Key words: Human foodborne trematode, intestinal fluke, liver fluke, lung fluke, paratenic host

Abstract

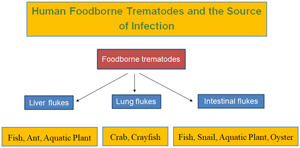

Foodborne trematodes (FBT) of public health significance include liver flukes (Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, O. felineus, Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica), lung flukes (Paragonimus westermani and several other Paragonimus spp.) and intestinal flukes, which include heterophyids (Metagonimus yokogawai, Heterophyes nocens and Haplorchis taichui), echinostomes (Echinostoma revolutum, Isthmiophora hortensis, Echinochasmus japonicus and Artyfechinostomum malayanum) and miscellaneous species, including Fasciolopsis buski and Gymnophalloides seoi. These trematode infections are distributed worldwide but occur most commonly in Asia. The global burden of FBT diseases has been estimated at about 80 million, however, this seems to be a considerable underestimate. Their life cycle involves a molluscan first intermediate host, and a second intermediate host, including freshwater fish, crustaceans, aquatic vegetables and freshwater or brackish water gastropods and bivalves. The mode of human infection is the consumption of the second intermediate host under raw or improperly cooked conditions. The major pathogenesis of C. sinensis and Opisthorchis spp. infection includes inflammation of the bile duct which leads to cholangitis and cholecystitis, and in a substantial number of patients, serious complications, such as liver cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma, may develop. In lung fluke infections, cough, bloody sputum and bronchiectasis are the most common clinical manifestations. However, lung flukes often migrate to extrapulmonary sites, including the brain, spinal cord, skin, subcutaneous tissues and abdominal organs. Intestinal flukes can induce inflammation in the intestinal mucosa, and they may at times undergo extraintestinal migration, in particular, in immunocompromised patients. In order to control FBT infections, eating foods after proper cooking is strongly recommended.

Introduction

Foodborne trematodes (FBT) are defined as trematodes infecting humans, which are transmitted by consumption of foods, globally or locally available (including traditional foods) or those taken rarely or accidentally. In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated the total global number of people infected with FBT at more than 40 million (WHO, 1995). A decade later (in 2005), about 56.2 million people were estimated to be infected with FBT, with 7.9 million having severe sequelae and 7158 people dying mostly from cholangiocarcinoma and cerebral infections (Fürst et al., 2012a). The most recent estimate extrapolated the total global number of people infected with FBT at 74.7 million as of 2015–2016 with 0.2 million new cases annually and 2 million disability-adjusted life years (Fürst et al., 2019; WHO, 2020). However, there are problems of low sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tools as well as possible numerous endemic areas so far undetected, and these global estimates of the FBT burden seem to be much underestimated. Thus, the WHO road map for ‘control of FBT diseases 2021–2030’ recommends critical actions, including the development of accurate surveillance and mapping tools and methods, with information on environmental factors involved in infection, and the promotion of application and awareness of preventive chemotherapy (WHO, 2020).

Taxonomically, the FBTs are highly diverse, and at least 99 species (15 liver flukes, 9 lung flukes and 75 intestinal flukes) have been reported from human infections (Chai et al., 2005; Chai, 2007, 2019; Fürst et al., 2012a; Chai and Jung, 2019, 2020; Cho et al., 2020). Among them, those of greatest public health significance are Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis spp., Fasciola hepatica, Paragonimus westermani, and several species of intestinal flukes, such as Metagonimus spp., Haplorchis spp. and echinostomes (WHO, 1995; Chai and Jung, 2019).

The origin of FBTs may date back to almost 8000 BCE when humans started to switch from a nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a settled, agricultural way of life (Steverding, 2020). However, from the evolutionary point of view, intestinal flukes seem to be the oldest group, which subsequently evolved to parasitize the bile duct and liver (liver flukes) or lungs (lung flukes) in the human body.

The mode of human infection with FBT is closely linked to human behavioural patterns in endemic localities, specifically the methods of food production, preparation and consumption (WHO, 1995). Thus, the epidemiology of FBT infection is determined by ecological and environmental factors related to food and is strongly influenced by poverty, pollution and population growth (WHO, 1995). The infection source, i.e. food, is diverse, including aquatic or semi-terrestrial snails (gastropods and bivalves), fish, crustaceans, water plants, amphibians and reptiles (WHO, 1995; Chai, 2019). Rarely insects and mammals may serve as the source of human infection for some species (Chai, 2019; Chai and Jung, 2019).

The geographical distribution of FBT is almost worldwide. However, as FBT infections are closely related to food habits, they are predominantly found in East Asian and Western Pacific countries where local people prefer to eat various types of foods raw or under improperly cooked conditions (WHO, 1995). This kind of food habit is in most cases traditional and one of the longstanding customs, so it is very difficult to change within a short period of time. Health education targeting schoolchildren is an important strategy for long-term control of FBT infections. Control of infection sources, including intermediate hosts, is very difficult and practically almost impossible. Mass drug administration (MDA) using an effective anthelmintic, such as praziquantel, may be feasible to lower the infection rate of people in endemic communities. However, if reinfection persists, the prevalence would rise again to the previous level. Thus, control of FBT infections by infrequent MDA may be insufficient. Repeated MDA with sustained health education of young people in endemic communities is an ideal control strategy.

In this review, the authors briefly summarized the current status of FBT occurring around the world. The taxonomy and phylogeny of FBT, their life cycles, mode of transmission, epidemiology and geographical distribution, global disease burden, pathogenicity and clinical manifestations, diagnostic problems, anthelmintics used, and control strategies are briefly reviewed.

Liver flukes

At least 15 species of liver flukes are known to cause human infections. They include C. sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, O. felineus, Metorchis conjunctus, M. bilis, M. orientalis, Amphimerus sp., Amphimerus noverca, A. pseudofelineus, Pseudamphistomum truncatum, P. aethiopicum, Dicrocoelium dendriticum, D. hospes, Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica (Table 1) (Chai and Jung, 2019). They can be divided into small liver flukes (C. sinensis, Opisthorchis spp., Metorchis spp., Amphimerus spp., Pseudamphistomum spp. and Dicrocoelium spp.) and large liver flukes (F. hepatica and F. gigantica) according to the size of the adult worms. The first intermediate host is freshwater or brackish water snails, and the second intermediate host is freshwater fish (C. sinensis, Opisthorchis spp., Metorchis spp., Amphimerus spp. and Pseudamphistomum spp.), ants (Dicrocoelium spp.) or aquatic vegetation (Fasciola spp.) (Table 1). The morphological similarity of opisthorchiid eggs to heterophyid as well as lecithodendriid-like fluke eggs frequently poses diagnostic problems in human fecal examinations. Molecular techniques using internal transcribed spacers (ITS) and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1 (cox1) have been used to differentiate the eggs as well as larvae and adults of opisthorchiid and heterophyid flukes (Duflot et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Liver flukes infecting humans with biological, clinical characteristics and geographical distribution

| Group/Species of flukes | First intermediate host (snail) | Second intermediate host | Reservoir host | Major clinical characteristics | Geographical distributiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clonorchis sinensis | Parafossarulus sp. | Freshwater fish | Dog, cat, rat, pig, badger, weasel, camel, buffalo | Cholangitis, cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma | China, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, Russia |

| Opisthorchis viverrini | Bithynia sp. | Freshwater fish | Dog, cat, rat, pig | Cholangitis, cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma | Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar |

| Opisthorchis felineus | Bithynia leachi | Freshwater fish | Dog, cat, fox, chipmunk, beaver, Caspian seal, pig | Cholangitis, cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma | Germany, Greece, Poland, Romania, Italy, Spain, Belarus, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Russia |

| Metorchis conjunctus | Amnicola sp. | Freshwater fish | Dog, cat, wolf, fox, coyote, raccoon, muskrat, mink, fisher | Fever, abdominal pain | Canada, Greenland |

| Metorchis bilis | Bithynia sp. | Freshwater fish | Wolf, white-tailed eagle, muskrat, otter, mink | Unknown | Central and Eastern Europe, Russia |

| Metorchis orientalis | Parafossarulus sp. | Cyprinoid fish | Dog, cat, duck, chicken, goose | Unknown | Japan, China, South Korea |

| Amphimerus sp. | Freshwater snail | Freshwater fish | Duck | Liver fibrosis, cirrhosis | Ecuador |

| Amphimerus noverca | Aquatic snail (?) | Freshwater fish | Dog, wolverine, pig | Periductal fibrosis | India |

| Amphimerus pseudofelineus | Aquatic snail (?) | Freshwater fish (?) | Dog, cat, coyote | Unknown | North and South Americas |

| Pseudamphistomum truncatum | Freshwater snail | Cyprinoid fish | Dog, cat, fox, seal, skunk, mink,otter | Liver pathology | Russia, Europe, North America |

| Pseudamphistomum aethiopicum | Freshwater snail | Fish | Unknown | Small tumour at intestinal wall | Ethiopia |

| Dicrocoelium dendriticum | Various snail species | Ant | Cattle, sheep, ox, deer, marmot, rabbit, goat | Mild cholangitis | Russia, Iran, Java, China, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Tunisia, France, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Hungary, Romania, Armenia, Czech Republic, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and USA |

| Dicrocoelium hospes | Limicolaria sp. | Ant | Cattle, sheep, zebus, goat, monkey | Probably mild cholangitis | DR Congo, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Nigeria |

| Fasciola hepatica | Galba sp. | Aquatic plant | Cattle, sheep, goat, European hare | Obstructive cholangitis, ectopic lesions | Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Peru, Cuba, Egypt, Portugal, France, Spain, Iran, Turkey, South Korea, Japan, China, Thailand, Vietnam |

| Fasciola gigantica | Radix sp. | Aquatic plant | Cattle, sheep, goat, buffalo, camel, pig, horse, domestic animal | Obstructive cholangitis, ectopic lesions | Japan, South Korea, China, Russia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, India, Iran, Sudan, Senegal, Chad, Ghana, Niger, Central African Republic, Tanzania, Kenya, USA (Hawaii) |

The geographical distributions of liver flukes are mostly referred from Chai and Jung (2019).

