Abstract

During axon degeneration, NAD+ levels are largely controlled by two enzymes: nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 (NMNAT2) and sterile alpha and toll interleukin motif containing protein 1 (SARM1). NMNAT2, which catalyzes the formation of NAD+ from NMN and ATP, is actively degraded leading to decreased NAD+ levels. SARM1 activity further decreases the concentration of NAD+ by catalyzing its hydrolysis to form nicotinamide and a mixture of ADPR and cADPR. Notably, SARM1 knockout mice show decreased neurodegeneration in animal models of axon degeneration, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting this novel NAD+ hydrolase. This review discusses recent advances in the SARM1 field, including SARM1 structure, regulation, and catalysis as well as the identification of the first SARM1 inhibitors.

Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a coenzyme that is most associated with hydride transfer reactions involved in energy metabolism. However, this coenzyme can also act as a substrate for sirtuins, ADP-ribosyltransferases (ARTs), poly ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs), and NAD+ hydrolases (Fig. 1A).[1–4] Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylases, whereas ARTs and PARPs transfer the ADP-ribose (ADPR) moiety of NAD+ to other proteins. Remarkably, both protein families play important roles in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression.[1–4] By contrast, the NAD+ hydrolases CD38 (cluster of differentiation 38) and SARM1 (sterile alpha and toll interleukin motif containing protein 1), catalyze the breakdown of NAD+ to nicotinamide and either ADPR or cyclic-ADPR (cADPR). Notably, ADPR and cADPR are second messengers that can promote calcium entry into cells by binding to calcium channels.[3,4]

Figure 1. NAD+ metabolism is central to axon degeneration.

A) NAD+ producing and consuming enzymes and their reactions. NMNAT synthesizes NAD+ from NMN and ATP. NAD+ is also synthesized by NAD+ synthase (not depicted). Sirtuins are a family of NAD+ dependent deacetylases that produce O-acetyl-ADPR and nicotinamide using NAD+ and acetylated proteins. CD38 and SARM1 are NAD+ hydrolases/cyclases that produce nicotinamide and a mixture of ADPR and cADPR from NAD+. PARPs are enzymes that transfer the ADPR-moiety of NAD+ to another protein, producing nicotinamide in the process. PARP target proteins can either be mono- or poly-ADP-ribosylated, where the latter can either be linear or branched. B) NAD+(P) catalysis by SARM1. SARM1 utilizes both NAD+ and NADP as substrates. In the presence of free pyridine bases, such as nicotinic acid, SARM1 catalyzes the base exchange reaction with NADP to generate NAADP and nicotinamide. When utilizing NAD+ as a substrate, SARM1 cleaves NAD+ to generate nicotinamide, ADPR and cADPR; the ADPR:cADPR ratio is approximately 9:1 in the absence of free bases. Catalysis occurs through either an oxocarbenium or covalent intermediate.

Dysregulated NAD+ metabolism is associated with several disease states, including cancer, infection, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disease.[1–4] In particular, NAD+ metabolism is central to the pathophysiology of axon degeneration, a hallmark feature of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, peripheral neuropathies, and traumatic brain injury. During axon degeneration, NAD+ levels are largely controlled by two enzymes: nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 (NMNAT2) and SARM1 (Fig. 1A).[5,6] NMNAT2 is a biosynthetic enzyme that synthesizes NAD+ from NMN and ATP.[5] Under normal physiological conditions, NMNAT2 is delivered to the axon by anterograde transport, where it contributes to the axoplasmic pool of NAD+ (Fig. 2A). Under conditions of stress or injury, the microtubules used to transport this protein are damaged and NMNAT2 is no longer delivered to the axon. Consequently, NAD+ levels decrease and NMN levels begin to increase.[6] These altered NMN and NAD+ levels are thought to activate SARM1.[7] Calcium influx, triggered by ADPR and/or cADPR, then activates calpains which proteolyze the microtubules and neurofilaments that constitute the axonal cytoskeleton. This signaling cascade, coupled with the energetic crisis associated with decreased NAD+ levels, ultimately causes axon degeneration.[6] The opposing roles of NMNAT2 and SARM1 in this pathway highlight the central importance of NAD+ metabolism in axon degeneration and emphasize SARM1 activation as a crucial step in the pathophysiology of axon degeneration.

Figure 2. SARM1 and its hydrolase activity are involved in diverse cellular processes.

A) Model for SARM1 activity in axon degeneration. As NMNAT2 levels fall, NMN levels increase concomitantly with decreases in NAD+ levels. Changes in the concentrations of these metabolites activate SARM1. Activation correlates with a phase transition to a higher ordered oligomer. NAD+ levels decrease further as SARM1 cleaves NAD+ to nicotinamide, ADPR, and cADPR. The generation of (c)ADPR triggers calcium influx, which in turn activates calpains. The axonal cytoskeleton is subsequently degraded by calpains, resulting in the characteristic axonal fragmentation of Wallerian-like degeneration. B) Model for SARM1 activity in intestinal immunity. Under conditions of low cholesterol, TIR-1/SARM1 undergoes a phase transition that results in the activation of the p38/PMK-1 MAPK pathway and the expression of immune response genes. Activation of this pathway when environmental sterols are scarce, “preactivates” the immune response so the C. elegans may respond more effectively to pathogens.

