Abstract

Objective.

Victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) often fear their intimate partners and the abuse they perpetrate against them. Fear in the context of IPV has been studied for decades yet, we lack a rigorously validated measure. The purpose of this study was to comprehensively evaluate the psychometric properties of a multi-item scale measuring fear of an abusive male partner and/or the abuse he perpetrates.

Method:

We used Item Response modeling to evaluate the psychometric properties of a scale measuring women’s fear of IPV by their male partner across two distinct samples: 1) a calibration sample of 412 women and 2) a confirmation sample of 298 women.

Results:

Results provide a detailed overview of the psychometric functioning of the Intimate Partner Violence Fear-11 Scale. Items were strongly related to the latent fear factor, with discrimination values universally above a = 0.80 in both samples. Overall, the IPV Fear-11 Scale is psychometrically robust across both samples. All items were highly discriminating and the full scale was reliable across the range of the latent fear trait. Reliability was exceptionally high for measuring individuals experiencing moderate to high levels of fear. Finally, the IPV Fear-11 Scale was moderately to strongly correlated with depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms and physical victimization.

Conclusions:

The IPV Fear-11 Scale was psychometrically robust across both samples and was associated with a number of relevant covariates. Results support the utility of the IPV Fear-11 Scale for assessing fear of an abusive partner among women in relationships with men.

Keywords: Item response theory, validation, fear, domestic violence, partner violence

Introduction

Victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) often fear their intimate partners and the abuse they perpetrate against them (Logan & Lynch, 2018; Salcioglu et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019), including in relationships where the IPV is bidirectional (Houry et al., 2008). Some have argued that fear of an intimate partner is the hallmark of an abusive relationship (see Hamberger, 2005 for elaboration). Others have examined fear among victims of IPV and determined that there is variability in whether or not fear exists and separately, among those who do experience fear, that the level varies (Sullivan, Weiss, Price, et al., 2021). Variability in fear can help to differentiate subgroups of victims with shared experiences (Hamberger & Guse, 2005). Despite the significance of IPV-related fear, there is a dearth of rigorously evaluated measures that assess fear in the context of IPV, which affects more than one in three women in their lifetime (Black et al., 2011). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the psychometric properties of a multi-item scale measuring fear of an abusive male partner and/or fear of the abuse they perpetrate across two distinct samples of women.

Though the measurement of fear has varied by study, this construct has been a central focus of IPV scholarship for decades (e.g., Ross, 1993; Sacco, 1990) and has demonstrated relevance to IPV and its negative sequelae in the past, present, and future. For example, fear of a past abusive partner is associated with current PTSD among women currently in an abusive relationship (Jaquier & Sullivan, 2014; Salcioglu et al., 2017). Separately, fear of IPV persists months past the experience of IPV (Salcioglu et al., 2017). In the present, fear is associated with women’s engagement in the criminal justice system such that fear of reprisal or retribution by an abusive partner is one reason women do not call law enforcement for assistance (Felson et al., 2002) or engage regarding the prosecution of their abusers (Cerulli et al., 2014). Moreover, fear is associated with negative sequalae such as compromised mental health (Cheng & Lo, 2019), including PTSD and depression (Hebenstreit et al., 2015; Salcioglu et al., 2017) and physical health (Cheng & Lo, 2019), including traumatic brain injury (Ivany et al., 2018) – at least with the assessments used to date. Measuring fear of an abusive partner and/or the abuse they perpetrate, and doing so with a validated measure, is important for informing future research, as well as clinical practice and efforts to develop interventions to mitigate negative outcomes.

Assessment of fear in the aforementioned and other studies of IPV has often relied on single- or few-item measures developed specifically for that study (see Ross, 2012, p. 61 for a summary of measures). For example, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Neidig, and Thorn asked participants how often they felt “frightened of their spouse” with a 1 to 4 Likert response scale (1995, p. 166). Hamberger and Guse (2005) asked how intensely victims felt fear of their abusive partners. Olson and colleagues asked, “In the past 12 months, have you been frightened for the safety of yourself, your children or friends because of the anger or threats of an intimate partner?” (2008, p. 560). These items have demonstrated predictive utility in their respective studies and have been invaluable to elucidating the fear that IPV victims experience; however, the extent to which these assessments are psychometrically sound, and fully capture the variability of fear that exists, is unclear.

A few measures exist regarding IPV-related fear that are comprised of multiple items, which allow for a more comprehensive assessment of fear and, in some cases, for psychometric properties to be reported. For example, Sackett and Saunders (1999) measured fear of IPV with six items in the context of a study differentiating forms of psychological abuse. Together, these items demonstrated good internal validity but, at face value, seem to assess a combination of victim’s guilt/shame for their own victimization, worry that they will make their partner angry, and fear. This focus on multiple constructs in what is purported to be one assessment of fear likely limits the utility of this measure for future research. Further, analyses to test psychometric properties were not conducted. Another multi-item measure is the Fear of Partner Scale (O’Leary et al., 2013). This measure, comprised of 25 items, has been psychometrically evaluated and demonstrated good internal consistency reliability and strong construct validity. However, it was specifically developed to assess fear of one’s intimate partner as it relates to being involved in marital therapy and divorce mediation. Therefore, it too has limited utility for research on IPV in general.

Despite advances in measurement of fear, we lack a rigorously validated measure that comprehensively captures fear of an abusive partner and the IPV they perpetrate1. The Intimate Partner Violence Fear-11 Scale was developed for the present study. The measure was developed in several steps. Firstly, the authors reviewed another related measure that existed at the time, the Women’s Experiences of Battering scale (WEB; Smith et al., 1995). The WEB assesses victims’ responses and emotions about being battered, including fear. Secondly, to develop a measure that specifically focused on fear, the authors developed a set of items based on the WEB, as well as items generated from the authors’ work conducting psychoeducational groups with women court-mandated to participate in a program for individuals charged with domestic violence. Thirdly, the authors of the scale got feedback on the items from the team of facilitators who conducted the psychoeducational groups. Based on this feedback, the authors developed the final measure. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Intimate Partner Violence Fear-11 Scale using the methods of Item Response Theory (de Ayala, 2013; Embretson & Reise, 2013).

