ABSTRACT

In January 2021, there were 9648 patients in Ukraine on kidney replacement therapy, including 8717 on extracorporeal therapies and 931 on peritoneal dialysis. On 24 February 2022, foreign troops entered the territory of Ukraine. Before the war, the Fresenius Medical Care dialysis network in Ukraine operated three medical centres. These medical centres provided haemodialysis therapy to 349 end-stage kidney disease patients. In addition, Fresenius Medical Care Ukraine delivered medical supplies to almost all regions of Ukraine. Even though Fresenius Medical Care's share of end-stage kidney disease patients on dialysis is small, a brief narrative account of the managerial challenges that Fresenius Medical Care Ukraine and the clinical directors of the Fresenius Medical Care centres had to face, as well as the suffering of the dialysis population, is a useful testimony of the burden imposed by war on these frail, high-risk patients dependent on a complex technology such as dialysis. The war in Ukraine is causing immense suffering for the dialysis population of this country and has called for heroic efforts from dialysis personnel. The experience of a small dialysis network treating a minority of dialysis patients in Ukraine is described. Guaranteeing dialysis treatment has been and remains an enormous challenge in Ukraine and we are confident that the generosity and the courage of Ukrainian dialysis staff and international aid will help to mitigate this tragic suffering.

Keywords: dialysis, organizational challenges, patients, Ukraine, war

INTRODUCTION

During periods of armed conflicts, as observed in other disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes [1–3], patients receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT) constitute one of the most vulnerable populations, due to the complexity and technicality of kidney care [4, 5], and the limitation of dialysis availability. These increase the risk of severe patient complications including death. Literature on best practices for continuing medical care during war is scarce [6], especially for non-communicable diseases [5]. War conflicts in Iraqi–Kuwait, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Syria, and Yemen were characterized by damaged general infrastructure, disorganization, chaos, lack of electricity, fuel and clean water, and shortages of supplies, medications, diagnostic tools and medical personnel [6, 7]. Blockades of humanitarian aid and attacks on healthcare facilities and medical personnel were also used as a military strategy [7, 8]. For unpredictable and prolonged periods KRT patients are suddenly victims of deleterious consequences such as management interruptions, missed dialysis sessions and need for hospitalization [9], and additional burdens, such as unfamiliar surroundings with culture or language barriers in the case of refugees to neighbouring countries [10].

In 2022 the Renal Disaster Relief Task Force of the European Renal Association (ERA) published a consensus statement aimed at mitigating the operational and medical risks of kidney patients during armed conflicts [11].

On 24 February 2022, foreign troops entered the territory of Ukraine. Since that day, at least 12 million people, equivalent to 27% of the Ukrainian population of 44.1 million, have fled their homes. Entire Ukrainian regions were attacked and all spheres of activity in the country, civilian institutions, schools, maternity hospitals, kindergartens and hospitals, were heavily damaged or affected. In areas where there were no active hostilities, medicines, bandages and necessary consumables became unavailable. Under these circumstances, ambulance and life-saving services continued their work.

As of 1 January 2021, there were 11 181 patients in Ukraine on KRT, including 6017 on haemodialysis, 2700 on haemodiafiltration (HDF), 931 on peritoneal dialysis and 1533 who had undergone kidney transplants [12]. Before the war, all patients on dialysis therapies were provided with erythropoietin, iron supplements and phosphate binders [4]. During the first 4 months of the war, an unknown number of Ukrainian patients on KRT were able to reach the relative safety of neighbouring European countries. Most of the ∼9600 patients who were receiving dialysis before the invasion remain in Ukraine. Thanks to the heroic sacrifice of all healthcare professionals, the efforts of dialysis providers, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Ukrainian Ministry of Health (MOH), the nephrology and dialysis units and their clinical staffs continued treating renal patients with spontaneity and professionalism including during bombing attacks.

