Abstract

Evaluating leaf day respiration rate (RL), which is believed to differ from that in the dark (RDk), is essential for predicting global carbon cycles under climate change. Several studies have suggested that atmospheric CO2 impacts RL. However, the magnitude of such an impact and associated mechanisms remain uncertain. To explore the CO2 effect on RL, wheat (Triticum aestivum) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus) plants were grown under ambient (410 ppm) and elevated (820 ppm) CO2 mole fraction ([CO2]). RL was estimated from combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements using the Kok method, the Kok-Phi method, and a revised Kok method (Kok-Cc method). We found that elevated growth [CO2] led to an 8.4% reduction in RL and a 16.2% reduction in RDk in both species, in parallel to decreased leaf N and chlorophyll contents at elevated growth [CO2]. We also looked at short-term CO2 effects during gas exchange experiments. Increased RL or RL/RDk at elevated measurement [CO2] were found using the Kok and Kok-Phi methods, but not with the Kok-Cc method. This discrepancy was attributed to the unaccounted changes in Cc in the former methods. We found that the Kok and Kok-Phi methods underestimate RL and overestimate the inhibition of respiration under low irradiance conditions of the Kok curve, and the inhibition of RL was only 6%, representing 26% of the apparent Kok effect. We found no significant long-term CO2 effect on RL/RDk, originating from a concurrent reduction in RL and RDk at elevated growth [CO2], and likely mediated by acclimation of nitrogen metabolism.

Combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements show a reduction in leaf day respiration to elevated atmospheric CO2, greatly impacting plant carbon budgets.

Introduction

Terrestrial vegetation assimilates ca. 120 pg carbon via photosynthesis but releases about half of assimilated carbon via respiration (Gifford, 2003; Dusenge et al., 2019). The balance between plant respiration and photosynthesis is therefore essential for plant productivity and global carbon balance. Despite considerable variations depending on N fertilization and climatic conditions, the ongoing increase in atmospheric CO2 mole fraction ([CO2]) promotes leaf photosynthesis and primary production, which is referred to as the “CO2 fertilization effect” (Drake et al., 1997; Cramer et al., 2001). Although the CO2 fertilization effect on biomass (but not necessarily yield) is evident from greenhouse and field experiments (Ainsworth and Long, 2005; Norby et al., 2005; Walker et al., 2021), the response of plant respiration to [CO2] is rather uncertain, limiting our ability to predict future climate change-driven modifications of plant physiology.

The respiratory response is complicated by the fact that leaf respiration takes place not only in darkness (the respiration rate is denoted as RDk), but also in the light. In illuminated leaves, respiration is referred to as “respiration in the light” or “day respiration” (denoted as RL; here we refer to CO2 evolution rather than O2 consumption). Leaf respiration has been shown to be partially inhibited by the light although the magnitude of inhibition varies broadly, with reported RL/RDk values ranging from 0.2 to 1.3 (Ayub et al., 2011; Griffin and Turnbull, 2013; Crous et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2018; Way et al., 2019). Given the longer light periods during the growing season and higher temperature during the day than at night in most ecosystems, RL is a key component of plant- and community-scale carbon budgets (Atkin et al., 2007; Gong et al., 2017). Experimental results revealed that the inhibition of respiration by light (i.e. 1−RL/RDk) also occurs at the stand scale (Gong et al., 2017). Neglecting respiration inhibition might have led to considerable errors in estimated gross primary production (Wehr et al., 2016; Gong et al., 2017). Furthermore, the response of RL to environmental cues are essential to predict carbon balance, carbon-use efficiency, and improve land surface models (Wehr et al., 2016; Atkin et al., 2017; Tcherkez et al., 2017b; Keenan et al., 2019).

So far, there is no consensus on the response of RL to long-term [CO2] increase. Some studies have shown that RL is stimulated by elevated growth [CO2] (Wang et al., 2001; Shapiro et al., 2004; Crous et al., 2012; Griffin and Turnbull, 2013), and this effect may be related to higher carbohydrate concentrations in leaves (Rogers et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2017). Also, increased leaf respiration at elevated [CO2] has been suggested to be associated with a larger mitochondrial number per mesophyll cell (Griffin et al., 2001), indicating cellular and transcriptional (gene regulation) mechanisms of respiratory control (Leakey et al., 2009). Other studies have reported a decrease in RL in plants grown under elevated [CO2] compared with that grown under ambient [CO2] (Ayub et al., 2011; Ayub et al., 2014).

The decrease in RL at elevated [CO2] has been suggested to be linked to either photorespiration or nitrogen metabolism. Under elevated CO2, there is a reduction in photorespiration rate (and the rate of oxygenation of RuBP, vo), and this could cause an alteration in RL, as suggested by results obtained on short-term changes in respiratory metabolism under varying CO2 mole fraction. In effect, using 13C-enriched substrates to trace decarboxylation processes, Tcherkez et al. (2008) found that decarboxylation decreased when leaves were exposed to elevated [CO2] for short periods. Likewise, results obtained using the Kok method suggested there was a linear relationship between photorespiration rate and RL (Griffin and Turnbull, 2013). However, the mechanism behind this relationship is still unclear. In particular, the Kok effect itself has been shown not to be fully caused by changes in respiration rate (Gauthier et al., 2020), and thus, the relationships between photorespiration and Kok method-based RL are presently uncertain. In addition, RL has been reported to either decrease (Pinelli and Loreto, 2003; Tcherkez et al., 2008; Griffin and Turnbull, 2013), increase (Yin et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2022), or remain unaffected (Sharp et al., 1984; Tcherkez et al., 2012), in the short-term using gas exchange experiments at elevated [CO2]. Thus, conclusions drawn from short-term changes in RL caused by instantaneous elevation of [CO2] might not be relevant to long-term changes in RL.

The decrease of RL at elevated [CO2] has also been suggested to be linked to nitrogen metabolism. It has been observed in many free air CO2 enrichment (FACE) experiments that elevated [CO2] reduces leaf N content, which is accompanied by a down-regulation of photosynthetic capacity (Long et al., 2004; Ainsworth and Long, 2005). It is believed that elevated [CO2] inhibits N assimilation in leaves via the potential link between photorespiration and nitrate assimilation (Bloom et al., 2010, 2014; Busch et al., 2018). Given that N assimilation in leaves is energy demanding and thus a driving factor for leaf respiration (Amthor, 2000; Reich et al., 2008), it would be important to know whether [CO2] affected RL and RDk via leaf N content. All in all, the response of RL to elevated [CO2] appears to be highly variable and mechanisms behind are unclear.

Another uncertainty associated with RL and how it varies is technological. In fact, there are several methods to estimate RL, but none of them can measure RL directly (for a review, see Tcherkez et al., 2017b). The Kok method (Kok, 1949) and the Laisk method (Laisk, 1977), the two most commonly used methods, require manipulation of net CO2 assimilation rates (A) at low irradiances (Iinc < 150 μmol m−2 s−1) (Kok) or low CO2 (Laisk). Another method, the 13C isotopic disequilibrium method, uses two CO2 sources with different δ13C values to disentangle RL and photosynthesis under physiologically relevant environmental conditions without the need to manipulate A (Gong et al., 2015, 2018). The 13C disequilibrium method is valuable since it does not require the use of low irradiance or low CO2 and can be performed at any CO2 mole fraction, and therefore, is suitable to study CO2 effects on RL. It is, however, technically demanding (isotopic CO2 sources, mass spectrometers). The Laisk method is, by definition, not suitable for studying CO2 effects because it manipulates [CO2] at sub-ambient levels. So far, the response of RL to [CO2] has mainly been estimated using the Kok method. However, as mentioned above, the Kok method has been questioned since the Kok effect is not exclusively caused by a decrease in respiration rates (Gauthier et al., 2020). Several studies showed that the Kok method has conceptual uncertainties (Farquhar and Busch, 2017; Tcherkez et al., 2017a, 2017b; Yin et al., 2020). First, the Kok method assumes a constant photochemical efficiency of PSII (Φ2) along the A–Iinc curve (i.e. the Kok curve, see Theory). To address this issue, Yin et al. (2009) suggested to use measured Φ2 to improve the RL estimation. Second, the Kok method usually disregards variation in chloroplastic [CO2] (Cc) along the A–Iinc curve, which could bias the estimates of RL according to recent studies based on model analysis (Farquhar and Busch, 2017; Yin et al., 2020). Estimating Cc along the A–Iinc curve requires measurements of mesophyll conductance (gm). Measuring gm is challenging and this is particularly true when measurements are performed at low irradiance (Pons et al., 2009; Gu and Sun, 2014; Gong et al., 2015). So far, the uncertainty associated with Cc has not been fully solved.

