Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to provide the most updated estimates on the global burden of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to improve management strategies.

Design

We extracted data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 database to evaluate IBD burden with different measures in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019.

Setting

Studies from the GBD 2019 database generated by population-representative data sources identified through a literature review and research collaborations were included.

Participants

Patients with an IBD diagnosis.

Outcomes

Total numbers, age-standardised rates of prevalence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and their estimated annual percentage changes (EAPCs) were the main outcomes.

Results

In 2019, there were approximately 4.9 million cases of IBD worldwide, with China and the USA having the highest number of cases (911 405 and 762 890 (66.9 and 245.3 cases per 100 000 people, respectively)). Between 1990 and 2019, the global age-standardised rates of prevalence, deaths and DALYs decreased (EAPCs=−0.66,–0.69 and −1.04, respectively). However, the age-standardised prevalence rate increased in 13 out of 21 GBD regions. A total of 147 out of 204 countries or territories experienced an increase in the age-standardised prevalence rate. From 1990 to 2019, IBD prevalent cases, deaths and DALYs were higher among females than among males. A higher Socio-demographic Index was associated with higher age-standardised prevalence rates.

Conclusions

IBD will continue to be a major public health burden due to increasing numbers of prevalent cases, deaths and DALYs. The epidemiological trends and disease burden of IBD have changed dramatically at the regional and national levels, so understanding these changes would be beneficial for policy makers to tackle IBD.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, EPIDEMIOLOGY, Gastroenterology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the most updated estimate on inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology worldwide and included 204 countries, some of which have not been assessed before.

Global Burden of Disease 2019 incorporated more studies, adjusted diagnostic criteria and further improved data reliability, hence presenting data more representative of individuals.

One of the limitations was heterogeneity in population and location between the studies included.

Another limitation is that the variability in study design and data collection methods also affected the precision of the estimates, which is only partially compensated for in our analysis model.

The third limitation is that the results for some geographical regions were severely limited by the paucity of data (not just variability in study design but lack of studies) and should be treated with caution.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are debilitating and chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that have no cure.1 IBD is characterised by a relapsing-remitting course and a heterogeneous clinical presentation that includes episodes of abdominal pain, chronic diarrhoea, rectal bleeding and weight loss, which are often associated with systemic symptoms such as fatigue and occasionally fever.2 Because IBD can cause significant morbidity and lead to complications such as strictures, fistulas, infections and cancer, this disorder leads to substantial healthcare costs and places great stress on healthcare systems.3 4 Although the cause of IBD remains unknown, the pathogenesis of IBD is suggested to be associated with genetic susceptibility of the host, intestinal microbiota, other environmental factors (eg, diet, smoking and physiological stress), and immunological abnormalities.5

Traditionally, IBD has been regarded as a disease of the Western world; however, studies over the last two decades have shown a rapidly increasing incidence in newly industrialised countries in the Middle East, Asia and South America.6 Conversely, IBD incidence rates appeared to plateau in the Western world in the 21st century.7 These substantial changes highlight the need for a comparable, consistent and systematic analysis of disease burden and trends concerning IBD in different regions and countries, which can be used to provide convincing evidence for rational allocation of resources and heathcare planning in reducing the global burden of IBD.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019, a systematic worldwide epidemiological study, assessed the prevalence, morbidity, mortality and disability of 369 diseases by location, sex, age and year,8 which provides a unique opportunity to understand the state of IBD. The purpose of this study was to use data from the GBD 2019 study to determine the global, regional and national burden of IBD across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019 by age, sex and Socio-demographic Index (SDI). Our study provides updated estimates on global IBD epidemiology and provides data on some regions not assessed previously or data-scarce locations, of which estimates mainly rely on predictive covariates or global trends with consideration of SDI level and data from a single country.

Methods

The general methodology of GBD 2019 has been reported in detail in previous publications.8–11 In brief, the GBD Study collected data from censuses, household surveys, civil registration and vital statistics, disease registries, health service use, satellite imaging, disease notifications and other sources.9 A Bayesian meta-regression modelling tool, DisMod-MR 2.1, was used to model and derive estimates of the burden under several conditions in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019.9 The model included all of the above available information for each disease and applied a correcting process for known bias to derive country-specific estimates of prevalence and burden of diseases, which have been described in previous studies.8 Uncertainty intervals (UIs) were generated for every metric using the 25th and 75th ordered 1000 draw values of the posterior distribution.9

We extracted yearly crude and age-standardised estimates of different measures of the burden of IBD from the GBD database from 1990 to 2019 and the respective 95% UIs via the Global Health Data Exchange query tool (http://ghdx.healt hdata.org/gbd-results-tool). For the GBD 2019 assessment, IBD was defined according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10 codes: K50–K51.319, K51.5–K52, K52.8–K52.9). The variables obtained from the database included prevalent cases, number of deaths, number of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), number of years of life lost (YLL), number of years lived with disability (YLD) and their corresponding age-standardised rates (ASRs) at the global, regional and national levels. The prevalence rate (per 100 000 people) was defined as aggregated cases (including new cases and previously diagnosed cases) divided by the population size; the mortality rate (per 100 000 people) was defined as the number of annual deaths divided by the total population size and DALYs were calculated as the sum of YLL and YLD. These data were stratified by age (1–4, 5–9, every 5-year age group up to 95 years and 95 years and older), calendar year (1990–2019), region and country (or territory). Geographically, the world was classified into 21 regions. Moreover, 204 countries and territories were divided into five categories according to the SDI. The SDI was constructed based on the geometric mean of three indicators: the total fertility rate, income per capita and average years of schooling among people aged 15 years or older, ranging from zero to one.12 The larger the SDI, the more developed the country.13

Estimated average percentage changes (EAPCs) were used to evaluate trends in the ASRs of prevalence, deaths and DALYs over a specific period. The natural logarithm of the ASR was assumed to be linear along with time; that is, y = α+βx+ɛ, where y=ln (rate), x=calendar year and ε=error term. Based on this formula, β represents the positive or negative ASR trends. The EAPC was calculated as 100 × (exp (β) −1), and its 95% CI could also be calculated from this model.14 The age-standardised indicator was recognised to be experiencing an upward trend if the 95% CI of the corresponding EAPC estimation was >0, to be experiencing a downward trend if the 95% CI was <0 and to be stable if the 95% CI included 0. All statistical analyses and visualisations were conducted using the R statistical software program (V.4.1.0). A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study followed the guidelines for a cross-sectional study described in the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting.15