SARM1 structure and function

SARM1 was first identified as a negative regulator of innate immune signaling.[8] However, a later Drosophila screen for mutants that displayed prolonged axonal survival after axotomy showed that SARM1 has a prodegenerative role.[9] Follow up work with mouse models of traumatic brain injury found that SARM1 knockout mice were protected from axonal damage and elevated production of β-amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) in neurons.[10] Subsequent studies show that SARM1 knockout is protective in models of glaucoma, Alzheimer’s disease, ALS, peripheral neuropathies, and traumatic axonal injury.[11–17] Taken together, these data suggest that SARM1 inhibitors could broadly prevent axon degeneration that is associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, SARM1 is an interesting therapeutic target.

SARM1 is a multidomain enzyme containing an autoinhibitory ARM domain, SAM domains that mediate multimerization, and a catalytic TIR domain. [18,19] Early studies on truncated forms of SARM1 showed that deletion of the ARM domain yielded a constitutively active form of the enzyme and that SARM1 activity could only be observed when TIR domains are close, either by rapamycin-induced forced dimerization or by conducting kinetic assays on beads.[18–22] While these initial experiments elucidated the functional roles of each SARM1 domain, questions remained regarding the activation mechanism of SARM1.

Some clarity on SARM1 regulation has been provided by recent structural studies. Initial structures of the full-length enzyme determined by cryoEM revealed that the SAM domains form an octameric core and the ARM domains radiate out from the central ring (Fig. 3A).[23–26] The TIR domains are separated by the ARM domains and do not contact each other, suggesting the enzyme is in an inactive conformation.[24–26]

Figure 3. NAD+ and NMN bind the allosteric binding pocket in the SARM1 ARM domain.

A) SARM1 octamer in the inactive conformation. Orange: ARM domain, green: tandem SAM domains, purple: TIR domain (PDB:7LD0). The allosteric binding site is highlighted in black. B) NAD+ (cyan) bound to the allosteric binding pocket of the ARM domain of human SARM1 (PDB:7CM6). C) NMN (teal) bound to the allosteric binding pocked of the ARM domain of dSARM (PDB:7LCZ). D) TIR domain dimer in the active conformation complexed with IAD (yellow; PDB:7NAK).

To determine the structure of the active enzyme, cryo-EM was performed on SARM1 in the presence of NAD+. However, close inspection of the cryo-EM maps showed there was no NAD+ density in the active site. Instead, NAD+ binds the ARM domain at an allosteric site in this structure.[24,25] The allosteric NAD+ binding site in the ARM domain involves W103 π-stacking with nicotinamide; R110, R157, and K193 forming salt bridges with the pyrophosphate; and R110 hydrogen bonding with adenosine (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, mutation of residues responsible for binding the nicotinamide moiety (e.g., the W103A, Q150A, and H190A triple mutant) enhance NAD+ binding to the ARM domain by ~2-fold and decrease the prodegenerative capacity of SARM1.[25] Likewise, the W103A or W103F single mutants are unable to execute cell death or axon degeneration.[7,24] By contrast, the ARM domain triple mutant R110E, R157E, and K193E has a 6-fold decreased affinity for NAD+ and neuronal expression of this triple mutant leads to a 10-fold increase in NAD+ hydrolase activity and axon degeneration in the absence of injury.[25] Together these data emphasize the importance of the electrostatic interactions in NAD+ binding the ARM domain and suggest that NAD+ allosterically inhibits the enzyme. Indeed, NAD+ dose response experiments revealed that NAD+ hydrolase activity is impaired at NAD+ concentrations greater than 250 μM, supporting the hypothesis that NAD+ inhibits full-length SARM1 by binding to this allosteric site.[25,27]

Remarkably, NMN competes with NAD+ for binding this site.[21,26,27] The binding affinity of NAD+ for the allosteric site decreases linearly with NMN concentration such that there is a ~four-fold decrease in the binding affinity at 50 μM versus 0 μM.[27] Subsequent structural studies with the ARM domain, from both human SARM1 and Drosophila SARM1 (dSARM), confirmed that NMN binds the ARM domain.[7,28] W103 π-stacks with the pyridine ring on NMN, Q150 interacts with the 2’-hydroxyl, and R110, R157 and K193 form salt bridges with the phosphate of NMN (Fig. 3C).[7,28] Mutations in the NMN-binding pocket also decrease SARM1 activity in vitro and strongly prevent NMN-dependent and injury-induced axon degeneration.[7,28] Moreover, comparison of the NMN-bound dSARM ARM domain with ligand-free human SARM1 ARM domain show that the ARM domain adopts a more compact conformation upon NMN binding.[7] In the cryo-EM structure of NMN-bound human ARM-SAM, the ARM domain compacts, rotates 22°, and shifts upward 19 Å relative to the SAM domains. The ARM domain subsequently interferes with the TIR domains and encourages TIR domain assembly into an active conformation.[28] Notably, the conformation of the SAM domain is the same in both the inactive and active structures.[28] Therefore, conformational changes in the ARM domain triggered by NMN binding do not propagate throughout the enzyme per se, but rather cause steric clashes that activate the enzyme.