Taken as a whole, neither long-term nor short-term responses of RL to CO2 mole fraction are well-known, and technologies used to measure RL may be problematic. Here, we intend to address the following questions: (1) How do short-, medium-, and long-term CO2 enrichment affect RL in C3 leaves? (2) Do the original and revised Kok methods provide similar estimations of RL? To this end, we combine gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence (ChF) measurements to study the response of RL of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) plants grown under ambient (410 ppm) and elevated [CO2] (820 ppm). We assessed the medium-to-long term CO2 response (days to months) by comparing parameters of plants at different growth [CO2], and the short-term CO2 response (minutes) by measuring the same leaves at 410 and 820 ppm of [CO2]. We compared RL estimated by the Kok method, the Yin method (i.e. the Kok-Phi method) and a revised Kok method (i.e. the Kok-Cc method) which takes the influence of Φ2 and Cc into account.

Results

Effects of growth CO2 on photosynthetic parameters and leaf traits

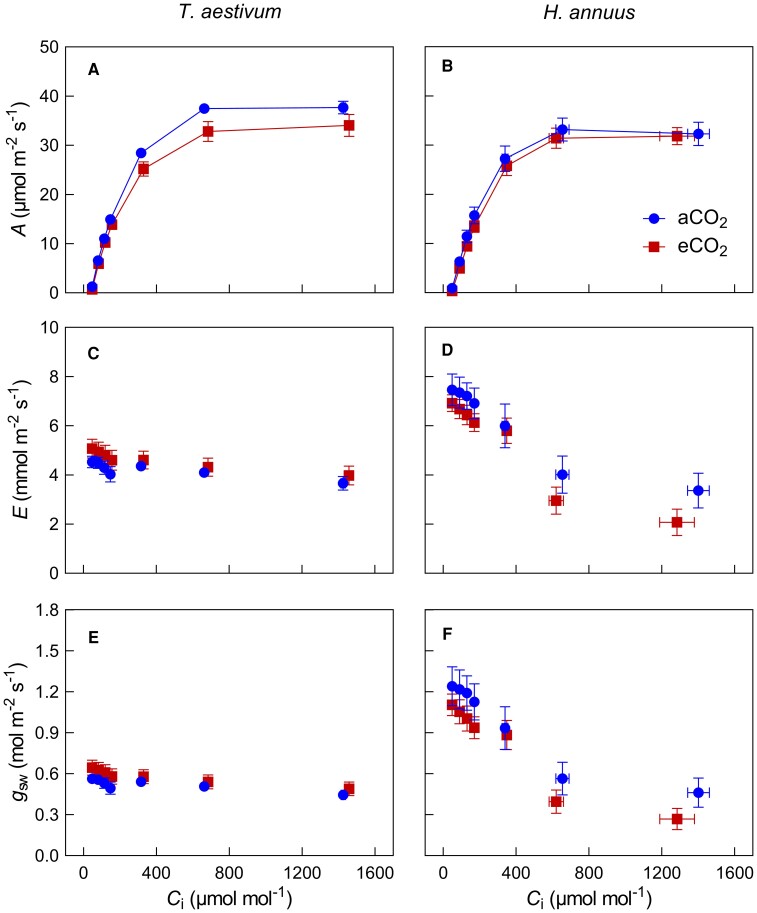

Growth at elevated [CO2] led to a reduction in net CO2 assimilation (A) for both species, when A values were compared at the same intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) levels (Figure 1, A and B). Sunflower plants grown at elevated [CO2] exhibited lower E and gsw compared with that grown at ambient CO2 (Figure 1, D and F). This effect on water vapor exchange was minor in wheat (Figure 1, C and E). In order to assess the long-term growth CO2 effect on common grounds, gas exchange parameters of leaves were compared at their respective growth [CO2] (indicated by the subscript “growth”). Net CO2 assimilation rate (Agrowth), intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUEgrowth), and leaf carbon-use efficiency (CUEL) of plants grown under elevated [CO2] were significantly higher than those of plants grown under ambient [CO2] in both species (Table 1). Averaged across species, growth at elevated [CO2] led to 5.6% reduction in Amax, 7.9% reduction in Vcmax, and 8.0% in J, indicating a decline in photosynthesis capacity. The ratio of gsc to gm was not significantly affected by growth [CO2] or species. RDk of both species was lower at elevated [CO2] but this decrease differed between species (20% for wheat and 11% for sunflower).

Figure 1.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A), transpiration rate (E), and stomatal conductance for water vapor (gsw) in response to short-term variation of intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus). Circles refer to ambient (410 μmol mol−1) growth CO2, and squares refer to elevated (820 μmol mol−1) growth CO2. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 6).

Table 1.

Leaf traits and photosynthetic parameters of wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus) grown under ambient or elevated CO2 (aCO2 or eCO2)

| T. aestivum | H. annuus | Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aCO2 | eCO2 | aCO2 | eCO2 | spe | CO2 | spe × CO2 | |

| A growth | 28.42 ± 0.73 | 32.79 ± 2.01 | 27.27 ± 2.57 | 31.43 ± 2.06 | 0.529 | 0.042 | 0.956 |

| A max | 37.68 ± 1.29 | 34.04 ± 2.22 | 32.32 ± 2.40 | 31.83 ± 1.73 | 0.068 | 0.304 | 0.430 |

| R Dk | 2.26 ± 0.14 | 1.81 ± 0.17 | 1.48 ± 0.11 | 1.32 ± 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.327 |

| iWUEgrowth | 52.64 ± 1.30 | 62.25 ± 3.94 | 37.30 ± 10.25 | 102.14 ± 24.99 | 0.380 | 0.013 | 0.057 |

| SLA | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.038 | 0.252 | 0.511 |

| N% | 6.61 ± 0.17 | 6.39 ± 0.11 | 3.51 ± 0.67 | 3.16 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.527 | 0.882 |

| Narea | 2.70 ± 0.06 | 2.37 ± 0.10 | 1.53 ± 0.18 | 1.35 ± 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.062 | 0.586 |

| Chl | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.083 |

| V cmax | 160.9 ± 3.2 | 142.7 ± 13.0 | 123.0 ± 11.7 | 117.4 ± 3.3 | 0.002 | 0.203 | 0.493 |

| J | 183.4 ± 3.3 | 160.1 ± 9.3 | 164.2 ± 10.4 | 158.9 ± 8.6 | 0.234 | 0.101 | 0.293 |

| g sc/gm | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 1.16 ± 0.07 | 1.74 ± 0.55 | 1.97 ± 0.42 | 0.087 | 0.222 | 0.859 |

| CUEL | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.547 |

Leaf trait parameters include: specific leaf area (SLA, cm2 mg−1), leaf nitrogen content per dry mass (N%), leaf nitrogen content per area (Narea, g m−2), chlorophyll content (Chl, g m−2). Photosynthetic parameters include net CO2 assimilation rate at the growth CO2 (Agrowth, μmol m−2 s−1), maximum CO2 assimilation rate (Amax, μmol m−2 s−1), respiration rate in the dark (RDk, μmol m−2 s−1), intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUEgrowth, μmol mol−1), maximum carboxylation rates by Rubisco (Vcmax, μmol m−2 s−1), electron transport rate (J, μmol m−2 s−1), the ratio of stomatal conductance for CO2 to mesophyll conductance (gsc/gm), leaf carbon-use efficiency (CUEL). Data are mean ± SE (n = 6); significant treatment effects (P < 0.05) tested with two-way ANOVAs are shown in bold.

Leaf chlorophyll content was significantly lower at elevated [CO2] compared with ambient [CO2]. Similarly, elevated [CO2] led to a 6.7% reduction (averaged across species) in nitrogen elemental content (N%) and a 12% reduction in nitrogen content per surface area (Narea) on average, but the effect of CO2 was not significant at a P-level of 0.05. SLA was significantly different between species but not affected by growth [CO2] (Table 1).

