Highlights

-

•

WMCs are important brain mechanism in hypertension-related cognitive decline.

-

•

Periventricular or long-range tracts of WM were susceptible areas.

-

•

The effects of WMCs on different cognitive domains have spatial characteristic.

-

•

Meta-analyses confirmed the hypertension-WMCs-cognition link.

Keywords: Hypertension, White matter microstructure, White matter macrostructure, White matter abnormalities, Cognitive decline, Brain

Abstract

Hypertension has been well recognized as a risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia. Although the underlying mechanisms of hypertension-affected cognitive deterioration are not fully understood, white matter changes (WMCs) seem to play an important role. WMCs include low microstructural integrity and subsequent white matter macrostructural lesions, which are common on brain imaging in hypertensive patients and are critical for multiple cognitive domains. This article provides an overview of the impact of hypertension on white matter microstructural and macrostructural changes and its link to cognitive dysfunction. Hypertension may induce microstructural changes in white matter, especially for the long-range fibers such as anterior thalamic radiation (ATR) and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), and then macrostructural abnormalities affecting different lobes, especially the periventricular area. Different regions’ WMCs would further exert different effects to specific cognitive domains and accelerate brain aging. As a modifiable risk factor, hypertension might provide a new perspective for alleviating and delaying cognitive impairment.

1. Introduction

Hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP)/diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 140/90 mmHg by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines (Williams et al., 2018), or SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mmHg in American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines (Whelton et al., 2018), is one of the highly prevalent diseases among the aged population (Cohen and Townsend, 2011). Hypertension is estimated to affect 31.1% of adults (1.39 billion individuals) worldwide (Mills et al., 2020, Mills et al., 2016) and is predicted to reach global prevalence of around 1.56 billion by 2025 (Kearney et al., 2005). Hypertension has increasingly become a critical scientific and public health priority, as it increases the risks of stroke (Seshadri et al., 2001), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Shah et al., 2012, Ungvari et al., 2021) and vascular dementia (Sharp et al., 2011) and accounts for 10.4 million fatalities each year (Stanaway et al., 2018, Unger et al., 2020). The deleterious effect of hypertension on cognitive function has also been well established (Gorelick et al., 2011, Hamilton et al., 2021, Iadecola et al., 2016).

Individuals with hypertension perform worse in multiple cognitive domains, including executive function (EF), processing speed (PS) and memory, than normotensive individuals, as evidenced by multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Bucur and Madden, 2010, Iadecola et al., 2016, Walker et al., 2017). Particularly, longitudinal studies have shown that the duration and trajectory of blood pressure (BP) over time in elderly individuals are significant for cognitive function later in life (Power et al., 2013). Although the mechanisms underlying hypertension-related cognitive impairment are biologically complex and not fully investigated, age-related structural alterations in white matter (WM), a common early event in hypertension, appear to play a key role in this respect (Haight et al., 2018, Hajjar et al., 2011, Luo et al., 2019, Nagai et al., 2010, Ungvari et al., 2021).

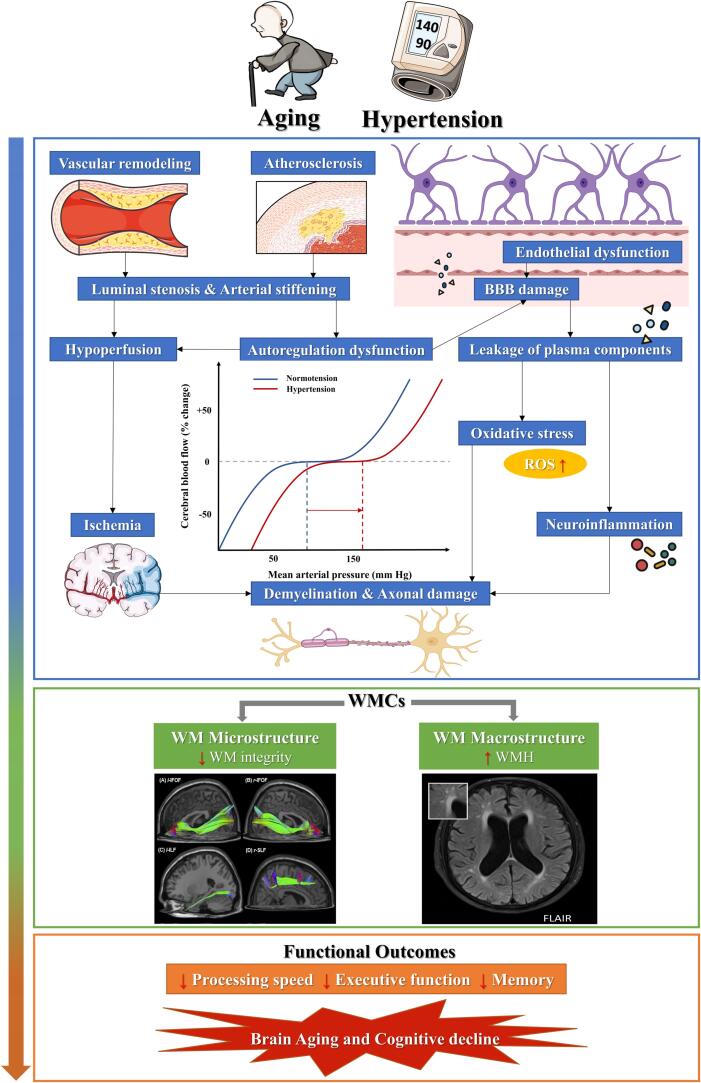

White matter changes (WMCs), including low microstructural integrity (Luo et al., 2019, Power et al., 2017) and subsequent WM macrostructural damage (white matter hyperintensities [WMHs] or white matter lesions [WMLs]) (Scharf et al., 2019, Zhao et al., 2019), are common brain lesions related to hypertension. Not only hypertensive patients but also increased BP could lead to WM damage (Alateeq et al., 2021). Compared with gray matter, the arrangement of the brain’s vasculature makes WM particularly susceptible to the deleterious effect of hypertension (Iadecola, 2013). Hypertension induces several key cellular and molecular mechanisms, including endothelial dysfunction, blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, which are common to the pathological processes of WMCs (Faraco and Iadecola, 2013, Jorgensen et al., 2018, Lin et al., 2017, Ungvari et al., 2021, Wardlaw et al., 2015).

Over the past 10 years, evidence has indicated that cerebral WMCs could be regarded as a silent early marker of advanced hypertension pathology (Gronewold et al., 2021, Sierra, 2014) as well as an important prognostic factor for cognition and dementia (Debette and Markus, 2010, Hu et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2018). Pathologic changes in WM have frequently been found to be correlated with cognitive decline in hypertensive individuals (Chesebro et al., 2020, Guevarra et al., 2020, Jiménez-Balado et al., 2019, Luo et al., 2019). Therefore, focusing on WM may be beneficial to understanding the pathophysiological mechanism of hypertension-induced cognitive disorder.

Here, we review the detrimental impact of hypertension on WM and consequent cognitive function. We first examine the epidemiology of hypertension, and then synthesize recent findings of the associations between hypertension and cognitive function in older adults. The relationship between hypertension and WMCs as well as its possible pathobiological mechanisms are also summarized. We then focus on providing an overview of what is known about the influence of hypertension-related WMCs on cognitive function. Finally, we also summarize the findings and discuss the knowledge gaps and future directions for advancing this field.

2. Epidemiology

The global prevalence of hypertension is high and is expected to continue to rise owing to the aging population and increased lifestyle-related risk factors (Mills et al., 2020). According to a recent survey, in the USA, the prevalence of hypertension significantly increases with age, and approximately 74.5% of adults aged ≥ 60 years are affected by hypertension (Ostchega et al., 2020). In China, a total of 74.7% of the elderly aged 65–74 years and 78.7% of the elderly aged 75 years and over have hypertension (Wang et al., 2018). Despite the fact of high prevalence of hypertension, the rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension remain suboptimal (Fryar and Zhang, 2017, Mills et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2018).

Hypertension has been identified as a well-known risk factor for cognitive dysfunction and dementia (Iadecola, 2014, Iadecola and Gottesman, 2019, Kennelly et al., 2009). According to the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, compared with normotension, the risk of dementia for later age among mid-life hypertensive patients (SBP ≥ 160 mmHg) was 4.8 (Launer et al., 2000). Worldwide, it’s estimated that around 5% of AD cases (1.7 million) are attributable to mid-life hypertension (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011). Reducing the prevalence of middle-aged hypertension by 10% or 25% could lower AD cases by > 160,000 or 400,000, respectively. In the USA, approximately 8% of AD cases (> 425,000) may be caused by mid-life hypertension (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011). In a cross-sectional study in China of 46,011 adults aged ≥ 60 years, the prevalence of dementia was estimated to be 6.0%, and 62.6% of those dementia patients also had hypertension (Jia et al., 2020).

3. Hypertension and cognitive decline

The negative effect of hypertension on cognitive outcomes in different abilities has been confirmed by many large cohort cross-sectional and longitudinal studies across many different regions and age groups, including the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) (n = 1215, aged ≥ 40 years) (Sun et al., 2021), Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study (n = 13476, aged 45–64 years; n = 4761, aged 45–65 years) (Gottesman et al., 2014, Walker et al., 2019), ELSA-Brasil Cohort Study (n = 7063, aged 35–74 years) (de Menezes et al., 2021), and China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) (n = 6732, aged ≥ 45 years) (Wei et al., 2018). For example, the NOMAS found that BP was negatively associated with EF and PS both cross-sectionally and longitudinally at a 5-year follow-up (Sun et al., 2021). Sustained hypertension in mid-life to late-life can further increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a subtle state of cognitive disruption that precedes the onset of dementia, as well as subsequent dementia (Reitz et al., 2007, Walker et al., 2019).

