Key Points

-

•

Patients with mantle cell lymphoma have higher relative risks of respiratory, blood, and infectious disease compared with healthy comparators.

-

•

Late effects varied very little by treatment with or without transplantation.

Abstract

Studies on late effects in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) are becoming increasingly important as survival is improving, and novel targeted drugs are being introduced. However, knowledge about late effects is limited. The aim of this population-based study was to describe the magnitude and panorama of late effects among patients treated with or without high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT). The study cohort included all patients with MCL, recorded in the Swedish Lymphoma Register, aged 18 to 69 years, diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 (N = 620; treated with HD-ASCT, n = 247) and 1:10 matched healthy comparators. Patients and comparators were followed up via the National Patient Register and Cause of Death Register, from 12 months after diagnosis or matching to December 2017. Incidence rate ratios of the numbers of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and bed days were estimated using negative binomial regression models. In relation to the matched comparators, the rate of specialist and hospital visits was significantly higher among patients with MCL. Patients with MCL had especially high relative risks of infectious, respiratory, and blood disorders. Within this observation period, no difference in the rate of these complications, including secondary neoplasms, was observed between patients treated with and without HD-ASCT. Most of the patients died from their lymphoma and not from another cause or treatment complication. Taken together, our results imply that most of the posttreatment health care needs are related to the lymphoma disease itself, thus, indicating the need for more efficient treatment options.

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare but aggressive form of lymphoma affecting older individuals in particular. Since 2001, the Nordic MCL2 protocol (rituximab with dose-intensified cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone [R-CHOP] and high-dose cytarabine followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation [HD-ASCT]) or other regimens, including high-dose cytarabine, are standard options for younger patients.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

In recent trials, novel targeted drugs (such as covalent and noncovalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors and B-cell lymphoma-2 inhibitors)9 are being introduced even in first line, challenging the current use of chemoimmunotherapy with consolidating HD-ASCT.10,11 The benefit of HD-ASCT in MCL is currently under debate.12 Patients with MCL treated with HD-ASCT have shown better progression-free5,6,13, 14, 15, 16 and overall survival17,18 compared with non-HD-ASCT-treated patients but mainly before the era of rituximab maintenance and the role of HD-ASCT in the era of novel targeted drugs is unclear.

The increase in treatment options and improved survival during later years1 calls for updated knowledge about the magnitude and the panorama of late effects in patients with MCL (caused by the cancer itself or by the treatment). Most studies investigating long-term complications and specific causes of death in patients with MCL are based on controlled clinical trials with highly selected patient cohorts. Population-based studies addressing these issues are sparse19,20 and patients treated with HD-ASCT are not always included. Moreover, long-term complications in patients with MCL are rarely compared with the situation among comparators and disentangled from common comorbidities an older population is often facing.

The primary aim of this study was to describe the late effects of MCL in a population-based setting in relation to age- and sex-matched comparators from the general population and to specifically address late events in patients treated with HD-ASCT vs those without. Studies of late effects by different MCL therapies, including the Nordic MCL2 protocol, are of interest as new treatments are introduced and the role of HD-ASCT is questioned21 and may provide a basis for novel treatment strategies and improvements in supportive care and follow-up.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients with MCL aged 18 to 69 years and diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 were identified from the Swedish Lymphoma Register. This register has a coverage of ∼95% compared with the Swedish Cancer Register22 and includes clinical information such as Ann Arbor stage, primary treatment, and the MCL-specific international prognostic index.23 For each patient, 10 population comparators were selected (matched on birth year, sex, and being alive and lymphoma free at the diagnosis date of the patient) from the Register of the Total Population.24 The full cohort (patients and comparators) was further linked to the Swedish Patient Register (nationwide coverage of hospitalizations since 1987 and specialist outpatient coverage since 2001) and the Swedish Cancer Register for classification of comorbidities according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).25 Using the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies, information on the highest achieved educational level was additionally linked. The Swedish Cause of Death Register26 was used to retrieve dates and causes of death.

Stratification of patients based on HD-ASCT

Consolidation with HD-ASCT was identified primarily in the Swedish Lymphoma Register and additionally in the Swedish Patient Register27 (using International Classification of Diseases [ICD] codes, as outlined earlier)28 to assure that all transplantations were captured.29 We used a landmark approach to categorize patients as either HD-ASCT or non-HD-ASCT based on information at 12 months after diagnosis. Patients who had not yet undergone an HD-ASCT at 12 months were regarded as non-HD-ASCT throughout follow-up. Among the patients treated with HD-ASCT, 47% had their transplantation within 6 months of diagnosis and 83% within 12 months, leading us to select a cutoff of 12 months (assuming treatment completion for most patients). Among patients with an HD-ASCT after the landmark, all inpatient visits associated with the transplantation were disregarded. In sensitivity analyses, landmarks at 9, 18, and 24 months after diagnosis were also evaluated because of the occurrence of some late transplantations.

