Abstract

Mutations in RNA binding motif protein 20 (RBM20) are a common cause of familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Many RBM20 mutations cluster within an arginine/serine-rich (RS-rich) domain, which mediates nuclear localization. These mutations induce RBM20 mis-localization to form aberrant ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules in the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes and abnormal alternative splicing of cardiac genes, contributing to DCM. We used adenine base editing (ABE) and prime editing (PE) to correct pathogenic p.R634Q and p.R636S mutations in the RS-rich domain in human isogenic induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived cardiomyocytes. Using ABE to correct RBM20R634Q human iPSCs, we achieved 92% efficiency of A-to-G editing, which normalized alternative splicing of cardiac genes, restored nuclear localization of RBM20, and eliminated RNP granule formation. In addition, we developed a PE strategy to correct the RBM20R636S mutation in iPSCs and observed A-to-C editing at 40% efficiency. To evaluate the potential of ABE for DCM treatment, we also created Rbm20R636Q mutant mice. Homozygous (R636Q/R636Q) mice developed severe cardiac dysfunction, heart failure, and premature death. Systemic delivery of ABE components containing ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9 and single-guide RNA by adeno-associated virus serotype 9 in these mice restored cardiac function as assessed by echocardiography and extended life span. As seen by RNA sequencing analysis, ABE correction rescued the cardiac transcriptional profile of treated R636Q/R636Q mice, compared to the abnormal gene expression seen in untreated mice. These findings demonstrate the potential of precise correction of genetic mutations as a promising therapeutic approach for DCM.

INTRODUCTION

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a severe myocardial disease characterized by cardiac enlargement with systolic dysfunction and high susceptibility to sudden cardiac death (1). DCM is one of the most common causes of heart failure in humans with a prevalence of about 1:250 (1, 2). Autosomal dominant mutations in the RNA binding motif protein 20 (RBM20) are a common cause of cardiomyopathy, accounting for 2 to 6% of patients with familial DCM (3–5). Cardiac transplantation at a young age is the only currently effective treatment for this disease (6–8).

RBM20 is a striated muscle–specific splicing factor that regulates alternative splicing of many cardiac genes encoding sarcomere and calcium-regulatory proteins (9–10). Aberrant splicing of cardiac genes, such as titin (TTN), has been postulated as the primary cause of RBM20-associated cardiomyopathy (11). Many RBM20 mutations are located in exon 9, which encodes an arginine/serine-rich (RS-rich) domain (5, 6, 12). The amino acid stretch RSRSP, located from p.R634 to p.P638, contains the nuclear localization signal of RBM20 (10). The RBM20R636S mutation in the RS-rich region induces RBM20 mis-localization and the formation of phase-separated ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules in the cytoplasm (13), implicating aberrant RNP granules in cardiomyocytes (CMs) as a potential cause of DCM (13–17).

Most therapies for DCM address the symptoms of the disease or target secondary effects, whereas the genetic mutations underlying the disease remain unchanged. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technologies, such as base editing (BE) (18–20) and prime editing (PE) (21), offer the potential to correct disease-causing mutations precisely and permanently and provide therapeutic approaches to treat cardiomyopathy (22–24).

In this study, we used BE and PE to precisely correct the RBM20R634Q mutation (c.1901 G>A) and RBM20R636S mutation (c.1906 C>A) in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). In addition, we created a Rbm20R636Q mouse model that recapitulated the human DCM phenotype. Systemic delivery of adenine BE (ABE) components to this DCM mouse model rescued cardiac function and extended life span. Our results highlight the potential of BE and PE-mediated precise gene editing for therapeutic correction of genetic mutations underlying DCM.

RESULTS

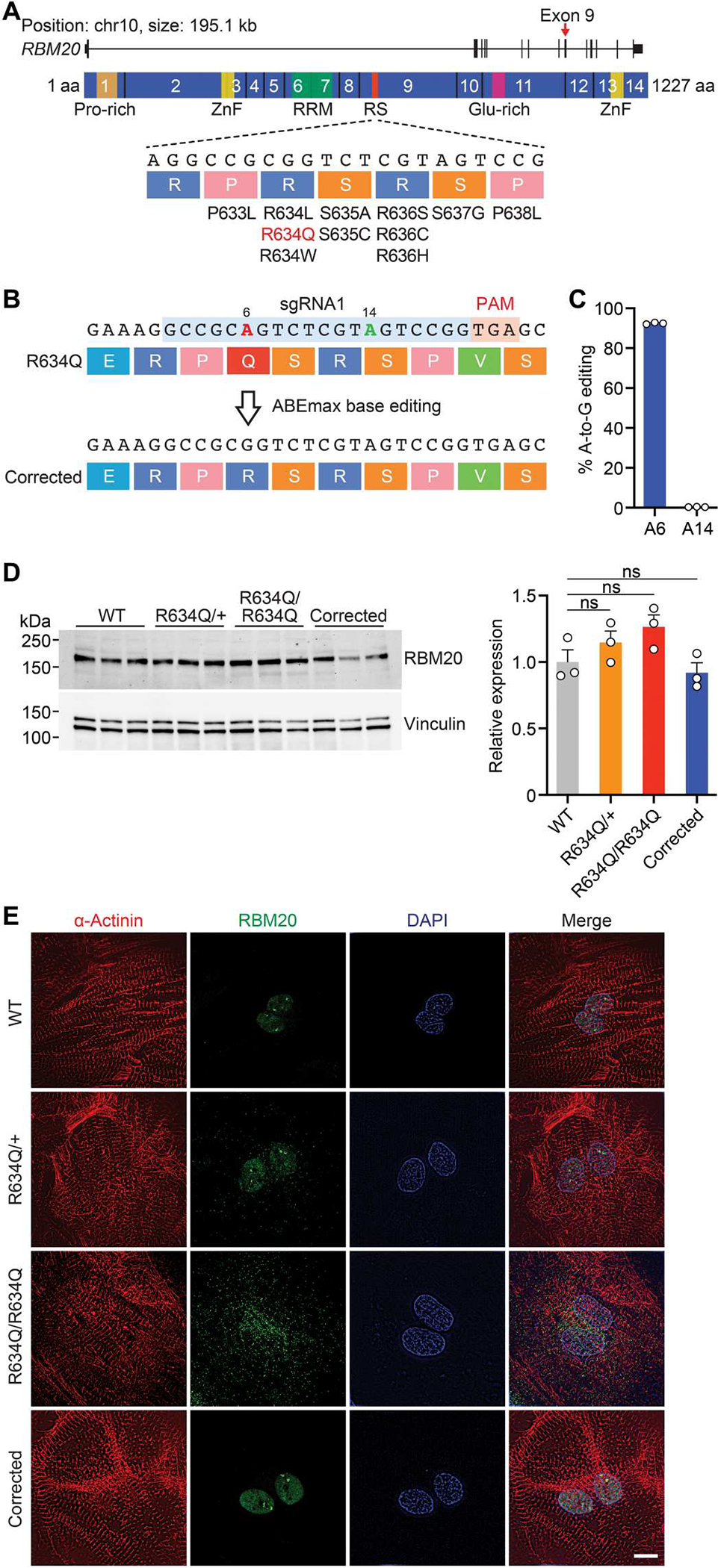

BE in iPSCs with the RBM20R634Q mutation

The RBM20R634Q mutation (c.1901 G>A), located in the RS-rich region, is caused by a transition of guanine to adenine, which is amenable to ABE (18, 19) (Fig. 1, A and B). To test whether ABE could be adapted to precisely correct this mutation, we first generated human isogenic iPSC lines with heterozygous (R634Q/+) and homozygous (R634Q/R634Q) mutations from healthy control iPSCs using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing (fig. S1A). To evaluate the efficiency of ABE, we designed four single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) and tested each sgRNA with ABE8e containing an adenine deaminase, which converts A to G (table S1) (25). We observed potentially detrimental bystander mutations in addition to on target editing and therefore switched the base editor to ABEmax (26), which has a narrower editing window (fig. S1, B to D). The combination of sgRNA1 and ABEmax fused with VRQR-SpCas9, which can recognize an NGA protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (27, 28), showed high efficiency of A-to-G editing at the on-target site (92%) without inducing notable bystander mutations (0.3%) (Fig. 1, B and C). In addition, ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9 editing of the R634Q/+ mutation in iPSCs increased the percentage of the normal RBM20 allele from 50 to 91% (fig. S1E). Therefore, we selected ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9 (hereafter referred to as ABE) for further studies.

Fig. 1. Precise correction of the RBM20R634Q mutation by adenine base editing in iPSCs.

(A) Illustration of RBM20 gene and protein. The 14 exons encoding the protein are indicated. Exon 9, which encodes the arginine/serine-rich (RS-rich) region, contains the human RBM20 gene mutations. Pro-rich, proline-rich region; ZnF, zinc finger domain; RRM, RNA recognition motif; Glu-rich, glutamate-rich region. aa, amino acid. (B) Illustration depicting adenine base editing (ABE) correction of R634Q mutation using sgRNA1 (blue) and ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9. On-target site is positioned at A6 (red), and possible bystander site is at A14 (green). PAM is indicated in pink. (C) Editing efficiency of adenine (A) to guanine (G) determined by deep sequencing in homozygous (R634Q/R634Q) iPSCs after ABE correction. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3). (D) Western blot showing the expression of RBM20 protein in wild-type (WT), heterozygous (R634Q/+), R634Q/R634Q, and ABE-corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC– cardiomyocytes (CMs). Vinculin was used as the loading control. Data of quantification are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ns, not significant. (E) Immunocytochemistry of normal (WT), R634Q/+, R634Q/R634Q, and ABE-corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs. α-Actinin (red), RBM20 (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. Single clones of iPSCs were isolated and differentiated into iPSC-CMs for assays.

