Abstract

Objective

Prospective registration has been widely implemented and accepted as a best practice in clinical research, but retrospective registration is still commonly found. We assessed to what extent retrospective registration is reported transparently in journal publications and investigated factors associated with transparent reporting.

Design

We used a dataset of trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov or Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien, with a German University Medical Center as the lead centre, completed in 2009–2017, and with a corresponding peer-reviewed results publication. We extracted all registration statements from results publications of retrospectively registered trials and assessed whether they mention or justify the retrospective registration. We analysed associations of retrospective registration and reporting thereof with registration number reporting, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) membership/-following and industry sponsorship using χ2 or Fisher exact test.

Results

In the dataset of 1927 trials with a corresponding results publication, 956 (53.7%) were retrospectively registered. Of those, 2.2% (21) explicitly report the retrospective registration in the abstract and 3.5% (33) in the full text. In 2.1% (20) of publications, authors provide an explanation for the retrospective registration in the full text. Registration numbers were significantly underreported in abstracts of retrospectively registered trials compared with prospectively registered trials. Publications in ICMJE member journals did not have statistically significantly higher rates of both prospective registration and disclosure of retrospective registration, and publications in journals claiming to follow ICMJE recommendations showed statistically significantly lower rates compared with non-ICMJE-following journals. Industry sponsorship of trials was significantly associated with higher rates of prospective registration, but not with transparent registration reporting.

Conclusions

Contrary to ICMJE guidance, retrospective registration is disclosed and explained only in a small number of retrospectively registered studies. Disclosure of the retrospective nature of the registration would require a brief statement in the manuscript and could be easily implemented by journals.

Keywords: Medical ethics, Statistics & research methods, Clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We use a large, high-quality dataset of all trials conducted at German university medical centres over a period of 9 years (2009–2017) and registered in two registries, with results publications determined by an extensive manual screening process.

This study only includes trials led by German university medical centres, which might limit its generalisability to other regions. Follow-up for trial publications ends uniformly in 2020, meaning that older trials had longer follow-up for publication than newer trials in the dataset.

Introduction

Prospective registration of clinical trials (ie, registration before enrolment of the first participant) is an important practice to reduce biases in their conduct and reporting.1 A number of ethical and legal documents call for prospective registration: The Declaration of Helsinki2 and the WHO registry standards3 state that prospective registration and results reporting of clinical trials are an ethical responsibility. European law, for example, explicitly, mandates prospective registration of pharmaceutical trials.4 In addition, many journals, via the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), encourage or require prospective registration with an appropriate registry before the first participant is enrolled for all trials they publish, as well as the reporting of trial registration numbers (TRNs) in publications for better findability.5 6 Similarly, reporting guidelines such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials7 and Good Publication Practice 38 recommend the reporting of TRNs.

Prospective registration has been widely implemented and advocated for many reasons: to detect and mitigate publication bias (ie, the non-reporting of studies, or aspects of studies, that did not yield a positive result) and selective reporting (ie, the selective reporting of only statistically significant primary outcomes). Prospective registration allows for public scrutiny of trials, identification of research gaps and to support the coordination of efforts by preventing unnecessary duplication.9 When trials are registered retrospectively, that is, their registry entry is created after study start, this undermines many of the reasons for registration. While prospective registration has increased over the past decade, retrospective registration is still widespread.10–14 Some registries, such as Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien (DRKS) or the WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, explicitly mark retrospectively registered entries as such, whereas others, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, do not. While some journal editors allow retrospectively registered trials to be published, others do not. Journals following ICMJE guidance should in principle mandate prospective registration, but this principle is not always enforced.12 15 16 According to ICMJE guidance, journals should publish retrospectively registered studies only in exceptional cases, noting that ‘authors should indicate in the publication when registration was completed and why it was delayed. Editors should publish a statement indicating why an exception was allowed’.5 This was investigated by previous studies which found that such reporting rarely happens.17 18

Our study aims to investigate the conduct of retrospective registration and its transparent reporting in a larger sample. In a previous study in a cohort of 1509 trials conducted at German university medical centers (UMC), registered in DRKS or ClinicalTrials.gov, and reported as complete between 2009 and 2013, 75% were registered retrospectively.19 This rate dropped to 46% for the 1658 trials completed between 2014 and 2017.20 Using the data from these two studies on trials registered in two large registries, led by German UMCs, completed between 2009 and 2017 and with at least one available peer-reviewed results publication,19 20 we investigate whether and how authors report retrospective registration in the results publication. We also explore how retrospective registration is associated with other practices such as TRN reporting.