Outcomes

Both short- and long-term complications, defined as health care use or death, were investigated. Fifteen mutually exclusive disease groups were defined based on ICD chapters (supplemental Table 1). Among patients who underwent HD-ASCT, short-term complications were defined as hospitalizations or deaths due to any cause (interpreted as transplant-related mortality) within 60 days of transplantation. Long-term complications were investigated among all patients and comparators and were defined as the first specialist outpatient visit, hospitalization, or death within any of the 15 disease groups that occurred 12 months or later after diagnosis. In addition, to illustrate the total health care burden, all specialist outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and bed days (ie, not only the first), starting from 1 year after diagnosis, were quantified.

Statistical methods

In the landmark analysis, patients were followed up from 12 months after diagnosis (or matching date) until death or 31 December 2017, whichever occurred first. Patients and comparators who died before the start of follow-up did not contribute to these analyses. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the number of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and bed days during follow-up were estimated using negative binomial regression models, both for the entire follow-up and in intervals (1-5 years, 5-10 years, and >10 years after diagnosis). Hazard ratios with 95% CIs of specific disease groups were estimated using the Cox regression models assuming proportional hazards (the assumption was formally evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals30).

To account for imbalance between the treatment groups, all models were adjusted for the matching variables (age and sex), year of diagnosis, CCI (0, 1, and 2+), and education level (≤9 years, 10-12, and >12 years of schooling). Age at diagnosis and calendar year of diagnosis were modeled as restricted cubic splines.

The cumulative incidence of lymphoma deaths was estimated in the presence of competing causes of death (other malignancy, cardiovascular disease, or remaining causes), stratified by treatment group (HD-ASCT and non-HD-ASCT). The unadjusted nonparametric estimates of the cumulative incidence were complemented by estimates of standardized cumulative incidence from a flexible parametric survival model adjusted for age, sex, calendar year, and CCI. We applied the standsurv package in Stata (Stata Statistical Software version 16.0, College Station, TX) to predict the cumulative incidence function under the assumption that the distribution of adjustment factors was the same for the 2 treatment groups.31

All analyses were based on complete cases and conducted using Stata.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Board of the Ethical Committee in Stockholm, Sweden (2007/1335-31/4, 2010/1624-32).

Results

Demographics

The study cohort comprised 620 patients with MCL and 6200 matched comparators from the general population. The median age at diagnosis or matching was 62 years (range, 22-69) and the median follow-up was 5.3 years (range, 1-17.7). Forty percent of all patients (n = 247) were treated with HD-ASCT within 12 months of diagnosis. These patients were generally younger, had a higher educational level, and a lower comorbidity burden as compared with patients treated without HD-ASCT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with MCL at age <70 years in Sweden between 2000 and 2014 (N = 620) by selection for treatment with HD-ASCT or not within 12 months of diagnosis and among general population comparators (N = 6200)

| Variable | Patients not treated with HD-ASCT<12 m∗ | Patients treated with HD-ASCT<12 m | P value | All patients, N (column %) <70 y | Comparators matched 1:10, birth year and sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, N | 373 | 247 | 620 (100)† | 6 200 (100) | |

| Median age (range), y | 65 (22-69) | 58 (32-69) | 62 (22-69) | 63 (22-70) | |

| Age categories at diagnosis or matching,‡n (%), y | |||||

| <60 | 91 (24.4) | 136 (55.1) | <.001 | 227 (36.6) | 2 140 (34.5) |

| 60-69 | 282 (75.6) | 111 (44.9) | 393 (63.4) | 4 060 (65.5) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 281 (75.3) | 192 (77.7) | .492 | 473 (76.3) | 4 730 (76.3) |

| Female | 92 (24.7) | 55 (22.3) | 147 (23.7) | 1 470 (23.7) | |

| Year of diagnosis or matching, n (%) | |||||

| 2000-2004 | 121 (32.4) | 51 (21.7) | .006 | 172 (27.7) | 1720 (27.7) |

| 2005-2009 | 104 (27.9) | 82 (33.2) | 186 (30) | 1860 (30) | |

| 2010-2014 | 148 (39.7) | 114 (46.2) | 262 (42.3) | 2620 (42.3) | |

| CCI, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 213 (57.1) | 190 (76.9) | <.001 | 403 (65.0) | 4 669 (75.3) |