Item Response Theory Overview

Item response theory (IRT) is an analytic framework that incorporates a wide variety of latent variable measurement models for evaluating the psychometric properties of questionnaires, tests, and other means of psychological assessment (de Ayala, 2013; Embretson & Reise, 2013). IRT models are essentially confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) for categorical indicators where the likelihood of a specific item response is modeled as a function of the unobserved, latent trait of interest (e.g., fear) and a set of item parameters. The two major types of parameters in IRT models are the discrimination (a) and location (b) parameters. Discrimination parameters are analogous to factor loadings and describe how strongly each individual item relates to the latent trait (a discrimination value of 0.80 is roughly equivalent to a standardized factor loading of.40; de Ayala, 2013). Location parameters (difficulties, intercepts, or thresholds depending on the parameterization used) are similar to intercepts in CFA and express the level of the latent trait at which individuals are more likely to endorse a higher response category. Together, location and discrimination parameters provide detailed information about both scale and test functioning. These parameters are also useful when the aim is to assess understudied or ambiguously defined constructs such as fear of abuse and of an abusive partner, for example, by highlighting which experiences are most strongly associated with the construct generally, and with lower and higher scores on the construct specifically.

IRT offers many advantages over other psychometric frameworks (Borsboom, 2005). For example, IRT parameter estimates are generally sample invariant, meaning that scale development results from IRT analyses more readily generalize than those based on the popular coefficient alpha (de Ayala, 2013; Hambleton & Swaminathan, 2013; Markus & Borsboom, 2013). To the extent parameter estimates are not invariant across certain populations, it can be easier to investigate psychometric bias within the context of IRT models (i.e., investigations of differential item functioning). IRT also provides a more comprehensive approach to reliability such that scale and item precision is conditional on the attribute being assessed (Embretson & Reise, 2013; Hambleton & Swaminathan, 2013); instead of a single number, reliability values are bound to certain levels of the latent trait. For example, certain items might demonstrate considerable precision when measuring individuals at average and above average levels of fear, while simultaneously demonstrating less precision when measuring individuals at below average levels. Practically, it is possible to make more nuanced distinctions among individuals where reliability is greatest. Thanks in part to the descriptive item parameters and conditional nature of reliability, IRT is well-suited for identifying particularly weak or strong items, as well as where additional items add value (de Ayala, 2013; Hambleton & Swaminathan, 2013).

Current Study

The overarching purpose of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of a multi-item scale measuring fear of an abusive partner and/or the abuse they perpetrate across two studies of IPV with distinct samples. The goals are to: 1) Assess the dimensional structure of the scale; 2) Evaluate item and scale-level properties using item response modeling; and 3) Examine the associations between the IPV Fear-11 Scale and a set of relevant external correlates (depression, posttraumatic stress, and physical abuse).

Method

Participants

Participants were women in the New England area enrolled into two separate research studies centered on IPV. Participants self-reported a range of psychological and physical IPV from minor violence (e.g., pushing, grabbing) to severe violence (e.g., hospital visits, being beat up) in a current intimate relationship with a male partner. The first study was used as the calibration sample and the second as the confirmation sample (Smith et al., 2000).

Procedures

Sample 1: Calibration Sample.

The calibration sample is a study of use of IPV aggression among 412 women in relationships with men. The purpose of the original study was to develop a theory of women’s use of aggression in intimate relationships with men (Caldwell et al., 2009). Participants were eligible if they: 1) self-identified as Black or African American, White, or Latina; 2) had a yearly family income of no more than $50,000 (determined a priori to reduce income disparities among racial/ethnic groups); and 3) used at least one act of physical aggression against a male intimate partner in the previous 6 months, regardless of the motive for that aggression. Participants were recruited from the community by posting flyers advertising the Women’s Relationship Study in local businesses such as grocery stores, nail salons, laundromats, and shops; selected state offices such as the Department of Employment; and in primary care clinics and emergency departments. Participants were interviewed by trained research assistants. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, lasted approximately two hours and were administered via computer-assisted interviewing. Participants were compensated $50 for their time.

Sample 2: Confirmation Sample.

The confirmation sample comes from a study of IPV victimization among 298 women. The purpose of the original study was to understand criminal protection orders and their associations with women’s wellbeing (Sullivan, Weiss, Woerner, et al., 2021). Participants were recruited from local courthouses and were eligible if: 1) they were a victim in a criminal IPV case by a male partner; 2) their partner was arraigned approximately 12 to 15 months prior to study recruitment; and 3) they spoke English or Spanish. Eligibility criteria were determined via records from the Family Violence Victim Advocates Office or the State of Connecticut Judicial Branch and confirmed via phone screen. Eligible participants were invited to complete a two-and-a-half-hour confidential interview face-to-face with a trained research assistant in English or Spanish via computer-assisted interviewing. Participants answered questions about the 30 days prior to the interview as well as the 30 days before their partner was arraigned (which was approximately 12–15 months prior to the interview). Participants were compensated $50 for their time. Data for this analysis pertain to the 30 days prior to the partner’s arraignment.

Measures

The next section describes measures used for the IRT psychometric analysis and those measures used to examine the associations between the IPV Fear-11 Scale and relevant external correlates, namely, depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and physical victimization.

Measures for IRT

Fear of an abusive partner and/or the abuse they perpetrate.

