Abstract

Background.

Blood pressure (BP) control is suboptimal in minority communities, including Asian populations. We evaluate the feasibility, adoption, and effectiveness of an integrated CHW-led health coaching and practice-level intervention to improve hypertension control among South Asian patients in New York City (NYC), Project IMPACT (Integrating Million Hearts for Provider and Community Transformation). The primary outcome was blood pressure (BP) control, and secondary outcomes were systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) at 6-month follow-up.

Methods.

A randomized-controlled trial took place within community-based primary care practices that primarily serve South Asian patients in NYC between 2017 and 2019. A total of 303 South Asian patients aged 18–85 with diagnosed hypertension and uncontrolled BP (SBP≥140 mmHG or DBP≥90 mmHg) within the previous six months at 14 clinic sites consented to participate. After completing one education session, individuals were randomized into treatment (n=159) or control (n=144) groups. Treatment participants received four additional group education sessions and individualized health coaching over a 6-month period. A mixed effect generalized linear model with a logit link function was used to assess intervention effectiveness for controlled hypertension (Yes/No), adjusting for practice level random effect, age, sex, baseline SBP, and days between BP measurements.

Results.

Among the total enrolled population, mean age was 56.8±11.2 years and 54.1% were women. At 6-months among individuals with follow-up BP data (treatment, n=154; control, n=137), 68.2% of the treatment group and 41.6% of the control group had controlled BP (p<0.001). In final adjusted analysis, treatment group participants had 3.7 (95% CI, 2.1–6.5) times the odds of achieving BP control at follow-up compared to the control group.

Conclusions.

A CHW-led health coaching intervention was effective in achieving BP control among South Asian Americans in NYC primary care practices. Findings can guide translation and dissemination of this model across other communities experiencing hypertension disparities.

Clinical Trial Registration:

URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03159533

Keywords: Blood Pressure, Hypertension, Community Health Workers, Asian Americans, Primary Prevention

Introduction

The Million Hearts® initiative aims to reduce heart attacks and strokes1 and includes strategies used by clinicians and health centers to improve hypertension control.2 Million Hearts® has focused on public and private sector mobilization for a core set of objectives, which includes cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors.3,4 However, challenges have been identified working with small, community-based primary care practices, which often have limited resources, high staff turnover, and reduced capacity to perform initiative recommendations.5,6 These practices care for a high percentage of racial and ethnic minority patients and are acutely connected with the needs and burdens of these communities.7

Blood pressure (BP) control remains suboptimal in minority groups compared with Whites, and declines in CVD mortality over the past decade have been less evident in Asian American populations.8,9 While a sizeable literature has examined the impact of hypertension interventions for Black communities,10 few have been implemented in South Asian populations.11 South Asians Americans, individuals tracing their heritage to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh or other parts of the South Asian diaspora, experience a disproportionally high burden of CVD, diabetes, and hypertension. Results from a national longitudinal study of South Asians in the United States (U.S.) found that 43% of men and 35% of women between 40–84 years of age had hypertension.12 Additionally, this group experiences distinct cultural, linguistic, and social barriers impeding access to healthcare and lifestyle behavior. A qualitative study on challenges faced by South Asian migrants observed a lack of understanding in how to access relevant self-management resources.13 Although disaggregated data among South Asian subgroups is limited,14 prior research has demonstrated that Asian Americans are less likely than the average population to have their BP checked (74% vs. 83%, respectively).15 Primary care practices also face challenges in supporting the needs of South Asian patients, including ability to offer culturally- and linguistically-appropriate health coaching on chronic disease management,16 which may result in a diminished capacity to identify, manage, and refer South Asian hypertensive patients to appropriate BP management resources. Evidence-based hypertension management programs adapted to the South Asian community hold great potential to mitigate disparities for this population.17

Within the arsenal of evidence-based programs, Million Hearts® has called for the use of community health workers (CHWs) as an impactful method to improve hypertension.18 CHWs, as frontline public health professionals, play an integral role in disseminating effective health interventions through their deep knowledge and connection to communities, cultivated through shared socio-demographic or cultural characteristics and trusted relationships. CHWs provide culturally-appropriate health education, assist in translation or interpretation, and advocate for individual and community health needs, providing vital social support and capacity-building to ensure sustainable health improvements in their communities.19

CHW-based interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in improving hypertension outcomes through medication adherence, appointment keeping, and implementation of lifestyle behavior modifications20 and are recommended as a strategy to improve BP outcomes in minority communities.21 Factors associated with successful implementation of CHW-based hypertension interventions include: strong provider-CHW training and collaboration, engaging CHWs with shared lived experience of their communities, and building community capacity centered around strong networks of community care, including engagement of clinical and community stakeholders.22 In the U.S., CHW-based hypertension interventions have predominantly focused on low income Black or Latino communities.22–24 However, a CHW-led randomized controlled trial (RCT) among Filipino Americans observed 3.2 times greater adjusted odds of BP control for the treatment group vs. the control group.3 While CHW-based interventions have been effective in improving chronic disease outcomes in South Asian American communities,25–27 no studies have investigated the impact on hypertension management. There exists a need to explore implementation of Million Hearts® aims in high-risk South Asian populations.

