Summary

Evidence linking coding germline variants in breast cancer (BC)-susceptibility genes other than BRCA1, BRCA2, and CHEK2 with contralateral breast cancer (CBC) risk and breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) is scarce. The aim of this study was to assess the association of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) and rare missense variants (MSVs) in nine known (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53) and 25 suspected BC-susceptibility genes with CBC risk and BCSS. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated with Cox regression models. Analyses included 34,401 women of European ancestry diagnosed with BC, including 676 CBCs and 3,449 BC deaths; the median follow-up was 10.9 years. Subtype analyses were based on estrogen receptor (ER) status of the first BC. Combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 and PTVs in CHEK2 and PALB2 were associated with increased CBC risk [HRs (95% CIs): 2.88 (1.70–4.87), 2.31 (1.39–3.85), 8.29 (2.53–27.21), 2.25 (1.55–3.27), and 2.67 (1.33–5.35), respectively]. The strongest evidence of association with BCSS was for PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA2 (ER-positive BC) and TP53 and PTVs in CHEK2 [HRs (95% CIs): 1.53 (1.13–2.07), 2.08 (0.95–4.57), and 1.39 (1.13–1.72), respectively, after adjusting for tumor characteristics and treatment]. HRs were essentially unchanged when censoring for CBC, suggesting that these associations are not completely explained by increased CBC risk, tumor characteristics, or treatment. There was limited evidence of associations of PTVs and/or rare MSVs with CBC risk or BCSS for the 25 suspected BC genes. The CBC findings are relevant to treatment decisions, follow-up, and screening after BC diagnosis.

Keywords: coding germline variants, breast cancer susceptibility genes, contralateral breast cancer risk, survival

Protein-truncating and/or (likely) pathogenic missense variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, and TP53 were associated with 2- to 8-fold higher risk of contralateral breast cancer. Associations with breast cancer-specific survival were generally weaker. These findings are relevant to treatment decisions, follow-up, and screening after breast cancer diagnosis.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC [MIM: 114480])-susceptibility genes may modulate BC prognosis. Studies of unselected young women diagnosed with invasive breast tumors showed worse survival for BRCA1/2 (BRCA1 [MIM: 113705]; BRCA2 [MIM: 600185]) mutation carriers compared with non-carriers.1,2 On the other hand, a large meta-analysis concluded that differences in breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) by carrier status in the adjuvant setting are likely to be small.3 Poorer prognosis has also been reported in carriers of the CHEK2 (MIM: 604373) c.1100delC variant4,5,6 (GenBank: NM_007194.4) (p.Thr367fs∗15) and of some pathogenic PALB27,8 (MIM: 610355) variants. Evidence linking other putative BC-risk genes with prognosis is scarce.

Germline genetic variants could affect prognosis by predisposing to an aggressive BC subtype, by impairing BC treatment response, or by increasing the risk of a second primary BC.1,9,10,11,12,13 These variants could also influence immune responses to the tumor.14,15,16,17 Recently, a large study,18 BRIDGES, investigated coding germline genetic variants in a panel of 34 genes, providing strong evidence for association with nine of these genes with risk of developing a first primary BC. Using the BRIDGES data, we mainly aimed to investigate the association of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) and rare missense variants (MSVs) in the nine known BC-susceptibility genes (ATM [MIM: 607585], BARD1 [MIM: 601593], BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C [MIM: 602774], RAD51D [MIM: 602954], and TP53 [MIM: 191170]) with BCSS and with risk of developing a contralateral breast cancer (CBC). Our secondary goal was to evaluate the evidence of associations of PTVs and rare MSVs with CBC risk and BCSS in the remaining 25 suspected BC-risk genes on the BRIDGES panel.

Material and methods

Study sample

We selected women of European ancestry from studies participating in the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC). In particular, ancestry was defined on the basis of array genotype data if available,19 or self-reported. Women were included if diagnosed with a primary invasive BC without known distant metastases, were between 18 and 79 years of age (median: 56; interquartile range [IQR]: 48–64) in the period 1942–2018 (median: 2003; IQR: 1999–2006), and had available information on vital status and number of years from diagnosis to last follow-up. Our final study sample consisted of 34,401 women from 34 BCAC studies (Tables S1, S2, and S3): 28 population or hospital-based and six family or clinical genetic center based.

Information on tumor characteristics, pathology, CBC, survival, and treatment was collected by individual studies, pooled, and harmonized (BCAC database: version 13, November 2020). The BCAC database did not include information about preventive contralateral mastectomy and oophorectomy.

All studies were approved by the pertinent ethics committees and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Sequencing and variant classification

DNA of participants was collected through the individual studies and collated for panel sequencing. Laboratory methods, including calling and classification of PTVs and MSVs, have been described elsewhere.18

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by gene, for PTVs in aggregate and rare MSVs (allele frequency < 0.001)18 in aggregate. More specifically, individual study subjects were considered as carriers of PTVs in a given gene if they carried at least one PTV in that given gene. The same was done for rare MSVs. Carriers of PTVs in a given gene were excluded from the analyses of rare MSVs of that specific gene. In addition, MSVs in aggregate in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 determined to be likely pathogenic, as previously described,18 were also analyzed (supplemental methods). For BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs were combined with PTVs in the analyses. This was done in consideration of the previous evidence that pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have similar BC risk as PTVs,18 while MSVs in TP53 are well established to contribute to risk.20

Missing values in clinical and pathological variables related to the first BC (Table S4) were imputed with the MICE R package (v.3.13.0). Details are provided in the supplemental methods and Table S5.

The primary outcomes were time to development of a CBC and BCSS (time to death due to BC). Overall survival (time to death due to any cause) analyses were performed as sensitivity analyses because several genes on the BRIDGES panel are associated with different cancers or other diseases.18

We used delayed-entry Cox regression models stratified by country to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and we performed them by using the R package “survival.”21,22 Standard errors of the HR estimates were re-computed on the basis of the likelihood ratio test statistic.23

CBC risk analyses were based on women with known CBC status and, for women who developed a CBC, time from diagnosis of the first BC to CBC. In particular, women with missing time from first BC to CBC diagnosis (43 out of the 1,523 CBCs reported in Table S4), women diagnosed with a CBC within 3 months after diagnosis of the first BC (492 out of 1,523), and women who developed a CBC before study entry (312 out of 1,523) were excluded from the CBC risk analyses. All CBCs were considered, including invasive (70.7%), in situ (10.9%), and those with unknown invasive versus in situ status (18.3%). For these analyses, time at risk started either at 3 months after the diagnosis of the first BC or at study entry if study entry was more than 3 months after the diagnosis of the first BC and ended at time of CBC, death, or last follow-up, whichever came first.

For BCSS and overall survival analyses, time-to-event started at diagnosis of the first BC and ended at time of death or last follow-up; time at risk started at study entry if this was after diagnosis of a first BC. For BCSS analyses, women who died from unknown cause or cause other than BC were censored at time of death or otherwise at last follow-up. Additional BCSS analyses were performed where women diagnosed with a CBC were censored at time of CBC diagnosis. Women known to have developed a CBC before study entry were excluded from the main survival analyses.