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Prevalence of IBD

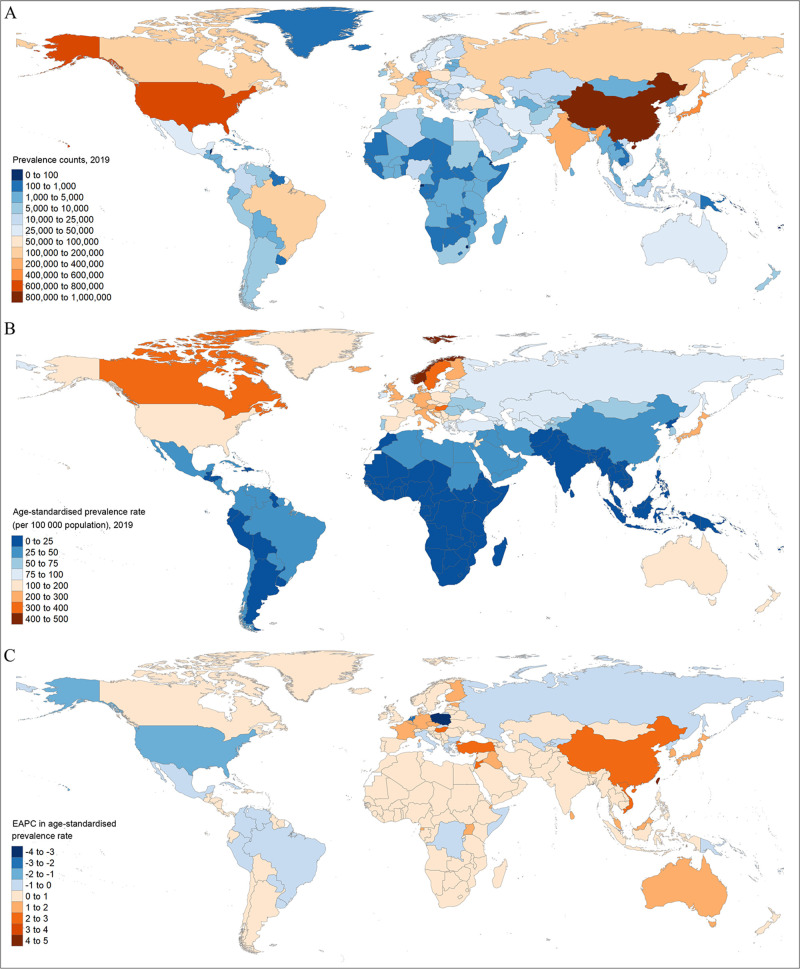

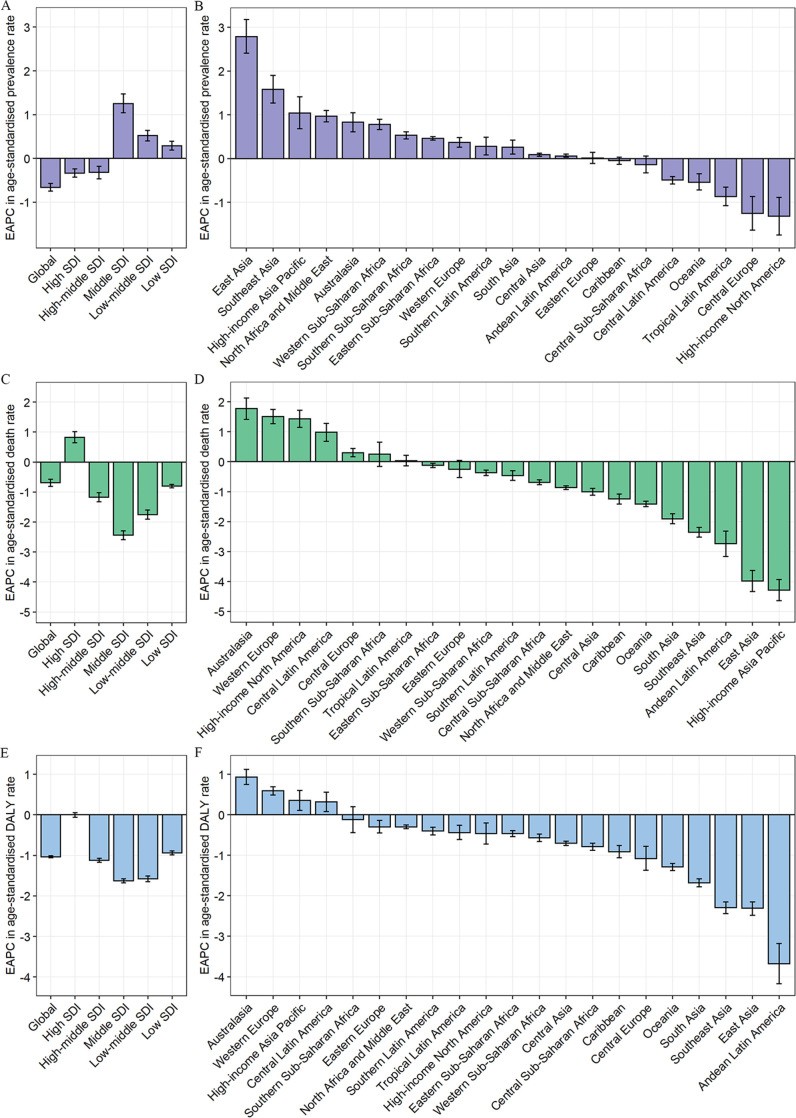

Globally, IBD accounted for 3.32 million estimated cases (95% UI 2.90 to 3.79) in 1990 and 4.90 million cases (4.35 to 5.50) in 2019, corresponding to an increase of 47.45% between 1990 and 2019 (online supplemental table 1 and figure 1A). The global age-standardised prevalence rate of IBD decreased from 73.23 per 100 000 people (63.86 to 83.63) in 1990 to 59.25 per 100 000 people (52.78 to 66.47) in 2019, with an EAPC of −0.66 (95% CI −0.75 to −0.57) (table 1; figure 1B, C; and figure 2A). Although graphical representation suggested homogeneity of data quality across the globe, this was not the case, and estimates were based on extremely limited data and should be treated with caution in some regions.

Figure 1.

The global prevalence burden of IBD in 204 countries and territories. (A) The absolute number of IBD prevalent cases in 2019. (B) The age-standardised prevalence rate (per 100 000 population) of IBD in 2019. (C) The EAPC of age-standardised prevalence rate for IBD between 1990 and 2019. EAPC, estimated annual percentage change; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Table 1.