Rather than a linear correlation, several studies discovered a U-shaped connection between BP and cognitive impairment (Gao et al., 2021, Lv et al., 2017, Taylor et al., 2013). Both extremes of BP spectrum were accompanied by cognitive decline. The Southall and Brent Revisited (SABRE) study indicated that both low and high BP in old age were responsible for cognitive impairment after 20 years (Taylor et al., 2013), highlighting the importance of maintaining at an optimal BP level in late life to minimize risk of cognitive dysfunction (Gao et al., 2021). In fact, Lv et al. (2017) determined that the cutoff points for SBP and DBP with the lowest risk of cognitive impairment in the elderly (aged ≥ 65 years) were 141 mmHg and 85 mmHg, respectively.

Although the treatment and control of hypertension seems to be beneficial to a more favorable cognitive trajectories (Zhang et al., 2022), recent research has yielded inconsistent null, beneficial or detrimental effects of more aggressive BP control target on cognition or dementia risk, compared with the standard target. Different studies or guidelines have conflicting recommendations on what constitutes standard and intensive BP targets. Zhang et al. (2022) (n = 13974, aged ≥ 45 years) or Fan et al. (2023) (n = 6501, aged 60–80 years) found that no disprity in the risk for cognitive impairment between intensive control (SBP < 120 or 130 mmHg) and standard control (SBP < 140 or 150 mmHg). Similarily, a meta-analysis including 16 publications with 17,396 participants also indicated that there was no significnat relations between intensive BP reduction and cognitive function, incidence of dementia or MCI (Dallaire-Théroux et al., 2021). On the other hand, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension (MIND) study (n = 9361, aged ≥ 50 years) indicated the aggressive strategy of target SBP < 120 mmHg did reduce the incidence of MCI or dementia compared to standard treatment (SBP < 140 mmHg) (Jiang et al., 2023, Williamson et al., 2019), suggesting intensive care may be beneficial. However, possible adverse effects of intensive strategies (SBP ≤ 120 mmHg) were noted in some vulnerable subgroups. In older adults with hypertension and comorbid depression, it was found to be related to an increased risk of AD (n = 4505, aged ≥ 50 years) (Yeung et al., 2020), and in the oldest-old population, this strategy may lead to a faster decline in cognition (n = 1015, aged 70–90 years; n = 570, aged ≥ 85 years) (Lennon et al., 2021, Streit et al., 2018).

Isolated systolic hypertension (ISH, elevated SBP alone), and isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH, elevated DBP alone), are also prevalent among the elderly (Verdecchia and Angeli, 2005). Considering different BP parameters such as SBP, DBP, pulse pressure (PP) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) reflect different aspects of BP (Gutierrez et al., 2015), several studies have investigated the independent relationship of these BP indexes with cognitive decline and dementia risk, but showed inconsistent results. For example, certain studies established that SBP, DBP, MAP, and PP were all related to cognitive function (Kritz-Silverstein et al., 2017, Levine et al., 2019, Ogliari et al., 2015). Nevertheless, other research reported relative importance of different BP components in cognition may vary. A cross‐sectional study in China (n = 6732, aged ≥ 45 years) indicated that SBP and PP may show a greater impact on cognition than DBP as people age (Wei et al., 2018), while a cohort study of Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS, n = 19836, aged ≥ 45 years) suggested that the cross‐sectional relation between cognitive status and BP indexes was only observed for DBP but not for SBP and PP (Tsivgoulis et al., 2009). Data from the CHARLS (n = 7144, aged ≥ 65 years) indicated that each 1 mmHg rise in BP was associated with a 1.2%, 1.8%, and 2.1% higher risk of cognitive impairment for SBP, DBP and MAP, but not for PP (Lv et al., 2017). Therefore, further studies examining subgroups of patients with different hypertensive statuses are still warranted.

Regarding the cognitive domains most likely to be affected by hypertension, many studies have reported that these domains include EF and information PS (Hajjar et al., 2011, Reitz et al., 2007, Veldsman et al., 2020, Walker et al., 2017). However, some other studies indicated that hypertension mainly predicted a faster decline in global cognition and memory (de Menezes et al., 2021, Euser et al., 2009, Waldstein et al., 2005). It's important to note that the association between hypertension and cognitive decline seems to mediated by the changes of WM (Hajjar et al., 2011, Luo et al., 2019). WMCs are earlier events for hypertension (Haight et al., 2018, Jennings et al., 2020, Ter Telgte et al., 2018) that could effectively predict cognitive outcomes (Prabhakaran, 2019, Silbert et al., 2009, Verdelho et al., 2010, Wakefield et al., 2010). The WM alterations were increasingly found to underline the cognitive disorder in hypertensive individuals (Chesebro et al., 2020, Li et al., 2016, Murray et al., 2012). Therefore, focusing on WM health may help us obtain deeper insights into the pathophysiological mechanism of hypertension-related cognitive deficits.

4. Hypertension and white matter changes

Hypertension increases the risk of changes in cerebral WM, including early reduction of microstructural integrity of WM and subsequent macrostructural WMHs.

4.1. Hypertension and WM macrostructural changes

As for macrostructural WMHs, it refers to diffuse regions of elevated hyperintensity signals on proton density magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2-weighted MRI (De Groot et al., 2002, Prins and Scheltens, 2015). WMHs detected by neuroimaging represent a set of pathologic changes of the small arteries, arterioles, and capillaries in the brain (Pantoni, 2010). WMHs are equivalent to leukoaraiosis or WMLs, and can be divided into periventricular WM (PVWMHs) and deep WM (DWMHs), which have distinct underlying pathophysiology (Armstrong et al., 2020, Griffanti et al., 2018).

WMHs are very common among hypertensive patients over the age of 65 (Ungvari et al., 2021). The prevalence of subcortical WMHs and PVWMHs increases by 0.2% and 0.4% per year of age, respectively (de Leeuw et al., 2001). Compared with normotensive individuals, the relative risk of subcortical WMHs and PVWMHs in participants aged 60–70 years with hypertension for < 20 years was 6.2 and 1.9, respectively (de Leeuw et al., 2002). For participants with the same age but with hypertension for > 20 years, the relative risks of subcortical WMHs and PVWMHs were 24.3 and 15.8, respectively (de Leeuw et al., 2002).

The positive relationship between hypertension and WMHs accumulation has been well established by many studies from different regions and including subjects with different age ranges, such as the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (n = 554, aged ≥ 60 years) (Scharf et al., 2019), Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (n = 395 twins, aged 56–66 years) (Fennema-Notestine et al., 2016), and Study of Health in Pomerania within a larger population (n = 2367, aged 20–90 years) (Habes et al., 2016). A meta-analysis including 52 studies with 343,794 participants also showed that the association between higher BP and WMHs was not limited to hypertensive patients (Alateeq et al., 2021). For each standard deviation increase in SBP over 120 mmHg, WMHs would increase by 11.2%.

Hypertension-related WMHs also show spatial distribution properties. Compared with DWMHs, PVWMHs demonstrated a greater connection with hypertension (Gupta et al., 2018, Henskens et al., 2009). The lobar distribution of WMHs volumes in hypertensive individuals were also discovered to cross different lobes, including the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, occipital lobe, and insular lobe (García-Alberca et al., 2020, Zhao et al., 2019).

Besides, the relationship between hypertension and WMHs seems to be affected by the treatment status. It has been reported that appropriate antihypertensive treatment would be beneficial to slower progression or reduced risk of WMLs (de Leeuw et al., 2002, Dufouil et al., 2001, Godin et al., 2011). For instance, low-dose rosuvastatin, which had an effect on BP, could postpone WMHs progression and cognitive decline among antihypertensive patients (Zhang et al., 2019). However, there are conflicting results in the literatures reporting about intensive BP control and WMHs. For example, a 4-year follow-up study indicated that when receiving excessive control of BP (SBP reduction > 35 mmHg), it’s not good for the alleviation of WMHs and cognitive dysfunction in elderly hypertensive patients (n = 294, aged ≥ 80 years) (Peng et al., 2014). However, a meta-analysis including 7 studies with 2693 patients (median age = 67.1 years) found that intensive BP lowering could prevent WMHs progression, and this effect was related to BP control magnitude (Lai et al., 2020). Majority of current research including data from the SPRINT MIND (n = 670, aged > 50 years, target SBP < 120 mmHg), the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) blood pressure trial (n = 199, aged > 75 years, target SBP < 130 mmHg), and the Intensive vs Standard Ambulatory Blood Pressure Lowering to Prevent Functional Decline in the Elderly (INFINITY) trial (n = 2977, aged ≥ 55 years, target SBP < 120 mmHg) have all agreed on the protective effect of intensive BP control on WMHs progression and that the negative effect of this strategy may be related to a consolidated damage already existing in elderly brains (Kjeldsen et al., 2018, Murray et al., 2017, Nasrallah et al., 2019, White et al., 2019).

