Abstract

Introduction

The effectiveness of psychotherapy in depression is subject of an ongoing debate. The mechanisms of change are still underexplored. Research tries to find influencing factors fostering the effect of psychotherapy. In that context, the dose–response relationship should receive more attention. Increasing the frequency from one to two sessions per week seems to be a promising start. Moreover, the concept of expectations and its influence in depression can be another auspicious approach. Dysfunctional expectations and the lack of their modification are central in symptom maintenance. Expectation focused psychological interventions (EFPI) have been investigated, primarily in the field of depression. The aim of this study is to compare cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) once a week with an intensified version of CBT (two times a week) in depression as well as to include a third proof-of-principle intervention group receiving a condensed expectation focused CBT.

Methods and analysis

Participants are recruited through an outpatient clinic in Germany. A current major depressive episode, diagnosed via structured clinical interviews should present as the main diagnosis. The planned randomised-controlled trial will allow comparisons between the following treatment conditions: CBT (one session/week), condensed CBT (two sessions/week) and EFPI (two sessions/week). All treatment arms include a total dose of 24 sessions. Depression severity applies as the outcome variable (Beck Depression Inventory II, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale). A sample size of n=150 is intended.

Ethics and dissemination

The local ethics committee of the Department of Psychology, Philipps-University Marburg approved the study (reference number 2020-68 v). The final research article including the study results is intended to be published in international peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

German Clinical Trials Registry (DRKS00023203).

Keywords: depression & mood disorders, health policy, mental health, psychiatry, adult psychiatry, public health

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Practice-oriented randomised controlled design to test the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

The results will add important information to the research body of structural conditions for psychotherapy, allowing further conclusions on how often psychotherapy should be offered.

First study that includes expectation focused psychological interventions (EFPI) assuming dysfunctional expectations as main mechanisms of symptom persistence and the lack of change.

As this is a manualised psychotherapy study designed for depression, the transfer to other disorders may be limited.

For economic reasons, it was opted against a 2×2 design, including only three treatment arms: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) once weekly, CBT two times a week, EFPI two times a week.

Theoretical background

Major depression, as one form of mood disorders, is one of the most common mental disorders with a lifetime prevalence of 13% in Europe.1 In the last decades, research seemed to prove the effectiveness of different treatments for depression.2–5 However, a meta-analysis reassessing the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression with the aim to control methodological biases in meta-analyses puts the effectiveness into question again.6 7 The need to find promising approaches to enhance effectiveness seems obvious. However, treatment research that compares the different psychotherapy procedures with different theoretical backgrounds aiming to find the best techniques might have reached its limits.8 A long line of research started to focus on common or unspecific factors leading to treatment success. Typical common factors are therapeutic relationship or alliance, treatment expectations, empathy and congruence.9 10 Especially the concept of expectations is receiving more and more attention as an important factor in psychopathology.11

Furthermore, the consideration of common structural variables such as the number of sessions, duration of sessions or environmental factors was rather neglected. It not only seems important to consider these factors to augment positive treatment outcome, but also to define an evidence-based professional policy of psychotherapy in healthcare systems. Even in Germany, as one of the few European countries where psychotherapy is paid by health insurance, a length of 12 to 61-weekly 50 min sessions for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the default.12 With exception of the duration, the frequency of sessions per week seems to be rather randomly determined due to convenience and a lack of evidence.

In the last years psychotherapy researchers started investigating the dose–response relationship.13–15 As ‘dose’, different factors can be considered, for example, total number of sessions, number of sessions per week or the session duration. Howard and colleagues16 were one of the first to look at the number of sessions needed to reach symptom recovery by calculating a probit model (dose–response model). After eight sessions, 50% of the patients showed symptom improvement, whereas 75% of the patients improved after 26 sessions. Further evidence confirms the need of approximately 20 sessions to expect a symptom recovery by over half to two-thirds of the patients.14 15 17 18 The change pattern seems to be negatively accelerated, as a greater effect per session occurs in earlier sessions, which then decreases in the later sessions.19–21

A meta-regression analysis showed no significant influence of the duration of the therapy, while replacing one session per week by two sessions per week increased the effect by a small to medium effect size.22 Some studies already showed a positive effect of higher session frequency leading to faster recovery.23–25 Erekson and colleagues,25 for example, showed in a naturalistic setting that a counselling session every week compared with a decreased frequency not only leads to a faster change, but also to a higher likelihood of achieving recovery and achieving it sooner. Moreover, these findings were also supported by an randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing one versus two sessions per week, concluding that two weekly sessions in clinical practice could improve treatment outcome in depression.13 A higher session frequency seems to result in a faster recovery, making it a promising variable to improve the efficiency of psychotherapy.23

Only very few studies dealt with the comparison of intensive and standard treatment regarding the duration of one therapy session. Especially for anxiety disorders, studies are indicating mixed results about the superiority of intensive treatment forms, especially in the long term.26–28 In conclusion, it seems more promising to increase the frequency (ie, two single sessions weekly) of psychotherapy instead of planning double length sessions.