In both samples, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements pertaining to IPV-related fear. Response options were on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree), 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater levels of fear. The scale consisted of 11 or 12 items; one item (“I worry that my partner will hurt my children”) was removed from administration subsequent to the calibration sample study because endorsement of it could trigger mandatory reporting of child maltreatment. This item was not administered in the confirmation sample and therefore, dropped from analysis. Item 10 was reversed coded. In the confirmation sample, 8 participants chose “does not apply” for all Fear items and were not included in analyses. See Appendix A for items and scoring instructions. Descriptive statistics for the two samples were: Calibration Sample (M=23.67, SD=6.75); Confirmation Sample (M=29.89, SD=9.61) (t=10.13, p<0.001).

Measures for External Associations

Depression symptoms.

Depression was assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977). This measure assesses recent depressive symptoms with response options ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Scores were reverse coded as indicated and summed. Scores of at least 16 indicate a person is at risk for clinical depression. In the calibration and confirmation samples, respectively, internal reliability was α=.83 and α=.77 and the average was M =22.55 (SD = 12.24) and M=24.61 (SD=14.50). The CESD has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity and is widely used to assess depression across several populations, including IPV survivors (Beekman et al., 1997; Orme et al., 1986). Additionally, norms for the CES-D have been established in an adult sample (Crawford et al., 2011). The confirmation sample had significantly higher depression symptom severity (t=−2.04, p=.042) than the calibration sample.

Posttraumatic Stress symptoms.

Posttraumatic symptom severity was assessed using the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995). Participants indicated the frequency with which they experienced each of the 17 DSM-IV symptoms within the past 30 days (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Response options ranged from 0 (not at all or only one time) to 3 (5 or more times a week or almost always). The 17 symptom severity items were summed, where higher scores indicated greater symptom severity. The PDS’s normative sample included participants who had experienced, witnessed or been confronted with a traumatic event within the prior month between the ages of 18 and 65. The PDS manual reports the normative samples were predominately White, low- and upper income, could read or write English, and were recruited from healthcare, community, treatment, or research institutions. This version of the PDS has been validated and found to be internally consistent (Foa et al., 1997). In the calibration and confirmation samples, respectively, internal reliability was α=.90 and α=.94 and the average was M=18.37, SD=10.85 and M=19.43, SD=14.20. The confirmation sample had significantly higher PTSD symptom severity (t=−12.48, p=<.001) than the calibration sample.

Physical Victimization.

Physical victimization was assessed using the 12-item physical assault subscale from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus, 2017; Straus et al., 1996). The CTS-2 has been evidenced to be a reliable and valid measure of IPV victimization. In the calibration sample, response options were coded as follows: 0 (never), 1 (once), 2 (twice), 3 (3–5 times), 4 (6–10 times), 5 (more than 10 times), and 6 (not in the past 6 months but it happened before). Response option 6 was recoded as 0 to limit the assessment to occurrences in the past 6 months. Response options 3, 4, and 5 were recoded to the midpoint: (3–5 times) was recoded to 4; (6–10 times) was recoded to 8; and (more than 10 times) was recoded to 11 (Straus et al., 2003). The 12 items were summed to create a total score, which ranged from 0 to 111 (M=18.03, SD=22.97). In the calibration sample, α=87.

In the confirmation sample, the CTS-2 response options were coded slightly differently and according to the published measure where response option 5 represented 11 to 20 times, and response option 6 represented more than 20 times. Identical to the calibration sample, responses were recoded to the midpoint. Responses of 11 to 20 times were recoded to 15 and responses of More than 20 times were recoded to 25 (Strauss, 2004). The items were summed to create a total score, which ranged from 0 to 229 (M=21.04, SD = 35.59). In the confirmation sample, α=.93. Rates of physical IPV victimization between the two samples were not significantly different (t=−1.36, p=.17).

Data Analysis Plan

The primary analyses consisted of three major steps, each conducted with both samples: 1) item factor analyses to examine the factor structure of the IPV Fear-11 Scale; 2) item response models to characterize the scale’s psychometric properties; and 3) examination of the scale’s external associations with depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and physical victimization. All analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2021) using either the mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV; step 1), or the full information maximum likelihood estimator (FIML; steps 2 and 3).

Step 1: Dimensionality Analysis

First, to examine the dimensional structure of the IPV Fear-11 Scale we conducted item factor analyses (IFA; Wirth & Edwards, 2007), which are exploratory factor analyses for categorical, item-level data. This was done to understand the general structure of the scale and because unidimensionality (i.e., all items exclusively related to a single latent factor) – or effective unidimensionality – is an assumption of many item response models (Slocum-Gori, Zumbo, Michalos, & Diener, 2009; Slocum-Gori & Zumbo, 2011; Wirth & Edwards, 2007).

Step 2. Item Response Analysis

Second, we fit graded response models (GRM; Samejima, 1969; Samejima, 2010) to the fear scale. The GRM is a popular, unidimensional item response model for scales with polytomous items, or items with more than two response categories. For the evaluation of the scale here, we specifically focus on the item discrimination parameters, item information curves, and test information curves. This helps to highlight those items that are most strongly related to fear, and where along the fear trait the items and full scale are most reliable (e.g., equally, more, or less reliable for higher versus lower fear individuals).

Step 2a. GRM discrimination parameters.

Discrimination parameters index how strongly each individual item is related to the latent trait. As noted, discrimination parameters are analogous to factor loadings in CFA models with continuous indicators, but typically are on a logistic metric as opposed to a standardized metric (though alternative parametrizations are sometimes used). Conceptually, discrimination values tell how capable an individual item is at differentiating between individuals at different levels of the latent trait (e.g., high and low fear; location parameters determine where along the latent trait items are most discriminating). A commonly used minimal threshold for discrimination values is 0.80, which corresponds to a standardized factor loading of around λ = .40 (de Ayala, 2013). Items with discrimination values below α = 0.80 were flagged for follow-up (i.e., potential removal or revision).