Methods

Data sources and sample

We based our sample on two related projects that were conducted at our research group.19 20 The projects have drawn a full sample (n=3113) of registry entries for interventional studies reported as complete between 2009 and 2017, led by a German UMC and registered in one of two registries: DRKS, which is the WHO primary trial registry for Germany, and ClinicalTrials.gov, which is also routinely used in Germany to register clinical research and accepted by the ICMJE. Our dataset also includes the earliest results publications found for 68.4% (2129/3113) of the trials, which were manually identified in different stages until 1 September 2020. We retrieved the combined data from the two projects from a GitHub repository (https://github.com/maia-sh/intovalue-data, accessed on 22 February 2022). The final dataset is publicly available.21

Eligibility criteria

We included any trial that (1) was registered as an interventional study in either the ClinicalTrials.gov or the DRKS database, (2) was completed between 2009 and 2017, (3) reports a German UMC listed as the responsible party or lead sponsor, or with a principal investigator from a German UMC and (4) has published results in a peer-reviewed journal. Detailed descriptions of how these variables were derived are provided in the original publications of the dataset.19 20 Retrospective registration was determined based on the registration and study start dates in the registry entries: dates were set to the first of the respective month and studies with a registration date more than 1 month after start date counted as retrospectively registered. For trials that were registered in both registries, we kept the entry that was created earlier.

Data extraction

For all retrospectively registered trials, we manually searched the abstract and the full text of the publications, including editorial statements, whether they reported:

The fact that the study was registered (binary).

A TRN (binary).

The exact wording used to report the registration, including any provided registration numbers (free text).

The date of the retrospective registration (binary).

The fact that the study was retrospectively registered (binary).

We also assessed whether (binary) and how authors justified or explained the retrospective registration (free text).

One rater (MH) used the keywords ‘regist’, ‘nct’, ‘drks’, ‘eudra’, ‘retro’, ‘delay’ and ‘after’ to search for registration numbers and wording pointing to retrospective registration in all publications. We considered a retrospective registration statement transparent if the authors explicitly mentioned that the registration was retrospective, for example, ‘this study was retrospectively registered in (registry), (TRN)’. Reporting of the registration date alone was not considered as transparent reporting of retrospective registration, except if the date of registration was mentioned in combination with the study start date in the same paragraph.

ICMJE journals

We created additional variables for whether journals are ICMJE members or follow the ICMJE recommendations.22

Cross-registrations

We classified all retrospectively registered studies in our sample that also report a registration in EudraCT in the publication as prospective, as registrations on the platform are required prior to the approval of regulatory agencies or research ethics committees.4

Reliability assessment of ratings

To assess the reliability of the data extraction, another rater (SG) performed 3 validation steps: first, a sample of 100 publications was screened using the same extraction form, during the main screening to refine category definitions. Second, another sample of 100 publications for which no registration number reporting was noted by MH to check for false negative ratings. Third, all cases with either date or reporting of retrospective registration or justification were screened to check for false positives.

Analyses

Associations between prospective registration and other variables

To test the strength of the associations between prospective registration and three variables, we used Pearson’s χ2 independence test. These variables were: (1) publication in an ICMJE member journal or a journal following ICMJE recommendations, (2) reporting of a registration number and (3) industry funding.

Associations between reporting of retrospective registration and other variables

To test the strength of the associations between the reporting of retrospective registration and two binary variables, we used Fisher’s exact test, as case numbers were low. These variables are: (1) publication in an ICMJE member journal or a journal following ICMJE recommendations and (2) industry funding.