The overall goal of IMPACT (Integrating Million Hearts for Provider and Community Transformation) was to evaluate the feasibility, adoption, and effectiveness of an integrated CHW-led health coaching and practice-level electronic health record (EHR)-based intervention to improve hypertension control among South Asian patients in New York City (NYC) primary care practices.28 We examine the effect of the program on reductions in systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), and BP control at follow-up.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design

Project IMPACT was informed by a coalition of South Asian community-based organizations established in 2007 with expertise in the development and implementation of culturally-tailored community-clinical linkage models. The coalition provided feedback on the CHW component of the intervention, including review and adaptation of the curriculum, engagement strategies, and patient materials.28 Project IMPACT included two study components: an EHR intervention and a CHW intervention. Details on the EHR intervention component have been described previously.28,29 The CHW intervention utilized an unblinded RCT design and was launched in 14 primary care practice sites one year after EHR intervention implementation. The practices employed an average two full-time and two part-time physicians and served a majority South Asian, Medicaid population, treating 178 patients per week on average.30 CHWs were reflective of the patient population; there were four males and three females ranging from ages mid-20’s to mid 50’s. All spoke Bangla, Hindi, Punjabi, and/or Urdu and received standardized CHW core competency training.31 The study was designed as an integrated intervention; CHWs assisted clinic staff with translations and facilitated medication reminders/refills and appointment scheduling; communication and activities varied by site based on clinic capacity and preferences.32 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of NYU School of Medicine and the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy.

Participants

Participants were recruited from July 2017 to September 2018. A preliminary list of patients meeting criteria for study participation was identified through the EHR registry at each site. Criteria included: South Asian ethnicity using race, ethnicity, language, and surname data; age 18–85; diagnosed hypertension using International Classification of Diseases (ICD9/10) code; and SBP≥140 or DBP≥90 mmHg within the previous six months. These individuals received a letter from their physician inviting participation in the intervention, and CHWs contacted them via telephone to confirm eligibility and assess preferred language and availability to participate in education sessions. CHWs also conducted “tabling” at primary care practice offices, whereby interested patients in the waiting room completed a screening form and confirmed eligibility through a BP reading.

Screened patients were eligible to enroll into the intervention if they met and confirmed the following criteria: 1) self-reported ancestry from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, or the Indo-Caribbean; 2) age 18–85; 3) not pregnant at time of screening; and 4) one of the following: a) a diagnosis of hypertension using ICD9/10 code in practice EHR and an uncontrolled BP reading (SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg) measured at screening; or b) a diagnosis of hypertension and an uncontrolled BP reading at any office visit within six months prior to screening verified during EHR review. Eligible and interested participants were invited to complete the consent process, baseline survey, and attend the first education session.

Of 2,435 individuals screened for eligibility, 2,356 were identified through the EHR and mailed a recruitment letter, and 79 were identified and screened via clinic-based, in-person recruitment. A total of 303 individuals were enrolled into the study (Figure 1). Of those excluded (n=2,129), 203 were ineligible, 312 declined, 388 were initially reached but never completed screening, and 1,226 were not reached, had messages left, or were not contacted because recruitment goals were met. Three additional individuals were ineligible post-consent. Signed informed consent was completed before study enrollment. After participation in the first educational session, by site, individuals were randomly assigned to the treatment (n=159) or control (n=144) group by sex using the Microsoft Excel randomization function. Spousal/family dyads were randomized into the same study arm based on the randomization of women and older individuals; there were 12 dyads in the treatment group and 8 in the control group.

Figure 1.

CONSORT ((Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram.

EHR, Electronic health record; CHW, community health worker

Intervention

CHWs delivered a standard hypertension management curriculum adapted from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Healthy Heart, Healthy Family program, other community-based CHW curriculum materials implemented in South Asian communities, and Million Hearts® Initiative materials. The intervention consisted of five monthly 60–90 minute group education sessions that employed adult learning techniques and group-based activities. All materials were culturally- and linguistically-adapted for relevancy to South Asian populations. Details on the culturally-tailored aspects of the intervention have been described previously; briefly, these included: translation into South Asian languages; inclusion of specific foods, exercise, and cultural norms; and consideration of family dynamics impacting chronic disease management.28 Multiple sessions were held at primary care practice offices and community spaces to accommodate varying participant schedules. CHWs followed up with participants every two weeks by phone or in-person; during these contacts, CHWs engaged participants in goal-setting on hypertension control, including medication adherence, physical activity (PA), and nutrition, as identified jointly by the CHW and the patient. CHWs made referrals to community resources (e.g., food pantries, mental health services) through established partnerships with a network of South Asian serving community-based organizations. Control group participants were instructed to seek care as usual after the first session and were engaged at follow-up timepoints for data collection. They were eligible to participate in the full intervention following study completion.

Outcome Measurements

All outcome measures and survey tools were collected for both treatment and control group participants by the CHWs at baseline, 3-months, and 6-months. BP control (SBP<140 and DBP<90 mm/Hg) at 6-month follow-up was the primary outcome measure, based on 2010 JNC 8 hypertension guidelines, which were current at that time and aligned with the HEDIS reimbursement guidelines.33 Recently recommended AHA guidelines use <130/80 for BP control.34 CHWs collected BP measurements using an Omron 10 Series Upper Arm BP monitor. Three BP measurements were taken after participants were seated for five minutes; the average of the 2nd and 3rd measurements was used. At 6-month follow-up, EHR BP measurements filled in some missing BP readings.

Secondary clinical outcomes included SBP, DBP, and body mass index (BMI). BMI was calculated using weight collected by CHWs using Omron Body Composition Monitor scales and height from the EHR. Asian BMI categorizations (underweight/normal weight: <23, overweight: 23–27.49, and obese: ≥27.5) were used.35 Behavioral measures were collected by CHWs using a survey tool at baseline and follow-up timepoints and included: self-reported BP management (cutting salt from diet, weight reduction, on a PA program, actively learning about healthy meals, and taking one’s own BP); PA (moderate weekly PA, vigorous weekly PA, recommended weekly PA); and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global scale measures (Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, general health, and ability to carry out usual activities).