| 1 | 50 (13.4) | 22 (8.9) | 72 (11.6) | 715 (11.5) | |

| 2+ | 110 (29.5) | 35 (14.2) | 145 (23.4) | 816 (13.2) | |

| Highest achieved education level | |||||

| ≤9 years of schooling, n (%) | 113 (31) | 39 (16.2) | <.001 | 152 (25.1) | 1 782 (29.6) |

| 10-12 years of schooling, n (%) | 155 (42.5) | 124 (51.5) | 279 (46.0) | 2 567 (42.7) | |

| >12 years of schooling, n (%) | 97 (26.6) | 78 (32.4) | 175 (28.9) | 1 669 (27.7) | |

| Missing, n | 8 | 6 | 14 | 182 |

P values (cases vs comparators): education, P = .061; Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), P = <.001.

Cutoff in landmark analysis is 12 months; patients with a HD-ASCT thereafter will remain unexposed in the analysis.

Fifty-five patients with MCL have a follow-up shorter than 12 months and do not contribute to the analysis.

Patients are matched on birth year, not exact age; therefore, the coherence is not perfect.

For the patients treated with HD-ASCT, the induction regimen was generally R-maxi-CHOP alternating with R-cytarabine given according to the Nordic MCL 2 protocol (Table 2). Consolidative high-dose chemotherapy with BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) or BEAC (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and cyclophosphamide) was used before transplantation. The patients treated without HD-ASCT were mostly treated with R-CHOP/cytarabine, R-CHOP, or R-bendamustine, whereas some patients were treated with chlorambucil alone (mainly before 2005 and none after 2010). A limited number of patients (n = 14 in the patient cohort) received rituximab maintenance.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and first-line treatment among patients diagnosed with MCL at age <70 years in Sweden between 2000 and 2014 (N = 620) by HD-ASCT or not within 12 months of diagnosis

| Variable | Patients not treated with HD-ASCT<12 m | Patients treated with HD-ASCT<12 m | P value | All patients, N (column %) <70 y |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, N | 373 | 247 | 620 (100) | |

| Stage | ||||

| Ann Arbor I, n (%) | 41 (11.2) | 4 (1.6) | <.001 | 45 (7.3) |

| Ann Arbor II, n (%) | 33 (9) | 17 (6.9) | 50 (8.2) | |

| Ann Arbor III, n (%) | 45 (12.3) | 36 (14.6) | 81 (13.2) | |

| Ann Arbor IV, n (%) | 248 (67.6) | 189 (76.8) | 437 (71.3) | |

| Missing, n | 6 | 1 | 7 | |

| MCL-specific international prognostic index | ||||

| Low risk (<5.7), n (%) | 80 (28.9) | 72 (36.7) | .126 | 152 (32.1) |

| Intermediate risk (5.7-6.1), n (%) | 102 (36.8) | 71 (36.2) | 173 (36.6) | |

| High risk (>6.1), n (%) | 95 (34.3) | 53 (27) | 148 (31.3) | |

| Missing, n | 96 | 51 | 147 | |

| Treatment | ||||

| NLG-MCL2 protocol, n (%)∗ | 50 (17.5) | 186 (94.4) | <.001 | 236 (48.9) |

| R-CHOP alternating with R-cytarabine or R-cytarabine single, n (%)† | 43 (15) | 8 (4.1) | 51 (10.6) | |

| R-CHOP, n (%) | 74 (25.9) | 3 (1.5) | 77 (15.9) | |

| Chlorambucil, n (%) | 27 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 27 (5.6) | |

| R-fludarabine or cyclophosphamide n (%)† | 6 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.2) | |

| R-bendamustine, n (%)† | 21 (7.3) | 0 (0) | 21 (4.4) | |

| Wait and watch, n (%) | 21 (7.3) | 0 (0) | 21 (4.4) | |

| Radiotherapy only, n (%) | 34 (11.9) | 0 (0) | 34 (7) | |

| Other treatment, n (%)‡ | 10 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.1) | |

| Missing, n | 87 | 50 | 137 |

Because of rounding, not all percentages add up to 100.

Nordic lymphoma group MCL2 protocol containing R-CHOP and high-dose cytarabine.

Number of patients with confirmed rituximab: 37 in the CHOP or cytarabine group, 42 in the CHOP group, 1 in the fludarabine or cyclophosphamide group, and 11 in the bendamustine group.

Either R-bendamustine alternating with R-cytarabine or unspecified chemotherapy; detailed frequencies not shown in subgroups owing to cell count <4.

