Abstract

Superantigens stimulate T-cell-receptor Vβ-selective T-cell proliferation accompanying the release of cytokines, which may eventually protect the host from microbial infections. We investigated here whether superantigens can rescue the host from lethal bacterial infection. Mice were pretreated with Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB) 1 and 2 days before bacterial infection, and the mortality of infected mice was assessed. SEB pretreatment protected mice from lethal infection with Listeria monocytogenes but not from lethal infection with Streptococcus pyogenes. This enhanced protection was also observed upon pretreatment with recombinant streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A. Furthermore, L. monocytogenes-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) due to type 1 helper T (Th1) cells and the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells were significantly enhanced after SEB administration and bacterial infection. Depletion of either CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells in SEB-pretreated mice completely abolished this protection. This phenomenon was ascribed to the elimination of L. monocytogenes-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). It was found that CD4+ T cells contributed to the induction of the CTL populations. Furthermore, SEB pretreatment of heat-killed L. monocytogenes-immunized mice enhanced the protection from challenge of L. monocytogenes. Taken together, these results indicated that administrations of superantigens protected mice from infection with L. monocytogenes, which was dependent on the enhanced L. monocytogenes-specific CTL activity in the presence of CD4+ T cells, and superantigens exhibited adjuvant activity in the immunization against intracellular pathogens.

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are known to produce 20- to 30-kDa exotoxins, e.g., staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SPEA). These toxins cause lethal toxic shock in humans and animals (3, 15, 18, 24). They elicit a variety of pathophysiological activities and activate T cells in a T-cell-receptor (TCR) Vβ-specific manner. They also bind directly to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and activate T cells bearing one or few types of the variable region of β chain (Vβ) of the TCR, causing the release of cytokines. By this mechanism, these exotoxins stimulate 5 to 30% of T cells (3, 24) and are termed superantigens (54).

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive and facultative intracellular bacterium that causes meningitis, sepsis, and abortions (19). The virulence factor of L. monocytogenes is listeriolysin O (LLO), which destroys the phagocytic vacuoles, allowing endocytosed organisms to be released into the cytoplasm of their target cells, where they proliferate. Protection against L. monocytogenes infection is mediated by innate and adaptive immunologic mechanisms (46). Neutrophils (7), macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells (10), and γδ-T cells (16) are responsible for the innate immunity in the early phase of infection, while adaptive immunity against L. monocytogenes depends on αβ-T cells. Among these immune cells, class I MHC-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) found in the spleen, liver, and peritoneum seem to play critical roles in conferring protective immunity. The LLO and murein hydrolase p60 protein secreted from L. monocytogenes are targets for the CD8+ CTLs, and LLO- or p60-specific CD8+ CTL clones mediate protective immunity against L. monocytogenes in vivo (13, 38, 39).

After stimulation of T cells with superantigens, various kinds of cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12 are secreted (6, 28). Exceeding secretion of TNF-α in a host may result in lethal toxic shock (31, 32). However, moderate secretion of cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1 is necessary to induce innate immune responses for protection of host from bacterial infection (6, 34). Furthermore, superantigen exposure significantly enhanced the T-cell-dependent host response to bacterial antigens in the in vitro coculture system (30). In this regard, Nichterlein et al. (37) reported that pretreatment with SEB increased the clearance of L. monocytogenes, which suggests that pretreatment of the host with low levels of superantigens may help to protect against bacterial infections. However, it is not yet known whether pretreatment of host with low levels of superantigens could protect against lethal L. monocytogenes infection.

In this study, we investigated whether the administration of superantigens offered protection from lethal bacterial infections and, if so, which type of host defense mechanism was responsible.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, mice, and cell lines.

L. monocytogenes EGD was provided by M. Mitsuyama (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). S. pyogenes SSI-1 (M3) was an isolate from a Japanese patient with severe invasive fasciitis and was provided by T. Murai (Toho University, Tokyo, Japan). L. monocytogenes was grown overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C. S. pyogenes was grown for 6 h in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories) at 37°C. After being washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), bacterial cells were resuspended in PBS for a mortality test in mice. Female BALB/c mice (H-2d, 6 to 10 weeks old) were purchased from Clea Japan, Inc. (Osaka, Japan). The 50% lethal doses (LD50s) of L. monocytogenes and S. pyogenes in mice were found to be 104 CFU and 4 × 104 CFU, respectively. Mouse macrophage cell line J774A.1 (H-2d) (42) and mastocytoma cell line P815 (H-2d) (40) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10% fetal calf serum, l-glutamine, β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml).

MAbs, toxins, and peptides.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to CD3ɛ, CD4, and CD8 were prepared from hybridoma cell lines 145-2C11 (27), GK1.5 (55), and 2.43 (45), respectively. These hybridoma cells were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into BALB/c nu/nu mice (Charles River Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and MAbs were purified from the ascites fluids by using MabTrap GII (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Purified rabbit antibody to asialoganglioside GM1 (AsGM1) was purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan). Control rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated MAbs were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.). SEB was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Recombinant SPEA (rSPEA) was obtained according to the method of Fagin et al. (11). Synthetic peptides GYKDGNEYI and KYGVSVQDI corresponding to LLO (positions 91 to 99 [91-99]) (39) and p60 (positions 217 to 225 [217-225]) (38), respectively, were custom-made by Sawady Technology (Tokyo, Japan). These peptides were dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −20°C until use.

Bacterial infection, pretreatment with superantigens, and depletion of NK or T-cell subsets in vivo.

To examine mortality after infection with test organisms, mice were given 106 to 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes intravenously (i.v.) or 106 CFU of S. pyogenes i.p., while others received i.p. treatment twice, 1 and 2 days before L. monocytogenes infection. For depletion of T cells or NK cells in vivo, mice were injected i.v. with MAbs specific for CD3, CD4, and CD8 (each at 600 μg/mouse) or with purified antibody specific for AsGM1 (50 μl/mouse) 18 h before the bacterial infection. We assessed the depletion of T or NK cells in the spleen 12, 24, and 120 h after MAb injection, by the staining of spleen cells with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 MAb, PE-conjugated anti-CD4 MAb, PE-conjugated anti-CD8 MAb, or PE-conjugated anti-AsGM1, and cellular population analysis was done with a flow cytometer (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Cytokine assay.

