Summary

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a complex multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia. AD is highly heritable, with heritability estimates of ∼70% from twin studies. Progressively larger genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have continued to expand our knowledge of AD/dementia genetic architecture. Until recently these efforts had identified 39 disease susceptibility loci in European ancestry populations.

Recent developments

Two new AD/dementia GWAS have dramatically expanded the sample sizes and the number of disease susceptibility loci. The first increased total sample size to 1,126,563—with an effective sample size of 332,376—by predominantly including new biobank and population-based dementia datasets. The second, expands on an earlier GWAS from the International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project (IGAP) by increasing the number of clinically-defined AD cases/controls in addition to incorporating biobank dementia datasets, resulting in a total sample size to 788,989 and an effective sample size of 382,472. Collectively both GWAS identified 90 independent variants across 75 AD/dementia susceptibility loci, including 42 novel loci. Pathway analyses indicate the susceptibility loci are enriched for genes involved in amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle formation, cholesterol metabolism, endocytosis/phagocytosis, and the innate immune system. Gene prioritization efforts for the novel loci identified 62 candidate causal genes. Many of the candidate genes from known and newly discovered loci play key roles in macrophages and highlight phagocytic clearance of cholesterol-rich brain tissue debris by microglia (efferocytosis) as a core pathogenetic hub and putative therapeutic target for AD.

Where next?

While GWAS in European ancestry populations have substantially enhanced our understanding of AD genetic architecture, heritability estimates from population based GWAS cohorts are markedly smaller than those from twin studies. While this missing heritability is likely due to a combination of factors, it highlights that our understanding of AD genetic architecture and genetic risk mechanisms remains incomplete. These knowledge gaps result from several underexplored areas in AD research. First, rare variants remain understudied due to methodological issues in identifying them and the cost of generating sufficiently powered whole exome/genome sequencing datasets. Second, sample sizes of non-European ancestry populations in AD GWAS remain small. Third, GWAS of AD neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid endophenotypes remains limited due to low compliance and high costs associated with measuring amyloid-β and tau levels and other disease-relevant biomarkers. Studies generating sequencing data, including diverse populations, and incorporating blood-based AD biomarkers are set to substantially improve our knowledge of AD genetic architecture.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Genome-wide association study, Review

Introduction

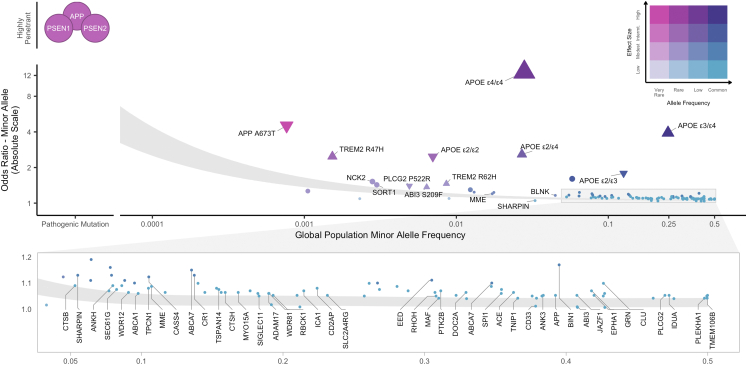

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the abnormal aggregation and deposition of amyloid-β peptides into extracellular plaques and of hyperphosphorylated tau into intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, followed by synaptic and neuronal loss resulting in progressive cognitive and functional decline.1 Genetic variants play a substantial role in the development of AD and can be conceptualized as occupying a space along two dimensions: population minor allele frequency (MAF) and effect size (Fig. 1). At one end of this spectrum, very rare highly penetrant mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 that cause autosomal dominant AD typically with early onset. At the other end of the spectrum, common alleles identified in genome-wide association studies (GWAS; Panel 1) of late-onset sporadic AD have individually small causal effects on disease susceptibility that in aggregrate contribute to genetic liability for disease.

Fig. 1.

Genetic architecture of AD/dementia highlighting ADAD mutations and 81 genome-wide significant loci. Genetic variants associated with disease are often conceptualized along two dimensions–variant effect size and population minor allele frequency. Highly penetrant mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 that segregate with autosomal dominant AD are extremely rare and have large effect sizes. Variants discovered by genome-wide associations are mostly common to low-frequency with small effect sizes. To date, AD/dementia GWAS have identified 101 independent AD-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms across 81 genome-wide significant (p < 5e-8) loci. The shaded area illustrates 80% power to detect genome-wide significant association for variants at a given effect size and population frequency between an effective sample size of 382,472 from Bellenguez et al. (2022) (top) and 1 million (bottom), assuming 0.18 AD prevalence. Odds ratios are reported on the absolute scale, with triangles indicating directionality for APOE genotypes and rare variants with moderate-high SnpEff impact annotations. Effect sizes for APOE genotypes and APP Ala673Thr were obtained from Reiman et al.1 and Jonsson et al.,16 respectively. Labeled loci indicate candidate causal genes prioritized by Bellenguez et al. (2022). Variant MAFs and APOE genotype frequencies were obtained from the gnomAD global population (GRCh37 v2.1.1).

Panel 1. Glossary terms.

Candidate Causal Gene: Genome-wide association analyses identify regions of the genome associated with disease, with genes within a locus selected for further study and validation based on their biological plausibility and statistical significance.

Effective Sample Size: In contrast to total sample size—the total number of participants in a study—the effective sample size reflects the sample size for an equivalently powered GWAS within a balanced sample design (i.e., 50% cases and 50% controls).22

Genome-wide association study: Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) aim to identify genetic variants that are associated with phenotypes by testing for differences in allele frequencies between people who differ phenotypically.28 Each genotyped or imputed variant across the whole genome is tested sequentially–typically within a regression framework–and variants reaching genome-wide significance (p < 5e-8) are determined to be significantly associated with a given phenotype. GWAS interrogating common/low-frequency variants detect association between the phenotype and haplotype blocks of variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD) rather than genes per se, motivating downstream prioritization analyses to uncover the genes implicated as causally driving the phenotype.

