Abstract

Background

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-exacerbated respiratory disease (N-ERD) comprises the triad of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, asthma and intolerance to NSAIDs. Dupilumab treatment, targeting the interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor α, significantly reduces polyp burden as well as asthma symptoms. Here we aimed to investigate the effect of dupilumab on aspirin intolerance, burden of disease and nasal cytokine profiles in patients with N-ERD.

Methods

In this open-label trial, adult patients with confirmed N-ERD were treated with dupilumab for 6 months. Clinical parameters (e.g. total polyp scores, quality of life questionnaires, smell test, spirometry), oral aspirin provocation testing and blood, nasal and urine sampling were monitored at regular intervals for up to 6 months after starting dupilumab therapy.

Results

Of the 31 patients included in the study, 30 completed both aspirin provocation tests. After 6 months of treatment with dupilumab, 23% of patients (n=7 of 30) developed complete aspirin tolerance and an additional 33% of patients (n=10 of 30) tolerated higher doses. Polyp burden was significantly reduced (total polyp score: −2.68±1.84, p<0.001), while pulmonary symptoms (asthma control test: +2.34±3.67, p<0.001) and olfactory performance improved (University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: +11.16±9.54, p<0.001) in all patients after therapy. Patients with increased aspirin tolerance showed a significant decrease in urinary leukotriene E4 levels and their improvement in clinical parameters was associated with a reduction of eotaxin-1, C-C motif chemokine ligand 17, IL-5, IL-17A and IL-6.

Conclusion

In this study, 57% of N-ERD patients tolerated higher doses of aspirin under dupilumab therapy.

Short abstract

Dupilumab improves aspirin hypersensitivity in over 50% of patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease, and clinical improvement was associated with a reduction in nasal biomarkers http://bit.ly/3goVjB1

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-exacerbated respiratory disease (N-ERD) is characterised by the presence of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), asthma and an intolerance towards aspirin or other cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1)-inhibiting NSAIDs [1]. The prevalence is between 0.3% and 0.9% in the general population, yet 7% of asthmatic patients and 10–21% of patients diagnosed with CRSwNP also have N-ERD [2–4]. Affected patients have a severely reduced quality of life (QoL), with chronic nasal obstruction, secretion and an impaired sense of smell being the most burdensome symptoms [5, 6]. Upon ingesting NSAIDs that inhibit the COX-1 enzyme, N-ERD patients experience severe upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms. These are caused by dysregulation of arachidonic acid metabolism with an overproduction of cysteinyl leukotrienes and prostaglandin D2 accompanied by decreased levels of the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [7].

In recent years, biologicals targeting cytokines involved in type 2 inflammation have become available as an important therapeutic option for refractory nasal polyps [8, 9]. Omalizumab, which binds to the Cε3 region of IgE and thus blocks binding of IgE to its receptor present on e.g. mast cells, was the first biological shown to not only reduce nasal polyp burden, but also induce aspirin tolerance in N-ERD patients [10–12]. Dupilumab, targeting the interleukin-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) chain, has become a mainstay therapy for patients with difficult-to-treat nasal polyposis. Treatment significantly reduces polyp size and improves QoL, including improved olfactory function [13, 14]. This is accompanied by a reduction of local eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), eotaxin-3, IL-5 and total IgE levels in nasal secretions [13]. In phase 3 dupilumab studies, self-reported N-ERD patients were included as a subgroup and showed marked improvement in total symptom score and Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22) as compared to aspirin-tolerant subjects [15]. However, the effect of dupilumab on aspirin tolerance has to date not been thoroughly addressed with a prospective study design.

Thus, we conducted a prospective open-label trial in 31 N-ERD patients to investigate the effect of dupilumab on aspirin tolerability before and 6 months after treatment by performing aspirin-challenge testing to optimise recommendations on patients’ NSAID intake. We further sought to verify the impact of dupilumab on polyp size, asthma and QoL in these patients. Additionally, we analysed the effect of dupilumab on 33 different inflammatory biomarkers in nasal secretions of affected patients and on urinary levels of metabolites of the arachidonic acid pathway, and sought to identify differences between patients with dupilumab-induced aspirin tolerance and those who remained aspirin sensitive.

Methods

Study design and patients

This prospective open-label single-centre study was conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and the Department of Dermatology at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria. It was approved by the local ethics committee (EK 1044/2020) and registered at EudraCT (2019–004889–18) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04442256).

All patients signed an informed consent prior to study participation. Inclusion criteria included a minimum age of 18 years and a diagnosis of N-ERD (CRSwNP, asthma, aspirin intolerance).

CRSwNP was diagnosed according to the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020 criteria [16]. Asthma was diagnosed based on the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines [17]. N-ERD was diagnosed by patients’ medical history according to the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology position paper on the diagnosis and management of N-ERD and was confirmed by hypersensitivity reactions to oral aspirin provocation challenge before initiating treatment with dupilumab [18]. For provocation testing, patients needed to have stable asthma and/or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) >70%. Patients were carefully monitored for 24 h in the hospital after a positive reaction to aspirin.

Dupilumab was administered subcutaneously for a total of 6 months, dosed at 300 mg every 2 weeks after a loading dose of 600 mg according to dosage for atopic dermatitis. Patients maintained their usual topical/systemic asthma medication and nasal treatment regimen throughout the study. Concomitant aspirin desensitisation or treatment with other biologicals for CRSwNP or asthma were not permitted.

Study measures

The primary study end-point was the proportion of patients developing tolerance to aspirin as examined at baseline and after the 24-week treatment (supplementary figure E1). Key secondary end-points were change of nasal polyp size (total polyp score (TPS)) [19], disease-specific QoL for CRSwNP measured with SNOT-22 [20], total nasal symptom score (TNSS) and disease-specific QoL for asthma measured with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) score from baseline up to 24 weeks after the start of dupilumab treatment (baseline, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks). Sense of smell was evaluated using the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) at baseline and after 24 weeks [21]. Respiratory parameters were measured by spirometry and included FEV1, maximal expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity (MEF50) and maximal expiratory flow at 75% of forced vital capacity (MEF75) at baseline and after 12 and 24 weeks of therapy. For further information, please refer to the supplementary methods.