Since the start of the war the Ukraine national healthcare system has not interrupted or modified the haemodialysis reimbursement payment rate which also includes laboratory tests and the cost of all intravenous drugs. Even though Fresenius Medical Care’s (FME) share of KRT patients on dialysis in its NephroCare (NC) clinics is small (3.8% and 2.0% of the whole haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis population in Ukraine, respectively) a brief narrative account of the managerial challenges that the healthcare professionals of the NC clinics had to face, and the suffering of the dialysis population, is a useful testimony of the burden imposed by this war on a frail, high-risk population such as patients dependent on a complex technology like dialysis.

ORGANIZATIONAL CHALLENGES

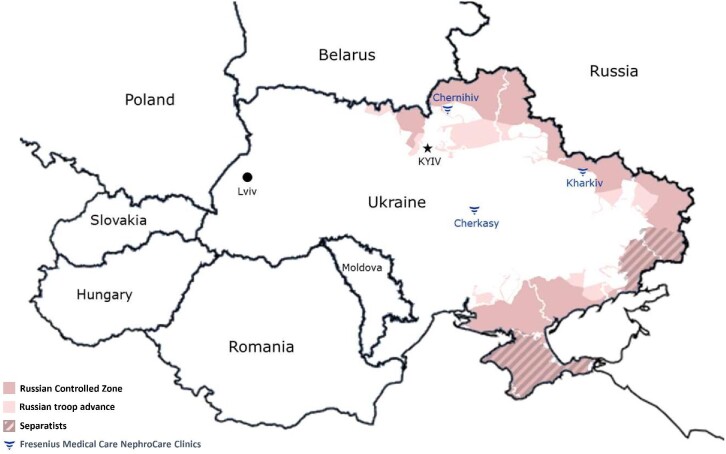

Before the war, FME's dialysis network in Ukraine operated three NC medical centres located in Cherkasy, Chernihiv and Kharkiv (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Geographical location of the three Fresenius Medical Care NephroCare clinics in Cherkasy, Chernihiv and Kharkiv, and the city of Lviv. On the map are also visualized the Ukraine territories under control of Russian troops and separatists, and under the Russian troop invasion, as of 25 March 2022.

In January 2022, the three medical centres provided dialysis therapy to 349 end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients: 320 of them by on-line post-dilution HDF, 6 by on-line haemofiltration, 4 by haemodialysis and 19 by peritoneal dialysis. In addition, FME Ukraine delivered medical supplies to almost all regions of Ukraine.

In accordance with the standard management of the dialysis clinics in the FME network, in the months before the war, FME Ukraine had prepared a significant stock of medical products and medicines to facilitate the continuous operation of their medical centres for 3–4 months. There were also sufficient dialysis consumables at FME warehouses in Ukraine to meet the needs of state clinics that had contracts with the company for the same products.

The NC clinics in Chernihiv and Kharkiv found themselves in an extremely difficult situation because of the heavy fighting in these cities.

FME NC clinic in Kharkiv

At the beginning of the war, the newly built medical centre in Kharkiv, which had started operations only 6 months previously, was providing 63 patients with haemodialysis therapy. From the first days of the war, all the physicians and several nurses from this centre were blockaded in their homes by the occupying forces and were not able to work in the clinic. Only five nurses were able to reach and work at the dialysis centre to provide continuous treatment to all dialysis patients. At that time EuCliD, FME's electronic healthcare system and database [13], and Therapy Monitor (TMon), a monitoring software for the therapy data management system, were actively maintained in the clinic. This allowed the dialysis physicians, based remotely in Cherkasy, to coordinate the nursing team in Kharkiv via daily teleconferences and telemonitoring the clinical and operational performances. Due to the constant shelling of Kharkiv, the staff was forced to reduce dialysis treatment to twice a week. This reduced the activity of the medical centres to four shifts a week to minimize the danger to personnel commuting to work under the risk of gunfire and shelling. Patients who received dialysis, as well as some of the medical staff on the last shift of the day, stayed overnight at the centre. On 17 March 2022 it was decided to evacuate patients to our partner centres in Lviv (Fig. 1). A total of 51 patients, with their family members and pets, were evacuated. The evacuation was done by train, with the employees of the dialysis centre in Kharkiv taking the patients to the railway station themselves (Fig. 2). At the time of writing, the patients from the medical centre in Kharkiv were still receiving haemodialysis treatment in Lviv, Cherkasy and other clinics abroad.

