Abstract

Background:

Although evidence-based smoking cessation guidelines are available, the applicability of these guidelines for the cessation of electronic cigarette and dual e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use is not yet established. In this review, we aimed to identify current evidence or recommendations for cessation interventions for e-cigarette users and dual users tailored to adolescents, youth and adults, and to provide direction for future research.

Methods:

We systematically searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and grey literature for publications that provided evidence or recommendations on vaping cessation for e-cigarette users and complete cessation of cigarette and e-cigarette use for dual users. We excluded publications focused on smoking cessation, harm reduction by e-cigarettes, cannabis vaping, and management of lung injury associated with e-cigarette or vaping use. Data were extracted on general characteristics and recommendations made in the publications, and different critical appraisal tools were used for quality assessment.

Results:

A total of 13 publications on vaping cessation interventions were included. Most articles were youth-focused, and behavioural counselling and nicotine replacement therapy were the most recommended interventions. Whereas 10 publications were appraised as “high quality” evidence, 5 articles adapted evidence from evaluation of smoking cessation. No study was found on complete cessation of cigarettes and e-cigarettes for dual users.

Interpretation:

There is little evidence in support of effective vaping cessation interventions and no evidence for dual use cessation interventions. For an evidence-based cessation guideline, clinical trials should be rigorously designed to evaluate the effectiveness of behavioural interventions and medications for e-cigarette and dual use cessation among different subpopulations.

Over the past decade, vaping or electronic cigarette use has increased dramatically, especially among adolescents and young adults.1,2 E-cigarette or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) were first introduced to the market as a smoking cessation aid.3 However, ENDS have become increasingly popular among young neversmokers, 4–6 mostly because of the availability of e-cigarettes in appealing flavours and the perception of e-cigarettes as less harmful and less addictive than combustible cigarettes.7,8 In 2021, 48% of Canadians aged 20–24 years and 29% of those aged 15–19 years reported having ever used e-cigarettes, whereas only 13% of adults aged 25 years or older reported having done so.9 Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes is also common among both adults and younger people.10–12 Moreover, regular vaping is found to be associated with the subsequent initiation of cigarette smoking.3–5 In 2020, 37% of the current e-cigarette users in Canada reported using combustible cigarettes and e-cigarettes concurrently.13

The long-term health effects of vaping are still not fully known and need to be investigated.3,7 In addition, dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes is associated with greater nicotine dependence,14,15 poorer general health,14 higher levels of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers,16 and higher risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome than use of cigarettes only.15 Although the use of e-cigarettes as a prescription for smoking cessation is promoted in the United Kingdom17 and marketing authorization of vaping products is permitted in the United States,18 several organizations (i.e., American Lung Association, World Health Organization, Smokefree.gov and Truth Initiative) recommend quitting vaping and advise against switching to ENDS from combustible cigarettes.19–22

There is growing evidence that e-cigarette users and dual users are seeking help to quit e-cigarette use, because of health concerns, including increased risk of harm from COVID-19, costs and concerns about the addictive potential of vaping.23–27 Moreover, dual users were found to report similar levels of interest in quitting e-cigarettes as exclusive vapers28 and more attempts to quit smoking than exclusive smokers.29 However, our understanding of the process of vaping cessation and dual use cessation is very limited, and evidence-based guidelines for vaping cessation interventions are yet to be developed.30 Although guidelines on best management for the cessation of combustible cigarettes are available, 31 it is unclear if similar approaches can be extrapolated to nicotine dependence from electronic cigarettes. The objectives of this review were to summarize existing health care evidence or recommendations for cessation of e-cigarette use or complete cessation of dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among adolescents, youth and adult populations, and to identify knowledge gaps for future research.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) for this study32 and registered our protocol (doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/79DXP) in the Open Science Framework.33 We conducted a scoping review, instead of a systematic review, because it allowed us to examine the extent, range and nature of the body of literature on our research topic, and to summarize findings from a range of literature with heterogeneous study designs. It also aided us to thereby identify current gaps in the research and provide directions for future research scope.32,34–36

Search strategy

We initially searched the databases for publications addressing evidence or recommendations on vaping cessation interventions. MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and PsycINFO (Ovid) were searched on May 27, 2021, using various combinations of subject headings, including Medical Subject Headings, when applicable, and keywords (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/2/E336/suppl/DC1). The search results were further limited to English-language papers published from January 2010 to May 2021, as e-cigarettes first emerged in the American market in 2007.30 One reviewer (A.K.) conducted the database search and imported all citations to the Covidence workflow platform, where duplicate papers were removed. The database search strategy was reviewed and improved by incorporating suggestions from all authors. We did not use support from any information specialist because of previous experiences of conducting similar searches by the research team37–40 and budget limitation.