Statistical Analysis

The planned study sample size was determined based on the main outcome measure: BP control. We assumed that there would be an effect size of 8 percentage points (15% success in the intervention arm vs. 7% success in the control arm). We proposed a study of 350 participants (25 at each of 14 sites) evenly randomized to the two groups; simulations indicated that a study of this size would have >80% power to detect the assumed difference, using a 2-sided, 0.05 level test. These calculations assumed a 20% loss to follow-up.

Percentages and means were calculated for demographic and health behavior measures. Standardized mean differences between groups were calculated for each measure; ≥10% indicated a group imbalance.

For the primary analysis, we compared BP control between the study groups at 6-months. A mixed effect generalized linear model with a logit link function assessed intervention effectiveness for controlled hypertension (Yes/No). The model included a practice level random effect to account for clustering at the practice level, and was adjusted for age, sex, baseline SBP, and days between BP measurements. For secondary analyses, percentages of categorical variables and mean±standard deviation [SD] for continuous variables are presented for baseline and 6-months. Mixed effect linear models and mixed effect generalized linear models with a logit link assessed adjusted group differences at 6-months for continuous and binary outcomes, respectively. All models included the same adjustments as the primary outcome. Three-month BP data was not included in analyses.

A subgroup analysis was performed on individuals self-reporting a diabetes diagnosis, based on our future research interests in co-morbid diabetes and hypertension among South Asians. Percentage of BP control and mean±SD of SBP and DBP are presented for baseline and 6-month time points. Mixed effect generalized linear models (logit link function used for BP control) assessed adjusted group differences in each 6-month BP measure, using previous adjustments.

Results

Descriptive findings

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of randomized individuals. Approximately half of participants were female (54.1%), mean age was 56.8±11.2 years, 45.3% had <high school education, 87.6% were married/living with a partner, and 40.3% were employed. All were foreign-born, and mean years in the U.S. was 13.7±9.9. Although randomization achieved balance across some subject characteristics, we identified group differences using standardized mean differences for years in the U.S., marital status, education, BMI categories, taking BP medication, and current paan use (a South Asian practice of chewing betel nuts). Mean clinical BP measures were statistically but not clinically different for treatment and control groups: BP control (37.7% vs. 42.4%), SBP (137.8 vs. 138.6), DBP (86.3 vs. 86.6), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomized IMPACT participants 2017–18, n=303

| n | Total (n=303) | Intervention (n=159) | Control (n=144) | Standardized mean Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Female, % | 303 | 54.1 | 54.1 | 54.2 | 0.002 |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 303 | 56.8 ± 11.2 | 56.9 ± 11.1 | 56.7 ± 11.4 | 0.018 |

| Time lived in U.S., mean ± SD, y | 295 | 13.7 ± 9.9 | 14.5 ± 10.1 | 12.7 ± 9.7 | 0.187* |

| Married/Living with partner, % | 298 | 87.6 | 89.2 | 85.8 | 0.329* |

| Education, % | 298 | 0.158* | |||

| Less than high school | 45.3 | 45.3 | 45.3 | ||

| High school/Some college | 22.5 | 25.2 | 19.4 | ||

| College graduate | 32.2 | 29.6 | 35.3 | ||

| Employed, % | 298 | 40.3 | 39.7 | 40.9 | 0.022 |

| Clinical measures | |||||

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 302 | 28.1 ± 4.9 | 28.1 ± 4.7 | 28.0 ± 5.2 | 0.014 |

| BMI Categories, % | 302 | 0.161* | |||

| Normal/Underweight (<23.0 kg/m2) | 13.2 | 12.7 | 13.9 | ||

| Overweight (23.0–27.49 kg/m2) | 36.1 | 32.9 | 39.6 | ||

| Obese (≥27.5 kg/m2) | 50.7 | 54.4 | 46.5 | ||

| BP Control | 303 | 39.9 | 37.7 | 42.4 | 0.094 |

| SBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 303 | 138.2 ± 18.5 | 137.8 ± 17.9 | 138.6 ± 19.3 | 0.045 |

| DBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 303 | 86.4 ± 10.2 | 86.3 ± 10.4 | 86.6 ± 10.1 | 0.037 |

| Health behaviors | |||||

| Self-reported diabetes diagnosis | 303 | 52.5 | 57.2 | 52.1 | 0.088 |

| Taking BP medication, % | 302 | 98.0 | 99.4 | 96.5 | 0.203* |

| Moderate weekly PA, mean ± SD, minutes | 295 | 97.2 ± 155.5 | 103.4 ± 178.0 | 90.2 ± 125.4 | 0.085 |

| Vigorous weekly PA, mean ± SD, minutes | 299 | 26.6 ± 73.9 | 25.1 ± 69.8 | 28.2 ± 78.5 | 0.041 |

| Current cigarette smoker, % | 299 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 5.0 | 0.025 |

| Current paan use, % | 295 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 5.7 | 0.149* |

| Global Physical Health, mean ± SD | 278 | 43.0 ± 8.0 | 43.3 ± 8.5 | 42.7 ± 7.4 | 0.075 |

| Global Mental Health, mean ± SD | 294 | 46.9 ± 7.5 | 47.1 ± 7.8 | 46.7 ± 7.1 | 0.049 |

| General health, mean ± SD | 303 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0.050 |

| Carry out usual activities, mean ± SD | 303 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 0.004 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation; mmHG, millimeters of mercury.

