Key Points

Question

What is the association between California’s 2013 Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act and utilization of gender-affirming surgery?

Findings

In this population epidemiology study of 25 252 transgender and gender-diverse patients in California vs Washington and Arizona (control states), implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was associated with an absolute 12.1% (95% CI, 10.3%-13.9%) difference in probability of undergoing gender-affirming surgery.

Meaning

A state-level policy prohibiting health plans from discrimination based on gender identity or gender expression was associated with an increase in use of gender-affirming surgery.

Abstract

Importance

Gender-affirming surgery is often beneficial for gender-diverse or -dysphoric patients. Access to gender-affirming surgery is often limited through restrictive legislation and insurance policies.

Objective

To investigate the association between California’s 2013 implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act, which prohibits insurers and health plans from limiting benefits based on a patient’s sex, gender, gender identity, or gender expression, and utilization of gender-affirming surgery among California residents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population epidemiology study of transgender and gender-diverse patients undergoing gender-affirming surgery (facial, chest, and genital surgery) between 2005 and 2019. Utilization of gender-affirming surgery in California before and after implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act in July 2013 was compared with utilization in Washington and Arizona, control states chosen because of geographic similarity and because they expanded Medicaid on the same date as California—January 1, 2014. The date of last follow-up was December 31, 2019.

Exposures

California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act, implemented on July 9, 2013.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Receipt of gender-affirming surgery, defined as undergoing at least 1 facial, chest, or genital procedure.

Results

A total of 25 252 patients (California: n = 17 934 [71%]; control: n = 7328 [29%]) had a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Median ages were 34.0 years in California (with or without gender-affirming surgery), 39 years (IQR, 28-49 years) among those undergoing gender-affirming surgery in control states, and 36 years (IQR, 22-56 years) among those not undergoing gender-affirming surgery in control states. Patients underwent at least 1 gender-affirming surgery within the study period in 2918 (11.6%) admissions—2715 (15.1%) in California vs 203 (2.8%) in control states. There was a statistically significant increase in gender-affirming surgery in the third quarter of July 2013 in California vs control states, coinciding with the timing of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act (P < .001). Implementation of the policy was associated with an absolute 12.1% (95% CI, 10.3%-13.9%; P < .001) increase in the probability of undergoing gender-affirming surgery in California vs control states observed in the subset of insured patients (13.4% [95% CI, 11.5%-15.4%]; P < .001) but not self-pay patients (−22.6% [95% CI, −32.8% to −12.5%]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Implementation in California of its Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was associated with a significant increase in utilization of gender-affirming surgery in California compared with the control states Washington and Arizona. These data might inform state legislative efforts to craft policies preventing discrimination in health coverage for state residents, including transgender and gender-diverse patients.

This population epidemiology study assesses the association of California’s 2013 implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act and utilization of gender-affirming surgery among California residents, compared with residents of the control states of Washington and Arizona.

Introduction

Gender-affirming surgery, broadly consisting of facial, chest, and genital surgery, is considered a vital aspect of gender-affirming care.1,2,3,4 Evidence suggests that gender-affirming surgery decreases feelings of gender dysphoria and rates of depression and suicidal ideation and improves quality of life.5,6,7,8 Additionally, gender-affirming care is cost-effective; transgender and gender-diverse patients without access to this care have higher rates of HIV infection, depression, substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and unemployment.9 Despite its essential role in the overall health of transgender and gender-diverse patients, access to surgery is often limited through restrictive legislation and insurance policies.10

In July 2013, California implemented the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act, prohibiting insurers and health plans in the state from limiting benefits based on a patient’s sex, gender, gender identity, or gender expression.11,12 Implementation of the legislation may have increased access to gender-affirming surgery, although competing factors such as insurance status, geographic distance to care, or models of care may have continued to represent barriers to utilization that mitigated any change in access. Because at least 1.6 million people identify as transgender or gender diverse in the United States,13 with approximately 60% desiring gender-affirming surgery,14 understanding whether policies prohibiting gender-based discrimination in provision of services is a priority for patients, clinicians, and policy makers.

Given the recent wave of proposed state and national laws restricting access to gender-affirming care,15 we sought to analyze the association between California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act and gender-affirming surgery utilization among California residents.

Methods

This study was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board, the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, which all waived informed patient consent for deidentified data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline. All analyses were performed using Stata software version 17 (StataCorp). Data were analyzed from April 2022 to December 2022.

