Highlights

-

•

HDAC inhibitors suppress MYB activity.

-

•

HDAC inhibitor LAQ824 induces MYB degradation in AML cells.

-

•

LAQ824 disturbs the cooperation of MYB and p300.

-

•

LAQ824 induces cell death and differentiation of AML cells.

-

•

Activated MYB counteracts effects of LAQ824 in HL60 cells.

Keywords: MYB, Inhibitor, Myeloid leukemia, LAQ824, HDAC inhibitor, p300

Abstract

A large body of work has shown that MYB acts as a master transcription regulator in hematopoietic cells and has pinpointed MYB as a potential drug target for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Here, we have examined the MYB-inhibitory potential of the HDAC inhibitor LAQ824, which was identified in a screen for novel MYB inhibitors. We show that nanomolar concentrations of LAQ824 and the related HDAC inhibitors vorinostat and panobinostat interfere with MYB function in two ways, by inducing its degradation and inhibiting its activity. Reporter assays show that the inhibition of MYB activity by LAQ824 involves the MYB transactivation domain and the cooperation of MYB with co-activator p300, a key MYB interaction partner and driver of MYB activity. In AML cells, LAQ824-induced degradation of MYB is accompanied by expression of myeloid differentiation markers and apoptotic and necrotic cell death. The ability of LAQ824 to inhibit MYB activity is supported by the observation that down-regulation of direct MYB target genes MYC and GFI1 occurs without apparent decrease of MYB expression already after 2 h of treatment with LAQ824. Furthermore, ectopic expression of an activated version of MYB In HL60 cells counteracts the induction of myeloid differentiation by LAQ824. Overall, our data identify LAQ824 and related HDAC inhibitors as potent MYB-inhibitory agents that exert dual effects on MYB expression and activity in AML cells.

1. Introduction

Transcription factor MYB has recently drawn attention as a promising drug target for malignant neoplasms that are dependent on rearranged MYB or deregulated MYB expression, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC). AML is a common type of leukemia with a poor prognosis, especially for elderly patients [1]. In AML cells, MYB plays a central role as a master regulator of the oncogenic transcriptional program essential for leukemic maintenance and self-renewal, resulting in addiction of the leukemic cells to high levels of MYB expression [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Besides AML, MYB has been implicated in the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), either by duplication or translocation or by mutations that create MYB-responsive super-enhancers upstream of other genes, such as TAL1 or LMO2, and their consequent deregulation [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. ACC is a rare but aggressive cancer that often arises in the salivary glands and is generally incurable in its advanced stage due to the lack of effective systemic therapies [13,14]. In ACC, MYB is involved in recurrent translocations resulting in MYB-NFIB gene fusions that are key oncogenic drivers in a large percentage of cases [15], [16], [17]. The translocations apparently direct MYB-dependent super-enhancers towards the MYB gene, leading to a positive feedback loop causing high expression of MYB fusion proteins in the tumor cells [18].

MYB is crucial for the development and homeostasis of the hematopoietic system and shows high expression in immature hematopoietic progenitor cells, where it acts as a DNA-binding protein involved in transcriptional regulation of specific target genes [3,19]. As a transcription factor, MYB is highly dependent on interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300, which is mediated by a conserved LXXLL-motif present in the MYB transactivation domain and the KIX-domain of p300 [20]. Mutations within the LXXLL-motif disturb the interaction with p300 and weaken the activity of MYB, establishing the importance of the MYB-p300 interaction for MYB function [21], [22], [23].

In recent years, MYB has gained attention as a potential drug target [24,25]. The finding that AML cells depend on higher levels of MYB than normal hematopoietic progenitors has fostered interest in MYB as a pharmacological target, because it predicts the leukemic cells to be more vulnerable to MYB inhibition than normal hematopoietic progenitors [2,4,5]. Recent pioneering studies have confirmed MYB targeting by low-molecular weight compounds that disrupt the MYB/p300 interaction and showed that MYB is a druggable transcription factor [26], [27], [28], [29]. These studies have also shown that blocking MYB activity is effective against AML in an in vivo mouse model. Likewise, proliferation of ACC cells in vitro and in mouse models inhibition of MYB was decreased when MYB was inhibited [16,30,31]. Overall, these studies suggested that pharmacological inhibition of MYB may have potential as a novel strategy against MYB-dependent malignancies.

We have recently screened a chemical library consisting of approved drugs and related compounds for novel MYB inhibitors [31], [32], [33]. One of the compounds found to inhibit MYB activity was the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor LAQ824 (also known as dacinostat). This was a surprising finding because HDAC activity itself is usually associated with transcriptional repression, suggesting that HDAC inhibition would be expected to have an opposite effect. Here, we present an initial analysis of the MYB-inhibitory activity of LAQ824.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells

HEK293T, HepG2 and U2OS are non-hematopoietic adherent human cell lines. NB4, HL60, U937 and THP1 are human myeloid leukemia cell lines. All cell lines were originally obtained from ATCC and were free of mycoplasma contamination. HL60 cells expressing ectopic C-terminally truncated MYB (MYB-CT3) were generated by lentiviral infection as described before [32]. Control HL60 cells were transfected with an “empty” lentivirus. AML cells were grown in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. Adherent human cell lines were grown in DMEM plus 10% FCS. Cell viability was determined by MTT assays. Cells were incubated with compounds for 48 h, followed by addition of MTT solution (Millipore Corp., USA), incubation for 4 h, and measuring the absorbance at 495 nm with a microplate photometer (MPP 4008, Mikrotek).

2.2. Library screening

The HEK-MYB-Luc and HEK-Luc reporter cell lines have been described [32]. The library screen of the Selleck FDA-approved Drug Library (SelleckChem) and the LOPAC-1280 library (Sigma-Aldrich), covering together more than 4000 FDA-approved drugs and compounds with annotated activities, has been described before [33]. Individual compounds were obtained from SelleckChem or Sigma-Aldrich and stored as 10 mM DMSO stock solutions at −70 °C.

2.3. Expression vectors

Expression vectors for MYB, MYB-2KR, MYB-CT3, Gal4-CT3 and p300 have been described [27,34,35]. The MYB- and Gal4-inducible luciferase reporter plasmids pGL4–5xMRE(GG)-Myc (containing 5 tandem copies of a Myb binding site upstream of a core promoter) and pG5E4–38Luc (containing 5 copies of the Gal4 binding site upstream of the minimal adenovirus E4 promoter have been described [36,37].

2.4. Transfections

Transfection of HEK293T cells by calcium-phosphate co-precipitation and reporter assays were performed as previously described [38].