Group imbalance in standardized mean difference (≥10%) between intervention and control for years in U.S., marital status, education, BMI categories, BP medication, and paan use

Among treatment group participants, 91% completed the follow-up survey and 86% completed all 5 sessions, while 6% completed the first session only. All completed the goal-setting behavioral action plan and 94% completed at least one additional goal-setting encounter. Among control group participants, 92% completed the follow-up survey.

Effect of the intervention versus control group on BP control

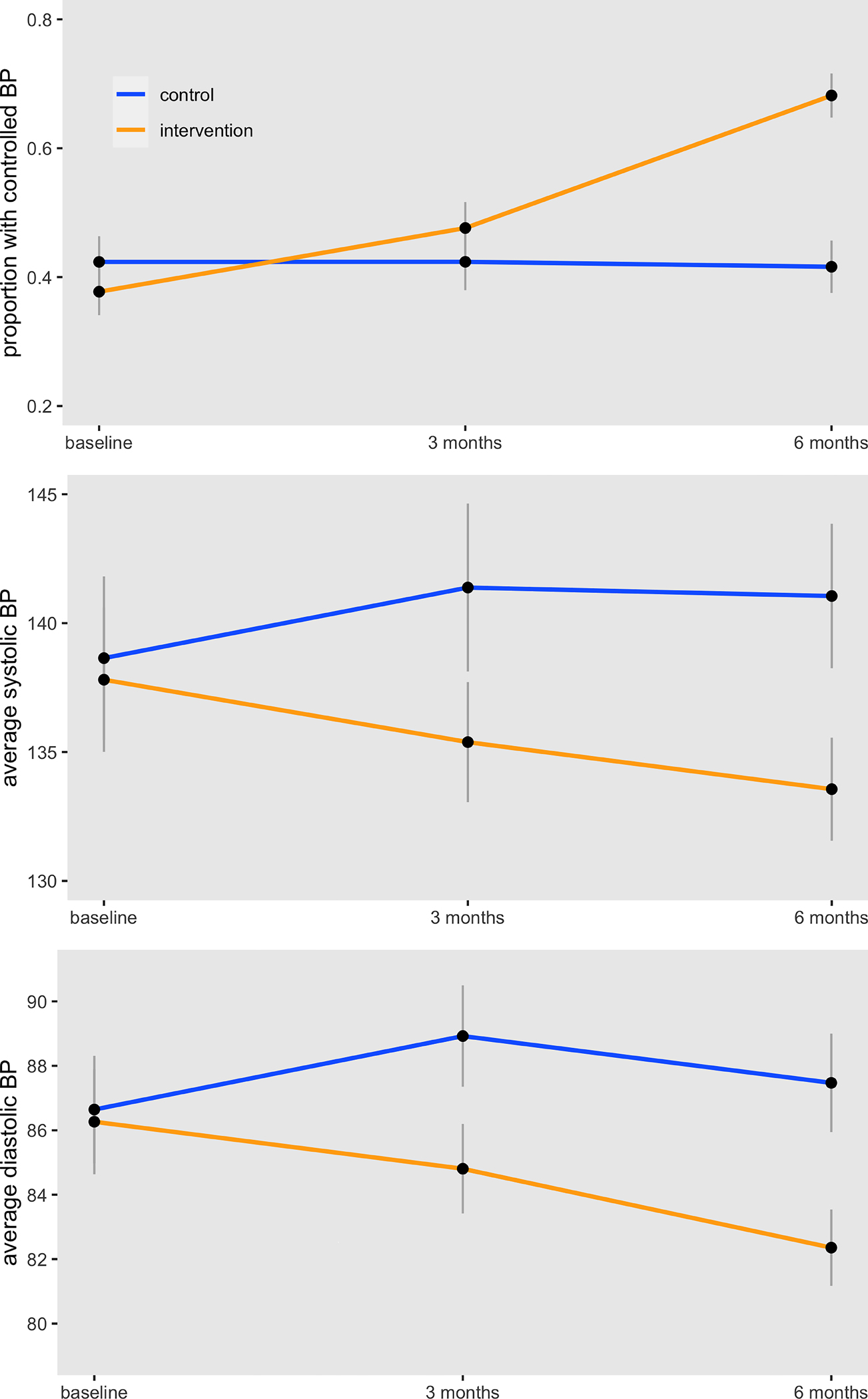

Among individuals with follow-up BP data at 6-months (treatment, n=154, control, n=137), 68.2% of the treatment group and 41.6% of the control group had controlled BP (p<0.001). Individuals in the treatment group had 3.7 (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 2.1–6.5) times the odds of achieving BP control at follow-up, while adjusting for baseline SBP, sex, gender, practice, and days between BP measurements. Initially, a model was fit that also included a family-level effect for family/spousal dyads, but the estimated variance was zero and the effect was not included in the final model. No significant differences were found for BP control in a sex-specific analysis (data not shown). Figure 2 presents BP control by intervention and control group across baseline, 3-month, and 6-month time points.

Figure 2.

Changes in BP Control, SBP, and DBP across intervention (n=154) and control (n=137) groups

Effect of the intervention versus control group on SBP and DBP

Consistent with the main outcome, mean SBP and DBP were lower in the intervention group at 6-months compared to the control group. At 6-months, mean SBP was 133.6±12.6 in the intervention group compared to 141.1±16.6 in the control group (effect size −6.8, 95% CI, −9.5, −4.2); mean DBP was 82.4±7.4 in the intervention group compared to 87.5±9.0 in the control group (effect size −4.7, 95% CI, −6.3, −3.2). Figure 2 presents BP by groups at baseline, 3-month, and 6-month time points.

