Abstract

Background

Alaska Native and American Indian (ANAI) communities in Alaska are disproportionately affected by commercial tobacco use. Financial incentive interventions promote cigarette smoking cessation, but family-level incentives have not been evaluated. We describe the study protocol to adapt and evaluate the effectiveness and implementation of a remotely delivered, family-based financial incentive intervention for cigarette smoking among Alaskan ANAI people.

Methods

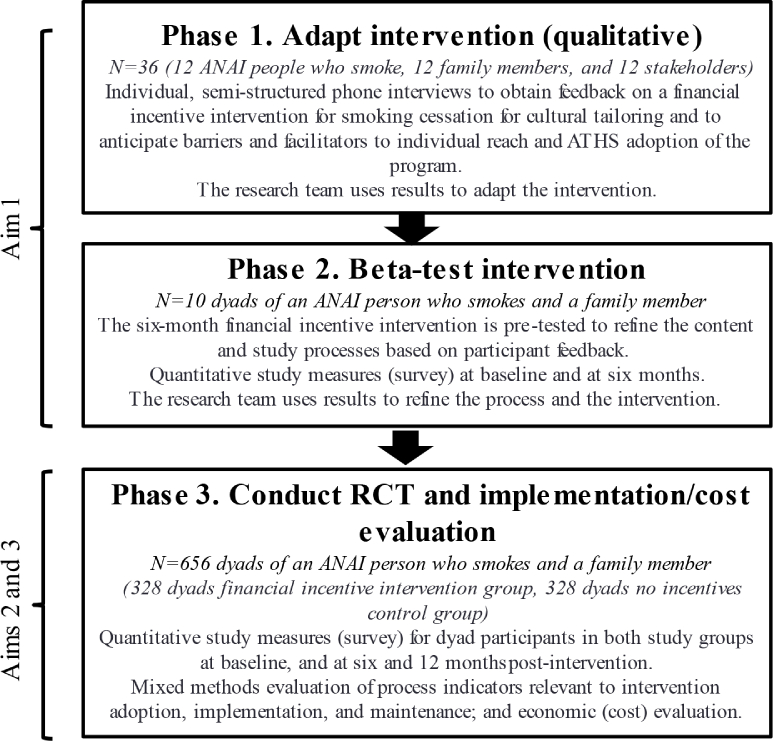

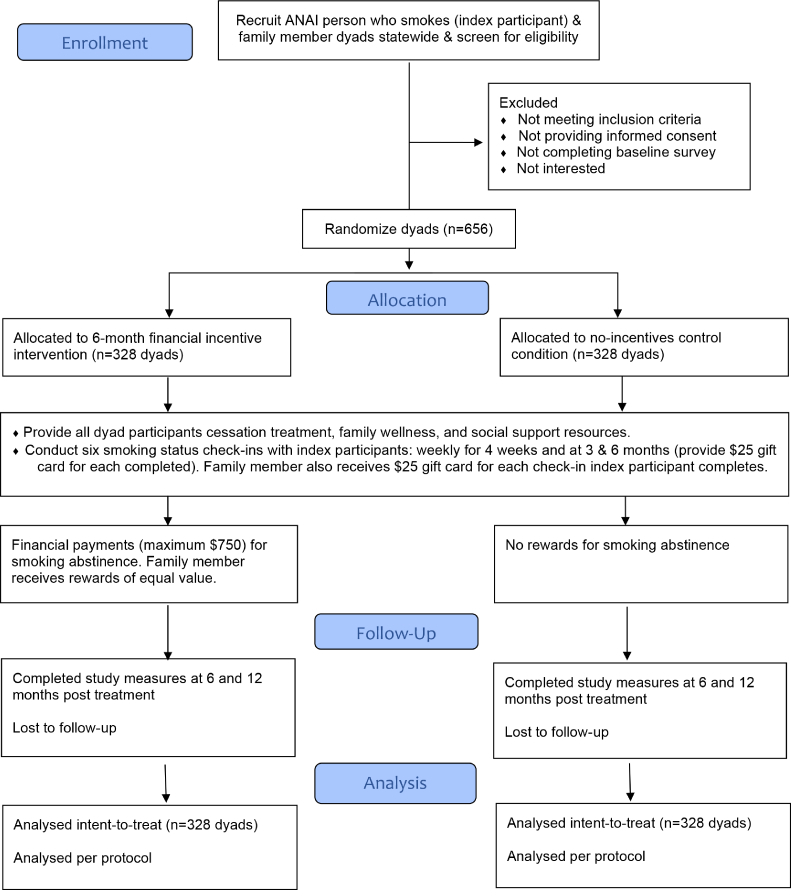

The study has 3 phases: 1) qualitative interviews with ANAI adults who smoke, family members, and stakeholders to inform the intervention, 2) beta-test of the intervention, and 3) randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating intervention reach and effectiveness on verified, prolonged smoking abstinence at 6- and 12-months post-treatment. In the RCT, adult dyads (ANAI person who smokes [index participant] and family member) recruited throughout Alaska will be randomized to a no-incentives control condition (n = 328 dyads) or a 6-month incentive intervention (n = 328 dyads). All dyads will receive cessation support and family wellness materials. Smoking status will be assessed weekly for four weeks and at three and six months. Intervention index participants will receive escalating incentives for verified smoking abstinence at each time point (maximum $750 total); the family member will receive rewards of equal value.

Results

A community advisory committee contributed input on the study design and methods for relevance to ANAI people, particularly emphasizing the involvement of families.

Conclusion

Our study aligns with the strength and value AIAN people place on family. Findings, processes, and resources will inform how Indigenous family members can support smoking cessation within incentive interventions.

Clinical Trials Registry

Keywords: Alaska Native and American Indian people, Family, Financial incentives, Intervention, Smoking, Smoking cessation

Highlights

-

•

This is the first Indigenous incentive intervention created for smoking cessation.

-

•

Alaska Native community input was used to embed cultural values and strengths.

-

•

Cultural strengths and values stress reliance on family systems and support.

-

•

Family members receive rewards for supporting smoking cessation.

