Abstract

Existing culturally competent models of care and guidelines are directing the responses of healthcare providers to culturally diverse populations. However, there is a lack of research into how or if these models and guidelines can be translated into the primary care context of family violence. This systematic review aimed to synthesise published evidence to explore the components of culturally competent primary care response for women experiencing family violence. We define family violence as any form of abuse perpetrated against a woman either by her intimate partner or the partner’s family member. We included English language peer-reviewed articles and grey literature items that explored interactions between culturally diverse women experiencing family violence and their primary care clinicians. We refer women of migrant and refugee backgrounds, Indigenous women and women of ethnic minorities collectively as culturally diverse women. We searched eight electronic databases and websites of Australia-based relevant organisations. Following a critical interpretive synthesis of 28 eligible peer-reviewed articles and 16 grey literature items, we generated 11 components of culturally competent family violence related primary care. In the discussion section, we interpreted our findings using an ecological framework to develop a model of care that provides insights into how components at the primary care practice level should coordinate with components at the primary care provider level to enable efficient support to these women experiencing family violence. The review findings are applicable beyond the family violence primary care context.

Keywords: family violence, primary care, women, Culturally competent, culturally diverse, ethnic minority, Indigenous , migrant and refugee

Family violence includes acts of physical, sexual and psychological violence, and forms of controlling behaviours directed against a family member (Victorian Current Acts, 2008). When such acts of abuse are perpetrated by an intimate partner, it is termed ‘intimate partner violence’ (Devries et al., 2013, p. 1527). In our study, we define family violence as any abusive or controlling behaviours directed against a woman by her former or current spouse or non-marital partner or the partner’s family members such as in-laws. We have chosen the term family violence because the authors are based in Victoria, Australia, where the term is more frequently used at the policy level and is preferred by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Indigenous Australians), and some immigrant and refugee communities (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2010). Primary care is defined here as the non-emergency first point of entry to the healthcare system (Keleher, 2001). General or family practices, maternal and child health care centres, community health care centres and clinics run by allied health care providers such as psychologists and physiotherapists are examples of primary care settings.

Operational Definition of Terms

Women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds are defined as women born outside of their country of residence. It is likely that many women of immigrant and refugee background come from countries where the language is different to the national or spoken language in the country in which they settle. For this review, ethnically diverse refers to women from minority ethnic/racial groups and women from countries where English is not their first language. We do not have a specific definition for Indigenous women as Indigenous people have argued against the use of a formal definition (United Nations, 2009). We acknowledge that the women from different immigrant and refugee backgrounds, Indigenous women and women of ethnic minorities, collectively referred to as culturally diverse women throughout this paper, have unique needs and experiences. In this study, we focus on a common issue faced by these women – a lack of family violence support from their primary care providers that is responsive to their needs.

Prevalence of Family Violence

Globally, 26% of married/partnered women aged 16 years and above have experienced either physical and/or sexual forms of violence from their partners (World Health Organisation, 2021). It is important to note that this global figure may not represent the true prevalence among culturally diverse women because they are at a higher risk of victimisation and of being murdered by their intimate partners (Black et al., 2011; Petrosky et al., 2017; Roy & Marcellus, 2019; Sabri et al., 2018a; Willis, 2011). Individual studies have shown higher rates of intimate partner violence against Indigenous women (40–100%) and women from immigrant backgrounds (17% to 70.5%) (Chmielowska & Fuhr, 2017; Gonçalves & Matos, 2016).

Cultural Diversity and Family Violence

The experiences of culturally diverse women of family violence are often intertwined with experiences of racism, language barriers, inequitable access to healthcare, support services, education, and employment opportunities, and to poor living conditions (Klingspohn, 2018; Vaughan et al., 2016). Compared to non-immigrant women, women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds face additional barriers such as past exposure to torture and war, fear of deportation, language barriers, social isolation and difficulty accessing support services (Amanor-Boadu et al., 2012; Guruge et al., 2010; Vaughan et al., 2016). For Indigenous women, the intergenerational traumatic effects of colonisation that have resulted in inequitable social determinants of health cannot be separated from their experiences of family violence (Klingspohn, 2018). For culturally diverse women, trauma experiences should also be considered along with gender norms, family values and beliefs, and settlement experiences (employment, financial, housing, etc.) to gain a clearer understanding of their situation (Vaughan et al., 2016). Therefore, support systems that can respond to the needs of culturally diverse women experiencing family violence are necessary.

Primary Care and Family Violence

Primary care providers such as general practitioners, or midwives are often the first line of support for women experiencing family violence because such women are at a greater risk for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, gastrointestinal problems, physical injuries, reproductive health problems such as abortions and sexually transmitted infections as a result of exposure to the violence (Campbell, 2002; DHHS, 2019; Usta & Taleb, 2014). In addition to addressing these health issues, primary care providers could provide a safe space for disclosure of experiences of violence and refer women to family violence support agencies (Hegarty & O’Doherty, 2011; Usta & Taleb, 2014). However, cultural beliefs that family violence is a private matter, immigrant women’s negative perception about their primary care providers based on their past experiences in their country of origin and Indigenous women’s lack of trust in non-Indigenous care providers could prevent culturally diverse women from seeking support (Spangaro et al., 2019; Vaughan et al., 2016). If primary care providers could be responsive to these needs, they could provide support before the violence worsens (Usta & Taleb, 2014).

Cultural Competency and Primary Care

A culturally competent primary care system could be an essential source of support for diverse families, a lack of which has been associated with inequitable access to healthcare and resulting differences in healthcare outcomes (Betancourt et al., 2016; National Health and Medical Research Council, 2005). Cultural competence has been defined as a ‘set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural activities’ (Cross et al., 1989, p. 3). Frequently discussed components of cultural competence are awareness of prejudices and stereotypes, knowledge of cultural norms and beliefs, attitudes that respect cultural differences and skills to interact with culturally diverse population (Campinha-Bacote, 2002; Cross et al., 1989; Henderson et al., 2018). Given the wide variation in the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of women and their families, primary care providers’ limited understanding about working with culturally diverse clients experiencing family violence could pose a barrier to effective care provision (Burman et al., 2004; Cross-Sudworth, 2009). Although guidelines on culturally competent care for primary care clinicians are available, they are not specific to the context of family violence (Handtke et al., 2019; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019).

This paper aims to systematically review and summarise the published evidence to identify the components of culturally competent family violence response in primary care. We expect that the results from this review will provide a concrete understanding of how primary care providers can better deliver safe and supportive family violence care to culturally and ethnically diverse women.

Our specific research question is: What components of primary care practice demonstrate cultural competency from the perspective of culturally and ethnically diverse women who experience family violence and/or from the perspective primary care professionals working with these women?

Method

Critical Interpretive Synthesis

We conducted a systematic review using critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) methods. CIS is a review method that allows rigorous and systematic synthesis of evidence from sources that use diverse methodologies. Since our topic is underdeveloped, use of CIS allows us to integrate findings from primary research that uses different methodologies, and from a wide range of grey literature. CIS moves beyond mere aggregation of findings to critical interpretation that is essential to answer our review question (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Schick-Makaroff et al., 2016). In addition, CIS employs theoretical sampling methods to include studies of areas that need further exploration based on author’s decisions (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006). This approach, although, different to the conventional methods used in a systematic review, is central to the CIS method where the authors can decide whether to expand the included literature to aid the development of a theory (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006). Although CIS does not require appraisal of the included studies, we have assessed the quality to enhance the rigour of the study findings by providing an insight into the strength of the evidence (Crowe, 2013). Similarly, we have adhered to a pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and described the search process in detail to increase transparency.