Aspirin provocation testing

Aspirin provocation testing was performed at baseline and after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment by oral exposure to aspirin. This was performed in accordance with previously established protocols, starting with a dose of 125 mg that was increased to 250 mg after 2 h; if no reaction occurred, a maximum of 500 mg was given after another 2 h of observation [12]. Vital signs were monitored, and spirometry was performed 30 min before and after each drug intake. Reactions were evaluated by spirometry and/or documentation of clinical nasal or extrapulmonary symptoms. Lower respiratory tract reactions were deemed positive if a decrease in FEV1 >20% was observed. Upper respiratory tract reactions were categorised as positive when symptoms of nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal/eye itching or eye redness/tearing were observed. Combined upper and lower respiratory reactions were categorised as positive when a decrease in FEV1 by at least 20% in the presence of nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal/eye itching or eye redness/tearing occurred.

Subsequent to positive reactions, aspirin provocation testing was stopped, and patients received appropriate symptomatic treatment. Patients were observed for up to 8 h after the last dose of aspirin in order to exclude late anaphylactic reactions.

ELISA, MSD measurements and statistics

Nasal cytokines were assayed via Meso Scale Discovery assays. Levels of nasal IgE and urine leukotriene E4 as well as 11β-prostaglandin F2α were determined by ELISA (supplementary methods).

Results

Induction of aspirin tolerance in N-ERD patients after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment

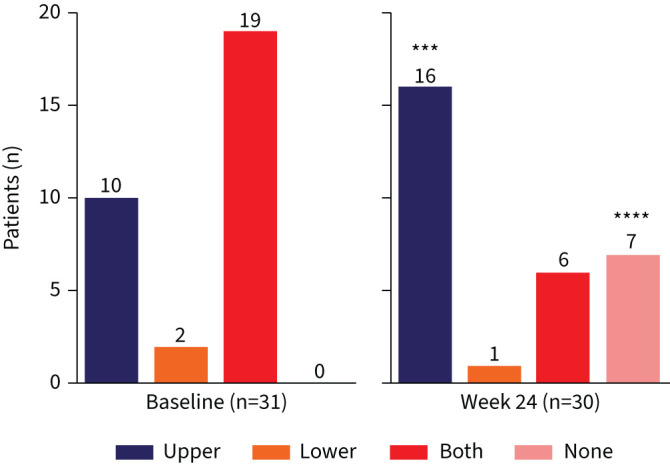

A total of 31 patients with a conclusive history of N-ERD and concomitant symptoms were enrolled, with 30 patients completing aspirin provocation tests both before and after dupilumab treatment (supplementary figure E1b, table 1). At baseline aspirin provocation, the majority of patients (61%, n=19 of 31) presented with a combination of both upper respiratory tract (e.g. nasal congestion, rhinoconjunctivitis or rhinorrhoea) and lower respiratory tract reactions (e.g. pulmonary obstruction, coughing or dyspnoea). An additional 32% of patients (n=10 of 31) showed isolated upper respiratory tract reactions and 6% (n=2 of 31) showed only lower respiratory tract reactions (table 1, figure 1). At baseline, 74% of patients (n=23 of 31) showed respiratory symptoms at a dosage of 125 mg of aspirin, 19% (n=6 of 31) tolerated a cumulative dose of 375 mg and 6% (n=2 of 31) reacted at the highest cumulative doses of 875 mg (table 2). All patients received dupilumab treatment for 6 months. While one patient, who reacted at a cumulative dose of 875 mg of aspirin during the first provocation, was unwilling to perform the second aspirin challenge, 23% (n=7 of 30) of the patients attending the second provocation test tolerated the highest cumulative dosage of 875 mg without showing any signs of hypersensitivity reaction (p<0.001, table 2), i.e. complete aspirin tolerance. An additional 33% of patients (n=10 of 30) tolerated a higher dose at the second challenge, i.e. partial aspirin tolerance. Thus, 57% of patients (n=17 of 30) had reduced NSAID hypersensitivity after 6 months of dupilumab therapy. Of the patients completing a second aspirin provocation test, 40% (n=12 of 30) showed symptoms at the same dosage as in the baseline visit and 3% (n=1 of 30) tolerated less aspirin in the second challenge. In contrast to baseline findings, at the second aspirin provocation patients mainly experienced isolated upper respiratory tract reactions (n=16 of 30, figure 1) and fewer patients experienced both upper and lower respiratory tract reactions (n=6 of 30).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics |

Subjects

(n) |

Baseline |

Subjects

(n) |

Aspirin-intolerant after 6 months treatment with dupilumab |

Subjects

(n) |

Aspirin-tolerant after 6 months treatment with dupilumab | p-value # | |||

| Age, years | 31 | 13 | 17 | ns (p=0.87) | ||||||

| Min–max | 26–70 | 33–63 | 26–70 | |||||||

| Mean | 46.13 | 45.92 | 46.65 | |||||||

| Sex | ns (p=0.25) | |||||||||

| Male | 17 (55%) | 9 (69%) | 7 (41%) | |||||||

| Female | 14 (45%) | 4 (31%) | 10 (59%) | |||||||

| Reaction to aspirin provocation before treatment | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Upper respiratory tract | 31 | 10 (32%) | 21 (68%) | 13 | 3 (23%) | 10 (77%) | 17 | 6 (35%) | 11 (65%) | ns (p=0.35) |

| Lower respiratory tract | 31 | 2 (6%) | 29 (94%) | 13 | 2 (15%) | 11 (85%) | 17 | 0 (0%) | 17 (100%) | ns (p=0.75) |

| Both upper and lower respiratory tract | 31 | 19 (61%) | 12 (39%) | 13 | 8 (62%) | 5 (38%) | 17 | 11 (65%) | 6 (35%) | ns (p=0.21) |

| Comorbidities | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Allergy | 30 | 22 (73%) | 8 (27%) | 13 | 10 (77%) | 3 (23%) | 16 | 11 (69%) | 5 (31%) | ns (p=0.94) |

| Asthma | 31 | 30 (97%) | 1 (3%) | 13 | 12 (92%) | 1 (8%) | 17 | 17 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ns (p=0.89) |

| Number of previous surgeries | 31 | 13 | 17 | p=0.02 | ||||||

| Min–max | 0–6 | 0–3 | 0–6 | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 2.06±1.46 | 1.46±0.97 | 2.65±1.54 | |||||||

| Scores (scale), mean±sd | ||||||||||

| TPS combined (0–8) | 31 | 3.58±2.42 | 13 | 4.46±2.33 | 17 | 2.76±2.28 | ns (p=0.06) | |||

| UPSIT score (0–40) | 30 | 14.70±8.68 | 12 | 13.33±8.62 | 17 | 16.12±8.85 | ns (p=0.24) | |||

| SNOT-22 (0–110) | 30 | 41.43±23.27 | 13 | 46.85±22.34 | 16 | 37.12±24.54 | ns (p=0.28) | |||

