Abstract

Versions of cognitive behavioral therapy (Coping Cat, CC; Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism, BIACA) have shown efficacy in treating anxiety among youth with autism spectrum disorder. Measures of efficacy have been primarily nomothetic symptom severity assessments. The current study examined idiographic coping outcomes in the Treatment of Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorder study (N = 167). Longitudinal changes in coping with situations individualized to youth fears (Coping Questionnaire) were examined across CC, BIACA and treatment as usual (TAU) in a series of multilevel models. CC and BIACA produced significantly greater improvements than TAU in caregiver-reported coping. Youth report did not reflect significant differences. Results show the efficacy of CC and BIACA in improving idiographic caregiver-, but not youth-, reported youth coping.

Keywords: Anxiety, Autism spectrum disorder, Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Idiographic assessment, Coping

Anxiety commonly co-occurs among youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Joshi et al., 2010; Simonoff et al., 2008). Approximately 40% of youth on the autism spectrum show clinically elevated or diagnosable anxiety (Kerns et al., 2020; Van Steensel et al., 2011), although estimates range considerably across studies (11–84%; White et al., 2009). Co-occurring anxiety has been associated with additional functional challenges beyond ASD-specific difficulties (White et al., 2009), including increases in depressive symptoms (Strang et al., 2012), self-injurious behavior, parental stress (Kerns et al., 2015) and difficulties in school/work, social and home/family functioning (Ung et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2012). Left untreated, anxiety among individuals with ASD remains stable over time, persisting into adulthood (Hollocks et al., 2019; Teh et al., 2017).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an efficacious treatment for anxiety disorders in youth (James et al., 2020), has shown promise in the treatment of co-occurring anxiety among youth with ASD. CBT has outperformed control conditions and shown robust effects in youth with primary ASD comparable to those observed among typically developing children (Sukhodolsky et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2015). In the TAASD (Treatment of Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorder) study, one of the few studies to compare standard-of-practice CBT (Coping Cat, CC; Kendall & Hedtke 2006a; Kendall & Hedtke, 2006b) to a CBT protocol tailored to the needs of youth on the autism spectrum [i.e., increased emphasis on social communication, self-regulation; Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA); Kerns et al., 2016], positive outcomes were reported for both CBT conditions compared to treatment as usual (TAU; Wood et al., 2020). Additional benefits were found for BIACA on independent evaluator (IE)-reported outcomes and parent reports of emotion dysregulation, social-communication and adaptive functioning; youth self-reports were not examined as primary outcomes. Another study similarly found that brief CBT reduced anxiety symptoms among children diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, with added benefits associated with more intensive parental involvement compared to CBT for the child alone (Sofronoff et al., 2005).

Outcome measures used to assess CBT efficacy for youth with co-occurring ASD and anxiety have been primarily nomothetic (e.g., Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule Clinical Severity Rating, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale; Ung et al., 2015) with a focus on broad-based anxiety symptom severity. This approach provides a global assessment of how an individual’s anxiety symptom reduction compares to a broader population (Haynes & O’Brien, 2000; Haynes et al., 2009). There may be additional benefit to examining idiographic measures, in which individual clients are compared to themselves (Haynes et al., 2000), so that changes in personalized treatment targets throughout the intervention period can be tracked (Christon et al., 2015). Assessment of individualized outcomes may be particularly relevant within the context of youth ASD treatment, given the heterogeneity in characteristics of ASD (Lord & Jones, 2012) and distinct anxiety presentations (e.g., unusual phobias, fears of loud noises) observed among youth with ASD that might impact precision of youth anxiety symptom measures (Johnco & Storch, 2015; Kerns & Kendall, 2012; Kerns et al., 2021; White et al., 2009; Wood & Gadow, 2010). Use of idiographic outcome measures aligns with personalized treatment objectives (Ng & Weisz, 2016) and can help to address barriers to implementation of evidence-based practices for youth with ASD by increasing relevance of clinical outcomes to families (Lord et al., 2005).