In human CMs derived from iPSCs (iPSC-CMs), both mutant and wild-type (WT) RBM20 proteins were expressed at similar abundances (Fig. 1D). However, in healthy iPSC-CMs, RBM20 was localized predominantly to the nucleus (Fig. 1E). In contrast, in R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs, RBM20 was localized to cytoplasmic RNP granules, whereas in R634Q/+ iPSC-CMs, RBM20 was distributed in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. 1E). Using ABE and sgRNA1 to correct the RBM20R634Q mutation, we observed restoration of nuclear localization of RBM20, elimination of pathological RNP granule formation, and normal architecture of sarcomeric structures marked by α-actinin (Fig. 1E).

Previous papers showed that aberrant RBM20R636S granules colocalized with stress granules, marked by G3BP stress granule assembly factor 1 (G3BP1) in iPSC-CMs (13, 15). Similarly, RBM20R634Q granules also colocalized with stress granules in the cytoplasm after acute stress evoked by exposure to sodium arsenite (fig. S2, A to C).

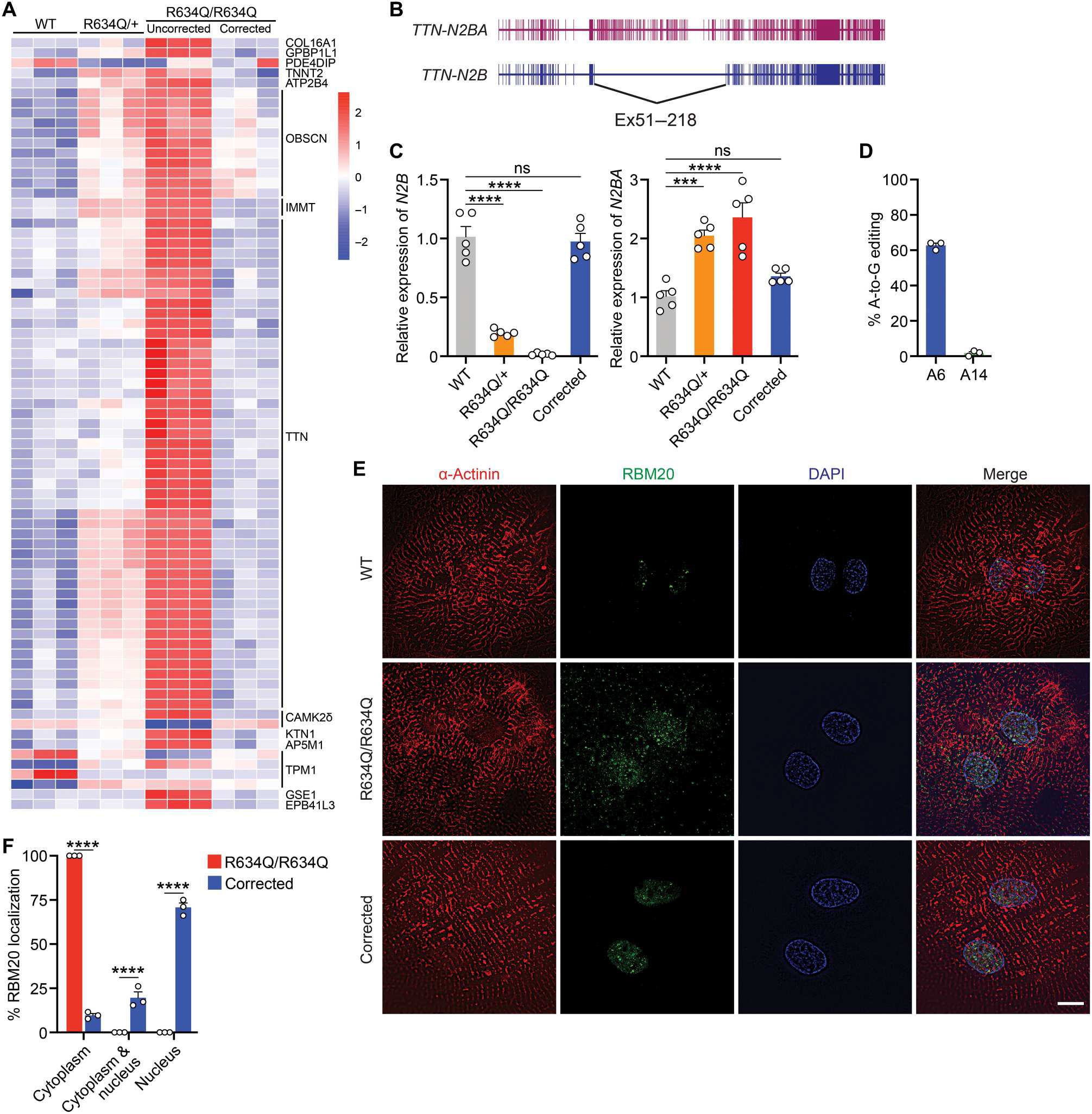

In addition to RNP granule formation, mutations of RBM20 also cause RNA splicing defects. To analyze the alternative splicing of genes regulated by RBM20, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on normal, R634Q/+, R634Q/R634Q, and ABE-corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs. As shown in the heatmap (Fig. 2A), 14 genes showed aberrant splicing patterns in uncorrected CMs, including genes encoding components of the cardiac sarcomere, such as TTN, and calcium signaling proteins, such as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIδ (CAMK2δ). Because TTN mis-splicing represents a major indicator of RBM20-associated DCM, we measured the exon-inclusion ratio by percent spliced in (PSI) to assess the splicing pattern of the TTN gene. Normal splicing of TTN produces a rigid isoform, termed N2B, which lacks exon 51 through exon 218 (Fig. 2B). In uncorrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs, exons 51 to 218 were not spliced properly, generating the N2BA isoform (Fig. 2B and fig. S3A). This mis-spliced isoform reduces cardiac stiffness, leading to DCM (29). Expression of the N2B and N2BA isoforms in ABE-corrected iPSC-CMs was also validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis (Fig. 2C). Similarly, R634Q/+ iPSC-CMs also showed an abnormal alternative splicing pattern compared to normal iPSC-CMs (Fig. 2C and fig. S3A). In contrast, ABE-corrected iPSC-CMs displayed the same TTN splicing pattern as normal iPSC-CMs (Fig. 2C and fig. S3A). In addition, the abnormal splicing pattern of CAMK2δ was also restored (fig. S3B). Thus, ABE correction of the RBM20R634Q mutation was effective in restoring proper RNA splicing.

Fig. 2. Correctionof the pathological phenotype of RBM20R634Q iPSC-CMs after ABE.

(A) Heatmap of the alternative splicing patterns in WT, heterozygous (R634Q/+), homozygous (R634Q/R634Q), and corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs. RNA-seq analysis was performed on three independent differentiated iPSC-CMs at day 40 after differentiation. (B) Illustration showing alternative splice isoforms of the TTN gene, TTN-N2BA and TTN-N2B. (C) Relative expression of TTN-N2B and TTN-N2BA isoforms quantified by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 5). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. (D) Percentage of adenine (A) to guanine (G) editing in corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs after ABE correction. A6 is on-target site. A14 is bystander site. (E) Immunocytochemistry of WT, R634Q/R634Q, and ABE-corrected R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs. α-Actinin (red), RBM20 (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of RBM20 subcellular localization in R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs before and after ABE correction (n = 100 to 150 total cells in each group; quantification was performed across three independent differentiation groups). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ****P < 0.0001.

Dysregulation of gene expression and calcium handling are common pathogenic phenotypes seen in CMs with RBM20 mutations. To assess the transcriptional consequences of the RBM20R634Q mutation and the effect of ABE gene editing, we performed RNA-seq and gene ontology (GO) analyses on iPSC-CMs in which RBM20 mRNA was expressed similarly across all groups (fig. S4, A to G). Down-regulated genes in R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs included categories related to cardiomyopathy and striated muscle contraction, consistent with the phenotype of DCM. The abnormal transcriptome seen in R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs was restored following ABE editing (fig. S4, C and H to J). Calcium transient kinetics, including time to peak and decay rate (tau), were abnormally elevated in both R634Q/+ and R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs (fig. S4, K and L). After ABE-mediated correction, iPSC-CMs displayed normal calcium transient kinetics, indicating restoration of calcium release and reuptake (fig. S4, K and L).

Restoration of RBM20 nuclear localization and elimination of RNP granules are required for proper cardiac function. To assess the impact of ABE on the accumulation of RNP formation, we used adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (AAV6) and the trans-splicing intein system (28) to deliver ABE components driven by the cardiac troponin T (cTnT) promoter into differentiated R634Q/R634Q CMs (fig. S5, A and B). After ABE correction, the corrected iPSC-CMs showed 63% editing efficiency at the genomic level (Fig. 2D and fig. S5C). Immunocytochemistry showed localization of RBM20 in the nucleus and elimination of RNP granules in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S5D). These findings indicate that ABE can rescue the normal cardiac phenotype and prevent the formation of RNP granules.