We conducted targeted grey literature searches of key databases, including Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Canadian Medical Association’s Clinical Practice Guidelines Infobase, National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence guidelines, National Guideline Clearinghouse and customized Google searches, between May 28 and May 31, 2021. Customized Google searches included searching for government and organizational reports on vaping cessation interventions or guidelines, of which the first 100 results of each search were considered for title and abstract screening. We also searched the reference lists of identified relevant papers and consulted with subject matter experts.

We decided to modify our search strategy to add publications addressing cessation interventions for dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes. To identify any specific recommendations for dual users, we conducted an additional search on Aug. 3, 2021. This updated strategy is presented in Appendix 1. On Aug. 15, 2022, we also searched for any updated published results of 2 ongoing clinical trials detected in our initial screening.

Eligibility

We included articles that provided evidence or recommendations tailored to adolescents, youth or adults addressing vaping cessation among e-cigarette users and complete cessation of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among dual users. Publications focused on smoking cessation, the harm reduction potential of e-cigarettes, cannabis vaping and the management of lung injury associated with e-cigarette or vaping use were excluded. We also excluded animal studies, non-English articles, articles published before Jan. 1, 2010, study protocols, full texts not retrievable and publication duplicates.

Study selection

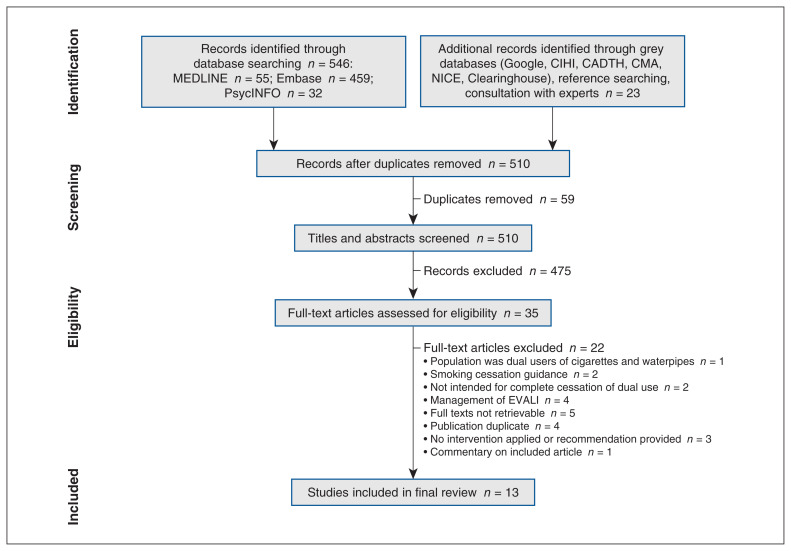

Two reviewers (A.K. and E.K.) independently screened each title and abstract for compliance with the inclusion criteria. Full-text review was undertaken by 2 reviewers (A.K. and E.K.), and any disagreements on final inclusion were resolved through discussions with other reviewers (R.S., R.D. and L.Z.). The detailed selection process of the papers is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram.41

Data extraction and data analysis

Custom-made data extraction forms were developed, which included general characteristics of included studies (author, year, study design, sample size, target population, objective, methods and primary outcome results), authors’ conclusions or recommendations, and limitations or special features (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/2/E336/suppl/DC1). We considered the World Health Organization’s and Statistics Canada’s standard age limits for defining target population such as adolescents (10–19 yr), youth (15–24 yr) and adults (25–64 yr) age groups.42,43 We presented descriptive statistics of the extracted data sets by calculating the total number of all papers in each category. Finally, we presented a narrative overview of our findings and, based on the identified knowledge gap, future research directions were provided.

Critical appraisal

Due to the variability of study designs of included papers, different critical appraisal tools were used to assess the risk of bias. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools for text and opinion, case reports, case series, quasiexperimental studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and qualitative research,44 which are widely accepted tools for the quality assessment of analytical studies,45 were used for most of the papers (Appendix 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/2/E336/suppl/DC1). These tools contained 6- to 13-item checklists, where for each item appraised, we assigned a score of 1 if the criterion was met, and 0 if the criterion was not met or was unclear. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a validated 23-item scale divided into 6 domains followed by 2 global rating items, was used for 1 paper (Appendix 4, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/2/E336/suppl/DC1).46 We modified the AGREE II tool by omitting 1 item in domain 5 (changing to a 22-item scale) as it was not applicable for the selected study. This was in accordance with procedures described in the AGREE II user manual.46 For each item in the AGREE II instrument, ratings were provided on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 7 indicated “strongly agree.”

