Abstract

Background

Community pharmacists were the face of the health response to the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. Their pivotal role during the pandemic has been widely recognized, as they adapted to continue to provide a higher level of care to their patients.

Objective

The objective of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of frontline pharmacists’ lived experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their roles.

Methods

Photovoice, a visual research method that uses participant-generated photographs to articulate their experiences, was used with semi-structured interviews to explore pharmacists’ lived experiences. Frontline community pharmacists who provided direct patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta, Canada were recruited. Participants were asked to provide 3–5 photos that reflected on how they see themselves as a pharmacist and/or represents what they do as a pharmacist. Data analysis incorporated content, thematic and visual analysis and was facilitated using NVivo software. A published conceptual framework model was used as the foundation of the analysis with care taken to include new concepts. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Alberta health research ethics board.

Results

Interviews were conducted with 21 participants and they 71 photos. This study advanced the conceptual framework model presented in a scoping review, of what was made visible (pharmacists' information, public health, and medication management roles) and what was invisible but made visible by the pandemic (pharmacists’ leadership roles). It was revealed through the reflective nature of this study the important leadership role pharmacists have in their communities.

Conclusions

This study highlighted the work of community pharmacists responding to the COVID-19 pandemic through their information, public health, medication management, and leadership roles. Their experiences also made visible the cost their work had on them as they did more to adapt and continually respond as the pandemic evolved. Pharmacists recognized their role as leaders in their practice and communities.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Photovoice, Community pharmacists, Roles, Lived experience, COVID-19 pandemic

1. Introduction

Disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic present a challenge for the healthcare system as there is an accumulation of disaster-specific health needs, existing chronic conditions, temporary suspended health services, and overstretched healthcare resources.1 However, disasters also create a unique permeable environment where the traditional healthcare hierarchy is forgotten and the all hands-on deck mentality kicks in, rightfully allowing for the rapid expansion of roles and responsibilities1 and the emergence of informal leadership. For pharmacists, this is evident with the adaptation of their everyday roles (e.g., chronic condition management, medication supply, etc.) and the extension of autonomous roles (e.g., prescribing, vaccinations, point-of-care testing (POCT) etc.).1 Pharmacists' pivotal role during the COVID-19 pandemic has been widely recognized, with official and public recognition as essential healthcare workers and adapting pharmacy legislation to expand pharmacists’ capacity to provide healthcare services.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a paradigm shift of pharmacists' roles and responsibilities. A scoping review of frontline pharmacists' roles and services during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic reported that the global reach and prolonged nature of the pandemic has made visible the different layers of pharmacists' roles and services in public health, information, and medication management.1 The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the necessity for pharmacists to perform public health roles in a very public and visible way.5 , 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Pharmacists' expertise in critically appraising evidence was expanded to meet the overwhelming need to provide accurate and reliable information to patients, other healthcare providers, and the general public.5 , 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 , 17, 18, 19 , 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 It is suggested that the pandemic has brought to light the valuable position of pharmacy within our healthcare system that it has created a paradigm shift of pharmacists’ roles to more of a trusted information source with greater autonomy.1 , 59

Pharmacists were on the frontline of the response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, they were identified as an accessible safe haven in which patients could receive healthcare.60, 61, 62 This has also been acknowledged in previous pandemics with studies of H1N1, finding patients chose pharmacies to receive education about the pandemic and vaccinations.61 , 62 This study aimed to explore pharmacists’ lived experiences and add to the growing body of literature on pharmacists roles during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Qualitative study design

This qualitative study is informed by social constructionist perspectives that recognize the value of engaging participants in the research process to construct knowledge and meaning together with researchers as they engage with the world they are interpreting.63 , 64

The “Conceptual framework model of pharmacists' role change during COVID-19 pandemic” provided a theoretical basis for the study. It delineates pharmacists' roles during the pandemic into three broad categories: public health, information, and medication management.1 The framework theorizes the existence of two layers of change that influence pharmacists' professional roles during the pandemic - visible and invisible. The conceptual framework model depicts the different layers of pharmacists' roles and the level of visibility that these roles are pitched at: patients, teams, and community/society. Previously, the most visible roles of pharmacists were those provided to individual patients (e.g., dispensing medicines).1 Yet, COVID-19 highlighted and made visible at the community and society level all three layers of pharmacists’ roles: public health, information, and medication management. Frontline pharmacists were sought after for their roles in information and public health which represent areas of expertise and roles less often acknowledged.1

The Photovoice method was used because it encourages participant engagement through reflection and discussion based on participants’ own photographs.65 It is considered an innovative method for studying disasters and providing theoretical insights related to extreme events and experiences.66 In pharmacy and health services research, this method can foster understanding of lived experiences and promote change.67 Photovoice has been used by pharmacy researchers to understand experiences living with mental illness and cancer treatment.67 This method can give voice to practices that are poorly understood, such as pharmacy practice during a sustained disaster like the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Context

This study was conducted in the western-Canadian province of Alberta where pharmacists can practice to their full scope.68 The population of Alberta is approximately 4.2 million.69 At the time of this study, there were 6,051 practicing pharmacists including 4,948 authorized to administer drugs by injection and 3,515 with independent prescribing authorization and 1,593 licensed pharmacies.70 Pharmacists can access patient information through a provincial electronic health record,71 order laboratory tests, administer medications by injection, and prescribe them. All pharmacists may prescribe in an emergency, adapt prescriptions written by another prescriber and authorize medication refills.72 Pharmacists who have successfully obtained their independent prescribing may also initiate new medication therapy.72 , 73 Within this scope of practice, individual community pharmacists' practices vary and their roles are continually evolving.74 Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, most community pharmacists would have been authorized to administer vaccines and authorizing prescription renewals for narcotics. The Alberta government extended compensation to community pharmacies for pharmacist-provided COVID-19 services (i.e., screening, testing, and vaccinations).

2.3. Participants and recruitment

Frontline community pharmacists who had provided direct patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic and were licensed to practice in Alberta, Canada were eligible to participate in the study. Participants were recruited through the RxCELLENCE Pharmacy Network (https://www.epicore.ualberta.ca/home/rxcellence/), Alberta Pharmacists Association, and social media platforms (e.g., Twitter and FaceBook). As a thank you for their participation an honorarium of a $100 gift card was provided.

