Introduction

Obesity is a clinical and public health epidemic. In most populations, women contribute more to the prevalence of obesity in adults than their male counterparts. The biopsychosocial changes experienced during various stages of the reproductive cycle might implicate excessive weight gain in women.[1] One such high-risk reproductive stage for gaining weight is the menopause transition experienced during midlife. In addition to biological transition, midlife women experience changes in their everyday lifestyle-related habits in a way that might promote unhealthy eating habits, sedentary lifestyles, and distress in the face of household and work responsibilities.[2] Further, weight gain promotes menopausal symptom severity, making it difficult to maintain healthy lifestyle-related behaviours and health-related quality of life.[3]

The introduction of corrective lifestyle-related habits has proven beneficial in managing weight and menopausal health.[4] Corrective lifestyle habits such as healthy dietary behaviour, physically active lifestyle, and psychological well-being are necessary for successful weight management. Most midlife women lack the motivation to initiate corrective practices as they prioritise their roles as mothers, homemakers, and workers over their own health. Besides, factors including poor musculoskeletal health, limited physical function, menstrual irregularities, and psychological distress interfere with adopting healthy lifestyle practices.[5] Considering these factors, it becomes necessary to incorporate strategies to address midlife-specific barriers while managing obesity in this group of women to initiate and sustain weight loss efforts.

Generally, midlife women receive generic weight management advice from healthcare professionals.[6] This advice is less actionable, so it rarely contributes towards correcting the existing lifestyle-related behaviours in midlife women. In contrast, comprehensive obesity care also lacks specificity to address issues faced by midlife women in managing weight and overall health. This care can be provided by a team of clinicians such as gynaecologists, physicians, and allied healthcare professionals, including nutritionists and exercise physiologists. The availability of such a team in the healthcare setting might be limited, especially in developing countries.[7] This underscores the need for the development of evidence and consensus-based recommendations related to diet, physical activity, and behaviour, which can be used by clinicians and/or any other healthcare provider for opportunistic management of overweight and obesity in midlife women.

Methods

The development and validation of the guideline were initiated to address the need for protocolised weight management measures specific to midlife women that can be implemented in day-to-day clinical practice at different healthcare settings. The guidelines were developed in two phases using standardised methodology as per the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC): (i) development of recommendations and (ii) validation of the developed recommendations. Firstly, an exhaustive list of key clinical questions through literature search, expert opinion, and Delphi method was identified to be addressed by the guideline. In Phase I, a systematic review of the evidence, grading, and expert opinion were undertaken to formulate clinical practice recommendations for each clinical question. In Phase II, the clinical practice recommendations were peer-reviewed and validated using the Delphi method and graded using the GRADE approach via the experts participating in the Guideline Development Group (GDG).

Guideline Development Group (GDG)

Expert representatives from multidisciplinary fields including medicine, gynecology, psychology, psychiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, nutrition, and exercise physiology were part of the GDG. Further, chairperson and field experts from prominent national organisations such as the Department of Science and Technology, the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India, Indian Menopause Society, Association of Physicians of India, Academy of Family Physicians of India, Association of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists of Delhi, Indian Dietetic Association, and the Indian Society of Clinical Nutrition also participated in the GDG. From academia, senior professors across five leading medical colleges of the country participated in the proceedings of GDGs. The role and responsibilities of a member of the GDG included finalisation and prioritisation of key clinical questions to be addressed in guideline, review of the available evidence, providing expert opinion, development of the recommendation for each clinical question, validation of the developed recommendations, and grading of the final recommendations.

Development and prioritization of key clinical question

Initially, a series of exploratory focus group discussions were conducted to identify the risk factors, barriers, and facilitators for appropriate weight management among midlife women.[8] Secondly, a comprehensive, valid and reliable screening tool was designed to evaluate the lifestyle-related practices and barriers faced in maintaining healthy eating, physical activity, and sleep practices. Finally, a cross-sectional survey on 504 midlife women was conducted to identify the daily lifestyle-related patterns and their association with menopausal symptom severity. These steps guided the team in identifying key critical areas that should be addressed for appropriate weight management in midlife women. In addition, an exhaustive literature review was conducted to determine key clinical areas of interest for translation into key clinical questions. Based on the stages of weight management, a comprehensive list of key clinical questions was classified into four domains: (i) initiation of discussion for weight management, (ii) screening and risk assessment of the target population, (iii) management of weight, and (iv) follow-up for weight sustenance. A series of online meetings with GDG were organised to prioritise and finalise the list of key clinical questions that can be addressed in this guideline document. The list of key clinical questions was peer-reviewed for its necessity in clinical practice, relevance, face, and content validity under two levels. At the first level review, key clinical questions were reviewed, modified, and finalised by a group of four to five topic-specific experts. The modified clinical questions were subjected to a second-level peer-review done by a larger group of experts, including experts from different disciplines, journal editors, and senior professors from leading organisations. Finally, 19 key clinical questions were prioritised for appropriate midlife health care.

Review of evidence to answer the clinical questions

To develop the recommendations, an exhaustive and systematic literature review was conducted independently for each clinical question.

Search for evidence: A search string was developed for each clinical question. The keywords related to each clinical question were identified through initial literature search, recommendations from experts, and discussion amongst the evidence review team. Three electronic databases (PubMed, Wiley, and Cochrane) were searched to extract relevant evidence.

Selection criteria: Studies published in peer-reviewed English-language journals and on human participants were selected. Methodological filters related to the study design were not applied at this stage to ensure an extensive and exhaustive search. The evidence team further performed the title, abstract, and full-text screening of articles. Any disagreements on selecting a manuscript were resolved by consensus among the evidence team members.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion Criteria: Existing practice guidelines, position statement, consensus statement, systematic reviews on weight management and menopausal health and randomised control trials (RCT), experimental and observational studies recruiting midlife women at different menopausal stages, i.e. perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause were included.

Exclusion Criteria: Studies reported in non-English language, published in non-peer-reviewed journals, and with limited access were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis: The following study characteristics were extracted: year of publication, country, author, study design, sample size, and sample characteristics specific to the clinical question. The findings of the studies were reported in tables to form a write-up for a summary statement.

Development of clinical practice recommendations

The extracted high-quality data for each clinical question was presented with a summary of evidence supplemented by a narrative table. The evidence was circulated amongst the experts for evaluation to form necessary clinical practice recommendations. Experts were given the training to develop recommendations through online meetings on the following criteria: reviewing evidence, formulating evidence-based recommendations, providing expert opinion, reaching a consensus whenever there is a lack of evidence, and grading the recommendation based on quality. This led to the development of two types of recommendations that is, Recommendations Based on Evidence (RBE) and Recommendations Based on Opinion (RBO). The developed recommendations were subjected to a two-level peer-review process. The first review was conducted by a small group of topic-specific experts, and the second review with a large group of experts, including field experts, academicians and journal editors.

GRADE approach

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) evidence profile was constructed to determine the quality of evidence obtained for clinical questions [Tables 1 and 2]. Four grades: high, moderate, low, and very low were used to rate the quality of evidence.[9]

Table 1.

