Abstract

The clinical manufacturing of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells includes cell selection, activation, gene transduction, and expansion. While the method of T-cell selection varies across companies, current methods do not actively eliminate the cancer cells in the patient’s apheresis product from the healthy immune cells. Alarmingly, it has been found that transduction of a single leukemic B cell with the CAR gene can confer resistance to CAR T-cell therapy and lead to treatment failure. In this study, we report the identification of a novel high-affinity DNA aptamer, termed tJBA8.1, that binds transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), a receptor broadly upregulated by cancer cells. Using competition assays, high resolution cryo-EM, and de novo model building of the aptamer into the resulting electron density, we reveal that tJBA8.1 shares a binding site on TfR1 with holo-transferrin, the natural ligand of TfR1. We use tJBA8.1 to effectively deplete B lymphoma cells spiked into PBMCs with minimal impact on the healthy immune cell composition. Lastly, we present opportunities for affinity improvement of tJBA8.1. As TfR1 expression is broadly upregulated on many cancers, including difficult to treat T-cell leukemias and lymphomas, our work provides a facile, universal, and inexpensive approach for comprehensively removing cancerous cells from patient apheresis products for safe manufacturing of adoptive T-cell therapies.

Keywords: Nucleic Acids, Cells, Cancer, Isolation, Molecular Structure

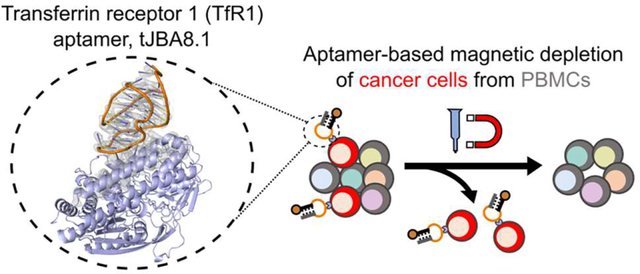

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has gained significant traction in the oncology field, with six FDA-approved therapies to-date: four for treating relapsed or refractory (r/r) CD19+ B-cell malignancies (Novartis’s Kymriah, Gilead-Kite’s Yescarta and Tecartus, and Bristol Myers Squibb-Juno Therapeutic’s Breyanzi) and another two for treating r/r BCMA+ multiple myeloma (Bristol Myers Squibb-2seventy bio’s Abecma and Janssen Pharmaceuticals-Legend Biotech’s Carvykti).1–8 In these treatments, a patient’s T cells journey through an elaborate manufacturing process that consists of 1) enrichment from a leukapheresis product, 2) activation ex vivo, 3) lentiviral or retroviral expression of a CAR that directs T-cell function against a tumor-associated antigen, 4) expansion to therapeutically relevant numbers, and 5) re-infusion into the patient’s body for cancer elimination.9 Given the intricate nature of this operation, there is a continual need for further innovation at each production step to reduce the costs and increase the efficacy and safety of these adoptive T-cell therapies.10

T-cell enrichment or selection is a pivotal step in CAR T-cell manufacturing, as the cell composition and purity used in subsequent activation and transduction steps can influence the outcome of the therapy. For Kymriah, Yescarta, and Abecma, T cells are indirectly enriched by collecting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from leukapheresis product using counterflow centrifugal elutriation, which removes most monocytes, granulocytes, platelets, and residual red blood cells based on differences in cell size and density relative to lymphocytes.11–13 However, this selection approach is unable to discriminate healthy T cells from circulating cancerous lymphocytes, thereby retaining tumor cells in downstream manufacturing steps that can drive uncontrollable activation and exhaustion of the CAR T-cell product.14 Additionally transduction of a single leukemic B cell with the CAR gene during CAR T-cell manufacturing caused in cis epitope masking that led to a patient’s relapse and eventual death.15 These issues highlight the need for complete removal of cancerous lymphocytes during the selection step prior to further CAR T-cell manufacturing.

To address this problem, especially for patients with high circulating blast and leukemia cell counts, Tecartus, Breyanzi, and Carvykti rely on direct isolation of T cells. Whereas Tecartus and Carvykti isolate bulk CD3+ T cells,5,16 Breyanzi separately isolates helper CD4+ T cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells for CAR T-cell production and later infuses the patient with a defined 1:1 composition of the subsets.6 Breyanzi is associated with lower rates of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity than Kymriah and Yescarta while remaining equally effective.2,3,6 However, the direct isolation of T cells is expensive, typically relying on costly antibody- or multimerized Fab-coated magnetic beads that target either the CD3, CD4, and/or CD8 T-cell markers for positive enrichment or unwanted immune cell markers for negative enrichment.17 Furthermore, these approaches do not actively remove the cancer cells from a patient’s leukapheresis product. In contrast to B-cell malignancies, malignant T cells can be difficult to separate from healthy T cells used for manufacturing CAR T-cell therapies.18,19 Accordingly, as autologous CAR T-cell therapies are broadened to treat diverse hematological malignancies, an inexpensive and universal method for removing cancerous cells from healthy PBMCs will be imperative for their safe manufacturing.

DNA aptamers, single-stranded oligonucleotides that fold into sequence-specific secondary structures, are molecular recognition agents that can address the current deficiencies of cancer cell removal in adoptive T-cell manufacturing. Aptamers can bind their targets with affinities comparable to antibodies, but unlike antibodies they are synthesized chemically with high reproducibility and relatively low cost.20 Aptamers can also be controllably modified at any position for facile immobilization onto solid supports (e.g., hydrogels) for affinity-based separations.21 Finally, aptamer binding to their targets can be reversed by disrupting aptamer structure, for example, by use of a complementary sequence.21,22 Demonstrating these points, our group previously identified CD8-binding DNA aptamers and used them to tracelessly isolate CD8+ T cells via magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with comparable purity, yield, and downstream CAR functionality as those isolated from commercial antibody-based methods.23

Aptamers can be identified through a library selection approach.24–26 The panning process in which aptamers go through rounds of positive and negative selection against whole cells, termed cell-SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment), has become an attractive method for discovering aptamers that can differentiate malignant cells from healthy normal cells.27 Cell-SELEX thus holds great promise for discovering DNA aptamers that can selectively bind and deplete circulating leukemia and lymphoma cells from PBMCs at low cost prior to CAR T-cell manufacturing.

Here, we report the discovery, characterization, and application of a high-affinity transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1, also known as CD71)-binding aptamer for cancer cell depletion in CAR T-cell manufacturing. The aptamer, named tJBA8.1 after its truncation, was discovered by cell-SELEX using Jurkat T-leukemia cells for positive selection. Pull-down assays identified TfR1, an iron-uptake receptor not expressed on resting immune cells but upregulated on actively dividing and cancerous cells, as the binding target of tJBA8.1. We characterized the tJBA8.1-TfR1 interaction by flow cytometry, biolayer interferometry, and competition studies with holo-transferrin. In addition, we present the first cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) map of TfR1 in complex with an aptamer, which we used to guide de novo model building of tJBA8.1 and its interactions with TfR1. As proof of concept, we further employed tJBA8.1 in MACS to remove spiked Raji B-lymphoma cells from PBMCs with high yield and minimal impact on the healthy immune cell composition. Lastly, we describe a point mutation to the aptamer sequence for affinity improvement. Given the broad expression of TfR1 on many cancers, including difficult-to-distinguish T-cell leukemias and lymphomas, we anticipate that this method could be universally used for the depletion of circulating cancer cells from patient PBMCs prior to downstream CAR T-cell manufacturing, leading to a safer, more potent, and cost-mindful therapy.

RESULTS

Discovery of the Jurkat-Binding Aptamer 8.1 (JBA8.1) by Cell-SELEX and Stem Truncation to tJBA8.1.

In an initial effort to identify aptamers that bind the human CD3 and CD28 T-cell receptors, we performed cell-SELEX using CD3+CD28+ Jurkat T-leukemia cells for positive selection and CD3−CD28− J.RT3-T3.5 cells, a chemically-generated mutant of the Jurkat cell line, for negative/counter selection (Figure 1A).28 We started with an initial positive selection against Jurkat cells with a naive library of 1016 theoretical unique ssDNA sequences and then completed seven additional rounds of sequential positive selection with Jurkat cells and negative selection with J.RT3-T3.5 cells with increased stringency (Table S1). Prior to cell binding, aptamer sequences were folded by heating in DPBS supplemented with ~0.9 mM Ca2+ and ~5.5 mM Mg2+ ions for 5 min at 95 °C followed by snap cooling on ice, and further details on folding and binding conditions are provided in the Methods section. Flow cytometry binding of aptamer pools from the individual SELEX rounds revealed substantial binding to both Jurkat and J.RT3-T3.5 cells starting in round 5 that plateaued by round 8 (Figure S1). We observed preferential binding of aptamer pools to Jurkat cells in later selection rounds, but differences in cell size and absolute number of receptors per cell may have biased binding to larger Jurkat cells.

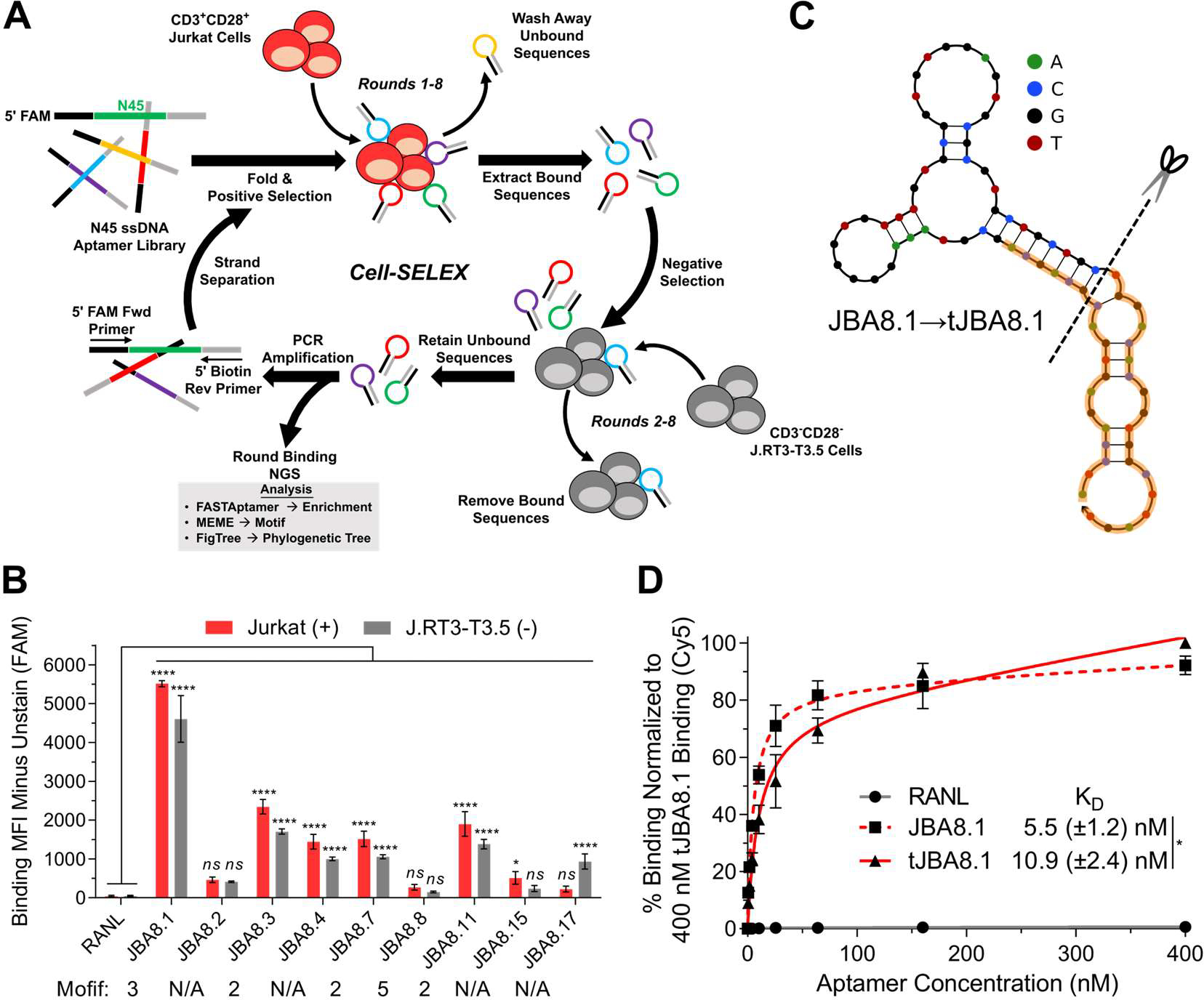

Figure 1.