However, targeting SBP that is below 110 mmHg (known as hypotension) would exert negative impact on hypertensive patients. In fact, > 8% of treated hypertensive patients experience hypotension, which can induce hypoperfusion and ischemia of the WM, leading to the occurrence of WMLs (Divisón-Garrote et al., 2016, Nakao et al., 2019, van Dijk et al., 2004). A study by Kim et al. (2020) also suggested that low SBP is associated with higher WMHs among those with a history of hypertension. Hypotension was thought to be related to deficient regulation of cerebral blood flow and hypertension individuals were more prone to hypotension as a result of their autoregulation dysfunction (de la Torre, 2012, de la Torre, 2000, Shekhar et al., 2017). While the brain can compensate for slight reductions of BP below the lower limit of autoregulation by increasing the extraction coefficient of oxygen from the blood, further reductions may cause irreversible brain damage. Therefore, it’s important to monitor BP treatment target to minimize the risk of WMCs (Duschek and Schandry, 2007).

There are several key factors that are related to the development of WM pathology in hypertension. Longstanding high BP has significant deleterious impact on cerebrovascular structure including negative vascular remodeling and atherosclerosis (Ji et al., 2019, Martinez-Lemus et al., 2009, Scuteri et al., 2011), accompanied by luminal stenosis, increasing vascular resistance and arterial stiffening (Faraci, 2011, Faraco and Iadecola, 2013, Mulvany, 2012, Pantoni, 2010). The structural vascular alterations may be the major causes of cerebral vascular autoregulation dysfunction (Lin et al., 2017, Scuteri et al., 2011) and leave the brain more susceptible to hypoperfusion (Faraco and Iadecola, 2013, Pantoni, 2010). WM is located in the watershed area of arterial blood supply, which is particularly vulnerable to hypoperfusion or ischemic injury (Lin et al., 2017, Yao et al., 1992). Besides, chronic hypertension also promotes endothelial cell damage (Toth et al., 2013) and BBB disruption (Bailey et al., 2011, Fan et al., 2015, Setiadi et al., 2018), thus causing the leakage of proteins, fluids and other plasma components and facilitating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation (Petersen et al., 2018, Toth et al., 2013, Zlokovic, 2011). These molecular processes have a critical role in demyelination and WMHs formation (Wardlaw et al., 2013).

4.2. Hypertension and WM microstructural changes

4.2.1. Low white matter integrity

Apart from macrostructural WMCs, hypertension was presumed to affect subtle differences in WM microstructural integrity, which could lead to reduced connectivity between cortical regions and attendant cognitive impairment (Luo et al., 2019, Suzuki et al., 2017). Unlike WMHs, which are apparent on structural MRI, changes in the microstructure cannot be observed using structural MRI, but rather can be detected by diffusion MRI (Haight et al., 2018). Reduced WM microstructural alterations could typically be reflected by changes of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics such as fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) (Bennett et al., 2010), or some novel markers such as peak width of skeletonized mean diffusivity (PSMD) (Baykara et al., 2016) and free water (FW) (Pasternak et al., 2009), as well as diffusion spectrum imaging (DSI) measures such as mean generalized fractional anisotropy (mGFA) (Tuch, 2004). Additionally, WMHs may markedly increase in late life, while reduced microstructural integrity may be more common and more associated with mid-life hypertension (Haight et al., 2018). Therefore, WM microstructural integrity may precede the emergence of WM macrostructural change, which may be more sensitive in detecting subtle cognitive alterations and helpful for identifying the effect of hypertension on the brain (Haight et al., 2018, Power et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2015).

The relationship between hypertension and reduced integrity of WM has been consistently reported in many previous cohort studies from different regions and including subjects with different age ranges, such as the ARIC Study (n = 1851, aged 44–65 years) (Power et al., 2017), a US cohort study of very old black and white adults (n = 311, aged 70–79 years) (Rosano et al., 2015) and the Vietnam-Era Twin Registry (n = 316, aged 56.7–65.6 years) (McEvoy et al., 2015). For example, data from the ARIC Study suggests that hypertension in both mid-life and late-life are associated with worse late-life WM microstructural integrity (Power et al., 2017). This association could be detected even in prehypertension (Suzuki et al., 2017). While most studies have examined this relation using traditional metrics such as FA and MD, there is a growing interest in using new imaging metrics such as the measurement of extracellular water volume, known as FW. Recent studies have found that elevated SBP or DBP was related to higher FW, which is a more sensitive biomarker of WMCs and relates to poor cognition (Andica et al., 2023, Coffin et al., 2022, Maillard et al., 2017). One plausible hypothesis is that hypertension-induced BBB dysfunction allows the infiltration of extra water into brain’s interstitial space and disturbs WM milieu (Maillard et al., 2017).

The long-range fiber bundles were found to be more susceptible to hypertension, such as the anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), forceps minor, inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) (Carnevale et al., 2018, Luo et al., 2019, Maillard et al., 2012, Suzuki et al., 2017).

There are yet mixed results concerning whether BP control can prevent reduced WM integrity progression. The RUN DMC Study including 499 subjects aged 50–85 years suggested that antihypertensive therapy could reduce the risk of reduced WM integrity (Gons et al., 2012, Gons et al., 2010). However, the results from a cohort of 311 adults aged 70–79 years and Vietnam Era Twin Registry cohort of 316 men aged 56.7–65.6 years indicated that the relationship between hypertension and WM integrity was independent of antihypertensive medication use (McEvoy et al., 2015, Rosano et al., 2015). The disparity between different studies might be related to participants’ varied demographic characteristics and more longitudinal research is also required to learn more about the effect of hypertensive treatment on alterations in WM microstructure.

The segregated relation between different components of BP and WM macro- and microstructural disruptions have also been examined by some studies. As for the WMHs volume, the Northern Manhattan Study (n = 1009, aged > 50 years) found that it's influenced by the indicators of steady flow (ie., DBP and MAP), rather than indicators of pulsatile pressure (ie., SBP and PP) (Gutierrez et al., 2015). A meta- analysis including 12 studies with 9847 participants also revealed that the relationship between DBP and WMHs is closer than that of SBP (Zhang et al., 2020). Regarding the microstructural WM damage, a cross-sectional UK Biobank cohort study (n = 38347, mean age = 64.12 years) indicated that it's affected by both steady (MAP) and pulsatile components (PP) of BP (Wartolowska and Webb, 2022). It's also important to note that isolated hypertension (ISH or IDH) seems to be less detrimental to both macro- and micro-WM pathologies and cognitive decline than combined systolic-diastolic hypertension, indicated by a recent UK Biobank study (n = 29775, mean age = 63 years) (Newby et al., 2022).

4.2.2. Impaired white matter network connectivity

In addition to the low WM microstructural integrity, hypertensive patients were also found to show reduced connectivity of WM networks. Whole-brain WM network connections can be constructed by DTI-based fiber tractography (Gong et al., 2009, Hagmann et al., 2008) and the efficiency of information transmission between cortical regions can be reflected by WM network properties, such as global efficiency and shortest path length (Yu et al., 2019). According to a Chinese study, hypertensive patients (n = 39, mean age = 65.08 years) showed impaired frontoparietal WM connectivity (Li et al., 2016). The relationship between hypertension and reduced global efficiency of the WM network was also confirmed in a larger population from the UK Biobank comprising 19,346 individuals (mean age = 62.6 years) (Shen et al., 2020).

5. White matter changes and cognitive decline in hypertension patients

5.1. Influence of hypertension-related WM macrostructural changes on cognition

Hypertension and WMHs are mutually associated risk factors for cognitive deterioration. There is accumulating evidence indicating that WMHs may mediate the relationship between BP and cognitive function (Chesebro et al., 2020, Hajjar et al., 2011, Murray et al., 2012).

The effect of WMHs on cognition might differ according to the location. Different classifications of WMHs locations, either divided into PVWMHs versus DWMHs or separated into lobes, exist. WMHs are spreading in a specific pattern from the periventricular areas among older adults (Zeng et al., 2020). Compared with DWMHs, PVWMHs, the area more susceptible to hypertension (Henskens et al., 2009), showed stronger association with a wider range of cognitive components and predicted a faster cognitive decline (de Groot et al., 2000, Kloppenborg et al., 2014). Hypertensive patients with PVWMHs presented a significant decrease in PS (van den Heuvel et al., 2006, Zhang et al., 2021), EF (Jiménez-Balado et al., 2019, Uiterwijk et al., 2017, Zhang et al., 2021) and memory (Chesebro et al., 2020) (Table 1). DWMHs were found to be only associated with declining performance in the domain of EF (Uiterwijk et al., 2017) or attention (Jiménez-Balado et al., 2019). This may be because PVWMHs mainly contain a high density of long-range fiber tracts and disrupt long cotico-subcortical association fibers, while DWMHs may affect cortico-cortical connections (De Groot et al., 2002, Qi et al., 2019).

Table 1.

