Abstract

Background

Although there are simple and low-cost measures to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), they remain a major public health problem. Quality issues and a lack of knowledge about HAI control among healthcare professionals may contribute to this scenario. In this study, our aim is to present the implementation of a project to prevent HAIs in intensive care units (ICUs) using the quality improvement (QI) collaborative model Breakthrough Series (BTS).

Methods

A QI report was conducted to assess the results of a national project in Brazil between January 2018 and February 2020. A 1-year preintervention analysis was conducted to determine the incidence density baseline of the 3 main HAIs: central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), ventilation-associated pneumonia (VAP), and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTIs). The BTS methodology was applied during the intervention period to coach and empower healthcare professionals providing evidence-based, structured, systematic, and auditable methodologies and QI tools to improve patients’ care outcomes.

Results

A total of 116 ICUs were included in this study. The 3 HAIs showed a significant decrease of 43.5%, 52.1%, and 65.8% for CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, respectively. A total of 5140 infections were prevented. Adherence to bundles inversely correlated with the HAI incidence densities: CLABSI insertion and maintenance bundle (R = −0.50, P = .010 and R = −0.85, P < .001, respectively), VAP prevention bundle (R = −0.69, P < .001), and CA-UTI insertion and maintenance bundle (R = −0.82, P < .001 and R = −0.54, P = .004, respectively).

Conclusions

Descriptive data from the evaluation of this project show that the BTS methodology is a feasible and promising approach to preventing HAIs in critical care settings.

Keywords: central line-associated bloodstream infection, healthcare-associated infection, quality improvement, urinary tract infection, ventilator-associated pneumonia

Providing mentorship to healthcare professionals and the use of structured, systematic, and auditable methodologies to strengthen safety processes and increase adherence to evidence-based practices improves patients’ care outcomes in a large-scale, collaborative manner in a middle-income country.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) represent one of the most common unintentional adverse events related to patient care [1–3]. Nowadays, HAIs are considered a major public health problem because of their high impact on the morbimortality and quality of life of patients, as well as the economic impact on health services [4–8].

Considering the existence of simple, low-cost prevention and control measures that are disseminated globally, HAIs can currently be recognized as possible failures in healthcare [6]. Deficiencies in quality and a lack of knowledge about HAI control among healthcare professionals may contribute to this scenario [4–6].

In light of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized HAIs as a global challenge in need of action and preventive measures as a priority [6]. To achieve these goals, collaborative efforts to improve patient care outcomes, enhance healthcare system performance, and develop work teams to establish a patient safety culture are required. Currently, a well known and widely used approach is the Breakthrough Series (BTS) [9]. This quality improvement (QI) model consists of a short-term collaborative approach that facilitates the learning of participating institutions through contact with teams and professionals experienced in a selected subject, using structured, systematic, and auditable methodologies in search for improvements in patients care, closing the gaps between the finest scientific evidence available, and daily practice [9].

Regarding the success of this approach in healthcare programs [10–13], in 2017, the Brazilian Ministry of Health promoted, in line with the National HAI Prevention and Control Program, and the National Patient Safety Policy, the collaborative initiative “Large scale patient safety improvement,” simplified as “Saúde em Nossas Mãos” (SNM) from the Portuguese “Health in our hands,” which aimed to reduce HAIs in intensive care units (ICUs). This article aims to present the implementation and results of this project in Brazil using the BTS model.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a QI report with a retrospective analysis assessing the collaborative project Large scale patient safety improvement in Brazil during its implementation from January 2018 to February 2020. The project involved a preintervention analysis between January and December 2017 to determine the monthly incidence density baseline of HAIs from the participating ICUs. During the intervention period, monthly indicators were systematically collected to create the database used for this academic article.

Participants

The Brazilian Ministry of Health promoted this project through a support Program for the Institutional Development of the Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS). An open call was made at the national level for all public institutions with adult ICUs throughout Brazil. The application was voluntary and no financial incentive was provided to the participating organizations.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: public or not-for-profit organization hospitals with more than 100 beds, including at least 10 ICU beds, and high-complexity reference centers in their region. The exclusion criteria were as follows: absence of a formalized quality department, absence of an infection control committee, and/or failure of the organization's director or leader to agree to participate. According to these criteria, the hospitals were ranked, and the first 120 institutions (numbers predefined by the project) were selected. For PROADI-SUS purposes, to improve and support the Brazilian public health system, private institutions were not included.