As mentioned above, the concept of expectation and its role in psychopathology should be better considered. The concept of expectations in psychological research leads back to action and decision-making theories.29–31 A consistent definition is still lacking.32 Humans learn through constant prediction updating based on external input.33–35 Experiences lead to the development of specific expectations towards future events and proper behaviour.36 37 However, expectations are not only unidirectionally formed by the external input through experiences. They also influence the experience in future situations beforehand, as it is well-observed in the so-called placebo effects.38–40 Some studies analysed the relationship between initial expectation change and treatment outcome.41–43 As already mentioned above, initial positive outcome expectations are associated to a better treatment outcome, whereas inducing positive outcome expectations or changing negative ones change significantly the treatment outcome in a positive way. Thus, expectations play a central role in psychotherapy, regarding the therapy outcome44 45 or the therapeutic relationship.46 47

According to the underlying theoretical models,48–50 the lack of expectation adaptation after expectation violating information is defined as fundamental. This is mainly explained through two mechanisms: the minimisation of the importance of expectation-disconfirming evidence and the search for or the production of future expectation-confirming evidence.51 The ViolEx-model,11 48 52 adapted by Panitz and colleagues in 2021,50 describes the different processes of expectation adaptation or persistence and transfers it to psychopathology. The model hypothesises that general expectations are formed by the social environment, individual differences (eg, personality traits) and past experiences. These general expectations form situation-specific expectations. Furthermore, different anticipatory reactions are described to highlight different processes influencing the situational outcome (eg, attention steering to expectation-confirming cues rather than to expectation-disconfirming cues). A differentiation between internal (ie, preparation to the situation) and external reactions (ie, assimilation, or experimentation, approach, or avoidance) are made. Assimilation is described as the process of the attempt to confirm the expectation whereby experimentation is defined as the process of wanting to openly collect valid data to check the proper expectation. Transferring this to psychopathology, assimilation can include avoidant behaviour as is well-known in anxiety disorders.53 54 Experimentation is a process that is desired in psychotherapy to adapt dysfunctional or unhelpful thoughts.55 56 If the expectation is violated through an unexpected experience, the initial expectation should be adapted or at least questioned (ie, accommodation). This process is often blocked, especially in patients with depression.57 The ViolEx raises a concept called cognitive immunisation, which can lead to expectation persistence. The process of cognitive immunisation, that is, the reappraisal of disconfirming information in order to maintain prior expectations, is demonstrated in first experimental designs, especially in people with depressive symptoms.57–59 Depressed patients show increased dysfunctional expectations and at the same time a lack of ability to accommodate these dysfunctional expectations after new expectation-disconfirming experiences.49 60 This was already described in the context of learnt helplessness as a fundamental explanatory model of depression.61 Different processes seem to inhibit expectation adaptation by expectation-inconsistent experiences, leading to rigid expectations and thinking.62

Integrating expectation focused psychological interventions (EFPI) into psychotherapy to directly address processes leading to expectation persistence is the next logical step.63 64 Based on the presented theoretical background, mechanisms that lead to rigid thought patterns (eg, anticipatory reactions or immunisation processes) should be made salient, whereby a destabilisation or change of psychopathological expectations and an experimenting behaviour should be fostered. This entails the possibility to integrate new (positive) experiences in future expectations. Kolb and colleagues65 emphasise that individuals should make new experiences to learn. It therefore seems crucial to support patients in making new experiences and to facilitate learning processes that challenge problem-specific expectations. Moreover, making information processing mechanisms (ie, not only assimilation but also immunisation) salient in psychotherapy allows the patients to not only change unhelpful expectations, but also learn to actively influence their processing mechanisms. According to Rief and colleagues,52 effective therapy needs to include successful expectation violations to change dysfunctional expectations that are related to the development and/or maintenance of psychopathology (eg, negative expectations in depression60 66 67). Based on this rational, therapy resistance may be counteracted by directly addressing immunisation processes that are hypothesised to play a crucial role.52 67 All these processes described by the ViolEx model are usually not directly addressed in psychotherapy. As major depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders, this study aims to find possible ways to foster psychotherapy by first specifying the necessary frequency for an effective psychotherapeutic treatment in depression and, second prove the effectiveness of expectation focused CBT in depression.

For this study, three concrete hypotheses are formulated:

A standard CBT protocol leads to a higher reduction in depressive symptoms when applied two times a week, compared with one session a week.

As a pilot, an innovative CBT programme focusing and providing EFPI, also applied two times a week, should lead to a significant reduction in depressive symptoms over time.

The EFPI condition approaching expectations as core mechanisms with two sessions a week will show a superiority over the CBT condition two times a week.