Short-term complications (within 60 days) in patients treated with HD-ASCT

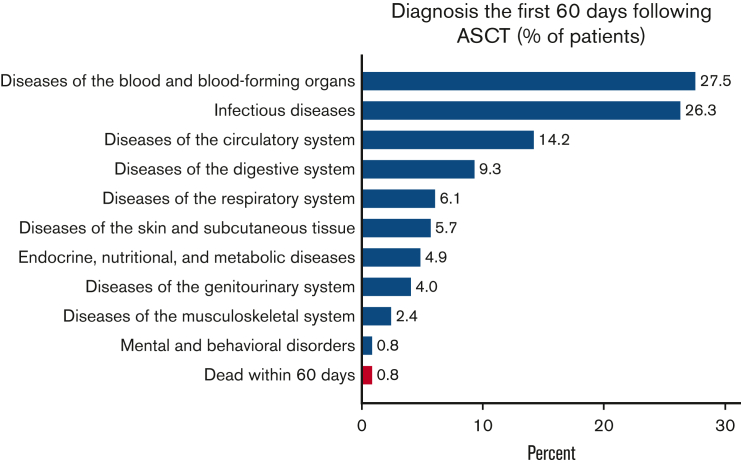

Recorded diagnoses (besides MCL) during these 60 days were mainly blood disorders, infectious diseases, and diseases of the circulatory or digestive system. Respiratory, skin, endocrine, and genitourinary problems were also frequent, whereas musculoskeletal and mental complications were rare (Figure 1). Patients spent a median of 22 days in hospital following the HD-ASCT (supplemental Figure 1). Two (0.8%) patients treated with HD-ASCT died within 60 days after their transplantation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients treated with HD-ASCT with an ICD-specific diagnosis at hospitalization or death within 60 days. Proportion of patients with MCL who were treated with HD-ASCT (within 12 months of diagnosis, n = 247) with an ICD chapter–specific diagnosis at hospitalization (blue) or death due to any cause (red), within the first 60 days of transplantation.

Long-term follow-up (ie, after 12 months)

Patients with MCL had a twofold increased incidence rate of outpatient visits during follow-up compared with the general population comparators (IRR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.8-2.2) (Table 3) and a sevenfold to eightfold increased rate of inpatient visits and number of bed days (hospital visits, IRR, 7.2; 95% CI, 6.3-8.3 and bed days, IRR, 8.3; 95% CI, 6.8-10.1). Patients treated with HD-ASCT had a slightly higher rate of outpatient visits during the first 5 years after diagnosis and lower rates of inpatient visits beyond 5 years after diagnosis compared with patients treated without HD-ASCT. The rate of bed days was similar in both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

IRR and 95% CIs of outpatient visits (excluding routine follow-up visits for lymphoma) and inpatient visits and bed days during follow-up (from 1 year after diagnosis)

| IRR; 95% CI∗ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1-5 y after diagnosis | 5-10 y after diagnosis | >10 y after diagnosis | |

| Outpatient visits | ||||

| Comparators | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| MCL | 2.0; 1.8-2.2 | 2.2; 2.0-2.5 | 2.1; 1.8-2.4 | 1.4; 1.1-1.8 |

| Comparators | 0.6; 0.5-0.6 | 0.5; 0.4-0.6 | 0.5; 0.4-0.6 | 0.6; 0.4-0.8 |

| non–HD-ASCT | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| HD-ASCT† | 1.2; 1.0-1.5 | 1.3; 1.0-1.6 | 1.1; 0.8-1.4 | 0.7; 0.5-1.1 |

| Inpatient visits | ||||

| Comparators | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| MCL | 7.2; 6.3-8.3 | 8.7; 7.3-10.3 | 4.6; 3.7-5.8 | 2.6; 1.8-3.7 |

| Comparators | 0.1; 0.1-0.2 | 0.1; 0.1-0.1 | 0.2; 0.1-0.2 | 0.3; 0.2-0.5 |

| non–HD-ASCT | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| HD-ASCT† | 1.0; 0.7-1.3 | 1.0; 0.7-1.4 | 0.6; 0.4-0.9 | 0.5; 0.2-0.9 |

| Bed days | ||||

| Comparators | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| MCL | 8.3; 6.8-10.1 | 10.0; 7.7-13.0 | 5.2; 3.7-7.3 | 4.1; 2.4-6.9 |

| Comparators | 0.1; 0.1-0.2 | 0.1; 0.1-0.1 | 0.2; 0.1-0.3 | 0.2; 0.1-0.4 |

| non–HD-ASCT | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| HD-ASCT† | 1.1; 0.7-1.6 | 1.1; 0.7-1.9 | 0.8; 0.4-1.5 | 0.7; 0.3-2.1 |

Adjusted for age, sex, calendar year, CCI, and education.

Treated with HD-ASCT within 12 months from diagnosis.