Cell-SELEX and post-SELEX truncation lead to the development of the tJBA8.1 aptamer. (A) Schematic of cell-SELEX using CD3+CD28+ Jurkat cells for positive selection and CD3−CD28− J.RT3-T3.5 cells for negative selection. (B) Binding median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 100 nM RANL and individual aptamers identified from round 8 of cell-SELEX to Jurkat cells and J.RT3-T3.5 cells by flow cytometry. Aptamers belonging to predicted motifs are indicated. Graph bars and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments. ns > 0.05, *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 (ordinary two-way ANOVA with Šídák correction). (C) MFE secondary structures of JBA8.1 and its truncation (tJBA8.1), predicted using NUPACK (temperature = 4 °C; Na+ = 137 mM; Mg2+ = 5.5 mM). The dashed line indicates the site of truncation, whereas the orange highlighting denotes the 18-nt flanking constant regions. (D) Flow cytometry binding curves of RANL, JBA8.1, and tJBA8.1 to Jurkat cells, normalized to 400 nM tJBA8.1 binding. The curves represent a nonlinear regression assuming one-site total binding. KD values were calculated by averaging the individual regression values of the independent experiments. Data points and error bars, and KD values, represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments with technical duplicates. *P < 0.05 (two-sided unpaired t-test). FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; Cy5, cyanine 5.

We conducted next generation sequencing (NGS) of the ssDNA pools from all 8 rounds using the primers detailed in Table S2 and analyzed the results using FASTAptamer toolkit to calculate fold-enrichment of unique aptamer sequences over rounds of cell-SELEX.29 As unique sequence reads were low for rounds 1–4, we only used FigTree software and MEME analysis on the top 50 aptamers sequences over later rounds 5–8 to generate phylogenetic trees and identify consensus motifs, respectively (Figure S2).30,31 In round 5, top aptamer sequences were primarily characterized by one of three short motifs (Motifs 1, 2, and 3) with low individual sequence representation (<0.4%). Sequence representation progressively increased in rounds 6 and 7, with top sequences representing as much as 6.3% and 10.6% of the pool, respectively. By round 8, Motif 3 expanded to encompass the whole 45-nucleotide (nt) random region and a new 40-nt motif, Motif 5, emerged, with top aptamers belonging to each motif displaying robust tree clustering and thus high sequence similarity. Notably, the most prevalent aptamer in round 8, which belonged to Motif 3, represented 21.1% of the entire sequence pool. Table S3 lists the predicted motifs, sequences, and the round-by-round enrichment of the top 50 aptamers identified from round 8.

We selected nine Jurkat-binding aptamers from round 8 (Table S4), named JBA8.X (where “X” is the aptamer’s rank in Table S3), for cell binding studies based on their representation, motif, and enrichment across rounds. None of the selected fluorescein-labeled aptamers displayed specific binding for Jurkat cells over J.RT3-T3.5 cells, indicating that the SELEX process did not enrich CD3- or CD28-binding aptamers (Figure 1B). Fluorescein-labeled JBA8.1 from Motif 3, JBA8.3, JBA8.7, and JBA8.11 from Motif 2, and JBA8.4 without a motif all displayed robust binding to both Jurkat and J.RT3-T3.5 cells compared to a random aptamer from the naïve library (RANL), with JBA8.1 distinguishing itself with greater than 2-fold higher binding than the other aptamers. JBA8.8 did not significantly bind to either cell line despite belonging to the 40-nt Motif 5, whereas JBA8.17 without a motif displayed preferential binding for J.RT3-T3.5 cells. Given these data, we speculate our negative selection steps were ineffective, possibly due to the order of selection steps (positive/negative versus negative/positive) or the insufficient number of J.RT3-T3.5 cells used. In the future, negative selection can be attempted in the first round of SELEX for added stringency, and the input of positive and negative selection cells in each round can be adjusted in real time using a formula that incorporates the binding data from the previous round.32 We chose the JBA8.1 aptamer for further testing due to it having the most pronounced binding to Jurkat T-leukemia cells.

To reduce aptamer production cost in downstream assays, we first sought to truncate the JBA8.1 aptamer. Using the NUPACK application to predict the minimum free energy (MFE) structure of JBA8.1,33 we find that the simulated structure of JBA8.1 conforms well to the intended library design, with the majority of the 45-nt Motif 3 forming a multi-hairpin structure that sits on top of a stem comprised of the partially complementary 18-nt flanking primer sequences (Figure 1C). As we hypothesized that the stem does not directly contribute to aptamer binding, we truncated the stem of JBA8.1 sequence, removing 12 nt from the 5’ constant region and all 18 nt from the 3’ constant region, yielding the 51-nt tJBA8.1 aptamer sequence (Figure 1C and Table S4). In binding studies with Jurkat cells, we found that JBA8.1 has an apparent binding affinity (KD) of 5.5 ± 1.2 nM versus that of 10.9 ± 2.4 nM for tJBA8.1, demonstrating a minimal impact from the truncation on aptamer binding. (Figure 1D). We thus proceeded with the more cost-effective tJBA8.1 for receptor identification, further characterization, and application studies.

Identification and Validation of Transferrin Receptor 1 (TfR1) as a Target of tJBA8.1.

To investigate the type of molecule targeted by tJBA8.1, we labeled Jurkat cells with Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 at 4 °C followed by enzymatic treatment with trypsin, a serine endopeptidase that cleaves extracellular proteins. tJBA8.1 binding was almost completely abolished after trypsin treatment (Figure S3A), suggesting that the aptamer targets trypsin-sensitive cell membrane proteins. We also visualized Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 binding to Jurkat cell membranes at 4 °C by confocal microscopy (Figure S3B).

We next adapted a reported aptamer-based pull-down assay designed for identification of target membrane receptors.34 Briefly, we bound biotinylated tJBA8.1 to precleared proteins in solubilized Jurkat cell membrane extracts, isolated the aptamer-bound membrane proteins using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, and analyzed the recovered protein by SDS-PAGE. Compared to a control sample that was purified with biotin-saturated streptavidin beads without tJBA8.1, we observed two distinct protein bands that were highly enriched by tJBA8.1 at approximately 200 kDa (band a) and 100 kDa (band b) (Figure 2A). The protein bands were extracted, digested, analyzed by mass spectrometry, and matched to the human transferrin receptor protein 1 (TfR1; also known as CD71) (Figure 2B). Peptides extracted from the higher molecular weight band (a) covered 62% of the TfR1 amino acid sequence, whereas the lower molecular weight band (b) covered 58%. The presence of two bands is consistent with the structure of TfR1, which is a homodimer composed of two disulfide-linked monomers.35

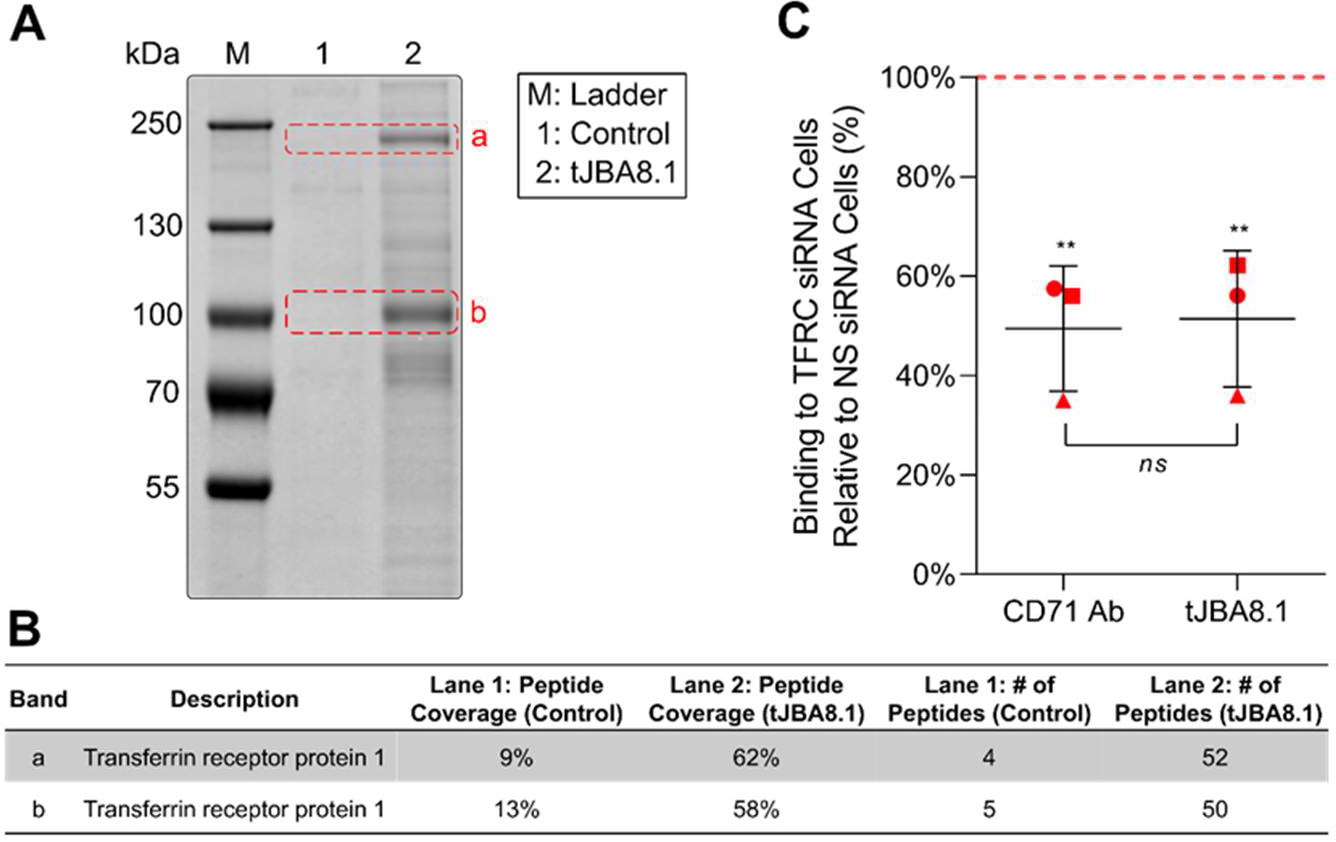

Figure 2.

