ABSTRACT

The polymorphic fungus Candida albicans remains a leading cause of both invasive and superficial mycoses, including vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). Metabolic plasticity, including carbohydrate catabolism, confers fitness advantages at anatomical site-specific host niches. C. albicans possesses the capacity to accumulate and store carbohydrates as glycogen and can consume intracellular glycogen stores when nutrients become limited. In the vaginal environment, estrogen promotes epithelial glycogen accumulation and C. albicans colonization. However, whether these factors are mechanistically linked is unexplored. Here, we characterized the glycogen metabolism pathways in C. albicans and investigated whether these impact the long-term survival of C. albicans, both in vitro and in vivo during murine VVC, or virulence during systemic infection. SC5314 and 6 clinical isolates demonstrated impaired growth when glycogen was used as the sole carbon source, suggesting that environmental glycogen acquisition is limited. The genetic deletion and complementation of key genes involved in glycogen metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae confirmed that GSY1 and GLC3, as well as GPH1 and GDB1, are essential for glycogen synthesis and catabolism in C. albicans, respectively. Potential compensatory roles for a glucoamylase encoded by SGA1 were also explored. Competitive survival assays revealed that gsy1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutants exhibited long-term survival defects in vitro under starvation conditions and in vivo during vaginal colonization. A complete inability to catabolize glycogen (gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ) also rendered C. albicans significantly less virulent during disseminated infections. This is the first study fully validating the glycogen metabolism pathways in C. albicans, and the results further suggest that intracellular glycogen catabolism positively impacts the long-term fitness of C. albicans in nutrient deficient environments and is important for full virulence.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, glycogen, metabolism, vulvovaginal, candidiasis, Candida

INTRODUCTION

The polymorphic human fungal pathogen Candida albicans must adapt to various host microenvironments during the colonization of host mucosal surfaces. The availability and management of nutrients, including carbohydrates, at diverse biological sites helps C. albicans grow, survive, and adapt to changing environmental conditions. It is widely recognized that in C. albicans and other yeasts, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae), glycolysis plays vital roles in carbon and energy accumulation, aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, as well as the fundamental maintenance of the carbohydrates glycogen, glucan, mannan, and chitin that are found in cell walls (1–4).

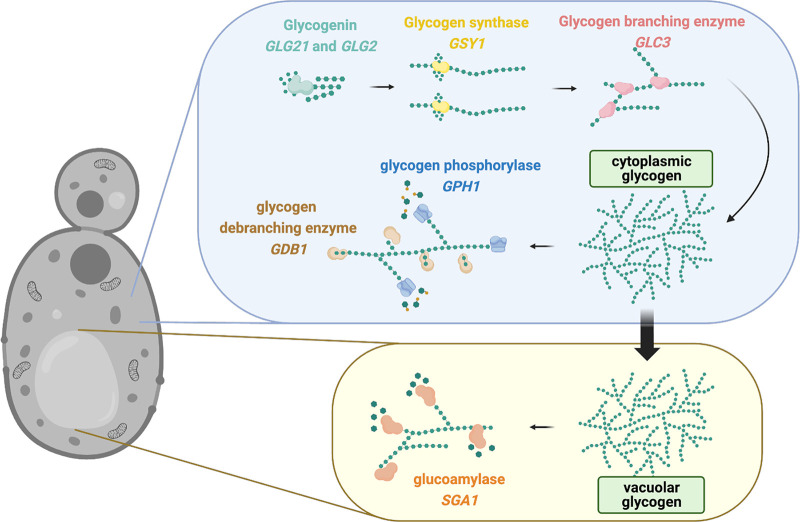

Glycogen biosynthesis and catabolism are important metabolic strategies by which C. albicans and other yeasts cope with starvation, and they have been well-studied in the model yeast species S. cerevisiae (5, 6). As depicted in Fig. 1, glycogen synthesis begins via the conversion of UDP-glucose into short α-1,4-glucosyl oligosaccharide primers by a glucosyltransferase (encoded by GLG21 or GLG2), which is more commonly referred to as glycogenin. These primers are covalently attached to glycogenin to form a nucleation site for the next step of glycogen synthesis. The elongation of linearized glycogen through α-1,4 linkages is accomplished by glycogen synthase (encoded by GSY1) and is followed by the introduction of α-1,6 branch points via the branching enzyme (encoded by GLC3) to build the branched polymer that is referred to as glycogen (5, 7–10). Intracellular glycogen can ultimately be stored in the cytoplasm and vacuole. Thus, two catabolism pathways exist. The cytoplasmic degradation of glycogen occurs via glycogen phosphorylation from the nonreducing ends of α-1,4 linked chains (driven by a glycogen phosphorylase that is encoded by GPH1), and the debranching enzyme (encoded by GDB1) hydrolyzes α-1,6 linked glucose residues to produce glucose-1-phosphate. Second, glycogen can be directly hydrolyzed to free glucose by vacuolar α-glucoamylase (encoded by SGA1) (5, 11–13). Glycogen synthesis and storage in S. cerevisiae is tightly coordinated via transcriptional circuits, including the Snf1/Pka pathway, to control the glycogen synthase abundance and activation states of both the synthase and phosphorylase via cyclin-dependent protein kinases (14–18). However, it has not yet been determined whether the homologues that are predicted to drive glycogen synthesis and catabolism function similarly in the opportunistic pathogen C. albicans.

FIG 1.

Inferred glycogen synthesis and catabolism pathways in C. albicans, based on orthologous functions in S. cerevisiae. Glycogen synthesis is initiated by a glucosyltransferase (otherwise referred to as glycogenin and encoded by GLG2 or GLG21) that converts UDP-α-glucose into short α-1,4-linked glucosyl chains that are covalently attached to form a nucleate core. The glycogen synthase (encoded by GSY1) extends short α-1,4-linked glucosyl primers into elongated chains. The extensive branching of the mature glycogen molecule is achieved via the activity of the glycogen branching enzyme (encoded by GLC3) to introduce α-1,6-linkages. Glycogen is catabolized in a reverse fashion by the glycogen debranching enzyme (encoded by GDB1) to remove α-1,6-linkages, and this is followed by the activity of the glycogen phosphorylase (encoded by GPH1) to generate α-glucose-1-phosphate monomers from α-1,4-linked glucose via the addition of a phosphate. α-glucose-1-phosphate can be further metabolized to enter glycolysis. Yeast can also store glycogen in the vacuole, where glucoamylase (encoded by SGA1) can rapidly degrade glycogen to α-glucose-1-phosphate during sporulation. However, this pathway is less understood than that of conventional GDB1-GPH1-mediated glycogen catabolism. Orthologous sequences were identified by using the Candida Genome Database. The figure was created using BioRender.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is an infection of the vulva and/or vagina that is caused by Candida spp., with 85% to 95% of the cases being caused by C. albicans (19–21). According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and other reports, VVC presents a significant economic impact, resulting in an estimated $368 million in medical costs in the United States per year (22, 23). It is believed that the development of VVC requires the prior asymptomatic colonization of the vaginal mucosa and is associated with vaginal dysbiosis that results from behavioral or other host-related factors, such as pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, or antibiotic use (24–26). In fact, increased estrogen activity (e.g., as observed during the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle) promotes epithelial glycogen accumulation, and free glycogen may exceed glucose levels by approximately 10-fold in the vagina (27, 28). A prior report also suggests that C. albicans is uniquely suited to assimilate glycogen during in vitro growth (29). Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that high glycogen levels in the vaginal environment may positively impact C. albicans survival and its capacity to drive the onset of VVC. Aside from mucosal disease, C. albicans can also cause cases of life-threatening invasive mycosis, in which it may inhabit body organs and must adapt to unique nutrient availabilities, including possibly glycogen (30).

Given these points and the lack of studies regarding the potential connection between glycogen and candidiasis, we wished to conclusively investigate the glycogen metabolism pathways of C. albicans as well as their impacts on fitness at the vaginal mucosa and virulence during invasive diseases. Using a collection of reference and vaginal clinical isolates, we first determined that C. albicans growth is poorly supported when glycogen is supplied as the sole carbon source. Second, the construction of a panel of deletion mutants validated glycogen phosphorylase (GPH1) and debranching enzymes (GDB1) as the major contributors to glycogen catabolism, with vacuolar glucoamylase (SGA1) playing a minor, compensatory role. Additional experiments revealed that GSY1 and GLC3 play key roles in glycogen synthesis. Competitive survival assays confirmed that both gsy1Δ/Δ and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutants exhibited long-term survival defects in vitro under starvation conditions and in vivo during vaginal colonization. Moreover, the median survival of mice that were intravenously challenged with the gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutant was significantly higher than that of the WT strain or of a gph1Δ/Δsga1Δ/Δ+GPH1 strain. Collectively, these results provide strong evidence that glycogen metabolism provides a fitness advantage at the vaginal mucosa, and an inability to catabolize glycogen impacts virulence during disseminated infections.

RESULTS

Extracellular glycogen is a poor substrate for C. albicans growth.