2.4. Research team and reflexivity

The research team consisted of 4 members, 2 female and 2 male pharmacist researchers all of whom have research credentials and considerable experience in the areas of pharmacy practice. Additionally, a pharmacy student (JC) assisted in the study. All members had experience conducting interviews and had previously worked together exploring pharmacists' roles during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 , 60 , 75 , 76 Three of the researchers (KEW, RT, YA) engage regularly with a network of pharmacists who participate in practice research studies. This was all team members' first experience using the photovoice method. The researchers' interest in this work stemmed from a scoping review that identified the visible and invisible changes to the pharmacy profession because of the pandemic.1 They wanted to understand pharmacists' lived experiences during the pandemic and it was thought that exploring pharmacists' professional roles would provide valuable insight into mechanisms of practice change and how to deploy and sustain it, as well as act as the base for curriculum evolution.1Additionally, a better understanding of changes to pharmacists’ professional work during a time of sustained crisis could provide insight into practice change and, ultimately, improvements to patient care. The research team assumed that interviews with community pharmacists combined with their own photographs would elicit rich descriptions and insights stemming from their lived experiences during the pandemic. The reporting of this qualitative research followed the COREQ criteria.77

2.5. Data collection

Participants were invited to virtual interviews using the Zoom platform. The interviews ranged from 30 to 90 min in length. Prior to the interview participants were asked to submit 3–5 photos that reflected on what they do and/or how they see themselves as pharmacists. These photos were used to guide the interview and elicit deeper understanding and meaning. The semi structured interview was divided into four segments: (1) demographics were collected to ensure a diverse participation, (2) photovoice exercise which involved exploring the photos submitted by the participant (e.g., What does this photo mean to you as a pharmacist? How does it describe what you do?), (3) a photo elicitation exercise where other photos were provided and participants were asked to rank them, and (4) open-ended questions about their experiences of COVID-19 (e.g., do you think what you do or how you see yourself as a pharmacist and the pharmacy profession will change once the COVID-19 pandemic is over?). Due to the wealth of data and different methods employed, this paper will only report on the second segment (i.e., the photovoice exercise portion of the interviews). The interview guide is provided in Appendix A.

2.6. Data analysis

The interview text and the participants' photos were included in the analysis. Two researchers (KEW & TS) independently analyzed the interview transcripts to generate initial codes. Following this, the two coders met to review initial codes following initial analysis of each interview. The photo data were interpreted alongside the interview data, to ensure each photo was analyzed according to how the participants intended, to give voice to how they were feeling and what they experienced. A second iteration of coding was completed following discussion and review of all codes, based on consensus. From there themes were identified from the codes and presented to the research team. The “Conceptual framework model of pharmacists’ role change during COVID-19 pandemic” framework was considered appropriate to apply to the data analysis and thus, the codes were further analyzed and grouped using the framework (roles) and themes (experiences) to make sense of the data. Reflexive practice activities supported understanding of roles and experiences that were both anticipated and unexpected. Data analysis was performed with the assistance of the NVivo software (QSR International, USA).

2.7. Rigor

Trustworthiness was achieved in this study through the following measures: (1) thick contextual description of the setting, participants, and data interpretation, (2) investigator triangulation with two researchers independently conducting analysis and discussing interpretations, 3) reflexivity practices involving in-depth discussion of researchers' positions, reactions, and interpretations, (4) careful documentation at all research stages, and (5) tactical authenticity through use of the photovoice method to prioritize participants’ voices in the research process.67 , 78

2.8. Ethics

Ethics was obtained from the University of Alberta health research ethics board (Pro00110266). Verbal informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview to record the interviews, publish any quotes, and to use the photos submitted in a deidentified format.

3. Results

Interviews were conducted with 21 individuals between August 2021 to October 2022. Three interviews were excluded from the analysis as it was subsequently discovered that the individuals were impersonating licensed pharmacists. Data and thematic saturation were achieved after 15 interviews. Additional interviews were conducted to confirm saturation had been reached. Out of the 18 included participants, there were 11 females and 7 males; 6 participants worked in rural areas while the rest were in urban practice; and 7 worked for a chain pharmacy, 9 for independent pharmacies, and 2 were relief contractors (see Appendix B for participant characteristics). The participants supplied 71 photos (Appendix C) which were analyzed alongside the interview transcripts.

The conceptual framework model that was used as the foundation for this study categorizes pharmacists’ roles into 3 broad groups - information, public health, and medication management. Additionally, new findings of what was made visible to the participants by the pandemic and their engagement with the photovoice method are discussed. Overall, the participants described the people-focused nature of their practice and how it guided their roles and responsibilities during the pandemic.

“Ultimately patients are the top of the list and number one, and they are our priority. Doesn't matter where you are, what setting that you're coming in from, that you're [the patient] at the top of the list, that you are our priority.” [Participant 14]

3.1. Community pharmacists’ roles during the COVID-19 pandemic

3.1.1. Information

The prominence of participants' information role was a common thread across all the interviews. The participants described that while the role was not unique, it was challenging and pushed them out of their comfort zones. Participants attributed the accessibility of community pharmacies made their information role more critical to the public during the pandemic and the demand for pharmacists’ advice was “magnified exponentially throughout COVID” [Participant 2].

The time required to perform this role of providing information for every individual seeking information on such a large scale, as was seen in the pandemic, was overwhelming for many participants. The telephone became a symbol of the information overload and burden pharmacists carried, not only for information needs of their usual patients but for members of the wider community (Fig. 1 ).

“That is everything that was wrong with community pharmacy when I left, I hated it! It was ringing non-stop, and we were focused on that.” [Participant 1]

Fig. 1.

Telephone [Participant 1].

Participants felt that they were identified as a trusted resource for information pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing healthcare, and public health measures. Information was readily available online through various means, but the public and patients sought them as a reliable and trustworthy source.

“The one thing that was very clear to me and my other colleagues that I talked to is we seem to be the main health profession that the community called to ask questions about whatever they had with respect to their health.” [Participant 7]

“I think that there is so much information out there on TV. There's so much information on the news, on Google, even some publications. While that [information is] coming out, [it is] creating this polarising issue even around COVID vaccines in general. It was just overall overwhelming [for] our patients in terms of how much is going on and how much information is out there and what information can be trusted. And then [the patients] always came back to us to ask what they should actually trust and what is it that is actually true” [Participant 2]

Part of this information role included being aware of misinformation and appropriately addressing it with people, especially those seeking information about COVID-19. With pharmacists being so readily accessible and having a strong reputation in the community, the public and patients valued their advice and the time they took to listen and respond in a non-confrontational manner.

“I had a probably 50-ish year-old couple call me when it was quiet, I was able to spend enough time on the phone with them. But they had so many questions about COVID vaccines, they hadn't gotten it yet and they threw just about every question [that] you can imagine at me. Everything from Ivermectin to ‘can it change your DNA?’ I really appreciated that conversation because they were never confrontational about it, just they heard these things, and they wanted help with it. And like I said, [I] probably spent 20–30 minutes on the phone just answering questions and they were really happy with it. I found out later, the guy came up to me one day [to say] ‘hey, thank you for spending so much time with us, we are two weeks past my second dose’.” [Participant 11]

The participants expressed frustrations with this role as they felt it was taking over their other duties and they were expected to manage the increase of this role on top of their regular workload. Some participants suggested the information role could be shared with others as it did not always require a pharmacist's expertise. However, their pharmacies were not prepared for the overwhelming nature of this role and did not have additional staff to dedicate to the telephone.