Species involved

Clonorchis sinensis

Clonorchis sinensis (Cobbold, 1875) Looss, 1907 (the Chinese liver fluke) was first found in the bile passages of a Chinese carpenter in Calcutta, India, and an endemic focus was discovered in south China (Beaver et al., 1984). Eggs of this fluke were also found in the coprolites of human mummies (estimated date; 1647) in South Korea (Seo et al., 2007) and China (date back to the 5th century BCE) (Ye and Mitchell, 2016). This fluke infects the bile duct of humans and animals and can cause inflammation of the bile duct and gall bladder which leads to obstruction of the bile duct, cholangitis and cholecystitis (Chai and Jung, 2019). In severe cases, liver cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma may develop.

Phylogenetic relationships of small liver flukes have been studied using analysis of nuclear (18S rDNA, ITS region and 28S rDNA) and mitochondrial genes (cox1, cox2, cox3, nd1, ATPase subunit 6 and others) (Thaenkham et al., 2012; Besprozvannykh et al., 2018; Saijuntha et al., 2019, 2021; Duflot et al., 2021). Within the genus Clonorchis, there is only a single valid species, C. sinensis. ITS2 can clearly separate C. sinensis, O. viverrini, O. felineus, Amphimerus sp. and Metorchis spp. from the Heterophyidae and Cryptogonimidae flukes (Thaenkham et al., 2012; Besprozvannykh et al., 2018).

Freshwater snails take the role of the first intermediate host for C. sinensis, which includes Parafossarulus manchouricus, P. anomalospiralis and Bithynia fuchsiana (Chen et al., 1994). At least 113 species of freshwater fish, including Pseudorasbora parva, Carassius spp., Cyprinus spp., Zacco spp. and Puntungia herzi, are known to serve as the second intermediate hosts and the source of human and animal infections (Chen et al., 1994; Chai et al., 2005; Rim, 2005). Shrimps were also reported to be a second intermediate host (Chen et al., 1994).

The mode of infection is related to traditional food habits, in particular, the consumption of raw or improperly cooked freshwater fish (Chai et al., 2005). In South Korea, the major type of fish dish responsible for C. sinensis infection is the sliced raw freshwater fish with red pepper sauce (Chai et al., 2005). In southern China and Hong Kong, the major type of fish dish responsible is the morning congee (rice gruel) with slices of raw freshwater fish (Chen et al., 1994), whilst in the Guangdong Province of China, half-roasted or undercooked fish is commonly linked to infection (Chen et al., 1994).

The endemic areas are located mostly in the Far East and East Asia (Chen et al., 1994; Chai et al., 2005; Rim, 2005). In South Korea, a national survey in 2012 reported an egg positive rate of 1.9%, and the number of infected people was estimated to be about 1 million (Korea Association of Health Promotion, 2013). In China, a total of 24 major endemic localities were reported, with 12.5 million infected people nationwide (Chen et al., 1994; Hong and Fang, 2012; Lai et al., 2016). In Taiwan, the prevalence of clonorchiasis was high in some localities; however, the current status is unknown (Chai and Jung, 2019). In Vietnam, northern parts, especially along the Red River Delta, including Haiphong and Hanoi, are well-known endemic areas, with the number of infected people estimated at about 1 million (Rim, 1982a; Chai et al., 2005; Chai and Jung, 2019). In Russia, human infections were reported in the Amur River territory, although the exact prevalence is unknown; however, at least 1 million people are estimated to be infected (Hong and Fang, 2012). The total global number of infected people is estimated at about 20 million (Hong and Fang, 2012), and the number at risk is about 601 million (Garcia, 2016).

The metacercariae excyst in the duodenum, migrate through the ampulla of Vater to the distal biliary ducts, where they begin to lay eggs 3–4 weeks after infection (Beaver et al., 1984). Cholangitis and cholecystitis are the main pathological features in association with secondary bacterial infections (Rim, 1982a). The major histopathological features of the involved bile ducts include irregular bile duct dilatation, glandular hyperplasia, mucin-secreting cell metaplasia, cystic degeneration and periductal fibrosis (Rim, 1982a; 2005; Hong and Fang, 2012). In some patients, biliary cirrhosis and biliary obstruction with blockage of the common bile duct by adult worms or stones, or both, may occur (Beaver et al., 1984). The pathogenesis and pathology depend on the intensity of infection as well as the frequency of continuous reinfection over a period of years and the total length of the infection which can last for 15–20 years or longer (Beaver et al., 1984). The clinical symptoms include jaundice accompanied by transient urticaria and pain at the site of the liver; in heavy infections, weakness, lassitude, epigastric discomfort, paraesthesia, loss of weight, palpitation, tachycardia, diarrhoea and toxaemic symptoms may occur (Rim, 1982a). In chronic stages, suppurative cholangitis, biliary stone, pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma are important complications (Rim, 1982a; Kim, 1984b).

C. sinensis is one of the well-known carcinogenic flukes that can cause cholangiocarcinoma of the bile duct (Rim, 1982a; 2005; Hong and Fang, 2012). The scientific evidence for this was first raised in Hong Kong, an endemic area of clonorchiasis, where it was shown that at least 15% of 200 primary cancers in the liver were induced by infection with C. sinensis (Hou, 1956). In South Korea, close correlations were also found between the cholangiocarcinoma incidence and the prevalence of C. sinensis infection in a southern endemic area (Rim, 1982a; Kim, 1984b).

In known endemic areas, it is relatively easy to diagnose C. sinensis infection through fecal examinations to detect parasite eggs. The daily number of eggs produced per worm was estimated at about 4000 (Rim, 1982a); therefore, the egg detectability in fecal examinations is considerably high. However, in areas previously unknown for FBT infections, the eggs should be differentiated from those of other small liver fluke species (such as O. viverrini, O. felineus, Metorchis spp., or Amphimerus spp.) and also of heterophyid (Metagonimus yokogawai, Heterophyes nocens and various others) and lecithodendriid-like trematode species (Caprimorgorchis molenkampi and others) (Lee et al., 1984; Chai and Lee, 2002; Chai, 2007). Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and radiologic techniques, including ultrasound and CT, are also helpful for diagnosis (Hong and Fang, 2012). Detection of parasite DNA using varied genetic techniques is another method applicable for the diagnosis of clonorchiasis (Hong and Fang, 2012).

Treatment of C. sinensis infection can be done using a potent anthelmintic, praziquantel (Chai, 2013a), or alternatively, albendazole (Table 2). Although such treatment is effective at clearing the infection, fluke-induced bile duct pathology did not recover within 9–12 weeks after praziquantel treatment (Lee et al., 1988; Chai, 2013a). Control strategies include MDA of infected people in endemic areas, environmental sanitation (sterilization of feces and protection of fish ponds from contamination with night-soil), control of snail hosts, and health education to avoid eating raw or improperly cooked freshwater fish (Rim, 1982a).

Table 2.

Drugs used for the treatment of FBT infections

| Anthelmintic drug | Species of FBT | Drug regimen | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Praziquantel | Clonorchis sinensis | 25 mg kg−1 tid for 2 days | Individual treatment |

| 40 mg kg−1 single dose | mass treatment | ||

| Opisthorchis viverrini | 25 mg kg−1 tid for 1–2 days | Individual treatment | |

| 40 mg kg−1 single dose | Mass treatment | ||

| Opisthorchis felineus | 25 mg kg−1 tid for 1 day | Individual treatment | |

| 40 mg kg−1 single dose | Mass treatment | ||

| Dicrocoelium dendriticum | 20–25 mg kg−1 tid for 1–4 days | Satisfactory effects | |

| Paragonimus spp. | 25 mg kg−1 tid for 2 days | Individual and mass treatment | |

| Intestinal flukes | 10–20 mg kg−1 in single dose | Individual and mass treatment | |

| Triclabendazole | Dicrocoelium dendriticum | 10 mg kg−1 single dose | Satisfactory effects |

| Fasciola spp. | 10 mg kg−1 single dose | Repeated after 12–24 h in heavy infections | |

| Paragonimus spp. | 10 mg kg−1 single dose | Repeated after 12–24 h in heavy infections | |

| Niclosamide | Fasciolopsis buski | 40 mg kg−1 daily for 1–2 days | Alcohol should be avoided |

| Heterophyes heterophyes | Total 6 g over 3 alternate days | Repeated if necessary | |

| Metagonimus yokogawai | 100 mg kg−1 daily for 1–2 days | Moderate efficacy | |

| Haplorchis taichui | 40 mg kg−1 single dose | 100% cure rate in experimental mice | |

| Albendazole | Clonorchis sinensis | 1200–1800 mg daily for 3–5 days | Cure rate; 84.6% |

| Opisthorchis viverrini | 800 mg daily for 3–7 days | Cure rare; 60–96% | |

| Dicrooelium dendriticum | 400 mg bid for 7 days | Satisfactory effects | |

| Metagonimus yokogawai | 400 mg daily for 2 days | Cure rate; 61.1% | |

| Fasciola spp. | 1200 mg daily for 7 days | Triclabendazole-resistant cases |

Opisthorchis viverrini and O. felineus

In the genus Opisthorchis, at least 53 nominal species were described (Nawa et al., 2013). Among them, 30 species were recorded from avian hosts, and the remaining 23 were from molluscs, fish, reptiles and mammals (Nawa et al., 2013).