Dysfunctional expectations will have a higher impact on the therapy outcome in the EFPI condition than in the CBT condition.

Methods

Ethics and dissemination

The local ethics committee of the Department of Psychology, Philipps-University Marburg approved the study (reference number 2020-68 v), which was pre-registered under drks.de. The final research article including the study results is intended to be published in an international peer-reviewed journal with the possibility of open access.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were primarily involved in the preparation of the study manuals (especially EFPI). Patients in treatment due to depression were giving input and feedback about the different interventions chosen and/or developed by the study investigators. We intend to provide the main results of the study to interested participants.

Population

Participant recruitment is planned between October 2020 and December 2023. Participants will mainly be recruited at the psychotherapy outpatient clinic (Psychotherapie Ambulanz Marburg) of the Philipps-University Marburg. If a current major depression episode is suspected in the initial interview, the patient will be informed about this study. The following inclusion criteria should be met: participants should be at least 18 years, have a sufficient knowledge of German, have a major depression episode according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) as the main diagnosis and should fulfil a total Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) score over 13 (mild depression). Patients were excluded if they have had a psychotic disorder (now or in the past) or are addicted to substances such as alcohol, drugs, medication. Moreover, if psychopharmacological drugs are prescribed, the intake dose must be stable over the last 4 weeks and not be changed during the treatment and first follow-up phase. In accordance to Bruijniks and colleagues,13 a total sample size of 150 participants is planned (with a supposed small effect size of 0.25 and an alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.92 can be reached with a sample size of 150 by considering repeated measures, within–between interaction).

Study design and procedure

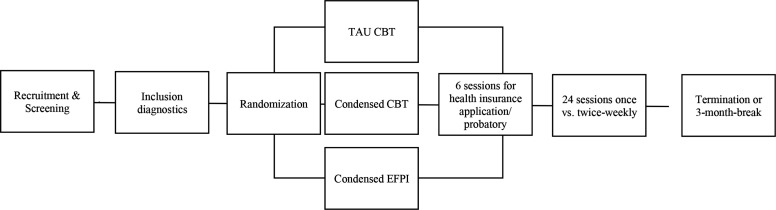

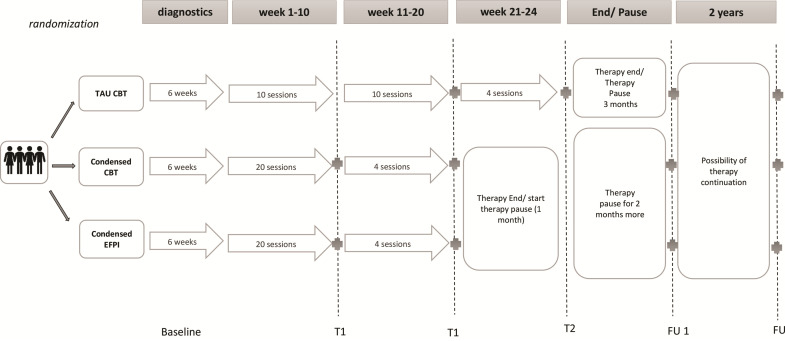

Patients who are interested in study participation undergo a short telephone interview on the inclusion criteria and are then invited to a diagnostic appointment. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are then thoroughly checked. If the inclusion criteria are met, the study procedure is explained, and an informed consent (see online supplemental appendix A1) form is signed. The patients are randomly assigned by one study leader following simple randomisation (computerised random numbers) to one of the three groups and assigned to a study therapist. A coding list is maintained by one of the study leaders during the ongoing study and is going to be deleted after study completion. The first six sessions are used as a run-in phase for assessments and establishing a therapeutic relationship, as well as the collection of further questionnaires and clinical history to confirm the diagnosis. The run-in phase is 6 weeks, frequency and content are independent of the treatment condition. They consist out of anamnesis (eg, with the help of lifeline) and information gathering to draw a micro and macro functional analysis.68 There are no interventions allowed during the run-in phase. Subsequently, the 24 therapy sessions start. Twenty-four sessions are chosen to match the German healthcare plan of a short-term therapy and is in line with the literature presented in the introduction about the number of sessions needed to expect recovery. Depending on the treatment condition, one respectively two therapy sessions take place per week. For those having appointments two times a week, the last four therapy sessions are spread over 10 weeks (see figure 1 & figure 2). Moreover, a diagnostic interview is conducted after the 20th and 24th session. After the end of 24 sessions, a first follow-up diagnostic interview takes place after 3 months of the last (24th) session. During that time, no therapeutic sessions are allowed, and antidepressant medication should be kept stable. Afterwards, further sessions can be conducted if necessary (eg, for the treatment of secondary diagnosis or uncovered symptoms). A second follow-up diagnostic interview is planned 2 years after the end of study treatment (see figure 2).

Figure 1.

Study procedure. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; EFPI, expectation focused psychotherapeutic intervention; TAU, treatment as usual.

