: > 24 Probable Diagnosis of PTSD: > 33 Severe PTSD: >37 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Rouse, Ireland | June 2020 | NR | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: 37–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Sachdeva, India | NR | NR | IES-R | Concern for PTSD: >24 | mixed | Medium (5) |

| Sahin, Turkey | May 2020 | 31 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–43 Severe: 44–88 PTSD: > 24 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Sarapultseva, Russia | September 2020 | 20 | IES-R | Mild: 24–32 Moderate: 33–36 Severe: 37–88 |

outpatient | Medium (5) |

| Shah, Kenya | Nov 2020 | 30 | IES-R | Mild: 9–23 Moderate: 24–32 Severe: >33 |

Mixed | Medium (5) |

| SobregrauSangrà, Spain | October 2020 | 120 | PCL-5 | Severe, suspected PTSD: >30 | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Styra, Canada | July 2020 | 15 | IES-R | Mild: 9–23 Moderate: 24–32 Severe Distress: >33 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Tebbeb, France | May 2021 | 66 | PCL-5 | PTSD: > 38 | outpatient | Medium (5) |

| Topal, Turkey | October 2020 | 300 | PCL-5 | NR | inpatient | Medium (5) |

| Udgiri, India | NR | NR | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: >24 Probable PTSD: > 33 Severe PTSD: > 37 |

online | Medium (5) |

| VanWert, United States | Nov 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: ≥ 22 | online | Medium (5) |

| VlahTomičević, Croatia | May 2020 | 15 | IES-R | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 24–32 Probable PTSD: 33–36 Diagnosis of PTSD: 37–88 |

online | Medium (5) |

| Wadasadawala, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Nepal | July 2020 | 90 | IES-R | Clinical concern for PTSD: >24 PTSD | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Wang, China | Feb 2020 | 10 | IES-R | Distress: >44 | online | Medium (5) |

| Wanigasooriya, United Kingdom | July 2020 | 56 | IES-R | Probable PTSD: > 33 | Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Xia, China | Feb 2020 | 13 | PCL-5 | Probable PTSD: > 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Yang, China | April 2020 | 30 | PCL-5 | PTSD: ≥ 31 | online | Medium (5) |

| Yin, China | Feb 2022 | 5 | PCL-5 | PTSD: > 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Yitayih, Ethiopia | March 2020 | 7 | IES-R | Mild: 9–25 Moderate: 26–44 Severe: >46 |

Mixed | Medium (5) |

| Zakeri, Iran | April 2020 | 30 | IES-R | PTSD: > 33 points | inpatient | Medium (5) |

| Zara, Italy | June 2020 | 38 | IES-R | NR | online | Medium (5) |

| Zhang, China | March 2021 | 33 | IES-R | PTSD: > 33 | online | Medium (5) |

| Zhu, China | Feburary 2020 | 3 | IES-R | PTSD: > 33 | online | Medium (5) |

Abbreviations: IES-R= Impact of Event Scale-Revised, PCL=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, NOS = The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NR = Not Reported.

Table 1B.

Participant demographics from studies included in meta-analysis.

| Author, Country | Study Sample Size, (n) | Symptoms of PTSD, n (%) | Symptoms of PTSD by Severity, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Categories of Participants, n (%) | Contact with COVID-19 Patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abed Alah, Qatar | 394 | 73 (18.5) | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 35 (8.9) Diagnosis of PTSD: 38 (9.6) |

0 (0) | Physician: 101 (25.6) Nurse: 181 (45.9) Allied Health: 112 (28.4) |

280 (71.1) |

| Agberotimi, Nigeria | 382 | 201 (52.6) | NR | 169 (44.2) | NR | NR |

| Ali, Ireland | 472 | 213 (45.13) | NR | 326 (69) | Physician: 19.28 (91) Nurse: 29.03 (137) Allied Health: 194 (41.1) Auxillary: 82 (17.4) |

57.63 (272) |

| Ali, Kenya | 100 | 34 (34) | Mild: 13 (13.5%) Moderate: 3 (3.1%) Severe: 18 (18.8%) |

53 (53) | Physicians: 100 (100) | 66 (66) |

| Ali, Kenya | 171 | 48 (27.1) | Mild: 19 (11.4%) Moderate: 9 (5.4%) Severe: 20 (12.0%) |

120 (70.2) | Nurses 171 (100) | 111 (64.9) |

| Alonso, Spain | 9138 | 1946 (22.2) | NR | 7372 (80.7) | Physician: 2953 (26.4) Nurse: 2746 (30.6) Allied Health: 1841 (22.8) Auxiliary: 1598 (20.3) |

4180 (43.6) |

| Alshehri, Saudi Arabia | 404 | 60 (14.9) | NR | 218 (54) | Physician: 86 (21.3) Nurse: 119 (29.5) Allied health: 111 (27.5) Others: 89 (22) |

192 (47.5) |

| Asnakew, Ethiopia | 396 | 219 (55.1) | Severe: 108 (23.5) | 122 (30.8) | Physician: 77 (19.4) Nurse: 230 (58.1) Allied Health: 89 (22.5) |

NR |

| Ayalew, Ethiopia | 387 | 220 (56.8) | Mild: 50 (12.9) Moderate: 28 (7.8) Severe: 142 (36.7) |

160 (41.3) | Physician: 88 (22.7) Nurses: 197 (50.9) Others: 102 (26.4) |

NR |

| Azoulay, France | 845 | 240 (28.4) | NR | 571 (67.5%) | Physician: 272 (32.2) Nurse: 412 (48.7) Allied Health: 161 (19.1) |

845 (100) |

| Bassi, Italy | 653 | 260 (39.8) | NR | 482 (73.8) | Physician: 189 (28.9) Nurse: 318 (48.7) Allied Health: 146 (22.4) |

261 (40) |

| Benzakour, Switzerland | 25 | 7 (38.9) | NR | 14 (77.8) | Physician: 2 (11.1) Nurse: 9 (50) Allied Health: 4 (22.2) Auxillary: 6 (24) |

13 (72.2) |

| Bizri, Lebanon | 150 | 45 (30.0) | NR | 84 (56) | Post-graduate trainee/clinical fellow/senior attending physician 94 (62.7) Registered nurse 56 (37.3) |

42 (28) |

| Bonzini, Italy | 990 | 192 (19.4) | NR | 693 (70) | Physician: 233 (23.5) Nurse: 416 (42) Allied Health: 63 (6.5) Auxillary: 119 (12) Others: 159 (16) |

446 (45) |

| Bulut, Turkey | 348 | 134 (38.5) | Mild: 109 (31.3) Moderate: 54 (15.5) Severe: 80 (23) |

176 (50.6) | Physician: 190 (54.6) Nurse: 158 (45.4) |

348 (100) |

| Bulut, Turkey | 159 | 87 (45.3%) | NR | 0 (0) | Physician: 102 (64.2) Nurse: 57 (35.8) |

159 (100) |

| Caillet, France | 208 | 52 (25) | NR | 156 (75) | Physician: 17 (8) Nurse: 99 (47.6) Allied Health: 62 (30.3) Auxillary: 25 (12) |

