Abstract

Background

Pelvic floor disorders are common, especially in pregnancy and after delivery, in the postmenopausal period, and old age, and they can significantly impact on the patient’s quality of life.

Methods

This narrative review is based on publications retrieved by a selective search of the literature, with special consideration to original articles and AWMF guidelines.

Results

Pelvic floor physiotherapy (evidence level [EL] 1), the use of pessaries (EL2), and local estrogen therapy can help alleviate stress/urge urinary incontinence and other symptoms of urogenital prolapse. Physiotherapy can reduce urinary incontinence by 62% during pregnancy and by 29% 3–6 months post partum. Anticholinergic and ß-sympathomimetic drugs are indicated for the treatment of an overactive bladder with or without urinary urge incontinence (EL1). For patients with stress urinary incontinence, selective serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors can be prescribed (EL1). The tension-free tape is the current standard of surgical treatment (EL1); in an observational follow-up study, 87.2% of patients were satisfied with the outcome 17 years after surgery. Fascial reconstruction techniques are indicated for the treatment of primary pelvic organ prolapse, and mesh-based surgical procedures for recurrences and severe prolapse (EL1).

Conclusion

Urogynecological symptoms should be specifically asked about by physicians of all relevant specialties; if present, they should be treated conservatively at first. Structured surgical techniques with and without mesh are available for the treatment of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Preventive measures against pelvic floor dysfunction should be offered during pregnancy and post partum.

Urogynecology is the specialty that deals with pelvic floor dysfunction in women. The most common disorders in this area are urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. They are influenced by a genetic predisposition and are usually of multifactorial origin. Pregnancy and delivery, postmenopause, and advanced age markedly affect their incidence.

Urogynecology.

The most common disorders in urogynecology are urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Preventive treatments, such as postpartum pessary therapy to support the recovery of the pelvic floor connective tissue even when the patient has no symptoms, are increasingly investigated in current studies. The primary therapy should always be conservative; pelvic floor exercises and pessary therapy are indicated for the treatment ofboth urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Surgical methods involve either the reconstruction of the patient’s native fascial structures or their replacement. The indications for these procedures are now very clearly defined.

Methods

Preventive treatment approaches.

Pelvic floor protection must be integrated into the management of pregnancy and delivery.

This article is largely based on the current AWMF guidelines, more recent reviews and studies (Table, eTables 1– 3), and clinical evaluations. Postpartum fecal incontinence is not addressed in this paper because of limitations of space.

Table. Some of the recommendations that have been updated in the S3 guideline on pelvic organ prolapse, listed here for illustrative purposes with selected new randomized, controlled trials.

| n | Comparison | Study design | Primary endpoint | Results [95% CI] | Adverse events |

| Study: van Ijsselmuiden et al. (2020) (e31) | |||||

| 126 | laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy vs. vaginal sacrospinal hysteropexy | anatomical apical recurrences | apical recurrences in 1/54 (2%) vs. 2/58 (3%) | the two operations have the same recurrence rates | |

| Study: Lucot et al. (2018) (e32) | |||||

| 262 | laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy vs. transvaginal mesh for cystocele | reoperations | n = 6/129 (5%) vs. n = 14/128 (11%) reoperations for complications 1 (1%) vs. 11 (9%)* |

continence operations: 4/129 (3%) vs. 1/128 (0.8%) de novo dyspareunia: 10/71 (14 %) vs. 18/61 (30 %)* |

sacrocolpopexy and vaginal mesh inserts are both effective; after sacrocolpopexy there is less dyspareunia |

| Study: Lucot et al. (2022) (e33) | |||||

| 209 | laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy vs. transvaginal mesh for cystocele | recurrences and complications. 4-year follow-up | vaginal apex (POPQ C) in mm– 51.7 ± 27.1 vs. – 59.7 ± 1.7 complications 2% [0; 4.7] vs. 8.7% [3.4; 13.7]: H R 4.6 [1.007; 21]* |

de novo/exacerbated dyspareunia 3%, 2/65 vs. 10%, 6/61 | sacrocolpopexy and vaginal mesh inserts are both effective; after sacrocolpopexy there is less dyspareunia |

| Study: Bataller et al. (2019) (e34) | |||||

| 120 | laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy vs. vaginal anterior mesh | apical recurrences anterior recurrences |

57/58 (98%) vs. 55/58 (95%) 34/58 (58%) vs. 32/58 (55%) |

de novo dyspareunia 3 (7%) vs. 7 (19%) | sacrocolpopexy and vaginal mesh inserts are both effective; after sacrocolpopexy there is less dyspareunia |

| Study: Coolen et al. (2017) (e35) | |||||

| 74 | laparoscopic vs. open sacrocolpopexy | PGI(Patient‘s Global Impression) score | 71% (22/31) vs. 74% (20/27) | laparoscopy is just as good as open surgery and is to be preferred | |

| Study: Noe et al. (2015) (e36) | |||||

| 83 | pectopexy with vaginal and laparoscopic fascial reconstruction, vs. sacrocolpopexy | anatomical recurrences | 1/42 (2%) vs. 4/41 (10%) | sacropexy 5 de novo defecation disturbance vs. 0 for pectopexy | pectopexy is a good option for apical prolapse |

| Study: Schulten et al. (2019) (e37) | |||||

| 208 | sacrospinal hysteropexy vs. vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament fixation | anatomical recurrences/symptoms (combined endpoint) follow-up: 60 months | anatomical recurrences: 46/102 (45%) vs. 51/102 (50%) difference: –4.8 [-18.5; 8.9] | stress incontinence:2 vs. 7 | vaginal surgery with and without hysterectomy is equivalent |

| Study: Jelofsek (2018) (e38) | |||||

| 374 | uterosacral ligament fixation vs. sacrospinal fixation 5-year follow-up | feeling of bulging;lowering of the apex by > 1/3 of the upper vagina, reoperation | 68/133 (51%) vs. 80/134 (60%) (combined endpoint) | similar outcomes from both procedures | |

| Study: Ahmed et al. (2020) (e39) | |||||

| 84 | anterior repair with suburethral sling versus anterior 4-arm mesh insertion | stress incontinence and recurrent prolapse | 6/42 (12%) vs. 3/43 (7%) 6/41 vs. 1/43 |

recurrent prolapse:both procedures comparable stress urinary incontinence: possibly anterior repair with suburethral sling | |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; POPQ, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification; *statistically significant, p ≤ 0.05

eTable 1. Current randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses on local estrogenization, pessary therapy, and pelvic floor conditioning.

| n | Comparison | Study design | Primary endpoint | Results [95% confidence interval] | Adverse events |

| Study: Verghese et al. (2020) (e7) | |||||

| 325 | pre- and postoperative administration of local estradiol vs. no application | randomized pilot study | Compliance > 75 % Applikation secondary urinary tract infections symptom questionnaires |

preoperatively 79 % (34/43), 83 % (35/42) 6 weeks postoperatively 8/42 (19 %) vs. 4/42 (10 %)* no differences |

no serious complications related to estrogeni‧zation |

| Study: Chiengthong et al. (2022) (e8) | |||||

| 78 | postmenopausal pessary therapy with estriol 0.03 mg intravaginally + Lactobacillus vs. without | randomized controlled trial (RCT) | bacterial vaginosis normal flora index ICIQ-VS questionnaire |