Figure 2:

Dialysis patients from the FME clinic in Kharkiv before being evacuated by train to Lviv.

FME NC clinic in Chernihiv

The city of Chernihiv was occupied by Russian troops on the first day of the war. Some staff members of the clinic in Chernihiv were also blocked and thus unable to perform their activities in the clinic. Prior to the war, in January 2022, 119 ESKD patients had been receiving dialysis therapies in the clinic in Chernihiv. Of them, 114 were being treated with haemodialysis and five with peritoneal dialysis. In total, the centre lost 19 patients including some who chose to independently leave the area and successfully relocated to other Ukrainian centres, and others who were taken by the Russian army to Belarus. Ninety-five patients continued to be treated in the FME dialysis clinic of Chernihiv.

Because of the life-threatening situation posed by the constant shelling, dialysis treatments were also reduced to twice a week. Many employees and patients lived in the suburbs and the risk of shelling, plus disruption to the city's transportation system, made it impossible for them to get to the medical centre. The only viable solution was to use the NC premises as a permanent residence for patients, some of their family members and the dialysis staff. Thus, more than 70 people—patients, parts of their families and staff—had to live inside our centre for three whole weeks. During this time, the staff of the centre provided them all with food and medicine, and took care of all their other basic needs (Fig. 3).

Figure 3:

Clinical staff members of FME Chernihiv dialysis centre.

When the shelling intensified, it was decided to equip the basement of the FME building for haemodialysis therapy, and to transfer patients there from the second floor. Our engineers quickly made all the necessary adaptations to relocate seven haemodialysis stations to the basement. On the first floor, the windows and doors were barricaded with concentrate boxes to protect patients and employees from the possible effects of explosions.

Thanks to these adaptations, albeit uncertain and risky, dialysis treatment was possible until 13 March 2022 when, following heavy shelling and rocket attacks, the city's water and electricity systems were damaged. Later, our dialysis centre was shelled, and as a result the windows, doors and facade were heavily damaged (Fig. 4).

Figure 4:

FME Chernihiv clinic damaged by a rocket attack.

The mobile phone service in the city was severely disrupted. The creation of humanitarian corridors was delayed by continued shooting and rocket attacks. FME management and staff created and maintained a channel of communication with many authorities including the MOH and the Office of the President of Ukraine. As a result, it was possible to evacuate patients and staff from the Chernihiv centre. Thus, on 19 March 2022, more than 130 individuals and their families, as well as FME personnel were evacuated by bus to Kyiv where they spent the night in the railway station. The next morning, they were taken to our haemodialysis centre in Cherkasy.

Among the evacuated patients were not only patients who were being dialyzed in the Chernihiv NC clinic, but also patients from other hospitals who had not received dialysis therapy for more than a week. Despite the long interruption of dialysis treatment, none of the patients developed major intradialytic complications (e.g. dialysis disequilibrium syndrome, intradialytic hypotension). The first dialysis therapy for the new guests at the Cherkasy centre was provided by diffusive technique, low blood flow, and with small surface area dialysers. As soon as the clinical condition of the patients was stabilized, they were treated with on-line post-dilution HDF for 4 h three times a week as is the standard procedure in FMC NC clinics. Seven patients required urgent hospitalization. All other patients received a full haemodialysis session in the FME dialysis centre. Three patients needed vascular access revision, and all corrections were performed during the first week after evacuation to Cherkasy. One patient required a central vein catheterization, and a permanent catheter was placed during that same week. Of the 115 patients being treated in Chernihiv at the start of the war, three died: two from ballistic injuries during attacks and one who was blockaded at home and unable to reach the dialysis centre.