The corresponding effect of hypertension-related WM macrostructural changes (periventricular versus deep WMH) on specific cognitive domains.

| Cognitive Alterations | WM Macrostructural change | Study | No. of hypertensives | Age: Average | Cognitive tests | Effect size β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | PVWMH | Zhang et al., 2021 | 398 | 72 | Color naming subtest of SCWT, Neutral color subtest of SCWT, SDMT | -0.131 |

| EF | PVWMH | Zhang et al., 2021 | 398 | 72 | Backward digit span, CVFT, Interference subtest of SCWT | -0.130 |

| Jiménez-Balado et al., 2019 | 345 | 65 | Initiation/Perseveration and Conceptualization subscales of DRS-2 | -0.564 | ||

| Uiterwijk et al., 2017 | 128 | 58.6 | Interference score of SCWT, Category and letter verbal fluency, TMT B-A, Backward digit span and Letter-number sequencing subtests of WAIS-III | 0.290 (0.100 to 0.490) | ||

| DWMH | Uiterwijk et al., 2017 | 128 | 58.6 | Interference score of SCWT, Category and letter verbal fluency, TMT B-A, Backward digit span and Letter-number sequencing subtests of WAIS-III | 0.490 (0.180 to 0.800) | |

| Memory | PVWMH | Chesebro et al., 2020 | 258 | 63.9 | SRT | -4.09 (-8.72 to -0.18) |

| Attention | DWMH | Jiménez-Balado et al., 2019 | 345 | 65 | Attention subscale of DRS-2 | Not reported |

Notes: PS: processing speed; EF: executive function; PVWMH: periventricular white matter hyperintensities; DWMH: deep white matter hyperintensities; SCWT: Stroop Color Word Test; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; CVFT: Category Verbal Fluency Test; DRS-2: Dementia Rating Scale–second version; TMT B-A: Trail Making Test B-Trail Making Test A; WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Third Edition; SRT: Selective Reminding Test.

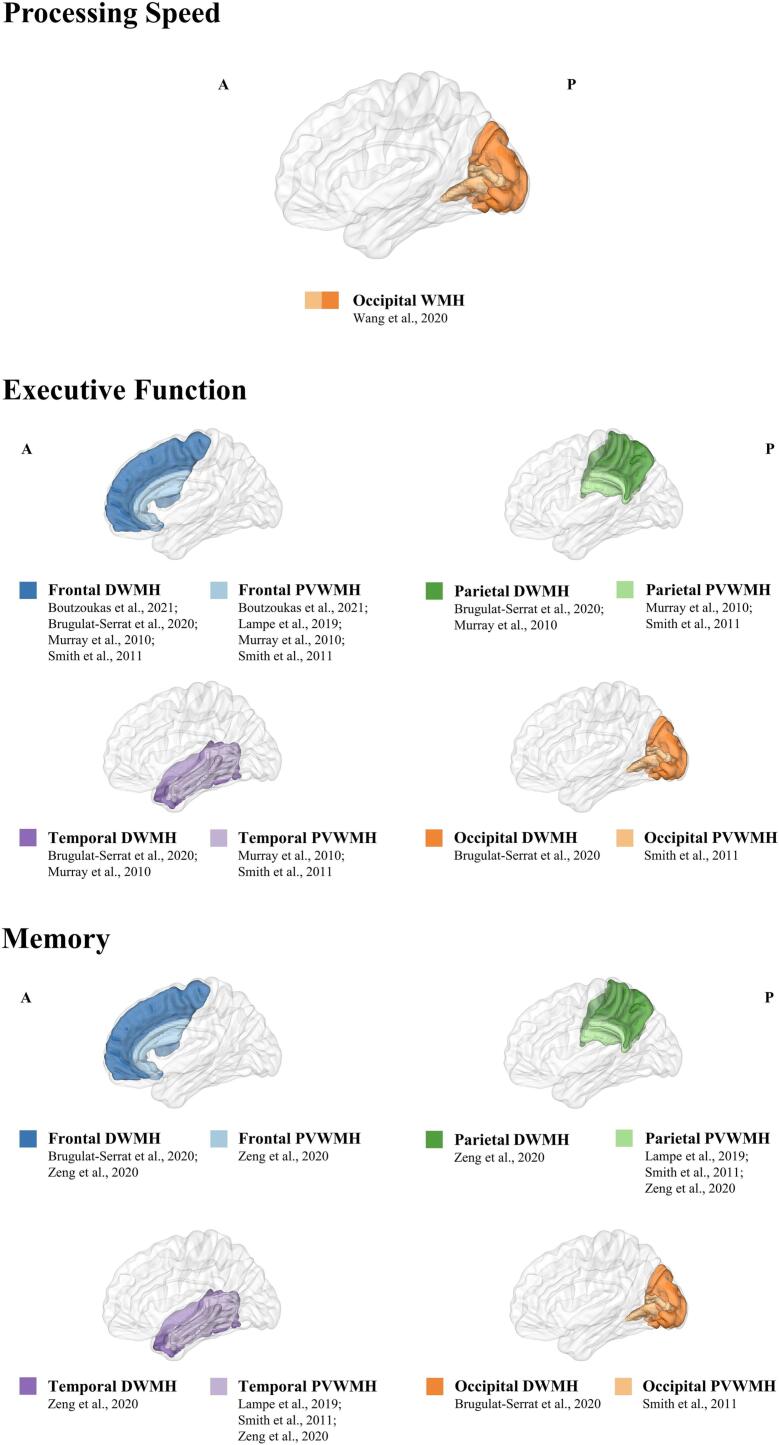

Regarding lobar classification, few studies have directly investigated the relationship between hypertension, lobar lesion volume of WMHs and cognition. Some studies have examined the effect of specific loci of WMHs on cognition (some participants had hypertension) and found that PS may be influenced by WMHs volume in the occipital lobe (Wang et al., 2020) (Table 2, Fig. 1). Meanwhile, executive dysfunction was mainly related to frontal WMHs (Boutzoukas et al., 2021, Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020, Lampe et al., 2019, Smith et al., 2011) and to a lower degree in temporal, parietal and occipital areas (Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020, Murray et al., 2010, Smith et al., 2011). For memory function, some studies related its disturbance to parietal-temporal WMHs (Lampe et al., 2019, Smith et al., 2011, Zeng et al., 2020), or frontal or occipital WMHs (Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020, Smith et al., 2011, Zeng et al., 2020). As a result, hypertension-affected cognitive domains appear to be connected to numerous different and widely distributed brain regions.

Table 2.

The corresponding effect of WM macrostructural changes (lobar WMH) on specific cognitive domains.

| Cognitive Alterations | WM Macrostructural change | Study | No. of participants (Hypertensives) | Age: Average | Cognitive tests | Effect size ρ/β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | Occipital WMH | Wang et al., 2020 | 60 (37) | 64.8 | TMT-A | 0.266 |

| EF | Frontal WMH | Boutzoukas et al., 2021 | 279 (-) | 71.6 | Set-shifting, inhibition, and working memory subtests of NIHTB Cognition Battery, DCCS, Flanker, List Sorting Working Memory Test | -0.21 to -0.17 |

| Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | Digit span, Coding, Matrix reasoning and Visual puzzles and Similarities subtests of WAIS-IV | -0.20 to 0 | ||

| Lampe et al., 2019 | 702 (-) | 68.49 | Wortschatztest (German vocabulary test), Phonetic and Semantic Verbal Fluency, TMT-A, TMT-B | Not reported | ||

| Murray et al., 2010 | 148 (1 0 3) | 79 | TMT-B, Digit Symbol subtest of WAIS-R | -0.20 | ||

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Self-Ordering Test, Porteus Mazes, Alpha Span Test, Backward Digit Span | Not reported | ||

| Parietal WMH | Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | Digit span, Coding, Matrix reasoning and Visual puzzles and Similarities subtests of WAIS-IV | -0.20 to 0 | |

| Murray et al., 2010 | 148 (1 0 3) | 79 | TMT-B, Digit Symbol subtest of WAIS-R | -0.22 | ||

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Self-Ordering Test, Porteus Mazes, Alpha Span Test, Backward Digit Span | Not reported | ||

| Temporal WMH | Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | Digit span, Coding, Matrix reasoning and Visual puzzles and Similarities subtests of WAIS-IV | -0.20 to 0 | |

| Murray et al., 2010 | 148 (1 0 3) | 79 | TMT-B, Digit Symbol subtest of WAIS-R | -0.25 | ||

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Self-Ordering Test, Porteus Mazes, Alpha Span Test, Backward Digit Span | Not reported | ||

| Occipital WMH | Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | Digit span, Coding, Matrix reasoning and Visual puzzles and Similarities subtests of WAIS-IV | -0.20 to 0 | |

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Self-Ordering Test, Porteus Mazes, Alpha Span Test, Backward Digit Span | Not reported | ||

| Memory | Frontal WMH | Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | MBT | -0.20 to 0 |

| Zeng et al., 2020 | 321 (1 6 6) | 66.43 | AVLT, ROCF-delayed recall, Digit Span test of WAIS | Not reported | ||

| Parietal WMH | Lampe et al., 2019 | 702 (-) | 68.49 | Delayed Recall Words, Recognition Words, Immediate Recall Words | Not reported | |

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | CVLT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, ROCF-delayed recall, Visual Reproduction subtest of the WMS | Not reported | ||

| Zeng et al., 2020 | 321 (1 6 6) | 66.43 | AVLT, ROCF-delayed recall, Digit Span test of WAIS | Not reported | ||

| Temporal WMH | Lampe et al., 2019 | 702 (-) | 68.49 | Delayed Recall Words, Recognition Words, Immediate Recall Words | Not reported | |

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | CVLT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, ROCF-delayed recall, Visual Reproduction subtest of the WMS | Not reported | ||

| Zeng et al., 2020 | 321 (1 6 6) | 66.43 | AVLT, ROCF-delayed recall, Digit Span test of WAIS | Not reported | ||

| Occipital WMH | Brugulat-Serrat et al., 2020 | 561 (1 4 7) | 57.4 | MBT | -0.20 to 0 | |

| Smith et al., 2011 | 147 (1 1 8) | 72.53 | CVLT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, ROCF-delayed recall, Visual Reproduction subtest of the WMS | Not reported |

Notes: PS: processing speed; EF: executive function; WMH: White Matter Hyperintensities; TMT-A: Trail Making Test-A; DCCS: Dimensional Change Card Sort Test; Flanker: The Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test; WAIS-IV: Wechsler Adult Intelligent Scale Fourth Edition; TMT-B: Trail Making Test-B; WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised; SCWT: Stroop Color Word Test; MBT: Memory Binding Test; AVLT: Auditory Verbal Learning Test, ROCF: Rey Ostereith Complex Figure Test; CVLT: California Verbal Learning Test; WMS: Wechsler Memory Scale.