1. Introduction

In Alaska, cigarette smoking prevalence among Alaska Native and American Indian (ANAI) people is more than double that of non-Native adults (37% vs. 17%) [1]. Unlike other U.S. Indigenous populations, tobacco was not available to ANAI communities before contact with outside traders and, thus, it is not used in traditional ceremonies [1,2]. Despite concerted efforts by Alaska Tribal Health System (ATHS) organizations and the State of Alaska health department, current smoking cessation strategies, most of which are individual-focused, have not effectively reduced smoking prevalence among ANAI people [1,3,4]. Alaska's geography (largely remote and roadless) and harsh climate further limit treatment access and reach. Without effective cessation strategies, many ANAI health disparities persist, including lung and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality [1,5,6]. Annually, smoking costs Alaska $575 million in direct medical expenditures and $261 million in lost productivity from smoking-related deaths [1].

Given challenges and resultant service-delivery gaps, ATHS leaders emphasize the critical need for novel, accessible, effective smoking cessation interventions for ANAI people. We describe our study protocol to adapt and evaluate the effectiveness and implementation of an innovative, remotely delivered, culturally relevant, ANAI family-based financial incentive intervention for smoking cessation. The study name, Aniqsaaq (pronounced ahh-nik-suk), means “to breathe” in the Alaska Native Inupiaq language. Although the name originates from the Inupiaq language, its meaning has universal relevance statewide.

Based on behavioral economics, financial incentive interventions are evidence-based [7] and offer a simple public health approach to promote smoking cessation. Behavioral economic theory provides a framework to understand when and how people make choices [8,9]. Its central tenet is that although humans are hard-wired to act instinctively, they may need a nudge to make decisions in their best interest [8]. Financial incentives provide an immediate non-nicotine reward for smoking abstinence addressing a major barrier to smoking cessation, delayed discounting [8,10]. Delayed discounting or impulsive choice is a preference for smaller, more immediate outcomes (e.g., nicotine effects) over larger delayed outcomes (e.g., health, money saved from not smoking) with delayed rewards more likely to be discounted [11]. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions providing total cash payments of $750 to $1650 for biochemically verified smoking abstinence have demonstrated >2-fold increases in the smoking abstinence rates a full year after the rewards were discontinued compared with no incentives (odds ratios: 2.48–2.72) [[12], [13], [14]]. Technological innovations in remote monitoring and providing immediate monetary rewards enhance potential intervention reach and scalability [15]. McDonell and colleagues found that an incentive-based intervention was acceptable and effective for reducing alcohol use among ANAI communities, including in Alaska [16]. No published studies have evaluated financial incentive interventions for smoking cessation among ANAI people.

Family relationships could be another means to support smoking cessation within a financial incentive intervention [8,9]. Research in the general population documents the influence of naturally occurring social support networks (e.g., family members) on smoking cessation [17,18]. Moreover, social influence from family/friends was associated with successful cessation among individuals receiving a financial incentive intervention [19]. A pilot study [20] rewarding pregnant women for smoking abstinence included optional enrollment and support training for a family member; 57% opted to include a family member. The biochemically verified cessation rates at the end of eight weeks of treatment were higher than in prior trials offering incentives during pregnancy (63% vs. 34%), although the study did not compare abstinence rates for women with and without a family member enrolled, nor include rewards for the enrolled family member. While promising, studies using collective rewards with naturally occurring social networks (e.g., coworker teams) have not focused on family supports [21]. As noted in our prior tobacco treatment studies [3,4,22] and supported by community input into designing this study, family is a strong cultural value shared by all ANAI ethnicities and an important motivator for quitting smoking expressed by ANAI people who smoke statewide in Alaska. This is consistent with the ANAI cultural value of interdependence, which is a relationship-based, collaborative approach to decision making and lifestyle changes, and reliance on family systems rather than individual strengths [23,24].

Addressing these gaps, our study aims to: (1) Adapt an effective 6-month financial incentive intervention for ANAI adults who smoke and family members; (2) Conduct a RCT to evaluate participant reach and treatment effectiveness of the family-based incentive intervention compared with the control condition on biochemically confirmed, prolonged smoking abstinence at 6- and 12-months post treatment; and (3) Evaluate key process indicators relevant to intervention adoption, implementation, and maintenance (e.g., perceived feasibility, perceived challenges), and conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis to support further adaptation and dissemination. We hypothesize that the intervention will be associated with greater prolonged smoking abstinence compared to a no-incentives control condition.

2. Methods

Our study was approved by the Alaska Area and Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Boards and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC). The trial design is in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for RCTs [25], and the trial is registered with the Clinical Trials Registry (NCT05209451). The research team includes ANAI persons and has multidisciplinary expertise that includes implementing culturally relevant health and wellness interventions with ANAI communities, tobacco treatment, incentive interventions for addictions, mixed methods, implementation science, biostatistics, and health economics.

The study incorporated a community-based participatory approach into all research processes [26], as requested by Tribal leaders in ANAI communities [27]. Since November 2018, we repeatedly sought input on the research questions and study design with the ANTHC Research Consultation Committee, a community advisory committee constituted of ANAI individuals. Members advise researchers on various projects. The make-up of the group varies based on availability, but all are ANTHC employees with a self-reported interest in research with ANAI people and includes people from urban and rural Alaska and/or with family from or living in these communities.

We will continue to consult with this committee for input on study implementation and dissemination activities. We also discussed the study with the statewide Alaska Native Elders Health Advisory Board staffed by ANTHC. Study results will be shared with all study participants via mailed newsletters.

2.1. Projected financial incentive intervention

The intervention will include evidence-based financial incentive components leveraging concepts from behavioral economic theory [8,9]. Based on initial community feedback and the literature, we plan to include the intervention components described in Table 1 and will make adaptations using input from our Aim 1 formative work.

Table 1.

Planned family-based financial incentive intervention components.

| Component | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention duration |

|

|

| Smoking status check-ins |

|

|

| Remote objective monitoring of smoking status |

|

|

| Definition of verified cigarette smoking abstinence among index participants |

|

|

| Escalating incentive scheme and reward value |

|

|

| Immediacy of rewards |

|

|

| Reset |

|

|

| Regret aversion |

|

|

| Text messages |

|

|

Table note: CO = carbon monoxide, ST = smokeless tobacco including Iqmik (an Alaska homemade product), NRT = nicotine replacement therapy.