Sera were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min, and the samples were stored at −70°C until use. Cytokine assays were performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a Cytoscreen ELISA KIT (Bio Source International, Camarillo, Calif.).

Phagocytic assay of macrophage to L. monocytogenes.

Spleen cells (108 cells) from mice were suspended in 10 ml of complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 20% fetal calf serum and then poured into a plastic petri dish (10 cm in diameter; Becton Dickinson) and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 2 h in air with 5% CO2. After incubation, adherent macrophages were harvested, and 5 × 106 cells were suspended in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium. L. monocytogenes (5 × 106 CFU) were suspended in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing 20% normal mouse serum and incubated for 10 min at 37°C, and the macrophage suspensions (1 ml) and L. monocytogenes suspensions (1 ml) were then mixed. The mixtures and L. monocytogenes suspensions were rotated at 37°C for 2 h in a humidified incubator in air with 5% CO2. The mixtures (100 μl) and L. monocytogenes suspension (50 μl) were plated on BHI agar plates, and colonies were counted after incubation overnight at 37°C. The percent clearance of L. monocytogenes is presented as 100% × (CFU in 50 μl of L. monocytogenes suspension − CFU in 100 μl of the mixture)/(CFU in 50 μl of L. monocytogenes suspension).

DTH.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) was assessed as described by Tsukada et al. (50) with some modifications. Forty mice were divided into four groups (10 mice per group): I to IV. The group I mice were not treated. Mice in groups III and IV were infected i.v. with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Mice in groups II and IV were treated i.p. with SEB (10 μg) twice. All mouse spleens were harvested 7 days after infection, and T cells were separated and purified using a nylon wool column (20). The T cells (5 × 106 cells) and heat-killed L. monocytogenes (HKL; 5 × 107 CFU) were suspended in 25 μl of PBS. Another 20 mice were divided into four groups (five mice per group) labeled A to D. The suspensions of HKL and T cells from groups I to IV (25 μl) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the left hind footpad of groups A to D, respectively. In the right hind footpad, PBS (25 μl) was injected s.c. as a control. Thickness of the left and right footpads was measured with a vernier caliper (Mitsutoyo, Tokyo, Japan) 24 h after injection.

Generation of effector T cell.

Effector T cells were obtained for CTL assay as reported previously by Bouwer and Hinrichs (4). Mice were infected i.v. with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. At 5 days postinfection, spleen cells (108 cells/50 ml) were stimulated with 1 μg of concanavalin A (ConA; Wako)/ml for 72 h at 37°C in air with 5% CO2. T cells were harvested by Percoll gradient centrifugation and nylon wool column purification and were used as effector cells for CTL assay. Depletion of T-cell subsets from ConA-stimulated spleen cells in vitro was performed according to the method of Davignon et al. (9). The ConA-stimulated spleen cells (107 cells) were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with MAbs to CD4 or CD8 (each at 100 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C. Rabbit complement (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, N.Y.) was then added to the reaction mixture for 1 h at 37°C. Lysed cells were next removed by Percoll gradient centrifugation.

L. monocytogenes-specific CTL assay.

J774A.1 cells were deposited at 105 cells/well in a 48-well culture plate (Becton Dickinson) in 250 μl of RPMI 1640 medium without antibiotics and incubated at 37°C for 1 day in a humidified incubator with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The target cell monolayers were infected with L. monocytogenes at a multiplicity of infection of 5 for 60 min at 37°C. After the monolayers were washed with PBS at 37°C three times, they were covered with 250 μl of RPMI 1640 medium and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The monolayered cells were labeled with 10 μCi of 51Cr (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.)/well for 60 min and washed with PBS at 37°C four times. Effector T cells in a 250-μl volume were added into the 48-well culture plates at an effector/target ratio of 30 to 3. Cytotoxicity for 4 h was assayed by the release of 51Cr from the target J774A.1 cells in the half volume of supernatants. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows: 100 × (experimental counts per minute [cpm] − spontaneous cpm)/(maximum cpm − spontaneous cpm). Spontaneous cpm represents the radioactivity released from target cells only, and maximum cpm represents entire radioactivity released from target cells lysed with 1 N HCl.

Listeria epitope-specific CTL assay.

P815 cells (5 × 106 cells) were labeled with 250 μCi of 51Cr/0.5 ml for 60 min and washed with PBS. These labeled cells (104 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10−6 M peptide LLO (91-99) or p60 (217-225) and were incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The peptide pulsed target P815 cells (100 μl) were added to 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Becton Dickinson) at 104 cells/well and were used as target cells. Effector T cells in a 100-μl volume were added at an effector/target ratio of 30 to 1. The cytotoxicity was assayed, and the percent specific lysis was determined as described above.

ELISPOT assay.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was performed to assess the number of IFN-γ-producing cells in the spleen of L. monocytogenes-infected mice as described by Vijh and Pamer (52). Briefly, Multiscreen 96-well HA plates (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were covered overnight with anti-mouse IFN-γ MAb (R4-6A2; PharMingen). The effector T cells (105 cells) and 1 μM LLO (91-99) or p60 (217-225) labeled P815 cells (105 cells) were added in a total volume of 200 μl of RPMI 1640 medium. Membranes in the bottom of the wells were incubated for 30 h at 37°C in the air with 5% CO2 and washed with sterile PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Wako) (PBS-T) three times. The membranes were incubated overnight with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ MAb (XMG1.2; PharMingen) at 4°C. After five washes with PBS-T, the membranes were developed with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (1:400 dilution; Sigma) and AEC substrated buffer (Moss, Inc., Pasadena, Md.). The spots that appeared were then counted under a dissecting microscope.

Protection against L. monocytogenes infection in immunized mice.