2/35 (6%) vs. 2/32 (6%) after 14 weeks 8/37 (6%) vs. 5/35 (6%)* 4.5 vs. 7.0 |

vaginal bleeding in a single patient in the control group |

| Study: Lillemon et al. (2022) (e9) | |||||

| 39 | vaginaler Estrogenring vs. Placebo-Vaginalring | RCT | changes in the microbiome and urogenital symptoms | no significant changes in Lactobacilli or the microbiome | unclear |

| Study: Probst et al. (2020) (e10) | |||||

| 130 | continuous pessary therapy for 24 vs. 12 weeks (= standard) | RCT | frequency of occurrence of vaginal epithelial lesions/erosionsnon-inferiority margin 7.5 percentage points | group differences –5.7 percentage points [-7, 4; 4.0] = longer duration of use non-inferior | none |

| Study: Boyd et al. (2021) (e11) | |||||

| 132 | effect of pessary therapy on size of genital hiatus and degree of prolapse | Cohort study | mean change of genital hiatus (GH) and POPQ stage | −0.47 ± 1.02 cm* anterior compartment –0.47 ± 0.76* posterior compartment –0.47 ± 1.02* middle compartment –0.32 ± 1.33* |

not reported |

| Study: Nekkanti et al. (2022) (e12) | |||||

| 50 | urethral pessary vs. disposable continence tampon | RCT | improvement of stress incontinence (Patient Global Impression of Improvement-[PGI]-I) | 80 % (8/10) vs. 75 % (9/12)study underpowered because of low patient recruitment | none |

| Study: Stafne et al. (2022) (e13) | |||||

| 855 | targeted vs. no pelvic floor exercises during pregnancy | RCT | rate of urinary incontinence 7 years postpartum | 78 (51 %) vs. 63 (57 %) | none |

| Study: Luginbuehl (2022) (e14) | |||||

| 96 | pelvic floor training with vs. without reflex contraction exercises | RCT | changes in the ICIQ short-form questionnaire | 2.9 vs. 3.0 | none |

| Study: De Marco et al. (2022) (e15) | |||||

| 52 | pelvic floor exercises with or without manual therapy | RCT | changes in the ICIQ short-form questionnaire | 10,6 (± 4,9) vs. 11,2 (± 5,7) | none |

| Study: Leonardo et al. (2022) (e16) | |||||

| 562 | pelvic floor exercises with or without biofeedback, and pelvic floor exercises vs. electrostimulation | systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | changes (mean differences) in two symptom questionnaires: King´s Health (KHQ) + Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) | KHQ: –2.8 [-17.1; 11.5] IIQ: –2.5 [-0.5; 5.5] KHQ: 16.5 [6.1; 26.9]* IIQ: 5.3 [1.6; 9.1]* for electrostimulation |

none |

| Study: Wang (2022) (e17) | |||||

| pelvic floor exercises vs. no intervention in women with prolapse | meta-analysis | changes of the mean Prolapse Symptom Score POP-SS and POPQ stage | changes –1.7 [-2.4; 0.9]*RR 1.5 [1.1; 2.0]* long-term data without significant change | none | |

*p ≤ 0.05

ICIQ, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire; POPQ, pelvic organ prolapse quantification; RR, risk ratio

Learning objectives

This paper is intended to help the reader to:

recognize the associations of pregnancy, delivery, postmenopause, and polypharmacy with urogynecological conditions,

know and assess preventive and conservative treatment approaches, and

evaluate the surgical treatments of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse, with or without tissue replacement, with regard to indications and success rates.

Protecting the pelvic floor during pregnancy and delivery

Pregnancy and childbirth can cause pelvic floor dysfunction. Primary caesarean section lowers the risk of urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (1) but cannot be used as a general preventive measure against these problems: 12 women would have to undergo cesarean section to prevent a single case of prolapse, and 8 to prevent a single case of urinary incontinence (2). Yet there are women at high individual risk of postpartum pelvic floor disease who may benefit from elective caesarean section and should at least be informed of this option. UR-Choice is an evidence-based stratification program that can be accessed on the Internet and can estimate the risk from patient-supplied information (box) (3). Likewise, intrapartum factors can influence the postpartum development of pelvic floor dysfunction (box) (4). Peripartum pelvic floor protection measures can lower the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction (box) (4).

Box. Risk factors for, and protection against, pelvic floor dysfunction*.

-

Prepartum risk factors

positive family history of the prospective mother

urinary incontinence before and during pregnancy

ethnicity

maternal age at delivery (> 35 years)

body-mass index (> 25 kg/m²)

estimated birth weight (> 4000 g)

parity

-

Intrapartum risk factors

prolonged delivery (> 120 min)

median or mediolateral episiotomy < 60°

vacuum and forceps delivery

-

Peripartum pelvic floor protection

adequate perineal protection

warm compresses

peridural anesthesia

upright birth position

pre- and postpartum pelvic floor physiotherapy

Prevention and conservative management

Supporting musculoskeletal recovery with physiotherapy is a well-established and well-studied method. If it is begun in a structured manner early on in pregnancy, it can lessen the incidence of urinary incontinence by 62% during pregnancy and by 29% 3–6 months postpartum. Adequate data on the late postpartum period are unavailable (5).

Delivery and caesarean section.

Primary caesarean section lowers the risk of urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse but cannot be used as a general preventive measure against these problems:

There are as yet no scientifically proven measures that facilitate the recovery of pelvic floor connective tissue. Vaginal delivery increases the risk of prolapse in the postmenopausal period by a factor of four or eight compared to caesarean section in first- and second-time mothers, respectively; the risk increases less in further births (6, 7). Pessary therapy is an easily understandable method of opposing downward pressure; it should be offered both prophylactically and as part of the treatment of any symptoms, even mild ones, that might be prolapse-related, even though the scientific data do not yet suffice to establish its efficacy.

The conservative treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction that has already become clinically manifest does not differ from the preventive approaches (etable 1). A directory of competent physiotherapists throughout Germany can be found at www.ag-ggup.de. The efficacy of pelvic floor training has been demonstrated (e1), is independent of age, and depends less on the kind of training than on its intensity (8). Electrostimulation can be offered in addition to pelvic floor training (9); clinical experience suggests it can be offered if the patient cannot adequately control the pelvic floor muscles, or with biofeedback triggering if coordinated contraction is possible. Electrostimulation to treat an overactive bladder differs from that used to treat bladder emptying dysfunction in terms of the nature of the applied current and its mode of application (e.g. transcutaneous tibialis posterior stimulation) and should be given before any invasive treatment.

From the perimenopause onward, local estrogenization, applied over the long term twice weekly, is reasonable in the absence of contraindications. In the absence of scientific data on relative indications, common clinical experience suggests the efficacy of dish pessaries to reposition prolapsed pelvic organs, and of cube pessaries to reposition cystoceles or enteroceles if dishes do not provide enough support. The same holds for patients with a wide levator hiatus (i.e., a gap between the puborectalis muscle of the M. levator ani, limited anteriorly by the pubic bone), which is often the result of a levator avulsion. Rectoceles are less amenable to pessary therapy (e2). In cases of stress urinary incontinence, urethral pessaries with a knob (ring pessaries with a suburethral thickening) and foam tampons can be used for symptomatic treatment.

The pharmacotherapy of urinary incontinence

Drugs are an indispensable part of conservative treatment for the various types of urinary incontinence. Their proper indications and potential side effects must be borne in mind. If a drug is effective and well tolerated, its use over the long term may be the treatment of choice.

Anticholinergic and ß3-sympathomimetic drugs for the treatment of overactive bladder

The risk of prolapse in postmenopause.

Compared to caesarean section, vaginal delivery increases the risk of prolapse in the postmenopausal period by a factor of four in first-time and eight in second-time mothers.

Anticholinergic drugs (also called antimuscarinic drugs) can improve the symptoms of overactive bladder ([OAB]) with or without incontinence ([11]; evidence level [EL] 1, strong consensus). Drugs of this type, including darifenacin, tolterodine/fesoterodine, solifenacin, propiverine, oxybutynin, and trospium chloride, affect the efferent arm of micturition control by blocking the M2 and M3 receptors of the smooth muscle of the bladder (detrusor vesicae) (10), thereby increasing bladder capacity and prolonging the interval between successive micturitions. To avoid side effects that may lead to discontinuation of treatment, sustained-release (timed-release) preparations are generally recommended; the dose can be increased to improve the effect, if necessary. Alternatives include transdermal application to eliminate the first-pass effect, combination with drugs of other classes (instead of dose escalation), or intravesical application if the patient already requires intermittent self-catheterization.