“It's just really tough to do anything else, except answer the phone calls, because sometimes, it would be getting phone calls on a every like 30 seconds to a minute interval, which is a lot!” [Participant 4]

The information requirements changed throughout the pandemic, as different needs became apparent with respect to issues such as medication shortages, supply chain, access to personal protective equipment (PPE), COVID-19 screening and testing, COVID-19 vaccinations and eligibility. Fulfilling the role as a reliable and trusted information professional came with the expectation that pharmacists were always up-to-date on the latest information even in a rapidly changing landscape like a pandemic. Participants expressed feeling a strong responsibility to live up to the expectations of being a reliable and trustworthy source of information but also felt challenged in this role due to the perceived lack of timely communication to them regarding the policy changes throughout the pandemic. They spent considerable time outside of work hours to ensure they were up-to-date on the latest information as their credibility was seen as exceptionally important to them and their practices. This was represented in the photo of a pharmacist having news and social media updates for breakfast (Fig. 2 ).

“This photo was taken at my kitchen table at breakfast in the morning getting ready for work. It's a picture of me with my phone open to my Facebook App and my laptop open to the Internet. Because during COVID very early on, my mornings were consumed by opening Facebook, to see what the most recent gossip or update regarding either information on COVID itself, or the vaccines, or what the Government of Alberta was recommending for public health measures. And then my laptop was open to my resources, fact checking whatever gossip was being circulated that day. Because I knew that my day would be filled with patients coming to the pharmacy asking about what they read about COVID or what the government had recommended for changes. So, it represents what I do as a pharmacist, because it shows how dedicated I am to staying up-to-date and having the most accurate information for my patients. Not just knowing what the latest news article was about COVID, but also knowing whether what I was reading is accurate, and if it wasn't accurate how to explain why it wasn't and what is accurate. So, it's making sure that I have the best available information for my patients … But it was kind of like, a behind the scenes on why when people (whether most of my colleagues or my patients) asked me a question, why I was prepared. I took my [information] role and I took the trust that my colleagues and my patients had in me, very seriously. But it's not a typical picture of me. I don't think that's what people would usually think of when they see me in my practice.” [Participant 16]

Fig. 2.

Pharmacist searching for information, reading news and policy updates at breakfast prior to starting a shift [Participant 16].

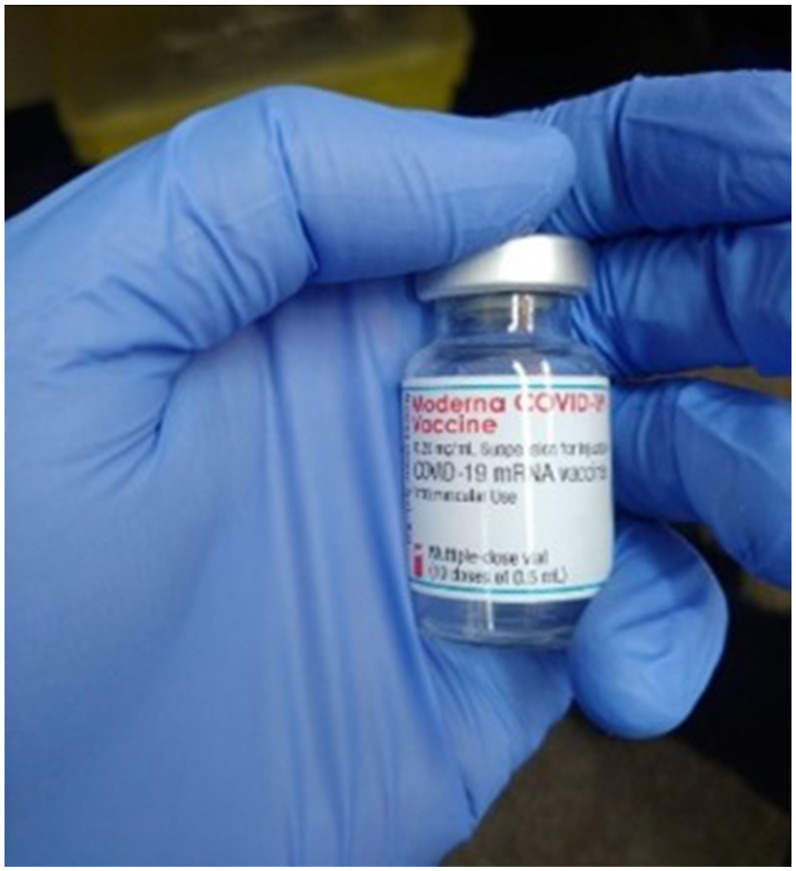

3.1.2. Public health

Pharmacists’ role in public health was another common thread throughout the interviews. Their role in this area was not new but became more visible to the participants themselves as community pharmacists were the face of the health response to the pandemic. The most visible service was administering COVID-19 vaccines (Fig. 3 ).

“At one point in time, my other pharmacist and myself were giving an injection every three minutes. So, she's doing one, I'm doing paperwork. I'm doing one, she's doing the paperwork.” [Participant 5]

“Since January of 2021, I’ve given over 4,000 injections. So, it seems daunting.” [Participant 6]

Fig. 3.

Pharmacist hand holding a COVID-19 vaccine vial [Participant 6].

The participants discussed the challenge with these public health roles as they were on the frontline and unprepared for their responsibility in enforcing the public health policies and guidelines set out by the government.

“We got a positive [COVID infection] case this morning and I really wish we could tell someone. The guy didn't even want to wear a mask when I enforced my policy and I say, ‘if you don't wear one, you're not coming in’. So, then he did wear one, but Oh My God like [he was] positive! Every day you're stressed by these kinds of interactions.” [Participant 9]

Participants shared their experiences being on the frontline of the pandemic performing these public health roles over several months. They bore the brunt of people's emotions and projected fears or anxiety. This participant was tearful as experiences with emotional patients were recounted.

“It's been crazy, like I can't even tell you the number of people that I’ve sat with in the injection room while they've cried. And I hate emotion, I am not a hugger. [It was difficult] for me to have to deal with all of that. I had one lady; she was an hour and a half on the floor curled up in a fetal position sobbing because she was afraid the vaccine was going to kill her …. her fear was real … What do you do? Sorry! It's really hard to deal with that level of emotion all the time and it's been, I would say the last few months, even worse because the people we're seeing are the people that don't want [the vaccine]. I have had a clipboard thrown at me. I’ve been sworn at.” [Participant 5]

Despite the significant workload and deep emotional experiences that were recounted, there was also a strong sense of accomplishment and pride among the participants. The extraordinary impact their public health role had on society and how tangibly they made a difference in the pandemic fight through vaccinations were very visible to them.