| ACT (0–25) | 29 | 21.07±3.85 | 13 | 20.23±2.74 | 15 | 21.53±4.61 | ns (p=0.09) | |||

| FEV1 (%) | 29 | 13 | 15 | ns (p=0.69) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 71.09 (51.13–86.58) | 71.09 (51.13–82.71) | 71.77 (53.00–86.58) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 70.51±8.87 | 71.30±8.58 | 69.88±9.64 | |||||||

| MEF50 (L·s−1) | 29 | 13 | 15 | ns (p=0.60) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 2.29 (0.86–4.31) | 2.29 (0.86–3.33) | 2.23 (1.01–4.31) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 2.40±0.81 | 2.29±0.70 | 2.46±0.93 | |||||||

| MEF75 (L·s−1) | 23 | 9 | 13 | ns (p=0.89) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 4.85 (2.71–9.39) | 4.75 (2.89–6.63) | 4.85 (2.71–9.39) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 4.69±1.48 | 4.60±1.28 | 4.68±1.70 | |||||||

| Biomarkers | ||||||||||

| Total IgE (kU·L−1) | 30 | 12 | 17 | ns (p=0.18) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 194.5 (26.90–1051.00) | 250.5 (62.3–1051.0) | 146.0 (26.9–896.0) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 264.82±264.71 | 362.02±324.97 | 206.79±204.24 | |||||||

| Total IgE from nasal secretion (ng·µL−1) | 31 | 13 | 17 | ns (p=0.06) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 528.87 (65.18–6813.47) | 1652.23 (81.26–6813.47) | 293.60 (65.18–3728.98) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 1389.91±1845.84 | 2275.51±2343.61 | 786.31±1070.86 | |||||||

| Eosinophils (%) | 28 | 11 | 16 | ns (p=0.49) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 4.60 (0.70–12.00) | 6.7 (1.9–9.7) | 4.3 (0.7–12.0) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 5.67±3.00 | 6.30±3.15 | 5.27±3.02 | |||||||

| ECP (μg·L−1) | 23 | 10 | 12 | ns (p=0.82) | ||||||

| Median (min–max) | 39.9 (9.38–200.0) | 47.7 (9.38–109.0) | 38.5 (18.80–200.0) | |||||||

| Mean±sd | 57.23±43.85 | 54.24±31.92 | 61.36±54.32 | |||||||

TPS: total polyp score; UPSIT: University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test; SNOT-22: Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22; ACT: Asthma Control Test; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; MEF50: maximal expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity; MEF75: maximal expiratory flow at 75% of forced vital capacity; ECP: eosinophil cationic protein; ns: nonsignificant. #: from comparison of aspirin-intolerant and aspirin-tolerant patients at baseline.

FIGURE 1.

Different respiratory symptoms in response to oral aspirin provocation before and 24 weeks after dupilumab treatment. Number of patients at each visit and significance of changes between baseline and week 24 are indicated in individual graphs. ***: p<0.001; ****: p<0.0001.

TABLE 2.

Cumulative dose for aspirin provocation at baseline and 24 weeks after dupilumab treatment

| Patient ID | Sex | Age (years) |

Cumulative provoking

aspirin dose (mg) |

|

| Baseline | Week 24 | |||

| Complete aspirin tolerance | ||||

| 001 | M | 54 | 375 | 875 |

| 002 | F | 43 | 125 | 875 |

| 003 | F | 47 | 125 | 875 |

| 004 | F | 31 | 125 | 875 |

| 005 | F | 49 | 375 | 875 |

| 006 | F | 33 | 125 | 875 |

| 007 | F | 48 | 125 | 875 |

| Partial aspirin tolerance | ||||

| 008 | M | 50 | 125 | 375 |

| 009 | F | 27 | 125 | 375 |

| 010 | F | 70 | 125 | 375 |

| 011 | M | 36 | 375 | 875 |

| 012 | M | 43 | 125 | 375 |

| 013 | M | 38 | 125 | 375 |

| 014 | F | 67 | 125 | 375 |

| 015 | M | 68 | 125 | 375 |

| 016 | F | 33 | 125 | 375 |

| 017 | M | 65 | 125 | 375 |

| No aspirin tolerance | ||||

| 018 | M | 40 | 125 | 125 |

| 019 | M | 36 | 125 | 125 |

| 020 | M | 51 | 125 | 125 |

| 021 | F | 47 | 125 | 125 |

| 022 | M | 56 | 375 | 375 |

| 023 | M | 63 | 375 | 375 |

| 024 | M | 33 | 375 | 125 |

| 025 | M | 35 | 125 | 125 |

| 026 | F | 42 | 125 | 125 |

| 027 | M | 51 | 125 | 125 |

| 028 | M | 56 | 125 | 125 |

| 029 | F | 47 | 875 | 875 |

| 030 | F | 45 | 125 | 125 |

| No second provocation | ||||

| 031 | M | 40 | 875 | NA |

M: male; F: female; NA: not applicable.