Intervention

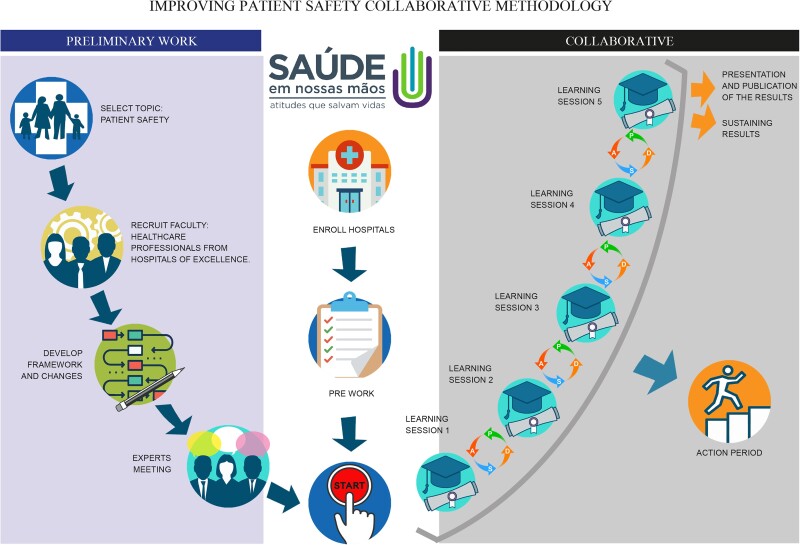

The SNM Collaborative followed the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)'s BTS methodology from January 2018 to February 2020, with adaptations to local settings (Figure 1). The overarching aim was to provide equitable access to integrated, evidence-based care to help the participating ICUs in patient care to prevent HAIs. The Ministry of Health and 5 private institutions of recognized excellence belonging to the PROADI-SUS, together with the IHI support team, developed the intervention framework and conducted preliminary work: they recruited the QI teams to provide intervention leadership, coordination, and in-practice coaching. The theory of change was adopted based on the driver diagram from the QI model (Figure 2). Before launching, expert working group meetings were held to help shape the contents, refine technical issues, and prepare the QI teams to start the implementation. Each institution of the PROADI-SUS, called a hub, acted as a leader, coordinator, and QI mentor for the participating ICUs.

Figure 1.

Adaptation of the Breakthrough Series model to the collaborative initiative “Large scale patient safety improvement” in Brazil. A, Act; D, Do; P, Plan; S, Study.

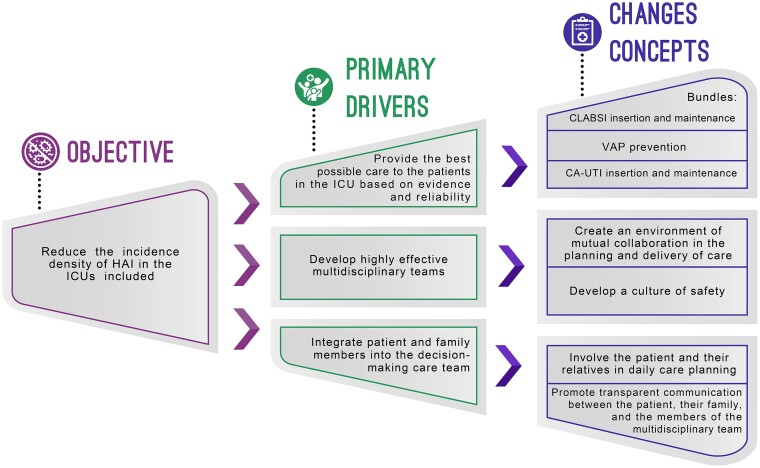

Figure 2.

Summary of the main topics covered by the driver diagram of the Breakthrough Series model used in the collaborative initiative “Large scale patient safety improvement” in Brazil. CA-UTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infections; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infections; HAI, healthcare-associated infections; ICU, intensive care unit; VAP, ventilation-associated pneumonia.

The 5 QI teams were compounded by interdisciplinary members representing key disciplines as follows: infectious diseases and intensive care physicians, nursing, respiratory therapists, technical nursing, and at least 1 member certified by the IHI in improvement science. Each QI team developed its own site-specific aim aligned with the overall collaborative aims based on its population of focus, and small adaptations were accepted to support interdisciplinary participation and allow for customization.

The Breakthrough Series Model

The intervention included 6 onsite training sessions held every 3 to 4 months. Between the sessions (action period), monthly online remote support sessions and onsite educational technical visits were held, where the process to prevent HAI, QI tools, and teamwork techniques were tracked. Moreover, during these periods, teams were coached to work with other healthcare workers engaged in intensive care at their sites to test and implement changes using plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles (Figure 1).

In all of these meetings, the ICU teams received the following basic training on QI methods: (1) how to design initial tests of change to reduce HAI rates, and (2) how to share successful experiences and challenges in implementing the changes. Simulation training on preventing HAI was also conducted. Each ICU team received at least 1 coach call monthly, aside from the collective call, to support them in the activities in improving healthcare and multiply the acquired knowledge inside their hospitals during the virtual and in-person sessions. For further doubts and queries, the SNM Collaborative also created an online platform (https://saudeemnossasmaos.proadi-sus.org.br/biblioteca-virtual) to support ICUs professionals during the implementation period and for uploading and disseminating all knowledge files, technical documents, guidelines, and recorded meetings.

Outcomes

The proposed goal of the SNM project was a 50% reduction in the baseline incidence densities of HAI in intensive care settings, focusing on the infections with the greatest impact on morbidity, mortality, and hospital costs: central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) confirmed through laboratory tests, ventilation-associated pneumonia (VAP), and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTIs). The diagnosis criteria were defined using the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) definitions [14] following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations [15–17]. A driver diagram was developed for each of the HAIs studied, including bundle specifications and hand hygiene protocols using the finest evidence available (Supplementary Table 1 shows the driver diagram for hand hygiene as an example).

Before implementing changes, ICU teams were supported to standardize their clinical data entry using an electronic record form template. This form allowed the standardization of clinical care and QI indicators. Teams reported monthly aggregated, nonnominal quality metrics and a qualitative description of change.

