Abstract

Objectives

Research suggests that military personnel frequently delay disclosing mental health issues and illness (MHI), including substance use disorder, to supervisors. This delay causes missed opportunities for support and workplace accommodations which may help to avoid adverse occupational outcomes. The current study aims to examine disclosure-related beliefs, attitudes and needs, to create a better understanding of personnel’s disclosure decision making.

Design

A cross-sectional questionnaire study among military personnel with and without MHI. Beliefs, attitudes and needs regarding the (non-)disclosure decision to a supervisor were examined, including factors associated with (non-)disclosure intentions and decisions. Descriptive and regression (logistic and ordinal) analyses were performed.

Setting

The study took place within the Dutch military.

Participants

Military personnel with MHI (n=324) and without MHI (n=554) were participated in this study.

Outcome measure

(Non-)disclosure intentions and decisions.

Results

Common beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure were the preference to solve one’s own problems (68.3%), the preference for privacy (58.9%) and a variety of stigma-related concerns. Common beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure were that personnel wanted to be their true authentic selves (93.3%) and the desire to act responsibly towards work colleagues (84.5%). The most reported need for future disclosure (96.8%) was having a supervisor who shows an understanding for MHI. The following factors were associated both with non-disclosure intentions and decisions: higher preference for privacy (OR (95% CI))=(1.99 (1.50 to 2.65)intention, 2.05 (1.12 to 3.76)decision) and self-management (OR (95% CI))=(1.64 (1.20 to 2.23)intention, 1.79 (1.00 to 3.20)decision), higher stigma-related concerns (OR (95% CI))=(1.76 (1.12 to 2.77)intention, 2.21 (1.02 to 4.79)decision) and lower quality of supervisor–employee relationship (OR (95% CI))=(0.25 (0.15 to 0.42)intention, 0.47 (0.25 to 0.87)decision).

Conclusion

To facilitate (early-)disclosure to a supervisor, creating opportunities for workplace support, interventions should focus on decreasing stigma and discrimination and align with personnels’ preference for self-management. Furthermore, training is needed for supervisors on how to recognise, and effectively communicate with, personnel with MHI. Focus should also be on improving supervisor–employee relationships.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, Substance misuse, PSYCHIATRY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Disclosure of mental health issues and illness to a supervisor was examined in the military, a context in which little research has been done on this topic.

This study included a group that is usually hard to study, namely military personnel who have not disclosed.

This study included both personnel with and without mental health issues and illness, providing insights for interventions for personnel who may develop mental health issues and illness in the future.

The sample is not representative for the entire military, due to the sampling method.

Due to the cross-sectional design of the study, no causality can be presumed.

Introduction

The decision for workers whether to disclose their mental health issues and illness (MHI), including substance use disorder, to their supervisors can have far-reaching consequences for their sustainable employment.1–4 Disclosure can lead to workplace support and accommodations, which can prevent worsened symptoms and sick leave, and non-disclosure can lead to missed opportunities for this support.2 3 5 However, disclosure can also lead to being stigmatised and discriminated against.6 7

The disclosure dilemma is expected to be even more prominent for trauma-prone occupations, such as the military, where workers are expected to be ‘strong’ and disclosure may yield less positive outcomes.5 8 Additionally, workers in these high-risk occupations are exposed to stressors at work, increasing their risk of developing MHI.9 Previous research in the military showed that there is a high preference for solving one’s own problems,10 there are stigma-related concerns and military personnel tend to delay seeking help.6 11 12 Together this might cause a delay in disclosure to a supervisor. To facilitate (early-)disclosure, so that personnel can receive support which can prevent adverse occupational outcomes,2 3 5 more insight is needed into the (non-)disclosure decision. Although the (non-)disclosure decision is complex and has far-reaching consequences, research on this matter is scarce and mostly qualitative, especially in the military.3 6 11 13 Research has shown that the supervisor plays an important role, where supervisor’s attitude and behaviour can form both a barrier as well as be a facilitator for disclosure.6 14 15 Furthermore, ‘The model of employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work’ proposes that there is a default position of non-disclosure, caused by fear of stigma, wanting to maintain boundaries and maintaining confidentiality.16 This model proposes that a triggering incident is needed before a disclosure decision is made.16

The aim of the current study was to gain insight into the (non-)disclosure decision to a supervisor in the military, and to confirm and expand earlier qualitative findings.6 This was done by examining beliefs, attitudes and needs related to disclosure to a supervisor. Based on earlier qualitative research on disclosure in the military,6 11 studies on disclosure among Dutch workers17 18 and literature reviews on disclosure,2 19 it was hypothesised that the following beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure would be important for, and associated with, the disclosure decision: stigma-related concerns (eg, social rejection), preference for self-management and privacy, negative attitudes of the supervisor towards MHI and difficulty talking about MHI. Additionally, the following beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure were hypothesised to be important for the disclosure decision: wanting to be one’s true and authentic self, positive attitudes of the supervisor towards MHI, setting an example, organisational policies, a need for work accommodations, feelings of responsibility, whether MHI affects work functioning, advice from others, and not having a choice due to the visibility of symptoms, having to report sick or needing treatment during work. To inform future interventions, several needs related to disclosure were also assessed, based on earlier qualitative research.6 These needs were related to information on how to disclose and education for supervisors on how to support military personnel with MHI.