Data Sources and Population

This population epidemiology study used California Department of Health Care Access and Information discharge database data from 2005 to 2019. As a department within the California Health and Human Services Agency, the Office of State-wide Health Planning and Development oversees the collection and dissemination of health care information from licensed practitioners and hospitals within California, resulting in complete capture of all hospital stays for California patients.16 The data were appropriately deidentified with encrypted ID assignments. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes were used to define the population of interest. Specifically, encounters for patients with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria based on the ICD-9 and ICD-10 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1) were included in the analytic cohort. There was no restriction on reasons for encounters. Patients younger than 18 years at the time of an encounter were excluded. Because the policy in question applies to residents of California, patients whose residence information was missing or was not in California were excluded. Patient-specific variables selected for analysis included age, race and ethnicity, sex, and insurance type.

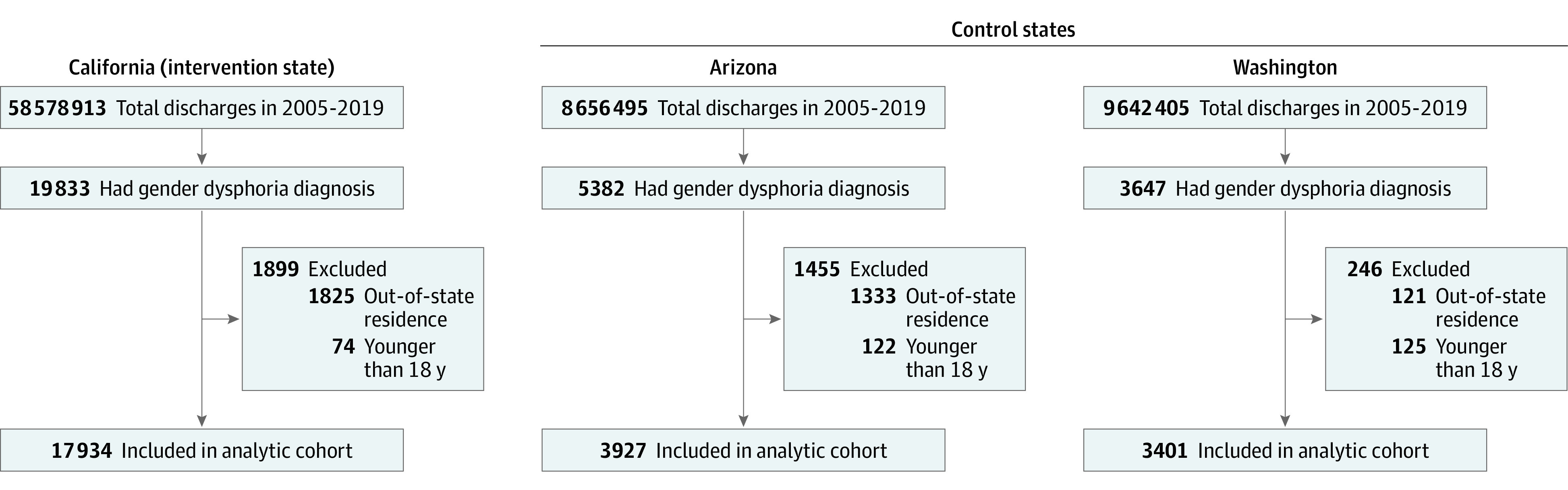

Arizona and Washington were selected as control states because both are geographically close to California and each expanded Medicaid (a policy that may have implications for access to care) on the same date as California—January 1, 2014. The study used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Database data between 2005 and 2019 from both states, comprising clinical and nonclinical variables on all admitted patients regardless of age and insurance status, to identify the control population of patients with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). There was no restriction on reasons for encounters. Patients younger than 18 years at the time of an encounter were excluded. Patients whose residence was outside the state where surgery was performed (ie, Arizona or Washington) were excluded. Patient-specific variables selected for analysis included age, race and ethnicity, sex, and insurance type and were recoded to match data from the California Office of State-wide Health Planning and Development database. Figure 1 shows the number of patients included and excluded during each step of cohort development.

Figure 1. Cohort Selection.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcome was gender-affirming surgery, defined as receipt by any patient in the analytic cohort of at least 1 facial, chest, or genital operation. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 procedure codes were used to identify the outcome of interest (eTables 2-4 in Supplement 1). Two authors (A.S. and A.D.) independently generated the list of procedure codes using previously published studies and publicly available insurance claims documents.17,18 These codes were cross-checked against each other to ensure accuracy.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate association between the California Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act policy and utilization of gender-affirming surgery, descriptive statistics were used to compare patient characteristics between patients who had surgery and those who did not. The date on which health insurance plans had to comply with the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was July 9, 2013. For a significant proportion of the data, only the month and year of admission and/or surgery was available. Due to this limitation, we designated the start of the third quarter of 2013 (July 1, 2013) as the date of intervention.