Two reviewers (A.K. and E.K.) independently scored all papers using appropriate critical appraisal tools. For the JBI critical appraisal scores, disagreements were resolved through discussions between reviewers. AGREE II scores were developed by combining the scores of both reviewers, as described in the AGREE II user manual.46 As different tools were used for different papers, all critical appraisal scores were reported as a percentage of assigned numerical scores instead of individual points. Papers that scored 70% or greater, 50%–70% and less than 50% represented having a high, moderate and low quality, respectively.

Ethics approval

As we performed a scoping review of literature, the study was exempted from institutional ethics approval from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.47

Results

The search of academic electronic databases yielded 546 publications. An additional 23 publications were added through the grey literature search and hand searching of citation lists and professional networks. After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 510 papers were reviewed. Of the 35 papers that were eligible for full-text screening, 22 were excluded for various reasons (Figure 1). This resulted in 13 papers included in the final review.48–60 We did not find any publications providing recommendations on complete cessation of cigarettes and e-cigarettes for dual users. Hence, the final 13 papers reflected evidence or current practice recommendations on cessation interventions for exclusive e-cigarette use only (Table 1, Appendix 2).48–60

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow diagram showing study selection. Note: CADTH = Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, CIHI = Canadian Institute for Health Information, CMA = Canadian Medical Association, EVALI = e-cigarette or vaping use–associated lung injury, NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Table 1:

Summary statistics of included papers

| Characteristic | No. of papers n = 13 |

Author and year |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| United States | 11 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Graham et al., 2021;49 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 Owens et al., 2020;51 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Berg et al., 2021;56 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Silver et al., 201659 |

| Canada | 2 | Chadi et al., 2021;54 Health Canada, 202160 |

| Target population (age in years)* | ||

| Adolescent (10–19) | 4 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Owens et al., 2020;51 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Chadi et al., 202154 |

| Youth (15–24) | 11 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Graham et al., 2021;49 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Berg et al., 2021;56 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Silver et al., 2016;59 Health Canada, 202160 |

| Adult (25–64) | 2 | Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Sikka et al., 202157 |

| Study design | ||

| RCT | 1 | Graham et al., 202149 |

| Pretest–posttest experimental study | 1 | Graham et al., 202048 |

| Guidance or recommendation | 7 | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 Owens et al., 2020;51 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Berg et al., 202156 |

| Case report or case series | 3 | Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Silver et al., 201659 |

| Qualitative study | 1 | Health Canada, 202160 |

| Type of intervention recommended | ||

| Behavioural | 10 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Graham et al., 2021;49 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Berg et al., 2021;56 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Silver et al., 2016;59 Health Canada, 202160 |

| NRT | 6 | American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Silver et al., 201659 |

| Non-NRT | 3 | Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Gonzalvo et al., 201655 |

| Based evidence on vaping cessation | ||

| Yes | 7 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Graham et al., 2021;49 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 Berg et al., 2021;56 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Silver et al., 201659 |

| No | 6 | Owens et al., 2020;51 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Health Canada, 202160 |

| Based on critical appraisal scores | ||

| High quality (critical appraisal scores ≥ 70%) | 10 | Graham et al., 2021;49 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020;50 Owens et al., 2020;51 American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019;52 Hadland and Chadi, 2020;53 Chadi et al., 2021;54 Berg et al., 2021;56 Sikka et al., 2021;57 Sahr et al., 2020;58 Health Canada, 202160 |

| Moderate quality (critical appraisal scores 50%–70%) | 3 | Graham et al., 2020;48 Gonzalvo et al., 2016;55 Silver et al., 201659 |

| Low quality (critical appraisal scores < 50%) | 0 | |

Note: NRT = nicotine replacement therapy, RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Target population categories of adolescent and youth had overlaps with each other.