CO2 response of RL estimated by different methods

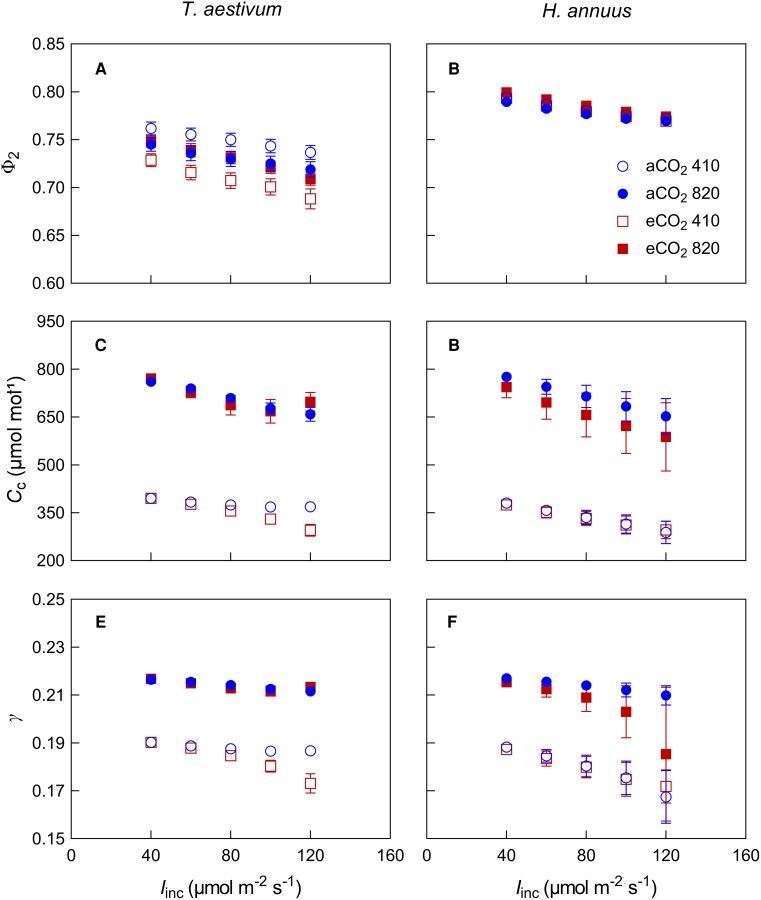

Φ2, Cc, and γ, the key parameters associated with assumptions in both original and revised Kok methods, were found to decrease along the Kok curve in all species and treatments (Figure 2). With the increase of Iinc from 40 to 100 μmol m−2 s−1, Φ2 decreased by 3.1% for wheat and 2.4% for sunflower and this trend was not substantially influenced by growth [CO2] (long-term effect) and measurement [CO2] (short-term effect). A short-term CO2 effect on γ was detected, i.e. γ decreased more strongly at measurement [CO2] of 410 ppm (by 5.2%) than that at measurement [CO2] of 820 ppm (by 3.0%, averaged across species) with the increase in Iinc (Supplemental Figure 1). That is, under our conditions, terms (γfaetΦ2ρ2α) in Equation 3 and (γfaetρ2α) in Equation 4 were not constant along a Kok curve, causing errors in RL estimated by the Kok and the Kok-Phi methods, respectively.

Figure 2.

Photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Φ2), chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc), and γ (the lumped parameter in Equation 2) in response to incident irradiance (Iinc) for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus). Plants grown under ambient CO2 (aCO2, circles) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, squares) were measured at gaseous conditions of 410 μmol mol−1 (open symbols) or 820 μmol mol−1 (closed symbols) CO2 in the leaf chamber. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 6).

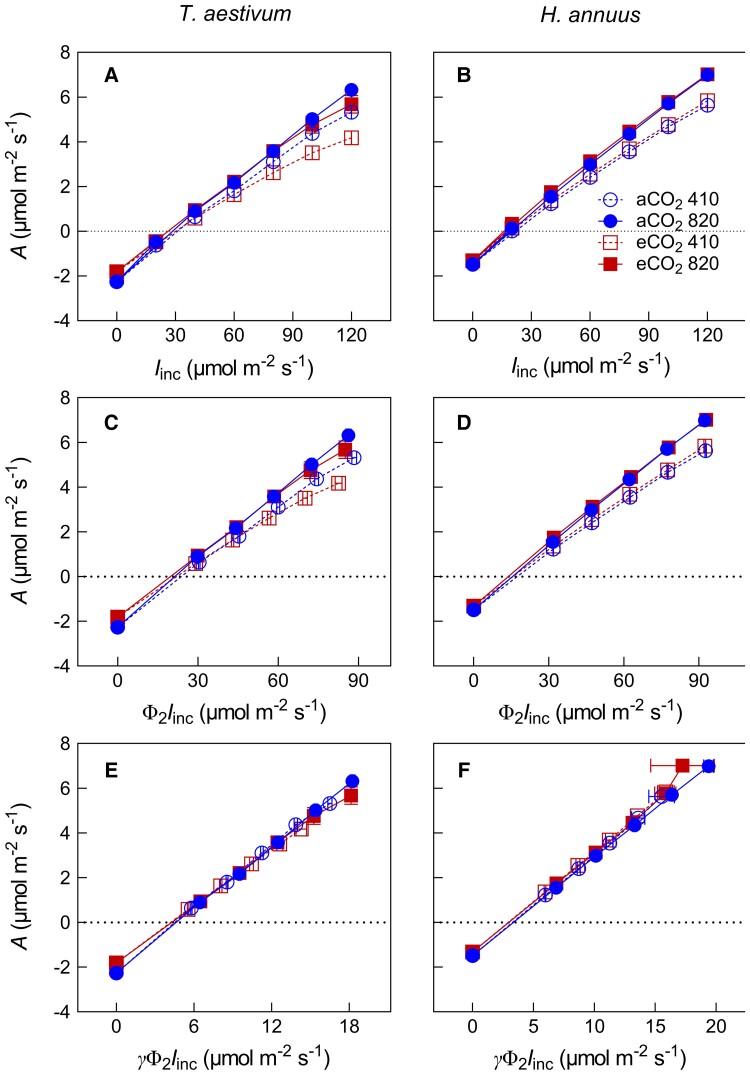

Applying the Kok, the Kok-Phi, and the Kok-Cc methods, A was plotted against Iinc, Φ2Iinc, and γΦ2Iinc, respectively (Figure 3). Both growth [CO2] and measurement [CO2] had impacts on A–Iinc and A–Φ2Iinc response curves (Figure 3, A–D). As a result, growth at elevated [CO2] led to a significant decrease in RL Kok and RL Kok-Phi. The same was true for RL Kok-Cc on average but it was only significant with a P-value of 0.06 (Figure 4 and Table 2). There was a clear, although statistically insignificant (P > 0.05), tendency for elevated measurement [CO2] to increase both RL Kok and RL Kok-Phi (Figures 3 and4) in both species. By contrast, A–γΦ2Iinc curves obtained under different measurements [CO2] seemed to coincide perfectly (Figure 3, E and F), in agreement with the insignificant effect of measurement [CO2] on RL Kok-Cc.

Figure 3.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) in response to Iinc (incident irradiance), Φ2Iinc (Φ2, photochemical efficiency of photosystem II) or γΦ2Iinc (γ, the lumped parameter in Equation 2) for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus). Data are mean ± SE (n = 6). Meaning of symbols of different CO2 treatments and measurement conditions are shown in Figure 2.

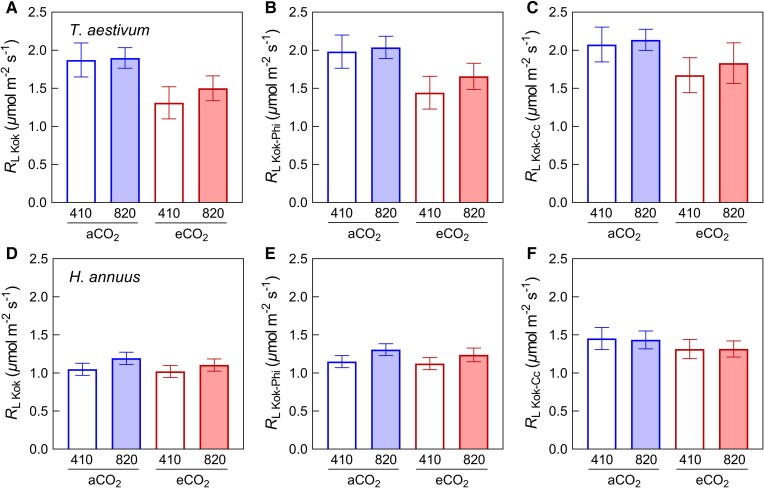

Figure 4.