Main CBC risk and BCSS analyses were also performed by estrogen receptor (ER) status of the first BC. Subtype analyses included only women with non-missing ER status. Heterogeneity of HR estimates by ER status was tested, as explained in the supplemental methods.

In addition to the unadjusted analyses, comparing carriers to non-carriers of PTVS or rare MSVs in a given gene, adjusted analyses were performed including age at diagnosis and characteristics of the first BC and systemic treatment as covariates. In particular, systemic treatment was defined as having received endocrine therapy, any kind, (yes versus no), trastuzumab (yes versus no), and neo-adjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy (yes versus no). The aim of the adjusted analyses was to assess to what extent the impact of PTVs or rare MSVs in a given gene on CBC risk and survival could be explained through other established prognostic factors. We performed these analyses on imputed covariates to keep the same sample size.

For each gene, the set of non-carriers included women who did not carry any of the identified PTVs or rare MSVs for that specific gene, irrespective of whether they were carriers of a PTV or rare MSV in any other gene. For CBC risk, sensitivity analyses were performed restricting the set of non-carriers to those women who did not carry PTVs in any of the nine main BC-susceptibility genes or pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs for BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53. Since early age at onset has been shown to influence CBC risk in BRCA1/2 and TP53 carriers,24,25,26 unadjusted CBC risk analyses were performed separately for combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 within subgroups of women diagnosed with first BC at age younger than 40 years and at age equal to or older than 40 years. Heterogeneity of HR estimates by age at onset of first BC was tested as explained in the supplemental methods.

Additional sensitivity analyses were performed with data from cohort, population-based, and hospital-based studies, excluding studies that selected women with family history of BC or women from studies that partially selected individuals with family history of BC (Table S1).

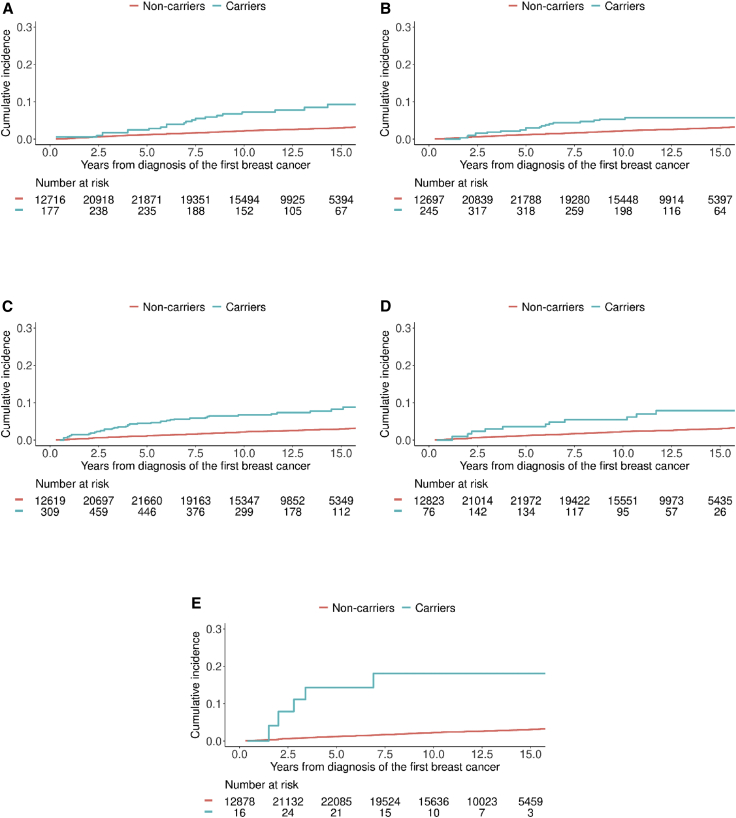

CBC cumulative incidence estimates for the nine known BC-susceptibility genes, allowing for competing risk of death (Figures 2 and S1), were computed as specified in the supplemental methods. Kaplan-Meier curves for BCSS are shown in Figure S2.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence curves for developing contralateral breast cancer in the presence of competing risk of death for any cause

(A–E) Cumulative incidence for carriers (blue line) and non-carriers (red line) of combined protein-truncating variants (PTVs) and pathogenic/likely pathogenic missense variants (MSVs) in BRCA1 (A), combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely MSVs in BRCA2 (B), PTVs in CHEK2 (C), PTVs in PALB2 (D), and combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in TP53 (E). PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs as defined in Dorling et al.18 were considered. We limited the y axis to the range (0.00, 0.30) to better visualize the curves. The x axis is restricted to 15 years from diagnosis because of the low number of carriers after 15 years.

Given the prior evidence that PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare MSVs in the nine main BC-susceptibility genes increase BC risk,18 and therefore their hypothesized impact on disease outcome through increased risk of CBC or recurrence, results of analyses were considered statistically significant at a nominal level of p < 0.05. For the secondary analyses of the 25 other genes, a Bonferroni corrected threshold of 0.05/25 = 0.002 was used.

Results

Characteristics of the 34 Breast Cancer Association Consortium studies and 34,401 women included in these analyses are shown in Tables S1, S2, and S3. Over a median follow-up of 10.9 years, there were 6,898 deaths, of which 3,449 were known BC deaths.