Age-standardised prevalence, death and DALY rates for inflammatory bower disease (IBD) in 1990 and 2019 and their temporal trends from 1990 to 2019

| Characteristics | Age-standardised prevalence rate per 100 000 population | Age-standardised death rate per 100 000 population | Age-standardised DALY rate per 100 000 population | ||||||

| 1990 no (95% UI) | 2019 no (95% UI) | EAPC no (95% CI) | 1990 no (95% UI) | 2019 no (95% UI) | EAPC no (95% CI) | 1990 no (95% UI) | 2019 no (95% UI) | EAPC no (95% CI) | |

| Global | 73.23 (63.86 to 83.63) | 59.25 (52.78 to 66.47) | −0.66 (−0.75 to −0.57) | 0.67 (0.57 to 0.78) | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.59) | −0.69 (−0.81 to −0.57) | 27.20 (21.70 to 32.39) | 20.15 (16.86 to 23.71) | −1.04 (−1.06 to −1.01) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 71.52 (62.12 to 81.89) | 59.30 (52.60 to 66.91) | −0.56 (−0.64 to −0.49) | 0.69 (0.56 to 0.88) | 0.56 (0.45 to 0.62) | −0.78 (−0.83 to −0.72) | 27.40 (21.78 to 33.22) | 20.64 (17.16 to 24.31) | −0.99 (−1.01 to −0.97) |

| Female | 75.01 (65.67 to 85.45) | 59.33 (52.89 to 66.18) | −0.74 (−0.85 to −0.64) | 0.63 (0.50 to 0.74) | 0.52 (0.43 to 0.58) | −0.64 (−0.80 to −0.47) | 27.09 (20.30 to 32.42) | 19.70 (16.16 to 23.49) | −1.09 (−1.12 to −1.06) |

| SDI quintile | |||||||||

| High | 200.83 (176.43 to 226.92) | 183.14 (166.58 to 201.17) | −0.34 (−0.43 to −0.24) | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.85) | 0.84 (0.69 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.64 to 1.01) | 43.95 (34.13 to 55.06) | 42.93 (33.66 to 53.08) | 0.00 (−0.06 to 0.05) |

| High middle | 82.41 (71.42 to 95.06) | 73.85 (65.38 to 83.09) | −0.32 (−0.47 to −0.18) | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.60) | 0.38 (0.34 to 0.43) | −1.17 (−1.32 to −1.02) | 25.92 (21.34 to 30.93) | 19.34 (15.59 to 23.73) | −1.12 (−1.17 to −1.07) |

| Middle | 22.50 (19.00 to 26.62) | 30.57 (25.70 to 36.01) | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.47) | 0.57 (0.40 to 0.74) | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.34) | −2.44 (−2.59 to −2.29) | 18.11 (14.29 to 21.72) | 11.61 (9.70 to 13.71) | −1.63 (−1.68 to −1.58) |

| Low middle | 19.02 (15.75 to 22.93) | 20.94 (17.41 to 25.11) | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.64) | 0.74 (0.47 to 1.06) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.58) | −1.75 (−1.90 to −1.60) | 23.29 (16.18 to 30.53) | 15.37 (12.47 to 18.32) | −1.58 (−1.65 to −1.51) |

| Low | 12.40 (10.21 to 15.06) | 12.85 (10.64 to 15.81) | 0.29 (0.19 to 0.39) | 0.67 (0.48 to 0.99) | 0.55 (0.43 to 0.70) | −0.80 (-0.86 to -0.74) | 22.19 (14.49 to 29.80) | 17.19 (13.57 to 21.70) | −0.94 (-0.99 to -0.89) |

| GBD region | |||||||||

| Andean Latin America | 16.55 (14.08 to 19.39) | 17.09 (14.60 to 19.88) | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.10) | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.71) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.32) | −2.74 (−3.16 to −2.32) | 26.36 (15.78 to 38.96) | 9.83 (7.75 to 12.19) | −3.68 (−4.17 to −3.18) |

| Australasia | 108.86 (92.21 to 126.63) | 156.30 (137.65 to 177.07) | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.05) | 0.54 (0.47 to 0.64) | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.83) | 1.77 (1.41 to 2.13) | 26.19 (20.48 to 32.91) | 34.98 (26.87 to 44.64) | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.12) |

| Caribbean | 27.93 (23.96 to 32.85) | 26.31 (22.13 to 31.28) | −0.05 (−0.13 to 0.03) | 0.56 (0.44 to 0.69) | 0.42 (0.31 to 0.53) | −1.24 (−1.41 to −1.08) | 23.38 (16.68 to 34.05) | 18.21 (13.08 to 24.76) | −0.91 (−1.06 to −0.76) |

| Central Asia | 76.86 (64.98 to 91.56) | 78.72 (66.39 to 93.40) | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.12) | 0.39 (0.30 to 0.46) | 0.32 (0.28 to 0.37) | −1.00 (−1.12 to −0.89) | 26.11 (21.03 to 31.71) | 22.26 (18.04 to 27.31) | −0.70 (−0.76 to −0.65) |

| Central Europe | 208.99 (179.90 to 243.75) | 160.49 (145.58 to 176.95) | −1.25 (−1.64 to −0.87) | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.52) | 0.47 (0.40 to 0.55) | 0.30 (0.17 to 0.44) | 46.28 (36.16 to 57.91) | 35.84 (27.66 to 44.67) | −1.08 (−1.37 to −0.78) |

| Central Latin America | 37.84 (32.42 to 44.16) | 32.59 (27.93 to 38.07) | −0.49 (−0.58 to −0.41) | 0.32 (0.28 to 0.35) | 0.37 (0.30 to 0.43) | 0.98 (0.68 to 1.28) | 14.84 (12.69 to 17.31) | 14.68 (12.25 to 17.41) | 0.32 (0.08 to 0.56) |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 8.22 (6.76 to 10.11) | 8.21 (6.80 to 10.11) | −0.14 (−0.33 to 0.06) | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.03) | 0.60 (0.45 to 0.83) | −0.69 (−0.77 to −0.60) | 22.26 (14.75 to 32.74) | 17.77 (12.98 to 24.27) | −0.79 (−0.88 to −0.70) |

| East Asia | 22.51 (18.72 to 26.72) | 46.22 (39.36 to 53.98) | 2.79 (2.41 to 3.18) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.14) | 0.31 (0.25 to 0.35) | −3.98 (−4.33 to −3.63) | 24.23 (17.74 to 29.83) | 13.08 (10.31 to 16.19) | −2.31 (−2.48 to −2.15) |

| Eastern Europe | 88.07 (75.40 to 103.25) | 82.82 (70.77 to 96.45) | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.14) | 0.49 (0.38 to 0.56) | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.58) | −0.25 (−0.53 to 0.04) | 27.68 (21.86 to 33.71) | 26.67 (21.96 to 32.46) | −0.30 (−0.45 to −0.14) |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 6.27 (5.25 to 7.68) | 7.21 (6.01 to 8.82) | 0.46 (0.42 to 0.50) | 0.72 (0.52 to 1.01) | 0.69 (0.50 to 0.93) | −0.12 (−0.20 to −0.05) | 22.58 (16.13 to 33.35) | 19.44 (14.69 to 25.63) | −0.46 (−0.54 to −0.39) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 126.18 (105.73 to 149.32) | 210.54 (183.69 to 239.68) | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.41) | 0.40 (0.24 to 0.47) | 0.13 (0.11 to 0.18) | −4.29 (−4.64 to −3.93) | 26.43 (19.87 to 33.86) | 34.55 (23.75 to 46.76) | 0.35 (0.11 to 0.60) |