Literature Search

We searched eight academic databases (Ovid Medline, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsychInfo, Sociological Abstract, Proquest Theses and Dissertation Global, CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science) for articles published between January 1970 and July 2019. We used different combinations of the following keywords: ‘intimate partner violence’ or ‘domestic violence’ or ‘spouse abuse’ or ‘wife abuse’ or ‘family violence’ or ‘battered women’” or ‘partner violence’ or ‘gender violence’ or ‘marital rape’ AND ‘cultural competency’ or ‘cultural sensitivity’ or ‘cultural awareness’ or ‘culturally responsive’. For grey literature, we searched international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as the World Health Organization and United Nations-Women, and national NGOs based in Australia (Supplementary File 1). We updated the search in May 2020. We looked at new publications across the eight databases published after our initial search date, consulted our immediate academic networks and examined the references of included studies. While screening the studies obtained from the updated search, in line with the theoretical sampling method used in the CIS, our additional new focus was on studies that explored risk assessment and safety planning for culturally diverse women experiencing family violence (Pokharel et al., 2021). This additional focus was deemed necessary because risk assessment and safety planning were not discussed by any of the studies that were included following the first search.

Study Selection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included peer-reviewed articles that (a) focused on women (cisgender, and transgender women, and women in heterosexual or same sex relationships) 16+ years of age who experience family violence attending a primary care setting or sharing their experiences of interaction with a primary care provider OR primary care providers sharing their experiences of interactions with women experiencing family violence OR children exposed to family violence if the paper discusses primary care responses to women (as parent of the child) and (b) published in the English, Nepali and Hindi languages because one of the study authors was proficient in these languages. Our outcomes of interest were ethnically diverse women’s expectations of care from their primary care providers, practices/processes of primary care providers while interacting with women, and standards/guidelines/frameworks, and conceptual discussion of culturally competent primary care family violence responses.

Since the reviewers are based in Australia, in our review protocol, we acknowledged that significant work could have been done in the area of family violence experienced by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. We proposed that the components of cultural competency generated from these studies would either be treated as a subset or would be incorporated with the findings generated from other studies, based on the number of studies that we find (Pokharel et al., 2020). Similarly, we clarified that the reason we had not limited the inclusion to women from immigrant and refugee backgrounds is because we wanted to include studies that have been conducted in women’s countries of origin. This would give us an understanding of what women’s care expectations from their primary care providers are, when they immigrate to other countries (Pokharel et al., 2020).

This review is situated within a context of a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial that aims to increase identification of and safety planning for, women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence. Therefore, our primary interest is women (Taft et al., 2021).

We excluded studies that focused on children alone, teenagers (< 16 years of age) alone, or men experiencing family violence or female victims of war or community-directed violence. This is because the needs of children and young people as specific patients, and men who are perpetrators/victims as patients are unique, and we may not be able to do them justice within a single review. We did not exclude studies based on study design and methodology.

Inclusion and Exclusion of Grey Literature

In this review, grey literature refers to government reports, non-governmental research reports, clinical guidelines, policy documents, and practice frameworks. Since our preliminary search showed that grey items may not focus on all three concepts central to this study (family violence, primary care, and cultural competency), we included grey literature that focused on at least two of these three concepts. We anticipated that inclusion of grey literature with various foci (primary care and family violence OR family violence and cultural competency OR cultural competency and family violence) would result in a comprehensive understanding of a culturally competent primary care response to family violence.

Study Screening

Two reviewers (BP and SP) simultaneously screened all the titles, abstracts and full text using Covidence software (Covidence, 2020). AT helped to resolve any disagreement for a final decision. For the grey literature, BP created a list of search results and screened, and a final check was done by AT, JY or LH.

Quality Assessment

We used the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) for all peer-reviewed publications (Crowe, 2013). We chose CCAT over other quality assessment tools because it is a valid and reliable tool that can be used for a wide gamut of research designs (Crowe & Sheppard, 2011a; 2011b; Crowe et al., 2012). This allowed us to compare quality assessment scores between studies that would not have been possible if we had used different critical appraisal tools based on study designs. For the grey literature, we used the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date and Significance (AACODS) tool. Since AACODS criteria are specific to grey literature such as policy guidelines and practice frameworks/research reports, we used the AACODS for those documents (Tyndall, 2010). The first author BP appraised the quality of the included studies and grey literature, which was then checked by AT, JY and LH. The studies deemed as low quality were reassessed by AT and JY.

Data Extraction

We extracted data on author, country, research design, country of birth, language spoken, ethnicity of women, types of care providers or primary care setting and summary of the findings.

Data Analysis

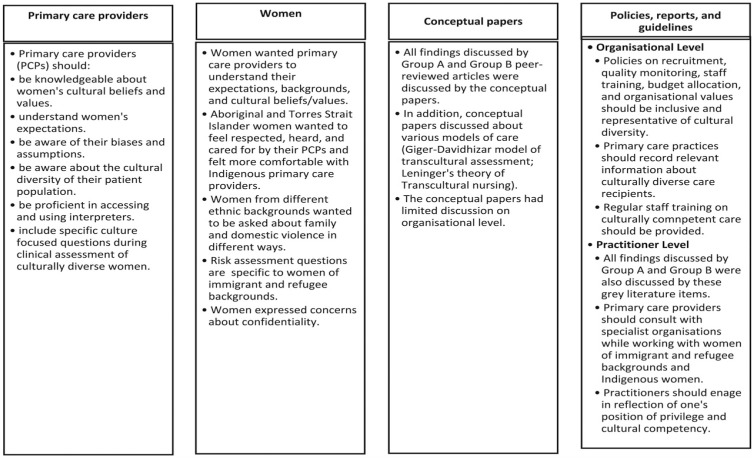

We imported the included studies into NVivo 12.0 (QSR-International, 2020). We then classified studies into groups based on participant types included because we wanted to identify differences in outcome, if any, between the studies that focused on different participant groups or if the studies were grey literature or conceptual papers rather than primary research (Refer to Figure 1). We adopted the five phases of thematic analysis: (a) the reviewer BP read and re-read the included studies to familiarise herself with the data; (b) BP generated the initial codes to identify the semantic content (Refer to Supplementary File 2), and LH, AT and JY provided their feedback on how to best combine these codes; (c) the codes were condensed into broader themes; (d) we (BP, AT, LH and JY) reviewed and refined the themes to generate two recurrent themes and eleven sub-themes that represented the findings from women and their primary care providers and (e) we then decided on the names for these themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The first author is from a South Asian immigrant background, allowing her to bring her cultural knowledge to the interpretation of the literature.

Figure 1.

Critical findings from included studies based on their source of data.