Software

We used Microsoft Excel for data collection and R (V.4.0.3) for data analysis and visualisation.

Reporting

We checked our manuscript against the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist (online supplemental table 1).23

bmjopen-2022-069553supp001.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Sample of retrospectively registered trials

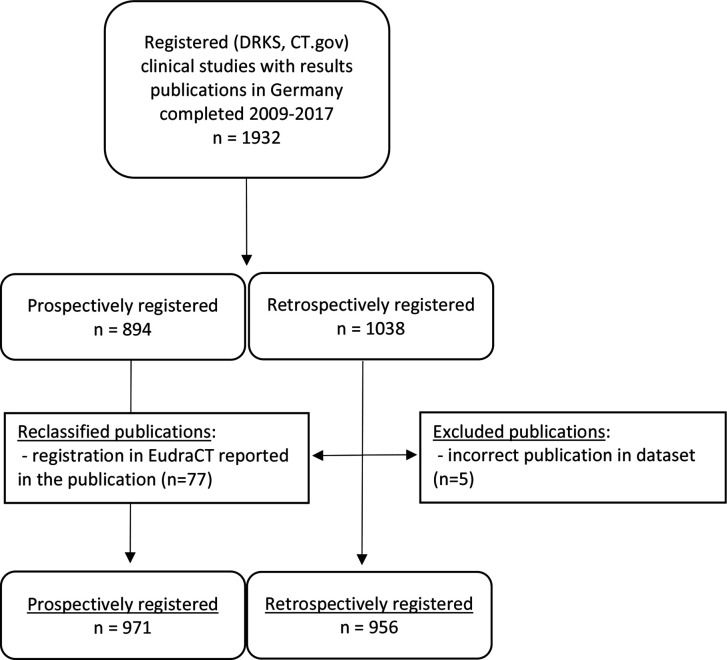

After applying the above-mentioned exclusion criteria, 1932 registered studies with an associated results publication remained. Of these, 1038 (54%) were retrospectively registered according to the information provided in ClinicalTrials.gov and DRKS. We screened these 1038 studies for our analysis. Five of the publications were excluded as they were mislabeled as results publications in the dataset. Another 77 (8%) of the publications provided a EudraCT number, in which case we reclassified the study as prospectively registered, leaving 956 studies. For statistical comparisons, we used the studies classified as prospectively registered (n=971) in the dataset as a control group. A flowchart of this study selection is provided in figure 1. Basic characteristics of included trials are available in online supplemental table 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion/exclusion of studies. From the 1038 trials that were retrospectively registered in Clincialtrials.gov (CT.gov) or Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien (DRKS), we excluded 5 publications that clearly did not report clinical study results (eg, secondary analyses of CT data) and another 77 that reported EudraCT entries in the publications, resulting in 956 retrospectively registered studies from a total dataset of 1927 (971+956) studies.

bmjopen-2022-069553supp002.pdf (36.4KB, pdf)

Retrospective registration

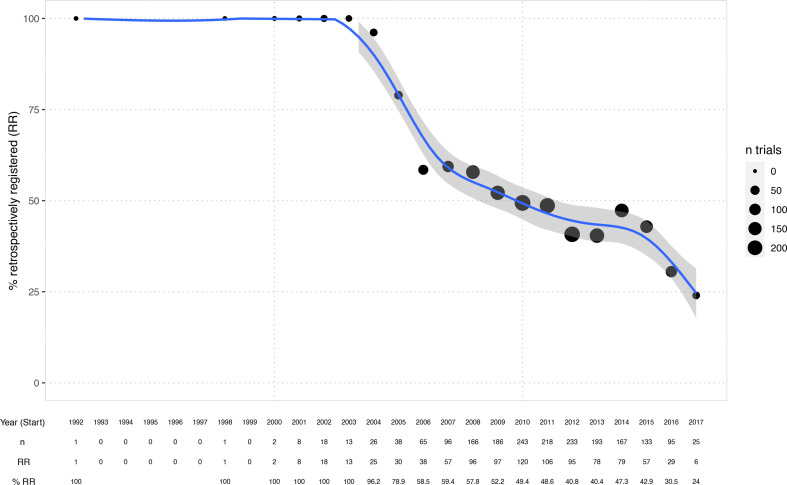

Figure 2 shows the extent of retrospective registration over time, which has been falling steadily from 100% in 2004 to 25% in 2017.