Opisthorchis viverrini (Poirier, 1886) Stiles and Hassall, 1896 (the cat liver fluke) and Opisthorchis felineus (Rivolta, 1884) Blanchard, 1895 (the cat liver flukes) are known to infect humans (Rim, 1982b; Saijuntha et al., 2019). O. viverrini was first discovered in the liver of a civet cat (Felis viverrini) brought from India to France (Miyazaki, 1991). Its first human infection was reported by Leiper in 1911 from the autopsy of two prisoners in Chiang Mai, Thailand (Wykoff et al., 1965). O. felineus was first discovered in the liver of a cat (Miyazaki, 1991), and human infection was first reported by Winogradoff in 1892 in Tomsk, Siberia (Beaver et al., 1984). Eggs of O. felineus were found in the coprolites of humans and dogs in Russia (Slepchenko, 2020). Phylogenetic studies of Opisthorchis spp. have been performed using sequences of nuclear (18S rDNA, ITS region and 28S rDNA) and mitochondrial genes (cox1, cox2, cox3, nd1, ATPase subunit 6 and others) (Besprozvannykh et al., 2018; Saijuntha et al., 2019, 2021; Duflot et al., 2021). Molecular genetic investigations showed that O. viverrini is a species complex ‘O. viverrini sensu lato’, containing two evolutionary lineages with many cryptic species (morphologically similar but genetically distinct species) occurring in Thailand and Laos (Saijuntha et al., 2021).

These flukes can infect the bile duct of humans and animals and can cause hepatobiliary disorders, as in C. sinensis (Chai and Jung, 2019). O. viverrini seems to have a higher potential for inducing cholangiocarcinoma than C. sinensis (Chai et al., 2005; Chai and Jung, 2019). Regarding O. felineus, studies are required for a proper understanding of its carcinogenic potential (Maksimova et al., 2017).

The molluscan intermediate host of O. viverrini is freshwater snails, including Bithynia goniomphalos, B. funiculata, B. siamensis and Melanoides tuberculata (Chai and Jung, 2019). The second intermediate hosts are various species of freshwater fish, i.e. Hampala dispar, Puntius orphoides, P. brevis, P. gonionotus, P. proctozysron and P. viehoever (Rim, 1982b; Chai and Jung, 2019; Chai et al., 2019a). O. viverrini may survive for 10–20 years in the human host (Saijuntha et al., 2019).

With regard to O. felineus, the molluscan host is Bithynia leachi species complex (B. leachi, B. troscheli and B. inflata) distributed in Eastern Europe (Mordvinov et al., 2012). The second intermediate hosts are various species of freshwater fish, including the chub (Idus melanotus), tench (Tinca tinca and T. vulgaris), bream (Abramis brama and A. sapa), barbel (Barbus barbus) and carp (Cyprinus carpio) (Rim, 1982b).

The geographical distribution of O. viverrini, which is determined in close relationship with the distribution of the snail host, is mostly along the Mekong River basin and Indochina peninsula (Chai et al., 2005; Chai and Jung, 2019). In Thailand, O. viverrini is distributed mainly in the north and northeastern regions (Sithithaworn and Haswell-Elkins, 2003), however, the prevalence has been declining since the 1990s (Chai and Jung, 2019). By contrast, in Laos, mainly along the Mekong River, the prevalence has been reported to be high even after the 1990s, with the prevalence being 51–67% among the riparian villagers (Rim et al., 2003; Chai et al., 2007; Nakamura, 2017). In Vietnam, endemic areas are located in southern parts, especially along the Mekong River (Chai and Jung, 2019). In Cambodia, Phnom Penh Municipality, Takeo, Kratie, Stung Treng and Preah Vihear Provinces were reported to be low-grade endemic areas (Yong et al., 2014; Chai and Jung, 2019; Khieu et al., 2019). In Myanmar, a low prevalence of O. viverrini infection has recently been confirmed in a suburban population around Yangon (Sohn et al., 2019). The number of global people infected with O. viverrini is estimated at over 10 million (Sripa et al., 2018), with 80 million at risk for Opisthorchis spp. infections (Garcia, 2016).

O. felineus is known to be distributed from the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain) to Eastern Europe and West Siberia (Mordvinov et al., 2012). Many riverside areas, including the Ob, Irtysh, Ural and Volga Rivers, are the most important endemic localities; the highest prevalence of 20–60% or above was reported in areas of West Siberia (Fedorova et al., 2018). Human infections were recorded previously in Lithuania (before 1901), Poland (before 1937), Romania (before 1957) and Spain (before 1932) but recently no cases seem to occur in these countries (Mordvinov et al., 2012). However, in the last 50 years, human cases have been reported in some European Union (EU) countries, Eastern Europe, and Kazakhstan (Mordvinov et al., 2012; Pozio et al., 2013). In Italy, from 2003 to 2011, there were 8 small outbreaks of O. felineus infection involving a total of 211 people through consumption of raw fillet of the tench (T. tinca) fished from two lakes named Bolsena and Bracciano (Pozio et al., 2013). Thus, O. felineus infection is regarded as an emerging disease in Italy (Pozio et al., 2013). The worldwide estimated number of people infected with O. felineus is 1.2–1.6 million (Saijuntha et al., 2019).

The pathogenesis and pathology as well as clinical symptoms of O. viverrini and O. felineus infections are basically the same as those of C. sinensis infection. Cholangiocarcinoma due to O. viverrini infection accounts for about 15% of all liver cancers and is the second most frequent primary liver cancer worldwide (Saijuntha et al., 2019). The highest incidence of this disease occurs in northern Thailand, where 5000 cases of cholangiocarcinoma are diagnosed annually (Sripa et al., 2012; Saijuntha et al., 2019). In Laos and Vietnam, the precise incidence of cholangiocarcinoma due to O. viverrini infection has been unknown. However, the global ‘Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation’ recently launched a Vietnam Veterans project regarding developing cholangiocarcinoma among the veterans due to their military service in Vietnam in the 1970s (https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/vietnam-veterans/). In endemic areas of O. felineus infection in eastern Europe and Russia, around 400 cases of cholangiocarcinoma occur every year (Hotez and Alibek, 2011). No precise carcinogenic mechanisms of Opisthorchis-induced cholangiocarcinoma have been completely understood (Sripa et al., 2018). However, a two-stage carcinogenic process was proposed; some kinds of carcinogenic substances, including dimethylnitrosamine (DMN), as an ‘initiator’, and parasites, like O. viverrini and O. felineus, act as a ‘promoter’ (Flavell, 1981; Maksimova et al., 2017). This hypothesis has been further developed into a three-stage (multistage) theory, including initiation, promotion and tumour progression (Sripa et al., 2018).

The diagnosis of O. viverrini or O. felineus infection can be done by fecal examinations to detect eggs. The daily number of eggs produced per worm of O. viverrini was estimated at 160–900, considerably less than the figure of 4000 as reported for C. sinensis (Rim, 1982a, 1982b). Serological tests and fecal antigen detection using ELISA (Sripa et al., 2010; Teimoori et al., 2017) and radiologic techniques, including ultrasound (Pungpak et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2018) and CT (Mairiang and Mairiang, 2003), are helpful for the diagnosis of opisthorchiasis and related cholangiocarcinoma. Detection of parasite DNA is another method applicable for the diagnosis of opisthorchiasis (Lovis et al., 2009; Sripa et al., 2010).

Treatment of O. viverrini and O. felineus infection can be done using a potent anthelmintic, praziquantel (Chai, 2013a), or alternatively, albendazole (Table 2). For prevention and control, see C. sinensis section. It is noteworthy that the metacercariae of O. felineus are tolerant to low temperatures, drying and high salt concentration and can be killed only by a high temperature (Pakharukova and Mordvinov, 2016).

Metorchis spp.

Metorchis conjunctus (Cobbold, 1860) Looss, 1899 (the North American liver fluke) is a common parasite of carnivorous mammals, including sledge dogs (causing fatality), in northern Canada (MacLean et al., 1996). Asymptomatic sporadic human infections were reported in Canada since 1945, particularly in aboriginal populations from Quebec to Saskatchewan and the eastern coast of Greenland (Babbott et al., 1961; MacLean et al., 1996). In 1993, an outbreak of a common-source infection with this fluke, with acute clinical symptoms of fatigue, upper abdominal tenderness and pain, low-grade fever, headache, weight loss and anorexia, occurred among 19 Korean immigrants in a river north of Montreal, Canada; the patients consumed wild-caught fish (Catostomus commersoni) that had been undercooked (MacLean et al., 1996). Laboratory findings included high blood eosinophilia and raised liver enzymes (MacLean et al., 1996). However, serious liver diseases have not been reported in human infections.