Results

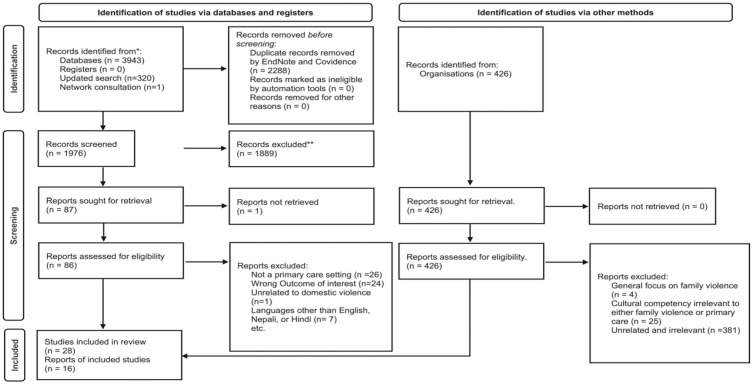

We included 44 records for final analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study selection flowchart (Page et al., 2021)

Study Characteristics

Twenty-eight were peer-reviewed articles and 16 grey literature, and all 16 grey items were published in Australia. Among the 28 peer-reviewed articles, the oldest was published in 1996 and the most recent in 2020. The studies were global, with the majority from the United States of America (n = 17) (Table 1). The included studies were published in the English language.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

| Authors and year | Study type | Types of participants | Types of primary care setting | Characteristics of women included in the study or with whom primary care providers interacteda | Outcomes of quality assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of residence | Women’s country of birth | Women’s background | |||||

| Joe et al. (2020) | Case-vignettes | Women | Unspecified | United States | Not specified | Latina and Black | High qualityb |

| Ashbourne & Baobaid (2019) | Review and critique | Women | Unspecified | United States and Canada | Not specified | Arab | Moderate qualityb |

| Briones-Vozmediano et al. (2019) | Qualitative study | Family doctor, midwife, social worker, sexologist and paediatrician. | Unspecified | Spain | Spain | Roma | High qualityb |

| Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership (2019) | Competency standard framework | Not applicable | Unspecified | Findings applicable to women

from culturally diverse backgrounds [Framework developed in Australia] |

All criteria metc | ||

| Nikparvar (2019) | Qualitative study | Therapists | Unspecified | United States | Iran | Women of immigrant backgrounds | High qualityb |

| Spangaro et al. (2019) | Qualitative study | Women | Antenatal care setting | Australia | Australia | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | High qualityb |

| Briones-Vozmediano et al. (2018) | Qualitative study | Matron, family doctor, sexologist and psychologist. | Unspecified | Spain | Spain | Roma | High qualityb |

| Choahan (2018) | Commentary using interviews | General practitioners | Unspecified | Australia | Unspecified | Women of immigrant backgrounds | All criteria metc |

| Sabri et al. (2018b) | Qualitative study | Women | Unspecified | United States | Not specified | Asian and Latina women. African immigrant women |

High qualityb |

| Alvarez et al. (2018) | Qualitative study | Physicians, nurses, practitioners, midwives, registered nurses, social workers and community health workers | Unspecified | United States | Not specified | Latina and Spanish-speaking immigrant women | High qualityb |

| Garnweidner-Holme et al. (2017) | Qualitative study | Women | Antenatal care setting | Norway | Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan, Poland and Spain | Iraqi, Turkish, Pakistani, Polish and Spanish | Moderate qualityb |

| Vives-Cases et al. (2017) | Qualitative study (Concept mapping study) | Medical physicians and social workers. | Primary healthcare services | Spain | Spain | Roma | High qualityb |

| Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (2016) | Evidence-based factsheet | Women | Unspecified | Australia | Unspecified | Women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds | All criteria metc |

| Northwest Metropolitan Region Primary Care Partnership (2016) | Clinical guidelines | Not applicable | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds | All criteria metc | |||

| Kalapac (2016) | Evaluation report | Professionals providing family violence–related legal and social services; staff implementing family violence work at a hospital. | Unspecified | Australia | Unspecified | Culturally and linguistically diverse women whose first language is not English | All criteria metc |

| Smyth (2016) | Qualitative study | Health visitors | Unspecified | England | Pakistan | Pakistani | High qualityb |

| Banks (2015) | Qualitative study (Hermeneutic phenomenology) | Counsellors | Unspecified | United States | United States | African American | High qualityb |

| Clarke and Boyle (2014) | Discussion paper | Not applicable | Antenatal care setting | Australia | Australia | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women | All criteria metc |

| Taft (2014)/ The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Guidelines on responding to family violence in primary care settings (Group D*) | General practitioners | General practices | Australia | Unspecified | Women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds | All criteria metc |

| Usta et al. (2014) | Qualitative study | Physicians | General practices | Lebanon | Lebanon | Lebanese | Moderate qualityb |

| Messing et al. (2013) | Quantitative study | Women | Not specified | United States | Spain | Spanish immigrant and refugee women | Moderate qualityb |

| Shamu et al. (2013) | Qualitative study | Women; midwives |

Maternity care setting | Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | Shona | Moderate qualityb |

| Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012, 2012a; 2012b; 2012c; 2012d; 2012e, 2012f) | Evidence based tip sheets | All seven

tip sheets were developed using a range of published

evidence – with a focus on enabling culturally competent

healthcare response.[ Tip Sheets developed in Australia] |

All criteria metc | ||||

| Usta et al. (2012) | Qualitative study (Phenomenology | Women | Physician’s clinics | Lebanon | Lebanon | Lebanese | Moderate qualityb |

| Walker et al. (2014) | Book chapter | Not applicable | Mental health are practices | Australia | Australia | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | All criteria metc |

| Aguilar (2011) | Qualitative study (Phenomenology) | Women | Counselling | United States | Unspecified | Latina | High qualityb |

| Chibber et al. (2011) | Qualitative study | Physician | Physician’s clinic | India | India/Indian | High qualityb | |

| Zakar et al. (2011) | Qualitative study | Women | Physician’s clinic | Pakistan | Pakistan | Pakistani | Moderate qualityb |

| Kulwicki et al. (2010) | Qualitative study | Women | Unspecified | United States | Unspecified | Arab | Moderate qualityb |

| Wrangle et al. (2008) | Quantitative study | Primary care providers | Primary care clinic in an urban hospital | United States | Spanish language | Latina | Moderate qualityb |

| Hindin (2006) | Naturalistic inquiry | Midwives | Unspecified | Findings relevant to women from culturally diverse backgrounds | Moderate qualityb | ||

| Immigrant Women’s Domestic Violence Service (2006) | Qualitative study | Women | Rural services | Australia | Unspecified | Immigrant and refugee women | All criteria metc |

| Puri (2005) | Case study | Women; doctors |

Unspecified | United States and Britain | Unspecified | South Asian | High qualityb |

| Thompson (2005) | Discussion paper | Not applicable | Unspecified | Findings relevant to women from

culturally diverse backgrounds [United States of America] |

Low qualityb | ||

| Mehra (2004) | Discussion paper | Not applicable | Dentists | Findings relevant to women from culturally diverse backgrounds | Moderate qualityb | ||

| de Mendoza (2001) | Discussion paper on principles and practice | Not applicable | Nurses | United States of America | Unspecified | Latina women born in the US and immigrant and refugee Latina women | Low qualityb |

| Davidhizar et al. (1998) | Theoretical application of a transcultural model of care | Not applicable | Unspecified | Findings applicable to women

from culturally diverse backgrounds [United States of America] |

Moderate qualityb | ||

| Campbell and Campbell (1996) | Discussion paper | No applicable | Unspecified | Findings applicable to women from culturally diverse backgrounds | Moderate qualityb | ||

Note. aFor studies where the types of participants are specified as primary care providers-Characteristics of women-column of the table refers to women to whom primary care providers delivered family violence–related care.

bQuality assessed using CCAT.

cQuality assessed using AACODS.

Quality Assessment

We divided the CCAT score into three categories: high (31–40), moderate (21–30) and low quality (< 21). Most studies were moderate (n = 13) or high quality (n = 13) and then low (n = 2). We only included moderate quality or high quality studies in our synthesis. All the grey literature met all the AACODS criteria and therefore, was considered high quality. This could be because the sources for grey literature were highly reputed organisations and world-renowned family violence research experts.