Effects of growth CO2 treatments (aCO2 and eCO2) and measurement conditions (410 and 820 ppm CO2) on respiration rates in the light (RL) estimated by three methods for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus). RL was measured by the Kok (A and D), Kok-Phi (B and E), and Kok-Cc (C and F) methods. Data are mean ± SE (n = 5–6). The results of ANOVA tests are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

ANOVA tests for RL estimated by the Kok, Kok-Phi, and Kok-Cc methods

| Source | df | R L Kok | R L Kok-Phi | R L Kok-Cc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | ||

| Species | 1 | 28.36 | <0.001 | 29.74 | <0.001 | 20.06 | <0.001 |

| Growth CO2 | 1 | 6.681 | 0.013 | 5.777 | 0.021 | 3.921 | 0.055 |

| Measurement CO2 | 1 | 1.227 | 0.275 | 1.714 | 0.198 | 0.198 | 0.658 |

| Growth CO2 × Measurement CO2 | 1 | 0.092 | 0.763 | 0.107 | 0.745 | 0.072 | 0.790 |

Significant treatment effects (P < 0.05) are shown in bold.

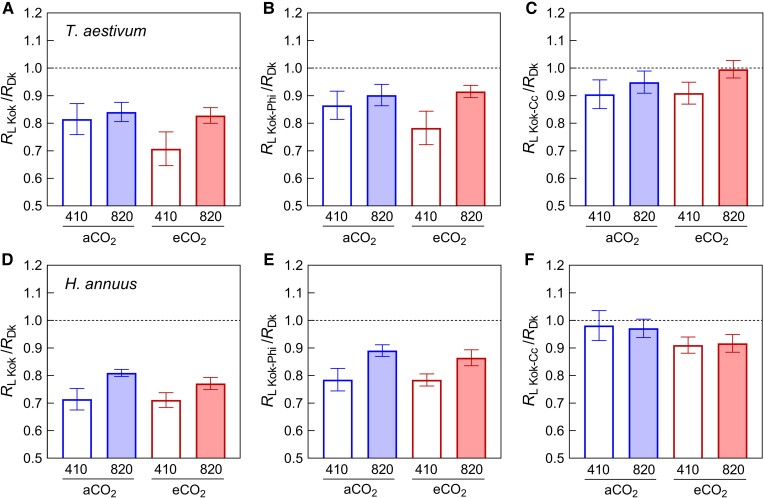

CO2 response of RL/RDk estimated by different methods

We found no significant long-term CO2 effect on RL/RDk estimated via all three methods (Table 3). There is a tendency that RL/RDk of wheat increased with the growth [CO2] for all three methods (comparing aCO2-410 and eCO2-820), while that tendency was not found in sunflower. That is, the long-term CO2 effect on RL/RDk is not conclusive. Under elevated measurement [CO2], significant increases in RL Kok/RDk and RL Kok-Phi/RDk were observed, but this short-term response was not observed using the Kok-Cc method (Figure 5). These results indicate that the short-term CO2 effect on RL Kok and RLKok-Phi could result from a technical bias simply due to neglecting the change in Cc along the Kok curve.

Table 3.

ANOVA tests for RL/RDk estimated by the Kok, Kok-Phi, and Kok-Cc methods

| Source | df | R L Kok/RDk | R L Kok-Phi/RDk | R L Kok-Cc/RDk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | ||

| Species | 1 | 2.824 | 0.101 | 1.638 | 0.208 | 0.095 | 0.759 |

| Growth CO2 | 1 | 2.216 | 0.144 | 0.799 | 0.377 | 0.389 | 0.536 |

| Measurement CO2 | 1 | 7.480 | 0.009 | 10.410 | 0.003 | 1.140 | 0.292 |

| Growth CO2 × Measurement CO2 | 1 | 0.328 | 0.570 | 0.441 | 0.511 | 0.243 | 0.625 |

Significant treatment effects (P < 0.05) are shown in bold.

Figure 5.

Effects of growth CO2 treatments (aCO2 and eCO2) and measurement conditions (410 and 820 ppm) on ratio of respiration in the light to respiration in the dark (RL/RDk) for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus). RL/RDk was estimated by the Kok (A and D), Kok-Phi (B and E), and Kok-Cc (C and F) methods. Data are mean ± SE (n = 5–6). The results of ANOVA tests are shown in Table 3.

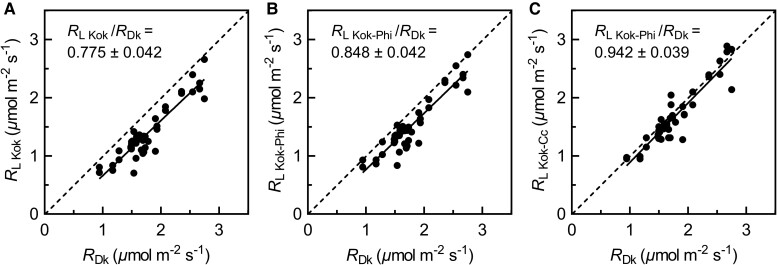

When pooling all data across species and treatments together, RDk was positively correlated to RL Kok (r2 = 0.82, P < 0.05), RL Kok-Phi (r2 = 0.82, P < 0.05), and RL Kok-Cc (r2 = 0.77, P < 0.05) (Figure 6). These linear regressions yielded an average RL Kok/RDk of 0.78 ± 0.04(SE), RL Kok-Phi/RDk of 0.85 ± 0.04, and RL Kok-Cc/RDk of 0.94 ± 0.04. That is, the Kok-Cc method showed a small light-induced inhibition of respiration, of 6% only, thus much lower than inhibition values from the other two methods (22%, 15%).

Figure 6.

Correlation between respiration in the dark (RDk) and respiration in the light (RL). RL was measured by the Kok (A), Kok-Phi (B), and Kok-Cc (C) methods. The average RL/RDk (±SE, n = 45) was calculated by pooling over the data of species (wheat and sunflower) and CO2 treatments. Gray dashed lines give the 1:1 relationship.

Discussion

Growth at elevated CO2 leads to reduction in RL

This study showed that RL of plants grown at elevated [CO2] was lower than that at ambient [CO2], and this result was confirmed by all three methods: Kok, Kok-Phi, and Kok-Cc. On average, elevated [CO2] led to an 8.4% reduction in RL, regardless of the method. This is in agreement with previous findings that leaf RL of plants grown at elevated [CO2] is lower (Ayub et al., 2014) despite opposite findings (Wang et al., 2001; Shapiro et al., 2004).

Interestingly, although a long-term CO2 effect on RL was evident, elevated [CO2] had no influence on the RL/RDk ratio, because RDk was also significantly lower at elevated [CO2]. Similar to our study, there was no significant long-term CO2 effect on RL/RDk in Sydney blue gum (Eucalyptus saligna) (Ayub et al., 2011; Crous et al., 2012). However, Wang et al. (2001), Shapiro et al. (2004), and Gong et al. (2017) found that nonproportional changes in RL and RDk led to a higher RL/RDk ratio in common cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium) leaves and sunflower stands grown at elevated [CO2]. By contrast, RL/RDk was reduced by elevated growth [CO2] in wheat because RL declined (Ayub et al., 2014) or RDk increased (Griffin and Turnbull, 2013). Presumably, variations in the response to growth CO2 between species and conditions might be linked to differences in nutrient content, metabolism, protein content, etc., which are all related to respiration.

The long-term response of RL to CO2 is associated with changes in leaf N status

Leaf N has long been suggested to be a key parameter influencing respiration rate, and used to estimate leaf respiration in vegetation models (Atkin et al., 2017). In our study, the reduction in RL and RDk was associated with a decrease in Narea and chlorophyll content, suggesting that leaf N effectively drives the respiration rate. Nitrate reduction and maintenance of proteins are energy-consuming (Wullschleger et al., 1997). Lower N content implies lower energy requirements and thus lower growth and maintenance respiration.

It has often been found in FACE or growth cabinet experiments that leaf N content was lower at elevated [CO2]. This has been explained by different mechanisms. For example, elevated [CO2] was shown to cause a decrease in stomatal conductance of leaves, leading to decreasing transpiration rates (Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007) and thus, lower transpiration-driven mass flow of soil N to roots and stems (so-called transpiration mechanism (McGrath and Lobell, 2013; Feng et al., 2015)). Another mechanism is associated with photorespiration. Generally, N assimilation is believed to be lower due to lower photorespiration (Bloom et al., 2010), which is accompanied by the reduced reductant supplied via photorespiration at elevated [CO2] (Taub and Wang, 2008). Furthermore, a “dilution effect” could occur whereby N uptake does not increase proportionally to the increase of biomass at elevated [CO2] (Feng et al., 2015).