Variables

Two important QI indicators were assessed in this study: (1) adherence to the prevention bundles of each analyzed HAI and (2) adherence to hand hygiene. Both indicators were calculated using the following formula:

These indicators were not systematically measured before the SNM implementation, thereby it was not possible to perform a historical analysis. These variables were compared with the density of the incidence rates of each HAI with the respective bundle and each of their subitems.

Statistics

A Shewhart chart was used to analyze the CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI incidence densities over the intervention period. Data from the CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI were modeled using a time series. The model used for the adjustment was regression with autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) errors using a transfer function model. A “project” variable was created with values (1) equal to zero for the baseline months (preproject) and (2) equal to 1 for the intervention months. The model was adequate for all of the 3 indicators, and the adjusted model residuals showed no correlation. The percentage of adherence to bundles and hand hygiene was correlated with HAI incidence densities during the study period, and Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated. The significance level was set to ∂ = 5%. Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab v18 (State College, PA, USA) and JMP v16 (Cary, NC, USA).

Patient Consent Statement

The SNM project was promoted and implemented by the Brazilian Ministry of Health in accordance with national ethical recommendations. For this academic article, the access to the SNM database was approved by the local human research ethics committees (Certificado de Apresentação de Apreciação Ética - CAAE 39657220.8.0000.5330) of the 5 PROADI-SUS institutions, with the consent of the SNM coordinator and the authorization of the ministry responsible. The available database presented indicators of QI processes and did not exhibit any data referring to or mentioning the participating institutions or patients involved. Hence, this study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

RESULTS

A total of 226 institutions spread across all the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District applied to this project (Supplementary Figure 1A). A total of 120 ICUs were selected to participate in this initiative, and only 4 withdrawals were reported until February 2020 (Supplementary Figure 1B). Further features of the participant ICUs are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The included ICUs were randomly assigned in equal numbers to 1 of the 5 hubs.

Throughout the project, the hubs used continuous strategies to generate engagement and empowerment in the ICU teams. These ICU teams were also combined with the following interdisciplinary members: intensive care physician, nursing, respiratory therapists, technical nursing, and at least 1 member of infection control committee. These activities were performed equally in all the participating ICUs and included the following: (1) in-person learning sessions (28 lectures, 23 workshops, and 226 storyboards) coordinated by representatives of the Ministry of Health and staff from the 5 hubs (90 and 72, respectively), both nationally and regionally, with the participation of 3381 and 1670 health workers, respectively; (2) virtual learning sessions (28 meetings) with the attendance of 12 960 professionals; and (3) reunions (600 visits including leadership huddles, technical encounters, and gatherings to commemorate good results), where more than 1.6 million kilometers were traveled and 160 000 hours dedicated.

Every month, the ICU teams posted their data on outcome, process, and balance measures into a database of the project, and they submitted a monthly report to their hub for analysis, discussion, and feedback. All of the participating ICUs reported their data. The data were aggregated and analyzed by the governance team to assess the progress of the project.

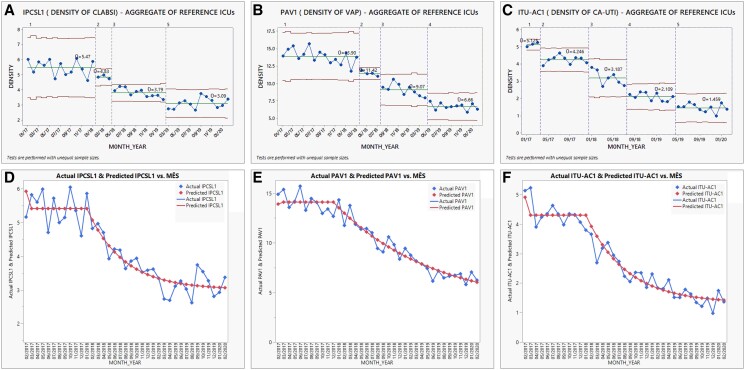

Reducing Healthcare-Associated Infections

Healthcare-associated infection incidence density baseline of the enrolled ICUs was 5.47, 13.90, and 4.24 per 1000 device-days for CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, respectively. During the study period, CLABSI reached a 43.5% reduction, decreasing to 3.09 (Figure 3A); VAP reached a 52.1% reduction, declining to 6.66 (Figure 3B); and CA-UTI attained a 65.8% decrement, declining to 1.45 cases per 1000 device-days (Figure 3C). Time-series modeling demonstrated a significant impact on decreasing incidence densities baselines after the implementation of the SNM project for CLABSI (R2 = 0.89, P < .001), VAP (R2 = 0.94, P < .001), and CA-UTI (R2 = 0.92, P < .001) (Figure 3D–F).

Figure 3.

Shewhart charts between January 2018 and February 2020 and time-series modeling. (A) Incidence density of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) per 1000 catheter-d. (B) Incidence density of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) per 1000 ventilator-d. (C) Incidence density of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTI) per 1000 catheter-d. (D) Incidence density of CLABSI time-series model. (E) Incidence density of VAP time-series model. (F) Incidence density of CA-UTI time-series model. Blue dots, monthly incidence density; green line, center line; red line, upper and lower control limits. ICU, intensive care unit; IPCSL1, incidence density of central line-associated bloodstream infections; ITU-AC1, incidence density of catheter-associated urinary tract infections; PAV1, incidence density of ventilation-associated pneumonia;

Overall, based on the intervention impact in the historical baselines, we estimated that 5140 infections might have been prevented. Furthermore, 60.5%, 71.0%, and 23.7% of the ICUs reached over 1000 device-days without infections at some time during the projects for CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, respectively.