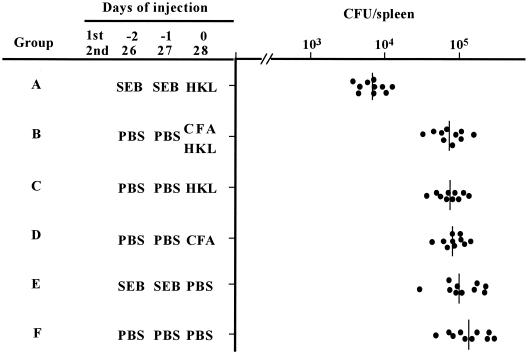

Sixty mice were divided into six groups: A to F. The group A mice were injected i.p. with SEB (10 μg/200 μl of PBS) on two successive days and were immunized s.c. with HKL (5 × 107 cells/100 μl of PBS). Group B mice were immunized by s.c. injection of an emulsified mixture (200 μl) of HKL suspension (5 × 107 cells/100 μl of PBS) and 100 μl of complete Freund adjuvant (CFA; Difco Laboratories). Group C mice (10 mice) were immunized s.c. with the HKL suspension, while group D mice (10 mice) were injected s.c. with an emulsion of PBS (100 μl) and CFA (100 μl). Group E mice (10 mice) were injected s.c. with PBS (100 μl) and were injected i.p. with SEB (10 μg/200 μl of PBS) twice 2 and 1 days before the s.c. PBS injection. Group F mice (10 mice) were injected s.c. with PBS (100 μl). Mice of group B, C, D, and F were injected i.p. with PBS (200 μl) twice 2 and 1 days before the immunization. Booster injections with SEB (10 μg/200 μl of PBS), PBS (100 μl), CFA (100 μl), and HKL (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl of PBS) into mice in groups A to F, as well as primary injections, were administered 26, 27, and 28 days after the initial immunization. At 63 days after the initial immunization, mice of each group were infected i.v. with L. monocytogenes (104 CFU). To count the number of L. monocytogenes organisms, the spleens were dissected and homogenized in PBS. Several dilutions of the spleen cell suspensions were plated on BHI agar plates, and colonies were counted after incubation overnight at 37°C.

Statistical evaluations.

The Mantel-Cox test was done with StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Cary, N.C.) to determine the significant difference in the mortality experiments. To analyze the data from other experiments, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was done. All conclusions were based on a significance level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Protection of mice from lethal bacterial challenge by pretreatment with SEB.

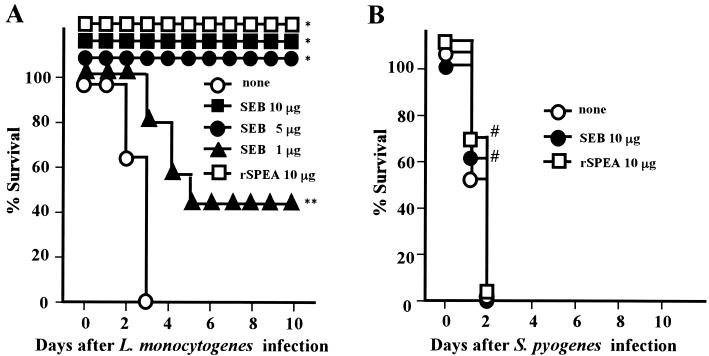

Mortality of mice given SEB was assessed for 10 days after the lethal infection with L. monocytogenes. Administrations of SEB (5 to 10 μg/mice) protected all mice from lethal challenge of 106 CFU (= 100 × LD50) of L. monocytogenes organisms. However, infection of mice with 106 CFU (= 25 × LD50) of S. pyogenes organisms resulted in the death of the mice infected (Fig. 1). Pretreatment of mice with SEB (10 μg/mouse) protected them from infection with L. monocytogenes at up to 3 × 106 CFU (= 300 × LD50) (data not shown). However, treatment of mice with SEB 1 and 2 days after infection with 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes organisms did not show any protection compared to nontreated mice (data not shown). It was also shown that a recombinant streptococcal superantigen, rSPEA, protected all mice from lethal infection with L. monocytogenes but not from lethal infection with S. pyogenes (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on the infection with L. monocytogenes or S. pyogenes in mice. Groups of 15 BALB/c mice were pretreated i.p. with SEB or rSPEA twice 1 and 2 days before infection with 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes (A) or 106 CFU of S. pyogenes SSI-1 (B). The mortality of mice was assessed for 10 days after the infection. None, no SEB pretreatment. ∗, P < 0.0001; ∗∗, P = 0.0088 compared to none in panel A; #, P > 0.5 compared to none in panel B.

Effect of the secretion of cytokines after pretreatment with SEB.

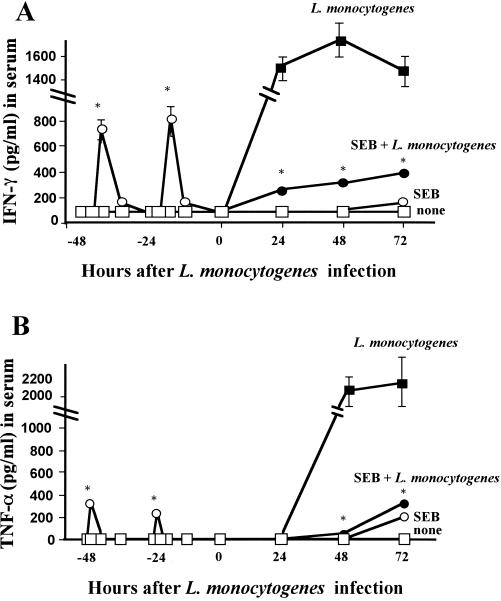

Since various kinds of cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α are secreted in SEB-treated mice (28), we compared the secretion between SEB-pretreated mice and nontreated mice. Figure 2 shows that secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α in SEB-primed mice increased temporarily. Furthermore, after infection with L. monocytogenes, the secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the sera and spleens of SEB-pretreated mice was diminished promptly. This result indicates that the enhanced host defense was not due to the enhanced cytokine secretions.

FIG. 2.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α in sera of mice before and after infection with L. monocytogenes. Mice were divided into four groups as follows: no treatment (□), pretreatment with SEB (10 μg) twice (○), infection with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (▪), and pretreatment with SEB (10 μg) twice and infection with 104 of CFU L. monocytogenes (●). Sera from five mice in groups □ and ○ were harvested at 48, 45, 42, 36, 24, 21, 18, and 12 h prior to infection. Additionally, sera from all mice in the four groups were harvested at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after infection. The amounts of IFN-γ (A) and TNF-α (B) in sera were measured by ELISA. Values are presented as the mean picograms/milliliter ± the standard deviation. ∗, P < 0.01 compared to L. monocytogenes.

Effect of innate immunity after pretreatment with SEB.