The decreased leaf N content at elevated [CO2] has also consequences on photosynthetic capacity (i.e. Vcmax). It was reported that species grown under elevated [CO2] had lower maximum apparent carboxylation velocity (Vcmax) and carboxylation efficiency (Ainsworth and Long, 2005). Finally, elevated [CO2] significantly increased CUEL by enhancing photosynthetic rate and reducing dark respiration. Gong et al. (2017) reported that CUE of sunflower stands was higher at 200 ppm growth [CO2] than that of 1000 ppm growth [CO2]. This results thus could not be explained by the response of CUEL itself since at the leaf level, CUEL likely increased at elevated growth [CO2]. We speculate that the reduction of whole plant CUE in their study was mainly due to enhanced respiration of heterotrophic organs or exudation.

Changes in Φ2 and Cc are involved in the Kok effect and impact on RL estimates

Our study found a short-term CO2 effect on RL estimated using the Kok and Kok-Phi methods, but no effect using the Kok-Cc method. In fact, both Kok and Kok-Phi methods showed an increase in RL when measured at elevated [CO2]. This short-term response is in agreement with the finding of Yin et al. (2020) and Fang et al. (2022), but is not supported by the findings of other studies (Tcherkez et al., 2008; Griffin and Turnbull, 2013). We believe that discrepancies in short-term CO2 effect on RL are mostly associated with methodological differences. As shown in the Theory section, the classical Kok method has conceptual uncertainty with the assumption that Φ2 remains constant across the Kok curve. This assumption must be rejected as Φ2 decreases with increasing Iinc (Figure 2). However, this short-term CO2 effect on RL cannot be explained by changes in Φ2 because (1) the decrease in Φ2 along the Kok curve was similar at both measurement [CO2] and (2) the effect persisted when the Kok-Phi method was used to account for variation in Φ2.

Another assumption that has been made for both the Kok and Kok-Phi methods is that γ (determined by Γ*/Cc) remains constant throughout the Kok curve. This assumption has also been challenged in recent model analyses (Buckley et al., 2017; Farquhar and Busch, 2017), but the question is how to quantify the change in Cc as this requires gm estimates. Here, we used species-specific gsc/gm ratios to calculate Cc, suggesting that Cc and γ decreased with increasing Iinc. Importantly, measurement CO2 influenced the trend of γ with increasing Iinc, which might be the origin of this short-term CO2 effect on RL Kok and RL Kok-Phi. When changes in γ (or Γ*/Cc) are accounted for, the apparent short-term effect of CO2 on RL, as found with the Kok and Kok-Phi methods, became insignificant (see also Figures 3 and4).

Kok- and Kok-Phi-based estimates of RL suppression are overestimates

The inhibition of RL by light is supported by biochemical evidence. Utilizing 13C labeling, flux calculations suggest that decarboxylation rates associated with glucose catabolism and activation of malic enzyme increase with decreasing irradiance in the irradiance region where the Kok effect occurs (Gauthier et al., 2020). Recently, how much of the Kok effect is associated with respiration has been under debate (Farquhar and Busch, 2017; Gauthier et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2020). Indeed, the methods used in the present study show different levels of inhibition of respiration by light. The average RL/RDk was 0.78 for the Kok method, 0.85 for the Kok-Phi method, and 0.94 for the Kok-Cc method. That is, the change in Φ2, γ (or Γ*/Cc), and real light inhibition of RL explained ca. 32%, 42% and 26% of the apparent Kok effect (i.e. the apparent 23%-inhibition of RL found with the classical Kok method), respectively. This is in agreement with the results of previous model analyses which show that the Kok effect is not purely respiratory (Farquhar and Busch, 2017; Yin et al., 2020), and both the Kok method and the Kok-Phi method underestimated RL and overestimated the inhibition of RL (Yin et al., 2020).

The real light inhibition of RL (as revealed by the Kok-Cc method) was only 6%, which is close to the mean inhibition of 8% of several herbaceous species determined using the 13C disequilibrium method (Gong et al., 2018) and the mean inhibition of 10% in wheat leaves determined using a nonrectangular hyperbolic model to interactively solve gm and RL (Fang et al., 2022). In line with these results, a break point in the linear section of the photosynthetic response curve could hardly be seen in the Kok-Cc plots (Figure 3, E and F).

The Kok-Cc method developed here requires gsc/gm to estimate Cc along a Kok curve since Cc cannot be directly measured. Estimating gm under low light remains technically very challenging. We used species-specific gsc/gm values measured under the growth condition to estimate gm at each step of Kok curves. A similar approach has been applied to estimate Cc to improve the Laisk method (Gong et al., 2018; Way et al., 2019). These calculations assume that gsc/gm was the same under the measurement condition of the Kok method and the growth condition. In another word, gsc and gm should decrease similarly with the decrease of PPFD. This assumption is supported by experimental results (Flexas et al., 2008; Douthe et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2015). Estimating gm from species-specific gsc/gm ratio is supported by the robust relationship between gsc and gm observed in different species under manipulated CO2, irradiance, and drought stress (Flexas et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2021; Gong et al., 2022). Although the gsc/gm ratio estimated here could have a certain level of uncertainty due to methodological issues associated with gm estimation (Pons et al., 2009; Gu and Sun, 2014; Gong et al., 2015), RL Kok-Cc was not very sensitive to gsc/gm. Importantly, the factor that directly influences RL Kok-Cc estimation is the decreasing rate of γ with the increase of Iinc (dγ/dIinc) but not absolute values of gm or Cc. Varying gsc/gm by ±0.4 or assuming a constant gm has little effect on dγ/dIinc and a negative dγ/dIinc was evident in all cases (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). In effect, our sensitivity tests show that varying gsc/gm by ±0.4 has a minor influence on both RL estimates and the CO2 effect (Supplemental Figure 3). However, RL/RDk is sensitive to small variations in RL and thus is affected by gsc/gm (Supplemental Figure 4). Adjusting gsc/gm (±0.4 units) leads to changes of mean light inhibition from 4% to 10%. These results highlighted that accounting for dγ/dIinc is essential for estimating RL (Farquhar and Busch, 2017), and the uncertainty associated with the accuracy of dγ/dIinc is much less than assuming a constant γ along a Kok curve. The Kok-Cc-based estimates of RL suppression could be further improved if a new method is developed to precisely estimate gm at very low light. Taken as a whole, neither the Kok nor Kok-Phi method seems suitable to quantify the inhibition of respiration by light (as also suggested by Yin et al., 2020 and Tcherkez et al., 2017a, 2017b), and the inhibition of RL at the operating PPFDs of this study should be lower than 10%.

Conclusions and perspectives

This study showed that elevated growth [CO2] reduced RL and RDk likely as a result of decreasing leaf N status and chlorophyll content. We found no significant long-term CO2 effect on RL/RDk, indicating a concurrent response of RL and RDk to elevated growth [CO2], mediated by the adjustment of nitrogen metabolism in leaves. These results shed light into the incorporation of RL into the carbon cycling models. We revisited the theoretical basis of the Kok method, revised Kok methods and discussed their respective limitations. Using the Kok and Kok-Phi methods, we found that RL were stimulated by short-term CO2 enrichment, while the effect was not supported by the data of the Kok-Cc method. We attributed this short-term CO2 effect to methodological uncertainty associated with unaccounted changes in γ (or Γ*/Cc) along a Kok curve. Accounting for those effects, we found that the Kok and Kok-Phi methods underestimate RL and overestimate the inhibition of respiration under low irradiance conditions of the Kok method, and the inhibition of RL is only 6 ± 4%, which represents 26% of the Kok effect (i.e. of the apparent inhibition of RL found using the classical Kok method). Although the Kok-Cc method has less theoretical uncertainty and is thus in principle more reliable, we are aware that all three methods have operating PPFD much lower than usual, ambient irradiance encountered by plants. However, estimated RL could vary with irradiance. Earlier studies have showed a decrease of RL with the increase of operating PPFD (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Atkin et al., 1998; Atkin et al., 2000) by using the Laisk method which also has the uncertainty associated with the unaccounted changes in Cc (Farquhar and Busch, 2017). To date, the effect of irradiance on RL is poorly known and this should be addressed in subsequent studies.