Quality of evidence

| Quality of evidence | Description |

|---|---|

| I | High-quality evidence |

| Based on evidence gathered from the literature search, there is substantial certainty that the true effect lies within the estimated effect. | |

| The high-quality evidence will include: | |

| (i) Well-designed and executed randomised control trials (RCTs) consisting of adequate randomisation, allocation and blinding, sufficient power and intention-to-treat analysis, and adequate measures for follow-up | |

| (ii) Meta-analysis including high-quality RCTs is also included | |

| (iii) Previously published good quality recommendations/consensus statements and/or position statements were given by an organisation or working group consisting of experts in that field. The quality of the recommendations should be established on the basis of the Appraisal Guideline for Research and Evaluation[6] | |

| II | Moderate quality evidence |

| Based on evidence gathered from the literature search, it is possible that the true effect lies close to the estimated effect. The moderate-quality evidence includes: | |

| (i) Well-designed and executed RCTs with minor methodological limitations impacting the confidence in the estimated effect | |

| (ii) Quasi-randomised trials with good methodological quality | |

| (iii) Systematic and meta-analysis of low-quality RCTs with limited quality | |

| III | Low-quality evidence |

| Based on the evidence gathered from the literature search, there is little certainty that the true effect is close to the estimated effect. | |

| The low quality of evidence includes: | |

| (i) Well-designed and executed RCTs with major methodological limitations affecting the confidence in estimated effect. | |

| (ii) Well-designed and executed non-randomised trials including intervention studies, cohort, and quasi-experimental studies, case-control studies with minor methodological limitations | |

| (ii) Observational studies with minor methodological limitations | |

| IV | Expert opinion |

| Very uncertain that the true effect is close to the estimated effect. | |

| Based on clinical experience, reasoning, and suggestions. | |

| There might be a small net benefit from the suggestion. Based on the feasibility, healthcare providers may incorporate the suggestion for weight management. |

Table 2.

Grades for the strength of recommendation

| Strength of recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Strong recommendation: |

| Quantum of benefit expected >>> Resource requirement/logistic needs | |

| Certainly, the net benefits, (i.e. the benefits in comparison to resources required/logistics needed for the service/intervention) outweigh the resource requirement for achieving optimal weight loss outcome. | |

| Clinicians and allied healthcare providers should universally adopt these recommendations as a standard practice to prevent and manage overweight and obesity in women at an individual, clinical, and public health level. | |

| B | Moderate recommendation: |

| Quantum of benefit expected >> Resource requirement/logistic needs | |

| It is moderately certain that the net benefit from the recommendation is moderate to substantial. | |

| These recommendations might not be a mandatory part of a standard weight management clinical practice; however, their implementation can prove beneficial in attaining significant weight loss outcomes. The implementation of these recommendations should be as per an individual’s preference, values, and settings. | |

| C | Weak recommendation: |

| Quantum of benefit expected > = < Resource requirement/logistic needs | |

| It is at least certain that there might be a small net benefit from the recommendation. | |

| These recommendations should be incorporated on the basis of resource availability, feasibility, cost-effectiveness and acceptability in the weight management program. |

Results

Section I: Initiation of discussion for weight management

1.1 When should a healthcare provider initiate structured counselling regarding weight management in midlife women?

Background

The menopausal transition is marked by the onset of irregularity in the menstrual cycle and menopausal symptoms, including hot flushes, physical decline, and emotional volatility.[2,10] In midlife, chronological ageing coupled with menopausal transition leads to several biological changes predisposing women to weight gain. The independent and interactive contribution of increasing age and menopausal transition remains debatable. Nevertheless, both these factors impact the daily lifestyle behaviours, including eating, activity, and sleep habits of midlife women in a way that might make them prone to excessive weight gain.[6] There is a need to understand at which stage during the menopausal transition should weight gain be identified as a potential detriment to the overall health and quality of life. Identifying these critical phases during midlife can help in the early initiation of weight management support by the healthcare provider.

Summary of evidence

In India, the mean age of initiation of the menopausal transition is 44 years, whereas 46 years is the mean age at menopause, which is lower than Caucasian women.[11] Similar findings are reported by a systematic review reporting that the age at menopause was 46.24 ± 3.38 years in Indian women.[12] Further, the mean age of early menopause due to premature ovarian insufficiency was 38 years, and late menopause was beyond 54 years. Some studies reported a positive association of menopause with an overall increase in body weight status.[13,14] However, a direct association of the overall increase in the weight status with hormonal changes during the menopausal transition could not be established. Menopause transition was related to an increase in visceral adiposity.[15,16] Women experienced a steady increase in weight and body fat during perimenopause and menopausal phases. During the menopausal transition, the accelerated gain in fat mass doubled, whereas a decline in lean muscle mass was observed. The rate of change in the body weight and fat accumulation stabilised before initiation of the post-menopausal phase.[17] Postmenopausal women with overweight and obesity have shown greater circulating estrogen levels than non-obese counterparts. This increase in estrogen is contributed by the peripheral aromatisation of the androgens in adipose tissues. It was previously hypothesised that excessive circulating estrogen levels are beneficial for maintaining menopausal and metabolic health. However, recent studies found out that the increase in estrogen levels is not associated with the protective cardiometabolic effects.[16]

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1.1 | Opportunistic screening and management of obesity should be delivered all through the lifespan of a woman. | IV A |

| 1.1.2 | In the late 30s, before menopause transition, women should be counselled about the added risk of menopause-related weight gain and body fat distribution. Opportunistic screening and management of obesity should be continued. | II A/B |

| 1.1.3 | In the early 40s, when women experience menopausal transition, intensive customised weight management counselling should be given. The emphasis should be on corrective lifestyle behaviour and handling health issues specific to menopausal transition such as menopausal symptoms, sleep disturbances, psychological distress, bone and joint health and other comorbidities. | II A |

Discussion

There is a lack of consistent literature on the independent and interactive nature of chronological ageing and menopausal transition on the weight status of menopausal women. Considering the mean age at menopause as 46 years, it is crucial to engage midlife women in weight regulation before menopausal transition.[11] Ideally, opportunistic screening and management should be delivered across the women’s lifespan (as presented in Table 1.1.1). Similarly, as per the Anklesaria staging menopausal system, at stage 1 during the perimenopausal phase, the advice should be shared to create awareness and manage obesity and other menopause-related health risks amongst midlife women.[18] In the later 30s, women should be made aware of experiencing a probable increase in their weight and total body fat status with the onset of the menopausal transition. At this phase, the healthcare providers should counsel women regarding the changes in the menstrual cycle and its probable association with weight gain. Because the age at menopause can vary amongst women belonging to different population groups, the experts have given a dual strength of recommendation to this clinical practice. In the late 40s, an opportunistic screening of weight and health status, followed by customised weight management, should be initiated and continued with the aim of achieving normal weight status. The healthcare provider should advise dietary and physical activity modifications using behavioural techniques for managing weight. In addition, other menopause-related health issues, including psychological distress, sarcopenia, and bone health, should also be addressed during weight management. It should be noted that the evidence for the recommendations mentioned above is derived mainly from studies on midlife women in the west. To our knowledge, there are no longitudinal studies that assess the changes in weight status and body composition during the menopausal transition in midlife women from India. The association of menopausal transition (independent of chronological ageing) and weight status needs to be assessed for the engagement of Indian women in weight-management practices. Thus, the recommendations should be revisited and revised every 5 to 10 years in the face of new evidence on the age of menopause in Indian women, changes in body composition during menopausal transition, and effective weight management practices.

Table 1.1.1.