Contralateral breast cancer risk

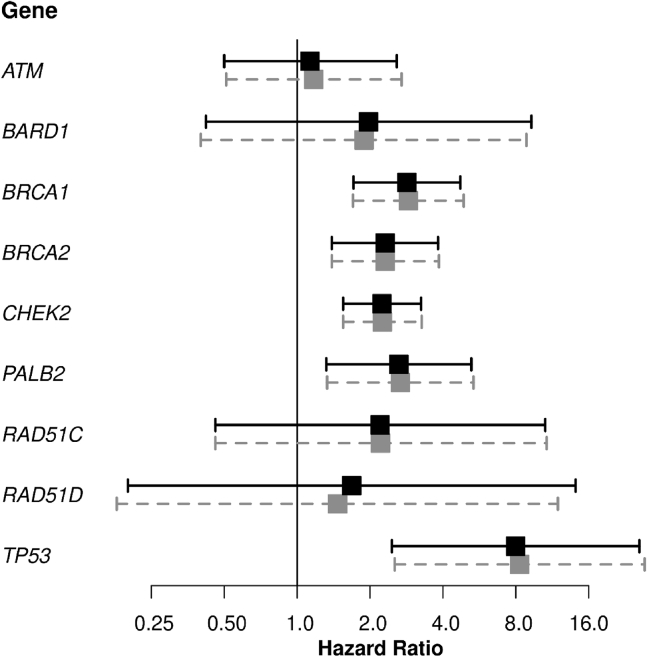

CBC risk analyses were based on 30,628 women with information on CBC diagnoses. Of 676 CBCs, 103 were diagnosed among carriers of variants in at least one of the nine BC-susceptibility genes, namely of PTVs in ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, TP53, and/or pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 (Table S6). HRs and 95% CIs for the association of PTVs in the nine main BC genes and of likely pathogenic rare MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic with CBC risk are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Only analyses adjusted by tumor characteristics, age at diagnosis of the first BC, and systemic treatment are reported in the text, unless differently specified. Carriers of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1 had a nearly 3-fold increased CBC risk compared to non-carriers [HR (95% CI): 2.88 (1.70–4.87), p = 8.8E−05]. Carriers of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA2 had a 2-fold increased CBC risk compared to non-carriers [HR (95% CI): 2.31 (1.39–3.85), p = 1.3E−03]. The association was more evident within women diagnosed with an ER-negative for BRCA1 and an ER-positive first BC for BRCA2 (Tables S7 and S8), although the heterogeneity tests were not significant (Table S9). For combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in TP53, there was evidence of strong association with CBC risk although the 95% CI was wide [HR (95% CI): 8.29 (2.53–27.21), p = 5.1E−04]. The estimated unadjusted HR (95% CI) for combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 based on women diagnosed with first BC before age 40 years were 3.90 (1.52–10.02), 2.61 (1.00–6.78), and 13.15 (3.18–54.39), respectively, with no strong evidence of heterogeneity by age at first BC diagnosis (p > 1.3E−01). PTVs in CHEK2 were associated with a 2-fold increased CBC risk compared to non-carriers, with no difference in the HR by ER status of the first BC (Table S9). The estimated HR was higher for CHEK2 c.1100delC [HR (95% CI): 2.43 (1.63–3.62), p = 1.5E−05] than for other CHEK2 PTVs, in aggregate [HR (95% CI): 1.40 (0.49–3.96)], but the difference in HR was not statistically significant. There was evidence that rare MSVs in CHEK2, in aggregate, were also associated with an increased risk of CBC [HR (95% CI): 1.78 (1.08–2.94); Table S10], with no evidence of differential association by ER status of the first BC (Tables S11–S13). The estimated adjusted HR (95% CI) for PTVs in PALB2 was 2.67 (1.33–5.35) (Table 1). PTVs in ATM, BARD1, RAD51C, and RAD51D were not statistically significantly associated with CBC risk (Table 1); however, the confidence intervals for HRs in each case included 2, a suggested threshold to define pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants that “could be used to inform medical management.”27

Table 1.

Association of protein-truncating variants in nine breast cancer genes and of pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 with risk of contralateral breast cancer

|

Gene |

Unadjusted analyses |

Adjusted analysesa |

No. of women |

No. of CBC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTVs (unless indicated otherwise) | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | Non-carriers | Carriers | Non-carriers | Carriers | |

| ATM | 1.13 (0.50–2.58) | 7.7E−01 | 1.17 (0.51–2.70) | 7.1E−01 | 30,399 | 229 | 670 | 6 | |

| BARD1 | 1.97 (0.42–9.27) | 3.9E−01 | 1.89 (0.40–8.85) | 4.2E−01 | 30,577 | 51 | 674 | 2 | |

| BRCA1b | 2.84 (1.71–4.72)∗ | 5.7E−05∗ | 2.88 (1.70–4.87)∗ | 8.8E−05∗ | 30,298 | 330 | 655 | 21 | |

| BRCA2b | 2.31 (1.39–3.82)∗ | 1.2E−03∗ | 2.31 (1.39–3.85)∗ | 1.3E−03∗ | 30,208 | 420 | 656 | 20 | |

| CHEK2 | 2.24 (1.55–3.25)∗ | 1.8E−05∗ | 2.25 (1.55–3.27)∗ | 2.2E−05∗ | 29,972 | 656 | 638 | 38 | |

| c.1100delC | 2.42 (1.63–3.59)∗ | 1.2E−05∗ | 2.43 (1.63–3.62)∗ | 1.5E−05∗ | 29,972 | 530 | 638 | 34 | |

| Other | 1.40 (0.49–3.94) | 5.3E−01 | 1.40 (0.49–3.96) | 5.3E−01 | 29,972 | 126 | 638 | 4 | |

| PALB2 | 2.63 (1.32–5.24)∗ | 6.0E−03∗ | 2.67 (1.33–5.35)∗ | 5.6E−03∗ | 30,428 | 200 | 665 | 11 | |

| RAD51C | 2.20 (0.46–10.58) | 3.3E−01 | 2.21 (0.46–10.72) | 3.2E−01 | 30,591 | 37 | 674 | 2 | |

| RAD51D | 1.68 (0.20–14.12) | 6.4E−01 | 1.47 (0.18–11.93) | 7.2E−01 | 30,599 | 29 | 675 | 1 | |

| TP53b | 7.98 (2.46–25.89)∗ | 5.4E−04∗ | 8.29 (2.53–27.21)∗ | 5.1E−04∗ | 30,587 | 41 | 671 | 5 | |

Abbreviations: No., number; CBC, contralateral breast cancer; PTVs, protein-truncating variants; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; p, p value. Analyses included women from 32 studies with information about contralateral breast cancer diagnosis. Statistically significant associations (p < 5E−02) are denoted with an asterisk.

We performed adjusted analyses by including age at diagnosis, nodal status, size category, grade, estrogen receptor (ER) status, ERB-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2 [MIM: 164870]) status of the first breast cancer, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab as covariates in the Cox regression model.

Combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants as defined in Dorling et al. (2021).18

Figure 1.

Forest plot showing the association of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) in ATM, BARD1, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, and RAD51D and of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants (MSVs) in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 with contralateral breast cancer (CBC) risk

The black squares and solid lines represent hazard ratio (HR) estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the unadjusted analyses, respectively. The gray squares and dashed gray lines represent HR estimates and 95% CIs from the adjusted analyses. We performed the adjusted analyses by including age at diagnosis, nodal status, size category, grade, estrogen receptor (ER) status, ERB-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2) status of the first breast cancer, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab as covariates in the Cox regression model. For each gene, the exact numbers of women and CBCs are reported in Table 1. PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs were defined as in Dorling et al.18

Results of sensitivity analyses comparing with women who did not carry PTVs in any of the nine main BC-susceptibility genes nor likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 were consistent with the main analyses (Tables S14 and S15). Sensitivity analyses restricted to cohort, population-based, and hospital-based studies were also consistent (Tables S16 and S17).

The estimated 10-year cumulative incidence of CBC, after allowing for the competing risk of death from any cause, was 7.2% for carriers of PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, 5.4% for carriers of PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA2, 6.7% for PTVs carriers in CHEK2, 5.4% in PTVs carriers in PALB2, and 18.0% in carriers of PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs combined in TP53 (Figure 2).

Among the remaining 25 putative BC-susceptibility genes, there was evidence for association of PTVs in RAD50 (MIM: 604040) [HR (95% CI): 4.75 (1.86–12.15), p = 1.2E−03; Table S18] and MSVs in XRCC2 (MIM: 600375) with CBC risk [HR (95% CI): 4.05 (1.88–8.73), p = 3.8E−04; Table S19], with no evidence of differential association by ER status of the first BC (Tables S20–S25).