Of the 13 papers included,48–60 11 were conducted in the US, 2 papers were from Canada,54,60 and all were published within the last 6 years (Table 1). The general characteristics of the papers are presented in Appendix 2. Among the papers (n = 13), 7 were guidance or recommendation documents,50–56 1 was an RCT,49 1 was a pretest–posttest experimental study,48 2 were case reports,58,59 1 was a case series57 and 1 was a qualitative study.60 Among the target population categories, youth were the most commonly studied population (n = 11),48–50,52–54,56–60 followed by adolescents (n = 4)48,51,52,54 and adults (n = 2).55,57

Of the vaping cessation interventions discussed, behavioural interventions (i.e., 5As approach, motivational interviewing, individual or group counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness approach, “This is Quitting” text messaging program, smokeSCREEN videogame and smartphone apps) were recommended by 10 papers,48–50,53,54,56–60 nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (i.e., nicotine patch, gum, lozenge and spray) by 6 papers,52–55,57,59 combined behavioural counselling and NRT by 4 papers,53,54,57,59 non-NRT medications (i.e., bupropion and varenicline) for those aged 17 years and older by 3 papers53–55 and tapering of e-cigarette use by 2 papers58,60 (Table 1, Appendix 2). One of the included guidance documents included e-cigarette as a tobacco product and concluded that there was insufficient evidence61 to assess the net benefit of behavioural counselling and medications as cessation interventions among adolescents.51 They recommended that primary care providers balance the benefits and harms of interventions while providing cessation services on a case-by-case basis.51 The “This is Quitting” text messaging program, which has been tested by a pretest–posttest experimental study48 and an RCT,49 was recommended by 2 other guidance documents.50,56

The evidence or recommendations provided by 7 papers were based on interventions applied with the intention of vaping cessation,48–50,56–59 while 5 papers applied evidence from existing smoking cessation interventions.51–55 One paper60 described self-reported preference for vaping cessation interventions in a sample of e-cigarette users (Table 1, Appendix 2). Ten papers49,54–56,59 were considered to be of high quality, 3 papers48,55,59 were rated moderate quality and none were rated low quality (Table 1, Appendices 3 and 4).

Interpretation

We found that the current evidence on vaping cessation interventions is limited. Although we did find 1 RCT evaluating the effectiveness of the “This is Quitting” text messaging program,49 the application of other cessation interventions, particularly NRT and non-NRT for the purpose of vaping cessation, has not yet been thoroughly investigated. There are some important differences between smoking and vaping. In addition to e-cigarettes delivering higher nicotine concentrations than some popular brands of conventional cigarettes, the power on some e-cigarettes can be adjusted to increase the amount of nicotine delivered. 4,62,63 Users’ personal beliefs about the relative harm of e-cigarettes,64 the social acceptability of vaping and other beliefs,65 motivations and needs related to e-cigarette use may also distinguish vaping from smoking.66 Understanding these differences is crucial in developing guidance for vaping cessation interventions.

We found several vaping cessation recommendations and guidance documents published by reputable organizations such as Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,50 US Preventive Services Task Force,51 American Academy of Pediatrics,52 Canadian Paediatric Society54 and Health Canada.60 Although they generally scored high on critical appraisal (Table 1), none of them except the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration publication based their evidence on interventions targeting vaping cessation. The US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement was based on 12 RCTs included in a meta-analysis, but all of these studies examined smoking cessation as an outcome.51 In this respect, despite the task force’s conclusion of insufficient evidence in support of behavioural counselling and medications for tobacco product cessation, the applicability of this recommendation for vaping cessation is questionable (Table 1, Appendix 2). However, currently, 2 RCTs are recruiting participants for evaluation of the effectiveness of behavioural interventions (i.e., Goal2QuitVaping smartphone app, phone counselling, text messaging program) and NRT for vaping cessation among the youth population. 67,68 The findings from these studies would improve our understanding and provide the evidence base for the application of established smoking cessation interventions for vaping cessation.

The only intervention that has been rigorously tested for vaping cessation was “This is Quitting,” a text messaging–based behavioural intervention program by the Truth Initiative. The program has shown promising results in engaging the participants on a 3-month follow-up, with 60.8% of respondents self-reporting reduced e-cigarette use or vaping cessation 14 days after their quit date.48 When evaluated by an RCT, the abstinence rate at 7-month follow-up was 24.1% among the participants receiving the intervention, who showed 1.39 times (95% confidence interval 1.15–1.68, p < 0.001) more likelihood of remaining abstinent than controls.49 In addition to being proven effective, the program has been recommended by 2 other guidance documents (Appendix 2).50,56 However, the RCT was limited by lack of biochemical verification of abstinence and providing considerable monetary compensation. 49 Moreover, mobile health interventions are generally limited by high dropout rates,69 and text messaging–based smoking cessation programs were found more beneficial when combined with other cessation supports.70