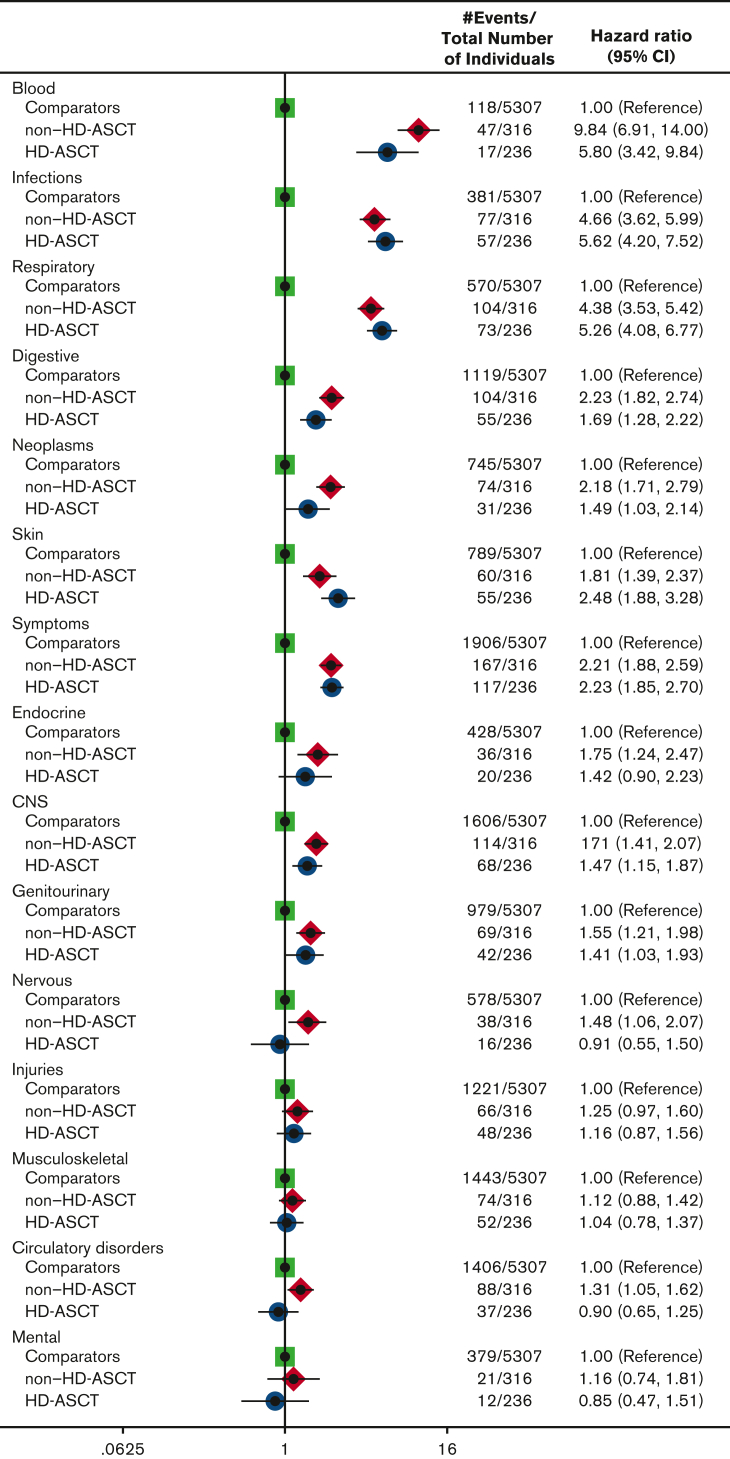

In relation to the matched comparators, patients with MCL had the most pronounced relative risks (Figure 2) and health care burden (supplemental Table 2) for diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs, infectious diseases, and diseases of the respiratory system. Similar rates were seen irrespective of treatment with or without HD-ASCT. The same pattern was observed in the sensitivity analysis with follow-up starting 9, 18, or 24 months after diagnosis. Among respiratory disorders, upper respiratory infections, influenza, and pneumonia were dominant (supplemental Figure 2A). Among infectious diseases, bacterial infections were most common, but patients treated with HD-ASCT were diagnosed with slightly more viral infections than those treated without HD-ASCT (supplemental Figure 2B). Diseases of blood and blood-forming organs were dominated by anemia, idiopathic thrombocyte platelet deficiency, immunodeficiency, and other diseases of blood-forming organs (supplemental Figure 2C). Frequencies of neoplasms other than MCL are presented in supplemental Figure 2D, the most frequent being melanoma and neoplasms of the skin, prostate cancer, and malignant neoplasm of the urinary tract. Patients treated with HD-ASCT were not diagnosed with more secondary malignancies than those treated without HD-ASCT (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 2D; Table 2). To illustrate when the different complications occurred during follow-up, the mean number of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and bed days for different disease chapters and time windows are shown in supplemental Figure 3. Patients treated with HD-ASCT did not have more outpatient visits or hospitalizations for neoplasm in the time span after 10 years of follow-up (supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of rates of different ICD-chapters between MCL patients (by HD-ASCT treatment) and comparators. Hazard ratios with 95% CIs of first ICD chapter–specific diagnosis (specialist outpatient visits or hospitalization) or death among patients with MCL (by HD-ASCT [blue circles] or non-HD-ASCT [red dimonds]) and comparators (green squares). All models were adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, calendar year, CCI, and educational level. CNS, central nervous system.