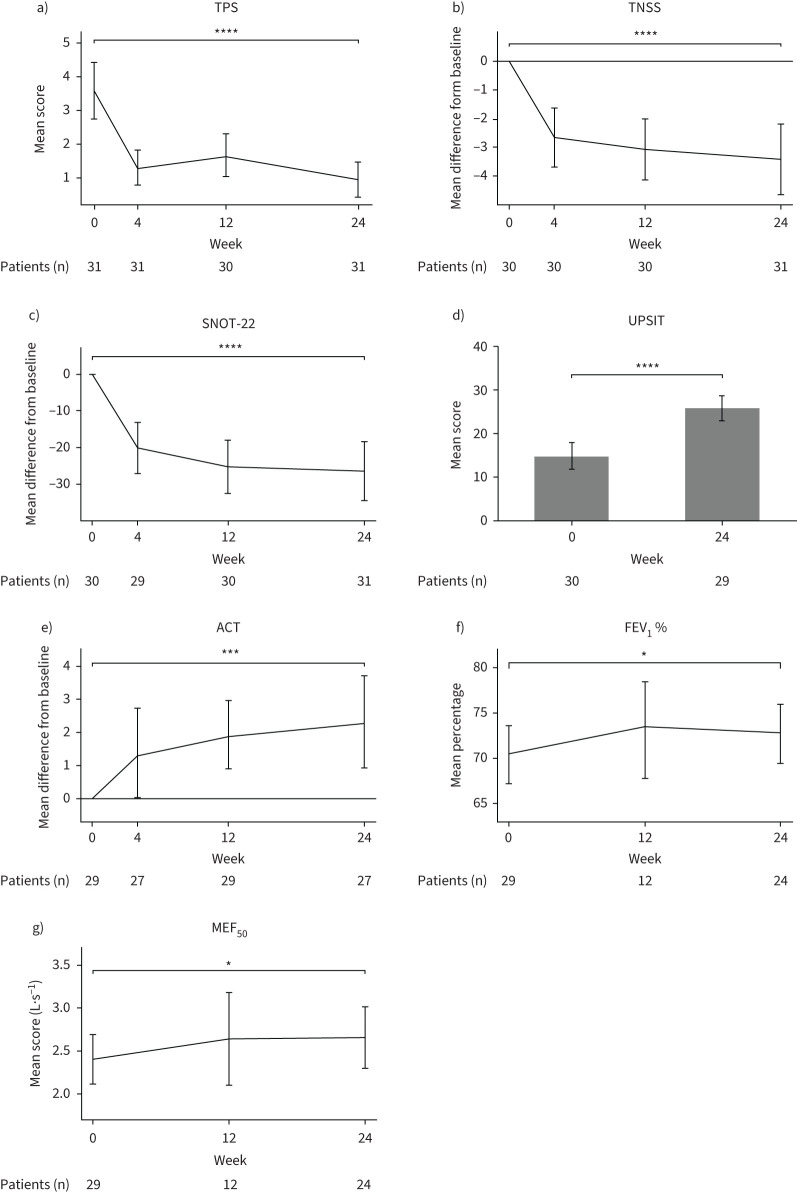

Clinical effectiveness of dupilumab in N-ERD patients

After 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment we observed an overall significant decrease in polyp size (TPS: −2.68±1.84, p<0.001; figure 2a, supplementary table E1). This was accompanied by improved TNSS (−3.46±3.39, p<0.001) and total SNOT-22 levels (−26.73±23.49, p<0.001) as compared to baseline (figure 2b, c). Dupilumab treatment also resulted in better smell perception (UPSIT score: +11.16±9.54, p<0.001, figure 2d) and improvement of asthma symptoms (ACT score: +2.49±3.66, p<0.001, figure 2e). Furthermore, the spirometry-derived parameters FEV1 % predicted (+2.28±5.44%, p=0.01) and MEF50 (+0.26±0.79, p=0.02) showed a trend towards improvement (figure 2f, g). Patients performed better in QoL scores in Patient Health Questionnaire-2 and the Euroqol EQ-5D-3L (supplementary figure E2a–c).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in clinical responses from baseline over time in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease patients during 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. a) Mean of total polyp score (TPS), b) mean difference from baseline in total nasal symptom score (TNSS), c) mean difference from baseline in Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22), d) mean score of University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), e) mean difference from baseline in Asthma Control Test (ACT), f) mean % predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and g) mean score of maximal expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity (MEF50) are displayed at baseline as well as 4, 12 and 24 weeks after treatment where applicable. Number of patients at each visit and significance of changes between baseline and week 24 are indicated in individual graphs. *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001; ****: p<0.0001.

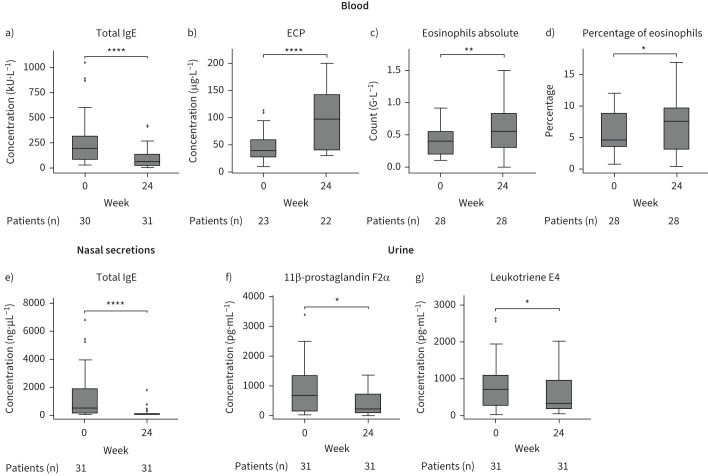

Biomarker changes in serum, urinary and nasal secretions upon dupilumab treatment

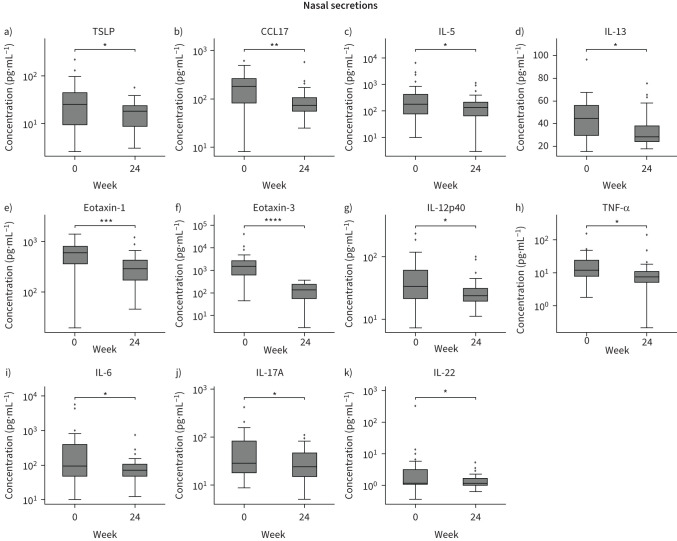

Dupilumab treatment in N-ERD patients was associated with a reduction in total serum IgE levels (−165.13±184.06 kU·L−1, p<0.001; figure 3a, supplementary table E1) and an increase in serum ECP levels (+49.02±48.82 μg·L−1, p<0.001; figure 3b, supplementary table E1) as well as absolute (+0.21±0.35 G·L−1, p=0.003; figure 3c) and percentage (+1.71±4.07%, p=0.01; figure 3d) eosinophil blood levels after 24 weeks. In addition, after 6 months of treatment, we observed a drop in total IgE levels in nasal secretions (−1195.77±1777.02 ng·µL−1, p<0.001; figure 3e). Urinary levels of 11β-prostaglandin F2α (−488.56±943.07 pg·mL−1, p=0.03) as well as leukotriene E4 (−295.19±655.45 pg·mL−1, p=0.02) were also significantly reduced (figure 3f, g, supplementary table E1). Of the 33 biomarkers assessed in nasal secretions, we observed a significant decrease (supplementary table E2) in type 2-associated cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) (figure 4a), C-C chemokine motif ligand 17 (CCL17) (figure 4b), IL-5 (figure 4c) and IL-13 (figure 4d) as well as eotaxin-1 (figure 4e) and eotaxin-3 (figure 4f). The inflammatory cytokines IL-12p40 (figure 4g), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (figure 4h) and IL-6 (figure 4i) as well as T-cell subset-associated cytokines IL-17A (figure 4j) and IL-22 (figure 4k) also decreased over time. For all the other cytokines assessed, no significant differences were observed between week 0 and week 24 of treatment (supplementary figure E3, supplementary table E2).