150 (73) |

| Caliandro, Italy | 26 | 9 (33) | NR | 19 (73) | Physician: 9 (34.6) Nurse: 3 (11.5) Allied Health: 9 (36) Auxillary: 5 (19.2) |

NR |

| Carmassi, Italy | 514 | 121 (24.5) | NR | 292 (56.8) | Physician: 183, (35.6) Nurse: 251 (48.8) Other: 80 (15.6) |

514 (100) |

| Carmassi, Italy | 265 | 47 (17.7) | NR | 181 (68.3) | Physician: 85 (32.1) Nurse: 133 (50.2) Allied Health: 47 (17.7) |

NR |

| Carmassi, Italy | 74 | 23 (31) | NR | 47 (63.5) | Physician: 18 (24.3) Other: 56 (75.7) |

46 (62.2) |

| Chang, United States | 31 | 11 (35) | At risk for PTSD: 2 (6.5) Diagnosis of PTSD: 11 (35) |

NR | Physician: 31 (100) | NR |

| Chan, Singapore | 789 | 199 (25.2) | NR | 589 (74.7) | Physician: 305 (8.4) Nurse: 1870 (51.7) Allied health: 677 (18.7) Administrative: 739 (20.4) |

404 (11.2) |

| Chatzittofis, Cyprus | 424 | 62 (15) | Severe: 8 (1.9) | 248 (58) | Physician: 178 (42) Nurse: 103 (24) Allied Health: 75 (18) Other: 68 (16) |

8 (1.9) |

| Chaudhary, Pakistan | 392 | 55 (14) | NR | 176 (45) | Dentist: 254 (64.8) Allied Health: 138 (35.2) |

NR |

| Chen, China | 422 | 302 (71.6) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Cheng, China | 212 | 125 (59) | NR | 103 (48.6) | Physician: 190 (89.6) Allied Health: 22 (10.4) |

212 (100) |

| Chen, China | 597 | 270 (45.2) | NR | 525 (87.94) | Doctor: 41 (6.87) Nurse: 549 (91.96) Other: 7 (1.17) |

322 (54) |

| Chew, Singapore & India | 906 | 67 (7.4) | Moderate to Severe PTSD: 34 (3.8) | 583 (64.3) | Physician: 268 (29.6) Nurse: 355 (39.2) Allied Health: 136 (15) Auxillary: 147 (16.2) |

NR |

| Chowdhary, Bangladesh | 547 | 338 (61.9) | Normal 209 (38.2) Mild 113 (20.7) Moderate 49 (9) Severe 176 (32.2) |

361 (66) | Nurse: 547 (100) | 226 (41.3) |

| Civantos, United States | 349 | 96 (28) | Mild: 14, (32.7) Moderate: 73 (20.9) Severe: 23 (6.6) |

137 (39.3) | Physicians: 349 (100) | NR |

| Civantos, Brazil | 163 | 32 (20) | Clinical concern: 11, (6.7) Probable PTSD: 8 (4.9) Probable PTSD with immune suppression: 24 (14.7) |

42 (25.8) | Physicians: 163 (100) | NR |

| Cortés-Álvarez, Mexico | 462 | 365 (79) | Mild: 149 (32.3) Moderate to Severe: 216 (46.7) |

356 (77.1) | Nurse: 462 (100) | 348 (75.3) |

| Constantini, Italy | 237 | 8 (8.4) | NR | 206 (86.9) | Physician: 237 (100) | 46 (21.9) |

| Crowe, Canada | 425 | 316 (74.4) | NR | 384 (92.5) | Nurse: 425 (100) | NR |

| Demartini, Italy | 123 | 23 (18.7) | NR | 97 (78.9) | NR | 49 (39.9) |

| Dobson, Australia | 320 | 246 (77) | Severe: 5 (1.6) | 248 (78.5) | Physicians: 99 (31) Nurse: 84 (26) Allied Health: 105 (33) Auxiliary: 28 (9) |

121 (38.7) |

| Dykes, United Kingdom | 131 | 37 (28.2) | Suggestive of PTSD: 57 (43.5) PTSD Diagnosis: 37 (28.2) |

97 (74) | Physician: 43 (32.8) Nurse: 69 (52.7) Allied Health: 14 (10.7) Auxillary: 5 (3.8) |

NR |

| Ergai, United States | 388 | 153 (39.4) | NR | 348 (89.7) | Admin 49 (12.6) Ethicists 25 (6.4) Radiology 33 (8.5) RN 212 (54.6) Others (Physician, PA, tech, lab, pharmacy, dietician, PT) 68 (17.5) |

NR |

| Essadek, France | 668 | 246 (36.8) | NR | 500 (74.9) | Auxillary: 668 (100) | 237 (35.5) |

| Fattori, Italy | 550 | 121 (22) | NR | 353 (46) | Physician: 164 (29) Nurse: 222 (40) Allied Health: 89 (16.2) Auxillary: 75 (13.6) |

NR |

| Geng, China | 317 | 34 (10.7) | NR | 221 (69.7) | Physician: 140 (44.2) Nurse: 144 (45.4) Others: 33 (10.4) |

NR |

| Gilleen, United Kingdom | 2773 | 404 (14.6) | Severe: 426 (15.36) | 2365 (85.29) | Physician: 386 (13.9) Nurse: 852 (30.7) Allied Health: 772 (27.8) Auxiliary: 245 (8.8) Other: 499 (18) NR: 19 (0.7) |

1224 (44.1) |

| Gorini, Italy | 650 | 290 (44.6) | Mild:104 (16.1) Moderate: 36 (5.6) Severe: 150 (23.2) |

439 (67.5) | Physicians: 177 (27.2) Nurses: 214 (32.9) Allied Health: 217 (33.4) Auxiliary: 42 (6.5) |

395 (60.8) |

| Guo, China | 610 | 481 (78.9) | NR | 464 (76.1) | Physician: 164 (26.9) Nurse: 446 (73.1) |

610 (100) |

| Hajure, Ethiopia | 127 | 51 (40.2) | Subclinical: 14 (11) Mild: 47 (37) Moderate: 37 (29) Severe: 28 (22) |

41 (32.3) | NR | NR |

| Hassanvandi, Iran | 180 | 93 (51.7) | NR | 129 (71.7) | NR | 122 (67.8) |

| Honarmand, Canada | 849 | 423 (49.8) | Clinical concern: 424 (50) Probable PTSD: 83 (9.8) ≥37: 204 (24) |

NR | NR | NR |

| Hong, China | 102 | 6 (5.9) | NR | 77 (75.5) | Physician: 40 (39.2) Nurse: 54 (52.9) Allied Health: 8 (7.8) |

93 (91.2) |

| Huarcaya-Victoria, Peru | 1238 | NR | Mild: 454 (37) Moderate: 216 (17) Severe: 133 (11) |

848 (68.5) | Auxillary: 1238 (100) | NR |

| Huarcaya-Victoria, Peru | 310 | NR | Mild: 83 (26.8) Moderate: 21 (6.8) Severe: 9 (2.9) |

