Key Points

Question

Is intravenous sodium thiosulphate (STS) treatment associated with improvement in skin lesions and survival in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experiencing calciphylaxis?

Findings

This meta-analysis of 19 cohort studies examining STS treatment for patients with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis did not show an association between intravenous STS and skin lesion improvement or survival benefits compared with non-STS group.

Meaning

These results suggest that studies of intravenous STS on patients with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis have not found an improvement in skin lesion outcomes or survival. Future studies that rigorously evaluate therapies applied to patients with calciphylaxis are urgently needed.

This meta-analysis of cohort studies reviews current results for the association of sodium thiosulphate treatment with skin lesions and overall survival of patients with chronic kidney disease who contract calciphylaxis.

Abstract

Importance

Calciphylaxis is a rare disease with high mortality mainly involving patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Sodium thiosulphate (STS) has been used as an off-label therapeutic in calciphylaxis, but there is a lack of clinical trials and studies that demonstrate its effect compared with those without STS treatment.

Objective

To perform a meta-analysis of the cohort studies that provided data comparing outcomes among patients with calciphylaxis treated with and without intravenous STS.

Data Sources

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched using relevant terms and synonyms including sodium thiosulphate and calci* without language restriction.

Study Selection

The initial search was for cohort studies published before August 31, 2021, that included adult patients diagnosed with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis and could provide a comparison between patients treated with and without intravenous STS. Studies were excluded if they reported outcomes only from nonintravenous administration of STS or if the outcomes for CKD patients were not provided.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Random-effects models were performed. The Egger test was used to measure publication bias. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 test.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Skin lesion improvement and survival, synthesized as ratio data by a random-effects empirical Bayes model.

Results

Among the 5601 publications retrieved from the targeted databases, 19 retrospective cohort studies including 422 patients (mean age, 57 years; 37.3% male) met the eligibility criteria. No difference was observed in skin lesion improvement (12 studies with 110 patients; risk ratio, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.85-1.78) between the STS and the comparator groups. No difference was noted for the risk of death (15 studies with 158 patients; risk ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.10) and overall survival using time-to-event data (3 studies with 269 participants; hazard ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.57-1.18). In meta-regression, lesion improvement associated with STS negatively correlated with publication year, implying that recent studies are more likely to report a null association compared with past studies (coefficient = −0.14; P = .008).

Conclusions and Relevance

Intravenous STS was not associated with skin lesion improvement or survival benefit in patients with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis. Future investigations are warranted to examine the efficacy and safety of therapies for patients with calciphylaxis.

Introduction

Calciphylaxis is a rare but serious disorder of vascular calcification typically presenting with painful skin ulcerations that predominantly affects patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).1 There is no approved therapy for calciphylaxis. A 2022 meta-analysis of 6 clinical trials2 concluded that intravenous sodium thiosulfate (STS) could attenuate the progression of macrovascular calcification (in the coronary and iliac arteries) among hemodialysis patients. However, although STS has been used as an off-label therapeutic in calciphylaxis to improve pain and accelerate wound healing since 2004,3 there has been no data available from a clinical trial to inform its efficacy and safety. Many observational studies reporting the effectiveness of STS in patients with calciphylaxis lack a comparator arm, thus limiting the interpretation of their findings. To overcome this limitation, we performed a meta-analysis limited to cohort studies that provided data comparing outcomes among patients experiencing calciphylaxis treated with (intervention) and without (comparator) intravenous STS.

Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategy

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched using relevant terms and synonyms including sodium thiosulphate and calci* without language restriction. The controlled vocabulary terms, synonyms, and the complete search strategy are listed in eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 1. We contacted the authors of eligible articles to retrieve missing data. Our search included studies published before August 31, 2021. This study was exempt from review by the Mass General Brigham institutional review board, and informed consent was not required because data were publicly available. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guidelines were followed. The protocol was registered and published on PROSPERO (CRD42021235860).