An emphasis on person-specific measures must be balanced with theoretically-driven outcome assessments in line with treatment objectives (Lord et al., 2005; Wolery & Garfinkle, 2002). A key treatment target in CBT for anxiety is youth coping (Prins & Ollendick, 2003), which has been defined as “conscious volitional efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, behavior, physiology and the environment in response to stressful events or circumstances” (Compas et al., 2001, p. 89). The objective of CBT is for youth and caregivers to learn that youth can cope with anxiety-provoking situations; this is thought to be accomplished through learning adaptive coping skills and practicing these skills via graduated exposure (Kendall et al., 2002; Kendall et al., 2006). Changes in youth coping have been highlighted as a mediator across several studies (Chu & Harrison, 2007; Pereira et al., 2018), including in the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Treatment Study (CAMS; Walkup et al., 2008), where improvements in coping efficacy per youth and parent report mediated change in anxiety symptoms for the three active treatment conditions (CBT, sertraline, combination of CBT and sertraline; Kendall et al., 2016). Other studies in samples of youth with primary anxiety disorders have found significant correlations between change in youth and parent-reported coping and posttreatment anxiety severity and measures of treatment response (Crane & Kendall, 2020). Taken together, findings lend support to coping as an important variable to consider when examining CBT outcomes in addition to more general anxiety severity measures.

The idiographic Coping Questionnaire (CQ) assesses youth ability to cope with anxiety-provoking situations tailored to his/her/their specific fears (Kendall, 1994; Crane et al., 2020). A key benefit of this measure is availability of caregiver and youth report versions (CQ-P and CQ-C, respectively). Caregivers are active participants in youth treatments (i.e., driving youth to sessions, ensuring homework completion) and consequently offer a key perspective on youth treatment response (Weisz et al., 2011). However, caregivers observe youth behaviors in specific contexts, and cross-informant correspondence is often lower for less observable internalizing concerns (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Thus, youth perspectives on their internal experiences are important to include in a multi-informant approach to measurement. Considerable variability in caregiver and youth reports of anxiety symptoms has been reported for youth with ASD (White et al., 2009), with youth often perceiving themselves as having lower symptoms (Mazefsky et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2005); this is consistent with low-to-moderate cross-informant correspondence rates for child and adolescent mental health concerns more broadly (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Informant discrepancies have also been reported specifically for treatment outcomes among youth with ASD, with sensitivity to change only emerging per caregiver report (Sukhodolsky et al., 2013). Converging evidence suggests that youth reports show lower effect sizes for treatment response, although informant does not moderate outcomes (Ung et al., 2014). Taken together, findings point to the importance of a multi-informant approach to assessing treatment outcomes for youth with ASD.

The current study conducted a secondary analysis of the TAASD study sample (N = 167) to examine caregiver-(CQ-P) and youth-reported (CQ-C) idiographic youth coping outcomes for youth ages 7–13 years with a diagnosis of ASD and co-occurring anxiety randomized to CC, BIACA or TAU. It was hypothesized that (1) both active treatment conditions (i.e., CC and BIACA) would show positive caregiver-rated coping (CQ-P) outcomes compared to TAU and (2) child-rated coping (CQ-C) would not show differences across treatment conditions, given lower change sensitivity observed among self-report for youth with ASD (Sukhodolsky et al., 2013).

Methods

Participants

Participants included 167 youth and caregiver dyads enrolled in the TAASD study. Youth were aged 7–13 years (M = 9.90, SD = 1.78), with diagnoses of both ASD and maladaptive and interfering anxiety, defined as a score greater than or equal to 14 on the 7-item Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology, 2002). Youth were also required to have an intelligence quotient (IQ) ≥ 70. Youth predominantly identified as male (n = 132/166; 79.5%), White (n = 105/165, 63.6%), and non-Latino or Latina (n = 106/136; 77.9%). A majority of caregivers were married (n = 122/165; 73.9%) and highly educated (i.e., 4-year college degree or more; Mothers: n = 110/163; 67.5%; Fathers: n = 89/158; 56.3.1%). Families volunteered to participate either via self-referral or referral from a physician, educator, or mental health provider in their community. See Kerns et al., (2016) and Wood et al., (2020) for additional detail on the TAASD study rationale, methodology and primary outcome results.