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR

RT-PCR of MYC, GFI1, and β-actin mRNA expression was performed as described before [31]. All experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates and the following primers:

MYC: 5′-GCCGATCAGCTGGAGATGA-3′ and 5′-GTCGTCAGGATCGCAGATGAAG-3′;

GFI1: 5′-GCTCGGAGTTTGAGGACTTC-3′ and 5′-ATGGGCACATTGACTTCTCC-3′;

ACTB: 5′-AGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGAC-3′ and 5′-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3′

2.6. Flow cytometry

Approximately 106 cells were cultured for 2 days in RPMI 1640 medium containing the desired concentration of LAQ824. Control cells were incubated without compound. The cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry for CD11b and CD14 expression by using PE/Cy7-labeled anti-human CD11b (ICRF44, BioLegend) and FITC-labeled anti-human CD14 antibodies (63D3, BioLegend) and a FC 500 Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Apoptotic and necrotic cells were determined by double-staining with FITC-annexin-V (BioLegend) and propidium iodide (PI). CXP software (Beckman Coulter) was used for subsequent analysis.

2.7. Western blot analysis

Protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, using the following antibodies: anti-Myb (5E11, [39]), anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, AC-15), anti-Gal4 (SantaCruz Biotechnology, RK5C1), anti-p300 (Millipore, RW128), anti-HA (BioLegend, 16B12), anti-acetyl-Lysine (CellSignaling, Ac-K-103) and anti-H3K27ac (Abcam, ab4729).

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments subjected to statistical analysis were performed at least three times with independent replicates in each experiment. Data were shown as mean with standard deviation, which reflects the variation within each group. Statistical differences between groups were calculated by the two-tailed Student's t-test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of HDAC inhibitors as potent MYB-inhibitory agents

We have previously established the MYB reporter cell line HEK-MYB-Luc that features doxycycline-inducible expression of the activated human MYB mutant MYB-2KR and a stably integrated MYB-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid, and used it to screen compound libraries for MYB-inhibitory compounds [32]. MYB-2KR lacks two sites for SUMO-modification that endows it with a higher transactivation potential than wild-type MYB [34,36]. We have also used the HEK-Luc companion cell line that expresses firefly luciferase from a constitutive promoter to allow exclusion of toxic compounds and unspecific luciferase inhibitors. Screening of the Selleck-library of approved drugs identified LAQ824 (also known as Dacinostat), a potent Pan-HDAC inhibitor, as a potential MYB inhibitor. Details of the screening have been described previously [33]. Fig. 1A illustrates schematically the HEK-Luc and HEK-MYB-Luc cells and shows the chemical structure of LAQ824. Luciferase assays (Fig. 1B) demonstrated that LAQ824 significantly increased the luciferase activity in HEK-Luc cells whereas luciferase activity first slightly increased but then strongly decreased in HEK-MYB-Luc cells. Because the reporter constructs were stably integrated into the cellular genome the increased expression caused by the HDAC inhibitor might be due to increased histone acetylation and a more open chromatin structure. In HEK-MYB-Luc cells, this increase was counteracted by increased concentrations of LAQ824, presumably due decreased MYB activity. This confirmed the results of the initial screening and suggested LAQ824 to be a candidate MYB-inhibitory agent. Western blotting showed that MYB expression was increased by the compound in HEK-MYB-Luc cells, indicating that decreased reporter activity in these cells was not caused by loss of MYB expression.

Fig. 1.

Identification of LAQ824 as a MYB-inhibitory compound. A. Schematic illustration of the stable reporter cell lines HEK-Luc and HEK-MYB-Luc. HEK-Luc cells harbor a constitutively active luciferase expression vector. HEK-MYB-Luc cells carry an artificial MYB-dependent luciferase reporter gene and a doxycycline-inducible expression system for human MYB-2KR. B. Luciferase activity of HEK-LUC and HEK-MYB-Luc cells treated for 16 h with increasing concentrations of LAQ824. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (ns: non-specific; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student's t-test). MYB expression in HEK-MYB-Luc cells is shown in the bottom panel. C. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the MYB-responsive reporter gene pGL4–5xMRE(GG)-Myc without (yellow columns) or together with expression vectors for wt MYB (red columns) or MYB-2KR (blue columns) and treated for 16 h with LAQ824. Bars show the average luciferase activity of the cells normalized to untreated cells. The panels on the right show the expression of wt-MYB, MYB-2KR and β-actin under the different conditions. Each column in the reporter experiments shows the average value of 4 biological replicates from a representative experiment. All reporter experiments were repeated at least three times and showed similar results. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Since HEK-MYB-Luc cells express the MYB-2KR mutant we next compared the ability of LAQ824 to inhibit the activity of MYB-2KR and wild-type MYB. We transfected HEK293T cells transiently with the MYB-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid and expression vectors for wild-type MYB or MYB-2KR. As an additional control, we transfected only the reporter plasmid. Fig. 1C shows that the luciferase activity was not inhibited by LAQ824 in the absence of MYB (yellow columns) whereas the compound strongly decreased luciferase activity in the presence of wt-MYB and MYB-2KR (red and blue columns), confirming its inhibitory potential also for wild-type MYB. We noted that there was a significant decrease of MYB activity already at very low concentrations of LAQ824 in Fig. 1C, which was not seen when stably transfected cells (Fig. 1B) were used. We suspect that differences in the chromatin organization of the reporter gene between transiently and stably transfected cells might be responsible for this difference. As shown by Western blotting, the expression of wt-MYB and MYB-2KR was slightly increased by the compound, again demonstrating that the compound interferes with MYB activity rather than with its expression.

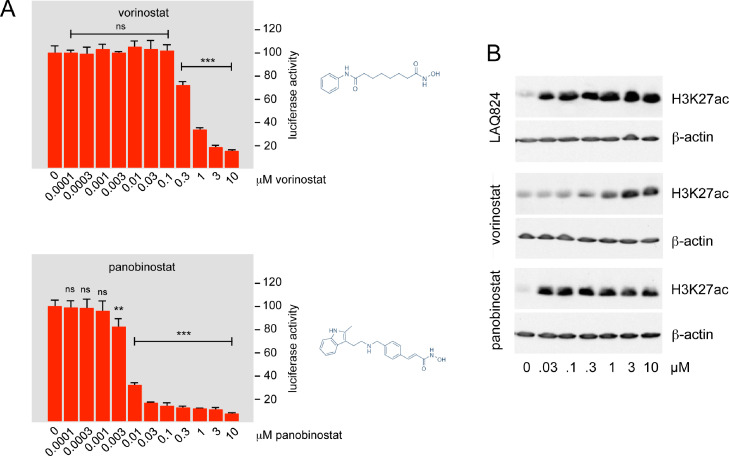

To investigate if other Pan-HDAC inhibitors share the MYB-inhibitory activity with LAQ824, we tested the effects of the related compounds vorinostat and panobinostat, also known as SAHA and LBH589, respectively. Both compounds decreased MYB activity, although in different concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). To investigate if the different activities of the compounds against MYB were related to their activities as HDAC inhibitors we compared the HDAC-inhibitory activity of LAQ824, vorinostat and panobinostat, using the histone H3K27 acetylation as a read-out (Fig. 2B). As expected, all three compounds increased H3K27 acetylation, however vorinostat was clearly less active than the other compounds. This suggested that the MYB-inhibitory activity of the compounds is related to their activity as HDAC-inhibitors. Overall, our data identified several Pan-HDAC inhibitors as MYB-inhibitory agents, that act at nanomolar concentrations.