Eligibility Criteria

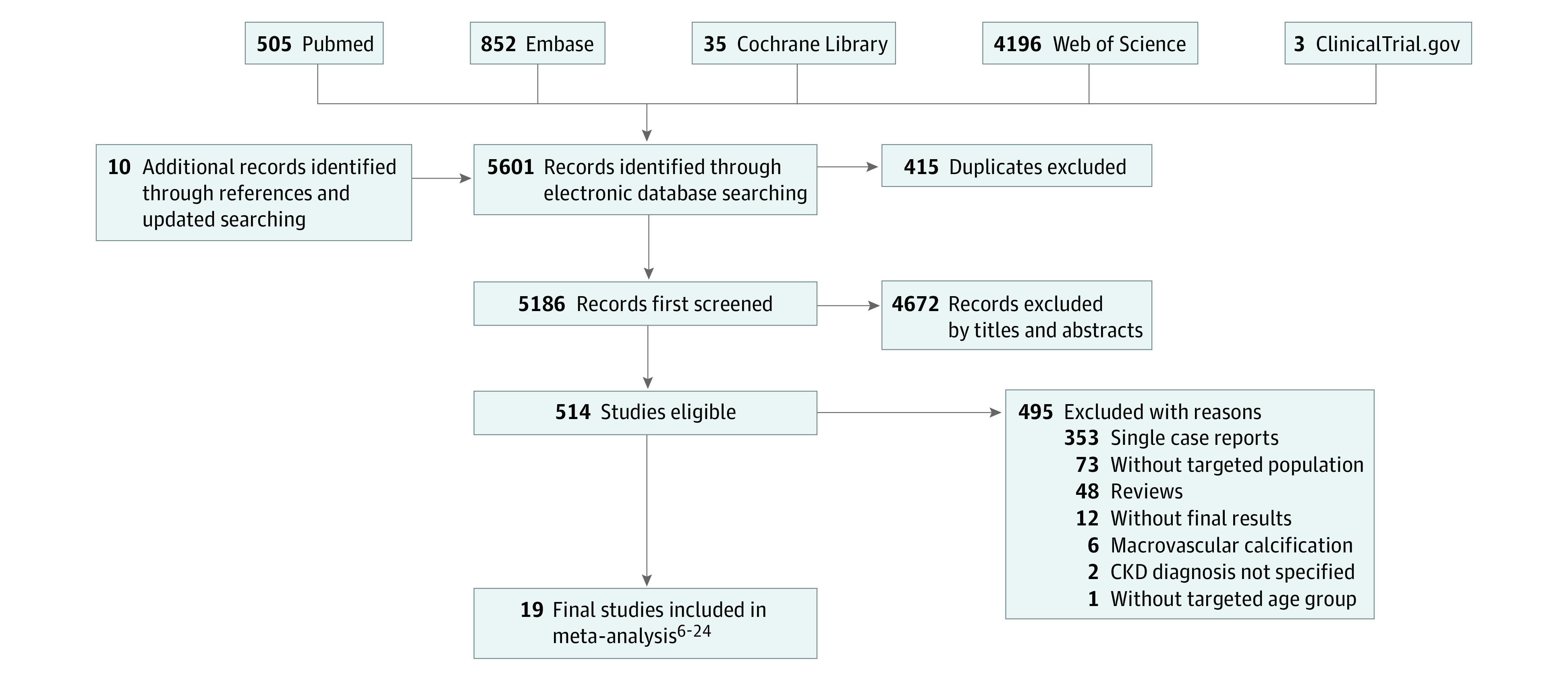

We searched for cohort studies that met the following criteria: (1) included adult patients (ages 18 years and older) diagnosed with CKD (defined as either kidney damage or a decreased glomerular filtration rate [GFR] of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for at least 3 months),4 (2) having calciphylaxis as the main complication studied and the primary indication for STS treatment, and (3) including both the patients treated with and without intravenous STS to provide a comparison between intervention and comparator groups (Figure 1). Studies were excluded if they reported outcomes only from nonintravenous administration of STS (eg, oral, intraperitoneal, intralesional, etc.), or the outcomes for CKD patients were not provided.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Study Inclusion.