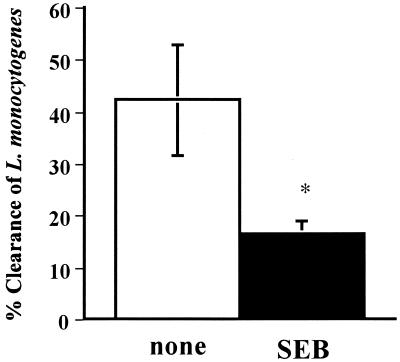

We determined which type of immune response, innate immunity or adaptive immunity, was enhanced in this situation. The influence of innate immunity by pretreatment with SEB was assessed by phagocytosis of spleen macrophages to L. monocytogenes. In Fig. 3, macrophages in SEB-pretreated mice were less phagocytic than those in nonpretreated mice, suggesting that innate immunity does not function after pretreatment with SEB.

FIG. 3.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on macrophage phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes. Mice were divided into two groups (six mice per group). One group was not treated (none [open bar]), and the other was pretreated i.p. with SEB (10 μg) twice 1 and 2 days before being killed (SEB [closed bar]). Spleen macrophages were harvested, and phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes was assessed as described in Materials and Methods. Value are presented as the mean percentage of eliminated L. monocytogenes ± the standard deviation. ∗, P = 0.0095 compared to none.

Effect of adaptive immunity after pretreatment with SEB.

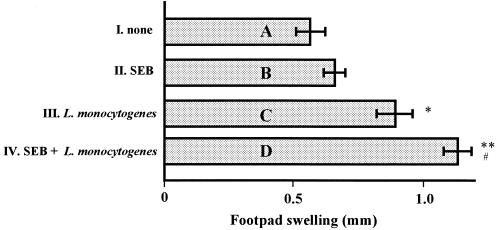

We next assessed whether pretreatment of mice with SEB could enhance the Listeria-specific T-cell response, which consisted of a Th cell response and a CTL response, in vivo. To determine the influence of Th cell activity by pretreatment with SEB, mice in groups C and D had their footpads infected with HKL and spleen T cells from only L. monocytogenes-infected mice or from SEB-pretreated and L. monocytogenes-infected mice, and the DTH response of the two groups was compared. As shown in Fig. 4, the DTH response of mice injected with HKL and spleen T cells from SEB-pretreated and L. monocytogenes-infected mice was significantly higher than that of mice injected with HKL and spleen T cells of only L. monocytogenes-infected mice. On the other hand, a DTH response of mice injected with HKL and spleen T cells from mice that were only SEB pretreated was not detected (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on L. monocytogenes-specific Th cells in DTH response in mice. Twenty mice were divided into four groups (five mice per group): A to D. Suspensions of HKL and T cells from groups I to IV, as described in Materials and Methods, were injected s.c. into the left hind footpad of animals in groups A to D, respectively. In the right hind footpad, PBS (25 μl) was injected s.c. as a control. The thicknesses of the left and right footpads were measured 24 h after injection. Values are presented as the mean difference of thickness between the footpads ± the standard deviation. ∗, P < 0.01 compared to none; ∗ (P = 0.0095) and ∗∗ (P = 0.0065) compared to bar A; #, P = 0.039 compared to bar C.