Measures

The Coping Questionnaire (Kendall, 1994) is an idiographic youth self-report (CQ-C) and parent-report (CQ-P) measure of youth’s perceived ability to cope with three anxiety-provoking situations specific to the individual that are rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (not at all able to help myself or him/herself) to 7 (completely able to help myself or him/herself), with a midpoint of 4 (somewhat able to help myself or him/herself). Every CQ-C/P included the same standardized base text to improve internal validity; youth and caregivers were asked: “when you/your child is[individualized anxiety-provoking situation here], are you able to help yourself feel less upset/how well are they able to help themselves feel less upset?” This text was updated with three anxiety-provoking situations unique to each child, with the same set of situations used across youth and caregiver reports for individual youth-caregiver dyads. For example, an individual youth may be asked the following: “when you areworrying about how people feel about you, are you able to help yourself feel less upset?” while their caregivers were asked “when your child isworrying about how people feel about them, how well are they able to help themselves feel less upset?” Responses to the each of the three anxiety-provoking situations were summed to create a total self-reported youth coping (CQ-C) and caregiver-reported youth coping (CQ-P) score, with higher scores indicating greater perceived youth coping efficacy.

The three individualized, anxiety provoking situations were selected based on information provided by families during lengthy baseline assessments administered separately to caregivers and youth by IEs; IEs were trained to reliability in diagnostic assessments, but not CQ-C/P situation selection. Immediately following the diagnostic assessment, both IEs met together and identified which three situations emerged as the most anxiety provoking across interviews. The text of the CQ-C/P were then updated by IEs, with an emphasis on using youth language to describe the feared situation.

The CQ-C and CQ-P have both demonstrated adequate internal consistency and retest reliability, as well as convergent, divergent, and criterion validity in a large sample of youth with anxiety (Crane & Kendall, 2020). Note that the CQ-C/P are both 3-item measures tapping separate and distinct fearful situations specific to the individual youth. Accordingly, high internal consistency estimates were not anticipated. Nevertheless, internal consistency for the CQ-P across time points was α = 0.73 (baseline), α = 0.40 (midpoint), and α = 0.69 (posttreatment). Internal consistency for the CQ-C was α = 0.50 (baseline), α = 0.59 (mid-point), and α = 0.65 (post-treatment).

Procedures

All studies procedures were approved by an institutional review board at each of the three study sites: University of California, Los Angeles, University of South Florida and Temple University. Families provided informed consent, including youth assent. Families completed a pre-treatment evaluation to confirm eligibility that included assessment of perceived coping ability (CQ). Assessment of coping was collected again at the midpoint of treatment (i.e., session 8) and following treatment.

After the initial evaluation, youth were randomized in a 4.5:4.5:1 ratio to one of three 16-week treatments: (1) Coping Cat (n = 72), (2) BIACA (n = 76) or (c) TAU (n = 19). Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006) is a standard-of-practice, manualized CBT protocol for youth with anxiety. It comprises 16 weekly, 60-minute sessions that initially focus on providing youth with skills to cope with (manage) their anxiety, progressing from (1) recognizing somatic responses to anxiety, (2) identifying anxious cognitions and (3) developing a coping plan (Norris & Kendall, 2020). The treatment then transitions to providing youth the opportunity to practice those skills in anxiety-provoking situations (i.e., exposure tasks) in session and at home, while emphasizing reinforcement of effort. Caregiver involvement in this treatment included a 15-minute check-in at the beginning of each session and two caregiver-only sessions.

BIACA (Kerns et al., 2016) is a modular CBT protocol addressing youth anxiety tailored to the needs of youth with ASD that differs from Coping Cat in several ways. First, caregiver involvement was increased; BIACA consisted of 16 weekly sessions 90 minutes in length, where 45 minutes were spent with the youth and 45 minutes were spent with the caregiver. Second, BIACA was a modular protocol guided by an algorithm to select skills relevant to individual youth. As needed, youth were taught social engagement skills (e.g., hosting a playdate, joining a peer at play) and antecedent and incentive-based practice was used to target any externalizing behaviors influencing treatment engagement. Third, to a degree greater than in Coping Cat, youth focused interests were incorporated throughout treatment (e.g., use of focused interests as metaphors for therapeutic concepts) and a reward system was implemented at home and at school to reinforce target behaviors. Further detail on BIACA is available elsewhere (Fujii et al., 2013; Sze & Wood, 2007, 2008; Wood et al., 2011, 2017).