The most common side effects are dry mouth, constipation, accommodation disturbance, and tachycardia (11). In elderly and postmenopausal women, the blood-brain barrier may be more permeable because of degenerative processes, and anticholinergics may be more likely to cause drowsiness, impaired concentration, and even hallucinations and delirium (e3). Thus, the neurologic state of patients taking anticholinergic drugs should be closely monitored, and special care should be taken to note potential anticholinergic preloading in patients taking multiple drugs at once ([9, 12]; strong recommendation). In the absence of comparative studies, no particular anticholinergic drug can be recommended as preferable to the others [13, 14].

Mirabegron (50 mg daily) is a ß3-sympathomimetic drug that relaxes the detrusor muscle in the storage phase of bladder function by stimulating the physiologically noradrenergic ß3-receptors (EL1). Its mechanism of action thus differs fundamentally from that of anticholinergic drugs, and it does not cause typical anticholinergic side effects such an increase in intraocular pressure (which can trigger glaucoma in postmenopausal and elderly patients) (15). In registration studies, mirabegon was found to significantly lower the frequency of incontinence episodes and to improve other outcome parameters compared to placebo in the treatment of bladder overactivity (16).

The treatment of overactive bladder syndrome.

Anticholinergic drugs are the primary treatment of overactive bladder syndrome, but treatment compliance is limited because of side effects.

In contrast to the anticholinergic drugs, mirabegon does not cause dry mouth to any greater extent than placebo (16, 17). Mirabegon is not more effective than the classic anticholinergic drugs, but it is better tolerated, and patients taking it are therefore more likely to adhere to the treatment (18). Because mirabegon is a ß3-sympathomimetic drug, its main side effect is the induction of arterial hypertension. It is contraindicated in patients whose systolic blood pressure exceeds 180 mm Hg or whose diastolic blood pressure exceeds 110 mm Hg. The patient’s blood pressure should be measured before treatment and monitored while under treatment.

Desmopressin for the treatment of nocturia

Desmopressin, also known as DDAVP (1-desamino-8-d-arginine vasopressin), is an antidiuretic drug that has become a well-established treatment for nocturia without identifiable cause in adults since it was approved for this purpose in 2017 ([9, 12]; [EL1]; strong recommendation [“should be offered”]).

DDAVP is dosed differently for men and women, and the need to monitor the serum sodium level must be borne in mind, particularly in postmenopausal and elderly patients [12]. The sodium level should be measured at baseline, during the first week of treatment (day 4 to 8), and again one month later.

The use of ß3-sympathomimetic drugs.

ß3-sympathomimetic drugs are well tolerated and therefore associated with high compliance, but they can induce or worsen arterial hyptertension.

In elderly women, DDAVP-induced hyponatremia with its potential cognitive and neuromuscular effects is a cofactor for falls and delirium. This must be weighed against the potentially fatal consequences of nocturia itself, as nocturia, too, increases the patient’s tendency to fall (12). Moreover, any other medications the patient may be taking need to be continually rechecked for potentially dangerous interactions.

SSNRI for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence

Duloxetine is a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI). It is commonly used as an antidepressant and also has alpha-adrenergic and anticholinergic effects.

Three randomized, placebo-controlled trials have shown that duloxetine, in a dosage of 40 mg bid, lowers the frequency of incontinence episodes by 50%, compared to 30–40% with placebo (20). 10% of treated patients became continent ([9]; [EL1], strong recommendation [“should be offered”]). Some evidence suggests that duloxetine combined with pelvic floor exercises may be more effective than duloxetine alone ([9, 21]; open recommendation).

Postmenopausal and elderly women benefit especially from the favorable side-effect profile of duloxetine, as do patients with cardiovascular diseases. For patients taking multiple drugs, the potential interactions and side effects (e.g., nausea) of duloxetine must be borne in mind, along with the gradually tapering introduction and discontinuation of the drug (strong recommendation).

Surgical treatment

Stress urinary incontinence

More than 25 years ago, a new type of operation for female stress urinary incontinence was introduced by Ulmsten et al. (22, 23) that revolutionized the surgical treatment of stress incontinence. The tension-free alloplastic sling (preferably made of polypropylene), implanted under the middle third of the urethra and brought out behind the pubic bone, stabilizes the pubourethral ligaments and the suburethral fascial structures.

SSNRI for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence.

Some evidence suggests that duloxetine combined with pelvic floor exercises may be more effective than duloxetine alone.

In view of the very good long-term success rates (87.2% patient satisfaction at 17 years, [24]), suburethral tape placement is recommended in the recently updated AWMF guideline on urinary incontinence in women (9) as the exclusive primary treatment in all women with uncomplicated stress incontinence (i.e., those without prior incontinence surgery, neurological symptoms, or pelvic organ prolapse, and for whom further pregnancies are not an issue; [EL1]; strong recommendation). If suburethral tape insertion is not indicated, alternative procedures such as colposuspension, fascial sling insertion, submucosal urethral injection of bulking agents, or artificial sphincter creation may be used, after the patient is thoroughly informed and the surgeon is aware of her expectations, depending on the expertise and preference of the treating center. Vaginal laser therapy is treated as a conservative procedure in the current AWMF guideline; it can be considered for women with incontinence for small amounts of urine (< 10 g in the 1-hour pad test) (open recommendation, [25]).

As the recommendation for treatment is not affected by the findings of further differential diagnostic testing (functional urethral length, urethral hypermobility, maximum urethral closure pressure), urodynamic tests should be performed preoperatively only if they affect the choice of treatment or if complicated stress urinary incontinence is present.

Retropubic placement of suburethral slings is associated with a somewhat higher risk of bladder injury and overcorrection compared with transobturator implantation, which, however, is more likely to cause dyspareunia and inguinal pain and there is less long-term data ([9], strong consensus).

Urge urinary incontinence/bladder overactivity

If the conservative treatment of urge urinary incontinence or bladder overactivity fails, there are two main surgical treatment options, which differ in their duration of action, invasiveness, and patient preference. Conservative treatment fails in 80% of patients after one year for various reasons: unrealistic expectations, intolerable side effects, contraindications, insufficient efficacy (26).

The surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence.

In view of the very good long-term success rates, suburethral tape placement is recommended in the recently updated AWMF guideline on urinary incontinence in women as the exclusive primary treatment in all women with uncomplicated stress incontinence

Intravesical onabotulinum toxin A injection has been approved for primary use in the treatment of overactive bladder at a total dose of 100 U, with injections into the detrusor muscle at 20 different locations in individual doses of 5 U each (simple recommendation [“can be offered”]). The definition of an overactive bladder requires the exclusion of neurological causes (for which higher doses of toxin are needed) and of other defined disease entities affecting the urinary tract. The procedure can be performed on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia, but hospitalization and treatment under regional or general anesthesia are recommended in cases that will also involve hydrodistention (bladder distention with a hydrostatic irrigation fluid pressure of 60 cm H2O) and bladder biopsy for the detection or exclusion of carcinoma in situ or interstitial cystitis. Although onabotulinum toxin A irreversibly inhibits preterminal acetylcholine degranulation by inactivating the membrane-bound transport protein SNAP 25, a single treatment does not have a lifelong effect, because of the regeneration of nerve terminals and the synthesis of new SNAP 25. In idiopathic overactive bladder, diminution of the effect is to be expected within 6–9 months, necessitating reinjection. Patient preference surveys have revealed that many patients decline ona-botulinum toxin injections for fear of complications of the regularly repeated transurethral procedures (urinary tract infections, strictures, bladder voiding dysfunction with need for self-catheterization). This type of treatment seems particularly suitable for elderly patients, as the expected total number of injections is proportional to the patient’s life expectancy, and multiple injections may lead to tachyphylaxis (although there are no scientific data on this point).