We just did a tremendous amount of work, and I can honestly say that I'm quite proud of the majority of pharmacists who put in all that effort to help people get vaccinated and get their COVID tests. And yeah, I'm happy with the effort that I put into helping society.” [Participant 12]

3.1.3. Medication management

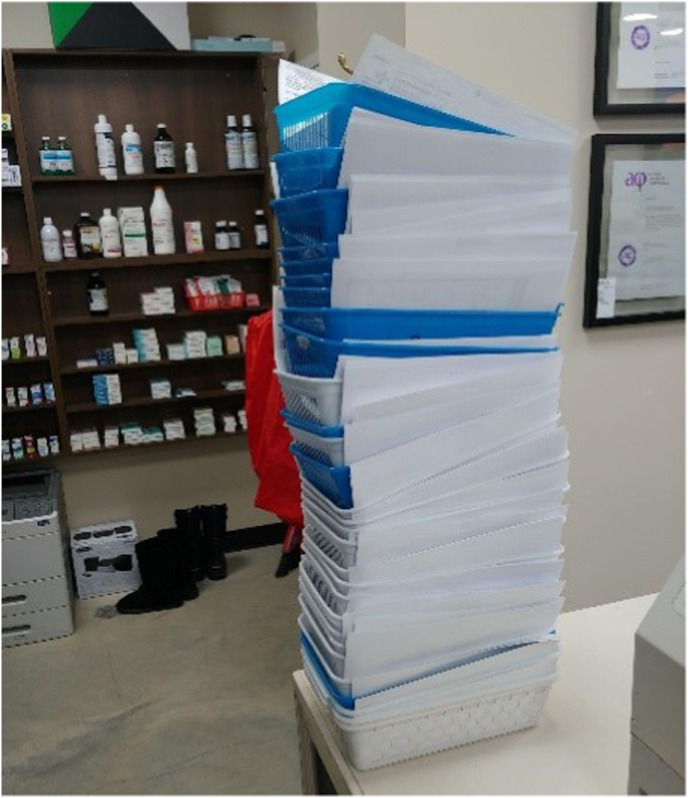

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the importance of pharmacists' medication management roles for patients such as managing chronic conditions, renewing prescriptions, dispensing medications, etc. The participants' commitment to spend time with patients and to focus on the whole patient and not just the public health measures required to combat a COVID infection were made visible. This led to some participants feeling discontent as they did not have time to dedicate to patient-centred medication reviews and care planning for their patients. The medication management activities piled up as other needs were prioritized due to the unrelenting needs of the COVID-19 pandemic and pharmacists’ information and public health roles (Fig. 4 ). Yet, this role remained a priority for the participants, as they ensured patients received, at minimum, their medications and prescription refills.

“COVID is just taking the spotlight and taking me away from my traditional roles of education and sitting down with patients and being able to actually spend time with people. Which is like the best part, when actually actively helping someone through something.” [Participant 6]

Fig. 4.

Piles of prescriptions to be dispensed at the end of the day [Participant 6].

The increase in workload for pharmacists was visible to the participants in the piles of medication management tasks that were left until the end of the day (Fig. 5 ). The participants felt a strong sense of pressure to do more with the same finite resources.

“Your regular roles end up being on back burner, like your regular dispensing and your blister packaging. COVID obviously brought a bunch of extra paperwork in as well. So, this is almost towards the end of the day, when it's like - Okay, I can't even go home, because look at my countertop and that's the same for every store. But [this photo is] just kind of like a visual of behind the scenes. What's going on?” [Participant 20]

Fig. 5.

Messy dispensary desks with the piles of medication management tasks to still be completed [Participant 20].

This image of chaos behind the counter was further expanded upon by participant 5.

“Oh, it has to be reflected in the way we're practicing. I mean because it's chaos, we can't find prescription bags and orders aren’t coming in and you're not following up with the doctors, because the doctors are as badly overrun as we are. Oh yeah, that's true you could reflect this back to the chaos of the pharmacy counter. I had to laugh, we had someone come in to trial it for the day to see if they wanted to work with us as a [pharmacy] assistant and by 9:30am she said ‘you guys are all talking at the same time I don't know who I’m supposed to listen to’, she said ‘you would never know that this is the chaos behind here from the front of the counter’. I thought it was very interesting because we're just all doing whatever is going on, but there were hospital discharges and lodge changes and blister pack changes. And she was just appalled at the chaos, and then you add in five phone lines right - it's just insane.” [Participant 5]

The perception of having no time to complete these roles with the prioritization of public health and information roles and services made some participants reflect on the time pressure to perform all their responsibilities and meet all obligations in their roles within the same time constraints of their working hours (Fig. 6 ). This became unachievable for many participants resulting in them working longer hours or taking work home with them.

“I know that it's [the clock] looked at when there's been a particularly hard day, people are thinking ‘When is this day going to be over?’. I also know that it's looked at by myself sometimes in shock. So, this was 4:10pm. And on this particular day I had to be out of the pharmacy by 3 o'clock and now I'm an hour and 10 minutes late for my next obligation and it's a reality, we all have the same amount of time in life … pre-COVID I would have already been on to my next appointment at 3 o'clock versus being there for an hour and 10 minutes over my allotted amount [of time]. I think it's just highlighting the super pressure … the pressure that has occurred over COVID on the profession of pharmacy has been significant, which then takes so much more time. Well, the only thing I could tell you is, I think that there was a time when we changed to daylight savings, the last time, and it took about a week for us to change that clock, because we didn't even have time to change the clock.” [Participant 7]

Fig. 6.

Clock representing no time to complete the medication management tasks [Participant 7].

3.1.4. Leadership

In addition to the three role categories outlined in the conceptual framework model1 this study found a fourth role of leadership. The participants realized as they reflected on their lived experiences, how they were in a position of leadership in their community during the pandemic.

“We're natural leaders and as pharmacists, we take on that leadership role regardless of whether or not you are in a management role.” [Participant 2]

They also described how they felt a strong need to lead by example for their staff, colleagues, patients, and the community, especially when it came to public health measures and their role of enforcing policies (Fig. 7, Fig. 8 ).

“I think it represents what I do as a pharmacist, because it shows me walking the walk … I was doing my job as a pharmacist keeping my patients and myself safe but also for the community. If we need everyone to get vaccinated to stay safe, then I was being a role model.” [Participant 16]

“So, I feel this sort of represents the trust that I want people to be able to have in me. But also, the fact that I'm willing to put myself at your level and be like - if I expect you to do it, I expect me to do it … It feels almost hypocritical if I’m like you should do this, but I don't.” [Participant 11]

Fig. 7.

Pharmacist receiving a COVID-19 vaccination. [Participant 16]

Fig. 8.

Pharmacist wearing a mask [Participant 11].

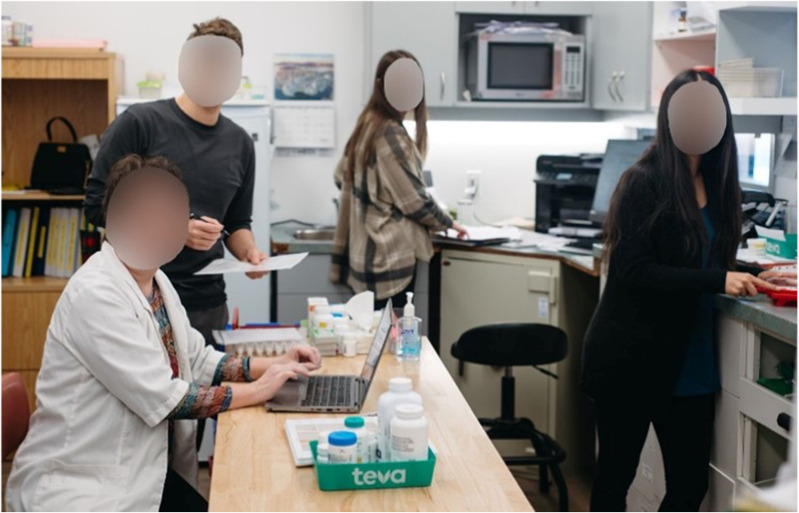

The participants expanded on this idea of leading by example to their team dynamics. Many described that although they may be the face of community pharmacy, they are supported by a team of pharmacy staff (Fig. 9 ).