Study Selection, Data Collection, and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Two authors (W.W. and I.P.) independently screened the records using Endnote X9 (Clarivate) to identify eligible studies, extracted data regarding participants, intervention, and outcome measures (lesion improvement, all-cause death, and time-to-event survival), and graded the risk of bias in the studies using Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I).5 Discrepancies among the reviewers were reevaluated by a third author (S.N.) and discussed to obtain a consensus.

Data Synthesis

Skin lesion improvement and survival were tabulated and synthesized quantitatively by performing a random-effects empirical Bayes model. Continuous correction was automatically applied when both arms had zero events. Categorical data were analyzed using log risk ratio (RR) or log hazard ratio. Meta-regression was performed to examine the impact from publication year on treatment-related effect sizes. Funnel plot and the Egger test were used to measure the publication bias. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 test. An I2 index greater than 50% indicated obvious to high heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test effect size measurements and single studies. Stata IC version 16 (StataCorp) was used for statistical analyses. The latest update of analysis was on February 6, 2023.

Results

Among the 5601 publications retrieved from the targeted databases, 19 retrospective cohort studies6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 (422 patients; mean age, 57 years; 37.3% male) met our eligibility criteria. Among the 422 patients with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis, 347 were dialysis-dependent. Detailed population distribution, demographic information, and other characteristics of these cohort studies involving patients with calciphylaxis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of 19 Retrospective Cohort Studies for Calciphylaxis.

| Source | Country | Total, No. | Kidney function cases, No. | Age, mean (SD), y | Sex, F:M | STS, No. | Longest follow-up duration | STS treatment | HBOT | Outcomes available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slough et al,6 2006 | US | 2 | HD, 1; PD, 1 | 40 (1.4) | 2:0 | 1 | 3 y | NA | None | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Malabu et al,7 2012 | Australia | 6 | HD | 66 (14.2) | 4:2 | 3 | NA | NA | 2 in STS group and 2 in comparator group | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Cohen et al,8 2013 | US | 2 | ESRD (1 on PD) | 46 (15.6) | 2:0 | 1 | 14 wk | 25g with each HD session | None | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Savoia et al,9 2013 | Italy | 4 | HD | 71 (11.7) | 2:2 | 3 | 4 y | 5 g thrice weekly at the end of the dialysis | 3, all in STS group | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Veitch et al,10 2014 | UK | 15 | CKD stage 3, 2; HD, 11; PD, 2 | 47.3 (30.2) | 11:4 | 3 | 9 y and 4 mo | NA | 2 of the 3 patients in the STS group | Mortality |

| An et al,11 2015 | Australia | 34 | Kidney transplantation, 1; CKD without dialysis, 1; HD, 25; PD, 7 | 59.7 (11.4) | 19:15 | 6 | 13 y | NA | Both groups had adequate course of HBOT | Lesion improvement |

| Lee et al,12 2015 | Singapore | 12 | Kidney transplantation, 1; HD, 7; PD, 4 | 55.8 (33.3) | 10:2 | 11 | 12 mo | 25 g thrice weekly | 3 in STS group | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| McCulloch et al,13 2015 | US | 8 | ESRD on RRT | 54.8 (7.4) | 6:2 | 7 | NA | NA | 6 in STS group and 1 in comparator group | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Loidi Pascual et al,14 2016 | Spain | 6 | CKD (1 on HD) | 79.3 (7.7) | 2:4 | 2 | 6 mo | NA | NA | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| McCarthy et al,15 2016 | US | 63 | CKD stage 5 (60 on dialysis) | NA | NA | 26 | NA | 12.5-25 g intravenously thrice weekly for 3-6 mos | 17 of the 63 cases | Mortality |

| Zhang et al,16 2016 | US | 7 | PD | 48 (13.3) | 5:2 | 4 | 1 y | 25 g thrice weekly; median duration, 3.0 mo (IQR, 2.8-5.1). | 57% of the 7 cases | Mortality |