As onabotulinum toxin injections into the detrusor are not very effective against sensory urge without detrusor instability (27), pre-interventional urodynamic studies to differentiate between sensory and motor urge may aid in patient selection and help lower the high treatment dropout rate, which is 70% at five years (28).

Urge urinary incontinence / bladder overactivity.

If surgery for an overactive bladder is planned, the two main surgical options must be weighed against each other: onabotulinum toxin A injection and sacral neuromodulation.

In younger patients who feel comfortable with high technology, bladder overactivity that has failed to respond to conservative treatment can be treated with uni- or bilateral sacral neuromodulation (strong recommendation [“should be offered”]. Minimally invasive test stimulation, known as percutaneous neuroevaluation (PNE), should be carried out before permanent implantation. PNE is particularly suitable for women who have been found to benefit, at least to some extent, from non-surgical peripheral neuromodulation methods involving vaginal electrodes or posterior tibial nerve stimulation. (The latter is a method for neuromodulatory stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system at the level of the sacral plexus, leading to detrusor relaxation and increased urethral sphincter tone; its precise mechanism of action is not known.) Successful test stimulation predicts long-term therapeutic success. Finite battery capacity necessitates periodic reoperations to replace the neuromodulator device, at intervals of about five years. Studies have shown that 67% of the women with bladder overactivity who are treated with neuromodulation are satisfied and comply with therapy (29). Unlike onabotulinum toxin A, sacral neuromodulation is equally effective for sensory and motor urge (30). Some of the previously existing limitations on the practical utility of neuromodulation have now been obviated by the development of electromagnetically rechargeable neuromodulators that do not need to be surgically replaced, and by the development of MRI-compatible electrodes and devices.

The treatment of extraurethral urinary incontinence

Extraurethral urinary incontinence is usually caused by a vesicovaginal fistula arising iatrogenically after surgery. If the patient reports the postoperative loss of urine without straining or urge, either immediately (because of a lesion that arose directly during surgery) or after an interval of approximately 10 days (because of a fistula resulting from tissue necrosis), an attempt can be made to treat conservatively with temporary urinary diversion. On the other hand, postoperative fistulae that have been present for three months or more or are due to radiotherapy require surgical closure. This should only be performed in a center with special expertise in fistula surgery (31, 32).

The surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse

Without or with tissue replacement

An alternative for younger patients.

In younger patients who feel comfortable with high technology, bladder overactivity that has failed to respond to conservative treatment can be treated with uni- or bilateral sacral neuromodulation

Typical symptoms of prolapse include a dragging and foreign-body sensation, a bulge in the vaginal introitus, and bladder and bowel emptying dysfunction. Stress and urge incontinence may be present simultaneously, but huge prolapses tend be accompanied by micturition disorders with high residual volumes, leading to frequency, urgency, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Manifestations of these types are an indication for surgical treatment if the patient so desires and/or conservative treatment with a pessary has failed (33).

A prerequisite to joint decision-making on individualized treatment is the detailed evaluation of the descending compartments and the associated symptoms. Moreover, the appropriate surgical treatment(s) needs to be chosen from a wide range of options, with attention to the issues of simultaneous total or subtotal hysterectomy, opportunistic salpingectomy, or adnexectomy, as well as preventive or therapeutic continence surgery. Note should also be taken of the patient’s specific wishes, e.g., absence of a vaginal scar for optimally preserved sexual function, keeping the uterus, avoiding (or using) alloplastic material, a vaginal, laparoscopic, or combined procedure, and the preferred type of anesthetic. Patients should be told that mesh complications are more common in smokers (33).

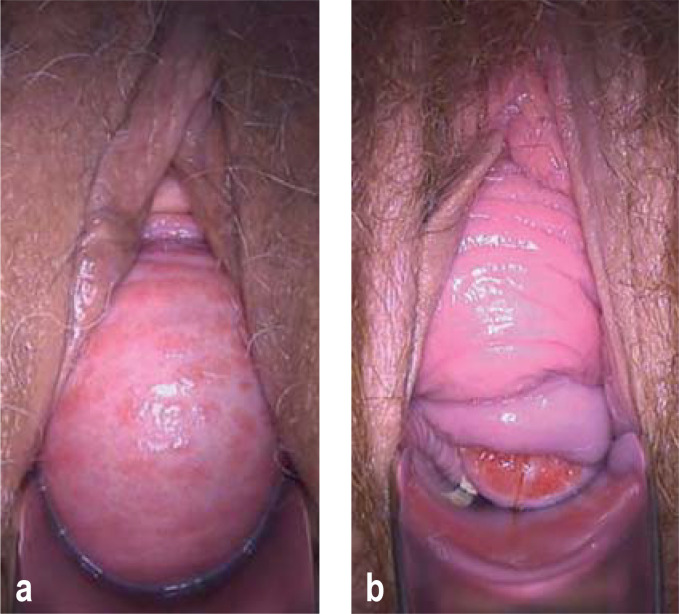

With autologous tissue/fascial reconstruction

In the primary situation, surgery with autologous tissue is usually possible (33, 34). In the case of a cystocele due to a median defect (Figure 1a) of the anterior endopelvic fascia, anterior colporrhaphy is a good option (EL1). Prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall with preservation of the vaginal rugae, due to lateral avulsion at the arcus tendineous fasciae pelvis (Figure 1b), can be treated with paravaginal defect repair, or indirectly with an apical prolapse operation (EL3). The surgeon must be aware that there is usually an accompanying support defect in the middle compartment (33, 35), which should be corrected at the same time (e4) to improve success rates (69% vs. 54%; [EL3]; [33]).

Figure 1:

a) Cystocele through a central fascial defect with flattening of the vaginal rugae and atrophic colpitis

b) Cystocele through a lateral defect with preserved vaginal rugae and uterine prolapse

For apical fixation of the uterus or vaginal vault, transvaginal or laparoscopic uterosacral ligament plication or transvaginal sacrospinal fixation can be performed with success rates of approximately 90% (33, 34) (EL1). The urogynecological success rate is the same with uterus preservation or with concurrent hysterectomy (36) (EL1). Subsequently, uterus-preserving surgery should be offered if the uterus is otherwise healthy (but with caution in the presence of cervical elongation).

Prolapse surgery.

A prerequisite to joint decision-making on individualized treatment is the detailed evaluation of the descending compartments and the associated symptoms.

Rectocele is treated by posterior colporrhaphy, with success rates around 80% (33, 34, 37) (EL1). Patients with dysfunctional defecation but without any subjective sensation of prolapse can be treated alternatively with transanal surgery (EL1). If rectal prolapse is present at the same time, an interdisciplinary evaluation should be carried out to determine whether, for example, simultaneous anterior rectopexy with hystero- or colpopexy may be appropriate

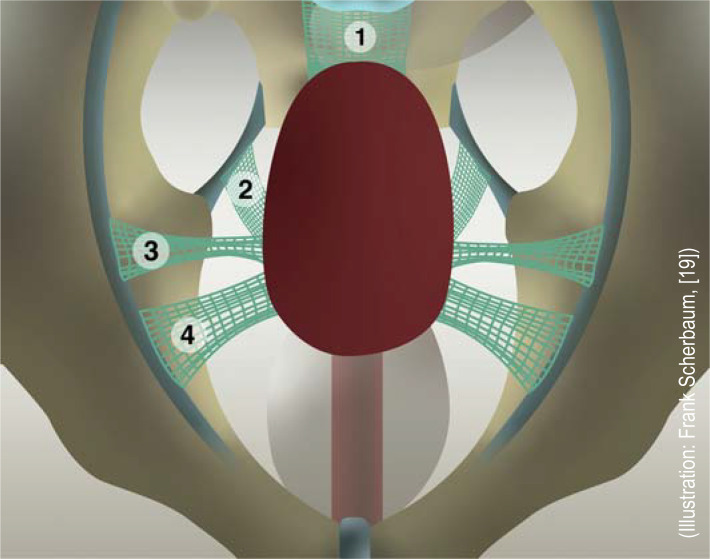

With tissue replacement

Prolapse surgery with autologous tissue.