149 (48.1) | Physician: 310 (100) | 196 (63.2) |

| Ide, Japan | 2697 | 189 (7) | NR | 1995 (74.0) | Physician: 555 (20.6) Nurse: 1045 (38.7) Allied Health: 359 (13.3) Auxillary: 738 (27.4) |

328 (12.2) |

| Ifthikar, Saudi Arabia | 309 | 173 (56) | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 57 (18.4) Probable PTSD: 27 (8.6) Severe PTSD: 89 (29) |

225 (72.6) | Auxillary: 309 (100) | NR |

| Ilias, Greece | 162 | 162 (35) | NR | 125 (77) | Physician: 43 (27) Nurse: 102 (63) Allied Health: 17 (10) |

NR |

| Jang, Korea | 99 | 27 (27.6) | NR | 52 (52.5) | Physician: 5 (5.05) Nurse: 71 (71.7) Allied Health: 23 (23.2) |

22 (22.2) |

| Jemal, Ethiopia | 417 | NR | Mild: 55 (13.2) Moderate: 48 (11.5) Severe: 20 (4.8) |

138 (33.1) | Doctor: 55.5 (13.3) Nurse: 103.8 (24.9) Allied Health: 123.4 (29.6) |

97 (23.3) |

| Ji, China | 723 | NR | Mild: 283 (39.1) Moderate: 66 (9.13) Severe: 34 (4.70) |

449 (62.1) | Physician: 409 (56.6) Nurse: 314 (43.4) |

723 (100) |

| Jo, South Korea | 253 | 54 (21) | NR | 210 (83.0) | Physicians: 27 (10.7) Nurse: 149 (58.9) Allied Health: 35 (13.8) Auxiliary: 35 (13.8) |

NR |

| Johnson, Norway | 1270 | 207 (11.7) | Subclinical PTSD: 305 (17.2) PTSD: 207 (11.7) |

1502 (84.7) | Physician: 178 (10.0) Nurse: 770 (43.4) Allied Health: 402 (31.2) Other: 433 (34.1) |

298 (16.8) |

| Juan, China | 456 | 197 (43.2) | Mild: 148 (32.5) Moderate – severe: 49 (10.7) |

322 (70.6) | Physicians: 195 (42.8) Nurse: 261 (57.2) |

20 (21.2) |

| Kiefer, United States | 558 | 209 (37.5) | NR | 463 (82.9) | Physician: 486 (87.1) Nurse: 15 (2.7%) |

194 (35.5) |

| Kumar, Pakistan | 420 | 236 (56.2) | Clinical concern of PTSD: 75 (17.9) Probable diagnosis of PTSD: 28 (6.7) High enough to PTSD: 133 (31.7) |

184 (43.8) | Auxillary: 420 (100) | NR |

| Lamiani, Italy | 308 | 152 (40) | Mild PTSD: 71 (30) Severe PTSD: 23 (10) |

246 (80) | Administrative 48 (16%) Physician: 48 (16) Nurse: 111 (36) Allied Health: 71 (23.1) Auxillary: 65 (21.1) Other 13 (4%) |

160 (52) |

| Lange, France | 135 | 23 (17) | NR | 78 (59.1) | Allied Health: 135 (100) | NR |

| Lasalvia, Italy | 215 | 77 (35.9) | NR | 109 (50.5) | Physician: 215 (100) | 198 (92.1) |

| Lasalvia, Italy | 2195 | 1181 (53.8) | NR | 1647 (75.3) | Physician: 667 (30.4) Nurse: 783 (35.7) Allied Health: 533 (24.3) Auxillary: 212 (9.7) |

540 (24.6) |

| Laurent, Italy | 2153 | 443 (20.6) | NR | 1614 (75) | Physicians 358 (16.6) Nurse: 1210 (56.2) Allied Health: 424 (19.7) Auxillary: 161 (7.5) |

1365 (63.4) |

| LeónRojas, Mexico | 303 | 59 (19.4) | NR | 303 (100) | Physician: 303 (100) | 120 (39.6) |

| Li, China | 890 | 226 (25.4) | Subclinical PTSD: 93 (10.45) Mild PTSD: 275 (30.9) Moderate PTSD: 296 (33.3) Severe PTSD: 226 (25.4) |

815 (91.6) | Nurse: 890 (100) | 438 (49.2) |

| Liu, China | 1563 | 821 (52.5) | NR | 1293 (82.7) | Physician: 454 (29.0) Nurse: 984 (63.0) Others: 125 (8.0) |

689 (44.1) |

| Li, China | 225 | 71 (31.6) | NR | 162 (72) | Physician: 13 (18.3) Nurse: 53 (74.6) Other: 5 (7.0) |

NR |

| Luceno-Moreno, Spain | 1422 | 805 (56.6) | NR | 1228 (86.4) | Physicians: 143 (10) Nurse: 486 (34.2) Allied Health: 560 (39.4) Other: 233 (16.4) |

1367 (96.1) |

| Lum, Singapore | 257 | 23 (8.9) | NR | 112 (43.6) | NR | NR |

| Luo, China | 2574 | 1772 (68.8) | Mild: 940 (36.5) Moderate: 593 (23) Moderately Severe: 239 (9.29) |

2036 (79.1) | Physician: 783 (30.4) Nurse: 1587 (61.7) Other: 204 (7.93) |

915 (35.5) |

| Magalhaes, United States | 456 | 316 (69.3) | Minimal PTSD Symptoms: 141 (37.7) Moderate PTSD Symptoms: 287 (33.2) Severe PTSD Symptoms: 29 (24.6) |

NR | Physician: 121 (26.5) Nurse: 117 (25.7) Other: 218 (47.8) |

NR |

| ManhThan, Vietnam | 173 | 21 (12.1) | NR | 64 (60.4) | NR | 106 (61) |

| Marco, United States | 1300 | 290 (22.3) | NR | 780 (60) | Physician: 1300 (100) | NR |

| Marcomini, Italy | 173 | 69 (39.9) | NR | 132 (76.3) | Nurse: 173 (100) | NR |

| Martin, Spain | 2089 | 1260 (60.4) | Mild: 477 (22.9) Moderate: 512 (24.5) Severe: 713 (34.2) |

1683 (80.6) | Physician: 812 (39.13) Nurse: 1041 (50.17) Other: 222 (10.7) |

1663 (80.4) |

| Meena, India | 100 | 2 (2) | NR | 92 (92) | Physician: 39 (39) Nurse: 45 (45) Other: 16 |

64 (64) |

| Mehta, Canada | 455 | 140 (30.8) | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 46 (12.2) Probable PTSD: 94 (24.9) |

365/455 (80.2) | Physician: 69 (15.2) Nurse: 279 (61.3) Allied Health: 61 (13.4) Auxillary: 34 (7.47) Other: 8 (1.8) |

346 (76) |

| Mirzaei, Iran | 395 | 342 (86.6) | Moderate PTSD: 28 (7.1) Full PTSD: 314 (79.5) |

288 (72.9) | Nurse: 395 (100) | NR |

| Moderato, Italy | 858 | 450 (52.5) | NR | 724 (84.4) | Physician: 658 (76.7) Nurse: 149 (17.4) Other: 49 (5.7) |