Fig. 2.

MYB-inhibitory activity of vorinostat and panobinostat. A. The columns in each panel show the relative luciferase activity in HEK293T cells transfected with reporter plasmid pGL4–5xMRE(GG)-Myc and expression vector for MYB-2KR, treated for 16 h with the indicated concentrations of the HDAC inhibitors vorinostat and panobinostat. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (ns: non-specific; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student's t-test). The chemical structure of both inhibitors is shown on the right. Each column shows the average value of 4 biological replicates from a representative experiment. All reporter experiments were repeated tree times and showed similar results. B. HEK293T cells were treated for 16 h with the indicated concentrations of LAQ824, vorinostat and panobinostat. Total cell extracts were then analyzed with antibodies against acetylated H3K27 and β-actin.

3.2. LAQ824 induces expression of the myeloid differentiation markers and cell death and suppresses MYB target gene expression in AML cells

To examine the activity of LAQ824 in a setting relevant to the oncogenic potential of MYB we investigated its effect on human AML cell lines. We first compared the effect of LAQ824 on the viability of several hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cell lines. As shown in Fig. 3, the MYB-expressing hematopoietic cell lines were more sensitive to the compound than the non-hematopoietic cell lines that do not express MYB. The strong effect on the leukemic cells is consistent with the MYB inhibitory activity of the compound and in agreement with previous studies demonstrating anti-leukemia effects of LAQ824 in vitro and in vivo [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45].

Fig. 3.

LAQ824 suppresses viability of AML cell lines. Non-hematopoietic cell lines (HEKT, U2OS and HepG2) and MYB-expressing AML cell lines (U937, HL60, THP1, and NB4) were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of LAQ824 and analyzed by a MTT assay. The figure shows percent viable cells relative to untreated cells. Error bars are derived from three independent biological replicate experiments.

Western blotting showed that LAQ824 inhibits MYB protein expression in a concentration-dependent manner in the leukemia cell lines (Fig. 4A). As MYB is essential for the maintenance of AML cells and for preventing their differentiation, inhibition of MYB expression is expected to trigger differentiation and/or cell death. Treatment of NB4, HL60, THP1 and U937 cells with LAQ824 showed that NB4 and THP1 cells responded strongly with induction of apoptotic and necrotic cell death, as determined by annexin V and propidium iodide staining, while HL60 and U937 cells were less sensitive (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, analysis of the myeloid differentiation markers CD11b and CD14 showed increased expression upon LAQ824 treatment in all cell lines, indicating that the compound also triggered differentiation (Fig. 4C). We employed the proteasome inhibitor MG132 to investigate the mechanism responsible for the decreased MYB expression. As exemplified for HL60 cells in Fig. 4D, the down-regulation of MYB by LAQ824 was clearly diminished in the presence of MG132, indicating that LAG824 induced down-regulation of MYB expression via proteasomal degradation. Previous work had shown that one of the activities of HDAC inhibitors is the increased acetylation of HSP90, leading to proteasomal degradation of certain HSP90 client proteins [40,[46], [47], [48], [49]]. To see if the degradation of MYB is related to the HDAC-inhibitory activity of LAQ824 we compared the effects of LAG824, vorinostat and panobinostat on MYB expression in HL60 cells. While panobinostat was slightly more potent than LAQ824 in inhibiting MYB protein expression, vorinostat had no effect in the concentration range examined (Fig. 4E). Since the HDAC-inhibitory activity of vorinostat was lower than that of the other compounds, it appeared likely that the induced degradation MYB is a consequence of the HDAC inhibitory activity of the compounds, possibly due to their effect on HSP90.

Fig. 4.

Effects of LAQ824 on AML cell lines. A. Human AML cell lines NB4, HL60, THP1 and U937 were incubated for 48 h with LAQ824 at the indicated concentrations, followed by Western blot analysis of MYB and β-actin expression. B,C. The cells treated with LAQ824 as in panel A were then stained with annexin V and propidium iodide (B) or with antibodies against CD11b and CD14 (C) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Bars show the percentage of positive cells. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences to untreated cells (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student's t-test). Unmarked columns indicate no significant difference to untreated cells. Data in B and C are derived from at least three biological replicates. D. HL60 cells treated for 24 h with LAQ824 in the presence or absence of 5 μM proteasome inhibitor MG132 expression were analyzed by Western blotting for MYB and β-actin expression. E. HL60 cells were treated for 16 h with the indicated concentrations of LAQ824, vorinostat and panobinostat. Total cell extracts were then analyzed with antibodies against MYB, acetylated H3K27, total H3 and β-actin.

While these data suggested that the loss of MYB expression in the presence of Pan-HDAC inhibitors contributed to the biological effects seen in AML cells, close inspection of the data in Fig. 4 revealed that several of the AML cells showed already significant induction of cell death and expression of differentiation-associated gene although MYB was still expressed at normal expression levels. This indicated that these effects were not simply caused by the loss of MYB expression but raised the question of whether disruption of the MYB-transactivation potential by LAQ824 that was clearly demonstrated by the experiments in Fig. 1, also played a role? To address this question we employed HL60 cells that were engineered by lentiviral infection to express the C-terminally truncated MYB-CT3. As shown before [50], C-terminal truncation generates a version of MYB that is more active than the full-length protein. Thus, by ectopic expression of MYB-CT3 we have supplied these cells with a higher level of MYB activity. Consequently, we would expect the compound to have a less strong effect on the cells. As seen in Fig. 5A, the induction of CD11b expression by LAQ824 was significantly decreased in MYB-CT3 expressing HL60 cells compared to HL60-control cells. Western blotting illustrated at the bottom of Fig. 5A showed that MYB expression was not affected at the low concentrations of LAQ824 used. This experiment therefore supported the notion that the effect of the compound was caused to a significant extent by interfering with the activity of MYB and that increased MYB activity in the MYB-CT3 expressing cells dampened the effect of the compound.

Fig. 5.