Materials and methods

Theory

When estimating RL with the Kok method, A should be measured at low irradiance, where A is limited by the light-dependent electron transport rate. According to the equation of the electron transport-limited photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980), A at low light is described as:

| (1) |

where J is the electron transport rate that is used for CO2 fixation and photorespiration, Γ* is the Cc-based CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration (37.4 μmol mol−1 at 25°C (Silva-Perez et al., 2017)). According to the theoretical evaluations of Yin et al. (2011, 2020), Equation 1 forms the theoretical basis of the Kok method, and is useful for evaluating methodological uncertainties.

In this equation, J can be replaced by faetΦ2ρ2αIinc, where faet is the fraction of electron transport for photosynthesis, ρ2 is the fraction of absorbed irradiance partitioned to PSII, α is the absorptance by leaf photosynthetic pigments, and Iinc is incident irradiance (Yin et al., 2011). Here, we define the term as γ, so that Equation 1 becomes:

| (2) |

With the Kok method, net CO2 assimilation rates are plotted against Iinc and datapoints that fall above the breakpoint are used to extrapolate A up the y-axis and thereby estimate RL. In fact, if the term γfaetΦ2ρ2α is assumed to be constant, thus the intercept of this linear relation provides the estimate of RL Kok. In terms of equation, this can be written as:

| (3) |

However, it has been shown that Φ2 could decrease with increasing Iinc even within the range of low irradiance (Genty and Harbinson, 1996; Yin et al., 2020). Alternatively, Φ2 can be obtained from chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. Yin et al. (2009) thus suggested to plot A against Φ2Iinc as:

| (4) |

The Yin et al. (2011) method can be considered as a revised Kok method with variation in Φ2 accounted for, and thus, it is renamed as the “Kok-Phi” method here to highlight the modification. This method assumes that γ is constant across the Kok curve, which is obviously not true under photorespiratory conditions, i.e. under ambient conditions where O2 mole fraction is about 21% (Yin et al., 2014). Theoretically, the Kok-Phi method is applicable for measuring C3 leaves at nonphotorespiratory conditions or C4 leaves (Yin et al., 2011, 2020; Fang et al., 2022).

On the basis of these two methods, we propose a revised Kok method, named “Kok-Cc” method, accounting for variations in γ caused by the decrease in Cc along the Kok curve. In the Kok-Cc method, A should be plotted against γΦ2Iinc, the intercept of the linear relation yields the estimation of RL (RL Kok-Cc):

| (5) |

This method requires estimates of Cc at each step of the A–Iinc curve (see below the section dedicated to Cc estimation). It is worth noting that in practice all “Kok type” methods, assume that RL is not sensitive to changes in Cc along the Kok curve, as they rely on linear extrapolations. To our knowledge, this assumption has not been verified (see Introduction).

Plant material and growth conditions

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants were grown from seed in plastic pots with garden soil and thinned to one plant per pot. Initial nutrient composition of the garden soil (Scotts Miracle-Gro, USA) was 0.68% N, 0.27% P2O5, and 0.36% K2O. Plants were randomly placed in two growth chambers, where CO2 mole fraction was 410 ppm (ambient) and 820 ppm (elevated [CO2]), respectively. In both chambers, air temperature was maintained at 25°C and the relative humidity of the air was 70% for both light and dark periods. The photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) was 700 μmol m−2 s−1 for 16-h photoperiod. All plants were watered every 2–3 days to prevent water stress. This experiment had six replicates per treatment, and in total, 24 plants were used for measurements.

Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

Photosynthetic gas exchange and ChF parameters were measured when there were four fully expanded leaves in each plant (sunflower) or tiller (wheat). Using a portable gas exchange system (LI-6800; Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA), measurements were undertaken on the second youngest fully developed leaves. Light response curves and ChF parameters were measured to estimate RL. When stable gas exchange rates were achieved, we measured A starting at 120 μmol m−2 s−1, and the PPFD was sequentially reduced to 100, 80, 60, 40, 20, and 0 (i.e. with light source switched off) μmol m−2 s−1. ChF measurements were done at PPFD of 120, 100, 80, 60, and 40 μmol m−2 s−1 using the multi-phase flash method. Φ2 was calculated as

| (6) |

where Fs is the steady-state fluorescence in the light conditions and Fm′ is the maximal fluorescence during short saturating pulses of light. For each leaf, the irradiance response of photosynthesis rates was determined at two atmospheric [CO2] (410 and 820 ppm) to assess short-term CO2 response of RL.

All gas exchange parameters have been corrected for the leak effect (i.e. CO2 diffusion across gaskets of leaf chamber) using the measured leak coefficients of intact leaves (Gong et al., 2015; Gong et al., 2018). RDk measured at 410 and 820 ppm [CO2] was used to calculate the cuvette leak coefficient for CO2 (KCO2) with the leaf present in the leaf chamber using the equations in Gong et al. (2015). KCO2 was not significantly different between species and growth [CO2], with a mean KCO2 of 0.21 for wheat and 0.30 for sunflower (Supplemental Figure 5). Thereafter, the response of A to [CO2] (i.e. A–Ci curve) was determined under an irradiance of 700 μmol m−2 s−1 and varying CO2, using a [CO2] sequence of 410, 200, 150, 100, 50, 410, 800, and 1600 μmol mol−1. ChF parameters were acquired at 200, 410, 800, and 1600 μmol mol−1 CO2. Leaf temperature was maintained at 25°C for all gas exchange measurements, there is thus no temperature correction needed to compare RL and RDk.

Estimation of day respiration and Cc

For the Kok method, the data of the linear range of the A: Iinc curve at PPFD levels above the Kok breakpoint (kink) were used to estimate RL according to Equation 3. Each A: Iinc curve was visually inspected to identify the irradiance at the Kok breakpoint, which was 40 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Figure 6). The data measured at PPFD of 120 μmol m−2 s−1 deviated from the linear relation (i.e. the linear domain of assimilation response curve to light between 40 and 100 µmol m−2 s−1), thus they were excluded from the dataset used for the estimation of RL via all methods. Linear regressions were performed using data of the PPFD levels of 40, 60, 80, and 100 µmol m−2 s−1 for all three methods, with the exception of 5 out of 45 curves in which a point that deviated from the linear relation was excluded for the estimation of RL. For the Kok-Phi method, the data from the same PPFD range were used to estimate RL by plotting A against Φ2Iinc according to Equation 4. We have not intensively measured A at very low PPFD levels to accurately identify the breakpoint. However, the data at 40 µmol m−2 s−1 PPFD seem to be above the Kok breakpoint and in the linear domain of A: Iinc curves. Our approach is similar to recent studies which compared the Kok and the Kok-Phi methods (Yin et al., 2011; Fang et al., 2022).

Estimating RL from the Kok-Cc method requires estimates of mesophyll conductance (gm). According to the variable J method of Harley et al. (1992), gm could be calculated as:

| (7) |

Here, we used RL estimated using the Kok-Phi method to calculate gm, given that this method addresses the issue of decreasing Φ2 and provides a more reliable estimation of RL, compared with the Kok method (Yin et al., 2011). Furthermore, using RL Kok or RL Kok-Phi has minor influence on gsc/gm, thus should have no influence on our conclusions (see the discussion on the uncertainty associated with gsc/gm). We chose data in a reliable range of dCc/dA between 10 and 50 for estimating gm as suggested by Harley et al. (1992). dCc/dA was calculated as:

| (8) |

Most of the data obtained with sunflower met this empirical criterion of dCc/dA, while dCc/dA of wheat exceeded this range (dCc/dA > 100) in most cases. Therefore, the A–Ci curve-fitting method was used to estimate the gm value of each leaf in wheat. Based on the FvCB photosynthesis model (Farquhar et al., 1980), the A–Ci curve-fitting tool developed by Sharkey et al. (2007) was used to estimate gm by minimizing the sum of squared deviations between the observed and modeled data.