Genetic Architecture: The characteristics of genetic variation that are responsible for the heritable component of a trait. This comprises the number of variants affecting a trait, their effect sizes, their frequency in the population, and gene–gene and gene–environment interactions. Common (minor allele frequency [MAF] > 5%) and low-frequency (MAF between 1% and 5%) variants typically have small effect sizes, while rare variants (MAF between 0.1% and 1%) and ultra-rare variants (MAF < 0.1%) tend to have large effect sizes.

Heritability: The proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genetic variation. Approaches that estimate heritability typically capture either broad-sense heritability (H2), the fraction of trait variation that can be attributed to both additive or dominance effects, or narrow-sense heritability (h2), which captures additive genetic effects only. SNP-heritability () only captures the additive effects of measured variants and is dependent on the exact set of variants used to estimate it.28,56

Linkage disequilibrium: Correlation structures between nearby genetic variants largely due to genetic recombination during gametogenesis. Differences in LD structure across populations are a major contributor to ancestry differences in trait genetic architecture.

Polygenic Risk Score: Polygenic risk scores (PRS) provide an estimate of genetic propensity to a trait at an individual level, typically by weighting and summing genotypes at multiple risk-associated variants by their effect sizes, sometimes including other weighting factors or filters.45

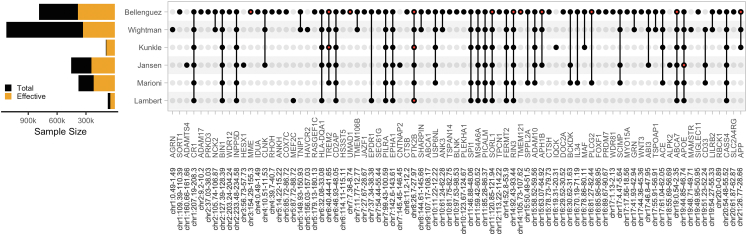

In our previous review, we provided an overview of GWAS methodology, the loci discovered by the largest AD/dementia GWAS at the time, and gene prioritization efforts to nominate candidate causal gene(s) at each locus.2 Since then, improvements in sample size resulted in the discovery of several novel loci,3,4 culminating in the publication of two new AD/dementia GWAS with significantly larger sample sizes that have doubled the number of AD-associated loci (Fig. 2).5,6 At the same time, causal gene prioritization approaches have also advanced considerably. In this Rapid Review, we will summarize the loci and respective candidate causal genes associated with AD, the biological pathways they implicate, and AD heritability estimates based on these genetic associations. Finally, we will discuss existing gaps in our understanding of the genetic architecture and biological mechanisms of AD and ongoing efforts to close those gaps.

Fig. 2.

AD/dementia genome-wide significant loci. AD/dementia GWAS have found an increasing number of associated loci as effective sample size has increased, collectively identifying 101 independent variants across 81 loci. Full points represent loci that reach genome-wide significance in a given study, and red points represent loci harboring multiple independent associated variants. Loci are labeled based on candidate causal genes prioritized by Bellenguez et al. (2022) and Wightman et al. (2022).

Genetic loci associated with Alzheimer's disease

Building on their earlier study, Wightman et al. expanded the sample size of their GWAS to 1,126,563 participants (43,725 cases, 46,613 proxy-cases, 1,036,225 controls/proxy-controls) primarily by including new biobank and population-based dementia datasets.6,7 Bellenguez et al. expanded on earlier GWAS from the International Genomics of Alzheimer's Projects8 by including new clinical case/control cohorts predominantly from the European Alzheimer's & Dementia BioBank (EADB) in addition to biobank dementia datasets resulting in a total sample size of 788,989 participants (64,498 cases, 46,828 proxy-cases, and 677,643 controls/proxy-controls).5 Both studies were limited to European ancestry individuals. Additionally, there is a large degree of sample overlap between these two studies and with earlier studies, and as such they are not independent. While Wightman et al. obtained a larger total sample size by predominantly increasing the number of population-based controls; Bellenguez et al. obtained a larger effective sample size by increasing the number of clinical cases, thus achieving greater statistical power to detect genetic variants associated with AD/dementia (Fig. 2). Furthermore, when Wightman et al. and Bellenguez et al. limited their GWAS and pathway enrichment analyses to clinically-diagnosed cases their findings remained consistent, indicating their primary results were not driven by the inclusion of proxy-cases from the UK Biobank (UKB).

Together, Wightman et al. and Bellenguez et al. identified 90 independent variants across 75 loci (38 and 71 respectively) associated with AD/dementia, of which 34 loci were identified by both studies and 42 loci are novel (collapsing loci across studies results in fewer reported loci from Bellenguez et al. (2022); see Panel 2 for methods on data harmonization and loci definition). Post-GWAS analyses were subsequently performed to identify candidate causal genes and the biological pathways that are perturbed by AD/dementia-associated variants.

Panel 2. Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched PubMed for genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer's disease published between Jan 1, 2020, and July 31, 2022, using the terms: ((Alzheimer Disease [MeSH Terms]) AND association study, genome wide [MeSH Terms]) AND (“2020/01/01” [Date–Publication]: “2022/07/31” [Date–Publication]) AND English [LA] NOT review [pt]. We included studies in which the outcome was clinically diagnosed late onset Alzheimer's disease or a family history of Alzheimer's disease. For Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2, the lead variants, effect sizes, variance, allele frequency, and sample size were extracted from GWAS of AD/dementia conducted in populations of European ancestry and processed as follows. Variant effect alleles were lifted over to build GRCh37, harmonized so the effect allele aligned with the reference human genome (build 37) alternate allele, then annotated with global population allele frequency from gnomAD, predicted impact using snpEff, nearest protein-coding gene according to GENCODE release 40, and cytogenetic band from UCSC Genome Browser. Loci were defined by merging overlapping regions ±500 kb around each lead variant from each study to obtain non-overlapping regions. Collapsing loci across studies resulted in fewer reported loci in Bellenguez et al. LD pruning (EUR GRCh37 reference, r2 = 0.1, MAF = 0.001) using LDlink SNPclip was employed to define independent variants in each locus. Code is available at https://github.com/sjfandrews/ADGenetics. The final reference list was generated on the basis of relevance and novelty to this Rapid Review.