Fig. 1.

The corresponding effect of macrostructural lobar WMH on specific cognitive domains.

A meta-analysis was also conducted to quantify the relationship between WMHs and cognition. The results showed that WMHs did have significant negative correlation with cognitive function (r = -0.23, 95% CI: -0.29 to -0.16) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The studies exhibited no heterogeneity (I2 = 0, p = 0.58), thus a common effect model was employed. Furthermore, no publication bias was found (p = 0.212). Detailed information on the meta-analysis methodology is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

5.2. Influence of hypertension-related WM microstructural changes on cognition

Hypertension and lower WM microstructural integrity are mutually associated risk factors for poorer cognition in older adults (Luo et al., 2019). Hypertension was disproportionately associated with different cognitive domains, as disrupted WM microstructure was predominantly associated with PS and EF and less associated with learning and memory (Cremers et al., 2016, Luo et al., 2019, Santiago et al., 2015). According to the “disconnection hypothesis”, disrupted WM microstructure may result in loss of connection between cortical regions, leading to cognitive dysfunction (Bells et al., 2017, Brier et al., 2014, Teipel et al., 2014). It is likely that disrupted WM microstructures in specific tract bundles mediate the relationship between hypertension and multiple cognitive functions (Luo et al., 2019).

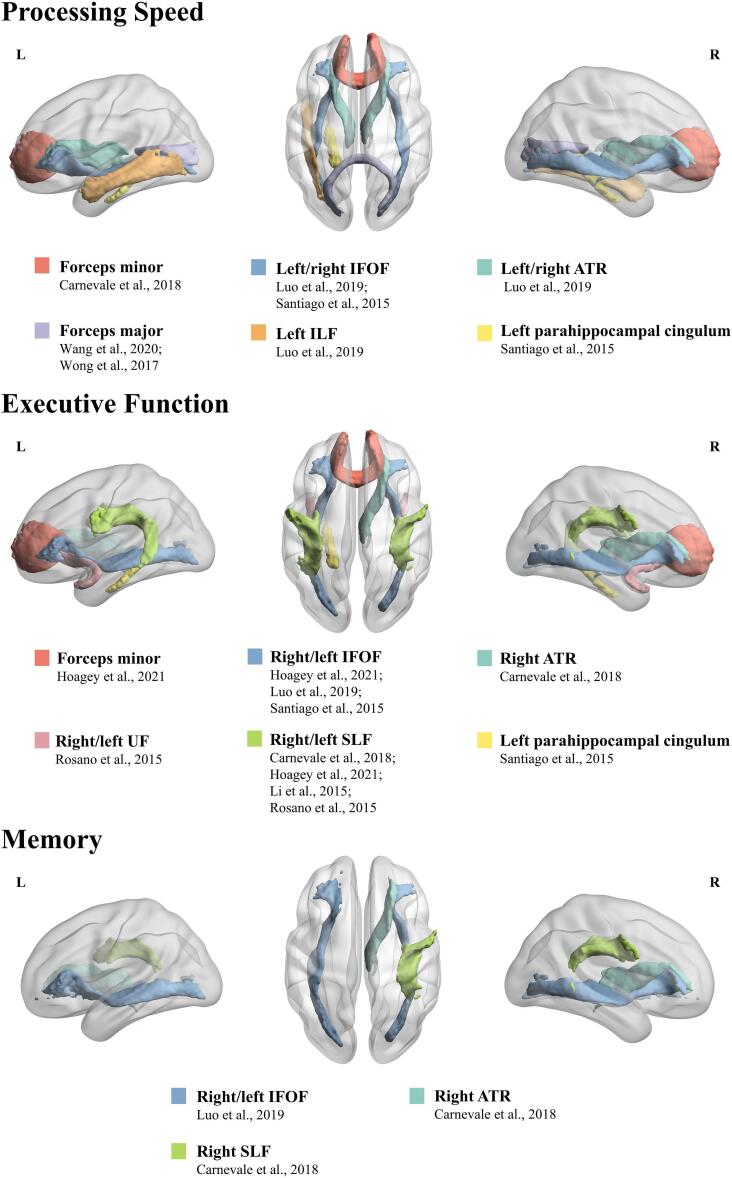

Interestingly, hypertension-induced microstructural alterations of specific WM tracts showed different corresponding effects on specific cognitive domains that were concomitantly impaired (Table 3, Fig. 2). For PS, both forceps minor, a fiber bundle that connects bilateral frontal lobes and crosses the midline through the corpus callosum genu, as well as forceps major that connects bilateral occipital lobes and crosses the midline via the corpus callosum splenium, were significant predictors in hypertensive patients (Carnevale et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2020, Wong et al., 2017). The negative association between hypertension and PS may be also mediated by reduced integrity of long-range WM tracts linking anterior to posterior brain regions, including the left/right IFOF (linking inferior frontal, parietal and occipital areas, adjacent to the inferolateral insula), left ILF (linking occipital and temporal-occipital areas of the brain to the anterior temporal areas), and left/right ATR (linking dorsolateral prefrontal regions to the thalamic nuclei via anterior limb of the internal capsule) (Luo et al., 2019, Santiago et al., 2015). Finally, the left parahippocampal cingulum, a tract running from the medial temporal lobe to the parietal and occipital lobes, also affected PS (Santiago et al., 2015). For the domain of EF, the injured long-range fibers, including the SLF (linking parietal, occipital and temporal lobes with ipsilateral frontal cortices), uncinate fasciculus (UF) (linking anterior temporal lobe with medial orbitofrontal cortex), ATR, IFOF, corpus callosum genu and left parahippocampal cingulum, play a role in its relationship with hypertension (Carnevale et al., 2018, Hoagey et al., 2021, Li et al., 2015, Luo et al., 2019, Rosano et al., 2015, Santiago et al., 2015). In addition, hypertension is negatively associated with memory through microstructural alterations in the long-range fibers including SLF, ATR and IFOF (Carnevale et al., 2018, Luo et al., 2019).

Table 3.

The corresponding effect of hypertension-related WM microstructural changes on specific cognitive domains.

| Cognitive Alterations | WM Microstructural change | Study | No. of participants (Hypertensives) | Age: Average | Cognitive tests | Effect size r/ρ/β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | FA | left IFOF | Santiago et al., 2015 | 49 (24) | 66.3 | DSST, TMT-A, TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Stroop Dot-Color Test, FAS Verbal Fluency Test, Animal Naming Test# | 0.430 |

| forceps minor | Carnevale et al., 2018 | 42 (23) | 53.6 | Interference subtest of SCWT | -0.362/-0.332 | ||

| forceps major/corpus callosum splenium | Wang et al., 2020 | 60 (37) | 64.8 | TMT-A | -0.20 | ||

| Wong et al., 2017 | 40* | 63.78 | Digit Symbol Coding and Symbol Search subtests of WAIS-III | Not reported | |||

| left parahippocampal cingulum | Santiago et al., 2015 | 49 (24) | 66.3 | DSST, TMT-A, TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Stroop Dot-Color Test, FAS Verbal Fluency Test, Animal Naming Test# | 0.471 | ||

| mGFA | left/right IFOF | Luo et al., 2019 | 66 (41) | 67.54 | DSST, Word naming subtest of SCWT, CTT1 | 0.53/0.46 | |

| left/right ATR | Luo et al., 2019 | 66 (41) | 67.54 | DSST, Word naming subtest of SCWT, CTT1 | 0.27/0.27 | ||

| left ILF | Luo et al., 2019 | 66 (41) | 67.54 | DSST, Word naming subtest of SCWT, CTT1 | 0.31 | ||

| EF | FA | left IFOF | Santiago et al., 2015 | 49 (24) | 66.3 | DSST, TMT-A, TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Stroop Dot-Color Test, FAS Verbal Fluency Test, Animal Naming Test# | 0.430 |

| IFOF | Hoagey et al., 2021 | 184* | 53.2 | CWI and Trial Making subtests of D-KEFS | -0.288 | ||

| right SLF | Carnevale et al., 2018 | 42 (23) | 53.6 | EF subdomain of MoCA | 0.338 | ||

| left SLF | Li et al., 2015 | 84 (44) | 64.56 | TMT B-A | Not reported | ||

| SLF | Hoagey et al., 2021 | 184* | 53.2 | CWI and Trial Making subtests of D-KEFS | -0.288 | ||

| Rosano et al., 2015 | 311 (2 1 7) | 82.9 | DSST | 0.133 | |||

| right ATR | Carnevale et al., 2018 | 42 (23) | 53.6 | EF subdomain of MoCA | 0.335 | ||

| forceps minor/ corpus callosum genu | Hoagey et al., 2021 | 184* | 53.2 | CWI and Trial Making subtests of D-KEFS | -0.288 | ||

| left parahippocampal cingulum | Santiago et al., 2015 | 49 (24) | 66.3 | DSST, TMT-A, TMT-B, Interference subtest of SCWT, Stroop Dot-Color Test, FAS Verbal Fluency Test, Animal Naming Test# | 0.471 | ||

| UF | Rosano et al., 2015 | 311 (2 1 7) | 82.9 | DSST | 0.133 | ||

| MD | left SLF | Li et al., 2015 | 84 (44) | 64.56 | TMT B-A | Not reported | |

| mGFA | left/right IFOF | Luo et al., 2019 | 66 (41) | 67.54 | Backward Digit Span, Interference subtest of SCWT, CTT2-1 | 0.35/0.25 | |

| Memory | FA | right SLF | Carnevale et al., 2018 | 42 (23) | 53.6 | Memory subdomain of MoCA | 0.338 |

| right ATR | Carnevale et al., 2018 | 42 (23) | 53.6 | Memory subdomain of MoCA | 0.335 | ||

| mGFA | left/right IFOF | Luo et al., 2019 | 66 (41) | 67.54 | VR and VeP subtests of WMS-3, WMS-R-ViP, CVLT-II | 0.41, 0.44/0.30, 0.33 | |