| High-income North America | 346.93 (303.63 to 392.66) | 209.60 (195.48 to 224.46) | −1.32 (−1.75 to −0.89) | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.83) | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.05) | 1.43 (1.15 to 1.72) | 65.62 (48.61 to 84.95) | 51.27 (40.90 to 62.35) | −0.46 (−0.72 to −0.20) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 36.27 (31.06 to 41.91) | 48.26 (40.98 to 56.94) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.10) | 0.34 (0.24 to 0.49) | 0.26 (0.22 to 0.30) | −0.86 (−0.93 to −0.80) | 14.36 (10.79 to 18.73) | 13.26 (10.60 to 16.47) | −0.30 (−0.34 to −0.25) |

| Oceania | 4.34 (3.51 to 5.20) | 3.87 (3.16 to 4.71) | −0.54 (−0.72 to −0.35) | 0.63 (0.42 to 0.86) | 0.44 (0.33 to 0.60) | −1.41 (−1.50 to −1.32) | 20.60 (13.34 to 28.78) | 14.93 (10.45 to 21.01) | −1.29 (−1.38 to −1.20) |

| South Asia | 19.68 (15.98 to 24.40) | 20.11 (16.38 to 24.81) | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.42) | 0.69 (0.47 to 1.06) | 0.44 (0.33 to 0.57) | −1.91 (−2.07 to −1.74) | 21.48 (14.77 to 29.47) | 14.00 (10.70 to 17.52) | −1.68 (−1.78 to −1.58) |

| Southeast Asia | 4.40 (3.55 to 5.35) | 6.69 (5.52 to 8.04) | 1.58 (1.27 to 1.90) | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.66) | 0.28 (0.21 to 0.33) | −2.36 (−2.52 to −2.19) | 13.16 (8.47 to 15.9) | 7.45 (6.06 to 8.76) | −2.29 (−2.44 to −2.15) |

| Southern Latin America | 19.22 (15.96 to 22.60) | 20.53 (17.36 to 24.24) | 0.28 (0.08 to 0.49) | 0.31 (0.27 to 0.34) | 0.28 (0.25 to 0.34) | −0.46 (−0.62 to −0.30) | 11.10 (9.69 to 12.66) | 10.06 (8.61 to 11.94) | −0.40 (−0.50 to −0.31) |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 10.44 (8.67 to 12.74) | 11.78 (9.83 to 14.31) | 0.53 (0.45 to 0.61) | 0.42 (0.33 to 0.53) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.51) | 0.25 (−0.16 to 0.65) | 15.11 (10.88 to 18.87) | 13.66 (11.37 to 15.90) | −0.12 (−0.44 to 0.20) |

| Tropical Latin America | 65.14 (57.26 to 74.08) | 47.34 (41.21 to 54.02) | −0.87 (−1.08 to −0.65) | 0.47 (0.41 to 0.51) | 0.44 (0.40 to 0.51) | 0.03 (−0.14 to 0.21) | 23.37 (19.94 to 27.30) | 19.26 (16.53 to 22.44) | −0.44 (−0.61 to −0.26) |

| Western Europe | 156.46 (139.89 to 173.69) | 188.22 (169.47 to 207.48) | 0.37 (0.26 to 0.48) | 0.82 (0.73 to 1.04) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.23) | 1.51 (1.27 to 1.75) | 39.24 (31.18 to 48.16) | 46.79 (36.98 to 57.57) | 0.59 (0.49 to 0.69) |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 8.49 (7.03 to 10.33) | 10.09 (8.38 to 12.23) | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.90) | 0.56 (0.33 to 0.91) | 0.5 (0.35 to 0.67) | −0.37 (−0.46 to −0.28) | 19.69 (11.64 to 30.47) | 16.77 (11.61 to 22.73) | −0.57 (−0.66 to −0.48) |

DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; EAPC, estimated annual percentage change; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; SDI, Socio-demographic Index; UI, uncertainty interval.

Figure 2.

The EAPCs in age-standardised rates of prevalence (A, B), deaths (C, D), and DALYs (E, F) due to IBD from 1990 to 2019, both sexes, by GBD region and by SDI quintile. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; EAPC, estimated annual percentage change; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SDI, Socio-demographic Index.