Alzheimer's disease gene prioritization

While GWAS have advanced our understanding of the genetic architecture of AD, post-GWAS functional genomic analyses are required to prioritize genes that modulate disease susceptibility and nominate candidate causal genes for further functional validation in cellular and animal models. Integration of earlier AD GWAS with tissue and cell type-specific epigenetic annotations strongly implicated myeloid cells (including microglia, the brain-resident macrophages) in the modulation of disease susceptibility.9,10 In addition, mapping AD risk variants in active myeloid enhancers to their target genes led to nomination of candidate causal genes in myeloid cells (including BIN1, RIN3, ZYX, CD2AP, SORT1, CASS4, CCD6, TSPAN14, NCK2).3,9 These findings also help to predict the directionality of AD risk gene expression on disease susceptibility, which can help interpret the results of gene manipulations (knockout/knockdown or overexpression) in validation experiments and guide the development of therapeutics targeting these AD risk genes. For example, increased AD risk was associated with decreased expression of BIN1, ZYX, and APPB3, but increased expression of RABEP1 and AP4M1.9 Gene regulatory network analyses have also confirmed that AD risk variants specifically affect binding of the transcription factor SPI1 (PU.1), a master regulator of myeloid cell lineage, at gene regulatory elements (enhancers or promoters) of microglial cells.10

Gene prioritization analyses conducted by Wightman et al. and Bellenguez et al. identified a further 62 unique candidate causal genes. Using colocalization to integrate expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) from brain and immune tissues/cells with their GWAS signals, Wightman et al. nominated nine candidate causal genes across the 38 loci they identified. Bellenguez et al. conducted a more systematic search for candidate causal genes across the 40 novel loci they discovered. They investigated whether the lead variant in each locus was a rare or protein-altering variant near a protein-coding gene, regulated molecular phenotypes (expression, splicing, protein expression, DNA methylation, or histone acetylation) in AD-relevant brain tissue/cell types or blood, or affected APP metabolism. By integrating these various levels of evidence into a gene prioritization score, 55 candidate causal genes were identified–31 with tier 1 evidence (greater likelihood of being a causal risk gene) and 24 with tier 2 evidence (lower likelihood of being a causal risk gene and the absence of a minimum level of evidence as a causal risk gene). This encompassed 25 loci with a single tier 1 gene, 6 loci with a single tier 1 gene and one or more tier 2 genes, and 9 loci with one or more tier 2 genes. Of the 40 loci investigated, 13 contained myeloid candidate causal genes.

Overall, gene prioritization efforts indicate ∼51% of AD loci harbor candidate causal genes involved in myeloid cell function, further implicating myeloid cells in the etiology of AD.

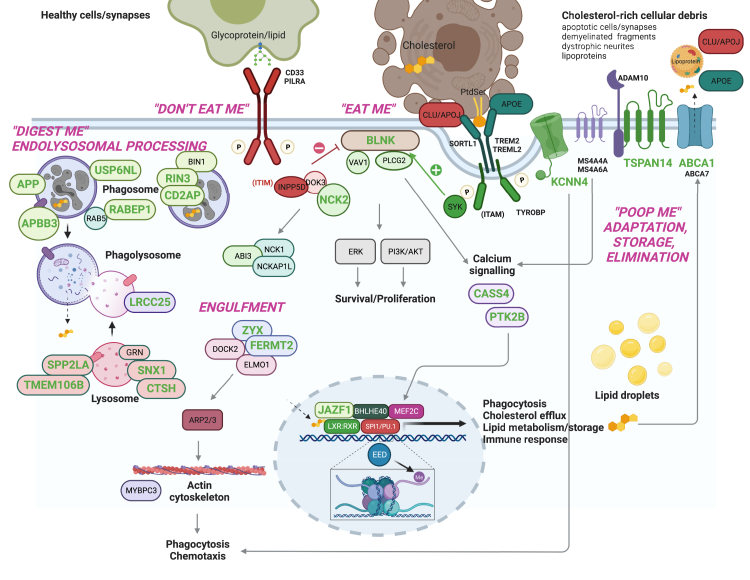

Human genetics implicates microglial efferocytosis and APP metabolism as strong candidate causal Alzheimer's disease pathways

The next unresolved question concerns the biological processes in myeloid cells/microglia that AD risk variants affect to modulate disease susceptibility. Since the early AD GWAS, pathway analyses of common AD risk variants consistently showed enrichment for gene sets involved in 1) cholesterol metabolism and transport, 2) endocytosis/phagocytosis, and 3) innate immune system; with most of the recently nominated AD risk genes falling into these biological pathways.3,9 For example, USP6NL, nominated as a candidate AD risk gene in the ECHDC3 locus by integration of microglial eQTL data, is involved in endolysosomal membrane trafficking.11 In addition, rare AD risk variants have been discovered in myeloid-specific genes (i.e., TREM2, ABCA7, PLCG2, ABI3) with critical roles in efferocytosis–the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells and other cholesterol-rich cellular debris (e.g., myelin fragments and apoptotic synapses) by microglia and other myeloid cells of the innate immune system.12 These findings strongly suggest that the three etiological pathways emerging from GWAS are not independent causal drivers of AD. Rather, they are facets of a higher-order biological process (efferocytosis) that connects them as (dys)functional components of a pathogenetic hub within myeloid phagocytes (Fig. 3). KCNN4, identified by integrative fine mapping analysis is involved in microglial migration, which is critical for engagement of efferocytic targets by microglia.10 Bellenguez et al. nominated additional genes that support the causal role of microglial efferocytosis in AD. Gene Ontology annotation of prioritized genes (e.g., TMEM106B, SNX1, and CTSH), showed enrichment in endolysosomal function. Furthermore, BLNK has been shown to operate in the TREM2-PLCG2 signaling cascade that is critical for efferocytosis.14 Other prioritized genes (ABCA1, ATP8B3, JAZF1) are involved in lipid/cholesterol metabolism, another important component of efferocytosis.12 Consistent with this functional interpretation of AD GWAS findings, a recent study reported opposing effects of APOE2 and APOE4 on microglial efferocytosis and lipid metabolism.15

Fig. 3.