| Ghosh et al,17 2017 | US | 4 | Kidney transplantation, 1; dialysis, 3 | 40.7 (16.3) | 3:1 | 1 | 2 y | NA | None | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Santos et al,18 2017 | US | 117 | CKD patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism | 58.5 (12.8)a | 52:42a | 64 | >12 mo | Final dose: <12.5 g, 1.7% (1); 12.5-24 g, 25.9% (15); 25-49 g, 69.0% (40); >50 g, 3.4% (2); duration: <3 mos 79.7% (47); 3-6 mso 11.9% (7); >6 mos 8.5% (5) | 9 of 117 patients | Mortality |

| Dado et al,19 2019 | US | 9 | ESRD on RRT | 50.6 (12.5) | 5:4 | 7 | 265 d | 25 g thrice weekly | NA | Mortality |

| Franco-Muñoz et al,20 2019 | Spain | 12 | CKD | NA | NA | 8 | NA | NA | NA | Mortality |

| Gaisne et al,21 2020 | France | 89 | CKD stage 4 or CKD stage 5 | 70 (11.1) | 57:32 | 58 | 5 y | median (IQR) STS cumulative dose, 488 (300-750) g; median STS duration, 6 (4-10) wk | NA | Mortality |

| Saito et al,22 2020 | Japan | 5 | HD, 4; PD, 1 | 56.2 (10.2) | 3:2 | 4 | Average follow-up, 7.4 mo | NA | 1 in STS group | Lesion improvement; mortality |

| Omer et al,23 2021 | US | 24 | ESRD on RRT | 56.3 (14.6) | 18:6 | 22 | NA | NA | 2 of all | Lesion improvement |

| Jiun et al,24 2021 | Malaysia | 3 | HD | 40.3 (14.6) | 2:1 | 2 | 6 mo | NA | None | Lesion improvement; mortality |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy; HD, hemodialysis; NA, not available; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RRT, renal replacement therapy; STS, sodium thiosulphate.

Age data available for 89 patients; sex available for 94 patients.