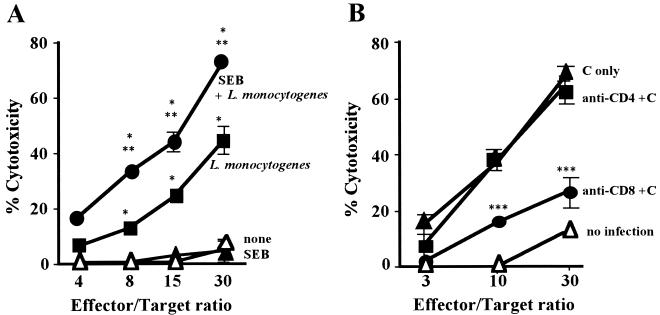

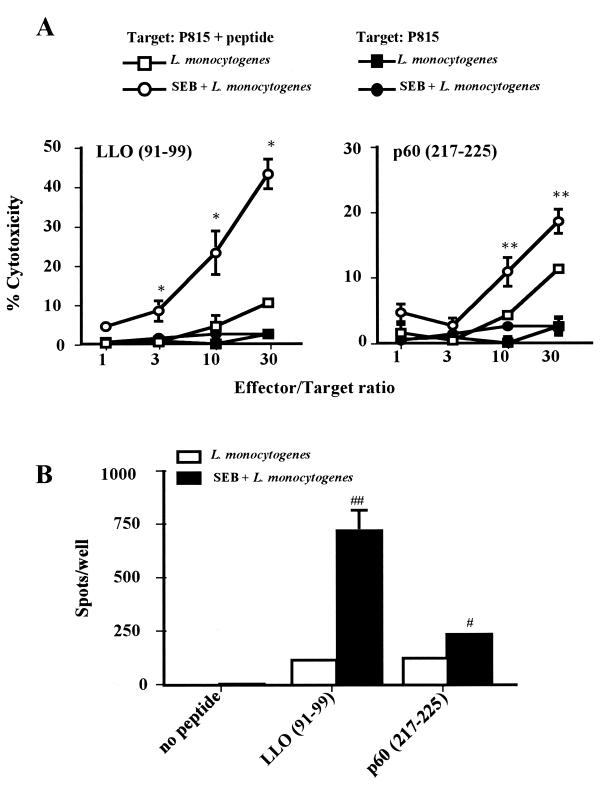

Cytotoxicity of the effector T cells was then examined against L. monocytogenes-infected J774A.1 cells, as described in Materials and Methods. Pretreatment of mice with SEB resulted in significantly enhanced cytotoxicity (Fig. 5A), which was abolished by depletion of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5B), indicating that cytotoxicity of CD8+ CTL is enhanced by pretreatment with SEB. Listeria-specific CD8+ CTLs recognize the peptides of LLO on MHC class I molecules of L. monocytogenes-infected cells (37, 38). Thus, we determined whether the increased cytotoxicity of CD8+ CTLs was really specific for Listeria to assess the cytotocity for Listeria peptide-labeled target cells. The results presented in Fig. 6A show that the cytotoxicity for LLO (91-99)- or p60 (217-225)-labeled P815 cells was significantly enhanced by the SEB. To determine whether the enhanced cytotoxicity was due to the increased number of Listeria-specific CD8+ CTLs, an ELISPOT assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The number of IFN-γ-producing cells, i.e., Listeria-specific CD8+ CTLs, was dramatically increased by SEB (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 5.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on L. monocytogenes-specific cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. (A) Twenty mice were divided into four groups as follows: no treatment (▵), pretreatment with SEB (10 μg) twice (▴), infection with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (▪), and pretreatment with SEB (10 μg) twice and infection with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (●). Spleen cells were harvested 5 days after infection and effector T cells were established as described in Materials and Methods. The cytotoxicity of the effector T cells for the L. monocytogenes-infected J774A.1 cells was assayed. (B) Groups of five mice pretreated with SEB (10 μg) twice were infected i.v. with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Effector T cells were established as described above and treated with complement (C) (▴), anti-CD4 MAb plus C (▪), or anti-CD8 MAb plus C (●). Effector T cells from untreated mice were established as described above and treated with C (▵). These T cells were used for a cytotoxic assay for L. monocytogenes infected J774A.1 cells. ∗, P < 0.01 compared to none in panel A; ∗∗, P < 0.01 compared to L. monocytogenes in panel A; ∗∗∗, P < 0.01 compared to C only in panel B.

FIG. 6.

Effect of SEB pretreatment on Listeria epitope-specific cytotoxicity. (A) Twenty mice were divided into four groups (five mice per group). Two groups of mice were infected i.v. with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (□ and ▪), and the other two were pretreated i.p.with SEB (10 μg) twice and then infected i.v. with L. monocytogenes (○ and ●). Spleen cells were harvested 5 days after infection and effector T cells were established as described in Materials and Methods. The cytotoxicity of these T cells for Listeria epitope-labeled P815 cells (104 cells/well; □ and ▪) or unlabeled P815 cells (104 cells/well; ○ and ●) was assayed. (B) Groups of five mice were infected with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (open bar) or pretreated with SEB (10 μg) twice and then infected with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes (closed bar). Effector T cells were established as described above. Listeria epitope-labeled P815 cells and effector cells (105 cells/well) were poured into Multiscreen 96-well HA plates precoated with anti-IFN-γ MAb, and an ELISPOT assay was performed. ∗, P < 0.01 compared to P815 plus peptide-L. monocytogenes in LLO (91-99); ∗∗, P < 0.05 compared to P815 plus peptide-L. monocytogenes in the p60 (217-225) panel; #, P = 0.018 compared to L. monocytogenes in the p60 (217-225) panel; ##, P = 0.002 compared to L. monocytogenes in the LLO (91-99) section.

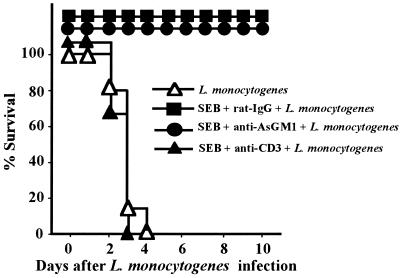

Protection of SEB-pretreated mice from L. monocytogenes infection by depletion of T cells.

Since L. monocytogenes-specific T-cell responses, but not the innate immune response, were enhanced by SEB pretreatment of mice, we examined whether T cells were necessary to protect SEB-treated mice from lethal L. monocytogenes. T or NK cells from SEB-treated mice were depleted by systemic administration of MAb specific for CD3 or antibody specific for AsGM1. T- or NK-cell-depleted mice were infected, and mortality was assessed. We found that anti-AsGM1 antibody-treated or control anti-rat IgG-treated mice were all survived, whereas all of the anti-CD3 MAb-treated mice were killed within 3 days after the infection (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Protection of SEB-pretreated mice from L. monocytogenes infection by depletion of T cells. Groups of 15 mice were pretreated i.p. with SEB (10 μg) twice and infected i.v. with 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Purified anti-AsGM1 antibody (50 μl), anti-CD3 MAb (600 μg), or rat IgG (600 μg) was administered i.v. to mice 18 h before the infection. Mortality was assessed for 10 days after the infection (P < 0.0001 for SEB plus rat IgG plus L. monocytogenes versus SEB plus anti-CD3 plus L. monocytogenes; P = 0.4331 for L. monocytogenes versus SEB plus anti-CD3 plus L. monocytogenes).

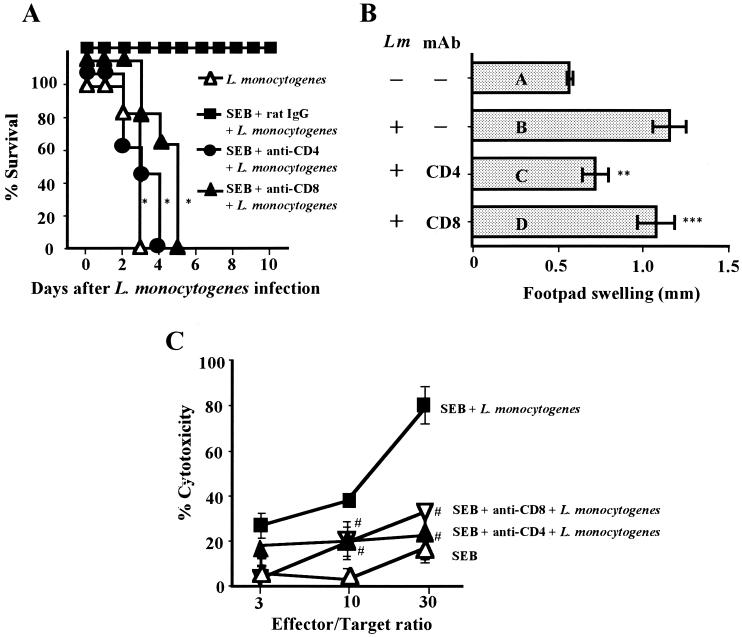

Role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the protection from lethal L. monocytogenes infection due to CTL.