Prioritized AD risk genes with roles in microglial efferocytosis. Both common and rare genetic variants associated with Alzheimer's disease point to several genes with important roles in one of the most fundamental functions of all macrophages, the phagocytic clearance of dead cells and other cellular “waste” (a process termed “efferocytosis”). Efferocytosis is essential for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and immune tolerance, and for the resolution of inflammation. Accordingly, defective efferocytosis underlies several autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases, and it is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of several other disorders.13 Efferocytosis is a multi-step process that involves: 1) finding dead cells by virtue of receptors located on the surface of macrophages that recognize “eat-me” (e.g., phosphatidylserine, PtdSer) as well as “don't eat-me” (e.g., sialylated glycoproteins/lipids) signals presented on the surface of dead and live cells, respectively; 2) internalization of dead cells by phagocytic uptake into phagosomes (Engulfment), 3) digestion of dead cells by the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes (“Digest me”. Endolysosomal processing); 4) functional (e.g., transcriptional, metabolic, and inflammatory) adaptation of macrophages to molecules derived from the phagolysosomal decomposition of cell corpses, e.g., cholesterol, which activates LXR:RXR nuclear receptors to regulate the expression of genes (e.g., AD-associated genes ABCA1 and APOE) involved in the removal of cholesterol from macrophages (“Poop me”. Adaptation, storage, elimination). With the exception of genes colored in gray, all genes shown in this figure to be involved in the various steps of efferocytosis have also been implicated in the etiology of AD by GWAS and post-GWAS studies. Genes in green font were prioritized or nominated through integration analyses.3,5,9, 10, 11 Thus human genetics evidence strongly suggests that efferocytosis may act as a pathogenetic hub for Alzheimer's disease in macrophages, including microglia in the brain. Created with BioRender.com.

More recently (and possibly due in part to AD GWAS geneset annotation bias in favor of the amyloid cascade hypothesis) pathway analyses of common AD risk alleles have also implicated amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle formation in the etiology of late-onset AD.5,6 This is consistent with the rare protective missense APP A673T variant previously found in the Icelandic population.16 It will be important to determine whether APP processing plays a role in efferocytosis or whether these pathways represent separate disease mechanisms underlying AD pathogenesis.

Although, ∼51% of AD GWAS loci contain myeloid candidate causal genes and pathway analyses of these genes point to the critical role of microglial efferocytosis, AD risk variants in the remaining loci may affect expression of genes in other cell types that impact microglial efferocytosis in a non-cell autonomous fashion, or other biological processes altogether. For example, a loss-of-function nonsense mutation in IL34 may increase AD risk via neuron-driven loss of microglia, highlighting the role of cell–cell communication.5,17 In addition, recent studies found that APOE4 altered cholesterol homeostasis and transport in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, in addition to microglia. APOE4-mediated cholesterol accumulation in iPSC-derived astrocytes impaired function of lysosomes and changed their profile of secreted cytokines while abnormal accumulation of cholesterol in oligodendrocytes from APOE4 carriers was associated with weaker myelination.18,19

In summary, the integration of AD GWAS with multi-omic datasets has yielded crucial insights into candidate causal genes and the molecular and cellular pathways that may mediate their effect on disease susceptibility. However, AD functional genomic studies are still limited by insufficient multi-omic datasets in disease-relevant tissues and cell types. As such, this remains a critical bottleneck in elucidating the genetic, molecular, and cellular mechanisms that drive AD risk.

Heritability of Alzheimer's disease

Given GWAS have collectively identified 101 independent variants across 81 loci associated with AD/dementia in European ancestry populations (Fig. 2), how many more novel loci remain to be discovered?56 Heritability estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance in a trait that can be explained by genetic variation–including additive and non-additive effects.20 Twin studies estimate that the narrow-sense heritability (the fraction of phenotypic variance due to additive genetic effects) of AD is ∼70%.21 In contrast, Wightman et al. used their GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics to estimate the SNP-heritability (the proportion of narrow-sense heritability explained by genotyped/imputed variants) of AD as 3.1%. The gap in heritability estimates between twin studies and GWAS–termed “missing heritability”–can be attributed to several factors.

First, narrow-sense heritability captures the additive genetic effect of all variants, encompassing the complete range of frequencies and types (e.g., SNPs, structural variation, etc), while SNP-heritability is dependent on the exact set of variants used to estimate it, typically limited to common and low-frequency variation interrogated in GWAS.20 Second, widely-used methods for estimating SNP-heritability from GWAS summary statistics exclude genetic variants with extremely large effect sizes and correspondingly the highest heritability–such as APOE4–as outliers. Third, mismatches in the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure between GWAS cohorts used to estimate SNP-heritability and population reference panels will decrease heritability estimates. SNP-heritability can be further affected by residual uncorrected population structure, environmental biases, indirect genetic effects (e.g., parental effects, assortative mating, sibling effects), assuming a homogeneous contribution to trait heritability across all SNPs, and variation in the proportion of cases across contributing cohorts.20,22 Heritability is also specific to how a trait is measured, with poor diagnostic accuracy of AD leading to measurement error and thus making AD appear less heritable; this can be further exacerbated by meta-analysis of clinical- and proxy-defined cases.23,24 Finally, it is important to note that heritability estimates are not static and are dependent on the time, place, and population in which they are estimated, due to the population specificity of additive & non-additive genetic factors and environmental variables.20 As such, if the environmental component of a trait decreases, the corresponding genetic component–and thus heritability–will increase.