An interrupted time series analysis was performed to evaluate the association between implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act and gender-affirming surgery. An interrupted time series analysis is a strong quasi-experimental design that tests for level and slope changes in fitted regression lines at the time of interventions. These changes represent potential estimates of the effect of the intervention, assuming that no other events occurred at the time of the intervention that may have affected outcomes with all other factors held constant during this period.19 Outcomes and covariates to the level of quarters were aggregated and fitted to linear regression models to examine immediate level and slope changes in monthly outcomes at the time of implementation. In addition, differences in slope were examined during the preintervention period and postintervention period to assess for potential changes that could have occurred without the implementation of policy. We hypothesized that the intervention would result in an abrupt change following implementation. The preimplementation period was January 1, 2005, to June 30, 2013 (study quarters 1 through 34) and the postimplementation period was July 1, 2013, to December 31, 2019 (study quarters 35 through 64). The statistical significance of any structural breaks in the time series was tested using the Quandt likelihood ratio technique,20 in which we calculated the F statistic on quarterly break points throughout the series.

Linear regression difference-in-differences models were also used to evaluate changes in utilization of surgery among patients with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria who were residing in California vs control states. Linear models provide straightforward estimates of absolute changes, as is typical in difference-in-differences models.21,22 A state binary variable was created for admissions from hospitals in California. A separate post–Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act indicator variable was created if the admission occurred on or after July 1, 2013, the date of the act’s implementation. An interaction term was created between the state and the postreform variable that provided the difference-in-differences estimate for the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act implementation. The difference-in-differences model was adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance (for overall model), and year of encounter. Patient race and ethnicity were defined in the data set as Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, or other. Race and ethnicity were self-reported in the California Department of Health Care Access and Information discharge database and were reported by participating hospitals in the HCUP State Inpatient Databases. Patient payer type was defined as Medicare, Medicaid (Medi-Cal in California), private insurance, self-pay, or other. Parallel trends were assessed in outcomes between states before the third quarter of 2013, which was the key to the validity of the difference-in-differences study design.

All tests were 2-sided and significance was determined by a P < .05.

Results

Overall, 25 252 patients (California: n = 17 934 [71%]; control: n = 7328 [29%]) had a gender dysphoria diagnosis (Figure 1). These patients’ median age was 35 (IQR, 22-52) years; 51.2% identified as female, 46.2% as male, and 2.5% as unknown, missing, or other. Overall, 1716 (6.8%) identified as Asian American and Pacific Islander, 2684 (10.5%) as Black, 4429 (17.5%) as Hispanic, and 14 895 (59%) as White. There were 2918 admissions (11.6%) during which the patient underwent at least 1 gender-affirming surgery within the study period.

In California, 2715 admissions (15.1%) had at least 1 gender-affirming surgery. Median age was similar for those who underwent surgery (34 [IQR, 27-47]) years vs those who did not (34 [IQR, 21-51]) years. A higher proportion of patients who underwent surgery reported their sex as female (surgery: 56.4%; no surgery: 49.4%), reported their race as White (surgery: 59.2%; no surgery: 52.1%), and were privately insured (surgery: 57.1%; no surgery: 31.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristics | California (n = 17 934) | Arizona and Washington (n = 7328) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender-affirming surgery | No gender-affirming surgery | Gender-affirming surgery | No gender-affirming surgery | |

| Total No. (%) | 2715 (15.1) | 15 219 (84.9) | 203 (2.8) | 7125 (97.2) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 34.0 (27.0-47.0) | 34.0 (21.0-51.0) | 39.0 (28.0-49.0) | 36.0 (22.0-56.0) |

| Sex, No. (%)a | ||||

| Female | 1531 (56.4) | 7520 (49.4) | 138 (68.0) | 3753 (52.7) |

| Male | 847 (31.2) | 7600 (49.9) | 30 (14.8) | 3203 (45.0) |

| Unknown, missing, or other | 337 (12.4) | 99 (0.7) | 35 (17.2) | 169 (2.4) |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%)b | ||||

| Asian American and Pacific Islander | 300 (11.0) | 1245 (8.2) | <15 | 163 (2.3) |