Figure 2.

Percentage of retrospectively registered (RR) trials over time (per study start year). Generalised additive model smoother laid over (blue) with 95% CI. Bubble sizes indicate the number of trials per year included in the dataset.

We describe associations between prospective registration and previously defined binary variables in table 1. We found no statistically significant association between publication in ICMJE member journals and prospective registration (p=0.10). Similarly, we found no statistically significant association with prospective registration when also including publication in journals reporting to follow ICMJE recommendations (p=0.47). It is important to note here that the information on ICMJE-following is based on journals’ requests to be included on the ICMJE website as a journal following the ICMJE’s recommendations,22 therefore our results suggest that journals requesting to be listed on the site often do not enforce the recommendations strongly. However, there are other journals, such as many PLOS journals, that are not featured on the ICMJE site, but implement the recommendations. Retrospectively registered trials, compared with prospectively registered trials, significantly underreported registration numbers in the abstract (p=0.0007). Industry sponsorship of trials was associated with prospective registration (p=0.002). In 31% (294/956) of trials, registration occurred between study completion and publication (median 370 days before publication). Another 3% (25/956) of trials were registered after publication (median 249 days after publication).

Table 1.

Associations between prospective registration and other variables

| Variable (yes/no) | n (%) prospectively registered | P value (χ2) | |

| ICMJE member journal | Y | 28 (63.6%) | p=0.10 |

| N | 943 (50.1%) | ||

| ICMJE member/following journal | Y | 329 (49.2%) | p=0.47 |

| N | 642 (51.0%) | ||

| TRN reporting in abstract | Y | 404 (55.4%) | p=0.0007 |

| N | 567 (47.3%) | ||

| Industry sponsorship | Y | 163 (59.3%) | p=0.002 |

| N | 808 (48.9%) |

ICMJE, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; TRN, trial registration number.

Reporting of registration

Table 2 summarises the prevalence of reporting of trial registration and the reporting of retrospective registration. In 82% (783/956) of the remaining results publications of retrospectively registered trials, the registration was explicitly reported in either the abstract or the full text. In all except four of these publications, the registration was mentioned by providing the registration number. In the other cases, the registration was mentioned but without reporting a registration number.

Table 2.

Number of retrospectively registered trials and prevalence of key retrospective registration reporting practices

| n | % (of total) | |

| Total: retrospectively registered trials | 956 | 100.0% |

| Registration reported | 783 | 81.9% |

| Registration number reported | 779 | 81.5% |

| In abstract | 325 | 34.0% |

| In full text | 535 | 56.0% |

| In other* | 134 | 14.0% |

| Registration date reported | 67 | 7.0% |

| In abstract | 45 | 4.7% |

| In full text | 32 | 3.3% |

| Retrospective registration addressed | 47 | 4.9% |

| In abstract | 21 | 2.2% |

| In full text | 33 | 3.5% |

| Retrospective registration justified/explained | 20 | 2.1% |

| In abstract | 0 | 0.0% |

| In full text | 20 | 2.1% |

*‘Other’ includes footnotes, sidebars, etc.