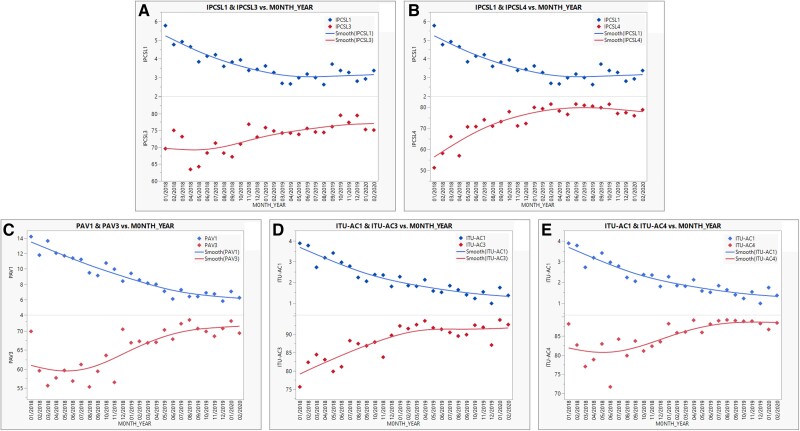

Adherence to Device Bundles and Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention

Figure 4A and B show the adhesion to the insertion and maintenance bundles gradually increasing, followed by a progressive reduction in the incidence density of CLABSI, evidencing a significant negative correlation for both (R = −0.50, P = .010 and R = −0.85, P < .001, respectively). Figure 4C shows a negative correlation between the prevention bundle of VAP and the decrease in its incidence density (R = −0.69, P < .001). Finally, Figure 4D and E present the interaction of the insertion and maintenance bundle fidelity and the incidence density of CA-UTI, also revealing a contrary correlation between them (R = −0.82, P < .001 and R = −0.54, P = .004, respectively). The adherence to each item of each bundle for CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI are presented in Table 1–3, respectively.

Figure 4.

Correlation between adhesion to the insertion/maintenance bundles and the incidence densities of the studied healthcare-associated infections. (A) Correlation between adhesion to the insertion bundle and incidence density of central line-associated bloodstream infections per 1000 catheter-d. (B) Correlation between adhesion to the maintenance bundle and incidence density of central line-associated bloodstream infections per 1000 catheter-d. (C) Correlation between adhesion to the prevention bundle and incidence density of ventilator-associated pneumonia per 1000 ventilator-d. (D) Correlation between adhesion to the insertion bundle and incidence density of catheter-associated urinary tract infections per 1000 catheter-d. (E) Correlation between adhesion to the maintenance bundle and incidence density of catheter-associated urinary tract infections per 1000 catheter-d. IPCSL1, incidence density of central line-associated bloodstream infections; IPCSL3, adherence to the insertion bundle central line-associated bloodstream infections; IPCSL4, adherence to the maintenance bundle central line-associated bloodstream infections; ITU-AC1, incidence density of catheter-associated urinary tract infections; ITU-AC3, adherence to the insertion bundle catheter-associated urinary tract infections; ITU-AC4, adherence to the maintenance bundle catheter-associated urinary tract infections; PAV1, incidence density of ventilation-associated pneumonia; PAV3, adherence to the prevention bundle ventilation-associated pneumonia.

Table 1.

Correlation Between the Incidence Density of Central-line Associated Bloodstream Infections Confirmed Through Laboratory Tests and the Adhesion to Each Bundle Item

| Bundle | Incidence Density | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence (%) | CLABSI Per 1000 Catheter-days | |

| Insertion Bundle Items | Ra | P Value |

| Evaluate the indication for CVC insertion | −0.89 | <.001 |

| Use maximum barrier precaution | −0.07 | .740 |

| Perform skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine | −0.58 | .002 |

| Optimally select the insertion site | −0.51 | .008 |

| Dressing properly after insertion | 0.31 | .122 |

| All or nothing | −0.50 | .010 |

| Maintenance bundle items | Ra | P Value |

| Register the indication of CVC permanence | −0.53 | .005 |

| Adhere to aseptic technique in catheter handling | −0.74 | <.001 |

| Carry out maintenance of the infusion system | −0.12 | .578 |

| Adhere to correct dressing technique | 0.25 | .217 |

| All or nothing | −0.85 | <.001 |

Bold text: All or nothing results.

Abbreviations: CVC, central venous catheter; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infections.

Pearson test.

Table 2.

Correlation Between the Incidence Density of Ventilation-associated Pneumonia and the Adhesion to Each Bundle Item

| Bundle | Incidence Density | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence (%) | VAP Per 1000 Ventilator-day | |

| Prevention Bundle Items | Ra | P Value |

| Perform routine oral hygiene | −0.59 | .002 |

| Keep the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees | −0.64 | <.001 |

| Perform sedation reduction | −0.88 | <.001 |

| Daily check for the possibility of extubation | −0.80 | <.001 |

| Maintain cannula cuff pressure between 25–30 cmH2O (or 20–22 mmHg) | −0.56 | .003 |

| Maintenance of the mechanical ventilation systemb | −0.66 | <.001 |

| All or nothing | −0.69 | <.001 |

Bold text: All or nothing results.