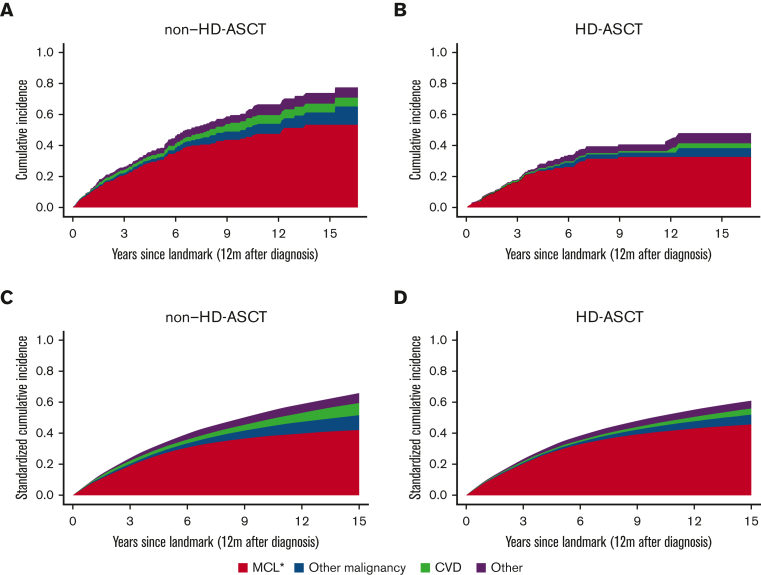

Causes of death

Deaths (≥12 months) due to causes other than MCL were rare in both patients treated with and without HD-ASCT (Figure 3). The 5-year cumulative probability of MCL-specific death in patients treated with HD-ASCT was 23% (95% CI, 18%-30%) and 32% (95% CI, 26%-38%) in patients treated without HD-ASCT. When eliminating potential differences in age, sex, CCI, and education level between the 2 treatment intensity groups (standardized analysis), there was no evidence of a difference in cumulative probabilities of MCL-specific death between the groups. As a reference, causes of death for the matched comparators can be found in supplemental Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Crude and standardized cumulative probabilities of death due to different causes by HD-ASCT. Cumulative probabilities of death portioned into MCL, other malignancies, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and other causes, within 12 months from diagnosis among patients with MCL, by without HD-ASCT (A,C) and with HD-ASCT (B,D). Crude estimates (A,B) and standardized estimates (C,D) over age, sex, CCI, and education level are shown. ∗Include ICD-10: C83-C91.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we found that patients with MCL overall, as expected, had a higher rate of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and bed days than general population comparators of the same age and sex. Also, most patients with MCL died from their lymphoma and not from a comorbidity or a treatment complication. Importantly, intensive first-line treatment with the Nordic MCL2 protocol including HD-ASCT was not associated with higher rates of the measured late effects compared with less-intensive treatment (non–HD-ASCT). In a previous study on the same cohort, selection for treatment with HD-ASCT was also associated with a better overall survival.29

Patients with MCL had particularly higher rates of blood disorders, infections, and diseases of the respiratory system than the comparators. Similar complications were reported in a previous study but in older patients with lymphoma who received transplantation.32 The category of blood disorders reflected visits that could be seen as associated with the underlying lymphoma, such as anemia, idiopathic thrombocyte platelet deficiency, eosinophilia, and immunosuppression. No codes for transformed lymphoma or myelodysplastic syndromes were seen. Infectious complications, known to be associated with both the lymphoma and given treatment,20 including viral as well as bacterial infections, were observed at higher rates after the end of first-line treatment (≥12 months of diagnosis) among patients compared with comparators. This could be regarded as a late effect of primary treatment or the lymphoma disease itself but not due to rituximab maintenance because very few patients in this cohort were treated with rituximab maintenance (n = 14). Regarding secondary neoplasms, a wide range of different neoplasms were seen, as indicated in the supplement, with a higher frequency among patients than in comparators. No difference in the rate of secondary neoplasms was observed between the patients treated with and without HD-ASCT. This indicates that the underlying disease and first-line chemotherapy could be a driver of secondary neoplasms, rather than consolidating HD-ASCT, at least in the absence of total body irradiation as induction (as in the Nordic protocol). However, as the observation period is still relatively short, we cannot rule out that a higher incidence of secondary neoplasms may appear with prolonged follow-up.