Metorchis bilis (Braun, 1790) Odening, 1962 is a liver fluke of carnivorous mammals in Central and Eastern Europe and Western Siberia of Russia (Mordvinov et al., 2012). The geographical range of M. bilis considerably overlaps with that of O. felineus (Mordvinov et al., 2012). Human infections with M. bilis were first suggested by demonstrating serum antibodies to M. bilis in 51.3% of 37 patients (37.8% of them reacted against both O. felineus and M. bilis antigens) residing in the Novosibirsk area of Russia (Kuznetsova et al., 2000). Another serological study also demonstrated positive immunoreactivity of 29 (63.2%) of 46 small liver fluke egg-positive patients to both O. felineus and M. bilis antigens and of 3 (7.9%) patients only to M. bilis antigen (Fedorov et al., 2002). Now it seems that infections of both humans and piscivorous vertebrates by M. bilis are under-diagnosed (Sitko et al., 2016).

Metorchis orientalis Tanabe, 1920 is a small liver fluke of piscivorous birds and mammals in Japan, China and South Korea (Chai and Jung, 2019). The first report of human infection was published in Guangdong Province, China (Lin et al., 2001); 4 (4.2%) of 95 residents examined in Ping Yuan County were egg positive and from 2 purged patients a total of 12 adult flukes were recovered (Lin et al., 2001). However, the epidemiological status and potential impact of human infection are unknown (Chai and Jung, 2019). The geographical range of this fluke considerably overlaps with that of C. sinensis (Chai and Jung, 2019).

Amphimerus spp.

Amphimerus sp. (species undetermined) was found to be a human parasitic liver fluke in Ecuador. In 2009, 4 human fecal samples from indigenous Chachi communities along the Cayapas River on the northern coast of Ecuador were found to be positive for opisthorchiid eggs (Calvopiña et al., 2011). Next year, a follow-up survey was conducted in the same communities, and a high proportion, 71 (24%) of 297 fecal samples, of residents, were positive for the same eggs (Calvopiña et al., 2011). The biliary liquid was collected from 4 patients under duodenoscopy, and eggs identical to those found in the feces were found; they were treated with praziquantel followed by purging, and adult worms recovered were identified as a species of Amphimerus (Calvopiña et al., 2011). The patients had a history of consuming smoked or lightly cooked fish; the number of people living in endemic communities is about 24 000 (Calvopiña et al., 2011). A further study reported a very high prevalence of infection with this fluke in domestic cats and dogs living in Chachi communities, Ecuador (Calvopiña et al., 2015). Several species of freshwater fish were confirmed molecularly to have metacercariae of Amphimerus sp. (Romero-Alvarez et al., 2020). Human Amphimerus sp. infection is in most cases asymptomatic; however, it occasionally can cause non-specific generalized symptoms (Cevallos et al., 2017). Liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis occurred in cats and a cormorant infected with this fluke (Cevallos et al., 2017).

Amphimerus noverca (Braun, 1902) Baker, 1911 is a common parasite in the bile duct or pancreatic duct of dogs, wolverines and pigs in India (Beaver et al., 1984; Roy and Tandon, 1992). Human infection with A. noverca was mentioned two times (in 1876 and 1878) in India (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). No further reports on human infections are available.

Amphimerus pseudofelineus (Rodriguez, Gomez Lince et Montalvan, 1949) Artigas and Perez, 1964 was originally reported under the name Opisthorchis guayaquilensis from 18 of 245 humans (based on eggs in feces) and several dogs (based on eggs in feces and adult worms) in a rural area of Ecuador by Rodriguez and colleagues (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Then, Thatcher (1970) transferred this fluke to the genus Amphimerus. This fluke is now known to be distributed in North and South America, probably taking aquatic snails shedding cercariae and fish harbouring encysted metacercariae (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997).

Pseudamphistomum truncatum and P. aethiopicum

Pseudamphistomum truncatum (Rudolphi, 1819) Lühe, 1908 is a species of liver or gall bladder fluke in mammals in Europe and North America (Yamaguti, 1971; Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Its human infection was briefly mentioned in 1928 in Europe (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Later, in the Aleksee District of Tartaria, Russia, 31 human cases were diagnosed among 61 patients who had hepatobiliary system damage and had undergone bile analysis (Khamidullin et al., 1991). Human infections were also detected in five areas along the Volga, Kama and Belaya Rivers in Russia (Khamidullin et al., 1995). The eggs and metacercariae of P. truncatum can be morphologically differentiated from those of O. felineus (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). The pathogenicity in humans is unknown but in otters and mink, P. truncatum can cause cholecystitis (Simpson et al., 2005; Sherrad-Smith et al., 2009).

Pseudamphistomum aethiopicum Pierantoni, 1942 was reported, on one occasion, to have caused a human infection with a small tumour in the intestinal wall (Yamaguti, 1971).

Dicrocoelium dendriticum and D. hospes

Within the genus Dicrocoelium, 5 species are currently recognized to be valid; D. dendriticum (Rudolphi, 1819) Looss, 1899, D. chinensis Tang and Tang, 1978, D. hospes Looss, 1907, D. orientale Sudarikov and Ryjikov, 1951 and D. petrowi Kassimov, 1952 (Manga-González and Ferreras, 2014).

Dicrocoelium dendriticum and Dicrocoelium hospes are known to cause human infections in rare instances. D. dendriticum (the lancet fluke) is a small liver fluke infecting domestic animals in the Northern coasts of Africa, Asia and the Americas (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997; Traversa et al., 2013; Manga-González and Ferreras, 2014). Using mitochondrial nd1 and cox1 sequences, D. dendriticum could be distinguished from D. chinensis and D. hospes (Hayashi et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2021). In human dicrocoeliasis, there may be true (genuine) and false (spurious) infections. The geographical localities where human infections were reported are very wide, and the incidence is undoubtedly underestimated (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997).

The first intermediate host includes more than 90 species of land snails, with Cionella (= Cochlicopa) lubrica as the most important species (Traversa et al., 2013). The cercariae are shed from the snails in clusters of thousands forming a so-called ‘slime ball’ (Traversa et al., 2013). These cercariae are ingested by ants (Formica fusca, F. pratensis and F. rufibarbis) (Traversa et al., 2013). Humans are infected accidentally by swallowing an infected ant together with food (Traversa et al., 2013).

In human infections, the pathogenicity depends on the number of flukes infected and the duration of infection, and in many instances, there may be no notable symptoms. However, a prolonged period of constipation or diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort and epigastric pain may occur (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). The diagnosis is based on the recovery of eggs in feces. However, an egg-positive result does not necessarily indicate a ‘true infection’, and a ‘spurious infection’ should be ruled out.

Serodiagnosis, including immunofluorescence, immunoblot, haemagglutination, complement fixation and ELISA have been introduced (Traversa et al., 2013; Dar et al., 2020). For treatment, albendazole (Magi et al., 2009), praziquantel (Drabick et al., 1988; Khandelwal et al., 2008), triclabendazole (Khandelwal et al., 2008; Ashrafi, 2010) and myrrh (herbal drug in Egypt; Mirazid®) (Abdul-Ghani et al., 2009) showed favourable results (Table 2).

D. hospes is a small liver fluke (more slender and smaller than D. dendriticum) infecting the bile duct and gall bladder of domestic animals in sub-Saharan Africa (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). This liver fluke can also cause genuine and spurious infections in humans (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Two human patients in Sierra Leone (spurious infection was not ruled out) showed hepatitis-like symptoms; one patient had jaundice, and both had elevated bilirubin and transaminase levels (King, 1971). In animals, D. hospes does not seem to cause much damage even in heavy infections (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Diagnosis can be made by the recovery of eggs in feces; however, the eggs are morphologically indistinguishable from those of D. dendriticum and Eurytrema pancreaticum (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). Anthelmintic drugs used against D. dendriticum may have similar effects on D. hospes.

Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica

Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758 (the sheep liver fluke) infects the bile duct of domestic animals, including cattle and sheep, and occasionally humans (Beaver et al., 1984; Mas-Coma et al., 2005; Liu and Zhu, 2013). The parasite life cycle, biology, pathogenesis, pathology, epidemiology and clinical symptoms are similar between F. hepatica and F. gigantica (Chai and Jung, 2019). Hybrid forms between F. hepatica and F. gigantica have been found in Asia (Tang et al., 2021). Humans are accidental hosts (Liu and Zhu, 2013). They are infected through eating aquatic vegetables or raw liver of infected livestock animals (Liu and Zhu, 2013). The history of human infection with Fasciola spp. seems to be very long, since archaeological studies in ancient mummies in Egypt revealed remains of parasites (possibly part of F. hepatica worm) in liver tissue (David, 1997). Sporadic cases of human Fasciola spp. infections (genuine or spurious infection unclear) were reported in Egypt in the 1950s (Kuntz et al., 1958), and an epidemic occurred in France in 1956 (Mas-Coma et al., 2005). An extensive review of human fascioliasis was performed by Chen and Mott (1990) in which 2595 cases from over 40 countries in Europe, Asia, Western Pacific, the Americas and Africa from 1970 to 1990 were analysed. Now human fascioliasis (F. hepatica and F. gigantica) is recognized by the WHO as an important FBT disease with an estimated 2.4 million people infected annually and 180 million at risk in over 61 countries (Haseeb et al., 2002). Large-scale epidemics occurred in France, Egypt and Iran (Parkinson et al., 2011).