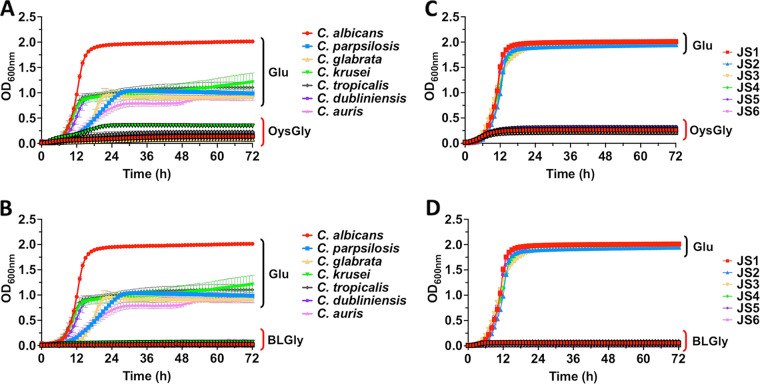

A prior study demonstrated that C. albicans, but not non-albicans Candida species, was capable of assimilating extracellular glycogen in vitro (29). Given that glycogen levels can become relatively high in the vaginal epithelium, it was reasonable to speculate that growth on this carbon source may explain the high incidence of C. albicans that is observed during VVC. However, when using YNB medium with oyster glycogen as the sole carbon source, poor growth was observed in all seven Candida species utilized (C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. auris), compared to YNB medium supplemented with glucose (Fig. 2A). Similar results were observed when bovine liver glycogen was used as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2B). The observed patterns indicated that extracellular glycogen was not an optimal extracellular carbohydrate source for supporting the growth of the Candida species used in this study. In order to rule out potential interstrain heterogeneity exhibited by C. albicans, additional vaginal clinical isolates (JS1 to JS6) were used in a similar growth assay. There was no significant difference in the growth patterns between the various clinical isolates, yet all grew well in medium supplemented with glucose but poorly with oyster or bovine liver glycogen (Fig. 2C and D). Our findings suggest that environmental glycogen acquisition by the Candida species is limited and that C. albicans showed no exclusive advantage in utilizing extracellular glycogen as a carbon source.

FIG 2.

Extracellular glycogen as a sole carbon source is poorly utilized by the Candida species. C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. auris were grown in YNB containing 0.5% glucose or 0.5% (A) oyster glycogen (OysGly) or (B) bovine liver glycogen (BLGly), and the OD600 value was recorded. Similar experiments were performed with the C. albicans vaginal clinical isolates JS1, JS2, JS3, JS4, JS5, and JS6 in 0.5% glucose or 0.5% (C) OysGly or (D) BLGly. All experiments were repeated in triplicate, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Functional characterization of genes involved in glycogen metabolism.

The glycogen metabolism pathways have been well-studied in S. cerevisiae, but they have not been extensively characterized in C. albicans. In order to investigate the impact of glycogen metabolism on the survival and fitness of C. albicans, we employed genetic manipulation approaches to validate genes that contribute to glycogen metabolism. For each individual C. albicans gene that is homologous with those involved in glycogen synthesis (GLG1, GLG2, GSY1, GLC3) and catabolism (GPH1, GDB1, SGA1) in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1), we constructed knockout mutants and revertants. Importantly, the mutant and revertant strains grew and filamented similar to the wild-type under standard laboratory conditions in YNB and buffered RPMI medium (Fig. S1A and B). Moreover, none of the mutants that were tested exhibited susceptibility to peroxide, ionic, cell wall, osmolarity, metal ion, temperature, or pH stress, nor did their growth differ on the alternative carbon sources, namely, glycerol and ethanol (Fig. S2).

Glycogen metabolism mutant and revertant strains do not display general growth or filamentation defects under standard laboratory conditions. (A) WT, glycogen synthesis mutants (glg2Δ/Δ, glg21Δ/Δ, gsy1Δ/Δ, glc3Δ/Δ) and their revertants (glg2Δ/Δ+GLG2, glg21Δ/Δ+GLG21, gsy1Δ/Δ+GSY1, glc3Δ/Δ+GLC3), or glycogen catabolism mutants (gdb1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, sga1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ) and their revertants (gdb1Δ/Δ+GDB1, gph1Δ/Δ+GPH1, sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+GPH1, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1) were inoculated in YNB medium containing 0.5% glucose, and their growth was monitored for 48 h at 30°C with shaking by measuring the OD600 value. (B) These same strains were inoculated in MOPS-buffered RPMI-1640 (pH 7.0) and grown for 4 h at 37°C with shaking. Filamentation was digitally captured via light microscopy (scale bar = 50 μm). Download FIG S1, TIF file, 2.5 MB (2.5MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

C. albicans glycogen mutants show no sensitivity to osmotic, oxidative, pH, temperature, or cell wall stress or growth differences on alternative carbon sources, compared to the wild-type strain. C. albicans overnight cultures were washed twice and adjusted to 2 × 107 cells/mL. The indicated serial dilutions were spotted (5 μL) onto YP agar plates containing dextrose, glycerol, or ethanol (as noted) either alone or containing the specified stressors. Unless noted otherwise, the plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h, prior to digital image acquisition. The data are representative of two independent repeats. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 3.1 MB (3.1MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

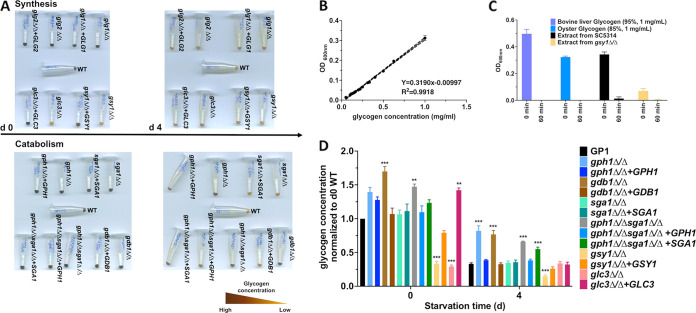

Both qualitative and quantitative iodine staining approaches were used to assess glycogen levels at baseline and following starvation (31). Strains were grown overnight in YNB supplemented with glucose (day 0) and were transitioned to YNB lacking a carbon source to induce starvation, where they were incubated for 4 days (day 4). A notable glycogen synthesis defect was observed in the gsy1Δ/Δ and glc3Δ/Δ strains, compared to the WT strain GP-1 at day 0, as indicated by a lack of dark brown coloration following iodine staining (Fig. 3A). These phenotypes were reversed by gene complementation. No defect was observed for the glg2Δ/Δ or glg21Δ/Δ mutants, as these genes likely have compensatory functions, given their similar predicted roles. Glycogen catabolism defects were observed in the gph1Δ/Δ, gdb1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ, and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1 strains after starvation (day 4), whereas the revertant and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+GPH1 strains regained their capacities to utilize glycogen, similar to the WT (Fig. 3A). A more accurate quantitative approach was utilized, in which the glycogen fraction was extracted from C. albicans, stained with iodine, and compared to a standard curve that was generated using oyster glycogen (Fig. 3B) (12, 31, 32). In order to verify whether iodine staining was sensitive to glycogen, extracts from the WT and gsy1Δ/Δ strains, as well as aliquots of commercial bovine liver and oyster glycogen, were stained before and after enzymatic digestion with α-amylase (1). The iodine signal was almost completely ablated post-treatment, suggesting that the extraction procedure does indeed precipitate glycogen and that this assay accurately reflects the cellular glycogen content (Fig. 3C). Generally, the results paralleled those of the qualitative assay, with the exception that the gph1Δ/Δ+GPH1 strain appeared to demonstrate elevated glycogen levels at baseline (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these data indicated that the glycogen synthesis pathways in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae are generally conserved and are controlled by similar genes. Unlike in S. cerevisiae, there does not appear to be a functionally redundant glycogen synthase paralog in C. albicans (33). Similarly, the main glycogen catabolism pathway of C. albicans was found to be mediated by glycogen phosphorylase (GPH1) and glycogen debranching (GDB1) enzymes, and this was confirmed by elevated glycogen levels being detected in the gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1 strain, compared to the gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+GPH1 strain, suggesting that SGA1 cannot compensate for the loss of GPH1 or GDB1 under these specific in vitro conditions. Thus, we conclude that the critical genes that contribute to C. albicans intracellular glycogen synthesis are GSY1 and GLC3, whereas catabolism is driven largely by GPH1 and GDB1.

FIG 3.

The deletion of predicted glycogen metabolism genes confirm function in C. albicans. (A) C. albicans glycogen synthesis mutants (glg2Δ/Δ, gsy1Δ/Δ, glc3Δ/Δ) and revertants (glg2Δ/Δ+GLG2, gsy1Δ/Δ+GSY1, glc3Δ/Δ+GLC3) were grown overnight in YNB medium, and either cell pellets were stained immediately with iodine solution or cells were starved for 4 days in YNB media lacking a carbon source and then stained. Similar experiments were performed using glycogen catabolism mutants (gdb1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, sga1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δsga1Δ/Δ) or revertants (gdb1Δ/Δ+GDB1, gph1Δ/Δ+GPH1, sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1, gph1Δ/Δsga1Δ/Δ+GPH1, gph1Δ/Δsga1+SGA1). Images were captured on a digital scanner and are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) A standard curve was generated by iodine staining a series of oyster glycogen dilutions and plotting the OD600 nm values. Curves were generated in triplicate to demonstrate reproducibility, and the data are depicted as the mean ± SEM. (C) Extracted material from WT or gsy1Δ/Δ strains or 1 mg of resuspended commercial oyster or bovine liver glycogen was stained with iodine solution pre- (0 min) and post- (60 min) enzymatic treatment with glucoamylase. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. (D) Glycogen was extracted from the above-described strains, and the precipitate was resuspended and stained with iodine solution. The data were interpolated from a standard curve of oyster glycogen, were normalized to the WT, and are depicted as the mean + SEM. A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test was used for the statistical analyses. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Glycogen metabolism contributes to the long-term survival of C. albicans in vitro.