Families randomized to TAU could initiate/continue any treatment approach. No specific treatment recommendations were offered beyond provision of referrals. Following the 16-week study period, families were offered their choice of Coping Cat or BIACA.

Both CBT conditions were provided by advanced graduate students and postdoctoral fellows (N = 19) in clinical psychology, trained to fidelity in both treatments through 8 hours of training and via weekly supervision by licensed psychologists. Audiotaped therapy sessions were regularly monitored and rated for fidelity. Specifically, a random selection of sessions (BIACA N = 92; CC N = 70) were coded for presence/absence of required session topics by principal investigators and trained research assistants; treatment fidelity was high (97% BIACA; 96% CC).

Data Analytic Plan

Longitudinal changes in the coping questionnaire scores were analyzed separately for youth and caregiver report using multilevel models. In these analyses, recruitment site was treated as a random effect. Treatment group was estimated as a three-level contrast, with TAU serving as the reference group.

Results

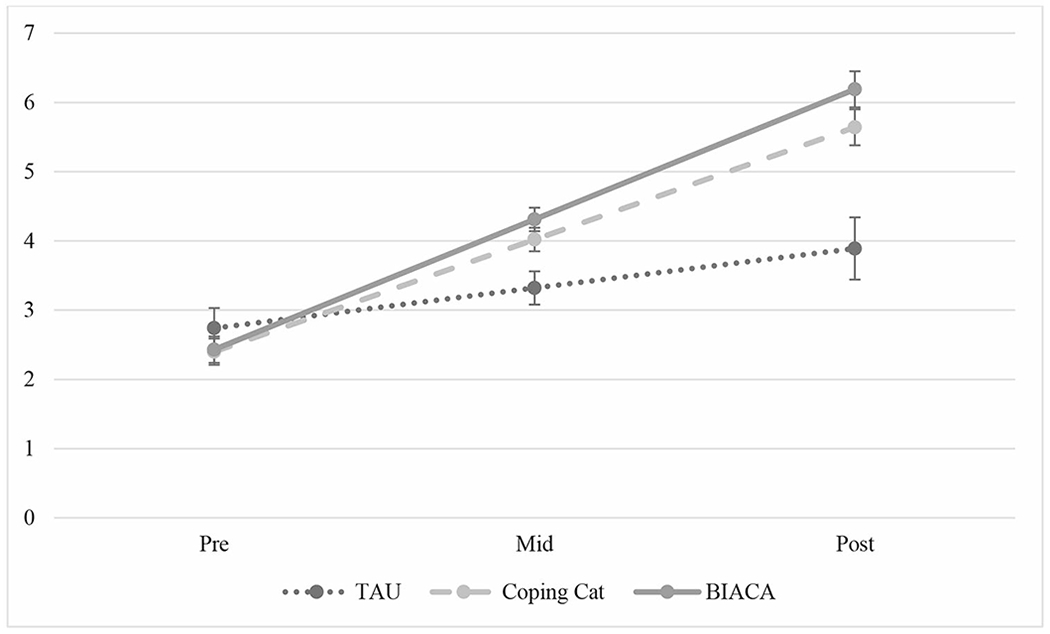

Results for the CQ-P are presented in Table 1; Fig. 1. There was a statistically significant effect of time, with caregiver-reported youth coping improving throughout treatment. No statistically significant effects of treatment group were present, suggesting that CQ-P scores were comparable at baseline. However, a statistically significant interaction between treatment condition and time indicated that the two intervention groups (i.e., CC and BIACA) experienced greater improvements in CQ-P scores over time than did TAU. Longitudinal changes did not differ between CC and BIACA (Estimate = −0.26, SE = 0.21, p = .22).

Table 1.