2.2. Study overview

We will conduct the research in three phases (Fig. 1). In phase 1, we will use qualitative in-depth interviews to culturally adapt the intervention so that it promotes healthy traditional and current lifestyle and practices and values that will resonate with ANAI people. In phase 2, we will beta-test the intervention. In phase 3, we will conduct a RCT to evaluate intervention reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and longer-term maintenance, including cost.

Fig. 1.

Alaska Native family-based financial incentive intervention study overview.

2.3. Participants and recruitment

For all study phases, we will recruit ANAI adults who smoke cigarettes (index participants) and adult family members statewide. We will advertise on social media platforms (e.g., Facebook), Tribal newsletters, newspapers, and websites, including organizations serving families. Recruitment advertisements will include the study name, Aniqsaaq and its meaning (to breathe), and a blanket toss photo. The blanket toss was first used to sight whales during a whale hunt and now used during gatherings and celebrations statewide to reflect community and family supporting and uplifting each other [37]. Screening, informed consent, and enrollment will occur by phone or online. Index participant and family member participant eligibility criteria are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Index participant eligibility and rationale for index participants and family members in all three study phases.

| Study Inclusion Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Index participants | |

| ANAI person (based on self-reported race/ethnicity) residing in Alaska. Both men and women will be included. | An estimated 27,712 ANAI adults using tobacco (i.e., 37% of total ANAI persons ages 21 and older [1,38]) are potentially eligible. |

| Aged ≥21 years | Legal smoking age in Alaska is 21 years |

| Self-report cigarette smoking in the past 7 days and (phases 2 and 3 only) biochemically verified with breath expired air CO ≥ 4 ppm and saliva cotinine ≥30 n/ml (positive Alere™ iScreen result). | Incentives are offered for smoking abstinence with the intervention. Thus, it is important to verify the individual currently smokes at study enrollment. |

| Smoked ≥3 cigarettes per day (cpd) over the past 3 months. | Includes “light” smoking as prior studies found that ANAI people reporting “light” smoking (7.8 cpd) have cotinine concentrations equivalent to White “heavy” smoking (15 cpd), due to nicotine metabolism differences [39]. |

| Phases 2 and 3 only: Current smoking status will be biochemically verified. | |

| Cigarettes are the main tobacco product used if other nicotine/tobacco products are used. | Cigarette smoking paired with ST use is prevalent in some Alaska rural regions [1]; thus, results are more generalizable if other tobacco use is allowed. |

| Considering or willing to make a quit attempt. | Study promotes quitting smoking. |

| No use of cessation pharmacotherapy or stop smoking program in the past 3 months. | Study promotes quitting smoking. |

| Has an adult family member who would be supportive of their efforts to quit smoking and (in phases 2 and 3) will enroll in the study. | Study focuses on ANAI families. |

| Phases 2 and 3 enroll dyads and thus requires a family member to also enroll. | |

| No other index participant from the same household has enrolled. | Facilitates obtaining different perspectives in phase 1. Mitigates potential lack of independence of households/social networks in phases 2 and 3. Reduces the risk for cross-condition contamination in phase 3. |

| Phases 2 and 3 only: Owns or has access to a mobile phone or tablet with internet and text messaging capabilities (or will be loaned an iPad with data plan remuneration for the study duration). | Facilitates completion of the six smoking check-ins and receiving text messages during the treatment phase. |

| Phase 3 only: Has not participated in a prior study phase. | Mitigates potential lack of independence of households/social networks and reduces the risk for cross-condition contamination. |

| Provides informed consent. | Verbal consent in phase 1, written consent in phases 2 and 3. |

| Family member participants | |

| Defined as family by the index participant. | Initial community feedback suggested a broad definition of family member and includes household or non-household members, and individuals who smoke or do not smoke. |

| Both men and women and all races will be included. | |

| Aged ≥21 years. | Enrolled family members may also smoke. The legal smoking age in Alaska is 21 years. |

| Provides informed consent. | Verbal consent in phase 1, written consent in phases 2 and 3. |

| Enrolled to support only one index participant. | Facilitates obtaining different perspectives in phase 1. Mitigates potential lack of independence of households/social networks in phases 2 and 3. Reduces the risk for cross-condition contamination in phase 3. |

| Phases 2 and 3 only: Owns or has access to a mobile phone or tablet with internet and text messaging capabilities (or will be loaned an iPad with data plan remuneration for the study duration). | Facilitates receiving text messages during the treatment phase. |

| Phase 3 only: Has not participated in a prior study phase | Mitigates potential lack of independence of households/social networks and reduces the risk for cross-condition contamination. |

Table note: ANAI = Alaska Native or American Indian, CO = carbon monoxide, ST = smokeless tobacco.

ATHS stakeholders will be invited by ANTHC research staff to participate in the Phase 1 formative work through phone and email correspondence using a statewide list to ensure urban and rural representation. ANAI and non-ANAI adult stakeholders will be eligible to participate if they are at least 18 years old and work within the ATHS or otherwise support ANAI people in tobacco treatment or health education, advocate for tobacco treatment, and/or serve as an Elder or Tribal leader.

To enhance feasibility and generalizability, we place no eligibility restrictions on family member's relationship type, place of residence, or smoking status. Family-based smoking and addiction treatment studies often conceptualize family as an individual's closest emotional connections, with no single immutable definition [40]. ANAI community members suggested we involve one family member as the “agent of change” and allow the index participant to define and select who they consider family. Involving one family member is consistent with successful family-focused smoking cessation [41] and addiction [40,42] treatment models. In ANAI communities, extended family is defined as a network of relations across different households that affects one's identity and role in the community, transmits culture, and conserves family patterns [43]. In prior RCTs [44] of social support interventions for smoking cessation, about half of support persons did not live with the person who smoked. Of 497 rural ANAI Alaskan households, 50% experienced a change in household members in one year [45]. Some index participants may live alone, or a trusted/safe family member may not reside in the same household. Domestic violence is a concern in Alaska where, irrespective to race or ethnicity, 43% of women and 30% of men report having experienced intimate partner violence, sexual violence, or stalking [46]. Alaska ranks third in the nation for lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence against women [46]. Index participants will be encouraged to select someone they trust to support them in quitting. We will allow the participant to change their selected family member if needed, although we anticipate changes mid study will be rare.