bmjopen-2022-065186supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

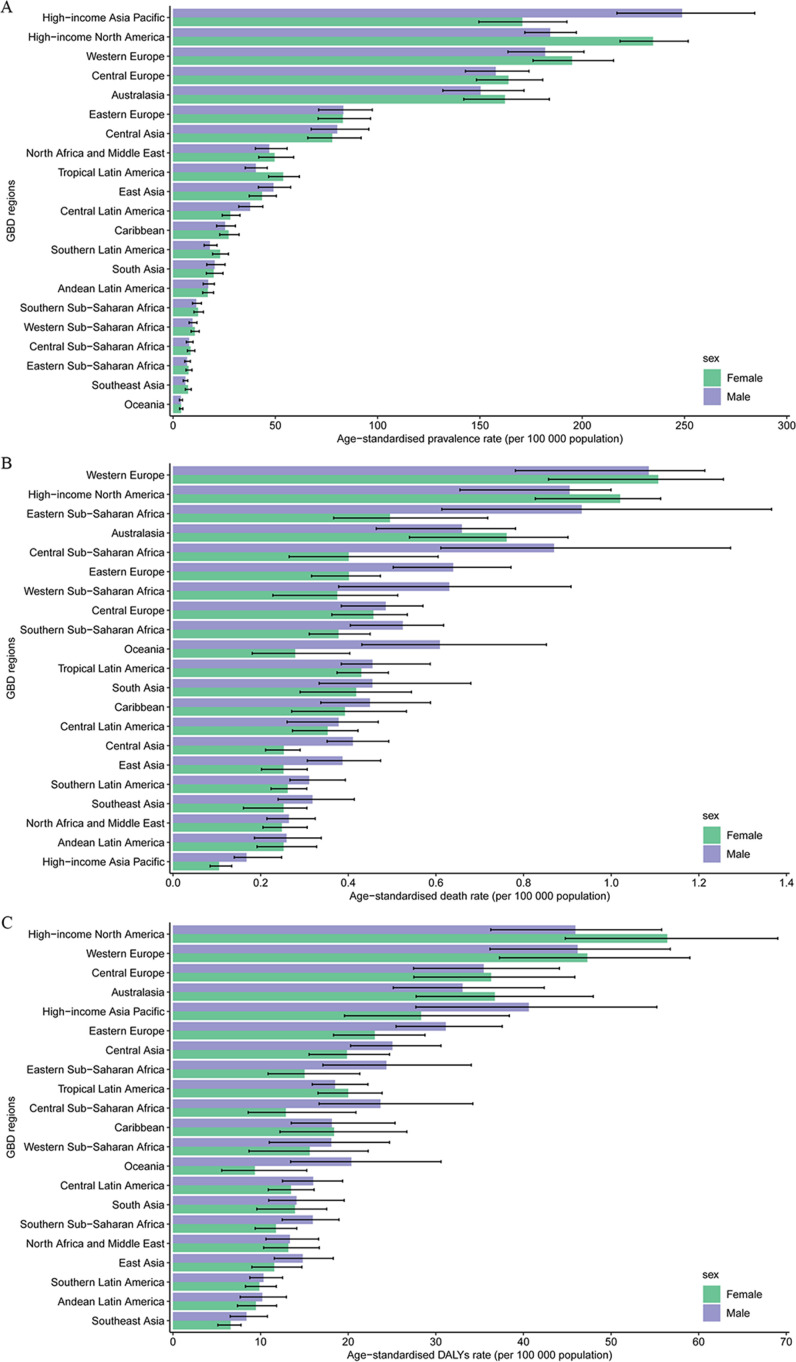

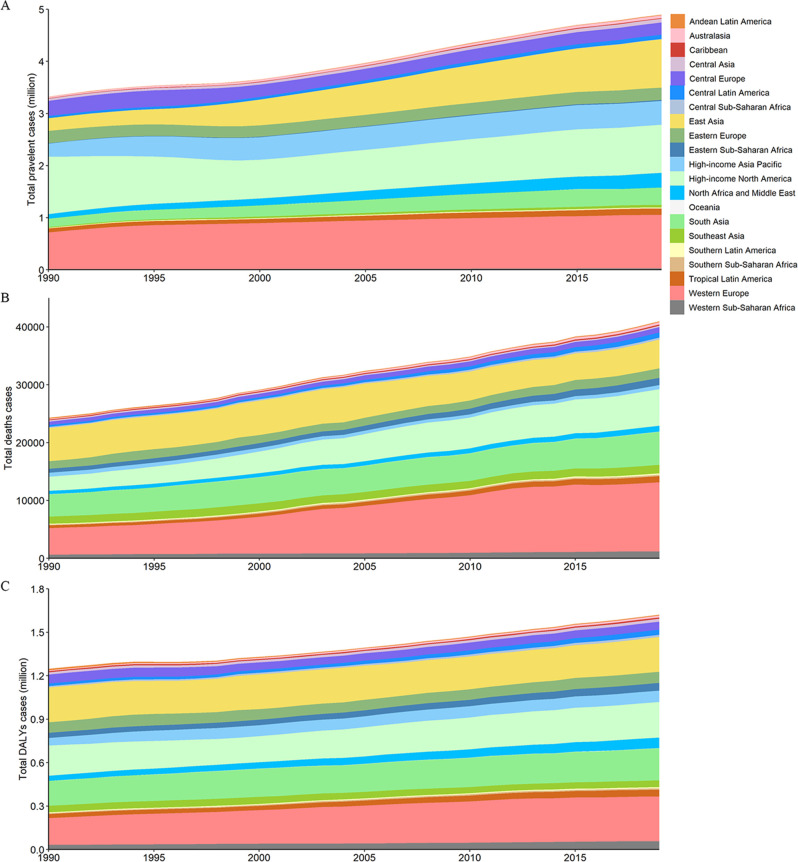

At the regional level in 2019, the largest number of prevalent cases was observed in Western Europe (1.03 million (95% UI 0.93 to 1.13)) (online supplemental table 1), and the highest age-standardised prevalence rate was observed in the high-income Asia Pacific region (210.54 per 100 000 people (183.69 to 239.68)) (figure 3A). From 1990 to 2019, an increase in total prevalent cases was seen across most GBD regions, as shown in figure 4A. However, the age-standardised prevalence rate increased in 13 GBD regions and decreased in 5 regions, with the highest upward trend in East Asia (EAPC=2.79 (95% CI 2.41 to 3.18)) and the largest decrease in high-income North America (EAPC=−1.32 (−1.75 to −0.89)) (figure 2B).

Figure 3.

The age-standardised rates of prevalence (A), deaths (B), and DALYs (C) due to IBD by sex, across 21 regions, in 2019. Error bars indicate the 95% uncertainty interval (UI) for the age-standardised rates. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Figure 4.

The absolute number of prevalent cases (A), deaths (B), and DALYs (C) due to IBD for all GBD regions from 1990 to 2019. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

At the national and territorial levels in 2019, China and the USA had the highest number of prevalent cases (911 405 (95% UI 776 347 to 1 069 533) and 762 890 (712 357 to 813 654), respectively) (online supplemental table 2 and figure 1A). In 2019, the highest age-standardised prevalence rates of IBD were observed in Norway (498.95 (429.41 to 570.55)) (online supplemental table 3 and figure 1B). Between 1990 and 2019, age-standardised prevalence rates showed an upward trend in 147 countries or territories, with the greatest increase in Taiwan (Province of China) (EAPC=4.29 (95% CI 3.71 to 4.86)) (figure 1C).