As personnel with and without MHI have shown to have different views on treatment seeking,10 12 the current study examined both actual disclosure decisions in personnel with MHI as well as future disclosure intentions for those without MHI. The research questions were: (1) ‘What are beliefs, attitudes and needs of military personnel regarding disclosure to a supervisor?’, (2) ‘Do disclosers, differ from non-disclosers, and if so, how?’ and (3) ‘What factors are associated with non-disclosure to a supervisor?’.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional observational design with an online questionnaire. Comparisons were made based on past disclosure decisions for personnel with MHI and on disclosure intentions for those without MHI. Data collection happened simultaneously with a study on treatment seeking for MHI.12 The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist was used to report this study.20

Setting

This study took place within the Dutch military, where healthcare is organised internally. There are sanctions for use of soft and hard drugs. However, when substance use disorder is reported to a mental health professional, there are confidentiality agreements.10

Patient and public involvement

Different stakeholders from the Dutch military (psychologists, psychiatrists, policymakers and military personnel) were involved in the development of the questionnaire. They provided advice on the language used in the questionnaire to ensure that it was military-appropriate language. They also provided advice on the best way to recruit participants.

Participant recruitment

Active-duty military personnel who have been on deployment in the past 5 years were recruited. To ensure that both personnel with and without MHI would be present in the sample, existing data from a questionnaire personnel receive after deployment was used to select a sample. This questionnaire included scores of depression, aggression, alcohol use and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clinical cut-off scores were used to identify personnel with and without an indication of MHI. Next, a stratified sample, based on gender, age, military division and rank of personnel was approached, half with an indication of MHI (n=1000) and half without (n=1000).

Data were collected between January and February 2021. All personnel were invited at the same time, both by email and a letter. Reminders were sent after 3 and 5 weeks. It was made clear that the responses to the questionnaire would be anonymous.

Measures

Demographics

Gender, age, marital status, education level, type of work (operational or not), military department, rank and years of service were assessed.

Mental health issues and illness

Current MHI

To assess current MHI, the following measures were used; (a) Hospital anxiety and depression scale,21 (b) Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Sceening Tool - Lite for substance use disorder,22 (c) Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test - Concise, for alcohol use23 and (d) PTSD checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5.24 For psychometric properties and cut-off scores, see online supplemental appendix A.

bmjopen-2022-063125supp001.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)

Self-reported MHI

Personnel were asked whether they have (had) MHI. Group membership (ie, current/past MHI or no MHI) was determined based on this. If personnel reported having (had) MHI, they received a list of 15 possible types of MHI (see online supplemental appendix B) and were asked to indicate whether it concerned current or past MHI, in line with earlier research.12 17 25 They were asked whether the MHI was work-related (yes/no) and to rate the severity of their symptoms (during the worst time) on a scale of 0–10.

(Non-)disclosure intentions and decisions

Personnel with MHI were asked whether they had disclosed to their supervisor (yes/no). Personnel without MHI were asked, in case they would develop MHI in the future, whether they would disclose this to their supervisor, using a 4-point scale ranging from very unlikely to very likely.

Beliefs, attitudes and needs

Based on earlier qualitative research on disclosure in the military,6 11 studies on disclosure among Dutch workers17 18 and literature reviews on disclosure,2 3 it was determined which beliefs and attitudes should be assessed. Regarding the beliefs and attitudes, 13 statements pro non-disclosure (eg, I would prefer to solve my own problems) and 11 statements pro disclosure (eg, In order to be your true self, disclosure is important) were developed. Please see the Results section for a full overview of the statements. Stigma was found to be a main barrier to disclosure in our qualitative study.6 Therefore, several stigma-related statements were included. All the statements were assessed by several people working in the military, to assure the questions were appropriate for the military context. The statements were adjusted according to their feedback. Participants were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale to what extent they agreed with the statements, ranging from completely disagree to completely agree.

Personnel without MHI were asked additional questions about their needs regarding disclosure if they would develop MHI in the future. Based on findings from the earlier qualitative study,6 they were given seven options (eg, a supervisor who shows understanding for MHI) and were asked to rate these on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’. Please see the Results section for a full overview of the assessed needs.