Because the literature offers little guidance [47], we will explore the effect of the selected family member's smoking status in the context of our research. National data indicate 44% of adults who smoke are exposed to others who smoke in their home [48]. Thus, other adults who smoke may best better reflect the social support network within populations with a high smoking prevalence, such as ANAI people [48]. The option to include a family member who smokes enhances recruitment feasibility. We will explore if family member smoking status moderates intervention effects and whether intervention effects are found on family members' smoking status in Phase 3 of our study to inform future research in this area.

2.4. Phase 1 (qualitative)

This formative phase will use behavioral economic theory [8,9], cultural variance [49,50], and dissemination and implementation [51,52] frameworks to design intervention messages and parameters, and to anticipate potential facilitators and barriers to reach and future adoption within the ATHS. We will solicit input from ANAI adults who smoke, family members, and ATHS stakeholders to develop messaging that resonates with ANAI values as well as healthy traditional and current lifestyle, practices, and activities.

We will conduct semi-structured, individual phone interviews with three groups: (1) ANAI adults who smoke, (2) family members, and (3) ATHS stakeholders (see section 2.3). With 10–15 interviews recommended per group to reach data saturation [53]; thus, we estimate 12 interviews per group. Participants will be purposefully sampled [54] to maximize diversity in the index participants’ sex, rural/urban location, and residence with family member; and family member smoking status.

Interviews conducted by trained research staff will last about 60 min. A brief description of the intervention will be sent to participants for review before or during the interview. A semi-structured moderator guide was developed using the above-noted frameworks [8,9,[49], [50], [51], [52]]. Supplemental Table S1 includes the interview topics, sample questions, and prior community feedback where obtained. With permission, interviews will be audio recorded with the participant's permission and then transcribed. Each participant will be mailed a $25 gift card.

We will use content analysis [55] supplemented with QSR NVivo software (version 10) to code for themes and present the results to our community advisory committee for feedback to guide development of recruitment messaging and intervention refinement before beta-testing.

We will create a content library of about 10 text messages for delivery to each index participant and family member and develop program materials describing the intervention's incentive schedule and reward scheme. Intervention delivery will be standardized via a manual for trained research staff.

2.5. Phase 2 (beta-testing)

We will recruit a sample of 10 adult dyads, each comprised of an ANAI person who smokes (index participant) and a family member (see section 2.3). All participants in the 10 dyads will receive resources and referral information on cessation treatment, family wellness, and social support. Each dyad will also receive the preliminary 6-month financial incentive intervention (Table 1) adapted using the phase 1 qualitative work. Beta-testing will enable the investigative team to obtain feedback from dyad participants after intervention exposure to ensure the program works as intended and identify any technical difficulties. After reviewing descriptive summaries of these data with the community advisory committee, we will make any needed intervention refinements before initiating the RCT.

2.6. Phase 3 (RCT)

2.6.1. Study design

Using a Hybrid Type 1 Implementation design [56], we evaluate the intervention's effectiveness and use the RE-AIM framework [57] to collect data relevant to assessing future adoption, implementation, and maintenance potential within the ATHS. The trial will utilize a two-arm, parallel groups, randomized, controlled design (see Fig. 2 for CONSORT Diagram) enrolling a new sample of dyads, each comprised of an ANAI person who smokes (index participant) and a family member (see section 2.3). Before the trial, the study statistician will generate the random allocation sequence enabling randomized dyads with 1:1 allocation to the incentive intervention or no-incentive control condition within stratified blocks based on index participant's sex (men/women), location (rural/urban), residence with family member (yes/no), and the family member's current smoking status (yes/no); all potential variables related to treatment outcomes [58,59]. Treatment condition allocation will be unknown to study staff or investigators before assignment, with participants completing baseline measures before being informed of their assignment. The treatment phase is six months. Dyad participants in both study groups will complete study measures at baseline, and 6- and 12-months post treatment, and will be mailed a $25 gift card for completion of each.

Fig. 2.

ANAI family-based financial incentive intervention for smoking cessation

CONSORT trial design.

2.6.2. Sample size calculation

Our primary outcome is continuous (prolonged) abstinence from the end of the 6-month treatment period to 12 months post treatment. Although family-level rewards could amplify intervention effects, we conservatively based our sample size calculation on three prior trials using individual incentives [[12], [13], [14]]. From these trials, we estimate 3% of our control group will continue to be abstinent from smoking at 12 months post treatment compared to 9% of the intervention group. If we randomly assign 328 dyads to each of the two study arms, the study will have 90% power with two-sided 5% significance to detect the estimated difference between study groups for the primary intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Attrition in prior studies ranged from 10% to 20% at 12 months post treatment [12,14]. Assuming 20% attrition (262 dyads per group), the study would have 82% power for mediational/secondary analyses.

2.6.3. Six-month treatment phase

Dyad participants in both study groups will receive generic, existing resources and referral information on evidence-based tobacco/nicotine cessation treatments (EBCTs), including Alaska's Tobacco Quitline, regional Tribal cessation programs, and smokefree.gov; ANTHC family wellness resources on general health topics (e.g., injury prevention, household air quality); and regional links to programs for domestic violence. Family member participants will additionally receive generic, existing evidence-based tips to support individuals who smoke in cessation [60], including quitting together as a supportive action. Providing resource and referral information is consistent with the current standard-of-care for tobacco use in the ATHS.