| Black | 229 (8.4) | 2121 (13.9) | <15 | 330 (4.6) |

| Hispanic | 460 (16.9) | 3303 (21.7) | <17 (8.4) | 649 (9.1) |

| White | 1607 (59.2) | 7931 (52.1) | 154 (75.9) | 5203 (73.0) |

| Other | 119 (4.4) | 619 (4.1) | 20 (9.9) | 780 (10.9) |

| Insurance, No. (%)c | ||||

| Private | 1551 (57.1) | 4839 (31.8) | 113 (55.7) | 2453 (34.4) |

| Self-pay | 292 (10.8) | 515 (3.4) | 42 (20.7) | 359 (5.0) |

| Medicaid | 596 (22.0) | 5621 (36.9) | 28 (13.8) | 2358 (33.1) |

| Medicare | 233 (8.6) | 3109 (20.4) | <15 | 1705 (23.9) |

| Other | 43 (1.6) | 1135 (7.5) | <15 | 250 (3.5) |

| Type of surgery, No. (%)d | ||||

| Genital | 2148 (79.1) | 158 (77.8) | ||

| Facial | 424 (15.6) | 27 (13.3) | ||

| Chest | 224 (8.3) | 32 (15.8) | ||

Abbreviations: HCUP, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; OSHPD, California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

For OSHPD data, patient biological sex is reported as recorded from patients at admission as female, male, or unknown. Unknown indicates that a patient’s sex was undetermined. It is also used in the case of congenital abnormalities that obscure sex identification. For HCUP data, patient sex (female or male) was provided by the data source.

For OSHPD data, Asian and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander were aggregated into Asian American and Pacific Islander. Due to low values, American Indian and Alaska Native, multiracial, and other race were aggregated into the “other” category. For HCUP data, Asian or Pacific Islander was defined as Asian American and Pacific Islander, and Native American and other race were aggregated into the “other” category due to low values and for consistency with OSHPD data.

For OSHPD data, insurance is defined as the type of entity or organization expected to pay the greatest share of a patient’s bill. For the purpose of this study, Medi-Cal is listed as Medicare. Workers’ compensation, county indigent programs, other government, other indigent, and other payer were aggregated into the “other” category. For HCUP data, insurance is defined as the expected primary payer. No charge and “other” were aggregated into the “other” category due to low values and for consistency with OSHPD data.

Percentages add to greater than 100% because some patients had more than 1 type of surgery during the same admission.

In Arizona and Washington, 203 (2.8%) patients underwent at least 1 gender-affirming surgery. Patients who underwent surgery had a slightly higher median age (surgery: 39 [IQR, 28-49] years; no surgery: 36 [IQR, 22-56] years), and a higher proportion reported their sex as female (surgery: 68.0%; no surgery: 52.7%) and had private insurance (surgery: 55.7%; no surgery: 34.4%) (Table 1).