Abbreviation: VAP, ventilation-associated pneumonia.

Pearson test.

According to the recommendations in force in the country.

Table 3.

Correlation Between the Incidence Density of Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections and the Adhesion to Each Bundle Item

| Bundle | Incidence Density | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence (%) | CA-UTI Per 1,000 Catheter-day | |

| Insertion Bundle Items | Ra | P Value |

| Indicate the use of bladder catheter only when appropriate | −0.59 | <.001 |

| Comply with aseptic technique when inserting a bladder catheter | −0.55 | .004 |

| All or nothing | −0.82 | <.001 |

| Maintenance bundle items | Ra | P Value |

| Keep the drainage system closed | −0.54 | .004 |

| Execution of the correct technique when handling the drainage system | −0.52 | .006 |

| Perform daily hygiene of the urethral meatus | −0.78 | <.001 |

| Daily verification of the need to maintain the urinary catheter | −0.45 | .022 |

| All or nothing | −0.54 | .004 |

Bold text: All or nothing results.

Abbreviation: CA-UTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

Pearson test.

Adherence to Hand Hygiene and Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention

A negative correlation was observed between adherence to hand hygiene and the incidence densities of CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI (R = −0.200, R = 0.368, and R = −0.310, respectively); however, no significant associations were found in this sample (P > .05 for all) (Supplementary Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Participating ICU teams have made significant progress in implementing evidence-based changes to clinical workflow and patient care processes, with a focus on HAI prevention. As a result, a significant impact on HAI reduction was observed, with a decrease of over 43% and up to 65% in the 3 most critical HAIs during a short intervention period. These findings reinforce the relevance of healthcare professionals’ training and empowerment, and the use of structured, systematic, and auditable methodologies to improve outcomes in patients’ care, creating an appropriate safety patient culture, especially in intensive care settings.

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the largest QI collaboratives worldwide, one of the first in Latin America, and one of the first made in Brazil using the BTS model to prevent HAIs [10, 11, 18, 19]. However, this is the first attempt including over 100 ICUs, reducing, simultaneously, the 3 most crucial HAIs, leading to a striking impact on the public health system in terms of prevention, relevant clinical indicators, care quality, safety, and economical savings, especially in a middle-income country such as Brazil. Moreover, recognizing the vast divergences among the participant ICUs, including different regions across Brazilian territory, patients’ profiles (general, surgical, neurological, and others), structural and human resources distinctiveness, financial gaps, and the features of each service, this project emphasizes how a well structured QI approach can achieve outstanding and similar results among all units regardless of divergences. This is far-reaching in the context of low- and middle-income countries seeking low-cost and highly effective public health strategies to reduce HAIs.

The WHO efforts aimed at preventing HAIs have continued to grow globally [6, 20], and apparently, they have begun producing adequate results in recent years, showing favorable changes in HAI incidences [21–25]. National reports have also revealed positive results, with a decrease from 4.4 to 3.9, 12.2 to 10.7, and 4.7 to 3.6 in the incidence of CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, respectively, between 2017 and 2019 [26]. The results evidently represent that CA-UTI shows greater potential for reduction. Indeed, our initiative achieved a 65.8% reduction of CA-UTI, almost thrice more than the number published in the Brazilian national report, including 1525 to 1637 ICUs in 2017–2019 [26]. Daily review of the catheter indication, as noticed in the participant ICUs during this project, contributed to less utilization and consequently fewer infections [27]. In addition to the technical aspects of CA-UTI prevention, there has been a focus on the role that changes in behavior and culture play in QI [27, 28]. As proposed in the BTS methodology, efforts involving both technical and QI interventions are necessary to bridge the gap between evidence and end users in CA-UTI prevention.

Furthermore, the main challenge was CLABSI incidence density reduction [29], probably because central venous catheters are difficult to handle and involve many steps in insertion and maintenance care [30]. Most participating ICUs did not have standardized alcohol swabs, transparent dressings, or closed infusion systems for 100% compliant handling. Despite this, a considerable decline of 43% in CLABSI was achieved, demonstrating better performance than the national curve (11% reduction in the 3-year period) [26]. Although a direct causal link between these interventions and a reduction in CLABSI cannot be established based on this project, improved staff knowledge and behaviors may have contributed to improving bundle compliance and, further, led to fewer CLABSIs [31–34].

Despite strategies to prevent VAP, its prevalence remains stable [20, 35]. Several factors contribute to this scenario, including a lack of resources, noncompliance with infection control procedures, and insufficient knowledge of VAP among health professionals. In fact, VAP occurrence was inversely associated with adherence to prevention bundles [36–39]. Thus, QI approaches focusing on adherence, allowing reflections, review, and adequacy (PDSA) by the ICUs professionals, implemented in a cyclical fashion in our project, was critical for success in VAP reduction [40]. Our findings firmly established the negative correlation between bundles compliance and VAP reduction, and once again they exposed a considerable decrease of more than 52% from the baseline—thrice more than that published in the Brazilian national report, including 1521 to 1644 ICUs in 2017–2019 [26].