The results presented above raised the question as to which type of T cells elicited the enhanced protection of mice from lethal L. monocytogenes infection after the SEB treatment. To answer this, the mortality of SEB-pretreated and T-cell-subset-depleted mice was assessed. Depletion of CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells in SEB-pretreated mice diminished protection from the lethal L. monocytogenes infection (Fig. 8A). However, depletion of CD8+ T cells in SEB-pretreated mice did not affect the L. monocytogenes-specific DTH (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, we found that the depletion of CD4+ T cells, as well as of CD8+ T cells, abolished CTL activity against L. monocytogenes-infected J774A.1 cells (Fig. 8C). These results indicated that CD8+ CTLs of SEB-pretreated mice are critically important effector cells for the protection, whereas CD4+ T cells sustained this CTL activity.

FIG. 8.

Role of CD4+ T cells in protection from lethal L. monocytogenes infection due to CTLs. (A) Groups of 15 mice pretreated i.p. with SEB (10 μg) twice were infected with 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Anti-CD4 MAb (600 μg) or anti-CD8 MAb (600 μg) was injected i.v. into mice 18 h before the infection. Mortality was assessed for 10 days after the infection. (B) Groups of seven mice pretreated with SEB and MAb as described above were infected i.v. with 103 CFU of L. monocytogenes (Lm), and spleen T cells were harvested 7 days after the infection. T cells (5 × 106 cells) and HKL (5 × 107 CFU) were injected into the footpads of uninfected littermates. Swelling of the footpads was measured 24 h after the injection. (C) Groups of five mice pretreated as described above were infected i.v. with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Spleen cells were harvested 5 days after the infection, and effector T cells were established. The cytotoxicity of these effector T cells for L. monocytogenes-infected J774A.1 cells was assayed. ∗, P < 0.0001 compared to SEB plus rat IgG plus L. monocytogenes in panel A; P = 0.0095 (∗∗) and 0.3402 (∗∗∗) compared to bar B in panel B; #, P < 0.01 compared to SEB plus L. monocytogenes in panel C.

Protection against L. monocytogenes challenge in HKL-immunized mice and effect of SEB.

Pretreatment of mice with SEB before immunization with Listeria proteins might enhance the protection against L. monocytogenes challenge. Mice were injected twice with PBS or SEB, 1 and 2 days before infection, and then immunized s.c. with HKL (5 × 107 CFU), CFA (100 μl), or HKL plus CFA twice. These mice were then infected with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes organisms/mouse 35 days after the secondary immunization, and the number of L. monocytogenes in the spleen was determined. The numbers of L. monocytogenes in the spleen of mice given SEB and HKL were 10 times less than in mice given SEB, CFA, or HKL (Fig. 9). We also found that the number of L. monocytogenes in mice given SEB and HKL was significantly lower than in the spleen of mice given CFA and HKL (Fig. 9), indicating that SEB exhibited more effective adjuvant activities than CFA for immunization with HKL.

FIG. 9.

Protection against L. monocytogenes challenge in HKL-immunized mice and effect of SEB. Groups of 10 mice were injected with SEB (10 μg) or CFA (100 μl) and immunized s.c. with HKL (5 × 107 CFU) twice as indicated. These mice were infected with 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes/mouse 63 days after the initial immunization. Spleen was harvested 4 days after the infection, and the number of L. monocytogenes colonies in the spleen was determined. P = 0.0095, 0.0065, 0.0020, 0.0057, and 0.0012 for group A compared to groups B to F, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated here that pretreatment of mice with the superantigens SEB and SPEA protected mice from lethal infection with L. monocytogenes but not from lethal infection with S. pyogenes. These results are consistent with the finding by Nichterlein et al. (37). Further, we found that not only SEB but also rSPEA enhanced protection from L. monocytogenes infection and that CD8+ T cells are the main effector for this host defense. We also provided new evidence that the enhanced protection of mice by pretreatment with SEB is due to an augmentative T-cell-mediated immune response rather than to an innate immune response. Moreover, we introduced new insight into the potential use of superantigens as adjuvant-like additives for new vaccine candidates.

Many exotoxins synthesized by S. aureus and S. pyogenes are now classified as superantigens. They were originally identified to cause food poisoning, fever, skin syndrome, or severe toxic shock syndrome (3, 18, 24). Superantigens also stimulate large numbers of T cells and antigen-presenting cells (3), which lead to greatly increased synthesis of inflammatory cytokines, e.g., IFN-γ, and enhanced innate immunity (10, 44, 49) and adaptive immunity (17, 56) after infection with intracellular parasites such as L. monocytogenes. Our study here clearly demonstrated that the administration of superantigen, either SEB or rSPEA, protected mice from lethal infection by L. monocytogenes (Fig. 1). Furthermore, superantigen-primed protection of mice against lethal L. monocytogenes infection depends on the timing of the SEB administration, because pretreatment with SEB protected all mice from infection, whereas posttreatment with SEB did not (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

The host defense mechanism against primary L. monocytogenes infection in normal mice is due to the phagocytosis of TNF-α-producing macrophages, which are activated by IFN-γ produced by NK cells (10, 44, 49). Resistance to secondary L. monocytogenes infection requires T cells (14). However, since SCID mice and TCR β-chain-, MHC class I-, or class II-deficient mice survived primary infection of L. monocytogenes (2, 21, 25), T cells are not the main effector cells to protect the host from primary infection. In our study, pretreatment with SEB enhanced Listeria-specific T-cell responses but not innate immune responses (Fig. 3, 4, 5, and 6). Furthermore, the protection of SEB-pretreated mice from primary L. monocytogenes infection was abolished by depletion of T cells but not by depletion of NK cells (Fig. 7). These results indicate that SEB-primed protection mechanism is mainly due to T-cell-dependent adaptive immunity, which is different from that in normal mice.

Attempts were made to determine what types of protection mechanisms functioned in mice given SEB. SEB administration to mice enhanced Listeria-specific CD8+ CTL activity, which in turn inhibited intracellular proliferation of this organism and protected the mice from the infection (Fig. 5, 6, and 8). This protection, however, was diminished after depletion of CTLs by injection of anti-CD4 antibodies (Fig. 7 and 8). The enhanced bacterium-specific CTL activity was induced by the treatment with SEB in in vitro model systems (30, 35). However, in vivo augmentation of the CTL activity has not been demonstrated in relation to the protection from intracellular pathogens.