Figure 2.

Study design. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; EFPI, expectation focused psychotherapeutic treatment; FU, follow-up; T, measurement timepoint.

bmjopen-2022-065946supp001.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)

Diagnostic assessments

Psychotherapists in post gradual training conduct the diagnostic interviews and are blinded to the condition. In the case of unblinding, the following diagnostic assessments will be conducted by another, still blinded, diagnostician. The diagnostic interviews are supervised by licensed therapists and supervisors. The first diagnostic interview consists of the study information, the informed consent, the implementation of the German version of the Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV),69 and the BDI-II70 by the client and the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)71 by the diagnostician. In the following diagnostic interviews, only the major depression section of the SCID-IV is conducted to rate the MADRS. These external assessments by the diagnosticians take place at baseline, after the 20th and 24th therapy session, as well as after 3 months and 2 years after therapy completion. All self-rating questionnaires are answered after the sessions on a tablet using SoScisurvey.72

Type of treatments

All therapists conducting the study therapy are psychotherapists in training and receive regular supervision (after every fourth therapy session). The first cohort of study therapists receives a workshop on the different treatment conditions and the study flow. The workshop is recorded to easily train new study therapists when needed. All therapists will receive a standardised training and are scheduled to deliver treatment in all three conditions at least once to balance out therapist effects.

In total, the study includes three treatment samples (see online supplemental appendix A2). First, the treatment-as-usual (TAU) group consists of one CBT session per week (TAU CBT). The second group receives a more condensed CBT version with two CBT sessions per week during the main parts of treatment (CBT condensed). The third group also receives two sessions per week, but the CBT approach is based on EFPI (condensed). For the second and third condition, the last four sessions are spread over 10 weeks. After 24 sessions, the treatment according to study protocol is completed. As mentioned above, continuation of therapy, is possible after the 3-month follow-up if necessary. After 2 years, a second follow-up measurement will take place to estimate long-term therapy effectiveness.

CBT manual

The manual is based on the most common CBT manuals, which are already implemented in practice.73–75 It first includes a description of the attitude and behaviour of a CBT therapist.76 The manual is modularised and enables personalisation by a selection of up to three out of seven possible, problem-specific CBT modules. The first session deals with psychoeducation on depression. Typical symptoms are collected, and an individual case concept is developed including cognitions, feelings and behaviour. The seven modules include inactivity, cognitive work, relaxation, problem solving, emotion regulation, interpersonal difficulties and self-esteem. Every module starts with a psychoeducational part linking the patient’s own problems with the respective module. Further on, worksheets are presented, which were designed according to suggestions of different CBT-manuals for depression.76–78 The manual closes in session 24 with relapse prevention.

EFPI manual

Even though the EFPI manual is based on cognitive-behavioural interventions, it was decided to test the manual for feasibility first. Therefore, two therapists in training executed the manualised therapy with two voluntary patients and constantly consulted with the supervisor and the patient. The manual was slightly updated based on the comments of the therapists, supervisor and patients.

In the first six sessions, psychoeducation on the link between expectations and depressive symptoms is delivered. Participants should acquire knowledge about expectations as a specific form of thoughts and how expectations regulate human behaviour. The advantages (eg, fast behaviour planning) and disadvantages (eg, reduced flexibility) of forming expectations are elaborated. The negative consequences of very rigid expectations are discussed. Through self-observation, personal expectations should be made salient. Explicit expectations concerning the therapy are addressed. Further on, the link between the patient’s biography and the origin of their expectations is drawn. An introduction to behavioural experiments as an important tool to test, break, and change dysfunctional expectations is introduced. Cognitive immunisation, as a mechanism of reappraising new information to fit into prior expectations and to prevent expectation change despite contradicting experiences, is explained, and introduced based on the patient’s personal examples.

After the psychoeducation phase, behavioural experiments are to be planned and conducted with the aim to test dysfunctional expectations considering the patient’s immunisation strategies. In contrast to the possible performed behavioural experiments in the CBT condition, the focus in the EFPI condition lies on the understanding of the information processing mechanisms and, consequently, taking control over these by the possibility to actively influence them. The behavioural experiments in the EFPI condition are a new information processing strategy learnt by the patients, rather than a strategy to change the content of expectations. The manual gives examples on behavioural experiments for different depression specific problems (parallel to modules CBT manual). The therapists are supposed to be very flexible in planning behavioural experiments. It is obligatory to carry out at least one behaviour experiment between (or within) each session. For relapse prevention, which is addressed in the 24th session, the prior expectations towards therapy are reviewed, learnt strategies are collected, and future plans are elaborated.