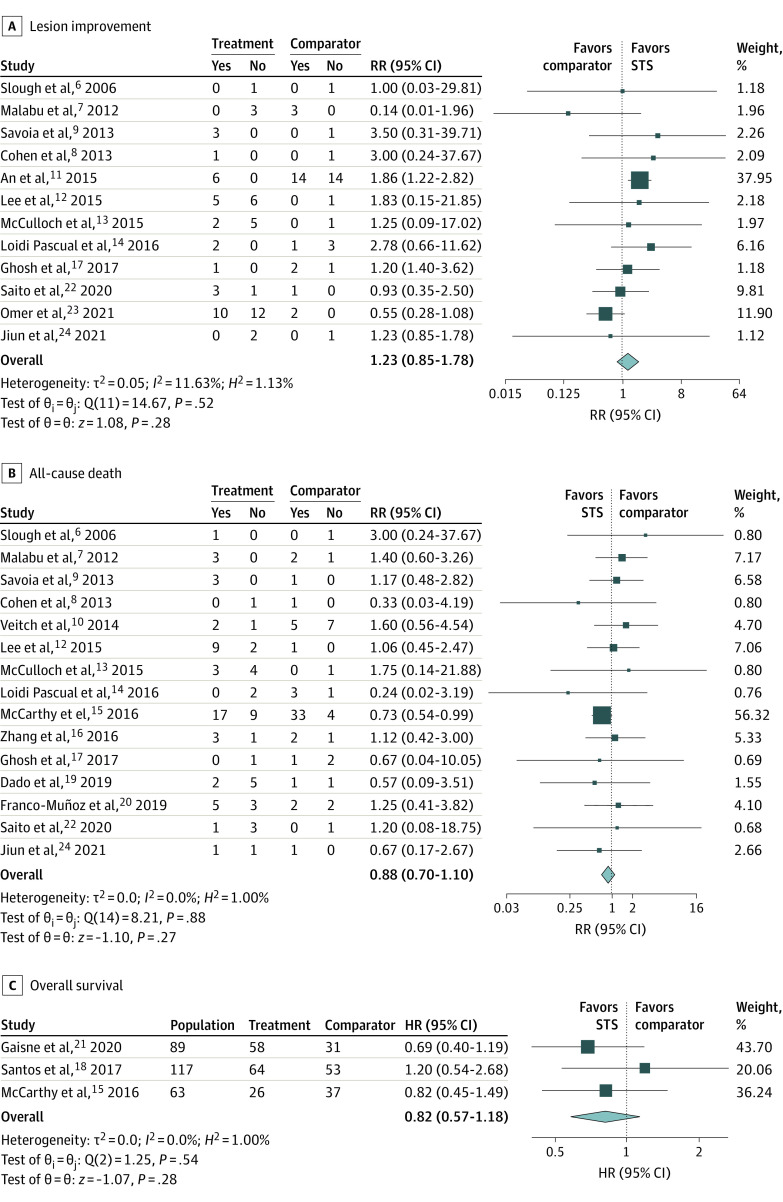

No significant difference was observed for the outcome of skin lesion improvement (12 studies, 110 patients; RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.85-1.78) between the STS and the comparator groups, although the RR favored the STS group (Figure 2A). Similarly, despite a lower risk of death noted in the STS group in studies that provided dichotomous dead or alive outcome, no significant difference was achieved (15 studies, 158 patients; RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.10) (Figure 2B). None of the 3 studies that provided time-to-event death data showed an association between STS treatment and time to death. No significant benefit was observed after synthesis using meta-analysis (3 studies, 269 participants; hazard ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.57-1.18) (Figure 2C). In meta-regression, the log RR of lesion improvement associated with STS was found to be negatively correlated with publication year (coefficient = −0.14; P = .008) (Table 2).

Figure 2. The Association of Sodium Thiosulphate (STS) With Lesion Improvement and Survival Among Patients With Calciphylaxis.

Table 2. Meta-regression for the Association of Publication Year With Outcomes of Calciphylaxis.

| Estimatesa | Coefficient (95% CI) | Standard error | z Score | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion improvement | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.04) | 0.05 | −2.65 | .008 |

| RR for mortality | −0.09 (−0.20 to −0.03) | 0.06 | −1.50 | .13 |

| HR for mortality | −0.07 (−0.26 to −0.13) | 0.10 | −0.67 | .50 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; RR, risk ratio.

Correlation analysis between publication year and log effect size estimates using z test based on random-effects model (Empirical Bayes).

We performed sensitivity analyses on effect size measurements and single studies. Compared with RR, overall odds ratios (ORs) for lesion improvement and mortality were larger with wider 95% CIs, but no differences were noticed between the 2 groups (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). In sensitivity analyses removing single studies, removing Omer et al23 resulted in a RR of 1.64 (95% CI, 1.17-2.29) in lesion improvement, which favored the use of STS, while removing An et al11 turned the RR to 0.99 (95% CI, 0.59-1.67) (eFigure 2A in Supplement 1). No change in the conclusion or direction for survival was noticed no matter which study was removed from the original analyses (eFigures 2B and 2C in Supplement 1). We synthesized small studies (total sample size fewer than 10) and large studies (total sample size of 10 or more) separately. No significant improvement in lesions or survival was observed in analyses limited to small or large studies (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). Sensitivity analysis was also performed in studies only including dialysis patients. In these studies, RR for lesion improvement was 0.68 (95% CI, 0.41-1.14) while that for all-cause death was 1.15 (95% CI, 0.73-1.80) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). Both favored the comparator group, although there was no statistically significant association.

Based on the I2 test, no obvious or high heterogeneity was noted in present analyses. Based on the ROBINS-I tool, the 19 cohort studies were evaluated to have a moderate to a critical risk of bias (eFigure 5 in Supplement 1). No small study effect was discovered (eFigure 6 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, to our knowledge the largest to date on this topic, we compared patients with CKD and calciphylaxis treated with STS and those without, and we observed no improvement in skin lesions or overall survival.