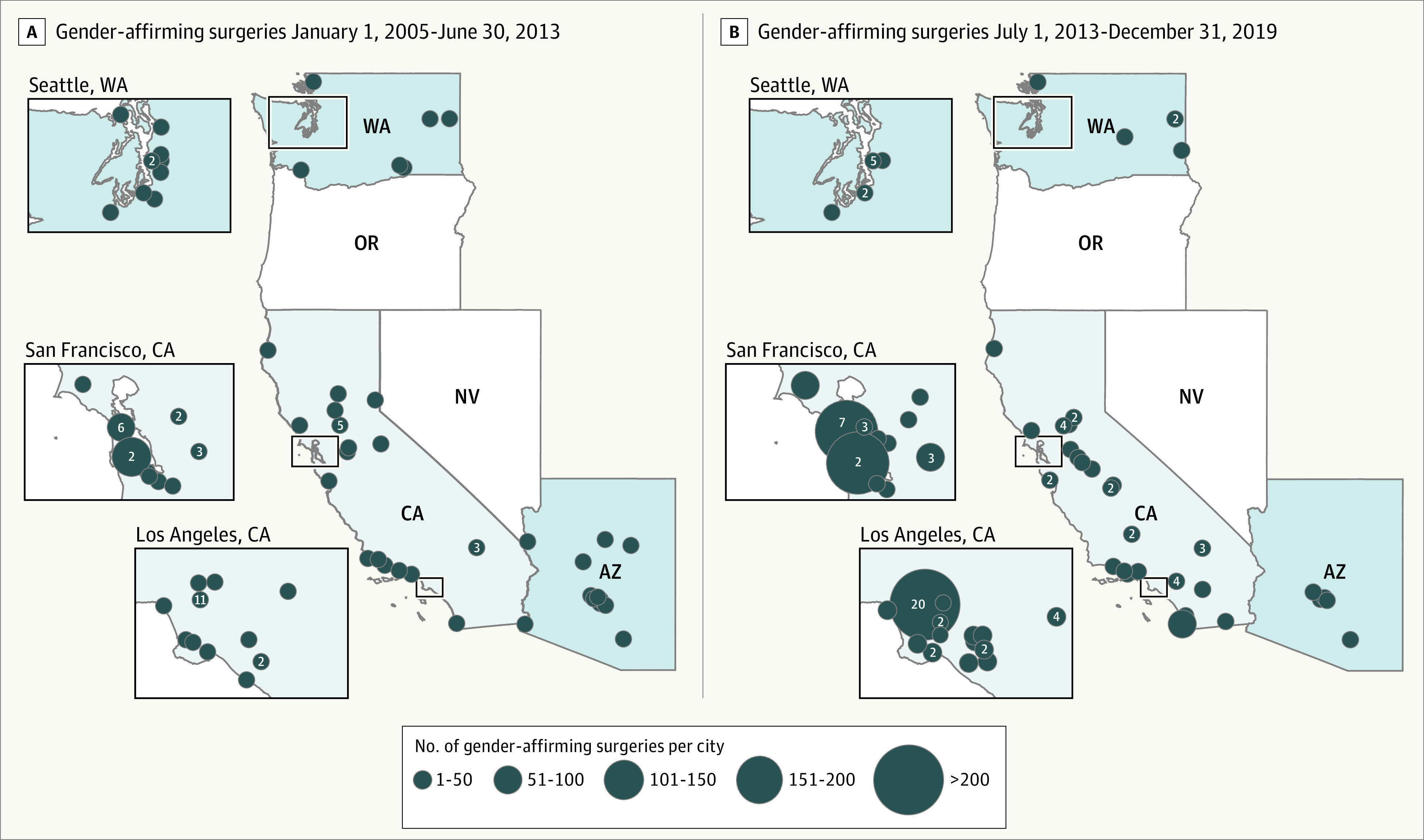

Before implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act, 66 California sites performed a median of 1 (IQR, 1-3) gender-affirming procedures per site vs 106 sites performing procedures with a median of 2 (IQR, 1-4) per site after implementation. In Arizona, 23 sites performed a median of 1 (IQR, 1-2) procedures before implementation, with no change in median procedures per site at 12 sites afterward; in Washington, 16 sites performed a median of 2 (IQR, 1-3) procedures before implementation, with no change in median procedures at 14 sites afterward (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Study State Demographics.

| Demographic characteristics | California | Arizona | Washington |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population, No.a | 39 538 223 | 7 151 502 | 7 705 281 |

| Estimated transgender population aged ≥13 y, No. (%)b | 150 100 (0.49) | 41 200 (0.73) | 33 300 (0.56) |

| No. of gender-affirming surgical sites before policy implementationc | 66 | 23 | 16 |

| No. of surgeries per site before policy implementation, median (IQR)c | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) |

| No. of gender-affirming surgical sites after policy implementationc | 106 | 12 | 14 |

| No. of surgeries per site after policy implementation, median (IQR)c | 2 (1-4) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) |

| Date of Medicaid expansiond | January 1, 2014 | January 1, 2014 | January 1, 2014 |

| Medicaid eligibility limits, % of federal poverty lined | |||

| Before expansion | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| After expansion | 138 | 138 | 138 |

| Medicaid, %d | 27 | 21 | 21 |

| Low income, % | 28 | 32 | 23 |

| Type of Medicaide | Unified state system (Medi-Cal) | Managed care organizations | Managed care organizations |

| No. of Medicaid payerse | 1 | 8 | 5 |

Data are from the 2020 US census (http://data.census.gov).

Data are from the UCLA School of Law Williams Institute (https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/) based on estimates from the 2017-2019 Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Study data. One site performed 94 surgeries before implementation of California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act and 703 surgeries after implementation, leading to highly skewed data.

Data are from the Kaiser Family Foundation (http://kff.org).

Data are from the California Department of Health Care Services (http://www.dhcs.ca.gov), Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (http://www.azahcccs.gov), and Washington State Health Care Authority (http://www.hca.wa.gov).

Figure 2. Location of Gender-Affirming Surgeries in California and Surrounding States Before and After the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act.

A, Prior to the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act (January 1, 2005, to June 30, 2013); B, after the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act (July 1, 2013, to December 31, 2019). The circles represent cities where gender-affirming surgery was performed. The size of the circles represents the number of gender-affirming operations performed. The numbers inside the circles represent the number of facilities in the city; if no number is present, there is only 1 facility in that city. California is the state where the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was passed. Arizona and Washington are the control states where the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was not passed. Nonshaded states were not included in the study.