Yang et al. (56) indicated that endogenous IFN-γ, which is produced at the initial stage of the infection, actually plays a critical role in the generation of protective T cells against L. monocytogenes. These protective T cells produce IFN-γ, and the amount of IFN-γ is correlated with the magnitude of the protection from L. monocytogenes infection (22, 29, 50, 51). These results raised the question as to whether pretreatment with SEB enhanced IFN-γ production and contributed to the enhanced protection. Our studies showed that secretion of IFN-γ in SEB-primed mice increased temporarily (Fig. 2). Although pretreatment with SEB increased the number of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ CTL after L. monocytogenes infection (Fig. 6), the secretion of IFN-γ in the sera of SEB-pretreated mice was diminished very promptly (Fig. 2). These results suggested that IFN-γ production just after SEB pretreatment might enhance the number of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ CTLs, which contributes to the enhanced protection from L. monocytogenes infection. However, there still remains the question as to why SEB pretreatment decreased the secretion of IFN-γ after the infection.

We have clearly shown that Listeria-specific CD4+ T-cell activity was enhanced (Fig. 4). The most important role of CD4+ T cells in SEB-primed mice appeared to support the induction of CD8+ CTLs, similar to the previous demonstration that the generation of CTLs requires help from CD4+ T cells (1, 5, 23, 53). Several investigators made trials to interpret the phenomenon by CD4+ T-cell–CD8+ T-cell collaborations (12, 23, 33, 43, 47). In this model, CD4+ T cells first stimulate macrophages to express costimulatory ligand, B7, so that they become competent to stimulate CD8+ T cells. SEB might augment the reaction of this model, resulting in the enhanced CTL activity. However, this hypothesis has yet to be confirmed experimentally.

SEB priming increased the number of CD8+ CTLs recognizing the peptides of LLO and murein hydrolase p60 protein (Fig. 6). Not only L. monocytogenes but also other intracellular pathogens, i.e., Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, have antigens that are recognized by CTLs (8, 26, 41). Therefore, it is possible that enhanced protection in SEB-primed mice could be effective against several intracellular pathogens.

Pretreatment with SEB protected all mice from the infection, whereas posttreatment with SEB did not show the protection (Fig. 1 and data not shown). It is of interest that SEB exhibited marked adjuvant activity when mice were immunized with SEB and HKL. The adjuvant activity of SEB was significantly stronger than that of CFA under the condition used (Fig. 9). Since there are few adjuvants which induce antigen-specific CTL activity, such as immunostimulatory complexes (36, 48), SEB could be one of the rare adjuvants to enhance CTL activity.