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of biomarkers in blood and urine of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease patients in response to 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. a–d) Levels of a) total IgE and b) eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) as well as c) absolute (count) and d) percentage of eosinophils in blood at baseline and after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. e) Levels of total IgE in nasal secretions at baseline and after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. f, g) Levels of f) 11β-prostaglandin F2α and g) leukotriene E4 levels in urine at week 0 and 24 of dupilumab treatment. Line within each box represents the median, bottom border represents the 25th percentile and top border the 75th percentile of the data. Whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range and diamond-shaped points are outliers. Number of patients at each visit and significance of changes between baseline and week 24 are indicated in individual graphs. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ****: p<0.0001.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of selected biomarkers in nasal secretions of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease (N-ERD) patients in response to dupilumab treatment. Levels of a) thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), b) C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17), c) interleukin (IL) 5, d) IL-13, e) eotaxin-1, f) eotaxin-3, g) IL-12p40, h) tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), i) IL-6, j) IL-17A and k) IL-22 in N-ERD patients (n=31) are displayed at baseline and after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. Line within each box represents the median, bottom border represents the 25th percentile and top border the 75th percentile of the data. Whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range and diamond-shaped points are outliers. Significance of changes between baseline and week 24 are indicated in individual graphs. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001; ****: p<0.0001.

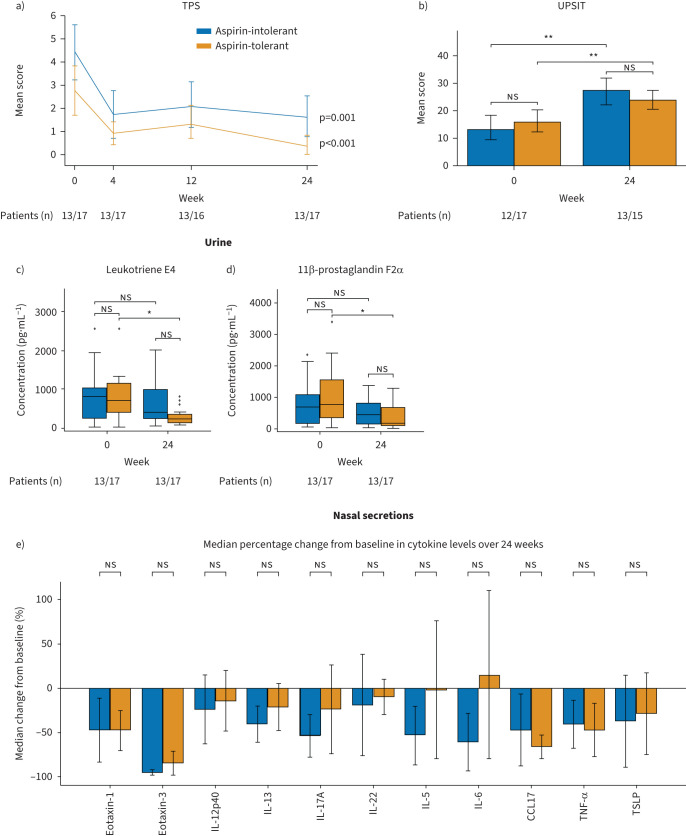

Aspirin-tolerant but not aspirin-intolerant patients show an associated change in clinical parameters with biomarkers

Baseline characteristics of patients who tolerated higher levels of aspirin during the second provocation after 6 months of dupilumab treatment (referred to as aspirin-tolerant) did not differ from those who remained intolerant for aspirin (referred to as aspirin-intolerant) except for the number of previous surgeries at week 0 (meanaspirin−tolerant: 2.65±1.54, meanaspirin-intolerant: 1.46±0.97, p=0.02) (table 1). Dupilumab treatment resulted in a comparable reduction of clinical parameters in both groups after 6 months (figure 5a, b, supplementary figure E2d and data not shown). With regards to biomarkers, the aspirin-tolerant but not the aspirin-intolerant groups showed a significant reduction in urinary leukotriene E4 (meanaspirin-intolerant= −441.81±703.33 pg·mL−1, p=0.02, figure 5c) and 11β-prostaglandin F2α levels (meanaspirin-intolerant= −681.62±1003.91 pg·mL−1, p=0.03, figure 5d) at 24 weeks. Surprisingly, the change in nasal secretion biomarker levels after 6 months of dupilumab administration between groups was comparable, with IL-17A, IL-5 and IL-6 showing a trend towards a stronger reduction in aspirin-intolerant patients and CCL17 showing a trend towards a more pronounced decrease in the aspirin-tolerant patients (figure 5e, supplementary figure E4, supplementary table E2). In an additional analysis differentiating between patients who developed complete aspirin tolerance and those who developed partial aspirin tolerance, as compared to those who remained aspirin-intolerant, we found no difference in TPS or smell performance between the groups (supplementary figure E5). While cytokine levels confirmed previous observations (supplementary figure E6), the patients with partial aspirin tolerance had a trend towards higher baseline leukotriene E4 and 11β-prostaglandin F2α levels and were the only group showing a significant reduction in urinary leukotriene E4 (meanpartial aspirin tolerance= −644.77±773.33 pg·mL−1, p=0.03, supplementary figure E5c) and 11β-prostaglandin F2α levels (meanpartial aspirin tolerance= −951.07±1053.47, p=0.01, supplementary figure E5d) at 24 weeks. However, the statistical results need to be carefully evaluated with regards to the small sample size in the three-group comparison.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of clinical responses and urinary and nasal secretion biomarkers in aspirin-tolerant and aspirin-intolerant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease patients after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. a) Change in total polyp score (TPS) represented as mean score. b) University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) mean score before and after 24 weeks of treatment. c, d) Levels of urinary c) leukotriene E4 and d) 11β-prostaglandin F2α. Line within each box represents the median, bottom border represents the 25th percentile and top border the 75th percentile of the data. Whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range and diamond-shaped points are outliers. e) Median percentage change from baseline of selected biomarkers (cytokines) in nasal secretions. All analyses performed in patients showing aspirin tolerance (orange) or no aspirin tolerance (blue) at the second provocation after 24 weeks of treatment. Significance of changes between baseline and week 24 are indicated in individual graphs. ns: nonsignificant; IL: interleukin; CCL17: C-C motif chemokine ligand 17; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor α; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01.