FME NC clinic in Cherkasy

Cherkasy is in a relatively safe region of Ukraine without active hostilities. The clinic is designed to dialyse no more than 242 patients. In the first days following the arrival of the new patients, thanks to all members of the clinical staff and the management team of the medical centre, haemodialysis treatments were provided to 251 patients. Today, the NC centre in Cherkasy is working as a hub for ESKD refugees from different regions of Ukraine, and primarily from Chernihiv. To facilitate the uninterrupted documentation of ongoing treatments, in addition to EuCliD, TMon has been installed in this centre. To protect the centre from potential water and electricity outages, generators sent by FME in Germany have been installed. As all patients in Cherkasy are treated by on-line post-dilution HDF, tap water and dialysate water qualities are being evaluated monthly to exclude possible contamination with toxic chemicals, bacteria and associated endotoxins. A Starlink internet connection has also been installed. Thus, the centre in Cherkasy can once again operate autonomously and effectively.

One of the most difficult operational tasks in Cherkasy was to provide accommodation for all patients from Chernihiv, Kharkiv and other centres, and in some cases for patients’ family members and pets. The city authorities helped FME, making the entire city hospital available as accommodation for the refugees. FME Ukraine's dialysis centres organized food delivery to all evacuated patients. Together with FME's European and Israeli colleagues, fund-raising was organized to cater for the patients’ immediate needs for food, clothing and personal hygiene items. Thanks to the support of FME colleagues in Germany, humanitarian supplies were delivered including food, clothing and essential medicines (anti-hypertensives, L-thyroxin, EPO, heparin, antidepressants, surgical dressings). Financial support was provided by the Fresenius Medical Care CARES Fund (FME USA) in the form of two grants for all the staff members in Ukraine.

In May 2022, due to the scale-down and ending of military activity around Chernihiv, we decided to re-open the dialysis centre in Chernihiv. Therefore, 63 patients dialysing at the NC Cherkassy clinic who previously dialysed at NC's Chernihiv clinic were progressively relocated back to Chernihiv, together with their family members and FME personnel, to re-start their treatments there. Since June, NC's dialysis centres in Cherkasy and Chernihiv have been performing dialysis treatment for their patients without interruptions, while the NC centre in Kharkiv has been closed since February 2022. In September 2022, FME's Cherkasy and Chernihiv clinics provided dialysis therapy to 278 ESKD patients: 258 of them by on-line post-dilution HDF and 20 by peritoneal dialysis. In November 2022 the Cherkasy regional oncological centre has successfully performed a kidney transplant on a patient in haemodialysis treatment at NC Cherkasy clinic. It was the first kidney transplant executed on patient treated at Fresenius Medical Care clinics in Ukraine since the start of the war.

MEDICAL CHALLENGES

We agree with Stepanova that the main medical challenge is the inability of the patients and healthcare staff to reach the dialysis centre due to rocket attacks, bombing and active hostilities on the ground [4]. We also agree with Vanholder et al. that in patients on maintenance dialysis the complications due to impossibility or inadequacy of dialysis, increased risk for vascular or peritoneal access problems, and infections should be prevented [5].

Before the start of the war, we re-trained all patients to strictly adhere to dietary measures avoiding high-potassium food, and decreasing salt, fluid and protein. We instructed all capable patients with arterio-venous fistulas how to perform emergency self-disconnection from the machine to urgently evacuate from the clinic following staff instructions. Those patients who need assistance in disconnection and evacuation during an emergency were identified.