LAQ824 affects HL60 cells in a MYB-dependent manner. A. HL60 cells infected with a control lentiviral vector (HL60-control) or a lentiviral vector for C-terminally truncated MYB-CT3 (HL60-MYB-CT3) were treated for 96 h with LAQ824. The cells were then stained with antibodies against CD11b and CD14 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Bars show the percentage of positive cells. The bottom panel shows Western blot analyses for MYB and β-actin expression in the treated cells. B. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of MYC and GFI1 mRNA expression in HL60 cells treated for 2 or 4 h with LAQ824. The Western blot at the bottom shows the expression of MYB and β-actin in the treated cells. Asterisks in A and B indicate statistically significant differences to untreated cells (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student's t-test). Unmarked columns indicate no significant difference to untreated cells. In A, each column shows the average of three biological replicates. In B, data are derived from three biological replicates with three technical replicate measurements for each biological experiment.

In an additional experiment we examined the expression of MYB target genes after a short-term treatment with LAQ824, i.e. under conditions where LAQ824 induced MYB degradation was negligible. We treated HL60 cells for 2 or 4 h with LAQ824, followed by RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of the MYB target genes MYC and GFI1. Both genes are directly regulated by MYB, which binds to their transcriptional control regions [51,52]. Fig. 5B shows that LAQ824 down-regulated the expression of both genes already after a 2 h treatment with the compound. Importantly, western blotting revealed that MYB expression was not decreased during this short treatment time. That we observed down-regulation of these direct MYB target genes after 2 h makes it also unlikely that their decreased expression is an indirect effect of the induction of differentiation, which usually is induced on a longer time scale. This experiment therefore supported the notion that LAQ824 also suppresses the MYB transactivation potential in AML cells, in addition to inducing MYB degradation after prolonged time and at higher compound concentrations.

3.3. LAQ824 affects the function of the MYB transactivation domain

To gain insight into how LAQ824 inhibits MYB activity we first examined its effect on the activity of the C-terminally truncated MYB-CT3 which lacks regulatory sequences, including ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation sites, which have been implicated in modulating MYB activity and expression [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]. Fig. 6A shows that the activity of MYB-CT3 was suppressed by LAQ824, however, the concentration-dependence of the inhibition differed from that of wt-MYB or MYB-2KR shown in Fig. 1C. In particular, the significant inhibitory activity at concentrations below 10 nM was not observed in case of MYB-CT3. This difference could be due to the higher activity of MYB-CT3 [50] or its higher expression (due to lack of ubiquitination sites), which may make MYB-CT3 generally more resistant to inhibition. On the other hand, this difference may suggest a specific role of the C-terminal MYB sequences in rendering wt-MYB and MYB-2KR more sensitive to the inhibitory activity of LAQ824. Next, we examined the inhibitory effect of the compound on the activity of a fusion protein containing only the MYB transactivation domain (TAD) and the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. As shown in Fig. 6B, inhibition of the activity of the fusion protein by LAQ824 showed a similar concentration-dependence as MYB-CT3, indicating that the inhibitory potential of the compound is also directed towards the MYB transactivation domain. Thus, two different domains of MYB appear to be involved in the inhibition by LAQ824.

Fig. 6.

LAQ824-mediated suppression of MYB activity involves the MYB transactivation domain. A. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the MYB-responsive reporter gene pGL4–5xMRE(GG)-Myc and expression vector for MYB-CT3. Bars show the normalized luciferase activity in LAQ824-treated cells. The bottom panel shows the expression of MYB-CT3. B. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the Gal4-responsive reporter gene pG5E4–38luc and expression vector for a Gal4 fusion protein with the MYB transactivation domain. Cells were analyzed as in A. Western blotting shows the expression of Gal4-MYB-CT3. C. HEK293T cells were transfected with the MYB-responsive reporter gene pGL4–5xMRE(GG)-Myc and expression vectors for wt-MYB (top) or wt-MYB and p300 (bottom). Cells were treated for 16 h with LAQ824, as indicated, and analyzed for luciferase activity. An overlay of the luciferase activities in the absence or presence of p300 is shown in the right panel. Asterisks in panels A-C indicate statistical significance (ns: non-specific; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student's t-test). Each column shows the average value of 4 biological replicates from a representative experiment. All reporter experiments were repeated at least three times to validate the results. D. Un-transfected HEK293T cells were treated for 16 h with the indicated concentrations of LAQ824, followed by Western blot analysis of total cell extracts for expression of endogenous p300 and β-actin. E. HEK293T cells transfected with expression vectors for MYB-2KR and p300 were treated for 16 h with LAQ824, as indicated at the bottom. Total cell extracts were then analyzed by Western blotting for expression of p300, MYB-2KR, acetylated p300, acetylated MYB-2KR and β-actin.

The co-activator p300/CBP is a key interaction partner and driver of the activity of the MYB TAD [60]. We therefore examined whether LAQ824 interferes with the stimulation of the MYB transactivation potential by p300. As show in Fig. 6C, co-expression of MYB and p300 resulted in a significantly increased MYB activity, which was inhibited by LAQ824 in a concentration-dependent manner. Interestingly, the concentration-dependence of the inhibition by LAQ824 was very similar irrespectively of whether p300 was co-expressed or not. This is shown by the overlay of both inhibitory concentration profiles in the right panel of Fig. 6C, after normalizing the activity in the absence of LAQ824 to 100% in both cases. This indicated that the compound interferes with the stimulation of MYB activity by ectopically expressed p300 in similar manner as by endogenous p300, either by decreasing the expression of p300 or its activity as a co-activator. Further experiments showed that LAQ824 neither decreased endogenous (Fig. 6D) nor exogenous (Fig. 6E) p300 expression. To see if LAQ824 decreases the activity of p300 we focused on its HAT-activity, however. We observed that the auto-acetylation of p300 or the acetylation of MYB was slightly increased by LAQ824, as expected from the HDAC-inhibitory activity of the compound. The fact that acetylation of MYB was dependent on the co-expressed p300 and was not decreased by the compound also argued that LAQ824 did not interfere with the MYB-p300 interaction. Overall, our experiments identified the MYB TAD as a relevant target of the MYB-inhibitory activity of LAQ824 and pointed to a role of p300 in the inhibitory mechanism. Additionally, LAQ824-dependent inhibitory activity appeared also to be mediated by C-terminal MYB-sequences. However, the mechanism by which LAQ824 interferes with the activity of p300 as a co-activator of MYB currently remains to be explored.