Some important features emerged from the qualitative study by Health Canada,60 such as preference by the e-cigarette users for a customizable quit plan, the option of tapering use then quitting vaping, and the importance of support groups or friends to help quit vaping, which should be taken into account when formulating e-cigarette cessation guidelines. In addition, the availability of validated tools is crucial to assess vaping dependence among e-cigarette users. Although several papers have recommended or used modified versions of smoking cessation tools, including Hooked on Nicotine Checklist; Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; Modified Version of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire; Screening to Brief Intervention; Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and other Drugs; and Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble,52–54,58,59 none of them have been validated to assess for vaping dependence.

Most of the papers included youth as their target population (Table 1). However, 2 case reports presented cessation interventions for past smokers who used e-cigarettes as a tool for smoking cessation and further sought help to quit vaping (Appendix 2).58,59 Although there is controversy about whether former smokers who switched to vaping for smoking cessation should be encouraged to quit vaping, a recent meta-analysis reported a higher risk of smoking relapse among former smokers who regularly used e-cigarettes compared with those who did not.71 Moreover, former smokers reported reasons like no need for an e-cigarette to stay quit, not satisfying, safety concerns and costs behind stopping vaping.72 Hence, in addition to conducting future research on the long-term impact of complete abstinence, vaping cessation programs for former smoker populations should emphasize these motivations.

We did not find any papers providing evidence or recommendations for the complete cessation of both electronic and combustible cigarettes for dual users. Although 1 recent RCT was conducted to evaluate behavioural interventions among dual users,73 the primary target of the interventions was smoking cessation, and the researchers allowed ongoing use of e-cigarettes to facilitate smoking cessation in their study. Their results showed that the targeted intervention resulted in significant smoking abstinence throughout the 18-month treatment compared with the control group. Although vaping decreased over the same period, there was not a significant difference between the groups. However, as expected, vaping was associated with a higher probability of smoking abstinence.73 Similarly, Graham and colleagues conducted a secondary data analysis examining the impact of the “This is Quitting” text messaging program on dual use cessation. They reported that a significantly higher proportion of participants in the intervention arm (25.9%) were dual abstinent compared with the control arm (18.5%).74 However, the RCT on “This is Quitting”49 was designed for the purpose of vaping cessation, and the researchers did not provide evidence of whether the participants used any other smoking cessation interventions.

The summary of the research gaps and future research directions for e-cigarette and dual use cessation interventions are presented in Table 2. More rigorously designed RCTs should be undertaken for evaluating the effectiveness of different behavioural therapies, NRT and non-NRT for vaping cessation and dual use cessation. The effectiveness of vaping cessation interventions should be evaluated for different population groups, including youth, adults, former smokers, dual users and polytobacco users. Nicotine dependence tools should be modified and validated for e-cigarette users. The duration of abstinence or risk of relapse should be evaluated longitudinally for former smokers who switched to vaping and underwent vaping abstinence thereafter. Dual use cessation is a stepwise process, and switching dual users to exclusive vaping first and then providing support for vaping cessation might be an effective strategy and should be evaluated by future research.

Table 2:

Future research directions for cessation interventions targeted toward exclusive e-cigarette users and dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes

| Population | Knowledge gaps | Future research directions |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive e-cigarette users | Lack of good-quality and well-designed clinical trials evaluating different types of behavioural interventions for vaping cessation | Rigorously designed RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of different behavioural therapies (i.e., 1-on-1 counselling, group therapy, smartphone app, web-based program) for vaping cessation with biochemical proof of abstinence |

| No published clinical trials evaluating effectiveness of NRT and non-NRT for vaping cessation | Rigorously designed RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of NRT and non-NRT for vaping cessation with biochemical proof of abstinence | |

| Lack of clinical trials evaluating vaping cessation interventions for different population groups | RCTs should evaluate effectiveness of vaping cessation interventions for different population groups (i.e., youth v. adult, former smokers who switched to exclusive vaping, individuals with other tobacco use, other substance users) | |

| Lack of validated nicotine dependence tools targeted for e-cigarettes users | Validate the established nicotine dependence tools (i.e., HONC, FTND, m-FTQ, S2BI, CRAFFT, BSTAD) for assessing vaping dependence | |

| Lack of evidence examining whether former smokers who switched to vaping relapse following vaping cessation | Longitudinally assess duration of abstinence or relapse of smoking following vaping cessation interventions for former smokers who switched to exclusive vaping | |

| Dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes | No published clinical trials evaluating interventions targeted for complete abstinence among dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes | Rigorously designed RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of stepwise cessation interventions — first smoking cessation followed by vaping cessation among dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes |

Note: BSTAD = Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and other Drugs, CRAFFT = Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, HONC = Hooked on Nicotine Checklist, mFTQ = Modified Version of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire, NRT = nicotine replacement therapy, RCT = randomized controlled trial, S2BI = Screening to Brief Intervention.