The Components of Cultural Competency

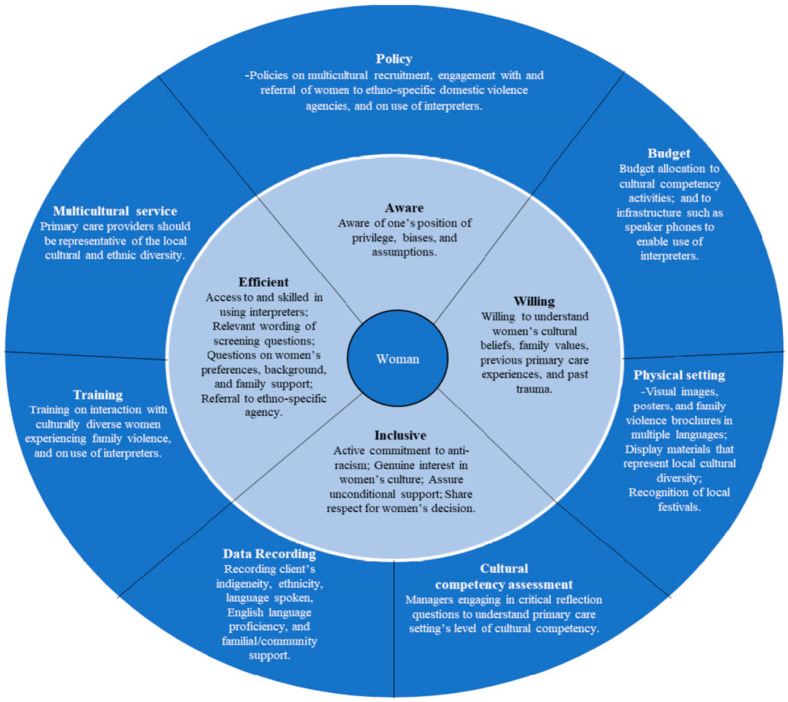

We generated eleven components that demonstrated culturally competent family violence practice at the provider level (four components) and at the whole of practice level (seven components). Please refer to Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A culturally competent primary care family violence response model.

Primary Care Provider Level

Awareness of One’s Biases and Assumptions

Primary care providers can become aware of their own biases and assumptions by first, understanding the privileged position that comes from majority race membership or a higher socioeconomic status (if they so do) (Campbell & Campbell, 1996; Walker et al., 2014). And second, by suspending assumptions about culturally diverse women based on their economic status, educational background, immigration status or ethnic background (Banks, 2015; Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2018; Campbell & Campbell, 1996; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019). For example, selectively screening women for signs of family violence based on a woman’s socio-demographic background or consciously deferring screening in fear of offending her culture (Campbell & Campbell, 1996; Puri, 2005).

Awareness of one’s cultural competence can be further enhanced through self-auditing, a process that requires critical self-reflection (Walker et al., 2014). Walker et al. (2014) have adopted the ‘ASKED’ (Awareness, Skill, Knowledge, Encounters and Desire) mnemonic, originally proposed by Campinha-Bacote (2002) to the context of working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and culturally diverse people. This mnemonic can be adapted by primary care providers to reflect on family violence practice (refer to Table 2). In addition, engaging in self-reflective practice in whatever way possible could also be beneficial (Clarke & Boyle, 2014).

Table 2.

Self-Cultural Competency Assessment.

| Awareness: Am I aware of culturally appropriate and inappropriate actions and attitudes while working with Indigenous women and women of immigrant and refugee. |

| backgrounds experiencing family violence? Does my behaviour or attitudes on family violence reflect a prejudice, bias, or stereotypical mindset? |

| Skill: Do I have the skill to develop and assess my level of cultural competence? What practical experience do I have of family violence? |

| Knowledge: Do I have knowledge of cultural practices, protocols, beliefs, etc. related to family violence? Have I undertaken any cultural development programme that informs me of family violence experiences of Indigenous women and women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds? |

| Encounters: Do I interact with Indigenous women experiencing family violence? Do I interact with women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence? Have I worked alongside Indigenous and women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence? Have I consulted with Indigenous people or culturally and linguistically diverse groups? |

| Desire: Do I really want to become culturally competent? What is my motivation? |

| (Walker et al., 2014, p. 213). |

Willingness to Understand Women’s Background and Their Expectations

Understanding expectations, cultural values and beliefs of culturally diverse women was the most common component discussed in review studies. A willingness to understand, and preferably to have knowledge of, women’s cultural beliefs, family values and expectations of care is important to providing culturally competent responses (Aguilar, 2011; Alvarez et al., 2018; Ashbourne & Baobaid, 2019; Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2019; Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012; Choahan, 2018; Joe et al., 2020; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019; Spangaro et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2014). Studies of US Arab and Iranian immigrant women reported their discontent with the healthcare system’s lack of family-centred responses (Ashbourne & Baobaid, 2019; Nikparvar, 2019).

Women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence face multiple interrelated barriers to care and silencing about their family violence experiences. Health visitors working with Pakistani immigrant women in northern England reported that women were usually accompanied to primary care centres by a family member, requiring conscious efforts to set up a private consultation session with them (Smyth, 2016). Another study of Latina women in the USA found that they experienced challenges such as language barriers, displacement-related trauma, trauma from living in violent communities, separation from family members and a fear of confidentiality breaches when interpreters were from the same community as the women (Alvarez et al., 2018).

Although we found intra-ethnic variations between women’s preferences for their care provider’s gender and ethnic backgrounds, two expectations commonly expressed by women were respect for and genuine interest in their culture (Aguilar, 2011). Knowledge about women’s cultural values, beliefs and expectations can be obtained through interactions with women from various ethnic backgrounds, expressing interest in women’s culture and paying attention to how they describe their family violence situations (Campbell & Campbell, 1996; Mehra, 2004). Learning from colleagues with experience of interacting with diverse women could be a helpful strategy (Smyth, 2016).

Inclusive Values

Continual efforts by primary care providers are necessary to demonstrate inclusive values to culturally diverse women. Awareness of one’s biases and assumptions should be followed by an active commitment to strive against any oppression and racism women face (Campbell & Campbell, 1996). A continual effort towards learning what culturally diverse women find demeaning, and that a woman from an ethnic minority could fear that a clinician from a majority ethnic background could stigmatise her if she discloses family violence is essential (Campbell & Campbell, 1996). Expressing genuine interest in women’s culture is helpful, and this could be communicated by asking women about their background and establishing some sort of common ground (Aguilar, 2011). Questions about women’s immigration status should be best left for the end to avoid alarm since some women may not be legal residents, while others could be concerned about the effects of disclosure on their immigration status (Mehra, 2004). Overall, the aim of primary care providers should be to build trust and create a culturally safe climate to promote disclosure of family violence (Smyth, 2016).

Efficiency in Care Delivery to Women of Various Cultural Backgrounds

Efficiency in care delivery means that when a woman from an immigrant or refugee background or an Indigenous woman seeks family violence support from their primary care providers, the care providers neither feel unprepared nor frustrated; rather, they are knowledgeable and skillful in how to best support the women.

One of the important strategies to achieve efficiency, frequently discussed in the grey literature, was training on access to and use of interpreters (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, 2019; Kalapac, 2016; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019). There could be medico-legal risks if primary care providers fail to either access an interpreter or recognise the need for one (Migrant and Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019b). Several strategies such as timely organisation of an interpreting service, using a pseudonym for the woman, being aware of the woman’s non-verbal cues, creating a code word for safety and avoiding using interpreters from the woman’s community by accessing interstate interpreters would enable safe and efficient use of interpreters (Choahan, 2018; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019; The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2014).