The missing heritability in AD GWAS is therefore due to both GWAS only capturing a fraction of the heritability in twin studies and a downward bias in SNP-heritability estimates. By incorporating genetic information from GWAS into twin study heritability estimates, APOE and AD polygenic risk scores (PRS) only account for 9.3% and 2.1% of phenotypic variance, respectively.21 This indicates that ∼59% of AD heritability remains unexplained with potentially ∼11,000 causal variants underlying genetic risk for AD.21,25 Power analyses indicate that a sample size of >8 million is required to identify 80% of the genetic variance of AD. While likely inflated due to the downward bias in AD heritability estimates, this suggests that we have not yet reached a point of diminishing returns.25,26 Nevertheless, while increasing the overall effective sample size will identify novel AD loci, alternative study designs will be required to further dissect the genetic architecture of AD.

Rare variants contributing to Alzheimer's disease risk

Rare variation is one widely discussed potential source of missing heritability in complex traits.27 Variants that have strong effects on complex traits are expected to be under intense selective pressure and therefore remain at low frequencies in the population. GWAS have traditionally relied on array-based SNP genotyping followed by statistical imputation, which is typically limited to common and low-frequency variants and thus has generally been unable to detect rare variants.20,28,29 Second-generation sequencing in the form of short read whole genome or exome sequencing (WGS or WES) are the primary genotyping technologies for robustly detecting rare and ultra-rare genetic variants.20,28,29 The main challenge associated with using WGS/WES to identify rare variation remains the cost of generating sufficiently powered datasets.

GWAS based on genotyping with WGS/WES or exome-wide arrays have successfully identified AD-associated rare variants in a number of genes that converge on the same biological pathways identified by GWAS of common/low-frequency variation.29 Several of the earliest discoveries include rare protein-altering variants in genes with important roles in microglial efferocytosis in AD, notably TREM2, ABCA7, PLCG2, and ABI3.29 Improved reference panels for imputation enabled the GWAS by Bellenguez et al. to detect association with these original TREM2, PLCG2, and ABI3 rare variants in addition to novel common variants at several of those loci.5 The next logical step will be to implement GWAS designs that combine WGS/WES with SNP array datasets to identify novel variant associations.

This approach was used to identify AD-associated APOE rare variants by initially using a WGS/WES discovery cohort from the Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP; 11,868 cases and 11,934 controls), followed by replication using both densely imputed array data from clinical cases/controls (44,161 cases and 159,002 controls) and WES data from proxy cases and population controls (28,484 cases and 157,436 controls).30 Two rare protective missense variants were identified—the previously reported APOE3-Jacksonville (V236E) variant that apparently promotes healthy brain aging by reducing APOE self-association and increasing lipidation,31 and the novel R251G variant where the mechanism underlying the reported protective effect remains to be elucidated.

GWAS approaches integrating WES/WGS and SNP array data will further identify variants and genes associated with AD, hence elucidating the biological pathways that modulate disease risk when perturbed. Moreover, rare variation AD GWAS has focused on protein-altering variants, but the impact of rare non-coding variation in gene regulatory elements is largely unexplored. Third-generation WGS using long read technology will also enable researchers to robustly investigate the role of other types of genetic variation, such as structural variants.32

Alzheimer's disease genetics in diverse populations

A major limitation of genetic studies is insufficient racial and ethnic diversity, with individuals of European ancestry overwhelmingly overrepresented.33 This is also reflected in AD genetic studies despite African Americans (AAs) and Hispanic Americans being more likely to develop AD than non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs) from the same community. Asian Americans, on the other hand, have a similar prevalence of AD to NHWs. The genetic architecture of complex traits like AD can also differ between populations, due in part to inter-population differences in LD structure. As such, results from one population may not extrapolate well to another, exacerbating health disparities in non-European ancestry populations who may not fully benefit from the genetic and genomic advances in the knowledge and treatment of AD/dementia derived from studies limited to NHWs.33,34

Expanding AD GWAS to enhance representation of multiple populations will confer several advantages. First, genetic variants that are rare or non-existent in one population may be more frequent in another population, enabling the discovery of ancestry-specific or ancestry-enriched risk variants. Additionally, gene by population-specific environmental factor interactions may result in ancestry-specific genetic effects that highlight novel pathways.34 Second, cross-population genetic studies performing fine mapping of genomic loci to identify causal variants will generally benefit from inter-population LD structure differences and identify smaller sets of candidate causal variants.20

The largest GWAS of clinical AD in AAs comprised 2784 cases and 5222 controls.35 In a single variant analysis adjusting for age, sex, and population structure only the APOE locus achieved genome-wide significance, however, another nine loci reached suggestive significance. In secondary models adjusting for APOE, a novel rare variant reached genome-wide significance in addition to a further 3 loci at suggestive significance. Of the 14 loci identified only two were previously identified in European ancestry AD GWAS (APOE and ABCA7). Pathway-based analysis however highlighted that genes within these loci are involved in the same principal molecular pathways as detected by European ancestry GWAS, including innate immunity, lipid processing, and intracellular trafficking, underscoring their importance in disease etiology, and highlighted kidney system development as a novel pathway. A second study expanded on this analysis by meta-analyzing these results with a GWAS of ADRD and proxy dementia (4012 cases; 6641 proxy cases; and 64,405 controls/proxy-controls) in AA participants from the Million Veterans Program that subsequently identified six genome-wide significant loci.36

A similarly sized Japanese population AD GWAS (3962 cases and 4074 controls) identified nine suggestive loci, three of which reached genome-wide significance after meta-analysis with a replication cohort (5178 cases and 6520 controls).37 The known AD-associated loci APOE and SORL1 were confirmed, while a novel locus not identified in European ancestry populations was discovered. The lead SNP in the novel locus is more frequent in East Asian compared to European ancestry populations and was observed to be an eQTL for the genes FAM47E and SCARB2 in brain tissue–with both genes also exhibiting association with Parkinson's disease. Pathway analysis replicated the amyloid pathways and identified novel pathways associated with the regulation of metallopeptidase and metalloendopeptidase activities.