858 (100) |

| Mulatu, Ethiopia | 420 | 243 (57.9) | Mild: 142 (33.8) Moderate: 71 (16.9) Severe: 30 (7.1) |

174 (41.4) | Physician: 115 (27.4) Nurse: 237 (56.4) Allied Health: 68 (16.2) |

296 (70.5) |

| Naheed, Pakistan | 398 | 204 (51.3) | Mild: 62 (15.6) Moderate: 30 (7.5) Severe: 112 (28.1) |

224 (56.3) | Physician: 398 (100) | 186 (46.7) |

| Nguyen, Vietnam (a) | 761 | 261 (34.3) | Mild: 113 (14.8) Moderate: 51 (6.7) Severe: 97 12.7) |

443 (58.2) | NR | 211 (27.7) |

| Nguyen, Vietnam (b) | 349 | 79 (22.6) | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 36 (10.3) PTSD: 16 (4.6) Severe PTSD: 27 (7.7) |

213 (61) | Physician: 199 (57.0) Nurse: 82 (23.5) Other: 68 (19.5) |

227 (65) |

| Ouyang, China | 317 | 31 (10.7) | NR | 221 (69.7) | Physician: 140 (44.2) Nurse: 144 (45.4) Allied Health: 22 (10.4) |

NR |

| Ouyang, China | 403 | 84 (20.8) | NR | 269 (66.7) | Physician: 146 (36.2) Nurse: 243 (60.3) Allied Health: 14 (3.5) |

NR |

| Pan, China | 659 | 90 (13.7) | NR | 597 (90.6) | Physcian: 55 (8.3) Nurse: 573 (86.9) Auxillary: 31 (4.7) |

659 (100) |

| Pappa, Greece | 464 | 199 (42.9) | Mild: 52 (12) Moderate: 22 (5.1) Severe: 125 (28.8) |

319 (68.8) | Physicians: 179 (38.6) Nurses: 200 (43.1) Other: 85 (18.3) |

407 (87.7) |

| Prasad, United States | 347 | 292 (84.1) | Mild: 84 (24.2) Moderate; 128 (36.9) Severe: 80 (23.1) |

315 (90.8) | Nurse: 248 (71.5) Allied Health: 36 (10.4) Auxiliary: 63 (18.2) |

NR |

| Qiu, China | 1717 | 1417 (82.5) | NR | 1436 (83.6) | Physician: 325 (18.9) Nurse: 1226 (71.4) Allied Health: 166 (9.7) |

1717 (100) |

| Qiu, China | 2214 | 590 (26.6) | NR | 1918 (86.6) | Physician: 420 (19) Nurse: 1751 (79.1) Allied Health: 43 (1.9) |

2414 (100) |

| Ranieri, Italy | 69 | 36 (52.6) | NR | 69 (100) | Nurse: 69 (100) | 38 (55) |

| Riello, Italy | 1071 | 902 (84.2) | Mild: 169 (15.8) Moderate: 303 (28.3) Severe: 130 (12.1) |

916 (85.5) | Healthcare Staff: 810 (75.6) Technical Staff: 146 (13.6) Administrative Staff: 115 (10.8)⁎⁎ |

343 (32) |

| Robles, Mexico | 5938 | 1745 (29.4) | NR | 4420 (74.4) | Physicians: 1994 (33.6) Nurses: 1184 (19.9) Allied Health: 1979 (33.3) Auxiliary: 781 (13.2) |

1389 (23.4) |

| Rosenthal, United States | 222 | 88 (39.6) | NR | 204 (92) | Auxillary: 222 (100) | NR |

| Rouse, Ireland | 92 | 24 (26) | NR | 89 (97) | Allied Health: 94 (100) | NR |

| Sachdeva, India | 150 | 95 (63.6) | NR | 54 (36) | Physician: 72 (48) Nurse: 40 (26) Allied Health: 22 (14.6) Other: 16 (10.6) |

90 (60) |

| Sahin, Turkey | 939 | 717 (76.3) | Mild: 416 (44.3) Moderate: 171 (18.2) Severe: 130 (13.8) |

620 (66) | Physicians: 580 (61.8) Nurse: 254 (27.1) Other: 105 (11.2) |

569 (60.6) |

| Sarapultseva, Russia | 128 | 7 (5.5) | Normal: 119 (93) Mild: 5 (3.9) Moderate: 2 (1.6) Severe: 2 (1.6) |

101 (78.9) | Dentist: 43 (33.6) Allied Health: 37 (28.9) Dental auxillary 48 (37.5) |

80 (62.5) |

| Shah, Kenya | 433 | 127 (29.3) | Normal: 283 (69) Mild: 44 (10.7) Moderate: 24 (5.9) Severe: 59 (14.4) |

253 (58.4) | Physician: 243 (56.1) Nurse: 190 (43.9) |

298 (68.8) |

| SobregrauSangrà, Spain | 184 | 43 (23.3) | NR | 156 (84.8) | Physician: 43 (23.4) Nurse: 104 (56.5) Allied Health: 37 (20.1) |

NR |

| Styra, Canada | 3852 | 2698 (70) | Normal: 659 (19.6) Mild: 1013 (30.2) Moderate: 530 (15.8) Severe: 1155 (34.4) |

3245 (84.2) | Physician: 345 (9.4) Nurse: 1256 (34.1) Allied Health: 1034 (28.1) Auxillary: 1243 (28.3) |

2375 (64.6) |

| Tebbeb, France | 373 | 26 (7) | NR | 306 (82) | NR | NR |

| Topal, Turkey | 210 | 80 (38) | NR | 152 (72) | Physician: 86 (41) Nurse: 124 (59) |

NR |

| Udgiri, India | 80 | 80 (100) | NR | 43 (54) | Auxillary: 80 (100) | 45 (56) |

| VanWert, United States | 605 | 135 (22.3) | NR | 475 (78.5) | Social work/MHC/case manager 166 (27.4) Physician/resident/PA/NP 139 (23) Nurse/PCT/RT 283 (46.8) NR 17 (2.6) |

361 (60) |

| VlahTomičević, Croatia | 534 | 176 (33) | Clinical Concern for PTSD: 71 (13.3) Probable PTSD: 32 (5.9) Diagnosis of PTSD: 74 (13.8) |

451 (84.5) | NR | NR |

| Wadasadawala, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Nepal | 758 | 138 (18.2) | NR | 394 (52) | Physician: 294 (38.8) Nurse: 92 (12.1) Allied Health: 279 (36.8) Auxillary: 63 (8.3) Other: 30 (4.0) |

NR |

| Wang, China | 1897 | 186 (9.8) | NR | 565 (82.5) | Physician: 563 (29.7) Nurse: 1334 (70.3) |

NR |

| Wanigasooriya, United Kingdom | 2638 | 646 (24.5) | NR | 2097 (79.5) | Physician: 460 (17.4) Nurse: 775 (29.4) Other: 1403 (53.2) |