Assessments

The timepoints of the different assessments used are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the study instruments and the survey timepoints

| Domain | Instrument | Inclusion diagnostic | Probatory (6 sessions) | T 10 | T20 | T24 | FU 1 after 3 months | FU 2 after 2 years |

| Demographic and amnestic information | Demographics | x | x | |||||

| Depressive symptom severity | BDI-II | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| MADRS | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| SCID-IV | x | |||||||

| General symptoms | SCL-90 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Therapeutic alliance | HAQ | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Expectations and immunisation | CEQ | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| DES | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Analogue scales about homework, engagement, actual impairment, actual expectation towards treatment, negative expectations | Self-formulated items | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Analogue scales are assessed for every therapeutic session as momentary assessment.

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventiory; CEQ, Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire; DES, Depressive Expectation Scale; HAQ, Helping Alliance Questionnaire; IMS, Immunisation Scale; MADRS, Montgomery Asperg Rating Scale; SCID-IV, Structural Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist.

Demographic variables

Different variables about the participants will be assessed including gender, age, nationality, mother language, education and occupation.

Primary outcome

To analyse symptom reduction the self-rating scale BDI-II—German Version70 is used, as well as the expert rating scale MADRS.71 The MADRS is a 10-item questionnaire for clinicians to rate depressive symptoms on a seven-rating scale while the patient is interviewed by them. Again, a higher sum-score indicates a more severe depression. A sum score of 0–7 means no depression, 7–19 indicates a mild depression, 20–34 moderate and a sum score over 34 is noted as severe depression.

Secondary outcome

Dysfunctional expectations are assessed with the Depressive Expectations Scale.60 To assess the general symptom burden, the revised German version of the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90)79 is used. With 90 items, different symptoms are assessed that are grouped into following subscales: somatisation, compulsivity, depression, insecurity in social contact, anxiety, aggression, phobia, paranoia, psychoticism. Using 25 items, dysfunctional expectations about social rejection, social support, mood regulation and ability to perform are assessed. The therapeutic alliance is assessed with the Helping Alliance Questionnaire80 integrating two 11-item questionnaires, one for the patient and one for the clinician asking about the therapeutic relationship. To assess specific expectations towards the treatment, the six-item credibility/expectancy questionnaire CEQ81 is used.

To test for acceptance, drop-out rates will be compared between the three conditions. Treatment adherence will be controlled by analyses of the recorded sessions by study independent raters.

Every-session monitoring

In every therapy session, patients are supposed to answer questions regarding homework completion, engagement (‘From the last session to this one, my commitment to therapy was’: extremely low to extremely high 0–100), depressive symptoms82 and their own expectations81 to monitor treatment progress. The questions were adapted by the authors for the progress diagnostics.

Statistical analysis

The complete anonymous dataset including all important subject data is regularly supplemented during the ongoing study (a.o., demographics, protocol violations, completed questionnaires). Intention-to-treat analyses are planned. At first, missing values and dropouts will be analysed regarding their distribution. Due to clustered data as well as a certain estimated amount of missing data and a continuous time variable, mixed models for repeated measures shall be calculated.83 In accordance with the study of Bruijniks and colleagues,13 multilevel analyses will be calculated to analyse the frequency condition (once vs two times a week), as well as the intervention form (CBT vs EFPI) on depressive symptoms (BDI-II scores and MADRS scores) over the treatment time first including the interaction terms time×frequency and time×treatment. To analyse if the frequency effect will differ between therapy forms, a second model with the interaction term time×frequency×intervention will be calculated. Significance levels will be set at p<0.05. The same models will be used for secondary outcomes and moderator analyses. Further on, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) will be calculated.

Discussion

This study will analyse the influence of session frequency, as well as the influence of specific expectations on psychotherapy effectiveness. Strengths and limitations are discussed in the following.

Limitations

To standardise the treatment groups, a CBT manual as well as an EFPI manual were written. Depression is known as a highly comorbid disorder,84 85 the manual might not be flexible enough. To counteract the limitation, the CBT manual was modularised, so the therapists have the possibility to choose personalised modules. For the EFPI manual, only the psychoeducation sessions are completely predefined, whereas the chosen topics in therapy are mutually defined by patients and therapists. The only specification by the protocol is that at least one behavioural experiment must be conducted in/between every session. In that sense, the authors support the increasing idea of tailoring psychotherapy to the person.86 As the EFPI treatment is still in its pilot phase and as to avoid underpowered samples, we opted against a 2×2 design, and for the neglect of an EFPI once weekly condition.

Strengths

This study has a well-structured randomised controlled design, whereas the execution of the study is very practice oriented and naturalistic. The study directly addresses the structure of care, allowing people with mental health problems to be helped quickly. The study therapists are all in their psychotherapist training, whereby differences in psychotherapeutic experience and other therapeutic differences are tried to be kept low, as it is done by the randomisation. They are all supervised by CBT or EFPI supervisors. Moreover, the innovative expectation focused therapy manual can be compared directly to a well-established and evidence-based psychotherapy form. We will also evaluate one treatment arm focusing on the maintenance and change of problem-specific expectations. Such a focus promises powerful efficacy, because of its close relation to brain functions, central treatment mechanisms and mechanisms of change.