“I think that we all have a role, we all work together. If that makes any sense. We're all important cogs in the wheel, no one is any better or different than the other. It's all about what we do, for our patient.” [Participant 13]

Fig. 9.

Community pharmacy team [Participant 13].

One participant expanded on this concept with their responsibility as a pharmacist to protect and consider the mental health and wellbeing of their pharmacy staff and colleagues.

“And taking that step back, we have to be on the front lines. As a matter of fact, we’ve taken on more than ever before! So, as a result of that I wanted to really outline what I see myself, as a really important job of a pharmacist, especially now during the COVID times, is actually maintaining the health and safety and the mental health and safety of our teams that we work with and our colleagues.” [Participant 2]

3.2. Community pharmacists’ lived experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic

The participants reflected on the tremendous effort required to fulfill their commitment to patient care and honour their information, public health, medication management, and leadership roles. The themes of the community pharmacists’ experiences were leadership from the frontline, accessibility is a double-edged sword, adaptability of pharmacists, threat to safety, and physical toll of being on the frontline.

3.2.1. Leadership from the frontline

One pharmacist was articulate in explaining how battered they felt and yet felt a great pride as a pharmacist with how visible their efforts have been (Fig. 10 ).

“The white coat symbolizes us as a healthcare [provider], what we're able to do for our patients. But the reason I kind of left it a little bit grimy, a little bit unfolded, shows the level of work we've had to do to attain it. And even now throughout COVID, what we've had to do to try and maintain the level of care we provide for patients. And it's very time consuming. It's a lot of the extra hours and especially with the shortages, it shows how we as healthcare professionals can be quite battered from all the external stimuli.” [Participant 14]

Fig. 10.

White pharmacist's coat crumbled and disheveled [Participant 14].

3.2.2. Accessibility is a double-edged sword

The participants felt they were on the frontlines of the pandemic and that their accessibility was a double-edged sword. The participants made the effort required to keep up with the change in expectations during the pandemic. Pharmacists were being asked to do more with the same finite resources and time. Due to enhanced visibility of pharmacy services, some participants felt there were greater demands placed on them (e.g., to keep pharmacies open to the public, to be continually accessible to people, etc.) and this led to feelings of their plate being too full (Fig. 11 ).

“The workload just increases, like the plate is full. They want you to make it look like the plate is perfect, like there's nothing on your plate, but the plate keeps getting filled … it just keeps piling up and then, like you didn't get rid of the mess, all of the workload, the prescriptions, the questions. So, a lot of things just keep piling up.” [Participant 21]

Fig. 11.

Picture of an overflowing plate [Participant 21].

3.2.3. Adaptability of pharmacists

While the increasing demands and workload became visible to the participants, some struggled to articulate in detail what they did or changed to respond to the pandemic, as to them it was an unconscious process in the face of feeling like they had no choice. The participants described how they saw no alternative other than continually adapting to meet the needs of the public.

“You just kind of do it without thinking about it. This is what you have to do. And you either, do it or you struggle along the way. You don't really have a choice.” [Participant 11]

“We can adapt our approach to make sure that we can really function in any environment, no matter how dangerous or stressful it may be, to ensure that we provide our services and the services don't fall apart. I mean, we're not closing down. Our doors are not shut. We continue to perform our service but in an adjusted manner.” [Participant 2]

3.2.4. Threat to safety

The concern for personal safety amid a public health crisis was present for the participants. They expressed unwavering commitment to their patients even at great personal risk. Society relied so heavily on pharmacists to remain an in-person service and yet the threat to their personal safety was only visible to themselves. Some participants explained how the threat to their personal safety was not considered by others in the beginning.

“I was working at a chain pharmacy, and initially at the start of the pandemic, it was mentioned that you [pharmacy staff] should not wear a mask because it will give people the impression that you are sick.” [Participant 21]

PPE and masks symbolized both personal protection and fear, as masks were perceived as intimating or scary for patients. One participant articulated their perception of the overwhelming threat to their personal safety while working as a pharmacist during the pandemic (Fig. 12 ).

“So, the reason I chose a black mask rather than the typical surgical mask. It kind of shows the level of danger and awareness that I have when I am on shift. When I am working, even though I'm doing my best to provide for my patients. That ultimately, I have to be wary of some of my own personal safety. Right. Of my family when I come home. And of course, my friends who I see and ultimately other vulnerable patients that come in and that require health services, medications and whatnot. And because I'm there and that point of contact is very important that I'm aware of my ability to potentially spread disease, especially during this COVID time. And it's just that awareness of how scary it could be. One moment you're fine. And next month, perhaps you've caught COVID. And that's one of the dangers of being a health frontline professional. And even though it may not show on individual faces of pharmacists, we are always constantly aware of the fact that there is always a possibility that we could catch a disease.” [Participant 14]

Fig. 12.

Black face mask [Participant 14].

3.2.5. Physical toll of being on the frontline

Additionally, some participants expressed the physical toll the pandemic had on their personal health, describing hair and hearing loss due to the stress of working during a pandemic.

“My hearing actually got impacted because I answered so many phone calls and my ability to manage the workflow was also impacted during that time just because you're distracted so much.” [Participant 8]

“I was also going bald, like I lost a lot of hair. My wife is like, you should probably quit …” [Participant 6]

4. Discussion

This study made visible the roles and lived experiences of community pharmacists who provided direct patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Photovoice method provided an in-depth understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and gave participants the opportunity to reflect on their lived experiences. This study advanced the conceptual framework model presented in a scoping review,1 of what was made visible (pharmacists' information, public health, and medication management roles) and what was invisible, but made visible by the pandemic (pharmacists’ leadership roles). Community pharmacists were the face of the health response to the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. They served as a reliable and trusted information source, the go-to public health professional to receive COVID tests, screening, and vaccinations, and continued to provide vital medication management roles and services, especially for those with chronic conditions. Additionally, it became clear to the participants the need to adapt to meet the increasing demand and expectations placed on them as their commitment to their patients never waned. It was revealed through the reflective nature of this study the important leadership role pharmacists have in their communities, with many of the participants setting personal expectations upon themselves to lead by example and protect their team, colleagues, and community.

There were many positives discussed by the participants of the impact of the pandemic on the pharmacy profession. For example, they felt they were visible beyond their sphere of influence of their patient, and they felt a great sense of accomplishment being able to fulfill the healthcare needs of their community through their information, public health, medication management, and leadership roles. Community pharmacists stepped up to face this unprecedented challenge with many seeing it as an unconscious decision in the face of no alternative. Another qualitative study characterized pharmacists’ roles during the pandemic as adaptative and attributed this to the resilience and flexibility of community pharmacy practice, suggesting they are always prepared for the unknown.79 They acknowledged the unintended benefit of the pandemic being, the spotlight it shone on the pharmacy profession and what pharmacists can do.79 While this was certainly the case for pharmacy across the globe,1 it was identified in this study that this adaptability and resilience came at a cost to the participating community pharmacists.