Step 2b. GRM information curves.

In item response models, reliability is captured via the concept of information. Information curves graphically depict how reliably individual items and the entire scale measure the latent trait (i.e., IPV-related fear) across different levels. Information is a joint function of the discrimination and location parameters; items that are more discriminating provide more information, and they specifically provide information around the location parameters. Information values are originally computed as logits, but can be converted into rough estimates of reliability to improve interpretability. For example, 4 logits of information correspond to a reliability of approximately 0.75 (Thissen & Orlando, 2001). Accordingly, the information curves here were used to examine how reliable the scale is generally (i.e., across a reasonable span of the latent fear trait), and whether the scale is particularly informative (or uninformative) for individuals within specific ranges of the trait (e.g., if it is particularly reliable for assessing high levels of fear).

Step 3. External Associations for Construct Validity

To assess construct validity, we examined the degree to which the IPV Fear-11 Scale was related to depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and physical victimization. These covariates were selected due to their conceptual and empirical relevance to IPV-related fear (Cheng & Lo, 2019; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hebenstreit et al., 2015; Salcioglu et al., 2017).

Power analysis.

Separately, we conducted a power analysis. The recommended minimum sample size for a graded response model is N=500 (de Ayala, 2013). The calibration sample falls a little short of this (N=412) and the validation sample is smaller (N=288). A brief Monte Carlo simulation analysis however, suggested that the current sample sizes are adequate given that the IPV Fear-11 Scale contains a small number (N=11) of highly correlated items (i.e., across samples standardized factor loadings were λ = .50 and .95). In the Monte Carlo analyses, item parameter estimates from the calibration sample were used as the population values and graded responses were fit with sample sizes of either N=412 or N=288; 1,000 models were fit for each sample size. Regardless of sample size, the item parameter estimates across replications were accurate and precise. For example, as noted, the item discrimination values were generally large in magnitude (average estimated discrimination value across conditions was a = 2.35), however the variability across replications was small (average standard deviation in item discrimination values across replications of .23 for N=412 and .28 for N=288). This precision in the estimates was accurately reflected in the standard error estimates across replications (average standard error estimate across items of .22 for N=412 and .28 for N=288).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Calibration sample

Participants ranged from 18 to 65 years of age (M=36.61, SD=8.92). Approximately 38% were Hispanic, 36.4% were Black/African American, and 27% were White. Approximately 60% of participants completed high school education or less; 25% completed higher education; 9% received a GED, and 6% completed vocational school. About half of participants were currently unemployed, 29% were employed fulltime, 20% were employed part-time, and approximately 3% were never employed or not in the labor force. The majority of participants reported household income of less than $20,000 per year with 42% having less than $10,000. Approximately 15% reported income between $20,000 to $40,000. Only 4% of participants reported income greater than $40,000 per year. Despite being recruited based on use of aggression, 89.6% experienced physical IPV by their current partner.

Confirmation sample

Participants ranged from 18 to 75 years of age (M=36.39, SD=11.28). Approximately 17% of participants were Hispanic, 50% were Black/African American, 29% were White, and 4% identified as multi-racial or another race. In this sample, approximately 60% of participants completed high school education or less; 48% reported completion of higher education. About half of the participants were currently unemployed, 29% were employed fulltime, 20% employed part-time, and approximately 3% were never employed or not in the labor force. On average, household income per month was $1,519, ranging from $0 to $6,400.

Cross-sample comparisons

To test for demographic differences across samples, we harmonized and merged the two datasets. Because most demographic variables were collected differently across studies (e.g., different response options or measurement approach) many variables were not able to be merged without significant loss of information (i.e., race/ethnicity). Nonetheless, we expected there would be racial differences across the two samples because the Calibration sample required recruitment stratified by race/ethnicity. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to assess differences between continuous variables. Chi-square tests were conducted for categorical variables. There were no significant differences between the samples in age (t=−0.29, p=0.39), income (t=1.24, p=0.12), or number of children (t=−0.72, p=0.24). There were significant differences in regard to employment status such that the confirmation sample had a greater number of individuals who were working fulltime (X2=26.78, p<.001).

(1). To Assess the Dimensional Structure of the IPV Fear-11 Scale: Item Factor Analyses

The first goal of this study was to assess the dimensional structure of the IPV Fear-11 Scale. The IFAs in both the calibration and confirmation samples suggested that the scale is largely unidimensional (Slocum-Gori & Zumbo, 2011). The first eigenvalue was considerably larger than the second and subsequent values (Figure 1), and all items loaded non-trivially onto the single factor in a one factor solution (average λ = 0.76 and 0.83, respectively). Furthermore, factor solutions with more than one factor were not conceptually meaningful, and factor intercorrelations were large (rs around 0.70).

Figure 1.

First 11 eigenvalues from the item factor analyses.

(2). To Evaluate Item and Scale-level Properties Using Item Response Modeling: Graded Response Models

The second goal was to evaluate item and scale-level properties using item response modeling. Table 1 presents the item discrimination values from the GRMs, along with standardized factor loadings. All items were adequately discriminating, with values universally above 0.80 (average a of 2.32 and 3.02 in the calibration and confirmation samples, respectively; average λ of 0.73 and 0.81). This indicates that all items were strongly related to the overarching fear factor.

Table 1.

Items, discrimination values and standardized factor loadings for 11-item IPV Fear Scale.