PE in iPSCs with the RBM20R636S mutation

Despite the high efficiency of ABE gene editing of the RBM20R634Q mutation, BE cannot correct all RBM20 mutations because of the limited editing window, unwanted bystander editing, and the lack of a proper PAM sequence near some target nucleotides. To overcome these limitations, we developed a PE strategy for the p.R636S (c.1906 C>A) mutation, because BE can mainly convert C-G to T-A or A-T to G-C. We designed the engineered PE guide RNA (epegRNA), which has a structured motif on the 3′ terminus for protection from degradation (30) and selected the nicking sgRNA for the PE3b system (fig. S6A). The PE3bmax coupled with epegRNA resulted in A-to-C editing with an efficiency of 40% without unintended genomic edits in an isogenic iPSC line with the homozygous RBM20R636S (R636S/R636S) mutation (fig. S6, B and C). Whereas RNP granules were detected in the cytoplasm of uncorrected R636S/R636S iPSC-CMs, a normal pattern of nuclear localization was observed in PE-corrected iPSC-CMs (fig. S6D). After genomic editing, each iPSC line corrected by BE or PE displayed a normal karyotype (fig. S6E). To assess possible off-target editing, we performed deep sequencing analysis of the eight off-target sites predicted by CRISPOR and found no detectable genomic alterations at any of the potential off-target sites (fig. S7, A to C).

Postnatal ABE correction of the pathogenic RBM20 mutation in mice

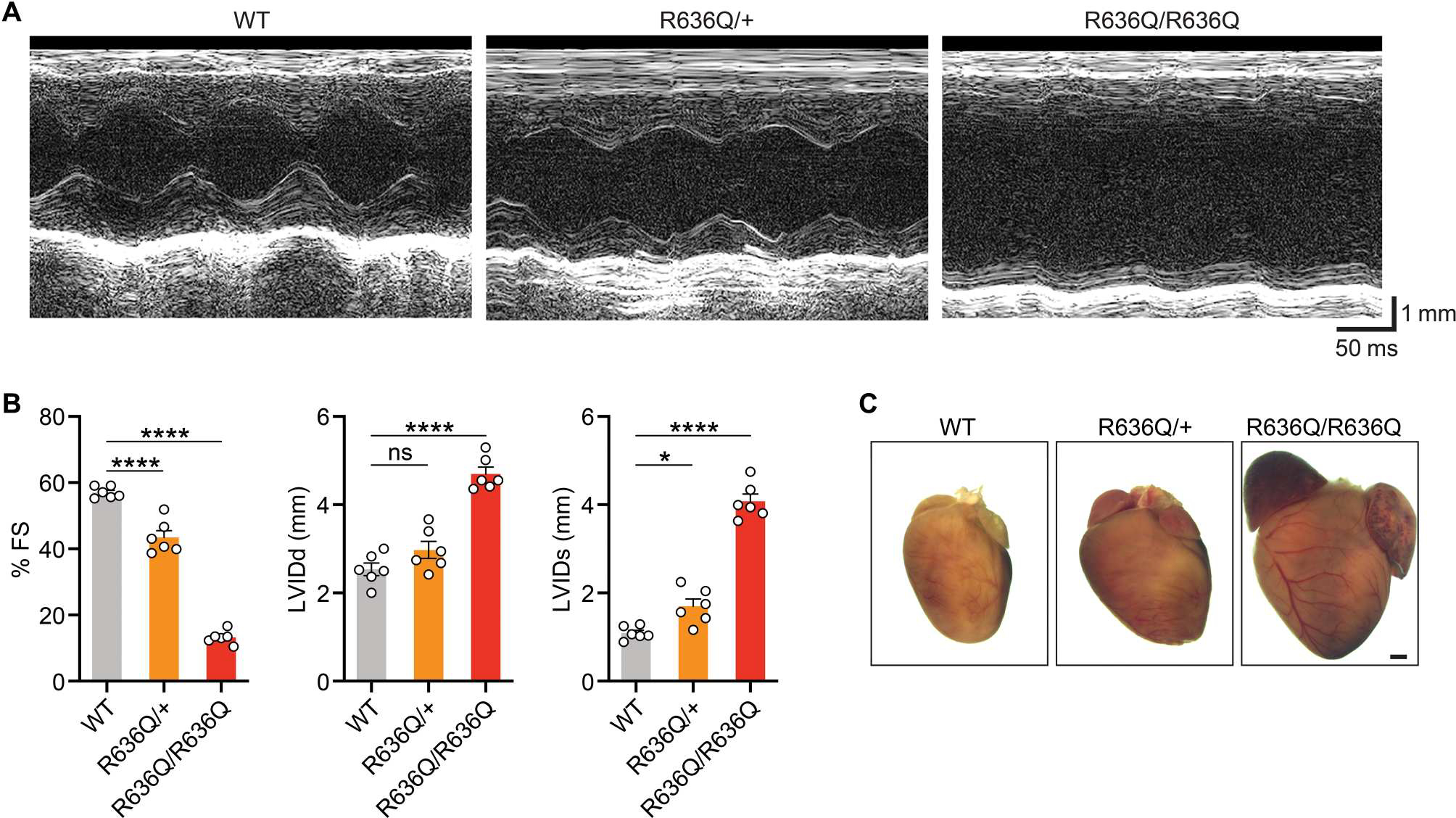

To evaluate the potential of ABE for in vivo DCM therapy, we generated a Rbm20R636Q mutant mouse model, which corresponds to the human RBM20R634Q mutation due to differences in numbers of amino acids in the protein from the two species (fig. S8, A and B). Cardiac function was measured in 4-week-old mutant mice by echocardiography. Homozygous (R636Q/R636Q) mice showed markedly reduced fractional shortening (Fig. 3, A and B). Left ventricular internal dimensions during end-diastole (LVIDd) and endsystole (LVIDs) were substantially increased in R636Q/R636Q mice compared to WT mice. Heterozygous (R636Q/+) mice demonstrated mild cardiac dysfunction (Fig. 3, A and B). Hearts of R636Q/R636Q mice at 12 weeks of age showed morphological characteristics consistent with DCM, including atrial and ventricular dilation (Fig. 3C). Thus, the R636Q/R636Q mice recapitulate the phenotype of DCM patients harboring the RBM20R634Q mutation.

Fig. 3. Cardiac dysfunction in Rbm20R636Q mice.

(A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic tracings from 4-week-old WT, heterozygous (R636Q/+), and homozygous (R636Q/R636Q) mice. (B) Fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular end-diastolic (LVIDd) and end-systolic (LVIDs) diameters measured by echocardiography. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 6 per genotype). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. *P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001. (C) Representative hearts from 12-week-old mice of indicated genotypes. Scale bar, 1 mm.

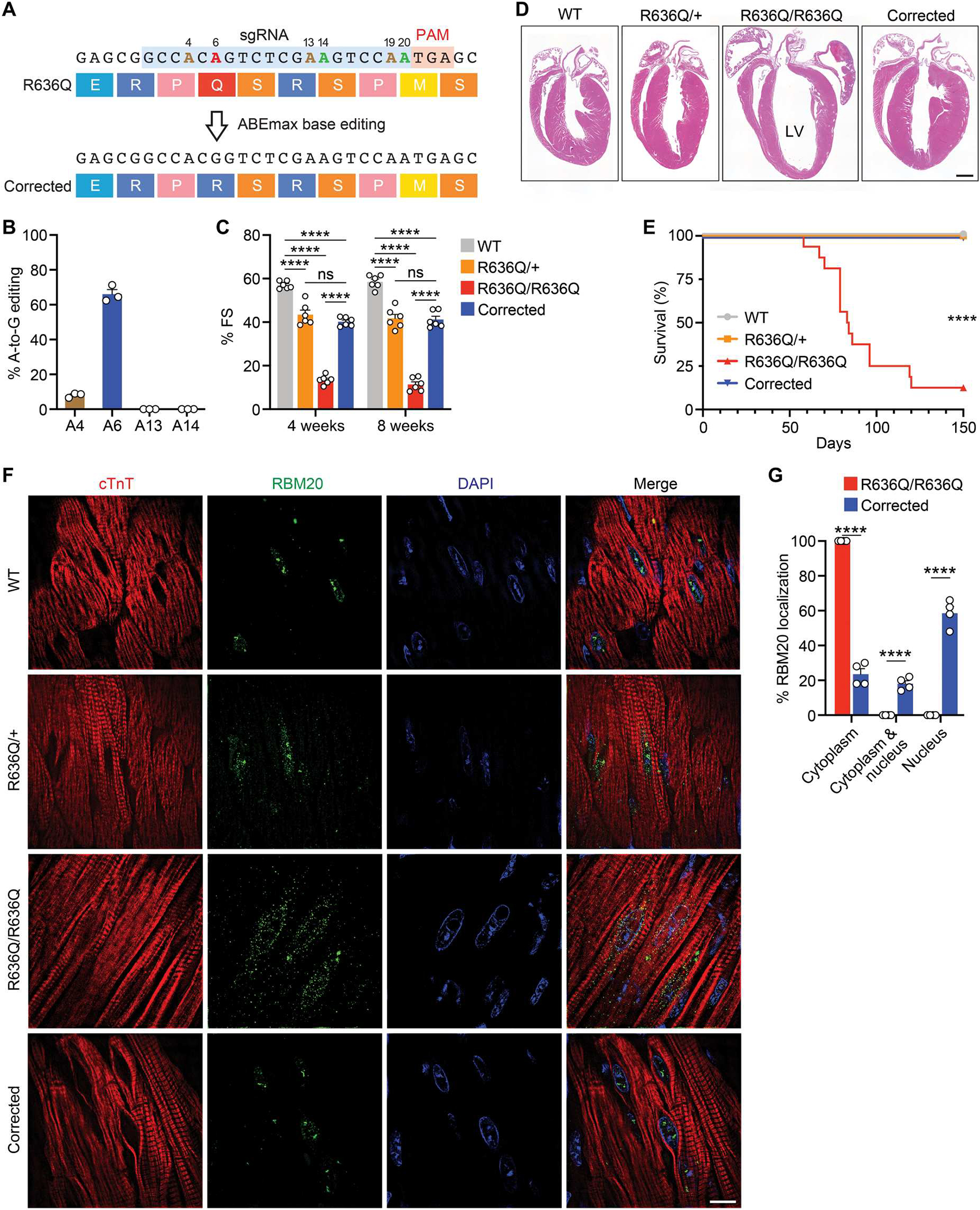

The R636Q/R636Q mutant mouse model enabled us to assess the possibility of in vivo correction of the RBM20R634Q mutation by ABE. For ABE correction in mice, the targeted adenine is positioned in the sgRNA at the A6 position, with possible bystander mutations found at A14 and A20, and possible silent mutations at A4, A13, and A19 (Fig. 4A). ABE components were administered by intraperitoneal injection of AAV9 at a dose of 1.25 × 1014 vg/kg for each AAV (total 2.5 × 1014 vg/kg) to mice at postnatal day 5 (fig. S9A). At this age, R636Q/R636Q mice already showed cardiac dysfunction compared to normal mice (fig. S9, B to D).