In the primary situation, surgery with autologous tissue (by fascial reconstruction) is usually possible

After the U. S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about the potential complications of vaginal mesh surgery, the medical device classification of vaginal mesh was changed and the manufacturers were asked to provide further data; failing this, a number of countries introduced a moratorium or ban on the use of vaginal mesh. It is recommended by the Working Group on Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Reconstruction, as well as in the German-language, evidence-based AWMF guideline, that alloplastic materials should be used in vaginal surgery for prolapses only to treat recurrences, if there is an increased risk of recurrence, or in accordance with the patient’s wishes (e5). This statement does not pertain to the abdominal use of mesh, which has a lower rate of complications than vaginal use (including dyspareunia) (e6). The current standard is type 1 mesh (lightweight, large-pored, monofilament) mesh, made of polypropylene or polyvinylidene fluoride. Biological allografts (made of, e.g., porcine mucous membranes or fascia lata) were not superior to autologous tissue in any way (33, 34). Options in uterus-preserving surgery include vaginal bilateral sacrospinal fixation with thin mesh arms (EL3), laparoscopic sacrohystero- or cervicopexy with mesh interposition between the sacrum and the cervix (EL2), and bilateral pectopexy involving fixation with mesh arms at the iliopectineal ligament (EL3) (34, Figure 2). On the other hand, when hysterectomy is performed, sacrocolpopexy with mesh extension both anteriorly (to bladder neck) and posteriorly (to the level of the levator ani muscles) addresses all support defects and achieves 5-year success rates of more than 90% (33, 34, 38) (EL1).

Figure 2.

Mesh-assisted hysteropexy techniques:

1) sacrohysteropexy, 2) vaginal sacrospinous bilateral hysteropexy, 3) hysteropexy according to Dubuisson (mesh running retroperitoneally toward the ventrolateral abdominal wall), 4) pectopexy according to Noè.

Alloplastic tissue replacement in the anterior compartment, e.g., with bilateral sacrospinous hystero- or colpopexy, can be considered for recurrent or large prolapses, levator defects due to vaginal delivery, obesity, or heavy physical labor, or if the patient desires the best anatomic surgical outcome with a transvaginal approach (33, 39). Current mesh systems can be used to repair cystoceles and apical defects at the same time, with anatomic and subjective success rates over 90% (EL1) (33, 34, 39).

Complications such as vesical, vaginal, and rectal mesh erosion, and extensive scarring causing pain, dyspareunia, and vaginal shortening, are rare but may necessitate (usually partial) mesh removal with no guarantee of success. Simple vaginal mesh erosions can be repaired locally with estriol and partial removal if necessary. There is no evidence to support the use of vaginal mesh in the posterior compartment (34, 37) (EL1). In general, concomitant hysterectomy should be avoided when synthetic mesh is used, because this increases the mesh-related complication rate (33, 34) (EL3).

In case of simultaneous stress urinary incontinence

If the prolapse is accompanied by stress urinary incontinence, either symptomatic or masked (i.e., urinary leakage after prolapse repositioning/under pessary therapy), simultaneous continence surgery should be offered (EL1). For vaginal procedures, suburethral tape insertion is most appropriate for this purpose. For abdominal procedures, Burch colposuspension may be appropriate. Prophylactic continence surgery should be avoided (EL1), given the low risk of de novo stress urinary incontinence (34, 40).

Prolapse surgery with tissue replacement.

The use of alloplastic materials in vaginal surgery for prolapses is recommended only to treat recurrences, if there is an increased risk of recurrence, or in accordance with the patient’s wishes.

Supplementary Material

Case report

A 64-year-old woman presents to a pelvic floor center complaining of a vaginal foreign body sensation and pollakisuria. She states that a urinary tract infection has already been ruled out and that she has already been given a prescription for solifenacin 5 mg qd. The pollakisuria worsened while she was taking this drug; only small amounts of urine could be voided each time despite the urge to urinate, and she sporadically lost urine upon standing up. Solifenacin was discontinued for these reasons, and darifenacin was prescribed; urination became easier again, but pollakisuria persisted. Darifenacin was discontinued as well because of worsening constipation. Gynecological examination revealed a third-degree cystocele and first-degree uterine prolapse; no rectocele was detected, and ultrasonography revealed a residual urine volume of 150 mL aside from the cystocele. As a conservative measure, a sieve cup pessary was inserted, a pessary change in four weeks was planned, and vaginal estrogenization twice a week was prescribed. At four weeks, the patient reported that, despite the pessary, the feeling of pressure and pollakisuria had not improved. The sieve cup pessary was removed, and a cube pessary was prescribed with instructions that it should be inserted every morning and removed in the evening. Under this treatment, the sensation of descent improved and micturition became less frequent, and there was no longer any residual urine after micturition. The daily pessary change was not tolerated, and an alternative was agreed upon with the patient: surgical transvaginal correction of the cystocele with fascial reconstruction.

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 2 February 2024. Submissions by letter, e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

The completion time for all newly started CME units is 12 months. The results can be accessed 4 weeks following the start of the CME unit. Please note the respective submission deadline at: cme.aerzteblatt.de

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. CME points can be managed using the “uniform CME number” (einheitliche - Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or entered in “Meine Daten”, and consent must be given for results to be communicated. The 15-digit EFN can be found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX).

eTable 2. Current key studies on the pharmacotherapy of urinary incontinence in women.

| n | Comparison | Study design | Primary endpoint | Results [95% CI] | Adverse events |

| Study: Chapple et al. (2013) (e18) | |||||

| 928 | mirabegron 25, 50, 100, 200 mg vs. placebo vs. tolterodin (ER) 4 mg |

RCT single-/double-blinded, placebo-controlled |

reduction of urinary frequency/24 hr | [- 1,9; – 2,1] ; [2,1; – 2,2] vs. 1.4 vs. 2.0* |

increased heart rate with mirabegron 100 (1.3%) and 200 (3%) mg vs. placebo (0.6%) vs. tolterodine (1.2%) |

| Study: Wagg et al. (2017) (e19) | |||||

| 4040 | fesoterodine 4 or 8 mg vs. placebo | RCT, double-blinded, placebo-controlled | reduction of urinary incontinence episodes and urinary frequency/24 hr | – 1.1 vs. – 0.5* – 2.4 vs. – 1.5* |

dose reduction because of side effects: fesoterodine 4 mg 3%, 8 mg 1%, placebo 1% |

| Study: Nitti et al. (2013) (e20) | |||||

| 557 | botulinum toxin 100 U vs. placebo at 12 weeks | RCT double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase 3 trial |

reduction of the number of incontinence episodes per day | – 2.65 vs. – 0.87* complete continence 22.9 % vs. 6.5% |

uncomplicated urinary tract infection 15.5 % vs. 5.9 %intermittent self-catheterization 6.1 % vs. 0 % |

| Study: Sand et al. (2017) (e21) | |||||

| 261 | desmopressin 25 μg vs. placebo | randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, placebo-controlled | reduction of nocturia | – 1.46 vs. 1.24* | none |

| Study: Mirzaei et al. (2021) (e22) | |||||

| 60 | solifenacin (10 mg) vs. duloxetin (20 mg) | RCT, single-blinded | questionnaire (ICIQ-OAB) | from 14.86 to 9.66* vs. from 13.90 to 8.76* no difference between groups |

side effects: dry mouth, lack of appetite 33.3% and 20% vs. 26.7% and 16.7%* |

CI, confidence interval; ICIQ-OAB, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Overactive bladder; RCT, randomized controlled trial; *p ≤ 0.05

eTable 3. Current key studies on the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women.