Recently, it has been found that gm and stomatal conductance to CO2 (gsc) are strongly related (Flexas et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2021). A nearly fixed gsc/gm ratio across different environments and plant functional groups was shown by Ma et al. (2021), offering a useful solution to estimate gm. We first obtained species- and treatment-specific gsc/gm using Equation 7 (sunflower) or curve-fitting (wheat), and then gm along the Kok curve was estimated from measured gsc and previously estimated gsc/gm. Cc was calculated from gm as:

| (9) |

With Cc, γ could be calculated and thus RL Kok-Cc could be estimated by plotting A against γΦ2Iinc using data of the PPFD range of 40–100 µmol m−2 s−1 according to Equation 5. We also tested the sensitivity of RL Kok-Cc to gsc/gm by adjusting obtained species- and treatment-specific gsc/gm (± 0.4).

The daily carbon-use efficiency of leaves, the ratio of net carbon gain to assimilated carbon (integrated photosynthesis) was calculated as:

| (10) |

Since plants were grown in controlled environments, the daily carbon fluxes were calculated as ∫A = A × light hours, ∫RL Kok-Cc = RL Kok-Cc × light hours, and ∫RDk = RDk × dark hours.

Plant sampling and leaf trait parameters

After gas exchange and ChF measurements, the measured leaves were harvested. We measured leaf area and fresh weight, and the chlorophyll content (Chl) was determined by a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502 Plus; Konica Minolta Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The chlorophyll content was calculated from the observed SPAD values as Chl = (99 SPAD)/(144 − SPAD) (Cerovic et al., 2012). All leaves were dried at 70°C to constant mass after drying to stop enzymatic activity at 105°C for 1 h. We measured dry mass of individual leaves, and then, the leaves were ground with a ball mill (Tissuelyser-24, Jingxin Ltd., Shanghai, China). Leaf N content was measured using an elemental analyzer (VARIO ELIII, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (v. 25.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Leaf traits and photosynthetic parameters were analyzed with two-way ANOVAs to determine the influence of growth [CO2], species, and their interaction. Besides, ANOVAs were carried out to clarify the effect of growth [CO2], measurement [CO2], their interaction and species on RL and RL/RDk. A P-value lower than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Φ2) and γ (the lumped parameter in Equation 2) in response to the incident irradiance (Iinc).

Supplemental Figure S2. Sensitivity tests on chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc) and γ (the lumped parameter in Equation 2) in response to the incident irradiance (Iinc).

Supplemental Figure S3. Sensitivity test on respiration in the light estimated by the Kok-Cc method (RL Kok-Cc) of growth CO2 treatments (aCO2 and eCO2) and measurement conditions (410 and 820 ppm).

Supplemental Figure S4. Sensitivity test on ratio of respiration in the light to respiration in the dark (RL Kok-Cc/RDk) of growth CO2 treatments (aCO2 and eCO2) and measurement conditions (410 and 820 ppm).

Supplemental Figure S5. Effects of growth CO2 treatments (aCO2 and eCO2) on the cuvette leak coefficient for CO2 (KCO2) of intact leaves of wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus).

Supplemental Figure S6. Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) in response to the incident irradiance (Iinc) for wheat (T. aestivum) and sunflower (H. annuus).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Yan Ran Sun, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Wei Ting Ma, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Yi Ning Xu, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Xuming Wang, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Lei Li, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Guillaume Tcherkez, Research School of Biology, ANU College of Science, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia; Institut de Recherche en Horticulture et Semences, INRAe, Université d’Angers, 42 rue Georges Morel, 49070 Beaucouzé, France.

Xiao Ying Gong, Key Laboratory for Humid Subtropical Eco-Geographical Processes of the Ministry of Education, School of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350007, China.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 31870377, 32120103005).

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included in the published article and its Supplementary Information.

References

- Ainsworth EA, Long SP (2005) What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol 165(2): 351–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Rogers A (2007) The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ 30(3): 258–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS (2000) The McCree-de Wit-Penning de Vries-Thornley respiration paradigms: 30 years later. Ann Bot 86(1): 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Bahar NHA, Bloomfield KJ, Griffin KL, Heskel MA, Huntingford C, de la Torre AM, Turnbull MH (2017) Leaf respiration in terrestrial biosphere models. InPlant Respiration: Metabolic Fluxes and Carbon Balance. Springer, Cham, pp. 107–142 [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Evans JR, Ball MC, Lambers H, Pons TL (2000) Leaf respiration of snow gum in the light and dark. Interactions between temperature and irradiance. Plant Physiol 122(3): 915–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Evans JR, Siebke K (1998) Relationship between the inhibition of leaf respiration by light and enhancement of leaf dark respiration following light treatment. Funct Plant Biol 25(4): 437–443 [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Scheurwater I, Pons TL (2007) Respiration as a percentage of daily photosynthesis in whole plants is homeostatic at moderate, but not high, growth temperatures. New Phytol 174(2): 367–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub G, Smith RA, Tissue DT, Atkin OK (2011) Impacts of drought on leaf respiration in darkness and light in Eucalyptus saligna exposed to industrial-age atmospheric CO2 and growth temperature. New Phytol 190(4): 1003–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub G, Zaragoza-Castells J, Griffin KL, Atkin OK (2014) Leaf respiration in darkness and in the light under pre-industrial, current and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Plant Sci 226: 120–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Burger M, Asensio JSR, Cousins AB (2010) Carbon dioxide enrichment inhibits nitrate assimilation in wheat and Arabidopsis. Science 328(5980): 899–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Burger M, Kimball BA, Pinter PJ (2014) Nitrate assimilation is inhibited by elevated CO2 in field-grown wheat. Nat Clim Change 4(6): 477–480 [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD (1985) Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta 165(3): 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Vice H, Adams MA (2017) The Kok effect in Vicia faba cannot be explained solely by changes in chloroplastic CO2 concentration. New Phytol 216(4): 1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch FA, Sage RF, Farquhar GD (2018) Plants increase CO2 uptake by assimilating nitrogen via the photorespiratory pathway. Nat Plants 4(1): 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerovic ZG, Masdoumier G, Ghozlen NB, Latouche G (2012) A new optical leaf-clip meter for simultaneous non-destructive assessment of leaf chlorophyll and epidermal flavonoids. Physiol Plant 146(3): 251–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer W, Bondeau A, Woodward FI, Prentice IC, Betts RA, Brovkin V, Cox PM, Fisher V, Foley JA, Friend AD, (2001) Global response of terrestrial ecosystem structure and function to CO2 and climate change: results from six dynamic global vegetation models. Global Change Biol 7(4): 357–373 [Google Scholar]