Reporting of retrospective registration

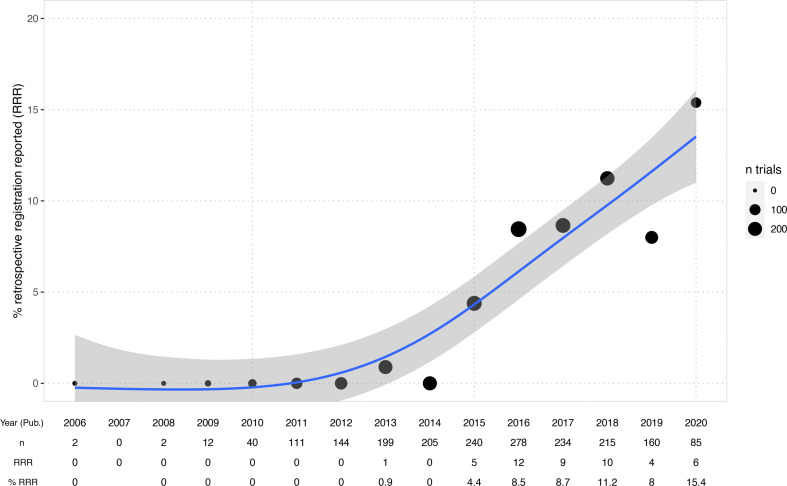

The rate of trials for which retrospective registration is reported transparently increased over the last years up to 15% in 2020 (figure 3). Overall, among all 956 retrospectively registered clinical studies, 5% (47) mention explicitly that this registration was retrospective in the abstract or full text (see table 2). Among those cases, 20 give some explanation or justification for why registration was retrospective. In 7% (67) of cases, the authors reported the registration date alongside the registration statement, but in 35 of those, the date was provided without giving the necessary context that the registration was retrospective.

Figure 3.

Percentage of retrospectively registered trials reporting retrospective registration transparently in the publication over time (per study publication year). Generalised additive model smoother laid over (blue) with 95% CI. Bubble sizes indicate the number of trials per year included in the dataset. Starting in 2013, some authors begin to report retrospective registration. 15% of publications of retrospectively registered trials from 2020 transparently report retrospective registration. Four trials were published before 2009—in all those cases, the study completion dates provided in the registry were after 2009. Study start dates were before 2005 and studies were registered in 2005 (3/4) or later (1/4).

Publications in ICMJE member journals did not have a statistically significantly higher rate of reporting of retrospective registration (13% vs 5%, p=0.18), whereas publications in ICMJE member or following journals had a significantly lower rate (2% vs 7%, p=0.004). We found no association with transparent reporting of retrospective registration for industry sponsored trials (2% vs 5%, p=0.16) (table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between transparent reporting of retrospective registration and other variables

| Variable (yes/no) | n (%) reporting RR | P value (Fisher test) | |

| ICMJE member journal | Y | 2 (12.5%) | p=0.18 |

| N | 45 (4.8%) | ||

| ICMJE member/following journal | Y | 7 (2.1%) | p=0.004 |

| N | 40 (6.5%) | ||

| Industry sponsorship | Y | 2 (1.8%) | p=0.16 |

| N | 45 (5.3%) |

ICMJE, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Justifications of retrospective registration

In 20 cases in which the retrospective nature of the registration was reported, the authors provided further information explaining or justifying the retrospective registration. Notably, 14 of the 20 studies (70%) that justified the retrospective registration were published in a single journal, PLOS ONE. Table 4 shows the main themes present in authors’ explanations, with text examples.

Table 4.

Main themes identified from authors’ explanations of retrospective reporting and example statements

| Theme | Example(s) |

| Unawareness of registration policy | At the time when the trial was started, the initiators of this study were unfortunately unaware of the policy of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), which requires prospective registration of all interventional clinical trials. As soon as we became aware of this policy, we registered the trial. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146678) The reason for retrospectively registering the study was that the study authors were not aware of the recommendation to register diagnostic accuracy studies before this date. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199345) |

| Delays by the registry | Registration of the study was applied for in April 2015. All queries from the DRKS were answered until the 31st August 2015 except the planned inclusion date of the first patient (first-patient-in), which was correct in the DRKS registry on 1st December 2015. Confirmation of registration occurred on 4th December 2015. The first patient was recruited and randomized into the study on 20th October 2015. Until 4th December 2015 eight patients were randomized into the trial. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229898) |