(Previous) experience

Familiarity

Participants were asked about MHI in their surroundings using an adaptation of the Level of Contact Report,26 following earlier research.25 27 The total score was used.

Previous experience

Participants were asked whether they had previous experience, and/or seen experiences of others, with disclosure to a supervisor. If yes, they were asked whether this experience was positive or negative.

Work context

Unit cohesion

A three-item measure was used for perceived unit cohesion.28 For example ‘the members of my unit are cooperative with each other’. Items were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘Completely disagree’ to ‘Completely agree’. Mean scores were used. Participants with MHI were asked about unit cohesion at the time they experienced MHI.28

Relationship supervisor

A 6-item measure for the relationship with the supervisor from the Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work was used. This questionnaire is the most used and validated questionnaire for work experiences in the Netherlands.29 Items were measured on a 4-point scale with answer categories ‘Always’, ‘Often’, ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Never’. Mean scores were used, with higher scores indicating better relationship quality. Participants with MHI were asked about the relationship at the time they experienced MHI.

Statistical analyses

For beliefs, attitudes and needs surrounding (non-)disclosure, descriptive analyses were performed. χ2 tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparisons between those who disclosed/intended to disclose and those who did not, as variables were not normally distributed.

To examine factors associated with (non-)disclosure, two separate analyses were performed. For personnel with MHI, a logistic regression was performed with non-disclosure decision as the dependent variable (0=disclosure, 1=non-disclosure). For personnel without MHI, an ordinal regression was performed, as disclosure intention had more than two categories. As the assumption of proportional odds was violated at first, the categories ‘very unlikely’ and ‘unlikely’ were merged, resulting in the dependent variable non-disclosure intention with categories 1=very-likely, 2=likely and 3=(very)-unlikely. To prevent loss of information ‘likely’ and ‘very-likely’ were not combined. Fear of negative career consequences, social rejection, discrimination, self-stigma, shame, fear of receiving blame, fear of gossip and confidentiality concerns were combined into one (mean) measure of stigma, as they are all aspects of stigma.30 Together these items formed a reliable scale (αwith MHI=0.89, αwithout MHI=0.91). There were no missing data, as forced response answers were used during data acquisition and a complete case analysis was used. All analyses were performed using SPSS - 25.

Results

Participant characteristics

Response rate

After removing duplicates (caused by personnel going on multiple deployments) and personnel who had left active service from the original sample, a total of n=1627 eligible respondents were left. Of those, 63% (n=1025) started the questionnaire, and 54% (n=878) fully completed it and were used for further analysis. Compared with personnel who completed the questionnaire, those who did not complete it included more women (χ2(1, n=1008)=6.01, p=0.014), more lower and middle education level (χ2(2, n=1008)=7.25, p=0.027) and more non-commissioned officers (χ2(2, n=1006)=8.26, p=0.016). The majority quit while answering mental health questions.

Non-disclosure (intentions)

Of those with MHI (n=324), 24.4% indicated not having disclosed their MHI to their supervisor. Of those without MHI (n=554), 15.7% did not intend to disclose if they would develop MHI in the future.

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics can be found in table 1. For personnel with MHI, there was a significant association between marital status and non-disclosure decision (χ2(1, n=324)=5.53, p=0.019) with more people with a partner within the non-disclosers group. Those who had not disclosed, reported significantly lower symptom severity (M=6.01) compared with those who had disclosed (M=7.38, U=5885.5, Z=−5.37, p<0.001). For personnel without MHI, there were no significant differences in demographics based on non-disclosure intentions. Information on reported MHI can be found in online supplemental appendix B.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample separated by military personnel with and without mental health issues or illness (MHI)

| Military personnel with MHI | Military personnel without MHI | |||||

| Disclosure, n=245 | Non-disclosure, n=79 | Total, n=324 | Disclosure intention, n=467 | Non-disclosure intention, n=87 | Total, n=554 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 215 (87.8) | 68 (86.1) | 283 (87.4) | 430 (92.1) | 79 (90.8) | 509 (91.9) |

| Female | 30 (12.2) | 11 (13.9) | 41 (12.7) | 37 (7.9) | 8 (9.2) | 45 (8.1) |

| Age | ||||||

| <20 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 21–30 | 15 (6.1) | 12 (15.2) | 27 (8.3) | 55 (11.8) | 10 (11.5) | 65 (11.7) |

| 31–40 | 81 (33.1) | 26 (32.9) | 107 (33.0) | 149 (31.9) | 41 (47.1) | 190 (34.3) |

| 41–50 | 76 (31.0) | 19 (24.1) | 95 (29.3) | 134 (28.7) | 18 (20.7) | 152 (27.4) |

| 51–60 | 68 (27.8) | 21 (26.6) | 89 (27.5) | 119 (25.5) | 17 (19.5) | 136 (24.6) |