720 (27.3) |

| Xia, China | 1728 | 676 (39.1) | NR | 1632 (94.4) | Nurse: 1728 (100) | NR |

| Yang, China | 19,379 | 1008 (5.2) | NR | 15,509 (80) | Physician: 4492 (23.2) Nurse: 8863 (45.7) Other: 6024 (31.1) |

7799 (40.2) |

| Yin, China | 371 | 14 (3.8) | NR | 228 (61.5) | Physician: 67 (18.1) Nurse: 264 (71.2) Other: 40 (10.2) |

371 (100) |

| Yitayih, Ethiopia | 249 | 195 (78.3) | Mild: 22 (8.8) Moderate: 101 (40.6) Severe: 72 (28.9) |

131 (52.6) | Physician: 86 (34.5) Nurse: 130 (52.2) Allied Health: 33 (13.3) |

NR |

| Zakeri, Iran | 185 | 64 (34.6) | NR | 143 (77.3) | Nurse: 185 (100) | 109 (60.2) |

| Zara, Italy | 4550 | 1674 (36.8) | NR | 3540 (78) | Physican: 969 (21.3) Nurse: 1492 (32.8) Allied Health: 1553 (34.1) Auxillary: 536 (11.8) |

NR |

| Zhang, China | 401 | 53 (13.2) | NR | 277 (69.1) | NR | NR |

| Zhu, China | 5062 | 1509 (29.8) | NR | 4304 (85) | Physician: 243 (16.1) Nurse: 1130 (74.9) Allied Health: 136 (9.1) |

2000 (39.5) |

Medical/healthcare staff included: physicians, nurses, healthcare auxiliary staff, physiotherapists, experts in psychiatric rehabilitation, speech therapists and psychologists. Technical staff included: educators, entertainers, mediators, caseworkers, trainers, sociologists, specialized auxiliaries, technicians for the maintenance of the building and cleaning staff. Professional staff included: lawyers and religious assistants.

Ninety-nine (99) studies used the IES-R scale, while only 22 studies used the PCL-5 scale. All studies reported the country in which the study was conducted, study sample size, and the survey tools. All included studies but 8 reported the date of study compilation, and only 1 study did not report the survey setting. 11 studies did not report the length of the data collection period. Study days ranged from one day of data collection to 365 days of data collection. Survey settings included surveys conducted online, inpatient, outpatient, or a mix of all three. Tables 1A and 1B show this data.

3.2. Study quality

The majority of the cross-sectional observational studies were found to be of medium quality, scoring on the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale either 4 or 5 points. One study scored a 3 on the modified NOS indicating low quality, while 23 studies scored a 4, indicating medium quality. All other studies scored a 5 on the modified NOS (Table 1A).

3.3. Patient characteristics

A total of 117,143 healthcare workers across 119 studies were included in our meta-analysis. Of the studies that reported the following data, 87,280 (74.5%) of participants included in our meta-analysis were female. 45,538 (38.9%) participants were in direct occupational contact with COVID-19 patients. Studies focused on the prevalence of PTSD among different types of healthcare professionals including physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, and auxiliary health professionals. Twelve (12) studies did not report the makeup of their study population. Of the included studies that reported study population in more detail, 28,365 (25.2%) were physicians, 48,171 (42.8%) were nurses, 13,903 (12.4%) were allied health professionals, 10,029 (8.9%) were auxiliary health professionals, and 12,103 (10.8%) participants were specified as “other”. Four (4) studies specified the breakdown of their study population by profession, but used different categories that did not allow us to fully separate the data for our analysis (Collantoni et al., 2021; Ergai et al., 2022; Riello et al., 2020; Van Wert et al., 2022). Table 1 summarizes this data.

3.4. Primary outcome

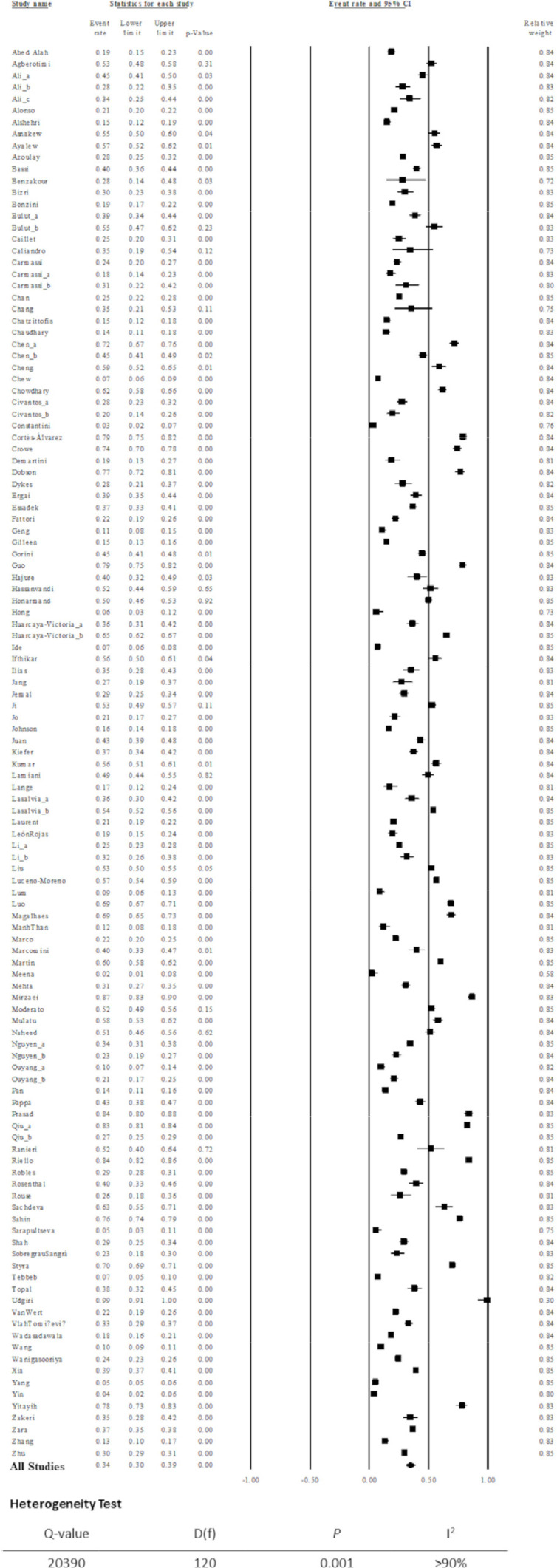

Our primary outcome of interest was defined as the prevalence of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers and was reported by all 119 studies included in our meta-analysis (Fig. 2 A). Approximately 34% of the 117,143 healthcare workers reported by 119 studies displayed PTSD-relevant (Event rate 0.34, 95% CI, 0.30–0.39, I2 = >90%). The percentage of participants with PTSD-relevant symptoms ranged from 2% to 100%. The Cochrane Q value of 20,390, with 120 degrees of freedom [D(f)], which resulted in a P-value < 0.001. This information caused us to reject the null hypothesis, which stated that the effect size of our studies was similar to the true effect size. Additionally, the I2 value was greater than 90%, which indicated that 90% of variance between our studies’ effect size and the true effect size was due to sampling errors.

Fig. 2.