In the genus Fasciola, three species are currently recognized; F. hepatica, F. gigantica Cobbold, 1855, and F. nyanzae Leiper, 1910 (Mas-Coma et al., 2009; Rajapakse et al., 2020). Among them, the most common species worldwide are F. hepatica, F. gigantica and their hybrid forms (Mas-Coma et al., 2009, 2019). In Europe, the Americas and Oceania, only F. hepatica is found, whereas both species and their hybrids are commonly found in Asia and Africa (Mas-Coma et al., 2005, 2019). For phylogenetic analyses of Fasciola spp. worms, sequences of nuclear rDNA, including ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and 28S rDNA, and mitochondrial genes, including nd1 and cox1, have been found to be useful and popularly used to differentiate F. hepatica, F. gigantica and the intermediate forms (Mas-Coma et al., 2009, 2018, 2019). Molecular analyses of five Korean Fasciola worms from cattle using ITS-2 and 28S rDNA revealed that one possessed the F. hepatica-type sequence, two F. gigantica-type sequences, and two possessed sequences of both types (Agatsuma et al., 2000). An adult specimen recovered from a Korean male patient revealed F. hepatica ITS-1 genotype (Kang et al., 2014). In China, using ITS-2 sequences to perform RFLP analysis, the Fasciola worms from Sichuan Province represented F. hepatica, those from Guangxi Province represented F. gigantica, and the ones (from sheep) from Heilongjiang Province may represent an ‘intermediate genotype’ (Huang et al., 2004). In Japan, both ITS-1 and ITS-2 were useful to discriminate Fsp1 (F. hepatica), Fsp2 (F. gigantica) and Fsp1/2 (intermediate form), but nd1 and cox1 could not discriminate the intermediate form properly (Itagaki et al., 2005). Also in Europe, ITS-2 showed low variability for both fasciolid species and appeared to furnish valuable information (Mas-Coma et al., 2009). It is also notable that in Asian countries there are aspermic Fasciola flukes that may reproduce parthenogenetically (Itagaki et al., 2005).

A wide variety of freshwater snails that belong to the Lymnaeidae play the role of the first intermediate host (Bargues and Mas-Coma, 2005). In Asia, Europe, Africa and the Western Pacific, Galba truncatula (syn. Lymnaea truncatula) and Austropeplea ollula (syn. Austropeplea viridis) snails are most frequently involved (Bargues and Mas-Coma, 2005; Chai and Jung, 2019). Encysted metacercariae of F. hepatica are found on leaves of aquatic vegetables (watercress, alfalfa, water lettuce etc.) or green vegetation, bark or other smooth surfaces above or below the waterline (Beaver et al., 1984; Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997; Liu and Zhu, 2013). People in Latin America, France and Algeria frequently acquire this disease by eating raw watercress (Nasturtium officinale) (Beaver et al., 1984). In Asia, water bamboo, water caltrop and morning glory were suspected to be important sources of human infections. Recently in South Korea, the water parsley (water dropwort) and its juice have been suspected as the potential source of sporadic human infections (unpublished data). Humans can also be infected by eating raw livers of infected animals containing immature or young worms, and these worms attach to the pharyngeal mucosa and cause pain, bleeding, oedema and dyspnoea, and this condition was once called ‘halzoun’ (Beaver et al., 1984).

F. hepatica is distributed almost worldwide, especially where extensive sheep and cattle raising is popularly done (Liu and Zhu, 2013). Human fascioliasis is one of the major public health problems in northern Africa, western Europe, Andean countries, the Caribbean area and the Caspian areas (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). In South Korea, Japan, China, Thailand and Vietnam, sporadic cases have been reported (Chen and Mott, 1990; Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997; Chai and Jung, 2019). It is of particular note that the highest prevalence (up to 72% by coprological and 100% by serological tests) and intensity ever have been found in some communities in the Northern Bolivian Altiplano (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997).

The pathological changes in the liver and bile duct of infected humans or animals depend primarily on the number of flukes infected (Chen and Mott, 1990), and the pathology in human infections is similar to that reported in animals (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). However, in about 50% of cases, human fascioliasis is asymptomatic probably due to infection with a low number of flukes (Liu and Zhu, 2013). In rare instances (<10% of all patients), ectopic fascioliasis can occur (Beaver et al., 1984; Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997). The pathogenicity of F. hepatica and F. gigantica in humans is not recognizably different, although in sheep F. gigantica was found to be more pathogenic (Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997).

After excystation in the duodenum or jejunum of their definitive host, the metacercariae of F. hepatica migrate through the intestinal wall and peritoneal cavity, and then penetrate into the liver parenchyma through Glisson's capsule and finally reside in the bile duct and gall bladder or go astray to other ectopic locations (Beaver et al., 1984; Liu and Zhu, 2013). They can cause mechanical damage with focal haemorrhage, inflammatory reactions and necrotic lesions (Beaver et al., 1984). Adult worms may live between 9 and 13.5 years in humans (Mas-Coma et al., 2005). Stone formation in the bile duct or gall bladder is frequent, but liver cirrhosis is less common (Mas-Coma et al., 2019). The pathogenesis of ectopic fascioliasis is not fully understood. The ectopic locations include the skin, subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscle, blood vessel, lungs, orbit, ventricles of the brain, stomach, appendix, pancreas, intestinal wall, heart, spleen, epididymis and lymph nodes (Beaver et al., 1984; Chen and Mott, 1990).

The diagnosis of human fascioliasis can be done directly using parasitological techniques and indirectly by immunological tests and radiologic images, including ultrasound, CT, MRI and radioisotope scanning (Mas-Coma et al., 2019).

Triclabendazole is currently the drug of choice for human fascioliasis (Fairweather, 2009; Mas-Coma et al., 2019) (Table 2). A problem related to triclabendazole is the appearance of drug resistance particularly in livestock animals; it was first described in Australia and then in many European and South American countries (Mas-Coma et al., 2019). Praziquantel was also used for human fascioliasis but treatment failure was experienced even at high doses (Mas-Coma et al., 2019). Albendazole, nitazoxanide, Mirazid® and artesunate are alternative drugs for potential use in human and animal fascioliasis (Mas-Coma et al., 2019; Chai et al., 2021a). Infection may be prevented by strict avoidance of consuming watercress and other metacercaria-carrying aquatic plants in endemic areas (Mas-Coma et al., 2019).

Fasciola gigantica Cobbold, 1855 (the giant cattle liver fluke) is a large liver fluke species infecting the bile duct of domestic animals, including cattle and sheep, and occasionally humans (Beaver et al., 1984; Mas-Coma and Bargues, 1997; Liu and Zhu, 2013). In Asia and Africa, F. hepatica, F. gigantica and their hybrid forms are found, but in Europe, the Americas and Oceania, only F. hepatica is found (Mas-Coma et al., 2005, 2019). The parasite's life cycle, biology, pathogenesis, pathology, epidemiology and clinical symptoms are similar to those of F. hepatica (Chai and Jung, 2019). The most important snail host for F. gigantica is Radix auricularia (Liu and Zhu, 2013). The absence of F. gigantica in the New World may be explained by the absence of these snail species (Radix spp.) (Mas-Coma et al., 2009). The metacercariae are encysted on the leaves of aquatic plants (Garcia, 2016).

Lung flukes

Paragonimiasis is a zoonotic disease caused by lung flukes of the genus Paragonimus (Chai and Jung, 2018). As of 1999, more than 50 nominal species had been described in this genus (Blair et al., 1999a; Narain et al., 2010; Doanh et al., 2013a). However, 16–17 of them were synonymized with the others, and the remaining 36 species were regarded as valid or potentially valid (Blair et al., 1999a). Thereafter, five new species were described from Asia and Africa; P. vietnamensis (Doanh et al., 2007), P. pseudoheterotremus (Waikagul, 2007), P. sheni (Shan et al., 2009), P. gondwanensis (Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014) and P. kerberti (Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2015). Among the 41 nominal species (or subspecies), at least 9 are known to cause human infections, including P. westermani, P. africanus, P. gondawanensis, P. heterotremus, P. kellicotti, P. mexicanus, P. skrjabini, P. skrjabini miyazakii and P. uterobilateralis (Table 3) (Chai, 2013b; Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014; Chai and Jung, 2018; Blair, 2019). The lung flukes can cause pulmonary as well as extrapulmonary infections in humans. The global number of people infected with Paragonimus spp. was estimated at about 23 million in 48 countries (mostly in China) with 292 million people at risk worldwide (Blair, 2019).

Table 3.