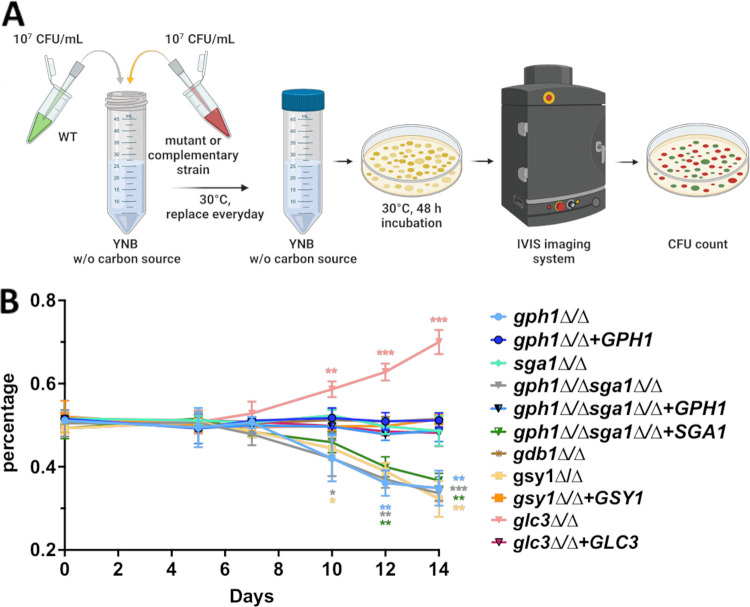

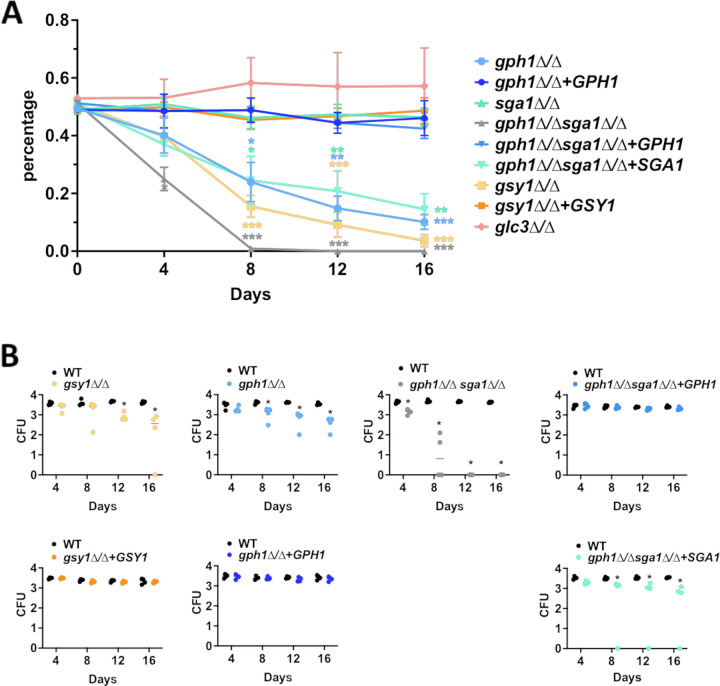

We have demonstrated that extracellular glycogen, as a sole carbon source, does not robustly support C. albicans proliferation. However, C. albicans may exist indefinitely as a member of the normal vaginal microbiota, prior to driving a symptomatic infection and intracellular glycogen content. Also, its metabolism may play a role in fungal fitness and in the colonization of the dynamic vaginal environment. Thus, we used an in vitro competitive growth assay under starvation conditions with fluorescently-tagged WT and mutant or revertant strains to indirectly test this hypothesis (Fig. 4A). The gsy1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ, and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1 strains demonstrated significantly reduced competitive fitness, compared to the wild-type strain, and this survival defect was largely rescued via gene complementation (Fig. 4B). One exception was that the activity of SGA1 was not sufficient to compensate for the loss of GPH1 in the double mutant under long-term starvation conditions. This further confirms a dominant role for GPH1 in the driving of glycogen catabolism. Surprisingly, the gdb1Δ/Δ mutant did not exhibit a competitive fitness disadvantage, despite its confirmed role in glycogen catabolism. Also, unexpectedly, the glc3Δ/Δ mutant was more fit than was the wild-type under these conditions (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Disruption of glycogen metabolism impacts fitness during in vitro starvation. (A) Schematic depicting the experimental design. GFPy-tagged WT and dTomato-tagged glycogen metabolism mutant or revertant strains were mixed in equal proportions and subjected to long-term starvation in YNB lacking a carbon source. At days 0, 5, 7, 10, 12, and 14 post-inoculation, aliquots were removed, density-adjusted, and plated onto YPD medium. Fluorescence images of the agar plates were captured using an IVIS Spectrum imager. (B) Fluorescent CFU were enumerated from the images, and those exhibiting red fluorescence were reported as a percentage of the total. The data are depicted as the mean ± SEM. A multiple t test was used to compare each mutant and revertant percentage at each time point. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The disruption of glycogen metabolism impacts C. albicans fitness and virulence.

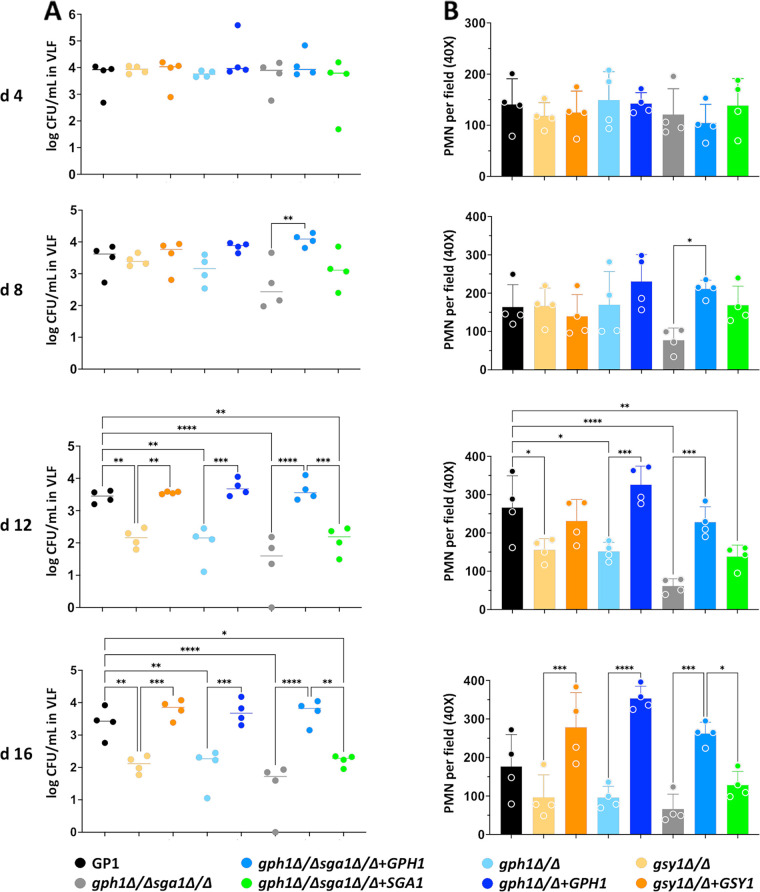

In order to understand whether glycogen metabolism impacts C. albicans fitness at the vaginal mucosa, we employed a standard murine model of VVC that is amenable to the longitudinal analysis of fungal colonization (34–36). Both the survival rate and the absolute quantitative counts were analyzed to determine whether C. albicans competitive fitness at the vaginal mucosa could be impacted by disrupted glycogen metabolism pathways. Similar to in vitro findings, the gsy1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ, and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1 strains were less fit in vivo, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5A and B). The remaining strains colonized mice throughout the infectious time course in a manner that was similar to that of the wild-type (Fig. S3). The glc3Δ/Δ mutant exhibited a slightly increased survival trend in vivo that was similar to the in vitro findings, but it was not significant. The gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ had a notable, severe competitive survival defect with no detectable CFU being recovered by day 12 postinoculation. Interestingly, unlike the in vitro findings, the reversion of SGA1 in this mutant somewhat rescued the survival defect, similar to that observed with the complementation with GPH1 (Fig. 5A and B). As neutrophil influx to the vaginal lumen is a hallmark of vaginitis immunopathology, single-strain infections were performed using gsy1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, or gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutants, and their respective complemented strains, fungal burden, and neutrophils were monitored longitudinally (35). The fungal burden was similar among all strains up to day 4 postinoculation, but the mutants were generally less fit than were the revertants or the WT at later time points (Fig. 6A). The neutrophil levels were similar among all strains at day 4, but they decreased concomitantly with the fungal burdens during infections with mutant strains (Fig. 6B). As all strains formed hyphae at the vaginal mucosa, it was unsurprising that the neutrophil levels were initially similar, given the importance of the yeast-to-hypha switch in driving immunopathogenesis (Fig. S4). Collectively, the data demonstrate that the genetic deletion of glycogen synthase, glycogen phosphorylase, and/or α-glucoamylase impairs the fitness of C. albicans at the vaginal mucosa, independent of filamentation.