TfR1 is identified as the target of tJBA8.1. (A) Colloidal blue-stained 8% SDS-PAGE gel of Jurkat cell membrane proteins pulled down by tJBA8.1. The control lane represents proteins captured by biotin-saturated magnetic beads only. Bands a and b (dashed red boxes) from both lanes were excised for mass spectrometry analysis. (B) Summary of the protein with the highest peptide coverage and number of peptides identified in each excised band by mass spectrometry. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of FITC-labeled CD71 Ab and 25 nM Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 binding to Jurkat cells 24 h after nucleofection with TFRC siRNA duplexes. Red, dashed horizontal line represents binding to non-specific (NS) siRNA-treated controls to which the TFRC siRNA data points were normalized. Horizontal lines and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.01 (significance between ligand staining on TFRC siRNA- and NS siRNA-treated cells; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). Ns > 0.05 (significance between the relative CD71 Ab and tJBA8.1 staining in pairwise experiments; two-sided paired t-test). Cy5, cyanine 5; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

TfR1 is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein that regulates the uptake of transferrin-bound iron needed for cellular metabolism and proliferation.36 TfR1 is thus ubiquitously expressed at low levels on many cell types, with elevated expression on rapidly dividing cells such as activated lymphocytes and cancer cells.37–39 To validate that tJBA8.1 binds TfR1, we used short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes (Table S5) to knockdown the expression of TfR1 encoded by the TFRC gene in Jurkat cells and evaluated aptamer binding. Compared to cells that were nucleofected with non-specific (NS) siRNA, cells nucleofected with TFRC siRNA had 51% reduced TfR1 expression as evaluated by anti-CD71 antibody (CD71 Ab) staining, which matched closely with the observed 49% reduction in tJBA8.1 binding (Figure 2C). We also evaluated TfR1 expression on the Jurkat cells and J.RT3-T3.5 cells used in cell-SELEX. In agreement with the binding profiles of the cell-SELEX aptamer pools and JBA8.1 (Figure S1 and Figure 1B), both cell lines robustly express TfR1 (Figure S4A), with Jurkat cells having higher expression than J.RT3-T3.5 cells (Figure S4B). Lastly, as TfR1 is expressed negligibly on resting T cells but is upregulated upon antigen and cytokine stimulation,38 we evaluated tJBA8.1 binding to unactivated and day 3 CD3/CD28 Dynabead-activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. For both subsets, tJBA8.1 binding was low to unactivated T cells but greatly increased after Dynabead activation (Figure S5A). Furthermore, we found that JBA8.1 binding correlated strongly with TfR1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells over 7 days of Dynabead activation (Figure S5B). Collectively, these results confirm that TfR1 is a binding target of JBA8.1/tJBA8.1.

Characterization of tJBA8.1 Binding to TfR1 and Competition with Other TfR1 Ligands.

We next used bio-layer interferometry (BLI) to characterize tJBA8.1 binding kinetics to recombinant TfR1. We immobilized biotinylated TfR1 onto streptavidin biosensors to avoid avidity effects from homodimeric TfR1 binding to immobilized aptamers. Demonstrating fast and high-affinity binding kinetics, tJBA8.1 bound the TfR1 protein with a KD value of 25.11 ± 0.19 nM (Figure 3A and Table S6). We further tested by BLI whether aptamers JBA8.3, JBA8.4, JBA8.7, JBA8.11, and JBA8.15, bind to TfR1. Despite these aptamers displaying statistically significant binding to Jurkat cells in Figure 1B, none of them appreciably bound TfR1 besides JBA8.1 (Figure S6). Lastly, we evaluated binding of His-tagged mouse recombinant TfR1 to immobilized tJBA8.1 by BLI, but results were negative despite positive control antibody binding, demonstrating that tJBA8.1 does not interact with mouse TfR1 (Figure S7A,B).

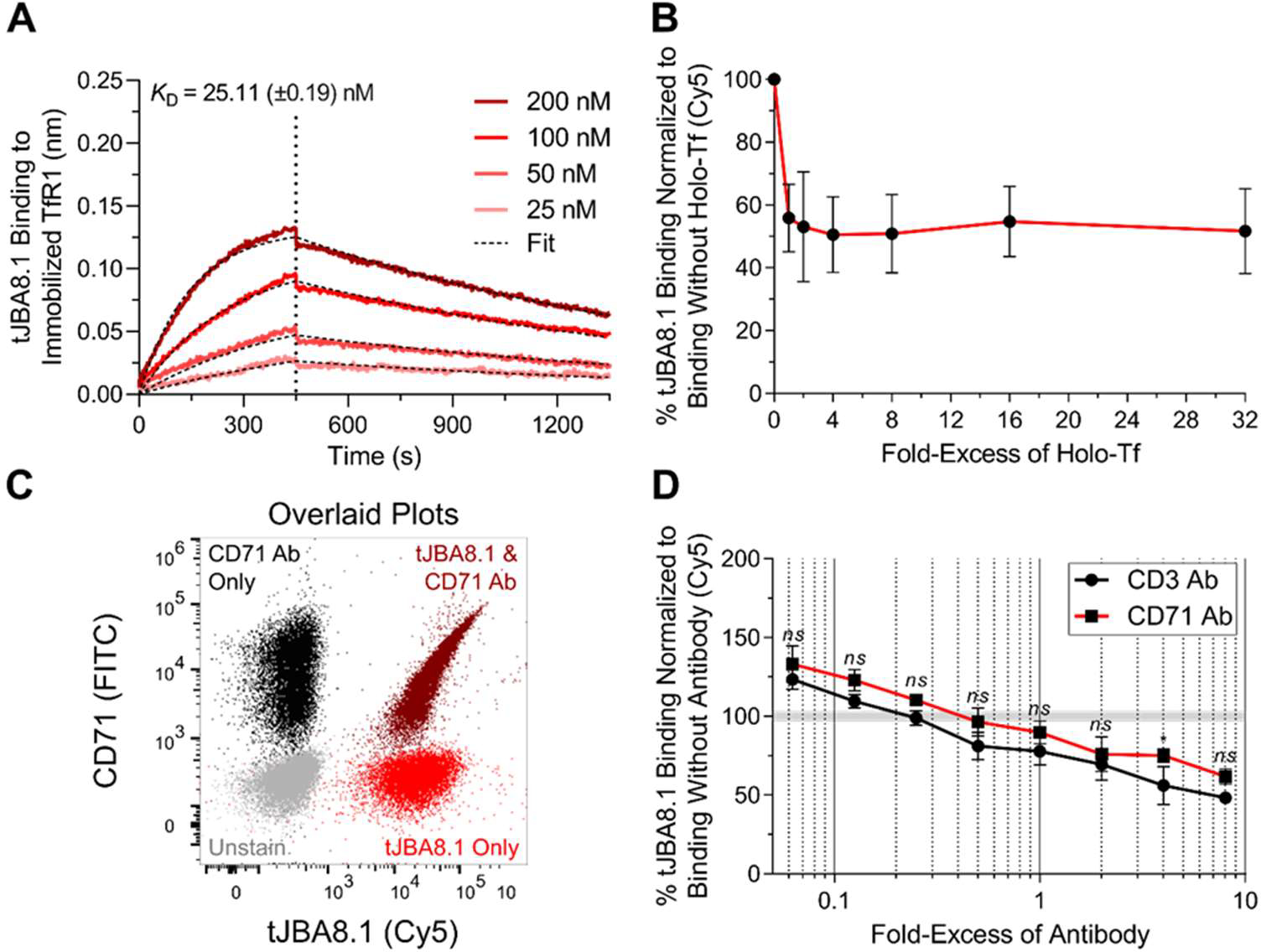

Figure 3.

tJBA8.1 competes with holo-Tf but not antibody clone CY1G4 for binding to TfR1. (A) Association and dissociation kinetics of serially diluted FAM-labeled tJBA8.1 binding to biotinylated TfR1 immobilized on streptavidin biosensors by BLI. The association phase is illustrated from 0–450 s, whereas dissociation is shown from 450–1350 s (separated by the vertical dotted line). KD values were calculated by performing a global fit of the multi-concentration kinetic data to a 1:1 binding model. KD values represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 4 individual concentrations of aptamers. (B) Competitive binding of 25 nM Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 with varying fold-excess of holo-Tf to Jurkat cells by flow cytometry. Binding was normalized to aptamer-stained controls without holo-Tf. Data points and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments. ns > 0.05, *P < 0.05 (ordinary two-way ANOVA with Šídák correction). (C) Overlaid flow cytometry plots of unstained (grey), FITC-labeled CD71 Ab single-stained (black), 25 nM Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 single-stained (red), and antibody and aptamer co-stained (dark red) Jurkat cells. Plots are representative of n = 2 independent experiments. (D) Competitive binding of 25 nM Cy5-labeled tJBA8.1 with varying fold-excess of CD3 or CD71 Ab to Jurkat cells by flow cytometry. Binding was normalized to aptamer-stained controls without antibody. Data points and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments. ns > 0.05, *P < 0.05 (ordinary two-way ANOVA with Šídák correction). FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Cy5, cyanine 5; FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein.

Iron is delivered intracellularly to cells via a transferrin cycle. Specifically, iron-bound transferrin (holo-Tf) binds to TfR1 for uptake, after which iron is released from transferrin under acidic endosomal pH and the resulting iron-free transferrin (apo-Tf) is recycled to the cell surface for receptor dissociation at neutral pH.40 To test if tJBA8.1 competes with holo-Tf for binding to TfR1, we co-incubated Jurkat cells with a fixed concentration of labeled tJBA8.1 and varying concentrations of holo-Tf as a competitor. tJBA8.1 binding was reduced by half upon competition with just 1-fold excess of holo-Tf, confirming that tJBA8.1 and holo-Tf share proximal binding sites on TfR1 (Figure 3B). However, relative tJBA8.1 binding plateaued at 50% and did not further decrease even when holo-Tf was added at 32-fold excess, suggesting that tJBA8.1 has a transferrin- or TfR1-independent binding component to Jurkat cells. We also co-stained Jurkat cells with tJBA8.1 and the CD71 Ab (clone CY1G4) used previously, which is known to bind a TfR1 epitope distinct from that of holo-Tf.41 We observed a striking positive correlation between CD71 Ab and tJBA8.1 staining, demonstrating that tJBA8.1 can bind TfR1 on cells simultaneously with the CD71 Ab (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the binding behavior of tJBA8.1 to Jurkat cells in the presence of various concentrations of the CD71 Ab (clone CY1G4) was statistically indistinguishable from binding in the presence of an anti-CD3 antibody (CD3 Ab) control (Figure 3D). Thus, tJBA8.1 and the CD71 Ab (clone CY1G4) do not share an overlapping binding epitope on TfR1.

Cryo-EM of tJBA8.1-TfR1 Complex.