Opportunistic screening and management of weight during reproductive stages

| Reproductive stage | Key opportunities to screen and discuss weight |

|---|---|

| Adolescents | Engagement in school, family, and community-based health education programs |

| Screening of adolescent visiting regarding other health conditions for weight status (as a vital clinical sign) at clinical set-ups (Criteria: overweight: BMI ≥85th percentile, obese: <95th percentile) | |

| Adolescent girls presenting with obesity-related complications such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and metabolic disorder should be enrolled in a multidisciplinary program | |

| Pregnancy and delivery | Weight counselling during regular antenatal check-up |

| Gynaecologists should counsel women regarding postpartum weight retention and its health risk | |

| Encouraging women to enrol in post-delivery weight management program | |

| Postpartum | Post-delivery weight management programs as part of future gynaecologist visits |

| Promotion of breastfeeding as a preventive strategy for post-partum weight gain | |

| Paediatrician involved in immunisation of child should reinforce weight management | |

| Support groups: Discussion weight control during post-pregnancy | |

| Premenopausal | Screening of women at clinical set-ups for weight status (as a vital clinical sign) |

| Engagement in community and workplace weight management programs | |

| Referring women with obesity and associated metabolic complications to specialist or multidisciplinary teams | |

| Menopausal transition | Screening midlife women at different clinical departments such as medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, orthopaedics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and endocrinology |

| Engagement in community and workplace-specific healthcare intervention | |

| Provision of screening at religious centres | |

| Referring women with obesity and associated metabolic complications to specialist or multidisciplinary teams | |

| Post-menopausal | Screening of midlife women at different clinical departments such as geriatric medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, orthopaedics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and endocrinology |

| Engagement in community-based healthcare intervention | |

| Referring women with obesity and associated metabolic complications to specialist or multidisciplinary teams |

1.2: What are the components of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) that should be evaluated to plan a personalised weight management intervention in midlife women?

Background

The successful management of obesity and other lifestyle-related disorders depends on adopting behavioural techniques for correcting eating, activity, and other lifestyle-related habits.[19] The behavioural practices are motivated by pre-existing knowledge and attitude of an individual. In the literature, knowledge is defined as information and skills acquired using experience and education. Attitude is a value, belief, and feeling that predisposes an individual towards a particular behaviour and behavioural practices are habits and patterns associated with the maintenance of weight status.[20,21] KAP assessment is common in lifestyle-related diseases in clinical and community settings.[22] The clinician needs to understand the KAP of midlife women that promotes obesity. The KAP of core components associated with obesity in midlife women should include lifestyle practices, menopausal symptoms, bone health, and psychological distress.[2] Generally, the KAP can be assessed before the initiation of lifestyle management to identify the risk factors specific to middle-aged women that the clinician should attempt to modify during weight management. A few qualitative studies and cross-sectional surveys have independently assessed KAP for different obesity-related factors in midlife women.[23-25] In qualitative studies, the influence of social, cultural, and economic constructs on obesity-related behaviours has been highlighted. Across cross-sectional studies, KAP was assessed using self-developed or validated questionnaires that rate an individual’s competence in the three domains and correlate with weight and metabolic status.[26-28] A comprehensive assessment of KAP on lifestyle practices, menopausal symptoms, bone health, and psychological distress as risk factors for obesity in midlife is lacking in the current literature. Hence, this clinical question addressed the present evidence on KAP of critical components associated with the management of obesity in midlife women to deliver women-centric management of obesity.

Summary of evidence

The critical components evaluated for the initiation of management of obesity in midlife women included: weight and health-related measures, menopausal symptoms, bone health and psychological distress. The KAP of these components is considered necessary for customising the weight management regime for a midlife woman.[24,28-30] For weight and lifestyle-related parameters, women reported a lack of knowledge regarding corrective weight-related practices, lack of time, social eating, indulging in high-fat, sugar, and salt foods (HFSS), and reduced daily activity, led to obesity.[31,32] Four studies reported the interplay between the menopausal symptoms severity and psychological distress, leading to the consumption of energy-dense foods and limited physical activity in midlife women. The difficulty in sleeping due to hot flashes and mood disorders was associated with weight gain in midlife women.[33-35] Menopause led joint pain was the primary reason for limited participation in dedicated physical activity. Moreover, women had limited knowledge regarding age-related osteoporosis and measures that can be taken to maintain bone health such as getting a regular bone check-up, consuming foods rich in calcium, and consulting doctors for guidance on supplementation such as vitamin D and calcium for bone health.[27,30] In addition to limited knowledge, most women prioritised their roles as homemakers, working women and child care providers over their own health issues.[36,37] This self-sacrificing attitude coupled with limited support from family and friends in maintaining health-related behaviours in their day-to-day lifestyle should also be addressed for maintaining continuous and sustainable efforts for weight management and allied comorbidities.[24,36]

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2.1 | Assessment of KAP related to risk factors and consequences of obesity on the holistic health of women is recommended. | III A |

| 1.2.2 | Different modalities for weight management, barriers, and facilitators in their implementation should be evaluated and accounted for in the management plan. | III B |

Discussion

A comprehensive assessment of KAP should be done to identify key areas that the interventionist should attempt to modify during lifestyle intervention to achieve clinically significant weight loss. The recommendations were based on well-known, lifestyle and midlife-related risk factors experienced during the menopausal transition. However, the evidence was from independent studies on a particular risk factor (e.g., diet, mental health, joint health etc.). There were no data on a comprehensive assessment of KAP related to risk factors of obesity in midlife women, which would be relevant to guide future clinical and research practice. Besides, the effectiveness of KAP in providing customised weight management advice for achieving significant weight loss should be assessed using longitudinal studies or RCTs in future research. Considering the importance of KAP in customising weight management approaches in midlife women, experts agreed that a comprehensive assessment of KAP as a component of risk assessment of obesity in midlife women should be incorporated into clinical practice (shown in Table 1.2.1). Based on available resources in the healthcare or community setting, healthcare professionals can assess KAP via history taking, group discussions and/or interview schedule with a structured questionnaire. The key questions that can be assessed in resource-constrained settings are presented in Table 1.2.2.

Table 1.2.1.

KAP regarding obesity, associated risk factors for weight gain, and appropriate weight management in midlife women

| Knowledge | Attitude | Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge associated with vegetables and fruit consumption Awareness of weight gain and health Osteoporosis and its complications Calcium-rich dietary sources Perceived benefits of exercise, adequate calcium intake, regular physical activity, dairy intake Management of menopausal symptoms Contraception use and weight gain |

Easy to gain weight but difficult to lose Dissatisfaction with one’s appearance Body shape concerns Self-rated physical health Attitude towards menopause Health motivation |

Sedentary lifestyle Not engaging in any exercise Eating during socialisation High calorie and fat intake Having limited free time to manage diet and exercise Limited dairy intake Stress-eating Regular health check-ups Regular visits to the gynaecologist Maintaining menopausal hygiene Self-management of menopausal symptoms |

Table 1.2.2.