Changes in BP Control, SBP, and DBP among individuals with diabetes by treatment and control groups

Among a subgroup analysis of individuals self-reporting diabetes (n=161), the treatment group demonstrated a decrease in SBP and DBP, and an increase in BP control, while the control group showed an increase in SBP and DBP and a decrease in BP control. Individuals in the treatment group had 6.3 (95% CI, 2.9–14.8) times the odds of achieving BP control at follow-up compared to individuals in the control group, while adjusting for baseline SBP, sex, gender, practice, and days between BP measurements. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

Changes in secondary outcomes at baseline and 6-month follow-up for intervention and control groups

| Intervention Group | Control Group | Effect Size (95% CI) *† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Baseline | 6-month | N | Baseline | 6-month | ||

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 142 | 28.1 ± 4.8 | 27.8 ± 4.6 | 132 | 27.9 ± 5.3 | 28.3 ± 5.3 | −0.6 (−1.1, −0.2) |

| BP Self-Management, % | |||||||

| Cutting salt from diet | 144 | 65.3 | 81.9 | 133 | 67.7 | 68.4 | 2.6 (1.4, 4.9) |

| Weight reduction | 144 | 20.8 | 31.9 | 133 | 21.8 | 14.3 | 3.3 (1.8, 6.5) |

| On a PA program | 144 | 14.6 | 25.7 | 133 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 3.1 (1.6, 6.4) |

| Actively learning about healthy meals | 144 | 11.8 | 31.3 | 133 | 10.5 | 6.0 | 11.4 (4.8, 30.9) |

| Takes own BP | 144 | 60.3 | 69.0 | 133 | 55.7 | 56.8 | 2.0 (1.0, 3.9) |

| Physical Activity (PA) | |||||||

| Moderate PA, mean ± SD, weekly min | 142 | 104.0 ± 182.0 | 89.8 ± 84.3 | 129 | 92.6 ± 126.2 | 60.0 ± 92.2 | 28.4 (9.4, 47.3) |

| Vigorous PA, mean ± SD, weekly min | 142 | 25.7 ± 69.3 | 8.7 ± 29.5 | 130 | 30.1 ± 81.4 | 10.5 ± 30.5 | −0.8 (−7.7, 6.2) |

| Recommended weekly PA, % | 142 | 30.0 | 30.3 | 129 | 35.8 | 25.6 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.6) |

| PROMIS Global Health, mean ± SD | |||||||

| Global Physical Health | 129 | 42.9 ± 8.7 | 45.1 ± 8.8 | 116 | 41.9 ± 7.2 | 41.4 ± 8.9 | 3.0 (1.4, 4.6) |

| Global Mental Health | 138 | 46.4 ± 7.6 | 49.2 ± 8.0 | 125 | 46.0 ± 6.7 | 46.0 ± 7.7 | 2.9 (1.5, 4.4) |

| General health | 144 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 133 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) |

| Carry out usual activities | 143 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 133 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) |

| BP outcomes among individuals with diabetes | |||||||

| SBP, mean ± SD, mm/Hg | 88 | 137.4 ± 17.9 | 133.5 ± 12.0) | 73 | 138.6 ±19.4 | 144.6 ± 18.1 | −10.7 (−14.4, −7.0) |

| DBP, mean ± SD, mm/Hg | 88 | 84.6 ± 11.2 | 80.5 ± 7.4 | 73 | 85.3 ± 10.9 | 87.7 ± 10.9 | −6.7 (−9.1, −4.1) |

| BP control (<140/90 mmHg), % | 88 | 38.6 | 70.5 | 73 | 43.8 | 38.4 | 6.3 (2.9, 14.8)* |

BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation; mmHG, millimeters of mercury.

Adjusted for baseline measure, sex, age, and practice

odds ratio reported for binary outcomes; for continuous outcomes this is a difference

Difference in behavioral outcomes by treatment and control groups

Table 2 presents baseline and 6-month secondary outcome measures by study group, as well as differences between intervention and control groups for each measure. There was no difference in mean BMI by study group at 6-months. All BP self-management activities were greater for the intervention group compared to the control group. At 6-months, 81.9% of the treatment group reported cutting salt from their diet, compared to 68.4% of the control group (odds ratio [OR]=2.6, 95% CI, 1.4–4.9); 31.9% of the treatment group reported weight reduction compared to 14.3% of the control group (OR=3.3, 95% CI, 1.8–6.5); 25.7% of the treatment group reported being on a PA program compared to 11.3% of the control group (OR=3.1, 95% CI, 1.6–6.4); 31.3% of the treatment group reported actively learning about healthy meals compared to 6.0% of the control group (OR=11.4, 95% CI, 4.8–30.9), and 69.0% of the treatment group reporting taking their own BP compared to 56.8% of the control group (OR=2.0, 95% CI, 1.0–3.9). At 6-months, mean moderate PA was 89.8±84.3 in the treatment group compared to 60.0±92.2 in the control group (effect size 28.4, 95% CI, 9.4–47.3). There was no difference in recommended weekly PA between the groups.