During clinical assessment of culturally diverse women, primary care providers would benefit from the awareness that women from various backgrounds could intimate about their experiences of family violence differently. A study in Zimbabwe revealed that midwives often discover family violence when enquiring about women’s use of contraception or when uncovering family neglect of pregnant women (Shamu et al., 2013). A US study of Spanish speaking Latina women revealed that two screening questions were more sensitive and specific to identify experiences of intimate partner violence among these women: questions about feeling controlled by their partner and/or on feeling lonely in the relationship (Wrangle et al., 2008, p. 265). While screening for family violence, if the primary care provider senses that the woman is hesitant to disclose, asking her in a subsequent visit could be an important strategy (Alvarez et al., 2018; Garnweidner-Holme et al., 2017). Similarly, risk assessment instruments, if available, specific to women from immigrant or refugee backgrounds or Indigenous women would be beneficial, because their vulnerabilities are unique compared to the non-diverse population (Messing et al., 2013; Wrangle et al., 2008).

Safety planning and referral of women experiencing family violence was the least discussed component. The only study that discussed safety planning for culturally diverse women suggested educating immigrant women on the laws and resources of the new country, providing culturally appropriate accommodation (e.g. those that accommodate children and provide culturally appropriate food), providing English language classes and linking women to support groups and networks (Sabri et al., 2018b). Some women even expressed the need to educate the abuser on how to respect women (Sabri et al., 2018b). Referral of culturally diverse women, discussed by a single report, should include linking the women to ethno-specific agencies, if possible (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012c).

Primary Care Practice Level

At this level, seven sub-themes were identified: cultural competency assessment, policy, budget, data recording, physical setting, multicultural service and training (refer to Figure 3).

Cultural Competency Assessment.

Walker et al. (2014, pp. 214–215) propose critically reflective questions to understand an organisation’s cultural competence in service delivery to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons or groups. These questions can be adapted by primary care practices to the working context of family violence and culturally diverse women (refer to Table 3).

Table 3.

Organisational Cultural Competency Assessment.

| Does the primary care practice environment promote and foster a culturally friendly environment? |

| Is it located in an area where Indigenous persons and persons of immigrant and refugee backgrounds may wish to access services? |

| Do the primary care providers display attitudes and behaviours that demonstrate respect for all cultural groups? |

| Does the primary care practice involve or collaborate with Indigenous persons or groups or persons/groups of immigrant and refugee backgrounds when planning events, programmes, service delivery and organisational development activities? |

| Does the practice develop policies and procedures that take cultural matters into consideration? |

| Does the primary care practice provide programmes that encourage participation by Indigenous persons and persons of immigrant and refugee backgrounds? |

| Does the primary care practice use culturally friendly mediums to communicate about family violence? |

| Does the practice have knowledge of local Indigenous and immigrant and refugee groups, protocols of local groups, protocols for communicating with groups including persons of immigrant and refugee backgrounds, and have a strategy for active engagement local culturally diverse groups? |

| Does the practice develop and/or implement a collaborative service delivery model with other family violence support organisations that are relevant to the specific cultural needs of the clients? |

| (Walker et al., 2014, p. 212-214) |

Policy

The findings from grey literature showed that policies, procedures and information should be in place to allow primary care providers to efficiently support culturally diverse women and refer them to appropriate support agencies (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012e). Organisational policy on use of interpreters, culturally competent activities, recruitment of diverse workers, and staff development and organisational investment in infrastructures (e.g. speaker phones) that enable efficient access to interpreters has been suggested (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012b). At the governance level, involvement of multicultural workers that represent the local ethnic diversity in policy development, and planning and monitoring committees could also be an important strategy to increase organisational cultural competence (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012b; 2012e).

Budget

The grey literature recommended that budget allocation to training, infrastructures and other cultural competence activities would enhance cultural competence of an organisation (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012d)

Physical Setting

Physical settings of primary care practices could reflect culturally welcoming environment through visual images and posters in multiple languages that reflect the diversity of their patient population (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012c; Mehra, 2004). Family violence brochures in multiple languages for women of all literacy levels should be made available (Alvarez et al., 2018; Mehra, 2004).

Data Recording

At the primary care practice level, data recording of clinical assessments of culturally diverse women could include the following: (a) Women’s preference of care provider’s gender and ethnic background (Immigrant Women’s Domestic Violence Service, 2006; Smyth, 2016); (b) women’s languages spoken, literacy levels in their first language and in English and need for an interpreter (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012a); (c) family composition, familial support, if cultural beliefs are individual centred or familycentred, community origin (small/emerging), length of time resident in the new country and their current community, and sense of support or belonging to their community (Ashbourne & Baobaid, 2019); and (d) immigration status (permanent residency/temporary residency; visa dependency status; refugee and humanitarian visa) (Ashbourne & Baobaid, 2019; Kalapac, 2016).

Multicultural Service

Employing workers from locally representative ethnic backgrounds could create a culturally safe environment and can provide an insight into how patients from differing cultural backgrounds express themselves and the rituals or traditions they follow (Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2019; Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012)). Consulting with specialist organisations that work with culturally diverse women could be an important strategy (Northwest Metropolitan Primary Care Partnership, 2016).

Training

Training primary care providers in cross-cultural communication, entry and use of the data recorded at the organisational level (refer to data recording) and use of interpreters has been suggested (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, 2019, Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012, Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2012f; Migrant & Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019). For example, primary care practices can use routine recorded data to assess the local cultural diversity, plan multicultural recruitment, develop information materials, and set up interpreters based on the ethnicity and language spoken by the local population.

Overall, our findings showed that culturally competent primary care can be delivered to culturally diverse women through a combination of efforts from primary care settings and the primary care providers.

Discussion

This unique study has for the first-time explored components of a specific culturally competent family violence related primary care response. We generated two main themes: components of cultural competency at the primary care provider level, and at the primary care practice level. In this section, we use an ecological lens to interpret our findings. The ecological model propounded by Bronfenbrenner (1979) was originally proposed to study the interrelationship between a developing child and the constituents of their environment. Since then, the model has been widely adopted and applied to study a range of phenomena, including the healthcare response to family violence (Colombini et al., 2012; García-Moreno et al., 2015; World Health Organisation, 2017). Adding a cultural competency lens to these best practice models, we have proposed a model of care that posits women at the centre and nests components at primary care provider level within those at the primary care practice level (Figure 3).

The components identified at the primary care practice level (cultural competency assessment, policy, training, budget, physical setting, data recording and multicultural service) are consistent with the findings from other studies that have focused on healthcare system responses to family violence (Colombini et al., 2012; Goicolea et al., 2013). A manual released by the World Health Organisation (2017) for health managers recommended that formulating policy frameworks, collecting data to strengthen advocacy and implement accountability, strengthening health workforce, increasing available infrastructures and improving the overall service delivery are important building blocks for designing and planning health system’s response to family violence.

However, this global best practice model lacks a discussion on how these elements can be applied to culturally diverse women who experience additional issues such as systemic racism, language barriers and cultural beliefs that promote silencing about family violence (World Health Organisation 2017). Another study conducted in Spain with middle level managers showed that, although, policy level changes are critical to integrate family violence response into the healthcare system, stakeholders are the ultimate drivers for sustainable integration (Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2018).