Questions for assessment of KAP regarding obesity in midlife women

| Domains | Key questions that can be enquired while initiating clinical management |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | How can obesity cause health-related complications in midlife women? What are the common menopausal symptoms and how can you manage them? What is the importance of bone health during the menopausal phase? What lifestyle modifications should you incorporate into your daily routine to avoid weight gain? |

| Attitude | How motivated are you to participate in a weight management program at this stage of your life? How ready are you to change your current dietary and physical activity habits at this point in time? How do you feel about your menopausal health during the transition? |

| Practice | What are the different food items that you usually consume in a day? What kind of activities do you participate in on a regular day? How do you maintain your bone health? What are common measures that you adopt for the management of menopausal symptoms? How do you cope with emotional distress? |

*These questions should be asked as an opportunity to initiate discussion. Healthcare providers should supplement the information received from these questions with appropriate facts through objective diagnosis and assessment, if and when required.

1.3 Which healthcare providers can be involved in the management of overweight and obesity in midlife women?

Background

Obesity is a complex and multisystem disorder.[38] According to the international guidelines, preventive and curative obesity treatment should be delivered to individuals across the healthcare system.[39] The comprehensive treatment of obesity and allied complications requires a multicomponent and multidisciplinary approach. A multidisciplinary approach manages treatment components with the help of different healthcare professionals including a primary care physician, family physician and/or a gynaecologist with expertise in pharmacotherapy, an exercise physiologist, a dietitian, and a psychologist to provide comprehensive weight management counselling.[40] Despite the consensus on promoting multicomponent and multidisciplinary approaches amongst obesity experts, there are no specific guidelines or position statements on the operationalisation of these treatment modalities in daily clinical practice.[41] The limited application of multidisciplinary approaches can be due to limited healthcare resources such as a low doctor-to-patient ratio, time constraints, lack of auxiliary healthcare teams, and infrastructure, especially in developing countries.[42] Considering the challenges in the management of obesity in healthcare settings, it becomes essential to identify the roles and responsibilities of clinicians and allied healthcare professionals that can make multidisciplinary teams. Furthermore, these teams should be educated and trained to equip healthcare professionals to assess obesity risk, provide brief weight counselling advice, and referrals specialists at healthcare centres.[43]

Summary of evidence

The comprehensive management of overweight and obesity includes three key components: diet, physical activity and behavioural strategies. In 29 pertinent weight-loss trials, the treatment modalities were managed by either a multidisciplinary team, a core team of two healthcare professionals or single-handedly by a dietitian. In seven studies, a qualified dietitian provided lifestyle counselling to the participants to manage their weight.[44,45,46] As per 11 studies, weight management teams commonly consist of two healthcare professionals from different specialities. Out of 11 studies, nine studies opted for a team of dietitians and exercise experts such as physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, exercise specialists or personal trainers for weight management.[47,48,49] In three studies, lifestyle advice was coupled with behavioural techniques counselled by a team of dietitians and behaviour management experts such as psychologists, behaviour science experts or clinical health psychologists.[50,51,52] It was observed that dietitians are an essential component of all the core teams. Nine studies reported that a multidisciplinary team consisting of a dietitian, exercise physiologist, and behavioural therapist were a part of a comprehensive weight management program.[53,54,55]

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 1.3.1 | The protocolised weight management module should be implemented by any healthcare worker who encounters a woman in her midlife for routine screening or specific health conditions. | IV A |

| 1.3.2 | Wherever feasible, a multi-disciplinary team consisting of primary care physicians, clinicians, dietitians, and exercise physiologists/physiotherapists should be involved in weight management of midlife women. Specialists including psychologists/psychiatrists, endocrinologist and orthopedicians should be involved, whenever indicated. | I A |

| 1.3.3 | All healthcare workers should be empowered with the knowledge and skills for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of obesity in midlife women. | IV B |

Discussion

The effective management of weight in healthcare settings requires a multidisciplinary team. Despite the importance of multidisciplinary teams, the onus of effective preventive and curative obesity care lies on all the healthcare professionals who encounter midlife women with overweight and obesity. Often, midlife women meet primary care physicians and family physicians as the first point of contact in the healthcare system. The incorporation of family care physicians as a part of the core weight management team or an extended weight management team is vital for initiating effective management at the healthcare level. In literature, dietitians-led weight management was most commonly observed across weight-loss trials. The inclusion of dietitians in core weight management teams and/or frequent referrals to dietitians can be helpful to impart detailed lifestyle modification counselling that might not be feasible for a general practitioner or gynaecologist in a busy outpatient setting. Experts believe further attempts can be made based on the available healthcare resources to involve specialists and clinicians such as exercise physiologists, psychologists, and orthopaedics who have decisive roles in obesity management in midlife women. Considering the limited healthcare resources in developing countries such as India, a dedicated multidisciplinary approach can be limited to established tertiary healthcare set-ups. Experts suggest that interprofessional education and training sessions to discuss professional attitudes, skills and barriers faced in everyday clinical practice for obesity management can be the first step to mitigate this resource constraint. Every healthcare provider should be trained in opportunistic screening and generalised management of obesity in midlife women.

1.4: What could be the effective ways of delivering pertinent information to midlife women regarding the management of overweight and obesity?

Background

Health promotion counselling is a feasible, cost-effective and long-term solution for the effective management of obesity. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2013) recommendations refer to the importance of health promotion and lifestyle advice to identify, assist and treat individuals with obesity.[56] The lifestyle counselling paradigm has evolved over the years from personalised counselling sessions to web-based interventions.[57,58] Personalised counselling can be defined as one-to-one counselling sessions with trained healthcare providers focused on managing an individual’s weight-related issues.[59] Group counselling provides an opportunity to discuss and share similar weight-related concerns amongst a group of participants in the presence of trained healthcare professionals in a real social setting.[60] In the current clinical practice, the traditional one-to-one counselling is supplemented with web-based interventions that help in improving compliance to the lifestyle advice by providing personalised feedback and addressing challenges in real-time.[61] Web-based counselling utilises technological components such as the internet, mobile application and online social support groups to counsel women on weight-related issues.[62] Nowadays, web-based counselling techniques have replaced the non-digital formats for nutrition education consisting of patient education material such as pamphlets, brochures, and e-newsletters. However, there is limited evidence on the mode of lifestyle counselling (independent or in combination) that will effectively manage weight in midlife women. Further, healthcare professionals need to understand the most effective and promising way of delivering information for counselling on weight management components (diet, physical activity and behaviour) for widespread acceptance of advice. To date, the role of different counselling techniques and modalities of communication in improving odds of achieving successful weight loss and prevention of weight gain remains unclear. Hence, this clinical question was undertaken to identify the most promising ways of counselling and delivery of patient education advice for effective management of obesity in clinical and community settings.

Summary of evidence

The pertinent studies identified used a range of counselling techniques, including personalised counselling sessions, group counselling, telephonic counselling sessions, or a combination to achieve significant weight loss. A systematic review comparing the role of group and individualised counselling for weight management reported that group counselling led by a psychologist was more effective for female participants.[63] It was also reported that in-person and more frequent contact were not associated with more significant weight loss.[64] In addition to these techniques, web-based counselling sessions were also opted for weight management. Four meta-analysis and systematic reviews assessed the role of technology-based interventions suggesting different web-based interventions were minimally effective in weight management. In comparison to traditional personalised counselling techniques, the efficacy of the web-based intervention was inconsistent.[65] A recent systematic review suggested that web-supported video conferencing sessions are effective in maintaining physical activity.[58]

In addition to counselling, various forms of nutrition education material have been used across trials to facilitate weight loss. Education material such as printed material, exercise videos and mobile application for self-monitoring is available.[44,66,67] A systematic review has reported that dietary counselling was mostly given as verbal advice coupled with handouts/brochures. There were no referrals for comprehensive weight management to the dietitians. Three-fourth of the participants were advised to walk for physical activity without providing any tailor-made activity plan.[68] It was suggested that a toolkit approach should be undertaken, including evidence-based and practical dietary, physical activity, and behavioural advice.