The COVID-19 pandemic infiltrated pharmacists' professional as well as personal lives, as the chaos followed them home and they were required to constantly be the emotional support for their team, colleagues, patients, community members, and families. A workforce study from New Zealand had similar findings, with the majority of their pharmacist participants stating suboptimal practice had increased and COVID-19 had impacted them personally and professionally.80 Similar to the findings of this study, an Australian study on pharmacist burnout during the pandemic found that pharmacists were reporting increased workloads and concerns for personal and family safety, which contributed to their burnout.81 Another aspect of pharmacy practice that the pandemic put under the microscope was the challenges with communication for pharmacists to effectively perform their roles. For example, it has been identified in other studies that the expectations on pharmacists’ information role surrounding public health policy changes necessitated timely and direct communication by the government, public health system, and the pharmacy profession.82

Historically, in times of disasters and emergencies, pharmacists have stepped into the leadership role to help their communities through crisis.76 , 83 This is not usually sustained post-response, as systems typically revert to their status quo. However, research predicts that with the prolonged nature and widespread reach of the COVID-19 pandemic, that the pharmacy profession has been propelled into a new era.1 , 8 , 84 It is suggested in this study that the fundamental difference between the COVID-19 pandemic and previous disasters that will be sustained, is that pharmacists have become conscious of their role as a leader in their community. The community pharmacists in this study were not always in a position of authority and yet showed true leadership in their community by leading by example and through taking care of their teams. We would suggest that community pharmacists are already leading in their communities, but this role only became visible to themselves during a crisis. We posit that community pharmacists do not identify with a position of formal authority which perhaps previous research has called leadership. We would define leadership in this study as the actions taken by the participants to lead by example, step up in the face of adversity, and to care for their teams, colleagues, and community. Leadership is an active role and not a position or job description.85 , 86

This study has provided a glimpse into pharmacists' role in leadership but further exploration of frontline leadership in community practice is warranted. Additionally, we should learn from the lived experiences of these frontline community pharmacists on how to best support them and the healthcare system for future crises. The participants in this study describe the overwhelming feeling of their plate being too full. This is not sustainable. Yet, supporting community pharmacists in their leadership role to distribute and delegates tasks within their teams is sustainable. Supporting them in this role does not mean piling more tasks onto their already full plates but including them in the decision-making of how best to distribute the workload. It should be recognized that there were reports of challenges with adequate staffing in pharmacies during the pandemic in this study. Staffing considerations need to be mitigated for future disasters and emergencies. For example, an Australia study identified that a concern for safety impacted pharmacists’ willingness to work.87 A systematic review of pharmacists preparedness found that little attention has been paid to building a resilient pharmacy workforce which could lead to critical skill and service gaps in disasters and may negatively impact patients.88 Pharmacists should be leading the change for the new pharmacy era. It is evident with the pharmacy profession progressing into this new age of practice, that we need to consider education and training for disaster management, emergency preparedness, and leadership for pharmacists and pharmacy staff.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

This study used the novel method of photovoice. Photographs facilitated collection of rich interview data to gain deep insight from the participant's experiences. This was attributed to the reflective nature of photovoice, as the participants were asked to prepare for the interview by reflecting on their experiences to supply the photos prior to the interview. This allowed the interviewer to probe into the participant's interpretation of the photos during the interviews. This study was focused on the experiences of community pharmacists working in the Canadian province of Alberta. While these results provide unique insight into the participants' lived experiences, it cannot be assumed this was the same experience for other pharmacy practice settings or regions. Additionally, this study was but a snapshot during a long and challenging disaster event and was conducted when COVID-19 vaccines were in high demand as people obtained their vaccinations and boosters. The pharmacists' roles and experiences may be different if this study was conducted at a different point in time during the pandemic. However, this seems unlikely as other studies have reported similar findings regarding pharmacists' roles and burnout.5 , 60 , 89 , 90

For the first time, the research team members faced an ethical dilemma related to imposter participants. Three participants impersonated licensed pharmacists to obtain the gift card of $100. Following this discovery, the participant photos and transcripts were not included in the data analysis. This experience highlights the complexity with incentives used to enhance participation. The $100 incentive was approved by the health research ethics board as an appropriate amount for compensation of healthcare provider's time. Experience with this dilemma has been experienced by other researchers. A recent study found a similar situation and called these dishonest people “imposter participants”, suggesting the pandemic and international economy increased the likelihood of untrustworthy people wanting to obtain the incentive gift card.91 While the amount provided was within acceptable limits in Canadian practice, the imposter participants may have circumstances such that the incentive was alluring. To mitigate this, it is suggested to include a verification step to reduce the possibilities of imposter participants.91 Researchers include procedures to safeguard participant privacy but perhaps for research that involves incentives, the practice of collecting some personal information to verify and prevent fraudulent participation is justified, for example healthcare provider license number. In this case, the research team verified participants' eligibility by searching the public register for Alberta pharmacists to determine if they were licensed community pharmacists and enhance the credibility of the study.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the work of community pharmacists responding to the COVID-19 pandemic through their information, public health, medication management, and leadership roles. Their experiences also made visible the cost their work had on them as they did more to adapt and continually respond as the pandemic evolved. Pharmacists recognized their role as leaders in their practice and communities.

Authors contributions

KEW, TS, RTT, YA were involved in the conceptualization, funding of the study, and participated in the study design. KEW, JC and YA participated in data collection and KEW and TS in data analysis. JC compiled the photobook and KEW and TS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RTT, JC and YA carried out reviews and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was made possible by the generous support of the Canadian Foundation for Pharmacy and the Alberta Pharmacists’ Association.

Declaration of competing interest

RTT receives consulting fees from Shoppers Drug Mart and Emergent BioSolutions and is a paid Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Pharmacists Journal. He has received investigator-initiated grants from Merck and Sanofi.