All PROMIS Global Health indicators were higher in the intervention group compared to the control group at 6-months. At 6-months, mean Global Physical Health was 45.1±8.8 in the intervention group compared to 41.4±8.9 in the control group (effect size 3.0, 95% CI, 1.4–4.6); mean Global Mental Health was 49.2±8.0 in the intervention group compared to 46.0±7.7 in the control group (effect size 2.9, 95% CI, 1.5–4.4); mean general health was 3.4±0.8 in the intervention group compared to 3.1±0.7 in the control group (effect size 0.3, 95% CI, 0.1–0.4); and mean of carrying out usual activities was 3.4±0.9 in the treatment group compared to 3.1±0.9 in the control group (effect size 0.3, 95% CI, 0.1–0.5).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a culturally-adapted CHW-led intervention among hypertensive South Asians delivered in community-based primary care practice settings can achieve significant improvements in BP control after six months. While previous research has focused on minority groups such as African Americans and Filipinos,3,22–24 this is the first study designed to improve BP management among South Asian Americans. This is significant because although changes in overall BP control have been examined in community-based lifestyle interventions targeting heart disease and diabetes risk factors among South Asian Americans,25–27,36 to our knowledge this is the first study to examine the impact of implementation of such models in small, community-based primary care practices. While Evidence Now has demonstrated that implementation of community-clinical linkage models in small practice settings can improve BP control,37 the engagement of primary care settings serving South Asian populations in such initiatives has been noticeably absent. Thus, our findings provide support for models to enhance BP control using CHWs in small community-based practice settings for South Asian communities.

Additionally, our findings contribute to the growing evidence-base for the effectiveness of CHW approaches BP control improvement among South Asian populations experiencing disproportionate burdens of CVD risk factors. Community-based lifestyle interventions among South Asian Americans have yielded mixed results with respect to BP outcomes; while some studies observed no significant intervention effect on BP changes,25,27 one study observed a significant reduction in SBP.36 Our findings align with two recent CHW-based hypertension interventions utilizing family-based home education and training of physicians conducted among South Asians in their home country,38,39 which similarly observed significantly greater BP control in the intervention group.

The intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in BP control self-management strategies and PROMIS Global Health measures compared to the control group. While both groups showed an increase in self-reported weekly and moderate PA at follow-up, our regression analyses found that the treatment group had higher moderate weekly PA at 6-months compared to the control group. Similar intervention have shown improvements in PA-related outcomes among South Asians Americans,25,27 although one community-based trial observed no significant between-group differences.25 The impact of the intervention on behavioral outcomes indicates that culturally-adapted CHW models are important in improving patient activation in hypertension self-management for underserved populations facing linguistic and cultural barriers to care, aligning with previous findings.22,23 The improvements in physical, mental, and overall health measures provide important evidence on the impact of CHWs in improving well-being, particularly among immigrant and minority communities, lending support to a growing body of literature on the multi-faceted ways in which CHWs improve health.40,41

Finally, our intervention demonstrated SBP and DBP reduction and greater BP control among individuals with co-morbid diabetes and hypertension. While evidence supports targeting BP reduction to <140/90 mmHg among individuals with diabetes42 and clinical and lifestyle recommendations promote hypertension control for individuals with diabetes,43 there is a gap in the implementation of evidence-based strategies to address co-morbidities among minority communities that face social and cultural barriers in chronic disease management. Previous interventions among South Asian immigrants with diabetes have not examined BP outcomes or have not observed significant intervention effects. Our findings provide important support in addressing co-morbid diabetes and hypertension in South Asian and other high-risk communities – rather than addressing a singular chronic disease - through a CHW model that provides culturally-tailored health coaching on CVD risk reduction more broadly. This high-risk subgroup analysis was not an original focus of our intervention, but will be further explored in future research.27,44

Study Limitations and Strengths

The study has some limitations. First, this was an unblinded RCT, which may lead to response bias but does not detract from the study findings, and behavioral measures were collected by the CHWs, which may lead to overestimations in both groups. Second, study-collected BP measurements were missing for 9% of individuals at 6-months and for 12.5% of individuals at 3-months; we supplemented missing 6-month BP measurements using EHR medical records for a completion rate of 96%. The EHR-obtained measurements reflect a single reading, rather than the average of 2nd and 3rd readings. Third, key study measurements were not included (e.g., number of physician visits, changes in medication dosage, and non-adherence to medication), which may account for some of the BP control change. Fourth, our study was conducted in a limited English proficient, predominantly immigrant, South Asian population, and findings may not be generalizable to other minority communities. Fifth, our models did not include lifestyle changes that may be linked to BP reduction; these predictors will be evaluated in future analyses. A large number of eligible individuals could not be reached for engagement in the program; this limitation should be considered in future replication and scale-up efforts. Finally, we did not examine the sustainability of BP outcomes after six months or the relationship between intervention dosage and outcomes, which will be explored in future analyses.

As the first study to examine the effectiveness of a CHW intervention on hypertension management among South Asian Americans using a rigorous RCT design, our results provide support to strategies designed to advance BP control among minority populations, particularly those seeking care in small primary care practices. We contribute to the evidence-base that CHWs are effective members of the healthcare team and can deliver lifestyle interventions in limited English proficient, immigrant communities.

Our study findings contribute empirical evidence that culturally-relevant models can be effectively implemented for hypertension management in diverse populations. Given the recent growth of the U.S.-based South Asian population, the high burden of hypertension and CVD faced by South Asians, and the context of the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic which has demonstrated worse outcomes for minority communities and individuals with CVD co-morbidities,45,46 integrating CHWs into clinical care through sustainable models may be particularly relevant for South Asian communities. CHW approaches also facilitate adherence to medication and health promotion strategies and address upstream factors impacting chronic disease management.41 Past studies have suggested that CHWs are a cost-effective model for chronic disease management among minority or underserved communites.47 As the demand for patient-centered approaches in clinical settings expands, CHW models have growing clinical and public health relevance in the context of hypertension management.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Blood pressure (BP) is suboptimal in many minority communities, including South Asian Americans.