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 1.4.1 | A combination of face-to-face and technology-supported distance counselling should be planned for the management of weight in midlife women with overweight and obesity. | IV A |

| 1.4.2 | Internet and mobile-based applications should be used proactively for improving compliance by enhancing patient education, motivation, self-monitoring, personalised feedback, and managing challenges faced in appropriate weight management practices. | II A |

| 1.4.3 | A toolkit consisting of education material apprising midlife women about menopausal transition and its impact on weight status and key management strategies can be developed to be distributed and utilised across healthcare settings. | IV B |

Discussion

A combined counselling regime consisting of individualised and internet-based distance counselling sessions can help to improve the odds of achieving weight loss success in the general population and midlife women. Experts believed that healthcare providers should decide the mode of counselling based on several factors, including infrastructure, availability of resources, the expertise of the healthcare provider, clinician to patient ratio, and characteristics of the patient attending healthcare settings. It is important to note the advantages and disadvantages of each counselling method, education tools to customise the weight management approach (as depicted in Table 1.4.1 and 1.4.2). The experts recommended a uniform toolkit approach to provide nutrition, physical activity and behavioural strategies for management of weight in midlife women across health care settings. This toolkit should include health education material that can be easily used for counselling by allied healthcare professionals, especially in rural settings. Currently, social media has been identified as an upcoming cost-effective tool for increasing patient engagement, health promotion and social support at an individual and community level.[69]

Table 1.4.1.

Advantages and disadvantages of counselling techniques

| Counseling technique | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Individualised counseling | One-on-one attention | More expensive |

| Intense and comprehensive therapy | Lack of social support | |

| Focused and tailored treatment | Requires human resource | |

| Personalised feedback | Time intensive | |

| High level of confidentiality | ||

| Group counseling | Cost-effective | Requires space |

| Social support | Limited opportunities for managing more specific | |

| Resource-saving | individual needs | |

| New perspectives and diversity in opinion | Less confidentiality and trust | |

| Social support | Hesitancy | |

| Less focus and attention towards each individual | ||

| Web-based counseling | Cost-effective | Limited opportunities for attending to more specific |

| Time-efficient | individual needs | |

| Enhanced availability and easy accessibility | Data security issues | |

| Improved adherence | Lack of non-verbal signals | |

| Long-term efficacy | Need of technology | |

| Privacy and anonymity | Low need or desire for in-person contact | |

| Close contact with a healthcare professional at any time | ||

| Improved discretion and comfort | ||

| Reduced barriers related to patient disengagement, | ||

| geographical distance, socioeconomic status | ||

| Mass awareness | Cater to a broad-range audience | Lack of non-verbal signals |

| Cost-effective | Need of technology | |

| Time-saving | Lack of effectiveness | |

| Social support | No long-term effect | |

| Bridge geographical distance | Less opportunity for individual needs | |

| Anonymity |

Table 1.4.2.

Advantages and disadvantages of various modes used for counseling

| Modes used for counselling | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Posters, brochure, pamphlet and leaflets | Cost-effective | No long-term effect |

| Easy to distribute | ||

| Time-saving | ||

| Connect with the target audience | ||

| Informative | ||

| Presentations and videos | Broad population reach | Limited interaction |

| Informative Easily accessible | ||

| Cost-effective | Requires time for planning and content | |

| Social media | Easy access | Lacks social-emotional connection |

| More flexibility | Availability and varied understanding of | |

| Anonymity | technology | |

| Cost-effective | Lacks feedback and follow-up | |

| Wider reachability | ||

| User friendly | ||

| Language friendly | ||

| E-counselling tools: websites, e-mail, group chat | Accessible | Time-delayed format |

| Convenient | Absence of visual and vocal cues | |

| Cater to masses as well as individuals | Greater potential for misinterpretation | |

| Bridge geographical distance | Varied understanding of technology | |

| Increased follow-up | ||

| Video conferencing | Accessible | Availability of technology |

| Convenient | Decreased sense of intimacy | |

| Real-time | ||

| More privacy | ||

| Bridge geographical distance |

Section II: Screening and risk assessment of midlife women

2.1: What BMI cut-off and other anthropometric parameters should determine the need to initiate weight management intervention in midlife women?

Background

Body mass index (BMI) is a universally accepted method for diagnosing overweight and obesity.[70] BMI is an index of weight and height, expressed as kg/m2. Ideally, BMI is used as a measure of adiposity. The internationally accepted BMI cut-offs and corresponding components of body weight (body fat, muscle mass and total water) are known to vary in different ethnic communities.[71] Because the internationally accepted BMI cut-offs are based on data from the western population, ethnic variation in BMI cut-offs for Asian Indians should be addressed. In addition to BMI, other anthropometric parameters such as waist and hip circumference and their ratios such as waist to height ratio (WHtR) and waist to hip ratio (WHR) can be used for the assessment of generalised and central obesity. Waist circumference and its ratios are important anthropometric parameters associated with visceral adiposity and cardiometabolic health.[72] In resource-rich settings, methods such as Bioelectric Impedence Analysis (BIA) and Dual X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) can be used for objective assessment of total body fat, skeletal and lean muscle mass.[73] The choice of anthropometric measure opted for diagnosis is dependent on several factors including technical know-how, availability of instruments, healthcare personnel, infrastructure, and the clinician to patient ratio. It is important to identify anthropometric parameters, which are simple, feasible, cost-effective and efficacious in identifying generalised and central obesity status in clinical practice.

Summary of evidence

The optimum BMI coupled with waist circumference cut-off has been identified across the literature to diagnose overweight and obesity. Globally, for the categorization of BMI, World Health Organisation (WHO) suggests an individual with a cut-off of 25–29.9 kg/m2 as overweight and ≥ 30 kg/m2 as obese. It was identified that the globally recommended cut-off for defining overweight and obesity should be lowered in different Asian population groups due to ethnic variation in the total body fat and fat-free mass. The Indian Consensus Group (2009) recommended a cut-off value of 23–24.9 kg/m2 as an indicator of overweight individuals and ≥25 kg/m2 as an indicator for obese individuals.[74] Across literature on lifestyle modification in menopausal women, the BMI range was 23–45 kg/m2.[75,76,77]

In addition to BMI, the consensus statement from a working group reported that waist circumference should be made a vital sign for clinical assessment.[72] According to the WHO, women with waist circumference > 88 cm can be at risk of at least one cardiometabolic risk factor.[78] For Asian Indians, a woman > 80 cm waist circumference should seek help from a healthcare practitioner for management of obesity-related risk factors and women with waist circumference > 72 cm should avoid gaining weight and incorporate physical activity to avoid having any cardiometabolic risk factor in later life.[74] We found six trials that assessed the waist circumference at the baseline. Out of which, four studies defined the waist circumference cut-off as 80 cm and two studies defined waist circumference cut-off as 88 cm.[79,80,81,82] We found three studies assessing baseline total body fat for midlife women enrolling in lifestyle modification intervention, with a cut-off of more than 32% in one study[83] and more than 35% in one RCT and systematic review. Only four studies assessed the total body fat percentage at the baseline in midlife women undergoing weight loss intervention.[75,79,83]