Observational comparisons of late effects among patients administered with different treatments can be challenging, as the groups are rarely comparable with regard to baseline characteristics. Patients selected for HD-ASCT treatment in this study were younger and had less comorbidity compared with patients in the non-HD-ASCT group, for which we tried to accommodate in the adjusted models. The long-term health care burden that we observed mainly reflected disorders related to the underlying MCL and potential relapses. In addition, MCL was the main underlying cause of death in the cohort. This is in line with data from a randomized study comparing health-related quality of life after different treatments, concluding that the underlying MCL caused most of the later complications.33 If this interpretation holds in the novel targeted treatment era remains to be seen. In a pooled analysis of 4 randomized controlled studies of the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib vs chemotherapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and patients with MCL, a favorable benefit-risk profile of ibrutinib treatment was shown compared with that of other standard treatments, despite prolonged ibrutinib therapy.34

A strength of this study is the generalizability of the population-based setting compared with selected cohorts in randomized trials, the long follow-up, and the detailed outcome analysis. The advantage of comparing late effects in patients vs comparators is the ability to disentangle excess health care use due to the disorder and its treatment from normal morbidity of an older population. Although the register-based setting allows for the study of an unselected group of patients, information on patients’ own reported adverse events was not captured, and we were not able to capture milder comorbidities or outcomes, typically treated in nonspecialized outpatient care,26 as this is not included in the National Patient Register. In addition, misclassification of exposure due to transplantations occurring after the landmark of 12 months could have biased the results, but in a sensitivity analysis using other landmarks (9, 18, and 24 months), the overall results were in line with those from the 12-month landmark approach, leading us to interpret this bias as minor.

In most clinical situations, the aim of MCL treatment is not to cure, but rather to prolong the patient’s life and maximize quality of life.19 Studies comprehensively evaluating both MCL-related symptoms and late adverse effects are thus crucial in the decision making of the care of patients with MCL. Although several review articles have discussed which patients with MCL should undergo transplantation, these have mostly focused on survival and patient eligibility for transplantation (based on comorbidity burden and tumor biological characteristics11,35,36) and not on adverse effects and future quality of life. As our results show, long-term monitoring of these patients is needed and there is room for potential preventive measures. Patients with MCL in Sweden are not routinely considered for infectious prophylaxis during follow-up, which could be considered. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survivors, a high rate of infections has also been seen and preventive measures such as infectious prophylaxis have been discussed.37

Conclusions

We have shown that patients with MCL, irrespective of treatment intensity with or without HD-ASCT, have higher hospitalization rates and particularly higher rates of respiratory disease, blood disorders, and infectious diseases, compared with matched comparators. Avoiding efficient MCL treatment because it is more demanding and possibly cause late effects may seem reasonable in the short term, but our results indicate that most of the long-term health care needs in patients aged up to 70 years are related to the lymphoma per se. This calls for continued efforts to improve treatment efficacy in MCL.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.J. received honoraria from Janssen, Gilead, Celgene, Roche, and Acerta and research support from Janssen, Roche, Celgene, AbbVie, and Gilead. K.E.S. received honoraria from Celgene and research support from Janssen. I.G. received honoraria from Janssen. All authors participate in a public-private real-world evidence collaboration between Karolinska Institutet and Janssen Pharmaceuticals NV.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society CAN 19 0123 Pj 01 H.

Authorship

Contribution: I.G., S.E., and C.E.W. designed the study and interpreted the study results; S.E. provided statistical analysis and figures; I.G. and S.E. drafted the manuscript; I.G., K.E.S., and M.J. performed the collection of data and verification of underlying data; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