Systematic evaluation of the effect of NMN and NAD+ concentration on SARM1 activity found that increases in the NMN/NAD+ ratio trigger the activation of SARM1. Notably, only NMN/NAD+ ratio increases greater than 10-fold activate SARM1 NAD+ hydrolase activity, whereas smaller-fold increases did not.[7] At baseline, SARM1 has a Km of 30.3 μM and a kcat of 0.030 s−1 for a kcat/Km of 1000 M−1s−1 with respect to NAD+. In the presence of NMN, the Vmax of the hydrolysis reaction increases from 22.4 to 161 mU/mg, approximately 7-fold, indicating the enzyme is more active in the presence of NMN. These data are consistent with the kinetic parameters of constitutively active SARM1 (ΔARM), which has a Km of 69.5 μM and a kcat of 0.448 s−1 for a kcat/Km of 6500 M−1s−1 with respect to NAD+. Notably, the Ki of NAD+ at the allosteric site is approximately 300 μM in the absence of NMN and the Ki increases with increasing NMN concentration.[27] Given that the concentration of NAD+ in the brain is estimated to be 300 μM and that NAD+ levels are falling concomitantly with increasing NMN levels,[29] the proposed NAD+ mediated inhibition model may not be physiologically relevant. Moreover, the physiological NMN levels are approximately 6 μM,[29] far below the concentration needed to increase SARM1 activity and it remains unclear how much NMN levels increase under pathological conditions. Nevertheless, these structural and mechanistic data on the effects of the NMN/NAD+ ratio on SARM1 activation suggest an activation model where SARM1 is held in an inactive state by NAD+ binding to the ARM domain. Upon injury, NMNAT2 levels decrease, NAD+ levels fall, and NAD+ dissociates from the ARM domain for SARM1 to NAD+ execute catalysis. When the NMN/NAD+ ratio increases greater than 10-fold, NMN can bind the ARM domain to potentiate the SARM1 response (Fig. 2A).

In the structures described above, SARM1 either adopts an inactive state in which the TIR domains are held apart by intervening ARM domains or the enzyme is active, but electron density for the TIR domains is quite poor and the specific conformation the TIR domains adopt is unclear. Recently, structures of active SARM1 were published, specifically of SAM-TIR complexed with the inhibitor 5’-iodoisoquinoline adenine dinucleotide (1AD) (Fig. 3D).[28] When active, the TIR domains adopt a curved, antiparallel linear assembly above the octameric core of the enzyme, with 13° tilts in each TIR domain. The active site spans a TIR domain dimer formed by the interaction of the BB loop on one TIR domain with the EE loop on the other (Fig. 3D). 1AD binding to the active site is stabilized by a π-stacking interaction between the 5-iodoisoquinoline moiety and both F603 and W638; hydrogen bonding interactions between the 2’-hydroxyl of the ribose moiety and E642; a salt bridge between the phosphate and R569; π-stacking of the adenine base with W662; and a halogen bond between the iodine and W679 (Fig. 3D). Except for the pyridine base, the binding mode of similar inhibitors is identical. Mutations in the TIR domain oligomerization interface (i.e., H685 and Y687) abolish NAD+ hydrolase and base exchange activities. By contrast, active site mutations have differing effects on NAD+ hydrolase activity and base exchange activity with respect to 5-iodoisoquinoline; F603A and W638A mutants exhibit decreased NAD+ hydrolase activity and base exchange activity; N679A shows decreased NAD+ hydrolase activity, but normal base exchange activity; and W662A has no effect on either activity.[28] These results suggest that F603, W638, and N679 are important for binding the pyridine base and that W662 is dispensable for substrate binding when adenine is the purine base. Notably, it is unclear from these structures how cADPR would be formed; nicotinamide is released first (see below) and then the adenosine moiety must be able to flip in and react with the intermediate.

In phase separations, biomolecules segregate into dense, high concentration compartments and dilute, low concentration compartments, where the high concentration phase will have either liquid-like or gel/solid-like characteristics. When the high concentration phase has solid-like properties, the molecules that constitute the dense phase are said to have undergone a phase transition. Loring et al. (2021) found that the molecular crowding agent PEG 3350 and precipitant sodium citrate cause SARM1 to undergo a phase transition that activates the enzyme by over 1000-fold.[30] Negative stain EM of the human TIR domain in the presence of citrate revealed enhanced puncta formation.[30,31] These puncta adopt a ring-like conformation whose sizes are greater than or equal to two octamers.[30] These findings were recapitulated in vivo, where TIR-1 (the C. elegans ortholog of full-length SARM1) puncta increased in size following C. elegans citrate treatment and these citrate-treated animals showed increased axon degeneration.[30] In total, these in vitro and in vivo data indicate that citrate triggers the phase transition of SARM1/TIR-1 such that the precipitation and corresponding enzymatic activity increase, leading to a model wherein SARM1/TIR-1 aggregates in vivo to execute axon degeneration (Fig. 2A). Recently, a similar activation and aggregation mechanism was reported in the context of intestinal immunity.[31] Here, the TIR domain from TIR-1 undergoes a phase transition that activates the enzyme 30-fold. During pathogen infection or low cholesterol conditions, TIR-1 forms puncta in intestinal epithelial cells, which subsequently activates the p38 PMK-1 immune pathway. When pathogen infection and cholesterol scarcity are considered together, p38 PMK-1 pathway activation by pathogen infection potentiates activation of this pathway caused by the lack of cholesterol (Fig. 2B).[31] Intriguingly, 2D class averaging of active SAM-TIR showed TIR domain assemblies consisting of >8 TIR domains. Analytical size exclusion chromatography also showed the formation of higher order oligomers.[28] Despite the increased stability of the TIR domain oligomer due to 1AD binding, these structural and biochemical data are consistent with the aggregation/phase transition model of SARM1 activity.