4. Discussion

MYB, a master transcription regulator in the hematopoietic system, has recently emerged as a potential therapeutic target against AML. Initial studies aiming to identify MYB inhibitors have demonstrated that MYB is a druggable transcription factor and have suggested that strategies based on MYB inhibition may open therapeutic perspectives for the treatment of AML and ACC [16,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. Here, we have shown that the Pan-HDAC inhibitor LAQ824 is a potent MYB-inhibitory agent that suppresses MYB activity at nanomolar concentration. Since HDACs are often considered as transcriptional repressors, to find that an HDAC-inhibitor suppresses rather than activates MYB activity was a perplexing finding. However, comparison of the activities of the HDAC-inhibitors LAQ824, vorinostat and panobinostat showed that they all inhibit MYB, which suggested that their HDAC-inhibitory activity is primarily responsible for their ability to suppress the transactivation potential of MYB. Notwithstanding this, the effects of LAQ824 and panobinostat were not completely identical. Despite their similar HDAC-inhibitory activities, as judged from the increase of H3K27 acetylation, they differ regarding MYB inhibition at low nanomolar concentrations. This implies an additional inhibitory mechanism that may be specific for LAQ824.

Our studies have found that LAQ824 disturbs MYB function in two ways, namely by suppressing MYB protein expression and by interfering with its transactivation potential. LAQ824-induced down-regulation of MYB expression in AML cells appeared to be due to proteasomal degradation, as shown in case of HL60 cells. As mentioned before, HDAC inhibitors exert pleiotropic effects by changing the acetylation state of multiple protein targets [61]. As an example, HDAC inhibition causes increased acetylation of HSP90, which results in disruption of its chaperone function and degradation of client proteins, as exemplified by BCR-ABL and AML-ETO oncogenic fusion-proteins or the glucocorticoid receptor [40,[46], [47], [48], [49]]. Although a link between HSP90 and MYB has not been established so far, it is possible that proteasomal degradation of MYB by LAQ824 is caused by a similar mechanism.

In addition to inducing degradation of MYB, we found that LAQ824 also suppresses the transactivation potential of MYB. This was clearly shown in HEK293T cells in which degradation of MYB is blocked, presumably due to the expression of the adenoviral E1A protein in these cells. The E1A protein was shown to disrupt the function of FBW7, an adaptor protein that recruits MYB among other target proteins to the SCF-FBW7 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, and thereby prevent its degradation [62,63]. Similar differences of MYB stability between HEK293T and AML cells have been noted before [31], [32], [33] and, as shown here, were instrumental in recognizing that LAQ824 exerts inhibitory effects on the TAD and the C-terminal domain of MYB, thereby suppressing its transactivation potential.

The mechanistic basis of the MYB-inhibitory activity of LAQ824 is not yet fully understood. As HDACs are traditionally considered for their roles in inhibiting transcription, it is difficult to understand why HDAC inhibition has not an opposite, i.e. positive effect on MYB-dependent transcription. Acetylation of MYB itself, which was proposed to stimulate and not to repress MYB-dependent transactivation [54,64], seems unlikely to play a role because MYB-CT3, which lacks all know acetylation sites, is still inhibited by LAQ824 (Fig. 3A). In full-length MYB, acetylation of lysine residues in the C-terminal part has been proposed to stimulate interaction with CBP (the paralog of p300) and to increase the transactivation potential of MYB [64]. Assuming that HDACs can de-acetylate these sites this would predict a stimulatory effect of LAQ824 on MYB activity, which is the opposite of what we have observed. MYB was shown to associate with HDAC1 and HDAC2 via TIP60 [65], but again their effect on MYB activity was negative, suggesting that HDAC inhibition would be expected to stimulate rather than inhibit MYB activity. It is therefore likely that the effects observed with the HDAC inhibitors are caused by indirect mechanisms involving cooperating proteins being expressed at altered steady-state levels or having altered activities.

Our work suggests that the co-activator p300, a key driver of MYB activity, may be involved in such an indirect mechanism. However, similar to effects on the acetylation of MYB itself, it is currently unclear how LAQ824 interferes with the role of p300 as a MYB co-activator. p300 auto-acetylates itself in several lysine-rich conserved regions, however, increased acetylation of p300 as a result of HDAC inhibition was shown to stimulate rather than to decrease its transactivation potential when fused to a DNA-binding domain [66]. Nevertheless, it is possible that the acetylation status of specific sites of p300 might alter its association with interacting proteins and thereby affect the co-activator activity of p300. Such a mechanism has been suggested for the transcription factor HIF-α whose activity is suppressed by HDAC inhibitors. This inhibition was not dependent on direct acetylation of HIF-α, but rather on the acetylation status of p300 [67], [68], [69]. Whether LAQ824 inhibits the function of p300 as a MYB co-activator via similar effects on acetylation-dependent interactions with additional p300 interacting proteins is currently not known. Since p300 plays a role as a co-activator of many transcription factors, acetylation-dependent binding of additional p300-interacting proteins could also provide a mechanism to diversify the effects of HDAC inhibition for different p300-dependent transcription factors.

Interestingly, recent work has suggested another possible explanation for how HDAC inhibitors may be able to suppress p300 activity, which is related to the formation of bio-molecular condensates. These condensates are membrane-less aggregates or compartments formed by liquid-liquid phase separation driven by multivalent interactions between their components, such as proteins and nucleic acids [70,71]. Bio-molecular condensates have been studied intensely for their role in super-enhancer mediated gene expression [72,73] and are frequently formed by proteins that contain intrinsically disordered regions, as found in many transcriptional regulatory proteins. Interestingly, acetylation of such proteins and their disordered regions appears to be one factor that influences their ability to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation [74]. Co-activator p300 contains a large amount of intrinsically unstructured sequences and is known as a component of bio-molecular condensates. Importantly, hyper-acetylation of p300 counteracts its ability to form such condensates [75], raising the possibility that HDAC inhibitors, by causing increased acetylation of p300, can disrupt its ability to participate in condensate formation and thereby modulate its co-activator function of transcription factors recruited into the condensates. Interestingly, chemical genomics studies on rhabdomyosarcomas have shown that HDAC inhibitors disrupt super-enhancer function and the associated gene expression circuits by destabilizing the bio-molecular condensates [76,77]. Essentially, these studies have suggested that HDACs are crucial to provide a balance between p300-dependent acetylation and HDAC-induced de-acetylation that is important for the maintenance of the condensates and that HDAC inhibition disturbs this balance and inhibits their function by disrupting them. These considerations are interesting as they imply a positive role of HDACs in transcriptional regulation. If and how these considerations relate to the suppression of MYB activity by LAQ824 is still a matter of speculation and remains to be explored.