| n | Comparison | Study design | Primary endpoint | Results [95% CI] | Adverse events |

| Study: Schellart et al. (2014) (e23) | |||||

| 193 | MiniArc vs. TOT | randomized, non-blinded, non-inferiority design | Improved PGI-I score | MiniArc is not inferior to TOT after 3 years | 13% serious adverse events with MiniArc, 11% with TOT |

| Study: Itkonen Freitas et al. (2022) (e24) | |||||

| 223 | TVT vs. polyacrylamide hydrogel (bulkamide) |

randomized, non-blinded, non-inferiority design | patient satisfaction questionnaire | bulkamide is inferior to TVT at 3 years* | 43.5% complication rate for DVT, 24% for bulkamide* |

| Study: Dogan et al. (2018) (e25) | |||||

| 201 | needle-free single-incision muscular sling (SIMS) vs. TOT | randomized, non-blinded, single-center | negative cough test | SIMS and TOT are comparably effective at 2 years (90% vs. 85% cure) | 13% complication rate with TOT, 7% with SIMS* (SIMS significantly fewer symptoms) |

| Study: Holdø et al. (2017) (e26) | |||||

| 307 | Burch colposuspension vs. TVT | non-randomized, non-simultaneous case series comparison | recurrent incontinence | revision rates at 12 years, 11% (colposuspension) vs. 2% (TVT)* |

16% complication rate with colposuspension vs. 11% with TVT |

| Study: Lau et al. (2013) (e27) | |||||

| 100 | TOT vs. TOT after vaginal prolapse net (Prolift) | non-randomized, prospective case series comparison | negative cough test | at 3–6 months, 86% cure rate for TOT versus 62% for TOT after vaginal mesh* | 9% complication rate with TOT after vaginal mesh vs. 0% with TOT* |

| Study: Ward KL (2008) (e28) | |||||

| 344 | Burch colposuspension vs. TVT | prospectively randomized, non-blinded multicenter trial | negative 1 hour pad test | at 5 years, 81% cure rate for colposuspension vs. 90% for TVT | more recto- and enteroceles with colposuspension*, complication rate 11% with colposuspension vs. 8% with TVT |

| Study: Karmakar (2017) (e29) | |||||

| 341 | transobturator tape, inside-out vs. outside-in | postal follow-up of a randomized, controlled trial | patient satisfaction, measured with the PGI-I | 71.6 % satisfaction and 14% improvement | in 7.96% new urinary incontinence surgery required, 4.5% erosion rate, 4.32% pain, in 1.4% therapy required |

| Study: Dejene et al. (2022) (e30) | |||||

| 334 601 | follow-up of up to 15 years | cohort study | Frequency of of surgical revisions | at 10 years, 6.9%; at 15 years, 7.9% increased risk of surgical revision, in women aged 18–29 vs. ≥ 70 years |

approx. 50 % of surgical revisions necessitated by tape erosion |

PGI-I, Patient Global Impression Incontinence; TOT, transobturator tape; TVT, tension-free vaginal tape“ (retropubic);

*p ≤ 0.05

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 2 February 2024.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which selective serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor has been shown in randomized, controlled trials to lessen the frequency of incontinence episodes?

venlafaxine

milnacipran

duloxetine

desvenlaflaxine

levomilnacipran

Question 2

What is the most important adverse effect of the ß 3–sympathomimetic drug mirabegran?

glaucoma

constipation

arterial hypertension

urinary retention

cognitive dysfunction

Question 3

What should be monitored in postmenopausal and elderly women taking desmopressin?

serum sodium

serum potassium

serum calcium

oxygen saturation

blood pressure

Question 4

What conclusion regarding the treatment of urogenital descent can be drawn from the studies of Lucot et al. (2018, 2022)?

Transvaginal nets are associated with a lower risk of dyspareunia than sacrocolpopexy.

Sacrouterine ligament fixation is markedly superior to sacrospinal fixation.

Laparoscopy has a higher complication rate than open surgery and should therefore only be performed in selected cases.

Sacrocolpopexy is associated with a lower risk of dyspareunia than the surgical implantation of transvaginal nets.

Pectopexy is not an option for the treatment of apical descent.

Question 5

What is the preferred primary surgical treatment for women with uncomplicated stress incontinence, according to the updated AWMF guideline?

vaginal laser treatment

colposuspension

fascial sling procedure

suburethral alloplastic band insertion

urethral bulkamide injection

Question 6

A 70-year-old woman presents with a large recurrent stage 3 cystocele and descent of the normal-sized uterus to the introitus. Pessaries are inadequate to correct the descent in the presence of major levator defects. What should be recommended as the first choice of surgical treatment?

vaginal hysterectomy and anterior vaginoplasty

vaginal hysterectomy und anterior vaginal net insertion

laparoscopic hysterectomy and sacrocolpopexy

anterior vaginal net insertion with bilateral sacrospinal hysteropexy

anterior and posterior vaginoplasty

Question 7

What properties characterize the synthetic nets that are the current standard for alloplastic tissue inserts in urogynecology?

lightweight, small-pore, multifilament

lightweight, large-pore, monofilament

heavy, large-pore, bifilament

heavy, small-pore, monofilament

middleweight, intermediate-pore, multifilament

Question 8

A multimorbid, obese 78-year-old woman with an overactive bladder complains of daily episodes of urinary incontinence. Even though she uses pads, she often has to change her underwear, because her bladder empties almost completely after the urge episodes. What treatment should be recommended?

desmopressin 5–10 mg/day

solifenacin 100 mg/day

mirabegron 100 mg/day

hydrodistention of the bladder and injection of 100 U onabotulinum toxin

sacral neuromodulation

Question 9

The conservative management of urinary urge incontinence fails by one year in what percentage of women so treated?

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

Question 10

A thin 24-year-old woman gave birth to a daughter (birth weight 3200 g) by spontaneous vaginal delivery three years ago and suffered for approximately 6 months afterward from stress urinary incontinence, which she was able to control successfully with pelvic floor exercises. She is now pregnant again and fears that a second spontaneous vaginal delivery could make her incontinent again, but this time permanently, even though her mother has no such problems to this day. She plans to have no more than two children. How should she be advised?

follow a wait-and-see strategy

plan a primary caesarean section with simultaenous hysterectomy and surgical repair of the retaining mechanism of the pelvis

take hormones during pregnancy

targeted physical therapy during pregnancy and post partum; use UR Choice in case of concern

laser treatment after the puerperium

► Participation is possible only via the internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Hampel has serves as a paid consultant for Apogepha and Roche. He has received lecture honoraria from Apogepha, Astellas, and Pfizer and fees for manuscript preparation from the publisher Springer Nature. His travel costs have been reimbursed by the German Society of Urology, the German Continence Society, and Springer Nature.

Prof. Tunn receives patent royalties from Viomed for the Restifem pessary, which is not mentioned in the manuscript, but is used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. He has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees from the German Society of Gynecology/Obstetrics, the Nordic Urogynecological Association (NUGA), and the German Continence Society, as well as reimbursement of travel and accommodation expenses from the latter two companies. He has served as an unpaid member of both the scientific advisory board of the DGGG Urogynecology Working Group and the scientific advisory board of the journal „gynäkologie & geburtshilfe“ (until 2021). He is an unpaid contributor to the AWMF guidelines on urinary incontinence in women (updated in 2022) and pelvic organ prolapse in women (update expected to be issued in early 2023). His research is supported by Promedon through payments to his institution’s third-party funding account.