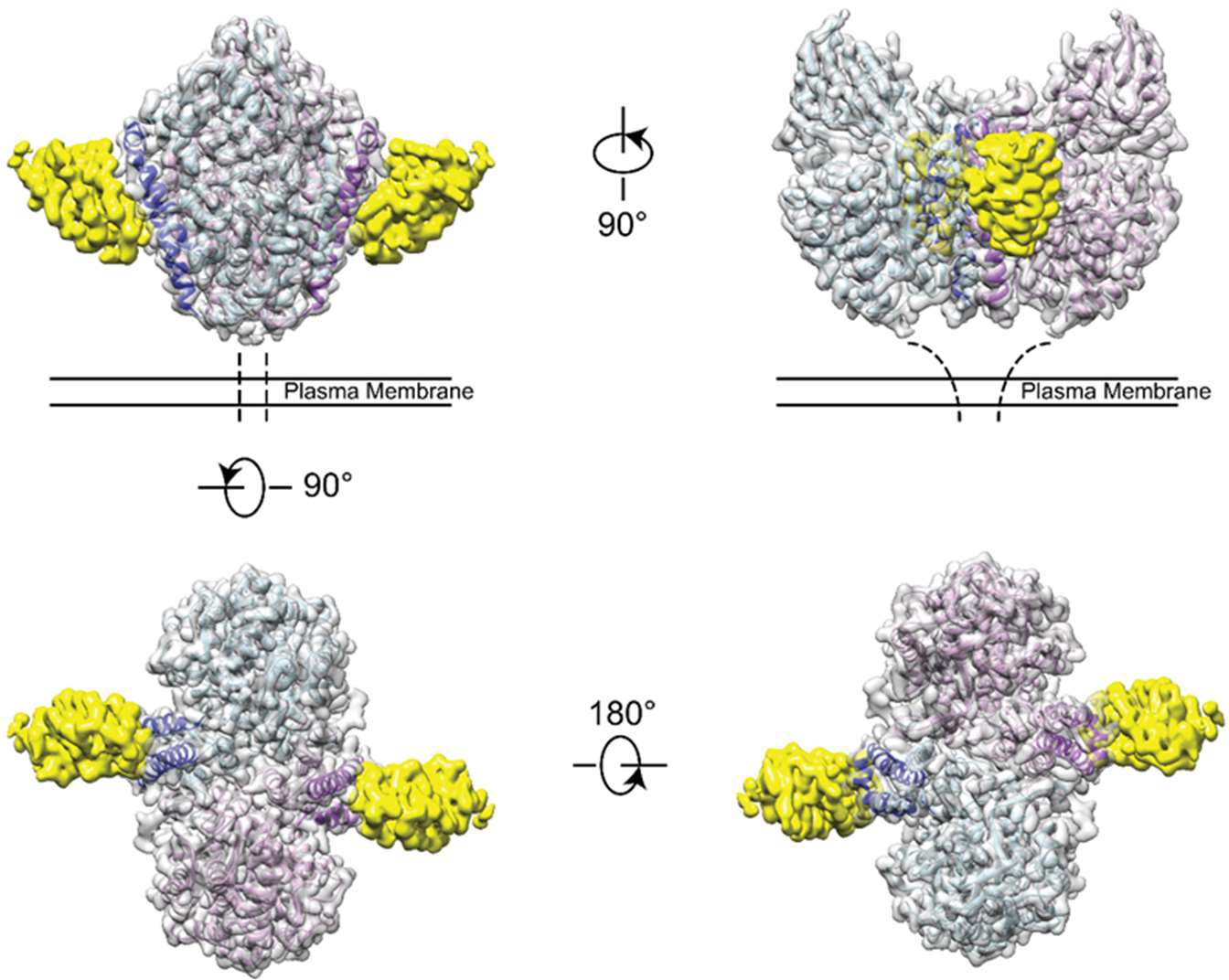

To better elucidate the binding interaction between tJBA8.1 and TfR1, we first performed cryo-EM on homodimeric His-tagged TfR1 bound to tJBA8.1. We obtained a cryo-EM map at an overall 2.54 Å resolution and refined an existing crystal structure of homodimeric TfR1 (PDB 1CX8) against the map (parameters for collection and processing listed in Table S7),42 which revealed two tJBA8.1 aptamers (yellow) binding to a single TfR1 homodimer (grey), with each TfR1 monomer (light blue and light purple) bound independently by an aptamer (Figure 4). Each tJBA8.1 aptamer adopts a distal double-stranded helical structure and a more complicated structure proximal to the binding site. Analyzing this binding epitope, we find that tJBA8.1 contacts α helices 1, 2, and 3 (dark blue and dark purple) of each TfR1 monomer helical domain (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

tJBA8.1 binds the helical domain of TfR1. Cryo-EM density map and refined structure of tJBA8.1-bound TfR1. Four views are shown with color coding (yellow: tJBA8.1 density; gray: TfR1 homodimer density; light blue and light purple: individual TfR1 monomer structures; dark blue and dark purple: α helices 1, 2, and 3 of each TfR1 monomer helical domain).

De Novo Modeling of TfR1-Bound tJBA8.1 and Interactions at the tJBA8.1-TfR1 Interface.

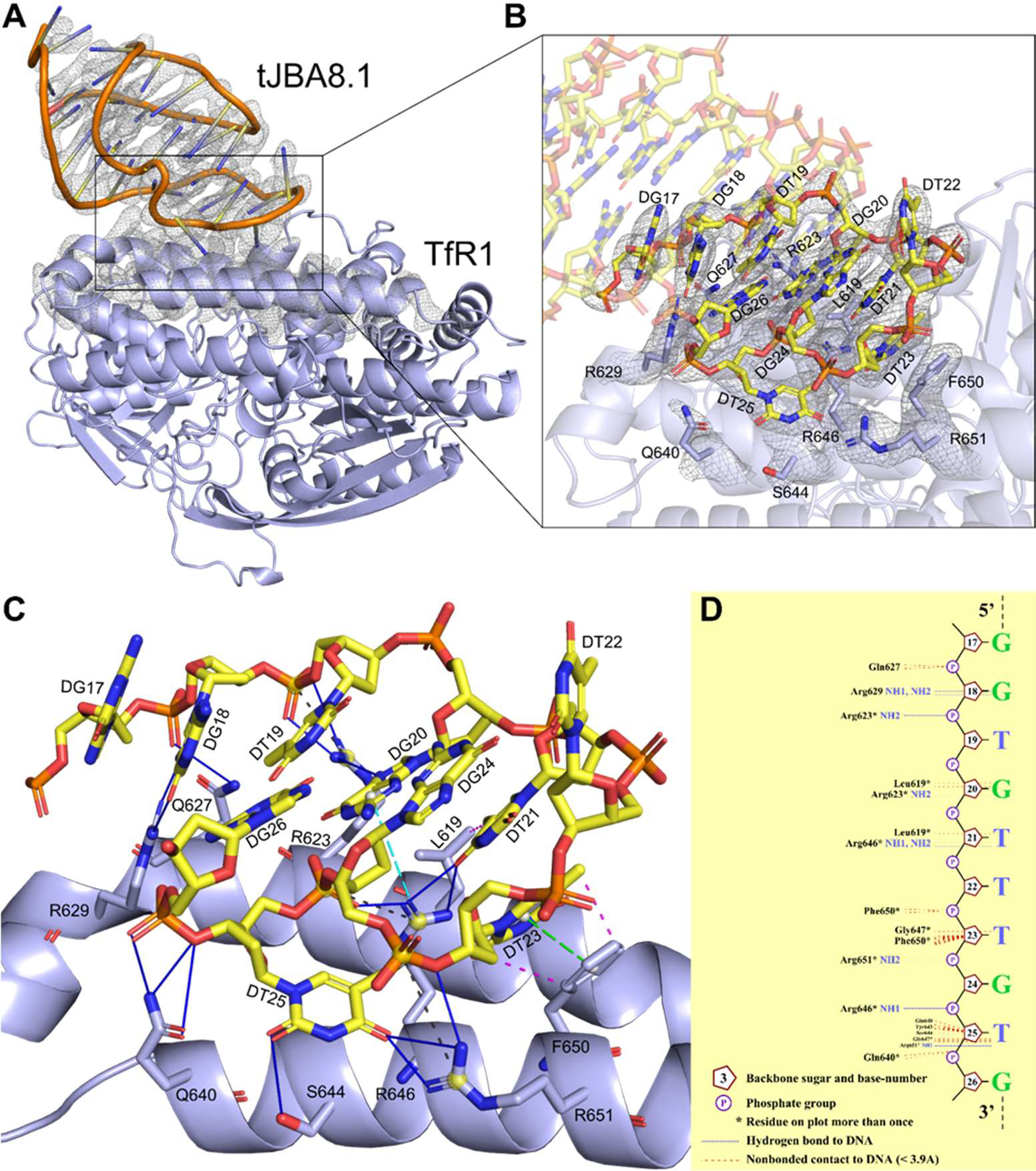

We next modeled the three-dimensional (3D) structure of tJBA8.1 within its electron density from the cryo-EM data in Figure 4. Our attempts to convert the predicted 2D structure of tJBA8.1 into a 3D structure followed by rigid-body fitting into the aptamer density failed, perhaps because aptamers can conformationally change upon target binding due to their structural plasticity and/or current DNA folding software do not account for non-Watson-Crick base pairing interactions.43–46 Since the electron density at the tJBA8.1 core nearest to the TfR1 binding site could be resolved to the level of DNA bases, we conducted unambiguous de novo model building of the aptamer structure. While it was difficult to distinguish the different purines and pyrimidines at certain places in the electron density, we were able to sufficiently differentiate purines from pyrimidines. To our benefit, tJBA8.1 has a unique instance of three consecutive pyrimidines (T21, T22, and T23), providing us a definitive starting point for aptamer model building within the electron density map. The resulting de novo built model of TfR1-bound tJBA8.1 is shown in Figure 5A and Movie S1, and parameters concerning structure refinement and validation are listed in Table S7. We were only able to model tJBA8.1 from A11 to G40; there was no interpretable density to model nucleotides 1-GCAGCAGCGT-10 and 41-CGTGCTGCTGC-51 at the aptamer’s 5’ end and 3’ end, respectively. As these two sequences of nucleotides should mostly base pair to form the distal tJBA8.1 stem, we hypothesize that this non-binding stem region was too flexible to be resolved by cryo-EM.

Figure 5.

De novo model of tJBA8.1 built into the cryo-EM map enables detailed characterization of the interactions at the tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface. (A) Cartoon representation of tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex (yellow: tJBA8.1; lavender blue: TfR1) modeled in the cryo-EM density maps (overlayed grey mesh). For clarity, only one monomer of the tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex is shown, and the overlaid cryo-EM density maps are restricted to tJBA8.1 and the binding interface on TfR1. (B) Zoomed-in view of the modeled tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface within the cryo-EM density maps showing the overall fit of the model. tJBA8.1 nucleotides and TfR1 protein residues in close contact at the binding interface are labeled and shown as sticks with atom color coding (yellow: nucleotide carbon; lavender blue: protein carbon; blue: nitrogen; red: oxygen; orange: phosphate). (C) Molecular interactions at the modeled tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface, calculated using PDBePISA and PLIP. Different lines and color coding are used to denote the different interactions (blue solid: hydrogen bonds; black dashed: salt bridges; magenta dashed: hydrophobic interactions; green dashed with ring centroids: pistacking; cyan dashed with centroids: cation-pi). The list of detected interactions at the tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface can be found in Table S8. (D) Schematic diagram of hydrogen bonds and nonbonded contacts at the modeled tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface, generated using NUCPLOT.

Analyzing the tJBA8.1-TfR1 binding interface within the cryo-EM density map using the de novo built aptamer model and refined structure of TfR1, we found that tJBA8.1 has a single continuous nucleotide sequence comprised of 17-GGTGTTTGTG-26 that contacts Leu619 and Arg623 of helix α1 (aa 613–626), Gln627 that connects helix α1 with helix α2, Arg629 of helix α2 (aa 629–634), and Gln640, Ser644, Arg646, Phe650, and Arg651 of helix α3 (aa 640–662) in the TfR1 helical domain (Figure 5B and Movie S2). We inputted the modeled tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex into PDBePISA and PLIP programs to identify the types of interactions that occur at the tJBA8.1-TfR1 binding interface between individual protein residues and nucleotides.47,48 Notably, we detected an extensive hydrogen bonding network formed by Arg623, Gln627, Arg629, Gln640, Ser644, Arg646, and Arg 651 of TfR1 with the bases, sugars, and/or phosphates of G18, T19, G20, T21, T23, T25, and G26 in tJBA8.1 (Figure 5C and Table S8). In addition to these, we also detected stabilizing hydrophobic interactions between Leu619 and the base of T21 and Phe650 and the base and sugar of T23, a pistacking interaction between the same Phe650 and T23 pair, a cation-pi interaction between Arg646 and the base of G20, and lastly salt bridges between Arg623, Arg646, and Arg651 and the phosphates of T19, T25, an T24, respectively. Using NUCPLOT to organize many of the detected tJBA8.1-TfR1 interactions into a simple schematic diagram,49 we intriguingly found that TfR1 does not directly interact with the bases of T19, T22, G24, and G26 but instead with their associated sugar and phosphate groups (Figure 5D). This may suggest that these nucleotide positions can tolerate base substitutions without affecting tJBA8.1 binding to TfR1, assuming the substitutions do not change aptamer structure or cause steric hindrance with other TfR1 residues. NUCPLOT also identified that Tyr643 and Gly647, while not strongly interacting with tJBA8.1, may form weak non-bonded contacts with T23 and T25 due to their <3.9 Å proximity that results in possible van der Waals forces.