In summary, diversifying participants in AD genetics studies will improve the effectiveness of genomic medicine by expanding the scope of known genetic variation, facilitating locus discovery, improving functional mapping, and ultimately bolstering our understanding of disease etiology and reducing health disparities. In addition, novel diverse population functional genomics datasets are urgently needed for integration with large diverse population AD GWAS to improve population-relevant gene prioritization and promote AD precision medicine equity. Finally, moving beyond discrete continental ancestries by using concepts and tools that adopt a multidimensional and continuous view of ancestry to examine how local ancestry moderates AD-associated genetic variation (in both admixed and “homogenous” populations) will further facilitate locus discovery and functional mapping.38,39

Using plasma biomarkers to elucidate Alzheimer's disease genetics

An alternative approach to investigate the genetic basis of AD is to study the effects of genetic variation on AD pathophysiological quantitative traits. Examining more objective measurable biomarkers of AD (endophenotypes) rather than clinical diagnostic classifications has the advantage of reducing trait heterogeneity and improving statistical power to detect an effect, assuming measurement error is low. Furthermore, this approach enables identification of genetic variants that are associated with specific AD-related biological mechanisms. GWAS of neuropathological, neuroimaging, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid and tau levels have to date been constrained by their sample size due to difficulties collecting biological specimens resulting from low compliance (CSF, autopsy) or high costs (positron emission tomography, PET). Despite these limitations, GWAS of CSF Aβ42, CSF pTau, and brain amyloid burden using PET imaging have identified several genome-wide significant loci.40,41 These studies have laid the groundwork for the advent of large blood-based AD biomarker datasets that will significantly improve our ability to identify genetic variants associated with AD pathogenesis.

GWAS of amyloid and tau plasma biomarkers are still in their infancy, however, they have identified key loci and genes associated with Aβ and tau processing. In 12,369 participants of European ancestry, a GWAS of plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/40 ratio levels identified two loci, APOE and BACE1.42 Gene-based analyses further identified APOE, BACE1, PSEN2, and APP, emphasizing that variants in genes known to regulate APP processing determine plasma Aβ levels. A multi-population GWAS of circulating total tau levels in 15,674 people (14,721 NHWs and 953 AAs) identified three genome-wide significant loci specific to AAs and a single locus encompassing MAPT, which encodes tau, in NHWs.43

In addition to promoting the identification of novel genetic variants associated with AD pathophysiology, plasma biomarkers will facilitate improved AD diagnostic accuracy and decrease disease status measurement error in AD GWAS.44

Utility of Alzheimer's disease polygenic risk scores in clinical practice

As well as discovering risk loci to inform drug development, GWAS can be used to develop polygenic risk scores (PRS) that quantify individual-level genetic risk for disease to facilitate disease prediction enabling the early identification of at-risk individuals.45 Bellenguez et al. generated an AD-PRS composed of 82 genome-wide significant SNPs, excluding the APOE region, and evaluated its association with incident AD in European descent cognitively unimpaired participants and patients with MCI. Higher AD-PRS were associated with increased risk of conversion to AD in both groups, especially for participants in the highest decile for genetic risk. However, the predictive ability of the AD-PRS was limited, only marginally increasing the ability to discriminate cases from controls, beyond that of age, sex, and APOE. The predictive performance of AD-PRS are also affected by the p-value threshold for including variants and how the APOE locus is included in the model–with the most predictive models including APOE and PRS composed of all variants with p < 0.1 as two separate predictors.46 Nevertheless, AD-PRS have shown better discriminative ability in pathologically confirmed cases/controls, suggesting that GWAS with more refined AD and control phenotypes may yield better predictions.23,47 PRS generated from European ancestry GWAS also have poor transferability to other populations,48 which combined with the lack of diverse AD GWAS datasets, further limits the clinical utility of AD-PRS.

Taken together, the poor discriminative ability of AD-PRS and their lack of transferability across populations limit the current use of AD-PRS to research purposes only. However, this area of research is undergoing rapid methodological development. PRS for genetic prediction of AD may further be enhanced by generating pathway or etiology-specific PRS,49 using multi-trait PRS for cross-trait prediction,50 incorporating functional annotations,51 combining common and rare variation,52 and including GWAS of ancestrally diverse populations.53

Balancing sample size and depth of phenotyping

Larger effective sample sizes are required for AD GWAS to discover novel loci due to its high polygenicity. The inclusion of participants with minimal phenotyping–often self-reported dementia diagnoses, family history, or EHR diagnostic codes–from large-scale biobanks and population cohort studies has allowed sample sizes to increase rapidly. However, these minimal phenotypes can have poor diagnostic accuracy and therefore capture genetic effects of other dementias rather than AD specifically. To identify genetic signatures specific to AD, more refined phenotyping of case-controls based on neuropathological or biomarker criteria is needed to improve AD diagnostic accuracy. Deeper phenotyping also enables more in-depth analyses of related phenotypes, such as resilience to AD neuropathology, that can highlight novel biological pathways protecting the brain from amyloidosis.54,55 However, to date such studies of more refined phenotypes remain underpowered due to small sample sizes.

Whether large-scale studies composed of broad clinical phenotypes or more refined phenotyping should be prioritized depends on the specific research question, however, both are essential to maximize clinical translation of AD genetics. Triangulation across study designs will increase the confidence in AD-associated genetic loci and facilitate the identification of genes that specifically influence the clinical and proteinopathic features characterizing AD pathogenesis.