Fig. 4. Systemic delivery of ABE components by AAV9 restored cardiac function.

(A) ABE correction of the R636Q mutation using sgRNA (blue) and ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9. On-target: A6 (red). Bystander: A14 and A20 (green). Silent: A4, A13, and A19 (brown). (B) Percentage of adenine-to-guanine editing determined by deep sequencing of cDNA from hearts of R636Q/R636Q mice (6 weeks after ABE correction). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Fractional shortening at 4 and 8 weeks after ABE correction in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ****P < 0.0001. (D) H&E staining of four-chamber hearts (12 weeks after ABE correction). Scale bar, 1 mm. LV, left ventricle. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of all groups (n = 16 per group). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed. ****P < 0.0001 for R636Q/R636Q versus other groups. (F) Immunohistochemistry showing the translocation of RBM20 in CMs of WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected mice (12 weeks after ABE correction). cTnT (red), RBM20 (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Quantification of RBM20 localization before and after correction in R636Q/R636Q mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 4 per genotype). Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ****P < 0.0001.

To confirm whether ABE-mediated correction was effective in vivo, we assessed DNA editing efficiency in the heart. Deep sequencing analysis showed 19% of the targeted A-to-G conversion in the hearts of R636Q/R636Q mice at 6 weeks after ABE correction (fig. S10A). Genomic editing analysis underestimates ABE editing efficiency because other cell types, such as endothelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts, which comprise up to two-thirds of the cells of the heart, are not edited because of expression of the base editor under the control of the cardiac-specific cTnT promoter. Therefore, we further evaluated ABE gene editing at the complementary DNA (cDNA) level, which detects transcripts expressed from CMs, and found that 66% of RBM20 cDNA transcripts were precisely corrected (Fig. 4B and fig. S10B).

To assess cardiac function after ABE correction, we performed echocardiography in R636Q/R636Q mice at 4 and 8 weeks after systemic delivery of ABE gene editing components. Uncorrected R636Q/R636Q mice exhibited severe heart failure and premature death at 2 to 3 months of age. In contrast, R636Q/R636Q mice receiving systemic ABE components showed a substantial improvement of LV function, as measured by fractional shortening (Fig. 4C). In addition, cardiac chamber size was also partially rescued (fig. S10, C and D). Histological analysis of ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q hearts at 12 weeks after ABE correction showed recovery from cardiac dilation, whereas untreated hearts displayed atrial and ventricular enlargement (Fig. 4D). Histological assessment revealed no notable fibrosis of the left ventricular myocardium in treated R636Q/R636Q mice (fig. S11, A to C). Systemic delivery of ABE editing components also increased the life span of the corrected R636Q/R636Q mice (Fig. 4E).

To determine whether the restoration of cardiac function was attributable to restored function of RBM20, we evaluated the localization of RBM20 in vivo. In WT mice, RBM20 was localized to the nucleus without formation of RNP granules (Fig. 4F). In contrast, CMs of R636Q/R636Q mice displayed RNP granules in the perinuclear region, as in R634Q/R634Q iPSC-CMs. R636Q/+ mice showed RBM20 expression in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. ABE-mediated correction of R636Q/R636Q mice restored RBM20 localization to the nucleus and eliminated RNP granules as assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4, F and G). Next, we assessed the splicing pattern of Ttn in R636Q/R636Q mice after systemic ABE gene editing. As observed with iPSC-CMs, qRT-PCR analysis showed a reduction of the rigid N2B isoform and an increase in abundance of the compliant N2BA isoform in the R636Q/+ and R636Q/R636Q mice (fig. S12A). In contrast, ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q mice showed partial restoration (68%) of the N2B isoform and a reduction (63%) of the N2BA isoform (fig. S12A).

Normalization of cardiac gene expression by ABE

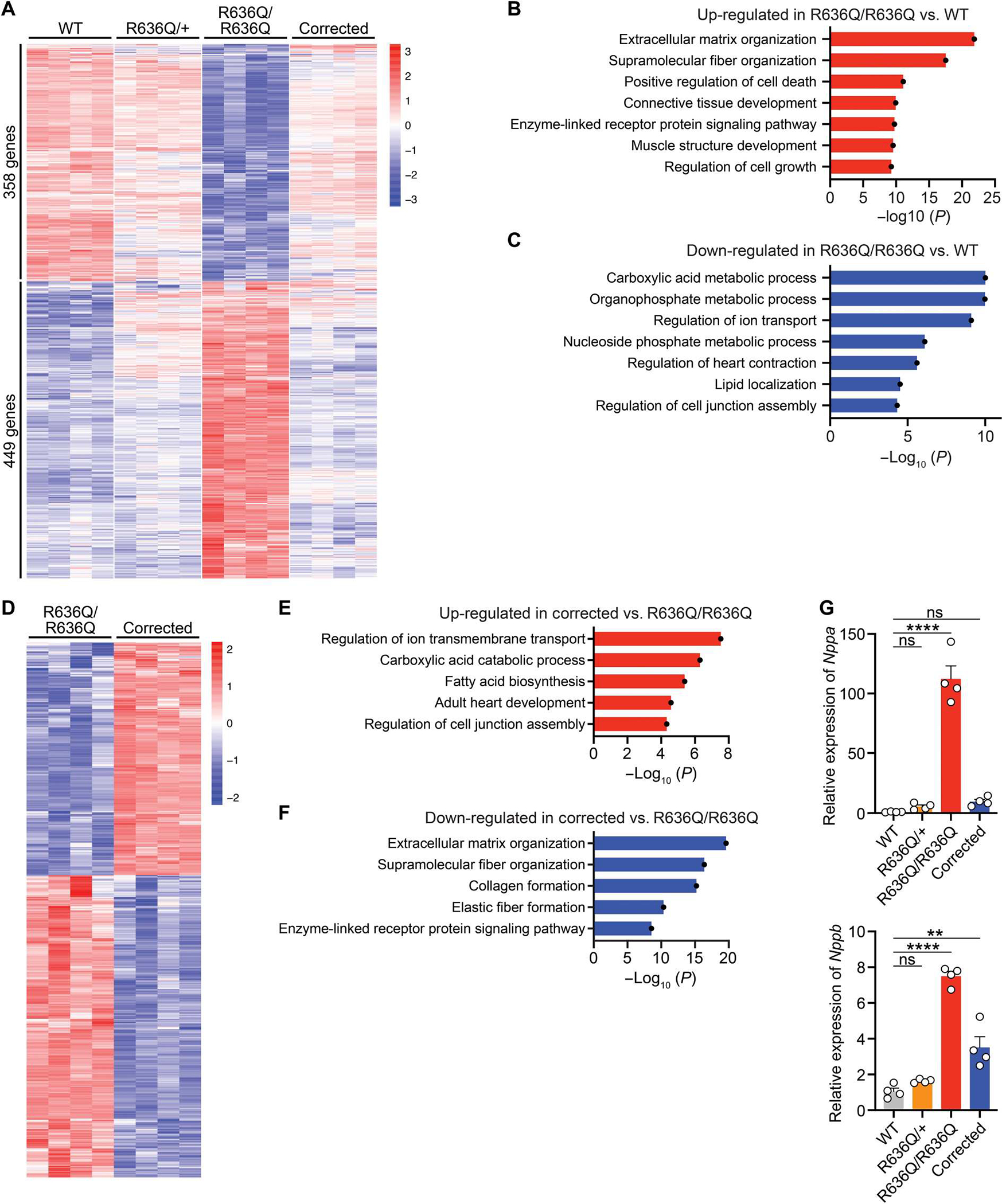

To determine whether ABE gene editing could normalize gene expression in R636Q/R636Q mice, we performed RNA-seq analysis. In comparison to WT hearts, transcriptional changes were seen in hearts of R636Q/R636Q mice, as determined by analysis of heatmap and GO terms, including down-regulation of genes that regulate heart contraction and up-regulation of genes involved in extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 5, A to C). Systemic ABE gene editing of R636Q/R636Q mice improved the gene expression profile of corrected R636Q/R636Q hearts, as seen by down-regulation of genes indicative of heart failure such as natriuretic peptide A (Nppa) and natriuretic peptide B (Nppb) (Fig. 5, A and D to G, and fig. S12B). In addition, RNA-seq analysis confirmed low off-target RNA editing in addition to high on-target editing activity in the corrected hearts (fig. S13, A and B).

Fig. 5. ABE normalized transcriptional expression in the heart.

(A) Heatmap showing the expression of differentially regulated genes in WT, heterozygous (R636Q/+), homozygous (R636Q/R636Q), and ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q (corrected) mice at 6 weeks after ABE correction (n = 4 per genotype). (B and C) GO terms associated with the up- and down-regulated genes in R636Q/R636Q mice compared to WT mice. (D to F) Heatmap showing differentially regulated gene expression (D) and GO terms associated with the up-regulated (E) and down-regulated genes (F) in corrected mice compared to R636Q/R636Q mice. (G) Relative expression of the Nppa and Nppb genes was quantified by qRT-PCR in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected mice at 6 weeks after ABE correction. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 4 per genotype). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001.