Notes: PS: processing speed; EF: executive function; FA: fractional anisotropy; MD: mean diffusivity; mGFA: mean generalized fractional anisotropy; IFOF: inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus; ATR: anterior thalamic radiations; ILF: inferior longitudinal fasciculus; SLF: superior longitudinal fasciculus; UF: uncinate fasciculus; DSST: Digit Symbol Substitution Test; TMT-A: Trail Making Test-A; TMT-B: Trail Making Test-B; SCWT: Stroop Color Word Test; WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligent Scale Third Edition; CTT1: part 1 of the Color Trails Test; CWI: Color Word Interference; D-KEFS: Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; MoCA: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CTT2-1: part 2 of the Color Trails Test-part 1 of the Color Trails Test; VR: Visual Reproduction; VeP: Verbal Paired Associates; WMS-3: Wechsler Memory Scale Third Edition; ViP: Visual Paired Associates; WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale Revised; CVLT-II: California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition; *: total sample of cognitively normal individuals, these studies used systolic blood pressure as a variable that contributed to reduced FA within these WM tracts predicting worsen cognition; #: cognitive tests were used for calculating composite z scores for the EF and PS cognitive domain, this study considered PS and EF as one domain.

Fig. 2.

The corresponding effect of hypertension-related microstructural changes of specific WM tracts on specific cognitive domains.

From the findings above, long-range WM tracts appear to be more vulnerable to hypertension and result in corresponding cognitive impairment. Long-range fiber tracts mainly traverse the periventricular watershed irrigated by vascular territories of distal arterioles and are susceptible to hypoperfusion (a major negative effect of hypertension), and its pathological changes could later lead to impaired axonal transmission and cognitive function (Bolandzadeh et al., 2012, Smith et al., 2011, Tzourio et al., 2014). In line with this pathogenic mechanism, the aforementioned long-range fibers, including the SLF, ATR, IFOF, ILF and forceps minor, all pass alongside the lateral ventricles to a large degree (Caverzasi et al., 2014, Jang and Yeo, 2013, Luo et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2016). This is consistent with the spatial distribution of WMHs; that is, hypertension-induced PVWMHs with a high density of long-range fibers were more prevalent than DWMHs with short fibers (Henskens et al., 2009, Yoshita et al., 2006).

A meta-analysis was also conducted to quantify the relationship between hypertension-related WM microstructural changes and cognition. Overall, there was a moderate positive relationship between white matter integrity and cognitive function (r = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.51) (Supplementary Fig. 2). There was heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 76%, p < 0.01); therefore, a random effect model was used. Besides, the white matter integrity indicated a moderate effect on the EF domain (r = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.13 to 0.48) (Supplementary Fig. 3), with significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 69%, p = 0.02), warranting a random effect model. Moreover, a moderate positive relation between white matter integrity and the domain of PS was also found (r = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.52) (Supplementary Fig. 4), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 22%, p = 0.28) and thus a common effect model was utilized. Egger’s regression asymmetry test suggested no evidence of publication bias for the three analyses (all p > 0.05).

6. Future prospects

First, the cognitive domains most influenced by hypertension, such as PS, EF and memory, appear to be related to widely distributed brain regions. However, recent research investigating WMCs among aging hypertensive patients has mainly focused on separate regions and rarely considered whole-brain WM network connectivity. More attention can be paid to the network-based changes in hypertension, which may offer more insights into the neural mechanism behind hypertension-affected cognitive decline.

Additionally, the heterogeneity of older adults must also be taken into account. For instance, since the effects of BP on cognition tend to vary with age (Shang et al., 2016), future research or clinical trials may also benefit from restricting enrollment of specific age groups. The independent roles of different BP components in brain structure and cognition were also shown by different studies, but there were inconsistences and more studies are needed to investigate the subgroups with different hypertensive status specifically. Other relevant factors, such as sex, race, genetics, lifestyle, onset and duration of hypertension, have also been identified and should therefore be considered when designing future research or antihypertensive trials.

Finally, it is important to note that there is currently limited research, particularly longitudinal studies, investigating the impact of BP interventions in late life on WM and subsequent cognitive function, which is of great clinical importance (McGuinness et al., 2009). Existing studies have shown controversial results regarding whether antihypertensive therapy could decrease the risk of WMCs and cognitive impairment. Additionally, it remains unclear whether BP-lowering treatment can reverse pre-existing WMCs and if such reversal is permanent. More studies are needed to fully investigate this issue, which should have long periods of follow-up using comprehensive neuropsychological tests with WMCs and cognition as primary outcomes. In addition, considering the potential downsides of aggressive antihypertension treatment including hypotension, syncope, electrolyte abnormalities and acute renal injury or acute renal failure (Bress et al., 2017), when making decisions regarding the BP treatment, more cautious approach should be taken and other factors such as comorbidities (Yeung et al., 2020) and cardiovascular risk (Phillips et al., 2018) that had an effect on treatment outcomes should be considered. Combining antihypertensive drugs and lifestyle interventions may better treat hypertension, prevent or delay the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in hypertensive patients (Burke et al., 2005, Dickinson et al., 2006, Kivipelto et al., 2018).

7. Conclusion

In summary, hypertension is an important risk factor for both WM microstructural damage, especially for long-range fibers such as IFOF and ATR, and subsequent macrostructural changes across different lobes, especially for the periventricular area containing long-range fibers. Several key factors, including vascular remodeling, atherosclerosis, autoregulation, hypoperfusion, endothelial dysfunction, BBB dysfunction and inflammatory processes, are common to hypertension-related WMCs. Subsequently, those damaged WM would further exert corresponding negative effects on multiple cognitive domains, including PS, EF and memory based on their spatial characteristic. The relationship between hypertension-related WMCs and subsequent cognitive outcomes were also quantified and confirmed by the meta-analyses. The conceptual model of hypertension-white matter changes-cognition link was shown in Fig. 3. This might indicate that WMCs are important brain mechanism in hypertension-related cognitive impairment. As susceptible areas, periventricular or long-range tracts of WM injury might be potential brain targets for hypertensive patients developing cognitive impairment or dementia. Clinicians and providers of hypertensive patients should be aware of the increased risks of cognitive dysfunction and dementia that may be related to high BP.

Fig. 3.

Conceptual model of hypertension-white matter changes-cognition link, which describes the pathological mechanisms of hypertension-related WM microstructural and macrostructural abnormalities, and then accelerates brain aging and cognitive decline.