Conclusion

AD GWAS across multiple populations have to date identified more than 80 loci, with the majority found in European ancestry cohorts primarily due to markedly larger sample sizes. These discoveries have substantially contributed to our understanding of the genetic basis of AD and revealed the roles of microglial efferocytosis and APP metabolism in AD pathogenesis. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion of AD genetic architecture remains to be discovered. Generating large scale WES/WGS datasets will enable the identification of rare variants associated with AD. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in AD GWAS will improve the generalizability of genetic findings and polygenic risk scores across populations, promote elucidation of genetic risk mechanisms, and facilitate the discovery of ancestry-specific genetic effects. Collection of blood-based biomarkers will enhance diagnostic accuracy, and GWAS of blood-based biomarkers will drive discovery of genetic variants influencing specific AD-related biological mechanisms. While we have focused on examining the contribution of genetics to AD, environmental and lifestyle risk factors are estimated to explain 29% of the phenotypic variance,21 however, their impact in the context of AD genetic liability remains largely unknown. Large diverse integrative studies combining genetics, multi-omics, lifestyle risk factors, and social determinants of health will be crucial for AD pathobiological insight and equitable therapeutic discovery.

Contributions

SJA, AER, BFH, APD, EM, and AMG defined the concept and scope of the Rapid Review. SJA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SJA, AER, BFH, APD, EM, and AMG revised the manuscript drafts and agreed on the final manuscript for submission. SJA and BFH developed the computational workflow for extracting, standardizing, harmonizing, and annotating the data collected from the reviewed manuscripts. SJA led the development of Fig. 1, Fig. 2. EM and APD led the development of Fig. 3.