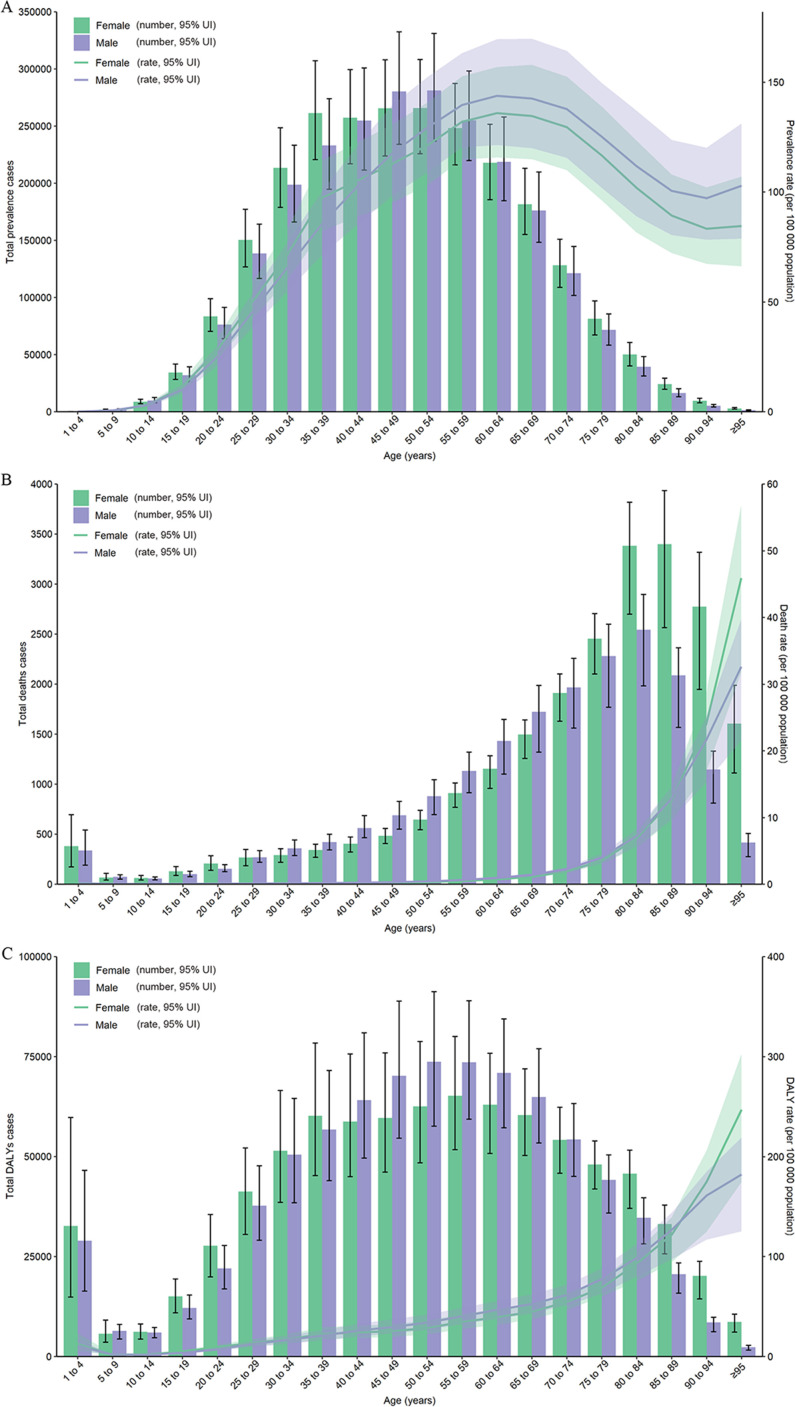

Overall, the global number of prevalent cases was higher among females than among males in 2019 (online supplemental table 1). The age-standardised prevalence rate was similar between males and females in 2019 (table 1). The highest peak IBD prevalence and age-specific prevalence rates occurred at ages 50–54 years and 60–64 years, respectively, among females and males in 2019 (figure 5A). From 1990 to 2019, the number of prevalent cases continued to increase for both sexes and was higher among females than among males in all years. The age-standardised prevalence rate decreased for both sexes during the same period (online supplemental figure 1).

Figure 5.

Age patterns by sex of the total number and age-standardised rates of prevalent cases (A), deaths (B) and DALYs (C) due to IBD at the global level in 2019. Error bars indicate the 95% uncertainty interval (UI) for the number of cases. Shading indicates the 95% UI for the rates. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Deaths related to IBD

In 2019, there were 40 998 deaths (95% UI 34 933 to 44 661) due to IBD worldwide, which increased by 68.75% (47.12% to 94.62%) from 24 295 (20 258 to 28376) in 1990 (online supplemental table 1 and online supplemental figure 2). The global age-standardised death rate was 0.54 per 100 000 people (0.46 to 0.59) in 2019, which decreased from 0.67 per 100 000 people (0.57 to 0.78) in 1990, with an EAPC of −0.69 (95% CI −0.81 to −0.57) (table 1, figure 2C and online supplemental figure 3−4).

At the regional level, Western Europe was also the region with the largest number of deaths (11 981 (95% UI 9244 to 13 315)) and the highest age-standardised death rate (1.11 per 100 000 people (0.87 to 1.23)) in 2019 (online supplemental table 1 and figure 3B). From 1990 to 2019, most GBD regions experienced an increase in total deaths from IBD (figure 4B). However, the age-standardised death rate declined in more than 60% of GBD regions, such as the high-income Asia Pacific region (EAPC=−4.29 (95% CI −4.64 to −3.93)), East Asia (EAPC = −3.98 (−4.33 to −3.63)) and Andean Latin America (EAPC=−2.74 (−3.16 to −2.32)) (figure 2D).

At the national and territorial levels in 2019, China and the USA also had the highest number of deaths (4676 (95% UI 3774 to 5461) and 5910 (4622 to 6464), respectively) (online supplemental table 2 and online supplemental figure 2). The Netherlands had the highest age-standardised death rate in 2019 (2.08 per 100 000 people (1.58 to 2.40)) (online supplemental table 3) and online supplemental figure 3). Between 1990 and 2019, more than 60% of countries or territories experienced a decrease in the age-standardised death rate of IBD, and the largest decrease was noted in the Republic of Korea (EAPC=−7.96 (−8.67 to −7.25)) (online supplemental figure 4).

Globally, the number of deaths was higher among females than among males in 2019 (online supplemental table 3). The age-standardised death rate was 0.56 per 100 000 people (95% UI 0.45 to 0.62) among males and 0.52 per 100 000 people (0.43 to 0.58) among females (table 1). In 2019, the highest number of deaths was observed among males aged 80–84 years and females aged 85–89 years, and the highest age-specific death rate was observed in the oldest age group (≥95 years) for both sexes (figure 5B). Between 1990 and 2019, deaths related to IBD also continued to increase for both sexes and were higher among females than among males in all years. However, the age-standardised death rate decreased for both sexes from 1990 to 2019 (online supplemental figure 5).

DALYs of IBD

Globally, 1.62 million (95% UI 1.36 to 1.92) DALYs, 0.73 million (0.49 to 0.99) YLD and 0.90 million (0.78 to 1.00) YLL were due to IBD in 2019, which increased from 1990 by 29.98%, 47.96% and 18.31%, respectively (online supplemental table 1), online supplemental table 4 and online supplemental figures 6−9). The global age-standardised DALY rate decreased from 27.20 per 100 000 people (21.70 to 32.39) in 1990 to 20.15 per 100 000 people (16.86 to 23.71) in 2019, with an EAPC of −1.04 (95% CI −1.06 to −1.01) (table 1, figure 2E and online supplemental figures 10−11). The same downward trend was found in the age-standardised YLL rate (EAPC=−1.33 (−1.37 to −1.30)) and the age-standardised YLD rate (EAPC=−0.62 (−0.70 to −0.53)) (online supplemental table 5 and online supplemental figures 12−14).

At the regional level, Western Europe had the greatest number of DALYs (310 691 (95% UI 2 55 911 to 3 71 106)) in 2019 (online supplemental table 1). The highest age-standardised DALY rates in 2019 were observed in high-income North America (51.27 per 100 000 people (95% UI 40.90 to 62.35)) (figure 3C). As shown in figure 4C, an increase in total DALYs was found across most GBD regions from 1990 to 2019. Most of the GBD regions had a downward trend in the age-standardised DALY rate, with the largest decrease in Andean Latin America (EAPC=−3.68 (95% CI −4.17 to −3.18)) (figure 2F).

At the national and territorial levels in 2019, China and the USA had the highest number of DALYs (232 464 (95% UI 179 903 to 291 090) and 215 289 (175 991 to 256 059), respectively) (online supplemental table 2 and online supplemental figure 6). The highest age-standardised DALY rate was observed in Norway in 2019 (80.37 per 100 000 people (56.25 to 108.56)) (online supplemental table 3 and online supplemental figure 10). From 1990 to 2019, more than 65% of countries or territories experienced a decrease in the age-standardised DALY rate of IBD, and the largest decrease was found in Peru (EAPC=−5.08 (95% CI −5.69 to −4.47)) (online supplemental figure 11).