From a therapeutic perspective, the MYB inhibitory activity of LAQ824 accords with several studies that have reported anti-leukemia effects of the compound in vitro and in vivo [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45]. In this regard, it is interesting to note that siRNA-mediated down-regulation of MYB expression has been shown to sensitize the AMLs to the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat in vitro as well as in an in vivo mouse AML model [78]. We have also previously reported synergistic effects of Celastrol, an inhibitor of the MYB-p300 interaction, and panobinostat on the induction of differentiation in HL60 cells [27]. These findings suggest that combining of HDAC inhibition with other MYB-inhibitory approaches could open interesting therapeutic strategies against AML.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our work has identified the hematopoietic master transcription regulator MYB as a unsuspected target of Pan-HDAC inhibitors and showed that nanomolar concentrations of LAQ824 and related inhibitors interfere with MYB function in AML cells in two ways, namely by inducing its degradation and inhibiting its activity. As exemplified for LAQ824, the inhibition of MYB activity involves the MYB transactivation domain and the cooperation with co-activator p300. The biological effects exerted by HDAC inhibition on AML cells are therefore likely to involve partial suppression of MYB function.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maria V. Yusenko: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Karl-Heinz Klempnauer: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung and the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

References

- 1.Short N.J., Rytting M.E., Cortes J.E. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2018;392:593–606. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess J.L., Bittner C.B., Zeisig D.T., Bach C., Fuchs U., Borkhardt A., Frampton J., Slany R.K. Myb is an essential downstream target for homeobox-mediated transformation of hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2006;108:297–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsay R.J., Gonda T.J. Myb function in normal and cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somervaille T.C., Matheny C.J., Spencer G.J., Iwasaki M., Rinn J.L., Witten D.M., Chang H.Y., Shurtleff S.A., Downing J.R., Cleary M.L. Hierarchical maintenance of MLL myeloid leukemia stem cells employs a transcriptional program shared with embryonic rather than adult stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuber J., Rappaport A.R., Luo W., Wang E., Chen C., Vaseva A.V., Shi J., Weissmueller S., Fellmann C., Taylor M.J., Weissenboeck M., Graeber T.G., Kogan S.C., Vakoc C.R., Lowe S.W. An integrated approach to dissecting oncogene addiction implicates a Myb-coordinated self-renewal program as essential for leukemia maintenance. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1628–1640. doi: 10.1101/gad.17269211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takao S., Forbes L., Uni M., Cheng S., Pineda J.M.B., Tarumoto Y., Cifani P., Minuesa G., Chen C., Kharas M.G., Bradley R.K., Vakoc C.R., Koche R.P., Kentsis A. Convergent organization of aberrant MYB complex controls oncogenic gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Elife. 2021;10:e65905. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemma R.B., Ledsaak M., Fuglerud B.M., Sandve G.K., Eskeland R., Gabrielsen O.S. Chromatin occupancy and target genes of the haematopoietic master transcription factor MYB. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:9008. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88516-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahortiga I., De Keersmaecker K., Van Vlierberghe P., Graux C., Cauwelier B., Lambert F., Mentens N., Beverloo H.B., Pieters R., Speleman F., Odero M.D., Bauters M., Froyen G., Marynen P., Vandenberghe P., Wlodarska I., Meijerink J.P., Cools J. Duplication of the MYB oncogene in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:593–595. doi: 10.1038/ng2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clappier E., Cuccuini W., Kalota A., Crinquette A., Cayuela J.M., Dik W.A., Langerak A.W., Montpellier B., Nadel B., Walrafen P., Delattre O., Aurias A., Leblanc T., Dombret H., Gewirtz A.M., Baruchel A., Sigaux F., Soulier J. The C-MYB locus is involved in chromosomal translocation and genomic duplications in human T-cell acute leukemia (T-ALL), the translocation defining a new T-ALL subtype in very young children. Blood. 2007;110:1251–1261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Neil J., Tchinda J., Gutierrez A., Moreau L., Maser R.S., Wong K.K., Li W., McKenna K., Liu X.S., Feng B., Neuberg D., Silverman L., DeAngelo D.J., Kutok J.L., Rothstein R., DePinho R.A., Chin L., Lee C., Look A.T. Alu elements mediate MYB gene tandem duplication in human T-ALL. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:3059–3066. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansour M.R., Abraham B.J., Anders L., Berezovskaya A., Gutierrez A., Durbin A.D., Etchin J., Lawton L., Sallan S.E., Silverman L.B., Loh M.L., Hunger S.P., Sanda T., Young R.A. A.T. Look. Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science. 2014;346:1373–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1259037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahman S., Magnussen M., León T.E., Farah N., Li Z., Abraham B.J., Alapi K.Z., Mitchell R.J., Naughton T., Fielding A.K., Pizzey A., Bustraan S., Allen C., Popa T., Pike-Overzet K., Garcia-Perez L., Gale R.E., Linch D.C., Staal F.J.T., Young R.A., Look A.T., Mansour M.R. Activation of the LMO2 oncogene through a somatically acquired neomorphic promoter in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:3221–3226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenman G., Andersson M.K., Andrén Y. New tricks from an old oncogene: gene fusion and copy number alterations of MYB in human cancer. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2986–2995. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.15.12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon P.M., Chakraborty S., Moskaluk C.A., Joshi P.J., Thomas C.Y. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: a review of recent advances, molecular targets, and clinical trials. Head Neck. 2016;38:620–627. doi: 10.1002/hed.23925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson M., Andrén Y., Mark J., Horlings H.M., Persson F., Stenman G. Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and neck. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18740–18744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909114106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson M.K., Afshari M.K., Andrén Y., Wick M.J., Stenman G. Targeting the Oncogenic Transcriptional Regulator MYB in Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma by Inhibition of IGF1R/AKT Signaling. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017;109:9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson M.K., Mangiapane G., Nevado P.T., Tsakaneli A., Carlsson T., Corda G., Nieddu V., Abrahamian C., Chayka O., Rai L., Wick M., Kedaigle A., Stenman G., Sala A. ATR is a MYB regulated gene and potential therapeutic target in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oncogenesis. 2020;9:5. doi: 10.1038/s41389-020-0194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drier Y., Cotton M.J., Williamson K.E., Gillespie S.M., Ryan R.J., Kluk M.J., Carey C.D., Rodig S.J., Sholl L.M., Afrogheh A.H., Faquin W.C., Queimado L., Qi J., Wick M.J., El-Naggar A.K., Bradner J.E., Moskaluk C.A., Aster J.C., Knoechel B., Bernstein B.E. An oncogenic MYB feedback loop drives alternate cell fates in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:265–272. doi: 10.1038/ng.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L., Glazov E.A., Pattabiraman D.R., Al-Owaidi F., Zhang P., Brown M.A., Leo P.J., Gonda T.J. Integrated genome-wide chromatin occupancy and expression analyses identify key myeloid pro-differentiation transcription factors repressed by Myb. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4664–4679. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zor T., De Guzman R.N., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of c-Myb. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;337:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasper L.H., Boussouar F., Ney P.A., Jackson C.W., Rehg J., van Deursen J.M., Brindle P.K. A transcription-factor-binding surface of coactivator p300 is required for haematopoiesis. Nature. 2002;419:738–743. doi: 10.1038/nature01062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg M.L., Sutton S.E., Pletcher M.T., Wiltshire T., Tarantino L.M., Hogenesch J.B., Cooke M.P. c-Myb and p300 regulate hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pattabiraman D.R., McGirr C., Shakhbazov K., Barbier V., Krishnan K., Mukhopadhyay P., Hawthorne P., Trezise A., Ding J., Grimmond S.M., Papathanasiou P., Alexander W.S., Perkins A.C., Levesque J.P., Winkler I.G., Gonda T.J. Interaction of c-Myb with p300 is required for the induction of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by human AML oncogenes. Blood. 2014;123:2682–2690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-413187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pattabiraman D.R., Gonda T.J. Role and potential for therapeutic targeting of MYB in leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;272:69–77. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uttarkar S., Frampton J., Klempnauer K.-.H. Targeting the transcription factor Myb by small-molecule inhibitors. Exp. Hematol. 2017;47:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uttarkar S., Dukare S., Bopp B., Goblirsch M., Jose J., Klempnauer K.-.H. Naphthol AS-E phosphate inhibits the activity of the transcription factor Myb by blocking the interaction with the KIX domain of the coactivator p300. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1276–1285. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uttarkar S., Dassé E., Coulibaly A., Steinmann S., Jakobs A., Schomburg C., Trentmann A., Jose J., Schlenke P., Berdel W.E., Schmidt T.J., Müller-Tidow C., Frampton J., Klempnauer K.-.H. Targeting acute myeloid leukemia with a small molecule inhibitor of the Myb/p300 interaction. Blood. 2016;127:1173–1182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-668632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uttarkar S., Piontek T., Dukare S., Schomburg C., Schlenke P., Berdel W.E., Müller-Tidow C., Schmidt T.J., Klempnauer K.-.H. Small-molecule disruption of the Myb/p300 cooperation targets acute myeloid leukemia cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2905–2915. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramaswamy K., Forbes L., Minuesa G., Gindin T., Brown F., Kharas M.G., Krivtsov A.V., Armstrong S.A., Still E., de Stanchina E., Knoechel B., Koche R., Kentsis A. Peptidomimetic blockade of MYB in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:110. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02618-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y., Gao R., Cao C., Forbes L., Li J., Freeberg S., Fredenburg K.M., Justice J.M., Silver N.L., Wu L., Varma S., West R., Licht J.D., Zajac-Kaye M., Kentsis A., Kaye F.J. MYB-activated models for testing therapeutic agents in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2019;98:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusenko M.V., Trentmann A., Andersson M.K., Abdel Ghani L., Jakobs A., Arteaga Paz M.F., Mikesch J.H., von Kries P.J., Stenman G., Klempnauer K.-.H. Monensin, a novel potent MYB inhibitor, suppresses proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia and adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2020;479:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yusenko M., Jakobs A., Klempnauer K.-.H. A novel cell-based screening assay for small-molecule MYB inhibitors identifies podophyllotoxins teniposide and etoposide as inhibitors of MYB activity. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13159. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31620-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yusenko M.V., Biyanee A., Andersson M.K., Radetzki S., von Kries J.P., Stenman G., Klempnauer K.-.H. Proteasome inhibitors suppress MYB oncogenic activity in a p300-dependent manner. Cancer Lett. 2021;520:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahle Ø., Andersen T.Ø., Nordgård O., Matre V., Del Sal G., Gabrielsen O.S. Transactivation properties of c-Myb are critically dependent on two SUMO-1 acceptor sites that are conjugated in a PIASy enhanced manner. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1338–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckner R., Ewen M.E., Newsome D., Gerdes M., DeCaprio J.A., Lawrence J.B., Livingston D.M. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the adenovirus E1A-associated 300-kD protein (p300) reveals a protein with properties of a transcriptional adaptor. Genes Dev. 1994;8:869–884. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molvaersmyr A.K., Saether T., Gilfillan S., Lorenzo P.I., Kvaløy H., Matre V., Gabrielsen O.S. A SUMO-regulated activation function controls synergy of c-Myb through a repressor-activator switch leading to differential p300 recruitment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4970–4984. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mink S., Haenig B., Klempnauer K.-.H. Interaction and functional collaboration of p300 and C/EBPb. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burk O., Mink S., Ringwald M., Klempnauer K.-H. Synergistic activation of the chicken mim-1 gene by v-myb and C/EBP transcription factors. EMBO J. 1993;12:2027–2038. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sleeman J.P. Xenopus A-myb is expressed during early spermatogenesis. Oncogene. 1993;8:1931–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimmanapalli R., Fuino L., Bali P., Gasparetto M., Glozak M., Tao J., Moscinski L., Smith C., Wu J., Jove R., Atadja P., Bhalla K. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor LAQ824 both lowers expression and promotes proteasomal degradation of Bcr-Abl and induces apoptosis of imatinib mesylate-sensitive or -refractory chronic myelogenous leukemia-blast crisis cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5126–5135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisberg E., Catley L., Kujawa J., Atadja P., Remiszewski S., Fuerst P., Cavazza C., Anderson K., Griffin J.D. Histone deacetylase inhibitor NVP-LAQ824 has significant activity against myeloid leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Leukemia. 2004;18:1951–1963. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiskus W., Pranpat M., Balasis M., Herger B., Rao R., Chinnaiyan A., Atadja P., Bhalla K. Histone deacetylase inhibitors deplete enhancer of zeste 2and associated polycomb repressive complex 2 proteins in human acute leukemia cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:3096–3104. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiskus W., Rao R., Fernandez P., Herger B., Yang Y., Chen J., Kolhe R., Mandawat A., Wang Y., Joshi R., Eaton K., Lee P., Atadja P., Peiper S., Bhalla K. Molecular and biologic characterization and drug sensitivity of pan-histone deacetylase inhibitor–resistant acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 2008;112:2896–2905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz K., Romanski A., Puccetti E., Wietbrauk S., Vogela A., Keller M., Scott J.W., Serve H., Bug G. The deacetylase inhibitor LAQ824 induces notch signalling in haematopoietic progenitor cells. Leukemia Res. 2011;35:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romanski A., Schwarz K., Keller M., Wietbrauk S., Vogel A., Roos J., Oancea C., Brill B., Krämer O.H., Serve H., Ruthardt M., Bug G. Deacetylase inhibitors modulate proliferation and self-renewal properties of leukemic stem andprogenitor cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3219–3226. doi: 10.4161/cc.21565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bali P., Pranpat M., Bradner J., Balasis M., Fiskus W., Guo F., Rocha K., Kumaraswamy S., Boyapalle S., Atadja P., Seto E., Bhalla K. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26729–26734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kovacs J.J., Murphy P.J., Gaillard S., Zhao X., Wu J.T., Nicchitta C.V., Yoshida M., Toft D.O., Pratt W.B., Yao T.P. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang G., Thompson M.A., Brandt S.J., Hiebert S.W. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce the degradation of the t(8;21) fusion oncoprotein. Oncogene. 