Longitudinal Changes in Parent Coping Questionnaire

| Estimate | SE | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.75 | 0.29 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.049 | |

| Treatment Group | TAU (ref) | -- | -- | -- |

| Coping Cat | −0.34 | 0.28 | 0.226 | |

| BIACA | −0.32 | 0.28 | 0.263 | |

| Treatment Group X Time | TAU (ref) | -- | -- | -- |

| Coping Cat | 1.05 | 0.33 | 0.002 | |

| BIACA | 1.30 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

Note. TAU = treatment as usual; Ref = reference group; BIACA = behavioral intervention for anxiety in children with autism

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal changes in parent coping questionnaire

Note: TAU = treatment as usual; BIACA = behavioral intervention for anxiety in children with autism

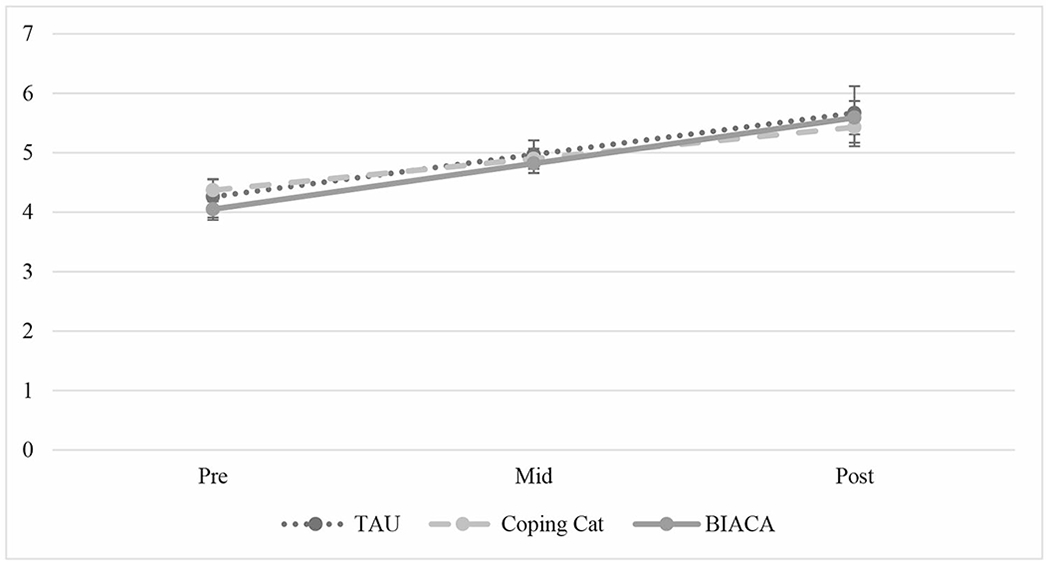

Results for the CQ-C are presented in Table 2; Fig. 2. Consistent with results from the CQ-P, there was (1) a statistically significant effect of time, with youth self-reported coping improving throughout treatment and (2) no statistically significant effect of treatment group, suggesting that CQ-C scores were comparable at baseline. Inconsistent with CQ-P findings, none of the interactions between time and treatment group were statistically significant, indicating that the three groups experienced similar changes over time. Longitudinal changes did not differ for CC and BIACA (Estimate = −0.24, SE = 0.25, p = .34).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Changes in Youth Coping Questionnaire

| Estimate | SE | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.26 | 0.35 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 0.70 | 0.35 | 0.045 | |

| Treatment Group | TAU (ref) | -- | -- | -- |

| Coping Cat | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.779 | |

| BIACA) | −0.32 | 0.28 | 0.263 | |

| Treatment Group X Time | TAU (ref) | -- | -- | -- |

| Coping Cat | −0.18 | 0.39 | 0.657 | |

| BIACA | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.869 |

Note. TAU = treatment as usual; Ref = reference group; BIACA = behavioral intervention for anxiety in children with autism

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal changes in youth coping questionnaire

Note: TAU = treatment as usual; BIACA = behavioral intervention for anxiety in children with autism.