FIG 5.

Glycogen synthase, glycogen phosphorylase, and glucoamylase mutants are less competitively fit during vaginal colonization. (A) Groups of mice (n = 4) were inoculated with mixed cultures of GFPy-tagged WT or dTomato-tagged glycogen metabolism mutant or revertant strains. At day 0 (inoculum), 4, 8, 12, and 16 (lavage) samples were plated onto YPD agar plates containing 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and fluorescent CFU were enumerated via IVIS imaging. Strains are depicted in the figure legend. The data are expressed as the percentage of red fluorescent colonies that were recovered and are depicted as the mean ± SEM. A multiple t test was used to compare each mutant and revertant percentage at each time point. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B) CFU obtained from vaginal lavage samples that were obtained at days 4, 8, 12, and 16 were enumerated. The line represents the median. A multiple t test was used to compare each mutant and revertant percentage at each time point. *, P < 0.05.

FIG 6.

Glycogen synthase, glycogen phosphorylase, and glucoamylase mutants exhibit reduced colonization and immunopathology during murine vaginitis. Vaginal lavage fluids (VLF) obtained from mice (n = 4 per group) were analyzed at days 4, 8, 12, and 16 post-inoculation for (A) fungal burden (medians) and (B) PMN recruitment, as determined via microscopy (mean ± SD). The statistical testing of significance was achieved by using a one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal-Wallis (CFU data) or with Tukey’s (PMN data) post-test, and statistical significance is denoted as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The losses of glucoamylase and the glycogen branching enzyme have no impact on vaginal colonization. Groups of mice (n = 4) were inoculated with 1:1 mixed cultures of GFPy-tagged WT or dTomato-tagged glycogen metabolism mutant or revertant strains. At days 4, 8, 12, and 16, vaginal lavage samples were plated onto YPD agar plates containing 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol and fluorescent CFUs that were enumerated via IVIS imaging. The strains are depicted in the figure legend. The line represents the median. A multiple t test was used to compare each mutant and revertant percentage at each time point. *, P < 0.05. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 0.2 MB (242.4KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The loss of glycogen synthase, glycogen phosphorylase, and/or glucoamylase does impact neutrophil influx or filamentation during initial vaginal colonization. VLF were obtained at day 4 postinoculation and stained using the Papanicolaou technique. Images were digitally captured (scale bar = 100 μm). The red arrows depict hyphae. The small, round, blue cells are neutrophils. The data are representative of 5 fields of view from each mouse group (n = 4). Download FIG S4, TIF file, 5.6 MB (5.6MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

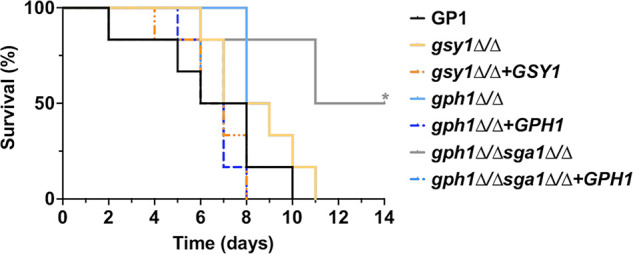

We also determined whether glycogen metabolism contributes to virulence by using a model of invasive systemic candidiasis. Mice were intravenously challenged with strains demonstrating impacted fitness in the VVC model and were survival monitored (Fig. 7). Mice challenged with the gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutant demonstrated significantly increased survival, compared to those challenged with the WT or with the gph1Δ/Δsga1Δ/Δ+GPH1 revertant. Whereas the competitive fitness was decreased for the gsy1Δ/Δ and gph1Δ/Δ strains in the vaginal model, the median survival was not altered in the animals that were intravenously challenged with these strains, indicating that glycogen metabolism possibly impacts the biology of C. albicans in a site-specific manner.

FIG 7.

Disrupted glycogen catabolism in C. albicans reduces lethality during invasive candidiasis. Mice were intravenously inoculated with glycogen synthesis (gsy1Δ/Δ and gsy1Δ/Δ +GSY1) or catabolism (gph1Δ/Δ and gph1Δ/Δ +GPH1 or gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ +GPH1) mutant or revertant strains and were assessed for survival for up to 14 days postinfection. Kaplan-Meier curves were assessed for statistical significance via a log rank test. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Most microorganisms, including bacteria, parasites, and fungi, accumulate carbon and energy reserves to cope with starvation conditions that are temporarily present in the environment (5, 6, 37). Glycogen metabolism constitutes a key strategy that regulates systemic carbon or energy allocation for such purposes. Major advantages in using glycogen as a carbohydrate reservoir is that this macromolecule has little effect on the internal osmotic pressure of the cell, and the extensive structural branching allows for efficiently compact storage (38, 39). Numerous reports in the literature have demonstrated that the loss of glycogen accumulation via the genetic disruption of glycogen synthase across multiple microbial species, including Lactobacillus acidophilus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus mutans, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and S. cerevisiae, confers fitness defects, both in vitro and in vivo, in the murine gastrointestinal tract and lung (40–45). We now demonstrate that such fitness or virulence defects extend to C. albicans during both vulvovaginal and systemic candidiasis, with a more prominent role during mucosal colonization. The lack of noticeable susceptibilities to a variety of stressors in vitro suggests that reduced in vivo fitness is linked to metabolic defects that are induced by disrupted glycogen homeostasis. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the unique or combinatorial stressors that are encountered in vivo may disproportionately impact glycogen mutants. In humans, a number of diseases are associated with abnormal glycogen metabolism, including glycogen storage disease (GSD), which has several presentations due to varied causal genetic predispositions, including glycogen overaccumulation in the liver (46). One approach to limiting glycogen accumulation is to target glycogen synthase with small molecule inhibitors, as it is the rate limiting step for glycogen biosynthesis (47). As the genetic disruption of glycogen accumulation (via the deletion of GSY1) or utilization (via the deletion of GPH1) significantly impaired the long-term fitness of C. albicans at the vaginal mucosa, it is intriguing to speculate whether fungal-specific small molecules could be rationally designed to deter the colonization of C. albicans at mucosal surfaces.

While glycogen metabolism has been extensively explored in S. cerevisiae, mechanistic studies in pathogenic fungi have, until now, been limited. The functions of the orthologous genes that are involved in glycogen synthesis (GSY1, GLC3) and catabolism (GPH1, GDB1, and SGA1) have been inferred by sequence homology, but we have now confirmed and validated these functions in C. albicans. Interestingly, ScGSY2 is responsible for a majority (>85%) of the glycogen synthase activity in S. cerevisiae, similar to CaGSY1, with ScGSY1 playing a more nuanced, condition-specific role (7, 48). However, the genetic loss of total glycogen synthase activity in both yeasts is clearly not lethal (7). Unfortunately, we were unable to truly determine the impact of the genetic deletion of the glucosyltransferase glycogenin that is encoded by GLG2. In S. cerevisiae, GLG2 has a paralog, namely, GLG1 that arose from whole-genome duplication. C. albicans also possesses a homolog to GLG2, termed GLG21, which is inferred to have the same function as ScGLG1. We were able to successfully generate either a glg2Δ/Δ or glg21Δ/Δ (Fig. 3A) deletion strain that showed no phenotypic difference with respect to glycogen accumulation or utilization, compared to the wild-type, suggesting a compensatory function. However, despite multiple attempts, we were unable to create a glg2Δ/Δ glg21Δ/Δ double deletion mutant, indicating that these genes possibly serve other essential roles for cellular homeostasis.

The data from this study demonstrate that various C. albicans isolates and non-albicans Candida species seemingly do not possess the capacity to efficiently utilize extracellular glycogen as a sole carbon source. These findings were somewhat surprising, as a report by Dennerstein and Ellis showed that all C. albicans (n = 30) isolates could assimilate glycogen, whereas the entire collection of NAC species that was used (n = 26) could not (29). However, there are important details that are absent that might explain the differences that were observed between studies, including the growth time, liquid versus solid agar growth, glycogen source and purity, and phenotypic diversity among the Candida isolates that were used. That said, the glycogen catabolism genes of C. albicans lack leader signal sequences that would target their secretion into the external environment. Given the relatively large sizes of glycogen particles, importers have not been described. Lactobacillus species that thrive in glycogen rich environments, such as the vaginal mucosa typically rely on host α-amylases that degrade the glycogen that is produced by epithelial cells to maltose and maltotriose, which support bacterial growth and subsequent lactic acid production. However, recent work has identified secreted amylopullulanases that exist in some lactobacilli that directly catabolize glycogen (49, 50). Unfortunately, a sequence alignment search of the C. albicans SC5314 genome for PulA homologs did not reveal any sequence similarity. Therefore, it is likely that C. albicans cannot use extracellular glycogen directly, but it may be able to subsist on spontaneous or host-mediated glycogen degradation products or via the release of glycogenic enzymes via autolysis. In vitro enzymatic or glucose isotope labeling approaches will be required to conclusively validate these hypotheses. It should also be pointed out that glycogen from different species displays heterogeneous glycogen particles with respect to size, polymerization, and branching (51–53), as demonstrated by in vitro enzymatic assembly assays that used branching enzymes from different species (54, 55). Such disparities in structure also alter the degradation kinetics. Thus, it is possible that C. albicans prefers or utilizes specific glycogen structures, aside from what we have tested herein. The recombinant expression and purification of C. albicans glycogen enzymes, coupled with in vitro degradation assays, would be desirable.