Mechanistically, this phase transition dramatically increases activity through changes in turnover number (kcat). For SARM1, kcat increases nearly linearly with increasing PEG or citrate concentration and the catalytic efficiency follows the trends in turnover number.[30] TIR-1 displayed similar behavior, where kcat increases sigmoidally and the catalytic efficiency follows kcat trends.[31] In 25% PEG 3350, the catalytic efficiency increases >1000-fold for SARM1 and ≥50-fold for TIR-1.[30,31] Moreover, TIR domain precipitation correlates with catalytic efficiency.[31] A longer version of TIR-1, containing the SAM domains and the TIR domain, also undergoes a phase transition that increases activity.[30] However, the fold-activation is less than that with the isolated TIR domain.[30] These data indicate that preorganization of the TIR domains by SAM octamerization decreases the effect of the phase transition on SARM1 activity. Moreover, it remains unknown whether endogenous citrate levels are dysregulated in axon degeneration. While the physiological relevance of citrate-induced phase transition and activation of SARM1/TIR-1 remains to be determined, the data nevertheless indicate that citrate induces a phase transition that precipitates/aggregates the enzyme to potentiate SARM-1/TIR-1 activity both in vitro and in vivo. Given that both SARM1 and TIR-1 undergo a phase transition in vivo shows that the phase transition is an additional regulatory mechanism conserved across evolution and in different cell types and cellular processes.

SARM1 is not just an NAD+ hydrolase

SARM1 was first described as an NAD+ hydrolase and cyclase (Fig. 1B),[19] but SARM1 can also catalyze cADPR hydrolysis, NADP hydrolysis, and base exchange reactions.[21,27,30,32] In the base exchange reaction, SARM1 exchanges the nicotinamide moiety on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) for nicotinic acid (NA) to produce nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP).[21] Like ADPR and cADPR, NAADP opens calcium channels that could contribute to the calcium influx step of axon degeneration, in this case from lysosomal stores.[33–37]

SARM1 catalyzed NAD+ hydrolysis proceeds via an ordered uni-bi kinetic mechanism where nicotinamide is released before (c)ADPR.[22] Since nicotinamide is released first, catalysis occurs by the formation of either an oxocarbenium or covalent intermediate, and it is likely that the intermediate is common to all SARM1 reactions (Fig. 1B). In the presence of NA, the nitrogen in the pyridine ring can act as a nucleophile to attack the intermediate and generate the base exchange product. Other pyridine-containing molecules (e.g., vacor, 3-acetyl pyridine) can also participate in this base exchange reaction.[27] Notably, in a crystal structure of the human TIR domain in complex with ara-F-NAD, a covalent bond was observed between the anomeric carbon of ara-F-NAD and the E642 carboxylate, providing evidence for covalent catalysis.[28] However, the formation of this covalent bond may be an artifact of the long crystallization conditions as in our hands ara-F-NAD is not a potent SARM1 inhibitor.[30] In fact, ara-F-NAD+ covalently modifies CD38 even though the oxocarbenium ion intermediate is the favored route of catalysis. [38,39] Therefore, a mechanism in which an oxocarbenium is stabilized by the E642 carboxylate should not be excluded.

Preliminary studies show that the base exchange activity of SARM1 does not change upon activation by NMN at neutral pH, but increases when SARM1 is preactivated by treatment with acid at pH 3–4.[21,40] Acid pretreatment likely acts globally on SARM1 to relieve autoinhibition and posits another potential regulatory mechanism for SARM1.[40] By contrast, recent studies showed that the base exchange reaction is catalyzed by SARM1 at neutral pH and in neurons. Base exchange substrates include 3-acetyl pyridine, vacor, and NA. The partitioning of base exchange, hydrolysis, and cyclization reactions depends on the identity of the free base; with 3-acetyl pyridine, the base exchange reaction dominates, but the hydrolysis reaction dominates with NA. In the presence of NA, the base exchange and cyclization products make up less than 10% of the products. Moreover, the production of 3-acetyl pyridine adenine dinucleotide (apAD) is observed in wild-type neurons but not in SARM1 knockout neurons.[27] While the apAD is not a physiologically relevant base exchange product, these data suggest that SARM1 can catalyze the base exchange in neurons.