| Not obligatory at the time | At the time of submission of the study protocol, the Ethics Committee did not require registration for feasibility or proof of concept studies. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02196545) in July 2014 in preparation of a manuscript for publication of the data. The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this intervention are registered. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121478) It was not registered at a clinical trial register, because at the time of setup in 2003, such a registration was not obligatory. (doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010133) |

| Not obligatory for the intervention | According to national laws it is stipulated to inform the respective ethics committee, but it was not necessary to register the study in an official registry or to obtain an ethics committee vote, because it was an expanded access study (Heilversuch). Despite this, we prospectively obtained a vote of the ethics committee. Study design and patient information form were approved by the local ethics committee (ethics committee of the regional medical association; approval no. EK-BR-50/10–1, date of approval December 10th, 2010). In addition, the study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (ID no. NCT02168790). (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125035) |

| Miscommunication between investigators | The time of first registration was June 17, 2013, and final approved trial registration was July 1, 2013. First patient inclusion was in July 2012 at the Heart Center Leipzig University Hospital, Leipzig, Germany. Thus, there was a delay between first patient inclusion and trial registration that was the result of a misunderstanding between the principal investigator of the trial, Dr Thiele, and the first author, Dr Fuernau, who was responsible for clinical project coordination at the investigator’s site at the Heart Center Leipzig University of Leipzig. According to initial communication, registration had to be performed by Dr Fuernau. When the study principal investigator recognized that it had not been performed, we immediately registered the trial at http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov. At this time, only 7 patients at the Heart Center Leipzig University Hospital had been included in the trial. (doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032722) (…)there was a delay of trial registration before first patient inclusion which was induced by a misunderstanding between the project coordination for the EU grant (at this time gabo:mi, later on ARTTIC) and the clinical project coordination at the investigator’s site at the Heart Center Leipzig - University of Leipzig. According to initial communication registration should be performed by gabo:mi. When the study coordinator recognized that it has not been performed we immediately registered it at clinicaltrials.gov. At this time only 13 patients at the Heart Center Leipzig University Hospital (and no other study site) have been included into the trial. (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261) |

| Publication | Registration was done after the study has been conducted and the results suggested a publication and further continuation of this research. (doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0264-2) |

| Confidentiality | The principal investigator (N.H.) delayed the registration of the study until data acquisition was completed for confidentiality reasons concerning the study methods, especially the magnetic resonance with the related morphometric measurements. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136375) |

| Logistic/administrative issues | Because of administrative problems, release of registration occurred about six months after study start. The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this intervention are registered. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220436) Due to organisational changes in the research project shortly before the start of the recruitment we put great efforts into avoiding a delayed start of the data collection in the cooperating inpatient units, which resulted in retrospective study registration and a delayed publication of our study protocol. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186967) Registration of the trial was delayed after the enrollment of the first patient due to an administrative error. The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this intervention are registered. (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140584) |

Discussion

In this study, we show that in a sample of 956 results publications from retrospectively registered clinical studies led by German UMCs and completed between 2009 and 2017, only a small number of publications (5%) make the retrospective nature of the registration transparent, and even fewer (2%) explain the reasons for retrospective registration. To our knowledge, two studies have previously quantified the transparent reporting of retrospective registration in journal publications: Al-Durra et al 17 found in a sample of 286 publications in ICMJE member journals and published in 2018 that only 3% (8/286) of papers of retrospectively registered trials in their sample include justifications or explanations for delayed registration. Similarly, Loder et al,18 in their analysis of 70 papers submitted to the British Medical Journal from 2012 to 2015 and rejected for registration issues, found that 3% (2/70) disclosed the registration problem when published in another journal. Our study finds a slightly lower percentage of 2% for explanations of the reasons for retrospective registration, but a higher percentage of 5% for disclosure in a larger sample representing a broader selection of journals and extended time frame.

We found that publications were not significantly more often prospectively registered when they were published in ICMJE member journals or in journals following ICMJE recommendations, but showed a significantly higher rate of TRN reporting. A similar result was found by Al-Durra et al.17 Further, we found that transparent reporting of retrospective registration does not happen significantly more often in publications in ICMJE member journals, and is even happening at a significantly lower rate in journals listed as following ICMJE recommendations.