The construction of glycogen synthesis and catabolism mutants generally yielded the expected phenotypes, with respect to glycogen content and observed under basal and starvation conditions. However, we did observe hyper glycogen accumulation phenotypes in a few revertant strains, including gph1Δ/Δ+GPH1 and glc3Δ/Δ+GLC3. We tested multiple transformants from separate transformations, each with the same phenotype (data not shown). One potential explanation for this is that the revertant copy was introduced at the URA3 locus, as varied expression levels of reintegrated genes at this locus have been reported. Additionally, we chose to clone a 1 kb promoter fragment upstream of the translation start site for each revertant gene. It is possible that additional regulatory sequences were absent, compared to those found at the native loci. Moreover, a single copy of each gene was reintroduced into the mutants. So, the gene dosage could also play a minor role in the observed differences. In any case, these hyper glycogen accumulation phenotypes did not influence the validation studies for GLC3 and GPH1, as the revertant strains accordingly compensated the defects in glycogen accumulation and catabolism that were observed in the mutants.

It is surprising that a survival defect was not observed in the glc3Δ/Δ or gdb1Δ/Δ strains either in vitro or in vivo. GLC3 encodes a glycogen branching enzyme and introduces α-1,6 branch points to the otherwise α-1,4 linked linear glucose polymer to increase structural complexity, rendering it more stable for longer term storage. Iodine detects glycogen by intercalating into helical chains of >10 linked glucose polymers to from a deep brown-colored complex (31). Thus, it is possible that alternative length α-1,4-linked unbranched glucose polymers exist in the glc3Δ/Δ mutant that stain lesser than does fully branched glycogen but still provide readily (and perhaps more accessible) available substrate for enhanced survival under starvation conditions. In a similar but opposite fashion, GDB1 encodes a debranching enzyme that resolves α-1,6 linkages to facilitate glycogen degradation. However, functional GPH1 is still able to remove glucose-1-phosphate from branched glycogen but does so in a relatively inefficient manner, stalling at the α-1,6 branchpoint. Therefore, the gdb1Δ/Δ mutant may still be able to generate enough glucose from glycogen to survive under starvation conditions. Whereas shorter chain polysaccharides and inefficient glucose-1-phosphate generation from mature glycogen may be sufficient for survival, there is compromised capacity for C. albicans to store glucose long-term in a form that can be rapidly mobilized for glycolysis when needed.

Regarding glycogen catabolism, SGA1 appeared to have a differential capacity to support C. albicans survival in vitro and in vivo. SGA1 was originally described as a sporulation-specific enzyme that is responsible for the mobilization of glycogen reserves in germinating yeast spores (56, 57). More recently, SGA1 was shown to encode a vacuolar α-glucosidase that aids glycogen degradation in this organelle during late stationary-phase growth (12). In S. cerevisiae, glycogen is delivered to the vacuole primarily via the process of autophagy (5). Our data demonstrated that restoring SGA1 was not able to rescue the long-term survival defect of gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ in vitro, whereas it was able to do so in a limited fashion in vivo. It is possible that alternative carbon sources exist in vivo that are optimal substrates for Sga1 and are not found in defined YNB medium during in vitro growth. It is worth noting that C. albicans mainly adopts a hyphal morphology in the murine VVC model, and it is possible that SGA1 may play a hypha-specific role in survival. Given that normal vacuole extension is required for the yeast-to-hypha switch and for full virulence, vacuolar glycogen stores are possible important for this process or possibly contribute to hyphal survival and could possibly explain the elevated median survival during hematogenous infection with the gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ but not the gph1Δ/Δ mutant. Although we did not observe any hyphal growth defects with any of the mutants, even at the vaginal mucosa, other more nutritionally complex or unique in vivo environments may be relevant.

Lastly, prior methods that were utilized to extract glycogen from yeast cells resulted in impure fractions containing insoluble β-(1→3)-glucan, which is a major component of the fungal cell wall that is capable of stimulating innate immune responses (58–60). Our lab has recently demonstrated that glycogen is covalently linked to β-(1→3)-β-(1→6)-glucan via the β-(1→6)-linked side chain in a number of Candida species, including C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. haemulonii, and C. auris (1). It is unclear whether glycogen is linked at the cytoplasmic or external face of the cell wall. Nonetheless, it is tempting to speculate that dysregulated glycogen metabolism may directly or indirectly affect host-pathogen interactions by altering the cell wall composition. Further studies to address this possibility are warranted and are underway in our laboratories.

Conclusion.

Mucosal candidiasis and invasive candidiasis involve a series of complex mechanisms that underlie the interaction between C. albicans and its host. Although C. albicans exhibits flexible carbohydrate metabolism in various environments, we determined that extracellular glycogen could not be readily utilized as a substrate by C. albicans. The genetic deletion and complementation of key genes that are involved in glycogen metabolism in S. cerevisiae confirmed that GSY1 and GLC3, as well as GPH1 and GDB1, are essential for proper glycogen synthesis and catabolism, respectively, in C. albicans. Furthermore, using competitive in vitro and in vivo models, we have demonstrated that gsy1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ mutants exhibit a long-term survival defect in vitro under starvation conditions and a fitness defect in vivo during vaginal colonization. A global glycogen catabolism mutant (gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ) is less virulent during systemic challenge, as well. These findings provide direct evidence that the C. albicans intracellular glycogen metabolism plays an important role for survival and pathogenesis at the vaginal mucosa and target organs. Overall, this is the first study to fully validate glycogen metabolism pathways in C. albicans, and the results further show that intracellular glycogen catabolism positively impacts the anatomical site-specific fitness and virulence of C. albicans in the host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The animals used in this study were housed in AALAC-approved facilities that are located in the Regional Biocontainment Laboratory (RBL) at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC). All of the animal work conducted in this study was approved by the UTHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocols 21–0265 and 19–0115. Every effort was taken to ensure that the use of animals was necessary for hypothesis testing, that the minimum number of animals required was utilized, and that steps were taken to minimize discomfort. Mice were given standard rodent chow and water ad libitum, and they were monitored for signs of distress, including noticeable weight loss and lethargy.

Microorganism growth.

C. albicans and non-albicans Candida strains were maintained as glycerol stocks and were stored at −80°C. A small amount of stock was spread onto yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) agar and incubated at 30°C for 48 h to obtain isolated colonies. A single colony was transferred to liquid YPD and incubated at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 16 h. In some experiments, C. albicans was inoculated into buffered RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7) and incubated at 37°C to assess the hyphal growth.

Strains, RNAs, and primers.

All of the strains that were used or generated are listed in Table S1. All of the vectors that were used or generated in this study are listed in Table S2. All of the primers that were used for vector construction, strain construction, and Sanger sequencing, as well as the crRNA and gRNA sequences that were used in CRISPR-Cas9 for gene editing are listed in Table S3.

List of Candida strains used or created in this study. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.07 MB (69.4KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

List of vectors used or created in this study. Download Table S2, PDF file, 0.03 MB (30.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

List of oligonucleotides used in this study. Download Table S3, PDF file, 0.06 MB (65.6KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Vector construction.

In order to generate strains harboring the gene of interest (GOI) promoter, entire open reading frame (ORF), and terminator, PCR products were amplified from genomic DNA that was isolated from C. albicans strain GP-1, using the primers GOI_AmpF-KpnI and GOI_AmpR-SalI (unless noted otherwise in the supplementary tables). Amplicons were digested with KpnI and SacI prior to ligation into KpnI+SacI digested pLUX (unless noted otherwise in supplementary tables) to build pLUX-GOI. In order to generate strains expressing GFPy and dTomato, plasmid DNA from pKE4-PrTEF1-GFPy and pKE4-PrTEF1-dTomato was amplified using the primers PrTEF1_AmpF-ClaI and tADH1_AmpR-SpeI. The resulting amplicons were digested with ClaI and SpeI and were ligated into similarly digested pDUP3 to yield vector pDUP3-PrTEF1-GFPy and pDUP3-PrTEF1-dTomato. All of the vectors were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. Colonies were screened by growth on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Subsequent plasmid isolation and digestion occurred with proper restriction enzymes. All plasmids were verified for the integrity of their coding sequences via Sanger sequencing (GENEWIZ, Inc.), using gene-specific primers.

Strain construction using auxotrophic markers.