SARM1 Inhibitors

Deletion of SARM1 in the context of traumatic brain injury and axotomy is protective against degeneration, and due to its prodegenerative role in many neurodegenerative diseases, SARM1 is an attractive therapeutic target. To this end, pharmacological inhibition of SARM1 is a growing research area. Nicotinamide, a product of the hydrolysis reaction, was the first inhibitor identified for SARM1.[19] Since then, a number of high throughput screens identified additional SARM1 inhibitors including zinc chloride, berberine chloride, isoquinolines, isothiazoles, and dehydronitrosonisodipine (dHNN).[30,32,41–43] Nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN), an NAD+ precursor, was also found to inhibit SARM1.[44] [41] Known SARM1 inhibitors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. SARMi Inhibitors.

Structures of known SARMi inhibitors and their IC50S.

| Inhibitor | Structure | Details | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotinamide |

|

43.8 | |

| NaMN |

|

Binds the same allosteric site in the ARM domain as NAD* and NMN | 93 |

| Zinc chloride |

|

Allosteric; binds TIR domain | 10 |

| Berberine chloride |

|

Allosteric; binds TIR domain | 140 |

| dHNN |

|

Irreversible; allosteric; binds ARM domain | 4 |

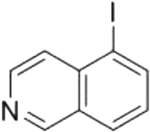

| Isoquinoline |

|

Reversible | 10 |

| 5-iodoisoquinoline |

|

Reversible | 0.075 |

| Isothiazole compound 1 |

|

Irreversible; cysteine reactive; binds TIR domain | 4 |

| Isothiazole compound 10 |

|

Irreversible; cysteine reactive; binds TIR domain; orally bioavailable | 0.23 |

| ara-F-NAD |

|

Orthosteric; covalent | No inhibition |

Of the SARM1 inhibitors listed above, nicotinamide, NaMN, zinc chloride, berberine chloride, and dHNN inhibit SARM1 with potencies in the micromolar range. The inhibitory effect of NaMN is eliminated upon deletion of the ARM domain and the potency of NaMN is decreased nearly two-fold in the presence of NMN, indicating that NaMN binds the same allosteric binding site in the ARM domain that also binds NAD+ and NMN.[44] The first reported high throughput screen for SARM1 inhibitors utilized FDA-approved compounds and identified zinc chloride and berberine chloride as drug candidates for further development. These compounds inhibit the TIR domain of human SARM1, and both show noncompetitive inhibition patterns, suggesting they bind another regulatory site.[41] dHNN is a SARM1 inhibitor that binds the ARM domain to mediate its inhibitory effect. Wash out experiments revealed that dHNN is an irreversible inhibitor. More specifically, the nitroso group covalently modifies multiple cysteine residues. C311 was suggested as one site of modification. However, mutagenesis at this site causes only a two-fold increase in the IC50 of dHNN, suggesting that inhibition is due to the modification of additional cysteine residues in SARM1.[32]

In contrast to the inhibitors described above, the isoquinilines initially showed micromolar potencies, but structure activity relationship (SAR) studies improved their potencies to the nanomolar range. Isoquinoline itself is a reversible SARM1 inhibitor. Substituents at position 5 of isoquinoline improve potency, with the iodo-substituent improving potency over 100-fold. Notably, 5-iodoisoquinoline acts as a substrate in the base exchange reaction to generate 5-iodoisoquinoline adenine dinucleotide (see above). Although the authors classified this inhibitor as a prodrug,[28] we believe that it is more accurate to describe 5-iodoisoquinoline as a mechanism-based inhibitor because the inhibition mechanism is similar to that of finasteride, a known mechanism-based inhibitor; finasteride reacts with NADP to make an inhibitory compound that remains bound to steroid 5α-reductase.[45] By contrast, prodrugs are typically activated by an enzyme that is distinct from the drug target.

Treatment of neurons with 5-iodoisoquinoline prevents cADPR production and axon degeneration following axotomy to a similar degree as SARM1 knockout. Moreover, 5-iodoisoquinoline treatment in damaged axons not yet committed to degeneration allows the axons to return to a healthy morphology. Notably, this neuron population was created by time-specific removal of the mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitor rotenone.[42] The reversal of axonal damage by 5-iodoisoquinoline administration creates the concept of a critical treatment window where axon damage can be reversed instead of delayed, provided the axon is still attached to its cell body.