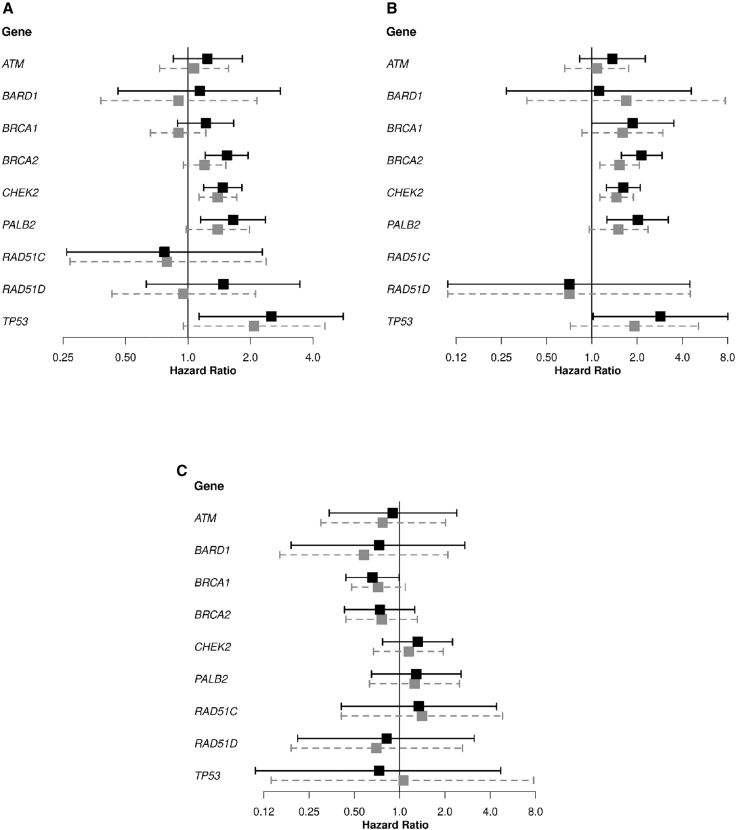

Breast cancer-specific survival

HRs for association of PTVs in ATM, BARD1, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, and RAD51D and of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 with BCSS are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. There was a statistically significant association of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA2 with decreased BCSS in the unadjusted analysis. However, after adjusting for tumor characteristics, age at diagnosis, and systemic treatment given for the first BC, the HR was no longer statistically significant [HR (95% CI): 1.20 (0.95–1.52), p = 1.2E−01]. HRs differed by ER status of the first BC [HR (95% CI): 1.53 (1.13–2.07) and 0.76 (0.44–1.31), for ER-positive and ER-negative first BC, respectively; pheterogeneity = 2.2E−02; Tables S9, S26, and S27]. PTVs in CHEK2 were associated with higher risk of BC death [HR (95% CI): 1.39 (1.13–1.72), p = 2.2E−03] with no strong evidence of heterogeneity in HRs by ER status (Table S9). There was also weak evidence for a poorer BCSS for carriers of rare MSVs in CHEK2 [HR (95% CI): 1.23 (0.97–1.57); Table S28], with no evidence of differential association by ER status of the first BC (Tables S13, S29, and S30). PTVs in PALB2 were associated with poorer BCSS (unadjusted HR = 1.65), but this association was attenuated after adjusting for additional tumor characteristics [HR (95% CI): 1.39 (0.98–1.98), p = 6.8E−02]. There was no evidence for an association between PTVs in ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, RAD51C, and RAD51D and likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1 and BCSS. For TP53 there was weak evidence for poorer BCSS in carriers of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs [HR (95% CI): 2.08 (0.95–4.57), p = 6.8E−02] and of all rare MSVs in aggregate [HR (95% CI): 1.63 (1.11–2.38), p = 1.2E−02; Table S28]. Sensitivity analyses restricted to cohort, population-based, and hospital-based studies were consistent with the main analyses (Tables S31 and S32).

Table 2.

Association of protein-truncating variants in nine breast cancer genes and of pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 with breast cancer-specific survival

|

Gene |

Unadjusted analyses |

Adjusted analysesa |

No. of women |

No. of BC deaths |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTVs (unless indicated otherwise) | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | Non-carriers | Carriers | Non-carriers | Carriers |

| ATM | 1.24 (0.85–1.83) | 2.7E−01 | 1.07 (0.73–1.57) | 7.3E−01 | 34,151 | 250 | 3,421 | 28 |

| BARD1 | 1.14 (0.46–2.79) | 7.8E−01 | 0.90 (0.38–2.15) | 8.2E−01 | 34,347 | 54 | 3,444 | 5 |

| BRCA1b | 1.22 (0.89–1.66) | 2.2E−01 | 0.90 (0.66–1.22) | 4.9E−01 | 34,037 | 364 | 3,406 | 43 |

| BRCA2b | 1.54 (1.21–1.95)∗ | 5.0E−04∗ | 1.20 (0.95–1.52) | 1.2E−01 | 33,914 | 487 | 3,372 | 77 |

| CHEK2 | 1.47 (1.19–1.82)∗ | 3.7E−04∗ | 1.39 (1.13–1.72)∗ | 2.2E−03∗ | 33,702 | 699 | 3,349 | 100 |

| c.1100delC | 1.46 (1.15–1.85)∗ | 1.6E−03∗ | 1.43 (1.13–1.81)∗ | 3.0E−03∗ | 33,702 | 561 | 3,349 | 81 |

| Other | 1.51 (0.93–2.44) | 9.6E−02 | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | 3.4E−01 | 33,702 | 138 | 3,349 | 19 |

| PALB2 | 1.65 (1.15–2.36)∗ | 6.7E−03∗ | 1.39 (0.98–1.98) | 6.8E−02 | 34,177 | 224 | 3,414 | 35 |

| RAD51C | 0.77 (0.26–2.28) | 6.4E−01 | 0.79 (0.27–2.38) | 6.8E−01 | 34,361 | 40 | 3,446 | 3 |

| RAD51D | 1.48 (0.63–3.46) | 3.7E−01 | 0.95 (0.43–2.12) | 9.1E−01 | 34,370 | 31 | 3,443 | 6 |

| TP53b | 2.52 (1.13–5.60)∗ | 2.4E−02∗ | 2.08 (0.95–4.57) | 6.8E−02 | 34,354 | 47 | 3,441 | 8 |

Abbreviations: No., number; BC, breast cancer; PTVs, protein-truncating variants; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; p, p value. Analyses included women from 34 studies listed in Table S1, excluding women who developed a CBC before study entry. Statistically significant associations (p < 5E−02) are denoted with an asterisk.

We performed adjusted analyses by including age at diagnosis, nodal status, size category, grade, estrogen receptor (ER) status ERB-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2) status of the first breast cancer, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab as covariates in the Cox regression model.

Combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants as defined in Dorling et al. (2021).18

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing the association of PTVs in ATM, BARD1, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, and RAD51D and of combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare missense variants (MSVs) in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53, with breast cancer-specific survival, in women from all studies, excluding women who developed a CBC before study entry

(A–C) The results of the analysis shown in Table 2 are shown in (A). The results of the analysis based on women diagnosed with an estrogen receptor (ER)-positive first breast cancer (Table S26) are shown in (B). The hazard ratios (HRs) for the association of PTVs in RAD51C with breast cancer-specific survival could not be estimated because of the low number of carriers and the absence of carriers who died of breast cancer (Table S26). The results of the analysis based on women diagnosed with an estrogen ER-negative first breast cancer (Table S27) are shown in (C). The black squares and solid lines represent hazard ratio (HR) estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the unadjusted analyses, respectively. The gray squares and dashed gray lines represent HR estimates and 95% CIs from the adjusted analyses. Adjusted analyses shown in (A) included age at diagnosis, nodal status, size category, grade, ER status, ERB-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2) status of the first breast cancer, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab as covariates in the Cox regression model. Adjusted analyses in (B) and (C) included the same covariates as in (A) except the ER status of the first breast cancer. PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs were defined as in Dorling et al.18

Of the remaining 25 putative BC-susceptibility genes evaluated, PTVs in BABAM2 (MIM: 610497) were associated with decreased BCSS [Table S33: HR (95% CI): 7.74 (1.67–35.84), p = 8.8E−03], while PTVs in GEN1 (MIM: 612449) and BRIP1 (MIM: 605882) were associated with decreased BCSS in ER-negative tumors [Tables S34 and S35; HR (95% CI): 7.41 (1.99–27.66) and 4.97 (1.42–17.43) for GEN1 and BRIP1, respectively]. However, these associations were not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for 25 tests. MSVs, in aggregate, in the 25 putative BC genes were not associated with BCSS (Tables S36–S38). For genes with evidence of association of PTVs or MSVs with both CBC risk and BCSS, results of the BCSS analyses censored for CBC were broadly similar (Tables S39 and S40).

Overall survival

Results of overall survival analyses are shown in Tables S41 and S42. Combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA2 and PTVs in CHEK2 were associated with poorer overall survival, though the HRs were smaller than for BCSS [Table S41; HRs (95% CIs): 1.27 (1.06–1.52), p = 1.1E−02 and 1.21 (1.03–1.43), p = 2.0E−02, for BRCA2 and CHEK2, respectively]. In TP53, combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs were significantly associated with poorer overall survival [HR (95% CI): 3.47 (1.98–6.09), p = 1.5E−05].

Discussion

Using data from the BRIDGES18 study, we evaluated PTVs and rare MSVs in nine confirmed (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, TP53) and 25 putative BC-susceptibility genes18 for association with CBC risk and BCSS both overall and by ER status of the first BC.

Combined PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 and PTVs in CHEK2 and PALB2 were associated with increased CBC risk. These findings are consistent with recent studies18,28,29 and support the general hypothesis that mutations that predispose to a first BC also predispose to a second BC. Carriers of PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 had approximately a 2- and 3-fold increased CBC risk, respectively, as reported previously.25,30 The larger HR estimates in women with an ER-negative first BC for BRCA1 and in women with ER-positive first BC for BRCA2 probably reflect the fact that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers are most likely to develop ER-negative and ER-positive first BCs, respectively.31 BRCA1 carriers with ER-positive first BC and BRCA2 carriers with ER-negative first BC did not appear to have an increased risk of CBC. However, in both cases there was no evidence of heterogeneity of the HR estimates by ER status of the first BC; therefore, we cannot conclude that surveillance or risk-reduction strategies in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers should differ according to the ER status of the first BC. PTVs in PALB2 were associated with an over 2.5-fold increased CBC risk. HRs for BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2, while clearly elevated, were lower than the relative risk estimates for the first BC. PTVs in CHEK2 were associated with an over 2-fold increased CBC risk, similar to the relative risk for the first BC reported in BRIDGES,18 and to a previous CBC analysis.5 In TP53, PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs combined were associated with an 8-fold increased CBC risk, consistent with the results of a previous study focused on carriers younger than age 36 years at diagnosis of the first BC26 and four times higher than the corresponding risk of first BC,18 although this estimate is imprecise because of the low numbers of carriers.

The similarity of the relative risk estimates for a first BC and a CBC for CHEK2 PTVs are broadly consistent with a model in which the risks of the second cancer are independent of the first, given the individual’s genotype.32 CHEK2 MSVs are also associated in aggregate with BC risk,18 and the increased CBC risk in CHEK2 MSV carriers, although lower than for PTV carriers, is also consistent with this model. On the other hand, the lower relative risks of CBC (in comparison with the first BC) observed for carriers of rare PTVs in PALB2 and of rare PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 could be partly explained by the fact that carriers of high-risk variants20 diagnosed with cancer are more depleted for other risk factors (particularly risk alleles in common susceptibility variants)—a phenomenon known as elimination of susceptibles, or index event bias.33,34 However, other factors, for example differential effects in carriers of endocrine and/or chemotherapy regimens that have been shown to lower CBC risk,35 may also play a role. An additional explanation for the observed lower CBC HR estimates compared to the estimates for the first BC, and lower estimated CBC incidence in carriers of PTVs and/or pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare MSVs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 than what has been previously reported,25,36,37,38 is that some women in our study sample may have undergone prophylactic contralateral mastectomy. Contralateral mastectomy virtually eliminates the risk of developing a CBC, which in turn might affect BCSS because CBC occurrence is associated with poorer prognosis.9,10,11,13 This would result in lower HR (for both CBC risk and BCSS) and CBC incidence estimates: the downward bias is stronger as the proportion of women undergoing contralateral mastectomy increases. Unfortunately, we did not have information on contralateral mastectomy and thus could not account for it in the analyses; therefore, the HR could be a lower bound to the true estimate. On the other hand, within our study population, genetic testing was mostly carried out in the research setting (BRIDGES panel) retrospectively (long) after women were diagnosed and treated. Therefore, most of the women included in the analyses would not have been aware that they carried pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and TP53, either before or at the time of diagnosis. Moreover, most of study individuals are part of population- and hospital-based studies and without family history. This could also partly explain the lower CBC incidence in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers compared with previous reports.25,36,37,38 Assuming that mainly women known to be carriers of pathogenic variants in either BRCA1/2 or TP53 or women with known family history (from family or clinical genetic center-based studies) underwent a contralateral mastectomy, these would be a minor part of our study population and we do not expect their inclusion to substantially affect the results. Although the past decade has seen an increase in the number of women opting for a contralateral mastectomy without knowing their mutation status,39,40,41,42 to the best of our knowledge most of this increase has been in North America. Most of our study population comes from European countries and only includes two USA studies and one study from Canada, which amounts to approximately 7% of the total study population. Again, it is unlikely that inclusion of this small percentage would substantially affect the results.