Although our review discussed the elements at the primary care practice level, there was scant discussion of how sustainable culturally competent family violence responses can be integrated into the primary care system. A review conducted as a part of a larger study on family violence done across antenatal care settings in Australia recommended that auditing hospital systems is an important step towards understanding sustainability (Hegarty et al., 2020). In this study, similar to our review findings, patient demographics such as country of birth, language spoken, need for an interpreter and referral to an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander services were the report fields used for the audit. A lack of explicit discussion on sustainability in our review could be attributed to the fragmented focus of the included studies on different elements of the healthcare system, as sustainability is an ongoing process that requires interaction between those elements (Gear et al., 2018). In addition, research designs of studies that explore healthcare response to family violence have been reported to have limited or no discussion on sustainability (Gear et al., 2018). Our review did not include studies that discussed national family violence laws, and policies with a cultural competency lens – highlighting the need for further research in this area (Table 4).

Table 4.

Implications for Practice, Policy and Research.

| Implications for policy | Our findings can be used by policymakers to get an insight into the components that need to be integrated an organisational level that enable culturally competent system of primary care. The model can be adopted by umbrella organisations that represent primary care providers such as doctors, nurses and social workers to develop guidelines on responding to culturally diverse women experiencing family violence. |

| Implications for practice | The model can be used by primary care practice to reflect on its current level of cultural competence, design training programmes and to provide a quick visual guide to its practitioners. Also, this review can be a great resource for primary care providers keen to learn time-efficiently about working with culturally diverse women experiencing family violence. |

| Implications for research | This study adds knowledge to an area with a significant gap. In addition, we have identified areas that need further research: (a) Examination of how the components of the proposed model interacts with elements at the national policy level; (b) development and validation of risk assessment instruments for women from various immigrant and refugee backgrounds, and Indigenous women, and LGBTQIA+ identifying women from culturally diverse backgrounds; (c) safety planning specific to women from culturally diverse backgrounds and (d) application of the proposed model to women from various ethnic and racial backgrounds. |

At the primary care provider level, the majority of studies discussed the importance of knowledge about and the willingness to understand culturally diverse women’s beliefs and practices, especially those relevant to family values, and broader communal views on family violence. This is in contrast to the findings reported by a qualitative meta-analysis on women’s expectations from their healthcare providers – where the major theme was kindness and care (Tarzia et al., 2020). This could be attributed to the addition of a cultural competency lens in our review, whereby women repeatedly expressed a need to feel understood – for example, immigrant women wanted to know how the disclosure would affect their visa status, whereas Indigenous women felt that non-Indigenous care providers are in a rush to complete the consultation, rather than going beyond the required policies and procedures to really understand them. In our review, an expectation shared by Arab women and Pakistani women was a need for family-centred family violence responses, especially for families that go through an involuntary migration process. This could be because the refugee experience is often characterised by trauma and torture, and exposure to everyday violence, loss of family members, rape as a weapon of war, and mental health issues – the factors contributing to family violence (Guruge et al., 2010; Vaughan et al., 2016). Further research is warranted on how or if family-centred responses can be delivered as an early intervention for families of refugee backgrounds, and other families from collectivist backgrounds.

Our review proposed a consensus based culturally competent model of primary care response to family violence. Previous studies that have examined primary care response to non-diverse populations have focused on the training needs of primary care providers, especially on recognising experiences of abuse, providing safe space for disclosure, delivering trauma-informed care and self-care (Coles et al., 2013; Decker et al., 2017; Hooker et al., 2021; Sohal et al., 2020). However, these studies do not provide an insight into how these elements interact with women’s ethnicity and their cultural backgrounds. Within and beyond the context of family violence, the expectation that primary care providers should be knowledgeable about women’s culture and beliefs is sometimes reported as challenging and overwhelming due to the vast diversities of the patient population and the resulting variances in needs (Zeh et al., 2018). As a result, discourse on a combination of cultural humility and cultural competence has been suggested (Campinha-Bacote, 2019). On one hand, although a popular concept, cultural competence has often been criticised for quantifying attitudes and skills required to work in a culturally diverse context and undermining its fluidity, cultivating an expectation that competence can be gained in someone else’s culture (Danso, 2018; Dean, 2001; Greene-Moton & Minkler, 2020). Cultural humility, on the other hand, promotes self-critique, lifelong learning commitment and challenges organisational power differentials (Danso, 2018; Murray-Garcia & Tervalon, 1998). Our review findings build on the concept of cultural competence, while including cultural humility as a sub-construct. The critical self-reflective questions that we have proposed (Tables 2 and 3) lean towards cultural humility, but the overall model is still situated within a cultural competence paradigm.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of our review is the breadth of our inclusion criteria. We have included all studies regardless of the study design used and have also included grey literature items. In addition, we have included studies that focus on women, primary care providers, protocols and guidelines of care. This has resulted in a comprehensive examination into the concept of cultural competency in the primary care context of family violence. Although we have used the CIS method, we have appraised the quality of the studies, providing readers an insight into the strength of the evidence. We move beyond mere aggregation of our findings to critical interpretation to generate a model of care. The principles that we discuss could be applicable beyond the primary care context of family violence.

Our review has several limitations. Missing findings on how national elements such as immigration laws, child protection and national family violence policies, and guidelines interact with our findings at primary care provider and practice level limit the application of our study. This could be a focus of future research. Another challenge was integrating findings from sources varied in design, methods and outcomes. To overcome this, we focused on conceptual data analysis to identify key concepts, through multiple reads and examination from multiple perspectives. Since there was no grey literature found that focused on all three concepts (family violence, primary care, and cultural competency), we included studies that focused on at least two of the three concepts. However, we appraised the quality of the grey literature and compared the findings generated from the grey items with those generated from primary studies to identify any notable differences (Figure 1). Although we used the term gender-based violence as a search phrase, we acknowledge that the search terms may not have been sensitive to include studies that focused on nonbinary and two-spirit people. Next, we acknowledge that the proposed model could be broad/too general to offer in-depth guidance to primary care providers interacting with women with complex needs that were not touched on by this review (e.g. women living with disabilities, substance use disorder, etc.). Each element of the proposed model and how it can be applied to the primary care context of women who belong to a particular ethnicity or race deserves further research.

Conclusion

Responding to women experiencing family violence has been perceived as challenging by primary care providers, and cultural diversity adds a layer of complexity that could be a barrier to care provision. However, as society becomes global and the movement of people between countries more common, addressing this barrier becomes more critical. Our review aimed to address the meaning of cultural competency in the family violence primary care context. We identified eleven components that can be adopted by the whole of primary care practice and its care providers. The ecological model that we have proposed, with further research into each of the components, has a potential to create a culturally safe primary care environment, where culturally diverse women can access care, disclose their experiences of family violence and receive care that meets their needs and expectations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-tva-10.1177_15248380211046968 for A Systematic Review of Culturally Competent Family Violence Responses to Women in Primary Care by Bijaya Pokharel, Jane Yelland, Leesa Hooker and Angela Taft in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-tva-10.1177_15248380211046968 for A Systematic Review of Culturally Competent Family Violence Responses to Women in Primary Care by Bijaya Pokharel, Jane Yelland, Leesa Hooker and Angela Taft in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Acknowledgements and Credits

We would acknowledge the help provided by Ange-Johns Hayden, Senior Research Advisor at La Trobe University, during the literature search process. Many Thanks to Mr Sandesh Pantha for his help with the title, abstract and full text screening.

Authors’ Biographies

Bijaya Pokharel (MN BScN) is a Registered Nurse and PhD candidate at the Judith Lumley Centre, La Trobe University. Her PhD focuses on process evaluation of a whole of general practice intervention that aims to improve culturally safe responses to women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence. Her research interests are family violence, cultural competency, primary care, community health nursing, systematic reviews and qualitative research.