The decrease in nasal but not urine-derived biomarkers is associated with clinical improvement in aspirin-tolerant patients

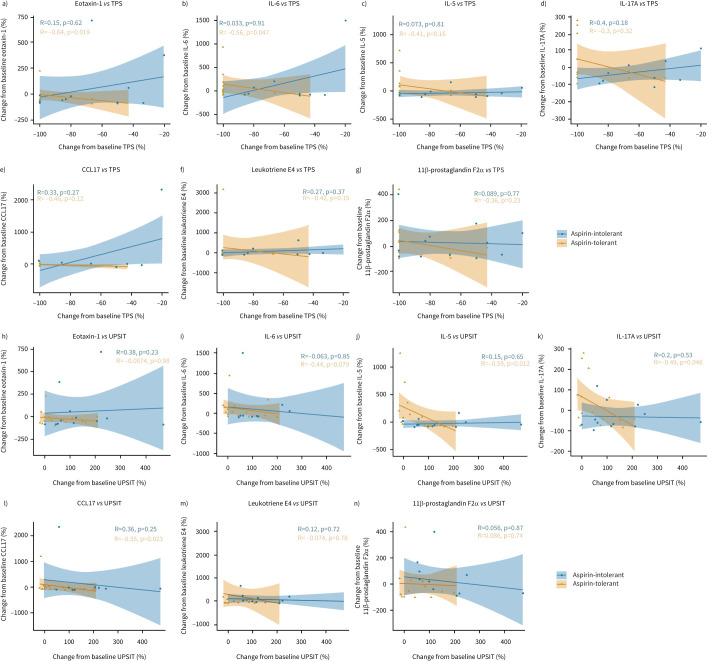

Last, we assessed the association of changes in nasal TPS and UPSIT score with changes in nasal and urinary biomarkers in both the aspirin-tolerant and aspirin-intolerant group after dupilumab treatment. We noted that the decrease in percentage change between end of treatment and baseline for nasal eotaxin-1 (paspirin-tolerant=0.02, paspirin-intolerant=0.62, figure 6a) and IL-6 (paspirin-tolerant=0.05, paspirin-intolerant=0.91, figure 6b) showed an association with the change of TPS from baseline in the aspirin-tolerant group only. This was not the case for the other parameters assessed, namely nasal IL-5 (figure 6c), IL-17A (figure 6d) and CCL17 (figure 6e) or urinary leukotriene E4 (figure 6f) and 11β-prostaglandin F2α (figure 6g) levels. Although no association was found for change in nasal derived eotaxin-1 (figure 6h) or IL-6 (figure 6i) with change in UPSIT score, a moderate negative correlation was observed for change in UPSIT with decreases in nasal-derived IL-5 (paspirin-tolerant=0.01, paspirin-intolerant=0.65, figure 6j), IL-17A (paspirin-tolerant=0.05, paspirin-intolerant=0.53, figure 6k) and CCL17 (paspirin-tolerant=0.02, paspirin-intolerant=0.25, figure 6l) in the aspirin-tolerant group but not the aspirin-intolerant group. Again, urinary biomarkers leukotriene E4 (figure 6m) and 11β-prostaglandin F2α (figure 6n) did not correlate with change in UPSIT levels in any of the two patient groups.

FIGURE 6.

Correlation between clinical parameters and nasal biomarkers in aspirin-tolerant and aspirin-intolerant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease patients after 24 weeks of dupilumab treatment. a–g) Correlation of change from baseline (%) of total polyp score (TPS) versus nasal a) eotaxin-1, b) interleukin (IL) 6, c) IL-5, d) IL-17A and e) C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17) as well as urinary f) leukotriene E4 and g) 11β-prostaglandin F2α. h–n) Correlation of change from baseline (%) of University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) versus nasal h) eotaxin-1, i) IL-6, j) IL-5, k) IL-17A and l) CCL17 as well as urinary m) leukotriene E4 and n) 11β-prostaglandin F2α. Correlation as determined by Spearman correlation coefficient and significance levels are indicated in the figure for aspirin-tolerant (orange, n=17) and aspirin-intolerant (blue, n=13) patients. The respective lines within the scatter plots represent the linearly regressed trend line and the shaded regions the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

In this single-centre prospective open-label study, we demonstrated that treatment with dupilumab in N-ERD patients leads to a significant reduction in polyp size accompanied by an improvement in QoL and smell perception. Importantly, 23% of patients (n=7 of 30) developed a complete tolerance and 33% (n=10 of 30) tolerated higher doses of NSAID after 6 months of dupilumab therapy. Patients showed diminished levels of urinary leukotriene E4 and prostaglandin F2 as well as nasal type 2 response-associated biomarkers after 6 months of treatment. In aspirin-tolerant patients, the improvement in clinical parameters was associated with a reduction in nasal-derived eotaxin-1, CCL17, IL-5, IL-17A and IL-6.

After 6 months of treatment with dupilumab, a reduction in polyp score of −2.68±1.84 points was observed, which is comparable to data from the large multicentre placebo-controlled trials SINUS-24 and SINUS-52 for treatment of CRSwNP with dupilumab [13]. A sub-analysis of the latter studies in N-ERD patients and trials in other N-ERD cohorts also proved the significant impact of dupilumab on polyp burden in this difficult-to-treat patient group [15, 22, 23]. Consistent with previous data we also observed better control of lower airway disease with an improvement in MEF50 (+0.26±0.79 L·s−1) and the ACT score (+2.49±3.66) [24, 25].