PTVs in ATM, BARD1, RAD51C, and RAD51D were not associated with statistically significantly increased CBC risk; however, HRs estimates were >1 in each case, confidence limits were wide, and the HRs were mostly consistent with the relative risk estimates for a first BC. An earlier study also reported no significantly elevated risk for pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in ATM.43

Risk of BC-specific death was increased in carriers of PTVs in CHEK2 and PALB2, and of PTVs/MSVs in BRCA2 and TP53; these associations were not substantially altered by censoring for CBC. For BRCA2, the stronger increase in risk of BC death observed in women with an ER-positive BC compared to women with an ER-negative BC is consistent with the results of a previous study.44 The association with BCSS of BRCA2 PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in women with ER-positive cancers, and of CHEK2 PTVs and TP53 MSVs in overall BC, although attenuated, remained significant after adjusting for age at diagnosis and tumor characteristics, suggesting that part of the effect is not explained by less favorable tumor characteristics or systemic treatment given for the first BC. The observed association between PTV carriers in PALB2 and BCSS was attenuated and not statistically significant in the adjusted analyses, suggesting that most of the effect might be mediated by tumor characteristics or treatment. Consistent with the fact that PTVs/MSVs in TP53 are associated with a spectrum of cancers, the HR for association with overall survival was larger than for BCSS. Interestingly, PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare MSVs in BRCA1 were not associated with BCSS, in spite of the fact that BRCA1 carriers are more likely to develop ER-negative tumors,31 which are known to lead to a higher risk of short term recurrence and mortality.45 This lack of association might still be due to chance, since the upper 95% confidence limit on the unadjusted HR (1.66) is still consistent with an important survival difference. We speculate that the lack of association of PTVs and pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare MSVs in BRCA1 with BCSS in our study might be explained by the fact that BRCA1 carriers have a better response to systemic treatment for the first BC, in particular chemotherapy.46

Analyses of the 25 remaining putative BC-susceptibility genes showed some evidence of association between CBC risk, PTVs in RAD50, and MSVs in XRCC2 and between BCSS and PTVs in BABAM2 (in BC overall), GEN1, and BRIP1 (ER-negative subtype), although the latter three analyses had limited power and Bonferroni-corrected p values for 25 tests were not statistically significant. A potential role of XRCC2 polymorphisms47 and germline PTVs in RAD5048 in BC prognosis have been reported. Previous evidence supporting a role of germline PTVs or rare MSVs in BABAM2 and GEN1 in BC prognosis is lacking, while PTVs/potentially damaging rare MSVs in BRIP1 have been reported to be associated with ovarian cancer (MIM: 167000),49 which could explain the observed poorer survival of carriers in our study.

The main strength of this study is its large sample size and long follow-up, which allowed us to provide estimates for the association between PTVs and rare MSVs in BC-susceptibility genes with CBC risk and BCSS by gene. This is relevant because data on prognosis for individual genes apart from BRCA1, BRCA2, and CHEK2 have been limited. The inclusion of studies that selected women with family history of BC improved power but could bias the association estimates. However, sensitivity analyses restricted to women without family history of BC yielded results in line with those from the main analyses. As previously mentioned, most of the studies included in our study sample were either population- or hospital-based and therefore most women did not have family history. Some genes, such as TP53, are related to rare multi-cancer syndromes and usually detected at genetic centers and excluded from population-based studies, making unbiased estimation difficult. Another limitation was the fact that for 22% of the deaths observed during follow-up, cause of death was unknown, reducing the power to detect associations with BCSS. Similarly, CBC information may have been incomplete for some studies, and therefore some of our estimates might be slightly underestimated. Despite the large sample size, variants in some of the genes are so rare that their association with CBC risk and survival could not be estimated. The statistical power to detect significant interactions by ER status and age at diagnosis of the first BC was also limited. Moreover, there was insufficient data to carry out analyses based on tumor characteristics of the CBC. Finally, only women of European ancestry were included in the analyses. Larger studies, including those drawing upon women with different ethnicities, are necessary to provide precise and reliable estimates of CBC and BCSS in populations worldwide.

In conclusion, PTVs and/or rare pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in five BC-susceptibility genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, and TP53) are associated with increased CBC risk; PTVs and/or rare pathogenic/likely pathogenic MSVs in three of these genes (BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53) are associated with poorer BCSS, not completely explained by the increased CBC risk, tumor characteristics, or treatment. There is limited evidence of associations for other putative BC-susceptibility genes. Our results have the potential to improve BC-risk counseling, prognostic estimates, and prediction models for BC outcome. In particular, the CBC findings are relevant to improve treatment, follow-up, and screening of women diagnosed with BC.

Consortia

The NBCS Collaborators are Kristine K. Sahlberg, Anne-Lise Børresen-Dale, Inger Torhild Gram, Karina Standahl Olsen, Olav Engebråten, Bjørn Naume, Jürgen Geisler, OSBREAC, and Grethe I. Grenaker Alnæs. Contact email: greal@ous-hf.no.

The kConFab Investigators are David Amor, Lesley Andrews, Yoland Antill, Rosemary Balleine, Jonathan Beesley, Ian Bennett, Michael Bogwitz, Leon Botes, Meagan Brennan, Melissa Brown, Michael Buckley, Jo Burke, Phyllis Butow, Liz Caldon, Ian Campbell, Michelle Cao, Anannya Chakrabarti, Deepa Chauhan, Manisha Chauhan, Georgia Chenevix-Trench, Alice Christian, Paul Cohen, Alison Colley, Ashley Crook, James Cui, Eliza Courtney, Margaret Cummings, Sarah-Jane Dawson, Anna DeFazio, Martin Delatycki, Rebecca Dickson, Joanne Dixon, Ted Edkins, Stacey Edwards, Gelareh Farshid, Andrew Fellows, Georgina Fenton, Michael Field, James Flanagan, Peter Fong, Laura Forrest, Stephen Fox, Juliet French, Michael Friedlander, Clara Gaff, Mike Gattas, Peter George, Sian Greening, Marion Harris, Stewart Hart, Nick Hayward, John Hopper, Cass Hoskins, Clare Hunt, Paul James, Mark Jenkins, Alexa Kidd, Judy Kirk, Jessica Koehler, James Kollias, Sunil Lakhani, Mitchell Lawrence, Jason Lee, Shuai Li, Geoff Lindeman, Lara Lipton, Liz Lobb, Sherene Loi, Graham Mann, Deborah Marsh, Sue Anne McLachlan, Bettina Meiser, Roger Milne, Sophie Nightingale, Shona O'Connell, Sarah O'Sullivan, David Gallego Ortega, Nick Pachter, Jia-Min Pang, Gargi Pathak, Briony Patterson, Amy Pearn, Kelly Phillips, Ellen Pieper, Susan Ramus, Edwina Rickard, Bridget Robinson, Mona Saleh, Anita Skandarajah, Elizabeth Salisbury, Christobel Saunders, Jodi Saunus, Rodney Scott, Clare Scott, Adrienne Sexton, Andrew Shelling, Peter Simpson, Melissa Southey, Amanda Spurdle, Jessica Taylor, Renea Taylor, Heather Thorne, Alison Trainer, Kathy Tucker, Jane Visvader, Logan Walker, Rachael Williams, Ingrid Winship, Mary Ann Young, and Milita Zaheed. Contact email: heather.thorne@petermac.org.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conception and design: A.M., N.M., T.A.M., H.N., P.D., D.F.E., and M.K.S. Administrative support: M.K.B., J.W., and R.K. Provision of study materials or patients: all authors. Collection and assembly of data: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: A.M., N.M., T.A.M., H.N., P.D., D.F.E., and M.K.S. Manuscript writing: all authors; initial draft: A.M. and M.K.S.; final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Declaration of interests

B.D. is a stockholder of Roche, Vaccitech and EQRx. P.A.F. conducts research funded by Amgen, Novartis, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. He received honoraria from Roche, Novartis, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. D.F.E. is an associate editor at The American Journal of Human Genetics (AJHG).