The integration of CHWs into primary care teams can improve hypertension management; but this model has not been evaluated in South Asian American populations.

What the Study Adds:

When evaluating the effectiveness of a CHW-led intervention to improve hypertension control among South Asian patients in primary care practices, participants randomized to the treatment group had over three times the odds of achieving BP control at follow-up compared to the control group in adjusted analysis.

Study findings contribute empirical evidence on the effectiveness of the culturally-relevant CHW models for improving BP control among diverse populations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge IMPACT and DREAM CHWs, our primary care practice network, and South Asian-serving community-based organizations in NYC for their partnership in implementing the intervention. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding organizations.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant U48DP001904). NI’s time is partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grants R01DK110048-01A1, R18DK110740 and P30 DK111022R01DK11048), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant U54MD000538), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 1UG3HL151310), and National Center for Advancing Translational Science (grant UL1TR001445).

Nonstandard abbreviations and acronyms

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CHW

community health worker

- CI

confidence interval

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- EHR

electronic health record

- HCCP

Hypertension Control Change Package

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IMPACT

Integrating Million Hearts for Provider and Community Transformation

- mmHG

millimeters of mercury

- NYC

New York City

- OR

odds ratio

- PA

physical activity

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SD

standard deviation

- U.S.

United States

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

Nadia S. Islam, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Laura C. Wyatt, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Shahmir H. Ali, NYU School of Global Public Health, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Jennifer M. Zanowiak, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Sadia Mohaimin, University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine.

Keith Goldfeld, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Priscilla Lopez, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Rashi Kumar, Healthfirst.

Susan Beane, Healthfirst.

Lorna E. Thorpe, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

Chau Trinh-Shevrin, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Population Health.

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services. About Million Hearts 2027. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/about-million-hearts/index.html. Page last reviewed December 16, 2022.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension Control Change Package for Clinicians. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/files/HTN_Change_Package.pdf. 2015. Accessed February 5.

- 3.Ursua RA, Aguilar DE, Wyatt LC, Trinh-Shevrin C, Gamboa L, Valdellon P, Perrella EG, Dimaporo MZ, Nur PQ, Tandon SD, et al. A community health worker intervention to improve blood pressure among Filipino Americans with hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2018;11:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backman DR, Kohatsu ND, Yu Z, Abbott RE, Kizer KW. Implementing a Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve Hypertension Control and Advance Million Hearts Among Low-Income Californians, 2014–2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services. Success Story: Using Practice Facilitation to Improve Care Delivery. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/partners-progress/champions/success-stories/2018-communityoutreach.html. Page last reviewed May 5, 2020.

- 6.Islam N, Rogers ES, Schoenthaler EA, Thorpe LE, Shelley D. A Cross-Cutting Workforce Solution for Implementing Community-Clinical Linkage Models. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:S191–S193. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casalino LP, Pesko MF, Ryan AM, Mendelsohn JL, Copeland KR, Ramsay PP, Sun X, Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. Small primary care physician practices have low rates of preventable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1680–1688. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastings KG, Jose PO, Kapphahn KI, Frank AT, Goldstein BA, Thompson CA, Eggleston K, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Leading Causes of Death among Asian American Subgroups (2003–2011). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maraboto C, Ferdinand KC. Update on hypertension in African-Americans. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali SH, Islam NS, Commodore-Mensah Y, Yi SS. Implementing Hypertension Management Interventions in Immigrant Communities in the U.S.: a Narrative Review of Recent Developments and Suggestions for Programmatic Efforts. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2021;23:5. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandula Namratha R, Kanaya Alka M, Liu K, Lee Ji Y, Herrington D, Hulley Stephen B, Persell Stephen D, Lloyd-Jones Donald M, Huffman Mark D. Association of 10-Year and Lifetime Predicted Cardiovascular Disease Risk With Subclinical Atherosclerosis in South Asians: Findings From the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) Study. Journal of the American Heart Association.3:e001117. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King-Shier KM, Dhaliwal KK, Puri R, LeBlanc P, Johal J. South Asians’ experience of managing hypertension: a grounded theory study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:321–329. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S196224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volgman Annabelle S, Palaniappan Latha S, Aggarwal Neelum T, Gupta M, Khandelwal A, Krishnan Aruna V, Lichtman Judith H, Mehta Laxmi S, Patel Hena N, Shah Kevin S, et al. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in South Asians in the United States: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Treatments: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e1–e34. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K. Diverse Communities, Common Concerns: Assessing Health Care Quality for Minority Americans. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2002/mar/diverse-communities-common-concerns-assessing-health-care. March 2022. Accessed May 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed SM, Lemkau JP. Cultural issues in the primary care of South Asians. J Immigr Health. 2000;2:89–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009585918590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel J, Mehta A, Rifai MA, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, McEvoy JW, Pandey A, Kanaya AM, Kandula NR, Virani NR, et al. Hypertension guidelines and coronary artery calcification among South Asians: Results from MASALA and MESA. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2021;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Million Hearts ®. Community Health Workers and Million Hearts. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/docs/mh_commhealthworker_factsheet_english.pdf. Accessed February 4.

- 19.National Institute of Health. Role of Community Health Workers. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/healthdisp/role-of-community-health-workers.htm. 2014. Accessed February 9.

- 20.Mills KT, Obst KM, Shen W, Molina S, Zhang HJ, He H, Cooper LA, He J. Comparative Effectiveness of Implementation Strategies for Blood Pressure Control in Hypertensive Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:110–120. doi: 10.7326/M17-1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Community Guide. Cardiovascular disease: Team-based care to improve blood pressure control. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cardiovascular-disease-team-based-care-improve-blood-pressure-control. April 2012. Accessed August 17, 2020.