In case reports and multi-case reports, the effective rates for STS treatment were 67% and 84.4%, respectively.25 Complete and partial wound healing was observed in 80.3% of the patients receiving STS in case reports and case series, and 72.1% of those patients in cohort studies.26 However, the mortality rate remained high. In the largest cohort study of 172 patients treated with STS for calciphylaxis, the mortality rate was 35% at 1 year and 42% for the entire follow-up.27 Udomkarnjananun et al26 pooled data from 129 patients experiencing calciphylaxis in cohort studies with or without controls and found no difference in the risk of amputation, worsening of lesions, and death between patients treated with and without STS. Our study included more recently published studies and more patients than the former analysis. Sensitivity analysis and meta-regression were done to explore how various study characteristics may have factored into results. Notably, worse outcomes were observed in studies only focusing on dialysis patients. These findings raise questions regarding the role of STS in treating patients with calciphylaxis. However, treatment details about STS were not available from most of the studies and cannot be controlled by investigators. Notably, an overall survival improvement in patients with calciphylaxis has been reported with an effective therapeutic regimen of STS for not less than 2 weeks or with a cumulative dose of no less than 150 g.21 Meanwhile, negative correlation between skin lesion improvement and publication year implies a publication bias where successful treatment with STS was more likely to be published in the past, while more recently nonresponders have also been published. Thus, well-designed randomized controlled trials are warranted to establish STS’s effect on calciphylaxis.

However, recruitment of patients remains a challenge since calciphylaxis is a rare disease with life-threating nature. CALISTA trial (NCT03150420), a phase 3 trial designed to examine the effect of IV STS on acute calciphylaxis-associated pain was terminated early. An ongoing trial BEAT-CALCI (NCT05018221) is currently comparing STS, magnesium, and vitamin K treatments for patients with calciphylaxis.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Due to the lack of randomized clinical trials in this field, we gathered data only from cohort studies to do the analysis. Bias could arise from multiple sources, which was tested by the ROBINS-I tool. Of note, except for 2 studies (An et al11 and Omer et al23) that contributed the most weight to the analyses, the remaining studies were small and many had zero events of interest. Preexisting conditions could be unbalanced, as shown in Table 1. Important confounders, such as age, sex, and therapies like hyperbaric oxygen therapy were not balanced between the 2 groups. Moreover, information regarding potential additional therapies administered to patients was not consistently available, making reliable comparisons between STS and other therapies impossible. Our analysis might be underpowered and could yield residual confounding. Furthermore, lesion improvement may not be assessed uniformly throughout the studies. Another important outcome, pain intensity improvement, was not analyzed because it has not been consistently reported.

Conclusion

Intravenous STS was not associated with skin lesion improvement or survival benefits in patients with CKD experiencing calciphylaxis in this meta-analysis. A future large and well-designed randomized clinical trial is warranted to establish the effect of STS on calciphylaxis. In addition, we also call for large prospective studies to investigate the patient characteristics that may be associated with improvement upon treatment with STS. Identification of such factors will allow judicious application of STS to patients with calciphylaxis and will guide the patient selection criteria of future clinical trials.

eFigure 1. Sensitivity Analysis for Effect Measurements

eFigure 2. Sensitivity Analysis by Removing Single Studies

eFigure 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Small or Large Studies

eFigure 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Studies Only Including Dialysis Patients

eFigure 5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment of the 19 Cohort Studies Using ROBINS-I Tool