Discussion

The current study examined improvements in caregiver- and youth-reported idiographic youth coping following randomization to CC, an adapted CBT treatment for youth with ASD, or TAU among youth with ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Improvements in caregiver and youth perceptions of youth coping were observed throughout the study period across all conditions, indicating improvements in youth coping over time across both informants. Consistent with hypotheses, youth randomized to CC and BIACA showed significantly improved caregiver-reported youth coping compared to TAU, with both conditions showing comparable gains. There were no significant differences observed between active treatment conditions and TAU per youth report. Thus, active treatment conditions (CC and BIACA) were associated with improved youth coping per caregiver report only.

Results extend findings from the broader TAASD trial showing positive nomothetic anxiety severity outcomes for both CBT and BIACA compared to TAU (Wood et al., 2020) to now include idiographic assessment of caregiver-reported youth coping. Specifically, results suggest that CC and BIACA increase youth ability to cope with individualized anxiety-provoking situations per caregiver report, which is a key goal of CBT-based treatments and active treatment ingredient (Chu et al., 2007; Kendall et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2018; Prins et al., 2003), in addition to changes in more broad-based symptom measures. Such improvements in coping with anxiety-provoking situations individually tailored to youth core fears may be more salient to families than broader symptom reduction. Improvement in CQ-P scores following randomization to active treatments also provides further evidence of CQ-P construct validity (Crane et al., 2020).

Inconsistent with caregiver-report findings, youth self-reported improvements in coping across time, with no significant differences emerging between active treatments (CC and BIACA) and TAU. There are several possible explanations for these findings. Findings may reflect a placebo effect, with youth perceiving improvements in coping due to being in treatment of some kind. Alternatively, insignificant findings per youth report may reflect the fact that youth perceived themselves as having fewer coping deficits at baseline, limiting coping improvement relative to caregiver report at post-treatment; this is consistent with findings that youth with ASD perceive themselves as having fewer symptoms (Mazefsky et al., 2011; Russel et al., 2005; Sukhodolsky et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2014; White et al., 2009) and discrepancies between youth and caregiver reports in youth populations more broadly (Yeh & Weisz, 2001). Finally, although active treatments were more efficacious relative to TAU along caregiver- and IE-reports in the original TAASD trial (Wood et al., 2020), CC and BIACA may not maximally target youth self-perceived coping and further treatment adaptations may improve outcomes.

Taken together, results highlight the importance of a multi-informant approach to outcome monitoring among youth with ASD, consistent with youth assessment guidelines (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Such multi-informant approaches should take care to prioritize both youth and caregiver perspectives in assessing treatment efficacy, avoiding interpretation of differences that emerge across reporters through an “autistic deficits” lens (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021). Caregivers offer critical perspectives on youth treatment response, and are active participants in youth treatments (Weisz et al., 2011). With regards to the CQ-P caregivers may be frequent witnesses to how their child responds to anxiety-provoking situations, and can comment directly on observable evidence of anxiety (i.e., behavioral avoidance, outward signs of distress). Youth offer a similarly critical perspective on internal experiences of anxiety when confronted with anxiety-provoking situations. Consequently, examination of both caregiver- and youth-reported outcomes is worthwhile.

Limitations merit mentioning. First, the sample was primarily Caucasian (77.8%) and non-Hispanic (84.7%), consistent with a broader pattern of over-representation of White youth, and under-representation of Black and Latino/Latina youth, in CBT research for youth with ASD compared to expectations given the current United States Census (Pickard et al., 2018). Under-representation of families with less than a college degree (> 50% college degree or more within TASSD) was also observed, consistent with broader patterns in the literature (Pickard et al., 2018). Thus, reported findings cannot be considered generalizable to all youth with ASD. Further work is needed testing interventions within diverse samples and examining adaptations to treatment incorporating cultural and contextual factors (La Roche et al., 2018). Second, anxiety-provoking situations included in the CQ-C/P were selected by trained and experienced IEs using information from caregiver and youth baseline assessments. IEs were not trained to reliability for this specific measure and there may be threats to validity associated with idiographic measures of this kind. Third, BIACA was a family-based treatment, which may have confounded results, although notably CQ-P outcomes did not differ across CC and BIACA.