A: Forest Plot from random effects meta-analysis of studies reporting any PTSD among health care workers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

B. Sensitivity analysis of random effects meta-analysis of studies reporting any PTSD among health care workers during the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic. The sensitivity analysis used a one-study-removed method.

The one-study-removed sensitivity analysis results and forest plot are shown in Fig. 2B. The pooled prevalence of PTSD-relevant symptoms persisted between 34%−35% when the random-effects meta-analysis removed each individual study from the pooled population one by one. These results from the sensitivity analysis suggested that our pooled effect size was not affected by any individual study.

3.5. Secondary outcome

Thirty-four (34) studies with 24,541 patients reported our secondary outcome, which was the prevalence of severe PTSD symptoms amongst HCW as defined by the study authors. These studies showed a range of 1.6% to 36.7% of participants reporting severe PTSD symptoms. Our random-effects meta-analysis showed a prevalence of severe PTSD among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic as 14% (Event rate 0.14, 95% CI, 0.11 - 0.17, I2 = >90% (Fig. 3 ). The P-value for the Q statistic was <0.001, which rejected the null hypothesis that our studies’ effect size was similar to the true effect size. Similarly, the I2 was greater than 90%, indicating that more than 90% of variance between our studies and the true effect size was not due to chance and that there was high heterogeneity present.

Fig. 3.

Forest Plot from random effects meta-analysis of studies reporting prevalence of severe PTSD among health care workers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Additionally, we performed a moderator analysis for both the primary outcome (Table 2A ) and the secondary outcome Table 2A) by dividing the studies into subgroups, including WHO region (African Region AFR; Region of the Americas, AMR; Eastern Mediterranean Region, EMR; European Region, EUR; South East Asian Region, SEAR; Western Pacific Region, WPR;), month of study completion (February 2020, March 2020, April 2020, May 2020, June 2020, July 2020, August 2020, September 2020, October 2020, November 2020, December 2020, 2021, 2022), study setting (inpatient, outpatient, mixed, online), and survey tools (IES-R, PCL, other). The I2 was > 90% for all of the subgroups in moderator analysis, indicating that >90% of the variability between the true effect size and our studies’ effect size was by sampling errors, and not by chance.

Table 2A.

Moderator analysis of subgroups using categorical variables for the rates of any PTSD.

| Meta-analysis | Heterogeneity | Between group comparison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator Variables | Number of studies | Any PTSD,% | 95% CI | P-value | Q-value | D(f) | P | I2 | P | |

| Date of Survey Completion | 2020 February | 9 | 0.51 | 0.34–0.67 | 0.92 | 2748 | 8 | 0.001 | >90% | 0.01 |

| 2020 March | 6 | 0.40 | 0.22–0.61 | 0.33 | 223 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 April | 17 | 0.27 | 0.18–0.38 | 0.001 | 4800 | 16 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 May | 20 | 0.38 | 0.28–0.49 | 0.03 | 2216 | 19 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 June | 12 | 0.30 | 0.19–0.44 | 0.01 | 649 | 11 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 July | 11 | 0.36 | 0.23–0.51 | 0.07 | 2720 | 10 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 August | 6 | 0.55 | 0.35–0.74 | 0.61 | 477 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 September | 6 | 0.25 | 0.12–0.44 | 0.01 | 412 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 October | 6 | 0.40 | 0.23–0.61 | 0.36 | 72 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2020 November | 3 | 0.26 | 0.10–0.54 | 0.09 | 7 | 2 | 0.03 | 72% | ||

| 2020 December | 6 | 0.31 | 0.16–0.51 | 0.06 | 449 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2021 | 9 | 0.22 | 0.12–0.37 | 0.001 | 498 | 8 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| 2022 | 2 | 0.04 | 0.01–0.14 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0% | ||

| NR | 8 | 0.47 | 0.30–0.66 | 0.79 | 482 | 7 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| Regions of the World Health Organization | ||||||||||

| AFR | 10 | 0.46 | 0.31–0.62 | 0.64 | 266 | 9 | 0.001 | >90% | 0.10 | |

| AMR | 19 | 0.45 | 0.33–0.56 | 0.37 | 2795 | 18 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| EMR | 10 | 0.41 | 0.26–0.56 | 0.23 | 598 | 9 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| EUR | 44 | 0.31 | 0.25–0.38 | 0.001 | 4874 | 43 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| SEAR | 6 | 0.32 | 0.16–0.54 | 0.1 | 550 | 5 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| WPR | 32 | 0.28 | 0.21–0.36 | 0.001 | 10,005 | 31 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| Survey tools | ||||||||||

| IES-R | 99 | 0.37 | 0.33–0.42 | 0.001 | 122,227 | 98 | 0.001 | >90% | 0.001 | |

| PCL-5 | 22 | 0.22 | 0.16–0.29 | 0.001 | 3638 | 21 | 0.001 | >99% | ||

| Survey settings | ||||||||||

| Inpatient | 5 | 0.32 | 0.16–0.54 | 0.11 | 43 | 4 | 0.001 | >90% | 0.19 | |

| Outpatient | 5 | 0.17 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.001 | 800 | 4 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| Mixed settings | 25 | 0.37 | 0.28–0.47 | 0.013 | 3452 | 24 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| Online | 76 | 0.36 | 0.31–0.42 | 0.001 | 15,460 | 65 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

| NR | 10 | 0.26 | 0.15–0.40 | 0.002 | 408 | 9 | 0.001 | >90% | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; WHO, World Health Organization; AFR, African Region; AMR, Region of the Americas; EMR, Eastern Mediterranean Region; EUR, European Region; SEAR, South East Asian Region; WPR, Western Pacific Region; NR, not reported by the authors; IES- R, Impact of Event Scale - Revised; PCL, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist;.

From subgroup comparisons, there was a significant difference in the effect size of PTSD-relevant symptoms from the study belonging to the EUR, SEAR, and WPR of the WHO regions, compared with other WHO regions (Table 2A). Similarly, studies that used PCL-5 as the primary survey tool reported a lower prevalence of PTSD symptoms (22%, P < 0.005) than studies that used IES-R (37%, P <0.001).

We performed a multivariable meta-regression using patients’ characteristics as reported by studies’ authors (Table 2B ). We used seven variables that were consistently reported by the studies’ authors for our meta-regression, but none of these variables were significantly associated with the prevalence of PTSD-relevant symptoms. In a multivariable meta-regression using the most possible number of studies (23 studies) and number of independent variables (7) (Table 2B), the percentage of physician participants was negatively correlated with the rates of severe PTSD symptoms (correlation coefficient −3.2, 95% CI −5.3 to −1.1, ``-value = 0.001). The percentage of auxiliary workers was also negatively correlated with the rates of severe PTSD (correlation coefficient −5.5, 95% CI −8.5 to −2.4, p-value = 0.001). Three other variables were not significantly associated with the rate of severe PTSD. (Table 2c )

Table 2B.