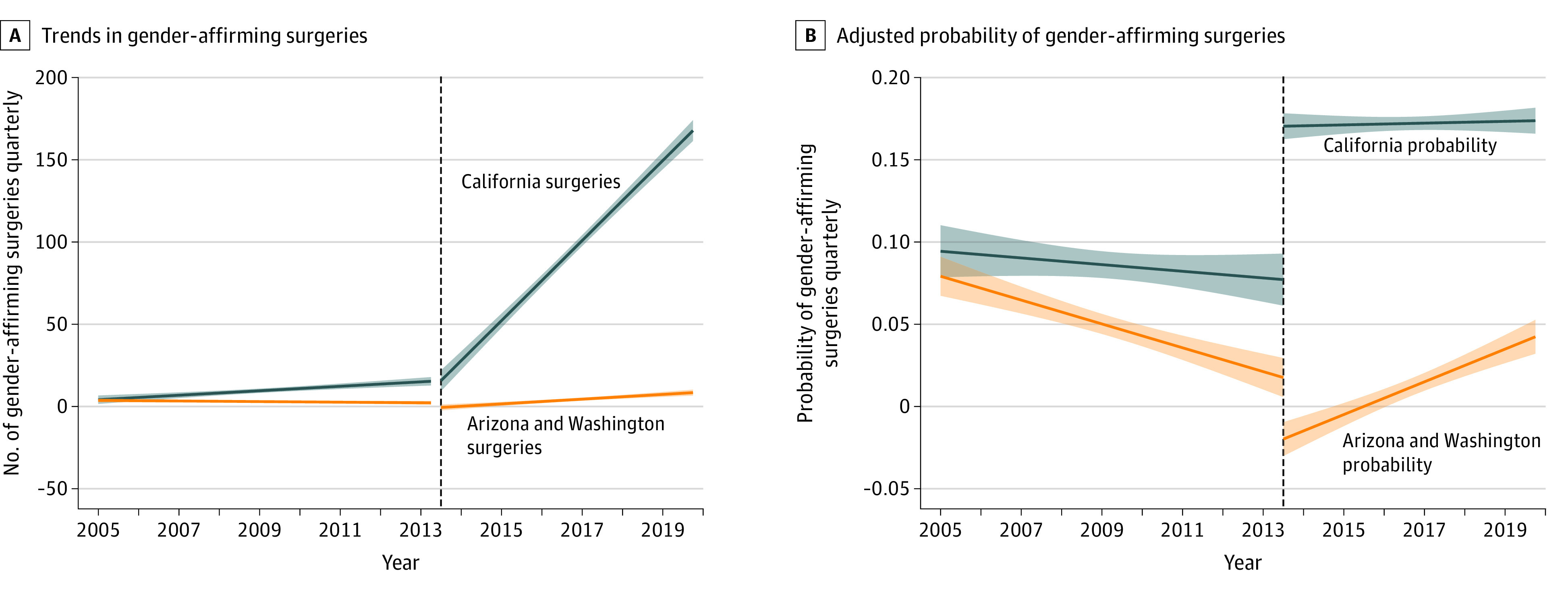

The number of gender-affirming surgeries changed in California compared with control states after policy implementation, with an increase of 5.7 (95% CI, 5.3-6.2) surgeries per quarter compared with 0.41 (95% CI, 0.24-0.57) surgeries per quarter in Arizona and Washington (Figure 3A). Analysis of trends in the probability of undergoing gender-affirming surgery suggest no consistent change in trends from 2005 to 2013, followed by a statistically significant trend break in the third quarter of 2013 (formal Quandt likelihood ratio test, P < .001), coinciding with the implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act (eFigure in Supplement 1).

Figure 3. Modeled Trends in and Adjusted Probability of Total Gender-Affirming Surgeries by Quarter.

A, Solid lines represent the slopes and shaded areas the 95% CIs from the interrupted time series analyses; see Statistical Analysis section of text for the full details of the analysis. The vertical dashed line represents the third quarter of 2013, the date of implementation of California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act. Implementation of the act was associated with an increase of 5.7 (95% CI, 5.3-6.2) surgeries per quarter in California vs 0.41 (95% CI, 0.24-0.57) surgeries per quarter in Arizona and Washington (control states). B, Point estimates and slopes are derived from the difference-in-differences model for probability of undergoing gender-affirming surgery in California vs Arizona and Washington (control states) before and after implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act in the third quarter of 2013 (the vertical dashed line represents the date of policy implementation), adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, and year of encounter. Solid lines represent the slopes and shaded areas the 95% CIs for each group (ie, California vs control states) before and after implementation of the policy.