Several future directions warrant consideration. First, the CQ-C/P is a brief three-item measure that can be easily assessed at each session. Weekly CQ-C/P data could then be used for a more fine-grained examination of change trajectories during treatment. Mediators of the presented relationship should also be examined. For example, parental accommodation showed significant decreases from pre-to post-treatment in TAASD, and was higher among non-responders (Frank et al., 2020). It is possible that decreased parental accommodation during treatment provides caregivers with increased opportunities to observe youth coping with anxiety-provoking situations independently.

Funding Information

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD080098), National Institutes of Health (F31MH123038; 1P50HD093079) and Department of Defense (AR200108). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50HD103555 for use of the Clinical and Translational Core facilities. The views contained within this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Dr. Storch discloses the following relationships: consultant for Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and Brainsway; Book royalties from Elsevier, Springer, American Psychological Association, Wiley, Oxford, Kingsley, and Guilford; Stock valued at less than $5000 from NView; Research support from NIH, IOCDF, Ream Foundation, and Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Dr Kerns reported receiving honoraria for presenting on her research on anxiety and autism, as well as consultation fees for training staff at other research sites in anxiety and autism assessment, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kendall receives royalties, and his spouse has employment, related to publications associated with the treatment of anxiety in youth. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bottema-Beutel K, Kapp SK, Lester JN, Sasson NJ, & Hand BN (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Quan J, & Wood JJ (2012). Effects of anxiety disorder severity on social functioning in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(3), 235–245 [Google Scholar]

- Christon LM, McLeod BD, & Jensen-Doss A (2015). Evidence-based assessment meets evidence-based treatment: An approach to science-informed case conceptualization. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 36–48 [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, & Harrison TL (2007). Disorder-specific effects of CBT for anxious and depressed youth: A meta-analysis of candidate mediators of change. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10(4), 352–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological bulletin, 127(1), 87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane ME, & Kendall PC (2020). Psychometric Evaluation of the Child and Parent Versions of the Coping Questionnaire. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(5), 709–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, & Rabinowitz J (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological bulletin, 141(4), 858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank HE, Kagan ER, Storch EA, Wood JJ, Kerns CM, Lewin AB, & Kendall PC (2020). Accommodation of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder: Results from the TAASD study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii C, Renno P, McLeod BD, Lin CE, Decker K, Zielinski K, & Wood JJ (2013). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children with autism: A preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health, 5(1), 25–37 [Google Scholar]