Multivariable meta-regression to measure participants’ characteristics and association with prevalence with any PTSD from Health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. All listed continuous variables were included in the meta-regression.

| Variables | Number of studies | Corr. Coeff. (95% CI) | P | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of female participants | 70 | −1.3 (−3.2 to 0.61) | 0.18 | >90% |

| Percentage of physician participants | −0.89 (−3.8 to 2.1) | 0.55 | ||

| Percentage of nurse participants | −0.33 (−3.1 to 2.5) | 0.82 | ||

| Percentage of Allied Health Professional | −2.0 (−5.1 to 1.1) | 0.21 | ||

| Percentage of Auxiliary Healthcare Worker | 0.86 (−2.1 to 3.8) | 0.57 | ||

| Percentage of Other types of healthcare worker | −2.3 (−5.3 to 0.65) | 0.13 | ||

| Percentage of workers having contacts with COVID-19 patients | 0.63 (−0.32 to 1.6) | 0.20 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; HCW, healthcare worker; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 2C.

Multivariable meta-regression to measure participants’ characteristics and association with prevalence with Severe PTSD from Health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. All listed continuous variables were included in the meta-regression.

| Variables | Number of studies | Corr. Coeff. (95% CI) | P | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of female participants | 23 | 0.63 (−2.4 to 3.7) | 0.69 | >90% |

| Percentage of physician participants | −3.2 (−5.3 to −1.1) | 0.001 | ||

| Percentage of nurse participants | −2.1 (−4.6 to 0.35) | 0.09 | ||

| Percentage of Allied Health Professional | −5.5 (−8.5 to −2.4) | 0.001 | ||

| Percentage of Auxiliary Healthcare Worker | −2.4 (−5.6 to 0.72) | 0.13 | ||

| Percentage of Other types of healthcare worker | −2.3 (−8.6 to 3.89) | 0.46 | ||

| Percentage of workers having contacts with COVID-19 patients | 0.77 (−0.99 to 2.54) | 0.39 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; HCW, healthcare worker; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

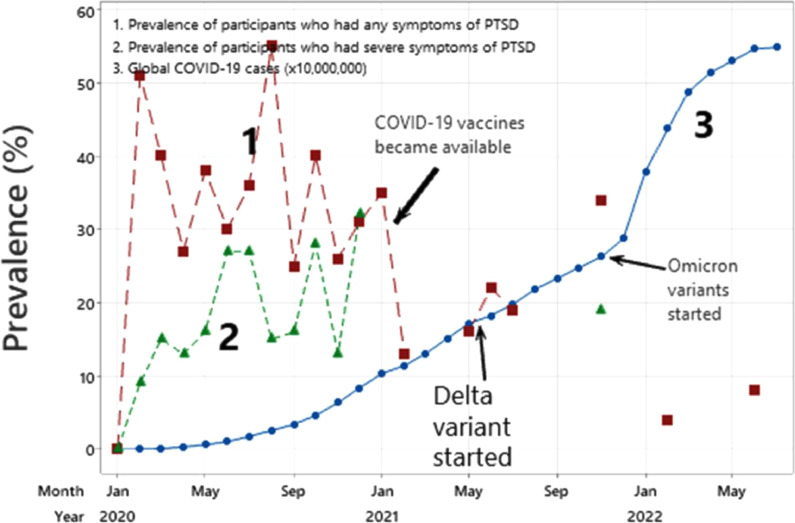

3.6. Time series analysis

Fig. 4A and 4B depict the percentages of participants who reported any PTSD symptoms and severe PTSD symptoms with both the total monthly global cases of COVID-19 and new monthly global cases of COVID-19, respectively. The percentages of participants reporting PTSD-relevant symptoms appeared to parallel the rise of global cases until January 2021. After January 2021, which marks the beginning of COVID-19 vaccines being available, the prevalence of PTSD symptoms sharply declined. The prevalence of PTSD rose again with the introduction of the Delta and Omicron variants, but did not return to the peak rates in August 2020.

Fig. 4.

A. Time series analysis depicting the prevalence of participants who reported any or severe PTSD symptoms and the monthly global cases of COVID-19.

Legend: The Dashed Red Line with Squares (Line 1) indicates the prevalence of participants who had any symptoms of PTSD over the course of the pandemic. The Dashed Green Line with Triangles (Line 2) indicates the prevalence of participants who had severe symptoms of PTSD. The Solid Blue Line with Dots (Line 3) indicates the global number of COVID-19 cases as a factor of 10 million. We mark key events during the pandemic with a solid arrow. Key events include the availability of COVID-19 vaccines, the start of the Delta variant, and the start of the Omicron variant.

B. Time series analysis depicting the percentages of participants who reported any or severe PTSD symptoms and the monthly global NEW cases of COVID-19.

Legend: The Solid Blue Line with Dots (Line 1) indicates the prevalence of participants who had any symptoms of PTSD over the course of the pandemic. The Dashed Red Line with Triangles (Line 2) indicates the prevalence of participants who had severe symptoms of PTSD. The Dashed Green Line with Diamonds indicates (Line 3) the global number of new COVID-19 cases as a factor of 1 million. We mark key events during the pandemic with a solid arrow. Key events include the availability of COVID-19 vaccines, the start of the Delta variant, and the start of the Omicron variant.

4. Discussion

Our meta-analysis indicates that the pooled incidence of PTSD symptoms in the healthcare worker population during COVID-19 is 34% (121 data points), and 14% for severe PTSD symptoms (34 studies). Additionally, we included enough studies to perform moderator analyses for different subgroups including WHO region of study setting and month of study completion.

Trauma, as defined by the DSM-5 criteria, is “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (Weathers, 2018). Under this criteria, stress-inducing events that do not involve an immediate threat to life or physical injury are not considered trauma (Nemeroff and Marmar, 2018). However, several previous studies have shown how stressful events that fall outside of this narrow definition of trauma can still induce symptoms of PTSD (Cordova et al., 2017; Galea et al., 2008; Gold et al., 2005). The COVID-19 pandemic also falls out of this definition, but has been suggested to be considered a traumatic stressor for several reasons including the uncertainty of the pandemic's timeline, fear of future sickness and death events whether it be for themselves or loved ones, media coverage, and more (Bridgland et al., 2021). Although healthcare workers are regularly exposed to death and injury during their typical jobs, the pandemic introduces additional elements of uncertainty, risk to personal safety, seeking co-workers to fall ill, and higher patient volume. Literature has also shown a strong correlation between risk perception and PTSD, including during the pandemic (Geng et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2021). Nevertheless, it is important to note that broadening the definition of PTSD may have unintended consequences. For example, it has been suggested that broadening the definition of trauma can result in increased vulnerability because it can affect how a person interprets a stressful event (Jones and McNally, n.d.).