Lung flukes infecting humans with biological, clinical characteristics and geographical distribution

| Species of flukes | First intermediate host (snail) | Second intermediate host | Reservoir host | Major clinical characteristics | Geographical distributiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paragonimus westermani |

Semisulcospira spp. Juga spp. Melanoides tuberculata Brotia spp. Tarebia granifera |

Crab, crayfish | Dog, cat, pig, leopard, tiger, fox, wolf, opossum, mink, monkey | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | China, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Southeast Siberia (Russia), The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea |

| Paragonimus africanus | Potadoma freethii Melania sp. | Crab | Dog, mongoose, civet, drill, monkey | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | Guinea, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ivory Coast |

| Paragonimus gondwanensis | Unknown | Crab | Cat, civet | Unknown | Cameroon |

| Paragonimus heterotremus | Various snail species | Crab | Dog, cat, monkey, Mongolian gerbil, rabbit | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, India |

| Paragonimus kellicotti | Pomatiopsis spp. | Crab, crayfish | Dog, cat, pig, skunk, red fox, coyote, mink, bobcat | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | Canada, USA |

| Paragonimus mexicanus | Aroapygrus spp. | Crab | Dog, cat, opossum | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Coasta Rica, Panama, Guatemala |

| Paragonimus skrjabini | Various snail species | Crab | Dog, cat, rat, mouse, weasel, monkey | Ectopic lesions | China, Vietnam, northeastern India |

|

Paragonimus skrjabini miyazakii |

Oncomelania sp. | Crab | Dog, cat, marten, weasel, wild boar | Haemoptysis, ectopic lesions | Japan |

| Paragonimus uterobilateralis | Unknown | Crab | Dog, cat, otter, mongoose, swamp, shrew | Haemoptysis, bronchiectasis | Cameroon, Nigeria, Liberia, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Gabon |

The geographical distributions of lung flukes are mostly referred from Chai and Jung (2019).

Species involved

Paragonimus westermani

Paragonimus westermani (Kerbert, 1878) Braun, 1899 (the Oriental lung fluke) was originally reported from the lungs of a Bengal tiger (India) that died in the Zoological Garden in Amsterdam (Beaver et al., 1984). Since then, this species has been reported mainly in Asian countries (Blair et al., 1999a; Narain et al., 2010). Human infections were first found in a Portuguese residing in Taiwan through recovery of adult worm (s) after autopsy in 1880 and also in Japanese patients through detecting eggs from bloody sputum in 1880 and then adult worms in 1883 in Japan (Beaver et al., 1984). Now human infections with this lung fluke continue to occur in Asian countries, including China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Far Southeast Russia, the Philippines and recently India (Chai, 2013b; Singh et al., 2015; Blair, 2019). While human infections may be decreasing in Japan and South Korea, new endemic foci have been detected in several other countries (Yoshida et al., 2019). Morphologically P. westermani differs from other Paragonimus species in the patterns of lobation of the ovary and testes (Miyazaki, 1991). The ovary of P. westermani has 6 simple lobes, whereas that of P. mexicanus or P. ohirai displays many delicate branches (Miyazaki, 1991).

Paragonimus siamensis was described as a new species from experimental cats infected with metacercariae from the freshwater crab Parathelphusa germaini in Thailand (Miyazaki and Wykoff, 1965). Later, this lung fluke was found in animals in Sri Lanka (Kannagara and Karunaratne, 1969), India (Devi et al., 2013) and the Philippines (Yoshida et al., 2019). An adult specimen recovered from a New Guinea native man in 1926 was preserved in School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Australia, and it was restudied and assigned as P. siamensis (Wang et al., 2011). Filopaludina martensi martensi snails are the first intermediate host (Yaemput et al., 1994), and freshwater crabs, including Ceylonthelphusa rugosa, play the role of the second intermediate hosts (Blair et al., 1999a). Recent molecular studies reported that P. siamensis is nested within the P. westermani complex (Devi et al., 2013; Blair, 2019).

Phylogenetic studies revealed that P. westermani is a species complex comprising of two groups; the East Asia group (Japan, South Korea, China and Taiwan) and the Southeast Asia group (Malaysia and the Philippines) based on morphological and molecular data (Blair et al., 1997; Doanh et al., 2009). However, recent discoveries of P. westermani in Thailand (Sugiyama et al., 2007), India (Tandon et al., 2007) and Sri Lanka (Iwagami et al., 2008) provided evidence that P. westermani complex was constructed with more than two groups (Blair et al., 2007).

The first intermediate host is variable species of freshwater snails (Table 3). The second intermediate host is crustaceans, including freshwater crayfish Cambaroides spp. (C. similis, C. dauricus and C. schrenki), Eriocheir spp. crabs (E. japonicus and E. sinensis) and a variety of other crab species belonging to the family Potamidae or Parathelphusidae (Blair et al., 1999a). In China, Taiwan and South Korea, freshwater shrimps (Macrobrachium nipponensis and other species) were also reported as the second intermediate hosts (Blair et al., 1999a). There are several kinds of paratenic hosts, for example, wild boars, bears, wild pigs and rats; in these hosts worms do not mature to be adults but remain at a juvenile stage; they can be an important source of human infection (Miyazaki and Habe, 1976; Shibahara et al., 1992). The egg-laying capacity of Paragonimus worms was reported to be 11 000– 104 000 eggs per day per worm (EPD/worm) in experimental dogs (Yokogawa, 1965).

The principal mode of human P. westermani infection is consumption of raw or improperly cooked (pickled) freshwater crabs or crayfish (Chai, 2013b). In Asian countries, famous dishes causing human paragonimiasis have been known, for example, ‘drunken crab’ in China, ‘Kejang (= sauced crab)’ in South Korea, ‘Oboro-kiro (= crab juice soup)’ in Japan, ‘Goong ten (= raw crayfish salad)’ in Thailand, and ‘Kinuolao (= raw crab)’ in the Philippines (Kim, 1984a; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002). It is of note that freshwater crab or crayfish juice was used in South Korea and Japan for traditional treatment of febrile diseases, such as measles, asthma and urticaria (Kim, 1984a; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002). This kind of practice was formerly an important mode of contracting paragonimiasis, especially in children. Another important mode of infection in Japan is ingestion of raw or undercooked boar meat containing P. westermani metacercariae or juvenile worms (Miyazaki and Habe, 1976; Shibahara et al., 1992; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002). In paratenic hosts, worms do not mature and stay in muscles and tissues; when they were eaten by humans, they could develop into adult worms (Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002; Chai, 2013b).

The geographical distribution of P. westermani is wide, including East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia (including India) and even the Western Pacific (Blair, 2019). Human cases of P. westermani were reported also in the USA (Fried and Abruzzi, 2010; Boland et al., 2011); however, the existence of the life cycle of P. westermani in North America needs to be verified.

When the definitive host, including humans, consumes crab or crayfish meat containing metacercariae, they excyst in the duodenum and penetrate into the intestinal wall; during this process they mature into juvenile flukes (Chai and Jung, 2018). The juvenile flukes enter the inner wall (abdominal muscle) of the abdominal cavity and reappear in the abdominal cavity; they then penetrate the diaphragm and enter the pleural cavity in about 14 days after infection (Yokogawa, 1965). In the pleural cavity, two worms mate and then move to the lung parenchyma where a fibrous cyst called the ‘worm cyst’ or ‘worm capsule’ develops around them (Narain et al., 2010; Chai, 2013b). The two worms exchange sperm and produce eggs within the worm cyst, which accumulate for some time in acute stages but in chronic stages when tissue necrosis occurs around the cyst, the eggs escape from the cyst into small bronchioles (Yokogawa, 1965; Blair et al., 1999a). There are triploid and tetraploid forms of P. westermani which do not produce sperm and reproduce parthenogenetically (Miyazaki, 1991; Terasaki et al., 1995; Agatsuma et al., 2003). The patients may undergo variable clinical types, including pulmonary, thoracic, abdominal, cerebral, spinal and cutaneous paragonimiasis (Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002; Chai, 2013b).

In pulmonary infections, P. westermani worms lie in worm cysts of host origin, 1–2 cm in diameter, within the lung parenchyma (Blair et al., 1999a). The lung lesions can be classified into infiltrative, nodular and cavitating shadow types, or combination of these types (Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002). In early stages of infection, there is no exit from the worm cyst, and eggs as well as excretions, metabolic products and tissue debris may gather progressively within the cyst, which becomes distended, and the cyst wall becomes thick and fibrotic (Yokogawa, 1965). In chronic stages, eggs can be demonstrated in the blood-tinged portion of the sputum (Chai, 2013b). The earliest possible clinical manifestations by day 15 after infection include abdominal pain, fever, chill, fatigue and diarrhoea (Choi, 1990; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002; Procop, 2009). Eosinophilia of up to 25% can occur at 2 months after infection (Choi, 1990; Procop, 2009). In chronic stages, the most common and important manifestations include chronic cough, rusty-coloured sputum (= haemoptysis), chest pain, dyspnoea and crepitation (Im et al., 1993; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002; Procop, 2009). In chest radiographs, cavitating lesions called ‘ring shadows’ or ‘cysts’ are commonly seen (Im et al., 1993). Pleural effusion is frequently seen in Korean and Japanese patients (Im et al., 1993; Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002).

The extrapulmonary migration of Paragonimus worms has been suggested to occur due to several reasons. The most important reason is the complex migration route of the worms (Chai, 2013b). Another reason was suggested to be seeking sexual partners to exchange sperm (Miyazaki, 1991). The brain is the most commonly involved ectopic site, although the mechanisms and route of worm migration to the brain are not well understood (Choi, 1990).