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Sample (n=412; M=23.67, SD=6.75)) | Confirmation Sample (n=298; M=29.89, SD=9.61) | |||

|

| ||||

| Discrimination (a) | Standardized Factor Loading (λ) | Discrimination (a) | Standardized Factor Loading (λ) | |

| 1. I watched what I did to try to avoid setting off my partner | 1.17 | 0.54 | 2.47 | 0.81 |

| 2. I avoided talking to people that might make my partner jealous | 1.10 | 0.52 | 1.83 | 0.71 |

| 3. I tried hard not to make my partner angry | 1.09 | 0.51 | 1.98 | 0.74 |

| 4. I was afraid of my partner | 3.73 | 0.90 | 6.01 | 0.96 |

| 5. My partner scared me sometimes | 3.72 | 0.90 | 4.87 | 0.94 |

| 6. I did what my partner told me to do to avoid making him angry | 2.01 | 0.74 | 2.16 | 0.77 |

| 7. Sometimes I got scared of what my partner might do to me | 4.48 | 0.93 | 4.83 | 0.94 |

| 8. I think my partner could really hurt me one of these days | 2.38 | 0.80 | 3.31 | 0.88 |

| 9. I would have liked to leave my relationship, but I was worried about what my partner would do to me | 1.94 | 0.73 | 2.08 | 0.75 |

| 10. I felt safe that my partner would not hurt me (reverse coded) | 2.00 | 0.74 | 1.64 | 0.67 |

| 11. People who are close to me worried that my partner would hurt me | 1.89 | 0.72 | 2.02 | 0.74 |

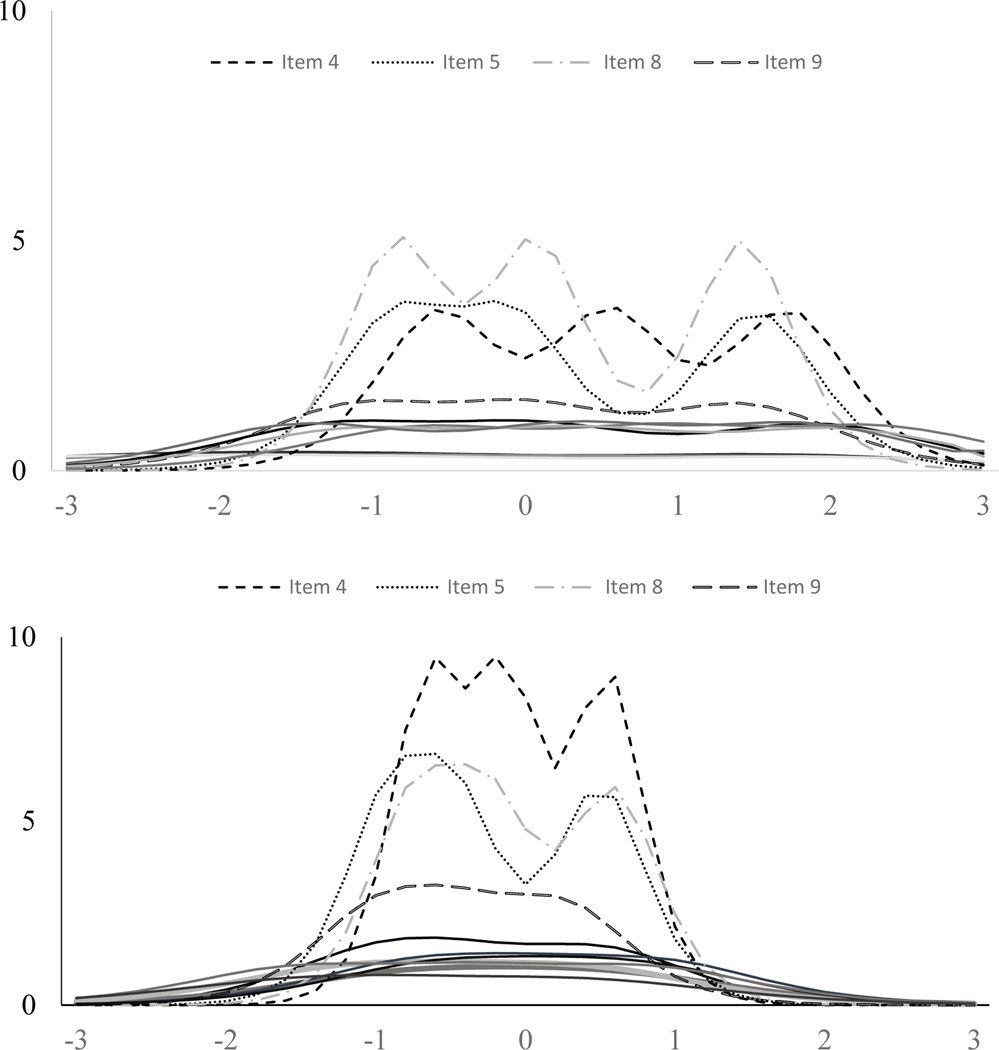

Information logits at the item and scale level at selected intervals of the latent trait (within 2 standard deviations from the mean) are in Table 2. The total scale information curves are also presented graphically in Figure 2. Overall, the total scale appeared largely reliable, with average reliability estimates (i.e., provided within 2 standard deviations of the mean) of rxx = .83 and rxx =.86 for the calibration and confirmation samples, respectively. The calibration sample provided the most information (up to 19 information logits) between −0.80 and 1.5 standard deviations from the mean. The confirmation sample provided the most information (up to 35 information logits) between the mean and 1 standard deviation above the mean (see Table 2). Individual items similarly tended to provide the most information above the mean.

Table 2.