Altogether, we also reinforce the importance of the use of auditable methodologies [6], evidencing how adhesion to the prevention bundles is highly and significantly negatively correlated with HAI incidence densities (R < −0.5 for all), with every single item essential for infection control. It is remarkable that we did not find a significant correlation between the dressing technique subitems in the insertion and maintenance of CLABSI bundles. This finding can be related, as mentioned above, to resource and supply issues and is not necessarily associated with a lack of adhesion. Proper dressing to cover the catheter site and subsequent monitoring and replacement are imperative for CLABSI control, and we still highly recommend it [41].

The SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands initiative is part of a major global effort led by the WHO: it includes “My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene”. Hand hygiene is the single most important measure to reduce the transmission of microorganisms, but health worker compliance regarding this is still a challenge [42, 43]. In fact, it is evident how the adherence curve is increasing, albeit slowly, through the intervention period, which might have revealed difficulties in reaching this goal, and it could have explained why no significant correlation was found with the HAI incidence densities in our sample. Once again, supply readiness, underreported data, or a low number of ICUs with implemented protocols may also have contributed to this result because many hospitals had no alcoholic product at the bedside or a multimodal strategy before the project [44]. We emphasized hand hygiene as one of the most cost-effective tools in fighting HAI; however, the WHO efforts do seem to be enough for HAI control, mainly in developing countries [45]. Indeed, there is a demand to update the WHO recommendations [46]. As proposed here, the success of our intervention is not only based on technical issues, but it is also focused on multimodal QI strategies adapted to local and cultural contexts [47]. Our findings reinforce that hand hygiene alone, despite being mandatory, is not enough for HAI control, and futures strategies, both nationally and internationally, should include a wider overview of the problem [42, 43, 46–50].

The 100 000 Lives Campaign was a nationwide initiative launched by the IHI to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality in American healthcare [51]. To follow the goal of this crusade, we used previous mortality rates reported for HAI [52–54] and local data of the participating ICUs (unpublished data), estimating a mortality rate for each: 0.31 for CLABSI, 0.51 for VAP, and 0.1 for CA-UTI. Therefore, we calculated the potential of 1836 lives saved during the present initiative until February 2020: 398, 1309, and 129 for CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, respectively.

Limitations

Despite the outstanding results presented in this study, because the SNM Collaborative was initially not proposed and implemented as a research project, it is not exempt from academic limitations. First, considering the retrospective analysis, some variables were not included in this report due to missing values or insufficient data. For example, a valuable QI indicator such as knowledge acquisition by the ICU teams was collected before and after some learning sessions, but final data were not robust enough for a proper analysis.

Second, although the call to participate was open to all institutions, the selected ICUs may not be representative of the real healthcare situation in Brazil. Likewise, stakeholders may either represent ICUs with notorious deficiencies claiming for the application of QI strategies or services with a culture of QI mindset. For this reason, exclusion of institutions with a lack of patient care quality service and/or infection control committee, which can suggest lower quality ICUs, might have contributed to a selection bias; nevertheless, the inclusion criteria were appropriate in terms of applicability and sustainability according to the intervention proposal.

Third, this project proposed a pre- and postintervention analysis. In academic terms, it would be desirable to have a control group to assess the impact of the implementation compared to usual care. In light of this, we compared the project's results to the national HAI report using the published density in several ICUs reported at the national level during the same analyzed period, serving as the bottom line of our temporal analysis. Another strategy would have been to include the ICUs that applied to the SNM but were not selected; however, because it was not initially proposed and due to resources limitations, it was not possible to follow-up these institutions.

Fourth, although the HAI mortality rate can be used as an estimate for projecting deaths from CLABSI, VAP, and CA-UTI, there is a risk of death that is inherent to ICU patients (baseline risk) based on multiple factors [7, 8]. Therefore, it is necessary to estimate the increase in the probability of death of an ICU patient with HAI versus without HAI using the local settings. Further studies are necessary to enhance the accuracy of estimating saved lives.

Fifth, as previously mentioned, the wide divergence among the participant ICUs, in addition to the hospital features and health service specificities where they belong, did not allow for further subgroup analysis. Specific yields would have been desirable to better understand the ICUs’ performance.

Finally, we did not collect demographic and severity scores of the patients cared for by the participants, and we cannot exclude that it might have changed throughout the intervention, although it is very unlikely because they are public, highly demanded tertiary hospitals with high acuity and they did not receive any financial performance-based benefit.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirms that the BTS methodology is a feasible and promising approach for QI in healthcare organizations in low- and middle-income countries, demonstrating that the implementation of evidence-based preventive bundles and improvement science are high-potential strategies to achieve remarkable outcomes related to patients’ safety and HAI control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the healthcare professionals working in the intervened intensive care units: without their empowerment and motivation, this project would not have been successful. We also appreciate the technical and administrative teams of Program for the Institutional Development of the Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS), which supported the development of this project. The Collaborative Study Group team members are listed in the Supplementary Files.

Disclaimer. None of the institutions were involved in the design and writing of this publication or in the analysis or interpretation of the indicators obtained from the database.

Financial support. This work was supported by public resources from the Ministry of Health through PROADI-SUS and with philanthropic resources from the participating institutions: Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz, Hospital do Coração, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Hospital Moinhos de Vento , and Hospital Sírio-Libanês .

Contributor Information

Paula Tuma, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Jose M Vieira Junior, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, São Paulo, Brazil.