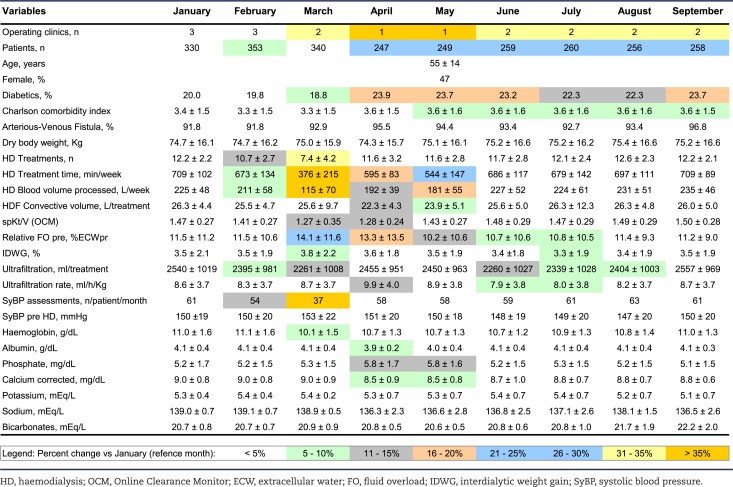

The most difficult period for the FME NC centres was between March and May 2022. To respond to the increased demand for dialysis treatment in the Cherkasy clinic due to the relocation of additional patients to that centre, the dialysis frequency and dose (evaluated by Kt/V and convective volume/treatment) had to be temporarily reduced. Due to the exposure to wartime stress and its impact on nutritional status, the body composition fluid status and dry body weight of all patients were assessed via whole-body bioimpedance spectroscopy (BCM, FME) as described by Moissl et al. [14] and Machek et al. [15]. Since June we have progressively recovered our dialysis quality standards [16] in accordance with the FME Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) medical continuous quality performance guidelines [16], and in July, August and September both dialysis and medical quality key performance indicators, respectively, were equal, if not superior to those evaluated in January, before the start of the war (Table 1).

Table 1:

Haemodialysis and medical quality performance indicators of patients dialysed in Ukrainian FME NC clinics during the war in Ukraine

Benchmarking March with January 2022, the dialysis sessions and weekly treatment time fell abruptly from 12.2 to 7.4 and from 709 to 376 min, respectively. The dialysis dose delivered (spKt/V) fell from 1.47 to 1.27, the weekly blood volume processed went down from 225 to 115 L/week, and in patients on HDF the convective volume/treatment decreased from 26.3 to 22.3 L. Notwithstanding these major changes in the delivered treatment, systolic blood pressure, albumin, potassium, sodium and bicarbonate remained fairly constant throughout. Serum phosphate rose and calcium declined transiently in April–May 2022, and gradually recovered thereafter. The relative FO (=FO/extracellular volume) assessed via whole-body bioimpedance spectroscopy increased from 11.5 to 14.1 showing an extracellular volume expansion most probably caused by fluid accumulation due to the weekly dialysis treatment time reduction.

KRT patients are at elevated risk for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and progression to severe or fatal disease [17]. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Ukraine and the additional risks of contracting COVID-19 in space-constrained bomb shelters during air raids and packed trains while evacuating, the application of all infection prevention and safety measures was extended and intensified. All patients were requested to wear masks and respect social-distancing measures during the dialysis shifts and whilst in the waiting rooms before and after the dialysis treatment. In January 2022 the percentage of patients who had completed the COVID-19 vaccination cycle was 88% in Cherkasy, 78% in Chernihiv and 60% in Kharkiv. In October 2022, among those patients that had completed the vaccination cycle, 50% of them received the COVID-19 vaccination booster dose. Before the war all clinical staff members completed the vaccination cycle and in October 2022, 75% of them received a booster dose. Since March 2022, no COVID-19-positive cases or Hepatitis B or C seroconversions were identified in NC clinics in Ukraine.

FME Ukraine also encountered many difficulties in delivering peritoneal dialysis solutions. Delivery by transport companies was impossible, so some volunteers took on this extremely difficult and risky task. Some patients resided in occupied territories. Our heroic staff courageously delivered their peritoneal dialysis solutions at considerable risk to their own lives. Two peritonitis episodes occurred, and both were successfully treated with oral antibiotics.

It is important to note that in the early days of the war, the FME dialysis physicians, together with the State Institution ‘Institute of Nephrology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine’, in Nams, developed recommendations for the provision of dialysis assistance in wartime. These recommendations, written in Ukrainian language, were published on the website of the Institute of Nephrology [18].