As in Etter and Schmid [12], smoking status check-ins among index participants in both study groups will be conducted six times during the 6-month treatment phase: weekly for the first month, then at three and six months. This incentive schedule reinforces both initial and sustained abstinence. We will obtain biochemical verification of self-reported smoking abstinence remotely using expired air carbon monoxide (CO) and salivary cotinine at each assessment among index participants. Breath CO measurement can verify abstinence within the previous 24 h and salivary cotinine, in the past 6–7 days [30]. All index participants will receive two types of test instruments: the iCO™ Smokerlyzer®, a small, portable, handheld breath CO monitor that connects to a mobile device/tablet and works through a downloaded app, and Alere™ iScreen oral fluid devices with an easy-to-use mouth swab to assess saliva cotinine [61]. Index participants perform the tests and display the results during a video call with study staff or submit pictures of themself through a secure app. In both study conditions, the index participant and family member will each receive a $25 gift card for each of the six smoking status check-ins completed by the index participant, regardless of the test results (i.e., $150 total each for the index participant and family member).

For dyads randomized to the intervention condition, the novel treatment is escalating cash rewards for the index participant achieving biochemically verified cigarette smoking abstinence at smoking status check-ins and the enrolled family member's reward of equal value (see Table 1). At each check-in, index participants will earn a cash reward with self-reported abstinence in the past 7 days and negative tests of breath CO (0–3 ppm) and saliva cotinine <30 ng/ml; or if nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), e-cigarettes, or smokeless tobacco (ST) use is reported with a positive cotinine test, the CO test is negative [30,62]. At each scheduled check-in, each dyad participant will receive a standardized text message from study staff to provide information about the test results and rewards earned (or not earned).

2.6.4. Study measures

Each dyad participant will complete online study measures three times: at baseline and at six and 12 months after the 6-month treatment phase (Table 3). Our outcomes focus on combustible cigarette smoking, based on recommendations from a Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco workgroup updating definitions and measurements of abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions [30,62]. Biochemically confirmed abstinence from smoking at each follow-up assessment will be defined as self-reported abstinence during the past seven days (not even a puff), with negative breath CO test (0–3 ppm) and negative iScreen OFD test (i.e., saliva cotinine <30 ng/ml); or if NRT, e-cigarettes/vaping, or ST use is reported with positive cotinine test, the CO test is negative [30,62]. Continuous (prolonged) abstinence, our primary outcomes, is defined as self-report of smoking abstinence from the end of the 6-month treatment period to 12 months post treatment, with biochemical verification at three times: the end of the 6-month treatment phase and at 6- and 12-months post treatment.

Table 3.

Phase 3 (RCT) dyad participant measures.

| Measures | Post-treatment follow-up |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | |

| Index participants | |||

| Socio-demographics | X | ||

| Subsistence lifestyle information | X | ||

| Cigarettes per day, time to first cigarette [63] | X | ||

| Other nicotine/tobacco product use | X | X | X |

| Household tobacco exposure [64] | X | ||

| Communal Orientation Scale [65] (interdependence, cultural mediator) | X | X | |

| Monetary Choice Questionnaire [66] (delayed discounting, behavioral economics theory-based mediator) | X | X | |

| Partner Interaction Questionnaire [67] (cessation-specific support received from enrolled family member, mediator) | X | X | |

| Self-reported cigarette smoking status (past 7 days and since last assessment) | X | X | |

| Expired breath CO (iCO Smokerlyzer) and saliva cotinine (Alere™ iScreen oral fluid test) | X | X | |

| Self-reported cessation treatment utilization | X | X | |

| Quit attempts | X | X | |

| Potential for cross-treatment contamination [68]: self-reported exposure to common components (e.g., resource materials) and unique elements (e.g., rewards for smoking abstinence) across study groups | X | X | |

| Family member participants | |||

| Socio-demographics | X | ||

| Type of relationship with index participant and perceived closeness [69] | X | ||

| Partner Interaction Questionnaire [67] (cessation-specific support provided to index participant) | X | X | X |

| Self-reported cigarette smoking status, nicotine/tobacco product use (past 7 days and since last assessment) | X | X | X |

| Self-reported cessation treatment utilization | X | X | |

2.6.5. Implementation process measures

We will use mixed methods to explore RE-AIM process indicators relevant to program reach, adoption, implementation, and setting-level maintenance (Table 4). To evaluate the overall reach and representativeness of participants and intervention effectiveness, we will utilize quantitative data collected in the RCT. To explore factors relevant to future widespread dissemination, we will invite 12 index participants and 12 family members from the intervention group to participate in a semi-structured, individual phone interview at the study end. Individuals will be purposefully sampled to maximize diversity in sex, rural/urban, and intervention “dose” completed. To explore factors relevant to adoption, implementation, and maintenance, we will also conduct interviews with 12 ATHS stakeholders, first inviting the same stakeholders who participated in Phase 1 then recruiting additional stakeholders if needed. We will adapt interview questions from the RE-AIM planning literature [70] and track program delivery costs, thereby identifying implementation barriers and facilitators and support plans for future adaptation and dissemination of the intervention to adopting organizations.

Table 4.

Phase 3 (RCT) implementation process measures and data sources.

| RE-AIM OUTCOMES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reach |

|

Advertising; screening and enrollment records; Alaska state tobacco surveys, e.g., BRFSS [1], & census data [38] |

| Effectiveness | Biochemically verified smoking abstinence at 6- and 12-months post treatment. Primary outcome: prolonged abstinence at 12 months post treatment. | See section 2.6.4 |

| Adoption | Descriptive information from potential future adopting settings (Tribal Health Organization #, type, size) | Semi-structured interviews conducted at the end of the study |

| Implementation (fidelity) |

|

Intervention process data; baseline and follow-up measures; research team meeting minutes; program tracking records; interviews |

| Potential maintenance |

|

Semi-structured interviews conducted at the end of the study |

| COST-EFFECTIVENESS | ||

| Potential return on investment |

|

Program tracking records; data/models from the literature [71] on estimated reduction in annual health care costs for cessation |

2.6.6. Statistical methods

We will quantitatively describe potential and actual reach and use quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate implementation fidelity (Table 4). To understand the success of recruitment strategies, we will summarize and compare the numbers screened, eligible, and enrolled by rural/urban location and Alaska region; and compare social media to other advertisements using the chi-square/analysis of variance/Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. We will examine baseline demographics of dyad participants to determine any significant differences between intervention and control groups using the chi-square test (categorical variables) and the two-sample t-test/rank-sum test (continuous variables). Outcome criteria will include comparing the percentage of dyad participants completing the 12-month post-treatment measures (i.e., retention) and the proportion of index participants completing all six smoking status check-ins during the 6-month treatment phase (fidelity) between groups using the chi-square test. We will compare time to drop out between study groups using Cox proportional hazards regression and explore differences in the proportion of index participants completing all six smoking status assessments by the stratification factors (index participant's sex, rural/urban location, residence in the same household; and family member's smoking status) using chi square.