Elenara Ribas, Hospital Moinhos de Vento, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Karen C C D Silva, Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz, São Paulo, Brazil.

Andrea K F Gushken, Hospital do Coração, São Paulo, Brazil.

Ethel M S Torelly, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, São Paulo, Brazil.

Rafaela M de Moura, Hospital Moinhos de Vento, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Bruno M Tavares, Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz, São Paulo, Brazil.

Cristiana M Prandini, Hospital do Coração, São Paulo, Brazil.

Paulo Borem, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Pedro Delgado, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Luciana Y Ue, Ministério da Saúde, Brasília, Brazil.

Claudia G de Barros, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

Sebastian Vernal, Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz, São Paulo, Brazil; Hospital do Coração, São Paulo, Brazil; Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil; Hospital Moinhos de Vento, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Hospital Sírio-Libanês, São Paulo, Brazil.

Collaborative Study Group “Saúde em Nossas Mãos”:

Ademir Jose Petenate, Adriana Melo Teixeira, Alex Martins, Alexandra do Rosário Toniolo, Aline Brenner, Aline Cristina Pedroso, Ana Paula Neves Marques de Pinho, Antonio Capone Neto, Beatriz Ramos, Bernadete Weber, Cassiano Teixeira, Cilene Saghabi, Claudia Vallone Silva, Cristiane Tejada da Silva Kawski, Daiana Barbosa da Silva, Daniel Peres, Daniela Duarte da Silva de Jesus, Dejanira Aparecida Regagnin, Eloiza Andrade Almeida Rodrigues, Erica Deji Moura Morosov, Fernanda Justo Descio Bozola, Fernanda Paulino Fernandes, Fernando Enrique Arriel Pereira, Fernando Gatti de Menezes, Flavia Fernanda Franco, Giselle Franco Santos, Guilherme Cesar Silva Dias dos Santos, Guilherme de Paula Pinto Schettino, Helena Barreto dos Santos, Karina de Carvalho Andrade, Leonardo Jose Rolim Ferraz, Louise Viecili Hoffmeister, Luciana Gouvea de Albuquerque Souza, Luciano Hammes, Marcia Maria Oblonczyk, Márcio Luiz Ferreira de Camillis, Maria Yamashita, Marianilza Lopes da Silva, Nidia Cristina de Souza, Pâmella Oliveira de Souza, Patrícia dos Santos Bopsin, Pedro Aurélio Mathiasi Neto, Pryscila Bernardo Kiehl, Regis Goulart Rosa, Renato Tanjoni, Roberta Cordeiro de Camargo Barp, Roberta Gonçalves Marques, Rogerio Kelian, Roselaine Maria Coelho Oliveira, Thais Galoppini Felix, Tuane Machado Chaves, Vania Rodrigues Bezerra, Wania Regina Mollo Baia, and Youri Eliphas de Almeida