FME Ukraine also supported the creation of a community for Doctors-Nephrologists (posted in Viber, a proprietary software that offers a VoIP instant messaging application) across Ukraine to coordinate operations with refugees, giving advice and enabling quick exchange of information regarding possibilities for the provision of treatment and the availability of places in the different regions of Ukraine. An additional Viber community was created by FME dialysis physicians to provide dietary and drug treatment recommendations in case dialysis therapy is not available. In this Viber chat, the moderator provides daily updates and information on the availability of dialysis treatment in regions of Ukraine spared from or less badly affected by the war.

Finally, since the first days of the war, an ad hoc expert group ‘FME Ukraine Crisis Team’ was created with the constant support and advice of the FME EMEA Headquarters in Germany. It consists of representatives of the FME Regional Crisis Response Team EMEA and core team members of FME Ukraine. This crisis team meets daily to safeguard the humanitarian needs of our medical centres and the users of FME products.

FME Regional Crisis Response Team EMEA representatives are actively collaborating with the Ukrainian MOH, Ukrainian nephrology community, ERA Renal Disaster Relief Task Force, European Kidney Health Alliance, European Kidney Patients’ Federation, WHO and Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders) to provide help to all Ukrainian kidney patients and their healthcare workers.

Due to the great efforts of all members of the FME team in Ukraine, in the first month of the war all customers were provided with disposables, even in those regions where hard combat was taking place. Also, humanitarian aid delivered by FME Germany was immediately sent to those patients and employees who needed it most urgently.

Humacyte, Inc. (Durham, NC, USA), for humanitarian reasons made investigational bioengineered human acellular vessels (HAVs) available to treat vascular access problems at FME centres. Subsequently the same company generously extended to five Ukrainian hospitals the provision of HAV to treat civilians suffering traumatic vascular injuries. As of October 2022, a total of nine patients received a HAV to repair various types of wartime arterial injuries, such as gunshot wounds, mine blasts, and shrapnel injuries to the upper and lower extremities.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the Ukrainian war has inflicted immense suffering to the Ukrainian population and generated wide-ranging health problems, spanning from women’s health and perinatal care [19], to oncology [20], and internal medicine and surgery at large, and enormous logistic issues [21]. In this war scenario, the problems for the dialysis population of this country have been and remain a unique challenge that has demanded heroic efforts from dialysis personnel.

As a lesson learned from previous man-made disasters, before the start of the war FME drew up a ‘to-do list’ of general measures to be adopted which aimed to mitigate the impact of conflict on dialysis patients and clinical staff. We agree with the ERA recommendations to prevent the lack of electricity and water, shortage of dialysis material, supplies, medications, diagnostic tools and medical personnel. In case of necessity, the NC clinics are utilized as a permanent location for patients, their family members and the dialysis staff. The staff of the centre provide all parties with food and medicine, and take care of all their other basic needs. Patients and clinical staff are constantly trained on medical and security issues. Patients are educated about the importance of strict dietary/fluid intake measures. Telemonitoring and telemedicine granted our physicians the ability to remotely coordinate the nursing team and evaluate the health status of patients in renal replacement therapy. We strongly believe in coordination and collaboration with the nephrological community, authorities and non-governmental organizations with regard to the needs of patients and healthcare staff.

In case of emergency (e.g. the urgent evacuation of 130 patients from Chernihiv to Cherkasy), as a short-term compromise, we reduced the number of dialysis sessions, shortening them without observing unfavourable outcomes for patients.

Specific measures to prevent ‘burnout’ of personnel were not adopted, because the healthcare professionals were greatly motivated to help and support their country and their patients.