PD Dr. Baessler has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and travel costs from the Association for Urogynecology, the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics, the German Continence Society, and the International Urogynecological Association. She is president of the AGUB and is in charge of the development of the AWMF guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, and is also editor-in-chief of the International Urogynecology Journal.

PD Dr. Knüpfer declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Lopez-Lopez AI, Sanz-Valero J, Gomez-Perez L, Pastor-Valero M. Pelvic floor: vaginal or caesarean delivery? A review of systematic reviews. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;7:1663–1673. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gyhagen M, Bullarbo M, Nielsen TF, Milsom I. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse 20 years after childbirth: a national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. BJOG. 2013;120:152–160. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D, Dorman J, Milsom I, Freeman R. UR-CHOICE: can we provide mothers-to-be with information about the risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction? Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1449–1452. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2376-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hübner M, Rothe C, Plappert C, Baeßler K. Aspects of pelvic floor protection in spontaneous delivery—a review. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2022;82:400–409. doi: 10.1055/a-1515-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodley StJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub4. CD007471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akervall S, Al-Mukhtar Othman J, Molin M, Gyhagen M. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in middle-aged women: a national matched cohort study on the influence of childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:356.e1–356e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hage-Franse MAH, Wiezer M, Otto A, et al. Pregnancy- and obstetric-related risk factors for urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse later in life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:373–382. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay-Smith EJ, Herderschee R, Dumoulin C, Herbison GP. Comparisons of approaches to pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009508. CD009508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reisenauer C, Naumann G. AWMF-Leitlinie Harninkontinenz, Registernummer 015-091, 2022. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/015-091l_S2k_Harninkontinenz-der-Frau_2022-03.pdf (last accessed on 3 January 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansfield KJ, Chandran JJ, Vaux KJ, et al. Comparison of receptor binding characteristics of commonly used muscarinic antagonists in human bladder detrusor and mucosa. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:893–899. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider T, Michel MC. Anticholinergic treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Is it all the same? Urologe A. 2009;48;:245–249. doi: 10.1007/s00120-008-1915-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiedemann A, Becher K, Bojack B, Ege S, von der Heide S, Kirschner-Hermanns R. S2e-Leitlinie 084-001, Harninkontinenz bei geriatrischen Patienten, Diagnostik und Therapie. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/084-001l_S2e_Harninkontinenz_geriatrische _Patienten_Diagnostik-Therapie_2019-01.pdf (last accessed on 3 January 2023) 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay G, Crook T, Rekeda L, et al. Differential effects of the antimuscarinic agents darifenacin and oxybutynin ER on memory in older subjects. Eur Urol. 2006;50:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staskin D, Kay G, Tannenbaum C, et al. Trospium chloride is undetectable in the older human central nervous system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1618–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novack GD, Lewis RA, Vogel R, et al. Randomized, double-masked, placebo controlled study to assess the ocular safety of mirabegron in healthy volunteers. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29:674–680. doi: 10.1089/jop.2012.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapple C, Khullar V, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy of the beta3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder by severity of incontinence at baseline: a post hoc analysis of pooled data from three randomised phase 3 trials. Eur Urol. 2015;67:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagg A, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of the beta3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron for the treatment of symptoms of overactive bladder in older patients. Age Ageing. 2014;43:666–675. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapple CR, Nazir J, Hakimi Z. Persistence and adherence with mirabegron versus antimuscarinic agents in patients with overactive bladder: a retrospective observational study in UK clinical practice. Eur Urol. 2017;72:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunn R, Schär G, Aigmüller T, Hübner M. Operative Therapie des Deszensus Urogynäkologie in Praxis und Klinik. In: Tunn R, Hanzal E, Perucchini D, editors. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin, Boston: 2021. 466 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Lange R, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of European and Canadian women with stress urinary incontinence. BJOG. 2004;111:249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghoniem GM, Van Leeuwen JS, Elser DM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine alone, pelvic floor muscle training alone, combined treatment and no active treatment in women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005;173:1647–1653. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154167.90600.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulmsten U, Johnson P, Petros P. Intravaginal slingplasty. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1994;116:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmsten U, Petros P. Intravaginal slingplasty (IVS): an ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29:75–82. doi: 10.3109/00365599509180543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson CG, Palva K, Aarnio R, et al. Seventeen years‘ follow-up of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1265–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuszka A, Gamper M, Walser C, Kociszewski J, Viereck V. Erbium: YAG laser treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: midterm data. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:1859–1866. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chancellor MB, Migliaccio-Walle K, Bramley TJ, Chaudhari SL, Corbell C, Globe D. Long-term patterns of use and treatment failure with anticholinergic agents for overactive bladder. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1744–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowson C, Sahai A, Watkins J, Dasgupta P, Khan MS. The safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin-A in the management of bladder oversensitivity: a randomised double blind placebo-controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:698–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcelissen TA, Rahnama‘i MS, Snijkers A, Schurch B, De Vries P. Long-term follow up of intravesical botulinum toxin-A injections in women with idiopathic overactive bladder symptoms. World J Urol. 2017;35:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1862-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel S, Noblett K, Mangel J, et al. Five-year follow up results of a prospective, multicenter study of patients with overactive bladder treated with sacral neuromodulation. J Urol. 2018;199:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groenendijk PM, Lycklama à Nyeholt AA, Heesakkers JP, van Kerrebroeck PE, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation study group. Urodynamic evaluation of sacral neuromodulation for urge urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2008;101:325–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hampel C, Neisius A, Thomas C, Thu¨roff JW, Roos F. Vesicovaginal fistula Incidence, etiology and phenomenology in Germany. Urologe A. 2015;54:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s00120-014-3679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moergeli C, Tunn R. Vaginal repair of nonradiogenic urogenital fistulas. In Urogynecol J. 2021;32:2449–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04496-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baessler K, Aigmuller T, Albrich S, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of female pelvic organ prolapse Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S2e-Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/006, April 2016) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:1287–1301. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maher CF, Baessler KK, Barber MD, et al. Summary: 2017 international consultation on incontinence evidence-based surgical pathway for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:30–36. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Lisse S, Larson K, Berger MB, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. Structural failure sites in anterior vaginal wall prolapse: identification of a collinear triad. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:853–862. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803–1813. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mowat A, Maher D, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Maher C. Surgery for women with posterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012975. CD012975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012376. CD012376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012079. CD012079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Maher C, Haya N, Crawford TJ, Brown J. Surgery for women with pelvic organ prolapse with or without stress urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013108. CD013108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Bascur-Castillo C, Carrasco-Portiño M, Valenzuela-Peters R, Orellana-Gaete L, Viveros-Allende V, Ruiz Cantero MT. Effect of conservative treatment of pelvic floor dysfunctions in women: an umbrella review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159:372–391. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Lange R, Hübner M, Tunn R. Pessartherapie beim Descensus urogenitalis Urogynäkologie in Praxis und Klinik. In: Tunn R, Hanzal E, Perucchini D, editors. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin, Boston: 2021. pp. 442–450. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Lisibach A, Gallucci G, Benelli V, et al. Evaluation of the association of anticholinergic burden and delirium in older hospitalised patients-a cohort study comparing 19 anticholinergic burden scales. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:4915–4927. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Eibler KS, Alperin M, Khan A, et al. Outcomes of vaginal prolapse surgery among female medicare beneficiaries: the role of apical support. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:981–987. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a8a5e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Ng-Stollmann N, Fünfgeld C, Gabriel B, et al. The international discussion and the new regulations concerning transvaginal mesh implants in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:1997–2002. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04407-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Verghese TS, Middleton L, Cheed V, Leighton L, Daniels J, Latthe PM. LOTUS trial collaborative group Randomised controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness of local oestrogen treatment in postmenopausal women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery (LOTUS): a pilot study to assess feasibility of a large multicentre trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025141. e025141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Chiengthong K, Ruanphoo P, Chatsuwan T, Bunyavejchevin S. Effect of vaginal estrogen in postmenopausal women using vaginal pessary for pelvic organ prolapse treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:1833–1838. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04821-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Lillemon JN, Karstens L, Nardos R, Garg B, Boniface ER, Gregory WT. The impact of local estrogen on the urogenital microbiome in genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomized-controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28:e157–e162. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Propst K, Mellen C, O‘Sullivan DM, Tulikangas PK. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100–105. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Boyd SS, Subramanian D, Propst K, O‘Sullivan D, Tulikangas P. Pelvic organ prolapse severity and genital hiatus size with long-term pessary use. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:e360–e362. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Nekkanti S, Wu JM, Hundley AF, Hudson C, Pandya LK, Dieter AA. A randomized trial comparing continence pessary to continence device (Poise Impressa®) for stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:861–868. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04967-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Stafne SN, Dalbye R, Kristiansen OM, et al. Antenatal pelvic floor muscle training and urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled 7-year follow-up study. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:1557–1565. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-05028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Luginbuehl H, Lehmann C, Koenig I, Kuhn A, Buergin R, Radlinger L. Involuntary reflexive pelvic floor muscle training in addition to standard training versus standard training alone for women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:531–540. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.De Marco M, Arbieto ERM, Da Roza TH, Resende APM, Santos GM. Effects of visceral manipulation associated with pelvic floor muscles training in women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022;41:399–408. doi: 10.1002/nau.24836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Leonardo K, Seno DH, Mirza H, Afriansyah A. Biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training and pelvic electrical stimulation in women with overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022;41:1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/nau.24984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Wang T, Wen Z, Li M. The effect of pelvic floor muscle training for women with pelvic organ prolapse: a meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:1789–1801. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Chapple CT, Dvorak V, Radziszewaki P, et al. A phase II dose-ranging study of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1447–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2042-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Wagg A, Arumi D, Herschorn S, et al. A pooled analysis of the efficacy of fesoterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder, and the relationship between safety, co-morbidity and polypharmacy in patients aged 65 years or older. Age and Ageing. 2017;46:620–626. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Nitti V, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of a phase 3, randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2013;189:2186–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Sand P, Dmochowski R, Reddy J, van der Meulen E. Efficacy and safety of low dose desmopressin orally disintegrating tablet in women with nocturia: results of a multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group study. J Urol. 2013;190:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Mirzaei M, Daneshpajooh, Anvari S, Dozchizadeh S, Teimourian M. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy and complications of duloxetine in comparison to solifenacin in the treatment of overactive bladder disease in women: a randomized clinical trial. Urol J. 2021;18:543–548. doi: 10.22037/uj.v18i.6274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Schellart RP, Rengerink KO, Van der Aa F, Lucot JP. A randomized comparison of a single-incision midurethral sling and a transobturator midurethral sling in women with stress urinary incontinence: results of 12-mo follow-up. Eur Urol. 2014;66:1179–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Itkonen Freitas AM, Isaksson C, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Tulokas S, Mentula M, Mikkola TS. Tension-free vaginal tape and polyacrylamide hydrogel injection for primary stress urinary incontinence: 3-year follow up from a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2022;208:658–667. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Dogan O, Kaya AE, Pulatoglu C, Basbug A, Yassa M. A randomized comparison of a single-incision needleless (Contasure-needleless®) mini-sling versus an inside-out transobturator (Contasure-KIM®) mid-urethral sling in women with stress urinary incontinence: 24-month follow-up results. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1387–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Holdø B, Verelst M, Svenningsen R, Milsom I, Skjeldestad FE. Long-term clinical outcomes with the retropubic tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure compared to Burch colposuspension for correcting stress urinary incontinence (SUI) Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:1739–1746. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Lau HH, Su TH, Huang WC, Hsieh CH, Su CH, Chang RC. A prospective study of transobturator tape as treatment for stress urinary incontinence after transvaginal mesh repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1639–1644. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Ward KL, Hilton P. Tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: 5-year follow up. BJOG. 2008;115:226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Karmakar D, Mostafa A, Abdel-Fattah M. Long-term outcomes of transobturator tapes in women with stress urinary incontinence: E-TOT randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2017;124:973–981. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Dejene SZ, Funk MJ, Pate V, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes after midurethral mesh sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28:188–193. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.van IJsselmuiden MN, van Oudheusden A, Veen J, et al. Hysteropexy in the treatment of uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy versus sacrospinous hysteropexy—a multicentre randomised controlled trial (LAVA trial) BJOG. 2020;127:1284–1293. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Lucot JP, Cosson M, Bader G, et al. Safety of vaginal mesh surgery versus laparoscopic mesh sacropexy for cystocele repair: results of the prosthetic pelvic floor repair randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2018;74:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Lucot JP, Cosson M, Verdun S, et al. Long-term outcomes of primary cystocele repair by transvaginal mesh surgery versus laparoscopic mesh sacropexy: extended follow up of the PROSPERE multicentre randomised trial. BJOG. 2022;129:127–137. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Bataller E, Ros C, Anglès S, Gallego M, Espuña-Pons M, Carmona F. Anatomical outcomes 1 year after pelvic organ prolapse surgery in patients with and without a uterus at a high risk of recurrence: a randomised controlled trial comparing laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy/cervicopexy and anterior vaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:545–555. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3702-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Coolen AWM, van IJsselmuiden MN, van Oudheusden AMJ, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus vaginal sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse, a randomized controlled trial: SALTO-2 trial, study protocol. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Noé KG, Schiermeier S, Alkatout I, Anapolski M. Laparoscopic pectopexy: a prospective, randomized, comparative clinical trial of standard laparoscopic sacral colpocervicopexy with the new laparoscopic pectopexy-postoperative results and intermediate-term follow-up in a pilot study. J Endourol. 2015;29:210–215. doi: 10.1089/end.2014.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, IntHout J, Kluivers KB, van Eijndhoven HWF. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational follow-up of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1554–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Ahmed AA, Abdellatif AH, El-Helaly HA, et al. Concomitant transobturator tape and anterior colporrhaphy versus transobturator subvesical mesh for cystocele-associated stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2019;31:1633–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Case report