| >60 | 5 (2.0) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (1.9) | 10 (2.1) | 1 (1.2) | 11 (2.0) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Partner (vs single) | 183 (74.7) | 69 (87.3) | 252 (77.8) | 394 (84.4) | 76 (87.4) | 470 (84.8) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Low | 26 (10.6) | 4 (5.1) | 30 (9.3) | 49 (10.5) | 2 (2.3) | 51 (9.2) |

| Medium | 136 (55.5) | 39 (49.4) | 175 (54.0) | 242 (51.8) | 48 (55.2) | 290 (52.4) |

| High | 83 (33.9) | 36 (45.6) | 119 (36.7) | 176 (37.7) | 37 (42.5) | 213 (38.5) |

| Work-related context | ||||||

| Type of work | ||||||

| Operational work | 188 (76.7) | 67 (84.8) | 255 (78.7) | 258 (55.3) | 50 (57.5) | 308 (55.6) |

| Military branch | ||||||

| Marine | 20 (8.2) | 2 (2.5) | 22 (6.8) | 75 (16.1) | 16 (18.4) | 91 (16.4) |

| Army | 119 (48.6) | 47 (59.5) | 166 (51.2) | 196 (42.0) | 40 (46.0) | 236 (42.6) |

| Air-force | 69 (28.2) | 15 (19.0) | 84 (25.9) | 120 (25.7) | 15 (17.2) | 135 (24.4) |

| Military-police | 16 (6.5) | 4 (5.1) | 20 (6.2) | 21 (4.5) | 5 (5.7) | 26 (4.7) |

| Staff | 20 (8.2) | 11 (13.9) | 31 (9.6) | 53 (11.3) | 11 (12.6) | 64 (11.6) |

| Other | 1 (.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (.3) | 2 (.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (.4) |

| Ranks | ||||||

| Military personnel | 29 (11.8) | 15 (19.0) | 44 (13.6) | 26 (5.6) | 8 (9.2) | 34 (6.1) |

| Non-commissioned officers | 132 (53.9) | 33 (41.8) | 165 (50.9) | 225 (48.2) | 32 (36.8) | 257 (46.4) |

| Officers | 84 (34.3) | 31 (39.2) | 115 (35.5) | 216 (46.3) | 47 (54.0) | 263 (47.5) |

| Years of service (M (SD)) | ||||||

| Years | 22.25 (9.08) | 21.42 (9.92) | 22.05 (9.28) | 22.20 (9.62) | 20.11 (9.98) | 21.86 (9.70) |

| Mental health-related context | ||||||

| Past or current (self-reported) MHI | ||||||

| Past MHI | 194 (79.2) | 62 (78.5) | 256 (79.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| MHI work related | ||||||

| Yes | 167 (68.2) | 48 (60.8) | 215 (66.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Severity of symptoms | ||||||

| Mean severity (M, SD) | 7.38 (1.87) | 6.01 (2.07) | 7.05 (2.01) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note: Military personnel with MHI were asked about their type of work and rank at the time their MHI started.

Beliefs, attitudes and needs regarding (non-)disclosure to a supervisor

Regarding beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure, personnel preferred to solve their own problems (73.8% with(w/)MHI, 65.2% (without(w/o)MHI)) and preferred privacy (58.3% w/MHI, 59.2% w/oMHI). There were also high stigma-related concerns, with personnel reporting they saw (would see) themselves as weak due to MHI (52.5% w/MHI, 26.4% w/oMHI), had concerns about negative career consequences (35.2% w/MHI, 24.4% w/oMHI) and fear of social rejection (33.0% w/MHI, 20.6% w/oMHI). Only a minority reported that their supervisor had negative attitudes towards MHI (9.3% w/MHI, 4.9% w/oMHI).

As for beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure, the large majority indicated disclosure would allow them to be their true and authentic self (95.7% w/MHI, 91.2% w/oMHI), and believed disclosure was important due to the responsibility belonging to the nature of their work (74.7% w/MHI, 90.3% w/oMHI). In addition, most reported that the military has good policy for those who develop MHI (72.2% w/MHI, 87.9% w/oMHI) and that generally supervisors take MHI seriously (82.4% w/MHI, 87.7% w/oMHI). Furthermore, personnel reported that it matters for the disclosure decision whether MHI influences occupational functioning (69.8% w/MHI, 74.7% w/oMHI) and whether work accommodations are needed (43.5% w/MHI, 62.8% w/oMHI). Of those with MHI who had disclosed, the majority indicated having had no choice, with 69% needing treatment during work hours and 46.9% having to report sick. An overview of all beliefs and attitudes can be found in online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2022-063125supp002.pdf (111.3KB, pdf)