Even though we describe the experience of a small dialysis network treating a minority of dialysis patients in Ukraine, similar or even more painful and demanding narratives in state dialysis centres in Ukraine are to be found via social media and other available communication channels. Ensuring dialysis treatment has been and remains an enormous challenge in Ukraine but we are confident that the generosity and the courage of Ukrainian dialysis staff and international aid will help in mitigating the suffering of this tragedy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the FME Regional Crisis Response Team EMEA members, the core team members and all employees of Fresenius Medical Care Ukraine for their constant support, passion and empathy. The authors thank those countries that have common borders with Ukraine and all FME Medical Directors in these countries (Poland, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia) for their help in organizing dialysis treatment and accommodation for Ukrainian refugees. Finally, the authors thank Helen Cooper and Giovanni Tripepi for their technical support to finalize the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Volodymyr Novakivskyy, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Roman Shurduk, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Inna Grin, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Taisiia Tkachenko, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Nataliia Pavlenko, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Anastasiia Hrynevych, Fresenius Medical Care, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Jeffrey L Hymes, Fresenius Medical Care, Global Medical Office, Bad Homburg, Germany.

Franklin W Maddux, Fresenius Medical Care, Global Medical Office, Bad Homburg, Germany.

Stefano Stuard, Fresenius Medical Care, Global Medical Office, Bad Homburg, Germany.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors are Fresenius Medical Care employees. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vanholder R, Gallego D, Sever MS. Wars and kidney patients: a statement by the European Kidney Health Alliance related to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. J Nephrol 2022;35:377–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonomini M, Stuard S, Dal Canton A. Dialysis practice and patient outcome in the aftermath of the earthquake at L'Aquila, Italy, April 2009. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanholder R, Stuard S, Bonomini M.et al. . Renal disaster relief in Europe: the experience at L'Aquila, Italy, in April 2009. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stepanova N. War in Ukraine: the price of dialysis patients’ survival. J Nephrol 2022;35:717–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanholder R, De Weggheleire A, Ivanov DD.et al. . Continuing kidney care in conflicts. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022;18:479–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sekkarie M, Murad L, Al-Makki A.et al. . End-stage kidney disease in areas of armed conflicts: challenges and solutions. Semin Nephrol 2020;40:354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Isreb MA, Rifai AO, Murad LB.et al. . Care and outcomes of end-stage kidney disease patients in times of armed conflict: recommendations for action. Clin Nephrol 2016;85:281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mesic E, Aleckovic-Halilovic M, Tulumovic D.et al. . Nephrology in Bosnia and Herzegovina: impact of the 1992-95 war. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:803–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson AH, Cohen AJ, Kutner NG.et al. . Missed dialysis sessions and hospitalization in hemodialysis patients after Hurricane Katrina. Kidney Int 2009;75:1202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Biesen W, Vanholder R, Vanderhaegen B.et al. . Renal replacement therapy for refugees with end-stage kidney disease: an international survey of the nephrological community. Kidney Int Suppl 2016;6:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sever MS, Vanholder R, Luyckx V.et al. . Armed conflicts and kidney patients: a consensus statement from the renal disaster relief task force of the ERA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;23:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kolesnyk MD, Liksunova V, Stepanova L.et al. . State Institution ‘Institute of Nephrology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine’: 20 years afterward. Ukr J Nephr Dial 2021;4:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steil H, Amato C, Carioni C.et al. . EuCliD—a medical registry. Methods Inf Med 2004;43:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moissl UM, Wabel P, Chamney PW.et al. . Body fluid volume determination via body composition spectroscopy in health and disease. Physiol Meas 2006;27:921–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Machek P, Jirka T, Moissl Uet al. . Guided optimization of fluid status in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:538–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garbelli M, Ion Titapiccolo J, Bellocchio F.et al. . Prolonged patient survival after implementation of a continuous quality improvement programme empowered by digital transformation in a large dialysis network. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022;37:469–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chung EYM, Palmer SC, Natale P.et al. . Incidence and outcomes of COVID-19 in people with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2021;78:804–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Institute of Nephrology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine . Державна установа “Інститут нефрології Національної академії медичних наук України” (inephrology.kiev.ua) (1 December 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mogilevkina I, Khadzhynova N. War in Ukraine: challenges for women's and perinatal health. Sex Reprod Healthc 2022;32:100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. War in Ukraine disrupts trials, cancer care. Cancer Discov 2022;12:1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fong A, Johnson K.. Responding to the war in Ukraine. CJEM 2022;24:471–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.