Smell perception after 6 months of therapy as measured by UPSIT score improved significantly (+11.16±9.54), which was comparable to results obtained in previous studies with dupilumab in CRSwNP and in N-ERD patients [13, 26, 27]. Although the underlying mechanism is not yet fully understood, it is thought that both the impaired nasal airflow and the direct effect of inflammatory processes on the mucosa and olfactory neurons play a role in olfactory loss in chronic rhinosinusitis [28]. In fact, cytokines associated with type 2 inflammation, which are known to be elevated in N-ERD patients [9, 29], as well as TNF-α have been shown to have a direct negative impact on olfactory neurogenesis and regeneration [30, 31]. In accordance with previous observations in CRSwNP patients without aspirin sensitivity [13, 14], we observed a significant decrease of eotaxin-3 and IL-5 in nasal secretions of dupilumab-treated patients. This reduction was accompanied by an increase in eosinophil levels in the blood, which may be explained by the effect of dupilumab in reducing eosinophil-attracting cytokines, and thus eosinophil migration, into tissue while not affecting production of these cells in the bone marrow [13]. Other type 2 response-associated molecules such as TSLP, CCL17 and IL-13 as well as TNF-α were also decreased after treatment. Interestingly, the reduction of CCL17 and IL-5 showed a significant direct association with smell improvement in patients developing aspirin tolerance during therapy. Our results indicate that the observed ameliorated smell perception after dupilumab therapy may not only be explained by improved nasal patency due to reduced polyp size, but also by the reduction of relevant biomarker levels in nasal secretions.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study reporting the effect of dupilumab on aspirin tolerance in a prospective study design within a representative group of 31 patients with well-defined N-ERD as confirmed by aspirin provocation testing [18]. Overall, we found that 57% of patients tolerated more aspirin after dupilumab therapy, with some of them (23% of all patients) bearing the highest dose. These results are similar to those of a recent small study in five patients, which showed increased (40% of patients) or complete (60% of patients) aspirin tolerance in N-ERD patients after at least 3 months of dupilumab treatment [32]. Furthermore, patients becoming aspirin-tolerant after 6 months showed a trend towards lower baseline TPS score before the start of treatment. Though it did not reach significance, this observation warrants further studies to investigate the influence of the baseline TPS score on patients’ outcome with regards to aspirin tolerance development. Patients who developed dupilumab-induced aspirin tolerance showed a significant reduction in urinary mast cell-derived arachidonic acid metabolites and a trend towards a stronger decrease in nasal CCL17 levels from baseline as compared to subjects who remained aspirin sensitive. The observation that leukotriene C4 synthetase in human mast cells can also be activated by IL-4 may explain the beneficial effect of dupilumab on aspirin sensitivity [33]. However, we can only speculate on why this beneficial effect is only observed in a subset of patients: it is conceivable that the IL-4R-mediated augmentation of leukotriene synthesis may be more prevalent in some of our patients showing dupilumab-induced aspirin tolerance while in others cysteinyl leukotriene synthesis may be more dependent on e.g. IL-3 or IgE receptor-mediated pathway activation [33, 34]. This may also explain the differential results regarding development of full aspirin tolerance with omalizumab, where 56% [12] and 62.5% [11] of patients successfully managed the highest aspirin dose during the challenge after treatment. Omalizumab directly targets activation of mast cells, which are known to be in a hypersensitive state and to play an important role in acute aspirin reactivity in N-ERD patients [11, 12, 35, 36], which ultimately results in a better therapeutic outcome with regards aspirin tolerance using the strategy of IgE inhibition.

The observed reduction in nasal polyp scores with an average TPS of −2.68±1.84 points is more pronounced than the reduction observed with omalizumab in N-ERD patients (TPS −1.9±0.3) [12]. These results are consistent with previous studies suggesting that dupilumab has a stronger effect on polyp size reduction than omalizumab [10, 13, 22, 37, 38]. Furthermore, in a recent comparison of different biological therapies in N-ERD patients, dupilumab led to higher rates of both subjective and objective symptom improvements than anti-IL5/IL-5Rα or anti-IgE therapy [39]. Targeting IL-4Rα, shared by IL-4 and IL-13, might result in a broad inhibition of multiple traits of type 2 responses important in CRSwNP pathogenesis, such as activation of eosinophils, mucus secretion and airway remodelling and, consequently, lead to more pronounced clinical improvement.

The major limitation of this study is the lack of a placebo group. However, because all patients included in this study had a long disease duration, were experiencing poor QoL and had previously unsuccessfully tried other treatment strategies, we felt that it was ethically not justifiable to potentially deny them access to any treatment with biologicals for a period of 6 months. Furthermore, at the time of the study dupilumab was already licensed as treatment for CRSwNP and there is substantial evidence of the effectiveness of dupilumab over placebo in N-ERD [15].

In summary, we show that inhibition of IL-4Rα signalling results in a strong reduction in polyp burden in CRSwNP patients with comorbid N-ERD. This was accompanied by increased aspirin tolerance in 57% of patients. Because dupilumab-induced aspirin tolerance was not achieved in all patients, aspirin challenge is recommended prior to NSAID prescription to determine sensitivity status in N-ERD patients receiving dupilumab. Although the development of aspirin tolerance led to a significant reduction in urine-derived arachidonic acid metabolites involved in N-ERD, biomarkers clearly identifying patients who will respond with aspirin tolerance to different biologicals are still missing and warrant further investigation.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary methods and tables ERJ-01335-2022.Supplement (398.6KB, pdf)

Supplementary figures ERJ-01335-2022.Supplementary_figures (1.7MB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgement

We thank Guenther Regelsberger from the Dept of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna for assistance with MSD measurements.

Footnotes

Author contributions: S. Schneider, C. Bangert, T. Quint and J. Eckl-Dorna designed the study, wrote the study protocol, and gained ethical approval for the study. S. Schneider, K. Poglitsch, T. Quint, K. Gangl, C. Sinz, T. Bartosik, N.J. Campion, D.T. Liu and L.D. Landegger recruited all the patients and carried out the study. A. Tu and V. Stanek performed the experiments. S. Schneider, C. Morgenstern, M. Rocha-Hasler, C. Bangert and J. Eckl-Dorna performed the analysis. S. Schneider, C. Morgenstern, C. Bangert and J. Eckl-Dorna wrote the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript together.