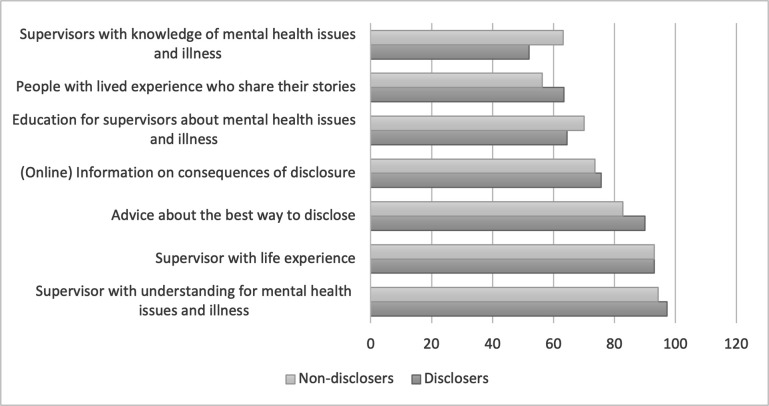

As for needs regarding future disclosure to a supervisor, the highest need was reported for supervisors who show understanding for MHI (96.8%) and have life experience (93.1%) and advise about the best way to disclose (when/where/how) (88.8%). An overview of all needs can be found in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Needs regarding future disclosure.

Differences between disclosers and non-disclosers

Overall, those who did not (intend to) disclose reported significantly higher preference for solving own problems and for privacy, and lower feelings of responsibility due to the nature of their work.

Within personnel with MHI, there was also a significant difference between non-disclosers and disclosers in the following beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure: those who had not disclosed reported MHI having less effect on their occupational functioning, and less need for work accommodations compared with disclosers.

Within personnel without MHI, those who intended to disclose and those who did not, differed significantly on all beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure. For beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure, those with no intention to disclose indicated significantly lower belief that the military has good policy for those with MHI, supervisors taking MHI less seriously, and a lower desire to be a good example to others with MHI. Results with statistics can be found in online supplemental table 1. There were no significant differences in reported needs for future disclosure, based on disclosure intention.

Factors associated with non-disclosure to a supervisor

For personnel with MHI, the logistic regression model with the dependent variable non-disclosure was statistically significant (χ2(24)=149.30, p<0.001) and explained 55.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in non-disclosure and correctly classified 85.0% of cases. The following background variables were significantly associated with non-disclosure: lower symptom severity, having a partner and lower employee–supervisor relationship quality. Additionally, the following beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure were positively associated with non-disclosure: preference for privacy, preference for self-management and stigma-related concerns. Finally, the following beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure were negatively associated with non-disclosure: importance given to disclosure advice from others, MHI having an impact on occupational functioning, and feelings of responsibility due to the nature of work.

For personnel without MHI, the ordinal logistic regression model with the dependent variable non-disclosure intention was statistically significant (χ2(23)=346.90, p<0.001) and explained 53.5% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in non-disclosure intention and correctly classified 66.4% of cases. The following background variables were significantly associated with non-disclosure intention: not having positive earlier experience with disclosing something personal to a supervisor, having seen negative experiences of others with disclosure and lower employee–supervisor relationship quality. Additionally, the following beliefs and attitudes pro non-disclosure were positively associated with non-disclosure intentions: preference for privacy, preference for self-management, stigma-related concerns and finding it difficult to talk about MHI. Finally, the following beliefs and attitudes pro disclosure were negatively associated with non-disclosure intentions: supervisor who takes MHI seriously, needing work accommodations, wanting to be authentic self and wanting to be an example to others with MHI. All results with statistics can be found in online supplemental table 2.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine beliefs, attitudes and needs associated with (non-)disclosure to a supervisor in the military. Non-disclosure was associated with higher stigma-related concerns, a higher preference for privacy and self-management and a lower supervisor–employee relationship. A quarter of personnel with MHI had not disclosed their MHI to their supervisor, and those who had disclosed, appeared to do so after a considerable delay. Important reasons for disclosure were that personnel wanted to be their true and authentic self and thought disclosure was important due to the responsible nature of their work. To consider disclosure, most personnel indicated they would need a supervisor who shows understanding for MHI. Moreover, over 85% expressed a need for advice about the best ways to disclose.