Isothiazoles were identified in a separate high throughput screen as inhibitors of SARM1.[43] SAR studies showed that ortho-substitution of the hit compound (Compound 1) improved potency roughly 10-fold and further alkylation of the isothiazole skeleton improved potency another two-fold (Compound 10). Wash out experiments showed no changes in the potency of compound 10 and the C635A mutant was much less responsive to the inhibitor compared to WT enzyme or the C649A mutant. Together, these data suggest that compound 10 is an irreversible inhibitor of SARM1. Notably, the isothiazole series can be converted to activity-based probes due to their irreversible nature. Moreover, compound 10 is the first orally bioavailable, submicromolar SARM1 inhibitor identified to date, which enables in vivo studies of SARM1 inhibition. In fact, administration of compound 10 protects against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy to at least the level afforded by SARM1 heterozygosity.[43]

Conclusions and Future Directions

In conclusion, numerous advancements have been made regarding the regulatory mechanisms, enzymatic characterization, and pharmacological inhibition of SARM1. Increases in the NMN/NAD+ ratio activate SARM1. Additionally, SARM1 is more than an NAD+ hydrolase; it also hydrolyzes NADP and catalyzes the base exchange reaction with NADP and NA to make NAADP. Finally, pharmacological inhibition of SARM1 partially protects against degeneration in a model of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

However, significant questions remain. First, are NAD+ and NMN concentrations high enough to regulate SARM1? This question arises because the concentration of NAD+ in the brain is estimated to be only 300 μM,[29] which is similar to the Ki for NAD+.[27] Moreover, NMN concentrations are only ~ 6 μM,[29] which is significantly below the concentrations typically used to activate SARM1. Second, does the NMN/NAD+ ratio increase enough to activate SARM1 in physiologically relevant contexts? Changes in the NMN/NAD+ ratio after axotomy or in disease conditions have yet to be evaluated. Third, do other NAD+ metabolites contribute to SARM1 regulation? Product inhibition by nicotinamide has long been established and NaMN was recently identified as a SARM1 inhibitor.[19,44] While the discovery of NaMN as an allosteric inhibitor poses interesting questions about the breadth of SARM1 regulation by NAD+ metabolites, SARM1 inhibition by NaMN remains to be observed in disease contexts. Further characterization of NAD+ metabolites as SARM1 regulators will need to be validated both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, it is unclear why compound 10 only protects against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy to the level afforded by SARM1 heterozygosity. Does SARM1 possess a scaffolding function? Answers to these questions will do much to elucidate SARM1 regulation and provide additional context for this mechanism of axon degeneration.

Acknowledgments

PRT and JDI are funded by the NIH (PRT: R35 GM118112, JDI: F31 NS122423 and T32 AI132152) and the Dan and Diane Riccio Fund for Neuroscience. Figure 2 was created with BioRender.com.

References

- 1.Loring HS, Thompson PR: Emergence of SARM1 as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Wallerian-type Diseases. Cell Chem Biol 2020, 27:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantó C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J: NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: A balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metab 2015, 22:31–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lautrup S, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, Fang EF: NAD+ in brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Metab 2019, 30:630–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsyuba E, Romani M, Hofer D, Auwerx J: NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat Metab 2020, 2:9–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins EL, Gu W, Kobe B, Coleman MP: A novel NAD signaling mechanism in axon degeneration and its relationship to innate immunity. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8:Article 703532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman MP, Höke A: Programmed axon degeneration: From mouse to mechanism to medicine. Nat Rev Neuro 2020, 21:183–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **7. Figley MD, Gu W, Nanson JD, Shi Y, Sasaki Y, Cunnea K, Malde AK, Jia X, Luo Z, Saikot FK, et al. : SARM1 is a metabolic sensor activated by an increased NMN/NAD+ ratio to trigger axon degeneration. Neuron 2021, 109:1–19. Here, the authors found that increasing the NMN/NAD+ ratio in neurons activates SARM1 and that NMN and NAD+ compete for the allosteric binding site in the ARM domain. This is the first paper that sytematically evaluated how the NMN/NAD+ ratio regulates SARM1.