The deletion cassettes for some of the mutants that were constructed in this study were amplified via PCR with the primers GOI_DISF and GOI_DISR, using vector pRS-ARG4ΔSpeI or pGEM-HIS1 as the templates. The GOIΔ/Δ ura3Δ/Δ deletion mutant was produced via the sequential deletion of each GOI allele, using the HIS1 and ARG4 markers from BWP17, transformation via the lithium acetate method, and plating on selective media, as previously described (61). The correct integration of the deletion cassettes was confirmed at each step via the PCR of genomic DNA with the primer pairs ARG4_INTF2+GOI_AMPR and ARG4_INTR2+GOI_AMPF (ARG4 integration) or HIS1_INTR2+GOI_AMPR and HIS1_INTF2+GOI_AMPF (HIS1 integration). The lack of an intact allele was confirmed by using the primer pair GOI_DETF+GOI_DETR. An isogenic GOIΔ/Δ mutant (EV) and reconstituted strains were produced by transforming the ura3Δ/Δ mutant with the following NheI-digested plasmids: pLUX (vector alone) and pLUX-GOI. The correct integration of plasmids at the IRO1-URA3 locus was confirmed via PCR using the primer pair LUXINT_DETF+LUXINT_DETR, and restoration was verified using the primer pair GOI_DETF+GOI_DETR. In order to create the GFPy and dTomato tagged strains, pDUP3-based plasmids were digested with SfiI and were transformed into the NEUT5 locus of relevant C. albicans strain by the lithium acetate method, as described previously (62). Single colonies were screened by plating onto a YPD agar plate containing 200 μg/mL nourseothricin. The integration at the NEUT5 locus was confirmed by using the primer pairs NEUT5L_AMPF+NAT1_INTF and NEUT5L_AMPR+tADH1_AmpR-SpeI, as well as by epifluorescence microscopy.

Strain construction with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.

As we repeatedly could not generate a gdb1Δ/Δ strain by means of the standard techniques described above, we utilized CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to create this strain and its revertant Δ/Δgdb1+GDB1. Similarly, we constructed the double-knockout strain gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ (from the gph1Δ/Δ strain) and deleted SGA1 or GPH1 from single revertants to generate gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+GPH1 and gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1, using CRISPR-Cas9 as described previously (63). In brief, the disruption repair templates were amplified with the primers GOI_CC9KO-F+GOI_CC9KO-R, using SAT1-flipper and CaHygB-flipper plasmids, which harbored resistance to nourseothricin and hygromycin, respectively. C. albicans cells were treated in transformation buffer (1× Tris-EDTA and 0.1 M lithium acetate [pH 7.5]) and buffer with 25 mM dithiothreitol at 30°C for 45 min and 30 min, respectively. The cells were then washed and mixed with a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that was composed of gene-specific guide RNAs (gRNA), universal tracrRNA, 2 μg Cas9 protein, and a total of 2 μg PCR-generated repair templates (1 μg for each template). Transformation was performed using a Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (Bio-RAD) with a single pulse at 1.8 kV. After recovery for 4 to 6 h at 30°C in YPD medium, the cells were plated on YPD plates containing 200 μg/mL nourseothricin (GoldBio) and 600 μg/mL hygromycin B (GoldBio). Selected colonies were then cultured overnight in yeast-peptone (YP) medium containing 2% maltose (YPM) to induce cassette excision. After selection under a lower antibiotic pressure (YPD agar plates containing 25 μg/mL nourseothricin and 75 μg/mL of hygromycin), the correct genomic integration and the excision of the resistance cassettes were confirmed via the growth phenotype on YPD, YPD + 200 μg/mL nourseothricin, and YPD + 600 μg/mL hygromycin plates as well as via PCR amplification using the primers FRT_F+GOI_AmpR, FRT_R+GOI_AmpF, and GOI_DETF+GOI_DETR. In order to generate the gdb1Δ/Δ+GDB1 revertant, a repair template was PCR amplified by overlap extension PCR, which fused part of the NEUT5 promoter and ORF region of GDB1 and the ADH1 terminator, which were amplified from either the GP-1 gDNA or the pDUP3-tAHD1 plasmid, as described previously (63). The Δ/Δgdb1 strain was edited with the CRISPR-Cas9 protocol, as described above, except that crNEUT5pDUPup crRNA was used during the RNP assembly. The transformation and genotype confirmation were then performed accordingly, as mentioned above, with the primers NAT1_INTF+NEUT5L_homology-F, PrGDB1_INTR+NEUT5L_homology-R, and GDB1_DETF+GDB1_DETR.

Analysis of growth and stress tolerance.

Candida species were grown as described above, washed, and diluted to 105 cells/mL in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium containing 0.5% oyster glycogen (Sigma-Aldrich, G8751), bovine liver glycogen (Sigma-Aldrich, G0885), or glucose. 200 μL were transferred to the wells of a microtiter plate. OD600 readings were captured at 60 min intervals, using a BioTek Synergy spectrophotometer with an incubation temperature of 30°C and orbital shaking at 200 rpm. The experiments were repeated in technical quadruplicate and biological triplicate. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For the stress tolerance and phenotypic assays, C. albicans overnight cultures were washed twice with PBS and adjusted to 2 × 107 cells/mL. Serial dilutions of cells were spotted (5 μL) onto YP agar plates containing dextrose (or other carbon sources, as indicated) under the following conditions: temperature (30°C, 37°C, or 42°C), pH (3.5 and 8.5), peroxide stress (5 mM or 25 mM H2O2), osmotic stress (1 M sorbitol), ionic stress (100 or 500 mM CaCl2, 1.5 M NaCl), metal ion stress (10 mM MnCl2), cell wall stress (25 μg/mL Congo red, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate), or alternative carbon sources (3% glycerol or 3% ethanol). Unless indicated, the plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h, prior to the acquisition of images using a Gel Doc XR Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Hyphal growth.

Strains were grown overnight in YNB medium with shaking at 30°C. The following day, cultures were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via centrifugation, counted via hemocytometer, and adjusted to a final density of 5 × 106 cells/mL in MOPS-buffered pH 7 RPMI 1640 medium. Cultures were returned to the incubator for 4 h of incubation at 37°C, and aliquots were then transferred to glass slides. Images were captured using a Nikon Ni-U microscope with differential images contrast (DIC), a 40× objective, and the NIS-Elements software package.

Glycogen extraction from C. albicans.

Glycogen isolation was performed as previously described, with modification (12, 32). Aliquots of 4 × 108 C. albicans cells were harvested and washed twice. The wet weights of the pellets were recorded, and the pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thawed pellets were resuspended in 200 μL 20% NaOH and boiled for 1 h with occasional vortexing. Cells were thoroughly resuspended by mixing, chilled on ice for 2 min, neutralized with 150 μL 5 M HCl, and centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants were transferred to chilled microtubes containing 1 mL ice-cold 95% ethanol and were incubated for 30 min at −20°C. Precipitate was collected via centrifugation and washed twice with 66% ethanol. Pellets were dried at room temperature and redissolved in PBS (pH 7.0).

Iodine staining and standard curve.

A 40× iodine stock solution (20 mg/mL I2 in 40 mg/mL KI) was prepared and stored, protected from light. Cell pellets were harvested from overnight cultures in YNB and were washed twice with PBS. Pellets were then resuspended in 1 mL 1× iodine working solution and were incubated at room temperature for 10 min in the dark. Images were acquired using an EPSON digital scanner. The images are representative of 3 independent repeats. In order to quantitatively measure the cellular glycogen content, extracted glycogen pellets were dissolved in 195 μL PBS. Then, 5 μL of iodine stock solution were added. In order to generate a standard curve, oyster glycogen was dissolved in PBS, serially diluted, and similarly stained with iodine working solution. The OD600 was measured from both experimental and standard samples, the blank subtracted values were calculated, and a curve was generated by using a linear regression in GraphPad Prism (64). The glycogen concentration (mg/mL) was interpolated, transited to a mg/g value, based on the wet weights of pellets, as described previously, and normalized to the day 0 WT. The experiments were repeated in biological triplicate, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Amylase treatment of glycogen and cell extracts.

As described previously (1), α-amylase (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number A4551) was reconstituted in PBS at 0.5 mg/mL. The glycogen fractions that were extracted from SC5314 and gsy1Δ/Δ or aliquots of commercial bovine liver or oyster glycogen (Sigma-Aldrich) were reconstituted in PBS and treated with α-amylase or PBS. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 60 min on a rotary shaker (20 rpm). Aliquots (200 μL) were stained with iodine solution pre- and post-amylase treatment, as described above, and were then measured at OD600.

In vitro competitive survival assay.

Overnight cultures of both the GFPy-tagged GP-1 strain and the dTomato-tagged glycogen mutants or revertants were washed, counted, and combined at a 1:1 ratio (107 CFU/mL each) in YNB without glucose (pH 7.5). Each day, cells were pelleted via centrifugation, and fresh medium was added to prevent the buildup of waste products. Cultures were enumerated using a Novocyte 3000 flow cytometer, and the concentration was adjusted to approximately 103 cells/mL, prior to the spreading of 100 μL aliquots on YPD plates for CFU counting on days 0, 5, 7, 10, 12 and 14. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h, prior to In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) imaging, which was done to capture the fluorescence. The experiments were repeated in biological triplicate. The fluorescent CFU were enumerated from the images, and the red fluorescence was expressed as a percentage of the total CFU recovered.

Murine model of VVC.

The VVC murine model was performed as described previously, with slight modification (34–36). In short, groups of 6- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (n = 4) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and were housed in isolator cages that were mounted on ventilated racks. Mice were subcutaneously administered 0.1 mg β-estradiol 17 valerate (estrogen, E2) that was dissolved in sesame oil 3 days prior to vaginal lavage or challenge with C. albicans. Thereafter, E2 was administered weekly. For the mono-infections, stationary-phase cultures of C. albicans strains were washed, counted, and then adjusted to 5 × 108 cells/mL in sterile endotoxin-free PBS. For the competitive survival experiments, stationary-phase cultures of GFPy-tagged and dTomato-tagged C. albicans strains were washed, counted, and then mixed 1:1 at a total density of 5 × 108 cells/mL. The mice were intravaginally inoculated with 10 μL of cell suspension, which generated an inoculum size of 5 × 106 blastoconidia. The mice underwent vaginal lavage every 4 days with 100 μL of PBS until day 16 postinoculation.