We identified that although the majority of personnel with MHI had disclosed to their supervisor, they appeared to do so after a considerable delay. Those who disclosed had higher symptom severity than non-disclosers and the majority disclosed because they had to call in sick (46.9%) or had needed treatment during work hours (69.0%). This appears to be even more so the case for military personnel, compared with civilians. A study on disclosure among Dutch workers in general showed that 15.6% disclosed due to having to report sick, and 39.9% disclosed due to needing treatment during work.18 This is in line with ‘the model of employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work’, which proposes a default position of non-disclosure and that a triggering incident is needed for disclosure—in this case, having to call in sick or needing treatment.16 This late disclosure causes missed opportunities for workplace support and work accommodations which can prevent worsened symptoms and sick leave.1 31 32

Stigma-related concerns form a barrier for (early-)disclosure. Half of those who had not disclosed, saw themselves as weak for having MHI, experienced shame, and a third feared gossip, negative career consequences, social rejection and discrimination. These stigma-related concerns were significantly associated both with non-disclosure intentions and decisions. Stigma has been found to be a barrier to disclosure before, both in military, other trauma-prone occupations and civilian populations.5 6 16 33 34 When comparing the results of the current study to a study among Dutch civilian workers, it should be noted that of military personnel who had not disclosed, half reported seeing themselves as weak and being ashamed, compared with only 13.5% of civilians.18 Concerns about stigma thus appear to be stronger within the military setting compared with civilian settings. These higher concerns of stigma are likely caused by the military workplace culture and the responsible work nature, where people are expected to be ‘strong’.6 8 It should be noted that the study among civilians predominantly included women, while the current study predominantly included men, which might also account for some of the differences.18 Future research into destigmatising interventions is needed, as up to now only a few, especially in the military, rigorous destigmatising intervention studies have been conducted.1 Trauma risk management is a promising destigmatising programme within (military) organisational settings, as it has shown to improve attitudes towards MHI.35 To facilitate disclosure, stigma should also be targeted at a policy level, to take away some of the fears personnel face.6

The preference for self-management also forms a barrier for (early-)disclosure. Although disclosure rates are comparable to earlier research among Dutch workers in general,17 18 the reasons for non-disclosure differ. Of the non-disclosers, 87.3% reported a preference for self-management, compared with 44.9% of civilians. This is likely also caused by the military workplace culture, where people are expected to have a ‘can-do’ problem fixing mentality.6 To target this preference for self-management, self-help apps or personal recovery programmes could provide personnel the opportunity to manage their own MHI, possibly giving them more confidence in disclosing and a feeling of control, as they are already working on their MHI.36 This could also be done through easily accessible care from, for example, a social worker. Additionally, decision aids and programmes could be implemented, as personnel indicated this as a need, and it can positively influence sustainable employability and coping with stigma.37–40

To facilitate (early-)disclosure, there is an important role for the supervisor. The results showed that lower employee–supervisor relationship quality was associated both with non-disclosure decision and intention. Having seen negative experiences of others with disclosure was the second strongest predictor of non-disclosure intentions, indicating the importance of how others, including supervisors, respond to disclosure. It is also important that military personnel with positive experiences with disclosure communicate openly about these experiences. The previous qualitative study in the Dutch military,6 and a study among Dutch workers in general,18 also showed the importance of supervisor relationships and support.6 Supervisor attitudes towards MHI and knowledge of MHI have also been found to be associated with whether employees disclose to the supervisor themselves, or that the supervisor finds out some other way.41 Finally, supervisor support was not only found to be important for disclosure, but also for treatment seeking for MHI, a decision which is also of influence on sustainable employability.10 To facilitate (early-)disclosure, training may be needed for supervisors to improve understanding and support of MHI needs.42 Additionally, supervisor relationship quality could be addressed, for example by adjusting the obligated job rotation every 3 years, giving personnel longer to build a relationship with their supervisor.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included the large sample and inclusion of a group that is usually hard to study (participants who have not disclosed). Additionally, the study included both personnel with and without MHI, providing insights for interventions for personnel who may develop MHI in the future. Finally, the study examined disclosure in the military where little research has been done on this topic.

As for limitations, the sample was not representative for the entire military, due to the sampling method. This method also caused the sample to include only personnel who have been on deployment. This group might have had more positive attitudes towards MHI and disclosure due to mental health training related to deployment.35

Second, despite stratification, the current study included a sample of older, higher educated and higher-ranking personnel. Comparisons showed that lower ranking and lower educated personnel were less likely to have completed the questionnaire once started. Majority of dropouts occurred during the mental health questions. Possibly these questions were hard to answer, or there were anonymity concerns. Additionally, drop-out might have been higher due to the use of forced response. The current study used a complete case analysis, which carries the assumption that data are missing completely at random.43 As the data appeared not to be missing completely at random, as described before, the results should be interpreted with caution, as they might be different for lower ranking and lower educated personnel. Previous research has shown that younger and lower educated workers disclosed less,18 so disclosure rates in the current study might be an overestimation of the true rates. Future research should further examine this in a representative sample.

Third, it should be noted that MHI in the current study includes substance use disorders. Previous research suggests that the stigma concerning substance use disorder is higher compared with general mental health stigma,44 but no comparisons could be made in the current study. Therefore, it is important that future research examines the decision to disclose a substance use disorder separately from other MHI.