Limitations

The findings of our review should be interpreted with consideration of a few key limitations. Our intention to find guidance on the complete cessation of cigarette and e-cigarette use among dual users was not met. We did not elaborate on vaping cessation programs undertaken by different organizations, as our goal was to identify evidence or recommendations for different types of vaping cessation interventions, not to do a comparative analysis between programs. However, we investigated whether the organizations based their recommendations on available evidence on vaping cessation and found only 1 of them (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommendation)50 did that. Almost all of the studies were conducted in the US, where the pay-for-services model might act as an incentive to provide cessation services.75,76 However, these findings may not be generalizable to other jurisdictions that do not have a pay-for-services model.

Conclusion

There is currently little evidence in support of effective vaping cessation interventions and no evidence on dual use cessation. An evidence-based vaping or dual use cessation guideline should address different subpopulations and provide several affordable, safe and effective intervention options for users to choose based on their personal preference.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Laurie Zawertailo provided an expert report on the health effects of e-cigarettes to Cambridge LLP, is chair of the data and safety monitoring board for a Cytisine randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by investigators at the Ottawa Heart Institute (2021–2025), is a member of the trial steering committee for an RCT of e-cigarette effectiveness for smoking cessation in individuals with severe mental illness (2022–2026) and is a member of the scientific steering committee for the National Forum on Tobacco and Vaping Control February 2023 virtual conference. Peter Selby reports grant funding awarded through his institution from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Health Canada, Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute, Medical Psychiatry Alliance, Ontario Ministry of Health, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Public Health Agency of Canada, and Pfizer. Dr. Selby also reports receipt of honoraria for speaking engagements from TeleECHO, Center for Research on Flavored Tobacco, Ottawa Heart Association, Veterans Affairs Canada, American Society of Addiction Medicine, ASAM (American Society of Addiction Medicine) Fundamentals of Addiction Medicine, Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, and the University of Toronto. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Robert Schwartz, Laurie Zawertailo, Peter Selby, Chantal Fougere and Rosa Dragonetti contributed to the conceptualization, methodology and supervision of the study, and obtaining funding. Anasua Kundu conducted the database search, data analysis and primary drafting of the manuscript. Anasua Kundu and Erika Kouzoukas completed title and abstract screening, full-text review and data extraction. All authors have reviewed and revised the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health (funding no. 72-2021-250). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and the funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data sharing: This review used aggregate, published data that are publicly available. No additional data are available for sharing.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/2/E336/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, et al. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students: United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1276–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole AG, Aleyan S, Battista K, et al. Trends in youth e-cigarette and cigarette use between 2013 and 2019: insights from repeat cross-sectional data from the COMPASS study. Can J Public Health. 2021;112:60–9. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00389-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2016. [accessed 2021 July 19]. Available https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538680/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khouja JN, Suddell SF, Peters SE, et al. Is e-cigarette use in non-smoking young adults associated with later smoking? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2020;30:8–15. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. High international electronic cigarette use among never smoker adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:595–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, et al. Reasons for electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:196–200. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amrock SM, Lee L, Weitzman M. Perceptions of e-cigarettes and noncigarette tobacco products among US youth. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20154306. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2021. [accessed 2022 July 28]. modified 2022 May 5. Available https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220505/dq220505c-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirbolouk M, Charkhchi P, Kianoush S, et al. Prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use among U.S. adults: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:429–38. doi: 10.7326/M17-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King JL, Reboussin D, Ross JC, et al. Polytobacco use among a nationally representative sample of adolescent and young adult e-cigarette users. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid JL, Rynard VL, Czoli CD, et al. Who is using e-cigarettes in Canada? Nationally representative data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use among Canadians. Prev Med. 2015;81:180–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) summary of results for 2020. Ottawa: Health Canada; [accessed 2022 May 13]. modified 2022 Apr. 1. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2020-summary.html#n2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the Health eHeart Study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim C-Y, Paek Y-J, Seo HG, et al. Dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes is associated with higher cardiovascular risk factors in Korean men. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5612. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62545-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes AC, Xie W, Wilson AE, et al. Association of cigarette and electronic cigarette use patterns with levels of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers among US adults: population assessment of tobacco and health study. Circulation. 2021;143:869–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.E-cigarettes could be prescribed on the NHS in world first [news release] Department of Health and Social Care and Office for Health Improvement and Disparities; 2021. Oct 29, [accessed 2022 Aug. 9]. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e-cigarettes-could-be-prescribed-on-the-nhs-in-world-first. [Google Scholar]