There were different reasons for retrospective registration brought forth by authors, many of which have been described previously.15 17 18 24 In some cases, authors raise points that lie outside their direct responsibility, such as delays caused by the registry or research not being legally required to be preregistered. Several other reasons provided were within authors’ control, such as logistic and administrative issues, miscommunication between researchers or unawareness of registration policies. In some cases, authors report registering a study to meet journal editorial policies even though registration would not be required for the kind of research otherwise. This is also possibly reflected in the fact that almost a third (31%) of retrospectively registered studies in our sample have been registered between study completion and publication. In one publication, the authors transparently describe that the registration occurred only when ‘results suggested a publication and further continuation of this research’, which has been previously described as ‘selective registration bias’17 and is explicitly called out in ICMJE guidance as it ‘meets none of the purposes of preregistration’.5 Another identified theme revolves around the confidentiality of methods; however, in this case, many other details about the trial could have been preregistered.

Limitations

For feasibility and data quality reasons, our study was based on an existing validated dataset, containing only trials led by German UMCs, which might limit its generalisability to other regions. However, the sample also contained multicentre trials with other countries involved and is larger and from a wider variety of journals compared with previous studies.17 18 Our analysis of retrospective registration is based on trial start dates and registration dates as provided by the two registries used for sampling: Clinicaltrials.gov and DRKS. It is possible that authors did not update their registry entries when delays to the start date occurred. For example, we did not specifically follow-up cases in which authors wrote that a trial was registered prospectively, but the registry dates did not reflect that statement. In order not to reduce the sample size, we also did not correct for varying follow-up in the identification of result publications, for example, by limiting our analysis to publications published within 2 years of trial completion. However, this means that the newer trials in the sample (ie, years 2016, 2017) might not reflect the complete research output of those years as some trials may not have been published by the end of follow-up in 2020 and were therefore excluded from the analysis. The numbers presented in figures 2 and 3 may overestimate the improvements in prospective registration as trials reporting results on time might likely generally show a higher quality of registration conduct and might therefore be registered prospectively at a higher rate.

In our analyses involving the classification into ICMJE-following and non-following journals, we relied on the data provided on the ICMJE website (icmje.org), which are self-reported by journals, that is, a journal must write to the ICMJE that they want to be included in the list. Thus, there are some journals missing in the ICMJE data and therefore in our dataset. For ICMJE member journals (n=12) on the other hand, there is a complete listing available.

Conclusion

The Declaration of Helsinki and other guidelines for responsible clinical research unanimously recommend prospective registration of all clinical research.2 For clinical trials regulated by drug and device regulatory authorities, this was codified into law.4 A major aim of prospective registration is to minimise the risk of undisclosed changes to the protocol after the study started and first results are analysed. When registration happens retrospectively, this major goal is not addressed. The reporting of study registration is generally considered a best practice to make a study more trustworthy. In the case of retrospective registration, in contrast, reporting registration without transparency on the retrospective nature should rather raise concerns as readers might wrongly interpret the mentioning of registration as a quality criterion. This could be considered ‘performative reproducibility’, that is, the ‘pretence of reproducibility without the reality’.25 Journal editors and reviewers could enforce explicit reporting and explanation of retrospective registration, but we found that this rarely happens. To fulfil the ICMJE requirements on reporting retrospective registration, a simple note in the registration statement of the paper would suffice, such as: ‘This study was retrospectively registered as (TRN) at (Registry), (X) days after the trial started because (Reason)’.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Maia Salholz-Hillel for conceptual feedback and technical support. We thank Martin R. Holst and Dr Delwen Franzen for feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, analysis, writing—original draft, project management. SG: Methodology, investigation. DS: Conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, guarantor.