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:309–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenthal VD, Duszynska W, Ider BE, et al. . International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 45 countries for 2013–2018, adult and pediatric units, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, et al. . Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011; 377:228–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haque M, Sartelli M, McKimm J, Bakar MA. Health care-associated infections—an overview. Infect Drug Resist 2018; 11:2321–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blot S, Ruppe E, Harbarth S, et al. . Healthcare-associated infections in adult intensive care unit patients: changes in epidemiology, diagnosis, prevention and contributions of new technologies. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2022; 70:103227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenthal VD, Yin R, Valderrama-Beltran SL, et al. . Multinational prospective cohort study of mortality risk factors in 198 ICUs of 12 Latin American countries over 24 years: the effects of healthcare-associated infections. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2022; 12:504–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenthal VD, Yin R, Lu Y, et al. . The impact of healthcare-associated infections on mortality in ICU: a prospective study in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. Am J Infect Control 2022; 6:S0196-6553(22)00658–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement . The breakthrough series: IHI's collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 10. Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, et al. . Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Safe 2018; 27:226–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schreiber PW, Sax H, Wolfensberger A, et al. . The preventable proportion of healthcare-associated infections 2005–2016: systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018; 39:1277–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gustafson DH, Quanbeck AR, Robinson JM, et al. . Which elements of improvement collaborative are most effective? A cluster-randomized trial. Addiction 2013; 108:1145–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke CM, Cheng T, Reims KG, et al. . Implementation of HIV treatment as prevention strategy in 17 Canadian sites: immediate and sustained outcomes from a 35-month quality improvement collaborative. BMJ Quality and Safety 2016; 25:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária . [Critérios diagnósticos de infecções relacionadas à assistência à saúde/agência nacional de vigilância. Sanitária]. Available at: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/centraisdeconteudo/publicacoes/servicosdesaude/publicacoes/caderno-2-criterios-diagnosticos-de-infeccao-relacionada-a-assistencia-a-saude.pdf/. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Pneumonia (ventilator-associated [VAP] and non-ventilator-associated pneumonia [PNEU]) event. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/6pscvapcurrent.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line associated bloodstream infection). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [CAUTI] and non-catheter-associated urinary Tract infection [UTI]) and Other Urinary System infection [USI]) events. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 18. Mauger B, Marbella A, Pines E, et al. . Implementing quality improvement strategies to reduce healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review. Am J Infect Control 2014; 42:S274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lajolo C, Sardenberg C, Rooney K, et al. . Effectiveness of a collaborative approach in reducing healthcare-associated infections and improving safety in Brazilian ICUs: the Salus Vitae story. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 25:998. [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization . Core competencies for infection prevention and control professionals, 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/335821. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 21. Magill SS, O’Leary E, Janelle SJ, et al. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care–Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals. New Engl J Med 2018; 379:1732–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller K, Briody C, Casey D, et al. . Using the comprehensive unit-based safety program model for sustained reduction in hospital infections. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44:969–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Rodrigues C, et al. . Impact of international nosocomial infection control consortium (INICC) strategy on central line-associated bloodstream infection rates in the intensive care units of 15 developing countries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:1264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenthal VD, Rodrigues C, Álvarez-Moreno C, et al. . Effectiveness of a multidimensional approach for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adult intensive care units from 14 developing countries of four continents: findings of the international nosocomial infection control consortium. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:3121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenthal VD, Todi SK, Álvarez-Moreno C, et al. . Impact of a multidimensional infection control strategy on catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates in the adult intensive care units of 15 developing countries: findings of the international nosocomial infection control consortium (INICC). Infection 2012; 40:517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária . [Avaliação dos indicadores nacionais de IRAS e Resistência microbiana]. Available at: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZGI3NzEwMWYtMDI1Yy00ZDE1LWI0YzItY2NiNDdmODZjZDgzIiwidCI6ImI2N2FmMjNmLWMzZjMtNGQzNS04MGM3LWI3MDg1ZjVlZGQ4MSJ9&pageName=ReportSectionac5c0437dbe709793b4b. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 27. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. . A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:2111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baker S, Shiner D, Stupak J, Cohen V, Stoner A. Reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infections: a multidisciplinary approach to driving change. Crit Care Nurs Q 2022; 45:290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Melo LSW, de Abreu MVM, Santos BRO, et al. . Partnership among hospitals to reduce healthcare associated infections: a quasi-experimental study in Brazilian ICUs. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buetti N, Marschall J, Drees M, et al. . Strategies to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43:553–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Melo LSW, Estevão TM, Chaves JSC, et al. . [Fatores de sucesso em colaborativa para redução de infecções relacionadas à assistência à saúde em unidades de terapia intensiva no Nordeste do Brasil]. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2022; 34:327–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Furuya EY, Dick A, Perencevich EN, Pogorzelska M, Goldmann D, Stone PW. Central line bundle implementation in US intensive care units and impact on bloodstream infections. PLoS One 2011; 6:e15452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. . An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Balla KC, Rao SP, Arul C, et al. . Decreasing central line-associated bloodstream infections through quality improvement initiative. Indian Pediatr 2018; 55:753–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Metersky ML, Wang Y, Klompas M, Eckenrode S, Bakullari A, Eldridge N.. Trend in Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Rates Between 2005 and 2013. JAMA 2016; 316:2427–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bouadma L, Deslandes E, Lolom I, et al. . Long-term impact of a multifaceted prevention program on ventilator-associated pneumonia in a medical intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:1115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris AC, Hay AW, Swann DG, et al. . Reducing ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care: impact of implementing a care bundle. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:2218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Su KC, Kou YR, Lin FC, et al. . A simplified prevention bundle with dual hand hygiene audit reduces early-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia in cardiovascular surgery units: an interrupted time-series analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0182252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fortaleza CMCB, Ferreira Filho SP, Silva MO, Queiroz SM, Cavalcante RS.. Sustained reduction of healthcare-associated infections after the introduction of a bundle for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in medical-surgical intensive care units. Braz J Infect Dis 2020; 24:373–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, et al. . Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32:305–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. . Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e162–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luangasanatip N, Hongsuwan M, Limmathurotsakul D, et al. . Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2015; 351:h3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infec 2009; 73:305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Medeiros EA, Grinberg G, Rosenthal VD, et al. . Impact of the international nosocomial infection control consortium (INICC) multidimensional hand hygiene approach in 3 cities in Brazil. Am J Infect Control 2015; 43:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. World Health Organization & United Nations Children's Fund . State of the world's hand hygiene: a global call to action to make hand hygiene a priority in policy and practice. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350184. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 46. Gould D, Purssell E, Jeanes A, Drey N, Chudleigh J, McKnight J.. The problem with ‘my five moments for hand hygiene’. BMJ Qual Saf 2022; 31:322–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sreeramoju P. Reducing infections “together”: a review of socioadaptive approaches. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofy348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allegranzi B, Gayet-Ageron A, Damani N, et al. . Global implementation of WHO's multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:843–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mouajou V, Adams K, DeLisle G, Quach C.. Hand hygiene compliance in the prevention of hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2022; 119:33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sartini M, Patrone C, Spagnolo AM, et al. . The management of healthcare-related infections through lean methodology: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Prev Med Hyg 2022; 63:E464–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Berwick DM, Calkins DR, McCannon CJ, Hackbarth AD. 100,000 Lives Campaign. Campaign materials. Available at: https://www.ihi.org/resources/pages/publications/100000livescampaignsettingagoalandadeadline.aspx. Accessed January 31, 2023.

- 52. Marra AR, Camargo LFA, Pignatari ACC, et al. . Nosocomial bloodstream infections in Brazilian hospitals: analysis of 2,563 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:1866–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:867–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nicolle LE. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014; 25:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.