Besides the direct DNA-protein interactions detected at the tJBA8.1-TfR1 binding interface, we identified two other sets of interactions that may contribute to tJBA8.1 structure and/or binding. One interaction is an intramolecular G-quartet (also known as G-tetrad) comprised of G16, G28, G33, and G38 that may stabilize the 3D folding of TfR1-bound tJBA8.1 (Figure S8A). When modeled into their electron densities, these guanine nucleotides have a planar arrangement with Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding between their bases consistent with that of a G-quartet. The second set of interactions involves two metal ions found in the cryo-EM density. One metal ion coordinates the bases of G17 and G18, the phosphates of G26 and G28, and the guanidino group of Arg629 and the other metal ion coordinates the phosphates of G34, A35, and G36 and the base of T37 (Figure S8B,C and Movie S1). Of importance, G28 is shared by both sets of interactions, bridging the two into an expansive interaction network that may play a large role in complexed tJBA8.1 structural stability and its binding to TfR1.

The C-lobe of holo-Tf is known to bind α helices 1, 2, and 3 of the TfR1 helical domain, specifically to Leu619 and Arg623 of helix α1, Arg629 of helix α2, and Gln640, Tyr643, Arg646, Phe650, and Arg651 of helix α3.50 All these amino acid residues are similarly bound by tJBA8.1 on TfR1, definitively demonstrating that tJBA8.1 and holo-Tf share highly overlapping binding epitopes on TfR1. Besides holo-Tf, TfR1 has other natural ligands that may share TfR1-binding epitopes with tJBA8.1. HFE is a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ⅰ-like membrane protein that is known to compete with holo-Tf at its TfR1-binding site to regulate iron uptake,50–53 and mutation of HFE can cause iron overload that resembles hereditary hemochromatosis via hepatic hepcidin deficiency.54,55 HFE has previously been shown to have a large binding interface with TfR1, interacting with the same α helices in the TfR1 helical domain that both tJBA8.1 and holo-Tf bind.51 Notably, Leu619 of TfR1 contributes to a strong hydrophobic core with Val78 and Trp81 of HFE, Arg623 has contact with Leu22 of HFE, Arg629 has several polar interactions with residues in both helices α1 and α2 of HFE, and Gln640 forms hydrogen bonds with Glu146 and His150 of HFE. As these key TfR1 residues are also targeted by tJBA8.1, it is probable that tJBA8.1 competes with membrane-bound HFE for binding to TfR1, like holo-Tf does. The binding interface that tJBA8.1, holo-Tf, and HFE share on TfR1 is depicted in Figure S9A–C.

tJBA8.1-Mediated Depletion of B-Lymphoma Cells from PBMCs.

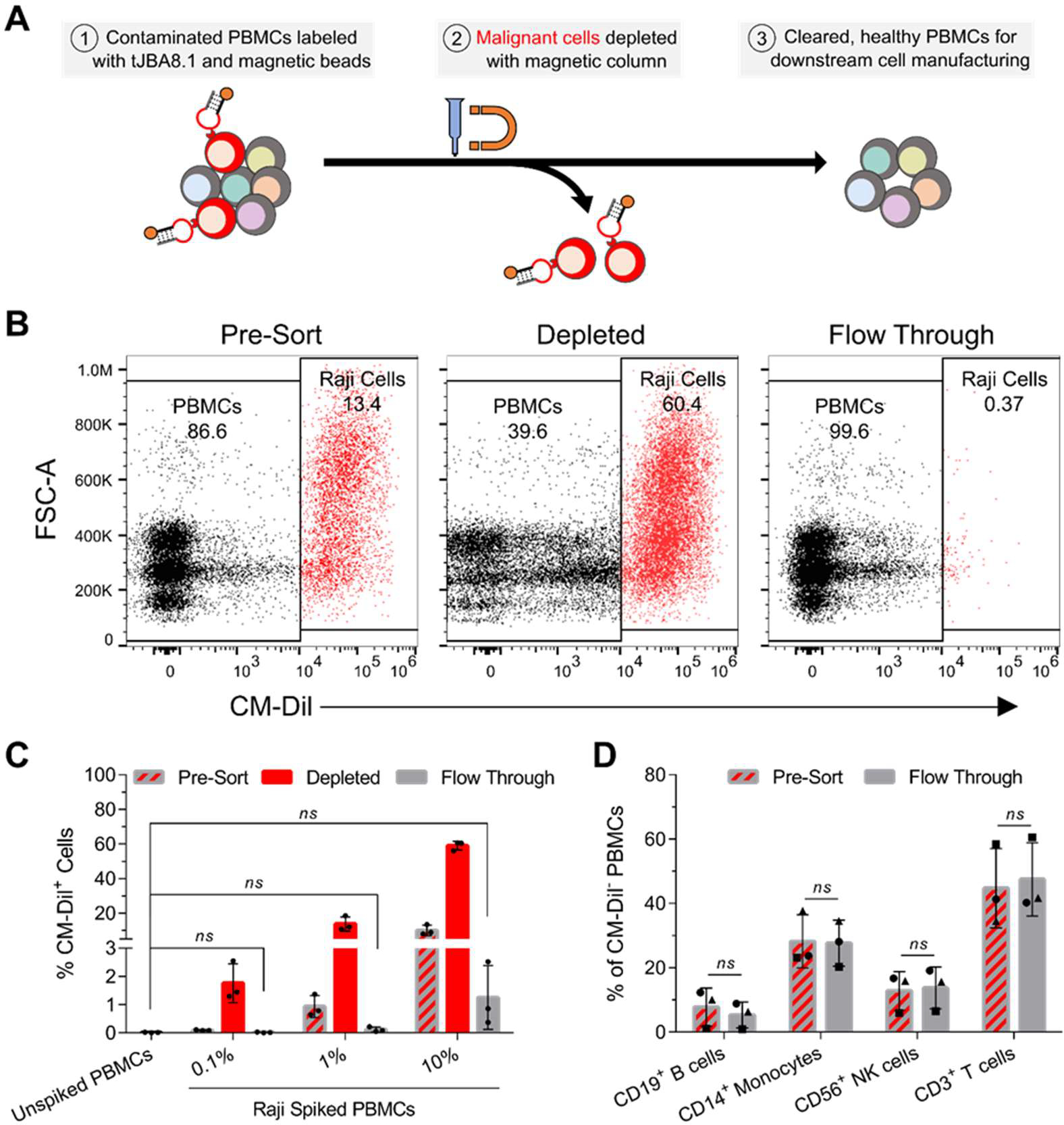

Because TfR1 is overexpressed in many cancer types including leukemias (both lymphocytic and myeloid),56,57 lymphomas,58,59 and myelomas,39 and the level of TfR1 expression marks the proliferative potential of these malignant cells,60 we recognized that tJBA8.1 might be utilized as a malignant cell depletion agent in CAR T-cell manufacturing. We therefore developed a MACS-based approach combining biotinylated tJBA8.1 and Anti-Biotin Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for selective depletion of cancerous cells from PBMCs (Figure 6A, top). We used immortalized Raji B-lymphoma cells, which robustly express TfR1 in contrast to healthy PBMCs (Figure S10A,B), to mimic cancers currently treated by FDA-approved CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapies. Raji cells were pre-labeled with a CM-Dil membrane dye (Figure S11A) and spiked into healthy PBMCs at low (~0.1%), medium (~1%), and high (~10%) percentages to reproduce circulating malignant cell heterogeneity found in patient leukapheresis populations.61 We incubated the mixed cells sequentially with biotinylated tJBA8.1 and anti-biotin beads before separating them on a magnetic column. The pre-sort, depleted, and flow through fractions were analyzed by flow cytometry to detect CM-Dil+ Raji cells (Figure 6B and Figure S11B,C). We observed that tJBA8.1-mediated depletion effectively removed CM-Dil+ Raji cells from all spiked PBMC populations, with flow-through populations that were statistically indistinguishable from un-spiked PBMC controls (Figure 6C). Analyzing the depleted fractions, we detected enrichment of CM-Dil+ Raji cells, as expected, although their purity scaled with the amount of spike cells and never peaked past 60%. As this indicates some CM-Dil− PBMCs were depleted as well, we further examined the percentages of immune cells in the CM-Dil− pre-sort and flow through fractions to determine if the PBMC composition was being impacted by the depletion process. There were no significant changes in the percentages of CD19+ B cells, CD14+ monocytes, CD56+ NK cells, and CD3+ T cells between the pre-sort and flow through fractions (Figure 6D, Figure S12A,B), suggesting that loss of CM-Dil− PBMCs in the depleted fraction was low and likely non-specific. Taken together, these data demonstrate proof-of-concept removal of TfR1+ malignant cells from PBMCs using tJBA8.1, yielding healthy and uncompromised cell product that can be used in downstream CAR T-cell manufacturing with improved safety.

Figure 6.

tJBA8.1 thoroughly depletes Raji B-lymphoma cells from PBMCs without altering healthy immune cell composition. (A) Schematic of malignant cell depletion from PBMCs using tJBA8.1-mediated MACS. (B) Flow cytometry plots of CM-Dil+ Raji cell depletion from high (10%) Raji spiked PBMCs. The different cell fractions from the depletion process are shown. Plots for low (0.1%) and medium (1%) Raji spiked PBMCs can be found in Figure S11B,C. Plots are representative of n = 3 independent experiments with different PBMC donors. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of CM-Dil+ Raji cells in each cell fraction of the depletion process using low (0.1%), medium (1%), and high (10%) Raji spiked PBMCs. Unspiked PBMCs were included as a benchmark of complete depletion. Graph bars and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments with different PBMC donors. ns > 0.05 (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction). (D) Flow cytometry analysis of the healthy immune cell composition within CM-Dil− PBMCs before (pre-sort) and after (flow through) Raji depletion from high (10%) Raji spiked PBMCs. Analysis for low (0.1%) and medium (1%) Raji spiked PBMCs can be found in Figure S12A,B. The circles, squares and triangles represent different PBMC donors from separate depletion studies. Graph bars and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments with different PBMC donors. ns > 0.05 (paired two-way ANOVA with Šídák correction). CM-Dil, chloromethylbenzamido-1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate.

tJBA8.1 Affinity Optimization.