In 2019, the global number of DALYs was also higher among females than among males (online supplemental table 1). The age-standardised DALY rate was 20.6 per 100 000 people (95% UI 17.2 to 24.3) among males and 19.7 per 100 000 people (16.2 to 23.5) among females (table 1). The number of DALYs was highest among males aged 50–54 years and females aged 55–59 years (figure 5C). The highest number of YLL occurred in the group aged 65–69 years (75 234, (63 865 to 83 022)), while the highest number of YLD occurred in the group aged 45–49 years (80 776, (53 187 to 113 688)) (online supplemental figure 15). As with prevalent cases and deaths, the DALYs continued to increase for both sexes and were higher among females than among males in all years from 1990 to 2019. The age-standardised DALY rate decreased for both sexes between 1990 and 2019 (online supplemental figure 16).

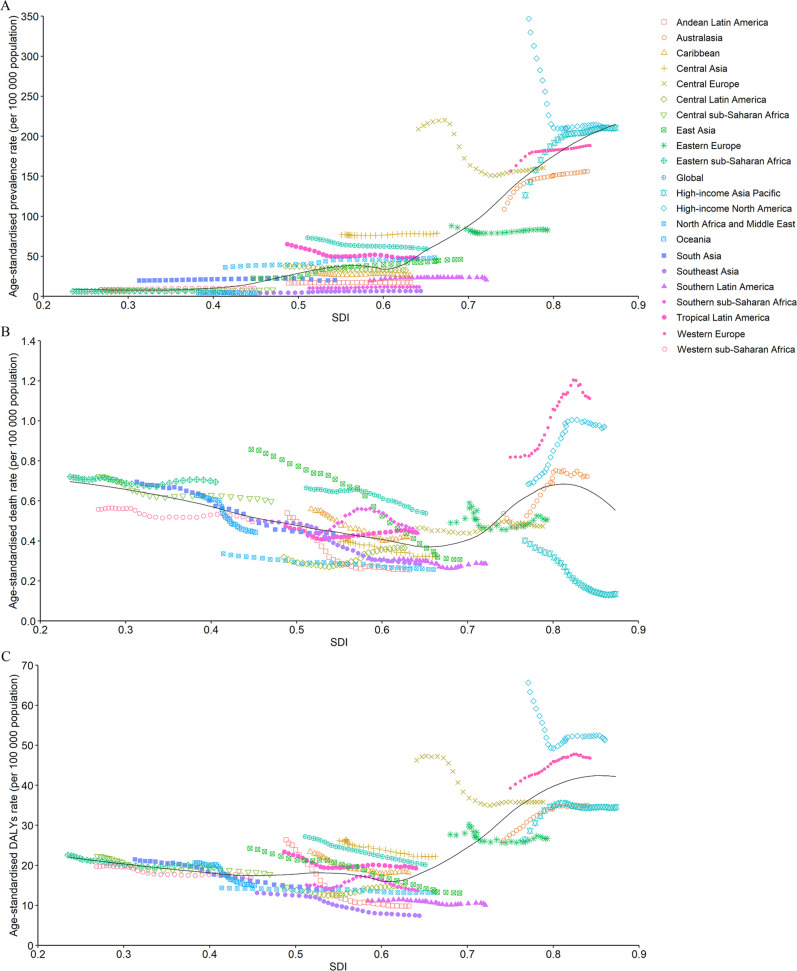

Burden of IBD by SDI

A higher SDI was associated with higher age-standardised prevalence rates of IBD, with values that were higher than the global rate in high and high-middle SDI quintiles and lower than the global rate in the other three SDI quintiles (table 1). The high-SDI quintile had the highest age-standardised prevalence rate, death rate and DALY rate in 2019. Between 1990 and 2019, the age-standardised death rate and age-standardised DALY rate decreased in all SDI quintiles except the high-SDI quintile, where they increased (EAPC=0.82 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.01)) and remained stable (EAPC=0.00 (−0.06 to 0.05)), respectively (table 1 and figure 2C, E). However, the age-standardised prevalence rate decreased in the high and high-middle SDI quintiles and increased in the other three SDI quintiles during the observation period (table 1 and figure 2A).

The observed global and regional age-standardised prevalence, death, and DALY rates in relation to SDI are shown in figure 6, expressed in the annual time series from 1990 to 2019. Regions generally followed the trend of increased death and DALY rates with a higher SDI. However, more than 60% of the regions showed an upward trend in the age-standardised prevalence rate during the study period. At the global level, the age-standardised prevalence, death, and DALY rates dropped with increasing SDI values but were above the expected levels during the past 30 years.

Figure 6.

The age-standardised rates of IBD prevalence (A), deaths (B), and DALYs globally and for 21 GBD regions by SDI from 1990 to 2019. The expected age-standardised rates in 2019 based solely on SDI were represented by the black line. For each region, points from left to right depict estimates from each year from 1990 to 2019. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SDI, Socio-demographic Index.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively analysed the temporal trend in IBD burden at the global, regional and national levels. GBD 2019 reported 4.90 million IBD cases worldwide in 2019 and 4.79 million in 2017, while GBD 2017 reported 6.85 million in 2017.16 This discrepancy could be partly attributed to the improved specificity of case definition since GBD 2019 adjusted administrative data inputs towards expected stringent diagnosis using previously published IBD data with ICD codes.11 In addition, GBD 2019 improved model fit prevalence and incidence by setting more plausible bounds on excess mortality rate and passing less-informative priors to lower levels of the geographical hierarchy in DisMod-MR 2.1.11 Indeed, the GBD 2019 study provides the most current overview of the burden of IBD. It incorporates more data sources, with some from regions not previously assessed, providing updated estimates on global IBD epidemiology.11 In addition, GBD 2019 updated the bias adjustment, which further improved data reliability.11 After these adjustments, our study confirmed two epidemiological shifts in IBD since 1990. The number of prevalent cases has increased globally since 1990, with China and the USA having the highest number of cases. The ASR of death and DALYs decreased, implying substantial improvements in IBD management. The changing trends and geographical patterns have implications for policy-makers to prioritise IBD management, especially in newly industrialised countries.

The highest age-standardised prevalence rates were observed in high-income North America, Western Europe and the high-income Asia Pacific region. This pattern was also shown in high-SDI countries such as Norway and Canada. This is consistent with several previous meta-analyses6 17 and might correlate with several risk factors for IBD.18 19 Heavily processed foods with low fibre and high fat content and sugar are a risk factor for decreased microbial species.20–22 Other risk factors include smoking, hygiene and latitude resulting in vitamin D/sun exposure.23 24 The largest reduction in the age-standardised prevalence rate was also observed in high-income North America, which was consistent with the results of some previous reports,6 25 indicating the shift in the epidemiological stages of IBD in Western countries.26 27

Despite increasing numbers of prevalent cases, the global age-standardised prevalence rate showed a downward trend. This discrepancy reflects the denominator effects of an increasing global population and age-specific effects.28 Coward et al29 reported that the prevalence rate among elderly individuals and adults was ten times greater than that among paediatric patients in Canada. The trend in the age-standardised prevalence rate differed substantially between GBD regions. The greatest upward trend was observed in East Asia. At the national level, China, with a total number of 911 405 IBD patients, was a prominent contributor to the total number of global IBD cases. This pattern is consistent with several previous reports,6 30 which is related mainly to urbanisation, industrialisation and cultural Westernisation in some areas of China.31 With epidemiological surveillance strategies shifting from paper records to electronic healthcare databases using ICD codes, advances in healthcare facilities such as the implementation of endoscopy32 and the detection and diagnosis of IBD have also increased.