To evaluate effectiveness, we will summarize the primary outcome of biochemically confirmed continuous (prolonged) smoking abstinence rate among the index participants for each study group (point estimate and 95% CI) and compare the rates between conditions using logistic regression. Using an ITT approach, participants lost to follow-up or lack biochemical confirmation will be classified as smoking. We will use logistic regression to examine condition differences on secondary outcomes: point prevalence smoking abstinence rates, self-reported EBCT utilization, and self-reported abstinence from all nicotine/tobacco product use among the index participants. We will include stratification factors in the model for all regressions to control for their effects and additionally incorporate baseline variables that differ significantly between groups, use of EBCT, change in enrolled family member, and any observed cross-treatment contamination effects. To assess mediation (e.g., Communal Orientation Scale), we will follow procedures suggested by MacKinnon [72], fitting three regression models to the data. Using logistic regression, an exploratory analysis will examine potential treatment effects among enrolled family members by current smoking at baseline (yes/no).

We will analyze qualitative interview data for themes related to future adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the intervention using content analysis [55] supplemented with QSR NVivo software, including coding for barriers, facilitators, priorities, and feasibility.

Return on investment will assess cost-effectiveness. We will evaluate program delivery costs, including gift cards and incentives/rewards, and staff time for intervention implementation on a per-person basis. Because duration of follow-up (one year) will be insufficient to measure differences in smoking-related healthcare costs between the intervention and control groups, annual per-person healthcare costs associated with smoking abstinence will be estimated from the literature [1,71,73,74]. We will apply these cost data and the difference in abstinence rates between study groups to estimate the net cost savings from implementing the proposed intervention [75]. The estimates will be projected to the larger ANAI population size and extended time frame in the short to mid-term, incorporating sensitivity analyses on cost savings for a change in smoking abstinence rates [74,75].

3. Results

Over four years, the ANAI community advisory committee provided input on our study idea, design, and methods, particularly emphasizing the involvement of families. Members also contributed to the intervention components (e.g., types of family-level rewards), the definition of family, family member selection and inclusion criteria, and recruitment messaging (see Supplemental Table S1). Importantly, we iteratively refined aspects of the study to incorporate this feedback and repeatedly shared with committee members how their feedback was used to revise the study methods.

4. Discussion

This study addresses a need identified by ATHS leaders for novel, accessible, and effective smoking cessation interventions. This trial is the first incentive intervention for commercial smoking cessation among Indigenous people. Our study aligns with the strength and value ANAI people place on family. Findings, processes, and resources will inform how Indigenous families can support smoking cessation within incentive interventions.

Study strengths are the participatory approach, formative work to culturally tailor and adapt the intervention, and virtual delivery of the intervention and study procedures. Including process indicators to inform future intervention adoption, implementation, and maintenance, as well as the cost analysis, will identify strategies for future dissemination. Our study will contribute knowledge to the field on the importance of the family member's smoking status on cessation outcomes.

Study limitations are the RCT is not designed to evaluate the effectiveness of individual versus family-level financial incentives or distinguish between familial social support and family-level incentives. However, prior studies confirm individual and group-based incentive programs are equally effective [13,21], and a family approach aligns with ANAI cultural values-important considerations for future acceptance and adoption. The study is limited to adults aged 21 and older but we plan to expand the inclusion of other age groups in future work. While our sample is restricted to ANAI people in Alaska, the intervention has potential for application to other Indigenous communities aiming to focus on commercial tobacco use.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01 DA046008]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Unrelated to this project, Dr. Prochaska has provided consultation to pharmaceutical and technology companies that make medications and other treatments for quitting smoking. Dr. Prochaska also has served as an expert witness in lawsuits against tobacco companies. The authors reported no other potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the ANTHC Research Consultation Committee for guiding the development of this study. We also appreciate the contributions of Selma Oskolkoff-Simon, Fiona Brosnan, and Michael Doyle in ANTHC Marketing and Communication. We appreciate the helpful guidance from Dana Diehl, Debbie Demientieff, and Ingrid Stevens in the ANTHC Wellness and Prevention Department on participant family wellness materials and research staff training. We thank Crystal Meade at ANTHC for assistance with cessation treatment resource materials and Kimberly Kinnoin at Mayo Clinic for manuscript assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101129.

Contributor Information

Christi A. Patten, Email: patten.christi@mayo.edu.

Kathryn R. Koller, Email: kkoller@anthc.org.

Diane K. King, Email: dkking@alaska.edu.

Judith J. Prochaska, Email: jpro@stanford.edu.

Pamela S. Sinicrope, Email: sinicrope.pamela@mayo.edu.

Michael G. McDonell, Email: mmcdonell@wsu.edu.

Paul A. Decker, Email: decker.paul@mayo.edu.

Flora R. Lee, Email: frlee@anthc.org.

Janessa K. Fosi, Email: jkfosi@anthc.org.

Antonia M. Young, Email: young.antonia@mayo.edu.

Corinna V. Sabaque, Email: sabaque.corinna@mayo.edu.

Ashley R. Brown, Email: Brown.Ashley@mayo.edu.

Bijan J. Borah, Email: borah.bijan@mayo.edu.