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1.1 | BMI and waist circumference should be used independently for population- and clinic-based cardiometabolic risk stratification and other obesity-related diseases. | I A |

| 2.1.2 | For initiating a weight management intervention, the class of generalised obesity should be identified according to the BMI-cut-off 18.5-22.9 kg/m2: Normal weight 23.0-24.9 kg/m2: Overweight ≥25 kg/m2: Obesity |

I A |

| 2.1.3 | For initiating weight management intervention, the cut-off for waist circumference should be as below: Waist Circumference less than or equal to 72 cm: normal Waist Circumference more than 72 cm but <80 cm: associated with one cardiometabolic risk factor-initiate weight management advice Waist Circumference more than 80 cm: associated with cardiometabolic comorbidities-initiate intensive weight management |

I A |

Discussion

We found robust evidence that suggests that BMI and waist circumference are associated with risk of general and abdominal adiposity, cardiometabolic risk and obesity-related diseases. The universally recommended BMI values for overweight (≥ 25 kg/m2) and obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2) were established on the basis of morbidity and mortality data from the white adult population.[70] In Asian Indians, higher body fat and higher cardiometabolic comorbidities are observed at a lower BMI status.[84] This raises concerns in clinical practice as these individuals who are metabolically obese and predisposed to developing hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, blood pressure and atherosclerosis are misclassified as individuals with normal BMI. Considering a greater cardiometabolic risk at a lower BMI, a revision of the BMI cut-off for Asian Indians was suggested by national recommendation bodies as 23–24.9 kg/m2 for overweight and 25 kg/m2 or more as obese. It should be noted that clinicians and healthcare providers should classify midlife women according to the Asian Indian specifications in their daily clinical practice, rather than the internationally accepted guidelines.

In addition to BMI, waist circumference should be utilised in the assessment of generalised and abdominal obesity, especially to identify women who are metabolically obese presenting with normal weight (MONW) in clinical settings. These anthropometric parameters can be used to screen women at high risk of cardiometabolic disease and obesity-related disorders for timely initiation of treatment. Considering the importance of waist circumference in assessing cardiometabolic risk factors in an individual, a consensus on cut-offs of waist circumference in the adult population was recommended. For women, a waist circumference of more than 88 cm was considered as an indicator of cardiometabolic risk.[78,85] In Asian women, a waist circumference of 80 cm was considered appropriate in identifying cardiovascular risk factors in comparison to 88 cm, which was internationally accepted.[74] Furthermore, ratios such as WtHR and WHR are used as an indicator of metabolic health. Evidence suggests that waist circumference alone is a vital responsive clinical sign of cardiometabolic health in comparison to WHR.[72]

Experts suggested that measurement of anthropometric parameters BMI and waist circumference should be made a part of routine clinical practice as a vital clinical sign for health assessment of midlife women.

In addition, clinicians should also stratify treatment at different BMI cut-offs for optimal utilization of resources for diagnosis and treatment. The intensity of weight management advice should be in accordance with deviation from the ideal weight and waist circumference. The use of pharmacotherapy should be incorporated in the treatment only as per indications by the treating clinician. In addition to cut-offs, the availability of resources should also be noted while planning obesity care, especially in resource-constrained settings such as anganwadi, community clinics and primary healthcare centres (PHC).

2.2: How should dietary practices of midlife women be evaluated?

Background

The assessment of lifestyle-related risk factors is an important step in managing weight in midlife women. In clinical practice, a detailed dietary history consisting of current caloric intake, adequacy of macronutrient composition (carbohydrate, protein and fat), consumption of HFSS foods, meal pattern, portion size, eating out, and nutritional deficiencies is a common method of dietary assessment.[86] For an objective assessment in terms of quantity and quality, traditional methods such as twenty-four-hour recall and food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) can be administered by trained healthcare professionals.[87] In addition, most weight-loss trials administered valid and reliable questionnaires to assess different aspects of eating behaviour.[45,88-90] The choice of the assessment method depends on a number of factors such as the aim of assessment, the expertise of the healthcare provider, availability of time, participant burden, infrastructure and method of interpretation of collected information. It is commonly observed that a majority of clinicians are involved in general dietary management as a part of midlife care.[2] It becomes important to identify simple, practical and cost-effective ways for dietary assessment, which can facilitate holistic dietary counselling, especially in resource-constrained settings with limited or no availability of a nutritionist or a dietitian.

Summary of evidence

A total of 15 instruments were identified for dietary assessment of the individuals participating in weight-loss interventions. Only one study assessed the dietary quality using the healthy eating index (HEI)-2010.[91] The usual dietary intake of the participants was most commonly assessed at baseline in weight loss trials. A total of nine studies assessed usual dietary intake by administering 24-hour dietary recall (three weekdays and one weekend)[92] Women’s Health Initiative FFQ,[89] Vioscreen (an electronic FFQ),[44] four-day food record[48] and dietary food logs.[83] The frequency, type and distribution of meals were assessed via a meal pattern assessment grid in two studies.[49,89] The frequency of intake of HFSS foods was assessed using two scales including fat-related intake questionnaires,[93] and Connor Diet Habit Survey.[94] The eating behaviour was assessed via a 51-item valid and reliable Three-Factor Eating Behavior Questionnaire(TFEQ) measuring three domains: Cognitive Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger on a four-point Likert scale.[88,95,96] Only two studies measured the barriers faced in maintaining healthy eating in an interview schedule to assess the factors such as emotional eating, daily mechanics of healthy eating and lack of social support on a five-point Likert scale.[97,98]

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2.1 | The detailed dietary evaluation should include an assessment of the usual meal pattern (including the number of food items consumed) and dietary habits (including skipping meals, typical frequency of HFSS usual frequency of eating out, emotional/stressful eating). | I A |

| 2.2.2 | Twenty-four-hour dietary recall and food frequency questionnaire for 3 days (2 weekdays and 1 weekend) should be used for dietary evaluation, if feasible. Energy, macronutrient, fibre intake should subsequently be calculated. Alternatively, a short validated questionnaire can be used.* | II B |

| 2.2.3 | Dietary intake of foods rich in protein, iron, and calcium should also be assessed while taking dietary history. | IV B |

| 2.2.4 | The barriers faced by midlife women to maintain a healthy diet in their daily lifestyle should be enquired. | IV B |

*Refer to Annexure 4.