We lastly revisited the NGS results to identify alternative Motif 3 aptamers that could have improved affinity for TfR1. Besides JBA8.1, there were three other aptamers belonging to Motif 3 in the top 50 sequences of the round 8 cell-SELEX pool, namely JBA8.10, JBA8.26, and JBA8.45 (Table S3). Notably, all three aptamers were single-point variants of JBA8.1 that displayed approximately 20-fold enrichment in round 8, which was significantly greater than the 6.9-fold round 8 enrichment for JBA8.1. We selected JBA8.26 for further characterization because it had the highest fold enrichment of the three aptamers. Analyzing the predicted MFE secondary structure of JBA8.26 by NUPACK, we noticed that JBA8.26 has an extended stem region compared to JBA8.1, owing to a T55C mutation (T43C mutation in tJBA8.1) that induces complementary base pairing (Figure S13A). We theorized that these predicted changes would increase the structural stability of JBA8.26 relative to JBA8.1, which may elevate its binding affinity for TfR1. Confirming this, JBA8.26 bound TfR1hi H9 T-lymphoma cells with an apparent KD of 3.3 ± 0.6 nM, a near 8-fold improvement compared to tJBA8.1’s apparent KD of 25.6 ± 13.0 nM for these cells (Figure S13B). Using BLI, JBA8.26 was found to bind immobilized TfR1 with a KD of 6.87 ± 0.04 nM (Figure S13C), displaying both a 2-fold faster association rate and a nearly 2-fold slower dissociation rate than those of tJBA8.1 (Table S6). Given these upgraded TfR1-binding kinetics, we predict that JBA8.26 and its future truncations will increase the partitioning efficiency of our cancer cell depletion strategy.

DISCUSSION

As expensive living drugs, CAR T cells require stringent manufacturing to maximize their safety and efficacy. In rare cases with T-cell isolation approaches currently employed in commercial therapies, malignant cells advance through the isolation process and contaminate enriched T cells, which can inadvertently exhaust produced CAR T cells or even create a cancer resistant to therapy.14,15 Accordingly, an inexpensive approach that actively removes cancerous cells from patient PBMCs while leaving healthy T cells untouched would be of high value to CAR T-cell manufacturing and safety.

Here, we report the discovery of a nanomolar-affinity DNA aptamer, named tJBA8.1, that binds the iron importer TfR1 overexpressed by cancer cells but not expressed by healthy PBMCs. In proof-of-concept MACS-based depletion studies, tJBA8.1 was capable of efficiently removing Raji B-lymphoma cells spiked into PBMCs at various concentrations, yielding uncontaminated, label-free PBMCs. Importantly, the composition of healthy immune cells was unaltered by the depletion steps, showing the precise partitioning afforded by tJBA8.1. This work provides a straightforward, cost-effective approach for selectively removing malignant cells before CAR T-cell production, enabling safer and more reproducible manufacturing of this precious therapy.

Comprehensive validation and detailed characterization of aptamer binding to their cognate receptors is a necessary step to their widespread recognition and use, especially within the context of other ligands. tJBA8.1 binding to TfR1+ cells was competed off by iron-bearing transferrin, and structure solution of the tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex using cryo-EM and subsequent analysis of the tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface verified that tJBA8.1 has a binding epitope in the TfR1 helical domain that overlaps with that of the transferrin Clobe.50 Additionally, the tJBA8.1 binding site on TfR1 appears to coincide with that of HFE, another natural TfR1 ligand that is co-expressed on the cell surface.

We also demonstrated that tJBA8.1 does not bind mouse TfR1 despite the protein sharing ~75% identity in its extracellular domain with human TfR1. Mouse TfR1 has mutations at two of the ten residues bound by tJBA8.1, specifically Arg623 and Arg629 that are instead lysine residues (Figure S14). Our cryo-EM density-guided modeling of the tJBA8.1-TfR1 interface demonstrated that Arg623 and Arg629 form extensive hydrogen bonds and salt bridges with the guanine bases and thymine phosphate groups of tJBA8.1. Compared to arginine residues that have guanidine side chains, lysine residues have a lower propensity for hydrogen bonding with DNA bases, especially with guanines,62 and they also electrostatically bind to phosphate with lower affinity due to not having multivalent hydrogen bonding,63 providing a plausible mechanism for the lack of tJBA8.1 binding to mouse TfR1. Also of potential interest to tJBA8.1 binding is TfR2, a hepatic-localized homolog of TfR1 that shares ~47% identity in its extracellular domain with TfR1.64 TfR2 has even less conservation of the TfR1 interface with tJBA8.1, with mutations at Arg623 that is instead a glycine, Gln627 that is instead a glutamic acid, Arg629 that is instead a serine, and Phe650 that is instead an isoleucine (Figure S15). Given these large changes, we predict that tJBA8.1 would not bind or have severely reduced affinity for TfR2.

tJBA8.1 is not the first TfR1-binding DNA aptamer to be reported—XQ-2d is a 56-nt, human TfR1-binding aptamer previously discovered by the Tan group.65,66 Similar to tJBA8.1, XQ-2d competes with transferrin for TfR1 binding; however, molecular dynamics simulation of the XQ-2d binding site on TfR1 predicts that XQ-2d binds slightly upstream of tJBA8.1 at TfR1 residues Ser638, Gln640, Lys673, Tyr683, Pro688, Tyr689, Ser691, Lys693, Ala736, Trp740, Asn747, Val753, Trp754, and Asn758.66 As Gln640 is the only shared TfR1 residue predicted to be bound by both aptamers, comparison of tJBA8.1 and XQ-2d binding properties and competition assays will be critical to ascertain if tJBA8.1 and XQ-2d share an overlapping binding epitope on TfR1. In addition to XQ-2d, the Levy and Shangguan groups have respectively reported a 42-nt 2’-fluoro RNA aptamer called c2.min and a 35-nt DNA aptamer called HG1-9 that both also compete with transferrin for binding to human TfR1.67–69 Given that tJBA8.1 and these other human TfR1-binding aptamers all have unique sequences, understanding the molecular basis by which TfR1 is commonly targeted by these different aptamers may identify protein traits that are amenable to aptamer binding and even help screen protein targets for SELEX.

Besides TfR1, we speculate that tJBA8.1 has other target receptors on Jurkat cells. Aptamer binding to these cells was only partially abrogated by large molar excesses of holo-transferrin despite cryo-EM mapping showing they have highly overlapping binding epitopes on TfR1. As tJBA8.1 binding is only reduced by ~50% under these conditions, it is likely that tJBA8.1 has a TfR1-independent binding component to Jurkat cells. Compellingly, none of the other Jurkat-binding aptamers identified from the cell-SELEX have appreciable binding to TfR1, suggesting they bind other cellular proteins that may be the same targets of tJBA8.1 TfR1-independent binding. A sequence comparison of these aptamers reveals multiple motifs of two or more consecutive guanine bases. This G-rich patterning may suggest that JBA8.1 and some of the other aptamers identified from the SELEX have a propensity for forming intramolecular or intermolecular G-quadruplexes,70 which may allow the aptamers to bind a number of different target proteins.71 Supporting this, our modeling of TfR1-bound tJBA8.1 found a stabilizing G-quartet motif within its structure and metal ions coordinating bases, which together are the building blocks of G-quadruplexes.

While we showed efficient tJBA8.1-mediated depletion of malignant cells, our studies were conducted using an idealized model of immortalized cell lines and healthy donor PBMCs. TfR1 expression on patient-derived malignant cells may not be as robust as on ex vivo cultured cancer cells, and expression will vary with cancer type, disease stage, and patient history. Validating that tJBA8.1 binds to malignant cells within an array of patient samples will thus be imperative to this system’s translation, and the aptamer affinity improvements detailed at the end of this study (JBA8.26) will be important for increasing the depletion system’s sensitivity to lower levels of TfR1 expression. Also unexplored in this study is the effect of malignant cell depletion on CAR T-cell differentiation, exhaustion, and expansion during manufacturing. Early expression of differentiation and exhaustion markers on CAR T cells prior to patient infusion is associated with remission induction failure,72 and poor CAR T-cell expansion can prevent reaching target doses needed for therapy.73 Removing malignant cell contamination prior to CAR T-cell manufacturing is expected to prevent uncontrolled differentiation and exhaustion of CAR T cells ex vivo and thus improve their expansion.

While we used B-lymphoma cells in our depletion studies to mimic cancers currently treated by commercial CAR T-cell therapies, we anticipate the depletion strategy described here will have a greater impact on the treatment of T-cell malignancies. Presently, autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing for treating T-cell leukemias and lymphomas is impractical since malignant T cells are often found in the peripheral blood of patients with these diseases and immunoaffinity purification approaches that target common T-cell antigens are unable to distinguish normal T cells from these malignant T cells.18,19 To circumvent these challenges, CAR NK cells or allogeneic CAR T cells can be used for treatment,74,75 but the former is difficult to manufacture at a clinical scale whereas the latter requires gene editing to prevent fatal graft-versus-host-disease and likely has limited persistence due to host-versus-graft effects. For these reasons, CAR T-cell manufacturing for T-cell malignancies would serve to benefit the most from the depletion strategy developed here, as it would allow selective harvesting of healthy autologous T cells that are otherwise unattainable. Furthermore, as T-lineage leukemias and lymphomas have been shown to have greater TfR1 expression and positivity than B-lineage counterparts,57,59 these cancers should be especially amenable to tJBA8.1 recognition and capture.

In the future, the aptamer-based malignant cell depletion strategy described here could be adapted to affinity chromatography approaches, eliminating cell processing steps associated with MACS. Chemical conjugation of aptamers to chromatography solid supports will also realize a fully synthetic, low-cost cell depletion system, unlike the anti-biotin coupling used here that relies on expensive antibodies. As contaminating myeloid cells also inhibit the production of CAR T cells,76 tJBA8.1 could be applied in combination with our reported monocyte-binding aptamer to deplete malignant cells and monocytes from patient PBMC concentrates in a single processing step.77 Besides cell isolation, we fore-see other applications of tJBA8.1 within CAR T-cell manufacturing. Our group previously used cationic comb polymers and polymer-lytic peptide conjugates (VIPER) for nonviral gene delivery to T cells, and low uptake was one of the limiting barriers to activated T-cell transfection.78,79 Of relevance, we show in this work that activated T cells have upregulated TfR1 expression and high tJBA8.1 binding, and TfR1 is well known to be rapidly internalized upon ligand binding via clathrin-mediated endocytosis.40 Comb polymer and VIPER formulations could thus be decorated with tJBA8.1 to enhance their binding to activated T cells via TfR1, improving their uptake for T-cell transfection. Outside of CAR T-cell therapy, TfR1 targeting with tJBA8.1 could have implications in the detection of circulating tumor cells and the delivery of drugs across the blood-brain barrier,80,81 paving the way for tJBA8.1-based diagnostics and therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a sponsored research agreement from Juno Therapeutics, a Bristol-Myers Squibb company, and by the NIH (U54CA199090, R01AG063845). Ian Cardle was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1762114 and by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. 5T32CA080416-19. Amédée des Georges was supported by NIH Grant No. R35GM133598 during his contributions to this research. We thank Dr. Chris Ramsborg, Dr. Allison Bianchi, Dr. Julie Shi, and Calvin Chan from Juno Therapeutics for their valuable discussion and suggestions. We acknowledge support from the NIH under Grant No. S10 OD016240 to the W. M. Keck Microscopy Center that originally funded the Leica SP8X confocal microscope used in our studies, and we thank Keck Center manager Dr. Nathaniel Peters for his assistance. We are also grateful to Dr. Philip Gafken and Lisa Jones from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for preparing and processing our mass spectrometry samples. We lastly thank the Imaging Facility of the CUNY Advanced Science Research Center for cryo-EM instrument use as well as scientific and technical assistance.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Michael Jensen has interests in Umoja Biopharma and Juno Therapeutics, a Bristol-Myers Squibb company. Michael Jensen is a seed investor and holds ownership equity in Umoja, serves as a member of the Umoja Joint Steering Committee, and is a Board Observer of the Umoja Board of Directors. Michael Jensen holds patents, some of which are licensed to Umoja Biopharma and Juno Therapeutics. Suzie Pun, Nataly Kacherovsky, Emmeline Cheng, Ian Cardle, and Michael Jensen are co-inventors on a provisional patent application for the aptamers and cell depletion strategy described in this article.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental Section, Tables S1–S8, Figures S1–S15, and Movies S1–S2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the main findings of this research are available in the Article and Supporting Information. All source data generated for this research and relevant information are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. The cryo-EM density map of tJBA8.1 binding to TfR1 has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession code EMD-14874. The atomic coordinates for the refined tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex with tJBA8.1 de novo built into the cryo-EM density have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 7ZQS.