Funding: This work was partly funded under a grant from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (Bundesministerium fuer Bildung und Forschung—BMBF) (01PW18012). The funder was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All code and the data for this study are available at https://github.com/mhaslberger/retrospective-registration. Data are also available in an OSF repository (https://osf.io/8g5cf/).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Simes RJ. Publication bias: the case for an international registry of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1986;4:1529–41. 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.10.1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WMA . World medical association: declaration of helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects [Internet]. 2018. Available: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- 3. World health organization. international standards for clinical trial registries: the registration of all interventional trials is a scientific, ethical and moral responsibility [internet]. version 3.0. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274994 [Google Scholar]

- 4. European Medicines Agency . Regulation (EU) no 536/2014 of the european parliament and of the council of 16 april 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing directive 2001/20/EC [Internet]. 2022. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/536/2022-01-31

- 5. ICMJE . International committee of medical journal editors recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals [internet]. 2021. Available: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf [PubMed]

- 6. De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the international committee of medical journal editors. Lancet 2004;364:911–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4. 10.7326/M15-0288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zarin DA, Keselman A. Registering a clinical trial in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest 2007;131:909–12.:S0012-3692(15)38915-7. 10.1378/chest.06-2450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trinquart L, Dunn AG, Bourgeois FT. Registration of published randomized trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2018;16:173. 10.1186/s12916-018-1168-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birajdar AR, Bose D, Nishandar TB, et al. An audit of studies registered retrospectively with the clinical trials registry of India: a one year analysis. Perspect Clin Res 2019;10:26–30. 10.4103/picr.PICR_163_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scott A, Rucklidge JJ, Mulder RT. Is mandatory prospective trial registration working to prevent publication of unregistered trials and selective outcome reporting? an observational study of five psychiatry journals that mandate prospective clinical trial registration. PLOS ONE 2015;10:e0133718. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mann E, Nguyen N, Fleischer S, et al. Compliance with trial registration in five core journals of clinical geriatrics: a survey of original publications on randomised controlled trials from 2008 to 2012. Age Ageing 2014;43:872–6. 10.1093/ageing/afu086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smaïl-Faugeron V, Fron-Chabouis H, Durieux P. Clinical trial registration in oral health journals. J Dent Res 2015;94(3_suppl):8S–13S. 10.1177/0022034514552492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harriman SL, Patel J. When are clinical trials registered? an analysis of prospective versus retrospective registration. Trials 2016;17:187. 10.1186/s13063-016-1310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boughton S. Retrospectively registered trials: the editors’ dilemma [internet]. research in progress blog. 2016. Available: https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bmcblog/2016/04/15/retrospectively-registered-trials-editors-dilemma/

- 17. Al-Durra M, Nolan RP, Seto E, et al. Prospective registration and reporting of trial number in randomised clinical trials: global cross sectional study of the adoption of ICMJE and declaration of helsinki recommendations. BMJ 2020;369:m982. 10.1136/bmj.m982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loder E, Loder S, Cook S. Characteristics and publication fate of unregistered and retrospectively registered clinical trials submitted to the BMJ over 4 years. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020037. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wieschowski S, Riedel N, Wollmann K, et al. Result dissemination from clinical trials conducted at german university medical centers was delayed and incomplete. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;115:37–45. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Riedel N, Wieschowski S, Bruckner T, et al. Results dissemination from completed clinical trials conducted at german university medical centers remained delayed and incomplete. the 2014 -2017 cohort. J Clin Epidemiol 2022;144:1–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haslberger M, Gestrich S, Strech D. Reporting of retrospective registration in clinical trial publications [internet]. 2023. Available: https://osf.io/8g5cf/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. ICMJE . Journals stating that they follow the ICMJE recommendations [Internet]. 2022. Available: http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hunter KE, Seidler AL, Askie LM. Prospective registration trends, reasons for retrospective registration and mechanisms to increase prospective registration compliance: descriptive analysis and survey. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019983. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buck S. Beware performative reproducibility. Nature 2021;595:151. 10.1038/d41586-021-01824-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-069553supp001.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-069553supp002.pdf (36.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All code and the data for this study are available at https://github.com/mhaslberger/retrospective-registration. Data are also available in an OSF repository (https://osf.io/8g5cf/).