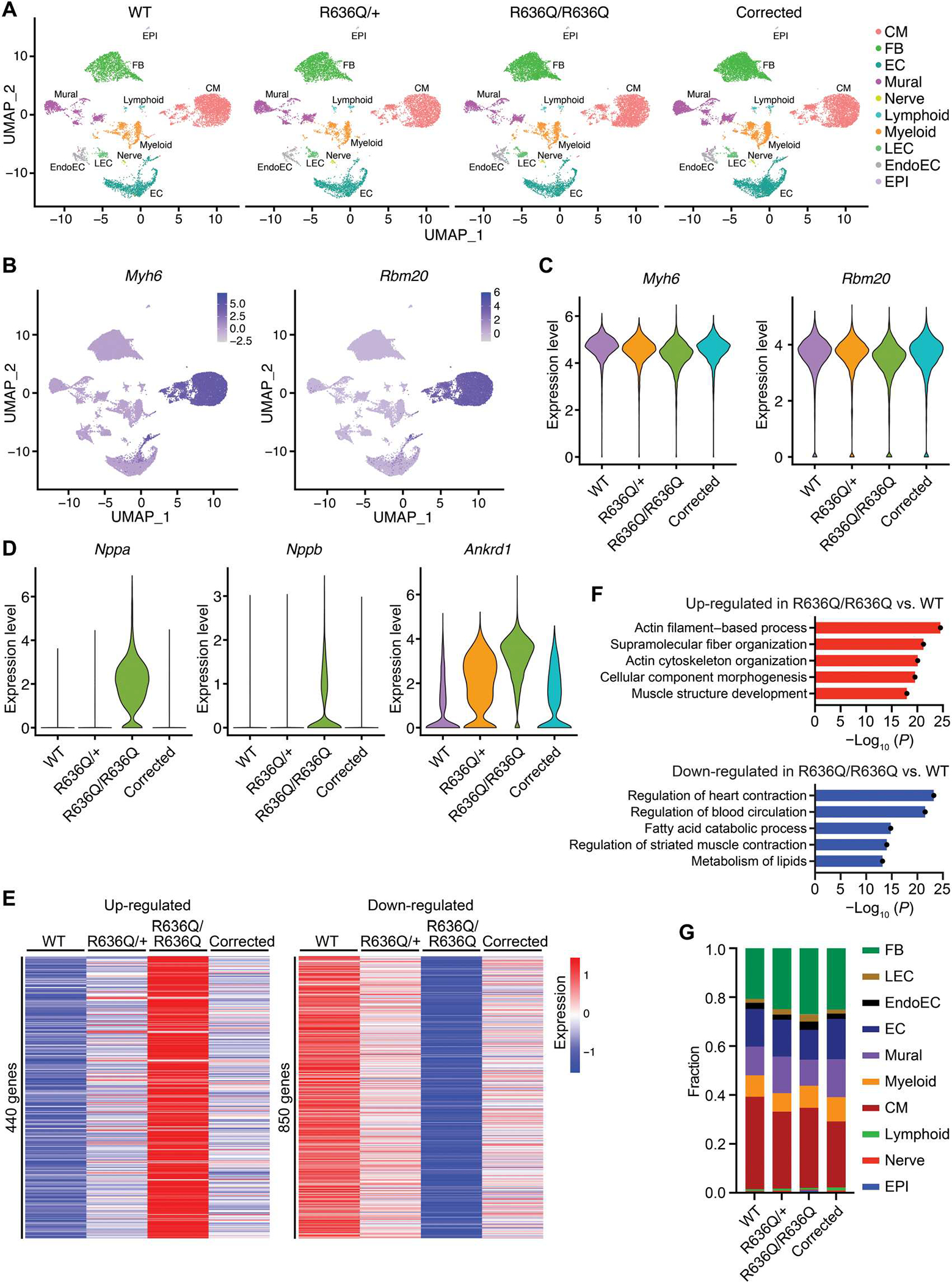

To investigate the transcriptional changes in the CM lineage of R636Q/R636Q mice after ABE correction, we performed single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) analysis. We observed that cell type clustering was similar in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected R636Q/R636Q mice (Fig. 6A) and that Rbm20 expression was restricted to the CM lineage, as defined by the expression of myosin heavy chain 6 (Myh6) gene (Fig. 6, B and C). Within the CM population, the dysregulated transcriptional profile of untreated R636Q/R636Q CMs was partially normalized in ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q CMs (Fig. 6, D to F, and fig. S14). Last, to assess possible inflammation induced by AAV9-mediated ABE correction, we examined the proportion of immune cells in the heart of R636Q/R636Q mice. In corrected mice, the total percentage of lymphoid cell and myeloid cell populations was only slightly increased compared to that of uncorrected mice (corrected, 11.2% versus uncorrected, 9.8%) (Fig. 6G).

Fig. 6. ABE correction restored the transcriptome in the R636Q/R636Q CMs.

(A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of all nuclei from WT, heterozygous (R636Q/+), homozygous (R636Q/R636Q), and ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q (corrected) hearts at 6 weeks after ABE correction by cluster identity. FB, fibroblasts; LEC, lymphatic endothelial cells; EndoEC, endocardial cells; EC, endothelial cells; EPI, epicardial cells. (B) Expression pattern of Myh6 and Rbm20 in each cluster on the UMAP graph. Color scale represents the expression of gene. (C) Violin plot showing the expression of Myh6 and Rbm20 in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected CMs. (D) Violin plot showing the expression of Nppa, Nppb, and Ankrd1 in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and corrected CMs. (E) Heatmap showing expression of up- and down-regulated genes in R636Q/R636Q compared to WT. (F) GO terms associated with the DE genes in R636Q/R636Q compared to WT. (G) Fraction of cell populations in WT, R636Q/+, R636Q/R636Q, and ABE-corrected R636Q/R636Q samples.

We performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay to detect apoptotic cells and assess cell damage in the heart at 12 weeks after ABE correction. ABE-mediated correction reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells compared to untreated R636Q/R636Q mice (fig. S15, A and B).

Absence of liver tumors in ABE mice

As a safety feature, our AAV9 delivery system contained a cardiac-specific promoter, cTnT, to drive ABE exclusively in the heart. Although systemic ABE therapy has been reported to cause liver tumors in mice (28), no solid liver tumors were observed for up to 3 months in our mice, likely because of the cardiac-specific expression of the base editor (fig. S15C).

DISCUSSION

Despite current medical advancements, effective treatment for familial cardiomyopathies remains challenging. Gene disruption can be deployed to target dominant-negative or pathogenic gain-of-function mutations by preventing expression of the mutant allele and eliminating the dysfunctional protein. However, many genetic mutations cannot be corrected by these strategies because of haplo-insufficiency of the modified protein product. Precise gene correction strategies allow the potential correction of monogenic mutations responsible for various cardiomyopathies by gene editing. Therapeutic approaches using BE and PE have been applied for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, progeria, inheritable liver, and eye disorders in vivo (28, 31–37). The pathophysiology of RBM20 mutations is caused by a mixture of a loss of function and a pathogenic gain of function (11, 13, 15). Therefore, RBM20 mutations are potentially well suited for correction by precise genomic editing. In this study, we performed precise gene editing of RBM20 mutations by BE and PE. Systemic ABE correction decreased toxic RNP granules present in CMs and rescued cardiac dysfunction in mice.

DNA off-target editing has been raised as a potential concern for clinical translation. Although BE can correct point mutations without double-strand breaks, other bystander mutations and off-target sites should be carefully investigated. Although ABE8e can efficiently edit the R634Q mutation, it may induce bystander mutations because of its wider editing window. To overcome this, ABEmax has a narrower editing window and may be a preferable editing enzyme. We found that ABE with ABEmax resulted in a low percentage of off-target editing despite a high editing efficiency at the on-target site. Off-target RNA editing has also been reported with ABE correction (38, 39). In this study, no off-target RNA editing was observed in corrected R636Q/R636Q mouse hearts after ABE correction. To expand the accessibility to genomic regions, many variants of SpCas9 and SaCas9 have been engineered. Selection of the proper variant of Cas9 is important for reducing off-target effects of BE in the genome. PE can theoretically correct mutations such as base substitutions, deletions, and insertions. Although the PE3 system uses two opposite nicks to increase the editing efficiency, it can also induce unintended indels. To reduce undesired indels, the PE3b system with an sgRNA recognizing the edited sequence may be considered. We also detected no solid tumors in the livers of mice 3 months after AAV delivery of gene editing components. Using tissue-specific promoters may be effective to prevent unintended editing in other tissues. However, it is necessary to evaluate the long-term effects of genomic editing.

AAV is the most widely used viral vector for gene delivery to the heart (40). The large size of the BE and PE systems pose challenges for efficient delivery of these gene editing components by AAV. Compact Cas9 orthologs such as the Neisseria meningitidis (NmeCas9) (41), Staphylococcus auricularis (SauriCas9) (42), and Campylobacter jejuni (CjCas9) (43) are promising Cas9 systems for establishing consolidated BE systems. Other delivery methods such as nanoparticles may also solve such a bottleneck if they could be efficiently delivered to CMs (44, 45). Immunogenicity is another concern for clinical application (46). However, analysis of snRNA-seq data revealed a minimal increase of immune cells after AAV9 treatment.