Information and reliability for the 11-item fear scale

| Information at different trait levels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Calibration Sample (n=412) | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| rxx=0.83 | 5.05 | 17.03 | 18.39 | 13.56 | 12.53 |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| 2 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| 4 | 0.07 | 1.92 | 2.45 | 2.41 | 2.71 |

| 5 | 0.18 | 3.21 | 3.45 | 1.70 | 1.70 |

| 6 | 0.60 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.80 | 1.01 |

| 7 | 0.11 | 4.45 | 5.03 | 2.48 | 1.33 |

| 8 | 0.54 | 1.53 | 1.55 | 1.34 | 0.93 |

| 9 | 0.25 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 1.00 |

| 10 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 11 | 0.48 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Confirmation Sample (n=288) | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|

| |||||

| rxx=0.86 | 4.74 | 24.93 | 28.96 | 14.60 | 2.73 |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 0.42 | 1.71 | 1.66 | 1.07 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 0.32 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 0.21 |

| 3 | 0.59 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 0.73 | 0.16 |

| 4 | 0.01 | 3.51 | 8.36 | 2.14 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 0.10 | 5.71 | 3.28 | 1.79 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 1.41 | 1.23 | 0.36 |

| 7 | 0.05 | 3.93 | 4.78 | 2.48 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 0.34 | 2.98 | 3.01 | 0.78 | 0.03 |

| 9 | 0.23 | 0.97 | 1.33 | 1.07 | 0.29 |

| 10 | 0.83 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 0.31 |

| 11 | 0.59 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.17 |

Note. rxx = average scale reliability between ± 2 standard deviations from the mean

Figure 2.

Total Scale Information Curves for both samples

Notably, across both samples, there were four items that stood out as particularly informative: items 4, 5, 7, and 8. These four items, by themselves, provide more than 4.00 logits of information (i.e., are reliable to at least rxx = .75) across much of the latent fear trait. Figures 3a and 3b display the information curves for these four items with dotted lines and the rest of the items in solid greyscale. Accordingly, in supplemental graded response models, we briefly explored the psychometric properties of an abbreviated version of the scale with just these 4 items, as it could be useful in contexts where rapid assessment of IPV-related fear may be necessary. Tables 3 and 4 present the results of these models. All item discrimination values were above 0.80 (Table 3), and at least 4.00 logits of information were provided by the total abbreviated scale from the mean to 2 standard deviations above the mean (Table 4). Below the mean, as was the case in the full scale, information logits dropped slightly below the recommended standard reliability thresholds, indicating the 4-item scale is relatively less reliable at differentiating between lower levels of fear than higher levels. Finally, we found that the correlation between the 4- and 11-item scales for both samples was strong and statistically significant (r=0.92, r=0.94).

Figure 3a and 3b.

Item Information Curves for Calibration Sample and Confirmation Sample

Table 3.

Discrimination values and standardized factor loadings for a 4-item Fear Scale.

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Sample (n=412) | Confirmation Sample (n=298) | |||

|

| ||||

| Discrimination Values | Standardized Values | Discrimination Values | Standardized Values | |

| 4. I was afraid of my partner | 3.48 | 0.89 | 5.26 | 0.95 |

| 5. My partner scared me sometimes | 4.13 | 0.92 | 5.08 | 0.94 |

| 7. Sometimes I got scared of what my partner might do to me | 5.34 | 0.95 | 5.81 | 0.95 |

| 8. I think my partner could really hurt me one of these days | 2.29 | 0.78 | 3.36 | 0.88 |

Table 4.

Information and Reliability for a 4-item Fear scale

| Information at different trait levels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r xx | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Calibration Sample (n=412) | 0.86 | 1.84 | 14.02 | 15.86 | 9.77 | 6.76 |

| Confirmation Sample (n=298) | 0.63 | 1.49 | 19.17 | 19.65 | 8.09 | 1.07 |

Note. rxx = average scale reliability between ± 2 standard deviations from the mean

(3). To Examine Construct Validity Between the IPV Fear-11 Scale and a Set of Relevant External Correlates

Our final goal was to examine associations between the 11- and 4-item scales and depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and physical victimization. In the calibration and confirmation samples, respectively, the 11-item scale was moderately to strongly correlated with depression symptoms (average r = 0.28, r = 0.53), posttraumatic stress symptoms (average r = .48, r = 0.67), and physical victimization (average r = 0.48, r = 0.50). The 4-item scale also was moderately to strongly correlated with depression symptoms (average r = 0.27, r = 0.49), posttraumatic stress symptoms (average r = .45, r = 0.62), and physical victimization (average r = 0.46, r = 0.45).

Discussion

This study developed and rigorously assessed the psychometric properties of a multi-item scale that measures women’s fear of an abusive male partner and/or fear of the abuse they perpetrate. The primary goals of this analysis were to (1) assess the dimensional structure and (2) evaluate item and scale-level properties of the IPV Fear-11 Scale and (3) examine its associations to relevant external correlates.

Overall, the IPV Fear-11 Scale is psychometrically robust across two distinct samples. All items were highly discriminating, and the full scale was reliable across the range of the latent fear trait. Researchers and practitioners can feel confident in using this scale across the fear spectrum. With that said, reliability was particularly high for measuring individuals experiencing moderate to high levels of fear (between two standard deviations below and three standard deviations above the mean). This is not to say that the scale does not perform well among individuals with low levels of fear – it does. However, from a utility perspective, the scale is exceptionally reliable among populations experiencing the greatest level of fear – perhaps those that are of most concern to clinicians. Among populations who are experiencing no fear or very little fear of an abusive male partner or the abuse they perpetrate, the scale can reliably detect those low levels of fear but cannot make distinctions that are as fine-grained as those at moderate or high levels of fear.

One goal of this analysis was to examine associations between the IPV Fear-11 Scale and a set of relevant external correlates (i.e., depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and physical abuse). The IPV Fear-11 scale performed as expected regarding associations with these potential covariates that have demonstrated conceptual and empirical relevance to the construct of IPV-related fear (Cheng & Lo, 2019; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hebenstreit et al., 2015; Salcioglu et al., 2017). Consistent with extant literature, the IPV Fear-11 Scale was positively correlated with depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms and physical victimization.