In difference-in-differences models adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, and year of encounter, trends in probability of gender-affirming surgery were in decline and roughly parallel in California and control states before July 2013, followed by a jump in probability that held steady in California, and a decline in probability that rose to pre–July 2013 levels in control states after July 2013 (Figure 3B), and the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was associated with an absolute 12.1% (95% CI, 10.3-13.9; P < .001) increase in probability of undergoing gender-affirming surgery in California vs the control states (Table 3), observed in the subset of insured patients (13.4% [95% CI, 11.5%-15.4%]; P < .001) but not self-pay patients (−22.6% [95% CI, −32.8% to −12.5%]; P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Change in Probability of Gender-Affirming Surgery Before vs After Implementation of California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act.

| California | Arizona and Washington | Adjusted difference in differences, % (95% CI)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before implementation (n = 4094)a | After implementation (n = 13 840)a | Difference, % (95% CI) | Before implementation (n = 2259)a | After implementation (n = 5069)a | Difference, % (95% CI) | ||||||

| Total surgeries, No. (%) | Adjusted probability (95% CI)b | Total surgeries, No. (%) | Adjusted probability (95% CI)b | Total surgeries, No. (%) | Adjusted probability (95% CI)b | Total surgeries, No. (%) | Adjusted probability (95% CI)b | ||||

| Overall | 331 (8.1) | 12.3 (9.7-14.9) | 2384 (17.2) | 16.2 (15.2-17.1) | 3.9 (0.43 to 7.3) | 101 (4.5) | 8.1 (5.3-10.8) | 102 (2.0) | −0.13 (−1.3 to 1.0) | −8.2 (−11.8 to −4.6) | 12.1 (10.3 to 13.9) |

| Insured | 207 (5.1) | 10.5 (7.5-13.4) | 2216 (16.0) | 16.2 (15.1-17.2) | 5.7 (1.9 to 9.5) | 76 (3.4) | 7.5 (4.4-10.6) | 84 (1.7) | −0.26 (−1.5 to 0.95) | −7.8 (−11.7 to −3.8) | 13.4 (11.5 to 15.4) |

| Self-pay | 124 (3.0) | 40.3 (30.4-50.1) | 168 (1.2) | 36.4 (29.3-43.5) | −3.9 (−2.0 to 12.2) | 17 (0.7) | 25.4 (14.0-36.9) | 25 (0.5) | −1.1 (−8.9 to 6.8) | −26.5 (−44.0 to −9.0) | −22.6 (−32.8 to −12.5) |

The period before implementation of California’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was January 1, 2005, to June 30, 2013; the period after implementation was July 1, 2013, to December 31, 2019.

Model adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance (for overall model), and year of encounter.

Discussion

This study found an increase in the number of centers in California offering gender-affirming surgeries after implementation of the state’s Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act in July 2013, and estimates that the policy implementation was associated with an absolute 12.1% (95% CI, 10.3%-13.9%) increase in the probability of a patient undergoing gender-affirming surgery compared with Arizona and Washington, 2 states that did not implement similar policies. The increase appeared significant among insured patients (ie, with private insurance or Medicaid) but not self-pay patients. The findings suggest that the legislation, which prohibited insurance denial of health care benefits based on patient sex, gender, gender identity, or gender expression, facilitated access to gender-affirming surgery among insured patients with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

Two federal policies are in place to protect transgender and gender-diverse patients from discrimination in accessing health care. Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex (including gender identity) under any health program or activity that receives federal financial assistance,23 although this provision remains the source of ongoing litigation.24,25 Also, section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, under the scope of Title II of the Americans With Disabilities Act, protects individuals with disabilities from discrimination in programs and activities that receive federal assistance; the Department of Health and Human Services states that gender dysphoria may qualify as a disability under this statute.26 The 3 states in this study were subject to these 2 federal policies, but California’s additional implementation of the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act, and our findings suggesting an association of the state legislation with an increase in utilization of gender-affirming surgeries compared with control states, hint at limitations in enforcement of federal policies in states that have not implemented their own gender nondiscrimination insurance policies, perhaps more so in states legislating policies limiting access to gender transition care for transgender and gender-diverse individuals.15

Limitations

The present study has many limitations. First, as with other studies using administrative data, the findings were subject to residual confounding due to unmeasured factors such as noncoded procedures and diagnosis. Nonetheless, we focused on a collection of procedures that are among the most common for patients with gender dysphoria. Second, the present study was limited to the evaluation of a single policy in 1 state and may not be generalizable to other states. However, California is the most populous state to adopt such a policy and as such has the most statistical power to identify a change related to the policy. Such a change in utilization of gender-affirming surgery could reasonably be expected to be replicated in less populous states, albeit at a proportionally smaller volume. Third, the databases underlying the study comparison differed; continuous data for the entire study period for the state of California were not available from HCUP, so the California Department of Health Care Access and Information discharge database was used, with the HCUP database utilized for control states, so findings may be subject to residual confounding from differences between the databases. Fourth, the control states chosen did not have the same baseline number of centers offering gender-affirming surgeries as California; however, the geographic proximity of the control states (Washington and Arizona) to California and the universal Medicaid expansion date among the 3 states justified their selection as controls. Fifth, this study was limited to residents from 3 states undergoing surgery within their respective states and does not evaluate whether patients traveled elsewhere to receive care. Because the purpose of the study was to evaluate a state policy, and insurance is generally administered and regulated by individual states, evaluating whether patients travel outside of their state of residence was beyond the scope of this study but should be evaluated in a future analysis. Sixth, some of the association we observed may be attributable to ecological trends independent of nondiscrimination legislation as gender diversity becomes more recognized in society, especially in states like California. Seventh, as the diagnosis of gender dysphoria and gender-affirming surgery remain controversial, the diagnosis and procedures may be undercoded and underreported.