REFERENCES

- (1).Maude SL; Laetsch TW; Buechner J; Rives S; Boyer M; Bittencourt H; Bader P; Verneris MR; Stefanski HE; Myers GD; Qayed M; De Moerloose B; Hiramatsu H; Schlis K; Davis KL; Martin PL; Nemecek ER; Yanik GA; Peters C; Baruchel A; Boissel N; Mechinaud F; Balduzzi A; Krueger J; June CH; Levine BL; Wood P; Taran T; Leung M; Mueller KT; Zhang Y; Sen K; Lebwohl D; Pulsipher MA; Grupp SA Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378 (5), 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schuster SJ; Bishop MR; Tam CS; Waller EK; Borchmann P; McGuirk JP; Jäger U; Jaglowski S; Andreadis C; Westin JR; Fleury I; Bachanova V; Foley SR; Ho PJ; Mielke S; Magenau JM; Holte H; Pantano S; Pacaud LB; Awasthi R; Chu J; Anak Ö; Salles G; Maziarz RT Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 380 (1), 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Neelapu SS; Locke FL; Bartlett NL; Lekakis LJ; Miklos DB; Jacobson CA; Braunschweig I; Oluwole OO; Siddiqi T; Lin Y; Timmerman JM; Stiff PJ; Friedberg JW; Flinn IW; Goy A; Hill BT; Smith MR; Deol A; Farooq U; McSweeney P; Munoz J; Avivi I; Castro JE; Westin JR; Chavez JC; Ghobadi A; Komanduri KV; Levy R; Jacobsen ED; Witzig TE; Reagan P; Bot A; Rossi J; Navale L; Jiang Y; Aycock J; Elias M; Chang D; Wiezorek J; Go WY Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377 (26), 2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Locke FL; Ghobadi A; Jacobson CA; Miklos DB; Lekakis LJ; Oluwole OO; Lin Y; Braunschweig I; Hill BT; Timmerman JM; Deol A; Reagan PM; Stiff P; Flinn IW; Farooq U; Goy A; McSweeney PA; Munoz J; Siddiqi T; Chavez JC; Herrera AF; Bartlett NL; Wiezorek JS; Navale L; Xue A; Jiang Y; Bot A; Rossi JM; Kim JJ; Go WY; Neelapu SS Long-Term Safety and Activity of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma (ZUMA-1): A Single-Arm, Multicentre, Phase 1–2 Trial. The Lancet Oncology 2019, 20 (1), 31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wang M; Munoz J; Goy A; Locke FL; Jacobson CA; Hill BT; Timmerman JM; Holmes H; Jaglowski S; Flinn IW; McSweeney PA; Miklos DB; Pagel JM; Kersten M-J; Milpied N; Fung H; Topp MS; Houot R; Beitinjaneh A; Peng W; Zheng L; Rossi JM; Jain RK; Rao AV; Reagan PM KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382 (14), 1331–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Abramson JS; Palomba ML; Gordon LI; Lunning MA; Wang M; Arnason J; Mehta A; Purev E; Maloney DG; Andreadis C; Sehgal A; Solomon SR; Ghosh N; Albertson TM; Garcia J; Kostic A; Mallaney M; Ogasawara K; Newhall K; Kim Y; Li D; Siddiqi T Lisocabtagene Maraleucel for Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): A Multicentre Seamless Design Study. The Lancet 2020, 396 (10254), 839–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Munshi NC; Anderson LD; Shah N; Madduri D; Berdeja J; Lonial S; Raje N; Lin Y; Siegel D; Oriol A; Moreau P; Yakoub-Agha I; Delforge M; Cavo M; Einsele H; Goldschmidt H; Weisel K; Rambaldi A; Reece D; Petrocca F; Massaro M; Connarn JN; Kaiser S; Patel P; Huang L; Campbell TB; Hege K; San-Miguel J Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384 (8), 705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Berdeja JG; Madduri D; Usmani SZ; Jakubowiak A; Agha M; Cohen AD; Stewart AK; Hari P; Htut M; Lesokhin A; Deol A; Munshi NC; O’Donnell E; Avigan D; Singh I; Zudaire E; Yeh T-M; Allred AJ; Olyslager Y; Banerjee A; Jackson CC; Goldberg JD; Schecter JM; Deraedt W; Zhuang SH; Infante J; Geng D; Wu X; Carrasco-Alfonso MJ; Akram M; Hossain F; Rizvi S; Fan F; Lin Y; Martin T; Jagannath S Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel, a B-Cell Maturation Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): A Phase 1b/2 Open-Label Study. The Lancet 2021, 398 (10297), 314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Vormittag P; Gunn R; Ghorashian S; Veraitch FS A Guide to Manufacturing CAR T Cell Therapies. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2018, 53, 164–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cardle II; Cheng EL; Jensen MC; Pun SH Biomaterials in Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Process Development. Accounts of Chemical Research 2020, 53 (9), 1724–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Powell DJ; Brennan AL; Zheng Z; Huynh H; Cotte J; Levine BL Efficient Clinical-Scale Enrichment of Lymphocytes for Use in Adoptive Immunotherapy Using a Modified Counterflow Centrifugal Elutriation Program. Cytotherapy 2009, 11 (7), 923–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Maude SL; Frey N; Shaw PA; Aplenc R; Barrett DM; Bunin NJ; Chew A; Gonzalez VE; Zheng Z; Lacey SF; Mahnke YD; Melenhorst JJ; Rheingold SR; Shen A; Teachey DT; Levine BL; June CH; Porter DL; Grupp SA Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371 (16), 1507–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Iyer RK; Bowles PA; Kim H; Dulgar-Tulloch A Industrializing Autologous Adoptive Immunotherapies: Manufacturing Advances and Challenges. Frontiers in Medicine 2018, 5, 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hoffmann J-M; Schubert M-L; Wang L; Hückelhoven A; Sellner L; Stock S; Schmitt A; Kleist C; Gern U; Loskog A; Wuchter P; Hofmann S; Ho AD; Müller-Tidow C; Dreger P; Schmitt M Differences in Expansion Potential of Naive Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells from Healthy Donors and Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 8, 1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ruella M; Xu J; Barrett DM; Fraietta JA; Reich TJ; Ambrose DE; Klichinsky M; Shestova O; Patel PR; Kulikovskaya I; Nazimuddin F; Bhoj VG; Orlando EJ; Fry TJ; Bitter H; Maude SL; Levine BL; Nobles CL; Bushman FD; Young RM; Scholler J; Gill SI; June CH; Grupp SA; Lacey SF; Melenhorst JJ Induction of Resistance to Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy by Transduction of a Single Leukemic B Cell. Nature Medicine 2018, 24 (10), 1499–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jie X; Li-Juan C; Shuang-Shuang Y; Yan S; Wen W; Yuan-Fang L; Ji X; Yan Z; Wu Z; Xiang-Qin W; Jing W; Yan W; Jin W; Hua Y; Wen-Bin X; Hua J; Juan D; Xiao-Yi D; Biao L; Jun-Min L; Wei-Jun F; Jiang Z; Li Z; Zhu C; Frank FX-H; Jian H; Jian-Yong L; Jian-Qing M; Sai-Juan C Exploratory Trial of a Biepitopic CAR T-Targeting B Cell Maturation Antigen in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116 (19), 9543–9551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Miltenyi S; Müller W; Weichel W; Radbruch A High Gradient Magnetic Cell Separation with MACS. Cytometry 1990, 11 (2), 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Alcantara M; Tesio M; June CH; Houot R CAR T-Cells for T-Cell Malignancies: Challenges in Distinguishing between Therapeutic, Normal, and Neoplastic T-Cells. Leukemia 2018, 32 (11), 2307–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fleischer LC; Spencer HT; Raikar SS Targeting T Cell Malignancies Using CAR-Based Immunotherapy: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2019, 12 (1), 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhou J; Rossi J Aptamers as Targeted Therapeutics: Current Potential and Challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (6), 440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang Z; Chen N; Li S; Battig MR; Wang Y Programmable Hydrogels for Controlled Cell Catch and Release Using Hybridized Aptamers and Complementary Sequences. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134 (38), 15716–15719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Rusconi CP; Scardino E; Layzer J; Pitoc GA; Ortel TL; Monroe D; Sullenger BA RNA Aptamers as Reversible Antagonists of Coagulation Factor IXa. Nature 2002, 419, 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kacherovsky N; Cardle II; Cheng EL; Yu JL; Baldwin ML; Salipante SJ; Jensen MC; Pun SH Traceless Aptamer-Mediated Isolation of CD8+ T Cells for Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2019, 3 (10), 783–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Robertson DL; Joyce GF Selection in Vitro of an RNA Enzyme That Specifically Cleaves Single-Stranded DNA. Nature 1990, 344, 467–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Tuerk C; Gold L Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, 249 (4968), 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ellington AD; Szostak JW In Vitro Selection of RNA Molecules That Bind Specific Ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sefah K; Shangguan D; Xiong X; O’Donoghue MB; Tan W Development of DNA Aptamers Using Cell-Selex. Nature Protocols 2010, 5, 1169–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Weiss A; Stobo JD Requirement for the Coexpression of T3 and the T Cell Antigen Receptor on a Malignant Human T Cell Line. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1984, 160 (5), 1284–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Alam KK; Chang JL; Burke DH FASTAptamer: A Bioinformatic Toolkit for High-Throughput Sequence Analysis of Combinatorial Selections. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2015, 4 (3), e230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Rambaut A FigTree-version 1.4. 3, a graphical viewer of phylogenetic trees. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree (accessed 2021-03-03).