A final takeaway from this analysis was that across both samples, there were four exceptionally informative items that, taken together, provided a brief yet reliable assessment of fear. Additionally, the full and abbreviated versions of the scale were strongly correlated (r = 0.92, r = 0.94). This suggests that these four items are critical when measuring the construct of fear and that a 4-item abbreviated version of the IPV Fear-11 Scale could be used when necessary. Indeed, the full 11-item scale is more reliable and provides more information across different levels of the latent trait; however, in time-limited clinical contexts or in a brief research protocol, the abbreviated version of the scale may be appropriate.

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted with consideration for the following limitations. For IRT models with polytomous data, it is generally recommended to have a calibration sample of at least 500 respondents (de Ayala, 2013). Although our calibration (N = 412) and confirmation (N=288) samples fall short of this benchmark, the relatively small number of items, and consistency in results across two samples, bolster confidence in the parameter estimates and general functioning of the scale (i.e., although individual item parameters may not be estimated as precisely as possible, the major trends in terms of item discrimination and reliability are likely stable). Further, results of a Monte Carlo simulation analysis suggested that the sample sizes are adequate given the small number of items on the scale. Results presented here generalize both to women who experience IPV or use IPV against male partners, with note that differences in physical victimization between the two samples were non-significant. This study did not examine how IPV-related fear differs in non-heterosexual relationships, how it may be experienced differently by male victims of IPV, or how it may differ as a function of victims’ racial/ethnic background, and/or cultural beliefs.

Future Research Directions

The results of this analysis point to several directions for future inquiry. Most notably, a validated standardized measure of fear could lead to the inclusion of the IPV Fear-11 Scale in future research, which has the potential to elucidate new information about the mechanisms and impact IPV-related fear has on survivors. Although the IPV Fear-11 Scale performed reliably in two distinct samples, future research should continue to test and validate the scale across diverse samples including among individuals not already identified as having experienced IPV, and those experiencing psychological IPV only. The samples in this study were largely racial or ethnic minority adults in relationships with male partners. Future research could benefit from testing the IPV Fear-11 Scale in non-heterosexual couple samples and among younger individuals; Hamby and Turner (2013) specifically called for greater diversity in approaches for measuring fear of IPV among samples of teen victims of dating violence. Additional studies should explore the extent to which resources, including income, are related to fear. This is an important question to be investigated in future research that has policy and practice implications, but one that is beyond the scope of this study. Relatedly, results point to a need to examine fear of IPV over time. Future lines of inquiry should examine longitudinal measure invariance—whether the Fear-11 scale remains a stable and reliable measure of fear both over time and in different contexts of IPV. Finally, the results here suggest that an abbreviated form of the IPV Fear-11 scale may be able to function as a suitable stand-in for the full form in contexts that require brief assessment. Future work could more thoroughly evaluate the potential abbreviated form in independent samples to better assess its suitability as a stand-alone assessment.

The IPV Fear-11 Scale functioned well across two independent samples and, given the substantive differences between these samples, we can infer the scale can differentiate fear in distinct populations. However, future research should more thoroughly examine the extent to which the measurement properties detailed in this study differ across these populations (i.e., tests of differential item functioning).

Last, findings of existing studies reveal that fear can differentiate subgroups of victims (Hamberger & Guse, 2005), but little work has been conducted beyond that to understand the role of fear in producing different outcomes. The IPV Fear-11 scale can play an important role in elucidating the ways fear differentiates subgroups of victims and is associated with unique outcomes. Work such as this may have implications for intervention development and differential responses to interventions.

Prevention, Clinical, and Policy Implications

Findings of this IRT analysis afford researchers a rigorously evaluated, validated, multi-item assessment of IPV-related fear. Appendix A provides survey administration instructions, items, and scoring. The results of this study suggest the IPV Fear-11 scale will perform when administered as an online survey, paper-pen format, or interview as a survey with IPV survivors. This scale can be utilized in research, community and clinical settings. In research settings, standardizing the assessment of fear is critical to building confidence in findings that inform the development of policies and interventions, for example in the context of developing criminal justice system policies about the pretrial assessment period when appropriate sanctions are being determined. Relatedly, in research settings, administration of the IPV Fear-11 Scale would allow comparisons across samples. In community settings, by assessing level of fear, advocates at domestic violence service providing agencies may be able to better assess their clients’ needs and better match them to the most relevant services, for example, by providing immediate support vs. making a referral elsewhere for services. In clinical settings, a more precise measurement of fear in the context of IPV can have wide-reaching implications for the approaches practitioners take to meeting the needs of victims, and thus mitigating the effects of fear. And finally, in both community and clinical settings, providers may choose to use this scale as a tool to evaluate the impact of their interventions on client’s level of fear. In sum, the IPV Fear-11 Scale is a short, easily administered and psychometrically sound scale that shows promise across multiple settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Nos. 2012-IJ-CX-0045 and 2001-WT-BX-0502, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute of Justice. Support was also provided by NIH grant T32 DA019426 (DC).