2007;26:91–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bots M., Verbrugge I., Martin B.P., Salmon J.M., Ghisi M., Baker A., Stanley K., Shortt J., Ossenkoppele G.J., Zuber J., Rappaport A.R., Atadja P., Lowe S.W., Johnstone R.W. Differentiation therapy for the treatment of t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia using histone deacetylase inhibitors. Blood. 2014;123:1341–1352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-488114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Y.L., Ramsay R.G., Kanei-Ishii C., Ishii S., Gonda T.J. Transformation by carboxyl-deleted Myb reflects increased transactivating capacity and disruption of a negative regulatory domain. Oncogene. 1991;6:1549–1553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roe J.-.S., Mercan F., Rivera K., Pappin D.J., Vakoc C.R. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses the function of hematopoietic transcription factors in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:1028–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao L., Ye P., Gonda T.J. The MYB proto-oncogene suppresses monocytic differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells via transcriptional activation of its target gene GFI1. Oncogene. 2014;33:4442–4449. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bies J., Wolff L. Oncogenic activation of c-Myb by carboxyl-terminal truncation leads to decreased proteolysis by the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway. Oncogene. 1997;14:203–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomita A., Towatari M., Tsuzuki S., Hayakawa F., Kosugi H., Tamai K., Miyazaki T., Kinoshita T., Saito H. c-Myb acetylation at the carboxyl-terminal conserved domain by transcriptional co-activator p300. Oncogene. 2000;19:444–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aziz N., Miglarese M.R., Hendrickson R.C., Shabanowitz J., Sturgill T.W., Hunt D.F., Bender T.P. Modulation of c-Myb-induced transcription activation by a phosphorylation site near the negative regulatory domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6429–6433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miglarese M.R., Richardson A.F., Aziz N., Bender T.P. Differential regulation of c-Myb-induced transcription activation by a phosphorylation site in the negative regulatory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22697–22705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pani E., Ferrari S. p38MAPKδ controls c-Myb degradation in response to stress. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2008;40:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pani E., Menigatti M., Schubert S., Hess D., Gerrits B., Klempnauer K.-.H., Ferrari S. Pin1 interacts with c-Myb in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and regulates its transactivation activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bies J., Sramko M., Wolff L. Stress-induced phosphorylation of Thr486 in c-Myb by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases attenuates conjugation of SUMO-2/3. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:36983–36993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.500264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vo N.K., Goodman R.H. CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13505–13508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bolden J.E., Peart M.J., Johnstone R.W. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanei-Ishii C., Nomura T., Takagi T., Watanabe N., Nakayama K.I., Ishii S. Fbxw7 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets c-Myb for nemo-like kinase (NLK)-induced degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30540–30548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804340200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isobe T., Hattori T., Kitagawa K., Uchida C., Kotake Y., Kosugi I., Oda T., Kitagawa M. Adenovirus E1A inhibits SCF(Fbw7) ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:27766–27779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sano Y., Ishii S. Increased Affinity of c-Myb for CREB-binding Protein (CBP) after CBP-induced Acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3674–3682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao H., Jin S., Gewirtz A.M. The histone acetyltransferase TIP60 interacts with c-Myb and inactivates its transcriptional activity in human leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:925–934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stiehl D.P., Fath D.M., Liang D., Jiang Y., Sang N. Histone deacetylase inhibitors synergize p300 autoacetylation that regulates its transactivation activity and complex formation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2256–2264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fath D.M., Kong X., Liang D., Lin Z., Chou A., Jiang Y., Fang J., Caro J., Sang N. Histone deacetylase inhibitors repress the transactivation potential of hypoxia-inducible factors independently of direct acetylation of HIF-α. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13612–13619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600456200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liang D., Kong X., Sang N. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on HIF-1. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2430–2435. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen S., Sang N. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: the epigenetic therapeutics that repress hypoxia-inducible factors. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/197946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Banani S.F., Lee H.O., Hyman A.A., Rosen M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sabari B.R. Biomolecular condensates and gene activation in development and disease. Dev. Cell. 2020;55:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sabari B.R., Dall'Agnese A., Boija A., Klein I.A., Coffey E.L., Shrinivas K., Abraham B.J., Hannett N.M., Zamudio A.V., Manteiga J.C., Li C.H., Guo Y.E., Day D.S., Schuijers J., Vasile E., Malik S., Hnisz D., Lee T.I., Cisse I.I., Roeder R.G., Sharp P.A., Chakraborty A.K., Young R.A. Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science. 2018;361 doi: 10.1126/science.aar3958. eaar3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boija A., Klein I.A., Sabari B.R., Dall'Agnese A., Coffey E.L., Zamudio A.V., Li C.H., Shrinivas K., Manteiga J.C., Hannett N.M., Abraham B.J., Afeyan L.K., Guo Y.E., Rimel J.K., Fant C.B., Schuijers J., Lee T.I., Taatjes D.J., Young R.A. Transcription factors activate genes through the phase-separation capacity of their activation domains. Cell. 2018;175:1842–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saito M., Hess D., Eglinger J., Fritsch A.W., Kreysing M., Weinert B.T., Choudhary C., Matthias P. Acetylation of intrinsically disordered regions regulates phase separation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:51–61. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y., Brown K., Yu Y., Ibrahim Z., Zandian M., Xuan H., Ingersoll S., Lee T., Ebmeier C.C., Liu J., Panne D., Shi X., Ren X., Kutateladze T.G. Nuclear condensates of p300 formed though the structured catalytic core can act as a storage pool of p300 with reduced HAT activity. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4618. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24950-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gryder B.E., Wu L., Woldemichael G.M., Pomella S., Quinn T.R., Park P.M.C., Cleveland A., Stanton B.Z., Song Y., Rota R., Wiest O., Yohe M.E., Shern J.F., Qi J., Khan J. Chemical genomics reveals histone deacetylases are required for core regulatory transcription. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3004. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gryder B.E., Pomella S., Sayers C., Wu X.S., Song Y., Chiarella A.M., Bagchi S., Chou H.C., Sinniah R.S., Walton A., Wen X., Rota R., Hathaway N.A., Zhao K., Chen J., Vakoc C.R., Shern J.F., Stanton B.Z., Khan J. Histone hyperacetylation disrupts core gene regulatory architecture in rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:1714–1722. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0534-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ye P., Zhao L., McGirr C., Gonda T.J. MYB downregulation enhances sensitivity of U937 myeloid leukemia cells to the histone deacetylase inhibitor LBH589 in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2014;343:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]