Abstract

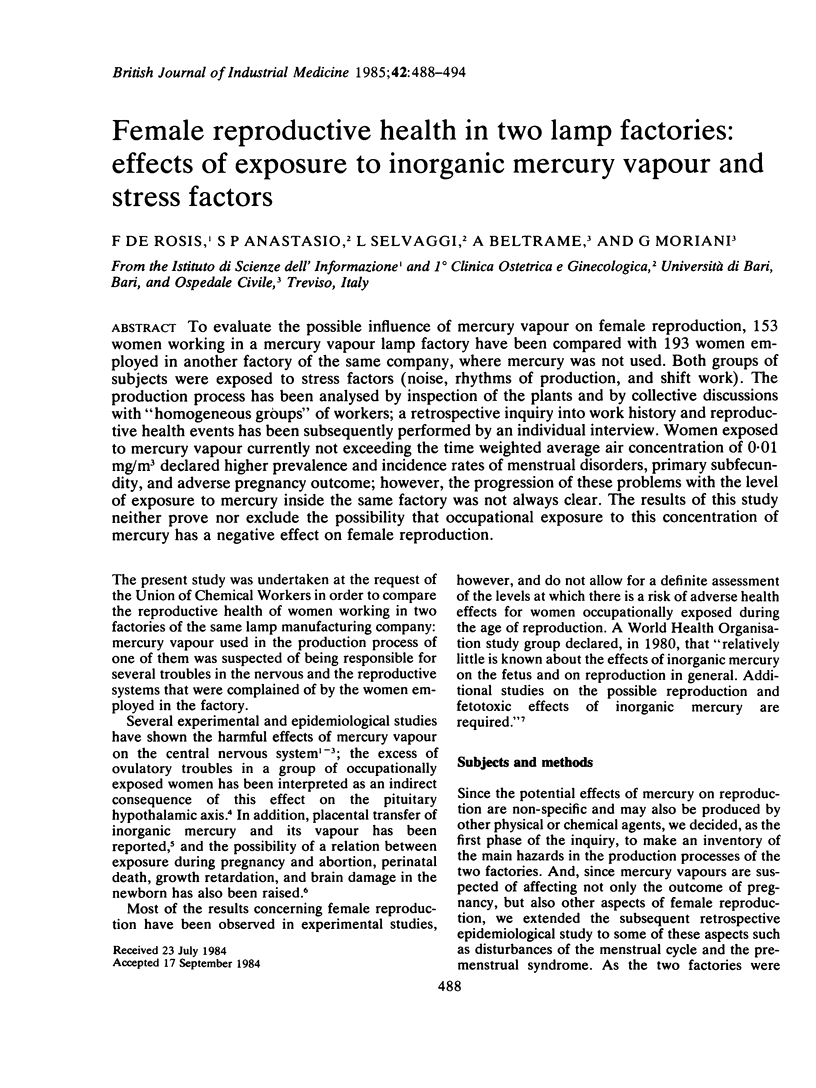

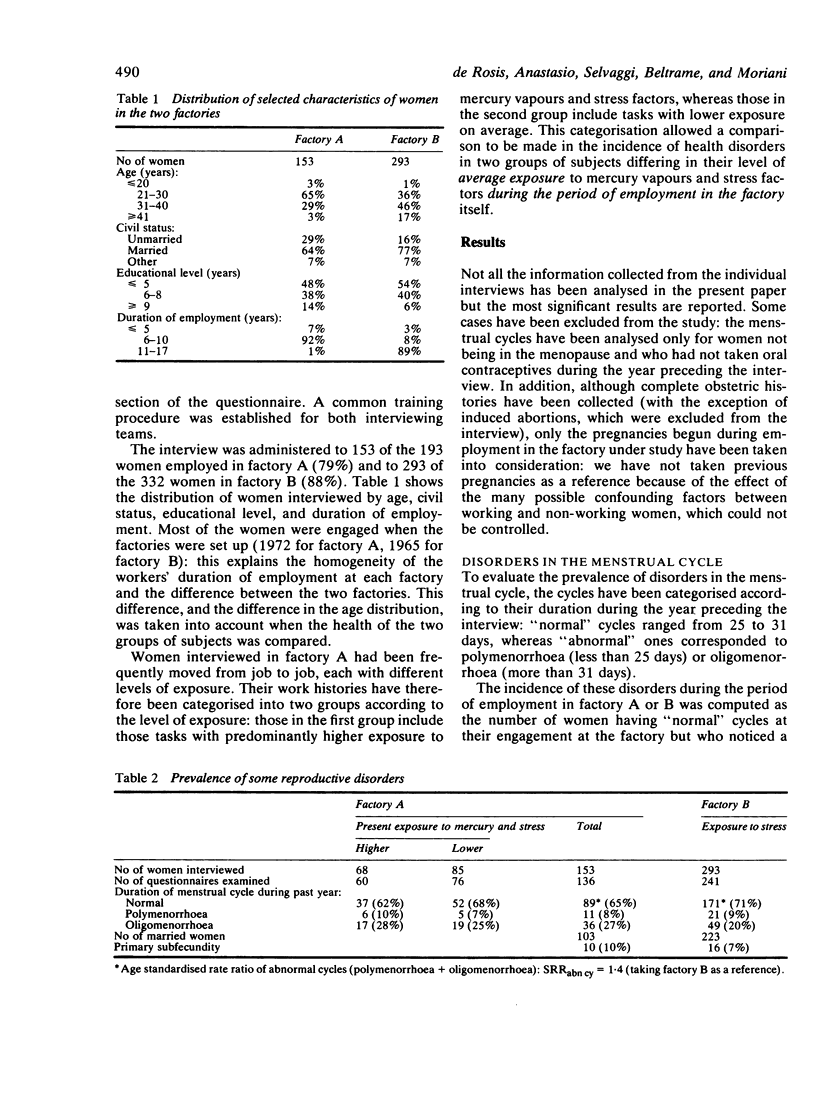

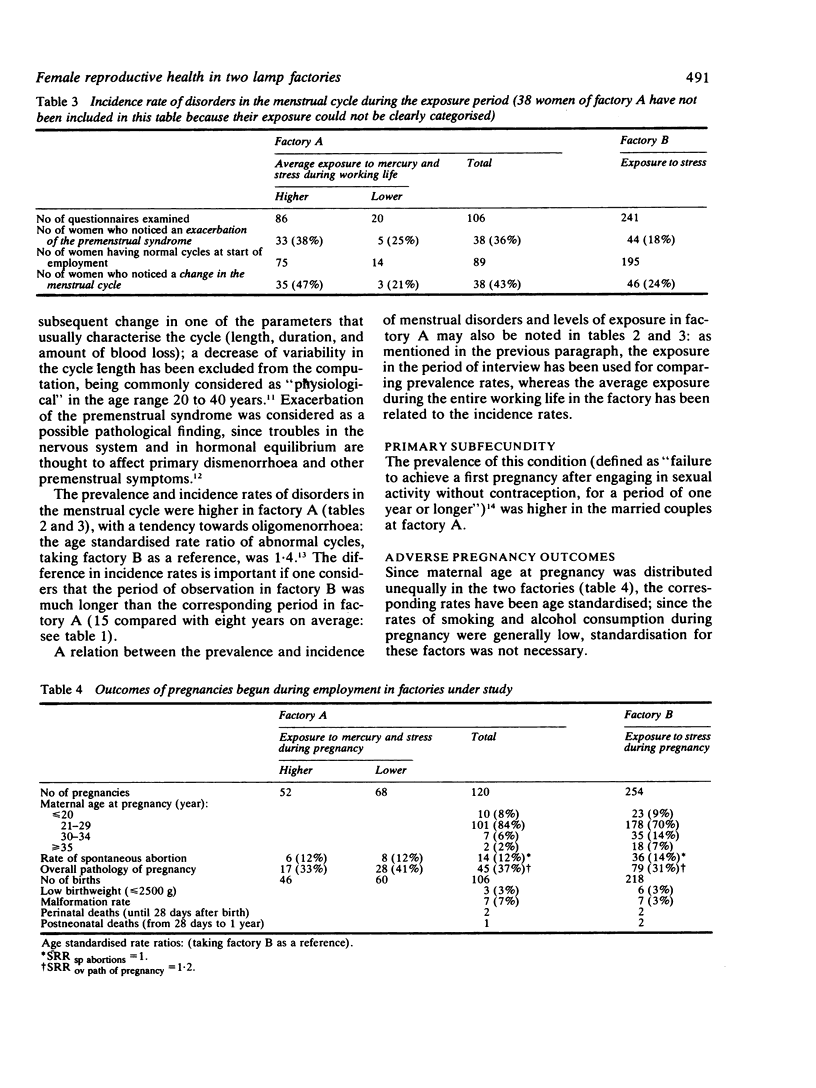

To evaluate the possible influence of mercury vapour on female reproduction, 153 women working in a mercury vapour lamp factory have been compared with 193 women employed in another factory of the same company, where mercury was not used. Both groups of subjects were exposed to stress factors (noise, rhythms of production, and shift work). The production process has been analysed by inspection of the plants and by collective discussions with "homogeneous groups" of workers; a retrospective inquiry into work history and reproductive health events has been subsequently performed by an individual interview. Women exposed to mercury vapour currently not exceeding the time weighted average air concentration of 0.01 mg/m3 declared higher prevalence and incidence rates of menstrual disorders, primary subfecundity, and adverse pregnancy outcome; however, the progression of these problems with the level of exposure to mercury inside the same factory was not always clear. The results of this study neither prove nor exclude the possibility that occupational exposure to this concentration of mercury has a negative effect on female reproduction.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergsjo P., Jenssen H., Vellar O. D. Dysmenorrhea in industrial workers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1975;54(3):255–259. doi: 10.3109/00016347509157772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson T. W., Magos L., Greenwood M. R. The transport of elemental mercury into fetal tissues. Biol Neonate. 1972;21(3):239–244. doi: 10.1159/000240512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson E., Jansa S., Wande H., Källén B., Ostlund E. Pregnancy outcome for women working in laboratories in some of the pharmaceutical industries in Sweden. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1980 Jun;6(2):131–134. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki K., Franssila E., Vainio H. Spontaneous abortions among female chemical workers in Finland. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1980 Feb;45(2):123–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01274131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos B. J., Longo L. D. Mercury toxicity in the pregnant woman, fetus, and newborn infant. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976 Oct 1;126(3):390–409. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyser M. R., Ayalon D., Harell A., Toaff R., Cardova T. Stress induced delay of ovulation. Obstet Gynecol. 1973 Nov;42(5):667–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter E. D., Peled N., Luria M. Mercury exposure and effects at a thermometer factory. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1982;8 (Suppl 1):161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroom F. Q., Greer M. Mercury vapour intoxication. Brain. 1972;95(2):305–318. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]