- (31).Bailey TL; Boden M; Buske FA; Frith M; Grant CE; Clementi L; Ren J; Li WW; Noble WS MEME Suite: Tools for Motif Discovery and Searching. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, W202–W208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Gold L; Ayers D; Bertino J; Bock C; Bock A; Brody EN; Carter J; Dalby AB; Eaton BE; Fitzwater T; Flather D; Forbes A; Foreman T; Fowler C; Gawande B; Goss M; Gunn M; Gupta S; Halladay D; Heil J; Heilig J; Hicke B; Husar G; Janjic N; Jarvis T; Jennings S; Katilius E; Keeney TR; Kim N; Koch TH; Kraemer S; Kroiss L; Le N; Levine D; Lindsey W; Lollo B; Mayfield W; Mehan M; Mehler R; Nelson SK; Nelson M; Nieuwlandt D; Nikrad M; Ochsner U; Ostroff RM; Otis M; Parker T; Pietrasiewicz S; Resnicow DI; Rohloff J; Sanders G; Sattin S; Schneider D; Singer B; Stanton M; Sterkel A; Stewart A; Stratford S; Vaught JD; Vrkljan M; Walker JJ; Watrobka M; Waugh S; Weiss A; Wilcox SK; Wolfson A; Wolk SK; Zhang C; Zichi D Aptamer-Based Multiplexed Proteomic Technology for Biomarker Discovery. PLOS ONE 2010, 5 (12), e15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zadeh JN; Steenberg CD; Bois JS; Wolfe BR; Pierce MB; Khan AR; Dirks RM; Pierce NA NUPACK: Analysis and Design of Nucleic Acid Systems. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2011, 32 (1), 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Shangguan D; Cao Z; Meng L; Mallikaratchy P; Sefah K; Wang H; Li Y; Tan W Cell-Specific Aptamer Probes for Membrane Protein Elucidation in Cancer Cells. Journal of Proteome Research 2008, 7 (5), 2133–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Montemiglio LC; Testi C; Ceci P; Falvo E; Pitea M; Savino C; Arcovito A; Peruzzi G; Baiocco P; Mancia F; Boffi A; des Georges A; Vallone B Cryo-EM Structure of the Human Ferritin–Transferrin Receptor 1 Complex. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tortorella S; Karagiannis TC Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis: A Useful Target for Cancer Therapy. Journal of Membrane Biology 2014, 247, 291–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gatter KC; Brown G; Trowbridge IS; Woolston RE; Mason DY Transferrin Receptors in Human Tissues: Their Distribution and Possible Clinical Relevance. Journal of Clinical Pathology 1983, 36 (5), 539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Caruso A; Licenziati S; Corulli M; Canaris AD; De Francesco MA; Fiorentini S; Peroni L; Fallacara F; Dima F; Balsari A; Turano A Flow Cytometric Analysis of Activation Markers on Stimulated T Cells and Their Correlation with Cell Proliferation. Cytometry 1997, 27, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Yeh C-JG; Taylor CG; Faulka WP Transferrin Binding by Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in Human Lymphomas, Myelomas and Leukemias. Vox Sanguinis 1984, 46 (4), 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Mayle KM; Le AM; Kamei DT The Intracellular Trafficking Pathway of Transferrin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2012, 1820 (3), 264–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Boumsell L; Bensussan A; Kadouche J Anti-CD71 Monoclonal Antibodies and Uses Thereof for Treating Malignant Tumor Cells. US 8,409,573 B2, April 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lawrence CM; Ray S; Babyonyshev M; Galluser R; Borhani DW; Harrison SC Crystal Structure of the Ectodomain of Human Transferrin Receptor. Science 1999, 286 (5440), 779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lee J-H; Jucker F; Pardi A Imino Proton Exchange Rates Imply an Induced-Fit Binding Mechanism for the VEGF165-Targeting Aptamer, Macugen. FEBS Letters 2008, 582 (13), 1835–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Davlieva M; Donarski J; Wang J; Shamoo Y; Nikonowicz EP Structure Analysis of Free and Bound States of an RNA Aptamer against Ribosomal Protein S8 from Bacillus Anthracis. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42 (16), 10795–10808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Gelinas AD; Davies DR; Janjic N Embracing Proteins: Structural Themes in Aptamer–Protein Complexes. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2016, 36, 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chu B; Zhang D; Paukstelis PJ A DNA G-Quadruplex/i-Motif Hybrid. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47 (22), 11921–11930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Krissinel E; Henrick K Inference of Macromolecular Assemblies from Crystalline State. Journal of Molecular Biology 2007, 372 (3), 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Adasme MF; Linnemann KL; Bolz SN; Kaiser F; Salentin S; Haupt VJ; Schroeder M PLIP 2021: Expanding the Scope of the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49 (W1), W530–W534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Luscombe NM; Laskowski RA; Thornton JM NUCPLOT: A Program to Generate Schematic Diagrams of Protein-Nucleic Acid Interactions. Nucleic Acids Research 1997, 25 (24), 4940–4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Cheng Y; Zak O; Aisen P; Harrison SC; Walz T Structure of the Human Transferrin Receptor-Transferrin Complex. Cell 2004, 116 (4), 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bennett MJ; Lebrón JA; Bjorkman PJ Crystal Structure of the Hereditary Haemochromatosis Protein HFE Complexed with Transferrin Receptor. Nature 2000, 403, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Feder JN; Penny DM; Irrinki A; Lee VK; Lebrón JA; Watson N; Tsuchihashi Z; Sigal E; Bjorkman PJ; Schatzman RC The Hemochromatosis Gene Product Complexes with the Transferrin Receptor and Lowers Its Affinity for Ligand Binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95 (4), 1472–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Waheed A; Grubb JH; Zhou XY; Tomatsu S; Fleming RE; Costaldi ME; Britton RS; Bacon BR; Sly WS Regulation of Transferrin-Mediated Iron Uptake by HFE, the Protein Defective in Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99 (5), 3117–3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Feder JN; Gnirke A; Thomas W; Tsuchihashi Z; Ruddy DA; Basava A; Dormishian F; Domingo R; Ellis MC; Fullan A; Hinton LM; Jones NL; Kimmel BE; Kronmal GS; Lauer P; Lee VK; Loeb DB; Mapa FA; McClelland E; Meyer NC; Mintier GA; Moeller N; Moore T; Morikang E; Prass CE; Quintana L; Starnes SM; Schatzman RC; Brunke KJ; Drayna DT; Risch NJ; Bacon BR; Wolff RK A Novel MHC Class I–like Gene Is Mutated in Patients with Hereditary Haemochromatosis. Nature Genetics 1996, 13 (4), 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Schmidt PJ; Toran PT; Giannetti AM; Bjorkman PJ; Andrews NC The Transferrin Receptor Modulates Hfe-Dependent Regulation of Hepcidin Expression. Cell Metabolism 2008, 7 (3), 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Scott CS; Ramsden W; Limbert HJ; Master PS; Roberts BE Membrane Transferrin Receptor (TfR) and Nuclear Proliferation-Associated Ki-67 Expression in Hemopoietic Malignancies. Leukemia 1988, 2 (7), 438–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Płoszyńska A; Ruckemann-Dziurdzińska K; Jóźwik A; Mikosik A; Lisowska K; Balcerska A; Witkowski JM Cytometric Evaluation of Transferrin Receptor 1 (CD71) in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica 2012, 50 (2), 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Habeshaw JA; Lister TA; Stansfeld AG; Greaves MF Correlation of Transferrin Receptor Expression with Histological Class and Outcome in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. The Lancet 1983, 321 (8323), 498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).das Gupta A; Shah VI Correlation of Transferrin Receptor Expression with Histologic Grade and Immunophenotype in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Hematologic Pathology 1990, 4 (1), 37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kozlowski R; Reilly IAG; Sowter D; Robins RA; Russell NH Transferrin Receptor Expression on AML Blasts Is Related to Their Proliferative Potential. British Journal of Haematology 1988, 69 (2), 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Allen ES; Stroncek DF; Ren J; Eder AF; West KA; Fry TJ; Lee DW; Mackall CL; Conry-Cantilena C Autologous Lymphapheresis for the Production of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Transfusion 2017, 57 (5), 1133–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Luscombe NM; Laskowski RA; Thornton JM Amino Acid–Base Interactions: A Three-Dimensional Analysis of Protein–DNA Interactions at an Atomic Level. Nucleic Acids Research 2001, 29 (13), 2860–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Schug KA; Lindner W Noncovalent Binding between Guanidinium and Anionic Groups: Focus on Biological- and Synthetic-Based Arginine/Guanidinium Interactions with Phosph[on]Ate and Sulf[on]Ate Residues. Chemical Reviews 2005, 105 (1), 67–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Worthen C; Enns C The Role of Hepatic Transferrin Receptor 2 in the Regulation of Iron Homeostasis in the Body. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2014, 5, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Wu X; Zhao Z; Bai H; Fu T; Yang C; Hu X; Liu Q; Champanhac C; Teng I-T; Ye M; Tan W DNA Aptamer Selected against Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma for In Vivo Imaging and Clinical Tissue Recognition. Theranostics 2015, 5 (9), 985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Wu X; Liu H; Han D; Peng B; Zhang H; Zhang L; Li J; Liu J; Cui C; Fang S; Li M; Ye M; Tan W Elucidation and Structural Modeling of CD71 as a Molecular Target for Cell-Specific Aptamer Binding. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141 (27), 10760–10769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Wilner SE; Wengerter B; Maier K; de Lourdes Borba Magalhães M; del Amo DS; Pai S; Opazo F; Rizzoli SO; Yan A; Levy M An RNA Alternative to Human Transferrin: A New Tool for Targeting Human Cells. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Zhang N; Bing T; Shen L; Feng L; Liu X; Shangguan D A DNA Aptameric Ligand of Human Transferrin Receptor Generated by Cell-SELEX. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22 (16), 8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Zhang N; Wang J; Bing T; Liu X; Shangguan D Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Internalization and Intracellular Fate of Conjugates of a DNA Aptamer. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 1249–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kikin O; D’Antonio L; Bagga PS QGRS Mapper: A Web-Based Server for Predicting G-Quadruplexes in Nucleotide Sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34 (suppl_2), W676–W682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Roxo C; Kotkowiak W; Pasternak A G-Quadruplex-Forming Aptamers—Characteristics, Applications, and Perspectives. Molecules 2019, 24 (20), 3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Finney OC; Brakke H; Rawlings-Rhea S; Hicks R; Doolittle D; Lopez M; Futrell B; Orentas RJ; Li D; Gardner R; Jensen MC CD19 CAR T Cell Product and Disease Attributes Predict Leukemia Remission Durability. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2019, 129 (5), 2123–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Bersenev A CAR-T Cell Manufacturing: Time to Put It in Gear. Transfusion 2017, 57 (5), 1104–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Cooper ML; Choi J; Staser K; Ritchey JK; Devenport JM; Eckardt K; Rettig MP; Wang B; Eissenberg LG; Ghobadi A; Gehrs LN; Prior JL; Achilefu S; Miller CA; Fronick CC; O’Neal J; Gao F; Weinstock DM; Gutierrez A; Fulton RS; DiPersio JF An “off-the-Shelf” Fratricide-Resistant CAR-T for the Treatment of T Cell Hematologic Malignancies. Leukemia 2018, 32 (9), 1970–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Xu Y; Liu Q; Zhong M; Wang Z; Chen Z; Zhang Y; Xing H; Tian Z; Tang K; Liao X; Rao Q; Wang M; Wang J 2B4 Costimulatory Domain Enhancing Cytotoxic Ability of Anti-CD5 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Engineered Natural Killer Cells against T Cell Malignancies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2019, 12 (1), 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Stroncek DF; Ren J; Lee DW; Tran M; Frodigh SE; Sabatino M; Khuu H; Merchant MS; Mackall CL Myeloid Cells in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Concentrates Inhibit the Expansion of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Cytotherapy 2016, 18 (7), 893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Sylvestre M; Saxby CP; Kacherovsky N; Gustafson H; Salipante SJ; Pun SH Identification of a DNA Aptamer That Binds to Human Monocytes and Macrophages. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2020, 31 (8), 1899–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Olden BR; Cheng Y; Yu JL; Pun SH Cationic Polymers for Non-Viral Gene Delivery to Human T Cells. Journal of Controlled Release 2018, 282, 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Olden BR; Cheng E; Cheng Y; Pun SH Identifying Key Barriers in Cationic Polymer Gene Delivery to Human T Cells. Biomaterials Science 2019, 7 (3), 789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Biglione C; Bergueiro J; Asadian-Birjand M; Weise C; Khobragade V; Chate G; Dongare M; Khandare J; Strumia MC; Calderón M Optimizing Circulating Tumor Cells’ Capture Efficiency of Magnetic Nanogels by Transferrin Decoration. Polymers 2018, 10 (2), 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Li X; Yang Y; Zhao H; Zhu T; Yang Z; Xu H; Fu Y; Lin F; Pan X; Li L; Cui C; Hong M; Yang L; Wang KK; Tan W Enhanced in Vivo Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration by Circular Tau–Transferrin Receptor Bifunctional Aptamer for Tauopathy Therapy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2020, 142 (8), 3862–3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the main findings of this research are available in the Article and Supporting Information. All source data generated for this research and relevant information are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. The cryo-EM density map of tJBA8.1 binding to TfR1 has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession code EMD-14874. The atomic coordinates for the refined tJBA8.1-TfR1 complex with tJBA8.1 de novo built into the cryo-EM density have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 7ZQS.