Angela Taft is Professor and Principal Research Fellow at the Judith Lumley Centre (JLC), La Trobe University, Australia and an Honorary Senior Fellow in the Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne. She is a social scientist using rigorous combinations of qualitative and epidemiological methods to answer urgent and complex questions about women’s health.

A/Professor Jane Yelland is a Senior Research Fellow and Co-Leader of the Refugee and Migrant Research Program within the Intergenerational Health research group at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. She is Honorary Principal Fellow at The University of Melbourne, Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care Academic Centre. Her team works in partnership with refugee and migrant communities, clinicians and policy makers in the co-design of equity focussed health service reforms.

Dr. Leesa Hooker is a nurse/midwife academic and Senior Research Fellow at the Judith Lumley Centre-La Trobe University, leading the Child, Family and Community Health nursing research stream within the Centre. She has established expertise in the epidemiology of family violence, women’s mental and reproductive health and parenting.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by NHMRC Partnerships in Health Grant No.1134477. Bijaya Pokharel is supported by the La Trobe University Postgraduate Research Scholarship and the La Trobe University Full Fee Research Scholarship.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Bijaya Pokharel  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0792-2553

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0792-2553

Leesa Hooker  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4499-1139

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4499-1139

References

- Aguilar D. R. (2011). Perception of counselor cultural and intimate partner violence competence [ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, University of Denver; ]. https://tinyurl.com/jaksjm4n. As perceived by Latina survivors of IPV [3491076] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez C., Debnam K., Clough A., Alexander K., Glass N. E. (2018). Responding to intimate partner violence: Healthcare providers’ current practices and views on integrating a safety decision aid into primary care settings. Research in Nursing & Health, 41(2), 145-155. 10.1002/nur.21853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanor-Boadu Y., Messing J. T., Stith S. M., Anderson J. R., O’Sullivan C. S., Campbell J. C. (2012). Immigrant and nonimmigrant women: Factors that predict leaving an abusive relationship. Violence Against Women, 18(5), 611-633. 10.1177/1077801212453139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbourne L. M., Baobaid M. (2019). A collectivist perspective for addressing family violence in minority newcomer communities in North America: Culturally integrative family safety responses. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11(2), 315-329. 10.1111/jftr.12332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Law Reform Commission (2010). Concepts of family violence. Retrieved July 10 2020 from https://tinyurl.com/ytcnky4w

- Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (2019). Retrieved November 15 from ASPIRE-interpreters and family violence. https://tinyurl.com/cw6mc5xs. [Google Scholar]

- Banks L. U. (2015). Exploring counselors’ perspectives on domestic violence re-victimization among African. American women Capella University. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt J. R., Green A. R., Carrillo J. E., Owusu Ananeh-Firempong I. (2016). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public health reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. C., Basile K. C., Breiding M. J., Smith S. G., Walters M. L., Merrick M. T., Chen J., Stevens M. R. (2011). The National intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [Google Scholar]

- Briones-Vozmediano E., Castellanos-Torres E., Goicolea I., Vives-Cases C. (2019). Challenges to detecting and addressing intimate partner violence among Roma women in Spain: perspectives of primary care providers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10.1177/0886260519872299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones-Vozmediano E., La Parra-Casado D., Vives-Cases C. (2018. a). Health providers’ narratives on intimate partner violence against Roma women in Spain. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(3-4), 411-420. 10.1002/ajcp.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones-Vozmediano E., Maquibar A., Vives-Cases C., Öhman A., Hurtig A.-K., Goicolea I. (2018. b). Health-sector responses to intimate partner violence: Fitting the response into the biomedical health system or adapting the system to meet the response? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(10), 1653-1678. 10.1177/0886260515619170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burman E., Smailes S. L., Chantler K. (2004). ‘Culture’ as a barrier to service provision and delivery: Domestic violence services for minoritized women. Critical Social Policy, 24(3), 332-357. 10.1177/0261018304044363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9314), 1331-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J., Campbell D. (1996). Cultural competence in the care of abused women. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery, 41(6), 457-462. 10.1016/S0091-2182(96)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. (2002). Cultural competence in psychiatric nursing: Have you “ASKED” the right questions? Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 8(6), 183-187. [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. (2019). Cultural competemility: A paradigm shift in the cultural competence versus cultural humility debate—Part I. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(1). Retrieved from https://ojin.nursingworld.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012. a). Cultural competence in communication. Retrieved December 12 from https://tinyurl.com/4bhdsmse. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012. b). Cultural competence in governance. Retrieved December 12 from https://tinyurl.com/893jpys9. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012. c). Cultural competence in organisational infrastructure. Retrieved December 12 from https://tinyurl.com/avp5v8h5. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012. d). Cultural competence in organsational values. Retrieved December 12 from https://tinyurl.com/v7m64tsk. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (2012. e). Cultural competence in planning, monitoring, and evaluation. Retrieved December 12 from https://tinyurl.com/2f9u2z2r. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health . (2012). Cultural competence in services and interventions. Retrieved December 12 2019 from https://www.ceh.org.au/

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health . (2012. f). Cultural competence in staff development. Retrieved December 12 2019 from https://www.ceh.org.au/

- Chibber K., Krishnan S., Minkler M. (2011). Physician practices in response to intimate partner violence in southern India: insights from a qualitative study. Women Health, 51(2), 168-85. 10.1080/03630242.2010.550993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielowska M., Fuhr D. C. (2017). Intimate partner violence and mental ill health among global populations of Indigenous women: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 689-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choahan N. (2018). Family violence among patients from multicultural backgrounds: How can GPs help? https://www1.racgp.org.au/.

- Clarke M., Boyle J. (2014). Antenatal care for aboriginal and torres strait Islander women. Retrieved December 11 from https://tinyurl.com/42zkp7c7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles J., Dartnall E., Astbury J. (2013). “Preventing the pain” when working with family and sexual violence in primary care. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2013, 198578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombini M., Mayhew S. H., Ali S. H., Shuib R., Watts C. (2012). An integrated health sector response to violence against women in Malaysia: Lessons for supporting scale up. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 548-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Sudworth F. (2009). Ethnicity and domestic abuse: Issues for midwives. British Journal of Midwifery, 17(4), 212-215. http://ez.library.latrobe.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=105516416&login.asp&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence . (2020). Better systematic review management. Retrieved 10 Jan 2020 from https://www.covidence.org/

- Cross T. L., Bazron B. J., Dennis K. W., Isaacs M. R. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care. Retrieved February 17 from https://tinyurl.com/86b3ak. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M. (2013) Crowe critical appraisal tool (CCAT) form v1 (4). https://tinyurl.com/axyw8fsx. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M., Sheppard L. (2011. a). A general critical appraisal tool: An evaluation of construct validity. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(12), 1505-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M., Sheppard L. (2011. b). A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M., Sheppard L., Campbell A. (2012). Reliability analysis for a proposed critical appraisal tool demonstrated value for diverse research designs. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(4), 375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danso R. (2018). Cultural competence and cultural humility: A critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 410-430. [Google Scholar]

- Davidhizar R., Dowd S., Giger J. N. (1998). Recognizing abuse in culturally diverse clients. The Health care supervisor, 17(2), 10-20. 10.1097/00126450-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mendoza V. B. (2001). Culturally appropriate care for pregnant Latina women who are victims of domestic violence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 30(6), 579-588. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R. G. (2001). The myth of cross-cultural competence. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 82(6), 623-630. [Google Scholar]