The prevalence we reported was higher than those reported in previous meta-analyses assessing the prevalence of PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers during COVID-19 (Civantos et al., 2020b; Falasi et al., 2021; Marvaldi et al., 2021; Salehi et al., 2021; Sanghera et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021). Prior reported prevalence typically ranged from 20% to 26.9%. This may be because we included a larger pool of studies, or our meta-analysis included studies over a span of more than two years from the beginning of the pandemic. Prior to our analysis, the most comprehensive meta-analysis on the subject only included 20 studies and concluded their search by August 2020 (Yuan et al., 2021). Symptoms of PTSD can typically surface months after the traumatic experience. Therefore, our findings are clinically important because even after COVID-19, healthcare workers will experience high rates of psychological distress. PTSD among healthcare workers is associated with increased medical errors, reduced productivity, compassion fatigue, all of which contributes to lower quality of care (Gates et al., 2011; Karanikola et al., 2015). Prior meta-analyses on the topic also either did not focus exclusively on the COVID-19 pandemic or exclusively on healthcare workers, limiting their subgroup analysis specific to PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers during COVID-19. The prevalence we reported was also higher than those reported in meta-analyses of PTSD among healthcare workers during past outbreaks and public health emergencies (Cheng et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). This may be due to the higher incidence rate of SARS-2-CoV which contributed to insufficient PPE and high patient volume, increased media coverage and misinformation, and fear due to increased risk and uncertainty of infecting others (Billings et al., 2021; Greene et al., 2021; Norful et al., 2021).

A meta-analysis performed by Salehi et al. examined the prevalence of PTSD-relevant symptoms among the general population from all previous coronavirus outbreaks (SARS-CoV, MERS, SARS-CoV-2) between November 01, 2012 until May 18, 2020 (Salehi et al., 2021). This study included 36 studies and reported an overall rate of PTSD for all studies (general population, healthcare workers, patients/survivors, etc.) at 18% (95% CI 0.15–0.20). The prevalence of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers was 18% (95% CI 13%−24%, I2 = 97%), whereas the prevalence of PTSD among patients was 29% (95% CI 18%−39%, I2 = 96%). On the other hand, the rate of the general population was the lowest at 12% (95% CI 8%−16%, I2 = 98%) during these outbreaks. The rate of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers from Salehi was lower than ours because the authors only included COVID-19 studies up to May 2020, when the full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was still unfolding and not totally reported in the literature. Although our studies are not comparable, these results from Salehi et al. provided interesting insights. Healthcare workers are more susceptible to higher rates of PTSD than the general population during previous coronavirus outbreaks. Therefore, a similar trend would be observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We noticed a significant difference in the outcome observed between studies that used the IES-R scale and studies that used the PCL-5 scale, with studies using the PCL-5 scale reporting a lower prevalence of PTSD. This suggests that future studies should be standardized to one tool. While both tools are validated, the IES-R is not used to diagnose PTSD under the revised DSM-5 criteria and may not accurately reflect rates of PTSD, while the PCL-5 can provide a provisional diagnosis and is recommended for use by the National Center for PTSD (National Center for PTSD, n.d.; Umberger, 2019). For these reasons, we suggest that future studies only use PCL-5 to assess the prevalence of PTSD among healthcare workers in a more standardized manner. However, a majority of studies used the IES-R. Additionally, despite the use of validated tools, there was some variability in the cut-offs used by authors. This strongly suggests the need for establishing universal cut-offs to standardize data collection and comparisons for prevalence studies.

There were significant differences in prevalence rates between WHO regions. While further research is needed to explain this finding, we hypothesize that this might be due to differences in staff-case ratio, access to resources and PPE, politicization of the pandemic, the public's health behavior, and other factors. Few studies reported the specialties of study participants, whether or not the participants had any prior psychiatric conditions, or the outcome stratified by exposure to COVID-19. This barred us from conducting moderator analyses for these subgroups. These data would have contributed to a better understanding of risk factors for PTSD, and hence another suggestion for future studies. It is also important that studies are conducted even after the end of the pandemic to understand how PTSD may persist and to better guide interventions and allocation of resources to healthcare worker wellness.

Our findings demonstrate the need for interventions and policies that lower the risk of PTSD among healthcare workers. It is important that health policy focuses on ensuring the availability and accessibility of PPE (Carmassi et al., 2020; Kisely et al., 2020). Hospitals should also ensure that counseling and peer support are widely available with low barriers of access, and that interventions take a trauma-informed approach to ensure that unwanted triggers are not activated (d'Ettorre et al., 2021). Regular screening for PTSD among healthcare workers can identify those at-risk and affected, ensuring timely and targeted interventions. Our time-series analysis showed that the introduction of COVID−19 vaccines was correlated with a decrease in the prevalence of PTSD, hence a protective factor. The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic among HCWs will remain long-after the pandemic ends in the forms of PTSD. Researchers should continue assessing the prevalence of PTSD as the pandemic evolves and well beyond the pandemic as well to better understand vaccine rollout and other factors affect the prevalence.

4.1. Limitations

Our study has several limitations which present future directions for studies. Although we utilized very broad search terms that returned a large eligible number of studies, due to the explosive number of publications during the COVID-19 pandemic and because we did not search other databases such as Google Scholar, our search might have missed other articles. All included studies had a moderate or high risk of bias due to their cross-sectional survey format. Additionally, we excluded all studies that used non-validated surveys to measure PTSD symptoms. This may affect the pooled prevalence we found in our analysis. Despite several subgroup analyses to identify potential sources of heterogeneity, there was high heterogeneity among the studies we included in our meta-analysis, which may affect the generalizability of the finding. Despite the use of validated tools, there was still variability in author's definitions of cut-offs. We also included different categories of healthcare workers from a variety of clinical settings, different time periods of the pandemic, different practice settings, and different levels of experience. This was expected because COVID-19 was a global pandemic that affected several countries at various degrees.

We cannot know with certainty that the PTSD symptoms were or were not driven by other mood disorders because we did not control for other mood disorders. Approximately half of people with PTSD are also affected by major depressive disorder (MDD), and it has been suggested that this is a reflection of overlapping symptoms. It is also important to note that studies conducted on the topic prior to the pandemic also found the presence of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers (DeLucia et al., 2019; Joseph, 2021). Future research should seek to determine what proportion of the prevalence of PTSD symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic is due to the pandemic, and how much is pre-existing, perhaps by using methods such as difference-in-difference analysis.

Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis suggested a high prevalence of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic among studies using validated survey tools. It is important that policies work towards allocating adequate attention and resources towards protecting the well-being of healthcare workers to minimize the adverse consequences of PTSD, and in turn, ensure higher quality of care for patients.

Author statements

No ethical approval was needed because only data from previous published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators was retrieved and analyzed.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sanketh Andhavarapu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Isha Yardi: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Vera Bzhilyanskaya: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Tucker Lurie: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mujtaba Bhinder: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Priya Patel: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Ali Pourmand: Writing – review & editing. Quincy K Tran: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Project administration, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114890.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Agberotimi S.F., Akinsola O.S., Oguntayo R., Olaseni A.O. Interactions between socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes in the Nigerian context amid COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alah M.A., Ali K., Abdeen S., Al-Jayyousi G., Kasem H., Poolakundan F., Al-Mahbshii S., Bougmiza I. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on health care workers working in a unique environment under the umbrella of Qatar Red Crescent Society. Heliyon. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S.K., Shah J., Du K., Leekha N., Talib Z. Mental health disorders among post graduate residents in Kenya during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S.K., Shah J., Talib Z. COVID-19 and mental well-being of nurses in a tertiary facility in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2021 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]