Conflict of interest: S. Schneider served as a speaker and/or consultant and/or advisory board member for Sanofi and Novartis; and is an investigator for Novartis and AstraZeneca (grants paid to his institution). T. Bartosik received personal fees from Sanofi. L.D. Landegger served as an independent consultant for Conclave Capital and Gerson Lehrman Group, is an investigator for Decibel Therapeutics and Amgen (grants paid to his institution), and acts as Chair of the Membership Committee for Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO). M. Rocha-Hasler reports grants from AstraZeneca. C. Bangert has received personal fees from Mylan, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Eli Lilly, Novartis, AstraZeneca and AbbVie, and is an investigator for Novartis, Sanofi, AbbVie, Elli Lilly, LEO Pharma and Galderma (grants paid to her institution). J. Eckl-Dorna served as a speaker and/or consultant and/or advisory board member for Sanofi, Allergopharma, AstraZeneca, GSK, Bencard and Novartis, and is an investigator for Novartis and AstraZeneca (grants paid to her institution). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Support statement: M. Rocha-Hasler was supported by the externally funded research grant NCR-20–20749 of AstraZeneca. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Ledford DK, Wenzel SE, Lockey RF. Aspirin or other nonsteroidal inflammatory agent exacerbated asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2: 653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li KL, Lee AY, Abuzeid WM. Aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Med Sci (Basel) 2019; 7: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan A, Vandeplas G, Huynh TMT, et al. The Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GALEN) rhinosinusitis cohort: a large European cross-sectional study of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without nasal polyps. Rhinology 2019; 57: 32–42. doi: 10.4193/Rhin17.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajan JP, Wineinger NE, Stevenson DD, et al. Prevalence of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease among asthmatic patients: a meta-analysis of the literature. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135: 676–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ta V, White AA. Survey-defined patient experiences with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider S, Campion NJ, Villazala-Merino S, et al. Associations between the quality of life and nasal polyp size in patients suffering from chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps, with nasal polyps or aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 925. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyly A, Laidlaw TM, Lundberg M. Pathomechanisms of AERD – recent advances. Front Allergy 2021; 2: 734733. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2021.734733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens WW, Peters AT, Tan BK, et al. Associations between inflammatory endotypes and clinical presentations in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 2812–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangert C, Villazala-Merino S, Fahrenberger M, et al. Comprehensive analysis of nasal polyps reveals a more pronounced type 2 transcriptomic profile of epithelial cells and mast cells in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Front Immunol 2022; 13: 850494. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.850494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gevaert P, Omachi TA, Corren J, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in nasal polyposis: 2 randomized phase 3 trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 146: 595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi H, Fukutomi Y, Mitsui C, et al. Omalizumab for aspirin hypersensitivity and leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 1488–1498. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1215OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quint T, Dahm V, Ramazanova D, et al. Omalizumab-induced aspirin tolerance in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated respiratory disease patients is independent of atopic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet 2019; 394: 1638–1650. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonstam K, Swanson BN, Mannent LP, et al. Dupilumab reduces local type 2 pro-inflammatory biomarkers in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Allergy 2019; 74: 743–752. doi: 10.1111/all.13685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullol J, Laidlaw TM, Bachert C, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with uncontrolled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and a clinical diagnosis of NSAID-ERD: results from two randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Allergy 2022; 77: 1231–1244. doi: 10.1111/all.15067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020; 58: Suppl. S29, 1–464. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2022. Available from: http://ginasthma.org/

- 18.Kowalski ML, Agache I, Bavbek S, et al. Diagnosis and management of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease (N-ERD) – a EAACI position paper. Allergy 2019; 74: 28–39. doi: 10.1111/all.13599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: developing guidance for clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: Suppl. 5, S17–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann I, Plinkert PK, De Maddalena H. Entwicklung einer Bewertungsskala für den Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-20 German Adapted Version (SNOT-20 GAV) [Development of a grading scale for the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-20 German Adapted Version (SNOT-20 GAV)]. HNO 2008; 56: 784–788. doi: 10.1007/s00106-007-1606-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty RL, Shaman P, Kimmelman CP, et al. University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope 1984; 94: 176–178. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198402000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laidlaw TM, Mullol J, Fan C, et al. Dupilumab improves nasal polyp burden and asthma control in patients with CRSwNP and AERD. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 2462–2465. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertlich M, Ihler F, Bertlich I, et al. Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in Samter triad by low-dose ASA desensitization or dupilumab. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021; 100: e27471. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lans R, Fokkens WJ, Adriaensen G, et al. Real-life observational cohort verifies high efficacy of dupilumab for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Allergy 2022; 77: 670–674. doi: 10.1111/all.15134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laidlaw TM, Bachert C, Amin N, et al. Dupilumab improves upper and lower airway disease control in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021; 126: 584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchheit KM, Sohail A, Hacker J, et al. Rapid and sustained effect of dupilumab on clinical and mechanistic outcomes in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150: 415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullol J, Bachert C, Amin N, et al. Olfactory outcomes with dupilumab in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 1086–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan X, Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Olfaction: sensitive indicator of inflammatory burden in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2020; 5: 992–1002. doi: 10.1002/lio2.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott WC, Cahill KN, Milne GL, et al. Inflammatory heterogeneity in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021: 147; 1318–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rouyar A, Classe M, Gorski R, et al. Type 2/Th2-driven inflammation impairs olfactory sensory neurogenesis in mouse chronic rhinosinusitis model. Allergy 2019; 74: 549–559. doi: 10.1111/all.13559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DK, Choi SA, Eun KM, et al. Tumour necrosis factor α and interleukin-5 inhibit olfactory regeneration via apoptosis of olfactory sphere cells in mice models of allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2019; 49: 1139–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustafa SS, Vadamalai K. Dupilumab increases aspirin tolerance in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021; 126: 738–739. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh FH, Lam BK, Penrose JF, et al. T helper cell type 2 cytokines coordinately regulate immunoglobulin E-dependent cysteinyl leukotriene production by human cord blood-derived mast cells: profound induction of leukotriene C4 synthase expression by interleukin 4. J Exp Med 2001; 193: 123–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lang DM, Aronica MA, Maierson ES, et al. Omalizumab can inhibit respiratory reaction during aspirin desensitization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyce JA. Aspirin sensitivity: lessons in the regulation (and dysregulation) of mast cell function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 144: 875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Sullivan S, Dahlen B, Dahlen SE, et al. Increased urinary excretion of the prostaglandin D2 metabolite 9α, 11β-prostaglandin F2 after aspirin challenge supports mast cell activation in aspirin-induced airway obstruction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996; 98: 421–432. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)70167-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agache I, Song Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals for severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: a systematic review for the EAACI guidelines. Allergy 2021; 76: 2337–2353. doi: 10.1111/all.14809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armengot-Carceller M, Gomez-Gomez MJ, Garcia-Navalon C, et al. Effects of omalizumab treatment in patients with recalcitrant nasal polyposis and mild asthma: a multicenter retrospective study. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2021; 35: 516–524. doi: 10.1177/1945892420972326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wangberg H, Spierling Bagsic SR, Osuna L, et al. Appraisal of the real-world effectiveness of biologic therapies in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary methods and tables ERJ-01335-2022.Supplement (398.6KB, pdf)

Supplementary figures ERJ-01335-2022.Supplementary_figures (1.7MB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-01335-2022.Shareable (386.6KB, pdf)