- 8.Carty M, Goodbody R, Schröder M, Stack J, Moynagh PN, Bowie AG: The human adaptor SARM negatively regulates adaptor protein TRIF-dependent Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Immun 2006, 7:1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, Sheehan AE, Avery MA, Hackett R, Logan MA, et al. : dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science 2012, 337:481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henninger N, Bouley J, Sikoglu EM, An J, Moore CM, King JA, Bowser R, Freeman MR, Brown RH: Attenuated traumatic axonal injury and improved functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in mice lacking Sarm1. Brain 2016, 139:1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko KW, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A: SARM1 acts downstream of neuroinflammatory and necroptotic signaling to induce axon degeneration. J Cell Biol 2020, 219:e201912047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes KA, Mitchell KL, Patel A, Marola OJ, Shrager P, Zack DJ, Libby RT, Welsbie DS: Role of SARM1 and DR6 in retinal ganglion cell axonal and somal degeneration following axonal injury. Exp Eye Res 2018, 171:54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom AJ, Mao X, Strickland A, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A: Constitutively active SARM1 variants that induce neuropathy are enriched in ALS patients. Mol Neurodegener 2022, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng Y, Liu J, Luan Y, Liu Z, Lai H, Zhong W, Yang Y, Yu H, Feng N, Wang H, et al. : SARM1 gene deficiency attenuates diabetic peripheral neuropathy in mice. Diabetes 2019, 68:2120–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A: Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain 2016, 139:3092–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilley J, Jackson O, Pipis M, Estiar MA, Al-Chalabi A, Danzi MC, van Eijk KR, Goutman SA, Harms MB, Houlden H, et al. : Enrichment of SARM1 alleles encoding variants with constitutively hyperactive NADase in patients with ALS and other motor nerve disorders. eLife 2021, 10:e.70905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynard ME, Redell JB, Zhao J, Hood KN, Vita SM, Kobori N, Dash PK: Sarm1 loss reduces axonal damage and improves cognitive outcome after repetitive mild closed head injury. Exp Neuro 2020, 327:113207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerdts J, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J: Sarm1-mediated axon degeneration requires both SAM and TIR interactions. J Neurosci 2013, 33:13569–13580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J: The SARM1 Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor Domain Possesses Intrinsic NAD+ Cleavage Activity that Promotes Pathological Axonal Degeneration. Neuron 2017, 93:1334–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerdts J, Brace EJ, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J: SARM1 activation triggers axon degeneration locally via NAD(+) destruction. Science 2015, 348:453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao ZY, Xie XJ, Li WH, Liu J, Chen Z, Zhang B, Li T, Li SL, Lu JG, Zhang L, et al. : A Cell-Permeant Mimetic of NMN Activates SARM1 to Produce Cyclic ADP-Ribose and Induce Non-apoptotic Cell Death. iScience 2019, 15:452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loring HS, Icso JD, Nemmara V, Thompson PR: Initial Kinetic Characterization of Sterile Alpha and Toll/Interleukin Receptor Motif-Containing Protein 1. Biochemistry 2020, 59:933–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sporny M, Guez-Haddad J, Lebendiker M, Ulisse V, Volf A, Mim C, Isupov MN, Opatowsky Y: Structural Evidence for an Octameric Ring Arrangement of SARM1. J Mol Biol 2019, 431:3591–3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24. Sporny M, Guez-Haddad J, Khazma T, Yaron A, Dessau M, Shkolnisky Y, Mim C, Isupov MN, Zalk R, Hons M, et al. : Structural basis for SARM1 inhibition and activation under energetic stress. eLife 2020, 9:e62021. This paper solves the structure of SARM1 with and without NAD+ bound to the allosteric site and shows that NAD+ binding induces a stable organization of the ARM and TIR domains around the central octamer. These data support the NAD+ inhibition model of SARM1 regulation.

- **25. Jiang Y, Liu T, Lee CH, Chang Q, Yang J, Zhang Z: The NAD+-mediated self-inhibition mechanism of pro-neurodegenerative SARM1. Nature 2020, 588:658–663. Using cryo-EM, these authors solve the full-length structure of SARM1 and describe an allosteric binding pocket in the ARM domain that binds NAD+. Moreover, this paper presents non-traditional substrate inhibition of SARM1 by NAD+ to elucidate SARM1 reuglation.

- *26. Bratkowski M, Xie T, Thayer DA, Brown SP, Bai X, Correspondence SS, Lad S, Mathur P, Yang Y-S, Danko G, et al. : Structural and Mechanistic Regulation of the Pro-degenerative NAD Hydrolase SARM1. Cell Rep 2020, 32:107999. Two SARM1 structures were solved in this paper. One adopts an inactive conformation in which the TIR domains are separated from each other by intervening ARM domains. The other is of the SAMs and TIR domains, but this structure was solved at low resolution. The first near-full length human SARM1 structure was solved in this paper.

- **27. Angeletti C, Amici A, Gilley J, Loreto A, Trapanotto AG, Antoniou C, Merlini E, Coleman MP, Orsomando G: SARM1 is a multi-functional NAD(P)ase with prominent base exchange activity, all regulated bymultiple physiologically relevant NAD metabolites. iScience 2022, 25:103812. Using primarily biochemical methods, these authors show that SARM1 catalyzes NADP hydrolysis in addition to NAD+ hydrolysis and that SARM1 catalyzes the base exchange reaaction with NADP and NA at neutral pH. Furthermore, they demonstrate that the base exchange reaction can occur in neurons ex vivo. This is the first time that SARM1-dependent base exchange has been observed in neurons.

- **28. Shi Y, Kerry PS, Nanson JD, Bosanac T, Sasaki Y, Krauss R, Saikot FK, Adams SE, Mosaiab T, Masic V, et al. : Structural basis of SARM1 activation, substrate recognition, and inhibition by small molecules. Mol Cell 2022, 82:1–17. Using cryo-EM, these authors solve the first structure of active SARM1. The active site spans two TIR domains and the TIR domains adopt curved, antiparallel linear assemblies in their active conformation. Notably, assemblies consisting of more than eight SARM1 units were observed under the experimental conditions reported in this paper.

- 29.Mori V, Amici A, Mazzola F, Di Stefano M, Conforti L, Magni G, Ruggieri S, Raffaelli N, Orsomando G: Metabolic Profiling of Alternative NAD Biosynthetic Routes in Mouse Tissues. PLOS ONE 2014, 9:e113939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **30. Loring HS, Czech VL, Icso JD, O’Connor L, Parelkar SS, Byrne AB, Thompson PR: A phase transition enhances the catalytic activity of SARM1, an NAD+ glycohydrolase involved in neurodegeneration. eLife 2021, 10:e.66694. Here, the authors use molecular crowding agents and precipitants to show that the TIR domain of human SARM1 undergoes a phase transition that activates the enzyme >1000-fold. These findings were recapitulated in vivo where citrate-treated animals displayed increased TIR-1/SARM1 puncta formation and TIR-1/SARM1-dependent axon degeneration. This paper highlights an additional SARM1 regulatory mechanism.