Assessment of vaginal fungal burden and immunopathology.

For the mono-infections, the recovered vaginal lavage fluids (VLF) were spiked with 100× EDTA-free protease inhibitors (cOmplete; Roche). Fresh VLF (10 μL) was smeared onto Tissue Path Superfrost Plus Gold slides (Fisher Scientific), allowed to air dry, fixed with CytoPrep spray fixative (Fisher Scientific), and stored at room temperature. The VLFs were then centrifuged, and the supernatants were transferred to new tubes and stored at −80°C. Tubes containing pellets were weighed before and after the removal of the supernatant so as to calculate the amount of PBS with which to resuspend the pellet for microbiological plating. For the assessment of the fungal burden, 50 μL aliquots were serially diluted, plated on YPD agar plates containing 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and subsequently incubated at 30°C for 48 h. The resulting colonies were enumerated and reported as the median. Slides containing fixed lavage fluids were stained using the Papanicolaou technique so at to enumerate the polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), as identified by their morphologies, staining appearances, and characteristic trilobed nuclei (35, 65). For each smear, the PMNs were manually counted in five nonadjacent fields via standard light microscopy, using a 40× objective. The PMN counts were averaged per field, and the values are reported as the mean PMN count per group ± the standard deviation (SD). The slides were also scanned using a Hamamatus NanoZoomer-SQ Digital slide scanner (20×) to detect hyphal growth. The fungal burdens were similarly assessed for the in vivo competitive survival assay, except that the fluorescence images were captured via IVIS and that the colonies were enumerated. The data are presented either as a percentage of the green or red fluorescent colonies over the total (mean ± SEM) or as raw CFU counts (median).

IVIS imaging.

Images were captured using an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) Spectrum, following the instructions from the manufacturer. Wavelengths of λex = 480nm/λem = 510nm and λex = 535nm/λem = 580nm were selected for GFPy and dTomato, respectively. The experimental setup was validated via the blinded mixing of various ratios of GFPy and dTomato cultures, prior to plating and to the back-calculation of the relative percentages. The images that were retrieved from the green and red channels were saved and merged for CFU counting, using the ImageJ software package.

Mouse model of disseminated candidiasis.

C. albicans overnight cultures were washed twice in sterile, endotoxin-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were resuspended in PBS. The cell density was determined via hemocytometer and was diluted to 7.5 × 106 cells/mL. Groups of 6- to 8-week-old female CD-1 mice (n = 6) were inoculated with 0.1 mL of cell suspension via lateral tail vein injections. The mice were monitored three times daily for 14 days postinfection, with their weights being measured every other day. Those showing distress were euthanized. The inoculum densities were confirmed by plating dilutions of the cell suspension onto YPD agar plates and counting the colonies after 72 h.

Figure and graphic construction.

The images were constructed in NDP.view2 (2.9.29), GraphPad Prism (9.3.1), Microsoft PowerPoint (16.67), or BioRender (biorender.com, agreement number AM24EAILXC). Any adjustments to the brightness or the contrast were applied evenly across the images. High-resolution, publication-compliant images were generated using Adobe Photoshop (23.5.0).

Statistical analysis.

All of the data were plotted and analyzed for statistical significance using GraphPad Prism. The data were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple unpaired t test, and either Dunnett’s or Tukey’s post-tests, depending on whether the data were normally distributed. The graphs are annotated to indicate the levels of the statistical significance of the results (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Data availability.

The original contributions that are presented in the study are included in the article text, figures, and Supplemental Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jack Sobel for graciously providing the deidentified C. albicans clinical isolates.

We declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

B.M.P. and J.M. contributed to the study conception, design, data analysis, and manuscript draft. J.M., J.R., and C.C. conducted the experiments. J.M., J.R., C.C., G.E.P., D.L.W., M.D.K., and B.M.P. contributed to the interpretation of the processed data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01AI134796 and R21AI141829 awarded to B.M.P., R01AI152067 to G.E.P., and R21AI159877 to M.D.K. This work was also supported, in part, by the NIH grants R01GM119197 and R01GM083016 to D.L.W. and C0RR036551 to E.T.S.U. J.M. received financial support from the China Scholarship Council award 201906150153. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, data interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Brian M. Peters, Email: brian.peters@uthsc.edu.