Published: February 23, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.02.003.

Contributor Information

Anna Morra, Email: a.morra@nki.nl.

Marjanka K. Schmidt, Email: mk.schmidt@nki.nl.

NBCS Collaborators:

Kristine K. Sahlberg, Anne-Lise Børresen-Dale, Inger Torhild Gram, Karina Standahl Olsen, Olav Engebråten, Bjørn Naume, Jürgen Geisler, OSBREAC, and Grethe I. Grenaker Alnæs

kConFab Investigators:

David Amor, Lesley Andrews, Yoland Antill, Rosemary Balleine, Jonathan Beesley, Ian Bennett, Michael Bogwitz, Leon Botes, Meagan Brennan, Melissa Brown, Michael Buckley, Jo Burke, Phyllis Butow, Liz Caldon, Ian Campbell, Michelle Cao, Anannya Chakrabarti, Deepa Chauhan, Manisha Chauhan, Georgia Chenevix-Trench, Alice Christian, Paul Cohen, Alison Colley, Ashley Crook, James Cui, Eliza Courtney, Margaret Cummings, Sarah-Jane Dawson, Anna DeFazio, Martin Delatycki, Rebecca Dickson, Joanne Dixon, Ted Edkins, Stacey Edwards, Gelareh Farshid, Andrew Fellows, Georgina Fenton, Michael Field, James Flanagan, Peter Fong, Laura Forrest, Stephen Fox, Juliet French, Michael Friedlander, Clara Gaff, Mike Gattas, Peter George, Sian Greening, Marion Harris, Stewart Hart, Nick Hayward, John Hopper, Cass Hoskins, Clare Hunt, Paul James, Mark Jenkins, Alexa Kidd, Judy Kirk, Jessica Koehler, James Kollias, Sunil Lakhani, Mitchell Lawrence, Jason Lee, Shuai Li, Geoff Lindeman, Lara Lipton, Liz Lobb, Sherene Loi, Graham Mann, Deborah Marsh, Sue Anne McLachlan, Bettina Meiser, Roger Milne, Sophie Nightingale, Shona O'Connell, Sarah O'Sullivan, David Gallego Ortega, Nick Pachter, Jia-Min Pang, Gargi Pathak, Briony Patterson, Amy Pearn, Kelly Phillips, Ellen Pieper, Susan Ramus, Edwina Rickard, Bridget Robinson, Mona Saleh, Anita Skandarajah, Elizabeth Salisbury, Christobel Saunders, Jodi Saunus, Rodney Scott, Clare Scott, Adrienne Sexton, Andrew Shelling, Peter Simpson, Melissa Southey, Amanda Spurdle, Jessica Taylor, Renea Taylor, Heather Thorne, Alison Trainer, Kathy Tucker, Jane Visvader, Logan Walker, Rachael Williams, Ingrid Winship, Mary Ann Young, and Milita Zaheed