Discussion

The recommendations were based on guidelines, position statements and RCTs in the general population and midlife women for the management of overweight and obesity. The evidence suggests that assessment of current caloric intake, dietary habits related to health risks (such as sarcopenic obesity, cardiometabolic distress, osteoarthritis), and micronutrient deficiencies is a crucial step in the dietary management for weight loss in midlife women.[99,100] Ideally, midlife women should be referred to dietitians and/or nutritionists to assess current dietary intake using a 24-h dietary recall method coupled with FFQ. For clinicians and researchers interested in utilizing traditional tools for dietary assessment, a detailed description of available tools with their advantages and disadvantages is presented in Table 2.2.1. However, these methods suffer from practical limitations such as the need for technical knowledge, are time-consuming, and are difficult to interpret, especially in resource-constrained settings. Experts believed that a detailed dietary history should be considered a simple, practical and feasible assessment method in daily clinical practice. For ease of practice, the details on specific points to be considered while taking the dietary history are presented in [Table 2.2.2]. Considering the resource availability, practitioners can opt for a combination of methods for dietary assessment that can provide them with complete information on current dietary practices in midlife women. Special attention should be given to assessing the regular consumption of foods rich in protein, iron, and calcium. Healthcare practitioners can assess the intake of foods rich in protein and other micronutrients in two ways: (i) quantitatively via 24-h dietary recall method or a semi-quantitative FFQ and/or (ii) qualitatively via dietary history. In the presence of any clinical symptoms related to micronutrient deficiencies, a detailed clinical history, assessment of clinical signs and confirmatory laboratory tests (if feasible) should be planned under the guidance of a clinician. Diet diversity can also be checked via an easy to administer checklist like the FIGO Nutrition checklist consisting of six questions on consumption of food groups to assess the dietary quality. This checklist can be completed before the doctor’s appointment at the outpatient setting.[101] This checklist can be customised and validated for Indian midlife women.

Table 2.2.1.

Advantages and disadvantages of traditional tools used for dietary assessment

| Tools/Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| 24-h recall (Retrospective assessment method of dietary intake over 24 h) |

Precise method if interviewed efficiently Less burden on the respondent Sensitive to ethnicity Captures eating habits such as meal pattern, preparation methods | Administered skilled interviewer Recall bias Time-consuming Accuracy depends on respondent’s literacy and ability to describe the food and portion size |

| Food frequency questionnaire (Retrospective method Assessment of frequency of foods consumption over time) Types: Qualitative: Frequency of food consumed only Semi-quantitative: Frequency along with portion size consumed, for example, small, average, large Quantitative: Portion size enquired |

Helpful for long term dietary intake estimation Capture food diversity, specific nutrient or food group Less burden on researcher and participant Cost-efficient More accurate and culture-specific Less intensive analysis | Relies on participant’s memory Chances of misreporting May lead to underreporting if the food list is not comprehensive |

| Food diary/records (Record of all food items consumed Amount of food consumed is either estimated or weighed) | More accurate Detailed information on dietary intake Good estimates of short term total dietary intake and total nutrient intake Little reliance on participants’ memory Cost-effective | High participant burden Applicable for trained/literate participant Labour intensive. Time-consuming analysis Chances of misreporting Estimated food diaries rely on one’s ability to describe portion size |

| Semi-quantitative weighed food record (Portion sizes quantified (weight of foods consumed in a day/estimation using household measures)) |

Direct and simple recording of all consumed foods Does not rely on respondent’s memory | High participant burden Accuracy depends on the motivation of the respondent Requires literate/trained participants Time-consuming Can lead to undertreatment |

Table 2.2.2.

Important points of consideration while taking a comprehensive dietary history

| Type of diet: Amount and quality of usual calorie intake should be assessed |

| Meal pattern: Assess eating habits in terms of frequency and timings of the meal consumptions. Unhealthy eating habits such as meal skipping habits, longer meal gaps and energy-dense meals should be marked. |

| Portion size: Estimation of accurate food portions. Identify large portion size, energy-dense products and second helpings. |

| Macronutrient intake: The proportion of fat, protein, fat and fibre intake should be noted. |

| Protein intake: Daily consumption of adequate portions of foods high in protein including legumes, meats, dairy and nuts. |

| Fat intake: Consumption of fried, processed foods and bakery products should be asked along with frequency and portion size. The amount and quality of oil on a daily basis should also be noted. |

| Fibre intake: Fiber intake includes fruits and vegetables, whole grains and legumes and nuts and seeds. |

| Meal preparation: Method of cooking, intake of processed and convenience food items should also be assessed. |

| Eating out habits: Frequency and quality of food consumed outside the home. |

Midlife women presenting with signs and symptoms of iron deficiency anaemia can be assessed through (i) examination of clinical signs and symptoms like pallor of eyelids, tongue, nail beds and palms and (ii) prescribing a complete blood count including assessment of haemoglobin (Hb), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) as a preliminary predictive test.[102] The blood level of serum ferritin is considered the most appropriate test for assessing iron deficiency anaemia.[103] The cut-off values for the assessment of iron deficiency anaemia are given in [annexure 1].

There are no reliable biochemical status markers for the assessment of calcium deficiency in adults.[104] In a resource-constrained setting with limited possibilities of performing a 24-hour recall for assessment of calcium intake, the daily dietary calcium intake can be assessed using a feasible National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) tool (as shown in Annexure 2).[105] The adequacy of calcium intake can be assessed by comparing the calculated daily dietary calcium intake with the recommended daily allowance (RDA). In addition, Vitamin D deficiency can be assessed by testing the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, especially in midlife women presenting with joint and bone-related issues.[104] The cut-offs for the assessment of vitamin D deficiency in adults are presented in Annexure 3.[106]

The final step in dietary assessment is to ascertain the barriers faced by midlife women in managing healthy eating practices in their day-to-day life. These barriers should be considered for providing personlised dietary modification advice. A valid and reliable questionnaire for assessing dietary practices and barriers to healthy eating in Indian midlife women can be accessed from [Annexure 4].

2.3: How should the level of daily physical activity of midlife women be evaluated?

Background

The assessment of daily physical activity status is important for determining the total caloric deficit required for achieving weight loss in midlife women. Daily activity assessment is aimed at calculating caloric expenditure. Daily physical activity can be comprehensively assessed under the following domains: exercise, occupational, household-related, leisure-related and sedentary activities.[107] Physical activity is defined as ‘bodily movement generated due to contraction of the muscle that raises the energy expenditure above resting metabolic equivalents (METs)’. It is generally characterised by type, intensity, and duration. Exercise is a sub-category of activity that is planned, structured and repeated for maintaining physical fitness.[108] Sedentary activities are defined as “any activity with an energy expenditure of ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while in a sitting, reclining and lying posture”.[109] Several methods have been used for objective assessment (accelerometers, heart rate monitors, mobile applications) and subjective assessment (detailed activity history, physical activity questionnaires and activity monitoring applications).[51,110-113] The choice of assessment method in healthcare settings depends on efficacy and ease of use with respect to available time, expertise, and economics. In most healthcare settings, clinicians primarily engage midlife women in considering an active lifestyle. It is important to identify concise, valid and reliable assessment methods that can be taken up by the clinicians and other healthcare professionals for a time-bound and comprehensive assessment of daily physical activity.

Summary of evidence

Across weight-loss trials, daily physical activity was assessed using objective, subjective and a combination of both measures. Objective measures included an accelerometer and pedometer worn on the wrist, waist or hip to calculate the mean physical activity as MET values.[90,111,112] In subjective measures, a total of ten questionnaires were used to assess the total physical activity across different domains such as leisure, occupational, household chores, and sitting and screen time. Five studies assessed physical activity using a combination of objective measures such as accelerometer and subjective measures such as Stanford 7 day Physical Activity Recall, International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), and Minnesota Physical Activity Questionnaire.[110,114,115] The questionnaires evaluating both sedentariness and activity status are IPAQ and Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ).[113,116] Other domain-specific activity questionnaires are the Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire and Allied Dunbar National Fitness Survey for leisure-related physical activity and work and non-work activity by Stanford Physical Activity Recall.[50,117] Sedentariness was measured using low level physical activity recall and Sitting Questionnaire.[118] The assessment can be reported as continuous scores (mean MET values per day or week) or categorical scores as low, moderate and high activity according to the cut-off MET values per day.