There are some limitations to this study. First, we used homozygous mice for correction because homozygous mice show severe cardiac dysfunction and premature death as seen in human patients. Whereas RBM20 mutations display autosomal dominant inheritance in human patients, heterozygous mice demonstrated relatively mild cardiac dysfunction. In addition, the transcriptomes of hearts from corrected mice were similar to those of hearts from heterozygous mice. Long-term studies of heterozygous mice will be of interest as a potential prelude to clinical application. In addition, long-term follow-up studies to address possible immune responses and tumorigenesis should ultimately be pursued. Last, morphological characteristics of hearts from homozygous mice seemed to demonstrate biventricular heart failure, which is observed in patients who have RBM20 mutations. However, further investigations related to the right ventricular dysfunction will be needed before and after correction. Despite various challenges and issues of safety, the pace and potential of this field of investigation promise to revolutionize the treatment of genetic cardiomyopathies and many other genetic disorders in the foreseeable future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study aimed to test the therapeutic potential of BE and PE for RNA binding motif protein 20 gene (RBM20) mutations in human cells and a mouse model of DCM. We did not use exclusion, randomization, or blind approaches to assign the animals for the experiments. All echocardiography experiments were performed and analyzed by a single blinded operator. Each experiment was performed in biological replicate as indicated by n values in the figure legends.

Study approval

All experimental procedures involving animals in this study were reviewed and approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Use of iPSC lines was reviewed and approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee.

All-in-one SpCas9-ABE variants and SaCas9-ABE vectors

All variants of SpCas9 and SaCas9 were synthesized by g-Block (Integrated DNATechnologies) and subcloned into Age I/Fse I–digested pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (px458) (Addgene plasmid no. 48138) (47) from F. Zhang’s laboratory (Broad Institute) using In-Fusion ligation (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. These vectors were digested by Age I and Apa I. The inserts were transcribed from NG-ABEmax (Addgene plasmid no. 124163) (48) and NG-ABE8e (Addgene plasmid no. 138491) (19) from D. Liu’s laboratory (Broad Institute). These inserts were subcloned into predigested pSpCas9-NG-2A-GFP, pSpCas9-VRQR-2A-GFP, and pSaCas9–2A-GFP using an In-Fusion cloning kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sgRNAs (table S1) for ABE of the RBM20R634Q mutation were subcloned into engineered vectors using Bbs I and T4 ligation. Primers are listed in table S2.

Human iPSC lines

Human iPSC lines were generated and maintained as previously described (49). Briefly, iPSCs were maintained in mTeSR plus medium (STEMCELL Technologies) and passaged using Versene (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10 μM Rock inhibitor, Y-27632 (Selleckchem) every 4 days. A single-cell suspension of 8 × 105 iPSCs was mixed with a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) template and 5 μg of pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (px458) plasmid containing sgRNA for exon 9 of RBM20. The mixture was transfected by a Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X kit (Lonza) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After nucleofection, iPSCs were maintained in mTeSR plus medium with Rock inhibitor and Primocin (Invivogen). Green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) at 48 hours after nucleofection and expanded. Single clones of GFP+ single iPSCs were picked, and genomic sequencing was performed for heterozygous (R634Q/+), homozygous (R634Q/R634Q), and homozygous (R636S/R636S) lines. Sequences of ssODNs are listed in table S2.

BE and PE in iPSCs

For ABE, 5 μg of engineered all-in-one vector including sgRNA was transfected into heterozygous (R634Q/+) or homozygous (R634Q/R634Q) iPSCs by nucleofection. Forty-eight hours later, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and expanded. For PE, pegRNA and epegRNA were subcloned into pU6-pegRNA-GG-acceptor plasmid (Addgene plasmid no. 132777) (21) from D. Liu’s laboratory. The nicking sgRNA was subcloned into pmCherry_gRNA plasmid (Addgene plasmid no. 80457) from E. Welker’s laboratory (Hungarian Academy of Sciences). For the PE3b system, pCMV-PE2-P2A-GFP (Addgene plasmid no. 132776) (21) from D. Liu’s laboratory, pegRNA, and nicking sgRNA plasmids (4.5, 1.5, and 0.75 μg, respectively) were transfected into 8 × 105 homozygous (R636S/R636S) iPSCs by nucleofection. For PE3bmax coupled with epegRNA, pCMV-PEmax (Addgene plasmid no. 174820) (30) from D. Liu’s laboratory, epegRNA, and nicking sgRNA plasmids (4.5, 1.5, and 0.75 μg, respectively) were transfected by nucleofection. After 48 hours, GFP+ and mCherry+ cells in PE3b-treated iPSCs and mCherry+ cells in PE3bmax-treated iPSCs were sorted by FACS and expanded. Single clones of edited iPSCs were picked and established. After extracting DNA, the region of exon9 in RBM20 was amplified by PCR, and PCR products were subjected to ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced. After BE and PE, G-Banded karyotyping was assessed by WiCell Research Institute Inc. (https://wicell.org).

Human iPSC-CM differentiation

iPSCs were induced to differentiate into CMs using previously described methods (50). iPSCs were treated with CHIR 99021 (Selleckchem) in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with CDM3 for 2 days (days 1 and 2). The medium was changed to RPMI supplemented with WNT-C59 (Selleckchem) for 2 days (days 3 and 4). iPSC-CMs were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with B27-supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific). iPSC-CMs were purified by metabolic selection in RPMI 1640 without glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 5 mM sodium dl-lactate and CDM3 supplement for 6 days (days 10 to 16). After metabolic selection, iPSC-CMs were replated into six-well plates using TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The iPSC-CMs were >95% pure as determined by cTnT staining (Proteintech, 15513–1-AP, 1:250). CMs were used for experiments on days 35 to 40 after differentiation. Each experiment was performed in replicate using independent differentiated iPSC-CMs. Regarding the ABE- and PE-corrected iPSC-CMs, single clones of iPSCs were isolated and differentiated into iPSC-CMs for assays.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (49). iPSC-CMs were dissolved in RIPA buffer (Boston BioProducts, BP-115–250) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78438), and 15 μg of total protein was loaded on a 4 to 20% acrylamide gel. Gels were run at 100 V for 15 min and at 150 V for 1 hour, followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 100 V for 60 min at 4°C. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk for 60 min at room temperature and probed with goat anti-RBM20 antibody (Novus Biologicals, NBP2–27509, 1:1000) at 4°C overnight. Peroxidase AffiniPure bovine anti-goat horseradish peroxidase antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, catalog no. 805–035-180) was used as secondary antibody. Anti-vinculin (V9131, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:1000 dilution) was used as loading control.

Immunocytochemistry of iPSC-CMs

Immunocytochemistry of iPSC-CMs was performed as previously described (34). Briefly, iPSC-CMs were replaced on 12-mm coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min) and permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100 (15 min), coverslips were blocked for 1 hour with 5% goat serum/phosphate-buffered saline. Rabbit anti-RBM20 antibody (Novus Biologicals, NBP2–34038, 1:250), mouse anti-G3BP1 (Proteintech 66486–1-Ig, 1:250), and mouse anti–α-actinin (Sigma-Aldrich, A7811, 1:800) in 5% goat serum/phosphate-buffered saline was applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. Then, coverslips were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen). Sodium arsenite (1 mM for 1 hour) was used for inducing stress granules. Images were taken by a Zeiss LSM 800 microscope using a 20× objective and N-SIM S Super Resolution Microscope (Nikon) using a 100× oil objective.

Calcium imaging of human iPSC-CMs

Calcium imaging was performed as previously described (34). Briefly, CMs were dissociated and seeded on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Calcium imaging was evaluated 3 days after plating. CMs were loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator Fluo-4-AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, F14201) at 5 μM for 20 min in Tyrode’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich, T2397). The calcium transients of spontaneous beating iPSC-CMs were measured at 37°C using a Nikon A1R+ confocal microscope. Data were processed by Fiji software and analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

AAV delivery to differentiated iPSC-CMs

The cTnT promoter was extracted from the pAAV:cTNT::Luciferase (Addgene plasmid no. 69915) (51) from W. Pu’s laboratory (Harvard). The N-terminal and C-terminal regions of ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9 were extracted from CMV_Npu-ABEmax N-terminal (Addgene plasmid no. 137173) (52) and hu6 HGPS sgRNA expression and ABE7.10max VRQR C-terminal AAV vectors (Addgene plasmid no. 154430) (28) from D. Liu’s laboratory, respectively. These inserts were subcloned into pSSV9 single-stranded AAV plasmid using In-Fusion cloning. AAV vectors were digested using Sma I and Ahd I to confirm intact inverted terminal repeat integrity. AAV viruses were generated with serotype 6 (AAV6) and serotype 9 (AAV9) capsids in the Boston Children’s Hospital Viral Core. AAV6 viruses were infected into homozygous (R634Q/R634Q) iPSC-CMs at day 40 after differentiation with 4 × 105 vg/cell. Twenty days after infection, DNA was extracted.

Generating Rbm20R636Q knock-in mice

Rbm20R636Q knock-in mice were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 technology with ssODN template as described previously (53). The sgRNA for exon 9 of Rbm20 was cloned into pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (px458). The sgRNAs were transcribed using the MEGA shortscript T7 Transcription kit and purified by a MEGA clear kit (Life Technologies). Cas9 mRNA, Rbm20 sgRNA, and ssODN including the Rbm20R636Q mutation were injected into mouse pronuclei and cytoplasm. Mouse embryos were transferred to a surrogate dam for gestation. F0 generation pups were sequenced, and positive founders were bred to WT C57/BL6 mice to isolate potential knock-in alleles. Mutants in the F1 generation were identified by sequencing. Both male and female mice were used in this study. Tail genomic DNA was extracted and used for genotyping.