Cerebral paragonimiasis occurs quite commonly in P. westermani infection, about 1% of all paragonimiasis patients (Oh, 1969). Five major symptoms include the Jacksonian type seizure, headache, visual disturbance, motor and sensory disturbances, and 5 major signs are optic atrophy, mental deterioration, hemiplegia, hemi-hypalgesia and homonymous hemianopsia (Oh, 1969). Intracranial haemorrhage can also occur though rare in the incidence (Choo et al., 2003; Koh et al., 2012). In skull radiography, cerebral calcification is the most commonly encountered finding, and temporal, occipital and parietal lobes of the brain are the predilection sites (Oh, 1968b). Compared with cerebral infections, spinal paragonimiasis is relatively rare (Oh, 1968a). The predilection site is extradural areas of the thoracic level (Choi, 1990).

Abdominal paragonimiasis is probably more common than cerebral and spinal infections (Meyers and Neafie, 1976). The affected organs include the abdominal wall (muscle), peritoneal cavity, liver, spleen, pancreas, heart, greater omentum, appendix, ovary, uterus, scrotum, inguinal regions, thigh and urinary tract (Chai, 2013b). Cutaneous and subcutaneous paragonimiasis are very rare compared to pleuropulmonary and other ectopic types (Chai, 2013b). P. westermani can cause abscesses and ulcers in the skin or subcutaneous tissue, but P. skrjabini can cause migrating subcutaneous nodules (Meyers and Neafie, 1976).

Conventional methods to diagnose human Paragonimus infections are microscopic examinations of the sputum or fecal samples for detecting eggs, chest radiography to observe the lung lesions (differential diagnosis needed with tuberculosis and lung cancers), and serological tests, including intradermal test, indirect haemagglutination test, ELISA, and others to detect antibodies (Lee et al., 2003; Sugiyama et al., 2013; Chai, 2013b). Sputum eggs can usually be detected in chronic cases when the worm cyst is ruptured and connected to bronchioles. In children, aged-people or handicapped individuals, sputum is frequently swallowed, and in such cases, eggs could be detected in feces (Chai, 2013b). Among the serological tests, ELISA (such as microplate ELISA and multiple-dot ELISA) is so far the most reliable tool because this assay method shows high sensitivity and high specificity (Lee et al., 2003; Yoshida et al., 2019). Molecular methods, including PCR and DNA sequencing, have become useful for specific identification of Paragonimus eggs and worms (Sugiyama et al., 2013). Other methods, including PCR-RFLP, multiplex PCR, random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), and DNA hybridization, have also been applied for specific identification of Paragonimus (Narain et al., 2010; Sugiyama et al., 2013).

Praziquantel is the drug of choice for treating paragonimiasis (P. westermani and other Paragonimus spp.), including cerebral infections (Chai, 2013b) (Table 2). Rarely, allergic reactions may occur following praziquantel treatment; however, such patients can be successfully treated by desensitization to praziquantel (Kyung et al., 2011). Triclabendazole is a new promising drug for the treatment of pulmonary paragonimiasis (Keiser et al., 2005). However, its efficacy on cerebrospinal paragonimiasis remains to be determined (Chai, 2013b). Prevention of contamination of the crab and crayfish with the cercariae of P. westermani depends on environmental control of surface waters through the elimination of freshwater snails. Long-term health education of young people to avoid eating raw or improperly cooked crayfish or crabs seems to be one of the best ways to prevent P. westermani infection in endemic areas.

Paragonimus africanus

Paragonimus africanus Voelker and Vogel, 1965 was originally described from the mongoose in Cameroon and is now known to be distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa (Narain et al., 2010). Up to 2008, it was estimated that there had been 2295 confirmed cases of human paragonimiasis in Africa mostly due to P. africanus and P. uterobilateralis with the vast majority occurring in Nigeria and Cameroon (Aka et al., 2008; Cumberlidge et al., 2018). Freshwater crabs Liberonautes spp. and Sudanonautes spp. carry the metacercariae (Aka et al., 2008). Its morphological characters include the distinctly larger oral sucker than the ventral sucker, a delicately branched ovary, and highly branched testes which are significantly larger than the ovary (Narain et al., 2010). Uncooked crab meat is an important source of human infection (Aka et al., 2008). Nucleotide sequences of ITS2 and cox1 have been used for specific diagnosis (as P. africanus) of fecal eggs from monkeys (Friant et al., 2015) and humans (Nkouawa et al., 2009). Clinical manifestations are similar to P. westermani infection. Cerebral infection has been suspected but never proved (Aka et al., 2008). Sputum and stool examinations to detect eggs are the main diagnostic procedures.

Paragonimus gondwanensis

Paragonimus gondwanensis Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014 was described as a new species from humans (only eggs) and carnivorous mammals (adult worms) in Cameroon (Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014). This species is morphologically distinct from all other Paragonimus species in having a very short excretory bladder, once used as a character for a different genus, Euparagonimus (Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014). However, molecular data are lacking, and the validity of this species remains to be determined (Rabone et al., 2021). The second intermediate host is freshwater crabs, Sudanonautes africanus (Bayssade-Dufour et al., 2014).

Paragonimus heterotremus

Paragonimus heterotremus Chen and Hsia, 1964 was first discovered from rats in China and is now known to be distributed in China, Indochina peninsula, Sri Lanka and India (Sing et al., 2009; Narain et al., 2010; Yoshida et al., 2019). In 2007, P. pseudoheterotremus was reported as a new species from a cat experimentally infected with the metacercariae in crabs from a mountainous area of Thailand (Waikagul, 1997). Later, however, this species is considered a geographical variation of the P. heterotremus complex, based on molecular studies using ITS2 and cox1 sequences (Sanpool et al., 2013; Doanh et al., 2015; Tantrawatpan et al., 2021). Human infection with P. heterotremus was first identified by the recovery of an adult worm from a 13-year-old boy in Nakorn-Nayok Province, Thailand in 1965 (Miyazaki and Harinasuta, 1966). In the same year, eggs presumed to be of P. heterotremus were detected in the bloody sputum of a patient in Guangxi, China (Zhou et al., 2021). Since then, a lot of human cases have been reported (Miyazaki, 1991; Singh et al., 2009; Doanh et al., 2013a). Freshwater snails, Assiminea sp., Oncomelania hupensis and Neotricula aperta (syn. Tricula aperta), are known to serve as the first intermediate host, and freshwater crabs, including Larnaudia beusekomae, Siamthelphusa paviei and Potamiscus smithianus (Thailand), Potamon flexum and Sinolapotamon patellifer (China), take the role of the second intermediate hosts (Blair et al., 1999a). In adult specimens, the ventral sucker is characteristically small, about a half the diameter of its oral sucker (Narain et al., 2010). The ovary and testes are both delicately branched (Miyazaki, 1991). The pathology and clinical manifestations in P. heterotremus infection is similar to those seen in P. westermani infection. The diagnosis is based on the recovery of eggs in bloody sputum, serology, chest radiography and molecular genetic analysis.

Paragonimus kellicotti

Paragonimus kellicotti Ward, 1908 was originally discovered in a cat and a dog in the USA (Blair et al., 1999a; Procop, 2009). The lobation of the ovary and testes is more complex than in P. westermani (Procop, 2009). Now this species is known to occur in central and eastern parts of the USA and adjacent areas of Canada (Procop, 2009). Beaver et al. (1984) considered the first human case to be a German labourer who worked in the USA in the 1890s and had eaten crayfish. Another case was a Canadian man aged 51 years who had never been outside of Quebec and complained of systemic and pulmonary symptoms (Béland et al., 1969; Coogle et al., 2021). Thereafter, from 1984 until 2017, a total of 20 human cases have been documented (Lane et al., 2009, 2012; Procop, 2009; Fried and Abruzzi, 2010; Coogle et al., 2021). Molecular studies were done on ITS2, cox1 and other genetic loci (Blair et al., 1999b; Fischer et al., 2011; McNulty et al., 2014). Based on ITS2 and cox1 sequences, P. kellicotti was genetically closest to P. macrorchis and P. mexicanus, and then to P. heterotremus, but distant from P. westermani and P. siamensis (Blair et al., 1999b). The draft genome of P. kellicotti has been established and analysed in comparison with those of P. westermani, P. skrjabini miyazakii and P. heterotremus (Rosa et al., 2020). The second intermediate host is the crayfish of Cambarus bartoni, C. robustus and C. virilis, Orconectes propinquus, O. rusticus and Procambarus blandingi acutus, or crabs Geothelphusa dehaani (Blair et al., 1999a). In the USA, frozen or pickled crabs available at markets are suspected to be the source of P. kellicotti infection (Procop, 2009). Pleuropulmonary infection is dominant in P. kellicotti infection, and the most frequent clinical manifestations among 21 North American patients were cough, pleural effusion, fever, fatigue or malaise, weight loss, chest pain, dyspnoea, haemoptysis and eosinophilia (Coogle et al., 2021). Their diagnosis was based on microscopic examinations of sputum, pleural fluid or bronchoalveolar lavage and serological tests using complement fixation test, immunoblot or western blot (Coogle et al., 2021).