Expected benefit

Important implications for therapy session frequency can be drawn to create optimal learning conditions. We address the practical execution of psychotherapy and may suggest a certain guideline concerning the frequency of psychotherapy sessions per week. If we confirm existing literature, psychotherapy should be implemented in a shorter time with a two-sessions-per-week-dose. This would especially contribute to reduced waiting time for psychotherapy. In Germany, the waiting time amounted to 20 weeks in 2018,87 whereas during the COVID-19 pandemic the time is estimated to increase constantly.88

Further on, this study will be the first one delivering information on the feasibility of an expectation focused therapy manual in depression. Well-established questionnaires measuring dysfunctional expectations as well as immunisation are not available yet, whereas first attempts to operationalise the concepts have been made.60 Further research should foster valid instruments assessing and validating the constructs of the ViolEx-model. The EFPI intervention promises to be a theory-driven intervention, based on the ViolEx model considering disorder-unspecific common factors, with a clear treatment focus that can result in very powerful effects.41

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: A-CIE: conceptualisation, writing – original draft, project administration. GB: conceptualisation, writing – review & editing, therapist supervision. WR: conceptualisation, supervision, writing – review & editing. PVB: conceptualisation, writing – review & editing. KW: conceptualisation, writing – review & editing, therapist supervision. MW: conceptualisation, writing – review & editing, supervision, project administration.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in europe: results from the european study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (esemed) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004:21–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Maat S, Dekker J, Schoevers R, et al. Relative efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research 2006;16:566–78. 10.1080/10503300600756402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekers D, Richards D, Gilbody S. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychol Med 2008;38:611–23. 10.1017/S0033291707001614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gloaguen V, Cottraux J, Cucherat M, et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. J Affect Disord 1998;49:59–72. 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00199-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroll B, Macgillivray S, Ogston S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:449–56. 10.1370/afm.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, et al. Was eysenck right after all? A reassessment of the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019;28:21–30. 10.1017/S2045796018000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, et al. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry 2016;15:245–58. 10.1002/wps.20346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luborsky L. The Dodo bird verdict is alive and well -- mostly. Clinical Psychology 2002;9:2–12. 10.1093/clipsy/9.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An Update. World Psychiatry 2015;14:270–7. 10.1002/wps.20238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahum D, Alfonso CA, Sönmez E. Common factors in psychotherapy. In: Advances in psychiatry. Springer, 2019: 471–81. 10.1007/978-3-319-70554-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rief W, Glombiewski JA, Gollwitzer M, et al. Expectancies as core features of mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2015;28:378–85. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bundesausschuss, G . Psychotherapie-richtlinie. Bundesanzeiger, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruijniks SJE, Lemmens LHJM, Hollon SD, et al. The effects of once- versus twice-weekly sessions on psychotherapy outcomes in depressed patients. Br J Psychiatry 2020;216:222–30. 10.1192/bjp.2019.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harnett P, O’Donovan A, Lambert MJ. The dose response relationship in psychotherapy: implications for social policy. Clinical Psychologist 2010;14:39–44. 10.1080/13284207.2010.500309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen NB, Lambert MJ, Forman EM. The psychotherapy dose-response effect and its implications for treatment delivery services. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2002;9:329–43. 10.1093/clipsy.9.3.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard KI, Kopta SM, Krause MS, et al. The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. Am Psychol 1986;41:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson EM, Lambert MJ. A survival analysis of clinically significant change in outpatient psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol 2001;57:875–88. 10.1002/jclp.1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen NB, Lambert MJ. An evaluation of the dose-response relationship in naturalistic treatment settings using survival analysis. Ment Health Serv Res 2003;5:1–12. 10.1023/a:1021751307358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barkham M, Rees A, Stiles WB, et al. Dose-effect relations in time-limited psychotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:927–35.:927. 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, et al. Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:1009–16. 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson L, Delgadillo J, Kellett S. The dose-response effect in routinely delivered psychological therapies: a systematic review. Psychother Res 2020;30:79–96. 10.1080/10503307.2019.1566676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuijpers P, Huibers M, Ebert DD, et al. How much psychotherapy is needed to treat depression? A metaregression analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;149:1–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erekson DM, Lambert MJ, Eggett DL. The relationship between session frequency and psychotherapy outcome in a naturalistic setting. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015;83:1097–107. 10.1037/a0039774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reese RJ, Toland MD, Hopkins NB. Replicating and extending the good-enough level model of change: considering session frequency. Psychother Res 2011;21:608–19. 