- Crous KY, Wallin G, Atkin OK, Uddling J, Af Ekenstam A (2017) Acclimation of light and dark respiration to experimental and seasonal warming are mediated by changes in leaf nitrogen in Eucalyptus globulus. Tree Physiol 37(8): 1069–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous KY, Zaragoza-Castells J, Ellsworth DS, Duursma RA, Low M, Tissue DT, Atkin OK (2012) Light inhibition of leaf respiration in field-grown Eucalyptus saligna in whole-tree chambers under elevated atmospheric CO2 and summer drought. Plant Cell Environ 35(5): 966–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthe C, Dreyer E, Epron D, Warren CR (2011) Mesophyll conductance to CO2, assessed from online TDL-AS records of 13CO2 discrimination, displays small but significant short-term responses to CO2 and irradiance in Eucalyptus seedlings. J Exp Bot 62(15): 5335–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Gonzàlez-Meler MA PLS (1997) More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2? Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48(1): 609–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenge ME, Duarte AG, Way DA (2019) Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol 221(1): 32–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Yin X, van der Putten PEL, Martre P, Struik PC (2022) Drought exerts a greater influence than growth temperature on the temperature response of leaf day respiration in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Cell Environ 45(7): 2062–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Busch FA (2017) Changes in the chloroplastic CO2 concentration explain much of the observed Kok effect: a model. New Phytol 214(2): 570–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149(1): 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Rutting T, Pleijel H, Wallin G, Reich PB, Kammann CI, Newton PC, Kobayashi K, Luo Y, Uddling J (2015) Constraints to nitrogen acquisition of terrestrial plants under elevated CO2. Global Change Biol 21(8): 3152–3168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barbour MM, Brendel O, Cabrera HM, Carriqui M, Diaz-Espejo A, Douthe C, Dreyer E, Ferrio JP, Gago J, (2012) Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci 193–194: 70–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbo M, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmes J, Medrano H (2008) Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant Cell Environ 31(5): 602–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier PPG, Saenz N, Griffin KL, Way D, Tcherkez G (2020) Is the Kok effect a respiratory phenomenon? Metabolic insight using 13C labeling in Helianthus annuus leaves. New Phytol 228(4): 1243–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Harbinson J (1996) Regulation of light utilization for photosynthetic electron transport. InPhotosynthesis and the Environment, pp 67–99 [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RM (2003) Plant respiration in productivity models: conceptualisation, representation and issues for global terrestrial carbon-cycle research. Funct Plant Biol 30(2): 171–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Ma WT, Yu YZ, Fang K, Yang Y, Tcherkez G, Adams MA (2022) Overestimated gains in water-use efficiency by global forests. Global Change Biol 28(16): 4923–4934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Schaufele R, Feneis W, Schnyder H (2015) 13CO2/12CO2 exchange fluxes in a clamp-on leaf cuvette: disentangling artefacts and flux components. Plant Cell Environ 38(11): 2417–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Schaufele R, Lehmeier CA, Tcherkez G, Schnyder H (2017) Atmospheric CO2 mole fraction affects stand-scale carbon use efficiency of sunflower by stimulating respiration in light. Plant Cell Environ 40(3): 401–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Tcherkez G, Wenig J, Schaufele R, Schnyder H (2018) Determination of leaf respiration in the light: comparison between an isotopic disequilibrium method and the Laisk method. New Phytol 218(4): 1371–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Anderson OR, Gastrich MD, Lewis JD, Lin GH, Schuster W, Seemann JR, Tissue DT, Turnbull MH, Whitehead D (2001) Plant growth in elevated CO2 alters mitochondrial number and chloroplast fine structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(5): 2473–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Turnbull MH (2013) Light saturated RuBP oxygenation by Rubisco is a robust predictor of light inhibition of respiration in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Biol 15(4): 769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu LH, Sun Y (2014) Artefactual responses of mesophyll conductance to CO2 and irradiance estimated with the variable J and online isotope discrimination methods. Plant Cell Environ 37(5): 1231–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Marco GD, Sharkey TD (1992) Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol 98(4): 1429–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan TF, Migliavacca M, Papale D, Baldocchi D, Reichstein M, Torn M, Wutzler T (2019) Widespread inhibition of daytime ecosystem respiration. Nat Ecol Evol 3: 407–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B (1949) On the interrelation of respiration and photosynthesis in green plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 3: 625–631 [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A (1977) Kinetics of Photosynthesis and Photorespiration in C3 Plants. Nauka, Moscow, Russia [Google Scholar]

- Leakey AD, Ainsworth EA, Bernacchi CJ, Rogers A, Long SP, Ort DR (2009) Elevated CO2 effects on plant carbon, nitrogen, and water relations: six important lessons from FACE. J Exp Bot 60(10): 2859–2876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Ort DR (2004) Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants FACE the future. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55(1): 591–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WT, Tcherkez G, Wang XM, Schaufele R, Schnyder H, Yang Y, Gong XY (2021) Accounting for mesophyll conductance substantially improves 13C-based estimates of intrinsic water-use efficiency. New Phytol 229(3): 1326–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JM, Lobell DB (2013) Reduction of transpiration and altered nutrient allocation contribute to nutrient decline of crops grown in elevated CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ 36(3): 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norby RG, DeLuciac EH, Gielend B, Calfapietrae C, Giardinaf CP, Kingg JS, Ledforda J, McCarthyh HR, Moorei DJP, Ceulemansd R (2005) Forest response to elevated CO2 is conserved across a broad range of productivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(50): 18052–18056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli P, Loreto F (2003) 12CO2 emission from different metabolic pathways measured in illuminated and darkened C3 and C4 leaves at low, atmospheric and elevated CO2 concentration. J Exp Bot 54(388): 1761–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL, Flexas J, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Genty B, Ribas-Carbo M, Brugnoli E (2009) Estimating mesophyll conductance to CO2: methodology, potential errors, and recommendations. J Exp Bot 60(8): 2217–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB, Tjoelker MG, Pregitzer KS, Wright IJ, Oleksyn J, Machado JL (2008) Scaling of respiration to nitrogen in leaves, stems and roots of higher land plants. Ecol Lett 11(8): 793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Allen DJ, Davey PA, Morgan PB, Ainsworth EA, Bernacchi CJ, Cornic G, Dermody O, Dohleman FG, Heaton EA, (2004) Leaf photosynthesis and carbohydrate dynamics of soybeans grown throughout their life-cycle under free-air carbon dioxide enrichment. Plant Cell Environ 27(4): 449–458 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JB, Griffin KL, Lewis JD, Tissue DT (2004) Response of Xanthium strumarium leaf respiration in the light to elevated CO2 concentration, nitrogen availability and temperature. New Phytol 162(2): 377–386 [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Bernacchi CJ, Farquhar GD, Singsaas EL (2007) Fitting photosynthetic carbon dioxide response curves for C3 leaves. Plant Cell Environ 30(9): 1035–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RE, Matthews MA, Boyer JS (1984) Kok effect and the quantum yield of photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 75(1): 95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Perez V, Furbank RT, Condon AG, Evans JR (2017) Biochemical model of C3 photosynthesis applied to wheat at different temperatures. Plant Cell Environ 40(8): 1552–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub DR, Wang X (2008) Why are nitrogen concentrations in plant tissues lower under elevated CO2? A critical examination of the hypotheses. J Int Plant Biol 50(11): 1365–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Bligny R, Gout E, Mahé A, Hodges M, Cornic G (2008) Respiratory metabolism of illuminated leaves depends on CO2 and O2 conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(2): 797–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Gauthier P, Buckley TN, Busch FA, Barbour MM, Bruhn D, Heskel MA, Gong XY, Crous KY, Griffin KL, (2017a) Tracking the origins of the Kok effect, 70 years after its discovery. New Phytol 214(2): 506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Gauthier P, Buckley TN, Busch FA, Barbour MM, Bruhn D, Heskel MA, Gong XY, Crous KY, Griffin KL, (2017b) Leaf day respiration: low CO2 flux but high significance for metabolism and carbon balance. New Phytol 216(4): 986–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Mahe A, Guerard F, Boex-Fontvieille ER, Gout E, Lamothe M, Barbour MM, Bligny R (2012) Short-term effects of CO2 and O2 on citrate metabolism in illuminated leaves. Plant Cell Environ 35(12): 2208–2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AP, De Kauwe MG, Bastos A, Belmecheri S, Georgiou K, Keeling RF, McMahon SM, Medlyn BE, Moore DJP, Norby RJ, (2021) Integrating the evidence for a terrestrial carbon sink caused by increasing atmospheric CO2. New Phytol 229(5): 2413–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Lewis JD, Tissue DT, Seemann JR, Griffin KL (2001) Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on leaf dark respiration of Xanthium strumarium in light and in darkness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(5): 2479–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way DA, Aspinwall MJ, Drake JE, Crous KY, Campany CE, Ghannoum O, Tissue DT, Tjoelker MG (2019) Responses of respiration in the light to warming in field-grown trees: a comparison of the thermal sensitivity of the Kok and Laisk methods. New Phytol 222(1): 132–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr R, Munger JW, McManus JB, Nelson DD, Zahniser MS, Davidson EA, Wofsy SC, Saleska SR (2016) Seasonality of temperate forest photosynthesis and daytime respiration. Nature 534(7609): 680–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ, Love JC, Runck C (1997) Energetic costs of tissue construction in yellow-poplar and white oak trees exposed to long-term CO2 enrichment. Ann Bot 80(3): 289–297 [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Liu X, Liu L, Douthe C, Li Y, Peng S, Huang J (2015) Rapid responses of mesophyll conductance to changes of CO2 concentration, temperature and irradiance are affected by N supplements in rice. Plant Cell Environ 38(12): 2541–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Belay DW, van der Putten PE, Struik PC (2014) Accounting for the decrease of photosystem photochemical efficiency with increasing irradiance to estimate quantum yield of leaf photosynthesis. Photos Res 122(3): 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Niu Y, van der Putten PEL, Struik PC (2020) The Kok effect revisited. New Phytol 227(6): 1764–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Struik PC, Romero P, Harbinson J, Evers JB, Van Der Putten PEL, Vos J (2009) Using combined measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate parameters of a biochemical C3 photosynthesis model: a critical appraisal and a new integrated approach applied to leaves in a wheat (Triticum aestivum) canopy. Plant Cell Environ 32(5): 448–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Sun Z, Struik PC, Gu J (2011) Evaluating a new method to estimate the rate of leaf respiration in the light by analysis of combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. J Exp Bot 62(10): 3489–3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included in the published article and its Supplementary Information.