Paragonimus mexicanus

Paragonimus mexicanus Miyazaki and Ishii, 1968 (syn. Paragonimus peruvianus) was first described from opossums in Colima, Mexico (Miyazaki and Ishii, 1968). Its characteristic morphology includes a somewhat larger oral sucker than the ventral sucker and a strongly lobed ovary and two testes (Miyazaki, 1991). Metacercariae have no cyst wall (Sugiyama et al., 2013). P. mexicanus is now known to be distributed in Central and South Americas (Blair et al., 1999a). A human case reported by Báez M. and Galán J. in 1961, a 35-year-old Mexican man from whom eggs were detected in lung tissue, was believed to have been due to P. mexicanus infection (Miyazaki and Ishii, 1968). In Costa Rica, 2 human cases (total 4) were reported in 1968 and 1982 (Beaver et al., 1984), and since then, 28 additional cases were described until 2013 (Hernández-Chea et al., 2017). In Ecuador, as early as in 1922, a paragonimiasis patient was found from a coastal region of Chone-Manabi (Calvopiña et al., 2014); this seems to be the first human case infected with P. mexicanus. Thereafter, until 2007, the total number of human infections in Ecuador was 3822 patients (Calvopiña et al., 2014). Using a combination of ITS2, 28S and cox1 sequences, the phylogenetic position of P. mexicanus was analysed, and it was closest to P. heteretremus and then P. macrorchis; however, far from P. westermani and P. siamensis (Devi et al., 2013). However, in Mexico, Ecuador (López-Caballero et al., 2013) and Guatemala (Landaverde-González et al., 2022), several new genetic groups distinct from P. mexicanus (origin; Colima, Mexico) were found based on cox1 sequences. One from Ecuador could be assigned as P. ecuadoriensis Voelker and Arzube, 1979 (once synonymized with P. mexicanus by Vieira et al. in 1992), and two possible new species (or subspecies) groups included one from Chiapas, Mexico and San José, Guatemala and the other from Veracruz, Mexico (Iwagami et al., 2003; López-Caballero et al., 2013). Freshwater crabs, Hypolobocera aequatorialis, H. chilensis and H. guayaquilensis, Pseudothelphusa dilatata, P. nayaritae, P. propinqua and P. terrestris carry the metacercariae (Blair et al., 1999a; Calvopiña et al., 2018). Raw crabs with vegetables and lemon juice is the main infection source for Peruvians (Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002), and ceviche that contains uncooked crustacean meat is an important source for Mexicans (Procop, 2009). Clinically P. mexicanus infection is mostly of the pulmonary type (99.7% of 3822 cases in Ecuador) (Calvopiña et al., 2014). However, cerebral infection with intracerebral haemorrhage can occur (Brenes Madrigal et al., 1982).

Paragonimus skrjabini

Paragonimus skrjabini Chen, 1959 (syn. P. szechuanensis, P. hueitungensis and P. veocularis) was first described from the lungs of viverrid cats in Guangzhou, China (Blair et al., 1999a). Phylogenetic studies revealed that there exists a P. skrjabini complex, which includes P. skrjabini, P. skrjabini miyazakii and P. proliferus (syn. P. hocuoensis) (Doanh et al., 2013b; Yang et al., 2021; Shu et al., 2021a). P. skrjabini is now known to occur in China, Thailand, Vietnam and northeast India (Singh et al., 2006; Doanh et al., 2013b; Blair, 2019). Human infections were reported for the first time in Sichuan and then in Hunan (Blair et al., 1999a). Numerous provinces in China have been found to be endemic for P. skrjabini infection (Zhou et al., 2021). The first intermediate host is freshwater snails, including Assiminea lutea, Tricula spp. and Neotricula spp., and the second host is freshwater crabs, Aprapotamon grahami, Isolapotamon spp., Sinopotamon spp., Tenuilapotamon spp., Stigmatomma denticulatum and Haberma nanum (Blair et al., 1999a; Shu et al., 2021b). Morphologically this species is characterized by profusely branched ovary and testes and an elongated body (Blair et al., 2005; Narain et al., 2010). P. skrjabini more frequently cause cutaneous or cerebral infections than pulmonary lesions, and the skin lesions usually contain juvenile flukes; thus, humans are considered an abnormal definitive host (Nakamura-Uchiyama et al., 2002). Diagnosis is most commonly done by serological tests, including intradermal test and ELISA (Yu et al., 2017).

Paragonimus skrjabini miyazakii

Paragonimus skrjabini miyazakii (Kamo, Nishida, Hatsushika and Tomimura, 1961) Blair et al., 2005 (syn. P. miyazakii) was first described from dogs experimentally fed the metacercariae from a freshwater crab in Japan (Kamo et al., 1961). Human infections were first identified in the Kanton District of Honshu, Japan (Yokogawa et al., 1974). This lung fluke has been found in Shikoku, Kyushu, and the southern half of Honshu, but never from outside of Japan (Miyazaki, 1991). In the University of Miyazaki, Japan, approximately 800 cases (17–49 cases annually) of human paragonimiasis (predominantly by P. westermani and less frequently by P. skrjabini miyazakii) were diagnosed between 1986 and 2018 (Yoshida et al., 2019). Yatera et al. (2015) reviewed 46 P. skrjabini miyazakii patients reported from 1974 to 2009 having pulmonary involvement. Phylogenetic studies revealed that P. skrjabini miyazakii is clearly included among the P. skrjabini complex (Blair et al., 2005; Doanh et al., 2013b; Yang et al., 2021; Shu et al., 2021a; 2021b). Freshwater crabs, Geothelphusa dehaani carry the metacercariae (Blair et al., 1999a). The adult flukes are somewhat elongated with severely branched ovary and testes (Miyazaki, 1991; Blair et al., 2005). Whereas the main clinical features of P. skrjabini miyazakii infection are pleural manifestations with pneumothorax and pleural effusion (in most cases worms cannot mature to become adults in humans), those of P. westermani infection are pulmonary involvement (Yatera et al., 2015).

Paragonimus uterobilateralis

Paragonimus uterobilateralis Voelker and Vogel, 1965 was originally described from the mongoose in Cameroon (Narain et al., 2010), and is now known to be distributed in mid-western sub-Saharan Africa (Blair et al., 1999a). Human infection was first found in Nigeria (Blair et al., 1999a). Up to 2008, there had been 2295 confirmed cases of human paragonimiasis in Africa, which was mostly due to P. africanus and P. uterobilateralis; the vast majority of these cases occurred in Nigeria and Cameroon (Aka et al., 2008; Cumberlidge et al., 2018). Freshwater crabs, Liberonautes spp. and Sudanonautes spp., are the second intermediate hosts (Blair et al., 1999a). This lung fluke is morphologically similar to P. africanus but differs in having similar-sized oral and ventral suckers (Miyazaki, 1991). It has a delicately branched ovary; however, it has moderately branched testes larger than the ovary (Blair et al., 1999a). Uncooked crab meat is an important source of human infection (Aka et al., 2008). Clinical manifestations are similar to P. westermani infection. Cerebral infection has been suspected but never proved (Aka et al., 2008).

Intestinal flukes

Intestinal flukes are taxonomically diverse, including three large groups, namely, heterophyids (family Heterophyidae), echinostomes (family Echinostomatidae), and other groups, including amphistomes, brachylaimids, cyathocotylids, diplostomes, fasciolids, gymnophallids, isoparorchiids, lecithodendriid-like flukes, microphallids, nanophyetids, plagiorchiids and strigeids (Yamaguti, 1971; Chai, 2019; Chai and Jung, 2020). At least 75 different species have been described which infect an estimated 40–50 million people (Chai et al., 2009; Chai and Jung, 2020). Among them, heterophyids include 28 species (14 species are with more than 10 human cases; Table 4), echinostomes include 24 species (16 species; Table 5), and other groups are comprised of 23 species (10 species; Table 6). In this section, 40 species having more than 10 human cases are briefly introduced in the text, and the other 35 miscellaneous species are briefly mentioned in Supplementary Table. Molecular techniques using ITS and cox1 genes have been applied to differentiate eggs, larvae, as well as adults of various heterophyid species (Duflot et al., 2021). Intestinal flukes are easily treated with 10 mg kg−1 single dose of praziquantel or 2 g single dose of niclosamide (Table 2).

Table 4.

Heterophyid intestinal flukes infecting humans with their life cycle and geographical distributiona

| Species of heterophyids | First intermediate host (snail) | Second intermediate host | Reservoir host | Geographical distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagonimus yokogawai | Semisulcospira sp. | Freshwater fish (sweetfish, dace) | Dog, cat, rat, fox, kite | China, India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Russia |

| Metagonimus miyatai | Semisulcospira sp. | Freshwater fish (chub, minnow) | Dog, red fox, raccoon, kite | Japan, South Korea |

| Metagonimus takahashii | Semisulcospira sp. Koreanomelania sp. | Freshwater fish (carp) | Dog, cat, kite, pelican | Japan, South Korea |

| Heterophyes heterophyes | Pirenella conica | Brackish water fish (mullet, goby, tilapia) | Dog, fox, jackal | Egypt, Greece, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Kuwait, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sudan, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirate, Yemen |

| Heterophyes nocens | Cerithidea sp. | Brackish water fish (mullet, goby) | Dog, cat | China, Japan, Korea, Thailand (?) |

| Haplorchis taichui | Melania sp. Melanoides sp. | Freshwater fish (carp, minnow) | Dog, cat, bird | Bangladesh, China, Egypt, India, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, USA (Hawaii), Vietnam |

| Haplorchis pumilio | Melania sp. | Cyprinoid fish silurid fish cobitid fish |

Dog, cat | Australia, Cambodia, China, Egypt, India, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Peru, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, USA, Venezuela, Vietnam |

| Haplorchis yokogawai | Melanoides sp. | Freshwater fish (carp, loach) brackish water fish (mullet) |