Timothy K. Thomas, Email: tkthomas@anthc.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Alaska Department of Health and Social Services (AKDHSS) 2019. Division of public health. Section of chronic disease prevention and health promotion, Alaska tobacco facts-2019 update.http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Chronic/Documents/Tobacco/PDF/2019_AKTobaccoFacts.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renner C.C., Patten C.A., Enoch C., Petraitis J., Offord K.P., Angstman S., et al. Focus groups of Y-K Delta Alaska Natives: attitudes toward tobacco use and tobacco dependence interventions. Prev. Med. 2004;38(4):421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patten C.A., Fadahunsi O., Hanza M.M., Smith C.A., Decker P.A., Boyer R., et al. Tobacco cessation treatment for Alaska Native adolescents: group randomized pilot trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16(6):836–845. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koller K.R., Flanagan C.A., Day G.E., Thomas T.K., Smith C.A., Wolfe A.W., et al. Developing a biomarker feedback intervention to motivate smoking cessation during pregnancy: phase II MAW study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017;19(8):930–936. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mowery P.D., Dube S.R., Thorne S.L., Garrett B.E., Homa D.M., Nez Henderson P. Disparities in smoking-related mortality among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015;49(5):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nash S.H., Day G., Zimpelman G., Hiratsuka V.Y., Koller K.R. Cancer incidence and associations with known risk and protective factors: the Alaska EARTH study. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(10):1067–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notley C., Gentry S., Livingstone-Banks J., Bauld L., Perera R., Hartmann-Boyce J. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004307.pub6. CD004307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bickel W.K., Jarmolowicz D.P., Mueller E.T., Gatchalian K.M. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 2011;13(5):406–415. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Linden S. The future of behavioral insights: on the importance of socially situated nudges. Behavioural Public Policy. 2018;2(2):207–217. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2018.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladapo J.A., Prochaska J.J. Paying smokers to quit: does it work? Should we do it? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;68(8):786–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critchfield T.S., Kollins S.H. Temporal discounting: basic research and the analysis of socially important behavior. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2001;34(1):101–122. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etter J.F., Schmid F. Effects of large financial incentives for long-term smoking cessation: a randomized trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;68(8):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpern S.D., French B., Small D.S., Saulsgiver K., Harhay M.O., Audrain-McGovern J., et al. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372(22):2108–2117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volpp K.G., Troxel A.B., Pauly M.V., Glick H.A., Puig A., Asch D.A., et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurti A.N., Nighbor T.D., Tang K., Bolivar H.A., Evemy C.G., Skelly J., et al. Effect of smartphone-based financial incentives on peripartum smoking among pregnant individuals: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonell M.G., Hirchak K.A., Herron J., Lyons A.J., Alcover K.C., Shaw J., et al. Effect of incentives for alcohol abstinence in partnership with 3 American Indian and Alaska Native communities: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2021;78(6):599–606. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholz U., Stadler G., Ochsner S., Rackow P., Hornung R., Knoll N. Examining the relationship between daily changes in support and smoking around a self-set quit date. Health Psychol. 2016;35(5):514–517. doi: 10.1037/hea0000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas D.P., Davey M.E., van der Sterren A.E., Lyons L., Hunt J.M., Bennet P.T. Social networks and quitting in a national cohort of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019;38(1):82–91. doi: 10.1111/dar.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Brand F.A., Candel M., Nagelhout G.E., Winkens B., van Schayck C.P. How financial incentives increase smoking cessation: a two-level path analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021;23(1):99–106. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen X., Eiden R.D., Justicia-Linde F.E., Wang Y., Higgins S.T., Thor N., et al. A multicomponent behavioral intervention for smoking cessation during pregnancy: a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design. Translational behavioral medicine. 2019;9(2):308–318. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White J.S. Social and monetary incentives for smoking cessation at large employers (SMILE) clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02421224 2018 NCT02421224. (First received 20 April 2015),. Available at:

- 22.Patten C.A., Lando H.A., Desnoyers C.A., Barrows Y., Klejka J., Decker P.A., et al. The Healthy Pregnancies Project: study protocol and baseline characteristics for a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a community intervention to reduce tobacco use among Alaska Native pregnant women. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2019;78:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirchak K.A., Leickly E., Herron J., Shaw J., Skalisky J., Dirks L.G., et al. Focus groups to increase the cultural acceptability of a contingency management intervention for American Indian and Alaska Native communities. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2018;90:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.G.V. Mohatt, G.W. McDiarmid, V.C. Montoya, in: S.M. Manson, N.G. Dinges (Eds.), Behavioral Health Issues Among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Explorations on the Frontiers of the Biobehavioral Sciences, American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, Monograph No. 12000, pp. 325–365.