- Hollocks MJ, Lerh JW, Magiati I, Meiser-Stedman R, & Brugha TS (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine, 49(4), 559–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, Reardon T, Soler A, James G, & Creswell C (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnco C, & Storch EA (2015). Anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders: implications for treatment. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 15(11), 1343–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Petty C, Wozniak J, Henin A, Fried R, Galdo M, & Biederman J (2010). The heavy burden of psychiatric co-ocurringity in youth with autism spectrum disorders: A large comparative study of a psychiatrically referred population. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40(11), 1361–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SN, & O’Brien WO (2000). Principles of behavioral assessment: A functional approach to psychological assessment. New York: Plenum/Kluwer Press [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SN, Mumma GH, & Pinson C (2009). Idiographic assessment: Conceptual and psychometric foundations of individualized behavioral assessment. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC (1994). Treating anxiety disorders in children: results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 62(1), 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Choudhury M, Hudson J, & Webb A (2002). The C.A.T. Project Manual for the Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Anxious Adolescents. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, & Hedtke KA (2006a). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual (3rd ed.). Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, & Hedtke KA (2006b). Coping Cat Workbook. Workbook Publising Company. Child Therapy Workbooks Series [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Cummings CM, Villabø MA, Narayanan MK, Treadwell K, Birmaher B, & Albano AM (2016). Mediators of change in the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal treatment study. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 84(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, & Kendall PC (2012). The presentation and classification of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 19(4), 323 [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Winder-Patel B, Iosif AM, Nordahl CW, Heath B, Solomon M, & Amaral DG (2021). Clinically significant anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder and varied intellectual functioning. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(6), 780–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Kendall PC, Zickgraf H, Franklin ME, Miller J, & Herrington J (2015). Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: Functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behavior therapy, 46(1), 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Wood JJ, Kendall PC, Renno P, Crawford EA, Mercado RJ, & Storch EA (2016). The treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder (TAASD) study: rationale, design and methods. Journal of child and family studies, 25(6), 1889–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Rast JE, & Shattuck PT (2020). Prevalence and correlates of caregiver- reported mental health conditions in youth with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(1), 11637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Roche MJ, Bush HH, & D’Angelo E (2018). The assessment and treatment of autism spectrum disorder: A cultural examination. Practice Innovations, 3(2), 107 [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Wagner A, Rogers S, Szatmari P, Aman M, Charman T, & Yoder P (2005). Challenges in evaluating psychosocial interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 35(6), 695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, & Jones RM (2012). Annual Research Review: Re-thinking the classification of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(5), 490–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Kao J, & Oswald D (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris LA, & Kendall PC (2020). A close look into Coping Cat: Strategies within an empirically supported treatment for anxiety in youth. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(1), 4–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MY, & Weisz JR (2016). Annual research review: Building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 216–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AI, Muris P, Roberto MS, Marques T, Goes R, & Barros L (2018). Examining the mechanisms of therapeutic change in a cognitive-behavioral intervention for anxious children: The role of interpretation bias, perceived control, and coping strategies. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(1), 73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard K, Reyes N, & Reaven J (2018). Short report: Examining the inclusion of diverse participants in CBT research for youth with ASD and anxiety. Autism, 23(4), 1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins PJ, & Ollendick TH (2003). Cognitive change and enhanced coping:Missing mediational links in cognitive behavior therapy with anxiety-disordered children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(2),87–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell E, Sofronoff K, Russell E, & Sofronoff K (2005). Anxiety and social worries in children with Asperger syndrome. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(7), 633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, & Baird G (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofronoff K, Attwood T, & Hinton S (2005).A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 46(11), 1152–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang JF, Kenworthy L, Daniolos P, Case L, Wills MC, Martin A, & Wallace GL (2012). Depression and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders without intellectual disability. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 6(1), 406–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Bloch MH, Panza KE, & Reichow B (2013). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1341–e1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze KM, & Wood JJ (2007). Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorders and social difficulties in children with high-functioning autism: A case report. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 37(3), 133–143 [Google Scholar]

- Sze KM, & Wood JJ (2008). Enhancing CBT for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders and concurrent anxiety. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(4), 403–409 [Google Scholar]

- Teh EJ, Chan DME, Tan GKJ, & Magiati I (2017). Continuity and change in, and child predictors of, caregiver reported anxiety symptoms in young people with autism spectrum disorder: A follow-up study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(12), 3857–3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ung D, Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Arnold EB, Fuji C, Renno P, & Storch EA (2013). Clinical characteristics of high-functioning youth with autism spectrum disorder and anxiety. Neuropsychiatry, 3(2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ung D, Selles R, Small BJ, & Storch EA (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(4), 533–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Steensel FJ, Bögels SM, & Perrin S (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clinical child and family psychology review, 14(3), 302–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, & Kendall PC (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(26), 2753–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, & Hoagwood KE (2011). Youth Top Problems: using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 79(3), 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, & Scahill L (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical psychology review, 29(3), 216–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery M, & Garfinkle AN (2002). Measures in intervention research with young children who have autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(5), 463–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, & Gadow KD (2010). Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(4), 281 [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Fujii C, & Renno P (2011). Cognitive behavioral therapy in high-functioning autism: review and recommendations for treatment development. Evidence-based practices and treatments for children with autism, 197–230 [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Klebanoff S, Renno P, Fujii C, & Danial J (2017). Individual CBT for anxiety and related symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, 123–141 [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Kendall PC, Wood KS, Kerns CM, Seltzer M, Small BJ, & Storch EA (2020). Cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Jama Psychiatry, 77(5), 474–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, & Weisz JR (2001). Why are we here at the clinic? Parent–child (dis) agreement on referral problems at outpatient treatment entry. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 69(6), 1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]