Footnotes

IPV is inclusive of coercive control and other psychologically abusive behaviors, which can instill fear regardless of if physical abuse occurs. Relatedly, we do not see fear of partner and fear of IPV as distinct in the context of relationships where IPV occurs. To reflect this thinking and to be consistent, we refer to the Fear-11 Scale as measuring fear of abusive partner and/or the abuse they perpetrate.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Deeg D, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries M, & Van Tilburg W (1997). Brief communication.: criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D (2005). Measuring the mind: Conceptual issues in contemporary psychometrics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Allen CT, Sullivan TP, & Snow DL (2009). Why I Hit Him: Women’s Reasons for Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(7), 672–697. 10.1080/10926770903231783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C, Kothari CL, Dichter M, Marcus S, Wiley J, & Rhodes KV (2014). Victim participation in intimate partner violence prosecution: Implications for safety. Violence Against Women, 20(5), 539–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TC, & Lo CC (2019). Health of Women Surviving Intimate Partner Violence: Impact of Injury and Fear. Health & Social Work, 44(2), 87–94. 10.1093/hsw/hlz003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Cayley C, Lovibond PF, Wilson PH, & Hartley C (2011). Percentile norms and accompanying interval estimates from an Australian general adult population sample for self‐report mood scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES‐D, DASS, DASS‐21, STAI‐X, STAI‐Y, SRDS, and SRAS). Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- de Ayala R (2013). The IRT tradition and its applications. The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods, 1, 144e169. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, & Reise SP (2013). Item response theory. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB, Messner SF, Hoskin AW, & Deane G (2002). Reasons for Reporting and Not Reporting Domestic Violence to the Police. Criminology, 40(3), 617–648. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00968.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB (1995). Posttraumatic stress diagnostic scale manual. National Computer Systems Pearson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, & Perry K (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK (2005). Men’s and women’s use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples: toward a gender-sensitive analysis. Violence & Victims, 20(2), 131–151. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16075663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, & Guse C (2005). Typology of reactions to intimate partner violence among men and women arrested for partner violence. Violence & Victims, 20(3), 303–317. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16180369 https://connect.springerpub.com/content/sgrvv/20/3/303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton RK, & Swaminathan H (2013). Item response theory: Principles and applications. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, & Turner H (2013). Measuring teen dating violence in males and females: Insights from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. Psychol Violence, 3(4), 323. [Google Scholar]

- Hebenstreit CL, Maguen S, Koo KH, & DePrince AP (2015). Latent profiles of PTSD symptoms in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 122–128. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Rhodes KV, Kemball RS, Click L, Cerulli C, McNutt LA, & Kaslow NJ (2008). Differences in Female and Male Victims and Perpetrators of Partner Violence With Respect to WEB Scores. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(8), 1041–1055. 10.1177/0886260507313969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivany AS, Bullock L, Schminkey D, Wells K, Sharps P, & Kools S (2018). Living in Fear and Prioritizing Safety: Exploring Women’s Lives After Traumatic Brain Injury From Intimate Partner Violence. Qualitative Health Research, 28(11), 1708–1718. 10.1177/1049732318786705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquier V, & Sullivan TP (2014). Fear of Past Abusive Partner(s) Impacts Current Posttraumatic Stress Among Women Experiencing Partner Violence. Violence Against Women, 20(2), 208–227. 10.1177/1077801214525802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Neidig P, & Thorn G (1995). Violent marriages: Gender differences in levels of current violence and past abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 10(2), 159–176. 10.1007/BF02110598.pdf [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, & Lynch KR (2018). Dangerous Liaisons: Examining the Connection of Stalking and Gun Threats Among Partner Abuse Victims. Violence & Victims, 33(3), 399–416. 10.1891/0886-6708.v33.i3.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus KA, & Borsboom D (2013). Frontiers of test validity theory: Measurement, causation, and meaning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Foran H, & Cohen S (2013). Validation of Fear of Partner Scale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(4), 502–514. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EC, Kerker BD, McVeigh KH, Stayton C, Wye GV, & Thorpe L (2008). Profiling risk of fear of an intimate partner among men and women. Preventive Medicine, 47(5), 559–564. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme JG, Reis J, & Herz EJ (1986). Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES‐D) scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(1), 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE (1993). Fear of victimization and health. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 9(2), 159–175. 10.1007/BF01071166.pdf [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM (2012). Self-reported fear in partner violent relationships: Findings on gender differences from two samples. Psychol Violence, 2(1), 58–74. 10.1037/a0026285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco VF (1990). Gender, fear, and victimization: A preliminary application of power‐control theory. Sociological Spectrum, 10(4), 485–506. 10.1080/02732173.1990.9981942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett LA, & Saunders DG (1999). The impact of different forms of psychological abuse on battered women. Violence and Victims, 14(1), 105–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcioglu E, Urhan S, Pirinccioglu T, & Aydin S (2017). Anticipatory fear and helplessness predict PTSD and depression in domestic violence survivors. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 9(1), 117–125. 10.1037/tra0000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocum-Gori SL, & Zumbo BD (2011). Assessing the unidimensionality of psychological scales: Using multiple criteria from factor analysis. Social Indicators Research, 102(3), 443–461. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, & Anderson KG (2000). On the sins of short-form development. Psychological Assessment, 12(1), 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Earp JA, & DeVellis R (1995). Measuring battering: development of the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale. Women’s Health: Research on Gender, Behavior, & Policy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2017). The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: An evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, & Warren WL (2003). The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Price C, & Pugh NE (2021). Criminal Protection Orders for Women Victims of Domestic Violence: Explicating Predictors of Level of Restrictions Among Orders Issued. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), NP643-NP662. 10.1177/0886260517736274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Woerner J, Wyatt J, & Carey C (2019). Criminal Orders of Protection for Domestic Violence: Associated Revictimization, Mental Health, and Well-being Among Victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0(0), 1–22. 10.1177/0886260519883865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Woerner J, Wyatt J, & Carey C (2021). Criminal Orders of Protection for Domestic Violence: Associated Revictimization, Mental Health, and Well-being Among Victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 10198–10219. 10.1177/0886260519883865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, & Orlando M (2001). Item response theory for items scored in two categories. In Test scoring (pp. 85–152). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.