Systemic AAV9 delivery in vivo

P5 homozygous (R636Q/R636Q) mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μl of AAV9 containing N-terminal and C-terminal ABEmax-VRQR-SpCas9-sgRNA (total of 2.5 × 1014 vg/kg) using an ultrafine BD insulin syringe (Becton Dickinson).

Transthoracic echocardiography

Cardiac function was assessed by two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography using a VisualSonics Vevo2100 imaging system. Fractional shortening, LVIDd, and LVIDs were measured using M-mode tracing. All measurements were performed by an operator blinded to this study.

Extraction of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA of iPSCs, iPSC-CMs, and murine hearts was extracted using DirectPCR lysis reagent (VIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted genomic DNA was amplified using PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR products were sequenced and analyzed by EditR for gene editing efficiency. PCR primers are listed in table S2.

Immunohistochemistry

Hearts were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 48 hours. After fixation, gross images of hearts were taken by a Zeiss AxioZoom.V16 system. Hearts were embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and picrosirius red staining was performed. Images were taken by a digital microscope (Keyence) with 4× and 40× objective magnifications. For immunohistochemistry, sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval using epitope retrieval solution (IHC WORLD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CMs were stained by primary antibodies of cTnT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:200) and RBM20 (a gift from W. Guo, 1:400). Sections were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen). Images were taken by N-SIM S Super Resolution Microscope (Nikon) using a 100× oil objective. TUNEL assay was performed using Click-iT Plus TUNEL assay kits for in situ apoptosis detection (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10619) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Livers were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 48 hours. After fixation, the livers were sliced at 5-mm thickness. H&E staining was performed.

Amplicon deep sequencing analysis

Off target sites were predicted by CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net). PCR products from genomic DNA and cDNA were generated using PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase. Primers were designed for human RBM20 exon 9, off-target sites of BE and PE, and mouse Rbm20 exon 9 with adaptor sequence (forward, TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG and reverse, GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG). A second round of PCR was performed to add Illumina flow cell binding sequence and barcodes. Primer sequences are listed in table S2.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from iPSC-CMs at day 40 after differentiation and murine hearts at 6-weeks after injection using miRNeasy (Qiagen), and cDNA was reverse-transcribed using iScript reverse transcription supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For RT-PCR, cDNA was amplified using PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (Takara Bio). For qRT-PCR, gene expression was measured using KAPA SYBR FAST Master mix (KAPA) and quantified by the Ct method. For normalization of qRT-PCR, we used 18s. RT-PCR and qRT-PCR primers are listed in table S2.

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

Library prep from total RNA was performed using a KAPA mRNA Hyper prep kit (Roche, KK8581) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 system using the 75-bp high-output sequencing kit for pair-end sequencing. Trim Galore (https://bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/ projects/trim_galore/) was used for quality and adapter trimming. The qualities of RNA-sequencing libraries were estimated by mapping the reads onto human transcript and ribosomal RNA sequences (Ensembl release 89) using Bowtie (v2.3.4.3) (54). STAR (v2.7.2b) (55) was used to align the reads onto the human genome (hg38). SAMtools (v1.9) (56) was used to sort the alignments, and HTSeq Python package (57) was used to count reads per gene. edgeR R Bioconductor package (58–60) was used to normalize read counts and identify differentially expressed (DE) genes. DE genes (fold change >2 in homozygous compared to normal, adjusted P value <0.05) were analyzed in experiments using iPSC-CMs or murine hearts. GO analysis was performed using Metascape (61), and selective GO terms were shown. SpliceFisher (https://github.com/jiwoongbio/SpliceFisher) was used to identify differential alternative splicing events and calculate PSI values. To calculate the average percentage of A-to-I editing, we adopted a previous strategy (28). Briefly, REDItools2 (62) was used to quantify the percentage editing in each sample. Nucleotides except adenosines were removed, and remaining adenosines with read coverage less than 10 or read quality score below 25 were also filtered to avoid errors due to low sampling or low sequencing quality. We then calculated the number of A-to-I conversions in each sample and divided this by the total number of adenosines in our dataset after filtering to get the percentage of A-to-I editing in the transcriptome.