The remaining authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the community pharmacists who took the time to refelct and take part in this study to provide their lived experiences of working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thank you to the EPICORE Centre summer research students who assisted with aspects of this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.03.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Watson K.E., Schindel T.J., Barsoum M.E., Kung J.Y. COVID the catalyst for evolving professional role identity? A scoping review of global pharmacists' roles and services as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacy. 2021;9(2):99. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9020099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadogan C.A., Hughes C.M. On the frontline against COVID-19: community pharmacists' contribution during a public health crisis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2032–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukhari N., Rasheed H., Nayyer B., Babar Z.-U.-D. Pharmacists at the frontline beating the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00210-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertz E. Global News; 2020. Pharmacists Get Billing Code to Screen Albertans for COVID-19; Asked to Limit Drug Supplies [Internet]https://globalnews.ca/news/6703187/pharmacists-screen-coronavirus-alberta-health-drug-supply/ [cited 2020 May 4]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visacri M.B., Figueiredo I.V., Lima TdM. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1799–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.College of Pharmacists of British Columbia . Canada 2009. Professional Practice Policy-25: Pharmacy Disaster Preparedness Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aburas W., Alshammari T.M. Pharmacists' roles in emergency and disasters: COVID-19 as an example. Saudi Pharmaceut J. 2020;28(12):1797–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bragazzi N.L., Mansour M., Bonsignore A., Ciliberti R. The role of hospital and community pharmacists in the management of COVID-19: towards an expanded definition of the roles, responsibilities, and duties of the pharmacist. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland) 2020;8(3) doi: 10.3390/pharmacy8030140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elbeddini A., Botross A., Gerochi R., Gazarin M., Elshahawi A. Pharmacy response to COVID-19: lessons learnt from Canada. J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00280-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbeddini A., Prabaharan T., Almasalkhi S., Tran C. Pharmacists and COVID-19. J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13:36. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00241-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goff D.A., Ashiru-Oredope D., Cairns K.A., et al. Global contributions of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:1480–1492. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim O.M., Ibrahim R.M., Abdel-Qader D.H., Al Meslamani A.Z., Al Mazrouei N. Telemed J E Health; 2020. Evaluation of Telepharmacy Services in Light of COVID-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasahun G.G., Kahsay G.M., Asayehegn A.T., Demoz G.T., Desta D.M., Gebretekle G.B. Pharmacy preparedness and response for the prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Aksum, Ethiopia; a qualitative exploration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):913. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05763-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao Y., Ma C., Lau A.H., Zhong M. Role of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic in China - Shanghai experiences. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(5):997–1002. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S., Luo P., Tang M., et al. Providing pharmacy services during the coronavirus pandemic. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(2):299–304. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merks P., Jakubowska M., Drelich E., et al. The legal extension of the role of pharmacists in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1807–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammad I., Berlie H.D., Lipari M., et al. Ambulatory care practice in the COVID-19 era: redesigning clinical services and experiential learning. J. American College Clin Pharm. 2020;3:1129–1137. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parreiras Martins M.A., Fonseca de Medeiros A., Dias Carneiro de Almeida C., Moreira Reis A.M. Preparedness of pharmacists to respond to the emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a comprehensive overview. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2020;36(10):455–462. doi: 10.1007/s40267-020-00761-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paudyal V., Cadogan C., Fialová D., et al. Provision of clinical pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of pharmacists from 16 European countries. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;17(8):1507–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truong L., Whitfield K., Nickerson-Troy J., Francoforte K. Drive-thru anticoagulation clinic: can we supersize your care today? J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;61(2):e65–e67. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.10.016. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ung C.O.L. Community pharmacist in public health emergencies: quick to action against the coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(4):583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying W., Qian Y., Kun Z. Drugs supply and pharmaceutical care management practices at a designated hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1978–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen B., Chen L., Zhang L., et al. Wuchang fangcang Shelter hospital: practices, experiences, and lessons learned in controlling COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(8):1029–1034. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00382-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukattash T.L., Jarab A.S., Mukattash I., et al. Pharmacists' perception of their role during COVID-19: a qualitative content analysis of posts on Facebook pharmacy groups in Jordan. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(3):1900. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M., Razaki H., Mui V., Rao P., Brocavich S. The pivotal role of pharmacists during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;60(6):e73–e75. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.05.017. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hua X., Gu M., Zeng F., et al. Pharmacy administration and pharmaceutical care practice in a module hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;60(3):431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.04.006. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Como M., Carter C.W., Larose-Pierre M., et al. Pharmacist-led chronic care management for medically underserved rural populations in Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E74. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alves da Costa F., Lee V., Leite S.N., Murillo M.D., Menge T., Antoniou S. Pharmacists reinventing their roles to effectively respond to COVID-19: a global report from the international pharmacists for anticoagulation care taskforce (iPACT) J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00216-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad A., Alkharfy K.M., Alrabiah Z., Alhossan A. Saudi Arabia, pharmacists and COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13:41. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdallah I., Eltahir A., Fernyhough L., et al. The experience of Hamad General Hospital collaborative anticoagulation clinic in Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;52(1):208–214. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02276-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhat S., Farraye F.A., Moss A.C. Impact of clinical pharmacists in inflammatory bowel disease centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(9):1532–1533. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheong M.W.L. 'To be or not to be in the ward': the impact of covid-19 on the role of hospital-based clinical pharmacists - a qualitative study. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(8):1458–1463. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeRemer C.E., Reiter J., Olson J. Transitioning ambulatory care pharmacy services to telemedicine while maintaining multidisciplinary collaborations. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(5):371–375. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzik K.A., Bethishou L. The impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy transitions of care services. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1908–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim O.M., Ibrahim R.M., Z Al Meslamani A., Al Mazrouei N. Role of telepharmacy in pharmacist counselling to coronavirus disease 2019 patients and medication dispensing errors. J Telemed Telecare. 2023;29(1):18–27. doi: 10.1177/1357633X20964347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koster E.S., Philbert D., Bouvy M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the provision of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2002–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kristina S.A., Herliana N., Hanifah S. The perception of role and responsibilities during covid-19 pandemic: a survey from Indonesian pharmacists. Int J Pharmacol Res. 2020;12(Supplementry 2):3034–3039. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim R.H.M., Shalhoub R., Sridharan B.K. The experiences of the community pharmacy team in supporting people with dementia and family carers with medication management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1825–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margusino-Framinan L., Illarro-Uranga A., Lorenzo-Lorenzo K., et al. Pharmaceutical care to hospital outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telepharmacy. Farm Hosp. 2020;44(7):61–65. doi: 10.7399/fh.11498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McConachie S., Martirosov D., Wang B., Desai N., Jarjosa S., Hsaiky L. Surviving the surge: evaluation of early impact of COVID-19 on inpatient pharmacy services at a community teaching hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(23):1994–2002. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng L., Qiu F., Sun S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(2):305–308. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merchan C., Soliman J., Ahuja T., et al. COVID-19 pandemic preparedness: a practical guide from an operational pharmacy perspective. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(19):1598–1605. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguy J., Hitchen S.A., Hort A.L., Huynh C., Rawlins M.D.M. The role of a Coronavirus disease 2019 pharmacist: an Australian perspective. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(5):1379–1384. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ou H.T., Yang Y.H.K. Community pharmacists in Taiwan at the frontline against the novel coronavirus pandemic: gatekeepers for the rationing of personal protective equipment. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(2):149–150. doi: 10.7326/M20-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peláez Bejarano A., Villar Santos P., Robustillo-Cortés MdLA., Sánchez Gómez E., Santos Rubio M.D. Implementation of a novel home delivery service during pandemic. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2021;28:e120–e123. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallis N., Gust C., Porter E., Gilchrist N., Amaral A. Implementation of field hospital pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(19):1547–1551. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yi Z.M., Hu Y., Wang G.R., Zhao R.S. Mapping evidence of pharmacy services for COVID-19 in China. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.555753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuckerman A.D., Patel P.C., Sullivan M., et al. From natural disaster to pandemic: a health-system pharmacy rises to the challenge. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(23):1986–1993. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahuja T., Merchan C., Arnouk S., Cirrone F., Dabestani A., Papadopoulos J. COVID-19 pandemic preparedness: a practical guide from clinical pharmacists' perspective. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(18):1510–1515. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burgess L.H., Cooper M.K., Wiggins E.H., et al. Utilizing pharmacists to optimize medication management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0897190020961655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins C.D., West N., Sudekum D.M., Hecht J.P. Perspectives from the frontline: a pharmacy department's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(17):1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Val J., Sohal G., Sarwar A., Ahmed H., Singh I., Coleman J.J. Investigating the challenges and opportunities for medicines management in an NHS field hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020;28(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dzierba A.L., Pedone T., Patel M.K., et al. Rethinking the drug distribution and medication management model: how a New York city hospital pharmacy department responded to COVID-19. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(8):1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Erstad B.L. Caring for the COVID patient: a clinical pharmacist's perspective. Ann Pharmacother. 2021;55(3):413–414. doi: 10.1177/1060028020954224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferguson N.C., Quinn N.J., Khalique S., Sinnett M., Eisen L., Goriacko P. Clinical pharmacists: an invaluable part of the coronavirus disease 2019 frontline response. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(10) doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garcia-Gil M., Velayos-Amo C. Hospital pharmacist experience in the intensive care unit: plan COVID. Farm Hosp. 2020;44(7):32–35. doi: 10.7399/fh.11510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hussain K., Ambreen G., Muzammil M., Raza S.S., Ali U. Pharmacy services during COVID-19 pandemic: experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital in Pakistan. J Pharm Pol Practice. 2020;13(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H., Zheng S., Liu F., Liu W., Zhao R. Fighting against COVID-19: innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;17(1):1813–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nadeem M.F., Samanta S., Mustafa F. Is the paradigm of community pharmacy practice expected to shift due to COVID-19? Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2046–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee D.H., Watson K.E., Al Hamarneh Y.N. Impact of COVID-19 on frontline pharmacists' roles and services in Canada: the INSPIRE Survey. Can Pharm J. 2021;154(6):368–373. doi: 10.1177/17151635211028253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mullen E., Smith G.H., Irwin A.N., Angeles M. Pandemic H1n1 influenza virus: academy perspectives on pharmacy's critical role in treatment, prevention. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;49(6):728. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09539. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller S., Patel N., Vadala T., Abrons J., Cerulli J. Defining the pharmacist role in the pandemic outbreak of novel H1N1 influenza. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;52(6):763–767. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11003. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burr V. vol. 2. Routledge; London: 2003. (Introduction to Social Constructionism). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crotty M.J. 1998. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang C., Burris M.A. Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schumann R.L., Binder S.B., Greer A. Unseen potential: photovoice methods in hazard and disaster science. Geojournal. 2019;84(1):273–289. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cantarero-Arévalo L., Werremeyer A. Community involvement and awareness raising for better development, access and use of medicines: the transformative potential of photovoice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(12):2062–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pharmacists Association Canadian. https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/scope-of-practice/ Pharmacists' Scope of Practice in Canada [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 November 24]; Available from:

- 69.Statistics Canada https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/fogs-spg/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Dguid=2021A000248&topic=9 Population by Year, by Province and Territory. [cited 2022 30 October]; Available from:

- 70.Alberta College of Pharmacy 2021-22. https://abpharmacy.ca/sites/default/files/2021-22_Annual_Report_WEB.pdf Annual Report. 2021 [cited 2022 30 October]; Available from:

- 71.Hughes C.A., Guirguis L.M., Wong T., Ng K., Ing L., Fisher K. Influence of pharmacy practice on community pharmacists' integration of medication and lab value information from electronic health records. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;51(5):591–598. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.10085. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yuksel N., Eberhart G., Bungard T.J. Prescribing by pharmacists in Alberta. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(22):2126–2132. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schindel T., Yuksel N., Hughes C. In: Encyclopedia of Evidence in Pharmaceutical Public Health and Health Services Research in Pharmacy. ZUD B., editor. Springer International Publishing.; 2022. Prescribing by pharmacists: the Alberta story. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schindel T.J., Yuksel N., Breault R., Daniels J., Varnhagen S., Hughes C.A. Perceptions of pharmacists' roles in the era of expanding scopes of practice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(1):148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsuyuki R.T., Watson K.E. COVID-19 testing by pharmacists. Can Pharm J : CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada : RPC. 2020;153(6):314–315. doi: 10.1177/1715163520961981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watson K.E., Van Haaften D., Horon K., Tsuyuki R.T. The evolution of pharmacists' roles in disasters, from logistics to assessing and prescribing. Can Pharm J. 2020;153(3):129–131. doi: 10.1177/1715163520916921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amin M.E.K., Nørgaard L.S., Cavaco A.M., et al. Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(10):1472–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patterson S.M., Cadogan C.A., Barry H.E., Hughes C.M. ’It stayed there, front and centre’: perspectives on community pharmacy's contribution to front-line healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Northern Ireland. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong L.S., Ram S., Scahill S. Community pharmacists' beliefs about suboptimal practice during the times of COVID-19. Pharmacy. 2022;10(6):140. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy10060140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnston K., O'Reilly C.L., Scholz B., Georgousopoulou E.N., Mitchell I. Burnout and the challenges facing pharmacists during COVID-19: results of a national survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):716–725. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01268-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Safnuk C, Ackman M.L., Schindel T.J., Watson K.E. The COVID conversations: A content analysis of Canadian pharmacy organizations’ communication of pharmacists’ roles and services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott). 2022;156(1):22–31. doi: 10.1177/17151635221139195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Watson K.E. QUT ePrints: Queensland University of Technology; 2019. The Roles of Pharmacists in Disaster Health Management in Natural and Anthropogenic Disasters [Thesis]https://eprints.qut.edu.au/130757/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hayden J.C., Parkin R. The challenges of COVID-19 for community pharmacists and opportunities for the future. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):198–203. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heifetz R.A., Heifetz R., Grashow A., Linsky M. Harvard Business Press; 2009. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heifetz R., Linsky M. Harvard Business Press; 2017. Leadership on the Line, with a New Preface: Staying Alive through the Dangers of Change. [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCourt E.M., Watson K.E., Singleton J.A., Tippett V., Nissen L.M. Are pharmacists willing to work in disasters? Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:540–541. doi: 10.1071/AH20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McCourt E., Singleton J., Tippett V., Nissen L. Disaster preparedness amongst pharmacists and pharmacy students: a systematic literature review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Johnston K., O'Reilly C.L., Scholz B., Mitchell I. The experiences of pharmacists during the global COVID-19 pandemic: a thematic analysis using the jobs demands-resources framework. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18(9):3649–3655. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnston K., O'Reilly C.L., Cooper G., Mitchell I. The burden of COVID-19 on pharmacists. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003 doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.10.013. 2020:S1544-3191(20)30528-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roehl J.M., Harland D.J. Imposter participants: overcoming methodological challenges related to balancing participant privacy with data quality when using online recruitment and data collection. Qual Rep. 2022;27(11) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.