- 25.Begg C., Cho M., Eastwood S., Horton R., Moher D., Olkin I., et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee K., Smith J., Thompson S. Engaging Indigenous peoples in research on commercial tobacco control: a scoping review, AlterNative. An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 2020;16(4):332–355. doi: 10.1177/1177180120970941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillard D.A., Caindec K., Dirks L.G., Hiratsuka V.Y. Challenges in engaging and disseminating health research results among Alaska Native and American Indian people in Southcentral Alaska. Am. Indian Alaska Native Ment. Health Res. 2018;25(1):3–18. doi: 10.5820/aian.2501.2018.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes J.R., Keely J., Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romanowich P., Lamb R.J. The relationship between in-treatment abstinence and post-treatment abstinence in a smoking cessation treatment. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(1):32–36. doi: 10.1037/a0018520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benowitz N.L., Bernert J.T., Foulds J., Hecht S.S., Jacob P., Jarvis M.J., et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and abstinence: 2019 update. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22(7):1086–1097. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cropsey K.L., Trent L.R., Clark C.B., Stevens E.N., Lahti A.C., Hendricks P.S. How low should you go? Determining the optimal cutoff for exhaled carbon monoxide to confirm smoking abstinence when using cotinine as reference. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16(10):1348–1355. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins K.A., Karelitz J.L., Jao N.C. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15(5):978–982. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roll J.M., Higgins S.T., Badger G.J. An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1996;29(4):495–504. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495. quiz 504-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried N. 2019. The cost of living; 2018 and early 2019.https://live.laborstats.alaska.gov/col/col.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lussier J.P., Heil S.H., Mongeon J.A., Badger G.J., Higgins S.T. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connolly T., Butler D. Regret in economic and psychological theories of choice. J. Behav. Decis. Making. 2006;19(2):139–154. doi: 10.1002/bdm.510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fast P. In: Alaska at 50: the Past, Present, and Future of Alaska Statehood. Kumura G.W., editor. University of Alaska Press; Fairbanks, AK: 2010. Alaska at 50: language, tradition, and art; pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Census Bureau . 2019. Quickfacts Alaska. Population estimates.https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/AK Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benowitz N.L., Renner C.C., Lanier A.P., Tyndale R.F., Hatsukami D.K., Lindgren B., et al. Exposure to nicotine and carcinogens among Southwestern Alaskan Native cigarette smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(6):934–942. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) 2004. Substance Abuse treatment and family therapy (Chapter 1)https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64269/ Available at: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubbard G., Gorely T., Ozakinci G., Polson R., Forbat L. A systematic review and narrative summary of family-based smoking cessation interventions to help adults quit smoking. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016;17:73. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyers R.J., Roozen H.G., Smith J.E. The community reinforcement approach: an update of the evidence. Alcohol Res. Health. 2011;33(4):380–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldwell J.Y., Davis J.D., Du Bois B., Echo-Hawk H., Erickson J.S., Goins R.T., et al. Culturally competent research with American Indians and Alaska Natives: findings and recommendations of the first symposium of the work group on American Indian Research and Program Evaluation Methodology. Am. Indian Alaska Native Ment. Health Res. 2005;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.5820/aian.1201.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patten C.A., Boyle R., Tinkelman D., Brockman T.A., Lukowski A., Decker P.A., et al. Linking smokers to a quitline: randomized controlled effectiveness trial of a support person intervention that targets non-smokers. Health Educ. Res. 2017;32(4):318–331. doi: 10.1093/her/cyx050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruden D., Bruce M.G., Wenger J.D., Hurlburt D.A., Bulkow L.R., Hennessy T.W. Migration of persons between households in rural Alaska: considerations for study design. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2013;72 doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.2020. National coalition against domestic violence, domestic violence in Alaska.https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/ncadv_alaska_fact_sheet_2020.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faseru B., Richter K.P., Scheuermann T.S., Park E.W. Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002928.pub4. CD002928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindsay R.P., Tsoh J.Y., Sung H.Y., Max W. Secondhand smoke exposure and serum cotinine levels among current smokers in the USA. Tobac. Control. 2016;25(2):224–231. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis R.E., Resnicow K. In: Health Communication Message Design: Theory and Practice. Cho H., editor. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2012. The cultural variance framework for tailoring health messages; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Resnicow K., Braithwaite R.L. In: Health Issues in the Black Community. Braithwaite R.L., Taylor S.E., editors. Jossey-Bass Inc.; San Francisco, CA: 2001. Cultural sensitivity in public health; pp. 516–542. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research . 2022. The consolidated framework for implementation research – technical assistance for users of the CFIR framework.https://cfirguide.org/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Namey E., Guest G., McKenna K., Chen M. Evaluating bang for the buck: a cost-effectiveness comparison between individual interviews and focus groups based on thematic saturation levels. Am. J. Eval. 2016;37(3):425–440. doi: 10.1177/1098214016630406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patton M.Q. fourth ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Therory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krippendorff K.H. fourth ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2018. Content Analysis: an Introduction to its Methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Curran G.M., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne J.M., Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glasgow R.E., Harden S.M., Gaglio B., Rabin B., Smith M.L., Porter G.C., et al. RE-AIM Planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front. Public Health. 2019;7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Dios M.A., Stanton C.A., Cano M.A., Lloyd-Richardson E., Niaura R. The influence of social support on smoking cessation treatment adherence among HIV+ smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;18(5):1126–1133. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith P.H., Bessette A.J., Weinberger A.H., Sheffer C.E., McKee S.A. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: a review. Prev. Med. 2016;92:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Helping others quit: for loved ones. 2020. Available at: https://smokefree.gov/help-others-quit/loved-ones.

- 61.Moore M.R., Mason M.J., Brown A.R., Garcia C.M., Seibers A.D., Stephens C.J. Remote biochemical verification of tobacco use: reducing costs and improving methodological rigor with mailed oral cotinine swabs. Addict. Behav. 2018;87:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piper M.E., Bullen C., Krishnan-Sarin S., Rigotti N.A., Steinberg M.L., Streck J.M., et al. Defining and measuring abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions: an updated review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22(7):1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fagerstrom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012;14(1):75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biener L., Hamilton W.L., Siegel M., Sullivan E.M. Individual, social-normative, and policy predictors of smoking cessation: a multilevel longitudinal analysis. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2010;100(3):547–554. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark M.S., Ouellette R., Powell M.C., Milberg S. Recipient's mood, relationship type, and helping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987;53(1):94–103. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kirby K.N., Petry N.M., Bickel W.K. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1999;128(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen S., Lichtenstein E. Partner behaviors that support quitting smoking. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990;58(3):304–309. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simmons N., Donnell D., Ou S.S., Celentano D.D., Aramrattana A., Davis-Vogel A., et al. Assessment of contamination and misclassification biases in a randomized controlled trial of a social network peer education intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors among drug users and risk partners in Philadelphia, PA and Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1818–1827. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gachter S., Starmer C., Tufano F. Measuring the closeness of relationships: a comprehensive evaluation of the 'Inclusion of the Other in the Self' scale. PLoS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Balis L.E., John D.H., Harden S.M. Beyond Evaluation: using the RE-AIM framework for program planning in extension. J. Ext. 2019;57(2) http://www.re-aim.org/resources-and-tools/.RE-AIM key questions and tips for improving AIM performance 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 1997-2001. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2005;54(25):625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.MacKinnon D.P., Fairchild A.J., Fritz M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Max W. The financial impact of smoking on health-related costs: a review of the literature. Am. J. Health Promot. 2001;15(5):321–331. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nolan M.B., Borah B.J., Moriarty J.P., Warner D.O. Association between smoking cessation and post-hospitalization healthcare costs: a matched cohort analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19(1):924. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sung H.Y., Penko J., Cummins S.E., Max W., Zhu S.H., Bibbins-Domingo K., et al. Economic impact of financial incentives and mailing nicotine patches to help Medicaid smokers quit smoking: a cost-benefit analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018;55(6 Suppl 2):S148–S158. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.