snRNA-seq analysis

Isolation of cardiac single nuclei was performed as previously described (63). Briefly, three hearts of 6-week-old mice were extracted in each group. Both ventricles were collected and minced with a razor blade on ice. Minced hearts were homogenized with a dounce grinder. Cell suspension was sequentially filtered through 70- and 40-μm cell strainers (Falcon, 352350 and 352340), and centrifuged at 500g for 5 min. snRNA-seq libraries were generated using Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v3 (10x Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 system. Sequence data were analyzed by Cell Ranger Single-Cell Software Suite. The cDNA reads were mapped on the mm10/GRCm38 reference genome. DE genes were analyzed (fold change >1.5 in homozygous compared to normal hearts, P value <0.001). Seurat R package (64) was used for creating GO analysis and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as means ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were performed for comparison between the two groups as indicated in the figures. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed to analyze other data. Data analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank J. Cabrera for graphical assistance; J. Shelton and the UT Southwestern Histology Core for histopathology; J. Xu and the Sequencing Facility at Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern for performing Illumina sequencing; W. Guo for sharing mouse RBM20 antibody; and D. R. Liu, F. Zhang, W. T. Pu, and E. Welker for providing Addgene plasmids.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grants R01HL130253, P50HD087351, and R01HL157281 to E.N.O. and R.B.-D., Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence to E.N.O., Uehara Memorial Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship to T.N., and Japan Heart Foundation/Bayer Yakuhin Research Grant Abroad Fellowship to T.N.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The work in this manuscript has been included in patent application PCT/US2022/035666 entitled “Genomic Editing of RBM20 Mutations,” filed by UT Southwestern Medical Center and names T.N., R.B.-D., and E.N.O. as inventors. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. RNA-seq data generated during this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO series accession numbers GSE210783 and GSE211005. Materials used in this study are available to academic researchers through material transfer agreement with The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center by contacting R.B.-D. and E.N.O.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.McNally EM, Mestroni L, Dilated cardiomyopathy: Genetic determinants and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 121, 731–748 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A, Dilated cardiomyopathy: The complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 10, 531–547 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan E, Peterson L, Ai T, Asatryan B, Bronicki L, Brown E, Celeghin R, Edwards M, Fan J, Ingles J, James CA, Jarinova O, Johnson R, Judge DP, Lahrouchi N, Lekanne Deprez RH, Lumbers RT, Mazzarotto F, Medeiros Domingo A, Miller RL, Morales A, Murray B, Peters S, Pilichou K, Protonotarios A, Semsarian C, Shah P, Syrris P, Thaxton C, van Tintelen JP, Walsh R, Wang J, Ware J, Hershberger RE, Evidence-based assessment of genes in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 144, 7–19 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum AN, Agre KE, Pereira NL, Genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy: Practical implications for heart failure management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 286–297 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hey TM, Rasmussen TB, Madsen T, Aagaard MM, Harbo M, Molgaard H, Moller JE, Eiskjaer H, Mogensen J, Pathogenic RBM20-variants are associated with a severe disease expression in male patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail. 12, e005700 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brauch KM, Karst ML, Herron KJ, de Andrade M, Pellikka PA, Rodeheffer RJ, Michels VV, Olson TM, Mutations in ribonucleic acid binding protein gene cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54, 930–941 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li D, Morales A, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Norton N, Siegfried JD, Hofmeyer M, Hershberger RE, Identification of novel mutations in RBM20 in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin. Transl. Sci. 3, 90–97 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh VN, Caleshu C, Reuter C, Lazzeroni LC, Ingles J, Garcia J, McCaleb K, Adesiyun T, Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kumar S, Graw S, Gigli M, Stolfo D, Dal Ferro M, Ing AY, Nussbaum R, Funke B, Wheeler MT, Hershberger RE, Cook S, Steinmetz LM, Lakdawala NK, Taylor MRG, Mestroni L, Merlo M, Sinagra G, Semsarian C, Meder B, Judge DP, Ashley E, Regional variation in RBM20 causes a highly penetrant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail. 12, e005371 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lennermann D, Backs J, van den Hoogenhof MMG, New insights in RBM20 cardiomyopathy. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 17, 234–246 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe T, Kimura A, Kuroyanagi H, Alternative splicing regulator RBM20 and cardiomyopathy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 5, 105 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo W, Schafer S, Greaser ML, Radke MH, Liss M, Govindarajan T, Maatz H, Schulz H, Li S, Parrish AM, Dauksaite V, Vakeel P, Klaassen S, Gerull B, Thierfelder L, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Hacker TA, Saupe KW, Dec GW, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, Spallek B, Fischer R, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, Saar K, Hubner N, Gotthardt M, RBM20, a gene for hereditary cardiomyopathy, regulates titin splicing. Nat. Med. 18, 766–773 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahr HC, Jaalouk DE, Exploring the crosstalk between LMNA and splicing machinery gene mutations in dilated cardiomyopathy. Front. Genet. 9, 231 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider JW, Oommen S, Qureshi MY, Goetsch SC, Pease DR, Sundsbak RS, Guo W, Sun M, Sun H, Kuroyanagi H, Webster DA, Coutts AW, Holst KA, Edwards BS, Newville N, Hathcock MA, Melkamu T, Briganti F, Wei W, Romanelli MG, Fahrenkrug SC, Frantz DE, Olson TM, Steinmetz LM, Carlson DF, Nelson TJ; Wanek Program Preclinical Pipeline, Dysregulated ribonucleoprotein granules promote cardiomyopathy in RBM20 gene-edited pigs. Nat. Med. 26, 1788–1800 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihara K, Sasano T, Hiraoka Y, Togo-Ohno M, Soejima Y, Sawabe M, Tsuchiya M, Ogawa H, Furukawa T, Kuroyanagi H, A missense mutation in the RSRSP stretch of Rbm20 causes dilated cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation in mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 17894 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenix AM, Miyaoka Y, Bertero A, Blue SM, Spindler MJ, Tan KKB, Perez-Bermejo JA, Chan AH, Mayerl SJ, Nguyen TD, Russell CR, Lizarraga PP, Truong A, So PL, Kulkarni A, Chetal K, Sathe S, Sniadecki NJ, Yeo GW, Murry CE, Conklin BR, Salomonis N, Gain-of-function cardiomyopathic mutations in RBM20 rewire splicing regulation and re-distribute ribonucleoprotein granules within processing bodies. Nat. Commun. 12, 6324 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, Zhang Y, Methawasin M, Braz CU, Gao-Hu J, Yang B, Strom J, Gohlke J, Hacker T, Khatib H, Granzier H, Guo W, RBM20S639G mutation is a high genetic risk factor for premature death through RNA-protein condensates. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 165, 115–129 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Wang C, Sun M, Jin Y, Braz CU, Khatib H, Hacker TA, Liss M, Gotthardt M, Granzier H, Ge Y, Guo W, RBM20 phosphorylation and its role in nucleocytoplasmic transport and cardiac pathogenesis. FASEB J. 36, e22302 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR, Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter MF, Zhao KT, Eton E, Lapinaite A, Newby GA, Thuronyi BW, Wilson C, Koblan LW, Zeng J, Bauer DE, Doudna JA, Liu DR, Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 883–891 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees HA, Liu DR, Publisher Correction: Base editing: Precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 801 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR, Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anzalone AV, Koblan LW, Liu DR, Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 824–844 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama T, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Toward CRISPR therapies for cardiomyopathies. Circulation 144, 1525–1527 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N, Olson EN, CRISPR modeling and correction of cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 130, 1827–1850 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapinaite A, Knott GJ, Palumbo CM, Lin-Shiao E, Richter MF, Zhao KT, Beal PA, Liu DR, Doudna JA, DNA capture by a CRISPR-Cas9-guided adenine base editor. Science 369, 566–571 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koblan LW, Doman JL, Wilson C, Levy JM, Tay T, Newby GA, Maianti JP, Raguram A, Liu DR, Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 843–846 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Joung JK, High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529, 490–495 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koblan LW, Erdos MR, Wilson C, Cabral WA, Levy JM, Xiong ZM, Tavarez UL, Davison LM, Gete YG, Mao X, Newby GA, Doherty SP, Narisu N, Sheng Q, Krilow C, Lin CY, Gordon LB, Cao K, Collins FS, Brown JD, Liu DR, In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome in mice. Nature 589, 608–614 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beqqali A, Bollen IA, Rasmussen TB, van den Hoogenhof MM, van Deutekom HW, Schafer S, Haas J, Meder B, Sorensen KE, van Oort RJ, Mogensen J, Hubner N, Creemers EE, van der Velden J, Pinto YM, A mutation in the glutamate-rich region of RNA-binding motif protein 20 causes dilated cardiomyopathy through missplicing of titin and impaired Frank-Starling mechanism. Cardiovasc. Res. 112, 452–463 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen PJ, Hussmann JA, Yan J, Knipping F, Ravisankar P, Chen PF, Chen C, Nelson JW, Newby GA, Sahin M, Osborn MJ, Weissman JS, Adamson B, Liu DR, Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell 184, 5635–5652.e29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang H, Jo DH, Cho CS, Shin JH, Seo JH, Yu G, Gopalappa R, Kim D, Cho SR, Kim JH, Kim HH, Application of prime editing to the correction of mutations and phenotypes in adult mice with liver and eye diseases. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 181–194 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bock D, Rothgangl T, Villiger L, Schmidheini L, Matsushita M, Mathis N, Ioannidi E, Rimann N, Grisch-Chan HM, Kreutzer S, Kontarakis Z, Kopf M, Thony B, Schwank G, In vivo prime editing of a metabolic liver disease in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabl9238 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi EH, Suh S, Foik AT, Leinonen H, Newby GA, Gao XD, Banskota S, Hoang T, Du SW, Dong Z, Raguram A, Kohli S, Blackshaw S, Lyon DC, Liu DR, Palczewski K, In vivo base editing rescues cone photoreceptors in a mouse model of early-onset inherited retinal degeneration. Nat. Commun. 13, 1830 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chemello F, Chai AC, Li H, Rodriguez-Caycedo C, Sanchez-Ortiz E, Atmanli A, Mireault AA, Liu N, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Precise correction of Duchenne muscular dystrophy exon deletion mutations by base and prime editing. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg4910 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Zhang C, Li H, Wang P, Gao Y, Mokadam NA, Ma J, Arnold WD, Han R, Efficient precise in vivo base editing in adult dystrophic mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 3719 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whisenant D, Lim K, Revechon G, Yao H, Bergo MO, Machtel P, Kim JS, Eriksson M, Transient expression of an adenine base editor corrects the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation and improves the skin phenotype in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 3068 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B, Dong X, Cheng H, Zheng C, Chen Z, Rodriguez TC, Liang SQ, Xue W, Sontheimer EJ, A split prime editor with untethered reverse transcriptase and circular RNA template. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1388–1393 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou C, Sun Y, Yan R, Liu Y, Zuo E, Gu C, Han L, Wei Y, Hu X, Zeng R, Li Y, Zhou H, Guo F, Yang H, Off-target RNA mutation induced by DNA base editing and its elimination by mutagenesis. Nature 571, 275–278 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grunewald J, Zhou R, Garcia SP, Iyer S, Lareau CA, Aryee MJ, Joung JK, Transcriptome-wide off-target RNA editing induced by CRISPR-guided DNA base editors. Nature 569, 433–437 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chamberlain K, Riyad JM, Weber T, Cardiac gene therapy with adeno-associated virus-based vectors. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 32, 275–282 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibraheim R, Song CQ, Mir A, Amrani N, Xue W, Sontheimer EJ, All-in-one adeno-associated virus delivery and genome editing by Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 in vivo. Genome Biol. 19, 137 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Z, Wang S, Zhang C, Gao N, Li M, Wang D, Wang D, Liu D, Liu H, Ong SG, Wang H, Wang Y, A compact Cas9 ortholog from Staphylococcus auricularis (SauriCas9) expands the DNA targeting scope. PLOS Biol. 18, e3000686 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim E, Koo T, Park SW, Kim D, Kim K, Cho HY, Song DW, Lee KJ, Jung MH, Kim S, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim JS, In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 8, 14500 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banskota S, Raguram A, Suh S, Du SW, Davis JR, Choi EH, Wang X, Nielsen SC, Newby GA, Randolph PB, Osborn MJ, Musunuru K, Palczewski K, Liu DR, Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell 185, 250–265.e16 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulkarni JA, Cullis PR, van der Meel R, Lipid nanoparticles enabling gene therapies: From concepts to clinical utility. Nucleic Acid Ther. 28, 146–157 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chew WL, Tabebordbar M, Cheng JK, Mali P, Wu EY, Ng AH, Zhu K, Wagers AJ, Church GM, A multifunctional AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 and its host response. Nat. Methods 13, 868–874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F, Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang TP, Zhao KT, Miller SM, Gaudelli NM, Oakes BL, Fellmann C, Savage DF, Liu DR, Circularly permuted and PAM-modified Cas9 variants broaden the targeting scope of base editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 626–631 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Long C, Li H, McAnally JR, Baskin KK, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, CRISPR-Cpf1 correction of muscular dystrophy mutations in human cardiomyocytes and mice. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602814 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Min YL, Li H, Rodriguez-Caycedo C, Mireault AA, Huang J, Shelton JM, McAnally JR, Amoasii L, Mammen PPA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, CRISPR-Cas9 corrects Duchenne muscular dystrophy exon 44 deletion mutations in mice and human cells. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav4324 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin Z, von Gise A, Zhou P, Gu F, Ma Q, Jiang J, Yau AL, Buck JN, Gouin KA, van Gorp PR, Zhou B, Chen J, Seidman JG, Wang DZ, Pu WT, Cardiac-specific YAP activation improves cardiac function and survival in an experimental murine MI model. Circ. Res. 115, 354–363 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levy JM, Yeh WH, Pendse N, Davis JR, Hennessey E, Butcher R, Koblan LW, Comander J, Liu Q, Liu DR, Cytosine and adenine base editing of the brain, liver, retina, heart and skeletal muscle of mice via adeno-associated viruses. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 97–110 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, Winders BR, Troupes CD, Wu F, Reese AL, McAnally JR, Chen X, Kavalali ET, Cannon SC, Houser SR, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle. Science 351, 271–275 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR, STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome S; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup, The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W, HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J, Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK, edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK, Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4288–4297 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C, Chanda SK, Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flati T, Gioiosa S, Spallanzani N, Tagliaferri I, Diroma MA, Pesole G, Chillemi G, Picardi E, Castrignano T, HPC-REDItools: A novel HPC-aware tool for improved large scale RNA-editing analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 21, 353 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cui M, Wang Z, Chen K, Shah AM, Tan W, Duan L, Sanchez-Ortiz E, Li H, Xu L, Liu N, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Dynamic transcriptional responses to injury of regenerative and non-regenerative cardiomyocytes revealed by single-nucleus RNA sequencing. Dev. Cell 53, 102–116.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck III WM, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, Satija R, Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. RNA-seq data generated during this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO series accession numbers GSE210783 and GSE211005. Materials used in this study are available to academic researchers through material transfer agreement with The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center by contacting R.B.-D. and E.N.O.