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Schmidt M.K., van den Broek A.J., Tollenaar R.A.E.M., Smit V.T.H.B.M., Westenend P.J., Brinkhuis M., Oosterhuis W.J.W., Wesseling J., Janssen-Heijnen M.L., Jobsen J.J., et al. Breast Cancer Survival of BRCA1/BRCA2 Mutation Carriers in a Hospital-Based Cohort of Young Women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copson E.R., Maishman T.C., Tapper W.J., Cutress R.I., Greville-Heygate S., Altman D.G., Eccles B., Gerty S., Durcan L.T., Jones L., et al. Germline BRCA mutation and outcome in young-onset breast cancer (POSH): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Broek A.J., Schmidt M.K., van 't Veer L.J., Tollenaar R.A.E.M., van Leeuwen F.E. Worse breast cancer prognosis of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: what's the evidence? A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt M.K., Tollenaar R.A.E.M., de Kemp S.R., Broeks A., Cornelisse C.J., Smit V.T.H.B.M., Peterse J.L., van Leeuwen F.E., Van't Veer L.J. Breast Cancer Survival and Tumor Characteristics in Premenopausal Women Carrying the CHEK2∗1100delC Germline Mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:64–69. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.06.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weischer M., Nordestgaard B.G., Pharoah P., Bolla M.K., Nevanlinna H., Van't Veer L.J., Garcia-Closas M., Hopper J.L., Hall P., Andrulis I.L., et al. CHEK2∗1100delC heterozygosity in women with breast cancer associated with early death, breast cancer–specific death, and increased risk of a second breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:4308–4316. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.42.7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer A., Dörk T., Sohn C., Karstens J.H., Bremer M. Breast cancer in patients carrying a germ-line CHEK2 mutation: Outcome after breast conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2007;82:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heikkinen T., Kärkkäinen H., Aaltonen K., Milne R.L., Heikkilä P., Aittomäki K., Blomqvist C., Nevanlinna H. The breast cancer susceptibility mutation PALB2 1592delT is associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3214–3222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-08-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cybulski C., Kluźniak W., Huzarski T., Wokołorczyk D., Kashyap A., Jakubowska A., Szwiec M., Byrski T., Dębniak T., Górski B., et al. Clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:638–644. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heron D.E., Komarnicky L.T., Hyslop T., Schwartz G.F., Mansfield C.M. Bilateral breast carcinoma: risk factors and outcomes for patients with synchronous and metachronous disease. Cancer. 2000;88:2739–2750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollias J., Ellis I.O., Elston C.W., Blamey R.W. Prognostic significance of synchronous and metachronous bilateral breast cancer. World J. Surg. 2001;25:1117–1124. doi: 10.1007/BF03215857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartman M., Czene K., Reilly M., Adolfsson J., Bergh J., Adami H.O., Dickman P.W., Hall P. Incidence and prognosis of synchronous and metachronous bilateral breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:4210–4216. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.10.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vichapat V., Garmo H., Holmberg L., Fentiman I.S., Tutt A., Gillett C., Lüchtenborg M. Prognosis of metachronous contralateral breast cancer: importance of stage, age and interval time between the two diagnoses. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;130:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liederbach E., Wang C.H., Lutfi W., Kantor O., Pesce C., Winchester D.J., Yao K. Survival outcomes and pathologic features among breast cancer patients who have developed a contralateral breast cancer. Ann. Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S412–S421. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segovia-Mendoza M., Morales-Montor J. Immune tumor microenvironment in breast cancer and the participation of estrogen and its receptors in cancer physiopathology. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatti-Mays M.E., Balko J.M., Gameiro S.R., Bear H.D., Prabhakaran S., Fukui J., Disis M.L., Nanda R., Gulley J.L., Kalinsky K., et al. If we build it they will come: targeting the immune response to breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer. 2019;5:37. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxevanis C.N., Fortis S.P., Perez S.A. The balance between breast cancer and the immune system: Challenges for prognosis and clinical benefit from immunotherapies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;72:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goff S.L., Danforth D.N. The role of immune cells in breast tissue and immunotherapy for the treatment of breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2021;21:e63–e73. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Dorling L., Carvalho S., Allen J., González-Neira A., Luccarini C., Wahlström C., Pooley K.A., Parsons M.T., Fortuno C., et al. Breast cancer risk genes - association analysis in more than 113,000 women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:428–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michailidou K., Lindström S., Dennis J., Beesley J., Hui S., Kar S., Lemaçon A., Soucy P., Glubb D., Rostamianfar A., et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551:92–94. doi: 10.1038/nature24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Easton D.F., Pharoah P.D.P., Antoniou A.C., Tischkowitz M., Tavtigian S.V., Nathanson K.L., Devilee P., Meindl A., Couch F.J., Southey M., et al. Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2243–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1501341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therneau T.M. 2021. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. R package version 3.2-13.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survivalhttps://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therneau T.M., Grambsch P.M. 1 Edition. Springer; 2000. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escala-Garcia M., Guo Q., Dörk T., Canisius S., Keeman R., Dennis J., Beesley J., Lecarpentier J., Bolla M.K., Wang Q., et al. Genome-wide association study of germline variants and breast cancer-specific mortality. Br. J. Cancer. 2019;120:647–657. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graeser M.K., Engel C., Rhiem K., Gadzicki D., Bick U., Kast K., Froster U.G., Schlehe B., Bechtold A., Arnold N., et al. Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5887–5892. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.19.9430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Broek A.J., van 't Veer L.J., Hooning M.J., Cornelissen S., Broeks A., Rutgers E.J., Smit V.T.H.B.M., Cornelisse C.J., van Beek M., Janssen-Heijnen M.L., et al. Impact of age at primary breast cancer on contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:409–418. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.62.3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyder Z., Harkness E.F., Woodward E.R., Bowers N.L., Pereira M., Wallace A.J., Howell S.J., Howell A., Lalloo F., Newman W.G., et al. Risk of contralateral breast cancer in women with and without pathogenic variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 genes in women with very early-onset (<36 Years) breast cancer. Cancers. 2020;12:378. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spurdle A.B., Greville-Heygate S., Antoniou A.C., Brown M., Burke L., de la Hoya M., Domchek S., Dörk T., Firth H.V., Monteiro A.N., et al. Towards controlled terminology for reporting germline cancer susceptibility variants: an ENIGMA report. J. Med. Genet. 2019;56:347–357. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu C., Polley E.C., Yadav S., Lilyquist J., Shimelis H., Na J., Hart S.N., Goldgar D.E., Shah S., Pesaran T., et al. The contribution of germline predisposition gene mutations to clinical subtypes of invasive breast cancer from a clinical genetic testing cohort. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020;112:1231–1241. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu C., Hart S.N., Gnanaolivu R., Huang H., Lee K.Y., Na J., Gao C., Lilyquist J., Yadav S., Boddicker N.J., et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:440–451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malone K.E., Begg C.B., Haile R.W., Borg A., Concannon P., Tellhed L., Xue S., Teraoka S., Bernstein L., Capanu M., et al. Population-based study of the risk of second primary contralateral breast cancer associated with carrying a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:2404–2410. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.24.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malone K.E., Reding K.W. In: Breast Cancer Epidemiology. Li C., editor. Springer New York; 2010. Inherited predisposition: familial aggregation and high risk genes; pp. 277–299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee A., Mavaddat N., Wilcox A.N., Cunningham A.P., Carver T., Hartley S., Babb de Villiers C., Izquierdo A., Simard J., Schmidt M.K., et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction modelincorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet. Med. 2019;21:1708–1718. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahabreh I.J., Kent D.M. Index event bias as an explanation for the paradoxes of recurrence risk research. JAMA. 2011;305:822–823. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smits L.J.M., van Kuijk S.M.J., Leffers P., Peeters L.L., Prins M.H., Sep S.J.S. Index event bias-a numerical example. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;66:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer I., Schaapveld M., Oldenburg H.S.A., Sonke G.S., McCool D., van Leeuwen F.E., Van de Vijver K.K., Russell N.S., Linn S.C., Siesling S., et al. The influence of adjuvant systemic regimens on contralateral breast cancer risk and receptor subtype. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019;111:709–718. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verhoog L.C., Brekelmans C.T., Seynaeve C., Meijers-Heijboer E.J., Klijn J.G. Contralateral breast cancer risk is influenced by the age at onset in BRCA1-associated breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:384–386. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuchenbaecker K.B., Hopper J.L., Barnes D.R., Phillips K.A., Mooij T.M., Roos-Blom M.J., Jervis S., van Leeuwen F.E., Milne R.L., Andrieu N., et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317:2402–2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engel C., Fischer C., Zachariae S., Bucksch K., Rhiem K., Giesecke J., Herold N., Wappenschmidt B., Hübbel V., Maringa M., et al. Breast cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and noncarriers under prospective intensified surveillance. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;146:999–1009. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao K., Sisco M., Bedrosian I. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: current perspectives. Int. J. Womens Health. 2016;8:213–223. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.S82816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown D., Shao S., Jatoi I., Shriver C.D., Zhu K. Trends in use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy by racial/ethnic group and ER/PR status among patients with breast cancer: A SEER population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;42:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong S.M., Freedman R.A., Sagara Y., Aydogan F., Barry W.T., Golshan M. Growing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy despite no improvement in long-term survival for invasive breast cancer. Ann. Surg. 2017;265:581–589. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheepens J.C.C., Veer L.v.'t., Esserman L., Belkora J., Mukhtar R.A. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a narrative review of the evidence and acceptability. Breast. 2021;56:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reiner A.S., Robson M.E., Mellemkjær L., Tischkowitz M., John E.M., Lynch C.F., Brooks J.D., Boice J.D., Knight J.A., Teraoka S.N., et al. Radiation treatment, ATM, BRCA1/2, and CHEK2∗1100delC pathogenic variants and risk of contralateral breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020;112:1275–1279. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vocka M., Zimovjanova M., Bielcikova Z., Tesarova P., Petruzelka L., Mateju M., Krizova L., Kotlas J., Soukupova J., Janatova M., et al. Estrogen receptor status oppositely modifies breast cancer prognosis in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers versus non-carriers. Cancers. 2019;11:738. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phipps A.I., Li C.I. In: Breast Cancer Epidemiology. Li C., editor. Springer New York; 2010. Breast cancer biology and clinical characteristics; pp. 21–46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., van den Broek A.J., Schmidt M.K. Letter to the editor regarding: ‘Association between BRCA mutational status and survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021;188:821–823. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin W.-Y., Camp N.J., Cannon-Albright L.A., Allen-Brady K., Balasubramanian S., Reed M.W.R., Hopper J.L., Apicella C., Giles G.G., Southey M.C., et al. A role for XRCC2 gene polymorphisms in breast cancer risk and survival. J. Med. Genet. 2011;48:477–484. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan C., Zhang J., Ouyang T., Li J., Wang T., Fan Z., Fan T., Lin B., Xie Y. RAD50 germline mutations are associated with poor survival in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2018;143:1935–1942. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber-Lassalle N., Hauke J., Ramser J., Richters L., Groß E., Blümcke B., Gehrig A., Kahlert A.-K., Müller C.R., Hackmann K., et al. BRIP1 loss-of-function mutations confer high risk for familial ovarian cancer, but not familial breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20:7. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.