Also, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, no causality can be presumed.

Additionaly, it should be noted that the questionnaire assessing attitudes, beliefs and needs regarding disclosure, has not been validated. It was developed specifically for the current study.

Conclusion

To better facilitate (early-)disclosure of MHI to a supervisor, there is a need for several changes within the military. First, destigmatising interventions and policies are needed to create a culture change where personnel do not feel shame for having MHI, and do not have to fear that stigma and discrimination negatively affect their careers and well-being at work. Second, offered early interventions should align with the preference for self-management. Third, our results strongly suggest a need to train supervisors to recognise, and effectively communicate with, personnel with MHI and to improve employee–supervisor relationships. Together this could facilitate (early-)disclosure which may optimise opportunities for the provision of workplace support and accommodations, which in turn can increase the chance of recovery and sustainable employment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the people who participated in this study and shared their personal experiences with us, giving us insight into this important topic. We also thank the providers of the funding for this research, the IMPACT PhD Program 2018 of Tilburg University and a grant from the Dutch Ministry of Defence. Finally, we thank the military research department, and especially Jolanda Snijders, who helped with participant recruitment.

Footnotes

Twitter: @EvelienBrouwers

Contributors: As the PhD student on the project, RB was involved in all aspects of the study.

RB is also the guarantor for this study. EG was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study. Also, he provided multiple rounds of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. NG was involved by advising RB during designing the study and provided one critical round of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. FL was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study and provided one critical round of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. JvW was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study. Also, he provided multiple rounds of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. DvdM was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study and provided one critical round of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. ADR was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study and provided one critical round of feedback on the manuscript of the paper. EB, project leader, who wrote the research proposal, was involved by advising RB during the formulating of research question(s) and designing the study. Provided multiple rounds of critical feedback on the manuscript of the paper.

Funding: This work was mainly supported by the IMPACT PhD Program 2018 of Tilburg University (no grant number). Additionally, the work was partially supported by a grant from the Dutch Ministry of Defence (no grant number), but this grant did not influence the interpretation of the data; the writing of the paper; or the decision to submit the paper for publication. These funding sources were not involved in study design; analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: RB reports grants from The Dutch Ministry of Defence, during the conduct of the study. However, this did not influence the interpretation of the data or the decision to submit the paper for publication. EG has nothing to disclose. NG is the Royal College of Psychiatrists Lead for Trauma and the Military; however, all views expressed are his own. FL is an employee at the Ministry of Defence but this did not influence the interpretation of the data or the decision to submit the paper for publication. JvW has nothing to disclose. DvdM has nothing to disclose. ADR has nothing to disclose. EB reports grants from The Dutch Ministry of Defence, during the conduct of the study. However, this did not influence the interpretation of the data or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author RB.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences Ethics Review Boards (approval number RP324) and the Dutch Military Ethics Review Board.