- 18.FDA permits marketing of e-cigarette products, marking first authorization of its kind by the agency [news release] Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration; 2021. Oct 12, [accessed 2022 Aug. 9]. Available https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-e-cigarette-products-marking-first-authorization-its-kind-agency. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quit vaping Smokefree Teen. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; [accessed 2021 Aug. 27]. Available https://teen.smokefree.gov/quit-vaping. [Google Scholar]

- 20.E-cigarettes & vaping. Rochester (NY): American Lung Association; [accessed 2021 Aug. 27]. Available: https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/e-cigarettes-vaping. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quitting e-cigarettes. Washington (DC): Truth Initiative; 2019. [accessed 2021 Aug. 27]. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/quitting-smoking-vaping/quitting-e-cigarettes. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobacco: e-cigarette [news release] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. May 25, [accessed 2021 Aug. 27]. Available https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/tobacco-e-cigarettes. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemperer EM, Villanti AC. Why and how do dual users quit vaping? Survey findings from adults who use electronic and combustible cigarettes. Tob Induc Dis. 2021;19:12. doi: 10.18332/tid/132547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuccia AF, Patel M, Amato MS, et al. Quitting e-cigarettes: quit attempts and quit intentions among youth and young adults. Prev Med Rep. 2021;21:101287. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klemperer EM, West JC, Peasley-Miklus C, et al. Change in tobacco and electronic cigarette use and motivation to quit in response to COVID-19. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:1662–3. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith TT, Nahhas GJ, Carpenter MJ, et al. Intention to quit vaping among United States adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:97–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amato MS, Bottcher MM, Cha S, et al. “It’s really addictive and I’m trapped:” a qualitative analysis of the reasons for quitting vaping among treatment-seeking young people. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106599. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer AM, Smith TT, Nahhas GJ, et al. Interest in quitting e-cigarettes among adult e-cigarette users with and without cigarette smoking history. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e214146. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salloum RG, Lee J, Porter M, et al. Evidence-based tobacco treatment utilization among dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Prev Med. 2018;114:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor S, Pelletier H, Bayoumy D, et al. Interventions to prevent harms from vaping: report for the Central East TCAN. Toronto: Ontario Tobacco Research Unit; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbiest M, Brakema E, van der Kleij R, et al. National guidelines for smoking cessation in primary care: a literature review and evidence analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:2. doi: 10.1038/s41533-016-0004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu A, Kouzoukas E, Zawertailo L, et al. Protocol for a scoping review of guidance on cessation interventions for electronic cigarettes and dual electronic and combustible cigarettes use. OSF. 2021. [accessed 2021 Sept. 14]. Available: https://osf.io/79dxp/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu R, Kundu A, Mitsakakis N, et al. Tob Control. 2021. Aug 27, Machine learning applications in tobacco research: a scoping review. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kundu A, Chaiton M, Billington R, et al. Machine learning applications in mental health and substance use research among the LGBTQ2S+ population: scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9:e28962. doi: 10.2196/28962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minian N, Corrin T, Lingam M, et al. Identifying contexts and mechanisms in multiple behavior change interventions affecting smoking cessation success: a rapid realist review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:918. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08973-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:1926–36. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adolescent health. Geneva: World Health Organization; [accessed 2021 July 14]. Available https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health/#tab=tab_1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Age categories, life cycle groupings. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; [accessed 2021 July 14]. modified 2017 May 8. Available: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/concepts/definitions/age2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Critical appraisal tools. Adelaide (Australia): Joanna Briggs Institute; [accessed 2021 July 14]. Available: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma L-L, Wang Y-Y, Yang Z-H, et al. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil Med Res. 2020;7:7. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med. 2010;51:421–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CAMH Research Ethics Board terms of reference. Version: April 1, 2019. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH); 2019. [accessed 2021 July 14]. Available https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/camh-reb-terms-of-reference-2019-pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graham AL, Jacobs MA, Amato MS. Engagement and 3-month outcomes from a digital e-cigarette cessation program in a cohort of 27 000 teens and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:859–60. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham AL, Amato MS, Cha S, et al. Effectiveness of a vaping cessation text message program among young adult e-cigarette users: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:923–30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Reducing vaping among youth and young adults. Rockville (MD): National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP2006-01-003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Preventive Services Task Force. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1590–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients: information for pediatricians. Itasca (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019. [accessed 2021 July 14]. Available https://downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hadland SE, Chadi N. Through the haze: what clinicians can do to address youth vaping. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chadi N, Vyver E, Bélanger RE. Protecting children and adolescents against the risks of vaping. Paediatr Child Health. 2021;26:358–74. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxab037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalvo JD, Constantine B, Shrock N, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems and a suggested approach to vaping cessation. AADE Pract. 2016;4:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berg CJ, Krishnan N, Graham AL, et al. A synthesis of the literature to inform vaping cessation interventions for young adults. Addict Behav. 2021;119:106898. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sikka G, Oluyinka M, Schreiber R, et al. Electronic cigarette cessation in youth and young adults: a case series. Tob Use Insights. 2021;14:1179173X211026676. doi: 10.1177/1179173X211026676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sahr M, Kelsh SE, Blower N. Pharmacist assisted vape taper and behavioral support for cessation of electronic nicotine delivery system use. Clin Case Rep. 2019;8:100–3. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silver B, Ripley-Moffitt C, Greyber J, et al. Successful use of nicotine replacement therapy to quit e-cigarettes: lack of treatment protocol highlights need for guidelines. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4:409–11. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Youth and young adult vaping cessation research: executive summary. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2021. [accessed 2021 July 14]. Available: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/sc-hc/H14-359-2021-1-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selph S, Patnode C, Bailey SR, et al. Primary care-relevant interventions for tobacco and nicotine use prevention and cessation in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020;323:1599–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, et al. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4133. doi: 10.1038/srep04133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. 2022;31:e88–93. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Churchill V, Nyman AL, Weaver SR, et al. Perceived risk of electronic cigarettes compared with combustible cigarettes: direct versus indirect questioning. Tob Control. 2020;30:443–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.East KA, Hitchman SC, McNeill A, et al. Social norms towards smoking and vaping and associations with product use among youth in England, Canada, and the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107635. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sapru S, Vardhan M, Li Q, et al. E-cigarettes use in the United States: reasons for use, perceptions, and effects on health. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1518. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09572-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Research and innovation to stop e-cigarette/vaping in young adults (RISE) ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04974580. 2021. [accessed 2021 Sept. 8]. updated 2022 Oct. 4. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04974580?cond=vaping+cessation&draw=2&rank=4.