IBD causes body disability.33 34 Consistent with a previous study,4 the age-standardised DALY and mortality rates showed a downward trend globally, especially in East Asia, likely resulting from improved treatment strategies, such as the early use of biological agents and patient support programmes.35 The introduction of biological agents improved quality of life and reduced the surgery rate.30 36 Unfortunately, the cost of biological therapy is considerable, estimated at more than US$25 000 per year.37 More attention should be given to optimising patient selection, dosing and withdrawal.

There are some limitations of our study. First, the accuracy of the estimated IBD burden largely depends on the availability and quality of data acquired, which could be partially compensated by statistical methods. However, in regions with scarce data, especially in low-SDI countries, estimates could only rely on predictive covariates or global trends with consideration of SDI level and data from a single country, which is less representative. Extra caution should be taken when interpreting data from these areas. Additional high-quality population-based studies should be performed, especially in countries with scarce data. Second, estimate discrepancies compared with the results of some of the previously published studies could be further improved, although GBD 2019 has improved model fit for prevalence and incidence, partly overcoming the discrepancies. For example, the prevalence rate in Canada was only 46–57 per 100 000 people in GBD 2017. However, a rate of approximately 520 per 100 000 people was reported by a previous large population-based study in Canada.38 GBD 2019 reported a rate of 357.73 per 100 000 people after adjustment. Third, UC-specific and CD-specific trends were not assessed due to the lack of relevant data. The association between IBD and certain risk factors should also be included in the future. Nevertheless, GBD 2019 provides the most up-to-date global IBD epidemiology estimates for the last three decades and implications for new hypotheses. It covers 204 countries. Therefore, GBD 2019 generates more representative data and can compensate for biases in individual studies.

Conclusions

Despite the reduction in ASRs of prevalence, deaths and DALYs, IBD will continue to be a major public health burden due to increasing numbers of prevalent cases worldwide. However, the trend has shifted substantially since 1990. Although the age-standardised prevalence rate has increased rapidly in newly industrialised countries, especially in East Asia, the incidence has stabilised or even decreased in Western countries such as those in high-income North America. The prevalence of IBD in newly industrialised countries is quickly approaching that in Western countries. More systematic epidemiological monitoring strategies, especially in low-SDI countries, and the integration of risk factors into the estimate model of the GBD Study would further facilitate IBD management. Our findings might help some policy makers justify medical resource allocation, especially in low-SDI countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation which support the related GBD 2019 studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: DZ and RW. Acquisition of data: ZL and SL. Data analysis and interpretation: RW, ZL, SL and DZ. Drafting the manuscript: DZ and RW. Critical revision of manuscript: all authors. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decisions to submit for publication. Guarantor: DZ.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82000527) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2022JJ30909).

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Because the study was based on publicly available dataset, this study was exempted by the ethics committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

References

- 1.Seyed Tabib NS, Madgwick M, Sudhakar P, et al. Big data in IBD: big progress for clinical practice. Gut 2020;69:1520–32. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:649–70. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel J-F, et al. Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients: a user’s guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology 2021;161:47–65. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: estimates from the global burden of disease 2017 study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:261–70. 10.1111/apt.15542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res 2019;2019:7247238. 10.1155/2019/7247238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017;390:2769–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalili H. The changing epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: what goes up may come down. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020;26:591–2. 10.1093/ibd/izz186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaborators G. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1160–203. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30977-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diseases GBD, Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborators G. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1250–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30750-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collaborators G. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1223–49. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborators G. Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1084–150. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31833-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcohol GBD, Drug Use C. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:987–1012. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng Y, Zhao P, Zhou L, et al. Epidemiological trends of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13:98. 10.1186/s13045-020-00915-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the gather statement. Lancet 2016;388:e19–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaborators G. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:17–30. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Manne S, Treem WR, et al. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric and adult populations: recent estimates from large national databases in the United States, 2007-2016. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020;26:619–25. 10.1093/ibd/izz182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Souza HSP, Fiocchi C, Iliopoulos D. The IBD interactome: an integrated view of aetiology, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:739–49. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng SC, Tsoi KKF, Kamm MA, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1164–76. 10.1002/ibd.21845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. A prospective study of long-term intake of dietary fiber and risk of crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2013;145:970–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014;514:181–6. 10.1038/nature13793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:290–8. 10.1007/s10620-014-3350-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:313–21. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Environmental, nutritional, and socioeconomic determinants of IBD incidence: a global ecological study. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:323–31. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao M, Gönczi L, Lakatos PL, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe in 2020. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:1573–87. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:56–66. 10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:720–7. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborators G. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1684–735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31891-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coward S, Clement F, Benchimol EI, et al. Past and future burden of inflammatory bowel diseases based on modeling of population-based data. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1345–53. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Y, Ren W, Liu Y, et al. Disease burden of inflammatory bowel disease in china from 1990 to 2017: findings from the global burden of diseases 2017. EClinicalMedicine 2020;27:100544. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su H-J, Chiu Y-T, Chiu C-T, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment in 2018: global and taiwanese status updates. J Formos Med Assoc 2019;118:1083–92. 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavlovic-Calic N, Salkic NN, Gegic A, et al. Crohn’s disease in tuzla region of Bosnia and Herzegovina: a 12-year study (1995-2006). Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23:957–64. 10.1007/s00384-008-0493-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shafer LA, Sofia MA, Rubin DT, et al. An international multicenter comparison of IBD-related disability and validation of the IBDDI. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:2524–31. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marinelli C, Zingone F, Inferrera M, et al. Factors associated with disability in patients with ulcerative colitis: a cross-sectional study. J Dig Dis 2020;21:81–7. 10.1111/1751-2980.12837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones JL, Nguyen GC, Benchimol EI, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: quality of life. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2(Suppl 1):S42–8. 10.1093/jcag/gwy048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frolkis AD, Lipton DS, Fiest KM, et al. Cumulative incidence of second intestinal resection in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1739–48. 10.1038/ajg.2014.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchetti M, Liberato NL. Biological therapies in Crohn’s disease: are they cost-effective? A critical appraisal of model-based analyses. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2014;14:815–24. 10.1586/14737167.2014.957682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, Guttmann A, et al. Changing age demographics of inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study of epidemiology trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1761–9. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-065186supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.