The data underlying this study are available at the National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden, and Statistics Sweden for investigators with the appropriate approvals, but restrictions apply. However, data can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request for meta-analyses and with the appropriate approvals of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Castellino A, Wang Y, Larson MC, et al. Evolving frontline immunochemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma and the impact on survival outcomes. Blood Adv. 2022;6(4):1350–1360. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheah CY, Opat S, Trotman J, Marlton P. Front-line management of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Australia. Part 2: mantle cell lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma. Intern Med J. 2019;49(9):1070–1080. doi: 10.1111/imj.14268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahi PB, Tamari R, Devlin SM, et al. Favorable outcomes in elderly patients undergoing high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(12):2004–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dreyling M, Geisler C, Hermine O, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(suppl 3):iii83–iii92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerson JN, Handorf E, Villa D, et al. Survival outcomes of younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(6):471–480. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1250–1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munshi PN, Hamadani M, Kumar A, et al. ASTCT, CIBMTR, and EBMT clinical practice recommendations for transplant and cellular therapies in mantle cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56(12):2911–2921. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01288-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glimelius I, Smedby KE, Eloranta S, Jerkeman M, Weibull CE. Comorbidities and sex differences in causes of death among mantle cell lymphoma patients - A nationwide population-based cohort study. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(1):106–116. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Gouill S, Morschhauser F, Chiron D, et al. Ibrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax in relapsed and untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 trial. Blood. 2021;137(7):877–887. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Nordic MCL2 trial update: six-year follow-up after intensive immunochemotherapy for untreated mantle cell lymphoma followed by BEAM or BEAC + autologous stem-cell support: still very long survival but late relapses do occur. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyling M, Ferrero S. European Mantle Cell Lymphoma N. The role of targeted treatment in mantle cell lymphoma: is transplant dead or alive? Haematologica. 2016;101(2):104–114. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.119115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiappella A, Ladetto M. The role of autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(9):e617–e619. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112(7):2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangel J, Leitch HA, Connors JM, et al. Intensive chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation plus rituximab is superior to conventional chemotherapy for newly diagnosed advanced stage mantle-cell lymphoma: a matched pair analysis. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(2):283–290. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawalha Y, Hill BT, Rybicki LA, et al. Efficacy of standard dose R-CHOP alternating with R-HDAC followed by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation as initial therapy of mantle cell lymphoma, a single-institution experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(1):e95–e102. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam CS, Khouri IF. Autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation: rising therapeutic promise for mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(8):1239–1248. doi: 10.1080/10428190903026518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahamsson A, Albertsson-Lindblad A, Brown PN, et al. Real world data on primary treatment for mantle cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group observational study. Blood. 2014;124(8):1288–1295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-559930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoellner AK, Unterhalt M, Stilgenbauer S, et al. Long-term survival of patients with mantle cell lymphoma after autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in first remission: a post-hoc analysis of an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(9):e648–e657. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korycka-Wołowiec A, Wołowiec D, Robak T. The safety of available chemo-free treatments for mantle cell lymphoma. Expet Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(11):1377–1393. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1826435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goyal RK, Jain P, Nagar SP, et al. Real-world evidence on survival, adverse events, and health care burden in Medicare patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(6):1325–1334. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1919662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortelazzo S, Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJM, Dreyling M. Mantle cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;153 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahamsson A, Dahle N, Jerkeman M. Marked improvement of overall survival in mantle cell lymphoma: a population based study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(10):1929–1935. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.587560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111(2):558–565. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AE, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludvigsson JF, Appelros P, Askling J, et al. Adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index for register-based research in Sweden. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:21–41. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S282475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooke HL, Talback M, Hornblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):765–773. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11(1):450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glimelius I, Ekberg S, Linderoth J, et al. Sick leave and disability pension in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors by stage, treatment, and follow-up time--a population-based comparative study. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(4):599–609. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glimelius I, Smedby KE, Albertsson-Lindblad A, et al. Unmarried or less-educated patients with mantle cell lymphoma are less likely to undergo a transplant, leading to lower survival. Blood Adv. 2021;5(6):1638–1647. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert PC, Royston P. Flexible Parametric Survival Analysis Using Stata: Beyond the Cox Model. Stata Press. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahi PB, Lee J, Devlin SM, et al. Toxicities of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2021;5(12):2608–2618. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020004167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hess G, Rule S, Jurczak W, et al. Health-related quality of life data from a phase 3, international, randomized, open-label, multicenter study in patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib versus temsirolimus. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(12):2824–2832. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1326034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien S, Hillmen P, Coutre S, et al. Safety analysis of four randomized controlled studies of ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(10):648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.016. e615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerson JN, Barta SK. Mantle cell lymphoma: which patients should we transplant? Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019;14(4):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s11899-019-00520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenwell IB, Cohen JB. When to use stem cell transplant in mantle cell lymphoma. Expet Rev Hematol. 2019;12(4):207–210. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2019.1588106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyre TA, Wilson W, Kirkwood AA, et al. Infection-related morbidity and mortality among older patients with DLBCL treated with full- or attenuated-dose R-CHOP. Blood Adv. 2021;5(8):2229–2236. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.