Declaration of interests

SJA is supported by NIH-NIA K99AG070109A. BFH is supported by the JPB Foundation. AER is supported by NIH-NIA U01AG058635. APD is supported by the BrightFocus Foundation (A2021014F) and the JPB Foundation. EM is supported by the BrightFocus Foundation (A2017458S) and the Neurodegeneration Consortium. AMG is supported by National Institutes of Health (U01AG058635; U01AG032984; P30AG066514), JPB Foundation, the Neurodegeneration Consortium, and the BrightFocus Foundation (A2017458S). AMG served on the scientific advisory board for Genentech and Muna Therapeutics; and has stock options in Cognition Therapeutics. Funding sources did not play any role in the manuscript. The authors were not precluded from accessing the data and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104511.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Reiman E.M., Arboleda-Velasquez J.F., Quiroz Y.T., et al. Exceptionally low likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia in APOE2 homozygotes from a 5,000-person neuropathological study. Nat Commun. 2020;11:667. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews S.J., Fulton-Howard B., Goate A. Interpretation of risk loci from genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:326–335. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartzentruber J., Cooper S., Liu J.Z., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis, fine-mapping and integrative prioritization implicate new Alzheimer's disease risk genes. Nat Genet. 2021;53:392–402. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00776-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Rojas I., Moreno-Grau S., Tesi N., et al. Common variants in Alzheimer's disease and risk stratification by polygenic risk scores. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3417. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellenguez C., Küçükali F., Jansen I.E., et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nat Genet. 2022;54:412–436. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wightman D.P., Jansen I.E., Savage J.E., et al. A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1276–1282. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00921-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen I.E., Savage J.E., Watanabe K., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer's disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunkle B.W., Grenier-Boley B., Sims R., et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer's disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novikova G., Kapoor M., Tcw J., et al. Integration of Alzheimer's disease genetics and myeloid genomics identifies disease risk regulatory elements and genes. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1610. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21823-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosoy R., Fullard J.F., Zeng B., et al. Genetics of the human microglia regulome refines Alzheimer's disease risk loci. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01149-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopes K.P., Snijders G.J.L., Humphrey J., et al. Genetic analysis of the human microglial transcriptome across brain regions, aging and disease pathologies. Nat Genet. 2022;54:4–17. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00976-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero-Molina C., Garretti F., Andrews S.J., Marcora E., Goate A.M. Microglial efferocytosis: diving into the Alzheimer's disease gene pool. Neuron. 2022;110:3513–3533. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Márquez-Ropero M., Benito E., Plaza-Zabala A., Sierra A. Microglial corpse clearance: lessons from macrophages. Front Immunol. 2020;11:506. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magno L., Bunney T.D., Mead E., Svensson F., Bictash M.N. TREM2/PLCγ2 signalling in immune cells: function, structural insight, and potential therapeutic modulation. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16:22. doi: 10.1186/s13024-021-00436-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang N., Wang M., Jeevaratnam S., et al. Opposing effects of apoE2 and apoE4 on microglial activation and lipid metabolism in response to demyelination. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13024-022-00577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson T., Atwal J.K., Steinberg S., et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer's disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badimon A., Strasburger H.J., Ayata P., et al. Negative feedback control of neuronal activity by microglia. Nature. 2020;586:417–423. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2777-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tcw J., Qian L., Pipalia N.H., et al. Cholesterol and matrisome pathways dysregulated in astrocytes and microglia. Cell. 2022;185:2213–2233.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard J.W., Akay L.A., Davila-Velderrain J., et al. APOE4 impairs myelination via cholesterol dysregulation in oligodendrocytes. Nature. 2022;611:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05439-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandes N., Weissbrod O., Linial M. Open problems in human trait genetics. Genome Biol. 2022;23:131. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02697-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson I.K., Escott-Price V., Gatz M., et al. Measuring heritable contributions to Alzheimer's disease: polygenic risk score analysis with twins. Brain Commun. 2022;4:fcab308. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grotzinger A.D., de la Fuente J., Privé F., Nivard M.G., Tucker-Drob E.M. Pervasive downward bias in estimates of liability-scale heritability in GWAS meta-analysis: a simple solution. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;93:29. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escott-Price V., Hardy J. Genome-wide association studies for Alzheimer's disease: bigger is not always better. Brain Commun. 2022;4:fcac125. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcac125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Fuente J., Grotzinger A.D., Marioni R.E., Nivard M.G., Tucker-Drob E.M. Integrated analysis of direct and proxy genome wide association studies highlights polygenicity of Alzheimer's disease outside of the APOE region. PLoS Genet. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland D., Frei O., Desikan R., et al. The genetic architecture of human complex phenotypes is modulated by linkage disequilibrium and heterozygosity. Genetics. 2021;217 doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyaa046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor L.J. The distribution of common-variant effect sizes. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1243–1249. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wainschtein P., Jain D., Zheng Z., et al. Assessing the contribution of rare variants to complex trait heritability from whole-genome sequence data. Nat Genet. 2022;54:263–273. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00997-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uffelmann E., Huang Q.Q., Munung N.S., et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1:59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khani M., Gibbons E., Bras J., Guerreiro R. Challenge accepted: uncovering the role of rare genetic variants in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s13024-021-00505-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guen Y.L., Belloy M.E., Grenier-Boley B., et al. Association of rare APOE missense variants V236E and R251G with risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:652–663. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C.-C., Murray M.E., Li X., et al. APOE3-Jacksonville (V236E) variant reduces self-aggregation and risk of dementia. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc9375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vialle R.A., de Paiva Lopes K., Bennett D.A., Crary J.F., Raj T. Integrating whole-genome sequencing with multi-omic data reveals the impact of structural variants on gene regulation in the human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25:504–514. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01031-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills M.C., Rahal C. The GWAS Diversity Monitor tracks diversity by disease in real time. Nat Genet. 2020;52:242–243. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0580-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caliebe A., Tekola-Ayele F., Darst B.F., et al. Including diverse and admixed populations in genetic epidemiology research. Genet Epidemiol. 2022;46:347–371. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunkle B.W., Schmidt M., Klein H.-U., et al. Novel Alzheimer disease risk loci and pathways in African American individuals using the African genome resources panel. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:102–113. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherva R., Zhang R., Sahelijo N., et al. African ancestry GWAS of dementia in a large military cohort identifies significant risk loci. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;28:1293–1302. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01890-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shigemizu D., Mitsumori R., Akiyama S., et al. Ethnic and trans-ethnic genome-wide association studies identify new loci influencing Japanese Alzheimer's disease risk. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:151. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis A.C.F., Molina S.J., Appelbaum P.S., et al. Getting genetic ancestry right for science and society. Science. 2022;376:250–252. doi: 10.1126/science.abm7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nuytemans K., Vasquez M.L., Wang L., et al. Identifying differential regulatory control of APOE ϵ4 on African versus European haplotypes as potential therapeutic targets. Alzheimers Dementia. 2022;18:1930–1942. doi: 10.1002/alz.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansen I.E., van der Lee S.J., Gomez-Fonseca D., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis for Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;144:821–842. doi: 10.1007/s00401-022-02454-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan Q., Nho K., Del-Aguila J.L., et al. Genome-wide association study of brain amyloid deposition as measured by Pittsburgh Compound-B (PiB)-PET imaging. Mol Psychiatr. 2021;26:309–321. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damotte V., Lee S.J., Chouraki V., et al. Plasma amyloid β levels are driven by genetic variants near APOE, BACE1, APP, PSEN2: a genome-wide association study in over 12,000 non-demented participants. Alzheimers Dementia. 2021;17:1663–1674. doi: 10.1002/alz.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarnowski C., Ghanbari M., Bis J.C., et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies ancestry-specific associations underlying circulating total tau levels. Commun Biol. 2022;5:336. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03287-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmqvist S., Stomrud E., Cullen N., et al. An accurate fully automated panel of plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dementia. 2022;76:1060–1069. doi: 10.1002/alz.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi S.W., Mak T.S.-H., O'Reilly P.F. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:2759–2772. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leonenko G., Baker E., Stevenson-Hoare J., et al. Identifying individuals with high risk of Alzheimer's disease using polygenic risk scores. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4506. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24082-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fulton-Howard B., Goate A.M., Adelson R.P., et al. Greater effect of polygenic risk score for Alzheimer's disease among younger cases who are apolipoprotein E-ε4 carriers. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;99:101.e1–101.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mars N., Kerminen S., Feng Y.-C.A., et al. Genome-wide risk prediction of common diseases across ancestries in one million people. Cell Genom. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pergola G., Penzel N., Sportelli L., Bertolino A. Lessons learned from parsing genetic risk for schizophrenia into biological pathways. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;S0006-3223:01701. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong N.S., Tanigawa Y., Amar D., et al. Genetics of 35 blood and urine biomarkers in the UK Biobank. Nat Genet. 2021;53:185–194. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00757-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amariuta T., Ishigaki K., Sugishita H., et al. Improving the trans-ancestry portability of polygenic risk scores by prioritizing variants in predicted cell-type-specific regulatory elements. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1346–1354. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00740-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dornbos P., Koesterer R., Ruttenburg A., et al. A combined polygenic score of 21,293 rare and 22 common variants improves diabetes diagnosis based on hemoglobin A1C levels. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1609–1614. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruan Y., Lin Y.-F., Feng Y.-C.A., et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat Genet. 2022;54:573–580. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dumitrescu L., Mahoney E.R., Mukherjee S., et al. Genetic variants and functional pathways associated with resilience to Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2020;143:2561–2575. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramanan V.K., Lesnick T.G., Przybelski S.A., et al. Coping with brain amyloid: genetic heterogeneity and cognitive resilience to Alzheimer's pathophysiology. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:48. doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barry C.-J.S., Walker V.M., Cheesman R., Smith G.D., Morris T.T., Davies N.M. How to estimate heritability: a guide for genetic epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2022 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.