Floyd L. Wormley, Jr., Texas Christian University

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowman DW, Sameer Al-Abdul-Wahid M, Ma Z, Kruppa MD, Rustchenko E, Williams DL. 2021. Glucan and glycogen exist as a covalently linked macromolecular complex in the cell wall of Candida albicans and other Candida species. Cell Surf 7:100061. doi: 10.1016/j.tcsw.2021.100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown AJ, Brown GD, Netea MG, Gow NA. 2014. Metabolism impacts upon Candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends Microbiol 22:614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kollar R, Reinhold BB, Petrakova E, Yeh HJ, Ashwell G, Drgonova J, Kapteyn JC, Klis FM, Cabib E. 1997. Architecture of the yeast cell wall. Beta(1–>6)-glucan interconnects mannoprotein, beta(1–>)3-glucan, and chitin. J Biol Chem 272:17762–17775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd MG. 1987. Cell envelope of Candida albicans. Crit Rev Microbiol 15:7–25. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson WA, Roach PJ, Montero M, Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Eydallin G, Viale AM, Pozueta-Romero J. 2010. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in yeast and bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:952–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ries LNA, Beattie S, Cramer RA, Goldman GH. 2018. Overview of carbon and nitrogen catabolite metabolism in the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Mol Microbiol 107:277–297. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farkas I, Hardy TA, Goebl MG, Roach PJ. 1991. Two glycogen synthase isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are coded by distinct genes that are differentially controlled. J Biol Chem 266:15602–15607. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng C, Mu J, Farkas I, Huang D, Goebl MG, Roach PJ. 1995. Requirement of the self-glucosylating initiator proteins Glg1p and Glg2p for glycogen accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 15:6632–6640. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.12.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunja ZH, Manners DJ, Khin M. 1960. Studies on carbohydrate-metabolizing enzymes. 3. Yeast branching enzyme. Biochem J 75:441–450. doi: 10.1042/bj0750441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowen DW, Meinke M, LaPorte DC. 1992. GLC3 and GHA1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are allelic and encode the glycogen branching enzyme. Mol Cell Biol 12:22–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.22-29.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang PK, Tugendreich S, Fletterick RJ. 1989. Molecular analysis of GPH1, the gene encoding glycogen phosphorylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 9:1659–1666. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1659-1666.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Wilson WA, Fujino MA, Roach PJ. 2001. Antagonistic controls of autophagy and glycogen accumulation by Snf1p, the yeast homolog of AMP-activated protein kinase, and the cyclin-dependent kinase Pho85p. Mol Cell Biol 21:5742–5752. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5742-5752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teste MA, Enjalbert B, Parrou JL, Francois JM. 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae YPR184w gene encodes the glycogen debranching enzyme. FEMS Microbiol Lett 193:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francois J, Parrou JL. 2001. Reserve carbohydrates metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 25:125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy TA, Huang D, Roach PJ. 1994. Interactions between cAMP-dependent and SNF1 protein kinases in the control of glycogen accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 269:27907–27913. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)46873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Wilson WA, Fujino MA, Roach PJ. 2001. The yeast cyclins Pc16p and Pc17p are involved in the control of glycogen storage by the cyclin-dependent protein kinase Pho85p. FEBS Lett 506:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson WA, Wang Z, Roach PJ. 2002. Analysis of respiratory mutants reveals new aspects of the control of glycogen accumulation by the cyclin-dependent protein kinase Pho85p. FEBS Lett 515:104–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson WA, Wang Z, Roach PJ. 2005. Regulation of yeast glycogen phosphorylase by the cyclin-dependent protein kinase Pho85p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 329:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achkar JM, Fries BC. 2010. Candida infections of the genitourinary tract. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:253–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobel JD. 1997. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med 337:1896–1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willems HME, Ahmed SS, Liu J, Xu Z, Peters BM. 2020. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: a current understanding and burning questions. J Fungi (Basel) 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benedict K, Jackson BR, Chiller T, Beer KD. 2019. Estimation of direct healthcare costs of fungal diseases in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 68:1791–1797. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goncalves B, Ferreira C, Alves CT, Henriques M, Azeredo J, Silva S. 2016. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit Rev Microbiol 42:905–927. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1091805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong E, Dixit S, Fidel PL, Bradford J, Fischer G. 2014. Vulvovaginal candidiasis as a chronic disease: diagnostic criteria and definition. J Low Genit Tract Dis 18:31–38. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287aced. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyirjesy P, Zhao Y, Ways K, Usiskin K. 2012. Evaluation of vulvovaginal symptoms and Candida colonization in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with canagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor. Curr Med Res Opin 28:1173–1178. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.697053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, Foxman B, Ledger WJ, Nyirjesy PR, Reed BD, Summers PR. 1998. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 178:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirmonsef P, Hotton AL, Gilbert D, Burgad D, Landay A, Weber KM, Cohen M, Ravel J, Spear GT. 2014. Free glycogen in vaginal fluids is associated with Lactobacillus colonization and low vaginal pH. PLoS One 9:e102467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirmonsef P, Hotton AL, Gilbert D, Gioia CJ, Maric D, Hope TJ, Landay AL, Spear GT. 2016. Glycogen levels in undiluted genital fluid and their relationship to vaginal pH, estrogen, and progesterone. PLoS One 11:e0153553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennerstein GJ, Ellis DH. 2001. Oestrogen, glycogen and vaginal candidiasis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 41:326–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miramon P, Lorenz MC. 2017. A feast for Candida: metabolic plasticity confers an edge for virulence. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006144. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brust H, Orzechowski S, Fettke J. 2020. Starch and glycogen analyses: methods and techniques. Biomolecules 10:1020. doi: 10.3390/biom10071020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeitz MA, Tanveer Z, Openshaw AT, Schmidt M. 2019. Genetic regulators and physiological significance of glycogen storage in Candida albicans. J Fungi (Basel) 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farkas I, Hardy TA, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. 1990. Isolation of the GSY1 gene encoding yeast glycogen synthase and evidence for the existence of a second gene. J Biol Chem 265:20879–20886. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)45298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruno VM, Shetty AC, Yano J, Fidel PL, Jr, Noverr MC, Peters BM. 2015. Transcriptomic analysis of vulvovaginal candidiasis identifies a role for the NLRP3 inflammasome. mBio 6. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00182-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters BM, Palmer GE, Nash AK, Lilly EA, Fidel PL, Jr, Noverr MC. 2014. Fungal morphogenetic pathways are required for the hallmark inflammatory response during Candida albicans vaginitis. Infect Immun 82:532–543. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01417-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano J, Fidel PL., Jr. 2011. Protocols for vaginal inoculation and sample collection in the experimental mouse model of Candida vaginitis. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyer S, Le D, Park BR, Kim M. 2018. Distinct mechanisms coordinate transcription and translation under carbon and nitrogen starvation in Escherichia coli. Nat Microbiol 3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Askew C, Sellam A, Epp E, Hogues H, Mullick A, Nantel A, Whiteway M. 2009. Transcriptional regulation of carbohydrate metabolism in the human pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000612. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eschrich D, Kotter P, Entian KD. 2002. Gluconeogenesis in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res 2:315–325. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(02)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson C, Tatchell K. 2001. Hyperactive glycogen synthase mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae suppress the glc7-1 protein phosphatase mutant. J Bacteriol 183:821–829. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.821-829.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busuioc M, Mackiewicz K, Buttaro BA, Piggot PJ. 2009. Role of intracellular polysaccharide in persistence of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 191:7315–7322. doi: 10.1128/JB.00425-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goh YJ, Klaenhammer TR. 2013. A functional glycogen biosynthesis pathway in Lactobacillus acidophilus: expression and analysis of the glg operon. Mol Microbiol 89:1187–1200. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goh YJ, Klaenhammer TR. 2014. Insights into glycogen metabolism in Lactobacillus acidophilus: impact on carbohydrate metabolism, stress tolerance and gut retention. Microb Cell Fact 13:94. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0094-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambou T, Dinadayala P, Stadthagen G, Barilone N, Bordat Y, Constant P, Levillain F, Neyrolles O, Gicquel B, Lemassu A, Daffe M, Jackson M. 2008. Capsular glucan and intracellular glycogen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biosynthesis and impact on the persistence in mice. Mol Microbiol 70:762–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang M, Liu Q, Kang X, Zhu Z, Yang H, Xi X, Zhang X, Du Y, Guo M, Tang D, Wang L. 2020. Glycogen metabolism impairment via single gene mutation in the glgBXCAP operon alters the survival rate of Escherichia coli under various environmental stresses. Front Microbiol 11:588099. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.588099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massese M, Tagliaferri F, Dionisi-Vici C, Maiorana A. 2022. Glycogen storage diseases with liver involvement: a literature review of GSD type 0, IV, VI, IX and XI. Orphanet J Rare Dis 17:241. doi: 10.1186/s13023-022-02387-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang B, Frasinyuk MS, Chikwana VM, Mahalingan KK, Morgan CA, Segvich DM, Bondarenko SP, Mrug GP, Wyrebek P, Watt DS, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ, Hurley TD. 2020. Discovery and development of small-molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase. J Med Chem 63:3538–3551. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arhar S, Gogg-Fassolter G, Ogrizovic M, Pacnik K, Schwaiger K, Zganjar M, Petrovic U, Natter K. 2021. Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the accumulation of high amounts of triacylglycerol. Microb Cell Fact 20:147. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hertzberger R, May A, Kramer G, van Vondelen I, Molenaar D, Kort R. 2022. Genetic elements orchestrating Lactobacillus crispatus glycogen metabolism in the vagina. Int J Mol Sci 23. doi: 10.3390/ijms23105590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woolston BM, Jenkins DJ, Hood-Pishchany MI, Nahoum SR, Balskus EP. 2021. Characterization of vaginal microbial enzymes identifies amylopullulanases that support growth of Lactobacillus crispatus on glycogen. bioRxiv.

- 51.Liu QH, Tang JW, Wen PB, Wang MM, Zhang X, Wang L. 2021. From prokaryotes to eukaryotes: insights into the molecular structure of glycogen particles. Front Mol Biosci 8:673315. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.673315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryu JH, Drain J, Kim JH, McGee S, Gray-Weale A, Waddington L, Parker GJ, Hargreaves M, Yoo SH, Stapleton D. 2009. Comparative structural analyses of purified glycogen particles from rat liver, human skeletal muscle and commercial preparations. Int J Biol Macromol 45:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeqiraj E, Tang X, Hunter RW, Garcia-Rocha M, Judd A, Deak M, von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff A, Kurinov I, Guinovart JJ, Tyers M, Sakamoto K, Sicheri F. 2014. Structural basis for the recruitment of glycogen synthase by glycogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E2831–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402926111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kajiura H, Takata H, Kuriki T, Kitamura S. 2010. Structure and solution properties of enzymatically synthesized glycogen. Carbohydr Res 345:817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kajiura H, Kakutani R, Akiyama T, Takata H, Kuriki T. 2008. A novel enzymatic process for glycogen production. Biocatalysis and Biotransformation 26:133–140. doi: 10.1080/10242420701789411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pugh TA, Shah JC, Magee PT, Clancy MJ. 1989. Characterization and localization of the sporulation glucoamylase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 994:200–209. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(89)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamashita I, Fukui S. 1985. Transcriptional control of the sporulation-specific glucoamylase gene in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 5:3069–3073. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3069-3073.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown GD, Gordon S. 2001. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature 413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dennehy KM, Brown GD. 2007. The role of the beta-glucan receptor Dectin-1 in control of fungal infection. J Leukoc Biol 82:253–258. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruiz-Herrera J, Elorza MV, Valentin E, Sentandreu R. 2006. Molecular organization of the cell wall of Candida albicans and its relation to pathogenicity. FEMS Yeast Res 6:14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2005.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramon AM, Fonzi WA. 2009. Genetic transformation of Candida albicans. Methods Mol Biol 499:169–174. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-151-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gerami-Nejad M, Zacchi LF, McClellan M, Matter K, Berman J. 2013. Shuttle vectors for facile gap repair cloning and integration into a neutral locus in Candida albicans. Microbiology (Reading) 159:565–579. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J, Vogel AK, Miao J, Carnahan JA, Lowes DJ, Rybak JM, Peters BM. 2022. Rapid hypothesis testing in Candida albicans clinical isolates using a cloning-free, modular, and recyclable system for CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutant and revertant construction. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0263021. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02630-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quain DE, Tubb S. 1983. A rapid and simple method for the determination of glycogen in yeast. J the Institute of Brewing 89:38–40. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.1983.tb04141.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu J, Willems HME, Sansevere EA, Allert S, Barker KS, Lowes DJ, Dixson AC, Xu Z, Miao J, DeJarnette C, Tournu H, Palmer GE, Richardson JP, Barrera FN, Hube B, Naglik JR, Peters BM. 2021. A variant ECE1 allele contributes to reduced pathogenicity of Candida albicans during vulvovaginal candidiasis. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009884. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Glycogen metabolism mutant and revertant strains do not display general growth or filamentation defects under standard laboratory conditions. (A) WT, glycogen synthesis mutants (glg2Δ/Δ, glg21Δ/Δ, gsy1Δ/Δ, glc3Δ/Δ) and their revertants (glg2Δ/Δ+GLG2, glg21Δ/Δ+GLG21, gsy1Δ/Δ+GSY1, glc3Δ/Δ+GLC3), or glycogen catabolism mutants (gdb1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ, sga1Δ/Δ, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ) and their revertants (gdb1Δ/Δ+GDB1, gph1Δ/Δ+GPH1, sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+GPH1, gph1Δ/Δ sga1Δ/Δ+SGA1) were inoculated in YNB medium containing 0.5% glucose, and their growth was monitored for 48 h at 30°C with shaking by measuring the OD600 value. (B) These same strains were inoculated in MOPS-buffered RPMI-1640 (pH 7.0) and grown for 4 h at 37°C with shaking. Filamentation was digitally captured via light microscopy (scale bar = 50 μm). Download FIG S1, TIF file, 2.5 MB (2.5MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Miao et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.