- Decker M. R., Flessa S., Pillai R. V., Dick R. N., Quam J., Cheng D., McDonald-Mosley R., Alexander K. A., Holliday C. N., Miller E. (2017). Implementing trauma-informed partner violence assessment in family planning clinics. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(9), 957-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Heatlh and Human Services (2019). Maternal and child health service practice guidelines. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/maternal-child-health-service-practice-guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Devries K. M., Mak J. Y. T., García-Moreno C., Petzold M., Child J. C., Falder G., Lim S., Bacchus L. J., Engell R. E., Rosenfeld L., Pallitto C., Vos T., Abrahams N., Watts C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), 1527-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M., Cavers D., Agarwal S., Annandale E., Arthur A., Harvey J., Hsu R., Katbamna S., Olsen R., Smith L., Riley R., Sutton A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Hegarty K., d’Oliveira A. F. L., Koziol-McLain J., Colombini M., Feder G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. Lancet, 385(9977), 1567-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnweidner-Holme L. M., Lukasse M., Solheim M., Henriksen L. (2017). Talking about intimate partner violence in multi-cultural antenatal care: A qualitative study of pregnant women’s advice for better communication in South-East Norway. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 123. 10.1186/s12884-017-1308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear C., Eppel E., Koziol-Mclain J. (2018). Utilizing complexity theory to explore sustainable responses to intimate partner violence in health care. Public Management Review, 20(7), 1052-1067. [Google Scholar]

- Goicolea I., Briones-Vozmediano E., Öhman A., Edin K., Minvielle F., Vives-Cases C. (2013). Mapping and exploring health systems’ response to intimate partner violence in Spain. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1162-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves M., Matos M. (2016). Prevalence of violence against immigrant women: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Violence, 31(6), 697-710. 10.1007/s10896-016-9820-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene-Moton E., Minkler M. (2020). Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 142-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruge S., Khanlou N., Gastaldo D. (2010). Intimate male partner violence in the migration process: Intersections of gender, race and class. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1), 103-113. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handtke O., Schilgen B., Mösko M. (2019). Culturally competent healthcare–A scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K., O’Doherty L. (2011). Intimate partner violence–Identification and response in general practice. Australian Family Physician, 40(11), 852-856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K., Spangaro J., Koziol-McLane J., Walsh J., Lee A., Kye-Onanjiri M., Matthews R., Valpied J., Chapman J., Hooker L., McLindon E., Novy K., Spurway K., & f. W. s. Safety (2020). Sustainability of identification and response to domestic violence in antenatal care (The SUSTAIN study). https://tinyurl.com/d8k4j79u. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S., Horne M., Hills R., Kendall E. (2018). Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: A concept analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(4), 590-603. 10.1111/hsc.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindin P. K. (2006). Intimate partner violence screening practices of certified nurse-midwives. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 51(3), 216-221. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker L., Nicholson J., Hegarty K., Ridgway L., Taft A. (2021). Victorian maternal and child health nurses’ family violence practices and training needs: A cross-sectional analysis of routine data. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 27(1), 43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immigrant Women’s Domestic Violence Service (2006). The right to be safe from domestic violence: Immigrant and refugee women in rural Victoria. Retrieved November 15 from https://intouch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/The-right-to-feel-safe-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Joe J. R., Norman A. R., Brown S., Diaz J. (2020). The intersection of HIV and intimate partner violence: An application of relational-cultural theory with Black and Latina women. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 42(1), 32-46. [Google Scholar]

- Kalapac V. (2016). InLanguage, InCulture, InTouch: Integrated model of support for culturally and linguistically diverse women experiencing family violence -Final evaluation report. Jean Hailes for Women’s Health. https://tinyurl.com/cyshh5w5. [Google Scholar]

- Keleher H. (2001). Why primary health care offers a more comprehensive approach to tackling health inequities than primary care. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 7(2), 57-61. [Google Scholar]

- Klingspohn D. M. (2018). The importance of culture in addressing domestic violence for first Nation’s Women. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(JUN), Article 872. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulwicki A., Aswad B., Carmona T., Ballout S. (2010). Barriers in the utilization of domestic violence services among Arab immigrant women: Perceptions of professionals, service providers & community leaders. Journal of Family Violence, 25(8), 727-735. 10.1007/s10896-010-9330-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra V. (2004). Culturally competent responses for identifying and responding to domestic violence in dental care settings. Journal of the California Dental Association, 32(5), 387-395. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-3242807419&partnerID=40&md5=f8af042b9f9a1f7f6745a308c21b18e6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing J. T., Amanor-Boadu Y., Cavanaugh C. E., Glass N. E., Campbell J. C. (2013). Culturally competent intimate partner violence risk assessment: Adapting the danger assessment for immigrant women. Social Work Research, 37(3), 263-275. 10.1093/swr/svt019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Migrant, Refugee Women’s Health Partnership (2019). Culturally responsive clinical practice: Working with people from migrant and refugee backgrounds-competency standards framework for clinicians. https://tinyurl.com/3w67f28t.

- Murray-Garcia J., Tervalon M. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117-125. https://tinyurl.com/mxuw84wz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (2005). Cultural competency in health: A guide for policy, partnerships and participation. https://tinyurl.com/ykajwzuv. [Google Scholar]

- Nikparvar F. (2019). Therapists’ experiences of working with Iranian-Immigrant IPV clients in the United States. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Northwest Metropolitan Primary Care Partnership (2016). Identifying family violence and responding to women and children. Retrieved January 18 from https://tinyurl.com/heh8saam. [Google Scholar]

- Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J. M., Akl E. A., Brennan S. E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J. M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M. M., Li T., Loder E. W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., McGuinness L. A., Moher D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosky E., Blair J. M., Betz C. J., Fowler K. A., Jack S. P. D., Lyons B. H. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in Homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence–United States, 2003-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(28), 741-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel B., Yelland J., Wilson A., Pantha S., Taft A. (2021). Culturally competent primary care response for women of immigrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing family violence: A systematic review protocol. Collegian, 28(3), 333-340. 10.1016/j.colegn.2020.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puri S. (2005). Rhetoric v. reality: The effect of ‘multiculturalism’ on doctors’ responses to battered South Asian women in the United States and Britain. Patterns of Prejudice, 39(4), 416-430. 10.1080/00313220500347873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- QSR-International (2020). NVIVO qualitative data analysis. Retrieved 10 Jan 2020 from https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/about/nvivo

- Roy J., Marcellus S. (2019). Homicide in Canada, 2018. S. Canada. https://tinyurl.com/4z97m7rm. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B., Campbell J. C., Messing J. T. (2018. a). Intimate partner homicides in the United States, 2003-2013: A comparison of immigrants and nonimmigrant victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10.1177/0886260518792249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B., Nnawulezi N., Njie-Carr V. P. S., Messing J., Ward-Lasher A., Alvarez C., Campbell J. C. (2018. b). Multilevel risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence among African, Asian, and Latina immigrant and refugee women: Perceptions of effective safety planning interventions. Race and Social Problems, 10(4), 348-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick-Makaroff K., MacDonald M., MacDonald M., Plummer M., Burgess J., Neander W. (2016). What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health, 3(1), 172-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu S., Abrahams N., Temmerman M., Zarowsky C. (2013). Opportunities and obstacles to screening pregnant women for intimate partner violence during antenatal care in Zimbabwe. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(5), 511-524. 10.1080/13691058.2012.759393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]