Funding

This research was funded by STI2030-Major Projects (grant number 2022ZD0211600), Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32171085) and Tang Scholar.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Some materials in Fig. 1 were created with BioRender.com and Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Brain image indicating WM Microstructure change in Fig. 1 was originated from the study of Luo et al. (Luo et al., 2019), with permission. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 were visualized using the BrainNet Viewer (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/)(Xia et al., 2013).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103389.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Alateeq K., Walsh E.I., Cherbuin N. Higher blood pressure is associated with greater white matter lesions and brain atrophy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:637. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andica C., Kamagata K., Takabayashi K., Kikuta J., Kaga H., Someya Y., Tamura Y., Kawamori R., Watada H., Taoka T., Naganawa S., Aoki S. Neuroimaging findings related to glymphatic system alterations in older adults with metabolic syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023;177 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2023.105990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N.J., Mather K.A., Sargurupremraj M., Knol M.J., Malik R., Satizabal C.L., Yanek L.R., Wen W., Gudnason V.G., Dueker N.D., Elliott L.T., Hofer E., Bis J., Jahanshad N., Li S., Logue M.A., Luciano M., Scholz M., Smith A.V., Trompet S., Vojinovic D., Xia R., Alfaro-Almagro F., Ames D., Amin N., Amouyel P., Beiser A.S., Brodaty H., Deary I.J., Fennema-Notestine C., Gampawar P.G., Gottesman R., Griffanti L., Jack C.R., Jenkinson M., Jiang J., Kral B.G., Kwok J.B., Lampe L., Liewald C.M.D., Maillard P., Marchini J., Bastin M.E., Mazoyer B., Pirpamer L., Rafael Romero J., Roshchupkin G.V., Schofield P.R., Schroeter M.L., Stott D.J., Thalamuthu A., Trollor J., Tzourio C., van der Grond J., Vernooij M.W., Witte V.A., Wright M.J., Yang Q., Morris Z., Siggurdsson S., Psaty B., Villringer A., Schmidt H., Haberg A.K., van Duijn C.M., Jukema J.W., Dichgans M., Sacco R.L., Wright C.B., Kremen W.S., Becker L.C., Thompson P.M., Mosley T.H., Wardlaw J.M., Ikram M.A., Adams H.H.H., Seshadri S., Sachdev P.S., Smith S.M., Launer L., Longstreth W., DeCarli C., Schmidt R., Fornage M., Debette S., Nyquist P.A. Common genetic variation indicates separate causes for periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities. Stroke. 2020;51:2111–2121. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.119.027544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey E.L., Wardlaw J.M., Graham D., Dominiczak A.F., Sudlow C.L.M., Smith C. Cerebral small vessel endothelial structural changes predate hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats: a blinded, controlled immunohistochemical study of 5- to 21-week-old rats: Vascular changes in SHRSP rats. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2011;37:711–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D.E., Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykara E., Gesierich B., Adam R., Tuladhar A.M., Biesbroek J.M., Koek H.L., Ropele S., Jouvent E., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Chabriat H., Ertl-Wagner B., Ewers M., Schmidt R., de Leeuw F.-E., Biessels G.J., Dichgans M., Duering M. A Novel imaging marker for small vessel disease based on skeletonization of white matter tracts and diffusion histograms: novel SVD imaging marker. Ann. Neurol. 2016;80:581–592. doi: 10.1002/ana.24758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bells S., Lefebvre J., Prescott S.A., Dockstader C., Bouffet E., Skocic J., Laughlin S., Mabbott D.J. Changes in white matter microstructure impact cognition by disrupting the ability of neural assemblies to synchronize. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:8227–8238. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0560-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett I.J., Madden D.J., Vaidya C.J., Howard D.V., Howard J.H. Age-related differences in multiple measures of white matter integrity: a diffusion tensor imaging study of healthy aging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:378–390. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolandzadeh N., Davis J.C., Tam R., Handy T.C., Liu-Ambrose T. The association between cognitive function and white matter lesion location in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutzoukas E.M., O’Shea A., Albizu A., Evangelista N.D., Hausman H.K., Kraft J.N., Van Etten E.J., Bharadwaj P.K., Smith S.G., Song H., Porges E.C., Hishaw A., DeKosky S.T., Wu S.S., Marsiske M., Alexander G.E., Cohen R., Woods A.J. Frontal white matter hyperintensities and executive functioning performance in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.672535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress A.P., Kramer H., Khatib R., Beddhu S., Cheung A.K., Hess R., Bansal V.K., Cao G., Yee J., Moran A.E., Durazo-Arvizu R., Muntner P., Cooper R.S. Potential deaths averted and serious adverse events incurred from adoption of the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) intensive blood pressure regimen in the united states: projections from NHANES (national health and nutrition examination survey) Circulation. 2017;135:1617–1628. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.025322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brier M.R., Thomas J.B., Ances B.M. Network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: refining the disconnection hypothesis. Brain Connect. 2014;4:299–311. doi: 10.1089/brain.2014.0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugulat-Serrat A., Salvadó G., Sudre C.H., Grau-Rivera O., Suárez-Calvet M., Falcon C., Sánchez-Benavides G., Gramunt N., Fauria K., Cardoso M.J., Barkhof F., Molinuevo J.L., Gispert J.D. Patterns of white matter hyperintensities associated with cognition in middle-aged cognitively healthy individuals. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14:2012–2023. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucur B., Madden D.J. Effects of adult age and blood pressure on executive function and speed of processing. Exp. Aging Res. 2010;36:153–168. doi: 10.1080/03610731003613482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke V., Beilin L.J., Cutt H.E., Mansour J., Wilson A., Mori T.A. Effects of a lifestyle programme on ambulatory blood pressure and drug dosage in treated hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2005;23:1241–1249. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000170388.61579.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale L., D’Angelosante V., Landolfi A., Grillea G., Selvetella G., Storto M., Lembo G., Carnevale D. Brain MRI fiber-tracking reveals white matter alterations in hypertensive patients without damage at conventional neuroimaging. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018;114:1536–1546. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caverzasi E., Papinutto N., Amirbekian B., Berger M.S., Henry R.G. Q-ball of inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus and beyond. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e100274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro A.G., Melgarejo J.D., Leendertz R., Igwe K.C., Lao P.J., Laing K.K., Rizvi B., Budge M., Meier I.B., Calmon G., Lee J.H., Maestre G.E., Brickman A.M. White matter hyperintensities mediate the association of nocturnal blood pressure with cognition. Neurology. 2020;94 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009316. e1803–e1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin C., Suerken C.K., Bateman J.R., Whitlow C.T., Williams B.J., Espeland M.A., Sachs B.C., Cleveland M., Yang M., Rogers S., Hayden K.M., Baker L.D., Williamson J., Craft S., Hughes T.M., Lockhart S.N. Vascular and microstructural markers of cognitive pathology. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2022;14:e12332. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D.L., Townsend R.R. Update on pathophysiology and treatment of hypertension in the elderly. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2011;13:330–337. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremers L.G.M., de Groot M., Hofman A., Krestin G.P., van der Lugt A., Niessen W.J., Vernooij M.W., Ikram M.A. Altered tract-specific white matter microstructure is related to poorer cognitive performance: the rotterdam study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;39:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire-Théroux C., Quesnel-Olivo M.-H., Brochu K., Bergeron F., O’Connor S., Turgeon A.F., Laforce R.J., Verreault S., Camden M.-C., Duchesne S. Evaluation of intensive vs standard blood pressure reduction and association with cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2134553. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot J.C., de Leeuw F.E., Oudkerk M., van Gijn J., Hofman A., Jolles J., Breteler M.M. Cerebral white matter lesions and cognitive function: the rotterdam Scan Study. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:145–151. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200002)47:2<145::aid-ana3>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J.C., De Leeuw F.E., Oudkerk M., Van Gijn J., Hofman A., Jolles J., Breteler M.M. Periventricular cerebral white matter lesions predict rate of cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:335–341. doi: 10.1002/ana.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J.C. Critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion: the CATCH hypothesis of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J.C. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/367516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw F.E., de Groot J.C., Achten E., Oudkerk M., Ramos L.M., Heijboer R., Hofman A., Jolles J., van Gijn J., Breteler M.M. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw F.E., de Groot J.C., Oudkerk M., Witteman J.C., Hofman A., van Gijn J., Breteler M.M. Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain. 2002;125:765–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes S.T., Giatti L., Brant L.C.C., Griep R.H., Schmidt M.I., Duncan B.B., Suemoto C.K., Ribeiro A.L.P., Barreto S.M. Hypertension, prehypertension, and hypertension control: association with decline in cognitive performance in the ELSA-brasil cohort. Hypertension. 2021;77:672–681. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S., Markus H.S. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2010;341 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson H.O., Mason J.M., Nicolson D.J., Campbell F., Beyer F.R., Cook J.V., Williams B., Ford G.A. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2006;24:215–233. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divisón-Garrote J.A., Banegas J.R., De la Cruz J.J., Escobar-Cervantes C., De la Sierra A., Gorostidi M., Vinyoles E., Abellán-Aleman J., Segura J., Ruilope L.M. Hypotension based on office and ambulatory monitoring blood pressure. Prevalence and clinical profile among a cohort of 70,997 treated hypertensives. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. JASH. 2016;10:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufouil C., de Kersaint-Gilly A., Besançon V., Levy C., Auffray E., Brunnereau L., Alpérovitch A., Tzourio C. Longitudinal study of blood pressure and white matter hyperintensities: the EVA MRI Cohort. Neurology. 2001;56:921–926. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.7.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duschek S., Schandry R. Reduced brain perfusion and cognitive performance due to constitutional hypotension. Clin. Auton. Res. 2007;17:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s10286-006-0379-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euser S.M., Van Bemmel T., Schram M.T., Gussekloo J., Hofman A., Westendorp R.G.J., Breteler M.M.B. The effect of age on the association between blood pressure and cognitive function later in life: BLOOD PRESSURE AND COGNITIVE FUNCTION. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009;57:1232–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Bai J., Liu W., Cai J. Effects of intensive vs. standard blood pressure control on cognitive function: Post-hoc analysis of the STEP randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2023;14:1042637. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1042637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Yang X., Tao Y., Lan L., Zheng L., Sun J. Tight junction disruption of blood–brain barrier in white matter lesions in chronic hypertensive rats. NeuroReport. 2015;26:1039–1043. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraci F.M. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300:H1566–H1582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraco G., Iadecola C. Hypertension: a harbinger of stroke and dementia. Hypertension. 2013;62:810–817. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennema-Notestine C., McEvoy L.K., Notestine R., Panizzon M.S., Yau W.-Y.-W., Franz C.E., Lyons M.J., Eyler L.T., Neale M.C., Xian H., McKenzie R.E., Kremen W.S. White matter disease in midlife is heritable, related to hypertension, and shares some genetic influence with systolic blood pressure. NeuroImage Clin. 2016;12:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryar, C.D., Zhang, G., 2017. Hypertension Prevalence and Control Among Adults: United States, 2015–2016 8. [PubMed]