Conclusions

Implementation in California of its Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act was associated with a significant increase in utilization of gender-affirming surgery in California compared with the control states Washington and Arizona. These data might inform state legislative efforts to craft policies preventing discrimination in health coverage for state residents, including transgender and gender-diverse patients.

eFigure. Quandt Likelihood Ratio of Probability of Gender Affirming Surgery in California by Quarter

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes for Gender Dysphoria

eTable 2. Procedure Codes for Face Surgery

eTable 3. Procedure Codes for Chest Surgery

eTable 4. Procedure Codes for Genital Surgery

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Coleman E, Bouman WP, Brown GR, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(suppl 1):S1-S259. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness . Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association . Position Statement on Access to Care for Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals. Published 2018. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2018-Access-to-Care-for-Transgender-and-Gender-Diverse-Individuals.pdf

- 4.Madara JL. Letter to National Governors Association. American Medical Association. Published 2021. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://searchlf.ama-assn.org/letter/documentDownload?uri=%2Funstructured%2Fbinary%2Fletter%2FLETTERS%2F2021-4-26-Bill-McBride-opposing-anti-trans-bills-Final.pdf

- 5.Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):611-618. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):44-57. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1115753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: a total population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):727-734. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breidenstein A, Hess J, Hadaschik B, Teufel M, Tagay S. Psychosocial resources and quality of life in transgender women following gender-affirming surgery. J Sex Med. 2019;16(10):1672-1680. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padula WV, Heru S, Campbell JD. Societal implications of health insurance coverage for medically necessary services in the US transgender population: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):394-401. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3529-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keith K. HHS will enforce section 1557 to protect LGBTQ people from discrimination. Health Affairs Blog. Published May 11, 2021. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210511.619811/full/

- 11.Brown EG, Barnhart BA. Gender nondiscrimination requirements. California Health and Human Services Agency Department of Managed Health Care. Published April 9, 2013. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://www.dmhc.ca.gov/Portals/0/LawsAndRegulations/DirectorsLettersAndOpinions/dl12k.pdf

- 12.California Department of Insurance . Article 15.1: gender nondiscrimination in health insurance. Published 2012. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/110-health/60-resources/upload/CDI-Gender-Nondiscrimination-Regulations.pdf

- 13.Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? UCLA School of Law; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Published 2011. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf

- 15.American Civil Liberties Union. Legislation affecting LGBTQ rights across the country. Published 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbtq-rights-across-country [Google Scholar]

- 16.California Department of Health Care Access and Information. Reporting Requirements: California Inpatient Data Reporting Manual. Published July 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://hcai.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IP-Reporting-Requirements-July-2022-Published.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canner JK, Harfouch O, Kodadek LM, et al. Temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery among transgender patients in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(7):609-616. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane M, Ives GC, Sluiter EC, et al. Trends in gender-affirming surgery in insured patients in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(4):e1738. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quandt RE. Tests of the hypothesis that a linear regression system obeys two separate regimes. J Am Stat Assoc. 1960;55(290):324-330. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1960.10482067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karaca-Mandic P, Norton EC, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 pt 1):255-274. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2401-2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health and Human Services . Section 1557 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/section-1557/index.html

- 24.Department of Health and Human Services . HHS announces proposed rule to strengthen nondiscrimination in health care. Published July 25, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/07/25/hhs-announces-proposed-rule-to-strengthen-nondiscrimination-in-health-care.html

- 25.Keith K. HHS strips gender identity, sex stereotyping, language access protections from ACA anti-discrimination rule. Health Affairs Blog. Published June 13, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200613.671888/

- 26.Department of Health and Human Services . Discrimination on the basis of disability. Published 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/disability/index.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Quandt Likelihood Ratio of Probability of Gender Affirming Surgery in California by Quarter

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes for Gender Dysphoria

eTable 2. Procedure Codes for Face Surgery

eTable 3. Procedure Codes for Chest Surgery

eTable 4. Procedure Codes for Genital Surgery

Data Sharing Statement