Thus, pretreatment with sublethal doses of superantigens protects mice from lethal L. monocytogenes infection, which is most likely due to the increased number of L. monocytogenes-specific CD8+ CTLs in the presence of CD4+ T cells. Superantigens such as SEB may therefore be a useful tool in the protection of hosts from infections with intracellular pathogens, including L. monocytogenes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashman R B, Müllbacher A. A T helper cell for anti-viral cytotoxic T-cell responses. J Exp Med. 1979;150:1277–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft G J, Sheehan K C F, Schreiber R D, Unanue E R. Tumor necrosis factor is involved in the T cell-independent pathway of macrophage activation in scid mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackman M A, Woodland D L. In vivo effects of superantigens. Life Sci. 1995;57:1717–1735. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02045-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouwer H G A, Hinrichs D J. Cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses to epitopes of listeriolysin O and p60 following infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2515–2522. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2515-2522.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buller R M L, Holmes K L, Hügin A, Frederickson T N, Morse H C., III Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo in the absence of CD4 helper cells. Nature. 1987;328:77–79. doi: 10.1038/328077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavaillon J-M, Müller-Alouf H, Alouf J E. Cytokines in streptococcal infections. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:869–879. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophil-mediated dissolution of infected host cells as a defense strategy against a facultative intracellular bacterium. J Exp Med. 1991;174:741–744. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Fonseca D P A J, Joosten D, van der Zee R, Jue D L, Singh M, Vordermeier H M, Snippe H, Verheul A F M. Identification of new cytotoxic T-cell epitopes on the 38-kilodalton lipoglycoprotein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using lipopeptides. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3190–3197. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3190-3197.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davignon J L, Budd R C, Ceredig R, Piguet P F, McDonald H R, Cerottini J C, Vassalli P, Izui S. Functional analysis of T cell subsets from mice bearing the lpr gene. J Immunol. 1985;135:2423–2428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn P L, North R J. Early gamma interferon production by natural killer cells is important in defense against murine listeriosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2892–2900. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2892-2900.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagin U, Hahn U, Grötzinger J, Fleischer B, Gerlach D, Buck F, Wollmer A, Kirchner H, Rink L. Exclusion of bioactive contaminations in Streptococcus pyogenes erythrogenic toxin A preparations by recombinant expression in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4725–4733. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4725-4733.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerder S, Matzinger P. A fail-safe mechanism for maintaining self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1992;176:553–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harty J T, Bevan M J. CD8+ T cells specific for a single nonamer epitope of Listeria monocytogenes are protective in vivo. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1531–1538. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harty J T, Lenz L L, Bevan M J. Primary and secondary immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:526–530. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman A, Kappler J W, Marrack P, Pullen A M. Superantigens: mechanism of T-cell stimulation and role in immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:745–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiromatsu K, Yoshikai Y, Matsuzaki G, Ohga S, Muramori K, Matsumoto K, Bluestone K, Nomoto K. A protective role of γ/δ T cells in primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1992;175:49–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igarashi K-L, Mitsuyama M, Muramuri K, Tsukada H, Nomoto K. Interleukin-1-induced promotion of T-cell differentiation in mice immunized with killed Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3973–3979. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3973-3979.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson H M, Russell J K, Pontzer C H. Staphylococcal enterotoxin microbial superantigens. FASEB J. 1991;5:2706–2712. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.12.1916093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones D. Foodborne illness. Lancet. 1990;336:1171–1174. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92778-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Julius M H, Simpson E, Herzenberg L A. A rapid method for the isolation of functional thymus-derived murine lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1973;3:645–649. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830031011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufmann S H E, Ladel C H. Role of T cell subsets in immunity against intracellular bacteria: experimental infections of knock-out mice with Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Immunobiology. 1994;191:509–519. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann S H E, Rodewald H-R, Hug E, de Libero G. Cloned Listeria monocytogenes specific non-MHC-restricted Lyt-2+ T cells with cytolytic and protective activity. J Immunol. 1988;140:3173–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keene J, Forman J. Helper activity is required for the in vivo generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1982;155:768–782. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krakauer T. Immune response to staphylococcal superantigens. Immunol Res. 1999;20:163–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02786471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladel C H, Flesch I E A, Arnoldi J, Kaufmann S H E. Studies with MHC-deficient knock-out mice reveal impact of both MHC I- and MHC II-dependent T cell responses on Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1994;153:3116–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Wilkinson R J, Malin A S, Pathan A A, Andersen P, Dockrell H, Pasvol G, Hill A V S. Human cytolytic and interferon γ-secreting CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:270–275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leo O, Foo M, Sachs D H, Samelson L E, Bluestone J A. Identification of a monoclonal antibody specific for a murine T3 polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1374–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Litton M J, Sander B, Murphy E, O'Garra A, Abrams J S. Early expression of cytokines in lymph nodes after treatment in vivo with Staphylococcus enterotoxin B. J Immunol Methods. 1994;175:47–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee D M, Wing E J. Cloned L3T4+ T lymphocytes protect mice against Listeria monocytogenes by secreting IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1988;141:3203–3207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason K M, Dryden T D, Bigley N J, Fink P S. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B primes cytokine secretion and lytic activity in response to naive bacterial antigens. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5082–5088. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5082-5088.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miethke T, Wahl C, Heeg K, Echtenacher B, Krammer P H, Wagner H. T cell-mediated lethal shock triggered in mice by the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B: critical role of tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1992;175:91–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miethke T, Wahl C, Heeg K, Wagner H. Acquired resistance to superantigen-induced T cell shock. J Immunol. 1993;150:3776–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchison N A, O'Malley C. Three-cell-type clusters of T cells with antigen-presenting cells best explain the epitope linkage and noncognate requirements of the in vivo cytolytic response. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1579–1583. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mocci S, Dalrymple S A, Nishinakamura R, Murray R. The cytokine stew and innate resistance to L. monocytogenes. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moran T M, Toy E, Kuzu Y, Kuzu H, Isobe H, Schulman J L. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B-activated T cells can be redirected to inhibit multicycle virus replication. J Immunol. 1995;155:759–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morein B, Sundquist B, Höglund S, Dalsgaard K, Osterhaus A. Iscom, a novel structure for antigenic presentation of membrane proteins from enveloped viruses. Nature. 1984;308:457–460. doi: 10.1038/308457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichterlein T, Kretschmar M, Mussotter A, Fleischer B, Hof H. Influence of staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) on the course of murine listeriosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;11:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pamer E G. Direct sequence identification and kinetic analysis of an MHC class I-restricted Listeria monocytogenes CTL epitope. J Immunol. 1994;152:686–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pamer E G, Harty J T, Bevan M J. Precise prediction of a dominant class I MHC-restricted epitope of Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1991;353:852–855. doi: 10.1038/353852a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plaut M, Lichtenstein L M, Gillespie E, Henny C S. Studies on the mechanism of lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis. IV. Specificity of the histamine receptor on effector T cells. J Immunol. 1973;111:389–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pope M, Kotlarski I, Doherty K. Induction of Lyt-2+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes following primary and secondary Salmonella infection. Immunology. 1994;81:177–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ralph P, Prichard J, Cohn M. Reticulum cell sarcoma: an effector cell in antibody-dependent cell-mediated immunity. J Immunol. 1975;114:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rock K L, Clark K. Analysis of the role of MHC class II presentation in the stimulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by antigens targeted into the exogenous antigen-MHC class I presentation pathway. J Immunol. 1996;156:3721–3726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothe J, Lesslauer W, Lötscher H, Lang Y, Koebel P, Köntgen F, Althage A, Zinkernagel R, Steinmetz M, Bluethmann H. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1993;364:798–802. doi: 10.1038/364798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarmiento M, Glasebrook A L, Fitch F W. IgG or IgM monoclonal antibodies reactive with different determinants on the molecular complex bearing Lyt 2 antigen block T cell-mediated cytolysis in the absence of complement. J Immunol. 1980;125:2665–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaible U E, Collins H L, Kaufmann S H E. Confrontation between intracellular bacteria and the immune system. Adv Immun. 1999;71:267–377. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sigal L J, Reiser H, Rock K L. The role of B7-1 and B7-2 costimulation for the generation of CTL responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161:2740–2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi H, Takeshita T, Morein B, Putney S, Germain R N, Berzofsky J A. Induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells by immunization with purified HIV-1 envelope protein in ISCOMs. Nature. 1990;344:873–875. doi: 10.1038/344873a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tripp C S, Wolf S F, Unanue E. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor α are costimulators of interferon γ production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3725–3729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsukada H, Kawamura I, Arakawa M, Nomoto K, Mitsuyama M. Dissociated development of T cells mediating delayed-type hypersensitivity and protective T cells against Listeria monocytogenes and their functional difference in lymphokine production. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3589–3595. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3589-3595.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uchijima M, Yoshida A, Nagata T, Koide Y. Optimization of codon usage of plasmid DNA vaccine is required for the effective MHC class I-restricted T cell responses against an intracellular bacterium. J Immunol. 1998;161:5594–5599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vijh S, Pamer E G. Immunodominant and subdominant CTL responses to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:3366–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Boehmer H, Haas W. Distinct Ir genes for helper and killer cells in the cytotoxic response to H-Y antigen. J Exp Med. 1979;150:1134–1142. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.5.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White J, Herman A, Pullen A M, Kubo R, Kappler J, Marrack P. The Vβ-specific superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B: stimulation of mature T cells and clonal deletion in neonatal mice. Cell. 1989;56:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilde D B, Marrack P, Kappler J, Dialynas D P, Fitch F W. Evidence implicating L3T4 in class II MHC antigen reactivity: monoclonal antibody GK1.5 (anti-L3T4a) blocks class II MHC antigen-specific proliferation, release of lymphokines, and binding by cloned murine helper T lymphocyte lines. J Immunol. 1983;131:2178–2183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Kawamura I, Mitsuyama M. Requirement of the initial production of gamma interferon in the generation of protective immunity of mice against Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:72–77. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.72-77.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]