- Gao H., Wang K., Ahmadizar F., Zhuang J., Jiang Y., Zhang L., Gu J., Zhao W., Xia Z.L. Associations of changes in late-life blood pressure with cognitive impairment among older population in China. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:536. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02479-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alberca J.M., Mendoza S., Gris E., Royo J.L., Cruz-Gamero J.M., García-Casares N. White matter lesions and temporal atrophy are associated with cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with hypertension and Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2020;35:1292–1300. doi: 10.1002/gps.5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin O., Tzourio C., Maillard P., Mazoyer B., Dufouil C. Antihypertensive treatment and change in blood pressure are associated with the progression of white matter lesion volumes: the three-city (3C)–Dijon magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2011;123:266–273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong G., He Y., Concha L., Lebel C., Gross D.W., Evans A.C., Beaulieu C. Mapping anatomical connectivity patterns of human cerebral cortex using in vivo diffusion tensor imaging tractography. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:524–536. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gons R.A.R., de Laat K.F., van Norden A.G.W., van Oudheusden L.J.B., van Uden I.W.M., Norris D.G., Zwiers M.P., de Leeuw F.-E. Hypertension and cerebral diffusion tensor imaging in small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41:2801–2806. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gons R.A.R., van Oudheusden L.J.B., de Laat K.F., van Norden A.G.W., van Uden I.W.M., Norris D.G., Zwiers M.P., van Dijk E., de Leeuw F.-E. Hypertension is related to the microstructure of the corpus callosum: the RUN DMC study. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 2012;32:623–631. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick P.B., Scuteri A., Black S.E., DeCarli C., Greenberg S.M., Iadecola C., Launer L.J., Laurent S., Lopez O.L., Nyenhuis D., Petersen R.C., Schneider J.A., Tzourio C., Arnett D.K., Bennett D.A., Chui H.C., Higashida R.T., Lindquist R., Nilsson P.M., Roman G.C., Sellke F.W., Seshadri S. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman R.F., Schneider A.L., Albert M., Alonso A., Bandeen-Roche K., Coker L., Coresh J., Knopman D., Power M.C., Rawlings A., Sharrett A.R., Wruck L.M., Mosley T.H. Midlife hypertension and 20-year cognitive change: the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1218–1227. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffanti L., Jenkinson M., Suri S., Zsoldos E., Mahmood A., Filippini N., Sexton C.E., Topiwala A., Allan C., Kivimäki M., Singh-Manoux A., Ebmeier K.P., Mackay C.E., Zamboni G. Classification and characterization of periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities on MRI: a study in older adults. NeuroImage. 2018;170:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronewold J., Jokisch M., Schramm S., Jockwitz C., Miller T., Lehmann N., Moebus S., Jöckel K.H., Erbel R., Caspers S., Hermann D.M. Association of blood pressure, its treatment, and treatment efficacy with volume of white matter hyperintensities in the population-based 1000BRAINS Study. Hypertension. 2021;78:1490–1501. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.18135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevarra A.C., Ng S.C., Saffari S.E., Wong B.Y.X., Chander R.J., Ng K.P., Kandiah N. Age Moderates associations of hypertension, white matter hyperintensities, and cognition. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75:1351–1360. doi: 10.3233/jad-191260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Simpkins A.N., Hitomi E., Dias C., Leigh R. White Matter hyperintensity-associated blood-brain barrier disruption and vascular risk factors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018;27:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez J., Elkind M.S.V., Cheung K., Rundek T., Sacco R.L., Wright C.B. Pulsatile and steady components of blood pressure and subclinical cerebrovascular disease: the Northern Manhattan Study. J. Hypertens. 2015;33:2115–2122. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habes M., Erus G., Toledo J.B., Zhang T., Bryan N., Launer L.J., Rosseel Y., Janowitz D., Doshi J., Van der Auwera S., von Sarnowski B., Hegenscheid K., Hosten N., Homuth G., Völzke H., Schminke U., Hoffmann W., Grabe H.J., Davatzikos C. White matter hyperintensities and imaging patterns of brain ageing in the general population. Brain. 2016;139:1164–1179. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann P., Cammoun L., Gigandet X., Meuli R., Honey C.J., Wedeen V.J., Sporns O. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLOS Biol. 2008;6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight T., Nick Bryan R., Erus G., Hsieh M.-K., Davatzikos C., Nasrallah I., D’Esposito M., Jacobs D.R., Lewis C., Schreiner P., Sidney S., Meirelles O., Launer L.J. White matter microstructure, white matter lesions, and hypertension: an examination of early surrogate markers of vascular-related brain change in midlife. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;18:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar I., Quach L., Yang F., Chaves P.H.M., Newman A.B., Mukamal K., Longstreth W., Inzitari M., Lipsitz L.A. Hypertension, white matter hyperintensities, and concurrent impairments in mobility, cognition, and mood: the cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2011;123:858–865. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton O.K.L., Backhouse E.V., Janssen E., Jochems A.C.C., Maher C., Ritakari T.E., Stevenson A.J., Xia L., Deary I.J., Wardlaw J.M. Cognitive impairment in sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:665–685. doi: 10.1002/alz.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henskens L.H., Kroon A.A., van Oostenbrugge R.J., Gronenschild E.H., Hofman P.A., Lodder J., de Leeuw P.W. Associations of ambulatory blood pressure levels with white matter hyperintensity volumes in hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens. 2009;27:1446–1452. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832b5204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagey D.A., Lazarus L.T.T., Rodrigue K.M., Kennedy K.M. The effect of vascular health factors on white matter microstructure mediates age-related differences in executive function performance. Cortex. 2021;141:403–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.Y., Ou Y.N., Shen X.N., Qu Y., Ma Y.H., Wang Z.T., Dong Q., Tan L., Yu J.T. White matter hyperintensities and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;120:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. The Pathobiology of Vascular Dementia. Neuron. 2013;80:844–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Hypertension and dementia. Hypertension. 2014;64:3–5. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.114.03040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C., Gottesman R.F. Neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019;124:1025–1044. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.118.313260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C., Yaffe K., Biller J., Bratzke L.C., Faraci F.M., Gorelick P.B., Gulati M., Kamel H., Knopman D.S., Launer L.J., Saczynski J.S., Seshadri S., Hazzouri Z.A., A., Impact of hypertension on cognitive function: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension. 2016;68 doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S.H., Yeo S.S. Thalamocortical tract between anterior thalamic nuclei and cingulate gyrus in the human brain: diffusion tensor tractography study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:236–241. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings J.R., Muldoon M.F., Sved A.F. Is the brain an early or late component of essential hypertension? Am. J. Hypertens. 2020;33:482–490. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- X. Ji X.-Y. Leng Y. Dong Y.-H. Ma W. Xu X.-P. Cao X.-H. Hou Q. Dong L. Tan J.-T. Yu Modifiable risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review Ann. Transl. Med. 7 2019 632 632 https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.10.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jia L., Du Y., Chu L., Zhang Z., Li F., Lyu D., Li Y., Li Y., Zhu M., Jiao H., Song Y., Shi Y., Zhang H., Gong M., Wei C., Tang Y., Fang B., Guo D., Wang F., Zhou A., Chu C., Zuo X., Yu Y., Yuan Q., Wang W., Li F., Shi S., Yang H., Zhou C., Liao Z., Lv Y., Li Y., Kan M., Zhao H., Wang S., Yang S., Li H., Liu Z., Wang Q., Qin W., Jia J., Quan M., Wang Y., Li W., Cao S., Xu L., Han Y., Liang J., Qiao Y., Qin Q., Qiu Q. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30185-7. e661–e671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Li S., Wang Y., Lai Y., Bai Y., Zhao M., He L., Kong Y., Guo X., Li S., Liu N., Jiang C., Tang R., Sang C., Long D., Du X., Dong J., Anderson C.S., Ma C. Diastolic blood pressure and intensive blood pressure control on cognitive outcomes: insights from the SPRINT MIND trial. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 2023;1979(80):580–589. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Balado J., Riba-Llena I., Abril O., Garde E., Penalba A., Ostos E., Maisterra O., Montaner J., Noviembre M., Mundet X., Ventura O., Pizarro J., Delgado P. Cognitive impact of cerebral small vessel disease changes in patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:342–349. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen D.R., Shaaban C.E., Wiley C.A., Gianaros P.J., Mettenburg J., Rosano C. A population neuroscience approach to the study of cerebral small vessel disease in midlife and late life: an invited review. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018;314:H1117–H1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00535.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney P.M., Whelton M., Reynolds K., Muntner P., Whelton P.K., He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly S.P., Lawlor B.A., Kenny R.A. Blood pressure and dementia - a comprehensive review. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2009;2:241–260. doi: 10.1177/1756285609103483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Lee S., Suh S.W., Bae J.B., Han J.H., Byun S., Han J.W., Kim J.H., Kim K.W. Association of low blood pressure with white matter hyperintensities in elderly individuals with controlled hypertension. J. Stroke. 2020;22:99–107. doi: 10.5853/jos.2019.01844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M., Mangialasche F., Ngandu T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018;14:653–666. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen S.E., Narkiewicz K., Burnier M., Oparil S. Intensive blood pressure lowering prevents mild cognitive impairment and possible dementia and slows development of white matter lesions in brain: the SPRINT Memory and Cognition IN Decreased Hypertension (SPRINT MIND) study. Blood Press. 2018;27:247–248. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2018.1507621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppenborg R.P., Nederkoorn P.J., Geerlings M.I., van den Berg E. Presence and progression of white matter hyperintensities and cognition: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82:2127–2138. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritz-Silverstein D., Laughlin G.A., McEvoy L.K., Barrett-Connor E. Sex and age differences in the association of blood pressure and hypertension with cognitive function in the elderly: the rancho bernardo study. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2017.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y., Jiang C., Du X., Sang C., Guo X., Bai R., Tang R., Dong J., Ma C. Effect of intensive blood pressure control on the prevention of white matter hyperintensity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich. 2020;22:1968–1973. doi: 10.1111/jch.14030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]