10.1080/10503307.2011.598580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erekson DM, Bailey RJ, Cattani K, et al. Psychotherapy session frequency: a naturalistic examination in a university counseling center. J Couns Psychol 2022;69:531–40. 10.1037/cou0000593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abramowitz JS, Foa EB, Franklin ME. Exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: effects of intensive versus twice-weekly sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:394–8. 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbert JD, Rheingold AA, Gaudiano BA, et al. Standard versus extended cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized-controlled trial. Behav Cognit Psychother 1999;32:131–47. 10.1017/S1352465804001171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohni MK, Spindler H, Arendt M, et al. A randomized study of massed three-week cognitive behavioural therapy schedule for panic disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;120:187–95. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkinson JW, Feather NT. A theory of achievement motivation. 1966: Wiley New York, [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory of decisions under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:1156–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Action control. Springer, 1985: 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laferton JAC, Kube T, Salzmann S, et al. Patients’ expectations regarding medical treatment: a critical review of concepts and their assessment. Front Psychol 2017;8:233. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg M, Feldmann M, Kirchner L, et al. Oversampled and undersolved: depressive rumination from an active inference perspective. PsyArXiv [Preprint] 2021. 10.31234/osf.io/va9c3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Smith R, Kuplicki R, Feinstein J, et al. A Bayesian computational model reveals a failure to adapt interoceptive precision estimates across depression, anxiety, eating, and substance use disorders. PLoS Comput Biol 2020;16:e1008484. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visalli A, Capizzi M, Ambrosini E, et al. Bayesian modeling of temporal expectations in the human brain. Neuroimage 2019;202:116097. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lightsey R. Albert bandura and the exercise of self-efficacy. J Cogn Psychother 1999;13:158. 10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evers AWM, Colloca L, Blease C, et al. Implications of placebo and nocebo effects for clinical practice: expert consensus. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:204–10. 10.1159/000490354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsch I. Response expectancy theory and application: a decennial review. Applied and Preventive Psychology 1997;6:69–79. 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80012-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bingel U. Placebo 2.0: the impact of expectations on analgesic treatment outcome. Pain 2020;161 Suppl 1:S48–56. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rief W, Shedden-Mora MC, Laferton JAC, et al. Preoperative optimization of patient expectations improves long-term outcome in heart surgery patients: results of the randomized controlled PSY-HEART trial. BMC Med 2017;15:4.:4. 10.1186/s12916-016-0767-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Constantino MJ, Ametrano RM, Greenberg RP. Clinician interventions and participant characteristics that foster adaptive patient expectations for psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic change. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2012;49:557–69. 10.1037/a0029440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vîslă A, Constantino MJ, Flückiger C. Predictors of change in patient treatment outcome expectation during cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2021;58:219–29. 10.1037/pst0000371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenberg RP, Constantino MJ, Bruce N. Are patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome? Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:657–78. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Constantino MJ, Vîslă A, Coyne AE, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2018;55:473–85. 10.1037/pst0000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barber JP, Zilcha-Mano S, Gallop R, et al. The associations among improvement and alliance expectations, alliance during treatment, and treatment outcome for major depressive disorder. Psychother Res 2014;24:257–68. 10.1080/10503307.2013.871080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patterson CL, Uhlin B, Anderson T. Clients’ pretreatment counseling expectations as predictors of the working alliance. J Couns Psychol 2008;55:528–34. 10.1037/a0013289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gollwitzer M, Thorwart A, Meissner K. Editorial: psychological responses to violations of expectations. Front Psychol 2017;8:2357. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rief W, Joormann J. Revisiting the cognitive model of depression: the role of expectations. CPE 2019;1:1–19. 10.32872/cpe.v1i1.32605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panitz C, Endres D, Buchholz M, et al. A revised framework for the investigation of expectation update versus maintenance in the context of expectation violations: the violex 2.0 model. Front Psychol 2021;12:5237. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.726432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinquart M, Endres D, Teige-Mocigemba S, et al. Why expectations do or do not change after expectation violation: a comparison of seven models. Consciousness and Cognition 2021;89:103086. 10.1016/j.concog.2021.103086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rief W, Sperl MFJ, Braun-Koch K, et al. Using expectation violation models to improve the outcome of psychological treatments. Clinical Psychology Review 2022;98:102212. 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Craske MG, Rapee RM, Barlow DH. The significance of PANIC-EXPECTANCY for individual patterns of avoidance. Behavior Therapy 1988;19:577–92. 10.1016/S0005-7894(88)80025-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, et al. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther 2014;58:10–23. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Longmore RJ, Worrell M. Do we need to challenge thoughts in cognitive behavior therapy? Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:173–87. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McManus F, Van Doorn K, Yiend J. Examining the effects of thought records and behavioral experiments in instigating belief change. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2012;43:540–7. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kube T, Rief W, Gollwitzer M, et al. Why dysfunctional expectations in depression persist-results from two experimental studies investigating cognitive immunization. Psychol Med 2019;49:1532–44. 10.1017/S0033291718002106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kube T, Rief W, Glombiewski JA. On the maintenance of expectations in major depression-investigating a neglected phenomenon. Front Psychol 2017;8:9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kube T, Glombiewski JA, Gall J, et al. How to modify persisting negative expectations in major depression? an experimental study comparing three strategies to inhibit cognitive immunization against novel positive experiences. J Affect Disord 2019;250:231–40. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kube T, D’Astolfo L, Glombiewski JA, et al. Focusing on situation-specific expectations in major depression as basis for behavioural experiments-development of the depressive expectations scale. Psychol Psychother 2017;90:336–52. 10.1111/papt.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol 1978;87:49–74.:49. 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liknaitzky P, Smillie LD, Allen NB. Out-of-the-blue: depressive symptoms are associated with deficits in processing inferential expectancy-violations using a novel cognitive rigidity task. Cogn Ther Res 2017;41:757–76. 10.1007/s10608-017-9853-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kube T, Glombiewski JA, Rief W. Expectation-focused psychotherapeutic interventions for people with depressive symptoms. Verhaltenstherapie 2019;29:281–91. 10.1159/000496944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rief W, Glombiewski JA. Expectation-focused psychological interventions (EFPI). Verhaltenstherapie 2016;26:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, Mainemelis C. Experiential learning theory: previous research and new directions. In: Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles. Routledge, 2014: 227–48. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kirchner L, Schummer SE, Krug H, et al. How social rejection expectations and depressive symptoms bi-directionally predict each other-a cross-lagged panel analysis. Psychol Psychother 2022;95:477–92. 10.1111/papt.12383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rief W, Anna Glombiewski J. The role of expectations in mental disorders and their treatment. World Psychiatry 2017;16:210–1. 10.1002/wps.20427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Külz AK. Functional analysis in behaviour therapy. Verhaltenstherapie 2014;24:211–20. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wittchen HU, Wunderlich U, Gruschwitz S, et al. SKID. strukturiertes klinisches interview für DSM-IV, achse I, deutsche version 1997. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C, et al. BDI II. beck-depressions-inventar. auflage. London: Pearson, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmidtke A, Fleckenstein P, Moises W, et al. [Studies of the reliability and validity of the german version of the montgomery-asberg depression rating scale (MADRS)]. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr (1985) 1988;139:51–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leiner DJ. SoSci survey (version 3.1.06) [computer software]. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stenzel NM, Fehlinger T, Radkovsky A. Fertigkeitstrainings in Der verhaltenstherapie. Verhaltenstherapie 2015;25:54–66. 10.1159/000380773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stenzel N, Krumm S, Hartwich-Tersek J, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with increased skill deficits. Clin Psychol Psychother 2013;20:501–12. 10.1002/cpp.1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fehlinger T, Stumpenhorst M, Stenzel N, et al. Emotion regulation is the essential skill for improving depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 2013;144:116–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hautzinger M. Kognitive verhaltenstherapie bei depressionen. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Faßbinder E, Jan Philipp K, Valerija S, et al. Therapie-tools depression: mit E-book inside und arbeitsmaterial. 2015: Beltz, [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schaub A, Roth E, Goldmann U. Kognitiv-psychoedukative therapie zur bewältigung von depressionen: ein therapiemanual. Hogrefe Verlag, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schmitz N, Hartkamp N, Kiuse J, et al. The symptom check-list-90-R (SCL-90-R): a German validation study. Qual Life Res 2000;9:185–93. 10.1023/a:1008931926181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bassler M, Potratz B, Krauthauser H. Der “helping alliance questionnaire” (HAQ) von luborsky. Psychotherapeut 1995;40:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86. 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gräfe K, Zipfel S, Herzog W, et al. Screening psychischer störungen MIT dem “ Gesundheitsfragebogen für patienten (PHQ-D) “. Diagnostica 2004;50:171–81. 10.1026/0012-1924.50.4.171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krueger C, Tian L. A comparison of the general linear mixed model and repeated measures ANOVA using a dataset with multiple missing data points. Biol Res Nurs 2004;6:151–7. 10.1177/1099800404267682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goldberg D, Fawcett J. The importance of anxiety in both major depression and bipolar disorder. Depress Anxiety 2012;29:471–8. 10.1002/da.21939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Norcross JC, Wampold BE. What works for whom: tailoring psychotherapy to the person. J Clin Psychol 2011;67:127–32. 10.1002/jclp.20764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer B. Ein jahr nach der reform der psychotherapie‐richtlinie – wartezeiten 2018. 2018. Available: https://www.bptk.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20180411_bptk_studie_wartezeiten_2018.pdf

- 88.Brakemeier E-L, Wirkner J, Knaevelsrud C, et al. Die COVID-19-pandemie ALS herausforderung für die psychische gesundheit. Zeitschrift Für Klinische Psychologie Und Psychotherapie 2020;49:1–31. 10.1026/1616-3443/a000574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-065946supp001.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)