It was also observed that physical activity assessment should be done for activities that are specific to geographical, social and cultural constructs. Considering this, the physical activity assessment scale for the western population might not correctly measure the level of physical activity in midlife women in India. MPAQ is a recall measure specifically developed and validated in the Indian population to measure both the level of physical activity in different domains and sedentariness.[119] Although, the application of this measure in a busy outpatient setting is still limited. There is limited evidence on short and comprehensive physical activity assessment tools that can measure the level of physical activity as well as barriers faced by midlife women in managing daily physical activity.

Clinical practice recommendations

| No. | Recommendations | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 2.3.1 | The detailed physical activity evaluation should include an assessment of dedicated physical exercise, domestic, work-related, leisure-related, transport-related and sedentary activities (screen and sitting time). | I B |

| 2.3.2 | Madras Diabetes Research Foundation- Physical Activity Questionnaire (MPAQ) should be used for the evaluation of physical activity, if feasible. Alternatively, a short validated questionnaire can be used.* | II B/C |

| 2.3.3 | Evaluation of the adequacy of physical exercise should be done by assessing: type of exercise (stretching/strengthening/aerobics/balance), intensity (light/moderate/vigorous), frequency (number of days per week) and duration (number of minutes per day). | IV B |

| 2.3.4 | Special attention should be given to assess the number of sedentary hours (especially, screen and sitting time) spent during the day. | IV A |

| 2.3.5 | Midlife women should be encouraged to discuss the barriers faced by them in maintaining an active lifestyle. | IV A |

*Refer to Annexure 2.

Discussion

Physical activity assessment should be made a standard step in routine care to design and promote strategies to maintain an active lifestyle.[120] The recommendations on baseline assessment of physical activity status in midlife women are derived from lifestyle modification RCTs aiming at achieving weight loss. The two methods identified for physical activity assessment are objective (activity monitors: accelerometer, pedometer) and subjective methods (questionnaires and activity history). In public health and clinical settings, subjective methods including self-reported PA questionnaires, daily activity logs and activity history schedules are commonly used to assess the level of daily activities. There is evidence that comprehensive assessment of daily activities across domains including physical activity, household chores, work, transport and sedentary activities is crucial to assess the total daily caloric expenditure.[80] Experts believed that healthcare practitioners should consider the feasibility of the assessment approach before including it in daily clinical practice. Based on resource availability, the assessment can be done using three possible methods of assessment: MPAQ, comprehensive questionnaire and/or detailed activity history. It is important to integrate the physical activity assessment into clinical practice.[121] If the application of the questionnaires is not feasible, some important points of consideration while taking activity history in midlife women are presented in [Table 2.3.1].

Table 2.3.1.

Important points to be considered for physical activity assessment

| Dedicated exercise (moderate to vigorous-intensity activity; such as yoga, aerobics, resistance or strength training exercises for 150 min/week): |

|---|

| •How often do you engage in dedicated physical activity in a week? |

| •How much time duration do you dedicate to participate in exercise? |

| •What types of exercises do you include in dedicated physical activity? |

| Household activities (cooking, cleaning, mopping, gardening, child care etc.): |

| •How often do you participate in household chores in a week? |

| •What household chores do you usually do on a regular day? |

| •How much time do you spend doing household chores in a day? |

| Occupation-related activities (manual tasks, sitting task, walking, working on a laptop, carrying or lifting objects): |

| •How many hours in a day do you usually spend doing sedentary work-related activities (sitting and screen time)? |

| Transport-related activities (self-driving, cycling and walking from one place to another): |

| •What kind of transport do you usually opt for while travelling from one place to another? |

| •How much time do you usually spend travelling? |

| Leisure time activities (discretional or recreational activities including hobbies, walking, gardening): |

| •What type of activities do you usually do in your free time? |

| •How much time do you usually spend on leisure activities? |

| Sedentary habits (includes such as sitting, reclining or lying posture, watching TV, playing video games, or using the computer): |

| •How much is your daily screen and sitting time? |

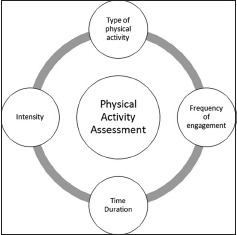

Considering the effect of dedicated activity in maintaining cardiometabolic, bone and cognitive health in midlife women, a detailed investigation focusing on the type of exercise (stretching/ strengthening/aerobics/balance), frequency of participation (number of days in a week) and duration of involvement (in minutes) is also recommended (as presented in Figure 2.3.1). Experts suggested that the participation of midlife women in household chores might be limited due to the shifting of the household-related responsibilities to younger women. Hence, it is important to assess the daily sitting and screen time as two main indicators of sedentary behaviours in this group of women.[122]

Figure 2.3.1.

Key components of physical activity assessment

The application of objective methods of physical activity assessment such as wearable activity monitors (WAM) are more commonly used for self-monitoring of daily activity status. A number of technology-driven and consumer-oriented WAMs (e.g. Fitbit) and mobile applications are available for assessment of the number of steps taken per day. However, it is challenging for these methods to assess the intensity of physical activity.[123] The major limitation of this method is that it cannot assess physical activity compliance in accordance with the international activity guidelines of moderate-intensity physical activity.[121]

Experts believed that assessment of barriers faced in managing daily physical activity can help practitioners to devise a customised women-centric activity plan. A comprehensive tool for assessment of daily physical activity and barriers associated with maintaining daily activities in Indian midlife women is given in Annexure 4.

There is limited literature on comprehensive and practical tools that can be integrated into the clinical workflow with a limited burden on healthcare practitioners and patients. In current literature, the tools only account for the assessment of aerobic activity. As per the international recommendations for advising comprehensive physical activity, muscle strengthening and flexibility should be incorporated twice a week. Clinicians should include questions such as ‘How many times in a week do you engage in muscle-strengthening exercises such as bodyweight resistance?’ and ‘How many times do you participate in flexibility exercises such as stretching and yoga?’ in their routine assessment schedule.

2.4: How psychological and behavioural health should be evaluated in midlife women being engaged in the management of overweight and obesity?

Background

The question is important as psychological and behavioural health attributes may have an implication as it drives adherence and compliance amongst midlife women engaged in the management of overweight and obesity. The presence of diagnosed psychiatric disorders and clearly discernible psychological attributes may limit the ability of the woman to engage in structured weight-loss interventions. Behaviours such as stress and emotional eating may have an impact on the weight-loss trajectory or an increased probability to regain the initially lost weight. Thus, addressing psychological and behavioural health may be an important consideration in women who undergo weight-loss interventions.

The context of psychological and behavioural health holds importance as mental distress in midlife is common, especially depression and anxiety. Personality profile, stress appraisal and stress coping mechanisms may also influence adherence and outcome of weight management efforts. Moreover, eating disorders such as binge eating and food addiction may impair systematic efforts at weight loss by increasing proclivity towards sugar or fat-rich foods, which may lead to weight gain, or may impair weight reduction measures. Considering the role of psychological health in weight management, the assessment of psychological and behavioural health is of importance.

Summary of evidence