- **31. Peterson ND, Icso JD, Salisbury JE, Rodríguez T, Thompson PR, Pukkila-Worley R: Pathogen infection and cholesterol deficiency activate the C. elegans p38 immune pathway through a TIR-1/SARM1 phase transition. eLife 2022, 11:e74206. Using similar techniques as in Loring et al. (2021), these authors show that TIR-1 undergoes a similar phase transition to activate the enzyme. Under conditions of low cholesterol and pathogen infection, TIR-1 punta are observed in vivo and lead to activation in the p38 PMK-1 immune pathway. These data emphasize the conserved nature of the SARM1/TIR-1 phase transition, not just across evolution, but also in a variety of physiological contexts.

- 32.Li WH, Huang K, Cai Y, Wang QW, Zhu WJ, Hou YN, Wang S, Cao S, Zhao ZY, Xie XJ, et al. : Permeant fluorescent probes visualize the activation of SARM1 and uncover an anti-neurodegenerative drug candidate. eLife 2021, 10:e67381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fliegert R, Gasser A, Guse AH: Regulation of calcium signalling by adenine-based second messengers. Biochem Soc Trans 2007, 35:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.George EB, Glass JD, Griffin JW: Axotomy-Induced Axonal Degeneration Is Mediated by Calcium Influx Through Ion-Specific Channels. J Neurosci 1995, 15:6445–6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villegas R, Martinez NW, Lillo J, Pihan P, Hernandez D, Twiss JL, Court FA: Calcium release from intra-axonal endoplasmic reticulum leads to axon degeneration through mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci 2014, 34:7179–7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, Hao X, Tang J, Rietdorf K, Teboul L, Chuang KT, et al. : NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature 2009, 459:596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel S, Marchant JS, Brailoiu E: Two-pore channels: Regulation by NAADP and customized roles in triggering calcium signals. Cell Calcium 2010, 47:480–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Q, Kriksunov IA, Jiang H, Graeff R, Lin H, Lee HC, Hao Q: Covalent and noncovalent intermediates of an NAD utilizing enzyme, human CD38. Chem Biol 2008, 15:1068–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zechel DL, Withers SG: Glycosidase mechanisms: anatomy of a finely tuned catalyst. Acc Chem Res 2000, 33:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao YJ, He WM, Zhao ZY, Li WH, Wang QW, Hou YN, Tan Y, Zhang D: Acidic pH irreversibly activates the signaling enzyme SARM1. FEBS J 2021, 288:6783–6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *41. Loring HS, Parelkar SS, Mondal S, Thompson PR: Identification of the first noncompetitive SARM1 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 2020, 28:115644. High throughput screening identified the first noncompetitive inhibitiors of the SARM1 TIR domain. These results indicate the existence of another allosteric site in the TIR domain that can be targeted for further drug development.

- *42. Hughes RO, Bosanac T, Mao X, Engber TM, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J, Devraj R, Krauss R: Small Molecule SARM1 Inhibitors Recapitulate the SARM1−/− Phenotype and Allow Recovery of a Metastable Pool of Axons Fated to Degenerate. Cell Rep 2021, 34:108588. Here, the authors created a moderately damaged axonal population that will degenerate without intervention. However, these axons will recover if SARM-1 inhibitors are supplied. Additionally, 5-iodoisoquinoline was identified as a SARM1 inhibitor with nanomolar potency; this was the first inhibitor described with this potency. Overall, these data highlight the importance of inhibiting SARM1 during a period of intermediate axonal damage.

- **43. Bosanac T, Hughes RO, Engber T, Devraj R, Brearley A, Danker K, Young K, Kopatz J, Hermann M, Berthemy A, et al. : Pharmacological SARM1 inhibition protects axon structure and function in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Brain 2021, 144:3226–3238. Using a high throughput screen and SAR studies, an isothiazole series of SARM1 inhibitors are described. Like 5-iodoisoquinoline, these inhibtors were optimized to have a nanomolar potency. Importantly, compound 10 in this series is orally bioavailable, which is the first of its kind.

- 44.Sasaki Y, Zhu J, Shi Y, Gu W, Kobe B, Ve T, Diantonio A, Milbrandt J: Nicotinic acid mononucleotide is an allosteric SARM1 inhibitor promoting axonal protection. Exp Neuro 2021, 345:113842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bull HG, Garcia-Calvo M, Andersson S, Baginsky WF, Chan HK, Ellsworth DE, Miller RR, Stearns RA, Bakshi RK, Rasmusson GH, et al. : Mechanism-Based Inhibition of Human Steroid 5α-Reductase by Finasteride: Enzyme-Catalyzed Formation of NADP−Dihydrofinasteride, a Potent Bisubstrate Analog Inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118:2359–2365. [Google Scholar]