eFigure 6. Funnel Plots and Egger Test P Values for Meta-analyses in the Study

eTable 1. The Controlled Vocabulary Terms and Synonyms

eTable 2. Complete Search Strategy

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Gallo Marin B, Aghagoli G, Hu SL, Massoud CM, Robinson-Bostom L. Calciphylaxis and kidney disease: a review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81(2):232-239. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen W, Portales-Castillo I, Seethapathy R, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulphate for vascular calcification of hemodialysis patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;38(3):733-745. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(6):1104-1108. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKD-MBD Work Group . KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7(1):1-59. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slough S, Servilla KS, Harford AM, Konstantinov KN, Harris A, Tzamaloukas AH. Association between calciphylaxis and inflammation in two patients on chronic dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2006;22:171-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malabu UH, Manickam V, Kan G, Doherty SL, Sangla KS. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy on multimodal combination therapy: still unmet goal. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:390768. doi: 10.1155/2012/390768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen GF, Vyas NS. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of calciphylaxis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(5):41-44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savoia F, Gaddoni G, Patrizi A, et al. Calciphylaxis in dialysis patients, a severe disease poorly responding to therapies: report of 4 cases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148(5):531-536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veitch D, Wijesuriya N, McGregor JM, Dobbie H, Harwood C. Clinicopathological features and treatment of uremic calciphylaxis: a case series. [Letter]. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24(1):113-115. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An J, Devaney B, Ooi KY, Ford S, Frawley G, Menahem S; Conference Paper . Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series and literature review. Nephrology (Carlton). 2015;20(7):444-450. doi: 10.1111/nep.12433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KG, Lim AEL, Wong J, Choong LHL. Clinical features, therapy, and outcome of calciphylaxis in patients with end-stage renal disease on renal replacement therapy: Case series. [Letter]. Hemodial Int. 2015;19(4):611-613. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCulloch N, Wojcik SM, Heyboer M III. Patient outcomes and factors associated with healing in calciphylaxis patients undergoing adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2016;7(1-3):8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loidi Pascual L, Valcayo Peñalba A, Oscoz Jaime S, Córdoba Iturriagagoitia A, Rodil Fraile R, Yanguas Bayona JI. [Calciphylaxis: a review of 9 cases]. Article in Spanish. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;147(4):157-161. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy JT, El-Azhary RA, Patzelt MT, et al. Survival, risk factors, and effect of treatment in 101 patients with calciphylaxis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(10):1384-1394. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Corapi KM, Luongo M, Thadhani R, Nigwekar SU. Calciphylaxis in peritoneal dialysis patients: a single center cohort study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:235-241. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S115701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh T, Winchester DS, Davis MDP, El-Azhary R, Comfere NI. Early clinical presentations and progression of calciphylaxis. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(8):856-861. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos PW, He J, Tuffaha A, Wetmore JB. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with mortality in calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(12):2247-2256. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1721-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dado DN, Huang B, Foster DV, et al. Management of calciphylaxis in a burn center: a case series and review of the literature. Burns. 2019;45(1):241-246. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco-Muñoz M, González-Ruíz L, García-Arpa M, et al. Cutaneous calciphylaxis: a case series and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:AB40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaisne R, Péré M, Menoyo V, Hourmant M, Larmet-Burgeot D. Calciphylaxis epidemiology, risk factors, treatment and survival among French chronic kidney disease patients: a case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01722-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito T, Mima Y, Sugiyama M, et al. Multidisciplinary management of calciphylaxis: a series of 5 patients at a single facility. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9(2):122-128. doi: 10.1007/s13730-019-00439-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omer M, Bhat ZY, Fonte N, Imran N, Sondheimer J, Osman-Malik Y. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series and review from an inner-city tertiary university center in end-stage renal disease patients on renal replacement therapy. Int J Nephrol. 2021;2021:6661042. doi: 10.1155/2021/6661042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiun L, Chan FS, Voo SY, Wong KW. POS-801 calciphylaxis in end stage renal disease patients: a case series. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:S348. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng T, Zhuo L, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of sodium thiosulfate in treating calciphylaxis in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23(7):669-675. doi: 10.1111/nep.13081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Udomkarnjananun S, Kongnatthasate K, Praditpornsilpa K, Eiam-Ong S, Jaber BL, Susantitaphong P. Treatment of calciphylaxis in CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;4(2):231-244. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D, Wang W, Hymes J, Lacson E Jr. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1162-1170. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09880912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Sensitivity Analysis for Effect Measurements

eFigure 2. Sensitivity Analysis by Removing Single Studies

eFigure 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Small or Large Studies

eFigure 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Studies Only Including Dialysis Patients

eFigure 5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment of the 19 Cohort Studies Using ROBINS-I Tool

eFigure 6. Funnel Plots and Egger Test P Values for Meta-analyses in the Study

eTable 1. The Controlled Vocabulary Terms and Synonyms

eTable 2. Complete Search Strategy

Data Sharing Statement