References

- 1.Brouwers EPM. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol 2020;8:36. 10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AM. Disclosure of mental illness in the workplace: a literature review. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2011;14:212–29. 10.1080/15487768.2011.598101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:11. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Beukering IE, Smits SJC, Janssens KME, et al. In what ways does health related stigma affect sustainable employment and well-being at work? A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2022;32:365–79. 10.1007/s10926-021-09998-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwers EPM, Joosen MCW, van Zelst C, et al. To disclose or not to disclose: a multi-stakeholder focus group study on mental health issues in the work environment. J Occup Rehabil 2020;30:84–92. 10.1007/s10926-019-09848-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogaers R, Geuze E, van Weeghel J, et al. Decision (not) to disclose mental health conditions or substance abuse in the work environment: a multiperspective focus group study within the military. BMJ Open 2021;11:e049370. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gignac MAM, Jetha A, Ginis KAM, et al. Does it matter what your reasons are when deciding to disclose (or not disclose) a disability at work? The association of workers’ approach and avoidance goals with perceived positive and negative workplace outcomes. J Occup Rehabil 2021;31:638–51. 10.1007/s10926-020-09956-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stergiou-Kita M, Mansfield E, Bezo R, et al. Danger zone: men, masculinity and occupational health and safety in high risk occupations. Saf Sci 2015;80:213–20. 10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Wal SJ, Gorter R, Reijnen A, et al. Cohort profile: the prospective research in stress-related military operations (PRISMO) study in the Dutch armed forces. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026670. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogaers R, Geuze E, van Weeghel J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for treatment-seeking for mental health conditions and substance misuse: multi-perspective focus group study within the military. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e146. 10.1192/bjo.2020.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rüsch N, Rose C, Holzhausen F, et al. Attitudes towards disclosing a mental illness among German soldiers and their comrades. Psychiatry Res 2017;258:200–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogaers R, Geuze E, Greenberg N, et al. Seeking treatment for mental illness and substance abuse: a cross-sectional study on attitudes, beliefs, and needs of military personnel with and without mental illness. J Psychiatr Res 2022;147:221–31. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hastuti R, Timming AR. An inter-disciplinary review of the literature on mental illness disclosure in the workplace: implications for human resource management. Int J Hum Resour Manag 2021;32:3302–38. 10.1080/09585192.2021.1875494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toth KE, Yvon F, Villotti P, et al. Disclosure dilemmas: how people with a mental health condition perceive and manage disclosure at work. Disabil Rehabil 2022;44:7791–801. 10.1080/09638288.2021.1998667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stratton E, Einboden R, Ryan R, et al. Deciding to disclose a mental health condition in male dominated workplaces; a focus-group study. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:684. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toth KE, Dewa CS. Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. J Occup Rehabil 2014;24:732–46. 10.1007/s10926-014-9504-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dewa CS, Weeghel JV, Joosen MC, et al. What could influence workers’ decisions to disclose a mental illness at work? Int J Occup Environ Med 2020;11:119–27. 10.34172/ijoem.2020.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewa CS, van Weeghel J, Joosen MCW, et al. Workers’ decisions to disclose a mental health issue to managers and the consequences. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:631032. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.631032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:1–14. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:867–72. 10.2471/blt.07.045120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: beck depression inventory‐II (BDI‐II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) geriatric depression scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and patient health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63 Suppl 11:S454–66. 10.1002/acr.20556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali R, Meena S, Eastwood B, et al. Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST-lite). Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:352–61. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31:1208–17. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD, 2013: 10. Available: www.ptsd.va.gov [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssens KME, van Weeghel J, Dewa C, et al. Line managers’ hiring intentions regarding people with mental health problems: a cross-sectional study on workplace stigma. Occup Environ Med 2021;78:593–9. 10.1136/oemed-2020-106955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, et al. Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1999;25:447–56. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Comparing stigmatising attitudes towards people with substance use disorders between the general public, GPs, mental health and addiction specialists and clients. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2015;61:539–49. 10.1177/0020764014562051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright KM, Cabrera OA, Bliese PD, et al. Stigma and barriers to care in soldiers postcombat. Psychological Services 2009;6:108–16. 10.1037/a0012620 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorgievski M, Peeters P, Rietzschel E, et al. Betrouwbaarheid en Validiteit van de Nederlandse vertaling van de Work Design Questionnaire. Gedrag & Organisatie 2016;29:273–301. 10.5117/2016.029.003.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim PY, Thomas JL, Wilk JE, et al. Stigma, barriers to care, and use of mental health services among active duty and national guard soldiers after combat. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:582–8. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coleman SJ, Stevelink SAM, Hatch SL, et al. Stigma-related barriers and facilitators to help seeking for mental health issues in the armed forces: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Psychol Med 2017;47:1880–92. 10.1017/S0033291717000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Hees SG, Carlier BE, Vossen E, et al. Towards a better understanding of work participation among employees with common mental health problems: a systematic realist review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2022;48:173–89. 10.5271/sjweh.4005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Beukering IE, Bakker M, Corrigan PW, et al. Expectations of mental illness disclosure outcomes in the work context: a cross-sectional study among Dutch workers. J Occup Rehabil 2022;32:652–63. 10.1007/s10926-022-10026-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuart H. Mental illness stigma expressed by police to police. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2017;54:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould M, Greenberg N, Hetherton J. Stigma and the military: evaluation of a PTSD psychoeducational program. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:505–15. 10.1002/jts.20233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Floyd CB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of effects of wellness recovery action planning on depression, anxiety, and recovery. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:541–7. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, et al. Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:350–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rüsch N, Kösters M. Honest, open, proud to support disclosure decisions and to decrease stigma’s impact among people with mental illness: conceptual review and meta-analysis of program efficacy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021;56:1513–26. 10.1007/s00127-021-02076-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scior K, Rüsch N, White C, et al. Supporting mental health disclosure decisions: the honest, open, PROUD programme. Br J Psychiatry 2020;216:243–5. 10.1192/bjp.2019.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stratton E, Choi I, Calvo R, et al. Web-based decision aid tool for disclosure of a mental health condition in the workplace: a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2019;76:595–602. 10.1136/oemed-2019-105726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertilsson M, Klinkhammer S, Staland-Nyman C, et al. How managers find out about common mental disorders among their employees. J Occup Environ Med 2021;63:975–84. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gayed A, Milligan-Saville JS, Nicholas J, et al. Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:462–70. 10.1136/oemed-2017-104789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thabane L, Mbuagbaw L, Zhang S, et al. A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: the what, why, when and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–12. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, et al. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017;30:378–88. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063125supp001.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-063125supp002.pdf (111.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author RB.