A 64-year-old woman presents to a pelvic floor center complaining of a vaginal foreign body sensation and pollakisuria. She states that a urinary tract infection has already been ruled out and that she has already been given a prescription for solifenacin 5 mg qd. The pollakisuria worsened while she was taking this drug; only small amounts of urine could be voided each time despite the urge to urinate, and she sporadically lost urine upon standing up. Solifenacin was discontinued for these reasons, and darifenacin was prescribed; urination became easier again, but pollakisuria persisted. Darifenacin was discontinued as well because of worsening constipation. Gynecological examination revealed a third-degree cystocele and first-degree uterine prolapse; no rectocele was detected, and ultrasonography revealed a residual urine volume of 150 mL aside from the cystocele. As a conservative measure, a sieve cup pessary was inserted, a pessary change in four weeks was planned, and vaginal estrogenization twice a week was prescribed. At four weeks, the patient reported that, despite the pessary, the feeling of pressure and pollakisuria had not improved. The sieve cup pessary was removed, and a cube pessary was prescribed with instructions that it should be inserted every morning and removed in the evening. Under this treatment, the sensation of descent improved and micturition became less frequent, and there was no longer any residual urine after micturition. The daily pessary change was not tolerated, and an alternative was agreed upon with the patient: surgical transvaginal correction of the cystocele with fascial reconstruction.