- 68.Goal2QuitVaping for nicotine vaping cessation among adolescents. Clinical-Trials.gov: NCT04951193. 2021. [accessed 2021 Sept. 8]. updated 2022 July 27. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04951193?cond=vaping+cessation&draw=2&rank=3.

- 69.Meyerowitz-Katz G, Ravi S, Arnolda L, et al. Rates of attrition and dropout in app-based interventions for chronic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e20283. doi: 10.2196/20283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. Mobile phone text messaging and app-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:CD006611. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barufaldi LA, Guerra RL, de Cássia R, et al. Risk of smoking relapse with the use of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review with meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Tob Prev Cessat. 2021;29:29. doi: 10.18332/tpc/132964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yong H-H, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Reasons for regular vaping and for its discontinuation among smokers and recent ex-smokers: findings from the 2016 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Addiction. 2019;114(Suppl 1):35–48. doi: 10.1111/add.14593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martinez U, Simmons VN, Drobes DJ, et al. Targeted smoking cessation for dual users of combustible and electronic cigarettes: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e500–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30307-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graham AL, Cha S, Papandonatos GD, et al. E-cigarette and combusted tobacco abstinence among young adults: secondary analyses from a U.S.-based randomized controlled trial of vaping cessation. Prev Med. 2022 June 28; doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107119. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruse GR, Chang Y, Kelley JHK, et al. Healthcare system effects of pay-for-performance for smoking status documentation. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:554–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Curry SJ, Keller PA, Orleans CT, et al. The role of health care systems in increased tobacco cessation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:411–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.