- 22.Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, Horsley T, Jack L Jr., Zhang X, Satterfield D. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balcazar HG, Byrd TL, Ortiz M, Tondapu SR, Chavez M. A randomized community intervention to improve hypertension control among Mexican Americans: using the promotoras de salud community outreach model. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:1079–1094. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zha P, Sickora C, Chase S, Erlewein M. An RN/CHW exemplar: Managing hypertension in an urban community. J Comm Pub Health Nurs. 2016;2:2. doi: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandula NR, Dave S, De Chavez PJ, Bharucha H, Patel Y, Seguil P, Kumar S, Baker DW, Spring B, Siddique J. Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: the South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study; a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1064. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2401-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel RM, Misra R, Raj S, Balasubramanyam A. Effectiveness of a Group-Based Culturally Tailored Lifestyle Intervention Program on Changes in Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes among Asian Indians in the United States. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:2751980–2751980. doi: 10.1155/2017/2751980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Taher MD, Riley L, Tandon SD, Tanner M, Mukherji BR, Trinh-Shevrin C. A Culturally Tailored Community Health Worker Intervention Leads to Improvement in Patient-Centered Outcomes for Immigrant Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36:100–111. doi: 10.2337/cd17-0068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez PM, Zanowiak J, Goldfeld K, Wyka K, Masoud A, Beane S, Kumar R, Laughlin P, Trinh-Shevrin C, Thorpe L, et al. Protocol for project IMPACT (improving millions hearts for provider and community transformation): a quasi-experimental evaluation of an integrated electronic health record and community health worker intervention study to improve hypertension management among South Asian patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:810. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2767-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Divney AA, Lopez PM, Huang TT, Thorpe LE, Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS. Research-grade data in the real world: challenges and opportunities in data quality from a pragmatic trial in community-based practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26:847–854. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez PM, Divney A, Goldfeld K, Zanowiak J, Gore R, Kumar R, Laughlin P, Sanchez R, Beane S, Trinh-Shevrin C, et al. Feasibility and Outcomes of an Electronic Health Record Intervention to Improve Hypertension Management in Immigrant-serving Primary Care Practices. Med Care. 2019;57 Suppl 6 Suppl 2:S164–S171. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruiz Y, Matos S, Kapadia S, Islam N, Cusack A, Kwong S, Trinh-Shevrin C. Lessons learned from a community-academic initiative: the development of a core competency-based training for community-academic initiative community health workers. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2372–2379. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gore R, Dhar R, Mohaimin S, Lopez PM, Divney AA, Zanowiak JM, Thorpe LE, Islam N. Changing Clinic-Community Social Ties in Immigrant-Serving Primary Care Practices in New York City: Social and Organizational Implications of the Affordable Care Act’s Population-Health-Related Provisions. Rsf-Rus Sage J Soc S. 2020;6:264–288. doi: 10.7758/Rsf.2020.6.2.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Controlling High Blood Pressure (CBP). https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/controlling-high-blood-pressure/. 2022. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 35.Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim S, Wyatt LC, Chauhan H, Zanowiak JM, Kavathe R, Singh H, Kwon SC, Trin-Shevrin C, Islam NS. A Culturally Adapted Diabetes Prevention Intervention in the New York City Sikh Asian Indian Community Leads to Improvements in Health Behaviors and Outcomes. Health Behav Res. 2019;2. doi: 10.4148/2572-1836.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon SC, Patel S, Choy C, Zanowiak J, Rideout C, Yi S, Wyatt L, Taher MD, Garcia-Dia MJ, Kim SS, et al. Implementing health promotion activities using community-engaged approaches in Asian American faith-based organizations in New York City and New Jersey. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:444–466. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0506-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jafar TH, Hatcher J, Poulter N, Islam M, Hashmi S, Qadri Z, Bux R, Khan A, Jafary FH, Hameed A, et al. Community-based interventions to promote blood pressure control in a developing country: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:593–601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-9-200911030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jafar TH, Gandhi M, de Silva HA, Jehan I, Naheed A, Finkelstein EA, Turner EL, Morisky D, Kasturiratne A, Khan AH, et al. A Community-Based Intervention for Managing Hypertension in Rural South Asia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:717–726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam N, Shapiro E, Wyatt L, Riley L, Zanowiak J, Ursua R, Trinh-Shevrin C. Evaluating community health workers’ attributes, roles, and pathways of action in immigrant communities. Prev Med. 2017;103:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peretz PJ, Islam N, Matiz LA. Community Health Workers and Covid-19 - Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond. N Engl J Med. 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2022641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cryer MJ, Horani T, DiPette DJ. Diabetes and Hypertension: A Comparative Review of Current Guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:95–100. doi: 10.1111/jch.12638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Boer IH, Bangalore S, Benetos A, Davis AM, Michos ED, Muntner P, Rossing P, Zoungas S, Bakris G. Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1273–1284. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khunti K, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Carey M, Davies MJ, Stone MA. Educational interventions for migrant South Asians with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2008;25:985–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Townsend MJ, Kyle TK, Stanford FC. Outcomes of COVID-19: disparities in obesity and by ethnicity/race. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020;44:1807–1809. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0635-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abuelgasim E, Saw LJ, Shirke M, Zeinah M, Harky A. COVID-19: Unique public health issues facing Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45:100621. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Community Guide. Cardiovascular Disease: Interventions Engaging Community Health Workers. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cardiovascular-disease-prevention-and-control-interventions-engaging-community-health. March 2015. Accessed August 17, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.